Abstract

Background and Objectives: Malaria poses significant threats to pregnant women, particularly in endemic regions. Preventive measures against it include insecticide-treated bed nets, intermittent preventive treatment, and various supplements. We aimed to assess and compare the safety and effectiveness of malaria preventive measures in pregnant women, considering their HIV status. Methods: We conducted a systematic search of PubMed, the Cochrane Library, Scopus, Embase, and Web of Science through January 2024. A network meta-analysis was performed using R 4.3.3 software on 35 studies (50,103 participants). Results: In HIV-positive pregnant women, Co-trimoxazole with dihydroartemisinin significantly reduced malaria incidence compared to Co-trimoxazole alone (RR = 0.45, 95% CI [0.30; 0.68]) and sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine (SP) (RR = 0.14, 95% CI [0.04; 0.48]). Mefloquine was also effective compared to controls and SP. In HIV-negative women, azithromycin–piperaquine significantly reduced infections compared to SP, bed nets, and controls (RR = 0.03, 95% CI [0.00; 0.83]; RR = 0.03, 95% CI [0.00; 0.86]; and RR = 0.03, 95% CI [0.00; 0.77], respectively). Conclusion: Different combinations of preventive measures show varying effectiveness based on HIV status. Co-trimoxazole with dihydroartemisinin and mefloquine are effective for HIV-infected pregnant women, while azithromycin–piperaquine and mefloquine work well for those without HIV. Customized prevention strategies considering HIV status are crucial for optimal protection.

1. Introduction

Malaria is a significant contributor to illness and death on a global scale, particularly impacting children below the age of five and pregnant women, who are the most vulnerable populations [1]. In 2022, the global number of malaria cases was estimated to be 249 million, surpassing the pre-pandemic figure of 233 million cases recorded in 2019 by an additional 16 million. Besides the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the worldwide efforts to address malaria have encountered various emerging threats, including drug and insecticide resistance, humanitarian crises, limitations in resources, the impacts of climate change, and delays in implementing programs, especially in nations heavily burdened by the disease [1,2,3]. Malaria places a significant health and socioeconomic burden on global populations, with approximately 3.2 billion individuals facing the risk of malaria infection [4]. From 2000 to 2015, there was a 37% decline in global malaria incidence, progress attributed to economic development and urbanization in numerous endemic nations [4,5]. Additionally, there was a notable rise in investments aimed at addressing malaria, resulting in increased preventive measures, enhanced diagnostics, and improved treatment strategies [6].

Vector control is crucial in the efforts to control and eliminate malaria. The ability of vectors to transmit parasites and their susceptibility to control measures vary among mosquito species and are influenced by local environmental factors. Current prevention practices predominantly rely on personal preventive measures, which aim to minimize contact between adult mosquitoes and humans. Notably, these measures include two types of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs): long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) with insecticide embedded during manufacturing for prolonged effectiveness, and regular ITNs requiring insecticide reapplication every six months. Another approach is indoor residual spraying (IRS), involving the application of insecticides on household walls [7].

Furthermore, anti-malarial chemoprophylaxis is employed for malaria prevention in children and pregnant women. Sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine (SP), mefloquine (MQ), amodiaquine (AQ), dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine (DP), and artesunate (AS) are commonly used prophylactic drugs, offering the advantage of achieving full prophylactic effects with a single dose [8,9]. Several less commonly employed measures in malaria prevention include insecticide-treated curtains (ITCs), mosquito coils, insecticide-treated hammocks, and insecticide-treated tarpaulins. Despite a global decrease in malaria incidence, the most effective common preventive interventions for malaria infection remain unclear. Identifying the most effective interventions is essential for prioritizing resources. A single comparative study evaluating preventive efficacy across insecticide-treated nets (ITNs), indoor residual spraying (IRS), and prophylactic drugs (PDs) found that IRS is as effective as ITNs in reducing malaria-attributable mortality in children [9]. While the WHO previously endorsed sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine (SP), the diminishing effectiveness of SP in addressing symptomatic malaria over the years has raised apprehensions regarding its appropriateness for extended use in intermittent preventive treatment.

Malaria during pregnancy is a significant global health problem, particularly in areas with moderate-to-high transmission. Pregnant women are more susceptible to malaria due to reduced immunity, and HIV co-infection further increases their vulnerability. The WHO recommends a package of interventions for preventing and controlling malaria during pregnancy. For pregnant women in areas with moderate-to-high transmission of Plasmodium falciparum, the WHO recommends intermittent preventive treatment with SP, starting in the second trimester. For HIV-positive pregnant women, daily Co-trimoxazole (CTX) prophylaxis is the standard. These recommendations are crucial for tailoring malaria preventive strategies to the specific needs of pregnant women, considering their HIV status. Preventive measures include ITNs, intermittent preventive treatment, and various supplements.

We aim to evaluate and compare the safety and efficacy of various preventive strategies employed to combat malaria in pregnant women, with a specific consideration of their HIV status. This assessment encompasses an exploration of different interventions, such as insecticide-treated nets (ITNs), indoor residual spraying (IRS), and anti-malarial chemoprophylaxis, in order to discern their comparative advantages and potential drawbacks in mitigating the risk of malaria infection during pregnancy. Additionally, we seek to examine how HIV status influences the effectiveness and safety profiles of these preventive measures, aiming to provide nuanced insights into the optimal strategies for malaria prevention in pregnant women living with HIV.

2. Methods

We conducted our systematic review and network meta-analysis in adherence with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for network meta-analysis. Also, we followed the guidelines outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews throughout this study [10,11].

2.1. Searching Databases and Keywords

We searched four databases in January 2024 (PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and Scopus), and two individual authors searched. The detailed search string used for each database is provided in Supplementary Table S1. We carried out our search without imposing limitations on time or language and supplemented it by manually examining the references of the studies included in our analysis.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

We included all eligible studies that used preventive measures against malaria in pregnant women with or without HIV. We included all possible interventions, and we compared the results of each intervention regarding maternal and neonatal outcomes, in addition to safety outcomes such as abdominal pain, dizziness, headache, nausea, vomiting, neonatal deaths, preterm birth, and stillbirth. We excluded cohorts, letters, abstracts that did not provide information, case controls, and case series. Titles and abstracts were initially screened, followed by a thorough examination of the full texts of potentially relevant studies to assess eligibility and determine the final set of included studies.

