Abstract

The current systematic review presents COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among parents for their children in Middle Eastern countries. Moreover, the vaccine acceptance rate of parents from the Middle East and the factors effecting the acceptance rate were reviewed and summarized. For this systematic review, basic electronic academic databases (Scopus, Science Direct, ProQuest, Web of Science and PubMed) were used for the search, along with a manual search on Google Scholar. This systematic review was conducted by following the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)” guidelines. Moreover, utilizing the framework of the PECO-S (Population Exposure Comparison Outcome Study design), various observational studies were recruited for this review. Out of 2123 studies, 25 studies meeting the inclusion criteria were included in the current review. All of the included studies were about parental vaccine hesitancy for COVID-19 in Middle Eastern countries and published during 2020–2022. Overall, 25 research papers comprising 10 different Middle Eastern countries with 33,558 parents were included. The average age of parents was 39.13 (range: 18–70) years, while the mean age of children was 7.95 (range: 0–18) years. The overall hesitancy rate was 44.2% with a SD of ± 19.7. The included studies presented enhanced COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among parents in Middle Eastern countries. The lower vaccine acceptance rate among parents was mainly because of a fear of the potential side effects. Furthermore, the lack of information regarding vaccine safety and efficacy, the fear of unreported side effects and concerns about the authenticity of vaccine development and preparation were the predictors of parental COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Middle Eastern countries.

1. Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2 “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus” is the causative agent of an infectious disease called COVID-19. This devastating respiratory tract infection was initially observed in “Wuhan”, the capital of the province Hubei, China, in December of 2019, which then swiftly spread worldwide [1,2,3,4]. The World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared COVID-19 a pandemic in March of 2020 [2,3,4]. The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in vicious morbidity and mortality worldwide and shattered global economies [3]. According to the WHO dashboard of COVID-19, the officially reported confirmed cases of COVID-19 infection as of 20 May 2022 were 521,920,560, with 6,274,323 reported deaths worldwide [4]. Furthermore, nearly 7.98 billion, i.e., 65.78% of the world’s population had received their first dose of the COVID-19 vaccination by May 2022 [3]. Hence, till July 2022, the global strategy of the WHO regarding “complete COVID-19 vaccination” was only halfway accomplished, especially in low-income and developing countries [5].

Since medieval times, vaccine hesitancy and rejection has been a pressing issue, especially in developing countries, including Middle Eastern countries [1,2,3,4]. Moreover, in the past few decades, the incidences of vaccine rejection have also increased worldwide [6]. Furthermore, due to a high vaccine rejection rate, the prevalence of vaccine-preventable diseases has also been significantly increased in recent years [2]. In fact, parents’ or guardians’ consent is required for the vaccination of children under the age of 18 years. Therefore, parents’ attitude, beliefs and behavior towards vaccine acceptance always play a significant role in children’s vaccination [7,8]. Parental vaccine hesitancy, despite the availability of the vaccines, is a prime barrier in childhood immunization [5].

Undeniably, COVID-19 was a rare infection that significantly contributed to plenteous causalities worldwide. However, the COVID-19 vaccine was developed and synthesized in the least time possible [9]. Therefore, the general population all over the world, especially parents, had concerns regarding the authenticity, developmental protocols and validation procedures of the newly developed COVID-19 vaccines [10,11]. Hence, this review was designed to observe and present the parental hesitancy/rejection rate, and acceptance rate of COVID-19 vaccines in vaccinating their children against COVID-19. Specifically, the present systematic review focuses on parents’ attitude towards vaccinating their children against COVID-19 across Middle Eastern countries. Moreover, the current systematic review will also identify the predictors and factors related to the hesitant attitude of parents towards the COVID-19 vaccination. The observations of this review will be helpful in understanding various parental concerns regarding child COVID-19 vaccines. This systematic review will also provide a basis for designing and implementing targeted healthcare strategies by concerned authorities, specifically in Middle Eastern countries.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The Cochrane handbook was used as the main source of guidance for this systematic review. Moreover, the study protocols were in accordance with the PRISMA flow statement guidelines. The keywords used for finding the research studies included ‘COVID-19 vaccine’, ‘children COVID-19 vaccination’, ‘COVID-19 vaccination in Middle Eastern countries’, ‘parental COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy’ and ‘parental acceptance rate of COVID-19 vaccine’. For the present systematic review, electronic databases (Scopus, Science Direct, ProQuest, Web of Science and PubMed) were used for the study search, along with a manual search on Google Scholar. Utilizing the framework of the PECO-S (Population Exposure Comparison Outcome Study design), various observational studies were recruited. The search was restricted to the English language and COVID-19 vaccine studies published from January 2020 to December 2022 were included. Out of 2123 studies obtained, 25 studies that met the inclusion criteria were included in this systematic review.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

