Abstract

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a global public health problem that causes liver-related morbidity and mortality. It is also an independent risk factor for non-communicable diseases. In 2020, a proposal was made to refer to it as “metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD)”, with concise diagnostic criteria. Given its widespread occurrence, its treatment is crucial. Increased levels of oxidative stress cause this disease. This review aims to evaluate various studies on antioxidant therapies for patients with MAFLD. A comprehensive search for relevant research was conducted on the PubMed, SCOPUS, and ScienceDirect databases, resulting in the identification of 87 studies that met the inclusion criteria. In total, 31.1% of human studies used natural antioxidants, 53.3% used synthetic antioxidants, and 15.5% used both natural and synthetic antioxidants. In human-based studies, natural antioxidants showed 100% efficacy in the treatment of MAFLD, while synthetic antioxidants showed effective results in only 91% of the investigations. In animal-based research, natural antioxidants were fully effective in the treatment of MAFLD, while synthetic antioxidants demonstrated effectiveness in only 87.8% of the evaluations. In conclusion, antioxidants in their natural form are more helpful for patients with MAFLD, and preserving the correct balance of pro-oxidants and antioxidants is a useful way to monitor antioxidant treatment.

1. Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) encompasses a range of liver conditions, from harmless non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) to more severe non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) with or without fibrosis, NASH cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [1]. NAFLD is a significant public health concern, as it is a leading cause of liver-related morbidity and mortality globally, and it is also an independent risk factor for non-communicable diseases [2]. A combination of invasive and noninvasive tests is essential to diagnose NAFLD. The most comprehensive test for diagnosing and scoring fatty liver disease is a liver biopsy. The lesion at the most clinically benign end of the spectrum is fatty liver (hepatic steatosis). Both large (macro-) and microscopic (micro-) fat vesicles, mostly consisting of triglycerides, build up inside hepatocytes without significantly inducing scarring, liver cell death, or hepatic inflammation. The lesion at the other extreme end of the spectrum is known as cirrhosis. Hepatic steatosis frequently disappears by the time this level of architectural distortion manifests. Steatohepatitis is a type of liver damage that is characterized by hepatic steatosis and the development of restricted hepatic inflammation and hepatocyte death. Inflammatory infiltration is frequently evident in association with enlarged hepatocytes, which sometimes include Mallory’s hyalin. It consists of both mononuclear and polymorphonuclear leukocytes. These damage foci are primarily found in acinar zone 3 and are sometimes associated with bridging, perivenular, or perisinusoidal fibrosis [3]. The term proposed in 2020 to denote fatty liver disease associated with systemic metabolic dysregulation is “metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD).” The terminological transition from NAFLD to MAFLD was accompanied by a concise set of diagnostic criteria, facilitating convenient identification at the patient’s bedside for the broader medical community, including primary care providers [4].

Numerous interrelated mechanisms are involved in the pathophysiology of MAFLD. These processes include the infiltration of proinflammatory cells, which results in hepatic injury and ultimately leads to hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation and fibrogenesis; lipotoxicity, which results from the accumulation of toxic lipid species; and insulin resistance (IR), which determines the metabolic syndrome. Although the proximal processes, such as inflammation, lipid excess, and lipotoxicity, have been extensively characterized, the downstream molecular mechanisms, including fibrogenesis, hepatocyte lipoapoptosis, and inflammatory processes, are not completely understood [5].

Liver diseases have a substantial impact on global health, with NAFLD being the most common worldwide, affecting 20–30% of the general population [6]. It affects 20–35% of adults, 15% of children, and up to 80% of individuals with obesity [7]. Cases increase markedly in patients with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and hyperlipidemia due to their connection to insulin resistance and metabolic dysfunction. However, NAFLD can affect individuals who have a normal weight and do not have metabolic problems, making up approximately 16% of cases [8]. Furthermore, NAFLD has led to an increase in death rates and liver transplants, particularly in the United States. Due to the fact that NAFLD is asymptomatic in its early stages, the actual burden of the disease can exceed the reported numbers [9]. The prevalence rates differ by region, ranging from 13.5% in Africa to 46% in America and an estimated 20–30% in Europe [2].

There is an opinion that a combination of several supportive treatments may be suitable for treatment. Due to the direct effect of body mass on NAFLD, weight loss treatment methods are used, the most important of which are changes in lifestyle through changes in eating habits and physical activity, as they reduce liver fat, and they should be used as the first line of treatment [10]. Over the past few decades, researchers have investigated several therapeutic agents that target different aspects of metabolic disorders, such as lipotoxicity, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and fibrosis, but some of these agents have been associated with disadvantages. However, the treatment used today includes antioxidants, such as vitamin E, and antidiabetic drugs, such as pioglitazone, and one of the treatments that has received a lot of attention in recent years is the targeting of intestinal bacteria [11,12].

Oxidative stress (OS) is characterized by an inconsistency between the generation of reactive species (RS) and antioxidant (AO) defenses [13]. A comprehensive description characterizes it as “an imbalance between oxidants and AOs, with oxidants having a greater advantage, resulting in a disturbance of redox signaling and regulation and/or molecular damage” [14]. OS is a crucial mechanism that contributes significantly to liver damage in MAFLD, playing a critical role in the transition from simple steatosis to NASH. Previous studies have obtained evidence showing that an increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) can trigger lipid peroxidation, resulting in inflammation and fibrogenesis via the activation of stellate cells [15]. Furthermore, ROS hinders the production of very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) by hepatocytes, leading to a buildup of fat in the liver. Additionally, ROS have the potential to induce hepatic insulin resistance and necroinflammation, as well as activate many intracellular pathways, which might ultimately result in hepatocyte apoptosis [16].

Different results have been obtained regarding the effect of antioxidants, which requires discussion. This systematic review aims to collect information on the impact of antioxidants in the treatment of MAFLD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

In this packccsystematic review, the recommendations stated in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed. The systematic review protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database under the registration ID CRD42024534095, and a detailed exploration of the PubMed, SCOPUS, and ScienceDirect databases was performed. The primary sources of antioxidants are natural and dietary sources, as well as synthetic and medicinal supplements. Additionally, a search was performed using relevant keywords or title headings. Full details of the search strategy can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Full details of the search strategy terms.

2.2. Study Selection

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for this review are described in Table 2. As an essential requirement for inclusion in the review, the research had to satisfy all established inclusion criteria. Publications were individually screened by two authors, KM and FF, to ensure compliance with the established inclusion criteria. Consequently, comprehensive reports were obtained for studies that indicated inconsistency or seemed to satisfy the inclusion criteria. Furthermore, disagreements were effectively resolved through an intensive evaluation process, resulting in the achievement of a consensus. On occasions when consensus could not be reached, the opinion of a third reviewer (SK) was sought.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

The reviewers autonomously extracted and documented data, including the author and publication year, population attributes such as sample size, antioxidant intervention (supplementation/dietary and medicinal forms), the duration of follow-up, post-intervention status, and quality control score determined by the two independent reviewers. The studies were evaluated using a study design and sampling method suitable for research. The sample size was sufficient, taking into account the prevalence of MAFLD. The evaluation of the results was performed using approved criteria. The outcomes were analyzed impartially, and the response rate was adequate. The statistics were reported with confidence intervals, and detailed descriptions of the study subjects were provided. Ultimately, the quality assessment determined that the selected studies met all the specified criteria and could be considered acceptable.

