Avian Immunoglobulin Y Antibodies Targeting the Protruding or Shell Domain of Norovirus Capsid Protein Neutralize Norovirus Replication in the Human Intestinal Enteroid System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selected Norovirus P and S Domains

2.2. Recombinant P and S Domain Protein Production

2.3. Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

2.4. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

2.5. Gel-Filtration Chromatography

2.6. Electron Microscopy

2.7. Immunization of Laying Hens

2.8. IgY Extraction

2.9. Norovirus-Specific Antibody Determination

2.10. Blocking Titers Against Norovirus P Particle-HBGA Interaction

2.11. HIE-Based Norovirus Neutralization Assays

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

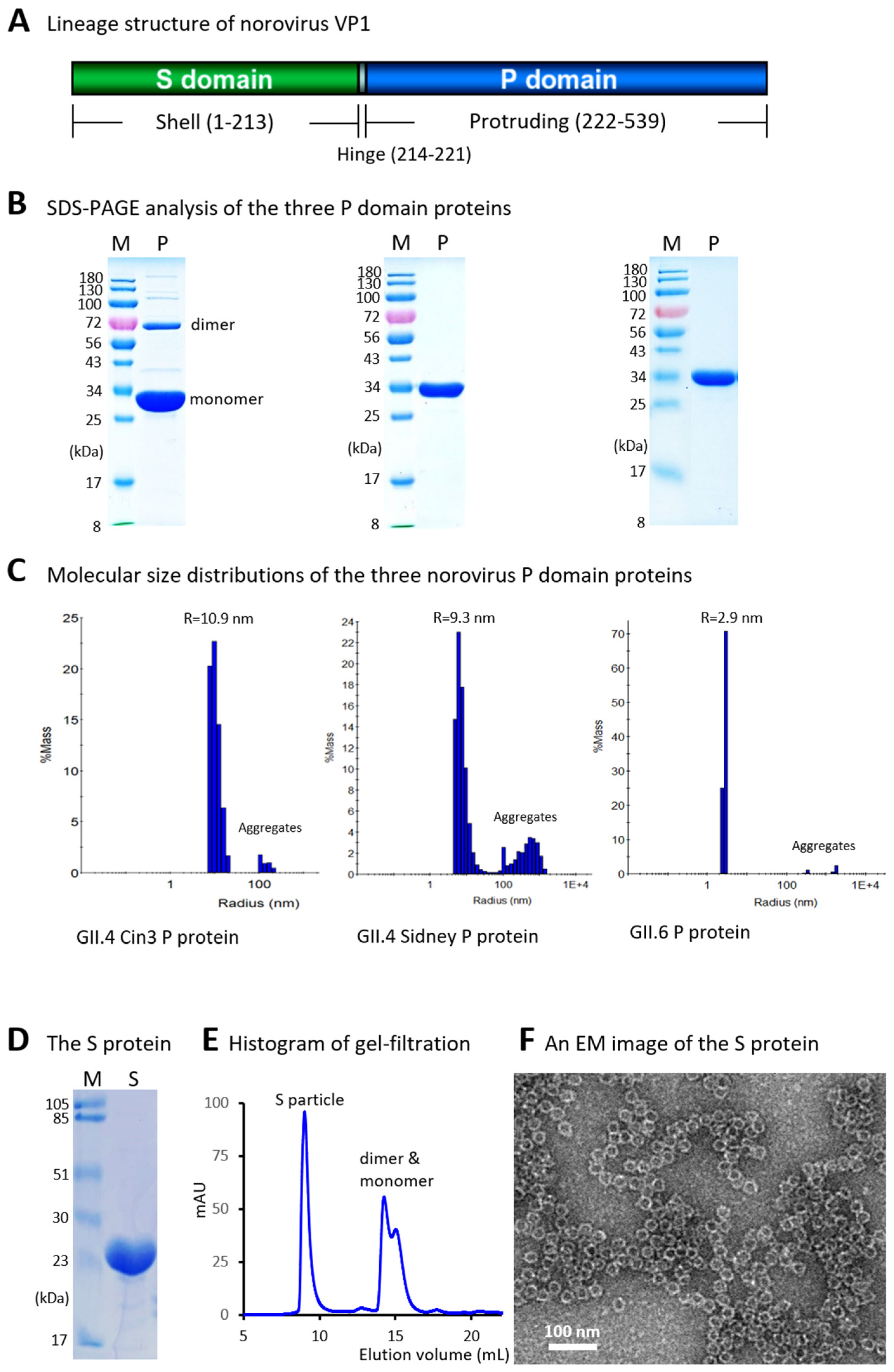

3.1. Production and Characterization of Norovirus P Domain Proteins