2.3. Data Extraction

We extracted the following data from the included studies. (A) Baseline data: study ID, follow-up duration site, study design, maternal age, gestational age, gravid. (B) Summary data, including arm description, diagnostic tools, primary endpoint, and conclusion. (C) The outcomes that we included in our analysis were as follows: 1—incidence of malarial infection; 2—maternal anemia at delivery; 3—low birth weight (less than 2.5 kg); 4—abdominal pain incidence; 5—headache; 6—nausea; 7—vomiting; 8—neonatal deaths; 9—preterm birth; and 10—stillbirth. Two reviewers independently extracted the data to ensure accuracy and consistency. Any discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved through consultation with a third reviewer. This approach ensured that the data extraction process was thorough and reliable, contributing to the robustness of our findings.

2.4. Quality Assessment

We employed the Cochrane risk of bias tool [12] to evaluate the quality of the included RCT studies, assessing various domains such as the random sequence generation, concealed allocation, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessors, handling of incomplete data, selective reporting, and other relevant aspects. Each domain was independently evaluated by two authors, and conflicts were resolved through consultation with a third author. We also used quasi-experimental study design risk of bias assessment to assess two studies [13].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

We utilized the netmeta package in R 4.3.3 software to perform a frequentist network meta-analysis. Network plots were created to visually display the interventions and their direct and indirect comparisons, helping to understand the structure and strength of the network. The assumptions of NMA, including transitivity, consistency, and similarity, were carefully considered. Transitivity was assumed based on the similarity of patient characteristics, interventions, and outcomes across studies, allowing for valid indirect comparisons. Consistency was assessed using node-splitting methods to compare direct and indirect evidence within the network, ensuring the robustness of our findings. Similarity was ensured by including studies that were comparable in design and execution. The reference treatment was selected based on its common use and relevance in the included studies, providing a stable and consistent comparator across the network. A random-effects model was used to account for variability among studies and ensure a comprehensive analysis. Outcomes were pooled using both direct and indirect evidence to provide a comprehensive estimate of the relative effects of the interventions. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using the Chi-squared test (Q2) and I-squared test, with significant heterogeneity defined as I2 > 50% or a p-value < 0.1. A random-effects model was applied to address significant heterogeneity. P-scores were calculated to rank the interventions based on their effectiveness and safety profiles, providing a quantitative measure of the relative performance of each intervention. By incorporating these elements, we aimed to provide a robust and transparent analysis of the effectiveness and safety of malaria preventive measures in pregnant women.

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search

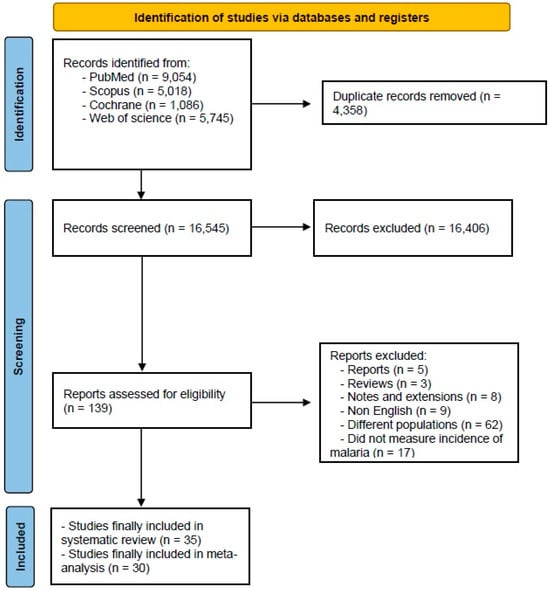

The initial database search yielded 20,903 records, reduced to 16,545 after removing 4358 duplicates. Subsequent title and abstract screening identified 139 studies for full-text assessment, ultimately including 35 studies [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48] in the systematic review; 30 of these studies of were included in the analysis (Figure 1, PRISMA).

Figure 1.

A flowchart depicting the selection process of the studies included in the meta-analysis. The diagram follows the PRISMA guidelines, illustrating the number of records identified, screened, excluded, and included in the final analysis.

3.2. Summary and Baseline Characteristics of Included Studies

Our network meta-analysis comprised nine studies that were about pregnant women with HIV, while the remaining included studies were about HIV-negative pregnant women. The studies included a total of 50,103 participants, representing a diverse population from multiple countries, with a predominant focus on the African region. The countries included were Mali, Pakistan, Australia, Kenya, Thailand, the Republic of Congo, Gambia, Benin, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Nigeria, Tanzania, Mozambique, Uganda, and Malawi. Most participants were within the maternal and gestational age range of 20 to 30 years. The follow-up duration across the studies varied from three months to two years. Various diagnostic tools were employed: quantitative PCR, nested PCR, loop-mediated isothermal amplification, thick and thin blood smears stained with Giemsa stain, microscopic examination, and targeted next-generation sequencing for molecular markers. The primary endpoint in most studies was the incidence of malarial infections. The studies included in our analysis covered a period from 1993 to 2024 (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included studies.

Table 2.

Summary of included studies.

