Abstract

Purpose: Naegleria fowleri is the main etiologic agent implicated in primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM). It is also known as the brain-eating amoeba because of the severe brain inflammation following infection, with a survival rate of about 5%. This review aims to identify Naegleria fowleri infections and evaluate patients’ progression. This literature review emphasizes the importance of rapid diagnosis and treatment of infected patients because only prompt initiation of appropriate therapy can lead to medical success. Compared to other articles of this kind, this one analyzes a large number of reported cases and all the factors that affected patients’ evolution. Materials and methods: Two independent reviewers used “Naegleria fowleri” and “case report” as keywords in the Clarivate Analytics—Web of Science literature review, obtaining 163 results. The first evaluation step was article title analysis. The two reviewers determined if the title was relevant to the topic. The first stage removed 34 articles, leaving 129 for the second stage. Full-text articles were evaluated after reading the abstract, and 77 were eliminated. This literature review concluded with 52 articles. Key findings: This review included 52 case report articles, 17 from the USA, eight from India, seven from China, four from Pakistan, two from the UK, and one each from Thailand, Korea, Japan, Italy, Iran, Norway, Turkey, Costa Rica, Zambia, Australia, Taiwan, and Venezuela, and Mexico. This study included 98 patients, with 17 women (17.4%) and 81 men (82.6%). The cases presented in this study show that waiting to start treatment until a diagnosis is confirmed can lead to rapid worsening and bad outcomes, especially since there is currently no drug that works very well as a treatment and the death rate is around 98%. Limitations: The lack of case presentation standardization may lead to incomplete case information in the review since the cases did not follow a writing protocol. The small number of global cases may also lead to misleading generalizations, especially about these patients’ treatment. Due to the small number of cases, there is no uniform sample of patients, making it difficult to determine the exact cause of infection.

1. Introduction

Naegleria fowleri is the main etiologic agent implicated in primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) [1]. It is also known as the brain-eating amoeba because of the severe inflammation of the brain following infection, with a survival rate of about 5% [2]. It is most commonly found in water or wet soils and grows very well on cell cultures or various artificial media [1]. Temperatures above 30 °C create a favorable environment for this amoeba, with survival and infection being impossible in the winter season [3]. However, it is not only high temperatures that can be a favorable factor but also the increased amount of suspended organic matter and sediment, which lead to poor water quality and a favorable environment for the development of amoebae [4]. This is the only amoeba species exhibiting three distinct morphologic forms: the trophozoite, flagellate, and cyst [1,5]. Naegleria fowleri enters the host’s system via the nasal tract, either by inhalation of dust-containing cysts or by aspiration of water contaminated with trophozoites or cysts. Young people are most often affected, as they are most often exposed to potentially contaminated environments [6]. The clinical course is mostly dramatic, and after an incubation period of 2 to 15 days, the disease has a sudden onset with a fulminant course toward death [7]. Since the officially recorded case of onset, contrary to the evolution of medicine, the number of cases seems to be increasing, with 381 cases reported from 1962 to 2018, originating in 33 countries [3,8]. Between 1965 and 2016, the overall number of reported PAM cases grew by 1.6% every year. During this time, the number of confirmed PAM cases grew by an average of 4.5% yearly [9]. In a 2020 study, it was reported that the worldwide prevalence of Naegleria in various water sources was 26.42%. The highest case rate was found in America, approximately 33.18%, not only due to multiple sources for possible infection, but also due to the large number of studies that have taken place in this territory [10].

This review aims to identify documented cases of Naegleria fowleri infection and analyze the evolution of patients since the time of infection. Thus, through this literature review, we want to emphasize the importance of the rapid diagnosis and treatment of infected patients since only the initiation of appropriate therapy as promptly as possible can lead to medical success. Compared to other articles of this sort, this one brings together a large number of reported cases, analyzing in detail all the aspects that had an impact on the evolution of patients infected with Naegleria fowleri.

