Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a leading cause of dementia, has been a global concern. AD is associated with the involvement of the central nervous system that causes the characteristic impaired memory, cognitive deficits, and behavioral abnormalities. These abnormalities caused by AD is known to be attributed by extracellular aggregates of amyloid beta plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles. Additionally, genetic factors such as abnormality in the expression of APOE, APP, BACE1, PSEN-1, and PSEN-2 play a role in the disease. As the current treatment aims to treat the symptoms and to slow the disease progression, there has been a continuous search for new nutraceutical agent or medicine to help prevent and cure AD pathology. In this quest, honey has emerged as a powerful nootropic agent. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the high flavonoids and phenolic acids content in honey exerts its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective properties. This review summarizes the effect of main flavonoid compounds found in honey on the physiological functioning of the central nervous system, and the effect of honey intake on memory and cognition in various animal model. This review provides a new insight on the potential of honey to prevent AD pathology, as well as to ameliorate the damage in the developed AD.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder associated with damage to the brain areas such as the cerebral cortex, temporal lobe, hippocampus, amygdala, entorhinal cortex (EC), and parahippocampal region [1,2]. The disease is mainly characterized by impaired memory and cognitive deficits [3,4]. AD is considered the most common cause of dementia, accounting for about 60–70% of the total cases worldwide [5]. In addition to the deficits of memory and cognition, AD is also accompanied by behavioral changes. Since most of the areas affected by the pathology are involved both in cognition and behavior, the predominant behavioral changes, such as agitation, dysphoria, and apathy, are correlated highly with cognitive dysfunction [6].

Previous studies have proposed several effective solutions to reduce the deposition of amyloid fibrils, minimize oxidative stress and neuroinflammation, and/or improve memory and cognition. These can be divided into drugs and antioxidants or neuroprotective agents for ease of discussion. The drugs include N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors antagonists [7,8], agents acting on the acetylcholinergic system (ACh system) [9,10], anti-amyloid [11], and anti-tau [12]. The antioxidants or neuroprotective agents include idebenone (an organic compound from the quinone family) and α-tocopherol [13], estrogen analogues [14,15], and honey [16,17,18]. Although the allopathic medications have shown promising results in attenuating symptoms, they may cause a number of adverse effects while having some serious precautions and contraindications [10,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Comparably, honey only has one serious adverse effect that ranges from mild hypersensitivity reaction to anaphylactic shock, which is attributed to the presence of pollens and bee-derived proteins in honey [26]. These allergic reactions, however, are very rare with only a small number of cases reported till date [26,27,28]. Additionally, among all the above mentioned substances, honey stands out by having the potential to improve almost all aspects of AD, such as oxidative stress [29,30,31], neuroinflammation [32,33], neuroprotection [34,35], ACh system [36], and memory and cognition [37,38].

As AD is associated with the involvement of the central nervous system (CNS) that causes the characteristic impaired memory, cognitive deficits, and behavioral abnormalities, in this review article, we will limit our discussion of the effects of honey on the said aspects.

2. Pathophysiology and Clinical Picture of Alzheimer’s Disease

AD is believed to begin and caused by the accumulation of amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques; this perspective of AD progression is known as the amyloid-cascade-hypothesis [39]. According to this hypothesis, the neuropathology in AD starts from the extracellular accumulation of Aβ fibrils as abnormal neuritic plaques, the deposition of which leads to oxidative damage and inflammation. Although this is a widely accepted hypothesis, some researchers believe in the tau hypothesis, according to which tau pathology is a prerequisite for the Aβ aggregation to take place [40,41,42]. Additionally, there is a third viewpoint which suggests that there may be more than one pathological pathway co-occurring, as dementia in AD is not correlated with either plaque or tangle burden but with the serum amyloid protein content in the Aβ plaques [43,44]. This hypothesis is further supported by the findings that the neurofibrillary tangles (NFT)-bearing neocortical neurons are functionally intact [45], and even though the cognitive deficits increase with ageing, the load of neuritic plaques and NFTs tend to decline as the elderly people age, i.e., more burden in the 60–80-year-old individuals than in over 90-years old individuals [46].

