Abstract

Essential oils (EOs) are complex volatile mixtures that exhibit antioxidant activity through both chemical and biological pathways. Phenolic constituents act as efficient chain-breaking radical-trapping antioxidants, whereas some non-phenolic terpenes operate through distinct mechanisms. Notably, γ-terpinene functions via a “radical export” pathway, generating hydroperoxyl radicals that intercept lipid peroxyl radicals and accelerate chain termination. Recent methodological advances, such as inhibited autoxidation kinetics, oxygen-consumption assays, and fluorescence-based lipid peroxidation probes, have enabled more quantitative evaluation of these activities. Beyond direct radical chemistry, EOs also regulate redox homeostasis by modulating signaling networks such as Nrf2/Keap1, thereby activating antioxidant response element–driven enzymatic defenses in cell and animal models. Phenolic constituents and electrophilic compounds bearing an α,β-unsaturated carbonyl structure may directly activate Nrf2 by modifying Keap1 cysteine residues, whereas non-phenolic terpenes likely depend on oxidative metabolism to form active electrophilic species. Despite broad evidence of antioxidant efficacy, molecular characterization of EO–protein interactions remains limited. This review integrates radical-chain dynamics with redox signaling biology to clarify the mechanistic basis of EO antioxidant activity and to provide a framework for future research.

1. Introduction

Essential oils (EOs) are volatile and aromatic secondary metabolites found in various plant organs, such as flowers, leaves, stems, bark, and roots [1]. They are complex mixtures of terpenes, terpenoids, and a variety of minor aromatic or aliphatic compounds [2]. The composition of EOs is determined by both genetic and environmental factors. These factors include plant species, specific part of the plant used, geographical origin, climate, and cultivation conditions [3]. Extraction methods can influence the chemical profile and bioactivity of essential oils, including hydro-distillation, steam distillation, cold pressing, solvent extraction and supercritical fluid extraction [4]. EOs have been traditionally used for their aroma and related functional properties, and are also applied as natural flavorings and preservatives in foods and beverages [5,6].

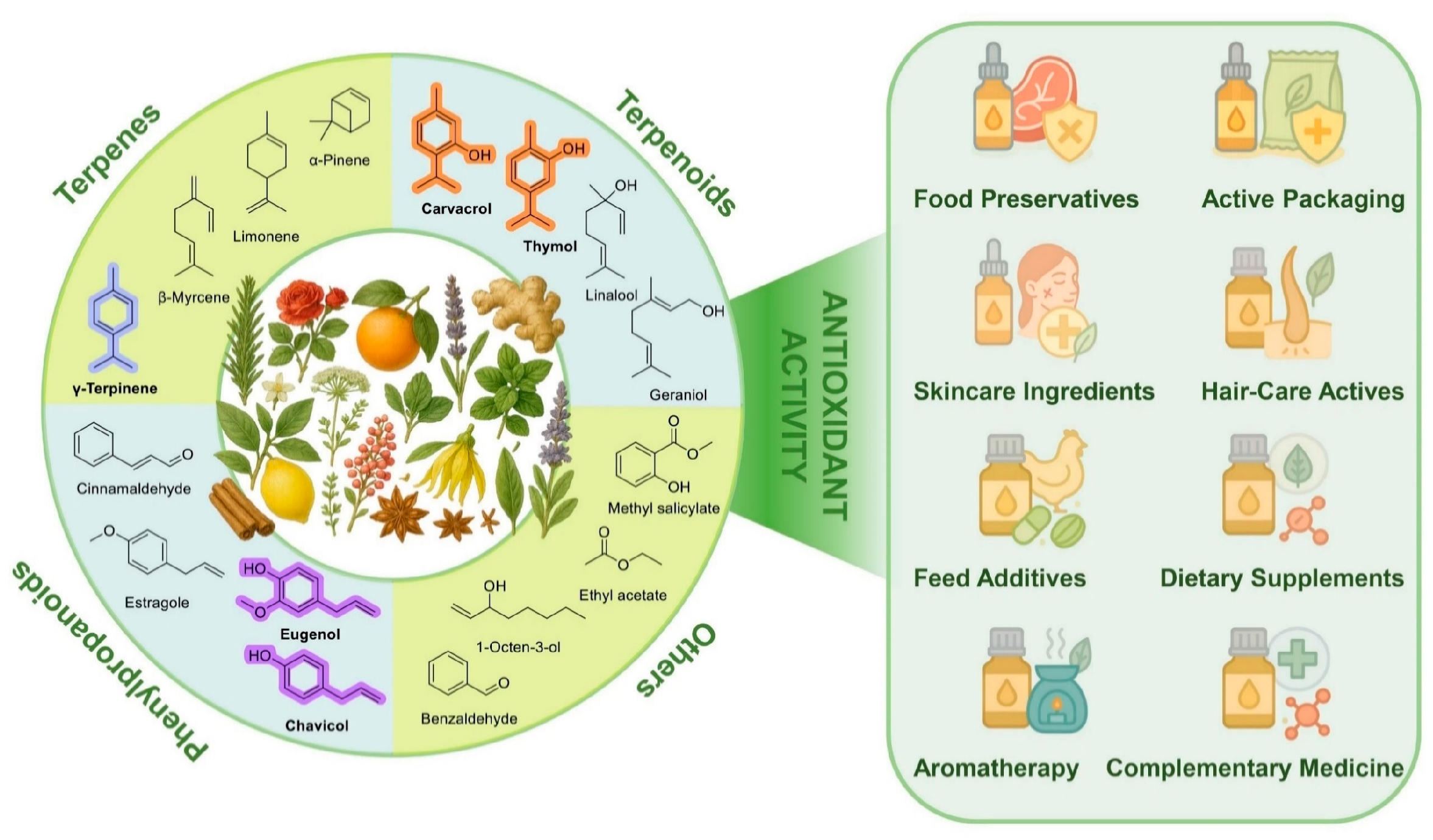

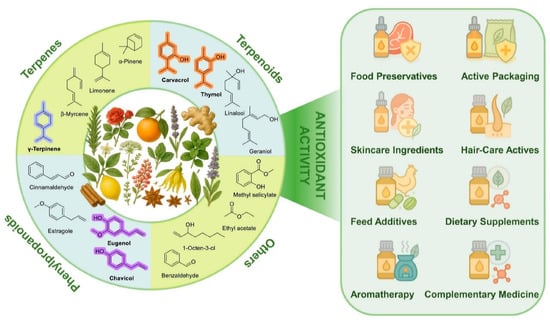

In recent years, interest in EOs has considerably grown because of their biological activities, among which antioxidant properties attracted increased recognition in food science and pharmacology (Figure 1). Their major constituents—terpenes, terpenoids and phenylpropanoids—exhibit characteristic redox behavior and support applications in food preservation, packaging, skincare, and nutraceuticals. Traditionally, the antioxidant properties of EOs have been attributed to their phenolic components [7]. Phenols are known for their ability to scavenge free radicals and chelate pro-oxidant metal ions [8]. Recent studies have shown that some non-phenolic compounds, in particular those having a pro-aromatic 1,4-cyclohexadiene structural motif, can also play a significant role in the antioxidant activity of EOs [9,10]. These compounds help interrupt oxidative chain reactions, thereby offering protection to both food products and living organisms from oxidative stress [11]. With growing understanding of their antioxidant mechanisms, the use of EOs as natural antioxidants has attracted considerable attention in food processing, cosmetics, and other fields. In food applications, EOs are used to slow down lipid oxidation and maintain product quality [12]. In cosmetics, EOs are added to formulations to mitigate the oxidative stress linked to skin aging and inflammation [13]. By limiting oxidative damage, EOs may also contribute to the prevention and management of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disorders [14]. Concerns regarding the safety of synthetic antioxidants have further intensified interest in effective natural alternatives [15]. Owing to their intrinsic antioxidant properties, EOs are now considered promising agents for natural preservation and health-related applications.

Figure 1.

Representative chemical classes of EO constituents, including terpenes, terpenoids, phenylpropanoids, and other volatile compounds, alongside selected botanical sources and representative functional applications.

A reliable assessment of the antioxidant activity is fundamental for both scientific research and practical applications, as it enables the identification and comparison of effective antioxidant agents. Preliminary studies on the antioxidant activity were based on simplified chemical assays such as 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical scavenging assay (DPPH), 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) radical cation decolorization assay (ABTS), ferric reducing antioxidant power assay (FRAP) and oxygen radical absorbance capacity assay (ORAC), which offered convenience and a rapid screening [16]. However, these tests are often unable to capture the complexity of the antioxidant mechanisms in real food matrices and living organisms [17]. More recent research has explored advanced chemical methods, cell-based models, and, to a lesser extent, in vivo approaches, aiming for a greater physiological relevance [18,19]. Despite these advances, large margins of uncertainty still exist, including the lack of standardization, the inherent variability in EO composition, and finally, difficulties in comparing the results of different studies. A comprehensive review in this context is, therefore, not only timely but also necessary to identify gaps, improve the strategies of evaluation and guide the rational use of EOs as natural antioxidants in food technology, cosmetic formulations, and medical practice.

This review examines the antioxidant activity of EOs from a mechanistic perspective, with the aim of bridging radical-chain chemistry and redox signaling regulation. Emphasis is placed on both classical chain-breaking radical-trapping mechanisms and non-classical pathways of radical interception. Current quantitative strategies, including inhibited autoxidation kinetics, oxygen-consumption measurements, and fluorescence-based probes, are critically evaluated in terms of their mechanistic resolution and inherent limitations, alongside complementary in vitro and in vivo models. Emerging methodologies with potential to advance EO antioxidant research are also highlighted. Finally, recent progress in understanding the modulation of the Nrf2/Keap1 pathway by EO constituents is discussed, with particular attention to the contributions of phenolic antioxidants and electrophilic non-phenolic compounds.

2. Methodology

The literature was surveyed using the Web of Science, Google Scholar, and PubMed databases. For antioxidant mechanisms and methodological aspects, searches were conducted using combinations of keywords related to radical propagation, lipid peroxidation, antioxidant assays, and methodology, without restriction on publication year, while prioritizing key studies from the past decade to capture recent conceptual and methodological advances. Studies addressing the antioxidant activity of EOs and their constituents were identified using keywords related to essential oils, terpenes, oxidative stress, Nrf2/Keap1 signaling, and ferroptosis. In this case, the search was limited to articles published between 2000 and September 2025. Selection was based on relevance to lipid peroxidation, cellular redox regulation, and mechanistic or cell-based evidence.

3. Mechanisms of Lipid Peroxidation

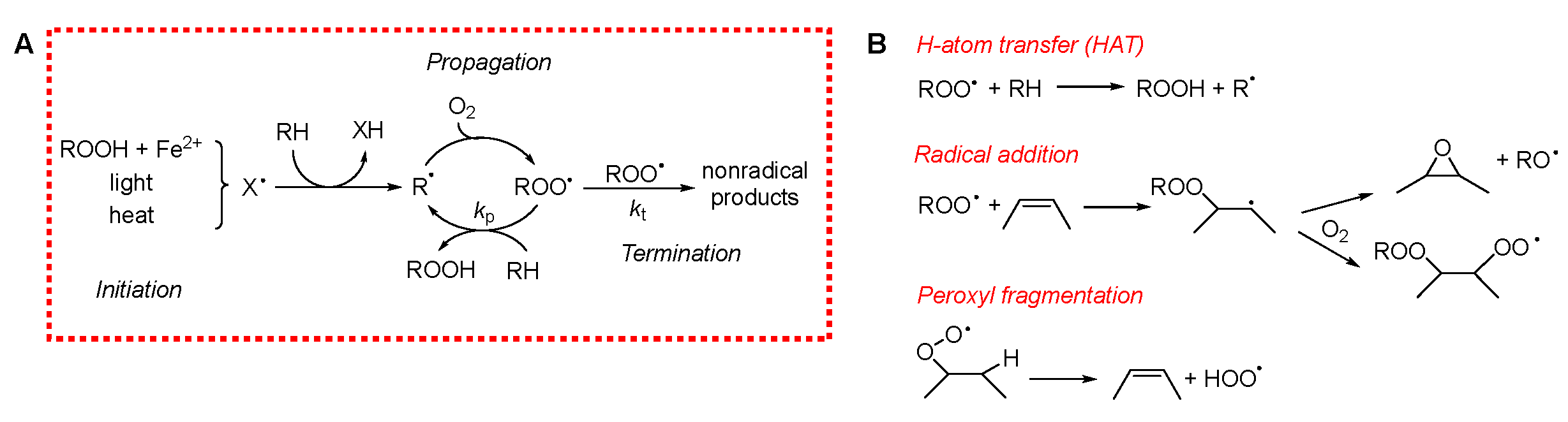

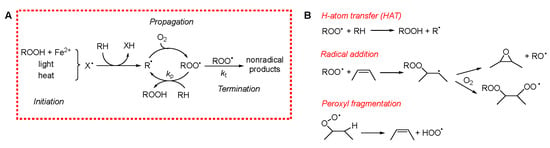

To evaluate the antioxidant potential of EOs, it is crucial to clearly define their primary target: the inhibition of lipid peroxidation in materials and the mitigation of oxidative stress in biological systems. Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are especially susceptible to peroxidation, both in stored materials and in living organisms, as they are abundant in cellular membranes. In foods, cellular membranes, and low-density lipoproteins (LDLs), PUFAs exposed to oxygen readily undergo an irreversible process called peroxidation or autoxidation. This reaction alters the flavor and aroma of edible products and generates toxic metabolites that can ultimately lead to cell death. Lipid peroxidation is among the most widespread organic reactions. It can be delayed or prevented through the use of antioxidants [20]. Despite the large variety of systems in which peroxidation occurs, the underlying mechanism is surprisingly similar. It involves a radical-chain reaction propagated by oxygen-centered peroxyl radicals (ROO•) [21]. Due to the extremely rapid reaction of carbon-centered (alkyl) radicals (R•) with molecular oxygen (triplet O2), virtually all R• species are converted to ROO• even at low O2 concentrations, making ROO• the predominant radical species in lipid peroxidation. Lipid peroxidation can broadly be divided into three mechanistic phases, illustrated in Scheme 1A.

Scheme 1.

(A) Mechanism of peroxidation. (B) Mechanism of chain propagation.

3.1. Initiation

Initiation involves the formation of radicals within the system. In food and other lipid-rich materials, this can occur via several pathways, including: a direct reaction of O2 with bis-allylic C–H bonds (often accelerated by heat) [22], photosensitized reactions [23], or metal-catalyzed decomposition of pre-existing hydroperoxides [24]. Due to the chain-propagating nature of the process, even a minimal rate of radical generation can result in significant oxidative damage over time, as a single initiating radical can lead to the oxidation of numerous lipid molecules.

3.2. Propagation

Propagation entails the reaction of the ROO• radical with a lipid substrate, leading to the formation of a lipid hydroperoxide (ROOH) and a new carbon-centered radical. This radical quickly reacts with O2 to regenerate ROO•, perpetuating the chain. In lipid systems, propagation predominantly affects PUFAs, as their bis-allylic hydrogens are several hundred times more reactive (at room temperature) towards ROO• than allylic or aliphatic sites [21]. However, the mechanisms of propagation can be more complex, potentially involving ROO• fragmentation into species such as hydroperoxyl radicals (HOO•) or alkoxyl radicals (RO•), thereby generating stable oxygen products like epoxides or carbonyl compounds [25].

3.3. Termination

Termination involves the removal of radical species from the system, predominantly through bimolecular reactions between radicals. For instance, two ROO• radicals may recombine to form a carbonyl compound and an alcohol. Although radical–radical reactions are intrinsically fast, the very low steady-state concentration of radicals in lipid systems makes termination a statistically rare process. This rarity becomes even more pronounced in compartmentalized systems, such as emulsions, where restricted diffusion further reduces the likelihood of productive radical encounters [21].

3.4. Products of Lipid Peroxidation

The products of lipid peroxidation can be broadly classified into early-stage products, generated directly during the radical chain process, and late-stage products, which arise from the subsequent degradation or transformation of these initial species. However, this distinction is not absolute, as certain compounds can originate from both direct radical pathways and secondary transformation processes (see, for example, Scheme 1B).

