Comparison of Interview to Questionnaire for Assessment of Eating Disorders after Bariatric Surgery

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Description of Interview and Questionnaire

2.3. Study Protocol

2.4. Data Analyses

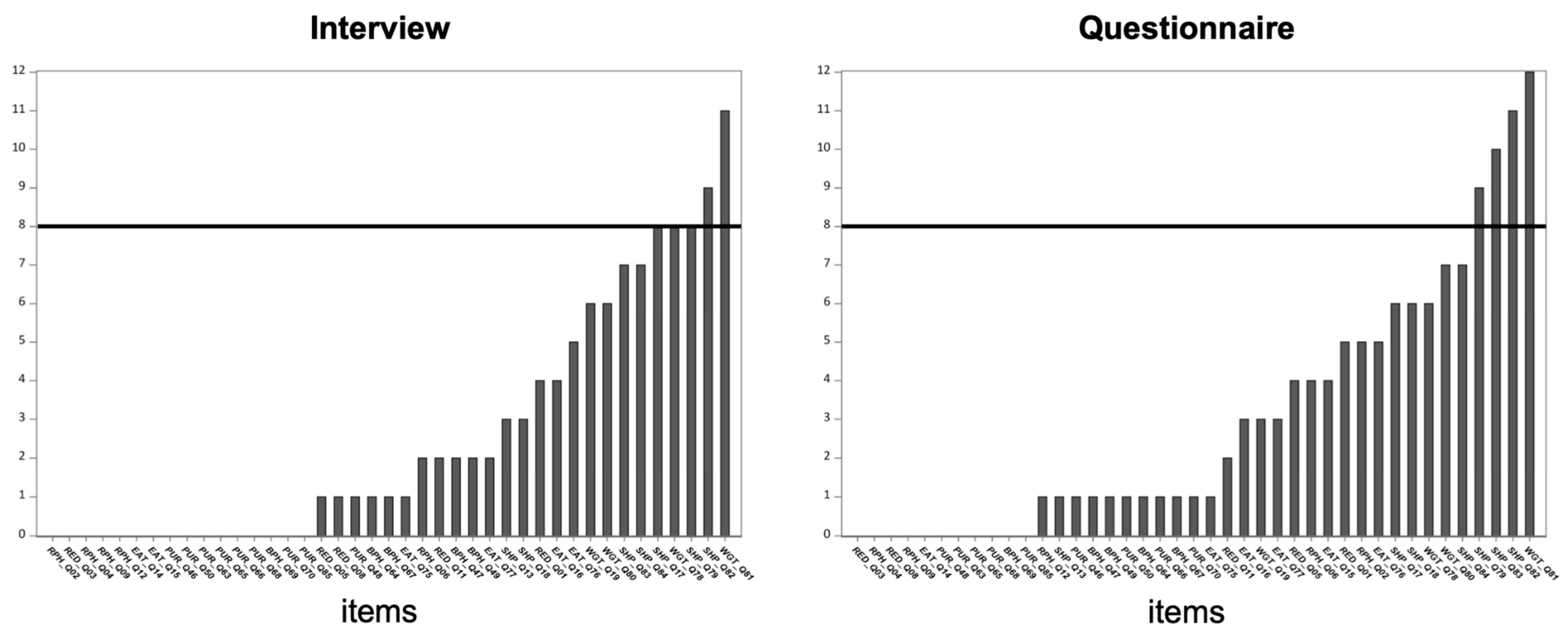

2.4.1. Examination of the Distributions of All Items in the Interview and Questionnaire

2.4.2. Analysis Overview

2.4.3. Binomial Tests

2.4.4. Chi-Square Analysis

2.4.5. Spearman Rank-Order Correlations

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Distributions and Frequency of Response to Items in the Questionnaire and Interview