3.2. Generation and Evaluation of Norovirus S Domain Proteins

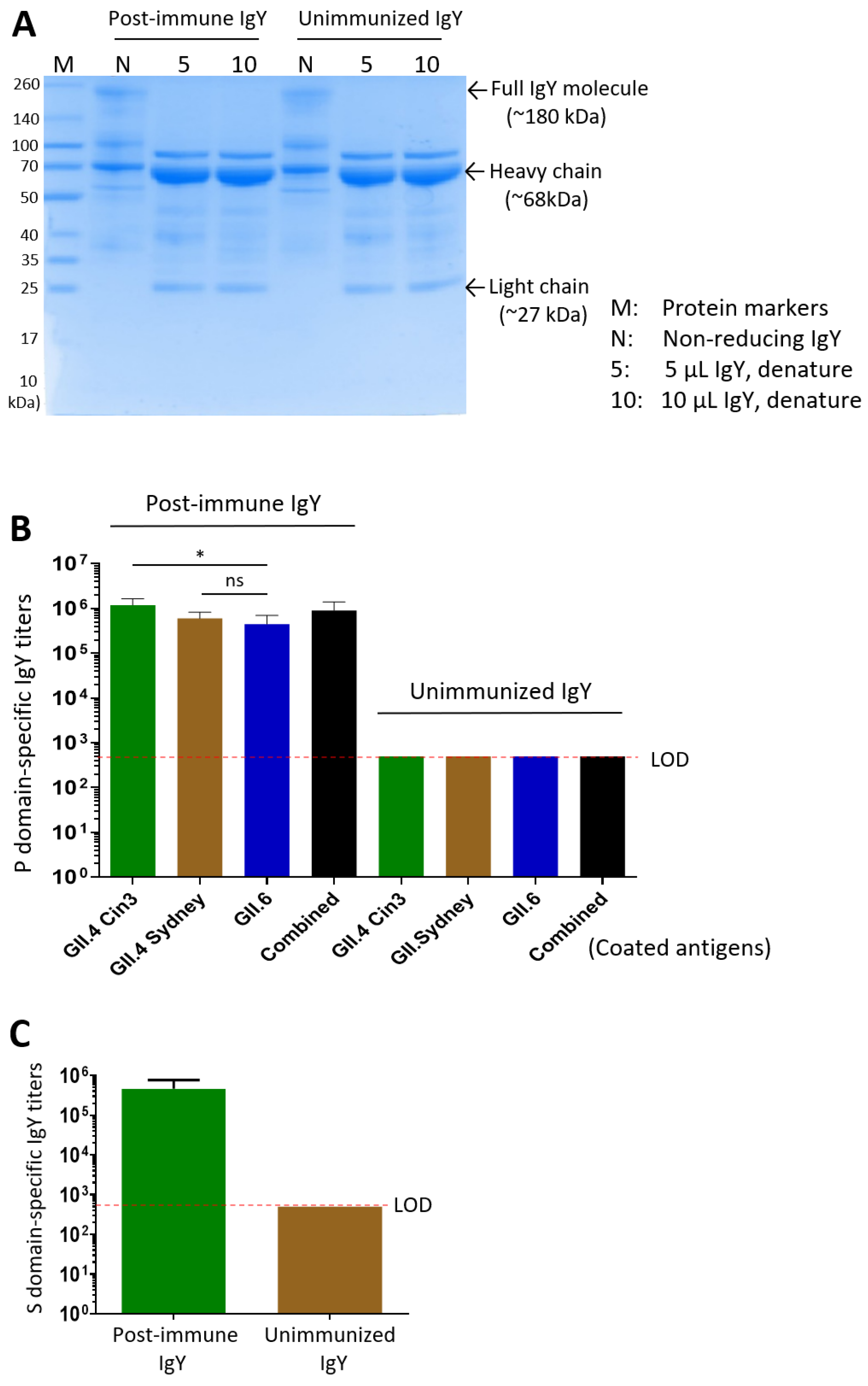

3.3. Yolk IgY Production and Characterization

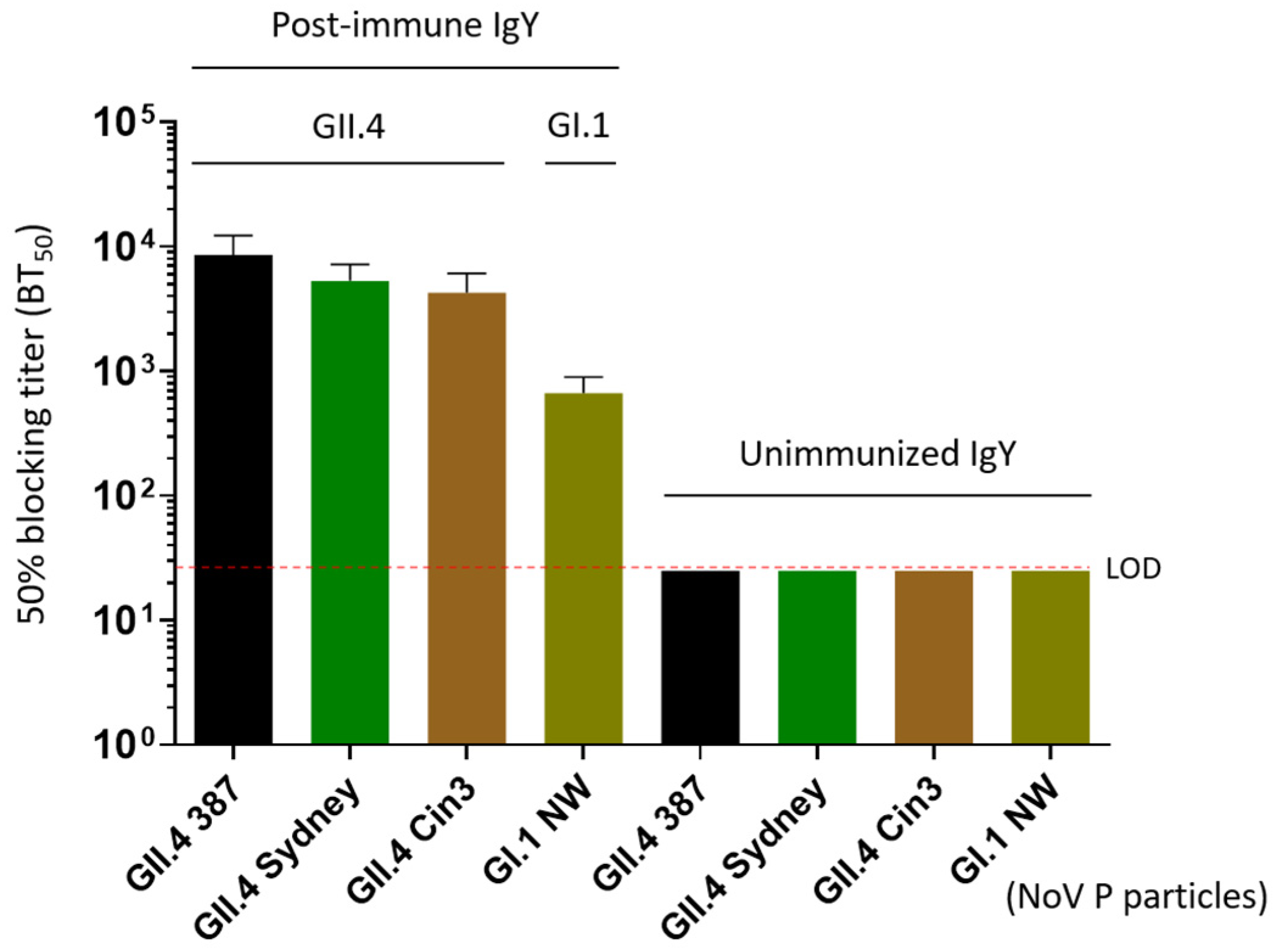

3.4. Blockade of the IgY on Norovirus P Particle-HBGA Interaction

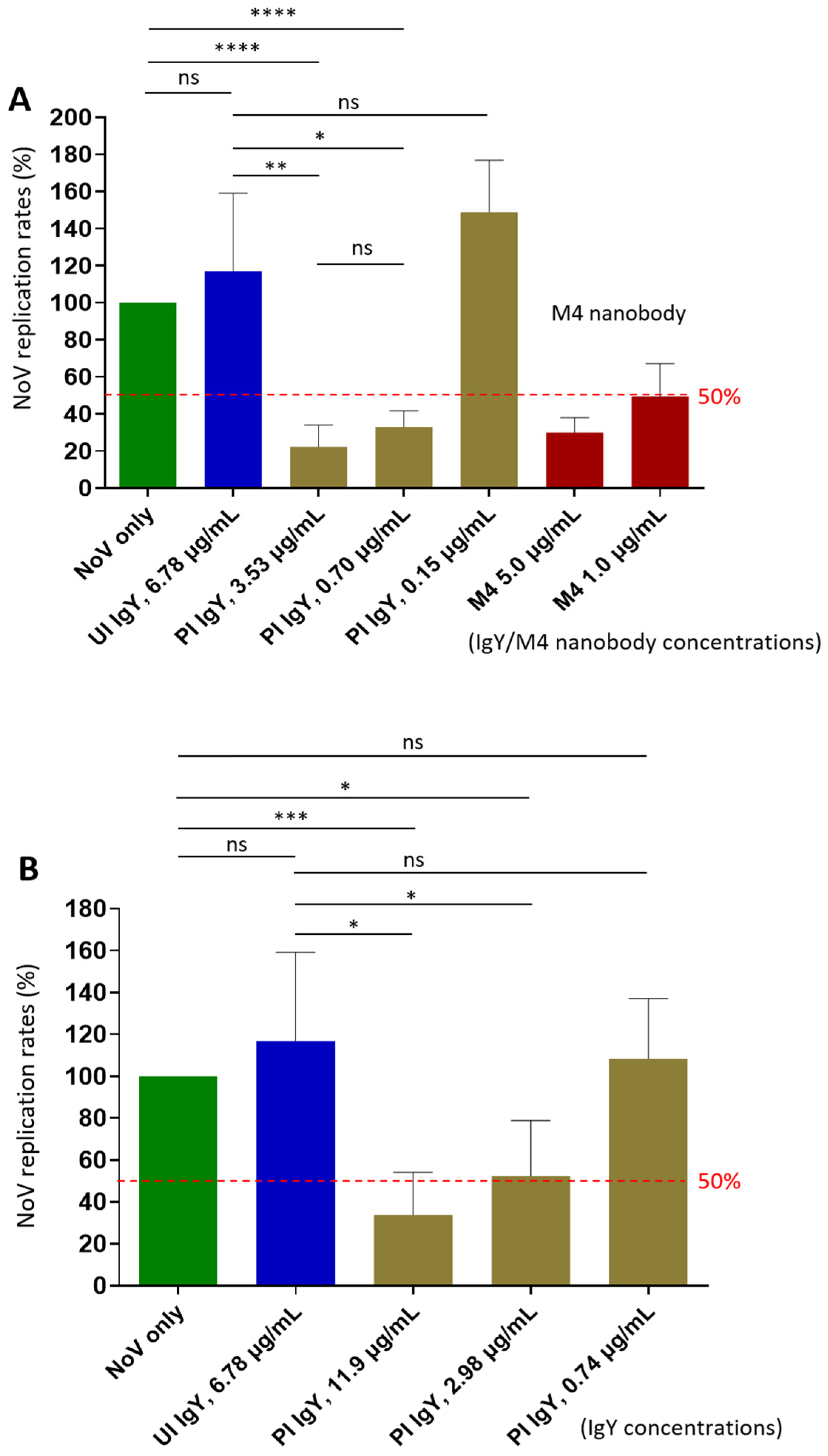

3.5. Neutralization Effects of the Post-Immune IgY on Norovirus Replication

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IgY | Immunoglobulin Y |

| P domain | Protruding domain |

| S domain | Shell domain |

| VP1 | Viral protein 1 |

| HIE | Human intestinal enteroid |

| BT50 | 50% blocking titer |

| µg | Microgram |

| mL | Milliliter |

| AGE | Acute gastroenteritis |

| LMICs | Low- to middle-income countries |

| HICs | High-income countries |

| CDC | the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| NoroSTAT | the Norovirus Sentinel Testing and Tracking |

