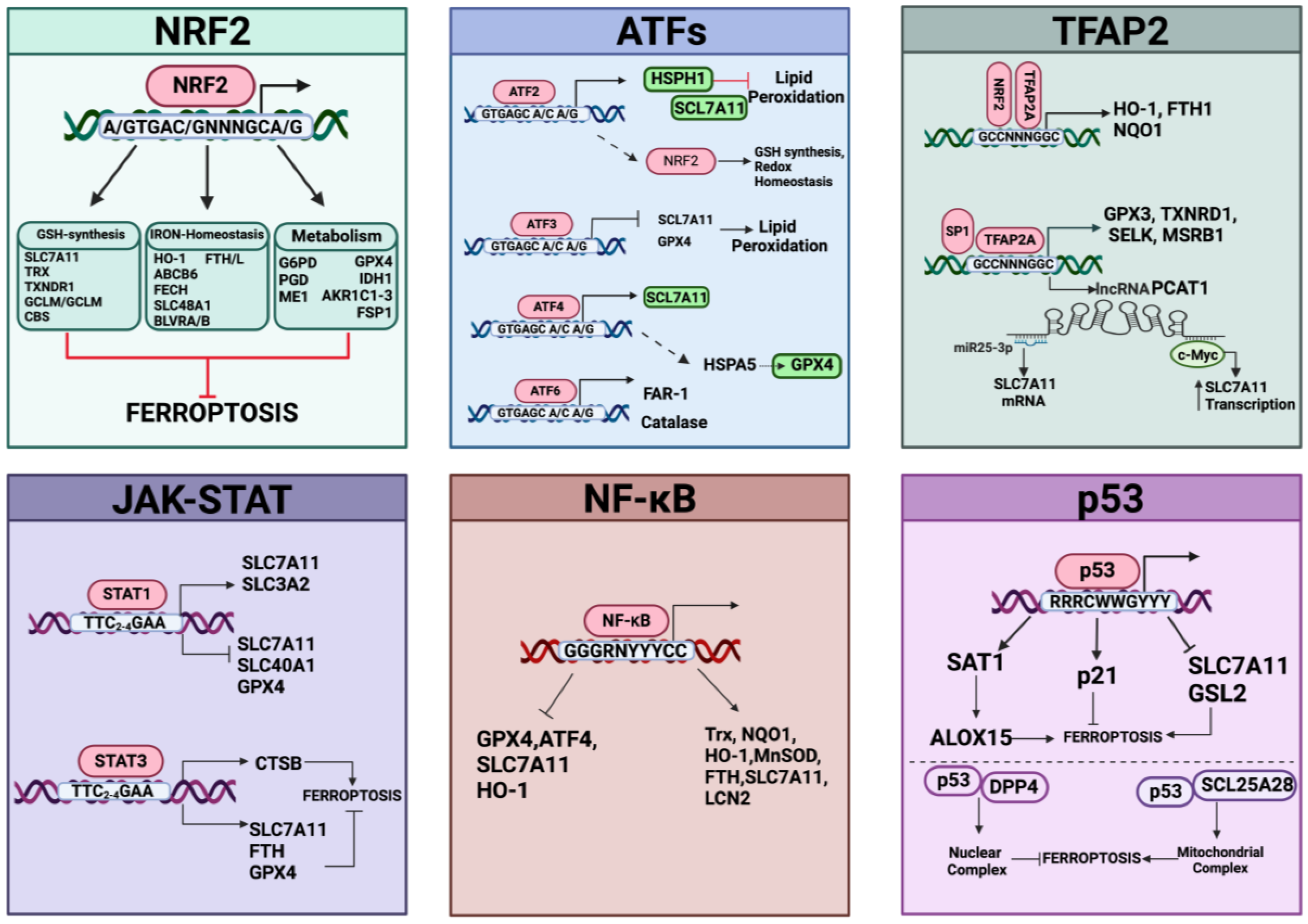

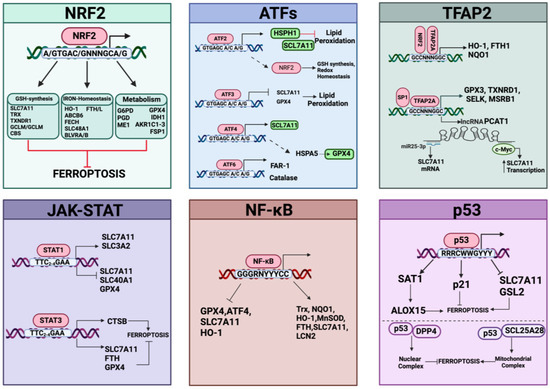

Abstract

Ferroptosis is a type of programmed cell death that differs from apoptosis, autophagy, and necrosis and is related to several physio-pathological processes, including tumorigenesis, neurodegeneration, senescence, blood diseases, kidney disorders, and ischemia–reperfusion injuries. Ferroptosis is linked to iron accumulation, eliciting dysfunction of antioxidant systems, which favor the production of lipid peroxides, cell membrane damage, and ultimately, cell death. Thus, signaling pathways evoking ferroptosis are strongly associated with those protecting cells against iron excess and/or lipid-derived ROS. Here, we discuss the interaction between the metabolic pathways of ferroptosis and antioxidant systems, with a particular focus on transcription factors implicated in the regulation of ferroptosis, either as triggers of lipid peroxidation or as ferroptosis antioxidant defense pathways.

1. Introduction

In about ten years of research investigations, ferroptosis emerged as a type of cell death with a pivotal role in preventing or even facilitating the progression of many diseases (reviewed in [1,2,3]). In particular, ferroptosis is now considered a good therapeutic option to treat multiple forms of cancer and arrest tumor growth [3,4,5], as well as a causal factor in neurodegenerative disorders [6], senescence/aging [7], different blood diseases [8], and kidney- and ischemia-reperfusion injuries [9,10].

Ferroptosis has been recognized as a type of regulated, iron-dependent cell death with distinct morphologic features and molecular mechanisms differing from other forms of regulated dying pathways like apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy-induced cell death [11]. In fact, ferroptosis is a programmed cell death that occurs when lipid peroxides accumulate because of a loss of redox homeostasis; thus, the control of lipid peroxidation represents the main regulator of ferroptosis (reviewed in [12]). Metabolic pathways triggering increased redox-reactive molecules like iron, reactive oxygen species (ROS)/reactive nitrogen species (RNS), enzymatic lipid peroxidation, and failure of endogenous antioxidant systems, mainly glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4)/glutathione (GSH) and coenzyme Q, can fuel ferroptosis [13]. Although the molecular mechanisms and/or metabolic pathways are still poorly understood, ferroptosis seem to be under the control of numerous transcription factors [14,15], with most of them acting as transcriptional modulators of genes implicated in lipid peroxidation and redox homeostasis, as well as iron levels.

Aim: To highlight the relationships among oxidative stress, regulatory pathways, and ferroptosis.

2. Ferroptosis as a Biological Program: Features and General Mechanisms

Beginning with the identification of apoptosis, the archetypal example of “programmed cell death,” many non-apoptotic cell death pathways, including several regulated necrotic pathways such as necroptosis, disulfidptosis, netosis, entosis, and crupoptosis, have been identified in recent years [16,17]. Although ROS and RNS are crucial in most types of cell death, it is only now becoming clear how they regulate and characterize the specific type of cell death that takes place in any given cell [18,19]. Indeed, since cellular signaling and stress response are ROS-dependent processes, it is not surprising that cell death pathways are dependent on the type and quantity of ROS/RNS production, which can function as a rheostat, enabling the activation of various cell death pathways and possibly cross-talks with other forms of cell death. As a type of non-apoptotic cell death, ferroptosis is a ROS/RNS-dependent cell death caused by the imbalance of three metabolic pillars: thiols, polyunsaturated phospholipids, and iron [20].

2.1. Role of Iron in Ferroptosis

Even though iron is necessary for cell division and survival, its accumulation combined with an increase in lipid-derived radicals and lipid peroxides may cause cell death [11]. Notably, in this context, the catalytic activity of enzymes involved in both ROS formation (lipoxygenases/LOXs, cytochrome P450/CYPs, xanthine oxidase, NADPH oxidases, mitochondrial complex I and III) and decomposition (catalase, peroxidases) relies on loosely bound iron or iron-complexes (i.e., heme or [Fe-S] clusters).

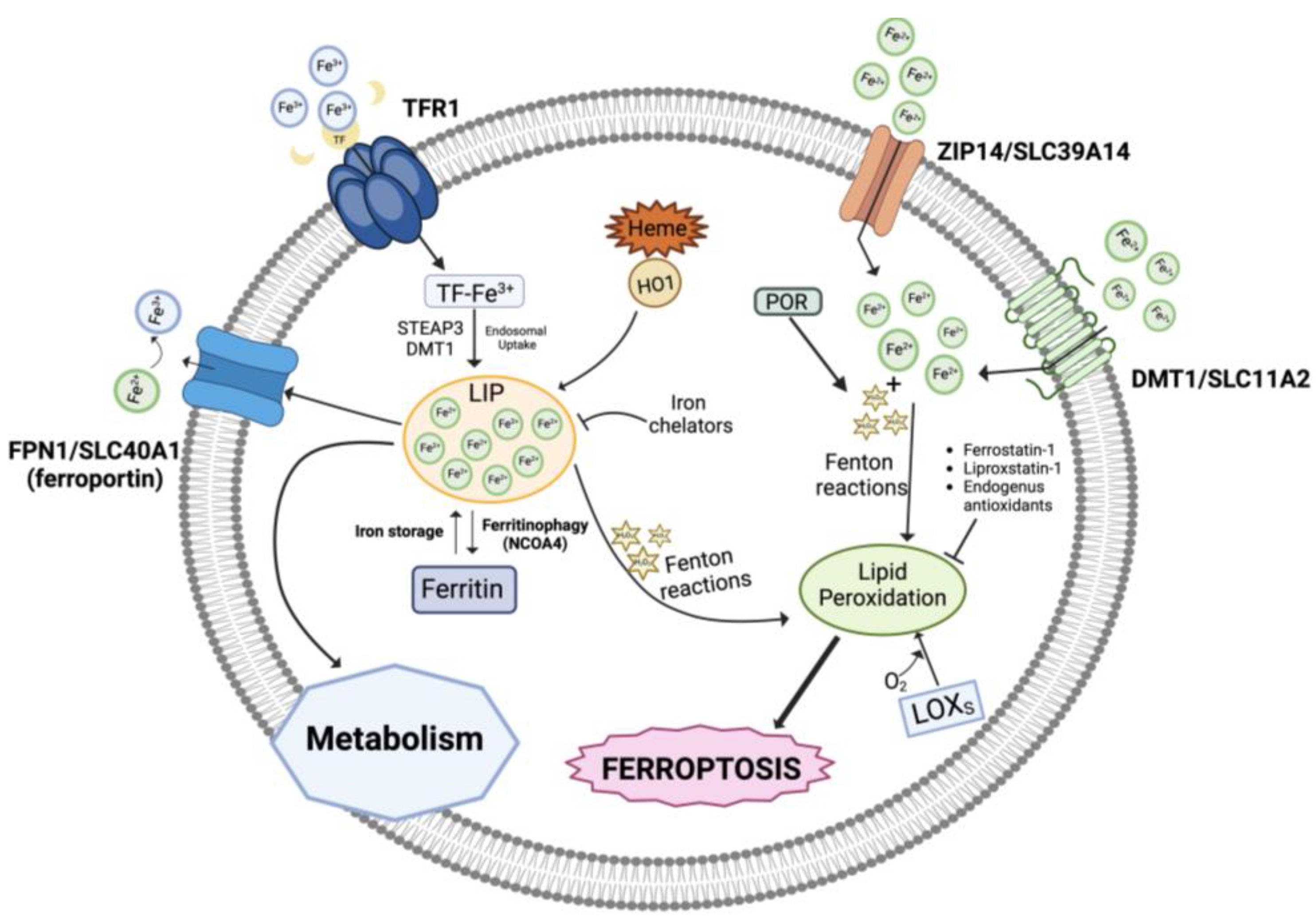

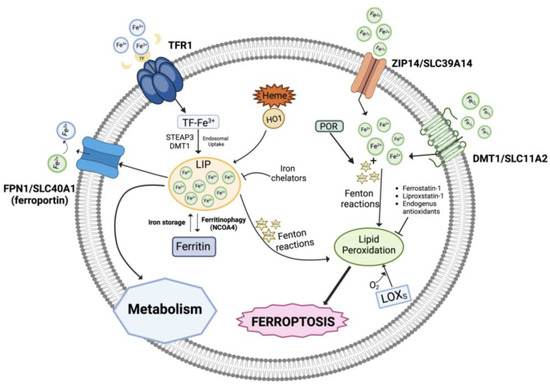

Three pools of iron are most likely representative of the iron species thought to be directly involved in ferroptosis: (i) the first one includes catalytic centers of non-heme iron proteins like LOXs utilizing iron at the active site; (ii) the storage iron pool represented by ferritin, and (iii) the major fraction represented by the redox-active, non-coordinated Fe2+ present in the cytosolic labile iron pool (LIP) that can be transported into mitochondria and utilized for heme and iron-sulfur cluster synthesis (Figure 1). Lysosomes have a very large LIP because of their role in recycling endogenous iron sources like mitochondria and ferritin and in absorbing exogenous iron. Interestingly, it has recently been reported that ferroptosis in cancer cells cannot occur unless functional lysosomes are present [21,22].

