Abstract

Glaucoma remains a frequent serious complication following cataract surgery in children. The optimal approach to management for ‘glaucoma following cataract surgery’ (GFCS), one of the paediatric glaucoma subtypes, is an ongoing debate. This review evaluates the various management options available and aims to propose a clinical management strategy for GFCS cases. A literature search was conducted in four large databases (Cochrane, PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science), from 1995 up to December 2021. Thirty-nine studies—presenting (1) eyes with GFCS; a disease entity as defined by the Childhood Glaucoma Research Network Classification, (2) data on treatment outcomes, and (3) follow-up data of at least 6 months—were included. Included papers report on GFCS treated with angle surgery, trabeculectomy, glaucoma drainage device implantation (GDD), and cyclodestructive procedures. Medical therapy is the first-line treatment in GFCS, possibly to bridge time to surgery. Multiple surgical procedures are often required to adequately control GFCS. Angle surgery (360 degree) may be considered before proceeding to GDD implantation, since this technique offers good results and is less invasive. Literature suggests that GDD implantation gives the best chance for long-term IOP control in childhood GFCS and some studies put this technique forward as a good choice for primary surgery. Cyclodestruction seems to be effective in some cases with uncontrolled IOP. Trabeculectomy should be avoided, especially in children under the age of one year and children that are left aphakic. The authors provide a flowchart to guide the management of individual GFCS cases.

1. Introduction

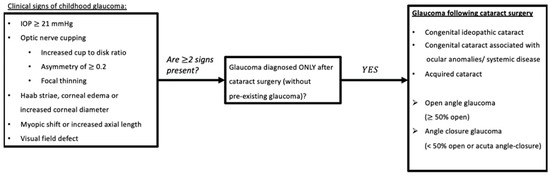

Former terms used to describe childhood glaucoma, including ‘developmental’, ‘congenital’, or ‘infantile’, were often not clearly defined [1,2,3]. Therefore, the Childhood Glaucoma Research Network Classification recently developed a system for the classification of paediatric glaucoma to unify nomenclature (Figure 1) [3]. This review focuses on the subtype known as glaucoma following cataract surgery (GFCS), which accounts for 18% of childhood glaucoma [4].

Figure 1.

Glaucoma Following Cataract Surgery based on Childhood Glaucoma Research Network classification algorithm. Childhood: based on national criteria, <18 years old (USA); <16 years old (UK, Europe, UNICEF) (reproduced with permission from Grajewski, World Glaucoma Association Consensus Series 9: Childhood glaucoma, Kugler publications 2013 [5]). Abbreviations: IOP = Intra-Ocular Pressure.

After cataract extraction in early life, both aphakic and pseudophakic eyes are at high and lifelong risk for the development of glaucoma (GFCS, formerly known as aphakic or pseudophakic glaucoma). The incidence depends on duration of follow-up, age at time of surgery, corneal diameter, surgical techniques, and the definition of glaucoma among studies [6,7,8]. In the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study (IATS), a randomized clinical trial of 114 infants with unilateral congenital cataract who were aged 1 to 6 months at surgery, the incidence of GFCS was 22% after 10 years of follow-up [9]. Improved surgical techniques for childhood cataract extraction have reduced the incidence of angle-closure GFCS. The predominant type, accounting for 75 to 94% of GFCS, now has an open angle configuration [10]. Unlike angle-closure glaucoma, which is diagnosed in the early postoperative period, the incidence of open-angle glaucoma is known to rise with increasing postsurgical follow-up, and its presentation may occur any time after initially uneventful surgery [11]. Consequently, it is imperative that these patients receive lifelong follow-up in order to protect their vision.

The pathophysiological mechanism by which secondary glaucoma develops in these patients, who have a history of paediatric cataract, is still unclear and thought to be of multifactorial origin. A mechanical and a chemical theory have been hypothesized: (1) the mechanical support to the trabecular meshwork is lost after lensectomy and contributes to decreased trabecular spaces, potentially reducing outflow facility, or (2) the influence of chemical substances from the vitreous cavity and retained lens material may alter trabecular meshwork morphology and gene expression [12,13,14]. Further, early lensectomy and early use of high-dose steroids may also lead to structural alteration of the trabecular meshwork and associated impairment of normal angle maturation [11,15].

Age at time of lensectomy and microcornea are the two risk factors most commonly associated with a higher prevalence of GFCS [16]. The optimal timing of lensectomy is still under debate because the increased risk of developing GFCS must be balanced against the risk of irreversible deprivation amblyopia [10]. Until a few years ago, it was thought that pseudophakia was a protective factor for the development of GFCS [17]. However, selection bias in the possibility that children selected for intraocular lens placement have largely been those at lower risk for glaucoma may explain the observed lower incidence of glaucoma in pseudophakia in some initial small or non-randomised studies [16]. The IoLunder 2 Study and the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study (IATS) showed that the risk of glaucoma development at 5 and 10 years post lensectomy, respectively, is similar for aphakic and pseudophakic patients [9,18,19].