4. Results

4.1. Search Results

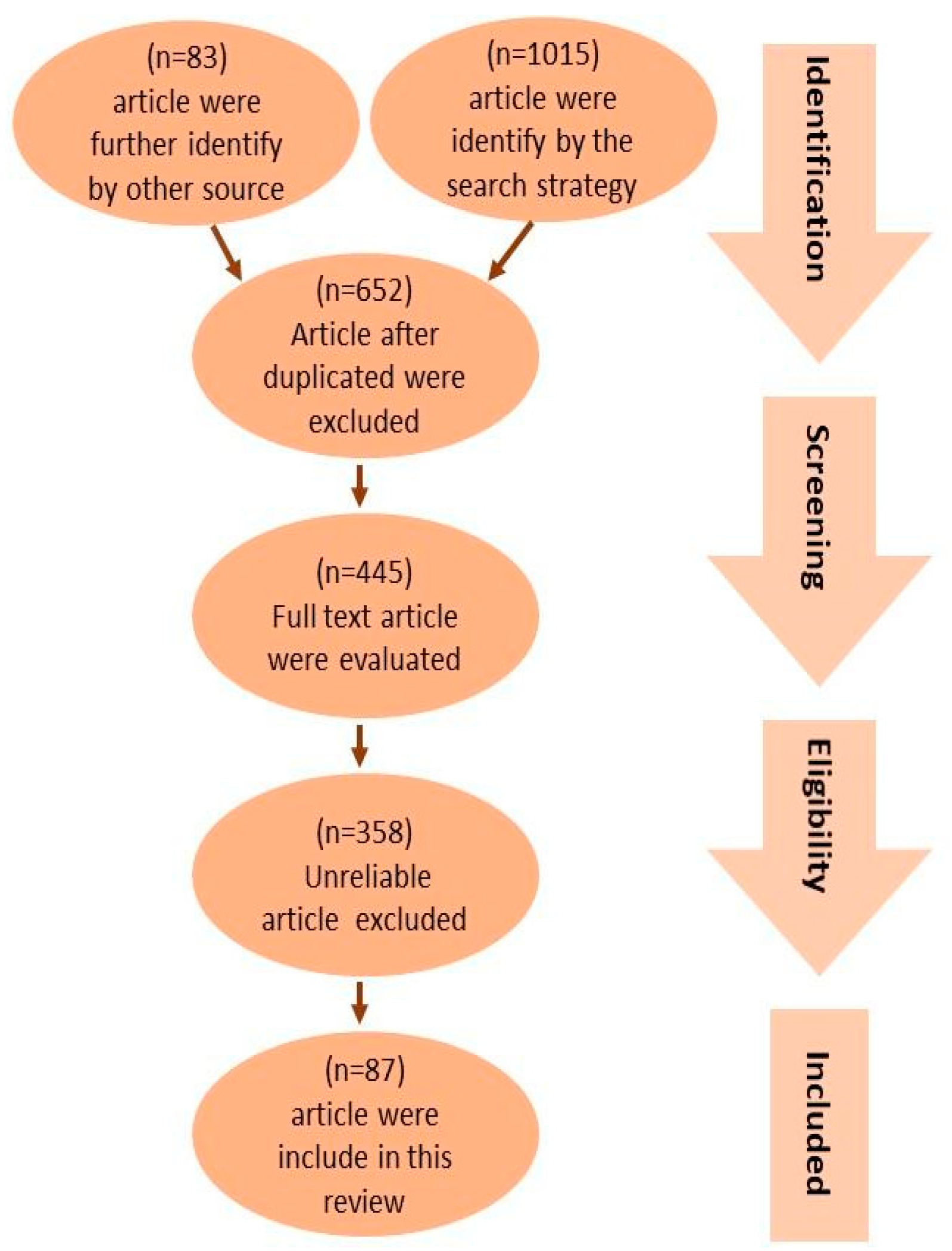

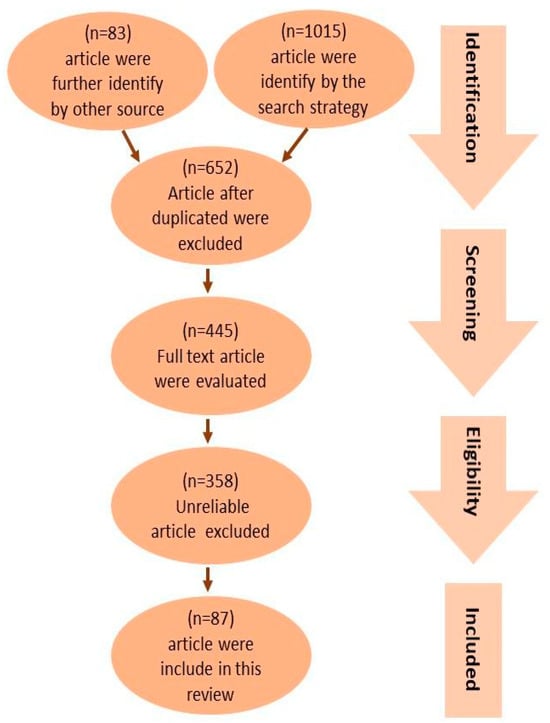

Figure 1 provides a concise overview of the procedure used to select pertinent studies. The search approach identified an overall number of 1015 articles. Furthermore, an additional 83 articles were found through an extensive review of the reference lists of pertinent reviews. Following the exclusion of duplicates, a total of 653 articles were selected based on their title and abstracts to determine their eligibility. A total of 445 articles were evaluated using their full texts, while 358 articles were removed due to factors such as untrustworthy study designs (including case reports, ethnographies, and observational designs), patient populations, interventions, outcome measurements, sample sizes smaller than 10, or the inaccessibility of the full text. As a result, a total of 87 articles were included in this review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram showing the study selection and identification. A total of 1015 publications were identified, with 535 articles in the human studies category and 480 articles in the animal studies category. By looking through the reference lists of pertinent reviews, an additional 83 publications were found, 38 of which were animal studies and 48 of which were human studies. After duplicates were eliminated, 653 articles were chosen for eligibility according to their title and abstract. Of these, 445 articles underwent full-text evaluations; 358 articles were omitted due to faulty data. As a result, in this review, 87 publications were included, with 45 being human studies and 42 being animal studies.

4.2. Study Characteristics

Of the 45 human studies, 14 (31.1%) used natural antioxidants, 24 (53.3%) used synthetic forms of antioxidants in dietary supplements and medications, and 7 used natural and synthetic antioxidants. Of the 24 studies that studied synthetic forms of antioxidants, 14 (58.8%) used dietary supplements, 4 (16.6%) used medications, and 6 (25%) used both dietary supplements and medications.

Among the human studies, 43 (95.5%) revealed a considerable effectiveness of antioxidant therapy, while 2 (4.4%) did not find significant differences from the placebo group. Of the 43 studies that had a significant effect, 14 examined natural antioxidants, 22 examined synthetic antioxidants, and 7 examined both natural and synthetic antioxidants. Furthermore, the two studies where no significant difference was seen examined synthetic antioxidants. Also, 30 studies examined both genders (66.6%), 8 studies (17.7) and 1 study (2.2%) included only males and females, respectively, and 6 studies did not mention the gender of cases. In addition, most of the studies, 38 of 45, have been designed as experimental, while there were 4 human studies, and 3 other studies used both experimental and human study design. The findings are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

The summarized results of human studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Of the 42 animal studies, 10 (23.8%) used natural antioxidants, and 32 (76.1%) studies used synthetic forms of antioxidants in dietary supplements and medications. Of the 32 studies that studied synthetic forms of antioxidants, 7 (21.8%) used dietary supplements, and 25 (78.1%) studies used medications.

Among the animal studies, a total of 38 investigations, representing 90.4% of the studies, indicated considerable effectiveness of antioxidant therapy. On the contrary, in four studies (9.5%), no significant changes were detected between the antioxidant therapy group and the placebo group. Of the 38 studies that indicated significant effectiveness, 10 examined natural antioxidants, and 28 studies examined synthetic antioxidants. All four studies where no significant difference was seen examined synthetic antioxidants. The findings are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summarized data of animal studies.

5. Discussion

The present study was conducted as a systematic review to investigate the impact of antioxidant therapy on patients with MAFLD. This study investigated two types of antioxidants: natural antioxidants, found in fruits and vegetables, and synthetic antioxidants, such as dietary supplements or medications.

The analyzed studies indicate that natural antioxidants have a high level of efficacy in the treatment of MAFLD (100%). However, there is a scarcity of research using this method. The positive impact of synthetic antioxidants is not consistently observed, and only 91% of the studies demonstrate successful outcomes. On the basis of the available data, it may be inferred that natural antioxidants show greater efficacy than synthetic antioxidants in the treatment of MAFLD. Furthermore, fruits and vegetables are abundant in essential elements, as well as antioxidants. In contrast, previous studies have shown that the correct combination of minerals, such as sodium, potassium, selenium, magnesium, zinc, copper, and calcium, in conjunction with antioxidants, can improve the efficacy of antioxidants [104].

The impact of genetics on liver steatosis, inflammatory modifications, and fibrosis has been established by several studies. In genome-wide research, two genes have been associated with an increased risk of MAFLD: patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 (PNPLA3) and trans-membrane 6 superfamily member 2 (TM6SF2) [9]. Lean MAFLD is a condition where individuals demonstrate a fatty liver but a normal body mass index (BMI). The main risk factors for this disease are visceral obesity, insulin resistance, high cholesterol, fructose intake, and specific genes. The triacylglycerol lipase enzyme, which is produced by the PNPLA3 gene, regulates lipid hydrolysis and assists in preserving balance between energy and its utilization in adipose tissue. Steatosis, inflammation, fibrosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) can all be caused by a particular SNP in this gene. However, patients with MAFLD have a significantly decreased hepatic gene expression of TM6SF2, a gene essential for the generation of very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) [105]. An important gene, designated G-protein-coupled receptor 120 (GPR120), is present in hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, and adipocytes. It functions as a receptor for polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). Hepatocyte damage is the basis of abnormal liver function tests (LFTs) in individuals with the GPR120 270H mutation. Targeted by glitazone diabetes medications, PPARγ is frequently expressed in adipose tissue and influences both the arrival and departure of fatty acids to and from the liver, as well as the development of adipocytes. Liver steatosis is caused by these gene mutations [9].