- (1)

- The study population were parents.

- (2)

- The studies were from Middle Eastern countries.

- (3)

- The studies were on the COVID-19 vaccine for children.

- (4)

- The study design of the included studies was observational cross-sectional.

- (5)

- The studies were published in the English language.

- (6)

- The studies were published in peer-reviewed journals.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

- (1)

- The studies with general population or healthcare providers.

- (2)

- The studies outside of Middle Eastern countries.

- (3)

- The studies with study design other than observational cross-sectional.

- (4)

- The studies published in languages other than English.

2.4. Data Extraction

The data extracted from the included studies were comprised author details, year of the study, country of the study, mean age and educational background of the parents in the included studies, study design, sample size, parental vaccine acceptance rate, parental vaccine hesitancy rate and predictors (reported reasons) of the vaccine hesitancy among the parents. The “Cochrane Bias” tool of LvE for risk assessment was utilized to rule out the risk of biasness. This biasness assessment was further verified by KT, HdG and LvD.

2.5. Data Synthesis and Analysis

The parental COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate was accessed in all of the included studies. Moreover, the parental COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy rate as well as the predictors (reasons) of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy were also investigated in all of the included studies.

3. Results

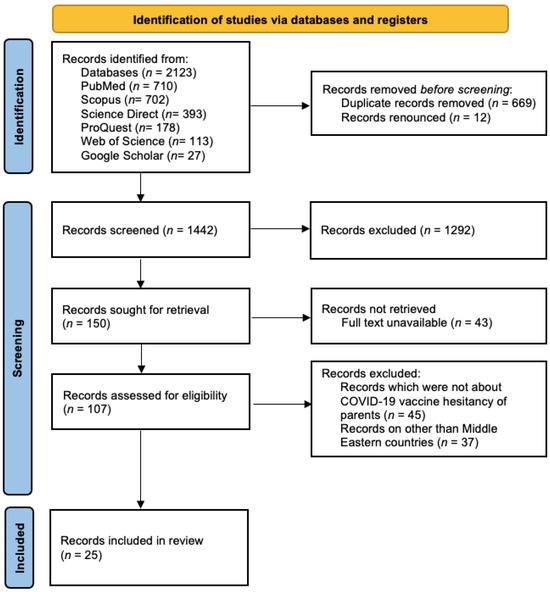

Through an electronic database search, a total of 2123 original research articles were identified, from which 1442 studies were screened after removing the duplicate records and renounced records. Among the 1442 screened studies, 1292 records were excluded that did not match the required keywords, and 150 study reports were shortlisted. Among the 150 shortlisted research articles, 43 studies were found as conference proceedings (abstract) only when the full-text articles were searched for. They were published in the special edition/issue of the journals as abstracts and were not available as full texts. After excluding them, a total of 107 studies were left for further evaluation. And among the 107 shortlisted studies, 45 studies were excluded as they were not about parental hesitancy towards the COVID-19 vaccine. Afterwards, a total of 37 studies that were conducted in countries other than Middle Eastern countries were also excluded. At the end, 25 studies were screened that met the inclusion criteria and were evaluated for the present systematic review. The details are described in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