Figure 1.

Role of iron in ferroptosis. An overview of the iron metabolism showing the transport mechanisms, storage, and intracellular metabolism. LIP, labile iron pool; TFR1, transferrin receptor 1; HO-1, heme oxygenase 1; POR, NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase; LOXs, lipoxygenases. Created with BioRender.com (accessed on 31 January 2024).

In addition, intracellular iron overload can be related to dysregulated levels of several proteins involved in iron metabolism/homeostasis including transferrin, the carrier of blood ferric iron (Fe3+); transferrin receptor 1 (TFR1), which is the primary iron importer into the endosomal compartment; DMT1 (divalent metal transporter 1), which releases iron into the cytoplasmatic iron-labile pool after it has been reduced to ferrous iron Fe2+ by ferrireductases (e.g., STEAP3); ZIP14, mediating non-transferrin-bound iron import; ferritin, which stores iron; and the iron exporter ferroportin (FPN1) [23,24]. Also, autophagic degradation of ferritin (ferritinophagy), the intracellular LIP, and heme degradation by the inducible enzyme heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) generates iron, in addition to carbon monoxide (CO) and biliverdin [25,26,27,28].

Notably, autophagy is basically a recycling pathway that can lead to cell death when it becomes disturbed [29]. An example of iron transport protein dysregulation that results in iron overload is seen in ferroptosis-sensitive Ras-mutant cells, which have elevated TFR1 and decreased ferritin levels [30]. Notably, during ferroptosis, the genes related to iron metabolism are mostly upregulated and numerous transcription factors are implicated in such control (reviewed in [31,32]).

Under physiological conditions, the ferrous iron of the LIP pool is kinetically unstable, therefore extremely reactive, and can catalyze Fenton reactions, which decompose endogenously produced hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) into highly reactive intermediate species, like hydroxyl and peroxyl radicals (HO•, HOO•) or high-valence oxo-ferryl species [33]:

Fe2+ + H2O2 → Fe3++ HO• + OH−

Fe3+ + H2O2 → Fe2++ HOO• + H+

high-valence oxo-ferryl species

Several cellular components, particularly phospholipids containing polyunsaturated fatty acid chains (PUFAs), are expected to be attacked and oxidatively damaged by the Fenton-derived ROS species, which will eventually cause lipid hydroperoxides or other hydroperoxides to become active, causing damage to membranes and other intracellular structures, thereby triggering cell death processes [34]. Additionally, it is possible that the iron centers of LOX enzymes catalyze the production of hydroperoxyl lipids (LOOH), the primary enzymatic products of lipid peroxidation, while Fe2+ from the LIP takes part in the secondary reactions of LOOH decomposition to create electrophilic products of lipid peroxidation that are oxidatively truncated [20,35,36].

2.2. Iron Accumulation and Lipid Peroxidation

The induction of ferroptosis employes specific pathways involving redox active iron and/or iron-dependent peroxidation enzymes. Iron is a fundamental cofactor for several enzymes involved in oxidation–reduction reactions due to its ability to exist in two ionic forms: ferrous (Fe2+) and ferric (Fe3+) iron. As mentioned before, in the ferroptosis context, the enzymes that catalyze lipid peroxidation are mostly heme or non-heme iron enzymes [37,38]. Consequently, iron homeostasis plays a crucial role in lipid peroxidation.

Lipids are essential components of cell membranes that maintain the structure and control the function of cells. The cellular lipid composition and the related mechanisms by which the cell imports, synthesizes, stores, and catabolizes different lipids crucially shape ferroptosis sensitivity [39,40]. In more detail, the type of unsaturated phospholipids in the cell membrane determines how cells are sensitive to ferroptosis, with PUFAs increasing the sensitivity of cells to ferroptosis whereas monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) have inhibitory effects toward this cell death process [39,41].

PUFAs are a family of lipids with two or more double bounds that can be classified in omega-3 (n-3) and omega-6 (n-6) fatty acids (FAs), according to the location of the final double bond relative to the molecule’s terminal methyl terminus. The principal n-6 FAs are linoleic acid (C18:2), arachidonic acid (AA, C20:4), and its elongation product, adrenic acid (AdA, C22:4). PUFAs are important substrates for unsaturated phospholipid synthesis and also for the generation of lipid peroxides, mostly when they are incorporated into phosphatidylethanolamines (PE) [42]. The activation and esterification of AA and AdA into PE is carried out by specific enzymes, namely the acyl-coenzyme A (CoA) synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) and lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3), rendering the ACSL4/LPCAT3 axis the principal pro-ferroptotic system that under iron overload conditions can push lipid nonenzymatic autoxidation reactions or eventually increase lipoxygenase activities (as discussed later in detail).

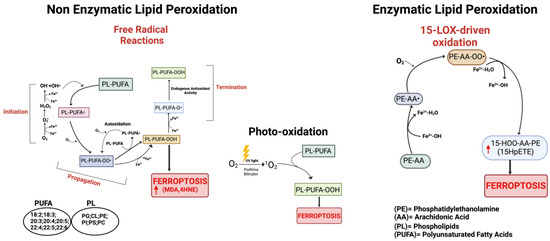

Lipid peroxidation (Figure 2) relies on the reaction of oxygen-derived free radicals with PUFAs, resulting in lipid peroxyl radicals and hydroperoxides. The conversion of PUFAs incorporated into membrane phospholipids to peroxide PUFAs represents the initiation step to drive ferroptotic cell death [12]. Once formed, lipid peroxides can interact with ferrous iron to generate peroxyl radicals that can then abstract hydrogens from neighboring acyl chains in the lipid membrane environment to propagate the lipid peroxidation process. As mentioned before, specific PUFAs like arachidonic acid and adrenic acid are peroxidized to drive ferroptosis; however, other PUFA-containing phospholipids, including various diacyl and ether-linked phospholipids, are oxidized during ferroptosis and likely contribute to this process in a context-dependent manner [43]. In summary, the membrane phospholipid composition and therefore the endogenous pool of PUFAs dictates ferroptosis sensitivity.

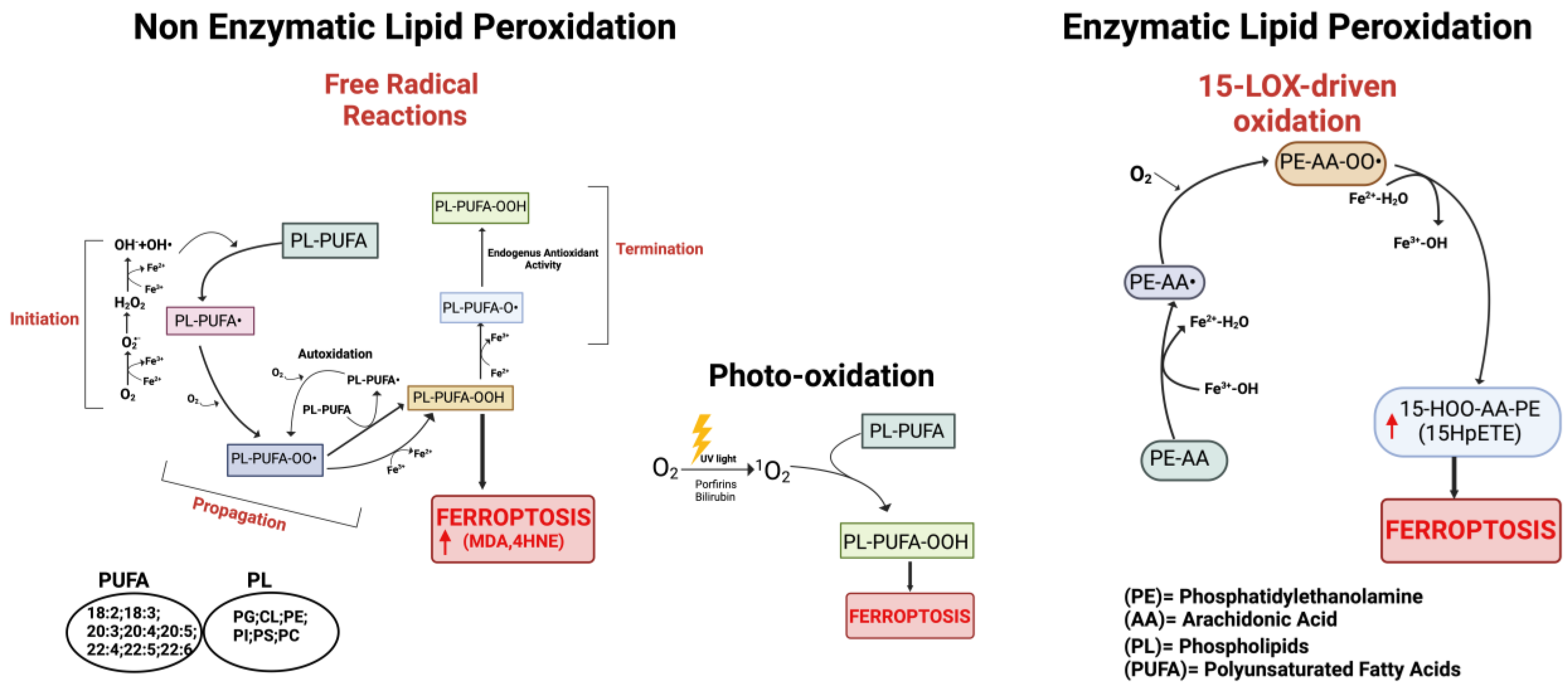

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the three main pathways involved in the process of lipid peroxidation. On the left: non-enzymatic lipid peroxidation producing lipid peroxyl radicals (PL-PUFA-OO•). In the center: lipid peroxidation mediated by non-radical singlet oxygen (1O2). On the right: enzymatic lipid peroxidation cascade; the mechanism of 15-Lipoxygenase is represented. Red arrows indicate increased products. Created with BioRender.com (accessed on 31 January 2024).

In any case, although there is still much debate over whether the lipid peroxidation process is strictly controlled by enzyme activities or if it starts as uncontrollable free radical reactions, the generation of toxic lipid-derived peroxide species involves different forms of catalytically active iron. In order to better comprehend the molecular signature of ferroptosis, it is crucial to critically assess the precise role that iron plays during this process, as well as to promote the development of anti-ferroptotic strategies based on iron chelation [44].

Normally, lipid peroxides are maintained at physiological levels by sophisticated intracellular antioxidant systems (e.g., GPX4/GSH, FSP1/CoQ10, GCH1/BH4), which are generally inhibited or down-regulated during ferroptosis [45].