| HBGAs | Histo-blood group antigens |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| DLS | Dynamic light scattering |

| FPLC | Fast Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| DTT | Dithiothreitol |

| KDa | Kilodalton |

| MDa | Megadalton |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| BCA | Bicinchoninic acid |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| HRP | Horseradish peroxidase |

| OD | Optical density |

| GCDCA | Glycochenodeoxycholic acid |

| ORF | Open reading frame |

| NT50 | 50% neutralization titer |

| NIH | The National Institute of Health |

| IACUC | Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee |

| GST | Glutathione S-transferase |

| FCV | Feline calicivirus |

| VLP | Virus-like particle |

| HA | Hemagglutinin |

References

- Robilotti, E.; Deresinski, S.; Pinsky, B.A. Norovirus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 134–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, K.; Chanock, R.; Kapikian, A. Human Calicivirus. In Fields Virology, 4th ed.; Knipe, D.M., Howley, P.M., Griffin, D.E., Lamb, R.A., Martin, M.A., Roizman, B., Straus, S.E., Eds.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2001; Volume 2, pp. 841–874. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, K.B.; Dilley, A.; O’Grady, T.; Johnson, J.A.; Lopman, B.; Viscidi, E. A narrative review of norovirus epidemiology, biology, and challenges to vaccine development. npj Vaccines 2024, 9, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, B.V.V.; Atmar, R.L.; Ramani, S.; Palzkill, T.; Song, Y.; Crawford, S.E.; Estes, M.K. Norovirus replication, host interactions and vaccine advances. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 23, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaythorpe, K.A.M.; Trotter, C.L.; Lopman, B.; Steele, M.; Conlan, A.J.K. Norovirus transmission dynamics: A modelling review. Epidemiol. Infect. 2018, 146, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitler, E.J.; Matthews, J.E.; Dickey, B.W.; Eisenberg, J.N.; Leon, J.S. Norovirus outbreaks: A systematic review of commonly implicated transmission routes and vehicles. Epidemiol. Infect. 2013, 141, 1563–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, J.L.; Lopman, B.A.; Payne, D.C.; Vinje, J. Birth Cohort Studies Assessing Norovirus Infection and Immunity in Young Children: A Review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 69, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, L.; Wolter, J.; De Coster, I.; Van Damme, P.; Verstraeten, T. A decade of norovirus disease risk among older adults in upper-middle and high income countries: A systematic review. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.; Yune, P.; Rao, M. Norovirus disease among older adults. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, 20499361221136760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, K.Y. Norovirus infection in immunocompromised hosts. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, S.M.; Fischer-Walker, C.L.; Lanata, C.F.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Hall, A.J.; Kirk, M.D.; Duarte, A.S.; Black, R.E.; Angulo, F.J. Aetiology-Specific Estimates of the Global and Regional Incidence and Mortality of Diarrhoeal Diseases Commonly Transmitted through Food. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.M.; Hall, A.J.; Robinson, A.E.; Verhoef, L.; Premkumar, P.; Parashar, U.D.; Koopmans, M.; Lopman, B.A. Global prevalence of norovirus in cases of gastroenteritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartsch, S.M.; Lopman, B.A.; Ozawa, S.; Hall, A.J.; Lee, B.Y. Global Economic Burden of Norovirus Gastroenteritis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Norovirus Facts and Stats; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- NoroSTAT. NoroSTAT Data; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- CaliciNet. CaliciNet Data; CaliciNet: Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Barclay, L.; Vinje, J. Increasing Predominance of Norovirus GII.17 over GII.4, United States, 2022–2025. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2025, 31, 1471–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flitter, B.A.; Gillard, J.; Greco, S.N.; Apkarian, M.D.; D’Amato, N.P.; Nguyen, L.Q.; Neuhaus, E.D.; Hailey, D.C.M.; Pasetti, M.F.; Shriver, M.; et al. An oral norovirus vaccine generates mucosal immunity and reduces viral shedding in a phase 2 placebo-controlled challenge study. Sci. Transl. Med. 2025, 17, eadh9906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaxart. Vaxart Announces Topline Data from the Phase 2 Challenge Study of its Monovalent Norovirus Vaccine Candidate; Vaxart: South San Francisco, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- HilleVax. HilleVax Reports Topline Data from NEST-IN1 Phase 2b Clinical Study of HIL-214 in Infants; HilleVax: Boston, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, B.V.; Hardy, M.E.; Dokland, T.; Bella, J.; Rossmann, M.G.; Estes, M.K. X-ray crystallographic structure of the Norwalk virus capsid. Science 1999, 286, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Huang, P.; Xia, M.; Fang, P.A.; Zhong, W.; McNeal, M.; Wei, C.; Jiang, W.; Jiang, X. Norovirus P particle, a novel platform for vaccine development and antibody production. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Huang, P.; Sun, C.; Han, L.; Vago, F.S.; Li, K.; Zhong, W.; Jiang, W.; Klassen, J.S.; Jiang, X.; et al. Bioengineered Norovirus S60 Nanoparticles as a Multifunctional Vaccine Platform. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 10665–10682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.; Samardzic, K.; Wallach, M.; Frumkin, L.R.; Mochly-Rosen, D. Immunoglobulin Y for Potential Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications in Infectious Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 696003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettayebi, K.; Crawford, S.E.; Murakami, K.; Broughman, J.R.; Karandikar, U.; Tenge, V.R.; Neill, F.H.; Blutt, S.E.; Zeng, X.L.; Qu, L.; et al. Replication of human noroviruses in stem cell-derived human enteroids. Science 2016, 353, 1387–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettayebi, K.; Kaur, G.; Patil, K.; Dave, J.; Ayyar, B.V.; Tenge, V.R.; Neill, F.H.; Zeng, X.L.; Speer, A.L.; Di Rienzi, S.C.; et al. Insights into human norovirus cultivation in human intestinal enteroids. mSphere 2024, 9, e0044824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Hegde, R.S.; Jiang, X. The P domain of norovirus capsid protein forms dimer and binds to histo-blood group antigen receptors. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 6233–6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, M.; Jiang, X. The p domain of norovirus capsid protein forms a subviral particle that binds to histo-blood group antigen receptors. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 14017–14030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, M.; Huang, P.; Vago, F.; Kawagishi, T.; Ding, S.; Greenberg, H.B.; Jiang, W.; Tan, M. A Viral Protein 4-Based Trivalent Nanoparticle Vaccine Elicited High and Broad Immune Responses and Protective Immunity against the Predominant Rotaviruses. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 6673–6689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artman, C.; Brumfield, K.D.; Khanna, S.; Goepp, J. Avian antibodies (IgY) targeting spike glycoprotein of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) inhibit receptor binding and viral replication. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauly, D.; Chacana, P.A.; Calzado, E.G.; Brembs, B.; Schade, R. IgY technology: Extraction of chicken antibodies from egg yolk by polyethylene glycol (PEG) precipitation. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 2011, 51, e3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, K.; Tenge, V.R.; Karandikar, U.C.; Lin, S.C.; Ramani, S.; Ettayebi, K.; Crawford, S.E.; Zeng, X.L.; Neill, F.H.; Ayyar, B.V.; et al. Bile acids and ceramide overcome the entry restriction for GII.3 human norovirus replication in human intestinal enteroids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 1700–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenge, V.; Ayyar, B.V.; Ettayebi, K.; Crawford, S.E.; Hayes, N.M.; Shen, Y.T.; Neill, F.H.; Atmar, R.L.; Estes, M.K. Bile acid-sensitive human norovirus strains are susceptible to sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2 inhibition. J. Virol. 2024, 98, e0202023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmen, W.; Hu, L.; Bok, M.; Chaimongkol, N.; Ettayebi, K.; Sosnovtsev, S.V.; Soni, K.; Ayyar, B.V.; Shanker, S.; Neill, F.H.; et al. A single nanobody neutralizes multiple epochally evolving human noroviruses by modulating capsid plasticity. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeck, A.; Kavanagh, O.; Estes, M.K.; Opekun, A.R.; Gilger, M.A.; Graham, D.Y.; Atmar, R.L. Serological correlate of protection against norovirus-induced gastroenteritis. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 202, 1212–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindesmith, L.C.; Ferris, M.T.; Mullan, C.W.; Ferreira, J.; Debbink, K.; Swanstrom, J.; Richardson, C.; Goodwin, R.R.; Baehner, F.; Mendelman, P.M.; et al. Broad blockade antibody responses in human volunteers after immunization with a multivalent norovirus VLP candidate vaccine: Immunological analyses from a phase I clinical trial. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmar, R.L.; Bernstein, D.I.; Lyon, G.M.; Treanor, J.J.; Al-Ibrahim, M.S.; Graham, D.Y.; Vinje, J.; Jiang, X.; Gregoricus, N.; Frenck, R.W.; et al. Serological Correlates of Protection against a GII.4 Norovirus. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. CVI 2015, 22, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford-Siltz, L.A.; Wales, S.; Tohma, K.; Gao, Y.; Parra, G.I. Genotype-Specific Neutralization of Norovirus Is Mediated by Antibodies Against the Protruding Domain of the Major Capsid Protein. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 225, 1205–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, M.J.; McElwee, M.; Azmi, L.; Gabrielsen, M.; Byron, O.; Goodfellow, I.G.; Bhella, D. Calicivirus VP2 forms a portal-like assembly following receptor engagement. Nature 2019, 565, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, M.; Sharma, S.; Kumar, B.; Rajput, R. Protective immunity based on the conserved hemagglutinin stalk domain and its prospects for universal influenza vaccine development. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 546274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Hashem, A.M.; Chen, Z.; Li, C.; Doyle, T.; Zhang, Y.; Yi, Y.; Farnsworth, A.; Xu, K.; Li, Z.; et al. Targeting the HA2 subunit of influenza A virus hemagglutinin via CD40L provides universal protection against diverse subtypes. Mucosal Immunol. 2015, 8, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, C.; Wang, B.Z. Advancing universal influenza vaccines: Insights from cellular immunity targeting the conserved hemagglutinin stalk domain in humans. EBioMedicine 2024, 104, 105172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xia, M.; Ichou, M.; Landivar, M.; Zhou, P.; Vadlamudi, S.N.; Leruth, A.; Nyblade, C.; Cox, P.; Yuan, L.; Goepp, J.; et al. Avian Immunoglobulin Y Antibodies Targeting the Protruding or Shell Domain of Norovirus Capsid Protein Neutralize Norovirus Replication in the Human Intestinal Enteroid System. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1228. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121228