For assessing the quality of cross-sectional studies, many tools are available, such as the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) adapted for cross-sectional studies, the NIH quality assessment tool (NIH-QAT) for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies, the Johanna Briggs institute checklist (JBIC) for analytical cross-sectional studies, and the appraisal tool for cross-sectional studies (AXIS tool/AXIS 20). We used the points AXIS 20 tool to check the quality of all the included studies. The AXIS tool is a critical appraisal tool that addresses issues in cross-sectional studies and reports on quality as well as the risk of bias in cross-sectional studies. The AXIS tool (developed in 2016), also known as AXIS 20, is a 20-point questionnaire that addresses key areas in cross-sectional studies, i.e., study design, sample size with justification, target population, sampling technique, validity and reliability of the study, and overall methodology of the study [12]. Table 1 presents the results of the quality assessment of the included studies using AXIS 20. The aims and objectives were clearly defined in the included studies. The majority of the included studies had an adequate study design and appropriate sample size. The results of the included studies were clearly defined and consistent. Moreover, no conflicts of interest were observed in any study that was included in this systematic review.

Table 1.

Quality assessment of included studies using AXIS tool.

The study settings (country of research), data collection time interval, study design, sample size, parental acceptance rate, hesitancy/rejection rate, as well as the predictors (reasons) for parental hesitancy were analyzed. All of the studies recruited for this review were observational, cross-sectional studies. Among all of the 25 included studies, only 1 study was published in 2020, 22 studies were published in 2021, and only 2 studies were published in 2022. The characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Study characteristics of the included studies.

Among the added research studies from Middle Eastern countries, the majority of the studies had clear objectives. On the other hand, none of the included studies had any funding sources or conflicts of interest that may affect the authors’ interpretation of the results. The majority of the included studies had a clearly defined target/reference population, except the study conducted by Sara et al. [15]. Some studies, such as those of Elkhadry SW et al. [16], Yulia G et al. [18], and Özlem A et al. [21], did not have a justified sample size. Similarly, all the included studies had ethical approval and the consent of the study participants.

Among the recruited studies from Middle Eastern countries, the majority of the studies, i.e., 11 original research studies, were from Saudi Arabia (KSA), 7 original research studies were from Turkey, 3 studies were from Jordan and 3 studies were from Israel. The rest of the studies included in this systematic review were from Qatar, Egypt, Iraq, Kuwait, Lebanon, Palestine and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). All of the added studies focused on the parents’ hesitancy regarding the COVID-19 vaccination for their children. The study duration for most of the studies was about 2–3 months.

4. Discussion

After the global outbreak of COVID-19, the main focus of healthcare authorities was to develop herd immunity among individuals worldwide [7]. Due to the highly infectious nature of COVID-19, it became necessary to immunize the maximum possible percentage of the population to minimize its widespread transmission [3]. Vaccine hesitancy and refusal had been a major issue faced by healthcare authorities across the globe [32]. Parental hesitancy regarding childhood immunization was a crucial problem that had affected a substantial number of children worldwide [36]. Multiple studies have been conducted regarding COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and the hesitancy towards it among parents in different parts of the world [9]. Similarly, several studies have also been conducted on the parental acceptance and hesitancy of routine vaccines [36]. Interestingly, it was observed that parents’ attitudes towards routine childhood immunization were more positive and accepting than towards COVID-19 vaccines, and they were more hesitant towards the COVID-19 vaccination for their children [35]. The present systematic review is focused on the parental COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate, hesitancy or refusal rate, along with factors (predictors) affecting parental COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy across Middle Eastern countries.

The general findings of this review present a clear picture: that the majority of parents in Middle Eastern countries were hesitant to get their children vaccinated against COVID-19. Similarly, a study conducted in Bangladesh presented a high percentage of parental vaccine hesitancy regarding the COVID-19 vaccination for their children [11]. However, these findings are contrary to the findings of studies conducted across various European countries, where the parental COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate for their children was much higher [36]. Similarly, the COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate of Italian parents for their children was higher as compared to in Arab countries [37]. The percentage of the population that has been fully vaccinated against COVID-19 in the USA, Italy, Hong Kong and UAE were at 36%, 13.7%, 10% and 38.8% as of May 2021, respectively [36]. Moreover, an observational cross-sectional study conducted on an American population also reported similar results, i.e., a high parental acceptance rate for the COVID-19 vaccine and a low hesitancy or refusal rate as compared to Middle Eastern countries [38].