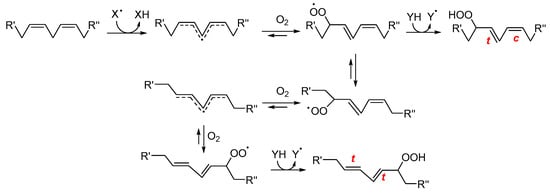

3.4.1. Early Products

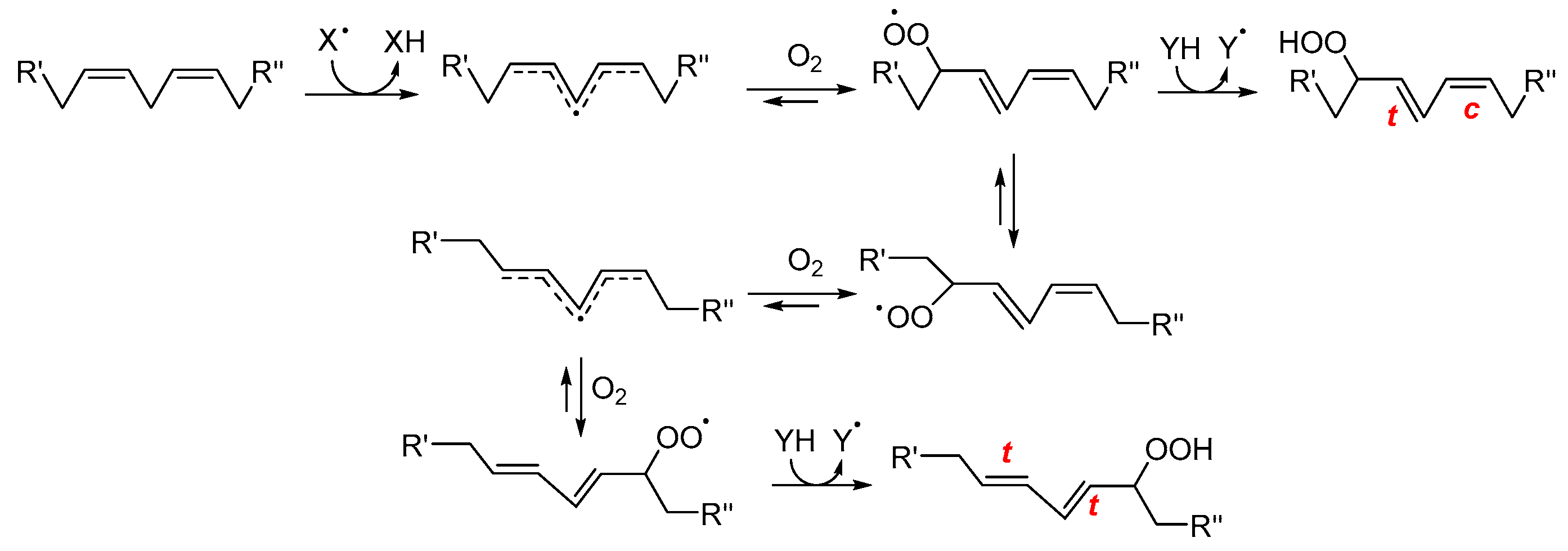

Early-stage products are predominantly hydroperoxides, especially in the case of PUFAs. For linoleate residues, the complete product distribution is well characterized (see Scheme 2). The double bond geometry (cis/trans) of the resulting hydroperoxides depends on how rapidly peroxyl radicals are intercepted by H-atom donors [26]. Consequently, during the autoxidation of triacylglycerols, trans–trans hydroperoxides typically dominate over cis–trans isomers. Interestingly, this ratio inverts in the presence of antioxidants, which favor the formation of cis–trans species by accelerating radical quenching. Hydroperoxides derived from polyunsaturated lipids also feature conjugated double bonds, enabling straightforward detection by UV–vis spectrophotometry [27]. The product distribution becomes more complex as the number of double bonds in the fatty acids increases. This is due to the fast cyclization reactions that may involve both peroxyl and alkyl radicals. In the case of substrates with one unsaturation, such as oleic acid and cholesterol, the H-atom abstraction by ROO• which yields hydroperoxides is in competition with ROO• addition to the double bond. Radical addition on non-conjugated double bonds typically generates epoxides and secondary alkoxyl radicals, RO• (see Scheme 1), which can rearrange to α-hydroxyl alkyl radicals. These latter, upon reaction with O2, yield ketones and HOO• radicals [28].

Scheme 2.

Simplified mechanism for the formation of early oxidation products from linoleate residues. R′ and R″ represent the two ends of linoleic acid. XH is a generic H-atom donor from which the radical X• is generated; c, t indicate cis and trans configurations, respectively. (adapted from Ref. [29]).

3.4.2. Late Products

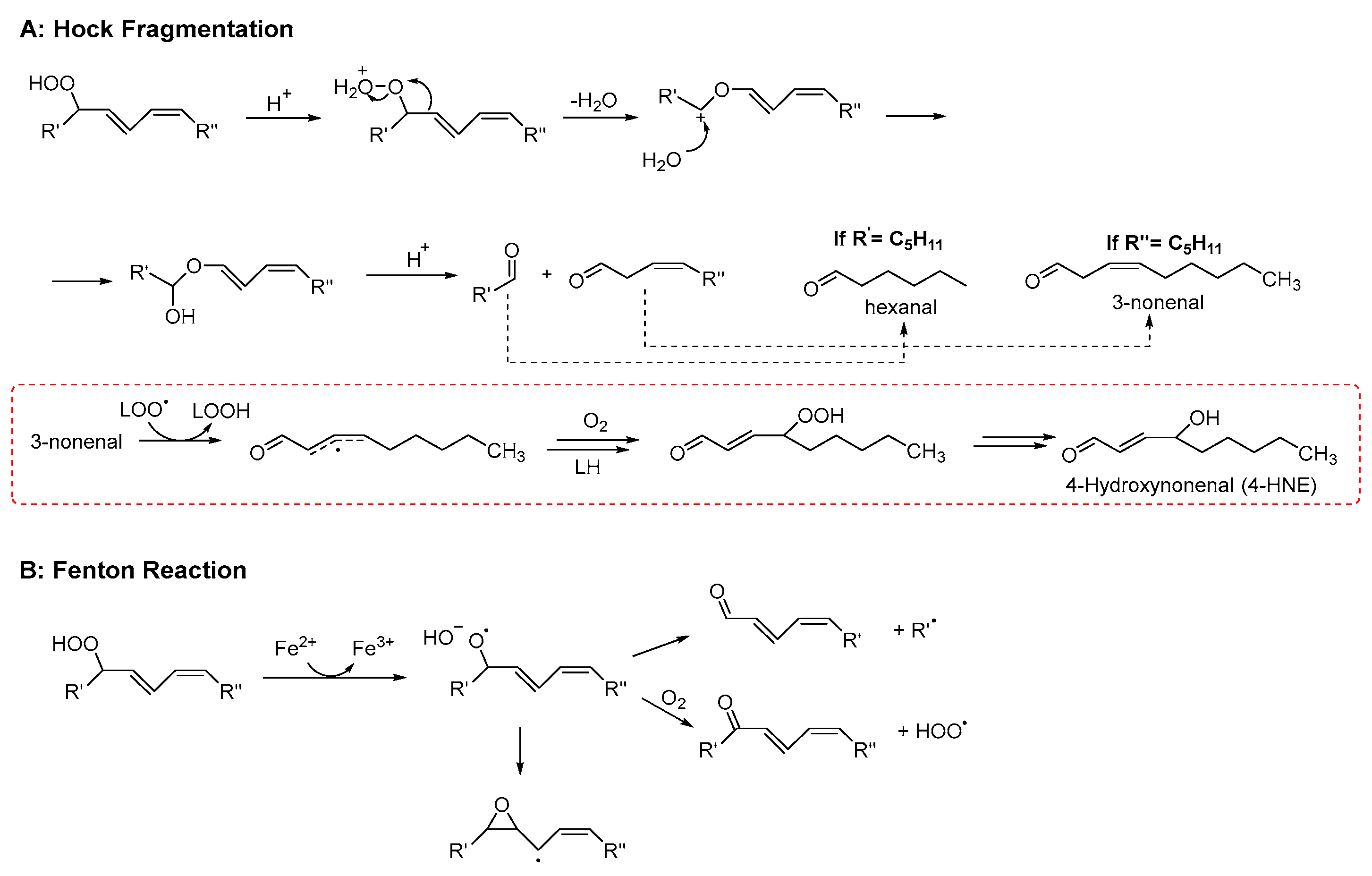

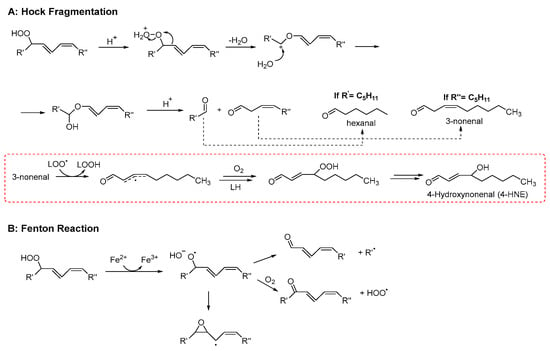

Late product formation from unstable hydroperoxides is promoted by homolytic or heterolytic reactions. The concentration of hydroperoxides increases at the beginning of the lipid peroxidation only. Afterwards, their concentration decreases because they convert into more stable secondary products, which accumulate over time [30]. In this regard, the oxidative stability of lipid materials is usually evaluated by measuring the content of both hydroperoxides and late products (typically volatile and non-volatile aldehydes) [31]. Although the reaction network leading to secondary products is very complex (for a comprehensive review see refs. [21,26]), two main pathways of hydroperoxide decay can be recognized: Hock fragmentation and radical homolysis. The latter decomposition process, triggered by reduced transition metals (such as Fe2+) or elevated temperatures, leads to the formation of alkoxyl radicals. The reaction mechanism may proceed via the generation of α-hydroxyalkyl radicals or, alternatively, through β-scission, producing alkyl radicals and aldehydes (see Scheme 3). This pathway is highly relevant for the initiation phase of lipid peroxidation, as trace amounts of both metals and hydroperoxides are invariably present in lipid-containing systems [32]. In addition to the above reactions, there is another process known as “Hock fragmentation” which is catalyzed by acids. This process, through a non-radical pathway, transforms a hydroperoxide into two aldehydes and is fundamental for the formation of oxylipins from cholesterol [21]. The nature of the aldehydes formed during lipid peroxidation depends critically upon the fatty acid being oxidized. It may include mono- and di-carbonyls with various degrees of unsaturation (like malondialdehyde or 4-hydroxynonenal, see Scheme 3). As expected, ω-3 fatty acids give aldehydes with a shorter chain (and a higher volatility) than ω-6 [33]. Hydroperoxides can also react with alkenes, forming epoxides, which in turn can be attacked by water or acids, forming diols or diesters, respectively [34]. Besides carbonyls and epoxides, other minor products that derive from advanced oxidation of aldehydes are also formed, like furans, aldol condensation products [33], and short-chain acids like acetic and formic acid, which are the main water-soluble volatiles that are detected by the Rancimat assay [35].

Scheme 3.

Examples of mechanisms leading to the formation of late products of lipid peroxidation (adapted from Ref. [36]).

4. Mechanistic Basis of the Antioxidant Activity

Antioxidants are molecules—or enzymatic systems—that, even at relatively low concentrations, can slow down or halt the peroxidation of an oxidizable substrate. Owing to their chemical diversity and distinct modes of action, they are commonly classified according to the stage of the peroxidation process at which they intervene.

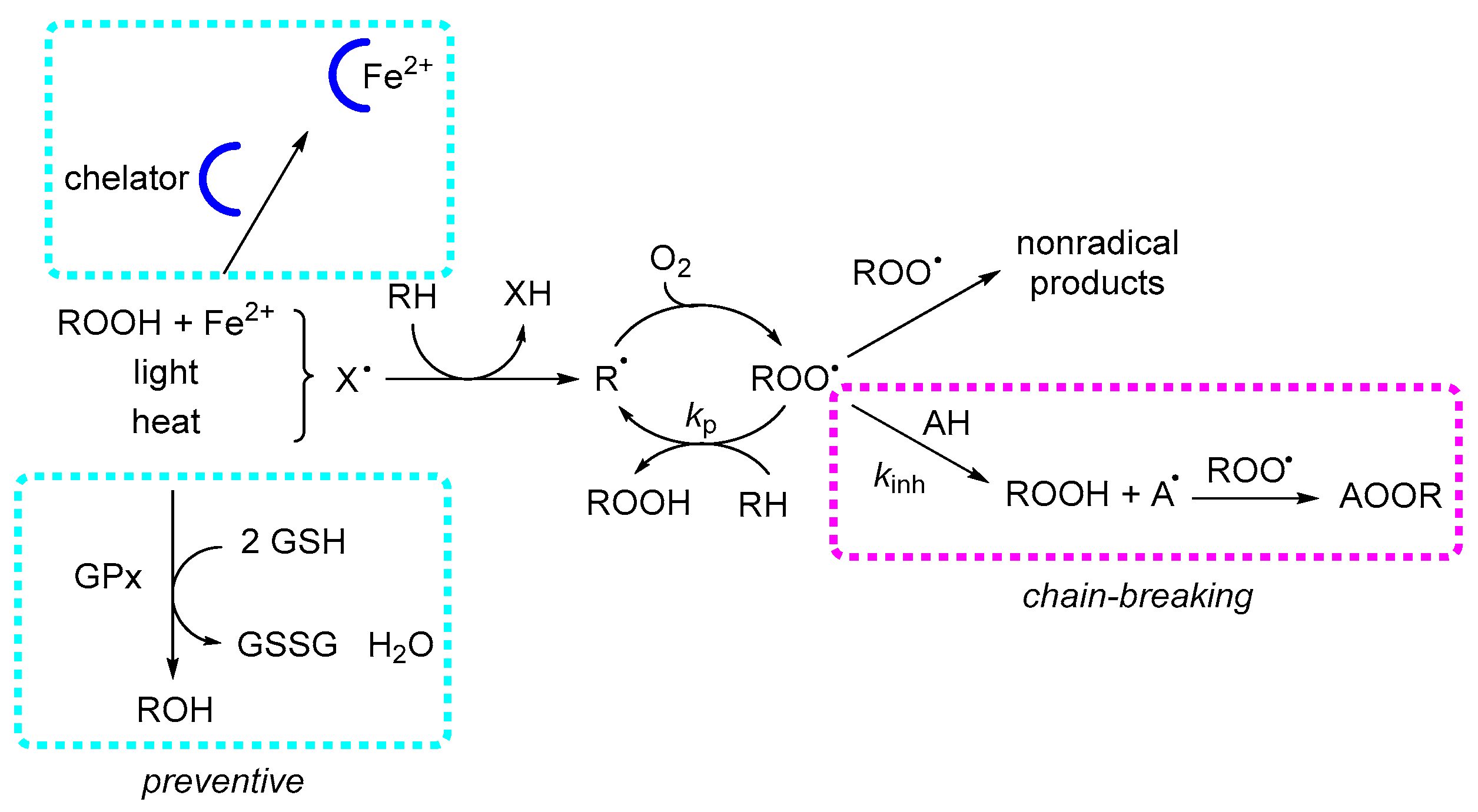

4.1. Preventive Mechanisms

Preventive antioxidants act at the initiation stage of lipid peroxidation by suppressing radical formation. In most systems, initiation is dominated by Fenton-type reactions, where reduced transition metal ions (Fe2+, Cu+) catalyze the homolytic cleavage of hydroperoxides, generating alkoxyl radicals. Consequently, the two main preventive strategies are peroxide decomposition and metal ion chelation. In biological systems, glutathione peroxidase (GPX) and catalase are the key enzymes responsible for peroxide reduction. In contrast, non-biological matrices contain very few examples of catalytic peroxide decomposition, mostly involving sulfur- or selenium-based systems [37]. Metal chelators, whether natural (e.g., phytic acid) or synthetic (e.g., ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, EDTA), exert their protective effect by stabilizing metal ions in a single redox state, thereby preventing redox cycling. In emulsified systems, chelators also operate by physically isolating metal ions from hydroperoxides, hindering catalytic contact. Effective chelating agents typically contain multiple polar or ionizable functional groups—such as phenoxides, carbonyls, carboxylates, or amines. Since EOs lack such functionalities, they are unlikely to display significant preventive activity through metal chelation.

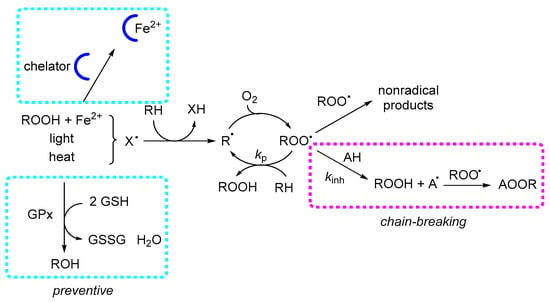

4.2. Chain-Breaking

Chain-breaking antioxidants, also referred to as radical-trapping antioxidants, function by quenching lipid ROO• (see Scheme 4). Most low-molecular-weight natural antioxidants, such as tocopherols, phenolic acids, and flavonoids, belong to this category, along with common synthetic additives like tert-butylhydroquinone (TBHQ), BHT, and propyl gallate. These compounds are consumed stoichiometrically during inhibition, meaning their protective effect is inherently limited by their initial concentration. Their efficiency can be significantly enhanced through regeneration mechanisms, particularly in biological membranes, where lipophilic antioxidants, such as α-tocopherol, localize within the hydrophobic core. There, they can be regenerated by hydrophilic reducing agents—most notably ascorbate, which is present in the cytosol at concentrations approaching 1 mM—allowing sustained antioxidant protection beyond their initial supply.20 Phenolic antioxidants, along with other radical-trapping antioxidants, inhibit lipid peroxidation by donating a hydrogen atom to the chain-carrying lipid ROO•, according to the reaction:

AH + ROO• → A• + ROOH

Scheme 4.

Mechanisms of antioxidant action in lipid peroxidation. Lipid peroxidation proceeds through the formation of R• and ROO•, which propagate by hydrogen abstraction from lipids (RH). Preventive antioxidants act prior to propagation, mainly by chelation of transition metals and enzymatic reduction in hydroperoxides (e.g., GPX). Chain-breaking antioxidants inhibit propagation by donating a hydrogen atom to ROO•, forming ROOH and a resonance-stabilized antioxidant radical (A•).

