Abstract

Mycoplasmapneumoniae is one of the major causative pathogens of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP). M. pneumoniae CAP is clinically and radiologically distinct from bacterial CAPs. One feature of the Japanese Respiratory Society (JRS) guidelines is a trial to be carried out to differentiate between M. pneumoniae pneumonia and bacterial pneumonia for the selection of antibiotics. The purpose of the present study was to clarify the clinical and radiological differences of the M. pneumoniae CAP and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) CAP. This study was conducted at 5 institutions and assessed a total of 210 patients with M. pneumoniae CAP and 956 patients with COVID-19 CAP. The median age was significantly younger in patients with M. pneumoniae CAP than COVID-19 CAP. Among the clinical symptoms, cough and sputum were observed more frequently in patients with M. pneumoniae CAP than those with COVID-19 CAP. However, the diagnostic specificity of these findings was low. In contrast, loss of taste and anosmia were observed in patients with COVID-19 CAP but not observed in those with M. pneumoniae CAP. Bronchial wall thickening and nodules (tree-in-bud and centrilobular), which are chest computed tomography (CT) features of M. pneumoniae CAP, were rarely observed in patients with COVID-19 CAP. Our results demonstrated that there were two specific differences between M. pneumoniae CAP and COVID-19 CAP: (1) the presence of loss of taste and/or anosmia and (2) chest CT findings.

1. Introduction

Mycoplasmapneumoniae is one of the major causative pathogens of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and the most frequent pathogen in atypical pneumonia [1]. Epidemiological studies in Japan have demonstrated that the incidence of M. pneumoniae pneumonia is the second-to-third leading pathogen of CAP, accounting for as many as 10–30% of all cases of CAP [2,3,4]. Although pneumonia due to M. pneumoniae is usually of mild-to-moderate severity, some cases are known to develop into severe, life-threatening pneumonia [1,2,3,4]. Underlying conditions, clinical symptoms, laboratory data, and radiologic findings of M. pneumoniae pneumonia are different from other bacterial pneumonia [5,6]. Thus, the Japanese Respiratory Society (JRS) pneumonia guidelines proposed a differential diagnosis between other bacterial and M. pneumoniae pneumonia for the selection of an appropriate antibiotic for the management of CAP [2]. In addition, clinical findings of M. pneumoniae pneumonia are clearly different from Legionella CAP [7].

Since 2020, the novel, severe, acute respiratory syndrome, coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has become the most important pathogen in CAP [8]. The purpose of the present study was to clarify the clinical and radiological differences of M. pneumoniae CAP and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) CAP.

2. Subjects and Methods

2.1. Study Population

The present study was conducted at five institutions (Kansai Medical University Hospital, Kansai Medical University Medical Center, Kansai Medical University Kori Hospital, Kansai Medical University Kuzuha Hospital, and Kansai Medical University Temmabashi General Clinic) between January 2017 and December 2021. We enrolled adult patients consecutively diagnosed with CAP, defined in accordance with the JRS guidelines [2]. The diagnosis was based on clinical signs and symptoms (cough, fever, productive sputum, dyspnea, chest pain, or abnormal breath sounds) and radiographic pulmonary abnormalities that were at least segmental and were not as a result of pre-existing or other known causes. Exclusion criteria included the following: immunosuppressive illness (i.e., HIV positive, neutropenia secondary to chemotherapy, use of >20 mg/day prednisone or other immunosuppressive agents, and history of organ transplant); hospitalization in the preceding 90 days; residence in a nursing home or extended care facility; receiving regular endovascular treatment as an outpatient (dialysis, antibiotic therapy, chemotherapy, immunosuppressant therapy); and active tuberculosis. All cases of pneumonia occurring more than three days after hospitalization were considered nosocomial and were excluded.

M. pneumoniae was diagnosed using positive culture and/or real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) results from nasopharyngeal swab specimens and/or a four-fold rise in the antibody titer level between paired sera. COVID-19 was diagnosed with positive PCR results from sputum or nasopharyngeal swab specimens in accordance with the protocol recommended by the National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan.