Furthermore, some other studies presented somewhat similar results to the US but opposite to Middle Eastern countries, i.e., parents’ attitudes towards the COVID-19 vaccine for their children were more accepting as compared to Middle Eastern countries [7,9,10,37]. Likewise, a cross-sectional study conducted across the United Kingdom also presented a clear picture of the vaccine hesitancy rate among parents, but the parental COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy was still comparatively low as compared to Middle Eastern parents, especially Arabian mothers [30].

The present review depicts multiple reasons associated with parental COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy for their children across Middle Eastern countries. The most common reason for parental COVID-19 vaccine refusal and hesitancy was a lack of adequate information about the side effects of the COVID-19 vaccines. Another reason was the fear of acquiring COVID-19 infections even after the COVID-19 vaccination. It can be said that parents in Middle Eastern countries had trust issues regarding the COVID-19 vaccine synthesis and its development. Primarily, the COVID-19 vaccines were synthesized and prepared in a very short time, which raised a sense of mistrust among Middle Eastern parents. This in turn resulted in greater COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and an increased refusal rate among parents for their children.

Insufficient information regarding the COVID-19 vaccine efficacy and safety was the second most commonly reported reason among the parents who participated in the included studies. An absence of reliable scientific information regarding the COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness also resulted in high COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and reluctance among Middle Eastern parents. These results are better but contrary to the studies conducted in Asian countries such as India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, where parents presented COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy for themselves as well as for their children due to fake news, falsified myths, religious beliefs and self-imagined phony ideologies [39].

The findings of the present systematic review, in terms of the safety of the COVID-19 vaccines, are similar to the findings of the studies conducted in different European countries, where the main reason for parental COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy for children was the fear of unwanted side effects, poor COVID-19 vaccine safety knowledge and a lack of vaccine safety literature availability for the general population [6]. Likewise, most parents across the United States, as well as the United Kingdom, reported fear of the COVID-19 vaccine side effects as a major predictor of COVID-19 vaccine hesitant behavior [3,10,11,40].

The parental hesitancy rate for COVID-19 vaccines was observed to be 44.2% with a SD of ± 19.7% across Middle Eastern countries. Similarly, a cross-sectional study conducted on 3009 parents in eastern China presented similar results. According to that study, parental hesitancy regarding child routine immunization and COVID-19 immunization was around 40.7% [41]. Moreover, another study conducted among 223 parents presented an overall parental hesitancy of 99.4% regarding routine childhood immunizations [42]. In contrast, a cross-sectional study from Italy (437 Italian parents) reported less hesitancy regarding routine childhood immunizations. The Italian study demonstrated 34.7% parental hesitancy regarding routine childhood immunizations [43]. Similarly, another exploratory study among 199 parents from the United States presented 24% hesitancy regarding the influenza vaccine for their children [44].

The findings of the present systematic review, which are based on various studies across Middle Eastern countries, present a crucial need for healthcare authorities and health policy makers to address the reasons for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among parents. Furthermore, healthcare authorities should also promote productive, beneficial and valuable awareness regarding the benefits of the COVID-19 vaccine for children. Parents and guardians should also be instructed thoroughly about the long-term consequences of the COVID-19 vaccine. The parental COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate would be enhanced if parents were well-informed and aptly guided about the potential benefits of the COVID-19 vaccines.

Strength and Limitations

The current systematic review, which is based on studies conducted in different Middle Eastern countries, presents an enormous perspective on parental COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy. The included studies had large sample sizes. Therefore, this review brings to light the vaccination attitude of a large number of parents from Middle Eastern countries. The studies excluded from this review were in languages other than English or were conference proceedings as abstracts that were not available as full-length papers. Excluding such studies from this systematic review represents a small hindrance in understanding the parental trends and attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination for children. Additionally, this review did not recruit other subgroups of the professional population (healthcare professionals and workers) or the general population.