3.3. Risk of Bias

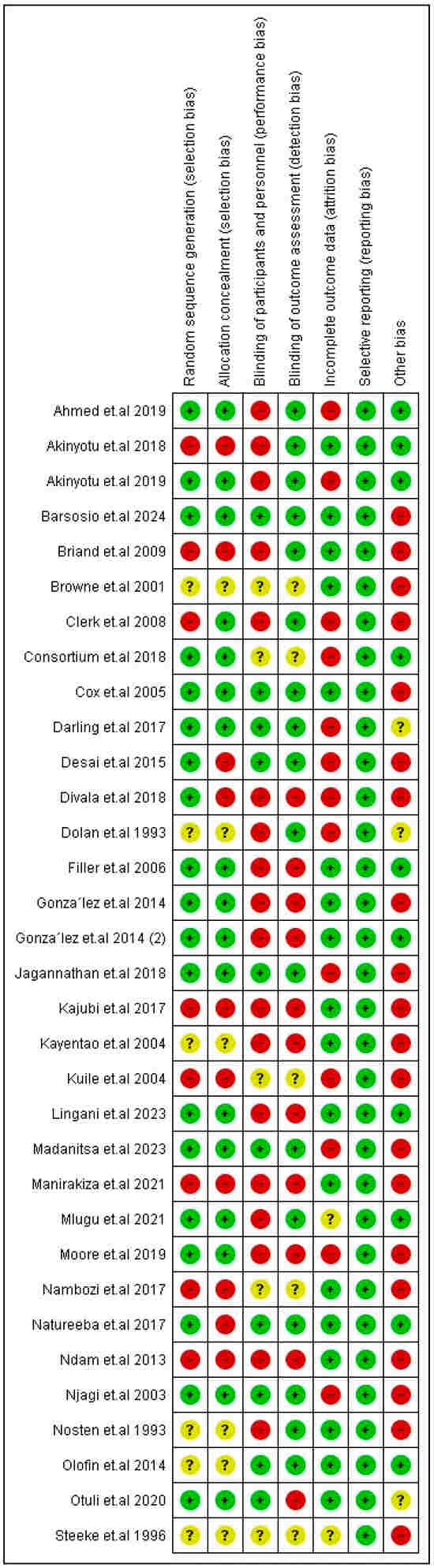

Most of the RCTs were low-risk regarding randomization and allocation processes. Moreover, all the RCTs were low-risk regarding reporting bias. However, only two of the included studies were low-risk regarding all the aspects of risk of bias except for other bias [17,42]. They were both low-risk for all aspects of risk of bias except for one aspect, while most of the other included studies were at a high risk of bias. Analysis of the two other quasi-experimental studies showed that Kumar et al., 2020 [27], was fair in quality and Roh et al., 2022 [39], was good in quality. All the details about the risk of bias and quality assessment are presented in Figure 2 and Supplementary Table S2, respectively.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias of included RCTs. Symbols: green “+” = positive association; red “−” = negative association; yellow “?” = unclear or insufficient data.

3.4. Outcomes

- (A)

- Preventive measures for pregnant women with HIV

- Incidence of malarial infection.

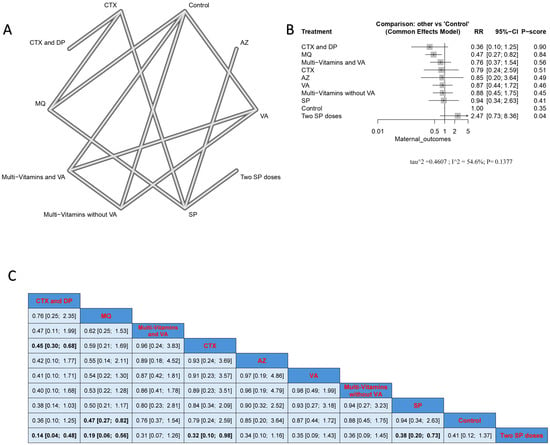

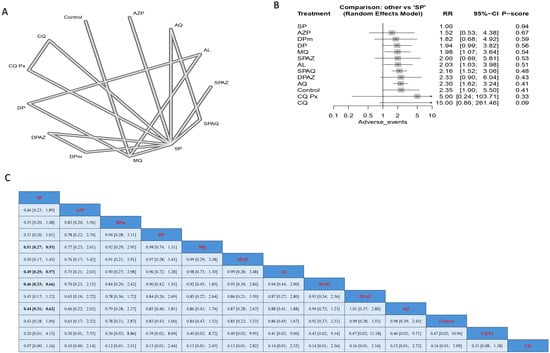

The combination of CTX with DP caused a significantly lower incidence rate when compared to CTX alone (RR = 0.45, 95% CI [0.30; 0.68]) and SP doses (RR = 0.14, 95% CI [0.04; 0.48]). The MQ intervention had a significantly lower incidence of malarial infection when compared with controls and two SP doses, and the results were (RR = 0.47, 95% CI [0.27; 0.82]), and (RR = 0.19, 95% CI [0.27; 0.82]), respectively. Also, CTX had a significantly lower incidence rate than the two SP doses. Nevertheless, the results were heterogeneous. The best three treatments, according to p-score, were the combination of CTX with DP, MQ, and the combination of multivitamins and VA (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Incidence of malarial infection in pregnant women with HIV. (A) Network graph showing direct evidence between evaluated interventions. (B) Forest plot comparing all interventions. (C) League table representing network meta-analysis estimates for all interventions’ comparisons.

- 2.

- Maternal anemia at delivery.

No significant difference was found among interventions regarding maternal anemia at delivery. According to the p-scores, the interventions that induced anemia the least were arranged as two SP doses, followed by SP, CTX, and MQ (Supplementary Figure S1).

- 3.

- Low birth weight.

We found no significant difference between the different interventions regarding low birth weight. The lowest incidence of a low birth weight of less than 2.5 kg, according to p-score, was observed with AZ, followed by MQ, followed by two SP doses (Supplementary Figure S2).

3.5. Safety Outcomes in Pregnant Women with HIV and Preventive Measures

No significant difference was detected among the different interventions regarding dizziness and headache. A significantly lower incidence of vomiting was seen in CTX treatment compared to MQ (RR = 0.07, 95% CI [0.01; 0.30]) (Supplementary Figures S3–S5, respectively).

Regarding preterm birth and stillbirth, there was no significance among the interventions. According to the p-scores, SP was associated with the lowest incidence of preterm birth, while MQ was associated with the lowest stillbirth incidence (Supplementary Figures S6 and S7, respectively).

- (B)

- Pregnant women taking preventive measures without having HIV.

- Incidence of malarial infection.

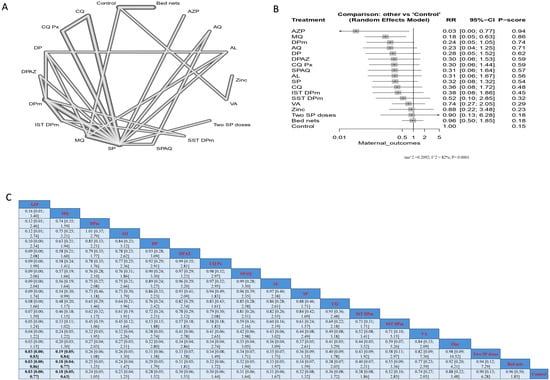

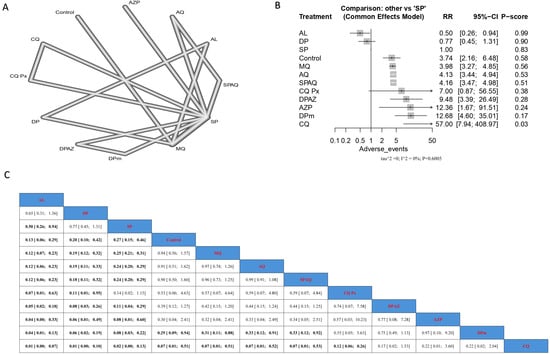

AZP significantly reduced infection when compared with two SP doses, bed nets, and controls; the results were (RR = 0.03, 95% CI [0.00; 0.83]), (RR = 0.03, 95% CI [0.00; 0.86]), and (RR = 0.03, 95% CI [0.00; 0.77]), respectively. Similarly, MQ significantly reduced infection when compared with two SP doses, bed nets, and controls; the results were (RR = 0.19, CI = 95% CI [0.05; 0.84]), (RR = 0.18, 95% CI [0.04; 0.77]), and (RR = 0.18, 95% CI [0.05; 0.63]), respectively. Nevertheless, the top treatments, according to p-score, that reduced malarial infection in patients without HIV were AZP, MQ, and DPm, followed by AQ. On the other hand, the least effective interventions were bed nets, two SP doses, and zinc (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Incidence of malarial infection in pregnant women without HIV. (A) Network graph showing direct evidence between evaluated interventions. (B) Forest plot comparing all interventions. (C) League table representing network meta-analysis estimates for all interventions’ comparisons.