GFCS is often difficult to manage, and it is generally associated with a poor prognosis. The first-line treatment for most GFCS cases is medical [11,20]. When surgical intervention is indicated, the optimal surgical approach is subject to debate. Many studies reporting treatment outcomes of childhood glaucoma in general are available, but studies that focus on this particular glaucoma subtype are limited, resulting in a lack of consensus. This review summarizes the literature on the various medical and surgical options available for the management of GFCS, with the aim to suggest an appropriate management strategy for specific clinical GFCS cases. This paper provides a flowchart which may assist ophthalmologists treating GFCS patients in clinical decision-making.

2. Materials and Methods

This literature review was registered and approved by KU Leuven. In performing this review, the PRISMA statement (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis) was followed [21].

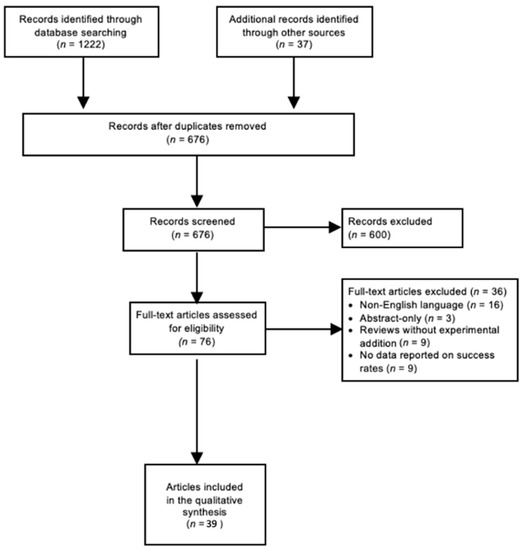

The databases Cochrane, PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science were systematically searched (from 1 January 1995 to 31 December 2021). A detailed search strategy for each database is presented in Appendix A. The individual references of each study were considered in order to identify additional relevant articles. Non-pertinent articles were rejected based on title and abstract screening. Thereafter, the full texts of the remaining articles were independently judged for eligibility by two independent reviewers (A.S., S.L.) according to the following inclusion criteria: the studies should (1) include eyes with GFCS; a disease entity as defined by the Childhood Glaucoma Research Network Classification (Figure 1), (2) report data on treatment outcomes, and (3) present follow-up data of at least six months after glaucoma therapy. Reviews that do not report original research results, non-English-language articles, and abstract-only articles were excluded. Inconsistencies were solved by consensus. The PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 2) gives details on the screening process. The authors performed a narrative synthesis because methodological heterogeneity precluded a meta-analysis. The Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine classification was used to determine the Level Of Evidence (LOE) of the included papers [22].

Figure 2.

Literature search: PRISMA Consort flow diagram. According to THE PRISMA Statement 2009 [19]. Abbreviations: PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; n = amount of articles.

3. Results

A total of 676 studies were screened using the described search strategy. At the end of the selection process, 39 articles were judged eligible for qualitative synthesis: 1 randomized controlled trial, 21 cohort studies, and 17 case series were included in the systematic review. In the following sections, summary tables of findings of included papers are provided. Medical therapy, angle surgery, trabeculectomy, glaucoma drainage device (GDD) implantation, and cyclodestructive procedures are mainly discussed. Five out of 39 studies described success rate with medication alone, 7 studies examined success rates of angle surgery, 8 studies examined success rates of trabeculectomy, 14 studies examined success rates of drainage implants, and 9 out of 39 studies examined success rates of cyclodestructive procedures.

3.1. Medical Treatment

Only five studies in which initial treatment was medical in all of the included eyes with GFCS clearly described their success rates with medication alone (Table 1) [23,24,25,26,27].

Table 1.

Relevant studies involving success rates with medications alone and the need for surgical treatment in GFCS eyes.

Success rates between the five available studies range from 17 to 73%, with those three reporting success rates of 40% and more having the largest study cohorts. Unlike PCG, which responds inadequately to medical therapy, these studies showed that long-term intra-ocular pressure (IOP) control can be reached with medication alone in some patients with GFCS. Medical therapy consists of topical medications and systemic medications, alone or in combination, in order to achieve the best possible result. Beta-blockers, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, miotics and prostaglandin analogues are the classes commonly used for treatment of GFCS [23,24]. In a retrospective series of 32 eyes with GFCS, the addition of echothiophate iodide (EI) 0.125%, a miotic, in combination with other medications reduced IOP about 33% over long-term follow-up. The side-effects of EI were limited to transient redness that did not necessitate cessation of treatment [27].

3.2. Surgical Treatment

According to the literature, surgery is required in 27–83% of GFCS cases (Table 1) [23,24,25,26]. Repeat surgery and multiple modalities are often indicated to avoid or at least slow down further glaucoma progression. Similar ratios regarding the number of required repeat surgeries are reported, with 30–40% of eyes needing only one surgery and more than half of included study eyes needing two or more sequential surgical interventions [23,24]. One study documented the need of four or more procedures in 7% of eyes after a follow-up period of 18.7 years [24].