Further work should be conducted to explore the COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy rates and the reasons for this hesitancy among the general population and other professional subgroups of the population. Such data could be utilized by the local healthcare authorities to identify vaccination barriers and enhance vaccine acceptance.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this review revealed that most parents from Middle Eastern countries were hesitant to get their children vaccinated against COVID-19. The majority of the participants from the studies recruited for this systematic review were mothers. A few major reasons for the low acceptance rate and high hesitancy of the COVID-19 vaccines among parents were a lack of information regarding vaccine safety and efficacy and a fear of unreported side effects and concerns about the authenticity of the vaccine development and preparation. The findings from the current systematic review could be used by healthcare policy makers to design, compose and implement strategies that target and address COVID-19 vaccination barriers among parents.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.I. and S.-U.-D.K.; methodology, M.S.I.; formal analysis, S.V. and S.Q.; investigation, M.S.I. and S.Q.; resources, M.S.I., S.V. and S.-U.-D.K.; data curation, M.S.I., S.V. and S.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.I. and S.-U.-D.K.; writing—review and editing, S.V. and S.Q.; supervision, M.S.I.; project administration, S.-U.-D.K.; funding acquisition, M.S.I., S.V., S.Q. and S.-U.-D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research and Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia, for funding this research work through the project number (IF2/PSAU/2022/03/21896).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon a reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alrefaei, A.F.; Almaleki, D.; Alshehrei, F.; Kadasah, S.; ALluqmani, Z.; Alotaibi, A.; Alsulaimani, A.; Aljuhani, A.; Alruhaili, A. Assessment of health awareness and knowledge toward SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 vaccines among residents of Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2022, 13, 100935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amer, R.; Maneze, D.; Everett, B.; Montayre, J.; Villarosa, A.R.; Dwekat, E.; Salamonson, Y. COVID-19 vaccination intention in the first year of the pandemic: A systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022, 31, 62–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfattheicher, S.; Petersen, M.B.; Böhm, R. Information about herd immunity through vaccination and empathy promote COVID-19 vaccination intentions. Health Psychol. 2022, 41, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard: Overview, WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard|WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard with Vaccination Data. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 22 May 2022).