2. Materials and Methods

The literature review was performed by two independent reviewers on the Clarivate Analytics—Web of Science platform using as keywords the association between “Naegleria fowleri” and “case report” and 163 results were obtained. The first evaluation step was to analyze the title of the articles. If the title was considered significant for the chosen topic, the two reviewers proceeded to abstract analysis. After the first stage, 34 articles were eliminated, leaving 129 articles for the second stage. After reading the abstract, the next eliminatory stage was the evaluation of full-text articles, and 77 papers were excluded. Finally, 52 articles were included in this literature review.

The inclusion criteria were English language, and case report type articles describing the cases of patients infected with Naegleria fowleri, regardless of the evolution they had after confirmation of the diagnosis. All eligible articles were included regardless of the year of publication or the age of patients included in the studies.

Exclusion criteria were articles that were written in full-text in a language other than English, articles that could not be accessed, conference presentations, abstracts, letters to the editor, books, editorial material, proceeding papers or review articles, and articles in which insufficient patient data were identified.

3. Results

The general characteristics of the cases included in our study can be observed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of cases included in the review.

The evolution and treatment of the patients included in this review can be observed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Evolution and treatment of the patients included in the review.

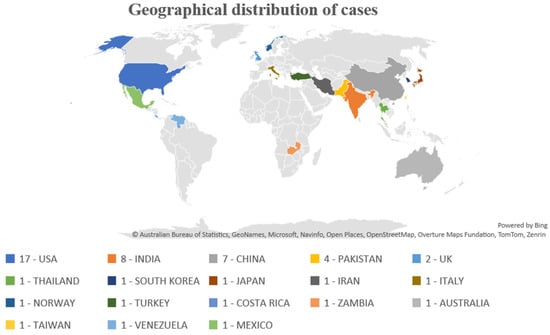

This review included 52 case report articles, 17 from the USA, eight from India, seven from China, four from Pakistan, two from the UK, and one each from Thailand, Korea, Japan, Italy, Iran, Norway, Turkey, Costa Rica, Zambia, Australia, Taiwan, Venezuela, and Mexico. A total of 99 patients were included, including 17 women (17.17%) and 82 men (82.82%). (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of cases.

The patients’ ages in the study ranged from 11 days to 75 years. There were seven patients less than 1 year old, 16 patients aged between 2 and 10 years, 19 patients aged between 10 and 20 years, 13 patients aged between 21 and 40 years, and 12 patients older than 40 years. In addition, in two of the studies mentioned in the review, there were 19 and 13 patients, respectively, with a mean age of 28 and 31 ± 15.33 years, respectively. Approximately, the age at which patients are more susceptible to Naegleria fowleri infection seems to be 10–40 years.

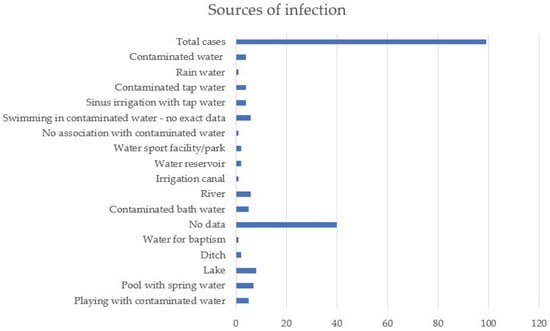

Discussing the way of infection, in 40 of the 99 cases, no exact cause or contact with contaminated water could be established, and in only one person, no link between infection and a water source was observed. Five of the patients developed symptoms after playing in areas with contaminated water, seven after swimming in pools that were irrigated with spring water, and eight and six, respectively, after swimming in lakes or rivers. One of the patients under the age of 1 died shortly after baptism, and another after being exposed to water collected after rain. For five people, symptoms started after bathing in possibly contaminated water, and six after swimming in areas where Naegleria fowleri was found after water testing. The condition of four of the patients worsened after nasal irrigation with tap water, and of another four after using tap water for various household activities. Other sources of infection were ditch water, canal irrigation, water tanks, or water parks (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sources of infection.

