Abstract

Thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) is a rare and potentially life-threatening condition that can be caused by a heterogeneous group of diseases, often affecting the brain and kidneys. TMAs should be classified according to etiology to indicate targets for treatment. Complement dysregulation is an important cause of TMA that defines cases not related to coexisting conditions, that is, primary atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS). Ever since the approval of therapeutic complement inhibition, the approach of TMA has focused on the recognition of primary atypical HUS. Recent advances, however, demonstrated the pivotal role of complement dysregulation in specific subtypes of patients considered to have secondary atypical HUS. This is particularly the case in patients presenting with coexisting hypertensive emergency, pregnancy, and kidney transplantation, shifting the paradigm of disease. In contrast, complement dysregulation is uncommon in patients with other coexisting conditions, such as bacterial infection, drug use, cancer, and autoimmunity, among other disorders. In this review, we performed a critical appraisal on complement dysregulation and the use of therapeutic complement inhibition in TMAs associated with coexisting conditions and outline a pragmatic approach to diagnosis and treatment. For future studies, we advocate the term complement-mediated TMA as opposed to the traditional atypical HUS-type classification.

1. Integrated Discussion

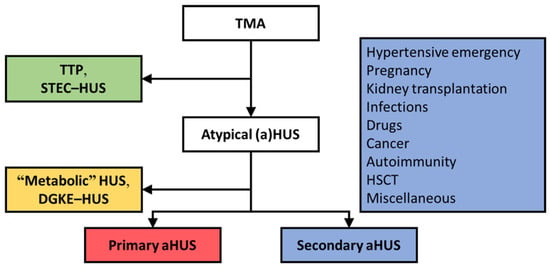

Thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) is a rare, potentially life-threatening condition that reflects tissue responses to severe endothelial damage caused by distinct disorders, including thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS). Despite heterogeneity, TMAs typically manifest with consumptive thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, and ischemic organ damage, often affecting the brain and kidneys. TMAs should be classified according to etiology to indicate targets for treatment (Figure 1) [1,2]. For example, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura is caused by a severe deficiency of von Willebrand cleaving protease (also known as a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, member 13 (ADAMTS13)) [3], and thus treatment should restore ADAMTS13’s function. The term HUS, either atypical or not, has been used to define any TMA with a normal functional activity of ADAMTS13.

Figure 1.

The atypical HUS-type classification [1,2].

HUS occurring on the background of complement dysregulation defines primary atypical HUS, indicating a diagnosis of exclusion [1]. Many of such patients present with rare variants in complement genes and/or autoantibodies that inhibit complement regulatory proteins [4,5]. Primary atypical HUS is considered an orphan disease, with an incidence of <1 per million population per year [6]. Most patients with HUS (i.e., ~90%) present with coexisting conditions, assumed to be the etiologic factor of disease, and have been termed secondary atypical HUS (Figure 1) [7]. Known coexisting conditions linked to secondary atypical HUS are hypertensive emergency, pregnancy, kidney transplantation, bacterial infections, drug use, cancer, autoimmunity, and hematologic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), among others. Recent advances, however, linked complement dysregulation to specific subtypes of so-called secondary atypical HUS and poor kidney outcomes [8,9,10]. Thus, the traditional atypical HUS-type classification is not absolute because complement dysregulation can be present along the spectrum of HUS [11]. In the era of therapeutic complement inhibition [12,13,14], the challenge is to recognize patients with complement dysregulation in the earliest possible stage to prevent end-stage kidney disease (ESKD).

In this review, we performed a critical appraisal on complement dysregulation and therapeutic complement inhibition in HUS presenting with coexisting conditions and outline a pragmatic approach to diagnosis and treatment. We advocate to use the term complement-mediated (C-)TMA to define cases related to complement dysregulation.

Secondary atypical HUS represents the majority of TMAs, that is, ~90%; Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC)-HUS, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), and primary atypical HUS are responsible for 6%, 3%, and 3% of TMAs [7]. DGKE, diacylglycerol kinase epsilon. HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

2. Primary Atypical HUS, a Prototypic C-TMA

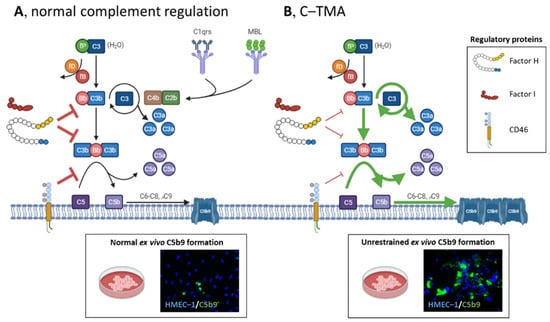

The complement system is an ancient and conserved effector system involved in the defense against pathogens and host homeostasis, which can be activated via the classic, lectin, and alternative pathways (Figure 2A). The alternative pathway is continuously active through a mechanism known as the thick-over, i.e., spontaneous hydrolysis of C3. Host cells, including the endothelium, are protected from the harmful effects of complement activation by regulatory proteins.

Figure 2.

Schematic overview of complement activation and regulation in health and disease. (A) The complement system can be initiated via the classical (C1qrs), lectin (MBL), and alternative pathways (C3), converging to C3. The alternative pathway is a spontaneously and continuously active surveillance system operating in the circulation and on the cell surface. C3 (H2O) binds factor B (fB) and factor D (fD), and the latter cleaves fB into Bb, the serine esterase that cleaves C3 into C3a and C3b. C3’s thioester domain located in C3b can bind to the cell surface (e.g., microbes), providing a platform to form the C3 convertase of the alternative pathway (i.e., C3Bb) to cleave more C3, activating an amplification loop. Next, additional C3b can shift the C3 convertase to a C5 convertase, cleaving C5 into C5a and C5b, activating the terminal complement pathway. C5a and, to a lesser extent, C3a attract leukocytes to the site of complement activation. C5b can bind C6, C7, C8, and various C9 molecules to form the lytic C5b9 (i.e., membrane attack complex) on cells. Host cells, including the endothelium, are protected from the harmful effects of complement activation by factor I, factor H, and CD46 (also known as membrane cofactor protein); these proteins have decay-accelerating and cofactor activities, leading to factor I-mediated cleavage of C3b into inactivated proteins. (Normal ex vivo C5b9 formation on perturbed human microvascular endothelial cells of dermal origin (HMEC–1) indicates normal complement regulation.). (B) In C-TMA, rare variants in complement genes (i.e., loss of function of factor I, factor H, or CD46 (thin red lines); gain of function of C3 or CFB (green lines)) and/or autoantibodies targeting complement regulatory proteins result in unrestrained complement activation, formation of C5b9 on the endothelium, and a procoagulant environment that triggers thrombosis. (Massive ex vivo C5b9 formation on perturbed HMEC–1 indicates unrestrained C5 activation.) fP, properdin.