2.3. Lipid Peroxidation by Non-Enzymatic and Enzymatic Reactions

Ferroptosis is uniquely characterized and driven by overwhelming membrane lipid peroxidation, which leads to altered ion fluxes and ultimately to plasma membrane permeabilization [12]. Overall, the situation is quite flexible: a wide range of lipid substrates and starting sources may be able to support the lipid peroxidation events that ultimately lead to ferroptotic cell death. More specifically, the generation of toxic lipid-derived peroxide species may result from non-enzymatic or enzymatic processes, both involving different forms of catalytically active iron. Evidence for the important role of lipid peroxidation in the execution of ferroptosis also comes from inhibition studies. Many potent and specific inhibitors of ferroptosis terminate the lipid peroxidation process by acting as lipophilic radical-trapping antioxidants, thus bolstering the link between lipid membranes and ferroptosis.

The chemistry of lipid peroxidation is well understood and has been extensively reviewed elsewhere [44]. Here, we will briefly mention non-enzymatic or enzymatic processes contributing to the ferroptotic process (a more detailed discussion is given in Section 3). Different phases of initiation, propagation, and termination are involved in the lipid peroxidation mechanism. Anyway, the generation of toxic lipid-derived peroxides encompasses general reaction schemas that are similar in non-enzymatic and enzymatic processes: the oxidation starts with the abstraction of a bis-allylic hydrogen and consequent formation of lipid radical species, and after the addition of molecular oxygen, they become peroxyl radicals and then hydroperoxides. Numerous types of ROS/RNS (see Section 3.1), particularly in the presence of iron, can initiate lipid peroxidation and push ferroptosis. Mitochondria are also sites of substantial ROS generation that may contribute to the initiation of lipid peroxidation, but their role remains controversial [34,46]. Enzymes that can oxidize lipids include members of the lipoxygenase (LOX) and cyclooxygenase (COX) families and oxidoreductase NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase (POR) isoforms, as well as fatty acyl-CoA reductase1 (FAR1) (as discussed in Section 3.1.3). However, since in ferroptosis, PUFA phospholipids have been found to be peroxidation substrates instead of free PUFA, LOXs appear to be the most likely candidate enzymatic catalysts of ferroptotic peroxidation based on the observation that COXs oxidize free rather than esterified PUFA [20,41]. In addition, it is to be highlighted that enzymatic peroxidation is highly selective for specific substrates and products, in contrast to the random profile observed for free radical peroxidation. Therefore, even though the mechanistic reactive intermediates of these peroxidation reactions may be similar, the fundamental questions of regulation, specificity, and selectivity still need better understanding, since this will have a significant impact on the development of novel pro- and anti-ferroptotic therapeutic approaches [47]. Accordingly, ferroptosis inhibitors such as ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) and liproxstatin-1, as well as endogenous antioxidants like α-tocopherol, GSH, and N-acetylcysteine (NAC), inhibit lipid peroxidation, thus demonstrating that ferroptosis induction requires lipid peroxidation and iron-dependent ROS.

As a kind of PUFA-hydroperoxide-dependent cell death, ferroptosis can be theoretically initiated/carried out in all biological membranes, including mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), peroxisomes, Golgi apparatus, and lysosomes. Previous reports have observed the activation of the ER stress-related unfolded protein response during ferroptosis [48,49]. To identify the membranes of subcellular structures essential for ferroptosis and unveil the possible sequence of peroxidation, A. N. von Krusenstiern et al. performed a deep evaluation of the structure, activity, and distribution of ferroptosis inhibitor/inducers using novel, powerful technologies [43,50]. In that paper, the authors identified ER membranes as the initial and crucial sub-compartment of lipid peroxidation, even if various other subcellular membranes can produce lipid peroxidation. Thus, the authors suggested an ordered progression: initially lipid peroxides accumulate in the ER membrane and later in the plasma membrane; however, it is not clear if the peroxidation can spread to other membranes, or if it occurs independently at different stages and with different rates.

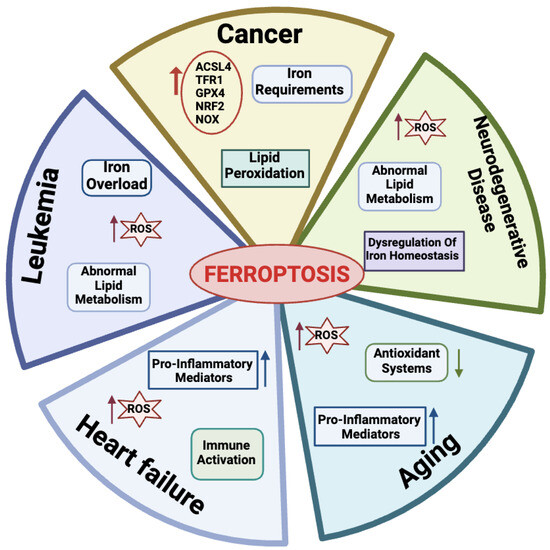

2.4. Ferroptosis and Physio-Pathological Processes

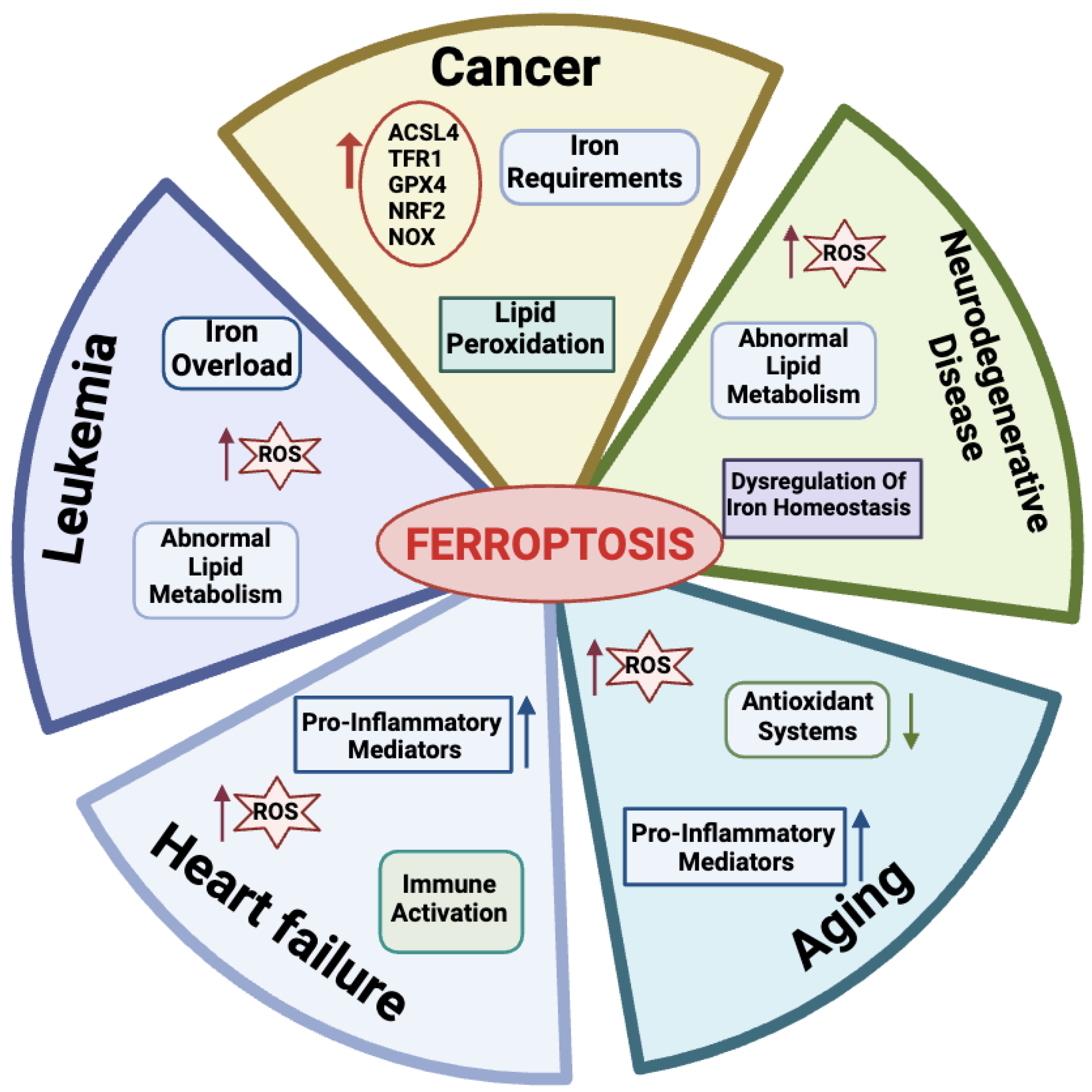

Many physio-pathological processes have been correlated with ferroptosis [2,51], including aging and neurodegeneration, senescence, tumorigenesis, blood diseases, kidney disorders, and ischemia–reperfusion injuries (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Physiological and pathological processes related to ferroptosis. For each disease, the main features are reported. Created with BioRender.com (accessed on 30 January 2024).

2.4.1. Ferroptosis in Aging

Aging is a natural life process characterized by a gradual deterioration of physiological mechanisms, resulting in impaired functions of the organs and increased morbidity and mortality due to a combination of environmental and genetic factors. Hallmarks of aging processes include overproduction of ROS species, exhaustion of antioxidant systems, imbalance in oxidation and antioxidant processes [52], and the up-regulation of oxidative stress-induced pro-inflammatory mediators [53,54]. More recently, aging has also emerged as a process related to dysregulated iron homeostasis with intracellular iron stores accumulating with increasing age [55]. Therefore, since the discovery of the ferroptotic mechanisms, a link between aging and ferroptosis has been postulated in a variety of age-related processes, including cancer, neurodegenerative, and cardiovascular diseases [56]. As an example, in this section, we briefly introduce the impact of ferroptosis on these diseases.

2.4.2. Ferroptosis in Cancer Cells

Many links correlate tumors with ferroptosis. Active metabolism in cancer cells is causative of high ROS production [3]. Hallmarks of cancer metabolism also include elevated iron requirements that under oxidative stress make cancer cells more susceptible to ferroptosis as compared to their normal counterparts. In addition, ferroptosis is regulated by numerous tumor-related genes and signaling pathways [57,58]. Several mechanisms involved in ferroptosis, including system Xc-, GPX4, lipid peroxidation, and GSH metabolism, mediate biological processes such as oxidative stress and iron overload and appear to be dysregulated in many cancer types [59,60,61,62].

However, given the extraordinary complexity and heterogeneity of this group of disorders, sensitivity to ferroptosis may vary greatly among different types of cancer cells. For example, p53, which exerts a critical role in inhibiting tumorigenesis and other cancer processes such as invasion, metastasis, and metabolism, has been reported to control ferroptosis-related genes to prevent tumor growth [63,64]. However, as discussed in detail in Section 4.6 it recently emerged that p53 has opposing effects on ferroptosis regulation in different tumor cells. Thus, ferroptosis susceptibility may be modulated by p53 in a tissue-and cell type-specific manner.

More recently, ferroptosis has been proposed as a strategy to overcome drug resistance in cancer cells, which are often resistant to apoptosis and standard therapies [65,66]. However, cancer cells may employ a variety of genetic or epigenetic strategies to combat these metabolic and oxidative stresses [67]. For example, they may up-regulate the antioxidative transcription factors nuclear factor, erythroid derived 2, and like 2 (NRF2) or increase the expression of solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11), which reduces the cell’s vulnerability to ferroptosis. Therefore, whether a cancer cell is more sensitive or resistant to ferroptosis induction depends on its specific genetic background. Additionally, through adaptive mechanisms, ferroptosis may contribute to immunity against cancer. Therefore, because ferroptosis can be an immunogenic or immunosuppressive type of cell death, its function in cancer is rather controversial and needs further studies [68].