The efficiency of this reaction is expressed by its rate constant (kinh), which in apolar environments—such as biological membranes—can reach values as high as 104–107 M−1 s−1. For uninhibited peroxidation, the overall rate is described by:

where kp is the propagation rate constant, 2kt the termination rate constant, Ri the initiation rate, and finally [RH] the concentration of the substrate. In the presence of a chain-breaking inhibitor, the oxidation rate becomes:

where n is the stoichiometric factor, representing the number of ROO• radicals trapped per antioxidant molecule:

−d[O2]/dt = kp × Ri1/2[RH]/(2kt)1/2

−d[O2]/dt = kp × Ri × [RH]/(n kinh [inhibitor])

nROO• + Inhibitor → products

To summarize, the key requirements for an effective chain-breaking antioxidant (AH) are [38]:

- (1)

- Non-toxicity.

- (2)

- High reactivity toward lipid peroxyl radicals, i.e., a large inhibition rate constant (kinh).

- (3)

- Stability in air, under the reaction conditions, is extremely important because if AH reacted with O2 to give A• and HOO• (AH + O2 → A• + HOO•), it would behave as a pro-oxidant rather than an antioxidant.

- (4)

- Formation of a stable radical A• in the reaction AH + ROO• → A• + ROOH does not propagate the oxidative chain (A• + RH →AH + R•).

- (5)

- No reaction of A• with O2 (A• + O2 → AOO•), as this reaction would also propagate the chain reaction.

Molecular scaffolds satisfying most of these criteria include phenols, as well as certain enols (e.g., ascorbate, Maillard reaction products) [39] and some amines [40]. On the other hand, Rule 5 generally excludes that hydrocarbons can function as antioxidants since their carbon-centered radicals almost invariably react with O2 to give peroxyl radicals, see Scheme 1 and Scheme 3. However, notable exceptions exist—some of which are particularly relevant to the chemistry of EOs and will be discussed below.

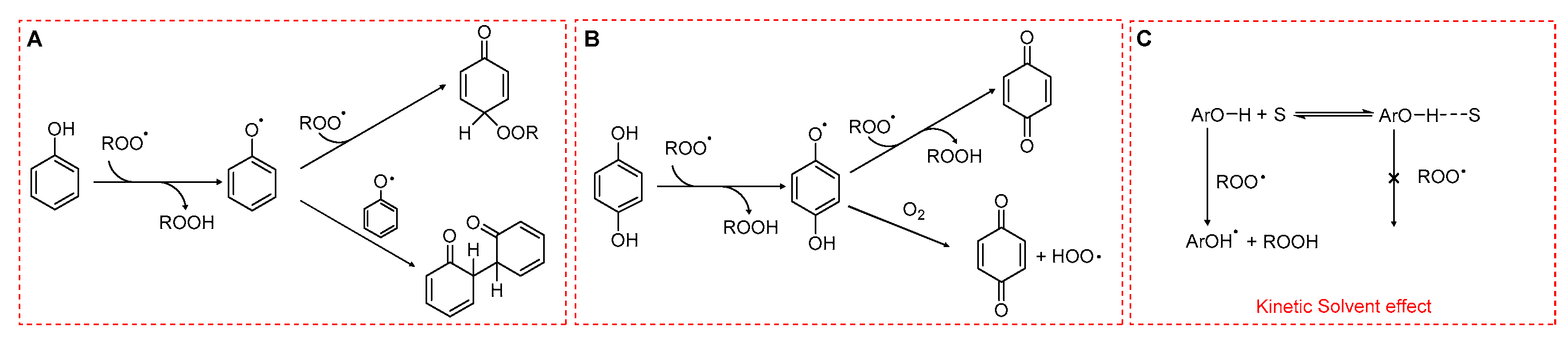

4.2.1. Phenolic Antioxidants

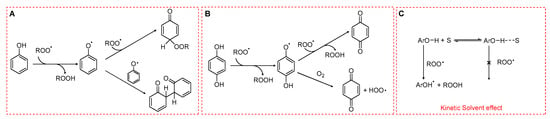

Phenols are among the most potent natural antioxidants. Their ability to slow down lipid peroxidation is due to the transfer of a hydrogen atom from the phenolic hydroxyl group (ArO–H) to a lipid ROO• through a formal hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5.

Radical-trapping mechanisms of phenols. (A) Monophenols. (B) Hydroquinones. (C) Hydrogen bonding between phenolic OH and the solvent reducing the reactivity toward peroxyl radicals.

The rate constant for this process, kinh, is determined by enthalpic factors (e.g., the bond dissociation enthalpy of the O–H bond), entropic factors (e.g., steric hindrance around the hydroxyl group), and solvent effects. In particular, hydrogen bonding between phenolic OH and solvent can markedly reduce the reactivity of phenols toward ROO•. In apolar media such as hydrocarbon solvents, phenolic antioxidants can display kinh values as high as 104–107 M−1 s−1 [41,42]. In contrast, in polar solvents and in water, the formation of an H-bond ArO-H···OH2 drastically reduces kinh as shown in Scheme 5C. This reduction is also caused by polar functional groups such as ester moieties in triglycerides or phosphate headgroups in phospholipids. Generally, the higher the polarity of the solvent or of the functional group, the lower the rate constant for HAT.

The fate of the phenoxyl radical is crucial (see Rule 4) in determining the overall efficiency of antioxidant protection. Simple monophenols are able to trap two peroxyl radicals (stoichiometric coefficient n = 2), unless radical–radical recombination occurs, in which case only one ROO• is neutralized per phenol (Scheme 5A). In contrast, hydroquinones bearing electron-donating substituents often display lower stoichiometric coefficients. This reduction arises because their semiquinone intermediates can react with O2, generating HOO•, which in turn may sustain the oxidative chain (Scheme 5B).

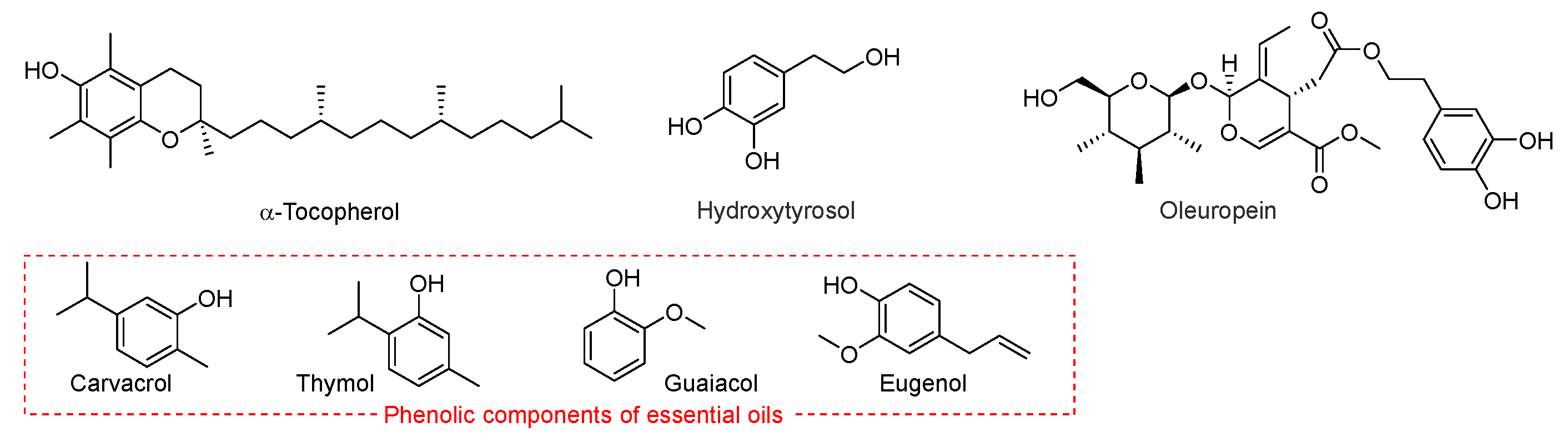

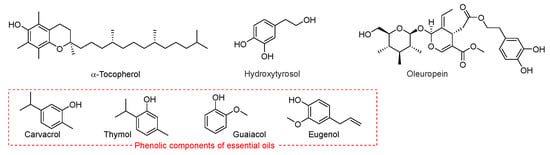

Many natural lipids contain significant quantities of phenolic antioxidants. For instance, seed oils typically have high levels of tocopherols or tocotrienols, whereas olive oil contains polyphenols such as oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol. Among EO antioxidant components, phenols such as carvacrol, thymol, eugenol, guaiacol and methylphenols (Scheme 6) behave as radical trapping antioxidants, although with a much smaller kinh than α-tocopherol [43].

Scheme 6.

Representative phenolic chain-breaking antioxidants, including α-tocopherol, hydroxytyrosol, oleuropein, carvacrol, thymol, guaiacol, and eugenol.

4.2.2. γ-Terpinene as Antioxidant

While the antioxidant properties of phenols are well established, the ability of certain non-phenolic molecules belonging to the terpene family and able to retard lipid peroxidation has received much less attention. A notable example is γ-terpinene, which, despite being highly oxidizable and requiring careful storage, exhibits significant antioxidant activity. Its mode of action has been described as “termination enhancement”, owing to its ability to accelerate the termination of peroxyl radicals, see Scheme 1.

Under normal conditions, ROO• radicals decay via the self-reaction:

which, for secondary or primary alkyl peroxyls (R2CHOO• or RCH2OO•), decomposes to yield singlet oxygen (1O2) and disproportionation products. Termination can be accelerated by the hydroperoxyl radicals (HOO•) which leads to the following cross-reaction:

ROO• + ROO• → ROOOOR

HOO• + ROO• → ROOH + O2

Generally, this reaction proceeds faster than ROO• self-reaction. This cross-termination lowers the steady-state concentration of ROO• and thereby decreases the rate of peroxidation (–d[O2]/dt).

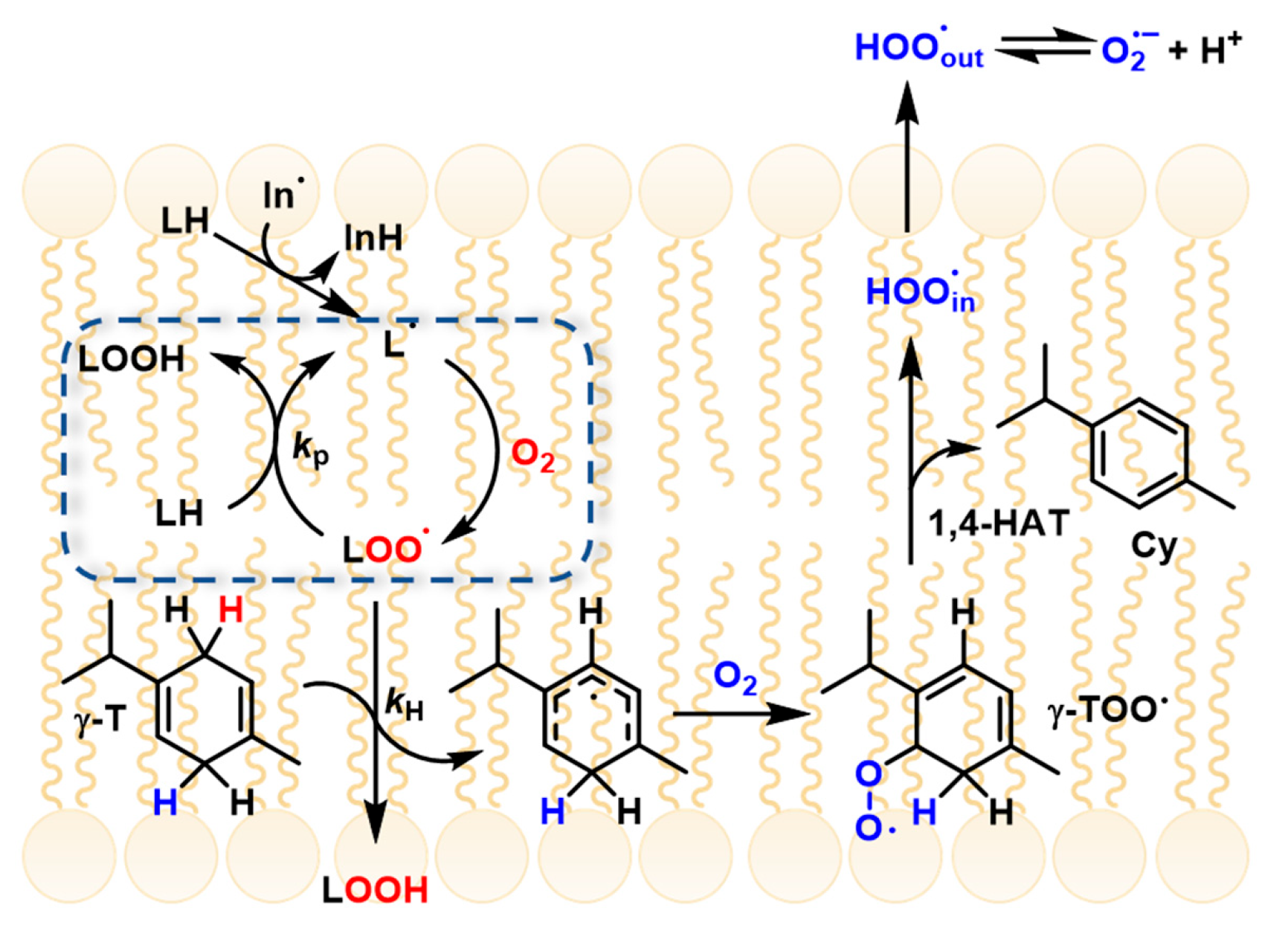

γ-Terpinene reacts with lipid peroxyl radicals (ROO•) to generate an unstable γ-terpinyl peroxyl intermediate, which rapidly decomposes to yield hydroperoxyl radicals (HOO•) and p-cymene. Although HOO• is, in principle, capable of propagating lipid peroxidation, in this system its predominant role is to promote ROO•–ROO• termination, thereby reducing the overall rate of substrate (RH) oxidation. This mechanism accounts for the marked retardation of linoleic acid peroxidation observed when γ-terpinene is present at millimolar concentrations in organic solution [44,45,46].

A similar effect is also observed in the oxidation of slow-reacting substrates such as isopropylbenzene (cumene), which forms tertiary ROO• radicals characterized by small self-termination rate constants (kt ≈ 104 M−1 s−1). In such cases, the peroxidation process is slowed down by EO components that generate secondary ROO• radicals—such as linalool, limonene, or citral—which have significantly higher termination rate constants [47].

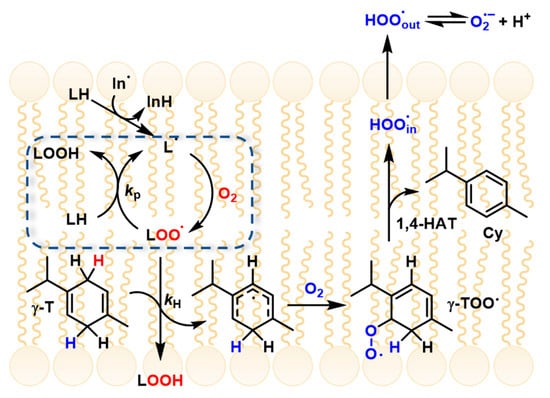

γ-Terpinene has recently been shown to suppress lipid peroxidation in micelles and liposomes through a novel “radical-exporting” mechanism. In these biphasic environments, PUFA oxidation occurs within the lipophilic core of micelles or lipid bilayers, where lipid peroxyl radicals (ROO•) propagate the reaction efficiently. Upon addition of γ-terpinene, ROO• radicals in the lipid phase are rapidly quenched, generating HOO• radicals (as discussed above). Due to their small size and high polarity, HOO• radicals diffuse out of the lipid compartment into the aqueous phase, thereby interrupting radical propagation within the lipid domain. This process has been described as a “slingshot” or “radical-exporting” mechanism, as the newly formed HOO• radicals are effectively expelled from the lipid environment, preventing further chain propagation where it is most efficient (Figure 2) [10].

Figure 2.

γ-terpinene mechanism and radical exporting (from Ref. [10]).

5. Chemical Methods

Inhibited autoxidation methods are considered the gold standard for assessing antioxidant activity, as they measure a compound’s ability to protect a substrate from oxidation. The rate of autoxidation is monitored in the presence or absence of antioxidants using parameters such as oxygen consumption (oximetry), hydroperoxide formation, or substrate depletion. When EOs are investigated using kinetic assays, the intrinsic instability of their constituents must be considered, as storage-induced autoxidation and secondary oxygenation can alter their chemical composition [48]. Monoterpene hydrocarbons, for instance, are particularly prone to forming hydroperoxides and other oxidized derivatives, which often display reactivities distinct from those of the parent compounds [2]. Such transformations can bias the apparent inhibitory efficiency determined in autoxidation assays and complicate the interpretation of antioxidant mechanisms. Periodic verification of EO composition prior to kinetic evaluation is therefore essential to ensure that the measured activity reflects the native chemical profile rather than storage-related artifacts.