3.3. Binomial Tests

3.3.1. Tests of Agreement

3.3.2. Tests on Discordant Pairs (0,1 and 1,0)

3.4. Tests of Association

3.4.1. Chi-Squared Tests

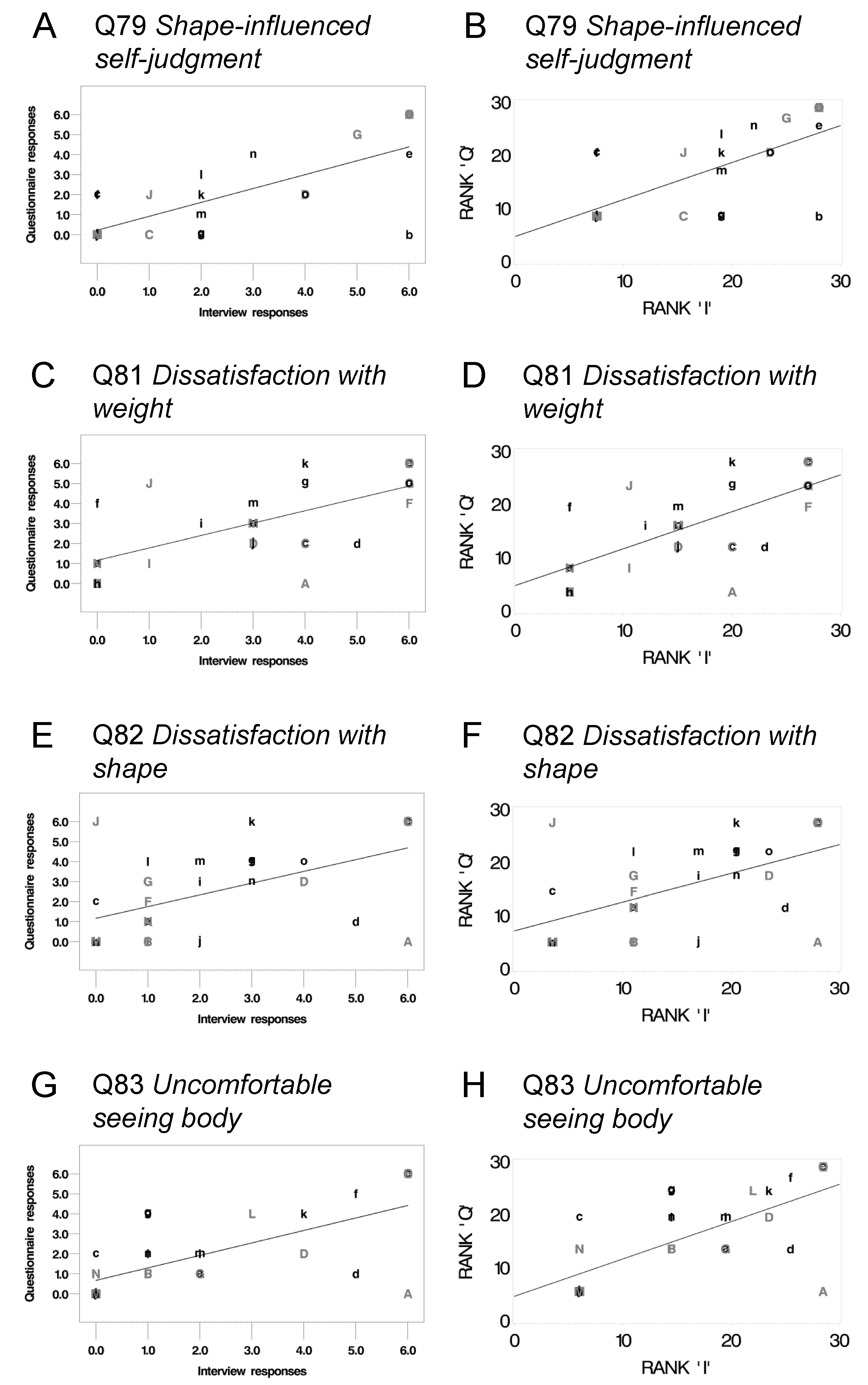

3.4.2. Spearman Rank Order Correlations on Ordinal Items

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Category | Item Number | Prompt |

|---|---|---|

| Shape concern | Q13 | On how many days have you had a definite desire to have a totally flat stomach? |

| Shape concern | Q15 | Has thinking about shape or weight made it very difficult to concentrate on things you are interested in (for example, working, following a conversation, or reading)? |

| Shape concern | Q17 | Have you had a definite fear that you might gain weight? |

| Shape concern | Q18 | Have you felt fat? |

| Shape concern | Q79 | Has your shape influenced how you think about (judge) yourself as a person? |

| Shape concern | Q82 | How dissatisfied have you been with your shape? |

| Shape concern | Q83 | How uncomfortable have you felt seeing your body (for example, seeing your shape in the mirror, in a shop window reflection, while undressing, or taking a bath or shower)? |

| Shape concern | Q84 | How uncomfortable have you felt about others seeing your shape or figure (for example, in communal changing rooms, when swimming, or wearing tight clothes)? |

| Weight concern | Q15 | Has thinking about shape or weight made it very difficult to concentrate on things you are interested in (for example, working, following a conversation, or reading)? |

| Weight concern | Q19 | Have you had a strong desire to lose weight? |

| Weight concern | Q78 | Has your weight influenced how you think about (judge) yourself as a person? |

| Weight concern | Q80 | How much would it have upset you if you had been asked to weigh yourself once a week for the next four weeks? |

| Weight concern | Q81 | How dissatisfied have you been with your weight? |

| Eating concern | Q14 | Has thinking about food, eating, or calories made it very difficult to concentrate on things you are interested in (for example, working, following a conversation, or reading)? |

| Eating concern | Q16 | On how many days have you strongly feared that you would lose control over eating? |

| Eating concern | Q75 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), on how many days have you eaten in secret (i.e., furtively)? [Do not count episodes of binge eating] |

| Eating concern | Q76 | On what proportion of the times that you have eaten have you felt guilty (felt that you’ve done wrong) because of its effect on your shape or weight? [Do not count episodes of binge eating] |

| Eating concern | Q77 | How concerned have you been about other people seeing you eat? [Do not count episodes of binge eating] |