Included papers report on GFCS treated with angle surgery, trabeculectomy, GDD implantation, and cyclodestructive procedures.

3.2.1. Angle Surgery

Data documenting this treatment modality in GFCS are limited and mostly presented by small retrospective cohorts with variably reported success rates (16–93%) (Table 2) [10,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Prior work found a success rate of only 16% after conventional angle surgery, including a 180-degee trabeculotomy or goniotomy [10]. This is in stark contrast with more recent studies in which success following angle surgery was achieved in the majority of eyes following a 360-degree trabeculotomy [28,29,30,32,33], with the most recent case series showing a success rate of 93% after a mean follow-up of 3.3 years [33]. The 360-degree trabeculotomy showed higher surgical success rates compared to conventional 180-degree goniotomy and trabeculotomy [29,32]. No visually devastating complications have been reported in the included studies.

Table 2.

Relevant studies involving angle surgery in GFCS eyes.

Less favourable outcomes were reported in GFCS eyes with peripheral anterior synechiae [28,30].

3.2.2. Trabeculectomy (+Antimetabolites)

Results of trabeculectomy + Mitomycin C in eyes with GFCS are variable but generally poor (Table 3) [10,23,34,35,36,37,38,39] with the largest cohort on this subject reporting a 25% success rate after a mean follow-up of 8.6 years [10].

Table 3.

Relevant studies involving trabeculectomy in GFCS eyes.

Certain patient-related factors have shown to be significant risk factors for trabeculectomy failure, including aphakia and age younger than one year, especially when combined [35].

The use of antimetabolites can improve success rates but at the cost of increased risk of complications, including blebitis and endophthalmitis [37].

3.2.3. Glaucoma Drainage Device Implantation

Most of the included studies report treatment outcomes of glaucoma drainage device implantation in eyes with GFCS with good success rates up to 95% (Table 4) [10,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. Pakravan et al. demonstrated a 90% success rate after one year of follow-up following a glaucoma drainage device implantation as a primary procedure in eyes with GFCS. At five years, the success rate had fallen to 72% [49]. Other reports, analysing the effectiveness of GDDs in GFCS patients, noted similarly good success rates [40,41,48].

Table 4.

Relevant studies involving glaucoma drainage device implantation in GFCS eyes.

A prospective randomized clinical trial (RCT) found that GDD treatment outcome is superior to trabeculectomy. This RCT compared Ahmed glaucoma implant + MMC (AGI + MMC) with trabeculectomy + MMC (T + MMC) as the primary procedure for treatment of GFCS in children under 16 years of age. Each group consisted of 15 aphakic eyes, and although no statistically significant differences were found between both groups, the results were more favourable in the GDD + MMC group. The overall success rate was higher (87% vs. 73%), and the overall complication rate was lower (27% vs. 40%) in the AGI+MMC group versus T + MMC group, respectively [38]. Similarly, a retrospective study which revealed success rates of 44% after GDD implantation still shows more encouraging results when compared to a 24.6% success rate in patients who underwent trabeculectomy [10].

Similar to trabeculectomy, younger age at time of GDD surgery is associated with less favourable treatment outcomes. Nevertheless, in patients under two years of age, when compared to T + MMC, it was found that GDD implantation offered a significantly greater chance of successful IOP control. At the age of six, IOP was controlled in 19% in the trabeculectomy + MMC group versus in 53% in the GDD group [53]. A recent study demonstrated that the presence of persistent fetal vasculature (PFV) affects the outcome in a negative way; PFV-related cataracts showed a lower survival rate of the Ahmed glaucoma valve and a higher complication rate versus non-PFV-related cataracts [51]. Unlike for trabeculectomy, lens status is not consistently reported to be a significant risk factor for GDD failure. Patients with GFCS who have had multiple previous ocular surgeries may be at higher risk for tube failure, with better reported relative success rates in eyes with only one previous operation (83%) compared to those having had more than two previous operations (42%) [43].

Complications commonly described in the included studies after GDD implantation include suprachoroidal haemorrhage, choroidal detachment, hypotony, tube-corneal contact, and retinal detachment.

3.2.4. Cyclodestructive Procedures

Moderate success rates have been reported after cyclodestructive procedures in GFCS eyes with uncontrolled (Table 5) [10,39,54,55,56,57,58,59,60]. The highest success rate (54%) was presented in a cohort of 35 aphakic or pseudophakic GFCS eyes, after a follow-up of 7.2 years [55].

Table 5.

Relevant studies involving cyclodestruction in GFCS eyes.

In the study of Schlote et al., cyclodestruction showed better outcomes in older patients than in younger patients [60]. No effect of prior glaucoma interventions was found [53,55,56]. No significant differences in success rates between aphakic and pseudophakic eyes were found [55,57]. The only finding repeatedly associated with reduced outcomes was a higher pretreatment IOP; those eyes may need more sessions of cyclodestruction in order to control the IOP [55,57].