- Truong, J.; Bakshi, S.; Wasim, A.; Ahmad, M.; Majid, U. What factors promote vaccine hesitancy or acceptance during pandemics? A systematic review and thematic analysis. Health Promot. Int. 2022, 37, daab105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; McGoogan, J.M. Characteristics of and Important Lessons from the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72,314 Cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 2020, 323, 1239–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khlaiwi, T.; Meo, S.A.; Almousa, H.A.; Almebki, A.A.; Albawardy, M.K.; Alshurafa, H.H.; Alsayyari, M.S. National COVID-19 vaccine program and parent’s perception to vaccinate their children: A cross-sectional study. Vaccines 2022, 10, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altulahi, N.; AlNujaim, S.; Alabdulqader, A.; Alkharashi, A.; AlMalki, A.; AlSiari, F.; Bashawri, Y.; Alsubaie, S.; AlShahrani, D. Willingness, beliefs, and barriers regarding the COVID-19 vaccine in Saudi Arabia: A multiregional cross-sectional study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2021, 22, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obregon, R.; Mosquera, M.; Tomsa, S.; Chitnis, K. Vaccine Hesitancy and Demand for Immunization in Eastern Europe and Central Asia: Implications for the Region and Beyond. J. Health Commun. 2020, 25, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D.; Loe, B.S.; Chadwick, A.; Vaccari, C.; Waite, F.; Rosebrock, L.; Jenner, L.; Petit, A.; Lewandowsky, S.; Vanderslott, S.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: The Oxford coronavirus explanations, attitudes, and narratives survey (Oceans) II. Psychol. Med. 2020, 52, 3127–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, H.; Lawton, A.; Hossain, S.; Mustafa, A.H.M.G.; Razzaque, A.; Kuhn, R. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Temporary Foreign Workers from Bangladesh. Heal. Syst. Reform. 2021, 7, e1991550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, M.J.; Brennan, M.L.; Williams, H.C.; Dean, R.S. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigit, M.; Ozkaya-Parlakay, A.; Senel, E. Evaluation of COVID-19 Vaccine Refusal in Parents. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2021, 40, E134–E136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temsah, M.H.; Alhuzaimi, A.N.; Aljamaan, F.; Bahkali, F.; Al-Eyadhy, A.; Alrabiaah, A.; Alhaboob, A.; Bashiri, F.A.; Alshaer, A.; Temsah, O.; et al. Parental Attitudes and Hesitancy About COVID-19 vs. Routine Childhood Vaccinations: A National Survey. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 752323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, S.; Dergaa, I.; Abdulmalik, M.A.; Ammar, A.; Chamari, K.; Ben, S.H. BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among parents of 4023 young adolescents (12–15 years) in Qatar. Vaccines 2021, 9, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhadry, S.W.; Salem, T.A.E.H.; Elshabrawy, A.; Goda, S.S.; Bahwashy, H.A.A.; Youssef, N.; Hussein, M.; Ghazy, R.M. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Parents of Children with Chronic Liver Diseases. Vaccines 2022, 10, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yılmaz, M.; Sahin, M.K. Parents’ willingness and attitudes concerning the COVID-19 vaccine: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gendler, Y.; Ofri, L. Perception and Vaccine Hesitancy on Israeli Parents; Acceptance of the COVID-19 Vaccine for Their Children: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatatbeh, M.; Albalas, S.; Khatatbeh, H.; Momani, W.; Melhem, O.; Al Omari, O.; Tarhini, Z.; A’aqoulah, A.; Al-Jubouri, M.; Nashwan, A.J.; et al. Children’s rates of COVID-19 vaccination as reported by parents, vaccine hesitancy, and determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake among children: A multi-country study from the Eastern Mediterranean Region. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altulaihi, B.A.; Alaboodi, T.; Alharbi, K.G.; Alajmi, M.S.; Alkanhal, H.; Alshehri, A. Perception of Parents Towards COVID-19 Vaccine for Children in Saudi Population. Cureus 2021, 13, e18342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgün, Ö.; Kayaalp, G.K.; Demirkan, F.G.; Çakmak, F.; Tanatar, A.; Guliyeva, V.; Sönmez, H.E.; Ayaz, N.A. Exploring the attitudes, concerns, and knowledge regarding COVID-19 vaccine by the parents of children with rheumatic disease: Cross-sectional online survey. Vaccine 2022, 40, 1829–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soysal, G.; Durukan, E.; Akdur, R. The evaluation of vaccine hesitancy and refusal for childhood vaccines and the COVID-19 vaccine in individuals aged between 18 and 25 years. Turkish J. Immunol. 2021, 9, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennaceur, S.; Al-Mohaithef, M. Parents’ Willingness to Vaccinate Children against COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2022, 10, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çelik, M.Y. The thoughts of parents to vaccinate their children against COVID-19: An assessment of situations that may affect them. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2022, 35, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsulaiman, J.W.; Mazin, M.; Al-Shatanawi, T.N.; Kheirallah, K.A.; Allouh, M.Z. Parental Willingness to Vaccinate Their Children Against SARS-CoV-2 in Jordan: An Explanatory Cross-Sectional Study. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2022, 15, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldakhil, H.; Albedah, N.; Alturaiki, N.; Alajlan, R.; Abusalih, H. Vaccine hesitancy towards childhood immunizations as a predictor of mothers’ intention to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia. J. Infect. Public Health 2021, 14, 1497–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rang, H.P.; Dale, M.M.; Ritter, J.M.; Flower, R.J.; Henderson, G. Rang and Dale’s Pharmacology. Available online: https://books.google.com.pk/books?id=fGZ5rgEACAAJ&dq=rang+and+dale+pharmacology+pdf&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiRrOjonajcAhWjApoKHeGKAp4Q6AEILDAB (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- Atad, E.; Netzer, I.; Peleg, O.; Landsman, K.; Keren, D.; Edan-Reuven, S.; Baram-Tsabari, A. Vaccine-Hesitant Parents’ Considerations Regarding Covid-19 Vaccination of Adolescents. medRxiv 2021, preprint. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Nafeesah, A.S.; Aldamigh, A.S.; Almansoor, B.A.; Al-Wutayd, O.; AlE’ed, A.A. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on parents’ behavior toward scheduled pediatric vaccinations in Saudi Arabia. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries 2021, 15, 1054–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samannodi, M.; Alwafi, H.; Naser, A.Y.; Alabbasi, R.; Alsahaf, N.; Alosaimy, R.; Minshawi, F.; Almatrafi, M.; Khalifa, R.; Ekram, R.; et al. Assessment of caregiver willingness to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 4857–4864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almusbah, Z.; Alhajji, Z.; Alshayeb, Z.; Alhabdan, R.; Alghafli, S.; Almusabah, M.; Almuqarrab, F.; Aljazeeri, I.; Almuhawas, F. Caregivers’ Willingness to Vaccinate Their Children Against COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Cureus 2021, 13, e17243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocamaz, E.B.; Kocamaz, H. Awareness of Covid-19 and attitudes toward vaccination in parents of children between 0 and 18 years: A cross-sectional study. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2022, 65, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhazza, S.F.; Altalhi, A.M.; Alamri, K.M.; Alenazi, S.S.; Alqarni, B.A.; Almohaya, A.M. Parents’ Hesitancy to Vaccinate Their Children Against COVID-19, a Country-Wide Survey. Front. Public Heal. 2022, 10, 755073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shmueli, L. Parents’ intention to vaccinate their 5- to 11-year-old children with the COVID-19 vaccine: Rates, predictors and the role of incentives. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Qerem, W.; Al Bawab, A.Q.; Hammad, A.; Jaber, T.; Khdair, S.I.; Kalloush, H.; Ling, J.; Mosleh, R. Parents’ attitudes, knowledge and practice towards vaccinating their children against COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2044257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfieri, N.L.; Kusma, J.D.; Heard-Garris, N.; Davis, M.M.; Golbeck, E.; Barrera, L.; Macy, M.L. Parental COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy for children: Vulnerability in an urban hotspot. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aw, J.; Jie, J.; Seng, B.; Si, S.; Seah, Y.; Low, L.L. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy—A Scoping Review of Literature in High-Income Countries. Vaccines 2021, 2019, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padamsee, T.J.; Bond, R.M.; Dixon, G.N.; Hovick, S.R.; Na, K.; Nisbet, E.C.; Wegener, D.T.; Garrett, R.K. Changes in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Black and White individuals in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2144470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, R.D.; Bone, J.N.; Gelernter, R.; Krupik, D.; Ali, S.; Mater, A.; Thompson, G.C.; Yen, K.; Griffiths, M.A.; Klein, A.; et al. National COVID-19 vaccine program progress and parents’ willingness to vaccinate their children. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 4889–4895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanozia, R.; Arya, R. “Fake news”, religion, and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Media Asia 2021, 48, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xiu, S.; Zhao, S.; Wang, J.; Han, Y.; Dong, S.; Huang, J.; Cui, T.; Yang, L.; Shi, N.; et al. Vaccine hesitancy: COVID-19 and influenza vaccine willingness among parents in Wuxi, China—A cross-sectional study. Vaccines 2021, 9, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSayed, D.A.; Bou Raad, E.; Bekhit, S.A.; Sallam, M.; Ibrahim, N.M.; Soliman, S.; Abdullah, R.; Farag, S.; Ghazy, R.M. Validation and cultural adaptation of the parent attitudes about childhood vaccines (PACV) questionnaire in Arabic language widely spoken in a region with a high prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, F.; D’Alessandro, A.; Angelillo, I.F. Investigating Italian parents’ vaccine hesitancy: A cross-sectional survey. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2018, 14, 1558–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofstetter, A.M.; Simon, T.D.; Lepere, K.; Ranade, D.; Strelitz, B.; Englund, J.A.; Opel, D.J. Parental vaccine hesitancy and declination of influenza vaccination among hospitalized children. Hosp. Pediatr. 2018, 8, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).