| Restraint for weight control | Q01 | On how many days have you deliberately tried to limit the amount of food you ate, regardless of whether or not you were successful, for any of the following reasons? (a) To lose weight or avoid gaining weight |

| Restraint for weight control | Q03 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), on how many days have you gone for long periods of time (8 waking hours or more) without eating anything at all for any of the following reasons? (a) To lose weight or avoid gaining weight |

| Restraint for weight control | Q05 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), on how many days have you tried to exclude from your diet any foods that you like, regardless of whether or not you were successful, for any of the following reasons? (a) To lose weight or avoid gaining weight |

| Restraint for weight control | Q08 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), on how many days have you tried to follow definite rules regarding your eating (for example, a calorie limit), regardless of whether or not you were successful, for any of the following reasons? (a) To lose weight or avoid gaining weight |

| Restraint for weight control | Q11 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), on how many days have you had a definite desire to have an empty stomach for any of the following reasons? (a) To lose weight or avoid gaining weight b) To avoid physical discomfort |

| Restraint for physical discomfort | Q02 | On how many days have you deliberately tried to limit the amount of food you ate, regardless of whether or not you were successful, for any of the following reasons? (b) To avoid physical discomfort |

| Restraint for physical discomfort | Q04 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), on how many days have you gone for long periods of time (8 waking hours or more) without eating anything at all for any of the following reasons? (b) To avoid physical discomfort |

| Restraint for physical discomfort | Q06 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), on how many days have you tried to exclude from your diet any foods that you like, regardless of whether or not you were successful, for any of the following reasons? (b) To avoid physical discomfort |

| Restraint for physical discomfort | Q09 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), on how many days have you tried to follow definite rules regarding your eating (for example, a calorie limit), regardless of whether or not you were successful, for any of the following reasons? (b) To avoid physical discomfort |

| Restraint for physical discomfort | Q12 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), on how many days have you had a definite desire to have an empty stomach for any of the following reasons? (b) To avoid physical discomfort |

| Purging to avoid physical discomfort | Q47 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), on how many days have you made yourself vomit for any of the following reasons? (b) To avoid physical discomfort |

| Purging to avoid physical discomfort | Q49 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), on how many days have you purposely chewed food and spit it out without swallowing it, for any of the following reasons? (b) To avoid physical discomfort |

| Purging to avoid physical discomfort | Q64 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), on how many days have you ruminated food; that is, on purpose, brought food back up again into your mouth and chewed and swallowed it again, for any of the following reasons? (b) To avoid physical discomfort |

| Purging to avoid physical discomfort | Q67 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), on how many days have you taken laxatives in larger than recommended amounts (including on product labeling) for any of the following reasons? (b) To avoid physical discomfort |

| Purging to avoid physical discomfort | Q69 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), on how many days have you taken diuretics (water pills) in larger than recommended amounts (including recommendations on product labeling), for any of the following reasons? (b) To avoid physical discomfort |

| Purging for weight control | Q46 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), on how many days have you made yourself vomit for any of the following reasons? (a) To lose weight or avoid gaining weight |

| Purging for weight control | Q48 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), on how many days have you purposely chewed food and spit it out without swallowing it, for any of the following reasons? (a) To lose weight or avoid gaining weight |

| Purging for weight control | Q50 | If you have purposely chewed food and spit it out without swallowing it, how distressed or upset have you usually been about this behavior? |

| Purging for weight control | Q63 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), on how many days have you ruminated food; that is, on purpose, brought food back up again into your mouth and chewed and swallowed it again, for any of the following reasons? (a) To lose weight or avoid gaining weight |

| Purging for weight control | Q65 | If you have ruminated food in the past four weeks, how distressed or upset have you usually been about this behavior? |

| Purging for weight control | Q66 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), on how many days have you taken laxatives in larger than recommended amounts (including on product labeling) for any of the following reasons? (a) To lose weight or avoid gaining weight |

| Purging for weight control | Q68 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), on how many days have you taken diuretics (water pills) in larger than recommended amounts (including recommendations on product labeling), for any of the following reasons? (a) To lose weight or avoid gaining weight |

| Purging for weight control | Q70 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), on how many days have you exercised in a “driven” or “compulsive” way as a means of controlling your weight, shape, or amount of fat or to burn off calories? |

| Purging for weight control | Q85 | If you have ever made yourself vomit in the last four weeks, how distressed or upset have you usually been about the vomiting? |

| Q20 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), have there been any days when you felt that you have eaten too much (given your current circumstances), even if others might not agree? Please indicate the number of days it occurred and average number of times per day. If this did not occur, enter 0 for both fields. Please enter a number only, with no spaces or text. DAYS | |

| Q22 | Over the past 28 days, have there been days when you have eaten what other people would regard as an unusually large amount of food (given your current circumstances)? Please indicate the number of days it occurred and average number of times per day, on days when it occurred. If this did not occur, enter 0 for both fields. Please enter a number only, with no spaces or text. DAYS | |

| Q26 | Of the times that you picked, nibbled, or grazed in the past 4 weeks (28 days), how often was it for any of the following reasons? To lose weight or avoid gaining weight | |