5.1. Oximetry

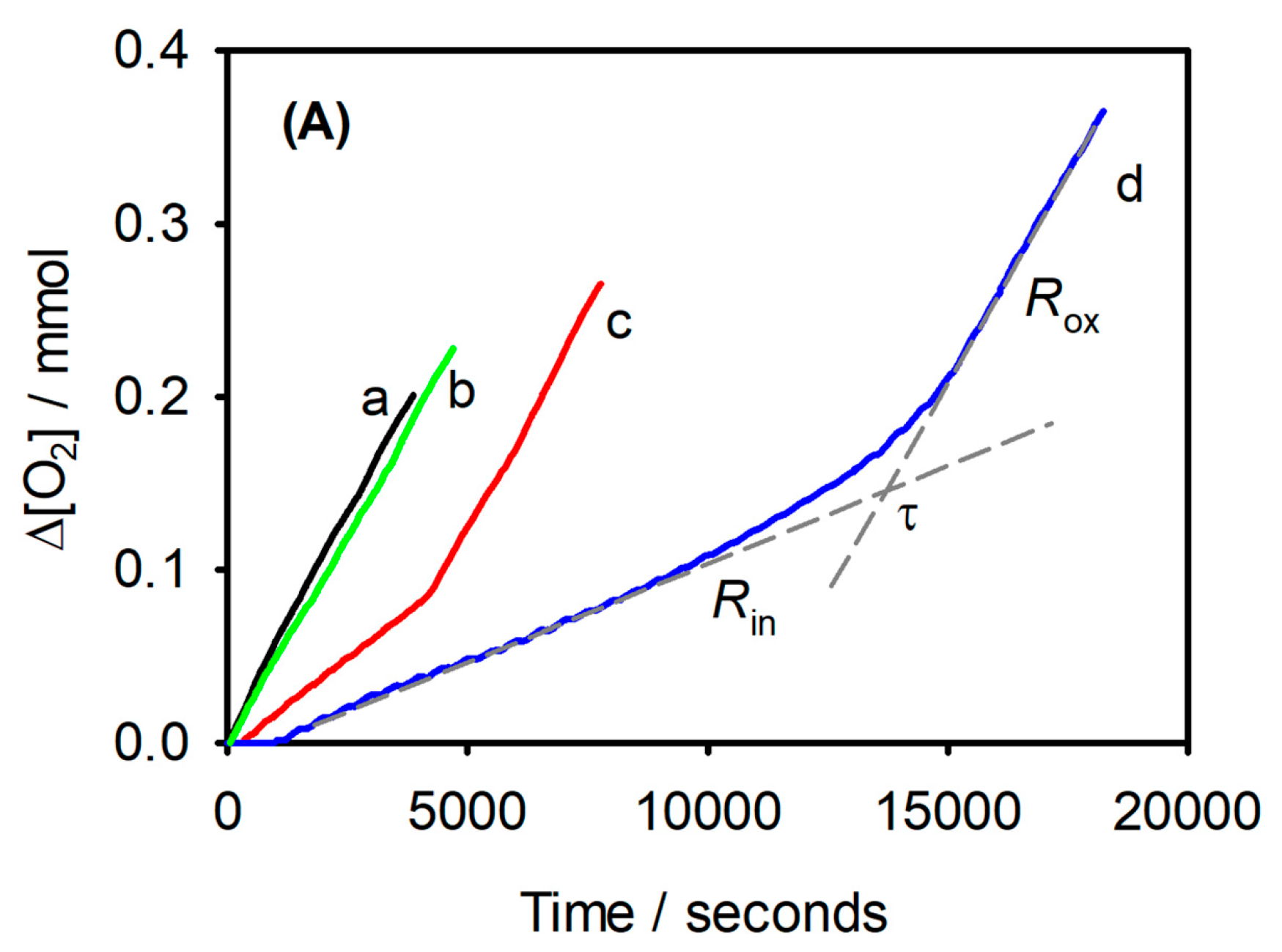

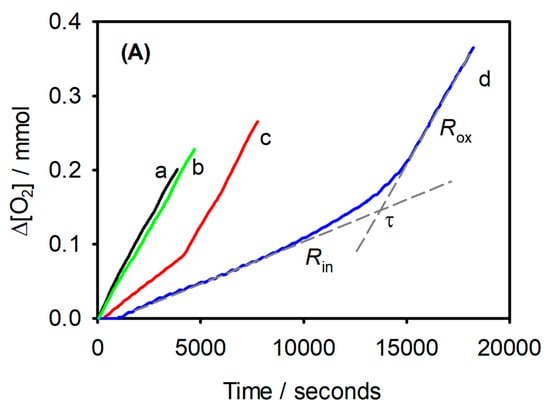

Oximetry offers a direct and continuous measure of peroxidation by tracking O2 consumption, typically inferred from the pressure drop in a closed vessel. It is essential to ensure that O2 is the only reactive gas during the experiment [43]. Direct measurement can also be achieved using a Clark electrode [49] or an optical sensor based on fluorescence quenching, which is particularly suitable for lipids dispersed in water [10,22]. A representative oximetry trace is shown in Figure 3, illustrating the inhibition period induced by antioxidants. The primary advantage of this technique is that it monitors peroxidation kinetics in real-time without the need for sampling, providing a clear and continuous assessment of antioxidant efficacy.

Figure 3.

Synergic effects of a-tocopherol and γ-terpinene measured by oximetry. Oxygen consumption during the oxidation of stripped sunflower oil (SSO, 2 g) at 130 °C: without any additive (a), with γ-terpinene (1%, w/w) (b); with α-tocopherol (0.1%, w/w) (c); with α-tocopherol (0.1%, w/w) and γ-terpinene (1%, w/w) (d). Rin and Rox represent the rates of O2 consumption in the inhibited and non-inhibited period, respectively, while τ is the duration of the inhibited period. (from Ref. [50]).

5.2. Hydroperoxides

Hydroperoxides (ROOH) formation is a commonly used parameter to monitor lipid peroxidation, as ROOH are the primary products of radical attack on unsaturated lipids. They can be detected through their redox reactivity, for example, using the Fe2+–thiocyanate assay, which relies on the oxidation of Fe2+ by hydroperoxides. Alternatively, hydroperoxides can be identified via their characteristic spectroscopic signatures, such as FT-IR absorbance of the OO-H stretch or 1H-NMR signals of the hydroperoxide proton. A popular way to measure the formation of hydroperoxides in samples containing polyunsaturated lipids is to determine conjugated dienes (CD). For example, linoleic acid contains two non-conjugated double bonds at positions 9 and 12. The peroxidation of this substrate, as for other PUFAs with multiple non-conjugated double bonds, produces CD hydroperoxides as primary oxidation products, see Scheme 1 [51]. These compounds have a strong absorption band at 234 nm with large molar extinction coefficients that are slightly dependent on the solvent, as the values are 25,500 M−1cm−1 in cyclohexane, 29,100 M−1cm−1 in acetonitrile and 30,500 M−1cm−1 in tert-butanol [52]. The extent of oxidation can be evaluated by following the formation of CD over time, VCD = dA234/edt, where VCD is the rate of CD formation, A234 the absorbance at 234 nm and e the extinction coefficients at 234 nm.

Other techniques used to study inhibited lipid peroxidation include isothermal calorimetry [53,54], which measures the heat released during the propagation phase, and the quantification of volatile products deriving from hydroperoxide decomposition such as hexanal using GC–MS [55,56]. Recent developments aimed at increasing throughput involve the use of oxidizable fluorescent probes, which co-oxidize with the substrate and allow peroxidation to be monitored in multiwell plate readers [57].

5.3. Aqueous Versus Lipid-Phase Antioxidant Assays

The oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) assay is performed in an aqueous buffered system and evaluates antioxidant protection against ROO•–mediated oxidation, primarily reflecting antioxidant activity in water-phase biological environments such as the cytosol or plasma [58]. In its classical format, the fluorescent probe (typically fluorescein) is a freely diffusing, water-soluble molecule, and oxidation occurs in a homogeneous aqueous phase, limiting the relevance of ORAC for lipid peroxidation processes taking place in membranes or lipid-rich microenvironments [59].

To partially address this limitation, Varandas et al. introduced a liposome-adapted ORAC format in which the fluorophore was covalently anchored to a phospholipid (POPE–COUM) and incorporated into lipid bilayers [60]. This configuration spatially confines oxidative events to the membrane or interfacial region, providing a more biomimetic context than classical ORAC. However, the system still relies on ROO•/RO• radicals generated by thermal decomposition of AAPH in the aqueous phase and does not involve intrinsic lipid autoxidation [61]. Accordingly, such approaches should be regarded as modified ORAC rather than genuine lipid autoxidation models.

Overall, ORAC and its variants offer useful reference information for antioxidant screening in aqueous or membrane-associated settings, but they may not adequately capture the kinetic features of lipid radical chain propagation that dominate the antioxidant behavior of lipophilic EO constituents. In contrast, fluorescence-enabled inhibited autoxidation (FENIX) is directly grounded in the mechanism of lipid peroxidation because the fluorescent probe is lipophilic, is co-oxidized with lipids being able to transfer the radical chain. By monitoring antioxidant interference with the radical propagation phase in controlled autoxidation systems, FENIX enables quantitative determination of radical-trapping rate constants and inhibition efficiencies [62]. Because lipid peroxidation itself serves as the reaction driver, FENIX more faithfully reflects oxidation kinetics in lipid phases and membrane environments.

Consistent with this mechanistic basis, FENIX has been increasingly applied to the study of membrane-associated antioxidant defense, particularly in ferroptosis research, where it provides quantitative insight into the suppression of phospholipid peroxidation [63,64]. For EO components whose biological effects are closely linked to membrane lipid peroxidation, FENIX therefore offers higher mechanistic relevance and predictive value than conventional aqueous antioxidant capacity assays.

5.4. Deprecated Methods

Many researchers commonly rely on DPPH (2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl), ABTS (2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)), and FRAP (Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power) assays to assess antioxidant activity. However, these radicals differ chemically and mechanistically from the lipid ROO• that propagate lipid peroxidation. For instance, some of these model radicals exhibit enhanced reactivity in polar solvents, while ROO• radicals do not. Moreover, the common practice of measuring absorbance at a fixed time can mask kinetic differences, effectively equating the activity of “fast” antioxidants with that of “slow” ones, and potentially leading to misleading conclusions about their true efficacy in lipid systems [65].

DPPH is an excellent electron acceptor, and this differentiates it from peroxyl radicals, which are more active in HAT. Therefore, compounds that deprotonate to give their conjugated base can react very quickly with DPPH by electron transfer from the anion by the sequential proton-loss electron transfer (SPLET) mechanism. Furthermore, the use of DPPH under non-kinetic conditions with the aim of determining its consumption at fixed times may overestimate the antioxidant capacity of a compound. Overall, the DPPH assay gives the scavenging activity or the reducing capacity of a compound, but it does not provide an appropriate measurement of the antioxidant activity. However, it is important to note that, despite the limitations of the DPPH assay, it can be useful for studying structure-activity relationships among antioxidants and for titrating the content of antioxidants in crude extracts, provided that the reaction time is short to minimize errors.

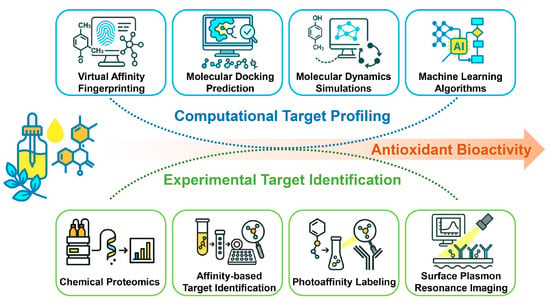

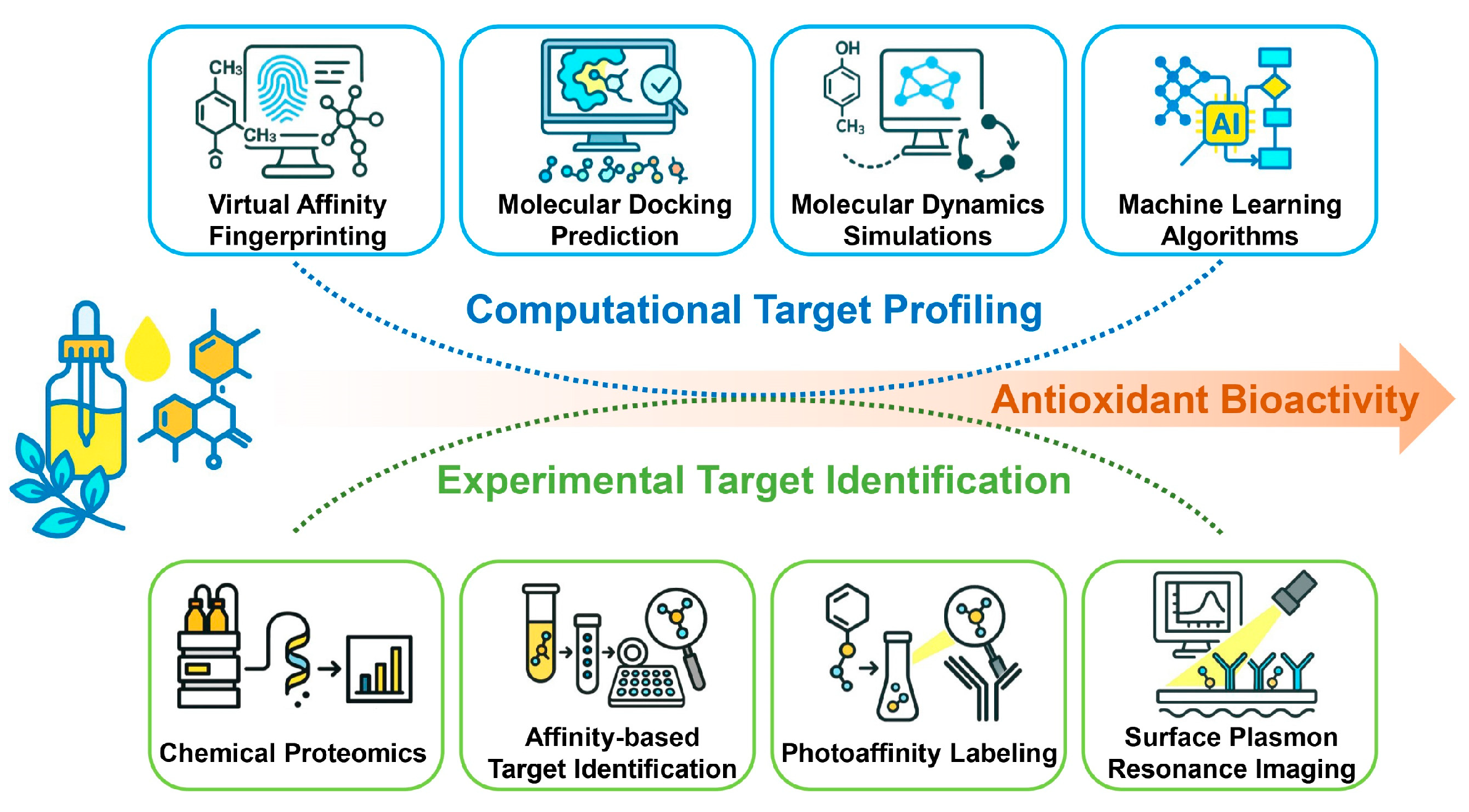

6. Biological Methods and Mechanistic Evaluation System

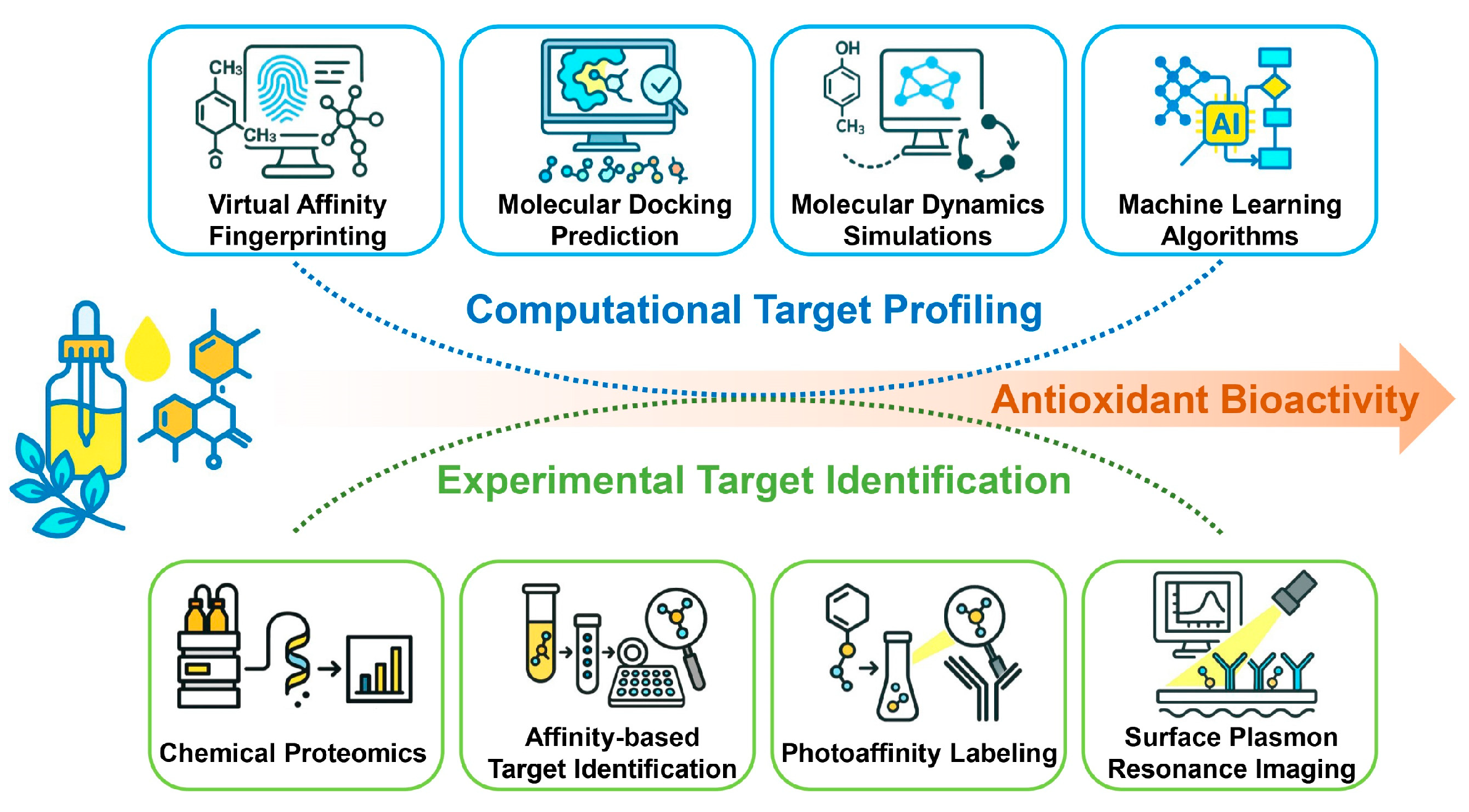

A comprehensive investigation of the antioxidant activities of EOs requires the systematic mapping of the molecular networks and signaling pathways through which they exert their protective effects. Moving beyond classic in vitro assays, contemporary research adopts a multidimensional framework that combines biochemical, cellular, and in vivo analyses with cutting-edge high-throughput screening, target-specific profiling, and molecular interaction platforms to enable a comprehensive evaluation of antioxidant capacity.