Both in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that silybin or silibinin restores nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide+ (NAD+), a coenzyme essential for redox processes, by blocking poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase and triggering the SIRT1/AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway. Reduced AMPK activity has been linked to the de novo lipogenesis process in MAFLD. Silybin’s anti-inflammatory action is achieved through the activity of SIRT2. Supplementing NAD+ with silybin has been found to be beneficial in preserving SIRT2 activity. Silybin has been shown to inhibit endoplasmic reticulum stress and the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in mice with fatty liver disease associated with metabolic dysfunction fed a high-fat diet [106].

Vitamin C has been reported to reduce mitochondrial ROS production, elevate levels of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase, and enhance electron transport chain function in the liver. Vitamin C affects the balance of lipids and glucose and reduces visceral obesity and MAFLD by activating PPARα [9].

Multiple in vitro investigations on mouse and human adipocytes have shown that vitamin D has an anti-inflammatory impact by reducing the expression of chemokines and cytokines through the activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase and the NF-κB classical inflammatory pathway [9].

Vitamin E can boost antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase; conversely, it reduces pro-oxidant contributions such as cellular myelocytomatosis (c-myc) and transforming growth factor-alpha (TGF-α), nitric oxide synthase, and NADPH. The antisteatotic activity of this substance is due to its capacity to decrease fatty acid uptake by hepatocytes via the downregulation of the hepatic cluster of differentiation 36 (CD36) protein, thereby limiting the amount of lipids available for peroxidation. Vitamin E reduces hepatic inflammation and fibrosis by downregulating the expression of pro-apoptotic BCL2 associated X (BAX), TGF-β, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), and matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) genes [1].

Plant flavonoids contain the naturally occurring flavonoid molecule quercetin. Quercetin’s antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant activities protect against free radicals, in addition to providing pharmacological advantages. One of the most abundant and substantial sources of quercetin is acacia rice. Numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of quercetin, a flavonoid with potent antioxidant properties, in reducing lipid accumulation and the expression of SREBP1c and XBP-1 in adipocytes. A direct antilipogenic impact is produced by inhibiting the DNL pathway through its effects on the AMPK pathways [107].

Turmeric contains a polyphenolic compound known as curcumin, which has a number of medicinal effects, including anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative, antioxidant, and antiangiogenic effects. According to research, curcumin may prevent mice from developing MAFLD caused by high-fat and high-fructose diets. By regulating the LXR pathway, curcumin inhibits the expression of cytochrome P4503A (CYP3A) and cytochrome P4507A (CYP7A). Additionally, by inhibiting the FAS and Nrf2 pathways, it decreases the expression of CD36, SREBP1c, and the small heterodimer partner (SHP), which decreases hepatic steatosis. In an in vitro study, curcumin was found to reduce the development of liver fat by preventing citrate transport in the AMPK pathway, regulating the aberrant expression of SLC13A5/ACL. This prevents citrate from being carried or broken down. Curcumin inhibits the expression of SREBP1c and the suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS-3), and it increases the phosphorylation of the hepatic activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), preventing liver steatosis. This assists in decreasing hepatic fat accumulation and regulating lipid metabolism [107]. A previous study demonstrated that, by enhancing the expression of the tight junction protein occludin 1, curcumin improved intestinal barrier function in MAFLD mice. The results of this study showed that it inhibited p65 nuclear translocation and NF-θB DNA-binding activity and that it decreased the expression of myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) in the liver, which, in turn, decreased hepatic steatosis [108]. MAFLD development is influenced by PPAR gene methylation. Curcumin significantly reduced methylation levels, elevated PPAR protein expression, and significantly reduced fat storage in MAFLD rats in other studies [109]. Curcumin protects LO2 cells from oleic acid-induced MAFLD by increasing the activity of certain proteins such as pAKT and P13K. Through Nrf2 signaling, it increases the absorption of glucose by liver cells and reduces NO and ROS levels. The initial phases of clinical trials have indicated that an excessive amount of 12 g/day of curcumin is safe for human intake. Because of its high metabolism and insufficient absorption, it has a low bioavailability. Currently, research is being conducted to increase the drug’s bioavailability and make it an unprecedented medication [107].