| Q28 | Please indicate any additional reasons for having picked, nibbled, or grazed in the past 4 weeks (28 days): Sadness, loneliness, anxiety, stress, body image dissatisfaction, or boredom | |

| Q29 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), did you have a feeling of loss of control when you picked, nibbled or grazed on food between meals and snacks? Please indicate the number of days this occurred and average number of times per day, on days when it occurred. If this did not occur, enter 0 for both fields. Please enter a number only, with no spaces or text. DAYS | |

| Q31 | During times that you felt a loss of control over your eating, how often have you experienced any of the following? (a) Eat much more quickly than usual | |

| Q32 | During times that you felt a loss of control over your eating, how often have you experienced any of the following? (b) Eat until you feel uncomfortably full | |

| Q33 | During times that you felt a loss of control over your eating, how often have you experienced any of the following? (c) Eat large amounts when you do not feel physically hungry | |

| Q34 | During times that you felt a loss of control over your eating, how often have you experienced any of the following? (d) Eat alone because you feel embarrassed about how much you are eating | |

| Q35 | During times that you felt a loss of control over your eating, how often have you experienced any of the following? (e) Feel disgusted with yourself, depressed, or very guilty | |

| Q36 | During times that you felt a loss of control over your eating, how often have you experienced any of the following? f. Felt upset or distressed by your eating | |

| Q07 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), on how many days have you tried to exclude from your diet any foods that you like, regardless of whether or not you were successful, for any of the following reasons? (c) To adhere to recommendations made by a dietitian or other health care professional | |

| Q10 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), on how many days have you tried to follow definite rules regarding your eating (for example, a calorie limit), regardless of whether or not you were successful, for any of the following reasons? (c) To adhere to recommendations made by a dietitian or other health care professional | |

| Q21 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), have there been any days when you felt that you have eaten too much (given your current circumstances), even if others might not agree? Please indicate the number of days it occurred and average number of times per day. If this did not occur, enter 0 for both fields. Please enter a number only, with no spaces or text. Times per day | |

| Q23 | Over the past 28 days, have there been days when you have eaten what other people would regard as an unusually large amount of food (given your current circumstances)? Please indicate the number of days it occurred and average number of times per day, on days when it occurred. If this did not occur, enter 0 for both fields. Please enter a number only, with no spaces or text. Times per day | |

| Q24 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), have you picked, nibbled or grazed on food between meals and snacks? Please indicate the number of days it occurred and average number of times per day, on days when it occurred. If this did not occur, enter 0 for both fields. Please enter a number only, with no spaces or text. DAYS | |

| Q25 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), have you picked, nibbled or grazed on food between meals and snacks? Please indicate the number of days it occurred and average number of times per day, on days when it occurred. If this did not occur, enter 0 for both fields. Please enter a number only, with no spaces or text. Times per day | |

| Q27 | Of the times that you picked, nibbled, or grazed in the past 4 weeks (28 days), how often was it for any of the following reasons? (b) To avoid physical discomfort | |

| Q30 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), did you have a feeling of loss of control when you picked, nibbled or grazed on food between meals and snacks? Please indicate the number of days this occurred and average number of times per day, on days when it occurred. If this did not occur, enter 0 for both fields. Please enter a number only, with no spaces or text. Times per day | |

| Q37 | Of the times when you picked, nibbled, or grazed on food AND had a feeling of loss of control, how often did you eat any of the following foods? (a) Ice cream, Jell-O, smoothies, and/or other soft foods or beverages | |

| Q38 | Of the times when you picked, nibbled, or grazed on food AND had a feeling of loss of control, how often did you eat any of the following foods? (b) Crackers, cookies, donuts, and/or other baked snacks | |

| Q39 | Of the times when you picked, nibbled, or grazed on food AND had a feeling of loss of control, how often did you eat any of the following foods? (c) Meat and/or cheeses | |

| Q40 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), what time of the day were you most likely to have experienced loss of control while nibbling or grazing on food between meals and snacks? Select “None of the time” if you did not experience loss of control. (a) Morning | |

| Q41 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), what time of the day were you most likely to have experienced loss of control while nibbling or grazing on food between meals and snacks? Select “None of the time” if you did not experience loss of control. (b) Around noon | |

| Q42 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), what time of the day were you most likely to have experienced loss of control while nibbling or grazing on food between meals and snacks? Select “None of the time” if you did not experience loss of control. (c) Afternoon | |

| Q43 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), what time of the day were you most likely to have experienced loss of control while nibbling or grazing on food between meals and snacks? Select “None of the time” if you did not experience loss of control. (d) Evening | |

| Q44 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), what time of the day were you most likely to have experienced loss of control while nibbling or grazing on food between meals and snacks? Select “None of the time” if you did not experience loss of control. (e) During the night | |

| Q45 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), what time of the day were you most likely to have experienced loss of control while nibbling or grazing on food between meals and snacks? Select “None of the time” if you did not experience loss of control. (f) After having slept | |

| Q51 | Of the times that you purposely chewed food and spit it out without swallowing it, how often have you done this with each of the foods below? Meat | |