- 2.

- Maternal anemia at delivery.

Comparing the different interventions regarding maternal anemia at delivery, only MQ showed a significant decrease in the incidence compared to CQ (RR = 0.54, 95% CI [0.31; 0.94]) (Supplementary Figure S8).

- 3.

- Low birth weight.

No significant difference was detected among the different interventions regarding neonatal birth weight. However, the lowest incidence of a neonatal birth weight of less than 2.5 kg, according to p-score, was found in IST DPm, followed by SST DPm and MQ (Supplementary Figure S9).

3.6. Safety Outcomes in Pregnant Women Taking Preventive Measures Without Having HIV

Regarding the incidence of abdominal pain, SP had a significantly lower incidence when compared to MQ, SPAQ, and AQ; the results were (RR = 0.51, 95% CI [0.27; 0.93]), (RR = 0.46, 95% CI [0.33; 0.66]), and (RR = 0.44, 95% CI [0.31; 0.62]), respectively (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Incidence of abdominal pain in pregnant women without HIV. (A) Network graph showing direct evidence between evaluated interventions. (B) Forest plot comparing all interventions. (C) League table representing network meta-analysis estimates for all interventions’ comparisons.

Regarding the incidence of dizziness, AL was associated with the lowest incidence of dizziness and was significant compared to all arms except for DP. It should be noted that DP and SP were associated with lower incidences of dizziness than most other interventions (Figure 6). DPm had the highest incidence of nausea compared to other arms, where its effect was significantly different from SP (RR = 0.05), AQ (RR = 0.10), and AZP (RR = 0.11). Regarding vomiting, the intervention of SP was associated with the lowest incidence of vomiting, with a significant result compared to MQ and AQ, with (RR = 0.23) and (RR = 0.28), respectively. No significant difference could be detected among the interventions regarding headache incidence rate as a side effect (Supplementary Figures S10–S12, respectively).

Figure 6.

Incidence of dizziness in pregnant women without HIV. (A) Network graph showing direct evidence between evaluated interventions. (B) Forest plot comparing all interventions. (C) League table representing network meta-analysis estimates for all interventions’ comparisons.

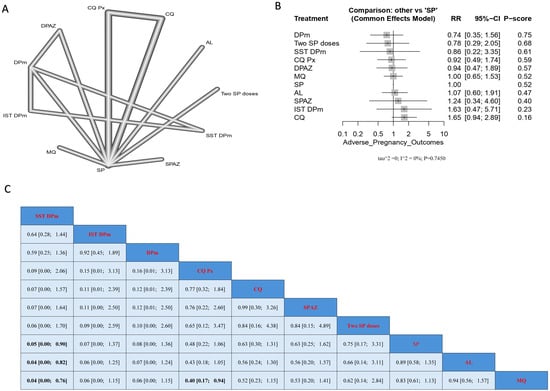

3.7. Neonatal Deaths

Treatment with CQ resulted in the highest incidence of neonatal death. SST DPm showed a significantly lower incidence of neonatal death when compared with SP, AL, and MQ, and the results were (RR = 0.05, 95% CI [0.00; 0.90]), (RR = 0.04, 95% CI [0.00; 0.82]), and (RR = 0.04, 95% CI [0.00; 0.76]), respectively. It should be noted that the lowest incidence of neonatal deaths based on the p-score was observed with DPm treatment, followed by two SP doses, and then SST DPm (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Incidence of neonatal deaths in pregnant women without HIV. (A) Network graph showing direct evidence between evaluated interventions. (B) Forest plot comparing all interventions. (C) League table representing network meta-analysis estimates for all interventions’ comparisons.

3.8. Stillbirth

The highest incidence of stillbirth was observed in the case of MQ treatment. In contrast, both SST DPm and CQ Px showed significantly lower stillbirth incidence when compared with MQ, and the results were (RR = 0.04, 95% CI [0.00; 0.76]) and (RR = 0.4, 95% CI [0.17; 0.94]), respectively. The lowest incidence of stillbirth, according to p-score, was observed with SST DPm, followed by IST DPm and then DPm (Supplementary Figure S13).

4. Discussion

Travelers visiting high-risk malaria areas, particularly pregnant women with or without HIV, should consider taking anti-malarial medication. However, chemoprophylaxis is not advisable for destinations with sporadic malaria cases and a low transmission risk. The choice of medication depends on factors such as local drug resistance, travel duration, medical history, allergies, and potential side effects. Additionally, individuals can reduce infection risk by taking preventive measures, including limiting outdoor activities, using insect repellents, and using insecticide-treated bed nets. Our study emphasizes the effectiveness of various preventive measures against malaria in both HIV-positive and -negative individuals. Combinations like Co-trimoxazole with dihydroartemisinin and mefloquine demonstrate efficacy in reducing malaria incidence compared to other interventions. Meanwhile, azithromycin with piperaquine and dihydroartemisinin is effective in HIV-negative individuals. However, safety concerns exist for interventions like mefloquine in pregnant women. Multivitamin supplementation and azithromycin also hold promise. Overall, tailored preventive strategies considering factors like HIV status and pregnancy are crucial.

Before the widespread implementation of antiretroviral therapy, Co-trimoxazole (CTX) was a cost-effective, broad-spectrum antimicrobial medication extensively utilized in developing nations. It played a crucial role in decreasing morbidity and mortality among individuals, including both adults and children, living with HIV by preventing various infections such as bacterial infections, diarrhea, malaria, and Pneumocystis pneumonia, even in the face of prevalent microbial resistance [49]. According to previous studies, CTX prophylaxis significantly reduces early mortality rates [49,50,51]. Since 2001, the World Health Organization (WHO) has endorsed artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) as the primary treatment for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria [7]. Artemisinin and its derivatives are well known for their strong anti-malarial properties and have been widely adopted for clinical use in regions where malaria is endemic. In laboratory settings, the artemisinin concentration required to inhibit 50% of Plasmodium falciparum growth ranges from 3 to 30 μg/L [51]. The combination of CTX and artemisinin-based combination therapies for prevention and treatment has shown effectiveness against malaria in HIV-positive patients. CTX reduces morbidity and mortality in individuals with HIV by preventing various infections, including malaria. Meanwhile, ACTs, endorsed by the World Health Organization since 2001, are potent in treating uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria. Combining these drugs offers a synergistic approach, enhancing malaria management strategies, especially in endemic regions [42,52].