In the late 1980s, complement dysregulation (i.e., factor H deficiency) was found in two brothers with (primary atypical) HUS [15]. Thereafter, a linkage study in three families identified a variant in CFH [16] located in the C’-terminal-reduced factor H’s binding to the endothelium [17]. At present, >600 variants in complement genes have been identified in primary atypical HUS [18], with a prevalence of >50% [4,5]. Rare variants (i.e., minor allele frequency of <0.1%) [19] in CFH, CFI, CD46, C3, and CFB are of particular interest [18]. CFH, CFI, and CD46 variants lead to impaired protein synthesis or function, whereas C3 and CFB variants cause a gain-of-function protein, predisposing to unrestrained complement activation on the endothelium (Figure 2B). Recombination between CFH and the CFH-related genes CFHR1-5 can form a hybrid gene linked to complement dysregulation, whereas single variants in CFHR genes require functional studies to determine their relevance [18]. The homozygous deletion of CFHR1 and CFHR3 has been associated with autoantibodies that prevent factor H’s binding to the endothelium [20,21]. The presence of such defects per se is insufficient to cause TMA [22], although combined variants increase the penetrance of disease [23]. Thus, additional precipitants, such as coexisting conditions, are needed for TMA to manifest.

In vivo studies, using factor H knockout mice [24] or mice homozygous for a gain-of-function change in C3 [25], linked C5 activation to microvascular thrombosis. C5 activation on the endothelium leads to the expression and secretion of tissue factor via the insertion of sublytic C5b9 [26] and the interaction of C5a with its receptor [27]. Induction of tissue factor, activation of the extrinsic pathway of coagulation, and assembly of the prothrombinase complex cause fibrin thrombi to form. Of note, thrombin [28] and plasmin [29], upon activation of the fibrinolytic pathway, may accelerate C5 activation. In addition, C5 products cause the release of Weibel–Palade bodies, containing von Willebrand factor, from the endothelium [30], platelets, and leukocytes. This may provide another platform for thrombosis [31], but significant accumulation of von Willebrand factor multimers, as seen in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, does not occur [32].

The introduction of eculizumab, an anti-C5 monoclonal antibody, improved 1-year kidney survival from 44% [5] to 90% [14]. Patients who start treatment early have the best possible chance to recover kidney function [13]. Kidney function further improved during extended treatment [12,13]. Ever since eculizumab’s success, several complement-specific drugs have reached late-stage clinical development for the treatment of primary atypical HUS.

Altogether, these experimental and clinical observations confirmed the role of complement in primary atypical HUS and changed the paradigm of disease.

3. Patients with TMA and Coexisting Conditions May Present with Complement Dysregulation

Recent studies demonstrated that complement dysregulation is prevalent in specific subtypes of “secondary” atypical HUS and linked to poor kidney outcomes, resembling primary atypical HUS (hereafter referred to as C-TMA) [33].

3.1. Hypertensive Emergency

Hypertensive emergency has been linked to activation of the renin–angiotensin system [34]. Renin can cause the C3 convertase to form via activation of C3 [35]. In vivo data showed that downstream activation of C5 may play a role in the development of hypertension-associated kidney disease [36,37].

Kidney disease is common (i.e., ~25%) in patients with hypertensive emergency and has been associated with hemolysis [38]. Patients with kidney disease are at risk for ESKD despite blood pressure control [39]. Many of such patients have been classified as “hypertensive” ESKD with no confirmative proof on kidney biopsy, assuming that the kidneys are the victim rather than culprit of disease. Thus, parenchymal kidney disease, including TMA, can be missed. This is particularly the case in patients without profound hematologic abnormalities [8]. We, for the first time, demonstrated the high prevalence of pathogenic variants in complement genes in patients with TMA and coexisting hypertensive emergency, which was associated with ESKD and TMA recurrence [40]. Our observations have been validated in independent cohorts, confirming C-TMA associated with complement gene variants in ~50% of patients with hypertensive emergency and severe kidney disease [41,42]. It remains unknown whether or not complement dysregulation plays a role in patients with mild-to-moderate kidney disease.

The effect of blood pressure control, the cornerstone of treatment, is limited in patients with hypertensive emergency and severe kidney disease [39]. The high prevalence of rare variants in complement genes and/or massive ex vivo C5b9 formation on the endothelium pointed to complement as a potential target for treatment [43]. Retrospective studies from France [41], Spain/Portugal [42], and our own group [8] included 29 patients with hypertensive emergency and severe kidney disease, including patients on dialysis, who had been treated with eculizumab (Table 1). At 12 months, a renal response was achieved in 21 (72%) patients, suggesting a benefit of treatment as compared to historical data [39]. Future prospective trials are warranted to test the hypothesis that therapeutic complement inhibition will improve the outcome of patients presenting with severe kidney disease. Furthermore, the predictive role of functional ex vivo complement measures [8] and pathologic features, such as chronic vascular and tubulointerstitial damage [44], should be addressed.

3.2. Pregnancy

TMA can develop in 1 per 25,000 births [45], the etiology of which varies from thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura [46] to pregnancy-associated atypical HUS in late pregnancy and the postpartum period [47]. In an international cohort, pregnancy-associated atypical HUS resembled C-TMA based on the high incidence of ESKD and prevalence of complement gene variants, that is, 41% to 56% [9,48]. Pregnancy, indeed, has been linked to the first episode of primary atypical HUS in ~20% of women [47]. Rare variants in complement genes per se, however, cannot predict the risk of pregnancy-associated atypical HUS in a given pregnancy [49]. Pregnancy-associated atypical HUS often develops in the setting of coexisting conditions, such as preeclampsia and bleeding [49,50].

Preeclampsia and HELLP, both microangiopathies of late pregnancy, have been linked to complement activation but not to complement dysregulation. Variants in complement genes were found in up to 18% (n/N = 7/40) [51] and 38% (n/N = 9/24) [52,53], respectively. Most variants, however, should be classified as uncertain or no significance according to current standards and guidelines [54]. Patients typically present with mild kidney disease and are at low risk for ESKD [7]. Moreover, preeclampsia and HELLP can develop in pregnant women treated with eculizumab [55], suggesting a mechanism not related to C5 activation. Preeclampsia or HELLP, however, may mask pregnancy-associated atypical HUS when the kidney function does not improve after delivery.

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes advocated that patients with pregnancy-associated atypical HUS should be treated as C-TMA (Table 1) [2].

Table 1.

The effects of therapeutic complement inhibition in patients with TMA and coexisting hypertensive emergency or pregnancy. Single case reports have not been included.

Table 1.

The effects of therapeutic complement inhibition in patients with TMA and coexisting hypertensive emergency or pregnancy. Single case reports have not been included.

| Presentation | Genotyping | Outcome at 12 Months | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eculizumab, n/N | Creatinine, mg/dL | Dialysis (%) | Rare Variants (%) | Pathogenic (%) | Renal Response (%) | ESKD (%) | Death (%) | ESKD in Untreated Patients | |

| Hypertensive emergency | |||||||||

| Combined data | 29/122 | Unknown | Unknown | 14 (48) | Unknown | 21 (72) | 7 (24) | 1 (3) | |

| Cavero et al. [42] | 9/19 | 8 (IQR, 7–9) | 8 (89) | 5 (56) | 3 (33) | 7 (78) | 2 (22) | 0 | 60% at 1 year (N = 10) |

| El Karoui et al. [41] | 13/76 | Unknown | Unknown | 7 (54) | Unknown | 9 (69) | 4 (31) | 0 | 64% at 1 year (N = 61) |

| Timmermans et al. [8] | 7/26 | 7 (IQR, 4–9) | 4 (57) | 2 (29) | 2 (29) | 5 (71) | 1 (14) | 1 (14) | 75% at 1 year (N = 16) a |

| Pregnancy-associated atypical HUS | |||||||||

| Combined data | 17/116 | Unknown | Unknown | 7 (41) | Unknown | 15 (88) | 2 (25) | 0 | |

| Bruel et al. [9] | 4/87 | Unknown | Unknown | 2 (50) | Unknown | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | 0 | 49% at last follow-up (N = 71) |

| Huerta et al. [48] | 10/22 | 4 (IQR, 3–5) | 3 (30) | 4 (40) | 4 (40) | 10 (100) | 0 | 0 | 55% at last follow-up (N = 11) |

| Timmermans et al. [49] | 3/7 | 5 (IQR, 4–6) | 3 (100) | 1 (33) | 0 | 2 (67) | 1 (33) | 0 | 50% at last follow-up (N = 4) |

a Patients with follow-up <12 months were excluded. HUS, hemolytic uremic syndrome. ESKD, end-stage kidney disease. IQR, inter quartile range.