| Q52 | Of the times that you purposely chewed food and spit it out without swallowing it, how often have you done this with each of the foods below? Bread | |

| Q53 | Of the times that you purposely chewed food and spit it out without swallowing it, how often have you done this with each of the foods below? Pasta | |

| Q54 | Of the times that you purposely chewed food and spit it out without swallowing it, how often have you done this with each of the foods below? Raw vegetables | |

| Q55 | Of the times that you purposely chewed food and spit it out without swallowing it, how often have you done this with each of the foods below? Rice | |

| Q56 | Of the times that you purposely chewed food and spit it out without swallowing it, how often have you done this with each of the foods below? Sweets/Candy | |

| Q57 | Of the times that you purposely chewed food and spit it out without swallowing it, how often have you done this with each of the foods below? Ice cream | |

| Q58 | Of the times that you purposely chewed food and spit it out without swallowing it, how often have you done this with each of the foods below? Other dairy | |

| Q59 | Of the times that you purposely chewed food and spit it out without swallowing it, how often have you done this with each of the foods below? Syrup | |

| Q60 | Of the times that you purposely chewed food and spit it out without swallowing it, how often have you done this with each of the foods below? Cakes/bars/cookies | |

| Q61 | Of the times that you purposely chewed food and spit it out without swallowing it, how often have you done this with each of the foods below? Fried foods | |

| Q62 | Of the times that you purposely chewed food and spit it out without swallowing it, how often have you done this with each of the foods below? Other (specify below) | |

| Q71 | Over the past 28 days, on how many days have you skipped regular meals for any of the following reasons? (a) To lose weight or avoid gaining weight | |

| Q72 | Over the past 28 days, on how many days have you skipped regular meals for any of the following reasons? (b) To avoid physical discomfort | |

| Q73 | Over the past 28 days, on how many days have you skipped regular meals for any of the following reasons? (c) You felt full or weren’t hungry | |

| Q74 | Over the past 28 days, on how many days have you skipped regular meals for any of the following reasons? (d) I was grazing or nibbling | |

| Q86 | Over the past four weeks (28 days), on average, how long have your episodes of loss of control while nibbling or grazing been (in minutes)? For example, enter 25 for 25 min, or 60 for an hour. Please enter a number only, with no spaces or text. | |

| Q87 | What has been the longest duration of an episode of losing control while picking, nibbling, or grazing (in minutes)? Please enter a number only, with no spaces or text. | |

| Q88 | What has been the shortest duration of an episode of losing control while picking, nibbling, or grazing (in minutes)? Please enter a number only, with no spaces or text. | |

| Q89 | What was your weight in pounds prior to surgery? Please enter a number only, with no spaces or text. | |

| Q90 | What is your current weight in pounds? Please enter a number only, with no spaces or text. | |

| Q91 | What is your current height? Please enter a number only, with no spaces or text. |