Pathologically, AD is characterized by the deposition of Aβ plaques (extracellularly) and NFTs (intracellularly). Soon after the tau fibrils are hyperphosphorylated, they may be converted into pathological tau and result in the formation of NFTs [47]; the latter more commonly affects the medial limbic structures (MLS) comprised of hippocampus, subiculum, EC, and amygdala [48,49]. The tau aggregates need the presence of neuritic plaques, therefore, are likely formed adjacent to them [47], whereas NFTs have an independent presence [49]. Irrespective of the site of impaction of tangles, which may vary in the brain, the formation of the NFTs is possibly the result of the interplay of oxidative injury, neuroinflammation, ineffective degradation, and subsequent ubiquitination causing hyperphosphorylation of tau followed by the subsequent formation of tangles [50,51,52,53].

Considering the defect at the genetic level, AD results from the abnormality in the expression of five genes: Apolipoprotein E (APOE), Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP), Beta-site Amyloid precursor protein Cleaving Enzyme 1 (BACE1), Presenilin 1 and 2 (PSEN-1, and PSEN-2). While the pathology of the first gene APOE (especially the allelic variant ε4) is associated with sporadic AD [54], the latter four genes were found to be responsible for the familial AD. The most common form of AD is sporadic and its risk increases with the presence of ε4 allele [55,56]. The other alleles, i.e., ε2 and ε3, minimize oxidative damage and neuronal death, whereas, the ε4 allele has the lowest capacity to prevent cellular toxicity [57]. Therefore, its presence increases the likelihood of developing AD [57,58]. As for the familial AD, the APP gene is located on chromosome 21 and is responsible for the production of APP, which is required for the normal regulation of several cellular functions [59]; however, excessive dose, hence over-expression, of this gene results in increased amyloid levels in brain and likelihood to develop AD [60,61], as also observed in Down syndrome (trisomy 21) [62]. The other genes, BACE1 and PSEN (1 and 2), also known as β-secretase and γ-secretase, further play their part in AD pathogenesis [63,64,65]. It occurs when the APP is cleaved by BACE1 (β- secretase) instead of the normal cleavage by α-secretase, and the product acts as a substrate for γ-secretase resulting in the formation, and subsequently, aggregation of the Aβ oligomers [66,67]. Furthermore, since the β-secretase and γ-secretase act on the common substrate, the elevated level and activity of the former is mostly accompanied by a reduction in the level of the latter [68].

Overall, the damage in the brain in AD is comprised of injuries on both macroscopic and microscopic levels. The gross changes consist of a reduction of the total brain tissue with an increase in the volume of the ventricles [69,70], whereas the underlying microscopic changes include the loss of synapses [71,72], damage to pyramidal neurons, and neurodegeneration [1,73]. In addition, the loss of synapses can either occur in the presence of normal long-term potentiation (LTP) [74] or is probably due to impaired LTP [75,76]. To further shed the light on these contrasting results, recent studies described that AD may affect LTP in some pathways (e.g., Schaffer collateral) while the LTP in other pathways (e.g., mossy fibers) remain unaffected/normal [77] with a possible alteration in the short-term potentiation [78]. Moreover, AD brains are affected by oxidative injury and inflammatory damage. The former is due to an imbalance between antioxidants and oxidation-causing substances (i.e., free radicals and reactive oxygen species), causing a reduction in the activity of antioxidants such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione (GSH), and catalase, together with an increase in the markers of oxidative damage such as Malondialdehyde (MDA) (the product of lipid peroxidation) and 3-nitrotyrosine (the end product of protein oxidation), and 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine and 8-hydroxyguanosine (the product of oxidation of guanine in DNA) [79,80,81]. Likewise, perpetual neuroinflammation marked by an imbalance in the inflammatory cytokines is also evident by the over-expression of the pro-inflammatory markers, such as IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6 [82,83], TNFα, and NFκB [84,85], and an accompanied under-expression of some anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-10 [86,87]. Moreover, the reduced level of anti-inflammatory cytokines further leads to the uninhibited activity of pro-inflammatory cytokines [87,88,89] and results in more neuronal damage [87]. Furthermore, an altered interaction of cytokines (both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory) has been observed based on the underlying pathology of APOE genotypes [90,91].

Those mentioned structural and functional abnormalities that are the characteristic features of AD can start appearing in the brain in middle-aged individuals (familial or early-onset AD) or the elderly (sporadic or late-onset AD). Irrespective of the age of onset, clinically, AD presents as deficits of memory, cognition [48,92], and behavior [6].