Xia M, Ichou M, Landivar M, Zhou P, Vadlamudi SN, Leruth A, Nyblade C, Cox P, Yuan L, Goepp J, et al. Avian Immunoglobulin Y Antibodies Targeting the Protruding or Shell Domain of Norovirus Capsid Protein Neutralize Norovirus Replication in the Human Intestinal Enteroid System. Vaccines. 2025; 13(12):1228. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121228

Chicago/Turabian StyleXia, Ming, Mohamed Ichou, Mathew Landivar, Peng Zhou, Sai Navya Vadlamudi, Alice Leruth, Charlotte Nyblade, Paul Cox, Lijuan Yuan, Julius Goepp, and et al. 2025. "Avian Immunoglobulin Y Antibodies Targeting the Protruding or Shell Domain of Norovirus Capsid Protein Neutralize Norovirus Replication in the Human Intestinal Enteroid System" Vaccines 13, no. 12: 1228. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121228

APA StyleXia, M., Ichou, M., Landivar, M., Zhou, P., Vadlamudi, S. N., Leruth, A., Nyblade, C., Cox, P., Yuan, L., Goepp, J., & Tan, M. (2025). Avian Immunoglobulin Y Antibodies Targeting the Protruding or Shell Domain of Norovirus Capsid Protein Neutralize Norovirus Replication in the Human Intestinal Enteroid System. Vaccines, 13(12), 1228. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121228