Abstract

We present a rare case of sympathetic ophthalmia in the fellow eye of a 59-year-old Caucasian male diagnosed with untreated malignant choroidal melanoma. Initially identified with a medium-sized choroidal melanoma, the patient declined recommended brachytherapy and did not seek medical attention for two years. Upon returning, he exhibited signs of sympathetic ophthalmia in the contralateral eye. Treatment with corticosteroid-based immunosuppression was initiated. After consenting to treatment for the melanoma, the affected left eye was enucleated, and histopathology confirmed spindle cell choroidal melanoma. This case underscores the uncommon development of sympathetic ophthalmia without prior ocular trauma or surgery, linked to untreated choroidal melanoma.

1. Introduction

Sympathetic ophthalmia (SO) is a rare, diffuse granulomatous, bilateral panuveitis with an incidence of 33 per 100,000 persons with open globe injury/years [1]. The most common cause of this disease is an ocular injury, with the recent (2022) meta-analysis estimating that SO is a complication of 0.19% of ocular injuries [1]. The eye is an immune-privileged organ in which systemic immune response is reduced in physiological conditions [2]. Pathogenesis of SO is linked to the disruption of the blood–retina barrier, an event in which previously unexposed ocular antigens (such as arrestin (S-antigen), recoverin, rhodopsin, melanocyte-associated tyrosinase, interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding proteins, and retinal pigment epithelium-associated antigens) are revealed, which results in a type IV autoimmune response [2]. This phenomenon is usually an effect of ocular trauma but sometimes can be attributed to ophthalmological surgery procedures (especially pars plana vitrectomy [3]), infections and any other causes in which eye tissues are damaged [2,3]. Historically, SO has often resulted in blindness, but currently it can be successfully treated by immunosuppression, usually in the form of corticosteroid administration [3]. Melanoma is the most prevalent intraocular tumor in adults [4]. This tumor arises from melanocytes, usually from the uvea (83% of cases) and is most prevalent in Caucasian populations. The standard treatment procedures include resection, radiation (brachytherapy), and enucleation [4].

In this case report, we would like to present the history of 59-year-old, Caucasian male patient with sympathetic ophthalmia as a consequence of uveal melanoma (UM).

2. Case Report

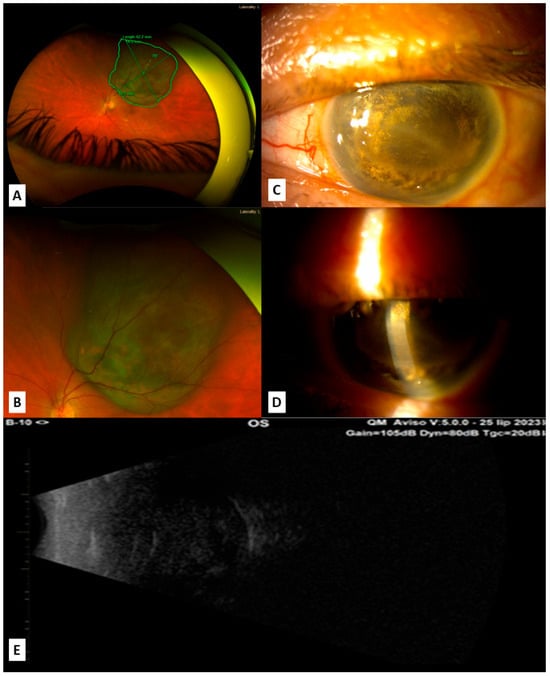

The patient was referred to the Department of General and Pediatric Ophthalmology at the Medical University of Lublin with a suspected tumor in the left eye. Ophthalmological examination of fundus revealed a choroidal melanoma of the size 14.00 mm × 12.50 mm, with a thickness of <10 mm (Table 1, Figure 1).

Table 1.

Medical history summary.

Figure 1.

Images showing the left eye of the patient; (A) measurement of the melanoma at the moment of first admission; (B) melanoma at the moment of first admission; (C,D) slit lamp examination of the left eye (OS) in the moment of SO appearance in OD, 2 years after initial tumor diagnosis: complete shallowing of the anterior chamber due to tumor masses in the posterior segment of the eye; (E) ultrasound at the moment of SO appearance shows that left eye is completely filled with tumor masses.