2.4.3. Ferroptosis in Leukemia

Normal hematopoiesis requires iron, the depletion of which impairs the proliferation and differentiation of hematopoietic cells [69]. Leukemic cells have higher iron concentrations and transferrin expression than other cancer cells and this facilitates the accumulation of iron-derived damage, especially to membrane lipids. Accordingly, a large body of work has recently highlighted the role of ferroptosis in acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Metabolic pathways typically altered in AML and related to ROS/RNS production include enzymes like nitric oxide synthase (NOS), CYP, NAD(P)H oxidase (NOX), and COX (reviewed in [70]). The high frequency of ROS/RNS overproduction in leukemia clearly implies that they are related to the etiology of this disease [71]. Oxidative stress plays a dual role in the development of hematologic malignancies [72]. Chemotherapeutic drugs induce apoptosis by producing high levels of ROS, which suppress tumor growth [73]. Low levels of ROS, on the other hand, protect AML cells from apoptosis and increase treatment resistance, cell migration, growth, and proliferation [61,74]. AML cells are particularly sensitive to iron overload, and although there is strong evidence that transferrin is highly expressed in these cells with increased binding activity, the exact effect of transferrin on AML cells is unclear [70]. Therefore, ferroptosis is emerged as a therapeutic target in leukemia. Indeed, as reviewed by Weber et al. [75], there are four main categories under which current methods of treating AML fall: iron chelators, modification of iron metabolism-related proteins, production of ferroptosis, and administration of antileukemic drugs through ferritin [75]. Of note, all of these categories are based on the modulation of iron metabolism.

2.4.4. Ferroptosis in Heart Failure

Heart failure (HF) is a worldwide epidemic condition that is becoming increasingly common and endangers people’s health. Cardiomyocytes play a key role in maintaining the physiology of the heart and the loss of these caused by cardiovascular disease can speed up the development of HF [76]. During HF, there is an increase in LIP production causing a release of free iron in the myocardium that can alter redox balance and promote ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes [77]. Studies have shown that ferroptosis can also cause a systemic inflammatory response that induces hypertrophy and the death of cardiomyocytes and leads to chronic adverse ventricular remodeling [78,79]. Thus, inhibition of ferroptosis can prevent inflammation and consequently, cardiomyocyte death, while preserving normal cardiac function [80]. A recent investigation revealed that in cardiomyocytes (H9c2 cells) treated with isoprenaline or erastin in a rat HF model induced by aortic banding there was an excess of lipid peroxidation, elevated iron content, and decreased cell viability [81,82]. Also, ferritin plays a key role in maintaining iron homeostasis in the heart. In fact, ferritin H-deficient mice showed reduced expression of SLC7A11 in heart cells, while selective overexpression of SLC7A11 increased GSH levels and prevented cardiac ferroptosis [83]. Research has thus uncovered the regulatory mechanisms and function of ferroptosis in cardiac disease, offering novel treatment options and insights. Nevertheless, not enough is known about ferroptosis’s function in this area to create a successful treatment plan.

2.4.5. Ferroptosis in Neurodegenerative Diseases

Among age-related conditions, neurodegenerative diseases are frequent causes of disability and among the most common causes of death worldwide. The abnormal metabolism of lipids, of which the brain is especially rich, leads to ferroptosis, which can greatly contribute to acute damage to the central nervous system. Indeed, dysregulation of iron homeostasis and excessive ROS in the brain are common hallmarks of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) [84]. When neurons die, their iron-containing inclusions are released. This condition generates a vicious circle: in the absence of efficient iron removal systems, iron accumulates in brain areas and promotes the generation of ROS species, causing other neurons to undergo ferroptosis and further reducing the levels of antioxidant defenses [85,86]. Consequently, with iron-dependent oxidative stress serving as a key indicator of cellular ferroptosis, the notion that ferroptosis is inextricably linked to neurodegenerative diseases is receiving growing support. As a consequence, controlling ferroptosis has become a new treatment option for these disorders. In the case of AD, iron chelators delay the disease onset by preventing neuronal death [87,88].

In Parkinson’s disease, the age-related reduced capacity to regulate iron absorption also contributes to iron overload, which is common among older people. Notably, ferroptosis features like iron accumulation, GSH depletion, lipid peroxidation, and an increase in ROS species have been observed in PD. Accordingly, inhibitors of ferroptosis have the potential therapeutic role to protect the nervous system in PD [89,90,91].

3. Redox Homeostasis and Antioxidant Systems: Links to Ferroptosis

Cells undergoing ferroptosis fail to maintain redox homeostasis, skewing toward metabolic pathways that fuel lipid peroxidation. There are three major pathways involved in this type of cell death: those increasing the levels of ROS/RNS and lethal lipid peroxides, those engaging in molecular systems that foster the release/accumulation of redox-active iron, and those inactivating antioxidant defenses and lipid repair, albeit the exact cascade/s, if they exist, have not yet been well defined chronologically [51]. The next sections briefly introduce the concept of redox homeostasis and the link between oxidative stress–ROS/RNS–lipid peroxidation and the ferroptotic process.

3.1. ROS/RNS and Redox Homeostasis in Ferroptosis

Ferroptosis is a ROS/RNS-associated cell death: perturbation of the redox status provoking the accumulation of ROS/RNS, mainly evoked by iron increase and downstream lipid peroxidation, represent indeed the principal hallmarks of ferroptosis [11,92]. Accordingly, ferroptosis can be counteracted by ROS/RNS scavengers, by enhanced antioxidant activities, as well as by specific compounds such as ferrostatin or deferoxamine, able to trap peroxyl radicals or chelate iron, respectively (reviewed in [93]). ROS/RNS are molecules possessing peculiar biochemical features, and under physiological conditions, their levels are finely regulated. Indeed, endogenous ROS/RNS, when produced in a controlled manner, participate in important proliferative cascades, behaving as crucial signaling molecules [94]. This highlights the need for biological systems to have the levels and quality of ROS/RNS under strict control. The term “redox homeostasis” is used to indicate that cells maintain appropriate levels of ROS/RNS for physiological oxidant cues (known as eustress) [95]. However, cells can experience oxidative challenges (termed distress) due to high ROS/RNS levels that can trigger oxidative damage to the biomolecules. As such, it is important for cells to detect oxidants and manage them to control the risk of damage. In agreement with this, redox homeostasis is linked to specific endogenous systems that detect changes in redox status and engage downstream antioxidant pathways to try to restore the redox balance [38].

3.1.1. ROS/RNS Sources in Ferroptosis

The terms ROS and RNS refer to different molecules with variable reactivity including free radicals and non-radical species (reviewed in [18,94,96,97,98]). The generation of ROS occurs during aerobic metabolism by the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC), or from specific enzymatic reactions as well as through the non-enzymatic Fenton reactions that in the presence of free iron or copper directly produce ROS (reviewed in [98,99,100]) (Figure 2). Examples of ROS are the non-radical hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and various oxygen-centered radicals like the superoxide anion (O2•−), the hydroxyl radical (HO•), and the hydroperoxyl radical (H/ROO•).

H2O2 is the most relevant non-radical ROS, and it possesses a relatively low reactivity. At specific concentrations, it is the main component of signaling cascades as reviewed elsewhere [94,101]. The principal targets of H2O2 are the thiol of cysteine residues, thus leading to modifications in protein activities. H2O2 is produced enzymatically by cytochrome P450s (CYPs), cyclooxygenases (COXs), and various oxidases (XOs) to support signaling cascades; H2O2 is also generated transiently by the different superoxide dismutase (SOD1-3) isoforms, located both inside and outside the cells. Of note, a recently identified enzyme producing H2O2 and involved in ferroptosis is the oxidoreductase NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase (POR), which will be discussed later. It is worth mentioning that H2O2 molecules can cross membranes directly or through aquaporin channels, therefore initiating membrane damage. H2O2 participates in lipid peroxidation through reactions that are heavily reliant on the presence of free iron and copper. Specifically, H2O2 in the presence of Fe2+ and Cu2+ is the main source of hydroxyl radicals, like HO•, HOO•, and ROO• (referred to as Fenton reactions), which represent the most reactive ROS species able to trigger non-enzymatic oxidation in a wide range of biological molecules [94,102], including lipids. As herein discussed, the main targets of these types of ROS are PUFAs, especially those present in biological membranes, provoking the generation of phospholipid peroxides (PL-PUFA-OOH), a causal event in ferroptosis.

O2•− can originate accidentally in vivo due to the “leakage” of electrons from the mitochondrial ETC as well as from enzymatic reactions involving dedicated enzymes like various NAD(P)H oxidases (NOXs), xanthine oxidase (XO), and uncoupling nitric oxide synthase (u-eNOS).

NOXs include a family of transmembrane enzymes and constitutively provide localized O2•− radicals. In particular, NOX4 and dual oxidase 1 and 2 (DUOX1/2), by retaining O2•− longer, favor its spontaneous dismutation to H2O2 [103]. Production of ROS by NOX1-4 has been implicated in the ferroptosis of cancer cells, provoking lipid peroxidation [104,105,106,107]. Dixon et al. demonstrated that selective inhibition of NOX1-4 activity suppressed ferroptosis induced by erastin in Ras-mutated cancer cells [11]. NOXs use NADPH as a reducing cofactor and since NADPH also serves to recycle oxidized glutathione (GSSG) by the glutathione reductase (GR), NOX overexpression can consequently impoverish cells of GSH, thus exacerbating pro-oxidant conditions [108]. In addition, the activity of NOXs in the process of ferroptosis is increased by the dipeptidyl-peptidase-4 (DPP4) protease, which is a p53-regulated protein [104,105]. NOXs also constitute an important downstream source of H2O2 because of reactions involving SOD enzymes and/or xanthine oxidase, amino acid oxidase, glucose oxidase, and urate oxidase enzymes that directly produce peroxides from a 2-electron reduction of oxygen. However, O2•− and H2O2 are molecules with limited chemical reactivity because, as reported before, they can be enzymatically inactivated by SOD isoenzymes and by catalase, respectively.

ROS produced by mitochondria also seem to play an important role in the ferroptosis cascade (reviewed in [45,46]), albeit this is considerably debated, firstly because mitochondrial ROS mainly trigger apoptosis and other types of cell death. Mitochondrial ROS originate not only from partial reduction of molecular oxygen by ETC but also from the tricarboxylic (TCA) cycle, as well as from iron overload reactions, thus revealing even more diverse sources of mitochondrial ROS. In a pioneering study, Gao et al. demonstrated that mitochondria-depleted cells (through Parkin-mediated mitophagy) were less sensitive to ferroptosis induced by cysteine starvation or by erastin (that inactivates cystine import, as discussed below), and that the pharmacological inhibition of ETC prevented the accumulation of lipid peroxides, regardless of inducers [109]. Of note, these effects cannot be reproduced in ferroptosis induced by RSL3, a direct GPX4 inhibitor, indicating that independently of mitochondria, this enzyme plays a key role in ferroptosis protection [109]. Other sources of mitochondrial ROS in ferroptosis are represented by two interrelated metabolic pathways: glutaminolysis and tricarboxylic cycle (TCA). The enzyme glutaminase 2 (GLS2), a gene target of p53, converts glutamine to glutamate, which is then deaminated by glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) to α-keto-glutarate (αKG), an intermediate metabolite of the TCA cycle. The increase in αKG can activate TCA as well as fatty acid synthesis, consequently boosting both ROS production and lipid peroxidation [109,110]. In line with this, Suzuki and colleagues recently demonstrated that Gls2-deficient mice or GLS2-depleted human cancer cells are significantly resistant to ferroptosis and this can contribute to the onset of liver cancer. The authors also proved that GLS2 ablation in hepatic cells causes a decrease in lipid peroxides upon treatment with ferroptosis inducers (erastin and RSL3), with a modest effect on GSH content, implying that GLS2 works through αKG-dependent activation of the TCA cycle and consequently ETC increases (the glutaminolysis–TCA–ETC axis) [111].

Also related to mitochondrial ROS–ferroptosis, Shin et al. demonstrated that the dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (DLD), a subunit of the TCA α-keto-acid dehydrogenase (KGDH) complex, can push ferroptosis induced by cystine deprivation or erastin [112]. DLD was previously reported to be a source of mitochondrial ROS [113]. Indeed, DLD gene silencing lowers ROS as well as lipid peroxides generated under cystine depletion [112].

In addition to glutaminolysis, decarboxylation of glucose-derived pyruvate can fuel TCA cycle and ETC activity as well as lipid biosynthesis, thereby facilitating ROS generation and lipid peroxidation; a recent work indeed reported that the enzyme pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (PDK4) confers resistance to ferroptosis by suppressing pyruvate decarboxylation/fatty acids synthesis [114]. ROS production can also result from an increase in mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), an event that unleashes ferroptosis upon erastin treatment or cystine starvation [45]. Of note, membrane hyperpolarization represents another difference between ferroptosis and apoptosis: indeed, apoptosis is mostly associated with a ΔΨm decrease [115].