3.3. Kidney Transplantation

Activation of complement has been linked to various stages of kidney transplantation, including, but not limited to, organ preservation, reperfusion during surgery, and rejection [56].

TMA after kidney transplantation, both de novo and recurrent disease, has been linked to rare variants in complement genes in 29% (n/N = 7/24) [10] and 68% (n/N = 39/57) [57], respectively. The risk of TMA after kidney transplantation is >36 times higher in patients with C-TMA in the native kidney as compared to those with ESKD due to other causes [58] and is associated with the genetic fingerprint [57]. Of note, “hypertensive” ESKD was diagnosed prior to kidney donation in three recipients with de novo TMA who carried rare variants in complement genes (pathogenic, n/N = 2/3) [10]. Thus, C-TMA may be missed in the native kidneys, particularly in patients with a history of “hypertensive” ESKD [59], as discussed earlier. Most cases of de novo TMA in transplant recipients, however, are related to concurrent medications (e.g., calcineurin inhibition) [60] or antibody-mediated rejection [61]. The clinical course of both conditions is not consistent with complement dysregulation as 1-year graft survival was common [62,63]. The precise prevalence of rare variants in complement genes, however, has not been studied.

No data are available on eculizumab for the treatment of de novo TMA in transplant recipients, but eculizumab’s efficacy has been proven for C-TMA recurrence [64]. The graft’s capacity to recover is limited as compared to the native kidneys [65], favoring preemptive treatment in selected cases. Prophylaxis prevented C-TMA recurrence and improved graft survival in patients at moderate and high risk but should not be used in patients with a variant in CD46 alone because the donor kidney does not express mutated CD46. TMA related to antibody-mediated rejection, characterized by C4d deposits in peritubular capillaries and donor-specific alloantibodies, often fails to respond to eculizumab [63]. C4d deposits reflect activation via the classical pathway, and therefore C1 inhibition upstream of C5 may be a better target for treatment.

5. Proposal for a Pragmatic Approach to Diagnosis of TMA

With the current state of knowledge and availability of therapeutic complement inhibition, either eculizumab or other therapies under investigation, the central consideration in the management of patients with TMA is the recognition of C-TMA and, thus, patients who would likely benefit from such therapies.

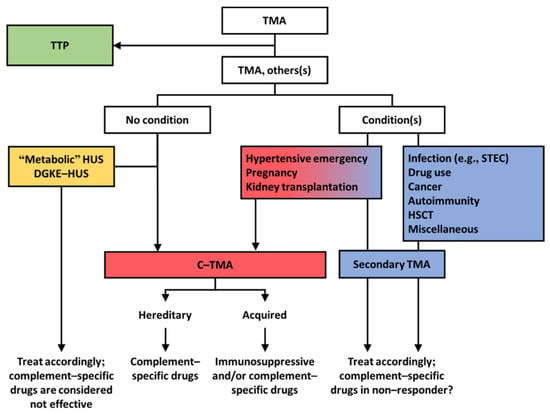

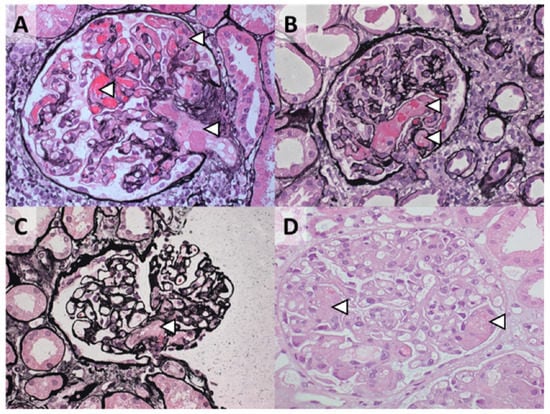

We propose that TMAs presenting with a normal enzymatic activity of ADAMTS13 should be classified according to etiology (Figure 3). Profound systemic hemolysis can be absent [116], and therefore a tissue (e.g., kidney) biopsy may be needed to detect TMA. Morphologic features, however, cannot define etiology (Figure 4) [8]. Patients should be screened for coexisting conditions and, if absent, complement dysregulation. Patients with coexisting conditions and a severe clinical phenotype, that is, severe kidney disease not responding to the standard of care and/or TMA recurrence, should also be screened for complement dysregulation. Many patients with coexisting hypertensive emergency, pregnancy, and, to a lesser extent, de novo TMA after kidney transplantation fulfill these criteria and have C-TMA rather than secondary disease [11]. In contrast, C-TMA is uncommon in patients with bacterial infection, drug-induced TMA, cancer, autoimmunity, HSCT-TMA, and miscellaneous conditions, indicating secondary TMA; rapid improvement in kidney function should be expected in such cases (Table 2). TMA related to metabolic disorders (e.g., cobalamin C deficiency) or loss of DGKE is common in children and, in particular, infants. The term idiopathic should be used judiciously because the etiology can be found in almost every patient [7].

Figure 3.

Pragmatic approach to diagnosis and treatment of TMA. Patients should be tested for the enzymatic activity of ADAMTS13 (i.e., >10% excludes thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)). Patients with a normal activity of ADAMTS13 should be screened for coexisting conditions. DGKE, diacylglycerol kinase epsilon. HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. HUS, hemolytic uremic syndrome. STEC, Shiga toxin–producing E. coli.

Figure 4.

Morphologic features of TMA on kidney biopsy cannot define etiology. Representative cases of TMA presenting with coexisting hypertensive emergency: (A) 28-year-old woman with a gain-of-function C3 protein (p.R161W); (B) 47-year-old man with no rare variants in complement genes identified, after surgery; (C) 37-year-old woman with no rare variants in complement genes identified, and coexisting pregnancy; (D) 28-year-old woman with no rare variants in complement genes identified. The arrowheads indicate glomerular thrombosis, often accompanied by mesangiolysis. Jones methenamine silver (A–C) and hematoxylin and eosin (D) staining; original magnification, ×400.

Of note, patients with coexisting hypertensive emergency, pregnancy, or de novo TMA after kidney transplantation may have C–TMA rather than secondary TMA. This, in particular, is the case in patients with severe kidney disease not responding to the standard of care and/or those with relapsing disease. Most patients with no coexisting conditions have C–TMA, although TMA related to recessive variants in DGKE and metabolic causes should be considered in children.