Visual acuity (VA) was 0.8 in the right eye (OD) and 0.6 in the left eye (OS). The patient was referred to the ophthalmological oncology center, Suggested option of treatment included brachytherapy and possible need of enucleation. However, the patient declined all proposed treatments.

After 2 years, the patient returned with no light perception in the left eye and significant visual deterioration (counting fingers at a distance of 1 m) in the right eye as well as headaches. The patient reported attending “treatment” for the left eye tumor performed by a person without medical qualifications during the two-year gap from ophthalmologic care. The patient had used unproven “alternative, natural medicine” methods instead of the recommended brachytherapy and/or enucleation—tumor was “treated” with exposure to the magnetic field.

Fundus examination of the right eye revealed a red reflex with no visible details due to vitritis. In USG examination, there was inflammatory exudate and choroidal thickening. The left eye was completely filled with a tumor and showed signs of atrophy (Figure 1).

Suspicion of sympathetic ophthalmia in the right eye was raised, and differential diagnosis included testing for antibodies against Treponema pallidum and Borrelia burgdorferi, which were negative.

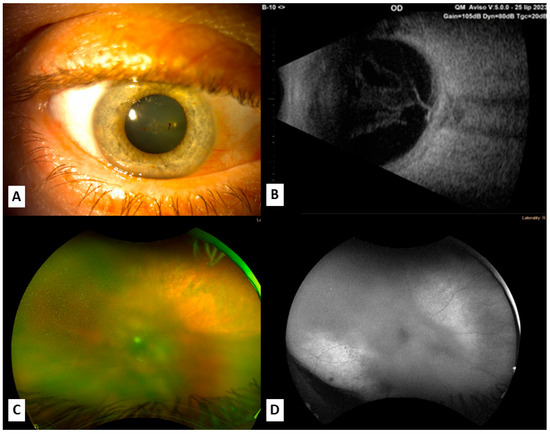

The patient was prescribed dexamethasone locally and oral prednisone of 50 mg daily. During hospitalization, an abdominal ultrasound revealed hyperechoic changes in the liver, and subsequent CT scans of the head, chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed no metastases. The liver changes were classified as hemangiomas. When transparency of vitreous increased, fundus photo and autofluorescence were performed, revealing multifocal choroidal lesions, which may most likely correspond to Dalen–Fuchs nodules, although the poor visibility of the interior of the eye prevented a definitive confirmation of the suspected nature of the findings (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Images showing the right eye; (A) slit lamp examination of the right eye at the moment of SO appearance; (B) ultrasound at the moment of SO appearance shows vitreous opacities and thicker choroid in the right eye; (C,D) fundus photo and autofluorescence of the right eye revealing destructive processes of choroid and retina.

For 3 months, sympathetic ophthalmia in the right eye was treated with systemic and topical steroids. Visual acuity in the right eye increased up to 0.3, while the left eye stayed without light perception. The patient developed early cataracts and vitreous opacities.

After 1 year of treatment, visual acuity in the right eye was 0.1 and the left eye was without light perception. During this time, the patient rejected several propositions of standard treatment for a melanoma of this size and agreed only to treatment with steroids. At this time, the patient was treated for sympathetic ophthalmia with prednisone in the dose of 10 mg. The patient was again informed of the need for enucleation of the left eye as his vision had worsened to the verge of blindness, and this time, he consented to the procedure.

The patient was admitted for the planned enucleation of the left eye by standard procedure. At this moment, his visual acuity was as follows: OD counting fingers at 1 m; OS no light perception.

The surgery proceeded as standard, without any additional complications. During the operation, no infiltration of external tissues by the tumor was observed. Following the surgery, an OCULFIT 20 mm implant was used. The patient was in good overall condition post-surgery. Histopathological examination revealed malignant spindle cell melanoma [5] with areas of necrosis and hemorrhage and a sparse inflammatory infiltrate numerous mitotic figures—up to 3 per field, and immunohistochemical readings of HMB45+, S100+, Ki 67 (+)—in about 15% of the tumor cells, and melanA (+).