Mefloquine is widely recognized for its high efficacy in preventing and treating malaria. It is considered one of the most effective anti-malarial drugs available, particularly in regions where malaria parasites have not developed resistance to it. When used correctly and combined with other preventive measures, mefloquine can provide robust protection against malaria infection [53,54]. The World Health Organization (WHO) permits the use of mefloquine for pregnant women during the second and third trimesters, while some authorities, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), extend this approval to the first trimester [55]. In the event of accidental pregnancy while using mefloquine, termination is not recommended. Additionally, mefloquine chemoprophylaxis is considered safe during breastfeeding. Studies indicate that mefloquine is a viable option for other high-risk groups, including long-term travelers, visiting friends and relatives (VFR) travelers, and families with young children. Despite negative media portrayal, extensive pharmaco-epidemiological investigations have demonstrated that serious adverse events associated with mefloquine are rare [56]. In our study, we found that mefloquine is not highly ranked in terms of safety outcomes in pregnant women without HIV, and it may even increase the number of stillbirth infants significantly.

The use of multivitamin supplements containing vitamin B complexes, C, and E, has been observed to decelerate disease progression and lower the occurrence of HIV-associated complications such as dysentery and acute upper respiratory infections in HIV-positive women. However, it remains unclear whether multivitamins impact malaria susceptibility in HIV-positive women. Research conducted among children indicates that multivitamin supplementation may reduce the incidence of clinical malaria [46,57].

Azithromycin has been investigated as a potential anti-malarial agent due to its slow yet potent activity against malaria parasites, targeting the apicoplast organelle [58,59]. It is considered the most potent anti-malarial macrolide, demonstrating significant activity against cultured Plasmodium falciparum after extended in vitro exposure [59]. In treating uncomplicated falciparum malaria, combinations such as artesunate plus azithromycin have shown improved efficacy compared to artesunate alone. However, they are less effective than combinations including mefloquine or dihydroartemisinin [60]. Studies assessing azithromycin in combination with chloroquine have produced mixed results, with some showing promising efficacy while others find it inferior to alternative treatments like artemether–lumefantrine [60,61].

Our study possesses several strengths, notably in comprising most of our included studies, which were randomized controlled trials and considered the gold standard in evidence quality. Our study marks the first network meta-analysis to systematically compare various outcomes between pregnant women with HIV and those without HIV. With a substantial participant pool of 50,103 individuals across 35 studies, our study provides comprehensive insights into the efficacy and safety of preventive measures against malaria in pregnancy. Our findings promise to inform future decision-making regarding selecting appropriate preventive strategies for malaria infection. However, it is essential to acknowledge certain limitations. A prevalent risk of bias compromised the overall quality of the included studies. Furthermore, factors inherent to pregnancy may confound the association between preventive measures and malaria incidence. Adverse events observed during the study period may not solely be attributable to malaria infection or preventive measures but could also be influenced by the physiological changes associated with pregnancy. Additionally, variations in malaria detection techniques may introduce heterogeneity into our analysis.

5. Conclusions

Our study highlights the efficacy of various preventive measures against malaria in both HIV-positive and -negative individuals. Combinations like Co-trimoxazole with dihydroartemisinin and mefloquine show effectiveness in reducing malaria incidence compared to other interventions, while azithromycin with piperaquine and dihydroartemisinin are effective in HIV-negative individuals compared to other interventions. However, concerns exist regarding the safety of certain interventions, such as mefloquine, in pregnant women. Multivitamin supplementation and azithromycin also show promise, but further research is needed to confirm their effectiveness. Overall, tailored preventive strategies considering factors like HIV status and pregnancy are essential, with future research focusing on optimizing interventions while ensuring patient safety.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm14103396/s1, Table S1: Detailed search strategy for retrieved databases. Table S2: Quality assessment of included quasi-experimental studies.; Figure S1: Incidence of maternal anemia at delivery in pregnant women with HIV. (A) Network graph showing direct evidence between evaluated interventions. (B) Forest plot comparing all interventions. (C) League table representing network meta-analysis estimates for all interventions’ comparisons.; Figure S2: Incidence of low birth weight in pregnant women with HIV. (A) Network graph showing direct evidence between evaluated interventions. (B) Forest plot comparing all interventions. (C) League table representing network meta-analysis estimates for all interventions’ comparisons.; Figure S3: Incidence of dizziness in pregnant women with HIV. (A) Network graph showing direct evidence between evaluated interventions. (B) Forest plot comparing all interventions. (C) League table representing network meta-analysis estimates for all interventions’ comparisons.; Figure S4: Incidence of headache in pregnant women with HIV. (A) Network graph showing direct evidence between evaluated interventions. (B) Forest plot comparing all interventions. (C) League table representing network meta-analysis estimates for all interventions’ comparisons.; Figure S5: Incidence of vomiting in pregnant women with HIV. (A) Network graph showing direct evidence between evaluated interventions. (B) Forest plot comparing all interventions. (C) League table representing network meta-analysis estimates for all interventions’ comparisons.; Figure S6: Incidence of preterm births in pregnant women with HIV. (A) Network graph showing direct evidence between evaluated interventions. (B) Forest plot comparing all interventions. (C) League table representing network meta-analysis estimates for all interventions’ comparisons.; Figure S7: Incidence of stillbirths in pregnant women with HIV. (A) Network graph showing direct evidence between evaluated interventions. (B) Forest plot comparing all interventions. (C) League table representing network meta-analysis estimates for all interventions’ comparisons.; Figure S8: Incidence of maternal anemia at delivery in pregnant women without HIV. (A) Network graph showing direct evidence between evaluated interventions. (B) Forest plot comparing all interventions. (C) League table representing network meta-analysis estimates for all interventions’ comparisons.; Figure S9: Incidence of low birth weight in pregnant women without HIV. (A) Network graph showing direct evidence between evaluated interventions. (B) Forest plot comparing all interventions. (C) League table representing network meta-analysis estimates for all interventions’ comparisons.; Figure S10: Incidence of nausea in pregnant women without HIV. (A) Network graph showing direct evidence between evaluated interventions. (B) Forest plot comparing all interventions. (C) League table representing network meta-analysis estimates for all interventions’ comparisons.; Figure S11: Incidence of vomiting in pregnant women without HIV. (A) Network graph showing direct evidence between evaluated interventions. (B) Forest plot comparing all interventions. (C) League table representing network meta-analysis estimates for all interventions’ comparisons.; Figure S12: Incidence of headache in pregnant women without HIV. (A) Network graph showing direct evidence between evaluated interventions. (B) Forest plot comparing all interventions. (C) League table representing network meta-analysis estimates for all interventions’ comparisons.; Figure S13: Incidence of stillbirths in pregnant women without HIV. (A) Network graph showing direct evidence between evaluated interventions. (B) Forest plot comparing all interventions. (C) League table representing network meta-analysis estimates for all interventions’ comparisons.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.; methodology, H.M.E., M.M.A., A.B.M. and M.A.; formal analysis, H.M.E., M.M.A. and M.A.; data curation, H.M.E., M.M.A., A.B.M. and M.A.; writing—original draft, H.M.E., M.M.A., A.B.M. and M.A.; writing—review and editing, H.M.E., M.M.A., A.B.M. and M.A.; supervision, M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This scientific paper was derived from a research grant funded by the Research, Development, and Innovation Authority (RDIA)—Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—with the grant number (12982-iau-2023-TAU-R-3-1-HW-).