The most common symptoms with which patients in the articles included in the review presented to the doctor were fever, headache, and vomiting, symptoms specific for meningeal inflammation. Other less common symptoms were seizures, neck stiffness, fatigue, confusion, and sensory disturbances. In most cases, no exact diagnosis was considered until the results were received. However, patients who presented with symptoms specific to meningeal irritation were given a presumptive diagnosis of viral or bacterial meningitis.

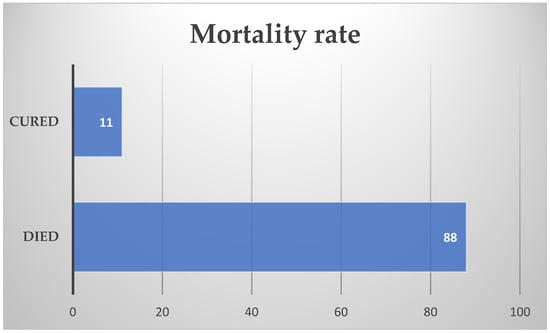

Of the 99 patients, only 11 of them survived the Naegleria fowleri infection, the mortality rate being 88.88%. (Figure 3) The hospitalization period ranged from 10 h to 4 months. Further discussion on the hospitalization period shows that the most common hospitalization period was 1–5 days (45 patients). Six patients were hospitalized for 5–10 days, 3 for 1–15 days, and 14 for more than 15 days. In one study, the hospitalization period of 13 patients was approximately 6.38 ± 3.15 days. Only one case, a 6-month-old infant, had a fulminant progression to death within 10 h.

Figure 3.

Mortality rate.

Of the patients who survived, the average age was 17.8 years and the average length of hospitalization was 29.5 days. Excluding the only elderly patient in this group (73 years), the mean age for surviving patients was 11.66 years, with a mean number of days hospitalized of 31.67. In terms of patients who did not survive, the average age was about 21 years, with a number of days of hospitalization of around 8.39 days. If we exclude the only patient who was hospitalized for 4 months, the average number of days of hospitalization becomes about 6.25 days. Thus, we could say that the patients who were cured had a much longer period of hospitalization, but also a lower average age, compared to those who did not survive the Naegleria fowleri infection.

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevention

Infection with Naegleria fowleri is often fatal, with death occurring in less than 72 h in many patients [50]. As observed in the cases included in this study, it seems that one of the most common causes of infection is contact with contaminated water. Most of the time, patients come in contact with water by swimming in lakes, rivers, or even swimming pools that are not properly sanitized [59]. With modernization, the number of cases among tourists who frequent vacation resorts that include heated swimming pools has increased. For example, a 2005 study evaluating the presence of this amoeba in tourist sites in Thailand found that Naegleria fowleri was present in about 40% of the recreational sites sampled [60]. Infection can only be prevented by avoiding these types of recreational areas because, as observed in the cases presented above, most of the hospitalized patients had a history of swimming either in unsanitized swimming ponds or in natural recreational sites such as lakes or rivers. Another method of prevention could be to avoid swallowing or mouth or nostril contact with contaminated water [43].

In the cases presented above, some of the patients came into contact with this amoeba after nasal irrigation with contaminated water; therefore, people practicing this habit should be more careful about the water they use because the olfactory mucosa is one of the entry points of the amoeba [40]. When it comes to cases of infection in newborns, parents should be cautious about the water they use for preparing milk and bathing their babies since they cannot become contaminated by swimming in potentially infectious areas, but only by contact with contaminated water through ingestion or during bathing [51]. For this reason, the diagnosis of PAM is very difficult to consider in this type of patient, thus lowering the success rate of therapy [51]. Among the six cases of children under 1 year of age included in the review, four of them mention contaminated water in which the babies were being bathed as the cause of infection.

Those most susceptible to infection with this amoeba are young people with good immunity, especially young men because they are most often involved in water recreational activities in the warm season [21,31]. As noted in our review, the average hospitalization period until patients most often progress to fatality is about 5–10 days from the onset of symptoms [31]. However the infection rate is quite low, and the incidence of the disease is very low, because rarely do people who come in contact with a potential source of infection develop the disease [47].