3. Honey and Its Powerful Ingredients—The Phenolic Compounds

Honey mainly contains sugar and water [93]. The high sugar content, comprised of dextrose, levulose, and other complex carbohydrates, makes it a better alternative to glucose as it replenishes energy with a constant blood glucose level [94]. In addition to being a mixture of around 30 different kinds of sugars [95], honey has several minor components, including phenolic compounds, proteins, amino acids, vitamins, enzymes, and minerals [93,96]. Although the main constituents (water and sugars) remain the same, the composition of minor components of each honey type varies significantly, which is due to the difference in geographical location, floral source, storage, and the final color [95,97]. Due to the mentioned factors, various types of honey are different in composition of polyphenolic compounds [98,99], and therefore, polyphenolic activity and total antioxidant capacity (TAC). The quantification of total phenolic content showed that certain types of honey, such as, stingless bee honey and Tualang honey have higher content of phenolic acids and flavonoids, and greater TAC and radical scavenging activity [100,101,102,103] which may indicate more potential in attenuation of oxidative stress in vivo as well. To our knowledge, presently, no study has been conducted comparing antioxidant effects of various types of honey in vivo. Moreover, the composition of the same variant of honey has not been compared from different regions around the world so far, which points toward a likelihood of varied composition of honey obtained from two different countries.