Iron being the metal present in a greater quantity in mitochondria [116], it is the main protagonist of ROS/lipid peroxide formation through Fenton reactions. In addition, iron and its derivate molecules, such as heme or iron–sulfur [Fe-S] clusters, are necessary for the activities of ETC complexes. Iron import may be mediated by voltage-dependent anion channels (VDACs), which favor the entry of most metabolites into mitochondria [117]. For example, iron accumulates in mitochondria after erastin treatment, probably because of VDAC 2/3 channel opening [118], therefore leading to iron-dependent ferroptosis. Of note, the discovery of mitochondria-specific defenses against ferroptosis [119,120] suggests that albeit mitochondria metabolic activities can facilitate ferroptosis, these organelles are equipped with efficient anti-ferroptosis systems. For example, an increase of the iron–sulfur protein (2Fe-2S) mitoNEET (also termed CISD1, CDGSH iron sulfur domain 1), can prevent iron and ROS accumulation by mediating the export of iron and sulfur ions from mitochondria, thereby protecting them from ferroptosis [121,122]. Since mitochondria are a site of specific ROS-producing processes, their involvement in ferroptosis is almost obvious, however, when mitochondrial physiological functions are intact, cells are resistant to ferroptosis: indeed, β-oxidation and the formation of Fe/S clusters boost resistance to ferroptosis.

HO• is one of the most reactive ROS. Because of its poor selectivity, it can attack all biomolecules at or near diffusion-mediated rates. This radical can be produced through non-enzymatic reactions between H2O2 and free iron/copper involving the complex Fenton chemistry. In addition, among the ROS species, HO• might also be produced by the decomposition of peroxynitrite anion (ONOO−). Importantly, the hydroxyl radical cannot be eliminated by enzymatic reaction/s, hence it can produce deleterious effects on different cell structures, either directly or indirectly, especially when produced in proximity to membrane lipids [20].

The most relevant RNS comprise the intercellular messenger nitric oxide (NO•) generated by different NOS enzymes from the oxidation of L-arginine (the amino acid), the nitrogen dioxide (NO2•) radical and the peroxynitrite anion, a powerful oxidant [18,98,99,102,123,124] (Figure 2). The NO• molecule rapidly reacts with superoxide anion generating ONOO−; therefore, NO• is often considered to be a toxic species, albeit it is also able to terminate lipid peroxidation propagation reactions (as discussed below) [125]. Peroxynitrite can interact irreversibly with different biomolecules (thiols, iron/sulfur centers, zinc fingers, and metalloproteins), finally leading to cytotoxic events that may evoke apoptotic or necrotic cell death [126]. The involvement of ONOO− in lipid peroxidation was first suggested in the atherosclerosis process [127,128] and then reported in other experimental models as well as in a variety of diseases like cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases (reviewed in [129]).

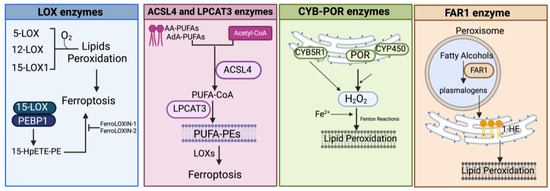

3.1.2. Process of Lipid Peroxidation

It is now widely accepted that peroxidation of PUFAs located in membrane phospholipids (PL-PUFAs) represents a crucial driver of ferroptosis, albeit an open question is how PL peroxidation/damage initiates the molecular cascades that evoke cell death signals [51]. Indeed, free fatty acids do not drive this type of cell death; on the contrary, specific PL-PUFA, essential components of all cell membranes, are particularly susceptible to peroxidation [43]. As shown in Figure 2 and Figure 4, there are three different ways by which peroxidation (dioxygenation) of PUFAs can be executed: (1) free radical reactions (a non-enzymatic radical-chain process); (2) photo-oxidation involving singlet oxygen; and (3) enzyme-mediated peroxidation reactions (this route will be discussed in more detail).

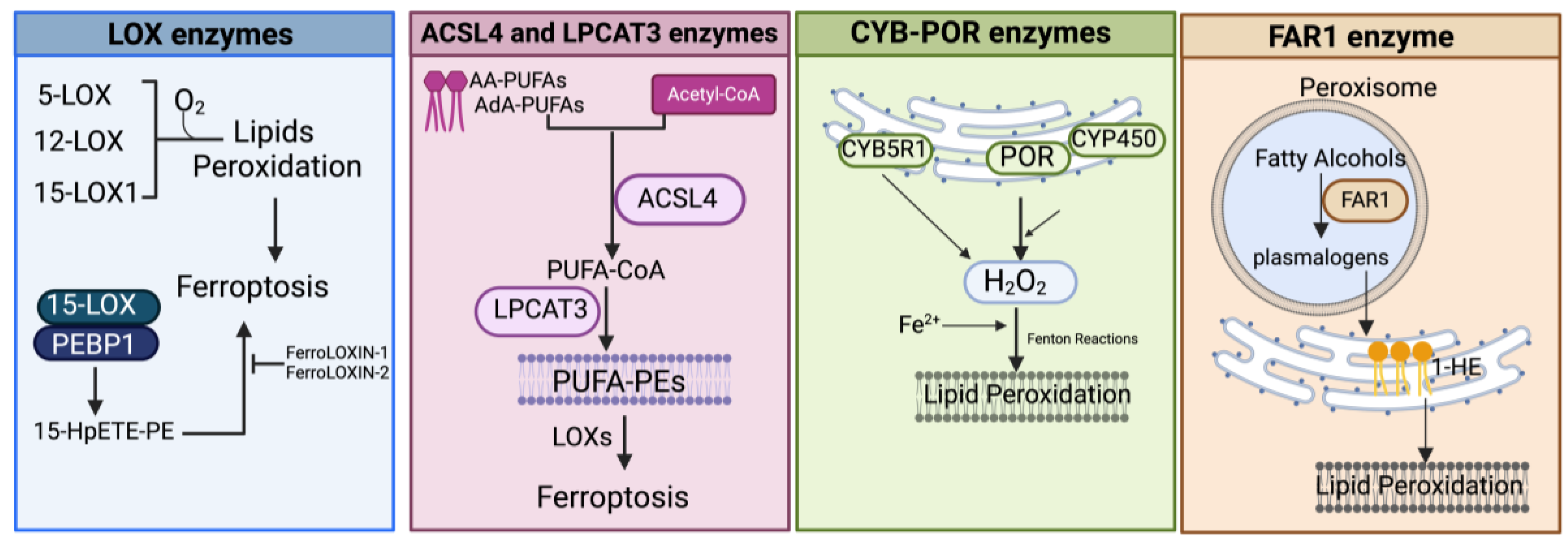

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the main enzymatic pathways mediating the process of lipid peroxidation in ferroptosis. LOX, lipoxygenase; PEBP1, phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein; 15-HpETE-PE, 15-hydroperoxyphosphatidylethanolamines; AA-PUFAs, PUFA arachidonic acid; AdA-PUFAs, adrenic acid; PUFA-PEs, PUFA-phosphatidylethanolamines; CYB5R1, NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase 1; POR, NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase; CYP, cytochrome P450s; FAR1, fatty acyl-CoA reductase1; 1-HE, 1-hexadecanol. Created with BioRender.com (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- (1)

- The radical-chain process (or radical chain reaction) consists of three sequential non-enzymatic events: initiation, propagation, and termination (Figure 2). Free reactive oxygen-centered radicals, in particular HO• and HOO•, mainly originate from Fenton reactions and can initiate the lipid peroxidation process of different types of PL-PUFAs, frequently those present in biological membranes. In fact, by abstracting a hydrogen atom from a methylene carbon inside the acyl chain double bounds, HO• and HOO• leave an unpaired electron on the carbon, generating a reactive carbon-centered lipid radical (PL-PUFA•); this last can also originate in a spontaneous manner inside the acyl chain harboring the “C=C” double bond (autooxidation/autocatalytic) [130]. Usually, this lipid radical undergoes molecular rearrangement to form an internal conjugated diene, which by reacting with O2 rapidly produces a lipid peroxyl radical (PL-PUFA-OO•). These molecules can subsequently remove hydrogen atoms from adjacent PL-PUFA chains or can combine with each other in several ways (propagation event), producing lipid hydroperoxides (PL-PUFA-OOH), especially if they encounter metals like iron or copper, that by Fenton reactions can also push lipid autoxidation [131]. Thus, if not interrupted by chain-breaking antioxidants (a termination step), an internal radical propagation and peroxidation of lipid radical species can result in a large amount of lipid peroxides [132,133]. The comparatively low dissociation energy of O-O bonds causes PL-PUFA-OOH cleavage, which produces a variety of secondary oxidation products, many of which have an oxygen-containing functionality and a shortened carbon chain with strong electrophilic tendencies. The most common electrophiles are aldehydic, oxo-, and epoxy groups, which can be found at various points along the hydrocarbon chain. Either the truncated phospholipid or the remaining shorter PUFA fragment can form an electrophilic group. Furthermore, persistent exposure to iron and/or copper leads to the decomposition of lipid hydroperoxides with the production of harmful carbonyl compounds like unsaturated 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), malondialdehyde (MDA), and acrolein or end products [134] that can further foster destabilization of cell membranes, finally evoking the breakdown of membrane integrity and consequently ferroptosis [135,136].

- (2)

- The second mechanism involves the non-radical singlet oxygen (1O2), originating from O2 by light energy transfer and/or from endogenous enzymatic reactions involving COX, LOX, and myeloperoxidase enzymes, or from photosensitizer endogenous agents like bilirubin, porphyrins, flavins, pterins, melanin/melanin precursors, vitamin K, and B6 vitamers that could absorb light and transmit energy to O2 producing 1O2 (Figure 2) [137,138,139,140]. By representing an excited state of molecular oxygen, singlet oxygen is highly electrophilic and can rapidly react with various molecules, including unsaturated lipids, especially those present in cell membranes. The mechanism differs from lipid free radical autoxidation in that the singlet oxygen directly reacts with the double bond producing lipid peroxyl radicals, more similar to the reaction performed by the HOO• radical.

- (3)

- Lipid peroxidation by direct enzymatic mechanisms principally involves members of the lipoxygenase (LOX) family coupled to ACSL4/LPCAT3 activity and the oxidoreductase NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase (POR) isoforms as well as fatty acyl-CoA reductase1 (FAR1), as discussed in the next section.

3.1.3. Enzyme-Mediated Lipid Peroxidation (Figure 2 and Figure 4)

LOX Enzymes

In mammals, the oxidoreductase lipoxygenases with dioxygenation activity are mainly implicated in a metabolic cascade termed the “LOX pathway” producing leukotrienes, one of the classes of bioactive lipids known as eicosanoids [141]. The eicosanoid family also includes prostaglandin, thromboxane, and lipoxin mediators, and the term “eicosanoids” identifies molecules originating from 20-carbon PUFAs (“eicosa” meaning 20 in Greek). Specifically, the LOX pathway converts PUFAs, especially arachidonic acid (C20:4, n-6) and linoleic acid (C18:2, n-6), into their corresponding hydroperoxyl derivatives by introducing molecular oxygen at stereospecific positions of the acyl chain. Mechanistically, LOXs, which are non-heme iron-containing enzymes, produce metabolites in a multistep reaction: in the case of arachidonic acid (AA) as a substrate (as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 4), in the first step, AA undergoes a hydrogen abstraction with electron rearrangement, generating Fe2+ from Fe3+, which is necessary to produce the free radical PE-AA• that can further incorporate the oxygen molecule producing the peroxyl radical (PE-AA-OO•). This molecule is reduced to an anion and then protonated to PUFA-hydroperoxyl molecules (PE-AA-OOH/HpETE) in a step coupled to the regeneration of Fe3+. Non-heme iron is essential for the catalytic steps and redox cycling of LOX enzymes. These primary HpETE molecules can rapidly be converted by LOXs or other enzymes like GSH peroxidases or cyclooxygenases (COX1 and COX2) and cytochrome P450 (CYP450) family members, acting in series with LOXs [142], into end-products comprising (i) metabolites of arachidonic acid [12- or 15-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (12-, 15-HETE)]; (ii) metabolites of linoleic acid [13- or 9-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid (13-, 9-HODE)] and products derived from docosahexaenoic acid (C22:6, n-3), as well as (iii) the mentioned leukotrienes [141]. By producing PUFA-hydroperoxides in phosphatidylethanolamines, LOXs are considered pro-oxidative enzymes, and among the six functional isoforms existing in humans, 15-LOX1 and 15-LOX2 seem specifically involved in drug-induced ferroptosis [143]. The principal pro-ferroptotic molecules derived from arachidonic acid are represented by the downstream metabolites 15-hydroperoxyphosphatidylethanolamines (15-HpETE-PEs), considered also predictive biomarkers of ferroptosis [144,145] (Figure 2 and Figure 4).