Tests recommended to screen for complement dysregulation include routine complement measures, genotyping, and autoantibody testing. Routine complement measures, however, are not specific and lack sensitivity [43,117]. Genetics should include sequencing of CFH, CFI, CD46, CFB, and C3, and multiplex ligation probe amplification to detect hybrid genes and/or the loss of CFHR1 and CFHR3. Factor H serum reactivity should be assessed, particularly in children and patients with a homozygous deletion of CFHR1 and CFHR3 [20]. Hereditary and/or acquired factors inform the long-term prognosis [2] and should be used for classification (Figure 3) and to adopt suitable prophylactic measures [118]. For example, patients with pathogenic complement gene variants or high levels of factor H autoantibodies are at high risk of TMA recurrence and sequelae, contrasting patients with neither hereditary nor acquired factors. Functional assessment of ex vivo complement activation appears a promising method for the detection of unrestrained complement activation on the endothelium and, thus, C-TMA, irrespective of rare variants in complement genes [43,117]. Two functional tests have been developed using either microvascular endothelial cells of dermal origin (i.e., HMEC-1) [43,117] or endothelial hybrid cells that lack membrane-bound CD55 and CD59 (i.e., the modified Ham test) [119]. The HMEC-1 test reflects the dynamics of complement activation on the endothelium (Figure 2), with massive ex vivo C5b9 formation on resting endothelial cells at the time of active but not quiescent disease. The modified Ham test does not differentiate active from quiescent disease and lacks specificity [53]. Prospective studies are needed to test the hypothesis that functional tests can guide treatment decisions [33].

Rapid initiation of therapeutic complement inhibition is warranted in C-TMA, including patients with coexisting conditions. It remains unknown whether or not therapeutic complement inhibition should be used to treat specific subtypes of secondary TMA [77]. The efficacy of ravulizumab, a long-acting monoclonal antibody that blocks C5 activation, for the treatment of secondary TMA is being studied (NCT04743804). The results of this long-awaited randomized controlled trial will aid the debate of therapeutic complement inhibition in secondary TMA.

In conclusion, recent advances have clearly changed the landscape of TMAs. Knowledge on complement dysregulation has enabled breakthroughs in the diagnosis and treatment of C-TMA. The proposed approach will increase diagnosis and prognostic accuracy and thus may optimize the efficacy of treatment.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm10143034/s1. Table S1. Classification of rare variants in CFH, CFI, CD46, CFB, C3, THBD, and CFHR1-5 found in patients with secondary thrombotic microangiopathy.

Author Contributions

S.A.M.E.G.T. conducted the literature review and drafter the manuscript. P.v.P. critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This review article received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

S.A.M.E.G.T. and P.v.P. have nothing to disclose.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Loirat, C.; Fakhouri, F.; Ariceta, G.; Besbas, N.; Bitzan, M.; Bjerre, A.; Coppo, R.; Emma, F.; Johnson, S.; Karpman, D.; et al. An international consensus approach to the management of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome in children. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2016, 31, 15–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodship, T.H.; Cook, H.T.; Fakhouri, F.; Fervenza, F.C.; Fremeaux-Bacchi, V.; Kavanagh, D.; Nester, C.M.; Noris, M.; Pickering, M.C.; Rodriguez de Cordoba, S.; et al. Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome and C3 glomerulopathy: Conclusions from a “Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes” (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2017, 91, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furlan, M.; Robles, R.; Galbusera, M.; Remuzzi, G.; Kyrle, P.A.; Brenner, B.; Krause, M.; Scharrer, I.; Aumann, V.; Mittler, U.; et al. Von Willebrand factor-cleaving protease in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and the hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 1578–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noris, M.; Caprioli, J.; Bresin, E.; Mossali, C.; Pianetti, G.; Gamba, S.; Daina, E.; Fenili, C.; Castelletti, F.; Sorosina, A.; et al. Relative role of genetic complement abnormalities in sporadic and familial aHUS and their impact on clinical phenotype. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 5, 1844–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fremeaux-Bacchi, V.; Fakhouri, F.; Garnier, A.; Bienaime, F.; Dragon-Durey, M.A.; Ngo, S.; Moulin, B.; Servais, A.; Provot, F.; Rostaing, L.; et al. Genetics and outcome of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: A nationwide French series comparing children and adults. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 8, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheerin, N.S.; Kavanagh, D.; Goodship, T.H.; Johnson, S. A national specialized service in England for atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome-the first year’s experience. QJM 2016, 109, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, G.; von Tokarski, F.; Thoreau, B.; Bauvois, A.; Barbet, C.; Cloarec, S.; Merieau, E.; Lachot, S.; Garot, D.; Bernard, L.; et al. Etiology and Outcomes of Thrombotic Microangiopathies. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 14, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, S.; Werion, A.; Damoiseaux, J.; Morelle, J.; Reutelingsperger, C.P.; van Paassen, P. Diagnostic and Risk Factors for Complement Defects in Hypertensive Emergency and Thrombotic Microangiopathy. Hypertension 2020, 75, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruel, A.; Kavanagh, D.; Noris, M.; Delmas, Y.; Wong, E.K.S.; Bresin, E.; Provot, F.; Brocklebank, V.; Mele, C.; Remuzzi, G.; et al. Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome in Pregnancy and Postpartum. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 12, 1237–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Quintrec, M.; Lionet, A.; Kamar, N.; Karras, A.; Barbier, S.; Buchler, M.; Fakhouri, F.; Provost, F.; Fridman, W.H.; Thervet, E.; et al. Complement mutation-associated de novo thrombotic microangiopathy following kidney transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 2008, 8, 1694–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, S.; Werion, A.; Morelle, J.; van Paassen, P. Defects in complement and “secondary” hemolytic uremic syndrome. Kidney Int. 2019, 96, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legendre, C.M.; Licht, C.; Muus, P.; Greenbaum, L.A.; Babu, S.; Bedrosian, C.; Bingham, C.; Cohen, D.J.; Delmas, Y.; Douglas, K.; et al. Terminal complement inhibitor eculizumab in atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 2169–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licht, C.; Greenbaum, L.A.; Muus, P.; Babu, S.; Bedrosian, C.L.; Cohen, D.J.; Delmas, Y.; Douglas, K.; Furman, R.R.; Gaber, O.A.; et al. Efficacy and safety of eculizumab in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome from 2-year extensions of phase 2 studies. Kidney Int. 2015, 87, 1061–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhouri, F.; Hourmant, M.; Campistol, J.M.; Cataland, S.R.; Espinosa, M.; Gaber, A.O.; Menne, J.; Minetti, E.E.; Provot, F.; Rondeau, E.; et al. Terminal Complement Inhibitor Eculizumab in Adult Patients with Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome: A Single-Arm, Open-Label Trial. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2016, 68, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.A.; Winterborn, M.H. Hypocomplementaemia due to a genetic deficiency of beta 1H globulin. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1981, 46, 110–119. [Google Scholar]