6.1. Detection and Quantification of Oxidative Mediators and Byproducts

6.1.1. Fluorescent and Chemiluminescent Probes for Reactive Species

Intracellular levels of free radicals, nitric oxide, and hydrogen peroxide are established markers of oxidative stress and are routinely measured to assess the antioxidant capacity of EOs. Recent methodological advances have led to the development of a diverse array of cell-permeable fluorescent probes, each with selectivity for distinct reactive oxygen or nitrogen species, enabling sensitive and dynamic monitoring within biological systems. Table 1 summarizes the probes used in studies on EOs and compounds.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cells arise from multiple biochemical processes, among which electron leakage from the mitochondrial respiratory chain constitutes a major endogenous source under both physiological and pathological conditions. Additional contributions originate from enzymatic systems, including NADPH oxidases, xanthine oxidase, and uncoupled nitric oxide synthase, as well as from peroxisomal metabolism and inflammation-associated reactions [66]. Because individual ROS differ markedly in reactivity, lifetime, and subcellular localisation, their accurate assessment requires probes with appropriate selectivity and compartmental resolution, and no single probe can adequately represent the overall cellular redox state [67].

For general ROS measurement, DCFH-DA is frequently employed [68]. MitoSOX™ Red and MitoTracker® Red CM-H2XRos are commonly used for mitochondrial ROS detection [69,70]. While dihydroethidium (DHE) and MitoSOX™ Red are widely applied for superoxide detection, their selectivity remains a matter of debate due to possible oxidation by other reactive species. Likewise, Amplex® Red and peroxy-orange 1 (PO1) are employed for hydrogen peroxide measurement, though the assay depends on the formation of radical intermediates via peroxidase-mediated reactions [71,72]. 4-hydroxyphenyl fluorescein (HPF) and 2-[6-(4′-amino)phenoxy-3H-xanthen-3-on-9-yl]benzoic acid (APF) are utilized for hydroxyl radicals [73]. DAF-FM DA (i.e., 4-amino-5-methylamino-2′,7′-difluorofluorescein diacetate) is specific for nitric oxide [74], and Dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR123) is applied for peroxynitrite (ONOO−) [75]. C11-BODIPY 581/591 is widely adopted for monitoring lipid peroxidation [76]. Genetically encoded biosensors, such as the fluorescent protein–based probe HyPer, enable real-time monitoring of hydrogen peroxide in living cells and allow dynamic, compartment-specific tracking of its fluctuations [77].

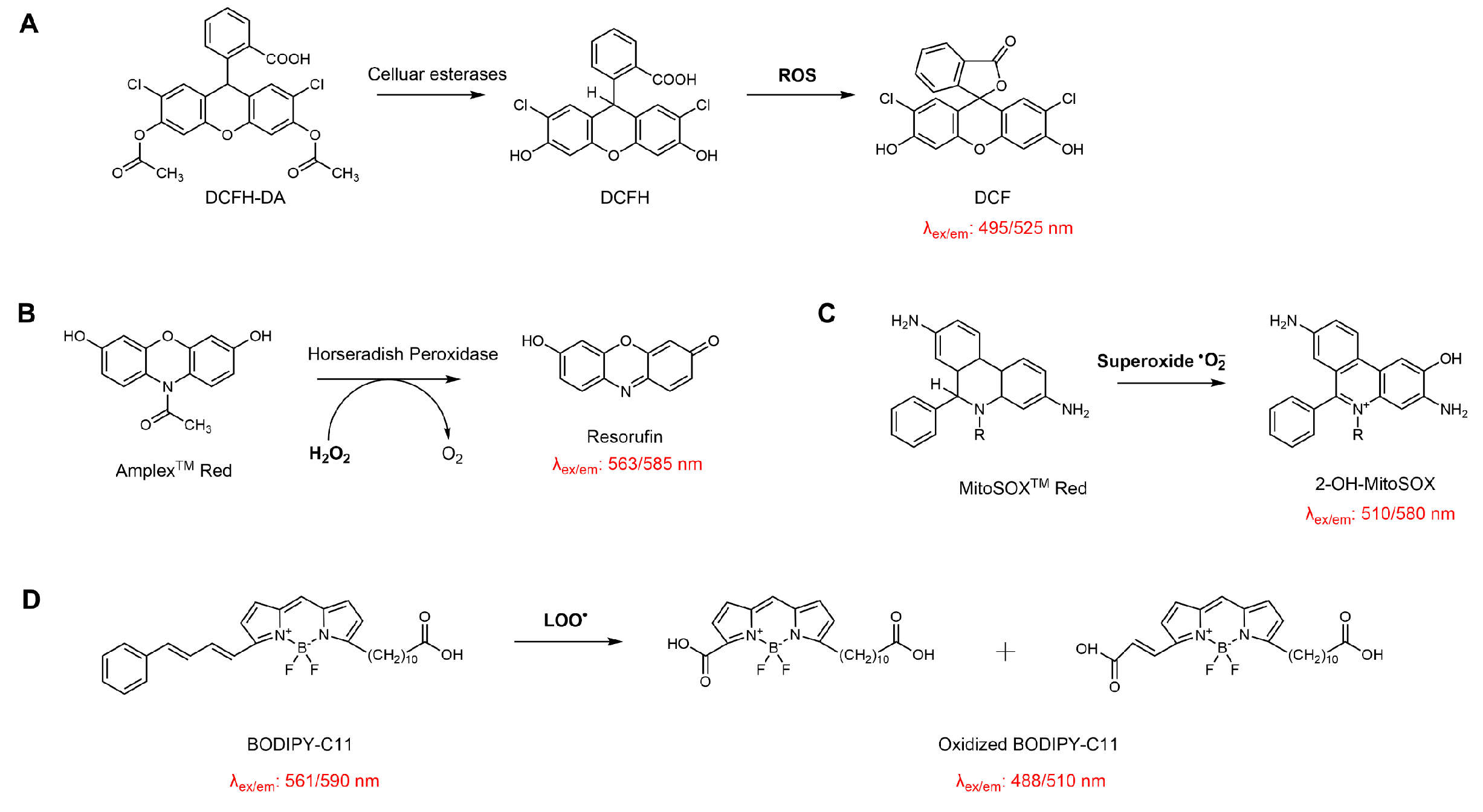

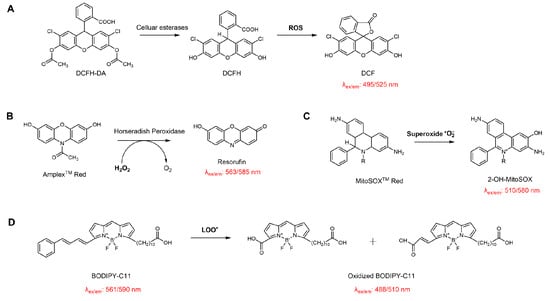

While these tools have significantly advanced the resolution and specificity of redox monitoring (Scheme 7), each probe has inherent limitations regarding selectivity, photostability, or susceptibility to artifacts. Careful experimental validation is therefore required for a reliable data interpretation.

Table 1.

Fluorescent probes are used in EO studies for detecting free radicals and oxidants in biochemical assays.

Table 1.

Fluorescent probes are used in EO studies for detecting free radicals and oxidants in biochemical assays.

| Probes | Target Species | EOs/Compounds | Antioxidant Effects | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCFH-DA | Intracellular total ROS | Lavender EO | Significantly reduced intracellular ROS levels in H2O2-treated PC12 cells | [78] |

| DHE | Superoxide (O2•−) (mainly cytosolic) | Citronella and Nutmeg EOs | Significantly reduced ROS levels in the ankle joints of monosodium urate-induced gouty arthritis mice | [79] |

| MitoSOX Red | Mitochondrial superoxide (O2•−) | Lippia alba EO | Significantly decreased mitochondrial superoxide levels in J774A.1 murine macrophage | [80] |

| Amplex™ Red | Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) | Citrus aurantifolia EO | Significantly reduced H2O2 levels in dystrophic muscle cells | [81] |

| C11-BODIPY 581/591 | Lipid peroxides | γ-Terpinene | Effectively inhibits lipid peroxidation and protects SH-SY5Y cells from RSL3-induced ferroptosis | [10] |

| HPF/HPF-DA | Hydroxyl radicals (•OH) | Pomelo peel EO | Significantly attenuated ·OH and overall ROS accumulation in both in vivo and in vitro models of cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury | [82] |

| DAF-FM DA | Nitric oxide (NO) | Carvacrol | Significantly increased NO levels in rat cavernous endothelial cells under D-(+)-galactose-induced premature senescence | [83] |

Scheme 7.

Schematic illustration of the reaction principles of common probes used for evaluating the antioxidant activity of EOs in cellular systems. (A) DCFH-DA for detecting intracellular total ROS; (B) Amplex™ Red for quantifying hydrogen peroxide in the presence of horseradish peroxidase; (C) MitoSOX™ Red for mitochondrial superoxide detection; (D) BODIPY-C11 for monitoring lipid membrane peroxidation.