The first implication of lipoxygenases in ferroptosis came from the group of Brent R. Stockwell [146]. Using a pool of siRNAs targeting all arachidonate lipoxygenases (A)LOX isoforms, the authors demonstrated that (A)LOXs are causally involved in the production of lethal lipid peroxides during ferroptosis triggered by erastin, a Xc- inhibitor, (but not by GPX4 inhibitors), albeit the specific isoforms can work in a context-dependent manner [146]. Furthermore, lipidomic analysis in ferroptosis-sensitive HT-1080 fibrosarcoma cells, under the same erastin conditions, indicated that loss of the polyunsaturated fatty acids was the most prominent change, accompanied by increased levels of ceramides and lysophosphatidylcholine (lyso-PC). Screening with representative PUFAs and MUFAs, cholesterol and cardiolipin, identified PUFAs as targets of lipid peroxidation [146]. Then, by screening phospholipids and their oxidation products, they found that double- and triple-oxygenated arachidonic acid and adrenic acid (AdA, C22:4, n-6), specifically incorporated into phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), can behave as signals for ferroptotic death [146]. Another study by Kagan et al. also showed that under RSL3-mediated GPX4 inhibition, AA and AdA are oxygenated mostly when incorporated into PE but not if present as free PUFAs [144]. Accordingly, Shah et al. demonstrated that supplementation with non-oxidizable fatty acids such as MUFAs or D-PUFAs (PUFAs containing deuterium atoms at the reactive bis-allylic sites) lowered ferroptosis [35,147]. As demonstrated by Shah et al., LOXs, albeit not indispensable during ferroptosis execution, are causal factors in the initiation of this process by contributing to the generation of a lipid hydroperoxide pool [35]. In that study indeed, overexpression of 5-LOX or 12-LOX, or 15-LOX1 isoforms was found to sensitize HEK293 cells to ferroptosis, and that only radical-trapping antioxidant compounds, like ferrostatin or liproxstatin-1, which protect membrane lipids from autoxidation, can prevent this type of cell death. Accordingly, it has been found that inhibition of several LOX isoforms either genetically or pharmacologically could prevent ferroptosis, at least to some extent [148].

As reported before, the incorporation of PUFAs into phospholipids, the principal substrates for LOX-mediated oxidation, is performed by two metabolic enzymes, ACSL4 and LPCAT3 (as discussed later in detail), and the ACSL3/LPCAT3/LOX constitute an important pro-ferroptotic cascade. The substrate competence of LOXs can be changed by their interaction with the tumor suppressor PEBP1 (phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein, also called RKIP1), a scaffold protein inhibitor of protein kinase signaling, that consequently modulates the specificity of their products [149]. Wenzel et al. in their recent research further explored the role of this interaction in a ferroptosis context. By using Far Western blotting, cross-linking, and computational modeling, they demonstrated that PEBP1 specifically interacts/co-localizes with both 15-LOX isoforms and that the 15-LOX/PEBP1 complexes selectively generate the pro-ferroptosis molecule 15-HpETE-PE [150]. In search of selective inhibitors of the complex 15-LOX/PEBP1, it was very recently demonstrated that FerroLOXIN-1 and 2, screened from a customized library of 26 compounds, in vivo and in vitro could prevent ferroptosis provoked by RSL3 [151]. Of note, it has been reported that the 12-LOX enzyme is required for p53-mediated ferroptosis upon ROS stress [149]. However, lipid peroxidation by lipoxygenases is a controversial issue. Firstly, because the (A)LOX inhibitors used to confirm the (A)LOX role in ferroptosis are compounds with radical-trapping antioxidant activity [35], it remains unclear whether they prevent ferroptosis by inhibiting (A)LOXs or by trapping lipid peroxyl radicals. Secondly, data from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia RNA-Seq indicate that (A)LOX mRNAs are present at very low levels and that (A)LOXs depletion in some cancer cells did not provide protection against ferroptosis [36] (Figure 4).

ACSL4 and LPCAT3 Enzymes

As mentioned before, membrane phospholipids, particularly phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) containing PUFAs, are critical determinants in ferroptosis sensitivity [144]. ACSL4- and LPCAT3-mediated reactions are jointly required for the initiation of ferroptosis by controlling the availability of PUFA substrates for phospholipid synthesis (Figure 4). Specifically, ACSL4 catalyzes the addition of CoA to long-chain polyunsaturated-CoAs (PUFA-CoAs), preferentially of AA and AdA, therefore activating the biosynthesis of AA- or AdA-containing phospholipids (reviewed in [152]). PUFA-CoAs then become substrates of the lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase (LPCAT) enzymes, particularly LPCAT3, which esterifies the PUFA-CoAs into PUFA-phospholipid (reviewed in [153]). Pioneering studies demonstrated that ACSL4 is directly implicated in ferroptotic responses triggered by GPX4 inhibitors or by erastin [144,154,155]. In line with these results, it was reported that ACSL4 inactivation could block ferroptosis induced by FINs [36,156]. Doll et al. demonstrated that in ACSL4-knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts, the amount of PUFA-phosphatidylethanolamines (PUFA-PEs) was reduced, and this protects cells against ferroptosis, whereas loss of other ACSL members failed in prevention [154]. This prompted the authors to further examine a panel of fatty acids to uncover specific substrates of ACSL4 and they found that AA- and AdA-containing PEs were selectively lowered in ACSL4-deleted cells, with unchanged levels of phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylserine species [154]. Therefore, in the condition of GPX4 absence/inactivation, ACSL4 but no other ACSL family members could initiate the ferroptotic cascade by specifically activating AA- and AdA-PUFAs that, in turn, can become substrates for peroxidation mediated by LOX enzymes [144]. Indeed, ACSL4 is often used as a biomarker for ferroptosis induction. Since the main LPCAT3 substrates are PUFA-CoAs, the ACSL4/LPCAT3 axis increases the raw material for peroxidation reactions. Accordingly, inhibition of LPCAT3 can protect cells from ferroptosis by remodeling the PUFA content in PEs [157]. In agreement with this, Cui et al. recently reported that LPCAT3 and ACSL4 knockout can protect lung adenocarcinoma cells from ferroptosis, while ectopic expression displayed the opposite effect. In the same paper, it was demonstrated that LPCAT3 is transcriptionally regulated by the YAP/ZEB/EP300 pathway and that ACSL4 and YAP cooperate with LPCAT3 to establish ferroptosis sensitivity [158].

Hence, during ferroptosis, the activation of the ACSL4-LPCAT3-(A)LOX axis can mediate the production of lethal phospholipid hydroperoxides (15-HpETE-PEs) by reprogramming the PE profile. On the contrary, the ACSL3 isoenzyme that mostly produces MUFA-CoAs [159] and two ER membrane-bound acyltransferase isoenzymes, named MBOAT1/2 (membrane bound O-acyltransferase domain containing 1/2) [160] protect cells from ferroptosis by activating and producing MUFA-phospholipids, which are less oxidable substrates.

POR and CYB5R1 Enzymes

Searching for additional enzymes driving lipid peroxidation, two independent studies discovered that the oxidoreductase NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase (POR) can trigger ferroptosis in most cancer cells [36,156]. This enzyme resides in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) compartments and donates electrons (from NADPH) to the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system or to other heme-proteins like heme oxygenase, cytochrome b5, and squalene monooxygenase using FAD/FMN as a cofactor [161] (Figure 4). Both studies used CRISPR screening to identify genes whose inactivation suppressed FIN-triggered ferroptosis, highlighting as top suppressor hits the cytochrome P450 reductase and the pro-ferroptotic ACSL4 (already identified in other studies). Accordingly, a deficiency of POR promoted resistance to ferroptosis triggered by different ferroptosis-inducing agents, named FINs, in a wide range of cancer cells and lowered lipid peroxide levels without affecting the amounts of GPX4 or glutathione and cell phospholipid profiles [36,156]. Yan et al. demonstrated that the electron transfer activity of POR is essential for ferroptosis albeit lipid peroxidation occurs independently of CYPs, and Zou et al. suggested that POR can push Fenton reactions during electron transfer to CYPs with consequent lipid peroxidation [36,156]. Furthermore, Yan et al. identified another oxidoreductase, namely the NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase 1 (CYB5R1), whose deficiency inhibited lipid peroxidation/ferroptosis. CYB5R1 deletion showed modest effects compared to POR inactivation, but the combination of both POR and CYB5R1 deficiency provoked ferroptosis resistance [156]. Since POR and CYB5R1 are involved in redox metabolism, Yan et al. supposed that these enzymes could generate ROS, likely during electron transfer reactions. In fact, the authors proved that purified enzymes, especially POR, produce H2O2 in an NADPH- and oxygen-dependent manner and that POR-deleted cells have reduced levels of H2O2 [156]. These experiments demonstrate that POR and CYB5R1 (albeit more moderately) can promote lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis through the production of H2O2.

FAR1 Enzymes

Fatty acyl-CoA reductase 1 (FAR1) is a peroxisomal enzyme essential for supplying fatty alcohols during the biosynthesis of ether phospholipids (ePLs) (Figure 4). There are two classes of ether PLs: alkyl-ether PLs and vinyl-ether PLs (also known as plasmalogens) with important cellular roles, including antioxidant defenses, signaling, and structural functions [162]. Ether PL synthesis initiates in peroxisomes, terminates in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and requires fatty alcohols provided by the FAR enzymes. Peroxisomes, now considered crucial contributors to ferroptosis [163], are membrane-bound organelles with multiple functions, including H2O2 production and elimination, synthesis of certain lipids, and degradation of long- and branched-chain fatty acids. Recent evidence showed that the plasmalogen subclass of ether-linked phospholipids could be involved in ferroptosis (FAR1-alkyl-ether lipids axis), thus providing an additional source of PUFA-containing phospholipids, independently of those involved in the ACSL4/LPCAT3 axis (reviewed in [163,164]). In a first work, using a CRISPR-Cas9 suppressor screen, Zou et al. uncovered novel genes comprising alkylglycerone phosphate synthase (AGPS), fatty acyl-CoA reductase 1 (FAR1), glyceronephosphate O-acyltransferase (GNPAT), and 1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate O-acyltransferase 3 (AGPAT3) involved in the synthesis of plasmalogens, as top pro-ferroptosis genes [165]. By lipidomic profiling, the authors demonstrated that the synthesis of polyunsaturated ether PLs can ultimately lead to lipid peroxidation during the pro-ferroptotic cascade [165]. Next, by metabolite screening, Cui et al. identified 1-hexadecanol (1-HE) as a molecule able to trigger ferroptosis under GPX4 inhibitor treatments [166]. 1-HE originates from the reduction of palmitic acid (C16:0) to fatty alcohol (the rate-limiting process in plasmalogen synthesis) through the peroxisome-localized enzyme called FAR1. Cells treated with 1-HE exhibited a high level of lipid peroxidation and FAR1 deletion increased resistance to erastin and RSL3-induced ferroptosis of HT1080 cells [166]. Of note, FAR1 gene transcription is induced upon ER stress [167] through ATF6, a sensor/effector of the unfolded protein response (UPR) that can also upregulate the peroxisomal antioxidant enzyme catalase.