4.2. Diagnosis

For patients to have a favorable outcome, therapy should be started as soon as possible; for this reason, physicians should be much better informed about this infection and its signs and take it into account when patients are presented in the emergency room [22]. PAM is clinically indistinguishable from classic bacterial meningitis, which is why the amoebic etiology should be suspected whenever the presence of a pathogenic bacterium cannot be detected in the CSF. Criteria that could guide the physician toward the diagnosis of this infection could be young age, recent activity in the aquatic environment, or contact with various water sources, especially heated swimming pools, rivers, lakes, or stagnant water [3,7,31]. Even when considering possible Naegleria infection, delaying optimal medication until the diagnosis is confirmed is not an ideal option, as trophozoites in cerebrospinal fluid are detected by time-consuming methods. In most of the presented cases, patients became comatose by the time of diagnostic confirmation and under correct therapy they decompensated [47]. The methods of choice for diagnosis are evaluation of the CSF smear and brain biopsy, but in recent years, there have been studies that have shown the efficiency and rapidity of next-generation sequencing (NGS) [58]. Even so, if the Naegleria fowleri infection is not taken into account and therapy is not initiated until the results are received, the chances of survival decrease, especially as there is currently no drug with substantial therapeutic efficacy, the mortality rate being approximately 98% [55].

4.3. Treatment

Regarding treatment, active substances proven to be useful include Amphotericin B, Miconazole, Tetracycline, and Rifampicin. The drug of choice used to treat this infection is Amphotericin B, administered intravenously and intrathecally, thus ensuring an increased concentration in the cerebrospinal fluid [4]. Lately, an antiparasitic called Miltefosine has been added to the basic therapeutic regimen, together with Amphotericin B, Rifampicin, and Fluconazole, with an increased success rate [56,57]. This was validated as a therapy in 2022 after an 8-year-old child was completely cured after it was added to the therapeutic regimen. Even though Amphotericin B has proven its efficacy, the similar adverse effects with patients’ onset symptoms plus nephrotoxicity emphasize the need for a new therapy. Moreover, Miltefosine has proven to be effective when it comes to patient survival following Naegleria fowleri infection, but in most cases, patients are neurologically affected [61].

Recently, there has been increasing discussion about new nanoparticle-based therapies, which are superior to older drugs because they can cross the blood–brain barrier much more easily, without the need for an additional dose increase [61,62]. Studies show that a large amount of the drug could be administered intranasally via these nanoparticles, but the cytotoxic effects and pharmacokinetics are not fully known [63]. For example, in 2017, a study of a silver nanoparticle conjugated with Amphotericin B, Nystatin, and Fluconazole was reported, which showed in vitro efficacy against the brain-eating amoeba but showed a cytotoxic effect of up to 75% [64]. On the other hand, the 50 µM concentration of a gold nanoparticle conjugated with trans-cinnamic acid showed efficacy as high as Amphotericin B, with no signs of cell toxicity [65].

5. Conclusions

The cases presented in this review are proof that delaying therapy until the diagnosis is confirmed or even because not considering Naegleria fowleri infection can lead to a fulminant evolution with an unfortunate outcome. It is important that physicians who see patients with meningitis-specific symptoms of any cause should also consider Naegleria fowleri infection, especially in young people with a history of warm-season swimming in unhygienic, inadequately irrigated places, as prompt initiation of specific therapy may increase survival rates.