Postoperative hypotony, chronic uveitis, and rarely phthisis are complications reported after cyclodestruction [10,39,54,55,56,57,58,59,60]. Aphakic eyes with GFCS after endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation were at higher risk of postoperative complications, including retinal detachment, compared to eyes with other types of glaucoma [59].

4. Discussion

Medical therapy should be tried first in GFCS cases since long-term IOP control can be reached with medication alone in some cases. For example, Bhola et al. noted that 73% of patients achieved IOP with medication alone after a mean follow-up of 18.7 years [24]. The choice of medication varies between clinicians and depends on efficacy, potential adverse effects, cost, and availability across different health systems [5]. Kraus et al. found that EI had an impressive IOP-lowering effect in children with GFCS. Unfortunately, this medication was discontinued in 2021 and is currently no longer commercially available [27]. The decision to proceed to surgery should be a well-argued one, because younger age is frequently associated with reduced surgical outcomes; hence, medical therapy should be considered the initial strategy of choice in GFCS, possibly to bridge the time to surgery. On the other hand, topical IOP-lowering drugs have a higher potential for systemic adverse effects, and adherence to complex regimens is more difficult in young age groups [10]. When IOP control is inadequate, surgery should not be delayed because of fear of poor results.

Surgical treatment modalities for GFCS include angle surgery (trabeculotomy and goniotomy), GDD implantation, trabeculectomy with MMC, and cyclodestructive procedures. Given their normal life expectancy, children with GFCS may need multiple repeat interventions. Hence, the development of a long-term surgical strategy allowing a step-wise escalation of risk is strongly advisable. Selecting the most appropriate operation technique is crucial since the primary surgical intervention chosen for the child is often his or her best chance for long-term success.

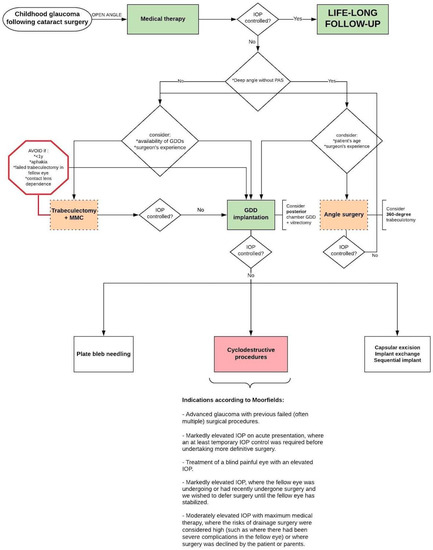

Some patient-related factors are associated with reduced outcomes of particular surgical procedures, making particular procedures more suitable than others for individual clinical cases. Since glaucoma surgery suffers from poor success rates in GFCS, knowledge about these patient-related factors affecting the outcomes helps in choosing the optimal approach for each individual patient. Considering the identified risk factors after reviewing the current literature, the authors suggest a flowchart for the management of GFCS (Figure 3). The flowchart was adapted from a previously published flowchart (Childhood Glaucoma, 9th Consensus Report of the World Glaucoma Association) [16].

Figure 3.

Suggested flowchart for the management of childhood GFCS with open-angle configuration (adapted with permission from Grigg, World Glaucoma Association Consensus Series 9: Childhood glaucoma, Kugler publications 2013 [16]). Abbreviations: IOP = Intra-Ocular Pressure; MMC = Mitomycin C; y = years; GDD = Glaucoma drainage device; PAS = peripheral anterior synechiae.

It should be stressed that this is not intended as a pre-set algorithm that must be followed unconditionally as clinical decision-making will always be influenced by several factors (including surgeon preference/experience and local facilities/equipment availability). The next paragraphs may clarify the flowchart by summarising and interpreting the main findings of each surgical option.

Although angle surgery is more often reserved for cases of PCG, some recent studies have shown promising results in GFCS (Table 2); these studies are associated with the recent resurgence of interest in this treatment modality. This is not surprising since angle dysgenesis plays a role in the pathogenesis of GFCS and angle surgery addresses the physiological outflow pathways. In particular, 360-degree trabeculotomy maximises the therapeutic effect by providing both a temporal and nasal trabeculotomy at initial surgery, whether by two-site rigid probe or via microcatheter assisted suture placement. This technique is less invasive when compared to trabeculectomy, GDD implantation, and cyclodestructive procedures. Additionally, 360-degree trabeculotomy is beneficial because it spares the conjunctiva for potential future surgeries. Angle surgery was not mentioned in the previous flowchart of suggested management approach in 2013 (Childhood Glaucoma, 9th Consensus Report of the World Glaucoma Association) [16]. However, studies after 2013 showed good success rates in GFCS cases and the authors of this review suggest that a 360-degree trabeculotomy could be attempted as the primary surgical procedure in cases of relatively early-onset GFCS when the angle is deep and in the absence of peripheral anterior synechiae [20]. Some studies in the literature, mainly in the form of case reports, describe the performance of goniotomy with a 23 or 25 gauge straight cystotome or a Sinskey hook. These devices are much less expensive than other devices on the market for goniotomy such as Kahook blade, Goniotome, and Trabectome. It is a good option in resource-poor areas that cannot afford more expensive goniotomy devices [61,62,63,64,65,66].