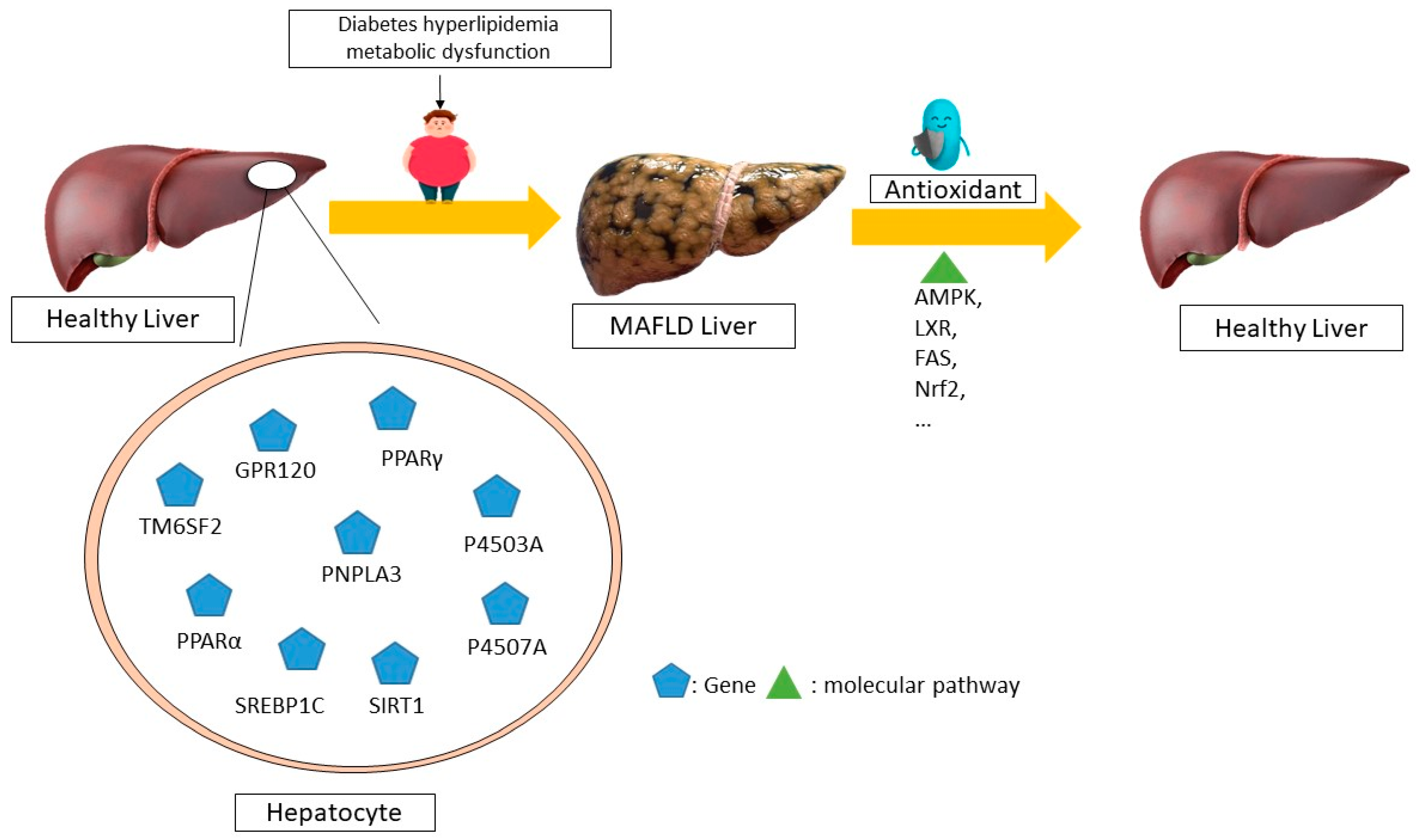

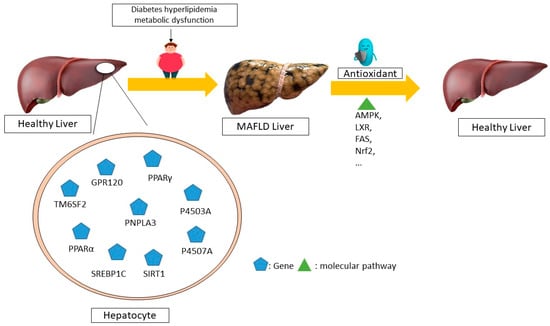

Resveratrol is a phenolic molecule that belongs to the stilbene family of phenols. It has a structure of C6-C2-C6 and is commonly found in plants such as cassia seeds, grape skins, and white tea. The substance comes primarily from the rhizome extract of Polygonum multiflorum. Resveratrol exhibits potent antioxidant, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory properties. Research has shown that resveratrol stimulates the sirtuin pathway (STRT1) for the treatment of MAFLD. Resveratrol reduces fat storage by activating the STRT1-FOXO1 pathway, which prevents SREBPE-1c acetylation and decreases metabolic abnormalities. A reduction in STRT1 levels in hepatocytes can lead to liver inflammation [110]. The stimulation of 3T3-L1 cells with TNF-ɑ leads to an increase in cytokine mRNA expression through the siRNA-mediated activation of SIRT1 [107]. Meanwhile, elevated SIRT1 levels suppress the generation of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as NF-ĸB and TNF-ɑ, thus protecting the liver’s metabolism from the harm caused by a high-fat diet. Research has shown that resveratrol can decrease apoptosis, mitochondrial dysfunction, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in OA-induced L02 cells. It can treat metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) by decreasing caspase-3 and p53 and increasing B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) levels, which helps to reduce liver fat accumulation [111]. The molecular mechanisms of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) mediated by antioxidants in humans is summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The molecular mechanisms underlying the regression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) mediated by antioxidants in humans. Different antioxidants can control the expression of different genes through distinct molecular pathways, leading to the recovery and regression of this disease, according to several human studies. For example, the disease is improved through the AMPK, LXR, FAS, and NRF2 pathways by altering the expression of the SIRT1, P4507A, P4503A, and SREBP1C genes, respectively. MAFLD—metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease; AMPK—AMP-activated protein kinase; LXR—liver X receptors; FAS—FS-7-associated surface; NRF2—nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; SIRT1—sirtuin 1; P4503A—cytochrome P450 3A; GPR120-G-protein-coupled receptor 120; TM6SF2-trans-membrane 6 superfamily member 2; PNPLA3-patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3; PPARα-Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α; P4507A—cytochrome P450 7A; SREBP1C—sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c.

Furthermore, in 4.4% of the studies analyzed, there was no statistically significant impact on patient improvement when antioxidants were used. Furthermore, the reviewed studies also indicated that the efficacy of antioxidant therapy was not significantly influenced by the dosage or duration of treatment.

In the present systematic review, a study of animal research was also conducted. The reviewed animal studies showed that natural antioxidants are thoroughly effective in treating MAFLD (100%), but few studies used this method. This beneficial effect was not consistently seen with synthetic antioxidants, and only 87.8% of the studies showed effective results. On the basis of these data, it can be assumed that antioxidants may be more effective in their natural form than in a synthetic form in treating MAFLD.

Feeding a high-fat diet (HFD) to mice leads to the accumulation and fibrosis of liver collagen. Ascorbic acid supplementation decreases collagen levels and the mRNA expression of TGF-β and collagen. It also inhibits hepatocyte apoptosis and liver injury by increasing Bcl-2 protein levels and decreasing caspase 8. It effectively reduces liver inflammation in obese mice by suppressing the expression of inflammatory genes, including TNFα and MCP-1, in hepatocytes [112].

By controlling the proteins involved in lipid homeostasis, in which CES1 activation plays a crucial role, vitamin E in mice reduces the effects of a high-fat diet on liver lipid accumulation and glucose homeostasis. The biochemical mechanism responsible for the vitamin E-mediated overexpression of CES1 is, at least partially, the activation of nuclear Nrf2 [113].

Quercetin may help HFD-fed mice overcome MAFLD. An HFD causes fat peroxidation, ferroptosis, and fat accumulation; therapy clearly reverses these effects. For example, quercetin inhibits ferroptosis by increasing the expression of anti-glutathione peroxidase four (GPX4) and decreasing the expression of anticyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) and the long-chain family member acyl-coenzyme A synthase four (ACSL4) [114].

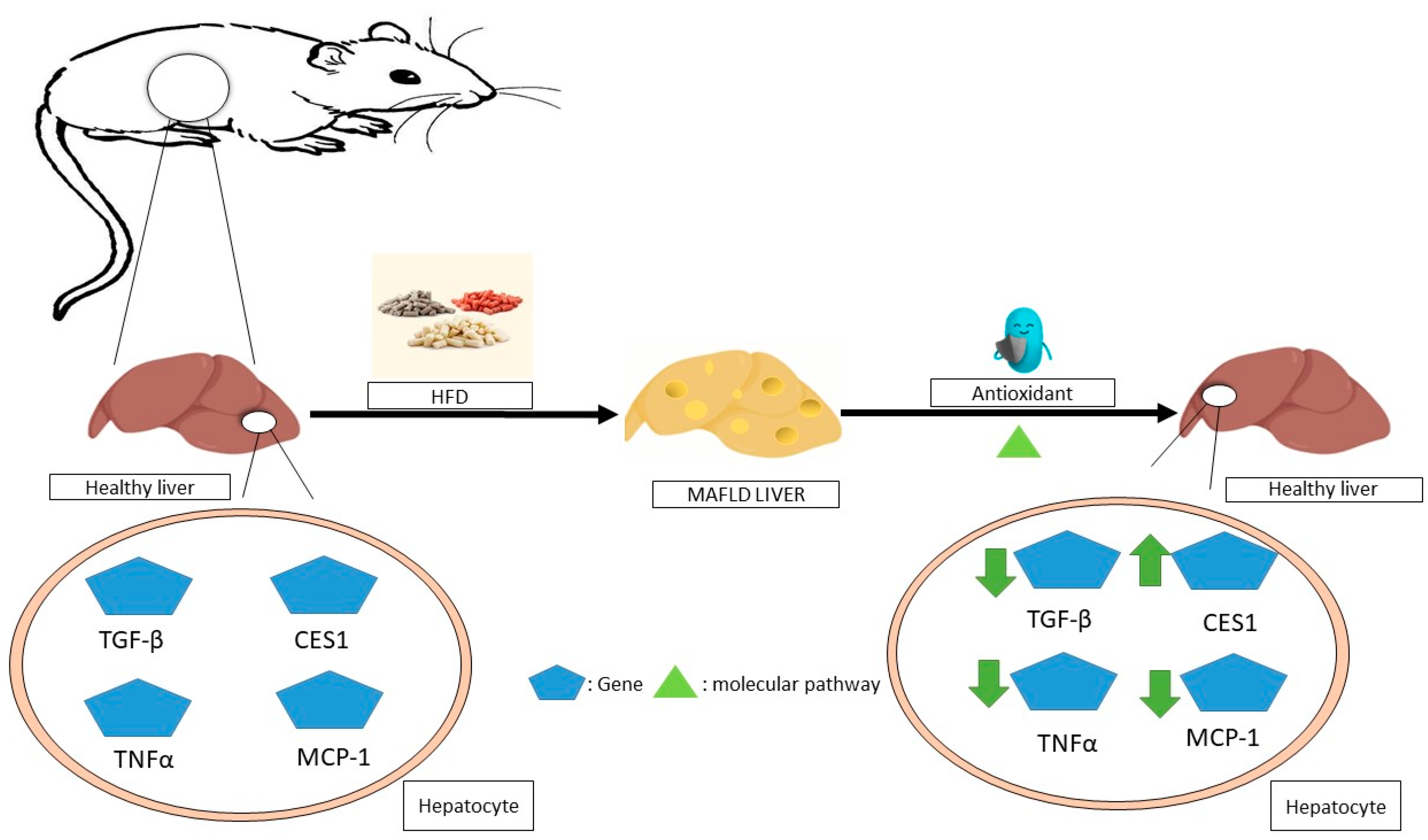

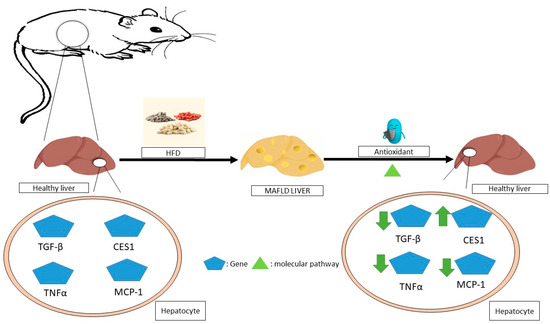

The administration of resveratrol to obese mice improves liver steatosis by improving glycolipid metabolic parameters, liver histology, inflammation, and lipid content. It could potentially have further positive effects by increasing T-SOD and GPX activities, inhibiting TNF-α production, suppressing TLR4 and CD36 expression [115], and improving steatohepatitis through the inhibition of the NF-jB inflammation pathway by further activating the AMPKa-SIRT1 pathway [116]. The molecular mechanisms of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) mediated by antioxidants in animals is summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The molecular mechanisms underlying the regression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) mediated by antioxidants in animals. In animal studies, antioxidants have been shown to improve this disease by affecting the expression of various genes in hepatocytes through molecular pathways, for example, by reducing the expression of inflammatory genes such as TNFα and MCP-1, as well as reducing the expression of TGF-βmRNA or the overexpression of CES1. MAFLD—metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease; TNF-α—tumor necrosis factor alpha; MCP-1—monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; TGF-β—transforming growth factor beta; CES1—carboxylesterase 1.