6. Limitations

Considering that the cases described did not follow a unique writing protocol, the lack of standardization of case presentation may lead to incomplete information about the cases included in the review. Moreover, the small number of cases reported at the global level may lead to misleading general conclusions, especially regarding the appropriate treatment for this type of patient. Another limitation can be considered the lack of a uniform sample of patients, due to the small number of cases; thus, conclusions about the exact cause of infection may not be clear and accurate. Moreover, the reasons why some patients are more susceptible to Naegleria fowleri infection have not yet been presented in the literature, especially since most of the patients were infected through contact with contaminated water with which many other people had previously come into contact.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.R. and R.G.C.; methodology, A.O.; software, A.M.; validation, C.R., C.M.C. and M.R.R.; formal analysis, A.O.; investigation, C.R.; resources, A.M.; data curation, M.R.R.; writing—original draft preparation, C.R. and R.G.C.; writing—review and editing, M.M.L.; visualization, C.M.C.; supervision, M.M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Matin, A. Primary amebic meningoencephalitis: A new emerging public health threat by Naegleria fowleri in Pakistan. J. Pharm. Res. Drug Des. 2017, 1, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Baqer, N.N.; Mohammed, A.S.; Al-Aboody, B.; Ismail, A.M. Genetic Detection of Amoebic Meningoencephalitis Causing by Naegleria Fowleri in Iraq: A Case Report. Iran J. Parasitol. 2023, 18, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, A.D.; Kumar, J.E.; Golba, C.E.; Luckett, K.M.; Bryant, W.K. Primary amebic meningoencephalitis: A review of Naegleria fowleri and analysis of successfully treated cases. Parasitol. Res. 2024, 123, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemble, S.K.; Lynfield, R.; DeVries, A.S.; Drehner, D.M.; Pomputius, W.F., III; Beach, M.J.; Visvesvara, G.S.; da Silva, A.J.; Hill, V.R.; Yoder, J.S.; et al. Fatal Naegleria fowleri infection acquired in Minnesota: Possible expanded range of a deadly thermophilic organism. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, 805–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeibig, E. Clinical Parasitology: A Practical Approach, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Saunders: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud, R.; Ai Lian Lim, Y.; Amir, A. Medical Parasitology: A Textbook; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Radulescu, S. Parazitologie Medicala; Editura ALL Education: București, Romania, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, K.W.; Jeong, J.H.; Byun, J.H.; Hong, S.H.; Ju, J.W.; Bae, I.G. Fatal Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis due to Naegleria fowleri: The First Imported Case in Korea. Yonsei Med. J. 2023, 64, 641–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharpure, R.; Bliton, J.; Goodman, A.; Ali, I.K.M.; Yoder, J.; Cope, J.R. Epidemiology and Clinical Characteristics of Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis Caused by Naegleria fowleri: A Global Review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e19–e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Saberi, R.; Seifi, Z.; Dodangeh, S.; Najafi, A.; Abdollah Hosseini, S.; Anvari, D.; Taghipour, A.; Norouzi, M.; Niyyati, M. A systematic literature review and meta-analysis on the global prevalence of Naegleria spp. in water sources. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020, 67, 2389–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apley, J.; Clarke, S.K.; Roome, A.P.; Sandry, S.A.; Saygi, G.; Silk, B.; Warhurst, D.C. Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis in Britain. Br. Med. J. 1970, 1, 596–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, A.R.; Wiley, P.F.; Brownell, B.; Warhurst, D.C. Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis. Arch. Dis. Child. 1981, 56, 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, A.R.; Shulman, S.T.; Lansen, T.A.; Cichon, M.J.; Willaert, E. Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis: A report of two cases and antibiotic and immunologic studies. J. Infect. Dis. 1981, 143, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, N.D.; Kaplan, A.M.; Hopkin, R.J.; Saubolle, M.A.; Rudinsky, M.F. Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis with Naegleria fowleri: Clinical review. Pediatr. Neurol. 1996, 15, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugita, Y.; Fujii, T.; Hayashi, I.; Aoki, T.; Yokoyama, T.; Morimatsu, M.; Fukuma, T.; Takamiya, Y. Primary amebic meningoencephalitis due to Naegleria fowleri: An autopsy case in Japan. Pathol. Int. 1999, 49, 468–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Prabhakar, S.; Modi, M.; Bhatia, R.; Sehgal, R. Naegleria meningitis: A rare survival. Neurol. India 2002, 50, 470–472. [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy, S.; Wilson, G.; Prashanth, H.V.; Vidyalakshmi, K.; Dhanashree, B.; Bharath, R. Primary meningoencephalitis by Naegleria fowleri: First reported case from Mangalore, South India. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 309–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Primary amebic meningoencephalitis-Georgia, 2002. Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. MMWR 2003, 52, 962–964. [Google Scholar]