Trabeculectomy has traditionally been the first choice of the remaining surgical options in childhood glaucoma, but it has shown limited success in GFCS (Table 3). Due to this limited success rates, the concern about bleb-related complications post trabeculectomy + MMC and due to the high success rates of up to 95% following GDD implantation in GFCS eyes (Table 4), there is a growing interest in selecting a GDD at primary surgery. Although large RCTs are lacking in this domain, the current literature does suggest that GDD implantation gives the best chance for long-term IOP control. Some studies put this technique forward as a good choice for primary surgery [38,44,48,49]. Where trabeculectomy was still considered as the primary procedure of choice in the previous flowchart (Childhood Glaucoma, 9th Consensus Report of the World Glaucoma Association) [16], the authors of this review suggest that glaucoma drainage implantation is preferred over trabeculectomy in GFCS cases. The complication of tube-cornea contact and corneal decompensation can be minimised by placing the tube in the sulcus in pseudophakic patients or pars plana with concomitant (or prior) vitrectomy in aphakic/pseudophakic patients [41].

Cyclodestructive procedures (Table 5), plate bleb needling, and exchange or sequential implant have proven to be effective in patients with uncontrolled IOP after a GDD implantation [67,68,69]. Cyclodestruction is generally considered when other options have failed. Although initially reserved for end-stage glaucomatous eyes in which multiple procedures have failed, indications for this procedure have expanded, and it can be considered an initial surgical approach in selected cases (Figure 3, indications according to Moorfields).

The aetiology of GFCS is largely not understood and thought to be multifactorial in origin. A significant reduction in Schlemm’s canal (SC) size and loss of SC dilation during physiologic accommodation in children with GFCS has recently been demonstrated, suggesting that targeting SC may potentially offer a new management approach [70] 3. Future research directed at better understanding the underlying aetiology is necessary since such an understanding may have implications for the clinical management of GFCS.

One of the major strengths of this review is that it specifically focuses on the management of the glaucoma subtype GFCS. Many reports in the literature offer a comparison of different procedures for childhood glaucoma in general; however, the mix of diagnoses of subjects differs between studies and different aetiologies of glaucoma do not respond in the same manner to a particular surgical intervention. For that reason, the authors chose to extract and analyse the outcomes separately for patients with GFCS. However, it must be noted that the differing study results are limited by their retrospective nature, varying study populations (including patient age and the severity of glaucoma), varying techniques and devices, and varying number of previous surgeries as well differences in the definitions of success and failure.

5. Conclusions

Although medical therapy is usually the first-line treatment for GFCS, multiple surgical procedures are often required to adequately control the condition. It might be worth trying a 360-degree trabeculotomy before proceeding to glaucoma drainage device implantation, since this technique offers good results and is less invasive. Glaucoma drainage device implantation seems to give the best chance for long-term IOP control in childhood GFCS and some studies put this technique forward as a good choice for primary surgery. Cyclodestruction seems to be effective in some GFCS cases with uncontrolled IOP after a glaucoma drainage device implantation. Trabeculectomy offers poor success rates in children with GFCS, especially in children under the age of one year and children that are left aphakic. The authors provide a flowchart to guide the management of individual GFCS cases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. and E.V.; methodology, A.-S.S. and S.L.; software, not applicable; validation, S.L., E.V., I.S., I.C. and J.G.; formal analysis, not applicable; investigation, A.-S.S. and S.L.; resources, not applicable; data curation, not applicable; writing—original draft preparation, A.-S.S.; writing—review and editing, S.L., E.V., I.S., I.C. and J.G.; visualization, E.V.; supervision, S.L., E.V., I.S., I.C. and J.G.; project administration, E.V.; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Search conducted on 23 June 2019–last updated on 31 December 2021 in Pubmed (Medline): (“Glaucoma”[Mesh] OR Glaucoma[tiab]) AND ((“Aphakia, Postcataract”[Mesh] OR “Aphakia”[Mesh] OR Aphak*[tiab]) OR (“Pseudophakia”[Mesh] OR “Pseudophak”[tiab])) AND (“therapy”[Mesh] OR therap*[tiab] OR treatment[tiab] OR management[tiab]).

Search conducted on 23 June 2019–last updated on 31 December 2021 in Embase: Concept 1: (‘disease management’/exp OR ‘management’:ti,ab) AND Concept 2: (‘aphakic glaucoma’/exp OR ‘aphakic’:ti,ab) OR Concept 3: (‘pseudophakic glaucoma’ OR ‘pseudophak’:ti,ab) Combine.

Search conducted on 23 June 2019–last updated on 31 December 2021 in Web of Science Concept 1: TS = (Glaucoma AND Aphak* OR Pseuphak*) Concept 2: TS = (therap*OR treatment OR management) Combine.