In general, research examining the impact of antioxidants on the improvement of the condition of patients with MAFLD reveals contradictory results. On the contrary, the observed contradiction related to antioxidant properties in MAFLD therapy could also be attributed to the oxidative impact of antioxidants. Research has shown that, when the concentration of antioxidants in the human body is above the necessary threshold, oxidative effects are increased. In addition, an excess of antioxidants can contribute to elevated levels of oxidative stress [117]. Therefore, despite the positive therapeutic perspective of antioxidant supplements, it is essential to exercise caution and avoid their indiscriminate and/or excessive administration. The cellular intrinsic antioxidant system provides protection against damage caused by oxidants. Therefore, an assessment of the pro-oxidant–antioxidant balance can serve as an effective strategy for the management of antioxidant therapy. Measurement of oxidant and antioxidant capacity has been shown to facilitate the understanding of their balance. As a result, the administration of antioxidants may provide greater efficacy in patients when considering the balance or ratio between pro-oxidants and antioxidants [110,118].

The efficacy of antioxidants as an alternative therapy for MAFLD may be limited due to its multifactorial nature. The use of supplementary treatments based on the patient’s underlying disease, in conjunction with a suitable dose of antioxidants, appears to result in greater efficacy. The concept of combination therapy is interesting because it allows for the simultaneous targeting of multiple pathologic contributors to the disease. In the context of hepatic fibrosis, combination drugs can also be used to address the same target. In this context, these medications may have additive or synergistic effects on the target. Furthermore, the inclusion of a drug can potentially lead to a reduction in the dosage of other medication, thereby improving safety. It should be noted that the inclusion of a drug may reduce the negative consequences associated with an otherwise efficacious drug [119,120]. Furthermore, many fruits and vegetables, such as oranges, contain potassium and calcium, which have the potential to effectively manage blood pressure. On the basis of the evidence mentioned above, it can be inferred that the natural antioxidants present in fruits and vegetables may demonstrate greater effectiveness [104]. It is possible that medicinal supplements contain a combination of ingredients consisting of natural antioxidants that are effective. This study also highlights the absence of other comparable studies investigating the efficacy of antioxidants in preventing MAFLD in at-risk groups.

6. Current Limitations of Knowledge on the Effectiveness of Antioxidants in Treating MAFLD and Their Prospects

Although some evidence suggests the possible advantages of antioxidants for MAFLD, there are still certain issues that need to be clarified. First, because the vast majority of studies had an average duration of less than six months or 1 year, there has been an absence of substantial and outstanding scientific evidence indicating the long-term advantages of MAFLD antioxidant treatment. Second, it is currently questionable whether the general population and specific populations, such as men and women, the elderly, those with diabetes mellitus, children, and adolescents, should be prescribed antioxidant treatment. Third, how does long-term use of this antioxidant treatment affect people’s health? The essential concern is to assess who will benefit the most from an antioxidant treatment for MAFLD based on their personal characteristics, especially those with overlapping health conditions. Fourth, it is challenging to determine consistent findings because the included studies varied according to the characteristics of their study structure, patient demographics, antioxidant types, dosages, and treatment durations. Fifth, confounding variables can affect the results and make it challenging to differentiate between the impact of antioxidants. These variables include differences in the initial characteristics of the study participants, lifestyle factors, and concurrent treatments. Sixth, data analysis may be limited by the variations in the methods used by studies to assess and present outcomes associated with antioxidant levels, metabolic parameters, and liver function.

7. Conclusions

Antioxidants have been indicated to have similar effects on humans and animals. These effects include regulating the SIRT1/AMPK, NFKB, and LXR pathways; decreasing the expression of proapoptotic genes such as BAX, inflammatory genes such as TNF-ɑ, as well as TGF-β and COX2 genes; inhibiting the FAS and NrF2; and activating PPARα. Although natural antioxidants may be beneficial in treating MAFLD patients, combination therapy has been demonstrated to be more effective. However, more research is required to completely comprehend the effect of natural antioxidants. To improve the efficacy of MAFLD treatment, it is essential to take into account two crucial criteria. An effective approach to controlling treatment with antioxidants involves evaluating the appropriate balance between pro-oxidants and antioxidants. In essence, the administration of antioxidants at a suitable dose improves their efficacy, indicating the need for the development of customized therapeutic approaches. Furthermore, it is highly recommended to use the ideal dose of antioxidants in conjunction with other medications, such as antihypertensives, hypoglycemic agents, antidiabetic agents, and other cholesterol-balancing therapies, to effectively treat the underlying condition in patients with MAFLD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K. and A.S.; methodology, S.K. and A.S.; formal analysis, K.M., F.F. and A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M. and F.F.; writing—review and editing, S.K. and A.S.; visualization, K.M., F.F. and S.K.; supervision A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

We used PubMed, SCOPUS, and ScienceDirect databases to screen articles for this review. We did not report any data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