References

- Opolski, M.; Chur-Hansen, A.; Wittert, G. The eating-related behaviours, disorders and expectations of candidates for bariatric surgery. Clin. Obes. 2015, 5, 165–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Zwaan, M.; Mitchell, J.E.; Swan-Kremeier, L.; McGregor, T.; Howell, M.L.; Roerig, J.L.; Crosby, R.D. A comparison of different methods of assessing the features of eating disorders in post-gastric bypass patients: A pilot study. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2004, 12, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busetto, L.; Segato, G.; De Luca, M.; De Marchi, F.; Foletto, M.; Vianello, M.; Valeri, M.; Favretti, F.; Enzi, G. Weight loss and postoperative complications in morbidly obese patients with binge eating disorder treated by laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Obes. Surg. 2005, 15, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colles, S.L.; Dixon, J.B.; O’Brien, P.E. Grazing and loss of control related to eating: Two high-risk factors following bariatric surgery. Obesity 2008, 16, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, E.M.; Mitchell, J.E.; Engel, S.G.; Machado, P.P.P.; Lancaster, K.; Wonderlich, S.A. What is “grazing”? Reviewing its definition, frequency, clinical characteristics, and impact on bariatric surgery outcomes, and proposing a standardized definition. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2014, 10, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Z.; Fairburn, C. The eating disorder examination: A semi-structured interview for the assessment of the specific psychopathology of eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1987, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Zwaan, M.; Hilbert, A.; Swan-Kremeier, L.; Simonich, H.; Lancaster, K.; Howell, L.M.; Monson, T.; Crosby, R.D.; Mitchell, J.E. Comprehensive interview assessment of eating behavior 18-35 months after gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2010, 6, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Beglin, S.J. Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1994, 16, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfein, J.A.; Devlin, M.J.; Kamenetz, C. Eating disorder examination-questionnaire with and without instruction to assess binge eating in patients with binge eating disorder. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2005, 37, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilo, C.M.; Masheb, R.M.; Wilson, G.T. A comparison of different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2001, 69, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binford, R.B.; Le Grange, D.; Jellar, C.C. Eating Disorders Examination versus Eating Disorders Examination- Questionnaire in adolescents with full and partial-syndrome bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2005, 37, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalarchian, M.A.; Terence Wilson, G.; Brolin, R.E.; Bradley, L. Assessment of eating disorders in bariatric surgery candidates: Self-report questionnaire versus interview. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2000, 28, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilfley, D.E.; Schwartz, M.B.; Spurrell, E.B.; Fairburn, C.G. Assessing the specific psychopathology of binge eating disorder patients: Interview or self-report? Behav. Res. Ther. 1997, 35, 1151–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mond, J.M.; Hay, P.J.; Rodgers, B.; Owen, C.; Beumont, P.J.V. Validity of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) in screening for eating disorders in community samples. Behav. Res. Ther. 2004, 42, 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolk, S.L.; Loeb, K.L.; Walsh, B.T. Assessment of patients with anorexia nervosa: Interview versus self-report. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2005, 37, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sysko, R.; Walsh, B.T.; Fairburn, C.G. Eating disorder examination-questionnaire as a measure of change in patients with bulimia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2005, 37, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, J.C.; Aime, A.A.; Mills, J.S. Assessment of bulimia nervosa: A comparison of interview and self-report questionnaire methods. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2000, 30, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, R.D.; Masheb, R.M.; White, M.A.; Grilo, C.M. Comparison of Methods for Identifying and Assessing Obese Patients with Binge Eating Disorder in Primary Care Settings. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2011, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams-Kerver, G.A.; Steffen, K.J.; Mitchell, J.E. Eating Pathology After Bariatric Surgery: An Updated Review of the Recent Literature. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliday, T.A.; Sundqvist, J.; Hultin, M.; Walldén, J. Post-operative nausea and vomiting in bariatric surgery patients: An observational study. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2017, 61, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalarchian, M.A.; King, W.C.; Devlin, M.J.; White, G.E.; Marcus, M.D.; Garcia, L.; Yanovski, S.Z.; Mitchell, J.E. Surgery-related gastrointestinal symptoms in a prospective study of bariatric surgery patients: 3-year follow-up. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2017, 13, 1562–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conceição, E.; Orcutt, M.; Mitchell, J.; Engel, S.; Lahaise, K.; Jorgensen, M.; Woodbury, K.; Hass, N.; Garcia, L.; Wonderlich, S. Eating disorders after bariatric surgery: A case series. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2013, 46, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Interview | Questionnaire | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Item | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Shape concern | 13. Days desiring flat stomach | 13 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 16 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Shape concern | 15. Difficulty concentrating due to shape or weight concern | 24 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 24 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Shape concern | 17. Fear of weight gain | 4 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 11 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 14 |

| Shape concern | 18. Feeling fat | 18 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 14 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Shape concern | 79. Shape influenced self-judgement | 14 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 16 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Shape concern | 82. Dissatisfaction with shape | 6 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 6 |

| Shape concern | 83. Uncomfortable seeing body | 11 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| Shape concern | 84. Uncomfortable having others see body | 14 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 13 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Weight concern | 15. Difficulty concentrating due to shape or weight concern | 24 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 24 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Weight concern | 19. Strong weight loss desire | 8 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 15 |

| Weight concern | 78. Weight influenced self-judgement | 12 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 15 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Weight concern | 80. Upset if asked to weigh self once/wk for 4 wk | 9 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 13 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Weight concern | 81. Dissatisfaction with weight | 9 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Eating concern | 14. Difficulty concentrating due to food intake | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Eating concern | 16. Days fearing out of control eating | 13 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 11 |

| Eating concern | 75. Days eaten in secret | 26 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Eating concern | 76. Proportion of times felt guilty | 14 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 12 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Eating concern | 77. Concern over other people seeing you eat | 27 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Restraint for weight control | 1. Days limiting food to avoid weight gain | 20 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 18 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Restraint for weight control | 3. Days w/o eating to avoid weight gain | 29 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Restraint for weight control | 5. Days excluded liked foods to avoid weight gain | 21 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 18 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Restraint for weight control | 8. Follow diet rules to avoid weight gain | 20 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 13 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 9 |