6.1.2. Metabolic and Oxidative Byproduct Quantification

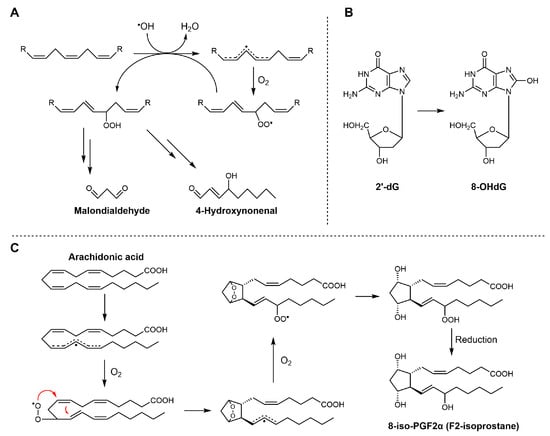

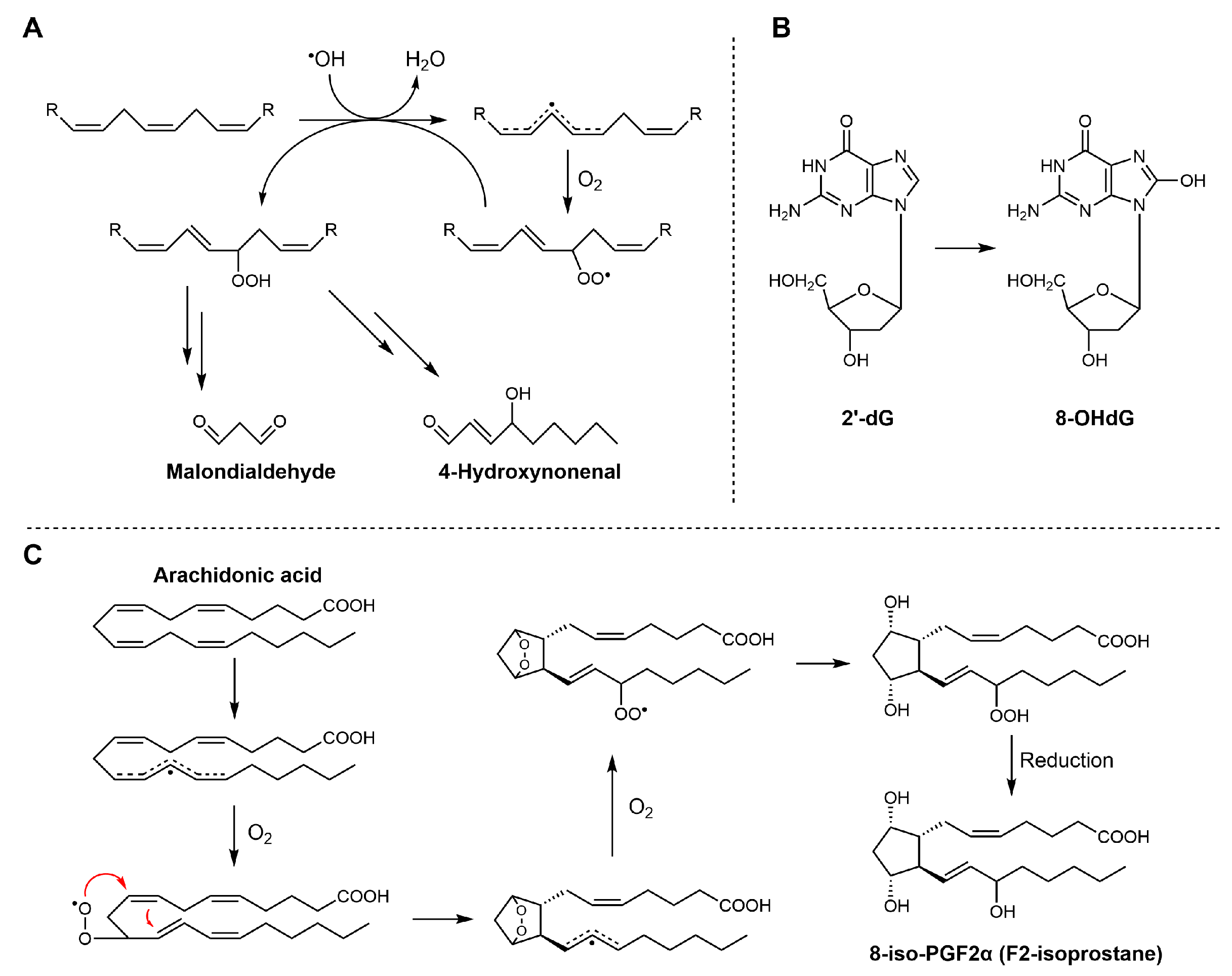

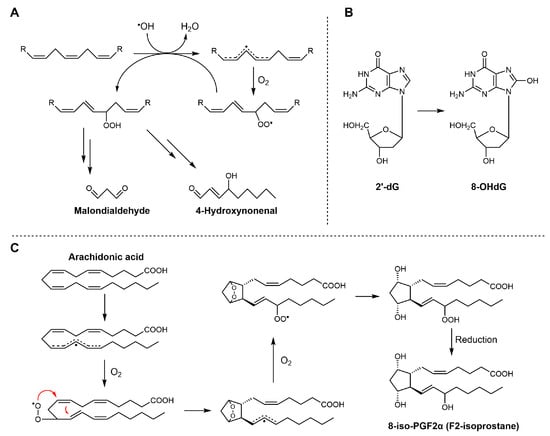

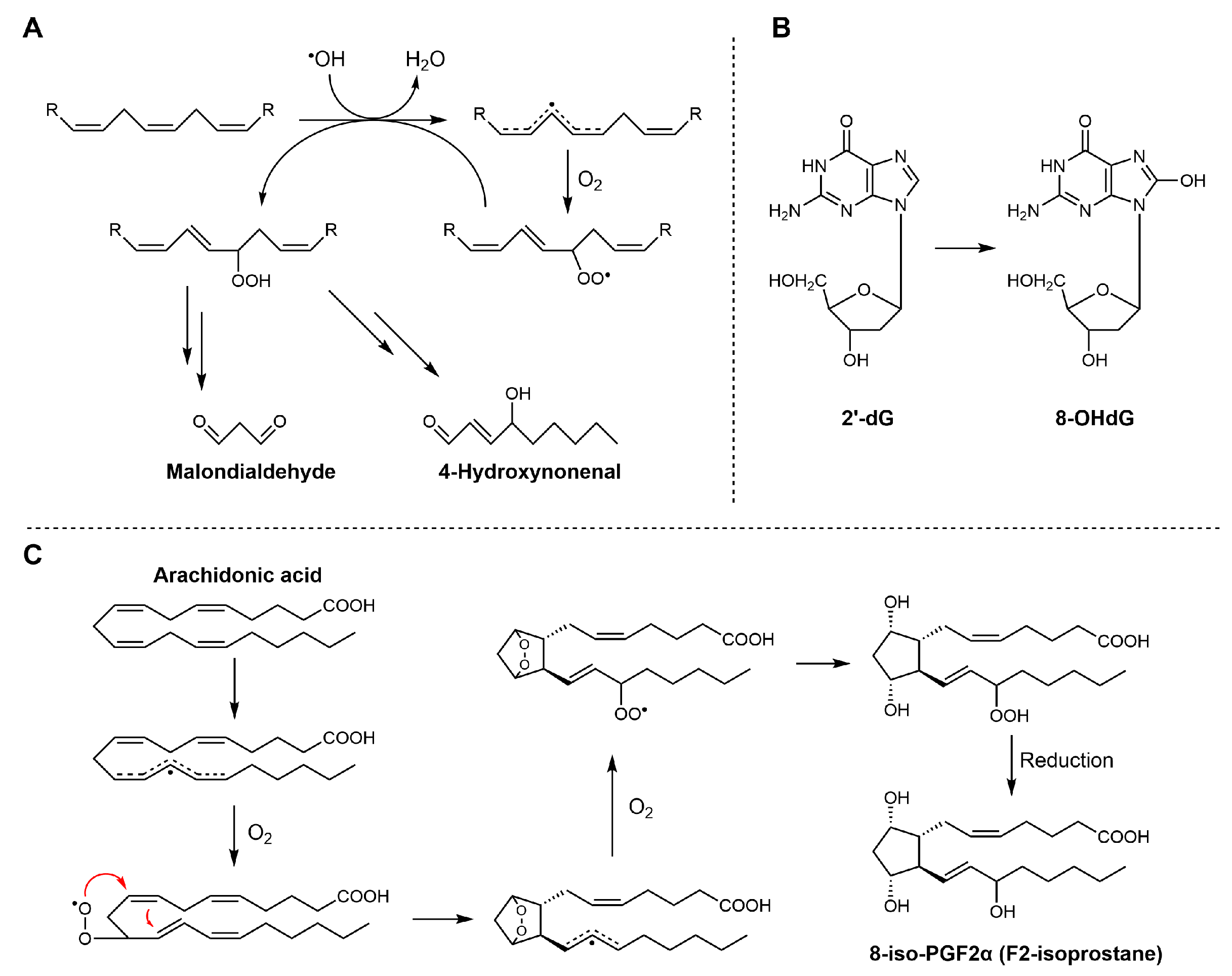

The overproduction of reactive species ultimately leads to the formation of a range of metabolic and oxidative byproducts, which serve as important biomarkers of oxidative stress. A thorough understanding of oxidative stress and antioxidant intervention relies on accurate measurement of metabolic and oxidative byproducts within biological systems. For example, the accumulation of lipid peroxidation end-products such as malondialdehyde (MDA), 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), and F2-isoprostanes has been used as a direct indicator of membrane oxidative damage (see Scheme 8) [84]. Quantification of these markers, along with protein carbonyls and oxidized nucleotides like 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG), has advanced significantly with the adoption of analytical platforms such as LC-MS/MS and HPLC-FLD [85]. These techniques offer substantial improvements in selectivity and sensitivity compared to classical spectrophotometric or colorimetric assays, and they help reduce the background interference that often complicates measurements in complex biological samples. As shown in Table 2, studies evaluating oxidative byproducts with a focus on essential oils and their constituent compounds are summarized.

Scheme 8.

Biosynthetic pathways of MDA, 4-HNE, 8-OHdG, and F2-isoprostanes. (A) MDA and 4-HNE are generated from the peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs); (B) 8-OHdG is formed through oxidative modification of deoxyguanosine residues in DNA under conditions of oxidative stress; (C) 8-iso-PGF2α is produced from arachidonic acid via free radical-catalyzed lipid peroxidation.

Scheme 8.

Biosynthetic pathways of MDA, 4-HNE, 8-OHdG, and F2-isoprostanes. (A) MDA and 4-HNE are generated from the peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs); (B) 8-OHdG is formed through oxidative modification of deoxyguanosine residues in DNA under conditions of oxidative stress; (C) 8-iso-PGF2α is produced from arachidonic acid via free radical-catalyzed lipid peroxidation.

However, the selection of biomarkers and analytical methods has some limitations. For example, the quantification of MDA using the conventional thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay often results in an overestimation of oxidative damage, primarily due to insufficient specificity [86]. In this assay, a range of reactive carbonyl species, some of which are not derived from lipid peroxidation, can react with thiobarbituric acid, thereby contributing to the final signal. In addition, the sensitivity of the absorbance-based TBARS assay is relatively low, with a detection limit of about 1.1 μM. The results are highly subject to variations in experimental procedures and pre-analytical sample handling. Small changes in storage temperature or sample preparation can significantly influence the outcome, making the assay poorly reproducible and unsuitable for direct comparisons between laboratories [87]. On the other hand, mass spectrometry-based methods provide superior accuracy and specificity in the quantification of oxidative markers. However, these approaches require more extensive sample preparation and access to advanced instrumentation [88].

In contrast, measuring 4-HNE and F2-isoprostanes is considered more suitable for assessing lipid peroxidation. Both molecules are generated almost exclusively through free radical-mediated oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids. Specifically, 4-HNE mainly arises from the peroxidation of n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids.

F2-Isoprostanes, formed via non-enzymatic free radical oxidation of arachidonic acid, are widely regarded as the “gold standard” biomarkers of in vivo lipid peroxidation, due to their strong association with oxidative damage and various diseases. The compound 8-OHdG (see Scheme 6), often produced in parallel with lipid peroxidation, is widely used as a biomarker of oxidative DNA damage. It reflects oxidative modifications of nucleic acids induced by hydroxyl radicals (•OH). Quantification of these biomarkers is usually performed using high-performance liquid chromatography techniques, which enable precise discrimination of structural isomers and minimize interference from unrelated compounds. However, these biomarkers are typically present at low concentrations, and their measured levels can be influenced by sample handling and storage conditions prior to analysis.

Table 2.

EO studies involving metabolic oxidative biomarkers and evaluation methods.

Table 2.

EO studies involving metabolic oxidative biomarkers and evaluation methods.

| Eos | Model | Oxidative Biomarker | Method | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mentha piperita | CCl4-induced hepatic oxidative damage and renal failure in rats | Liver MDA | Thiobarbituric acid assay | [89] |

| Lavandula stoechas | Alloxan-induced diabetic rats | Liver and kidney MDA | Thiobarbituric acid assay | [90,91] |

| Rosmarinus officinalis | CCl4-induced acute liver damage in rats | Liver MDA | Thiobarbituric acid assay | [92] |

| Origanum vulgare | Day-old chickens for 38 days | Breast and thigh muscle MDA | Thiobarbituric acid assay | [93] |

| Citrus aurantifolia | Dystrophic muscle cells | 4-HNE-protein adducts | Western blot | [81] |

| Lavandula angustifolia | The human glioblastoma U87MG cell line | 4-HNE | Immunofluorescence | [94] |

| Melaleuca alternifolia | Macrobrachium rosenbergii | 4-HNE | ELISA | [95] |

| Ocimum basilicum, Galium odoratum, Cymbopogon citratus | Human lymphocytes | 8-OHdG | ELISA assay | [96] |

| Origanum vulgare | IFN-γ and histamine-induced inflammatory model in human keratinocytes (NCTC 2544) | 8-OHdG | Immunofluorescence | [97] |

| Thymus vulgaris | Heat stress and dietary supplementation model in laying hens | 8-OHdG | ELISA assay | [98] |

| Origanum vulgare | Dietary supplementation model in mature Duroc boars | 8-OHdG | ELISA assay | [99] |

| Origanum vulgare | Perinatal dietary intervention model in sows | 8-OHdG | ELISA assay | [100] |

| Origanum majorana | Parental and epirubicin-resistant human lung cancer (H1299) cell lines | 8-OHdG | ELISA assay | [101] |

| Lippia sidoides | Porcine pancreatic elastase-Induced Emphysema in Mice | 8-iso-PGF2α | Immunofluorescence | [102] |

To move beyond single-marker analyses, recent research has embraced untargeted metabolomics and lipidomics, enabling comprehensive profiling of oxidative alterations and metabolic shifts following EO administration [103,104,105]. These high-throughput, data-rich approaches have the potential to uncover unexpected biomarkers, trace the metabolic fate of EO-derived compounds, and thereby elucidate the broader impact of oxidative stress on cellular metabolism [106]. At the same time, the vast quantity of generated data presents new challenges, including those related to data interpretation and normalization. Critical evaluation of results remains essential to draw meaningful conclusions regarding EO efficacy and underlying mechanisms.

6.2. Robust In Vitro and In Vivo Models for Antioxidant Efficacy

6.2.1. Cellular and Organotypic Models

Cellular models remain at the heart of experimental antioxidant research, offering a controlled environment to probe the effects of EOs on oxidative stress. Most studies begin with conventional two-dimensional cell cultures, either using immortalized lines or primary cells, and expose them to oxidative insults. Typical inducers include H2O2, which is valued for its simplicity and rapid ROS elevation [107]; AAPH, a generator of peroxyl radicals, is often preferred for mimicking lipid oxidation [108]. In contrast, newer agents such as RSL3 and ML210 have gained popularity for their ability to trigger ferroptosis by targeting GPX4 activity, thereby inducing lipid peroxidation [109]. Table 3 summarizes the application of various cell-based oxidative stress models, induced by diverse agents, in evaluating the antioxidant activity of EOs.

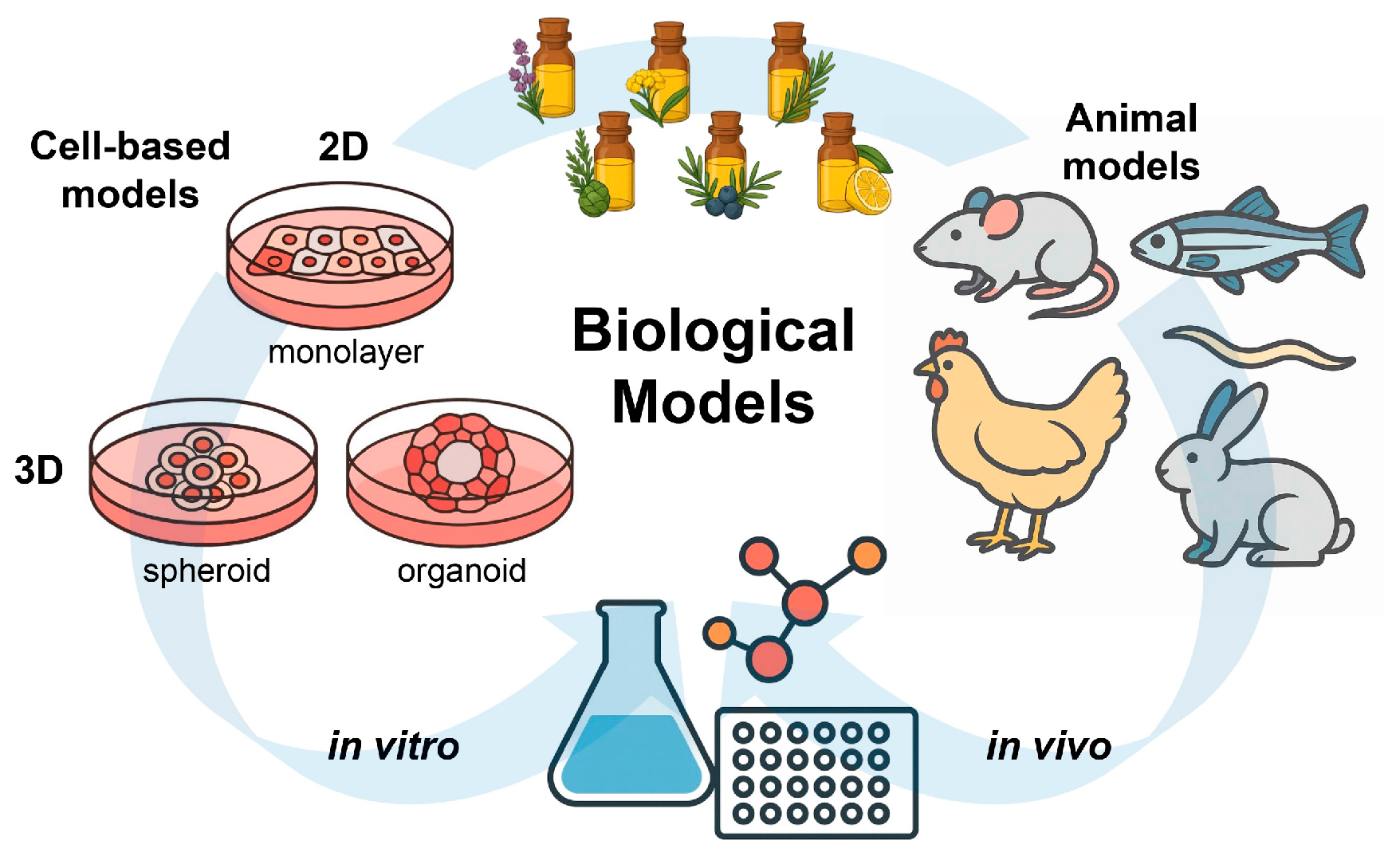

The in vitro research on the antioxidant properties of EOs has traditionally been focused on two-dimensional (2D) monolayer cell cultures. However, as cell culture technologies evolved, the use of three-dimensional (3D) models such as spheroids and organoids has made it possible to replicate the in vivo environment for the evaluation of EO activity [110]. Unlike 2D cultures, 3D models may include some key features of real tissues, including spatial organization, dynamic cell-to-cell communication, and physiological gradients of nutrients and oxygen [111]. For instance, Azadi et al. [112] used multicellular spheroid models to demonstrate that Zataria multiflora EO could suppress apoptosis in spheroids formed from human breast cancer 4T1 and mouse cervical cancer TC1 cells, suggesting that 3D platforms could be extended to study redox-related EO activities in a physiologically relevant setting.

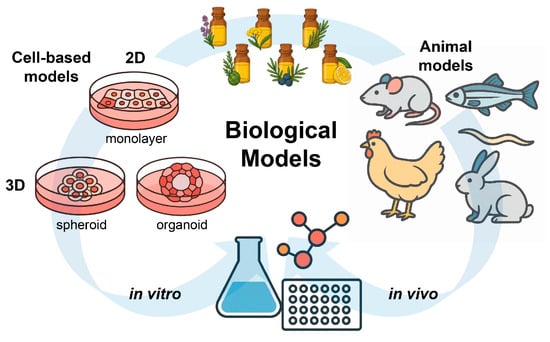

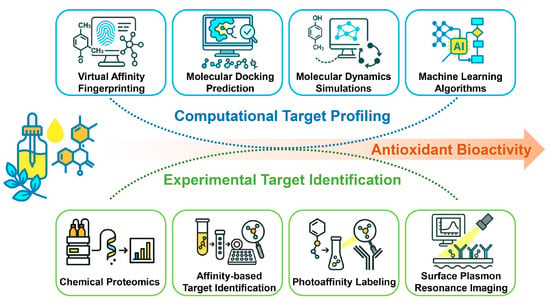

Among available 3D models, organoids are remarkable for their structural complexity and functional relevance. Derived from stem cells, organoids contain multiple cell types and exhibit an organized tissue architecture, which enables them to replicate physiological and pathological processes. For example, Bejoy et al. [113] used human kidney organoids to model acute kidney injury and found that ascorbate could reduce oxidative damage. Nevertheless, studies investigating the effects of EOs in organoid models remain limited. In summary, three-dimensional cultures reflect in vivo conditions better than conventional 2D assays, providing a valuable platform for studying the antioxidant mechanisms of EOs and facilitating future clinical applications (Figure 4).

Table 3.

Representative cellular oxidative stress inducers, mechanisms, and simulated models.

Table 3.

Representative cellular oxidative stress inducers, mechanisms, and simulated models.

| Molecules | Mechanism and Biological Model | EOs/Compounds | Protective Mechanisms | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAPH | Induces lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress, and is widely employed as a standard probe in antioxidant screening assays. | Cinnamon, Thyme, Clove, Lavender, Peppermint | Radical-trapping chain-breaking activity toward peroxyl radicals | [114] |

| H2O2 | Elevates intracellular ROS levels, thereby inducing general oxidative stress and serving as a model for neurodegeneration and ischemia–reperfusion injury. | Alpinia zerumbet | Direct scavenging of intracellular ROS, preservation of cellular GSH levels, and protection against oxidative DNA damage | [115] |

| tert-Butyl hydroperoxide (t-BHP) | Generates ROS and initiates lipid and protein oxidation, providing a reliable model for evaluating oxidative damage and cellular antioxidant defenses. | Thymol, Carvacrol | Attenuation of lipid peroxidation and cytotoxicity in normal fibroblasts | [116,117] |

| RSL3, ML210, Erastin | Inhibit GPX4 or system Xc−, inducing ferroptosis and enabling the study of ferroptotic cell death in contexts such as neurodegeneration, cancer, and kidney injury. | Pomelo Peel, Amomum kravanh, β-Caryophyllene | Activation of the Nrf2 signaling axis, upregulation of GPX4 and SLC7A11, suppression of phospholipid peroxidation and inhibition of ferroptosis | [118,119,120,121] |

Figure 4.