- Cogo, P.E.; Scagli, M.; Gatti, S.; Rossetti, F.; Alaggio, R.; Laverda, A.M.; Zhou, L.; Xiao, L.; Visvesvara, G.S. Fatal Naegleria fowleri meningoencephalitis, Italy. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 1835–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, D.T.; Hanna, H.J.; Coons, S.W.; Bodensteiner, J.B. Naegleria fowleri hemorrhagic meningoencephalitis: Report of two fatalities in children. J. Child. Neurol. 2004, 19, 231–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebbar, S.; Bairy, I.; Bhaskaranand, N.; Upadhyaya, S.; Sarma, M.S.; Shetty, A.K. Fatal case of Naegleria fowleri meningo-encephalitis in an infant: Case report. Ann. Trop. Paediatr. 2005, 25, 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Zepeda, J.; Gómez-Alcalá, A.V.; Vásquez-Morales, J.A.; Licea-Amaya, L.; De Jonckheere, J.F.; Lares-Villa, F. Successful treatment of Naegleria fowleri meningoencephalitis by using intravenous amphotericin B, fluconazole and rifampicin. Arch. Med. Res. 2005, 36, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, F.; Vilchez, V.; Torres, G.; Molina, O.; Dorfman, S.; Mora, E.; Cardozo, J. Meningoencefalitis amebiana primaria: Comunicacion de dos nuevos casos Venezolanos. Arq. de Neuro-Psiquiatria 2006, 64, 1043–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Primary amebic meningoencephalitis-Arizona, Florida, and Texas, 2007. Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. MMWR 2008, 57, 573–577. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, N.; Bhaskar, H.; Duggal, S.; Ghalaut, P.S.; Kundra, S.; Arora, D.R. Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis: First reported case from Rohtak, North India. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 13, 236–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, T.; Rabbani, M.; Jamil, B. Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis: Two new cases from Pakistan. Trop. Doct. 2009, 39, 242–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoor, S.; Beg, M.A.; Mahmood, S.F.; Bandea, R.; Sriram, R.; Noman, F.; Ali, F.; Visvesvara, G.S.; Zafar, A. Primary amebic meningoencephalitis caused by Naegleria fowleri, Karachi, Pakistan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, V.; Khanna, R.; Hebbar, S.; Shashidhar, V.; Mundkar, S.; Munim, F.; Annamalai, K.; Nayak, D.; Mukhopadhayay, C. Primary Amoebic Meningoencephalitis in an Infant due to Naegleria fowleri. Case Rep. Neurol. Med. 2011, 2011, 782539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, P.L.; Sharma, S.; Puri, S.; Kumar, R.; Midha, V.; Bansal, R. A rare case of survival from primary amebic meningoencephalitis. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 16, 34–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoder, J.S.; Straif-Bourgeois, S.; Roy, S.L.; Moore, T.A.; Visvesvara, G.S.; Ratard, R.C.; Hill, V.R.; Wilson, J.D.; Linscott, A.J.; Crager, R.; et al. Primary amebic meningoencephalitis deaths associated with sinus irrigation using contaminated tap water. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 55, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movahedi, Z.; Shokrollahi, M.R.; Aghaali, M.; Heydari, H. Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis in an Iranian infant. Case Rep. Med. 2012, 2012, 782854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Notes from the field: Primary amebic meningoencephalitis associated with ritual nasal rinsing-St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands, 2012. Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. MMWR 2013, 62, 903. [Google Scholar]