The severity of pneumonia was evaluated using predictive rules via the A-DROP system (a 6-point scoring system) proposed by the JRS guidelines: age over 70 years in men and over 75 years in women, dehydration, respiratory failure, orientation disturbance, and low blood pressure [2]. Patients were stratified into four severity classes: 0 point = mild, 1 or 2 points = moderate, 3 points = severe, and 4 or 5 points = extremely severe. The time between the clinical onset of pneumonia (fever and/or other symptoms) and judgement of pneumonia severity ranged from 1 to 14 days (mean, 4.8 days) for COVID-19 pneumonia and from 1 to 10 days (mean, 5.2 days) for M. pneumoniae pneumonia. Pneumonia severity score was judged before any treatment against both M. pneumoniae and COVID-19 pneumonia.

High-resolution computed tomography (CT) was performed in all patients with 1-mm collimation at 10-mm intervals. Informed consent was obtained from all patients, and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kansai Medical University (approval number 2020319).

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Discrete variables are expressed as counts (percentages) and continuous variables as medians and interquartile ranges. Frequencies were compared using Fisher’s exact test. Between-group comparisons of normally distributed data were performed using Student’s t-test. Skewed data were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis Patients

The data of a total of 210 patients with M. pneumoniae CAP and 956 patients with COVID-19 CAP were analyzed. Cases of pneumonia mixed with other microorganisms were excluded from the study. During the study period, other microbiological diagnosis was established in 398 patients. The most common pathogens were Streptococcus pneumoniae, found in 281 cases, followed by Haemophilus influenzae in 93 cases, Moraxella catarrhalis in 21 cases and Staphylococcus aureus in 16 cases. Dual pathogens were detected in 34 cases. Of the 956 patients with COVID-19 CAP, 260 had lineage B.1.1.7, also known as the Alpha variant, and 274 had lineage B.1.617, also known as the Delta variant.

3.2. Clinical Presentation of M. pneumoniae CAP and COVID-19 CAP

Table 1 shows the underlying conditions and clinical findings of patients in the M. pneumoniae CAP and COVID-19 CAP groups at the first examination. The median age was significantly younger in patients with M. pneumoniae CAP than those with COVID-19 CAP. Among comorbid illnesses at baseline, the frequency of diabetes mellitus was significantly higher in patients with COVID-19 CAP than those with M. pneumoniae CAP.

Table 1.

Underlying conditions and clinical findings in patients with Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia and COVID-19 pneumonia at the first examination.

Respiratory symptoms such as cough, sputum production, sore throat and chest pain were observed more frequently in patients with M. pneumoniae CAP than those with COVID-19 CAP. Cough is usually stubborn in M. pneumoniae CAP, but not in COVID-19 CAP. In contrast, loss of taste and anosmia were observed in patients with COVID-19 CAP, but not observed in those with M. pneumoniae CAP. Interestingly, the presence of runny nose was low frequency in both M. pneumoniae CAP and COVID-19 CAP.

With regard to pneumonia severity, approximately 90% of cases were mild-to-moderate severity in both CAP groups. The number of patients admitted to the intensive care unit and patients with in-hospital mortality were higher in patients with COVID-19 CAP than M. pneumoniae CAP. These findings were caused by the lack of a specific antimicrobial agent against COVID-19.

Of the 210 patients with M. pneumoniae CAP, 84 patients received minocycline, 64 patients received macrolides and 62 patients received quinolones. Eighteen severe patients received glucocorticoid in addition to antibiotics. Of the 956 patients with COVID-19 CAP, 648 patients received antiviral therapy, 258 patients received antibiotics and 619 patients received glucocorticoid.

3.3. Clinical Presentation of M. pneumoniae CAP and Age- and Gender-Matched COVID-19 CAP

Table 2 shows the underlying conditions and clinical findings of patients in the M. pneumoniae CAP and age- and gender-matched patients with COVID-19 CAP at the first examination. Among clinical symptoms, cough and sputum were observed more frequently in patients with M. pneumoniae CAP than those with COVID-19 CAP. In addition, loss of taste and anosmia were observed in one-third of patients with COVID-19 CAP.

Table 2.

Underlying conditions and clinical findings in patients with Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia and age and gender matched COVID-19 pneumonia at the first examination.

Although pneumonia severity was identical between the unmatched COVID-19 CAP group and matched COVID-19 CAP group, the number of patients admitted to intensive care units and patients with in-hospital mortality were significantly reduced in patients with the matched COVID-19 CAP group.