Search conducted on 23 June 2019–last updated on 31 December 2021 in Cochrane: Concept 1: disease management AND Concept 2: aphakic glaucoma OR Concept 3: pseudophakic glaucoma.

References

- Roy, F.H. Comprehensive Developmental Glaucoma Classification. Ann. Ophthalmol. 2005, 37, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, H.H.; Walton, D.S. Clinical Classification of Childhood Glaucomas. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2010, 128, 680–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thau, A.; Lloyd, M.; Freedman, S.; Beck, A.; Grajewski, A.; Levin, A.V. New classification system for pediatric glaucoma. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2018, 29, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoguet, A.; Grajewski, A.; Hodapp, E.; Chang, T.C.P. A retrospective survey of childhood glaucoma prevalence according to Childhood Glaucoma Research Network classification. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 64, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinreb, R.N.; Grajewski, A.L.; Papadopoulos, M. Definition, classification, differential diagnosis. In Childhood Glaucoma: The 9th Consensus Report of the World Glaucoma Association; Kugler Publications: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rabiah, P.K. Frequency and predictors of glaucoma after pediatric cataract surgery. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2004, 137, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.C.; Chen, P.P.; Francis, B.A.; Junk, A.K.; Smith, S.D.; Singh, K.; Lin, S.C. Pediatric Glaucoma Surgery. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 2107–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamy, B.N.; Billson, F.; Martin, F.; Donaldson, C.; Hing, S.; Jamieson, R.; Grigg, J.; Smith, J.E.H. Secondary glaucoma after paediatric cataract surgery. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 91, 1627–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, S.F.; Beck, A.D.; Nizam, A.; Vanderveen, D.K.; Plager, D.A.; Morrison, D.G.; Drews-Botsch, C.D.; Lambert, S.R.; Infant Aphakia Treatment Study Group. Glaucoma-Related Adverse Events at 10 Years in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021, 139, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, D.S.; Chen, T.C.; Bhatia, L.S. Aphakic Glaucoma After Congenital Cataract Surgery. Int. Ophthalmol. Clin. 2008, 48, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.K.; Netland, P.A. Glaucomas in aphakia and pseudophakia after congenital cataract surgery. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2006, 52, 93–102. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15510457 (accessed on 9 April 2019).

- Asrani, S.; Freedman, S.; Hasselblad, V.; Buckley, E.G.; Egbert, J.; Dahan, E.; Parks, M.; Johnson, D.; Maselli, E.; Gimbel, H.; et al. Does primary intraocular lens implantation prevent ‘aphakic’ glaucoma in children? J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2000, 4, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, I.; Shmoish, M.; Walton, D.S.; Levenberg, S. Interactions between Trabecular Meshwork Cells and Lens Epithelial Cells: A Possible Mechanism in Infantile Aphakic Glaucoma. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008, 49, 3981–3987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirwan, C.; O’Keefe, M. Paediatric aphakic glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 2006, 84, 734–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, D.S.C.; Fan, D.S.P.; Ng, J.S.K.; Yu, C.B.O.; Wong, C.Y.; Cheung, A.Y.K. Ocular hypertensive and anti-inflammatory responses to different dosages of topical dexamethasone in children: A randomized trial. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2005, 33, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenerty, C.; Grigg, J.; Freedman, S. Glaucoma Following Cataract Surgery. In Childhood Glaucoma: The 9th Consensus Report of the World Glaucoma Association; Kugler Publications: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mataftsi, A.; Haidich, A.-B.; Kokkali, S.; Rabiah, P.K.; Birch, E.; Stager, D.R.; Cheong-Leen, R.; Singh, V.; Egbert, J.E.; Astle, W.F.; et al. Postoperative Glaucoma Following Infantile Cataract Surgery: An individual patient data meta-analysis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014, 132, 1059–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, S.F.; Lynn, M.J.; Beck, A.D.; Bothun, E.D.; Örge, F.H.; Lambert, S.R. Glaucoma-Related Adverse Events in the First 5 Years After Unilateral Cataract Removal in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015, 133, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solebo, A.; Cumberland, P.; Rahi, J.S. 5-year outcomes after primary intraocular lens implantation in children aged 2 years or younger with congenital or infantile cataract: Findings from the IoLunder2 prospective inception cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosunmu, E.; Freedman, S. Aphakic/pseudophakic glaucoma. In Practical Management of Pediatric Ocular Disorders and Strabismus: A Case-Based Approach; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 459–470. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philips, B. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine–Levels of Evidence; Centre for Evidence Based Medicine: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Baris, M.; Biler, E.D.; Yilmaz, S.G.; Ates, H.; Uretmen, O.; Kose, S. Treatment results in aphakic patients with glaucoma following congenital cataract surgery. Int. Ophthalmol. 2017, 39, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhola, R.; Keech, R.V.; Olson, R.; Petersen, D.B. Long-Term Outcome of Pediatric Aphakic Glaucoma. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2006, 10, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comer, R.M.; Kim, P.; Cline, R.; Lyons, C.J. Cataract surgery in the first year of life: Aphakic glaucoma and visual outcomes. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2011, 46, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiess, K.; Calvo, J.P. Clinical Characteristics and Treatment of Secondary Glaucoma After Pediatric Congenital Cataract Surgery in a Tertiary Referral Hospital in Spain. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2020, 57, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, C.L.; Trivedi, R.H.; Wilson, M.E. Intraocular pressure control with echothiophate iodide in children’s eyes with glaucoma after cataract extraction. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2015, 19, 116–118.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bothun, E.D.; Guo, Y.; Christiansen, S.P.; Summers, C.G.; Anderson, J.S.; Wright, M.M.; Kramarevsky, N.Y.; Lawrence, M.G. Outcome of angle surgery in children with aphakic glaucoma. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2010, 14, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.D.; Lynn, M.J.; Crandall, J.; Mobin-Uddin, O. Surgical outcomes with 360-degree suture trabeculotomy in poor-prognosis primary congenital glaucoma and glaucoma associated with congenital anomalies or cataract surgery. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2011, 15, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dao, J.B.; Sarkisian, S.R.; Freedman, S.F. Illuminated Microcatheter–facilitated 360-Degree Trabeculotomy for Refractory Aphakic and Juvenile Open-angle Glaucoma. J. Glaucoma 2014, 23, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sayed, Y.M.; Elhusseiny, A.M.; Gawdat, G.I.; Elhilali, H.M. One-year results of two-site trabeculotomy in paediatric glaucoma following cataract surgery. Eye 2020, 35, 1637–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.E.; Dao, J.B.; Freedman, S.F. 360-Degree Trabeculotomy for Medically Refractory Glaucoma Following Cataract Surgery and Juvenile Open-Angle Glaucoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 175, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, C.; Bohnsack, B.L. Rate of Complete Catheterization of Schlemm’s Canal and Trabeculotomy Success in Primary and Secondary Childhood Glaucomas. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 212, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuara-Blanco, A.; Wilson, R.P.; Spaeth, G.L.; Schmidt, C.M.; Augsburger, J.J. Filtration procedures supplemented with mitomycin C in the management of childhood glaucoma. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1999, 83, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.D.; Wilson, W.R.; Lynch, M.G.; Lynn, M.J.; Noe, R. Trabeculectomy with adjunctive mitomycin C in pediatric glaucoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1998, 126, 648–657. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9822228 (accessed on 1 June 2019). [CrossRef]