Schematic overview of in vitro and in vivo biological models used to evaluate the antioxidant activity of EOs. Cell-based systems include 2D monolayers and 3D cultures (spheroids and organoids), while animal models provide complementary in vivo evidence under physiologically relevant conditions.

6.2.2. Animal Models of Oxidative Stress and Disease

Animal models are indispensable for elucidating the role that oxidative stress has in tissue injury and also for evaluating the therapeutic efficacy of antioxidants in vivo. These models allow for an assessment of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties, including absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and finally physiological and pathological responses in the organism [122,123]. Pathological conditions in oxidative stress resemble those observed in human diseases. Animal models facilitate mechanistic investigations and the identification of relevant molecular targets [124,125]. Furthermore, they provide critical platforms for screening and validating antioxidants in terms of their bioavailability and in vivo efficacy [126].

Animal models are generally utilized following the addition of agents that directly or indirectly promote the accumulation of ROS or trigger oxidative metabolic disturbances [124]. As an example, liver damage associated with oxidative stress can be reproduced using carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) or tert-butyl hydroperoxide (t-BHP) [127,128], while doxorubicin (adriamycin) is commonly used to study heart injury associated with excessive ROS production [129]. In the context of the nervous system, exposure to paraquat or 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) is used to induce oxidative stress-related neurotoxicity [130]. Acute lung injury can be induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) injections or prolonged cigarette smoke exposure, which initiate inflammatory oxidative cascades [131,132]. Streptozotocin (STZ) is a classic tool for generating diabetic models, in which oxidative damage is a major contributor to disease progression [133]. High-fat diets are typically used to cause sustained oxidative stress in studies of metabolic syndrome, obesity, or atherosclerosis [134]. Finally, additional protocols include H2O2, AAPH, radiation, or ischemia–reperfusion injury to selectively target certain organs or systems [135,136,137].

In recent years, a growing body of in vivo research has utilized various chemically induced oxidative stress models to evaluate the antioxidant properties of EOs and their bioactive components (Table 4). By employing diverse animal models, each characterized by specific chemical agents, the studies have shown the protective effects of EOs in a wide range of pathological conditions and provide experimental support for the therapeutic potential of EOs in the management or prevention of oxidative stress–related diseases.

The selection of animal models and oxidative stress induction methods profoundly influences the interpretation and translational relevance of in vivo studies on antioxidant activity. Chemically induced systems, although widely used, reproduce only limited aspects of oxidative stress rather than its full physiological complexity. For example, agents such as paraquat or streptozotocin trigger acute oxidative injury through redox cycling or mitochondrial disruption but may bypass the regulatory networks that underlie chronic, multifactorial diseases [138]. Moreover, substantial variability in strain susceptibility, dosing regimens, and assessment parameters can result in inconsistent phenotypes and hinder cross-study comparisons. These models may also be confounded by direct toxic effects unrelated to disease progression, and their inability to reproduce complex pathological hallmarks such as progressive fibrosis or inflammation further limits their translational value [139]. Consequently, the use and interpretation of animal models require a mechanistically informed and cautious approach to derive biologically meaningful insights into the antioxidant mechanisms of EOs.

Recently, several technological improvements have made it possible to observe oxidative events in animal models with great precision. For example, real-time imaging approaches such as bioluminescence [140] and positron emission tomography (PET), enable researchers to trace oxidative stress-related probes or drugs within the body, giving a non-invasive window into molecular processes [141]. The use of animals engineered to express biosensors that respond to redox changes has further expanded experimental techniques.

Table 4.

Representative cellular oxidative stress inducers, mechanisms, and simulated models in vivo.

Table 4.

Representative cellular oxidative stress inducers, mechanisms, and simulated models in vivo.

| Inducer | Induced Models | Oxidative Mechanism | EOs/Compounds | Effects In Vivo | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) | CCl4-induced hepato/renal toxicity in mice | Radical metabolite causes hepatic lipid peroxidation and injury | Salvia officinalis EO | Reduced liver/kidney damage, oxidative stress, DNA breaks; improved antioxidant defenses and tissue structure | [142] |

| Cisplatin | Cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in Balb/c mice | Mitochondrial dysfunction, renal oxidative stress | Pituranthos chloranthus EO | Mitigated cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity, reduced DNA damage, oxidative stress, and inflammation | [143] |

| Doxorubicin (Adriamycin) | Doxorubicin-induced nephrotoxicity in male Wistar rats | ROS production, cardiomyocyte/liver/kidney injury | Satureja khuzistanica EO | Attenuated DOX-induced nephrotoxicity and apoptosis via mitochondrial/extrinsic pathway; limited effect on oxidative stress | [144] |

| D-galactose | D-galactose -induced cognitive deficits in mice | Chronic systemic oxidative stress, mimics aging | Lavender EO and Linalool | Improved cognition, restored Nrf2/HO-1, SOD, GPX, and synaptic plasticity proteins | [145] |

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | LPS-induced acute lung injury in rats | Immune activation, inflammation-induced ROS | Chimonanthus nitens EO | Reduced inflammation, improved antioxidant enzymes, attenuated lipid oxidation, modulated SCFAs | [146] |

| Acrylamide | Acrylamide-induced liver toxicity in rats | Neurotoxicity via ROS generation | Thymus satureioides EO | Suppressed liver enzymes, oxidative stress, NLRP3 inflammasome/NF-κB axis, and collagen deposition | [147] |

| High-fat diet (HFD) | HFD-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice | Promotes lipid peroxidation, metabolic stress | Ginger EO | Ameliorated hepatic injury, improved lipid metabolism, suppressed oxidative stress and inflammation | [148] |

| Monosodium urate (MSU) | MSU-induced gouty arthritis in rats | Crystal-induced inflammation and ROS | Citronella and Nutmeg EOs | Reduced joint swelling, neutrophil infiltration, oxidative stress, and NLRP3 inflammasome activity | [79] |

| Isoproterenol (ISO) | ISO-induced myocardial infarction in rats | Cardiac oxidative stress, induces heart injury | Commiphora molmol EO | Ameliorated cardiac injury, improved Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, suppressed oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis | [149] |

| Streptozotocin (STZ) | STZ-nicotinamide-induced type 2 diabetes in rats | Beta-cell destruction, induces diabetes and oxidative stress | Mentha piperita EO | Reduced hyperglycemia, improved insulin/C-peptide, enhanced antioxidant status, protected liver and pancreas tissues | [150] |

| Paraquat | Paraquat-induced pulmonary toxicity in rats | Redox cycling, massive ROS generation | Myrtenol | Restored SOD, CAT, thiol, reduced TNF-α, IL-6, MDA, improved lung histopathology and antioxidant status | [151] |

| Ethanol | Ethanol-induced gastric injury in rats | Induces liver oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation | Rosmarinus officinalis EO | Protected against gastric lesions via antioxidant action; increased SOD and GSH-Px, reduced lipid peroxides | [152] |

| Ultraviolet (UV) radiation | UVB-induced oxidative stress in albino rats | Directly increases ROS, DNA and skin damage | Calendula officinalis EO | Significantly decreased MDA, increased catalase, GSH, SOD, ascorbic acid, and total protein in skin tissue | [153] |

| Mercury chloride (HgCl2;) | HgCl2;-induced oxidative damage in male rats (testis, spleen, kidney) | Induces oxidative stress, inflammation, and reproductive/renal toxicity | Origanum EO | Decreased TBARS, increased GSH, SOD, and CAT; restored trace elements (Zn, Cu, Mg, Fe), testosterone, and improved histological alterations in testis and spleen | [154] |

6.3. Molecular Pathways and Redox Regulation Networks

6.3.1. Core Redox-Signaling Pathways and Experimental Approaches

The Nrf2/Keap1 pathway acts as a central regulator of the antioxidant defense by regulating the expression of numerous cytoprotective genes [68]. The NF-κB pathway complements this role by modulating inflammatory and immune responses, thereby linking redox regulation with inflammation and cellular protection [155]. Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling, through cascades including ERK, JNK, and p38 MAPK, further orchestrates cellular decisions involving survival, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis in response to oxidative cues [156]. Additionally, the recently characterized ferroptosis pathway represents a crucial iron-dependent mechanism of regulated cell death associated with lipid peroxidation [157]. This has paved the way for new studies aimed at understanding oxidative damage and cellular homeostasis.

To dissect these intricate signaling networks, a broad array of experimental approaches has been employed. Immunoblotting and immunofluorescence techniques facilitate the visualization and quantification of protein expression levels, phosphorylation status, and nuclear translocation events. Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) allows precise quantification of transcriptional changes in genes involved in redox signaling. Luciferase reporter assays provide a functional assessment of transcription factor activity, which enables direct evaluation of promoter activation events. Furthermore, cutting-edge phosphoproteomic profiling offers extensive mapping of protein phosphorylation events, revealing critical post-translational modifications that are pivotal in signal transduction and redox regulation. These sophisticated methodologies enable the comprehensive analysis and interpretation of the dynamic regulatory events underpinning EO-induced antioxidant responses.

6.3.2. Activation of the Nrf2/Keap1 Signaling Pathway

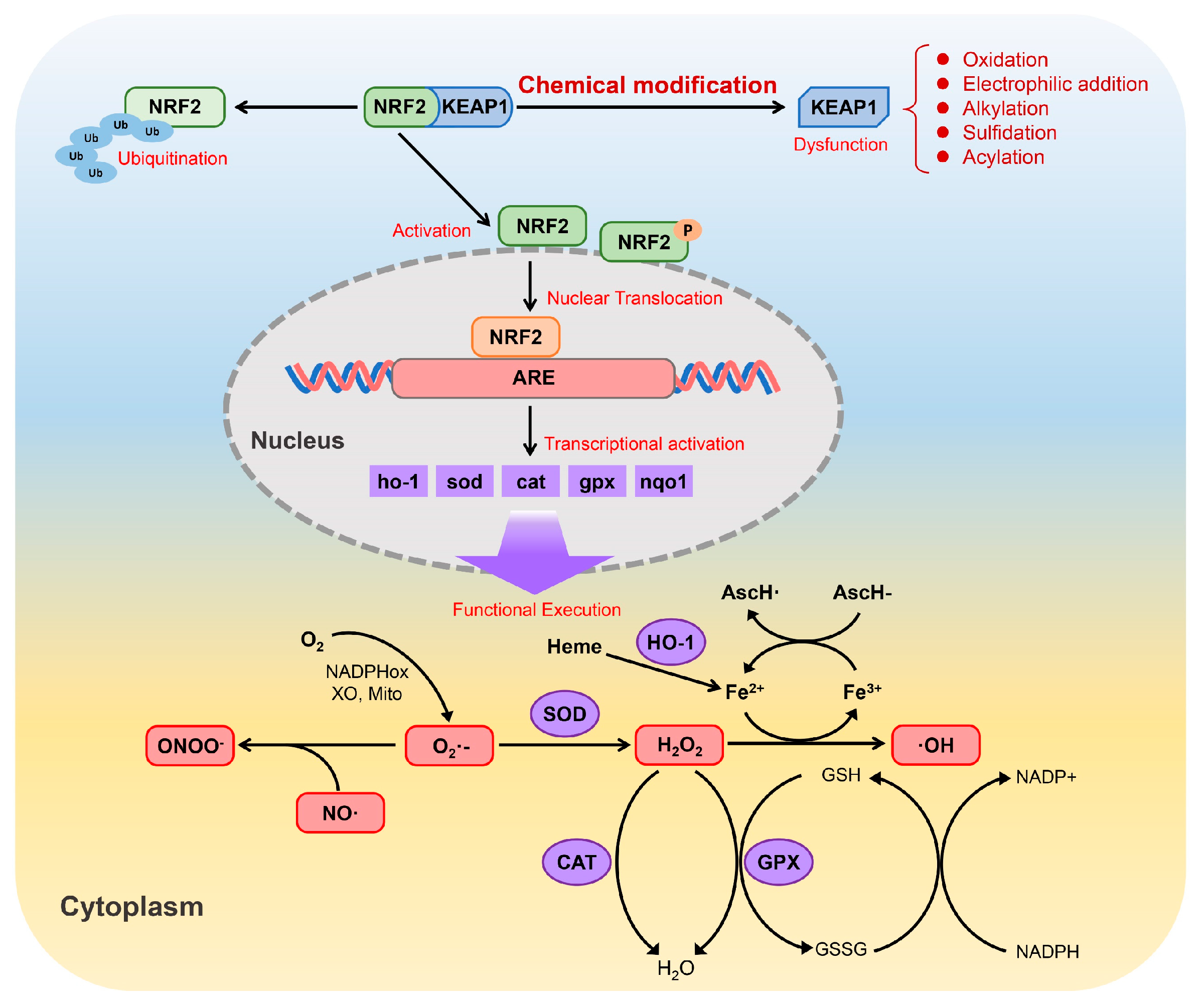

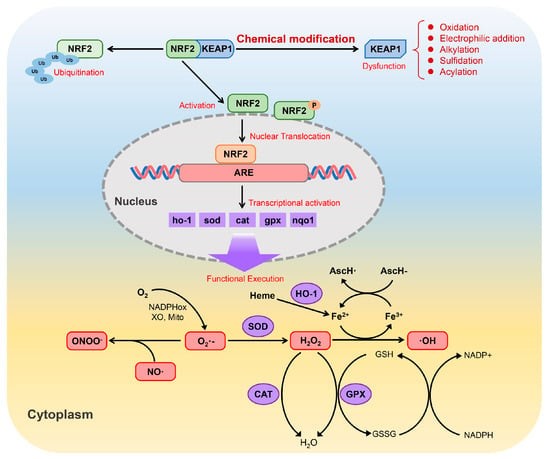

The Nrf2/Keap1 pathway is fundamental for protecting cells from oxidative and electrophilic stress. Nrf2 acts as a transcription factor that induces a wide spectrum of antioxidant and detoxifying genes. In resting conditions, Nrf2 is retained in the cytoplasm by Keap1, a sensor protein rich in reactive cysteine residues [158]. Upon exposure to oxidative or electrophilic stimuli, critical cysteine residues on Keap1 are chemically modified, which weakens its ability to repress Nrf2. As a consequence, Nrf2 becomes stabilized, translocates into the nucleus and binds to antioxidant response elements (AREs), thereby initiating the transcription of downstream cytoprotective genes, including HO-1, SOD, CAT, GPX and NQO1 [159].

The proteins encoded by these genes collectively contribute to cellular redox control by limiting the accumulation of ROS/reactive nitrogen species (RNS). Through the coordinated actions of SOD, CAT, GPX and HO-1, highly reactive species such as superoxide (O2•−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), peroxynitrite (ONOO−) and hydroxyl radicals (•OH) are efficiently detoxified. Beyond direct ROS scavenging, Nrf2 signaling also interfaces with iron redox metabolism and the glutathione system (GSH/GSSG/NADPH), forming an integrated network that supports redox homeostasis and enhances cellular resistance to oxidative injury (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the Nrf2/Keap1 signaling pathway and its role in the regulation of cellular antioxidant defenses (adapted from Ref. [160]).