After enucleation, the patient’s visual acuity in the right eye was counting fingers of the raised hand from 1 m (VA 1/60). The inflammation symptoms were greatly reduced. The patient was informed that the steroid-induced cataract in his right eye could be removed through phacoemulsification to improve his visual acuity.

3. Discussion

This rare case illustrates that sympathetic ophthalmia can be caused not only by ocular trauma but also by a neoplastic lesion located in the eye.

Historically, it has been reported that choroidal melanoma can be a cause of SO [6], although in the contemporary literature there has been only one described case (Viswanathan et al., 2018) of SO being an effect of uveal melanoma without other traumatic or surgical causes [6]. In other case reports regarding the coexistence of SO with UM, there was usually a described direct link between SO appearing and previous radiotherapy [7,8,9] or surgical removal of the UM [10]. A literature summary concerning co-existence of SO with UM is displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Literature review of sympathethic ophthalmia in choroidal melanoma case reports.

As histopathological examination revealed malignant spindle cell melanoma with areas of necrosis and hemorrhage, it is important to note that such a tumor can expose ocular antigens through mechanisms such as Bruch’s membrane rupture [12,13]. The necrosis found in the tumor can also be linked with this phenomenon, as scleral necrosis in a tumor treated with radiotherapy was found in the literature to initiate SO [9].

SO should be differentiated from other similar non-infectional and infectional causes of uveitis, as was done with our patient for Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada (VKH) syndrome (patient had no systemic symptoms), syphilis (negative serology), borreliosis (negative serology), tuberculosis (no reported contact and no changes in the thorax CT), sarcoidosis (no changes in thorax CT), multifocal choroiditis, and infectious uveitis [3,14,15].

Treatment strategies for SO include immunosuppression and surgical evisceration or enucleation of the excited eye [3]. For uveal melanoma, therapeutic options include radiotherapy and surgical excision [4]. Both options against UM were put forward, but the patient refused them and started seeking “unconventional, natural medicine”. When SO had developed, the patient agreed to immunosuppressing therapy including steroid administration p.o and locally, and finally, when the left eye was filled with the tumor mass, and the right eye was suffering from SO for more than a year, the patient agreed to enucleation.

The demonstrated case not only presents a rare ophthalmic disease but serves also as a cautionary tale. In the case of our patient, a severe complication such as sympathetic ophthalmia could have been avoided if he had undergone the standard therapy [14] proposed at the beginning of treatment. One can also conclude that SO had developed during the time in which the patient was refusing the proposed therapy (brachytherapy or surgical excision of the UM) and instead underwent the “alternative treatment” proposed by a person without professional medical education that had not resulted in any visible improvement in the patients’ condition, and had given the time for SO to develop. Alternative therapy can even be a cause of uveitis [16]—a Chinese herb, Goreisan was reported to cause tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome.

The main limitation of our study is the fact that there is no documentation of patient’s medical history during the 2 years in which the patient had refused ophthalmic care and attended only “alternative” treatment that possibly could have influenced the occurrence of SO. For this time period, we rely on the information gathered from the patient, who had admitted to attending “magnetic field exposure” therapy and denied usage of herbal medicines or unprofessional and unauthorized surgical interventions. The other factor severely influencing the outcome of therapy was patient’s refusal to many proposed forms of treatment.

Despite successful treatment and hammering autoimmune inflammatory reaction in the eye affected by SO, the final visual acuity remained low (finger counting from 1 m). This could be explained directly by the destructive processes to the retina and choroid, the formation of an epiretinal membrane, and the side effects of steroid therapy—cataractogenesis.