- Su, M.Y.; Lee, M.S.; Shyu, L.Y.; Lin, W.C.; Hsiao, P.C.; Wang, C.P.; Ji, D.D.; Chen, K.M.; Lai, S.C. A fatal case of Naegleria fowleri meningoencephalitis in Taiwan. Korean J. Parasitol. 2013, 51, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, A.; Chauhan, S.; Chandel, L.; Jaryal, S.C. Prompt diagnosis and extraordinary survival from Naegleria fowleri meningitis: A rare case report. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2014, 32, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariq, A.; Afridi, F.I.; Farooqi, B.J.; Ahmed, S.; Hussain, A. Fatal primary meningoencephalitis caused by Naegleria fowleri. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2014, 24, 523–525. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, P.J.; Bodager, D.; Slade, T.A.; Jett, S. Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis Associated with Hot Spring Exposure During International Travel—Seminole County, Florida, July 2014. Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. MMWR 2015, 64, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, J.R.; Ratard, R.C.; Hill, V.R.; Sokol, T.; Causey, J.J.; Yoder, J.S.; Mirani, G.; Mull, B.; Mukerjee, K.A.; Narayanan, J.; et al. The first association of a primary amebic meningoencephalitis death with culturable Naegleria fowleri in tap water from a US treated public drinking water system. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 60, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.O.; Cope, J.R.; Moskowitz, M.; Kahler, A.; Hill, V.; Behrendt, K.; Molina, L.; Fullerton, K.E.; Beach, M.J. Notes from the Field: Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis Associated with Exposure to Swimming Pool Water Supplied by an Overland Pipe—Inyo County, California, 2015. Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. MMWR 2016, 65, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, J.R.; Conrad, D.A.; Cohen, N.; Cotilla, M.; DaSilva, A.; Jackson, J.; Visvesvara, G.S. Use of the Novel Therapeutic Agent Miltefosine for the Treatment of Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis: Report of 1 Fatal and 1 Surviving Case. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, 774–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubhaug, T.T.; Reiakvam, O.M.; Stensvold, C.R.; Hermansen, N.O.; Holberg-Petersen, M.; Antal, E.A.; Gaustad, K.; Førde, I.S.; Heger, B. Fatal primary amoebic meningoencephalitis in a Norwegian tourist returning from Thailand. JMM Case Rep. 2016, 3, e005042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stowe, R.C.; Pehlivan, D.; Friederich, K.E.; Lopez, M.A.; DiCarlo, S.M.; Boerwinkle, V.L. Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis in Children: A Report of Two Fatal Cases and Review of the Literature. Pediatr. Neurol. 2017, 70, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, J.R.; Murphy, J.; Kahler, A.; Gorbett, D.G.; Ali, I.; Taylor, B.; Corbitt, L.; Roy, S.; Lee, N.; Roellig, D.; et al. Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis Associated with Rafting on an Artificial Whitewater River: Case Report and Environmental Investigation. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 66, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heggie, T.W.; Küpper, T. Surviving Naegleria fowleri infections: A successful case report and novel therapeutic approach. Travel. Med. Infect. Dis. 2017, 16, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanchi, N.K.; Jamil, B.; Khan, E.; Ansar, Z.; Samreen, A.; Zafar, A.; Hasan, Z. Case Series of Naegleria fowleri Primary Ameobic Meningoencephalitis from Karachi, Pakistan. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 97, 1600–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomba, M.; Mucheleng’anga, L.A.; Fwoloshi, S.; Ngulube, J.; Mutengo, M.M. A case report: Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis in a young Zambian adult. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, J.; Ji, J.; Yang, L.; Chen, L.; Zhou, R.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, H.; Yuan, J.; Li, L.; et al. A case of Naegleria fowleri related primary amoebic meningoencephalitis in China diagnosed by next-generation sequencing. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Ruan, W.; Zhang, L.; Hu, B.; Yang, X. Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis: A Case Report. Korean J. Parasitol. 2019, 57, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, A.; O’Gorman, T. A local case of fulminant primary amoebic meningoencephalitis due to Naegleria fowleri. Rural Remote Health 2019, 19, 4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retana Moreira, L.; Zamora Rojas, L.; Grijalba Murillo, M.; Molina Castro, S.E.; Abrahams Sandí, E. Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis Related to Groundwater in Costa Rica: Diagnostic Confirmation of Three Cases and Environmental Investigation. Pathogens 2020, 9, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Liang, X.; Han, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, Z. A pediatric case of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis due to Naegleria fowleri diagnosed by next-generation sequencing of cerebrospinal fluid and blood samples. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, Y.; Arslankoylu, A.E. A Newborn with Brain-Eating Ameba Infection. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2021, 67, fmaa100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, S.K.; Mangrola, K.; Fitzpatrick, G.; Stockdale, K.; Matthias, L.; Ali, I.K.M.; Cope, J.R.; O’Laughlin, K.; Collins, S.; Beal, S.G.; et al. A case report of primary amebic meningoencephalitis in North Florida. ID Cases 2021, 25, e01208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Soontrapa, P.; Jitmuang, A.; Ruenchit, P.; Tiewcharoen, S.; Sarasombath, P.T.; Rattanabannakit, C. The First Molecular Genotyping of Naegleria fowleri Causing Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis in Thailand with Epidemiology and Clinical Case Reviews. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 931546, Erratum in Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1021158. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.1021158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, P.; Mowrer, C.; Jansen, L.; Karre, T.; Bedrnicek, J.; Obaro, S.K.; Iwen, P.C.; McCutchen, E.; Wetzel, C.; Frederick, J.; et al. Fatal Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis in Nebraska: Case Report and Environmental Investigation, August 2022. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2023, 109, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Che, X.; He, Z.; Tung, T.H.; Xia, H.; Lu, Z. Diagnosis of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis by metagenomic next-generation sequencing: A case report. Open Life Sci. 2023, 18, 20220579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Shen, F.; Dai, W.; Zhao, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, J. A primary amoebic meningoencephalitis case associated with swimming in seawater. Parasitol. Res. 2023, 122, 2451–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Chen, C.; Li, J.; Lian, X. Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis Caused by Naegleria fowleri in China: A Case Report. Infect. Microbes. Dis. 2024, 6, 43–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Luo, L.; Wu, M.; Chen, J.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, H. Utilizing metagenomic next-generation sequencing and phylogenetic analysis to identify a rare pediatric case of Naegleria fowleri infection presenting with fulminant myocarditis. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1463822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthanpurayil, S.N.T.; Mukundan, A.; Nair, S.R.; John, A.P.; Thampi, M.R.; John, R.; Sehgal, R. Free-living amoebic encephalitis—Case series. Trop. Parasitol. 2024, 14, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekkla, A.; Sutthikornchai, C.; Bovornkitti, S.; Sukthana, Y. Free-living ameba contamination in natural hot springs in Thailand. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2005, 36, 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Güémez, A.; García, E. Primary Amoebic Meningoencephalitis by Naegleria fowleri: Pathogenesis and Treatments. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, K.; Anwar, A.; Khan, N.A.; Aslam, Z.; Raza Shah, M.; Siddiqui, R. Oleic Acid Coated Silver Nanoparticles Showed Better in Vitro Amoebicidal Effects against Naegleria fowleri than Amphotericin B. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020, 11, 2431–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, H.; Leid, Z.H.; Debnath, A. Approaches for Targeting Naegleria fowleri Using Nanoparticles and Artificial Peptides. Pathogens 2024, 13, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, K.; Anwar, A.; Khan, N.A.; Siddiqui, R. Brain-Eating Amoebae: Silver Nanoparticle Conjugation Enhanced Efficacy of Anti-Amoebic Drugs against Naegleria fowleri. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017, 8, 2626–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajendran, K.; Anwar, A.; Khan, N.A.; Shah, M.R.; Siddiqui, R. trans-Cinnamic Acid Conjugated Gold Nanoparticles as Potent Therapeutics against Brain-Eating Amoeba Naegleria fowleri. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 2692–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).