3.4. Chest CT Findings

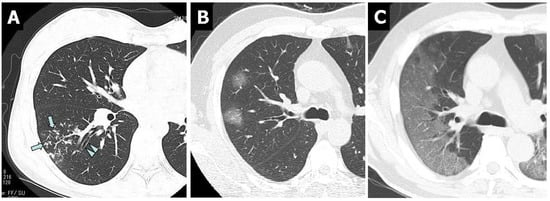

At the first CT examination within 10 days after symptom onset, bronchial wall thickening (83.8%) was observed most frequently, followed by nodules (tree-in-bud and centrilobular) (81.4%) in patients with M. pneumoniae CAP. In contrast to M. pneumoniae CAP, bronchial wall thickening and nodules (tree-in-bud and centrilobular) were rarely observed in patients with COVID-19 CAP (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Non-contrast-enhanced thin-section axial images of the lungs in patients with M. pneumoniae pneumonia (A) and COVID-19 pneumonia (B,C). (A) Chest CT scan of a 46-year-old female showed nodules (tree-in-bud, arrows) and bronchial wall thickening (arrowheads). (B) Chest CT scan of a 46-year-old man showed bilateral and multifocal rounded GGO. (C) Chest CT in a 56-year-old man showed bilateral and peripheral GGO with superimposed interlobular septal thickening and crazy-paving appearance.

4. Discussion

Patients with M. pneumoniae CAP have several distinct clinical features compared to patients with CAP due to other pathogens. M. pneumoniae infection occurs predominantly in school-aged children and younger adults. Cough is the main symptom, which is usually paroxysmal and often persistent. Peripheral white blood cell (WBC) count is usually normal at less than 10,000/µL. Thus, the JRS extracted six parameters from patients with M. pneumoniae pneumonia using multiple regression analysis [5]. Several studies have supported the usefulness of the JRS scoring system for distinguishing between M. pneumoniae pneumonia and other bacterial pneumonia [9,10]. In the present study, the sensitivity rates for presumptive diagnosis of M. pneumoniae CAP and COVID-19 CAP were 86.2% and 69.9%, respectively, based on four or more parameters of the criteria. The matching rates in two parameters, (1) age <60 years and (2) presence of stubborn cough, were significantly lower in COVID-19 CAP than in M. pneumoniae CAP. When the age- and gender-matched groups, only one parameter, the frequency of stubborn cough, was different between the two groups.

To increase the diagnostic sensitivity, in addition to the JRS scoring system, chest CT findings were a useful tool as an auxiliary diagnostic test to differentiate between M. pneumoniae CAP and bacterial CAP for the selection of antibiotics [11,12]. Typical chest CT findings of M. pneumoniae pneumonia resemble a combination of bronchial wall thickening and tree-in-bud and centrilobular nodules and/or ground-glass opacity with lobular distribution [11,12]. In contrast, bronchial wall thickening and nodules (tree-in-bud and centrilobular) were rarely observed in patients with COVID-19 CAP. These findings of chest CT among patients with COVID-19 pneumonia were consistent with previous reports [13,14,15]. Thus, physicians can differentiate M. pneumoniae CAP from COVID-19 CAP using chest CT findings.

A similar investigation was performed in pediatric patients using 80 patients with COVID-19 and 95 patients with M. pneumoniae CAP by Guo et al. [16]. Compared to COVID-19 and M. pneumoniae, fever and cough are observed more common in M. pneumoniae CAP. COVID-19 patients presented remarkably increased alanine aminotransferase. The typical CT feature of COVID-19 was ground-glass opacity, and it was more common in COVID-19 patients. Our results of clinical symptoms are similar to Guo’s results, but not similar in laboratory data and CT findings. These differences may be caused by adults and children.

In conclusion, we found several differences between M. pneumoniae CAP and COVID-19 CAP. M. pneumoniae CAP is significantly more common in younger patients, and the average age of patients with COVID-19 CAP is higher than that of patients with M. pneumoniae CAP. Cough, especially stubborn cough, and sputum production were more frequently observed in patients with M. pneumoniae CAP. However, the diagnostic specificity of these findings was low. The specific differences between M. pneumoniae CAP and COVID-19 CAP were (1) the presence of loss of taste and/or anosmia and (2) chest CT findings.