| Restraint for weight control | 11. Days desiring empty stomach to avoid weight gain | 23 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 21 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Restraint to avoid physical discomfort | 2. Days limiting food to avoid physical discomfort | 20 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 16 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| Restraint to avoid physical discomfort | 4. Days w/o eating to avoid physical discomfort | 29 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Restraint to avoid physical discomfort | 6. Days excluded liked foods to avoid physical discomfort | 19 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 19 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Restraint to avoid physical discomfort | 9. Follow diet rules to avoid physical discomfort | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 18 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Restraint to avoid physical discomfort | 12. Days desiring empty stomach to avoid physical discomfort | 23 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 22 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Purging for weight control | 46. Vomit to lose weight or avoid weight gain | 29 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Purging for weight control | 48. Chewed food/spit wo swallow to lose weight/avoid weight gain | 28 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Purging for weight control | 50. Upset after chewing food or spit out w/o swallow | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Purging for weight control | 63. Days ruminated food to lose weight or avoid gaining weight | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Purging for weight control | 65. Upset when ruminated food | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Purging for weight control | 66. Take laxatives to lose weight or avoid gaining weight | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Purging for weight control | 68. Take diuretics to lose weight or avoid gaining weight | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Purging for weight control | 70. Driven or compulsive exercise to lose weight | 29 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Purging for weight control | 85. Vomited in last 4 wks, how upset about it | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Purging to avoid physical discomfort | 47. Vomit to avoid physical discomfort | 25 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Purging to avoid physical discomfort | 49. Chewed food/spit w/o swallow to avoid physical discomfort | 25 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Purging to avoid physical discomfort | 64. Days ruminated food to avoid physical discomfort | 27 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Purging to avoid physical discomfort | 67. Take laxatives to avoid physical discomfort | 27 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Purging to avoid physical discomfort | 69. Take diuretics to avoid physical discomfort | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Category d | Item | 0,0 | 0,1 | 1,0 | 1,1 | Concordant a (%) | Binomial b Con p | Binomial c Dis p | χ2 | χ2 p | C | κ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shape concern | 13. Days desiring flat stomach | 13 (43%) | 3 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 14 (47%) | 90% | <0.0001 | 0.08 | 20.07 | <0.0001 | 0.63 | 0.80 |

| Shape concern | 15. Diff conc due to shape or wt concern | 23 (77%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 5 (17%) | 94% | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 18.80 | <0.0001 | 0.62 | 0.79 |

| Shape concern | 17. Fear of wt gain | 3 (10%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 25 (83%) | 93% | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 15.19 | <0.0001 | 0.58 | 0.71 |

| Shape concern | 18. Feeling fat | 14 (47%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (13%) | 12 (40%) | 87% | <0.0001 | 0.05 | 17.50 | <0.0001 | 0.61 | 0.74 |

| Shape concern | 79. Shape influenced self-judgement | 12 (40%) | 4 (13%) | 2 (7%) | 12 (40%) | 80% | 0.001 | 0.41 | 11.06 | 0.001 | 0.52 | 0.60 |

| Shape concern | 82. Dissat with shape | 4 (13%) | 5 (17%) | 2 (7%) | 19 (63%) | 76% | 0.004 | 0.26 | 4.80 | 0.028 | 0.37 | 0.39 |

| Shape concern | 83. Uncomf seeing body | 9 (30%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (7%) | 18 (60%) | 90% | <0.0001 | 0.56 | 18.37 | <0.0001 | 0.62 | 0.78 |

| Shape concern | 84. Uncomf having others see body | 10 (33%) | 3 (10%) | 4 (13%) | 13 (43%) | 76% | 0.004 | 0.71 | 8.44 | 0.004 | 0.47 | 0.53 |

| Weight concern | 15. Diff conc due to shape or wt concern | 23 (77%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 5 (17%) | 94% | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 18.80 | <0.0001 | 0.62 | 0.79 |

| Weight concern | 19. Strong wt loss desire | 6 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (7%) | 22 (73%) | 93% | <0.0001 | 0.16 | 20.63 | <0.0001 | 0.64 | 0.81 |

| Weight concern | 78. wt influenced self-judgement | 10 (33%) | 5 (17%) | 2 (7%) | 13 (43%) | 76% | 0.004 | 0.26 | 8.89 | 0.003 | 0.48 | 0.53 |

| Weight concern | 80. Upset to weigh self once/ | 7 (23%) | 6 (20%) | 2 (7%) | 15 (50%) | 73% | 0.011 | 0.16 | 6.21 | 0.013 | 0.41 | 0.44 |

| Weight concern | 81. Dissat with wt | 5 (17%) | 1 (3%) | 4 (13%) | 20 (67%) | 83% | <0.001 | 0.18 | 10.16 | 0.001 | 0.50 | 0.56 |

| Eating concern | 14. Diff conc due to food intake | 30 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 100% | <0.0001 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Eating concern | 16. Days fearing OOC eating | 10 (33%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (10%) | 17 (57%) | 90% | <0.0001 | 0.08 | 19.62 | <0.0001 | 0.63 | 0.79 |

| Eating concern | 75. Days eaten in secret | 24 (80%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (7%) | 3 (10%) | 90% | <0.0001 | 0.56 | 11.31 | <0.001 | 0.52 | 0.61 |

| Eating concern | 76. Proportion of times felt guilty | 9 (30%) | 3 (10%) | 5 (17%) | 13 (43%) | 73% | 0.011 | 0.48 | 6.45 | 0.011 | 0.42 | 0.46 |

| Eating concern | 77. Concern—other people seeing you e | 25 (83%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (7%) | 3 (10%) | 93% | <0.0001 | 0.16 | 17.00 | <0.0001 | 0.60 | 0.71 |

| Restr wt control | 1. Days limiting food to avoid wt gain | 15 (50%) | 3 (10%) | 5 (17%) | 7 (23%) | 73% | 0.011 | 0.48 | 5.63 | 0.018 | 0.40 | 0.43 |

| Restr wt control | 3. Days w/o eating to avoid wt gain | 27 (90%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (7%) | 1 (3%) | 93% | <0.0001 | 0.16 | 9.31 | 0.002 | 0.49 | 0.47 |