References

- Usman, M.; Bakhtawar, N. Vitamin E as an adjuvant treatment for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Cureus 2020, 12, e9018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abenavoli, L.; Milanović, M.; Milić, N.; Luzza, F.; Giuffrè, A.M. Olive oil antioxidants and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 13, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.M.; Brancati, F.L.; Diehl, A.M. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2002, 122, 1649–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gofton, C.; Upendran, Y.; Zheng, M.-H.; George, J. MAFLD: How is it different from NAFLD? Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2023, 29, S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchay, M.S.; Choudhary, N.S.; Mishra, S.K. Pathophysiological mechanisms underlying MAFLD. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 1875–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Maboud, M.; Menshawy, A.; Menshawy, E.; Emara, A.; Alshandidy, M.; Eid, M. The efficacy of vitamin E in reducing non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2020, 13, 1756284820974917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, J.M.; Cansanção, K.; Perez, R.M.; Leite, N.C.; Padilha, P.; Ramalho, A.; Peres, W. Association between serum and dietary antioxidant micronutrients and advanced liver fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: An observational study. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimini, F.A.; Barchetta, I.; Carotti, S.; Bertoccini, L.; Baroni, M.G.; Vespasiani-Gentilucci, U.; Cavallo, M.G.; Morini, S. Relationship between adipose tissue dysfunction, vitamin D deficiency and the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, R.A.M.; Masroor, A.; Khorochkov, A.; Prieto, J.; Singh, K.B.; Nnadozie, M.C.; Abdal, M.; Shrestha, N.; Mohammed, L. The role of vitamins in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review. Cureus 2021, 13, e16855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Gómez, M.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Trenell, M. Treatment of NAFLD with diet, physical activity and exercise. J. Hepatol. 2017, 67, 829–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassir, F. NAFLD: Mechanisms, treatments, and biomarkers. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, L.; Zou, J.; Ran, W.; Qi, X.; Chen, Y.; Cui, H.; Guo, J. Advancements in the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 13, 1087260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Berndt, C.; Jones, D. Oxidative stress. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 715–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ore, A.; Akinloye, O.A. Oxidative stress and antioxidant biomarkers in clinical and experimental models of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Medicina 2019, 55, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C. Pathogenesis of steatohepatitis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2002, 16, 663–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polimeni, L.; Del Ben, M.; Baratta, F.; Perri, L.; Albanese, F.; Pastori, D.; Violi, F.; Angelico, F. Oxidative stress: New insights on the association of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and atherosclerosis. World J. Hepatol. 2015, 7, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour-Ghanaei, F.; Pourmasoumi, M.; Hadi, A.; Joukar, F. Efficacy of curcumin/turmeric on liver enzymes in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Integr. Med. Res. 2019, 8, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, A.; Crudele, A.; Smeriglio, A.; Braghini, M.R.; Panera, N.; Comparcola, D.; Alterio, A.; Sartorelli, M.R.; Tozzi, G.; Raponi, M.; et al. The anti-inflammatory effects of hydroxytyrosol and vitamin e on paediatric NAFLD. Dig. Liver Dis. 2020, 52, e42–e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khachidze, T. Comparison of the efficacy of Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) versus vitamin E plus vitamin C in non-diabetic patients with nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH). HPB 2019, 21, S398–S399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Anushiravani, A.; Haddadi, N.; Pourfarmanbar, M.; Mohammadkarimi, V. Treatment options for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A double-blinded randomized placebo-controlled trial. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 31, 613–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barchetta, I.; Cimini, F.A.; Cavallo, M.G. Vitamin D and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD): An update. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanyal, A.J.; Chalasani, N.; Kowdley, K.V.; McCullough, A.; Diehl, A.M.; Bass, N.M.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; Lavine, J.E.; Tonascia, J.; Unalp, A.; et al. Pioglitazone, vitamin E, or placebo for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1675–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, T.; Budoff, M.J.; Saab, S.; Ahmadi, N.; Gordon, C.; Guerci, A.D. Atorvastatin and antioxidants for the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: The St Francis Heart Study randomized clinical trial. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2011, 106, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoofnagle, J.H.; Van Natta, M.L.; Kleiner, D.E.; Clark, J.M.; Kowdley, K.V.; Loomba, R.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; Sanyal, A.J.; Tonascia, J. Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network (NASH CRN). Vitamin E and changes in serum alanine aminotransferase levels in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 38, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polyzos, S.A.; Kountouras, J.; Mantzoros, C.S.; Polymerou, V.; Katsinelos, P. Effects of combined low-dose spironolactone plus vitamin E vs vitamin E monotherapy on insulin resistance, non-invasive indices of steatosis and fibrosis, and adipokine levels in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2017, 19, 1805–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pervez, M.A.; Khan, D.A.; Ijaz, A.; Khan, S. Effects of delta-tocotrienol supplementation on liver enzymes, inflammation, oxidative stress and hepatic steatosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 29, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bril, F.; Biernacki, D.M.; Kalavalapalli, S.; Lomonaco, R.; Subbarayan, S.K.; Lai, J.; Tio, F.; Suman, A.; Orsak, B.K.; Hecht, J.; et al. Role of vitamin E for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 1481–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asghari, S.; Asghari-Jafarabadi, M.; Somi, M.-H.; Ghavami, S.-M.; Rafraf, M. Comparison of calorie-restricted diet and resveratrol supplementation on anthropometric indices, metabolic parameters, and serum sirtuin-1 levels in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2018, 37, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chachay, V.S.; Macdonald, G.A.; Martin, J.H.; Whitehead, J.P.; O’Moore-Sullivan, T.M.; Lee, P.; Franklin, M.; Klein, K.; Taylor, P.J.; Ferguson, M.; et al. Resveratrol does not benefit patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 12, 2092–2103.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhao, X.; Ran, L.; Wan, J.; Wang, X.; Qin, Y.; Shu, F.; Gao, Y.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Resveratrol improves insulin resistance, glucose and lipid metabolism in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized controlled trial. Dig. Liver Dis. 2015, 47, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heebøll, S.; Kreuzfeldt, M.; Hamilton-Dutoit, S.; Kjær Poulsen, M.; Stødkilde-Jørgensen, H.; Møller, H.J.; Jessen, N.; Thorsen, K.; Kristina Hellberg, Y.; Bønløkke Pedersen, S.; et al. Placebo-controlled, randomised clinical trial: High-dose resveratrol treatment for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 51, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezeshki, A.; Safi, S.; Feizi, A.; Askari, G.; Karami, F. The effect of green tea extract supplementation on liver enzymes in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 7, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M.; Akhtar, L. Therapeutic benefits of green tea extract on various parameters in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 33, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabatabaee, S.M.; Alavian, S.M.; Ghalichi, L.; Miryounesi, S.M.; Mousavizadeh, K.; Jazayeri, S.; Vafa, M.R. Green tea in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A double blind randomized clinical trial. Hepat. Mon. 2017, 17, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, R.; Nakamura, T.; Torimura, T.; Ueno, T.; Sata, M. Green tea with high-density catechins improves liver function and fat infiltration in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) patients: A double-blind placebo-controlled study. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2013, 32, 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuzawa, Y.; Kapoor, M.P.; Yamasaki, K.; Okubo, T.; Hotta, Y.; Juneja, L.R. Effects of green tea catechins on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) patients. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 9, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, S.; Akhlaghi, M.; Sasani, M.R.; Boldaji, R.B. Olive oil lessened fatty liver severity independent of cardiometabolic correction in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized clinical trial. Nutrition 2019, 57, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofi, F.; Giangrandi, I.; Cesari, F.; Corsani, I.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A. Effects of a 1-year dietary intervention with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid-enriched olive oil on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients: A preliminary study. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010, 61, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shidfar, F.; Bahrololumi, S.S.; Doaei, S.; Mohammadzadeh, A.; Gholamalizadeh, M.; Mohammadimanesh, A. The effects of extra virgin olive oil on alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and ultrasonographic indices of hepatic steatosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients undergoing low calorie diet. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 2018, 1053710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigam, P.; Bhatt, S.; Misra, A.; Chadha, D.S.; Vaidya, M.; Dasgupta, J.; Pasha, Q.M. Effect of a 6-month intervention with cooking oils containing a high concentration of monounsaturated fatty acids (olive and canola oils) compared with control oil in male Asian Indians with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2014, 16, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueto-Galán, R.; Barón, F.J.; Valdivielso, P.; Pintó, X.; Corbella, E.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Wärnberg, J.; los investigadores del Estudio PREDIMED. Changes in fatty liver index after consuming a Mediterranean diet: 6-year follow-up of the PREDIMED-Malaga trial. Med. Clínica (Engl. Ed.) 2017, 148, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontogianni, M.D.; Tileli, N.; Margariti, A.; Georgoulis, M.; Deutsch, M.; Tiniakos, D.; Fragopoulou, E.; Zafiropoulou, R.; Manios, Y.; Papatheodoridis, G. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with the severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 33, 678–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, M.C.; Itsiopoulos, C.; Thodis, T.; Ward, G.; Trost, N.; Hofferberth, S.; O’Dea, K.; Desmond, P.V.; Johnson, N.A.; Wilson, A.M. The Mediterranean diet improves hepatic steatosis and insulin sensitivity in individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2013, 59, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trovato, F.M.; Catalano, D.; Martines, G.F.; Pace, P.; Trovato, G.M. Mediterranean diet and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: The need of extended and comprehensive interventions. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 34, 86–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.F.; Fan, S.H.; Zheng, Y.L.; Lu, J.; Wu, D.M.; Shan, Q.; Hu, B. Troxerutin improves hepatic lipid homeostasis by restoring NAD+-depletion-mediated dysfunction of lipin 1 signaling in high-fat diet-treated mice. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014, 91, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suda, I.; Ishikawa, F.; Hatakeyama, M.; Miyawaki, M.; Kudo, T.; Hirano, K.; Ito, A.; Yamakawa, O.; Horiuchi, S. Intake of purple sweet potato beverage affects on serum hepatic biomarker levels of healthy adult men with borderline hepatitis. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 62, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faghihzadeh, F.; Adibi, P.; Rafiei, R.; Hekmatdoost, A. Resveratrol supplementation improves inflammatory biomarkers in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutr. Res. 2014, 34, 837–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiuso, P.; Scognamiglio, I.; Murolo, M.; Ferranti, P.; De Simone, C.; Rizzo, M.R.; Tuccillo, C.; Caraglia, M.; Loguercio, C.; Federico, A. Serum oxidative stress markers and lipidomic profile to detect NASH patients responsive to an antioxidant treatment: A pilot study. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 169216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loguercio, C.; Andreone, P.; Brisc, C.; Brisc, M.C.; Bugianesi, E.; Chiaramonte, M.; Cursaro, C.; Danila, M.; de Sio, I.; Floreani, A.; et al. Silybin combined with phosphatidylcholine and vitamin E in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized controlled trial. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 52, 1658–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solhi, H.; Ghahremani, R.; Kazemifar, A.M.; Yazdi, Z.H. Silymarin in treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: A randomized clinical trial. Casp. J. Intern. Med. 2014, 5, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Soleimani, D.; Paknahad, Z.; Rouhani, M.H. Therapeutic effects of garlic on hepatic steatosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients: A randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2020, 13, 2389–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangouni, A.A.; Azar, M.R.M.H.; Alizadeh, M. Effect of garlic powder supplementation on hepatic steatosis, liver enzymes and lipid profile in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A double-blind randomised controlled clinical trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 124, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-N.; Kang, S.-G.; Roh, Y.K.; Choi, M.-K.; Song, S.-W. Efficacy and safety of fermented garlic extract on hepatic function in adults with elevated serum gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase levels: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 1993–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Gu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, L.; Lu, M.; Meng, G.; Yao, Z.; Wu, H.; Xia, Y.; et al. Association between dietary raw garlic intake and newly diagnosed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A population-based study. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 181, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emamat, H.; Farhadnejad, H.; Tangestani, H.; Saneei Totmaj, A.; Poustchi, H.; Hekmatdoost, A. Association of allium vegetables intake and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease risk: A case-control study. Nutr. Food Sci. 2020, 50, 1075–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loffredo, L.; Baratta, F.; Ludovica, P.; Battaglia, S.; Carnevale, R.; Nocella, C.; Novo, M.; Pannitteri, G.; Ceci, F.; Angelico, F.; et al. Effects of dark chocolate on endothelial function in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 28, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafie, R.; Hosseini, S.A.; Hajiani, E.; Saki Malehi, A.; Mard, S.A. Effect of ginger powder supplementation in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 2020, 13, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshi-Maskooni, M.; Keshavarz, S.A.; Qorbani, M.; Mansouri, S.; Alavian, S.M.; Badri-Fariman, M.; Jazayeri-Tehrani, S.A.; Sotoudeh, G. Green cardamom supplementation improves serum irisin, glucose indices, and lipid profiles in overweight or obese non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients: A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimlou, M.; Yari, Z.; Hekmatdoost, A.; Alavian, S.M.; Keshavarz, S.A. Ginger supplementation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Hepat. Mon. 2016, 16, e34897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anty, R.; Marjoux, S.; Iannelli, A.; Patouraux, S.; Schneck, A.S.; Bonnafous, S.; Gire, C.; Amzolini, A.; Ben-Amor, I.; Saint-Paul, M.C.; et al. Regular coffee but not espresso drinking is protective against fibrosis in a cohort mainly composed of morbidly obese European women with NAFLD undergoing bariatric surgery. J. Hepatol. 2012, 57, 1090–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelber-Sagi, S.; Salomone, F.; Webb, M.; Lotan, R.; Yeshua, H.; Halpern, Z.; Santo, E.; Oren, R.; Shibolet, O. Coffee consumption and nonalcoholic fatty liver onset: A prospective study in the general population. Transl. Res. 2015, 165, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, X.; Wang, H. Silymarin attenuated hepatic steatosis through regulation of lipid metabolism and oxidative stress in a mouse model of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Am. J. Transl. Res. 2016, 8, 1073. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mengesha, T.; Gnanasekaran, N.; Mehare, T. Hepatoprotective effect of silymarin on fructose induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in male albino wistar rats. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2021, 21, 104. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, R.; Xu, D.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, B.; Aa, J.; Wang, G.; Xie, Y. Silybin ameliorates hepatic lipid accumulation and modulates global metabolism in an NAFLD mouse model. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 123, 109721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.Y.; Jiang, N.; Yang, J.; Tu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Xiao, X.; Dong, Y. Silybum marianum oil attenuates hepatic steatosis and oxidative stress in high fat diet-fed mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 100, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Q.; Weng, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, J.; Wu, X. Silybin alleviates hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in NASH mice by inhibiting oxidative stress and involvement with the Nf-κB pathway. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2018, 63, 3398–3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.H.; Chao, J.; Chang, M.L.; Peng, W.H.; Cheng, H.Y.; Liao, J.W.; Pao, L.H. Pentoxifylline ameliorates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in hyperglycaemic and dyslipidaemic mice by upregulating fatty acid β-oxidation. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massart, J.; Robin, M.A.; Noury, F.; Fautrel, A.; Lettéron, P.; Bado, A.; Eliat, P.A.; Fromenty, B. Pentoxifylline aggravates fatty liver in obese and diabetic ob/ob mice by increasing intestinal glucose absorption and activating hepatic lipogenesis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 165, 1361–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, A.; Bartuzi, P.; Heegsma, J.; Dekker, D.; Kloosterhuis, N.; de Bruin, A.; Jonker, J.W.; van de Sluis, B.; Faber, K.N. Impaired hepatic vitamin A metabolism in NAFLD mice leading to vitamin A accumulation in hepatocytes. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 11, 309–325.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipsen, D.H.; Skat-Rørdam, J.; Svenningsen, M.; Andersen, M.; Latta, M.; Buelund, L.E.; Lintrup, K.; Skaarup, R.; Lykkesfeldt, J.; Tveden-Nyborg, P. The effect of acetylsalicylic acid and pentoxifylline in guinea pigs with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2021, 128, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.P.; Gayotto, L.C.; Tatai, C.; Della Nina, B.I.; Lima, E.S.; Abdalla, D.S.; Lopasso, F.P.; Laurindo, F.R.; Carrilho, F.J. Vitamin C and vitamin E in prevention of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in choline deficient diet fed rats. Nutr. J. 2003, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.W.; Huang, C.C.; Hsu, C.F.; Li, T.H.; Tsai, Y.L.; Lin, M.W.; Tsai, H.C.; Huang, S.F.; Yang, Y.Y.; Hsieh, Y.C.; et al. SIRT1-dependent mechanisms and effects of resveratrol for amelioration of muscle wasting in NASH mice. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2020, 7, e000381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimian, G.; Kirschbaum, M.; Veldhuis, Z.J.; Bomfati, F.; Porte, R.J.; Lisman, T. Vitamin E attenuates the progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease caused by partial hepatectomy in mice. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presa, N.; Clugston, R.D.; Lingrell, S.; Kelly, S.E.; Merrill, A.H., Jr.; Jana, S.; Kassiri, Z.; Gómez-Muñoz, A.; Vance, D.E.; Jacobs, R.L.; et al. Vitamin E alleviates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase deficient mice. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Basis Dis. 2019, 1865, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.W.; Baek, S.M.; Kang, K.K.; Lee, A.R.; Kim, T.U.; Choi, S.K.; Roh, Y.S.; Hong, I.H.; Park, S.J.; Kim, T.H.; et al. Vitamin C deficiency inhibits nonalcoholic fatty liver disease progression through impaired de novo lipogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 2021, 191, 1550–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Q.; Zhao, L.; Meng, C.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Y.; Shi, R.; Han, X.; Wang, T.; Li, J. Prophylactic and therapeutic effects of different doses of vitamin C on high-fat-diet-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 131, 110792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milton-Laskibar, I.; Marcos-Zambrano, L.J.; Gómez-Zorita, S.; Fernández-Quintela, A.; Carrillo de Santa Pau, E.; Martínez, J.A.; Portillo, M.P. Gut microbiota induced by pterostilbene and resveratrol in high-fat-high-fructose fed rats: Putative role in steatohepatitis onset. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Gu, Y.; Glisan, S.L.; Lambert, J.D. Dietary cocoa ameliorates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and increases markers of antioxidant response and mitochondrial biogenesis in high fat-fed mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2021, 92, 108618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda, D.; Elshopakey, G.E.; Risha, E.F.; El-Boshy, M.E.; Abdelhamid, F.M. Vitamin D3 alleviates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in rats by inhibiting hepatic oxidative stress and inflammation via the SREBP-1-c/PPARα-NF-κB/IR-S2 signaling pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1164512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEIFEL-DINSH; Sabra, A.-N.A.; Hammam, O.A.; Ebeid, F.A.; El-Lakkany, N.M. Pharmacological and antioxidant actions of garlic and/or onion in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in rats. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 2014, 44, 295–308. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.-H.; Hwang, S.-J.; Lim, D.-W.; Son, C.-G. Cynanchum atratum alleviates non-alcoholic fatty liver by balancing lipogenesis and fatty acid oxidation in a high-fat, high-fructose diet mice model. Cells 2021, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liao, X.; Meng, F.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Guo, F.; Li, X.; Meng, M.; Li, Y.; Sun, C. Therapeutic role of ursolic acid on ameliorating hepatic steatosis and improving metabolic disorders in high-fat diet-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease rats. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Ou, Y.; Hu, G.; Wen, C.; Yue, S.; Chen, C.; Xu, L.; Xie, J.; Dai, H.; Xiao, H.; et al. Naringenin attenuates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by down-regulating the NLRP3/NF-κB pathway in mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 1806–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Yu, Y.; Ding, L.; Xu, P.; Wang, Y. Matcha green tea alleviates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in high-fat diet-induced obese mice by regulating lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, J.; Huo, T.I.; Cheng, H.Y.; Tsai, J.C.; Liao, J.W.; Lee, M.S.; Qin, X.M.; Hsieh, M.T.; Pao, L.H.; Peng, W.H. Gallic acid ameliorated impaired glucose and lipid homeostasis in high fat diet-induced NAFLD mice. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Zhao, X.; Liu, M.; Zhao, H.; Sun, Y. Lycopene prevents non-alcoholic fatty liver disease through regulating hepatic NF-κB/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway and intestinal microbiota in mice fed with high-fat and high-fructose diet. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1120254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, M.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, S.; Fan, S.; Yang, L.; Tong, Q.; Ji, G.; Huang, C. Betulinic acid alleviates endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated nonalcoholic fatty liver disease through activation of farnesoid X receptors in mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 847–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, D.; Yang, L.; Pang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Li, K.; Rong, X.; Guo, J. Tianhuang formula reduces the oxidative stress response of NAFLD by regulating the gut microbiome in mice. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 984019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acedo, S.C.; Gotardo, É.M.F.; Pereira, J.A.; Pedrazzoli, J.; Ribeiro, M.L.; Gambero, A. Role of pentoxifylline in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in high-fat diet-induced obesity in mice. World J. Hepatol. 2015, 7, 2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, S.K.; Poudyal, H.; Brown, L. Quercetin ameliorates cardiovascular, hepatic, and metabolic changes in diet-induced metabolic syndrome in rats. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1026–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcolin, E.; San-Miguel, B.; Vallejo, D.; Tieppo, J.; Marroni, N.; González-Gallego, J.; Tuñón, M.J. Quercetin Treatment Ameliorates Inflammation and Fibrosis in Mice with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis, 3. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1821–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panchal, S.K.; Poudyal, H.; Arumugam, T.V.; Brown, L. Rutin attenuates metabolic changes, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and cardiovascular remodeling in high-carbohydrate, high-fat diet-fed rats. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 1062–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suguro, R.; Pang, X.-C.; Yuan, Z.-W.; Chen, S.-Y.; Zhu, Y.-Z.; Xie, Y. Combinational applicaton of silybin and tangeretin attenuates the progression of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) in mice via modulating lipid metabolism. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 151, 104519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzu, N.; Bahcecioglu, I.H.; Dagli, A.F.; Ozercan, I.H.; Ustündag, B.; Sahin, K. Epigallocatechin gallate attenuates experimental non-alcoholic steatohepatitis induced by high fat diet. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008, 23 Pt 2, e465–e470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Q.Q.; Li, B.Y.; Meng, J.M.; Gan, R.Y.; Xu, X.Y.; Gu, Y.Y.; Wang, X.H.; Li, H.B. Effects of several tea extracts on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice fed with a high-fat diet. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 2954–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, D.D.; Mao, Q.Q.; Li, B.Y.; Saimaiti, A.; Huang, S.Y.; Xiong, R.G.; Shang, A.; Luo, M.; Li, H.Y.; Gan, R.Y.; et al. Effects of different green teas on obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease induced by a high-fat diet in mice. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 929210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, J.; Sun, P.; Yi, R.; Han, X.; Zhao, X. Raw bowl tea (Tuocha) polyphenol prevention of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by regulating intestinal function in mice. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.Y.; Huang, S.Y.; Zhou, D.D.; Xiong, R.G.; Luo, M.; Saimaiti, A.; Han, M.K.; Gan, R.Y.; Zhu, H.L.; Li, H.B. Theabrownin inhibits obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice via serotonin-related signaling pathways and gut-liver axis. J. Adv. Res. 2023, 52, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Mao, Q.; Xiong, R.; Zhou, D.; Huang, S.; Saimaiti, A.; Shang, A.; Luo, M.; Li, H.; Li, H.; et al. Preventive effects of different black and dark teas on obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and modulate gut microbiota in high-fat diet fed mice. Foods 2022, 11, 3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, L.; Cogliati, B.; Otton, R. Green tea prevents NAFLD by modulation of miR-34a and miR-194 expression in a high-fat diet mouse model. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 4168380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, M.; Jafari, B.; Hekmatdoost, A. Pomegranate juice prevents development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in rats by attenuating oxidative stress and inflammation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 2327–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Lakkany, N.M.; El-Din, S.H.S.; Sabra, A.-N.A.-A.; Hammam, O.A.; Ebeid, F.A.-L. Co-administration of metformin and N-acetylcysteine with dietary control improves the biochemical and histological manifestations in rats with non-alcoholic fatty liver. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 11, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seif El-Din, S.H.; El-Lakkany, N.M.; El-Naggar, A.A.; Hammam, O.A.; Abd El-Latif, H.A.; Ain-Shoka, A.A.; Ebeid, F.A. Effects of rosuvastatin and/or β-carotene on non-alcoholic fatty liver in rats. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 10, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chiu, H.-F.; Venkatakrishnan, K.; Golovinskaia, O.; Wang, C.-K. Impact of micronutrients on hypertension: Evidence from clinical trials with a special focus on meta-analysis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, L.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Nan, Y.; Qiao, L. Role of nutrition, gene polymorphism, and gut microbiota in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Discov. Med. 2017, 24, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ezhilarasan, D.; Lakshmi, T. A molecular insight into the role of antioxidants in nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 9233650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Song, J.; Zhou, K.; Zi, X.; Sun, B.; Bao, H.; Li, L. Molecular mechanism pathways of natural compounds for the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Molecules 2023, 28, 5645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, D.; Zou, J.; Su, D.; Mai, H.; Zhang, S.; Li, P.; Zheng, X. Curcumin prevents high-fat diet-induced hepatic steatosis in ApoE−/− mice by improving intestinal barrier function and reducing endotoxin and liver TLR4/NF-κB inflammation. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 16, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Y.; Tang, D.; Du, Y.L.; Cao, C.Y.; Nie, Y.Q.; Cao, J.; Zhou, Y.J. Fatty liver mediated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α DNA methylation can be reversed by a methylation inhibitor and curcumin. J. Dig. Dis. 2018, 19, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purushotham, A.; Schug, T.T.; Xu, Q.; Surapureddi, S.; Guo, X.; Li, X. Hepatocyte-specific deletion of SIRT1 alters fatty acid metabolism and results in hepatic steatosis and inflammation. Cell Metab. 2009, 9, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Zhang, M.; Wang, C.; Li, B.; Li, L.; Ye, F.; Xu, C. Resveratrol Attenuates High-Fat Diet–Induced Hepatic Lipotoxicity by Upregulating Bmi-1 Expression. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2022, 381, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, C.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, X.; Gao, M.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Fang, F.; et al. Retinoic acid ameliorates high-fat diet-induced liver steatosis through sirt1. Sci. China Life Sci. 2017, 60, 1234–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, W.; Xu, Y.; Ren, X.; Xiang, D.; Lei, K.; Zhang, C.; Liu, D. Vitamin E ameliorates lipid metabolism in mice with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease via Nrf2/CES1 signaling pathway. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2019, 64, 3182–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.-J.; Zhang, G.-F.; Zheng, J.-Y.; Sun, J.-H.; Ding, S.-B. Targeting mitochondrial ROS-mediated ferroptosis by quercetin alleviates high-fat diet-induced hepatic lipotoxicity. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 876550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, K.; Song, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Wang, C.; Zhang, L.; Wang, T. The therapeutic effects of resveratrol on hepatic steatosis in high-fat diet-induced obese mice by improving oxidative stress, inflammation and lipid-related gene transcriptional expression. Med. Mol. Morphol. 2019, 52, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Ma, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, L.; Xu, J.; Wang, K.; Li, D. Resveratrol supplement inhibited the NF-κB inflammation pathway through activating AMPKα-SIRT1 pathway in mice with fatty liver. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2016, 422, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamdari, D.H.; Paletas, K.; Pegiou, T.; Sarigianni, M.; Befani, C.; Koliakos, G. A novel assay for the evaluation of the prooxidant–antioxidant balance, before and after antioxidant vitamin administration in type II diabetes patients. Clin. Biochem. 2007, 40, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keramat, S.; Sharebiani, H.; Patel, M.; Fazeli, B.; Stanek, A. The Potential Role of Antioxidants in the Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Disease: A Systematic Review. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makri, E.S.; Makri, E.; Polyzos, S.A. Combination therapies for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharebiani, H.; Keramat, S.; Chavoshan, A.; Fazeli, B.; Stanek, A. The influence of antioxidants on oxidative stress-induced vascular aging in obesity. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).