3.2. Antioxidant Defenses and Lipid Peroxidation

The preceding part highlights the critical role of lipid peroxidation (either induced by ROS/RNS or by enzymatic activities) in the ferroptosis process. However, sophisticated endogenous antioxidant systems in living cells can counteract the formation of ROS/RNS and/or lipid hydroperoxides. Antioxidant defenses preserving redox homeostasis may be grouped into different categories able to: (i) prevent the formation of active oxidant molecules by scavenging or quenching ROS/RNS producing reactions; (ii) remove the active (lipo)oxidant products and repair (lipo) damages; and (iii) induce adaptive responses through activation or inhibition of specific enzymes/pathways [94,168]. Dysfunctions of the antioxidant systems are linked to ferroptosis. As noted above, along with iron accumulation and/or metabolic perturbations, excessive RNS/ROS production due to the failure of redox homeostasis can foster biochemical pathways leading to the unrestrained generation of lipid radical species. By selectively reducing hydroperoxy-PEs, the selenoperoxidase GPX4 represents a crucial enzymatic system to prevent lethal lipid hydroperoxides; however, other novel antioxidant systems that operate in different compartments have been unveiled. In the next sections we will focus on those systems implicated in defenses against ferroptosis.

3.2.1. Mechanisms That Prevent or Intercept ROS/RNS and Lipid Peroxides

Considering general defenses against ROS/RNS increases, the isoenzymes SOD1-3 are directly implicated in the dismutation of O2•− into H2O2, hence limiting potential damages in different cell compartments, including membranes [169]. However, the role of these enzymes has been under-investigated in ferroptosis. Mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD2) and manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) work in the mitochondrial matrix and a recent paper demonstrated that SOD2 can protect mitochondrial membrane lipids from ROS-mediated oxidation in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells [170]. SOD2 knocked-down cells exhibited higher concentrations of O2•− that consequently push membrane lipid peroxidation/ferroptosis and increased their radiosensitivity. Because the main effects of SOD2 deficiency are on the ETC complexes I and II while the enzyme dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) contributes to complex III activity [171,172,173], the absence of both SOD2 and DHODH can reduce ferroptosis and radiotoxicity, possibly due to a deficiency of O2•− production.

Albeit both O2•− and H2O2 possess a relatively low reactivity, H2O2 represents a recognized source of HO• and HOO• that can initiate lipid peroxidation events. H2O2 can be decomposed by the peroxisomal enzyme catalase (the most used) and glutathione peroxidases (GPXs), as well as by peroxiredoxins (PRXs) (reviewed in [174]). Catalase can have a protective function against ferroptosis; indeed, its deficiency has already been linked to many oxidative stress-driven diseases (reviewed in [175]). Regarding ferroptosis, it has been demonstrated by Hwang et al. that up-regulation of catalase mediated by PPARδ, a transcription factor implicated in lipid metabolism and energy homeostasis, is responsible for ferroptosis resistance in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) derived from cysteine/glutamate transporter (xCT)-knockout mice [176].

NO• is reported to be an important antioxidant defense, albeit frequently considered a pro-oxidant molecule. Being present not only in low-density lipoproteins (LDLs) in vascular walls but also in cell membranes, it can directly react with lipid-derived peroxyradicals (LOO·) and therefore terminate radical chain propagation reactions [177]. The anti-ferroptosis properties of NO• have been recently reported by Kapralov et al. [178]. They demonstrated that RSL3-induced ferroptosis in RAW 264.7 (bone marrow-derived macrophages) and microglial cells can be inhibited by elevated levels of inducible NO synthase (iNOS/NOS2) that consequently boosts NO• production. Furthermore, manipulation of iNOS levels or iNOS pharmacological inhibition, as well as treatments with NO• donors, supported the protective role of NO•, which counteracted ferroptosis by nitroxygenation of intermediates of the ACSL4-LPCAT3-LOX15 axis, and this effect was specifically dependent on the complex LOX15/PEBP1 (yielding the lethal 15-HpETE-PEs) [145]. Another paper by Homma et al. reported that under ferroptotic conditions triggered by cysteine depletion, GPX4 inhibition, or oxidative treatments in mouse hepatoma Hepa 1–6 cells, the NO• donor NOC18 suppressed ferroptosis, which is probably mediated by inhibition of ROS production and termination of the lipid peroxidation cascade [179].

Removal of membrane-embedded oxidized lipid species, the essence of ferroptosis, is principally mediated by the Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2β (iPLA2β) belonging to the PLA2 family (reviewed in [180]). This enzyme has been implicated in protective processes because of its catalytic activity toward 15-HpETE-PEs: indeed, naturally occurring mutations in its gene (PNPLA9) are associated with neurodegenerative diseases like neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA) class [181] and Parkinson disease 14, autosomal recessive (PARK14) [182]. Previous studies supported the role of this enzyme in the hydrolysis of peroxidized phospholipids (reviewed in [183]), which consequently can counteract ferroptosis cell death, independently of GPX4, as proved in more recent studies [184,185]. Interestingly, Sun et a. found that fibroblasts derived from a patient with a mutation in the PNPLA9 gene and iPLA2β-deficient cells exhibited higher levels of toxic 15-HpETE-PE compared to wild-type cells upon RSL3 treatment [186]. In that study the authors demonstrated that the activity of iPLA2β enzyme is linked to LPCAT3-mediated remodeling of membrane PLs, producing AA-PE required for pro-ferroptotic molecule generation. In addition, a parkinsonian phenotype was documented in CRISPR-Cas9-engineered mice carrying a mutant PNPLA9 gene that displayed a 15-HpETE-PE increase, which also predominated in the midbrains of rotenone-infused parkinsonian rats [186]. Another study identified iPLA2β as an antagonist of the p53-driven ferroptosis cascade upon exposure to tert-butyl hydroperoxide (TBH), a ROS generator [184]. It was demonstrated that ferroptosis triggered by p53 was independent of the GPX4–ACSL4 axis and that iPLA2β was indeed a p53-dependent gene. Depletion of endogenous iPLA2β increased ROS-mediated ferroptosis in wild-type p53 cells, but not in p53 mutated cells. In vivo experiments in human melanoma A375 xenograft tumors further supported that loss of iPLA2β can push p53-mediated ferroptosis. Molecular analyses showed that iPLA2β downregulates ALOX12-generated peroxidized membrane lipids [184].

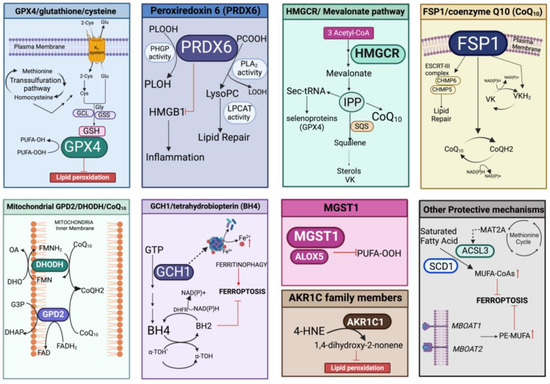

3.2.2. Enzymatic Mechanisms That Protect against Lipid Peroxidation

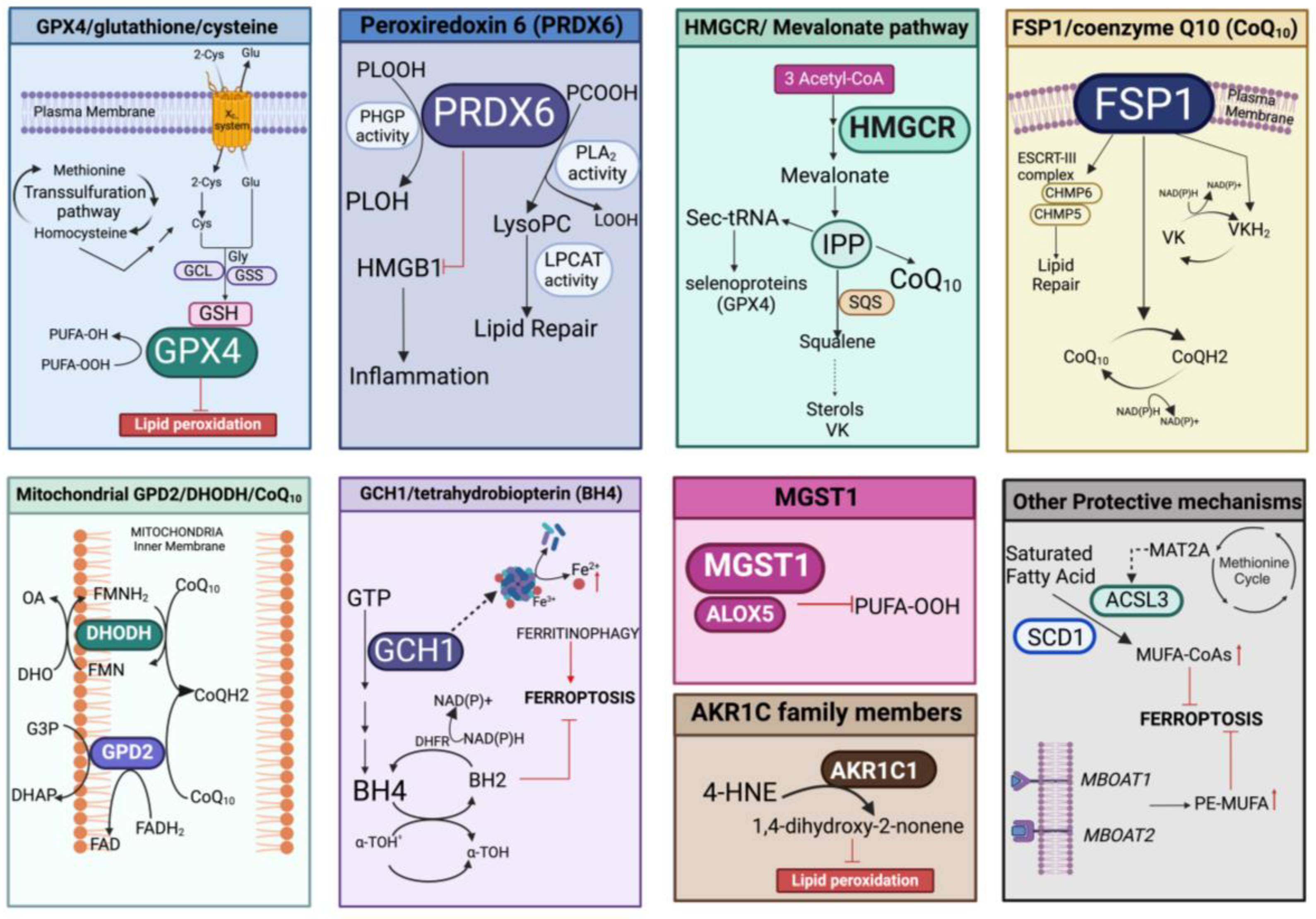

Protection against lipid peroxidation is mainly represented by the redox-related enzymatic system, which could be implicated in the repair of damaged lipids and/or in the elimination of (lipo)oxidation products. This involves the antioxidant pathways of GPX4/glutathione/cysteine, peroxiredoxin 6 (PRDX6), the mevalonate pathway, FSP1/coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10), microsomal glutathione transferase 1 (MGST1), mitochondrial GPD2/DHODH/CoQ10, and the GCH1/tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) system that can also act in concert with other defenses able to fine-tune the lipid composition (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Overview of the different enzymatic pathways involved in prevention/protection against lipid peroxidation. In each panel, the specific enzymatic cascade and cofactors evoking inhibition of ferroptosis are represented. PLOOH, peroxidized phospholipids; PLOH, lipid alcohol; GCL, glutamate cysteine ligase; GSS, glutathione synthase; PCOOH, phosphatidylcholine peroxide; LOOH, hydroperoxyl lipid; lysoPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; LPCAT, lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3; IPP, isopentenyl pyrophosphate; SQS, squalene synthase; Sec-tRNA, selenocysteine (Sec) tRNA; ESCRT-III, endosomal sorting complexes required for transport III; CHMP5/6, charged multivesicular body protein 5/6; VK, vitamin K; VKH2, vitamin K hydroquinone; GPD2, the glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 2; DHODH, the dihydroorotate dehydrogenase; G3P, glycerol-3-phosphate; DHO, dihydroorotic acid; OA, orotic acid; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; FAD, flavin dinucleotide; FADH2 reduced flavin dinucleotide; FMN, flavin mononucleotide; FMNH2, reduced flavin mononucleotide; GCH1, GTP cyclohydrolase 1; BH4, tetrahydrobiopterin; BH2, dihydrobiopterin; α-TOH• α-tocopheroxyl radical; a-TOH, α-tocopheroxyl; DHFR, dihydrofolate reductase; MGST1, microsomal glutathione transferase 1; ALOX5, arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase; AKR1C1, aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C14-HNE, 4-hydroxynonenal; MAT2A, methionine adenosyltransferase 2α; ACSL3, acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 3; SCD1, stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1; MUFA-CoAs, Monounsaturated fatty acyl-CoAs; PE-MUFA, phosphatidylethanolamine monounsaturated fatty acid. Created with BioRender.com (accessed on 31 January 2024).