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| SST | Single screening and treatment |

| IST | Intermittent screening and treatment |

| IPTp | Intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy |

| DPm | Monthly dihydroartemisinin |

| MQ | Mefloquine |

| SP | Sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine |

| AQ | Amodiaquine |

| SPAQ | Sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine plus amodiaquine |

| VA | Vitamin A |

| CQ Px | Prophylactic chloroquine |

| SPAZ | Sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine plus azithromycin |

| DPAZ | Dihydroartemisinin and azithromycin |

| AZ-PQ or AZP | Azithromycin and piperaquine |

| MQAS | Mefloquine–artesunate |

| ITN | Insecticide-treated Nets |

| AL | Artemether–lumefantrine |

| EFV | Efavirenz |

| LLINs | Long-lasting insecticide-treated bed nets |

| CTX | Co-trimoxazole |

| TMP-SMX | Trimethoprim-sulfa-methoxazole |

| AZ | Azithromycin |

References

- WHO. Malria Report 2023. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/world-malaria-report-2023-enarruzh?gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQjw-r-vBhC-ARIsAGgUO2Bxfw30urOvg7o_XLArrcglD9vsFqKveWSVAWOGspP_zKXr9KMC-LEaAtUvEALw_wcB (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines for Malaria; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, G.; Lourenço, J.; Kraemer, M.; He, Q.; Cazelles, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.; et al. The relationship between rising temperatures and malaria incidence in Hainan, China, from 1984 to 2010: A longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Planet Health 2022, 6, e350–e358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, P.; Bagada, A.; Vadia, N. Epidemiology and Current Trends in Malaria. Rising Contag. Dis. Basics Manag. Treat. 2024, 261–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, C.; Sturrock, H.J.; Hsiang, M.S.; Liu, J.; Phillips, A.A.; Hwang, J.; Gueye, C.S.; Fullman, N.; Gosling, R.D.; Feachem, R.G. The changing epidemiology of malaria elimination: New strategies for new challenges. Lancet 2013, 382, 900–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.; Rosenfeld, L.C.; Lim, S.S.; Andrews, K.G.; Foreman, K.J.; Haring, D.; Fullman, N.; Naghavi, M.; Lozano, R.; Lopez, A.D. Global malaria mortality between 1980 and 2010: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2012, 379, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO GS. World Malaria Report; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, B. Anti-malarial drugs and the prevention of malaria in the population of malaria endemic areas. Malar. J. 2010, 9 (Suppl. S3), S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, N.J. Intermittent Presumptive Treatment for Malaria. PLoS Med. 2005, 2, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.; Chandler, J.; Welch, V.; Higgins, J.P.; Thomas, J. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hutton, B.; Salanti, G.; Caldwell, D.M.; Chaimani, A.; Schmid, C.H.; Cameron, C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Straus, S.; Thorlund, K.; Jansen, J.P.; et al. The PRISMA Extension Statement for Reporting of Systematic Reviews Incorporating Network Meta-analyses of Health Care Interventions: Checklist and Explanations. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 162, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutron, I.P.M.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Lundh, A.; Hróbjartsson, A. Chapter 7: Considering bias and conflicts of interest among the included studies. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.2; Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; Cochrane: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- Waddington, H.; Aloe, A.M.; Becker, B.J.; Djimeu, E.W.; Hombrados, J.G.; Tugwell, P.; Wells, G.; Reeves, B. Quasi-experimental study designs series—Paper 6: Risk of bias assessment. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 89, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.; Poespoprodjo, J.R.; Syafruddin, D.; Khairallah, C.; Pace, C.; Lukito, T.; Maratina, S.S.; Asih, P.B.S.; Santana-Morales, M.A.; Adams, E.R.; et al. Efficacy and safety of intermittent preventive treatment and intermittent screening and treatment versus single screening and treatment with dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine for the control of malaria in pregnancy in Indonesia: A cluster-randomized, open-label, superiority trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 973–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briand, V.; Bottero, J.; Noël, H.; Masse, V.; Cordel, H.; Guerra, J.; Kossou, H.; Fayomi, B.; Ayemonna, P.; Fievet, N.; et al. Intermittent treatment for the prevention of malaria during pregnancy in Benin: A randomized, open-label equivalence trial comparing sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine with mefloquine. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 200, 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Clerk, C.A.; Bruce, J.; Affipunguh, P.K.; Mensah, N.; Hodgson, A.; Greenwood, B.; Chandramohan, D. A randomized, controlled trial of intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, amodiaquine, or the combination in pregnant women in Ghana. J. Infect. Dis. 2008, 198, 1202–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, S.E.; Staalsoe, T.; Arthur, P.; Bulmer, J.N.; Tagbor, H.; Hviid, L.; Frost, C.; Riley, E.M.; Kirkwood, B.R. Maternal vitamin A supplementation and immunity to malaria in pregnancy in Ghanaian primigravids. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2005, 10, 1286–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, A.M.; Mugusi, F.M.; Etheredge, A.J.; Gunaratna, N.S.; Abioye, A.I.; Aboud, S.; Duggan, C.; Mongi, R.; Spiegelman, D.; Roberts, D.; et al. Vitamin A and zinc supplementation among pregnant women to prevent placental malaria: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in Tanzania. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 96, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, M.; Gutman, J.; L’lanziva, A.; Otieno, K.; Juma, E.; Kariuki, S.; Ouma, P.; Were, V.; Laserson, K.; Katana, A.; et al. Intermittent screening and treatment or intermittent preventive treatment with dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine versus intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine for the control of malaria during pregnancy in western Kenya: An open-label, three-group, randomized controlled superiority trial. Lancet 2015, 386, 2507–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Divala, T.H.; Mungwira, R.G.; Mawindo, P.M.; Nyirenda, O.M.; Kanjala, M.; Ndaferankhande, M.; Tsirizani, L.E.; Masonga, R.; Muwalo, F.; Potter, G.E.; et al. A Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial of Chloroquine as Chemoprophylaxis or Intermittent Preventive Therapy to Prevent Malaria in Pregnancy in Malawi. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolan, G.; Ter Kuile, F.O.; Jacoutot, V.; White, N.J.; Luxemburger, C.; Malankirii, L.; Chongsuphajaisiddhi, T.; Nosten, F. Bed nets for the prevention of malaria and anaemia in pregnancy. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1993, 87, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filler, S.J.; Kazembe, P.; Thigpen, M.; Macheso, A.; Parise, M.E.; Newman, R.D.; Steketee, R.W.; Hamel, M. Randomized trial of 2-dose versus monthly sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine intermittent preventive treatment for malaria in HIV-positive and HIV-negative pregnant women in Malawi. J. Infect. Dis. 2006, 194, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, R.; Mombo-Ngoma, G.; Ouédraogo, S.; Kakolwa, M.A.; Abdulla, S.; Accrombessi, M.; Aponte, J.J.; Akerey-Diop, D.; Basra, A.; Briand, V.; et al. Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy with mefloquine in HIV-negative women: A multicentre randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2014, 11, e1001733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagannathan, P.; Kakuru, A.; Okiring, J.; Muhindo, M.K.; Natureeba, P.; Nakalembe, M.; Opira, B.; Olwoch, P.; Nankya, F.; Ssewanyana, I.; et al. Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine for intermittent preventive treatment of malaria during pregnancy and risk of malaria in early childhood: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayentao, K.; Kodio, M.; Newman, R.D.; Maiga, H.; Doumtabe, D.; Ongoiba, A.; Coulibaly, D.; Keita, A.S.; Maiga, B.; Mungai, M.; et al. Comparison of intermittent preventive treatment with chemoprophylaxis for the prevention of malaria during pregnancy in Mali. J. Infect. Dis. 2005, 191, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ter Kuile, F.O.; Kolczak, M.S.; Nahlen, B.L.; Friedman, J.F.; Shi, Y.P.; Phillips-Howard, P.A.; Hawley, W.A.; Lal, A.A.; Vulule, J.M.; Kariuki, S.K.; et al. Reduction of malaria during pregnancy by permethrin-treated bed nets in an area of intense perennial malaria transmission in western Kenya. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2003, 68, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Farzeen, M.; Hafeez, A.; Achakzai, B.K.; Vankwani, M.; Lal, M.; Iqbal, R.; Somrongthong, R. Effectiveness of a health education intervention on the use of long-lasting insecticidal nets for the prevention of malaria in pregnant women of Pakistan: A quasi-experimental study. Malar. J. 2020, 19, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingani, M.; Zango, S.H.; Valéa, I.; Samadoulougou, S.; Somé, G.; Sanou, M.; Kaboré, B.; Rouamba, T.; Sorgho, H.; Tahita, M.C.; et al. Effects of maternal antenatal treatment with two doses of azithromycin added to monthly sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine for the prevention of low birth weight in Burkina Faso: An open-label randomized controlled trial. Malar. J. 2023, 22, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madanitsa, M.; Barsosio, H.C.; Minja, D.T.; Mtove, G.; Kavishe, R.A.; Dodd, J.; Saidi, Q.; Onyango, E.D.; Otieno, K.; Wang, D.; et al. Effect of monthly intermittent preventive treatment with dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine with and without azithromycin versus monthly sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine on adverse pregnancy outcomes in Africa: A double-blind randomized, partly placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2023, 401, 1020–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlugu, E.M.; Minzi, O.; Kamuhabwa, A.A.R.; Aklillu, E. Effectiveness of intermittent preventive treatment with dihydroartemisinin-piperaqunine against malaria in pregnancy in tanzania: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 110, 1478–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, B.R.; Benjamin, J.M.; Tobe, R.; Ome-Kaius, M.; Yadi, G.; Kasian, B.; Kong, C.; Robinson, L.J.; Laman, M.; Mueller, I.; et al. A randomized open-label evaluation of the anti-malarial prophylactic efficacy of azithromycin-piperaquine versus sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in pregnant Papua New Guinean women. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njagi, J.K.; Magnussen, P.; Estambale, B.; Ouma, J.; Mugo, B. Prevention of Anaemia in pregnancy using insecticide-treated bednets and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in a highly malarious area of Kenya: A randomized controlled trial. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2003, 97, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosten, F.; ter Kuile, F.; Maelankiri, L.; Chongsuphajaisiddhi, T.; Nopdonrattakoon, L.; Tangkitchot, S.; Boudreau, E.; Bunnag, D.; White, N.J. Mefloquine prophylaxis prevents malaria during pregnancy: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Infect. Dis. 1994, 169, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labama Otuli, N.; Marini Djang’eing’a, R.; Losimba Likwela, J.; Bosenge Nguma, J.D.; Maindo Alongo, M.A.; Ahuka Ona Longombe, A.; Mbutu Mango, B.; Bono, D.M.N.; Mokili, J.L.; Manga Okenge, J.P. Efficacy and safety of malarial prophylaxis with mefloquine during pregnancy in Kisangani, Democratic Republic of Congo: A randomized clinical trial. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 87, 3115–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COSMIC Consortium. Community-based malaria screening and treatment for pregnant women receiving standard intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine: A multicenter (The Gambia, Burkina Faso, and Benin) cluster-randomized controlled trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 68, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steketee, R.W.; Wirima, J.J.; Hightower, A.W.; Slutsker, L.; Heymann, D.L.; Breman, J.G. The effect of malaria and malaria prevention in pregnancy on offspring birthweight, prematurity, and intrauterine growth retardation in rural Malawi. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1996, 55 (Suppl. S1), 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, E.N.L.; Maude, G.H.; Binka, F.N. The impact of insecticide-treated bednets on malaria and anaemia in pregnancy in Kassena-Nankana district, Ghana: A randomized controlled trial. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2001, 6, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajubi, R.; Huang, L.; Jagannathan, P.; Chamankhah, N.; Were, M.; Ruel, T.; Koss, C.; Kakuru, A.; Mwebaza, N.; Kamya, M.; et al. Antiretroviral therapy with efavirenz accentuates pregnancy-associated reduction of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine exposure during malaria chemoprevention. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 102, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roh, M.E.; Oundo, B.; Dorsey, G.; Shiboski, S.; Gosling, R.; Glymour, M.M.; Staedke, S.G.; Bennett, A.; Sturrock, H.; Mpimbaza, A. A quasi-experimental study estimating the impact of long-lasting insecticidal nets with and without piperonyl butoxide on pregnancy outcomes. Malar. J. 2022, 21, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akinyotu, O.; Bello, F.; Abdus-Salam, R.; Arowojolu, A. Comparative study of mefloquine and sulphadoxine–pyrimethamine for malaria prevention among pregnant women with HIV in southwest Nigeria. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 142, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinyotu, O.; Bello, F.; Abdus-Salam, R.; Arowojolu, A. A randomized controlled trial of azithromycin and sulphadoxine–pyrimethamine as prophylaxis against malaria in pregnancy among human immunodeficiency virus–positive women. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 113, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsosio, H.C.; Madanitsa, M.; Ondieki, E.D.; Dodd, J.; Onyango, E.D.; Otieno, K.; Wang, D.; Hill, J.; Mwapasa, V.; Phiri, K.S.; et al. Chemoprevention for malaria with monthly intermittent preventive treatment with dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine in pregnant women living with HIV on daily co-trimoxazole in Kenya and Malawi: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2024, 403, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, R.; Desai, M.; Macete, E.; Ouma, P.; Kakolwa, M.A.; Abdulla, S.; Aponte, J.J.; Bulo, H.; Kabanywanyi, A.M.; Katana, A.; et al. Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy with mefloquine in HIV-infected women receiving cotrimoxazole prophylaxis: A multicenter randomized placebo-controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2014, 11, e1001735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manirakiza, A.; Tondeur, L.; Ketta, M.Y.B.; Sepou, A.; Serdouma, E.; Gondje, S.; Bata, G.G.B.; Boulay, A.; Moyen, J.M.; Sakanga, O.; et al. Cotrimoxazole versus sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine for intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in HIV-infected pregnant women in Bangui, Central African Republic: A pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2021, 26, 1314–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denoeud-Ndam, L.; Zannou, D.M.; Fourcade, C.; Taron-Brocard, C.; Porcher, R.; Atadokpede, F.; Komongui, D.G.; Dossou-Gbete, L.; Afangnihoun, A.; Ndam, N.T.; et al. Cotrimoxazole prophylaxis versus mefloquine intermittent preventive treatment to prevent malaria in HIV-infected pregnant women: Two randomized controlled trials. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2014, 65, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofin, I.O.; Spiegelman, D.; Aboud, S.; Duggan, C.; Danaei, G.; Fawzi, W.W. Supplementation with multivitamins and vitamin A and incidence of malaria among HIV-infected Tanzanian women. Am. J. Ther. 2014, 67 (Suppl. S4), S173–S178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natureeba, P.; Kakuru, A.; Muhindo, M.; Ochieng, T.; Ategeka, J.; Koss, C.A.; Plenty, A.; Charlebois, E.D.; Clark, T.D.; Nzarubara, B.; et al. Intermittent preventive treatment with dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine for the prevention of malaria among HIV-infected pregnant women. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 216, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nambozi, M.; Kabuya, J.-B.B.; Hachizovu, S.; Mwakazanga, D.; Mulenga, J.; Kasongo, W.; Buyze, J.; Mulenga, M.; Van Geertruyden, J.-P.; D’alessandro, U. Artemisinin-based combination therapy in pregnant women in Zambia: Efficacy, safety and risk of recurrent malaria. Malar. J. 2017, 16, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Church, J.A.; Fitzgerald, F.; Walker, A.S.; Gibb, D.M.; Prendergast, A.J. The expanding role of co-trimoxazole in developing countries. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkley, J.A.; Ngari, M.; Thitiri, J.; Mwalekwa, L.; Timbwa, M.; Hamid, F.; Ali, R.; Shangala, J.; Mturi, N.; Jones, K.D.J.; et al. Daily co-trimoxazole prophylaxis to prevent mortality in children with complicated severe acute malnutrition: A multicentre, double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Glob. Health 2016, 4, e464–e473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, A.J.; Mwaba, P.; Chintu, C.; Mwinga, A.; Darbyshire, J.H.; Zumla, A. Role of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis in reducing mortality in HIV infected adults being treated for tuberculosis: Randomized clinical trial. BMJ 2008, 337, a257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banda, C.G.; Nkosi, D.; Allen, E.; Workman, L.; Madanitsa, M.; Chirwa, M.; Kapulula, M.; Muyaya, S.; Munharo, S.; Tarning, J.; et al. Impact of dolutegravir-based antiretroviral therapy on piperaquine exposure following dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnant women living with HIV. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e0058422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlagenhauf, P.; Adamcova, M.; Regep, L.; Schaerer, M.T.; Rhein, H.-G. The position of mefloquine as a 21st century malaria chemoprophylaxis. Malar. J. 2010, 9, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, R.; Pons-Duran, C.; Piqueras, M.; Aponte, J.J.; Ter Kuile, F.O.; Menéndez, C. Mefloquine for preventing malaria in pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 3, CD011444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, R.; Hellgren, U.; Greenwood, B.; Menéndez, C. Mefloquine safety and tolerability in pregnancy: A systematic literature review. Malar. J. 2014, 13, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.S.; Rahi, M.; Ranjan, V.; Sharma, A. Mefloquine as a prophylaxis for malaria needs to be revisited. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2021, 17, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, C.; Powers, H.; Lamb, W.; Gelman, W.; Webb, E. Effect of supplementary vitamins and iron on malaria indices in rural Gambian children. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1987, 81, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, E.L.; Rosenthal, P.J. Apicoplast translation, transcription and genome replication: Targets for anti-malarial antibiotics. Trends Parasitol. 2008, 24, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, E.L.; Rosenthal, P.J. Multiple antibiotics exert delayed effects against the Plasmodium falciparum apicoplast. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 3485–3490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krudsood, S.; Silachamroon, U.; Wilairatana, P.; Singhasivanon, P.; Phumratanaprapin, W.; Chalermrut, K.; Phophak, N.; Popa, C. A randomized clinical trial of combinations of artesunate and azithromycin for treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Thailand. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2000, 31, 801–807. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, R.; Ansah, P.; Sagara, I.; Sie, A.; Tiono, A.B.; Djimde, A.A.; Zhao, Q.; Robbins, J.; Penali, L.K.; Ogutu, B. Comparison of azithromycin plus chloroquine versus artemether-lumefantrine for the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in children in Africa: A randomized, open-label study. Malar. J. 2015, 14, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).