- Freedman, S.F.; Mccormick, K.; Cox, T.A. Mitomycin C-augumented trabeculectomy with Postoperative Wound Modulation in Pediatric Glaucoma. J. Am. Assoc. Ped. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 1999, 3, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.K.; Bagga, H.; Nutheti, R.; Gothwal, V.K.; Nanda, A.K. Trabeculectomy with or without mitomycin-C for paediatric glaucoma in aphakia and pseudophakia following congenital cataract surgery. Eye 2003, 17, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakravan, M.; Homayoon, N.; Shahin, Y.; Reza, B.R.A. Trabeculectomy With Mitomycin C Versus Ahmed Glaucoma Implant With Mitomycin C for Treatment of Pediatric Aphakic Glaucoma. J. Glaucoma 2007, 16, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, D.K.; Plager, D.A.; Snyder, S.K.; Raiesdana, A.; Helveston, E.M.; Ellis, F.D. Surgical results of secondary glaucomas in childhood. Ophthalmology 1998, 105, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balekudaru, S.; Vadalkar, J.; George, R.; Vijaya, L. The use of Ahmed glaucoma valve in the management of pediatric glaucoma. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2014, 18, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banitt, M.R.; Sidoti, P.A.; Gentile, R.C.; Tello, C.; Liebmann, J.M.; Rodriguez, N.; Dhar, S. Pars Plana Baerveldt Implantation for Refractory Childhood Glaucomas. J. Glaucoma 2009, 18, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.C.; Bhatia, L.S.; Walton, D.S. Ahmed valve surgery for refractory pediatric glaucoma: A report of 52 eyes. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2005, 42, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donahue, S.P.; Keech, R.V.; Munden, P.; Scott, W.E. Baerveldt implant surgery in the treatment of advanced childhood glaucoma. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 1997, 1, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshatory, Y.M.; Gauger, E.H.; Kwon, Y.; Alward, W.L.M.; Boldt, H.C.; Russell, S.; Mahajan, V. Management of Pediatric Aphakic Glaucoma With Vitrectomy and Tube Shunts. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2016, 53, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englert, J.A.; Freedman, S.; Cox, T.A. The Ahmed Valve in refractory pediatric glaucoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1999, 127, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwan, C.; O’Keefe, M.; Lanigan, B.; Mahmood, U. Ahmed valve drainage implant surgery in the management of paediatric aphakic glaucoma. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2005, 89, 855–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, R.P.; Reynolds, A.; Emond, M.J.; Barlow, W.E.; Leen, M.M. Long-term Survival of Molteno Glaucoma Drainage Devices. Ophthalmology 1996, 103, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Malley Schotthoefer, E.; Yanovitch, T.L.; Freedman, S.F. Aqueous drainage device surgery in refractory pediatric glaucomas: I. Long-term outcomes. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2008, 12, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakravan, M.; Esfandiari, H.; Yazdani, S.; Doozandeh, A.; Dastborhan, Z.; Gerami, E.; Kheiri, B.; Pakravan, P.; Yaseri, M.; Hassanpour, K. Clinical outcomes of Ahmed glaucoma valve implantation in pediatric glaucoma. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 29, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotsos, T.; Tsioga, A.; Andreanos, K.; Diagourtas, A.; Petrou, P.; Georgalas, I.; Papaconstantinou, D. Managing high risk glaucoma with the Ahmed valve implant: 20 years of experience. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 11, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiess, K.; Calvo, J.P. Outcomes of Ahmed glaucoma valve in paediatric glaucoma following congenital cataract surgery in persistent foetal vasculature. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 31, 1070–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, O.; Segal, A.; Melamud, A.; Wolf, A. Clinical Outcomes After Ahmed Glaucoma Valve Implantation for Pediatric Glaucoma After Congenital Cataract Surgery. J. Glaucoma 2020, 30, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.D.; Freedman, S.; Kammer, J.; Jin, J. Aqueous shunt devices compared with trabeculectomy with Mitomycin-C for children in the first two years of life. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2003, 136, 994–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autrata, R.; Lokaj, M. Trans-scleral diode laser cyclophotocoagulation in children with refractory glaucoma. Long-term outcomes. Scripta Med. Fac. Med. Univ. Brun. Masaryk. 2003, 76, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Cantor, A.J.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Neely, D.E.; Plager, D.A. Long-term efficacy of endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation in the management of glaucoma following cataract surgery in children. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2018, 22, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, B.C.; Plager, D.A.; Neely, D.E.; Sprunger, D.T.; Sondhi, N.; Roberts, G.J. Endoscopic diode laser cyclophotocoagulation in the management of aphakic and pseudophakic glaucoma in children. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2006, 11, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, T.S.; Mulvihill, M.S.; Freedman, S.F. Endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation (ECP) for childhood glaucoma: A large single-center cohort experience. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2019, 23, 84.e1–84.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirwan, J.F.; Shah, P.; Khaw, P.T. Diode laser cyclophotocoagulation: Role in the management of refractory pediatric glaucomas. Ophthalmology 2002, 109, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, D.E.; Plager, D.A. Endocyclophotocoagulation for management of difficult pediatric glaucomas. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2001, 5, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlote, T.; Grüb, M.; Kynigopoulos, M. Long-term results after transscleral diode laser cyclophotocoagulation in refractory posttraumatic glaucoma and glaucoma in aphakia. Glaucoma 2007, 246, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirabayashi, M.T.; Lee, D.; King, J.T.; Thomsen, S.; An, J.A. Comparison of Surgical Outcomes of 360° Circumferential Trabeculotomy Versus Sectoral Excisional Goniotomy with the Kahook Dual Blade At 6 Months. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2019, 13, 2017–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, D.; Rickford, K.; Sakkari, S. Case report: Cataract extraction/lensectomy, excisional goniotomy and transscleral cyclophotocoagulation: Affordable combination MIGS for plateau iris glaucoma. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, D.; Nkrumah, G.; Ng, C. Combination microinvasive glaucoma surgery: 23-gauge cystotome goniotomy and intra-scleral ciliary sulcus suprachoroidal microtube surgery in refractory and severe glaucoma: A case series. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 68, 2557–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, D.; Okaka, Y.; Ng, C. A Novel Low Cost Effective Technique in Using a 23 Gauge Straight Cystotome to Perform Goniotomy: Making Micro-invasive Glaucoma Surgery (MIGS) Accessible to the Africans and the Diaspora. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2019, 111, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanito, M.; Sano, I.; Ikeda, Y.; Fujihara, E. Short-term results of microhook ab interno trabeculotomy, a novel minimally invasive glaucoma surgery in Japanese eyes: Initial case series. Acta Ophthalmol. 2017, 95, e354–e360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanito, M. Microhook ab interno trabeculotomy, a novel minimally invasive glaucoma surgery. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2018, 12, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.P.; Palmberg, P.F. Needling Revision of Glaucoma Drainage Device Filtering Blebs. Ophthalmology 1997, 104, 1004–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, W.; Lesk, M.R. Surgical Outcome of Replacing a Failed Ahmed Glaucoma Valve by a Baerveldt Glaucoma Implant in the Same Quadrant in Refractory Glaucoma. J. Glaucoma 2018, 27, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, A.; Tello, C.; Sidoti, P.A.; Ritch, R.; Liebmann, J.M. Sequential Glaucoma Implants in Refractory Glaucoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2010, 149, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, M.C.; Adams, G.G.W.; Dahlmann-Noor, A. Medical Management of Children with Congenital/Infantile Cataract Associated with Microphthalmia, Microcornea, or Persistent Fetal Vasculature. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2019, 56, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).