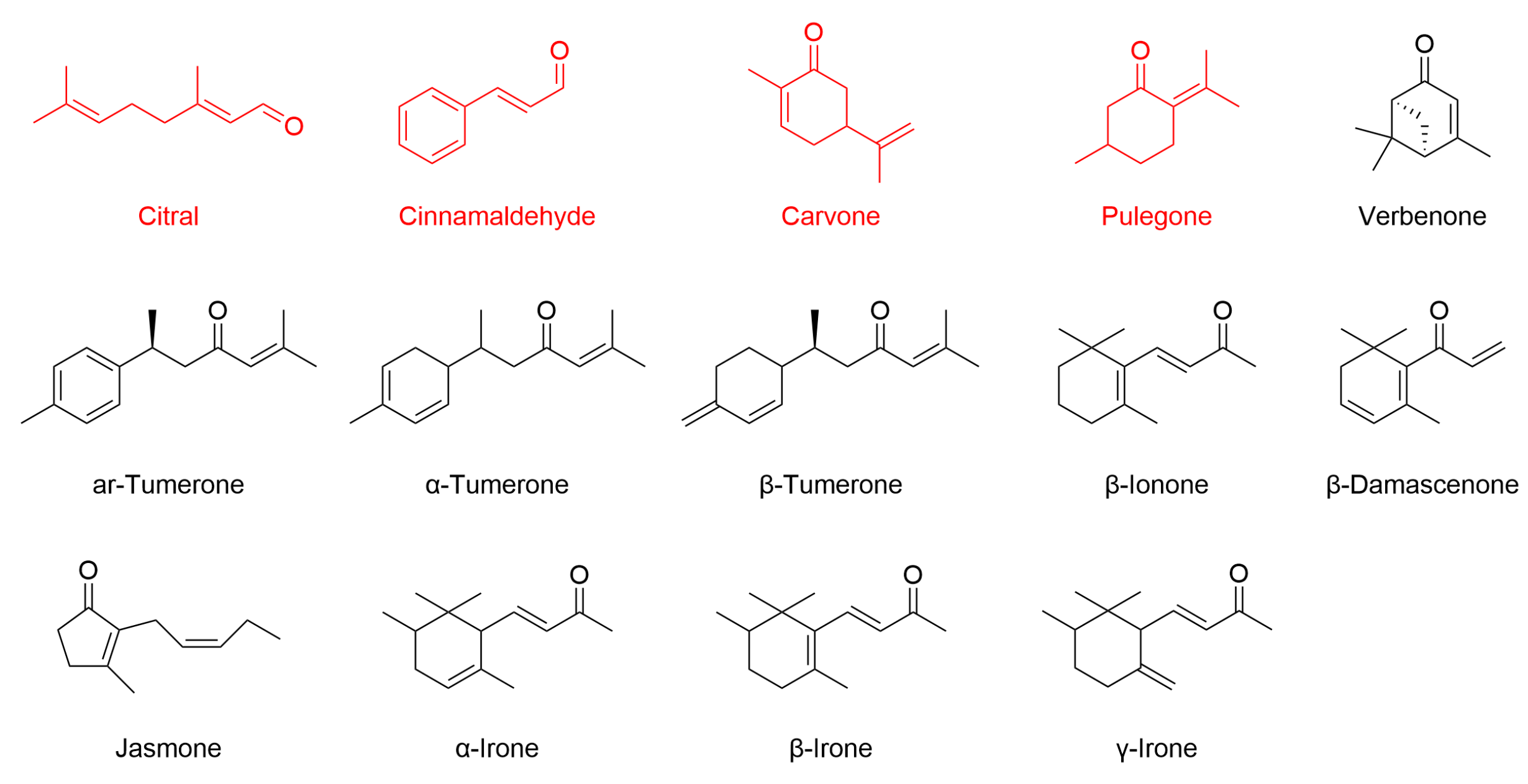

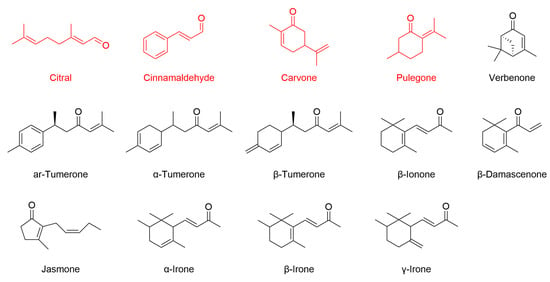

The pathway can be triggered either directly, through covalent modification of reactive cysteine residues on Keap1 by electrophilic or oxidative compounds, or indirectly, through upstream signaling cascades such as MAPK or PI3K/Akt that facilitate Nrf2 release from Keap1 [161]. Structurally, Keap1 is highly sensitive to electrophilic molecules [162]. As summarized in Table 5, cinnamaldehyde is the most extensively studied EO constituent containing an α,β-unsaturated carbonyl group. Other EO compounds, including citral, carvone, and pulegone, share this structural feature and exhibit antioxidant activity via Nrf2 pathway modulation. This moiety is present in many phytochemicals capable of undergoing Michael-type addition with thiol groups on Keap1 cysteines [163]. In addition, compounds such as turmerones from turmeric EO, as well as β-ionone, β-damascenone, jasmone, and irones, possess similar carbonyl functionalities. Although these compounds are structurally predisposed to interact with Keap1 (Figure 6), direct evidence for their Nrf2-related activity is still lacking, making them promising candidates for future investigation.

Figure 6.

Chemical structures of selected EO components bearing α,β-unsaturated carbonyl moieties. Citral, cinnamaldehyde, carvone, and pulegone (highlighted in red) have been shown to activate Nrf2-dependent antioxidant responses, as evidenced by increased Nrf2 expression or activity in relevant biological models. For the other compounds illustrated, there is currently no published evidence supporting a direct role in modulating the Nrf2 pathway.

To date, there is no direct evidence demonstrating that EO-derived molecules can bind to Nrf2 or Keap1. Experimental techniques such as surface plasmon resonance, isothermal titration calorimetry, X-ray crystallography, or pull-down assays have rarely been applied. Most studies rely on indirect functional assays, including the monitoring of Nrf2 nuclear translocation or changes in downstream antioxidant enzymes, sometimes combined with inhibitors or siRNA. While molecular docking has been employed to predict potential interactions, these computational findings have seldom been validated experimentally. As a result, definitive proof of direct binding between EO constituents and these proteins remains elusive.

Many EO constituents can also activate the Nrf2 pathway through electrophilic interactions, as summarized in Table 5. Phenolic compounds such as carvacrol, thymol, and eugenol exhibit potent antioxidant properties but may also undergo oxidation to yield electrophilic quinone-like intermediates. These reactive metabolites are capable of covalently modifying Keap1 cysteine residues, thereby disrupting the Keap1–Nrf2 complex and promoting Nrf2 nuclear translocation. This direct mechanism explains the consistent upregulation of Nrf2-regulated antioxidant genes observed following exposure to these phenolic EO constituents. Non-phenolic constituents, including monoterpenes such as β-caryophyllene, geraniol, linalool, limonene, 1,8-cineole, α-pinene, and p-cymene, also contribute to cellular antioxidant regulation. Although these molecules lack electrophilic α,β-unsaturated carbonyl groups, they may still modulate Nrf2 activity by forming electrophilic metabolites during phase I biotransformation or ROS-mediated oxidation [164]. The mechanisms involved are not yet fully understood and warrant further study. Overall, both phenolic and non-phenolic EO components can shift cellular redox conditions to favor Nrf2 activation. However, current conclusions remain based mainly on chemical reactivity and cell-based assays, whereas strong direct evidence from EO systems is still scarce.

Table 5.

Effects of EOs and their constituents on the Nrf2 pathway in different oxidative stress models and corresponding detection methods.

Table 5.

Effects of EOs and their constituents on the Nrf2 pathway in different oxidative stress models and corresponding detection methods.

| Compounds/EOs | Induced Model | Regulation of the Nrf2 Pathway | Detection Methods | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cinnamaldehyde | H2O2-induced oxidative stress in HepG2 cells | Promotes nuclear translocation of Nrf2 and upregulates downstream antioxidant enzymes. | Western blot, immunofluorescence, qPCR, siRNA | [165] |

| Cinnamaldehyde | High-glucose mouse aorta and endothelial cells | Enhances nuclear translocation and expression of Nrf2, and increases HO-1 and NQO1 expression. | Western blot, immunofluorescence, siRNA | [166] |

| Cinnamaldehyde | db/db diabetic mouse aorta and kidney tissues | Upregulates Nrf2, HO-1, GPX-1, and NQO-1, and ameliorates oxidative damage. | Western blot, qPCR, siRNA | [167] |

| Cinnamaldehyde | H2O2-treated bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and ovariectomized mice | Increases Nrf2, HO-1, and NQO-1 expression, and promotes Nrf2 nuclear translocation. | Western blot, immunofluorescence, immunohistochemistry (IHC), siRNA | [168] |

| Cinnamaldehyde | H2O2-treated human dermal papilla cells | Promotes Nrf2 nuclear translocation and increases HO-1 expression. | Western blot, immunofluorescence, qPCR, siRNA | [169] |

| Cinnamaldehyde | BaP-induced oxidative stress in HaCaT cells | Promotes Nrf2 nuclear translocation and increases HO-1 expression. | Western blot, immunofluorescence, qPCR, siRNA | [170] |

| Cinnamaldehyde | Human umbilical vein endothelial cells | Upregulates Nrf2 downstream antioxidant enzymes. | Western blot, immunoprecipitation, nuclear fractionation, siRNA | [171] |

| Cinnamaldehyde | Normal human epidermal keratinocytes | Upregulates GPX2 and NQO1 in an Nrf2-dependent manner. | Western blot, siRNA | [172] |

| Cinnamaldehyde | TGF-β1/IL-13-treated normal human dermal fibroblasts | Promotes nuclear translocation of Nrf2 and increases HMOX1 and NQO1 expression, exerting antifibrotic effects. | Western blot, immunofluorescence, qPCR, siRNA | [173] |

| Cinnamaldehyde | HCT116 colorectal cancer cells and mouse colon tissues | Upregulates Nrf2, HO-1, and NQO1, and downregulates Keap1. | Western blot, qPCR, IHC | [174] |

| Cinnamaldehyde | H2O2-treated V79-4 lung fibroblasts | Increases Nrf2, phospho-Nrf2, and HO-1 expression, and decreases Keap1. | Western blot, ELISA, siRNA | [175] |

| Cinnamaldehyde | High-fat and high-glucose diet-induced metabolic syndrome in Wistar rats | Increases vascular Nrf2 activity and upregulates HO-1 and related enzymes. | Transcription factor DNA-binding assay, qPCR | [176] |

| Cinnamaldehyde | H9c2 cardiomyocytes and doxorubicin-injured rat myocardium | Promotes Nrf2 nuclear translocation and HO-1 expression, and inhibits ferroptosis. | Western blot, qPCR, IHC, siRNA | [177] |

| Cinnamaldehyde | Zymosan-stimulated KERTr human keratinocytes | Upregulates Nrf2, HO-1, and NQO1 at low doses, and exerts anti-inflammatory effects in a Nrf2-dependent manner. | Western blot, qPCR, shRNA, ELISA | [178] |

| Cinnamaldehyde | H2O2- and TNF-α-stimulated human umbilical vein endothelial cells | Promotes Nrf2 nuclear translocation, upregulates HO-1, and reduces inflammation. | Western blot, qPCR, siRNA, immunoprecipitation | [179] |

| Cinnamaldehyde | LPS-induced neuroinflammation mouse model | Promotes Nrf2 nuclear translocation, increases SOD and GST, and reduces MDA levels. | ELISA, enzyme activity assay, Western blot | [180] |

| Cinnamaldehyde | Oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion-injured H9c2 cardiomyocytes | Upregulates Nrf2, HO-1, and PPAR-γ expression. | Western blot, qPCR, siRNA, enzyme activity assays | [181] |

| Cinnamaldehyde | In vitro thioredoxin reductase assay using HCT116 colorectal cancer cells | Activates the Nrf2/ARE pathway, upregulates TrxR, and inhibits TrxR in a dose-dependent manner. | Luciferase reporter assay, Western blot, enzymology | [182] |

| Cinnamaldehyde | H2O2- and arsenic-treated HCT116, HT29, and FHC colon cells | Increases Nrf2, HO-1, and γ-GCS expression, and exerts Nrf2-dependent antioxidant protection. | Luciferase reporter assay, Western blot, qPCR, siRNA | [183] |

| Citral | Adriamycin-induced FSGS mouse model and RAW264.7 macrophages | Alleviates renal injury by activating Nrf2, upregulating HO-1/NQO1, and inhibiting oxidative stress and apoptosis. | Western blot, ELISA, IHC | [184] |

| Citral | LPS-induced endometritis mouse model and Nrf2 knockout mice | Activates the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, suppresses LPS-induced ferroptosis and inflammation, and exhibits Nrf2-dependent protective effects. | Western blot, siRNA | [185] |

| Citral | LPS-accelerated lupus nephritis mouse model and LPS-primed macrophages | Enhances Nrf2 activation, upregulates HO-1 and GPX, and attenuates oxidative stress and NLRP3 inflammasome signaling. | Western blot, IHC, Immunofluorescence, ELISA, TUNEL | [186] |

| Citral, Lemongrass EO | PC12D neuronal cell in vitro model | Targets Keap1 and promotes Nrf2-dependent HO-1 expression, as shown by molecular docking and cellular experiments; animal studies confirm antioxidative effects in brain regions. | Molecular docking, qPCR, Western blot | [187] |

| Carvone | LPS-induced acute lung injury in rats | Significantly upregulates Nrf2 and HO-1 expression in lung tissue, and attenuates oxidative stress and inflammation. | Western blot, histopathology, ELISA, enzyme activity assay | [188] |

| Carvone | CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in rats | Upregulates the Nrf2 pathway, improves antioxidant status (increases GSH, SOD), reduces oxidative damage and fibrosis, and is associated with reduced TGF-β1/SMAD3 signaling. | Enzyme activity assay, IHC, qPCR, liver histology | [189] |

| Pulegone | LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages | Promotes Nrf2/HO-1 expression, downregulates iNOS, COX-2, NF-κB, and MAPKs, and suppresses inflammation and ROS. | Western blot | [190] |

| Pulegone | L-arginine-induced acute pancreatitis mouse model | Inhibits the p38 MAPK/NF-κB pathway, alleviates oxidative stress and inflammatory responses, and upregulates Nrf2 and antioxidant defense enzymes. | Western blot | [191] |

| Eugenol | H2O2-induced injury models in HEK-293 and NIH-3T3 cells | Dose-dependently activates Nrf2 expression and nuclear translocation, upregulates Nrf2 target genes, and exerts antioxidant effects. | Western blot, qPCR, transcriptional activity assays | [192] |

| Carvacrol | Rotenone-induced Parkinson’s disease mouse model | Upregulates Nrf2/HO-1, reduces inflammation, oxidative stress, and NLRP3 activation, and improves motor and neural injury. | Western blot, IHC, enzyme activity assay | [193] |

| Carvacrol | STZ-induced diabetes in rats | Upregulates Nrf2/HO-1, enhances antioxidant enzyme activity, and inhibits NF-κB-mediated testicular apoptosis and inflammation. | Western blot, enzyme activity assay | [194] |

| Thymol, p-Cymene | Immobilization stress in rats | Increases Nrf2 and HO-1 expression, suppresses TNF-α/NF-κB and oxidative stress, and reduces liver inflammation. | qPCR, ELISA, histology | [195] |

| α-Pinene | Ethanol-induced gastric injury in rats | Upregulates Nrf2 and HO-1 mRNA, increases gastric pH, and reduces lesions and oxidative damage. | qPCR, histology, enzyme activity assay | [196] |

| β-Caryophyllene | Hepatic ischemia–reperfusion injury in rats | Upregulates Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1/NQO1, decreases inflammation via TLR4/NF-κB/NLRP3, and reduces oxidative stress. | Western blot, qPCR, IHC, ELISA, enzyme activity assay, in silico docking | [197] |

| β-Caryophyllene | MCAO/reperfusion (cerebral ischemia) rats; OGD/R PC12 cells | Enhances Nrf2 nuclear translocation and HO-1, suppresses ferroptosis, and effect is blocked by Nrf2 inhibitor ML385. | Western blot, inhibitor rescue, neurobehavioral tests, infarct size | [120] |

| β-Caryophyllene | Glutamate-induced C6 glioma cell toxicity | Induces Nrf2 nuclear translocation, improves GSH and GPX, inhibits ROS, and restores mitochondrial function in a CB2R-dependent manner. | Immunofluorescence, GSH, GPX, ROS, MTT, JC-1, Western blot | [198] |

| Carvacryl acetate | Cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury model in rats and H2O2-induced oxidative stress model in PC12 cells | Promotes Nrf2 expression and nuclear translocation, provides antioxidative neuroprotection, and loses protective effects with Nrf2 knockdown. | Western blot, IHC, shRNA | [199] |

| Geraniol | Hepatic ischemia–reperfusion injury model in rats | Markedly activates Nrf2/HO-1, upregulates antioxidant enzymes, and attenuates oxidative stress and apoptosis. | Western blot, enzyme activity assay | [200] |

| Geraniol | Doxorubicin-induced cardiac toxicity in rats | Dose-dependently upregulates Nrf2/HO-1, exhibits antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic activities, and provides cardioprotection. | Western blot, qPCR, tissue biochemical analysis | [201] |

| Geraniol | High-fat diet-induced atherosclerosis model in hamsters | Significantly upregulates Nrf2 and antioxidant enzymes, inhibits lipid peroxidation, and improves endothelial function. | Western blot, biochemical assays | [202] |

| Geraniol | Renal ischemia–reperfusion injury model in rats | Activates Nrf2/HO-1/NQO1, inhibits TLR2/4-NF-κB inflammatory signaling, and protects the kidney. | Western blot, qPCR, molecular docking analysis | [203] |

| Perillyl alcohol | LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells, CFA-induced arthritis in rats | Ameliorates oxidative stress and inflammation via regulation of TLR4/NF-κB and Keap1/Nrf2 pathways, increases Nrf2 and SOD2, and reduces NF-κB and iNOS. | Western blot, qPCR, histology | [204] |

| Perillyl alcohol | OGD/R-induced PC12 cells, Rice-Vannucci hypoxic–ischemic neonatal rats | Activates Nrf2, inactivates Keap1, and reduces oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis; effect is reversed by the Nrf2 inhibitor ML385. | Western blot, Nrf2 nuclear localization, ML385 inhibitor, in vivo/in vitro | [205] |

| Nerolidol | Doxorubicin-induced chronic cardiotoxicity in rats | Modulates PI3K/Akt and Nrf2/Keap1/HO-1 pathways, and inhibits oxidative and inflammatory damage. | Western blot, qPCR, enzyme activity assay | [206] |

| Nerol | Dexamethasone-induced aging in human dermal fibroblasts | Activates the Nrf2 pathway, restores collagen and hyaluronic acid, and protects against glucocorticoid-induced aging; effect is abolished by Nrf2 inhibitor. | Inhibitor validation, functional assays | [207] |