Author Contributions

N.M., Y.N., M.O., N.F., A.Y., Y.I. and S.N. conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination and collected and managed the data, including quality control. N.M., Y.N. and S.N. drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed substantially to its revision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Kansai Medical University (approval number 2020319).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Waites, K.B.; Talkington, D.F. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and its role as a human pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2004, 17, 697–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Committee for The Japanese Respiratory Society guidelines for the management of respiratory infections. Guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults, revised edition. Respirology 2006, 11 (Suppl. 3), S79–S133. [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki, K.; Kawanami, T.; Yatera, K.; Fukuda, K.; Noguchi, S.; Nagata, S.; Nishida, C.; Kido, T.; Ishimoto, H.; Taniguchi, H.; et al. Significance of anaerobes and oral bacteria in community-acquired pneumonia. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyashita, N.; Fukano, H.; Mouri, K.; Fukuda, M.; Yoshida, K.; Kobashi, Y.; Niki, Y.; Oka, M. Community-acquired pneumonia in Japan: A prospective ambulatory and hospitalized patient study. J. Med. Microbiol. 2005, 54, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ishida, T.; Miyashita, N.; Nakahama, C. Clinical differentiation of atypical pneumonia using Japanese guidelines. Respirology 2007, 12, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyashita, N.; Fukano, H.; Yoshida, K.; Niki, Y.; Matsushima, T. Is it possible to distinguish between atypical pneumonia and bacterial pneumonia?: Evaluation of the guidelines for community-acquired pneumonia in Japan. Respir. Med. 2004, 98, 952–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyashita, N.; Higa, F.; Aoki, Y.; Kikuchi, T.; Seki, M.; Tateda, K.; Maki, N.; Uchino, K.; Ogasawara, K.; Kiyota, H.; et al. Clinical presentation of Legionella pneumonia: Evaluation of clinical scoring systems and therapeutic efficacy. J. Infect. Chemother. 2017, 23, 727–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.; Huang, B.; Shi, W.; Lu, R.; et al. China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, A.; Goto, H.; Kohno, S.; Matsushima, T.; Abe, S.; Aoki, N.; Shimokata, K.; Mikasa, K.; Niki, Y. Nationwide survey on the 2005 guidelines for the management of community-acquired adult pneumonia: Validation of differentiation between bacterial pneumonia and atypical pneumonia. Respir. Investig. 2012, 50, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Y.D.; Zhao, F.; Ren, L.L.; Song, S.F.; Liu, Y.M.; Zhang, J.Z.; Cao, B. Evaluation of the Japanese Respiratory Society guidelines for the identification of Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia. Respirology 2012, 17, 1131–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, S.; Ishida, T.; Togashi, K.; Niimi, A.; Koyama, H.; Ishimori, T.; Kobayashi, H.; Mishima, M. Differentiation of bacterial and non-bacterial community-acquired pneumonia by thin-section computed tomography. Eur. J. Radiol. 2009, 72, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyashita, N.; Sugiu, T.; Kawai, K.; Oda, K.; Yamaguchi, T.; Ouchi, K.; Kobashi, Y.; Oka, M. Radiographic features of Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia: Differential diagnosis and performance timing. BMC. Med. Imaging 2009, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, H.J.A.; Kwee, T.C.; Yakar, D.; Hope, M.D.; Kwee, R.M. Chest CT imaging signature of coronavirus disease 2019 infection: In pursuit of scientific evidence. Chest 2020, 158, 1885–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Zhang, N.; Xu, X. A systematic review of chest imaging in COVID-19. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2020, 10, 1058–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, S.; Kay, F.U.; Abbara, S.; Bhalla, S.; Chung, J.H.; Chung, M.; Henry, T.S.; Kanne, J.P.; Kligerman, S.; Ko, J.P.; et al. Radiological Society of North America Expert Consensus Document on reporting chest CT findings related to COVID-19: Endorsed by the Society of Thoracic Radiology, the American College of Radiology, and RSNA. Radiol. Cardiothoracic. Imaging. 2020, 2, e200152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Xia, W.; Peng, X.; Shao, J. Features discriminating COVID-19 from community-acquired pneumonia in pediatric patients. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 602083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).