- Warwicker, P.; Goodship, T.H.; Donne, R.L.; Pirson, Y.; Nicholls, A.; Ward, R.M.; Turnpenny, P.; Goodship, J.A. Genetic studies into inherited and sporadic hemolytic uremic syndrome. Kidney Int. 1998, 53, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, V.P.; Herbert, A.P.; Cortes, C.; McKee, K.A.; Blaum, B.S.; Esswein, S.T.; Uhrin, D.; Barlow, P.N.; Pangburn, M.K.; Kavanagh, D. The binding of factor H to a complex of physiological polyanions and C3b on cells is impaired in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 7009–7018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, A.J.; Breno, M.; Borsa, N.G.; Bu, F.; Fremeaux-Bacchi, V.; Gale, D.P.; van den Heuvel, L.P.; Kavanagh, D.; Noris, M.; Pinto, S.; et al. Statistical Validation of Rare Complement Variants Provides Insights into the Molecular Basis of Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome and C3 Glomerulopathy. J. Immunol. 2018, 200, 2464–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, K.; Borsa, N.G.; Jones, M.B.; Taylor, A.O.; Takanami, E.; Meyer, N.C.; Frees, K.; Thomas, C.P.; et al. Genetic Analysis of 400 Patients Refines Understanding and Implicates a New Gene in Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 29, 2809–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jozsi, M.; Licht, C.; Strobel, S.; Zipfel, S.L.; Richter, H.; Heinen, S.; Zipfel, P.F.; Skerka, C. Factor H autoantibodies in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome correlate with CFHR1/CFHR3 deficiency. Blood 2008, 111, 1512–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jozsi, M.; Strobel, S.; Dahse, H.M.; Liu, W.S.; Hoyer, P.F.; Oppermann, M.; Skerka, C.; Zipfel, P.F. Anti factor H autoantibodies block C-terminal recognition function of factor H in hemolytic uremic syndrome. Blood 2007, 110, 1516–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M.; Erlic, Z.; Hoffmann, M.M.; Arbeiter, K.; Patzer, L.; Budde, K.; Hoppe, B.; Zeier, M.; Lhotta, K.; Rybicki, L.A.; et al. Epidemiological approach to identifying genetic predispositions for atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2010, 74, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bresin, E.; Rurali, E.; Caprioli, J.; Sanchez-Corral, P.; Fremeaux-Bacchi, V.; Rodriguez de Cordoba, S.; Pinto, S.; Goodship, T.H.; Alberti, M.; Ribes, D.; et al. Combined complement gene mutations in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome influence clinical phenotype. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 24, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jorge, E.G.; Macor, P.; Paixao-Cavalcante, D.; Rose, K.L.; Tedesco, F.; Cook, H.T.; Botto, M.; Pickering, M.C. The development of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome depends on complement C5. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 22, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Jackson, K.; Yang, Y.; Denton, H.; Pappworth, I.Y.; Cooke, K.; Barlow, P.N.; Atkinson, J.P.; Liszewski, M.K.; Pickering, M.C.; Kavanagh, D.; et al. Hyperfunctional complement C3 promotes C5-dependent atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 1061–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedesco, F.; Pausa, M.; Nardon, E.; Introna, M.; Mantovani, A.; Dobrina, A. The cytolytically inactive terminal complement complex activates endothelial cells to express adhesion molecules and tissue factor procoagulant activity. J. Exp. Med. 1997, 185, 1619–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, K.; Nagasawa, K.; Horiuchi, T.; Tsuru, T.; Nishizaka, H.; Niho, Y. C5a induces tissue factor activity on endothelial cells. Thromb. Haemost. 1997, 77, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber-Lang, M.; Sarma, J.V.; Zetoune, F.S.; Rittirsch, D.; Neff, T.A.; McGuire, S.R.; Lambris, J.D.; Warner, R.L.; Flierl, M.A.; Hoesel, L.M.; et al. Generation of C5a in the absence of C3: A new complement activation pathway. Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 682–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, J.H.; Walton, B.L.; Aleman, M.M.; O’Byrne, A.M.; Lei, V.; Harrasser, M.; Foley, K.A.; Wolberg, A.S.; Conway, E.M. Complement Activation in Arterial and Venous Thrombosis is Mediated by Plasmin. EBioMedicine 2016, 5, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreman, K.E.; Vaporciyan, A.A.; Bonish, B.K.; Jones, M.L.; Johnson, K.J.; Glovsky, M.M.; Eddy, S.M.; Ward, P.A. C5a-induced expression of P-selectin in endothelial cells. J. Clin. Investig. 1994, 94, 1147–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritis, K.; Doumas, M.; Mastellos, D.; Micheli, A.; Giaglis, S.; Magotti, P.; Rafail, S.; Kartalis, G.; Sideras, P.; Lambris, J.D. A novel C5a receptor-tissue factor cross-talk in neutrophils links innate immunity to coagulation pathways. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 4794–4802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataland, S.R.; Holers, V.M.; Geyer, S.; Yang, S.; Wu, H.M. Biomarkers of terminal complement activation confirm the diagnosis of aHUS and differentiate aHUS from TTP. Blood 2014, 123, 3733–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmermans, S.; Damoiseaux, J.; Werion, A.; Reutelingsperger, C.P.; Morelle, J.; van Paassen, P. Functional and Genetic Landscape of Complement Dysregulation Along the Spectrum of Thrombotic Microangiopathy and its Potential Implications on Clinical Outcomes. Kidney Int. Rep. 2021, 6, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Born, B.J.; Koopmans, R.P.; van Montfrans, G.A. The renin-angiotensin system in malignant hypertension revisited: Plasma renin activity, microangiopathic hemolysis, and renal failure in malignant hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 2007, 20, 900–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekassy, Z.D.; Kristoffersson, A.C.; Rebetz, J.; Tati, R.; Olin, A.I.; Karpman, D. Aliskiren inhibits renin-mediated complement activation. Kidney Int. 2018, 94, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raij, L.; Dalmasso, A.P.; Staley, N.A.; Fish, A.J. Renal injury in DOCA-salt hypertensive C5-sufficient and C5-deficient mice. Kidney Int. 1989, 36, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, S.; Rosendahl, A.; Czesla, D.; Meyer-Schwesinger, C.; Stahl, R.A.; Ehmke, H.; Kurts, C.; Zipfel, P.F.; Kohl, J.; Wenzel, U.O. The complement receptor C5aR1 contributes to renal damage but protects the heart in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2016, 310, F1356–F1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Born, B.J.; Honnebier, U.P.; Koopmans, R.P.; van Montfrans, G.A. Microangiopathic hemolysis and renal failure in malignant hypertension. Hypertension 2005, 45, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, R.; Morales, E.; Segura, J.; Ruilope, L.M.; Praga, M. Long-term renal survival in malignant hypertension. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2010, 25, 3266–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, S.; Abdul-Hamid, M.A.; Vanderlocht, J.; Damoiseaux, J.; Reutelingsperger, C.P.; van Paassen, P.; Limburg Renal, R. Patients with hypertension-associated thrombotic microangiopathy may present with complement abnormalities. Kidney Int. 2017, 91, 1420–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Karoui, K.; Boudhabhay, I.; Petitprez, F.; Vieira-Martins, P.; Fakhouri, F.; Zuber, J.; Aulagnon, F.; Matignon, M.; Rondeau, E.; Mesnard, L.; et al. Impact of hypertensive emergency and complement rare variants on presentation and outcome of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Haematologica 2019, 104, 2501–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavero, T.; Arjona, E.; Soto, K.; Caravaca-Fontan, F.; Rabasco, C.; Bravo, L.; de la Cerda, F.; Martin, N.; Blasco, M.; Avila, A.; et al. Severe and malignant hypertension are common in primary atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Kidney Int. 2019, 96, 995–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmermans, S.; Abdul-Hamid, M.A.; Potjewijd, J.; Theunissen, R.; Damoiseaux, J.; Reutelingsperger, C.P.; van Paassen, P.; Limburg Renal, R. C5b9 Formation on Endothelial Cells Reflects Complement Defects among Patients with Renal Thrombotic Microangiopathy and Severe Hypertension. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 29, 2234–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, S.; van Paassen, P.; Limburg Renal, R. The Authors Reply. Kidney Int. 2017, 92, 267–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashe, J.S.; Ramin, S.M.; Cunningham, F.G. The long-term consequences of thrombotic microangiopathy (thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and hemolytic uremic syndrome) in pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, 91, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moatti-Cohen, M.; Garrec, C.; Wolf, M.; Boisseau, P.; Galicier, L.; Azoulay, E.; Stepanian, A.; Delmas, Y.; Rondeau, E.; Bezieau, S.; et al. Unexpected frequency of Upshaw-Schulman syndrome in pregnancy-onset thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood 2012, 119, 5888–5897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhouri, F.; Roumenina, L.; Provot, F.; Sallee, M.; Caillard, S.; Couzi, L.; Essig, M.; Ribes, D.; Dragon-Durey, M.A.; Bridoux, F.; et al. Pregnancy-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome revisited in the era of complement gene mutations. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 21, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta, A.; Arjona, E.; Portoles, J.; Lopez-Sanchez, P.; Rabasco, C.; Espinosa, M.; Cavero, T.; Blasco, M.; Cao, M.; Manrique, J.; et al. A retrospective study of pregnancy-associated atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Kidney Int. 2018, 93, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmermans, S.; Werion, A.; Spaanderman, M.E.A.; Reutelingsperger, C.P.; Damoiseaux, J.; Morelle, J.; van Paassen, P. The natural course of pregnancies in women with primary atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome and asymptomatic relatives. Br. J. Haematol. 2020, 190, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaggl, M.; Aigner, C.; Csuka, D.; Szilagyi, A.; Prohaszka, Z.; Kain, R.; Haninger, N.; Knechtelsdorfer, M.; Sunder-Plassmann, R.; Sunder-Plassmann, G.; et al. Maternal and Fetal Outcomes of Pregnancies in Women with Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 29, 1020–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmon, J.E.; Heuser, C.; Triebwasser, M.; Liszewski, M.K.; Kavanagh, D.; Roumenina, L.; Branch, D.W.; Goodship, T.; Fremeaux-Bacchi, V.; Atkinson, J.P. Mutations in complement regulatory proteins predispose to preeclampsia: A genetic analysis of the PROMISSE cohort. PLoS Med. 2011, 8, e1001013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhouri, F.; Jablonski, M.; Lepercq, J.; Blouin, J.; Benachi, A.; Hourmant, M.; Pirson, Y.; Durrbach, A.; Grunfeld, J.P.; Knebelmann, B.; et al. Factor H, membrane cofactor protein, and factor I mutations in patients with hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count syndrome. Blood 2008, 112, 4542–4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaught, A.J.; Braunstein, E.M.; Jasem, J.; Yuan, X.; Makhlin, I.; Eloundou, S.; Baines, A.C.; Merrill, S.A.; Chaturvedi, S.; Blakemore, K.; et al. Germline mutations in the alternative pathway of complement predispose to HELLP syndrome. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e99128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servais, A.; Devillard, N.; Fremeaux-Bacchi, V.; Hummel, A.; Salomon, L.; Contin-Bordes, C.; Gomer, H.; Legendre, C.; Delmas, Y. Atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome and pregnancy: Outcome with ongoing eculizumab. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2016, 31, 2122–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jager, N.M.; Poppelaars, F.; Daha, M.R.; Seelen, M.A. Complement in renal transplantation: The road to translation. Mol. Immunol. 2017, 89, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Quintrec, M.; Zuber, J.; Moulin, B.; Kamar, N.; Jablonski, M.; Lionet, A.; Chatelet, V.; Mousson, C.; Mourad, G.; Bridoux, F.; et al. Complement genes strongly predict recurrence and graft outcome in adult renal transplant recipients with atypical hemolytic and uremic syndrome. Am. J. Transplant. 2013, 13, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, J.C.; Agodoa, L.Y.; Yuan, C.M.; Abbott, K.C. Thrombotic microangiopathy after renal transplantation in the United States. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2003, 42, 1058–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, S.; van Paassen, P.; Limburg Renal, R. Mother and Child Reunion in “Hypertensive” End-Stage Renal Disease: Will They Complement Each Other? Nephron 2019, 142, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, R.M.; Van Buren, C.T.; Katz, S.M.; Kahan, B.D. De novo hemolytic uremic syndrome after kidney transplantation in patients treated with cyclosporine-sirolimus combination. Transplantation 2002, 73, 756–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoskar, A.A.; Pelletier, R.; Adams, P.; Nadasdy, G.M.; Brodsky, S.; Pesavento, T.; Henry, M.; Nadasdy, T. De novo thrombotic microangiopathy in renal allograft biopsies-role of antibody-mediated rejection. Am. J. Transplant. 2010, 10, 1804–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarifian, A.; Meleg-Smith, S.; O’Donovan, R.; Tesi, R.J.; Batuman, V. Cyclosporine-associated thrombotic microangiopathy in renal allografts. Kidney Int. 1999, 55, 2457–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, W.H.; Mamode, N.; Montgomery, R.A.; Stegall, M.D.; Ratner, L.E.; Cornell, L.D.; Rowshani, A.T.; Colvin, R.B.; Dain, B.; Boice, J.A.; et al. Safety and efficacy of eculizumab in the prevention of antibody-mediated rejection in living-donor kidney transplant recipients requiring desensitization therapy: A randomized trial. Am. J. Transplant. 2019, 19, 2876–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuber, J.; Le Quintrec, M.; Krid, S.; Bertoye, C.; Gueutin, V.; Lahoche, A.; Heyne, N.; Ardissino, G.; Chatelet, V.; Noel, L.H.; et al. Eculizumab for atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome recurrence in renal transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 2012, 12, 3337–3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siedlecki, A.M.; Isbel, N.; Vande Walle, J.; James Eggleston, J.; Cohen, D.J.; Globala, H.U.S.R. Eculizumab Use for Kidney Transplantation in Patients with a Diagnosis of Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. Kidney Int. Rep. 2019, 4, 434–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Clech, A.; Simon-Tillaux, N.; Provot, F.; Delmas, Y.; Vieira-Martins, P.; Limou, S.; Halimi, J.M.; Le Quintrec, M.; Lebourg, L.; Grange, S.; et al. Atypical and secondary hemolytic uremic syndromes have a distinct presentation and no common genetic risk factors. Kidney Int. 2019, 95, 1443–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fremeaux-Bacchi, V.; Sellier-Leclerc, A.L.; Vieira-Martins, P.; Limou, S.; Kwon, T.; Lahoche, A.; Novo, R.; Llanas, B.; Nobili, F.; Roussey, G.; et al. Complement Gene Variants and Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli-Associated Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome: Retrospective Genetic and Clinical Study. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 14, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlenstiel-Grunow, T.; Hachmeister, S.; Bange, F.C.; Wehling, C.; Kirschfink, M.; Bergmann, C.; Pape, L. Systemic complement activation and complement gene analysis in enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli-associated paediatric haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2016, 31, 1114–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Westra, D.; Volokhina, E.B.; van der Molen, R.G.; van der Velden, T.J.; Jeronimus-Klaasen, A.; Goertz, J.; Gracchi, V.; Dorresteijn, E.M.; Bouts, A.H.; Keijzer-Veen, M.G.; et al. Serological and genetic complement alterations in infection-induced and complement-mediated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2017, 32, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menne, J.; Nitschke, M.; Stingele, R.; Abu-Tair, M.; Beneke, J.; Bramstedt, J.; Bremer, J.P.; Brunkhorst, R.; Busch, V.; Dengler, R.; et al. Validation of treatment strategies for enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O104:H4 induced haemolytic uraemic syndrome: Case-control study. BMJ 2012, 345, e4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, R.K.; Gu, W.; Griffin, P.M.; Jones, T.F.; Rounds, J.; Shiferaw, B.; Tobin-D’Angelo, M.; Smith, G.; Spina, N.; Hurd, S.; et al. Postdiarrheal hemolytic uremic syndrome in United States children: Clinical spectrum and predictors of in-hospital death. J. Pediatr. 2015, 166, 1022–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kielstein, J.T.; Beutel, G.; Fleig, S.; Steinhoff, J.; Meyer, T.N.; Hafer, C.; Kuhlmann, U.; Bramstedt, J.; Panzer, U.; Vischedyk, M.; et al. Best supportive care and therapeutic plasma exchange with or without eculizumab in Shiga-toxin-producing E. coli O104:H4 induced haemolytic-uraemic syndrome: An analysis of the German STEC-HUS registry. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2012, 27, 3807–3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szilagyi, A.; Kiss, N.; Bereczki, C.; Talosi, G.; Racz, K.; Turi, S.; Gyorke, Z.; Simon, E.; Horvath, E.; Kelen, K.; et al. The role of complement in Streptococcus pneumoniae-associated haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2013, 28, 2237–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R.; Hersh, A.L.; Newland, J.; Beekmann, S.E.; Polgreen, P.M.; Bender, J.; Shaw, J.; Copelovitch, L.; Kaplan, B.S.; Shah, S.S.; et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome among children in North America. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2011, 30, 736–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copelovitch, L.; Kaplan, B.S. Streptococcus pneumoniae--associated hemolytic uremic syndrome: Classification and the emergence of serotype 19A. Pediatrics 2010, 125, e174–e182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yui, J.C.; Van Keer, J.; Weiss, B.M.; Waxman, A.J.; Palmer, M.B.; D’Agati, V.D.; Kastritis, E.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Vij, R.; Bansal, D.; et al. Proteasome inhibitor associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Am. J. Hematol. 2016, 91, E348–E352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavero, T.; Rabasco, C.; Lopez, A.; Roman, E.; Avila, A.; Sevillano, A.; Huerta, A.; Rojas-Rivera, J.; Fuentes, C.; Blasco, M.; et al. Eculizumab in secondary atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2017, 32, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzedine, H.; Mangier, M.; Ory, V.; Zhang, S.Y.; Sendeyo, K.; Bouachi, K.; Audard, V.; Pechoux, C.; Soria, J.C.; Massard, C.; et al. Expression patterns of RelA and c-mip are associated with different glomerular diseases following anti-VEGF therapy. Kidney Int. 2014, 85, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, E.E.; Little, D.J.; Vesely, S.K.; George, J.N. Quinine-Induced Thrombotic Microangiopathy: A Report of 19 Patients. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2017, 70, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, K.; Obermeier, H.L. Cancer-related microangiopathic hemolytic anemia: Clinical and laboratory features in 168 reported cases. Medicine 2012, 91, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, S.; Damoiseaux, J.; Reutelingsperger, C.P.; van Paassen, P. More About Complement in the Antiphospholipid Syndrome. Blood 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Vargas, A.; Rosado-Canto, R.; Merayo-Chalico, J.; Arreola-Guerra, J.M.; Mejia-Vilet, J.M.; Correa-Rotter, R.; Gomez-Martin, D.; Alcocer-Varela, J. Renal Thrombotic Microangiopathy in Proliferative Lupus Nephritis: Risk Factors and Clinical Outcomes: A Case-Control Study. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2016, 22, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, S.; Braunstein, E.M.; Yuan, X.; Yu, J.; Alexander, A.; Chen, H.; Gavriilaki, E.; Alluri, R.; Streiff, M.B.; Petri, M.; et al. Complement activity and complement regulatory gene mutations are associated with thrombosis in APS and CAPS. Blood 2020, 135, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.H.; Caselman, N.; Ulmer, S.; Weitz, I.C. Complement-mediated thrombotic microangiopathy associated with lupus nephritis. Blood Adv. 2018, 2, 2090–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glezerman, I.G.; Jhaveri, K.D.; Watson, T.H.; Edwards, A.M.; Papadopoulos, E.B.; Young, J.W.; Flombaum, C.D.; Jakubowski, A.A. Chronic kidney disease, thrombotic microangiopathy, and hypertension following T cell-depleted hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010, 16, 976–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartain, S.; Shubert, S.; Wu, M.F.; Srivaths, P.; Teruya, J.; Krance, R.; Martinez, C. Therapeutic Plasma Exchange does not Improve Renal Function in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation-Associated Thrombotic Microangiopathy: An Institutional Experience. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019, 25, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodele, S.; Davies, S.M.; Lane, A.; Khoury, J.; Dandoy, C.; Goebel, J.; Myers, K.; Grimley, M.; Bleesing, J.; El-Bietar, J.; et al. Diagnostic and risk criteria for HSCT-associated thrombotic microangiopathy: A study in children and young adults. Blood 2014, 124, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodele, S.; Dandoy, C.E.; Lane, A.; Laskin, B.L.; Teusink-Cross, A.; Myers, K.C.; Wallace, G.; Nelson, A.; Bleesing, J.; Chima, R.S.; et al. Complement blockade for TA-TMA: Lessons learned from a large pediatric cohort treated with eculizumab. Blood 2020, 135, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodele, S.; Zhang, K.; Zou, F.; Laskin, B.; Dandoy, C.E.; Myers, K.C.; Lane, A.; Meller, J.; Medvedovic, M.; Chen, J.; et al. The genetic fingerprint of susceptibility for transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Blood 2016, 127, 989–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azukaitis, K.; Simkova, E.; Majid, M.A.; Galiano, M.; Benz, K.; Amann, K.; Bockmeyer, C.; Gajjar, R.; Meyers, K.E.; Cheong, H.I.; et al. The Phenotypic Spectrum of Nephropathies Associated with Mutations in Diacylglycerol Kinase epsilon. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 28, 3066–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez Chinchilla, D.; Pinto, S.; Hoppe, B.; Adragna, M.; Lopez, L.; Justa Roldan, M.L.; Pena, A.; Lopez Trascasa, M.; Sanchez-Corral, P.; Rodriguez de Cordoba, S. Complement mutations in diacylglycerol kinase-epsilon-associated atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 9, 1611–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brocklebank, V.; Kumar, G.; Howie, A.J.; Chandar, J.; Milford, D.V.; Craze, J.; Evans, J.; Finlay, E.; Freundlich, M.; Gale, D.P.; et al. Long-term outcomes and response to treatment in diacylglycerol kinase epsilon nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2020, 97, 1260–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, M.; Fremeaux-Bacchi, V.; Schaefer, F.; Choi, M.; Tang, W.H.; Le Quintrec, M.; Fakhouri, F.; Taque, S.; Nobili, F.; Martinez, F.; et al. Recessive mutations in DGKE cause atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, B.B.; van Spronsen, F.; Diepstra, A.; Berger, R.M.; Komhoff, M. Renal thrombotic microangiopathy in patients with cblC defect: Review of an under-recognized entity. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2017, 32, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, A.; Go, R.S.; Fervenza, F.C.; Sethi, S. Thrombotic microangiopathy associated with monoclonal gammopathy. Kidney Int. 2017, 91, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, M.; Kang, Y.; Tan, Y.S.; Pavlov, V.I.; Liu, B.; Boyle, D.C.; Kushak, R.I.; Skjoedt, M.O.; Grabowski, E.F.; Taira, Y.; et al. Human mannose-binding lectin inhibitor prevents Shiga toxin-induced renal injury. Kidney Int. 2016, 90, 774–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morigi, M.; Galbusera, M.; Gastoldi, S.; Locatelli, M.; Buelli, S.; Pezzotta, A.; Pagani, C.; Noris, M.; Gobbi, M.; Stravalaci, M.; et al. Alternative pathway activation of complement by Shiga toxin promotes exuberant C3a formation that triggers microvascular thrombosis. J. Immunol. 2011, 187, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales, A.; Hofer, J.; Zimmerhackl, L.B.; Jungraithmayr, T.C.; Riedl, M.; Giner, T.; Strasak, A.; Orth-Holler, D.; Wurzner, R.; Karch, H.; et al. Need for long-term follow-up in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome due to late-emerging sequelae. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, 1413–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, M.; Valoti, E.; Piras, R.; Bresin, E.; Galbusera, M.; Tripodo, C.; Thaiss, F.; Remuzzi, G.; Noris, M. Two patients with history of STEC-HUS, posttransplant recurrence and complement gene mutations. Am. J. Transplant. 2013, 13, 2201–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, C.; Werber, D.; Cramer, J.P.; Askar, M.; Faber, M.; an der Heiden, M.; Bernard, H.; Fruth, A.; Prager, R.; Spode, A.; et al. Epidemic profile of Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli O104:H4 outbreak in Germany. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 1771–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitschke, M.; Sayk, F.; Hartel, C.; Roseland, R.T.; Hauswaldt, S.; Steinhoff, J.; Fellermann, K.; Derad, I.; Wellhoner, P.; Buning, J.; et al. Association between azithromycin therapy and duration of bacterial shedding among patients with Shiga toxin-producing enteroaggregative Escherichia coli O104:H4. JAMA 2012, 307, 1046–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, J.A.; Bougie, D.W.; Curtis, B.R.; Terrell, D.R.; Vesely, S.K.; Aster, R.H.; George, J.N. Drug-induced thrombotic microangiopathy: Experience of the Oklahoma Registry and the BloodCenter of Wisconsin. Am. J. Hematol. 2015, 90, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, R.; Reese, J.A.; George, J.N. Drug-induced thrombotic microangiopathy: An updated systematic review, 2014–2018. Am. J. Hematol. 2018, 93, E241–E243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glynne, P.; Salama, A.; Chaudhry, A.; Swirsky, D.; Lightstone, L. Quinine-induced immune thrombocytopenic purpura followed by hemolytic uremic syndrome. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1999, 33, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eremina, V.; Jefferson, J.A.; Kowalewska, J.; Hochster, H.; Haas, M.; Weisstuch, J.; Richardson, C.; Kopp, J.B.; Kabir, M.G.; Backx, P.H.; et al. VEGF inhibition and renal thrombotic microangiopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 1129–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keir, L.S.; Firth, R.; Aponik, L.; Feitelberg, D.; Sakimoto, S.; Aguilar, E.; Welsh, G.I.; Richards, A.; Usui, Y.; Satchell, S.C.; et al. VEGF regulates local inhibitory complement proteins in the eye and kidney. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brain, M.C.; Azzopardi, J.G.; Baker, L.R.; Pineo, G.F.; Roberts, P.D.; Dacie, J.V. Microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia and mucin-forming adenocarcinoma. Br. J. Haematol. 1970, 18, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroni, G.; Radice, A.; Giammarresi, G.; Quaglini, S.; Gallelli, B.; Leoni, A.; Li Vecchi, M.; Messa, P.; Sinico, R.A. Are laboratory tests useful for monitoring the activity of lupus nephritis? A 6-year prospective study in a cohort of 228 patients with lupus nephritis. Ann. Rheum Dis. 2009, 68, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tektonidou, M.G.; Sotsiou, F.; Nakopoulou, L.; Vlachoyiannopoulos, P.G.; Moutsopoulos, H.M. Antiphospholipid syndrome nephropathy in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid antibodies: Prevalence, clinical associations, and long-term outcome. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 50, 2569–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsen, A.; Nilsson, S.C.; Ahlqvist, E.; Svenungsson, E.; Gunnarsson, I.; Eriksson, K.G.; Bengtsson, A.; Zickert, A.; Eloranta, M.L.; Truedsson, L.; et al. Mutations in genes encoding complement inhibitors CD46 and CFH affect the age at nephritis onset in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2011, 13, R206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, M.O.; Leavis, H.L.; van Paassen, P.; van Rhenen, A.; Timmermans, S.; Ton, E.; van Laar, J.M.; Spierings, J. Severe thrombotic microangiopathy after autologous stem cell transplantation in systemic sclerosis: A case report. Rheumatology 2021, e1–e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodele, S.; Licht, C.; Goebel, J.; Dixon, B.P.; Zhang, K.; Sivakumaran, T.A.; Davies, S.M.; Pluthero, F.G.; Lu, L.; Laskin, B.L. Abnormalities in the alternative pathway of complement in children with hematopoietic stem cell transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Blood 2013, 122, 2003–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavriilaki, E.; Chrysanthopoulou, A.; Sakellari, I.; Batsis, I.; Mallouri, D.; Touloumenidou, T.; Papalexandri, A.; Mitsios, A.; Arampatzioglou, A.; Ritis, K.; et al. Linking Complement Activation, Coagulation, and Neutrophils in Transplant-Associated Thrombotic Microangiopathy. Thromb. Haemost. 2019, 119, 1433–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, M.; Timmermans, S.A.; Nagy, M.; Visser, M.; Huckriede, J.; Aendekerk, J.P.; De Vries, F.; Potjewijd, J.; Jallah, B.; Ysermans, R.; et al. Neutrophils and Contact Activation of Coagulation as Potential Drivers of COVID-19. Circulation 2020, 142, 1787–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, M.; Hook, C.C.; Leung, N.; Winters, J.L.; Go, R.S.; Mayo Clinic Complement Alternative Pathway‐Thrombotic Microangiopathy Disease-Oriented Group. Postsurgical thrombotic microangiopathy: Case series and review of the literature. Eur. J. Haematol. 2019, 103, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, S.; Abdul-Hamid, M.H.; van Paassen, P.; Limburg Renal, R. Chronic thrombotic microangiopathy in patients with a C3 gain of function protein. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2020, 35, 1449–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noris, M.; Galbusera, M.; Gastoldi, S.; Macor, P.; Banterla, F.; Bresin, E.; Tripodo, C.; Bettoni, S.; Donadelli, R.; Valoti, E.; et al. Dynamics of complement activation in aHUS and how to monitor eculizumab therapy. Blood 2014, 124, 1715–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuber, J.; Frimat, M.; Caillard, S.; Kamar, N.; Gatault, P.; Petitprez, F.; Couzi, L.; Jourde-Chiche, N.; Chatelet, V.; Gaisne, R.; et al. Use of Highly Individualized Complement Blockade Has Revolutionized Clinical Outcomes after Kidney Transplantation and Renal Epidemiology of Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 30, 2449–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavriilaki, E.; Yuan, X.; Ye, Z.; Ambinder, A.J.; Shanbhag, S.P.; Streiff, M.B.; Kickler, T.S.; Moliterno, A.R.; Sperati, C.J.; Brodsky, R.A. Modified Ham test for atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Blood 2015, 125, 3637–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).