GPX4/Glutathione/Cysteine

Glutathione peroxidases (GPXs) belong to the selenoprotein family, containing selenocysteine (Sec) in their redox active motifs [187]. These enzymes reduce hydroperoxides, including H2O2, to their alcohol derivates using two glutathione molecules that are consequently oxidated to glutathione disulfide (GSSG) [188]. In humans, there are eight GPX isoforms, with five enzymes (GPX1-4, GPX6) that are selenoproteins harboring Sec residues and one, GPX5, with cysteine (reviewed in [189]). They display distinct localizations: all isoforms are cytosolic; some localize also in the nucleus (GPX1-2 and GPX4) or in the mitochondria (GPX1 and GPX4). Furthermore, GPX3 is secreted from cells and GPX4 is present within the cell membranes. GPX4, originally called phospholipid hydroperoxide GPX (PHGPX4), directly reduces peroxidized phospholipids (PLOOH), even those present in membranes, to lipid alcohol (PLOH) and it is now considered an integral membrane system of resistance to oxidative stress-induced PLOOH [190]; of note, this activity could not be replaced by other GPXs or redox-active enzymes [191]. GPX4 harbors eight nucleophilic amino acids (one selenocysteine and seven cysteines); thus, it can react with numerous electrophiles [146]. Schnurr et al. provided the first evidence that GPX4 activity in a reconstituted model system can be coupled to reducing hydroperoxy ester lipids generated by LOX15, one isoform of the lipoxygenase family [192], which, as reported above, can produce pro-ferroptotic 15-HpETE-PE molecules. In 2003, other papers reported that GPX4 is an essential antioxidant enzyme [193,194], demonstrating that GPX4 knockout mice were embryonic lethal and that cells lacking GPX4 produced high levels of lipid hydroperoxides and were highly sensitive to oxidative stress [195,196]. Another study demonstrated that α-tocopherol (α-Toc), the major antioxidant in membrane compartments, can rescue cell lethality due to GPX4 deficiency [197]. In that paper, it was also demonstrated that cell death in GPX4-knockout cells was significantly accelerated by arachidonic acid and linoleic acid and that functional 12/15-LOX enzymes were required for death induction since a general lipoxygenase inhibitor prevented cell death. Further analyses implicate the apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) as a mediator of this type of cell death [197]. Thus, inactivation of the GPX4 system seems to be generally implicated in different types of cell death, like apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis, as well as ferroptosis, suggesting a possible context-related role of GPX4 [189]. Regarding ferroptosis, in 2014, a paper was published demonstrating that GPX4, when overexpressed, represents a crucial anti-peroxidant system, able to reduce the process of ferroptosis induced by different compounds called ferroptosis inducers (FINs) [198]. At the genetic level, the principal direct evidence that GPX4 knockdown pushes ferroptotic-related cell death comes from the work of Angeli et al. [199]. In this paper, the authors used inducible GPX4 (−/−) mice and demonstrated the essential role of the GPX4/glutathione axis in preventing lipid peroxidation; indeed, mice lacking GPX4 undergo acute renal failure and early death: a clear initial implication of ferroptosis in pathological processes [199]. Moreover, in the cancer field, direct inhibitors of GPX4 expression/activity have been actively searched and many compounds, now called Class-II FINs, have been proposed thus far (e.g., ML162, ML210, FIN56, FINO2, and RSL3), with promising results in vitro and in vivo [198,200]. The rationale behind this is based on the fact that cancer cells normally exhibit a basal increase in ROS/RNS levels and this condition is essentially dependent on multiple scavenging systems, and thus, a further increase in ROS/RNS production renders cancer cells more sensitive to anticancer drugs driving oxidative stress [201,202].

Both GSH and cysteine, the amino acid precursor of GSH, can coordinate antioxidant GPX4 activity during ferroptosis. Pioneering studies by Dixon et al. firstly linked GSH/thiol metabolism to ferroptosis [11]. Glutathione is an obligate cofactor for GPX4 and mounting evidence suggests that GSH biosynthesis as well as cysteine imports and/or synthesis critically mediates the response of GPX4 to ferroptosis inducers (reviewed in [133]). The catalytic cycle of GPX4 indeed implicates a first GSH-dependent reduction of the reactive selenic acid (-SeOH) generated by a reaction between the peroxide moiety and the GPX4-selenol (-SeH) group, creating the intermediate GPX4-selenide disulfide (-Se-SG). A second GSH is then used to regenerate the GPX4-SeH group and the oxidated GSH is released as GSSG [191]; therefore, two glutathione are necessary in the catalytic cycle. Consistent with this, processes and/or drugs that specifically enhance intracellular GSH levels can rescue ferroptosis cell death, whereas depletion of GSH is an important contributor to death initiation and execution [133].

Here, we briefly discuss GSH and cysteine metabolism as was also discussed in other recent reviews [133,203,204]. The tripeptide GSH containing Glu, Cys, and Gly amino acids is produced in a two-step process involving two different enzymes, glutamate-cysteine ligase (GCL), which is composed of a catalytic γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase (γ-GCS) and modifier (GCLM) subunits, and glutathione synthase (GSS). The rate-limiting enzyme of GSH synthesis is γ-GCS, involved in the first step, and it has been found that in some conditions, buthionine sulfoximine (BSO) can induce ferroptosis by inhibiting this enzyme [198]. The GSH antioxidant activity is due to its essential role as a cofactor for multiple antioxidant proteins, including GPXs, GSH S-transferases, and glutaredoxins [205]. Furthermore, GSH depletion can trigger labile iron increase: this can be related to the fact that GSH can bind free iron and this complex is then recruited by the adaptor protein poly(rC) binding protein 1 (PCBP1) that delivers ferrous iron to ferritin for storage [206,207].

Cysteine (Cys) availability regulates the de novo synthesis of GSH [101,208]. One of the major systems that increase the intracellular amounts of cysteine is represented by the Xc- system, a Na+-independent cystine/glutamate antiporter. This is a transmembrane heterodimer, composed of two subunits (SLC7A11 and SLC3A2) linked by disulfide, that can exchange a molecule of cystine, the dipeptide precursor of cysteine, with one of glutamate, in an ATP-dependent manner [11,209,210]. Imported cystine is then reduced to cysteine by the action of specific cytosolic cystine reductases, including thioredoxin 1 (TRX1) and a specific thioredoxin-related protein (TRP14) [211]. A downstream consequence of system Xc- inhibition is a rapid drop of GSH levels causing ferroptosis/cell death in most cancer cells [11,48,107,212] and tumor suppression [213]. Indeed, Xc- system represents a predominant route for the cystine import process, and numerous papers demonstrated that increased SLC7A11 expression/function enables cells to survive under different types of stressful conditions, preserving the GSH content and redox homeostasis (reviewed in [214]). Accordingly, most of the Class-I FINs, such as erastin and many analogs like sulfasalazine and sorafenib that block the Xc- system via direct SLC7A11 targeting, trigger ferroptosis, as a consequence of disabled GSH/GPX4 function [48,215]. However, more recently, Yan et al. demonstrated that different expression levels of SLC7A11 dictate protection or death under H2O2 treatments in glucose-depleted cancer cells, with low levels associated with protection and high levels with death. In this latter condition, toxicity may rely on NADPH depletion (required for cystine reduction) and disulfide stress, potentially due to cystine and GSSG increase. In vivo data further demonstrated that high SLC7A11 promoted primary tumor growth but repressed tumor metastasis [216]. In addition, cells can import cystines derived from the γ-glutamyl cycle in which cysteine (readily oxidated to cystine) is liberated from extracellular glutathione through the activities of the two enzymes γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) and dipeptidase (DP) [217]. Very recently, GGT1 has been implicated in modulating ferroptosis in glioblastoma [218]. In fact, cystine deprivation-induced ferroptosis was favored by GGT1 inactivation (pharmacological inhibition or deletion) in high-density cells and viability was restored through a supply of cysteinyl-glycine, the GGT1 cleavage product [218]. In another work, over-expression of GGT1 restrained ferroptosis and autophagy induced in retinal ganglion RGC-5 cells by oxygen-glucose deprivation/reoxygenation treatment and this was mediated by a direct interaction with the GCLC enzyme [219]. It is important to note that aside from GSH, cysteine is used for the biosynthesis of proteins, iron–sulfur clusters, and heme, as well as the production of taurine and coenzyme A metabolites, raising the possibility that the observed antiproliferative effects due to cystine depletion could also be related to a decrease of such crucial molecules [195,203,204,220,221]. Cysteine could be also exported out of the cells through neutral amino acid transport systems, such as SLC38A2 [222], which indicates that a low cysteine level in these cells is dynamically controlled [212].

The transsulfuration pathway (TSP) represents an important metabolic cascade implicated in the de novo biosynthesis of cysteine [223]. This pathway produces cysteine from homocysteine, a molecule originating from dietary methionine, an essential amino acid. In mammals, this metabolism represents a unique endogenous source of cysteine, and the reactions involving the transfer of sulfur to serine are catalyzed by two enzymes, cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) and cystathionine γ-lyase (CGL/CSE) [224]. By condensing homocysteine with serine, CBS generates the intermediate cystathionine, which becomes the substrate for CGL and liberates cysteine, α-ketobutyrate, and NH4+. The importance of the TSP pathway was discovered by the Stockwell group through siRNA screening for genes involved in suppressing erastin-induced ferroptosis. They identified the cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase (CARS) as a gene knockdown that can prevent erastin-induced ferroptosis in different cell contexts [225]. The absence of CARS inhibited the generation of lipid ROS in erastin-treated cells, without affecting ferroptosis triggered by GPX4 inhibitors (RSL3 and FIN56) or influencing iron homeostasis. Indeed, CARS knockdown prevents ferroptosis through activation of the TSP pathway by increasing intracellular cysteine and supplementing the glutathione content (GSH and GSSG); this consequently supports GPX4 activity, thus rescuing in turn erastin-induced ferroptosis [225]. Also, Wang et al. demonstrated that inactivation of CBS by a specific inhibitor (named CH004) induced ferroptosis in HepG2 cells and in liver tumor xenograft mouse models [226]. Other recent papers have linked the transsulfuration pathway to ferroptosis resistance. For example, the protein DJ-1/PARK7, an anti-oxidative stress gene, protects cancer cells from ferroptosis by preserving the activity of S-adenosyl homocysteine hydrolase, a hydrolase specific for S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine that produces homocysteine, hence maintaining cysteine synthesized from the TSP pathway by fueling GSH synthesis [227]. DJ-1 has also been implicated in mediating the NRF2/GPX4 signaling pathway to prevent ferroptosis [228]. Of note, cystathionine is also a substrate of system Xc- activity [229] and can protect against oxidative stress, especially in the immune system [230]. In general, the TSP pathways and downstream cysteine have multifaced roles, as recently reviewed elsewhere [223]. In conclusion, the GPX4/glutathione/cysteine axis represents a major determinant for defenses against ferroptosis and transcription factors, like NRF2, ATF4, and JUN (as discussed in the next section), that have emerged as important regulators of antioxidant-defenses in ferroptosis by controlling the systems that replenish GSH content.

Peroxiredoxin 6 (H2O2 and Lipid Peroxides Decomposition and Repair of Membrane)