4. Conclusions

This case illustrates that sympathetic ophthalmia can also be an effect of untreated uveal melanoma and not only of its treatment. Early applied brachytherapy or excision of the tumor could have possibly prevented the occurrence of sympathetic ophthalmia in the second eye. The presented case report illustrated rare consequences of delay in the proper treatment of melanoma. In a span of two years, a person with good bilateral vision and a curable disease became practically blind in their only eye. Early applied treatment of uveal melanoma is crucial for the outcome and for lowering the possibility of complications. As demonstrated here, patients’ refusal to proposed treatment as well co-existing medical conditions severely limit the possibilities for treatment, lowering the chance for the preferable outcome. Treatment using only steroids and late enucleation resulted in low final visual acuity in the eye with sympathetic ophthalmia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.C. and J.D.-S.; methodology, T.C.; software, T.C. and P.O.; validation, R.R., M.D.T. and Y.A.Y.; formal analysis, T.C. and P.O.; investigation, T.C., P.O., A.S. and J.D.-S.; resources, T.C.; data curation, P.O.; writing—original draft preparation, T.C., A.S., A.C., P.O. and J.D.-S.; writing—review and editing, M.D.T., Y.A.Y., O.D. and R.R.; visualization, P.O.; supervision, R.R.; project administration, T.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to observational character of this study and obtained patients’ informed consent for publication.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- He, B.; Tanya, S.M.; Wang, C.; Kezouh, A.; Torun, N.; Ing, E. The Incidence of Sympathetic Ophthalmia After Trauma: A Meta-analysis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 234, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Hobbs, S.D. Sympathetic Ophthalmia. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Orlando, FL, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK589651/ (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Paulbuddhe, V.; Addya, S.; Gurnani, B.; Singh, D.; Tripathy, K.; Chawla, R. Sympathetic Ophthalmia: Where Do We Currently Stand on Treatment Strategies? Clin. Ophthalmol. 2021, 15, 4201–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaliki, S.; Shields, C.L. Uveal melanoma: Relatively rare but deadly cancer. Eye 2017, 31, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stålhammar, G.; Gill, V.T. Digital morphometry and cluster analysis identifies four types of melanocyte during uveal melanoma progression. Commun. Med. 2023, 3, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, D.; Haider, A.S.; Dunlop, A.; McKeag, D. Sympathetic ophthalmia associated with untreated choroidal melanoma. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 53, e173–e176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brour, J.; Desjardins, L.; Lehoang, P.; Bodaghi, B.; Lumbroso-Lerouic, L.; Dendale, R.; Cassoux, N. Sympathetic Ophthalmia after Proton Beam Irradiation for Choroïdal Melanoma. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2012, 20, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Soong, T.K.; Salvi, S.; Rudle, P.A.; Rennie, I.G. Sympathetic ophthalmia after ruthenium plaque brachytherapy. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 91, 399–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Chao, Y.-J.; Tsai, C.-C.; Chen, S.-J.; Hwang, D.-K. Sympathetic ophthalmia following radiation-induced scleral necrosis in choroidal melanoma. Taiwan J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 13, 548–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Arumi, J.; Montolio Gil, M.; Morral Palau, M.; Segura Garcia, A. Sympathetic ophthalmia after surgical resection of iridociliary melanoma. A Case report. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2006, 244, 1353–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, P.D.; Char, D.H.; Crawford, J.B.; Waterhouse, W. Sympathetic Ophthalmia Complicating Helium Ion Irradiation of a Choroidal Melanoma. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1987, 105, 1561–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkatan, H.M.; Al Qahtani, A.A.; Maktabi, A.M. Enucleated globes with choroidal melanoma: A retrospective histopathological study and correlation with cytogenetic profile in 2 eye centers. Ann. Med. Surg. 2020, 55, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarlan, B.; Kıratlı, H. Uveal Melanoma; Current Trends in The Diagnosis and Management. Türk. Oftalmol. Derg. 2016, 46, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parchand, S.; Agrawal, D.; Ayyadurai, N.; Agarwal, A.; Gangwe, A.; Behera, S.; Bhatia, P.; Mulkutkar, S.; Barwar, G.; Singh, R.; et al. Sympathetic ophthalmia: A comprehensive update. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 70, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macarie, S.S.; Huțu, D. Sympathetic Ophthalmia-case report. Rom. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 66, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, H.; Yoshioka, K.; Miyano, M.; Maeda, I.; Yamagami, K.; Morikawa, T.; Okada, N.; Konishi, Y.; Imanishi, M. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome caused by the Chinese herb “Goreisan”. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2009, 13, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).