| Restr wt control | 5. Days excl liked foods to avoid gain | 14 (47%) | 4 (13%) | 7 (23%) | 5 (17%) | 63% | 0.144 | 0.37 | 1.30 | 0.250 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| Restr wt control | 8. Follow diet rules to avoid wt gain | 12 (40%) | 1 (3%) | 8 (27%) | 9 (30%) | 70% | 0.029 | 0.02 | 6.79 | 0.009 | 0.43 | 0.43 |

| Restr wt control | 11. Days empty stomach to avoid gain | 21 (70%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (7%) | 7 (23%) | 93% | <0.0001 | 0.16 | 21.30 | <0.0001 | 0.64 | 0.83 |

| Restr discomfort | 2. Days limiting food avoid discomf | 15 (50%) | 1 (3%) | 5 (17%) | 9 (30%) | 80% | 0.001 | 0.10 | 11.32 | <0.001 | 0.52 | 0.59 |

| Restr discomfort | 4. Days w/o eating to avoid discomf | 27 (90%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 90% | <0.0001 | 0.56 | 0.07 | 0.786 | 0.05 | -0.05 |

| Restr discomfort | 6. Days excl lik foods avoid discomf | 15 (50%) | 4 (13%) | 4 (13%) | 7 (23%) | 73% | 0.011 | 1.00 | 5.44 | 0.020 | 0.39 | 0.43 |

| Restr discomfort | 9. Follow diet rules to avoid discomf | 17 (57%) | 1 (3%) | 7 (23%) | 5 (17%) | 73% | 0.011 | 0.03 | 5.87 | 0.015 | 0.40 | 0.39 |

| Restr discomfort | 12. Days empty stom avoid discomf | 22 (73%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 7 (23%) | 97% | <0.0001 | 0.37 | 25.11 | <0.0001 | 0.66 | 0.91 |

| Purge wt control | 46. Vomit to lose wt or avoid wt gain | 29 (97%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 100% | <0.0001 | NA | 30.00 | <0.0001 | 0.71 | 1.00 |

| Purge wt control | 48. Chewed food/spit wo swallow | 28 (93%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 97% | <0.0001 | 0.32 | 14.48 | 0.0001 | 0.57 | 0.65 |

| Purge wt control | 50. Upset after chewing food or spit out | 29 (97%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 97% | <0.0001 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Purge wt control | 63. Days ruminated food to lose wt | 30 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 100% | <0.0001 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Purge wt control | 65. Upset when ruminated food | 29 (97%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 97% | <0.0001 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Purge wt control | 66. Take laxatives to lose/avoid gaining | 29 (97%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 97% | <0.0001 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Purge wt control | 68. Take diuretics to lose/avoid gaining | 30 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 100% | <0.0001 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Purge wt control | 70. Driven exercise to lose wt | 26 (87%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (10%) | 1(3%) | 90% | <0.0001 | 0.08 | 6.72 | 0.010 | 0.43 | 0.36 |

| Purge wt control | 85. Vomited in last 4 wks, upset about | 30 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 100% | <0.0001 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Purge avoi discomf | 47. Vomit to avoid phys discomf | 25 (83%) | 2 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (10%) | 93% | <0.0001 | 0.16 | 17.00 | <0.0001 | 0.60 | 0.71 |

| Purge avoi discomf | 49. Chewed /spit avoid phys discomf | 25 (83%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 4(13%) | 96% | <0.0001 | 0.32 | 23.08 | <0.0001 | 0.66 | 0.87 |

| Purge avoi discomf | 64. Days ruminated food | 27 (90%) | 2 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 93% | <0.0001 | 0.16 | 9.31 | 0.002 | 0.49 | 0.47 |

| Purge avoi discomf | 67. Take laxatives avoid phys discomf | 27 (90%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (10%) | 100% | <0.0001 | NA | 30.00 | <0.0001 | 0.71 | 1.00 |

| Purge avoi discomf | 69. Take diuretics avoid phys discomf | 30 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 100% | <0.0001 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Globus, I.; Kissileff, H.R.; Hamm, J.D.; Herzog, M.; Mitchell, J.E.; Latzer, Y. Comparison of Interview to Questionnaire for Assessment of Eating Disorders after Bariatric Surgery. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10061174

Globus I, Kissileff HR, Hamm JD, Herzog M, Mitchell JE, Latzer Y. Comparison of Interview to Questionnaire for Assessment of Eating Disorders after Bariatric Surgery. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(6):1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10061174

Chicago/Turabian StyleGlobus, Inbal, Harry R. Kissileff, Jeon D. Hamm, Musya Herzog, James E. Mitchell, and Yael Latzer. 2021. "Comparison of Interview to Questionnaire for Assessment of Eating Disorders after Bariatric Surgery" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 6: 1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10061174

APA StyleGlobus, I., Kissileff, H. R., Hamm, J. D., Herzog, M., Mitchell, J. E., & Latzer, Y. (2021). Comparison of Interview to Questionnaire for Assessment of Eating Disorders after Bariatric Surgery. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(6), 1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10061174