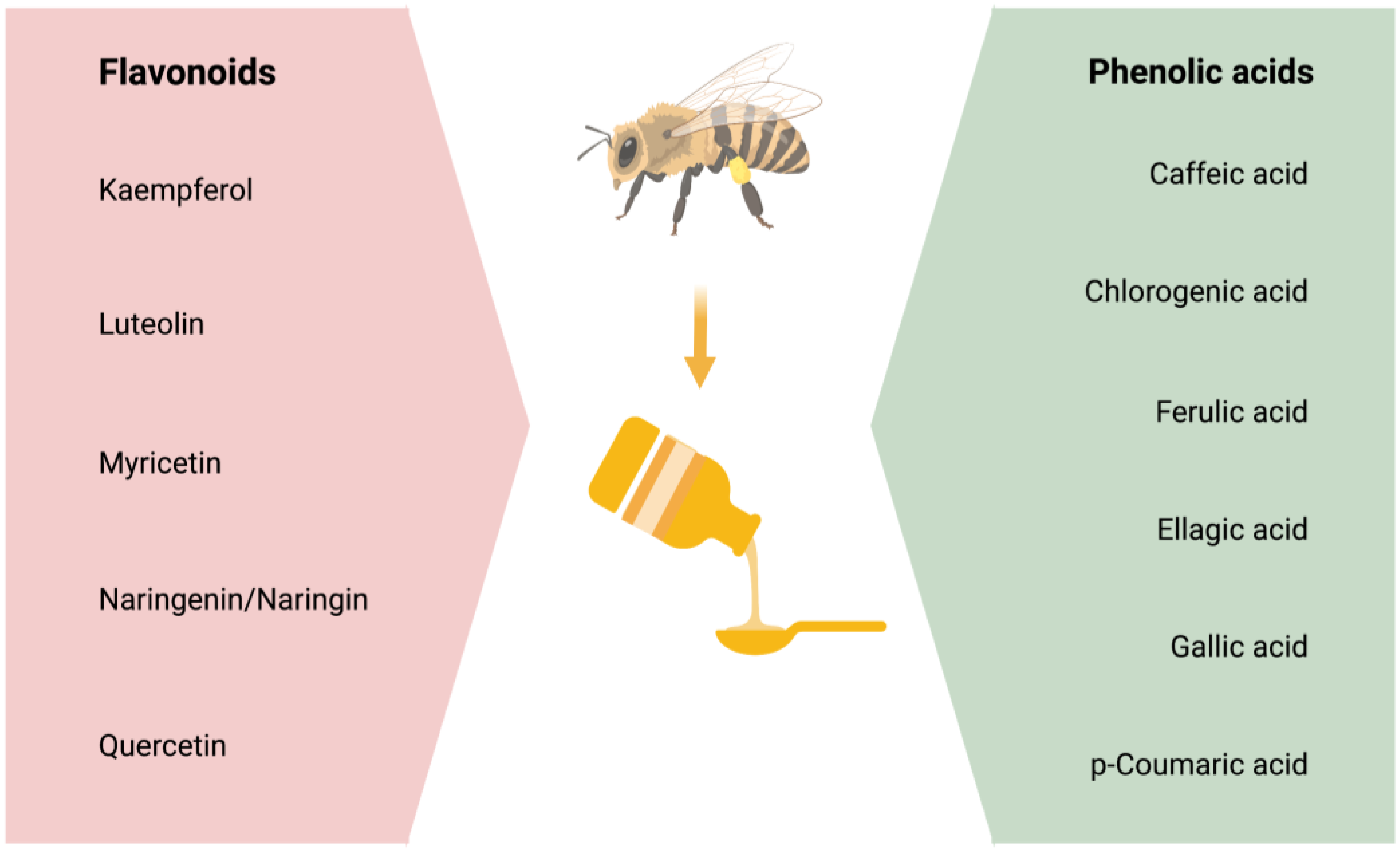

Studies suggest that most of honey’s antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective properties are due to its phenolic content [104,105]. Phenolic compounds are comprised of four classes of polyphenols: Phenolic acids, flavonoids, stilbenes, and lignans. Out of these, phenolic acids and flavonoids primarily have the potential to act as antioxidants and reduce oxidative stress [29,30,31] and neuroinflammation [32] that are the mediators of insults to the brain in the neurodegenerative diseases [106,107]. However, this review will focus on the effectiveness of flavonoids and phenolic acids on the CNS and in the prevention/treatment of AD pathology. The main phenolic compounds affecting the physiological functioning and/or the pathophysiology of the CNS are stated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The phenolic compounds, which comprises of flavonoids and phenolic acids.

According to the studies on AD models (Refer to Table 1 and Table 2), all mentioned flavonoids and phenolic acids exert antioxidant effects and show neuroprotective activity. All agents, except myricetin, were also found to exhibit anti-inflammatory potential. As myricetin possesses an anti-inflammatory ability against post-ischemic neurodegeneration [108], if tested, it may also display similar potential in AD brain. In addition to the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential, most polyphenolic components also proved to attenuate AD pathology by decreasing amyloid deposition, with an exception of kaempferol and chlorogenic acid. Additionally, naringenin, naringin, quercetin, caffeic acid, and ellagic acid also reduce levels of p-tau in AD brain.

Table 1.

Main flavonoid compounds affecting the physiological functioning and/or the pathophysiology of the central nervous system.

Table 2.

Main phenolic acid compounds affecting the physiological functioning and/or the pathophysiology of the central nervous system.

4. Therapeutic Potential of Flavonoids and Phenolic Acids

Several polyphenols are known to exert protective effects on the nervous system and are suggested to have a role in alleviating symptoms of neurological diseases [159,160,161] including AD [162]. All these phenolic compounds, which are listed in Figure 1, are found to improve cognitive performance in AD pathology, and prevents from cognitive decline when ingested before inception of disease. These compounds are found in different kinds of honey in addition to other sources, and are particularly effective in attenuating oxidative stress along with exerting preventive effects on several other mechanisms in AD pathology. Their potential to reduce AD-induced brain injury is further proven by the microscopic studies and brain assays where they showed neuroprotective effects on the cortex [116,140], hippocampus [124,125], and hypothalamus [119]. Moreover, the consumption of polyphenols resulted in the prevention of hypoperfusion injury [145] with a generalized increment in cell number having normal physiology in the subiculum [122], and hippocampal proper area CA1 [48,136,139,154], CA3, and dentate gyrus [109,120,157], along with preserving normal synapses [112,131,144], the latter is further evident by an increased LTP after polyphenol consumption [154,156,158,163]. Further, the detailed studies of AD-brain animal model showed the potential of the polyphenols to reduce oxidation markers such as MDA [128,153], nitric oxide (NO), and nitrite [112,119,129,130], thereby attenuating free-radical-induced oxidation insults. The observed levels of antioxidants, however, are contrasting, with many studies deducing an elevated level of SOD and catalase, GSH [113,127,140,143,152,155], whereas others concluding decreased expression [115,146,148]. Although the results are contradictory, the studies demonstrating a reduction in the activity of antioxidants claim that this decrease also signifies the attenuation of oxidative injury, which subsequently renders the expression of the anti-inflammatory markers unnecessary. However, despite the discrepancy in the results, all studies conclude that the changes in the expression of these markers lead to reduced oxidative damage and Aβ-plaque accumulation.

Moreover, phenolic compounds can also alter the expression of some critical genes: APP, BACE1, PSEN-1, and Glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPx1). Polyphenols are found to down-regulate the expression of APP [164] and PSEN-1 gene [165], along with either a decrease [142,146,148] or increase in GPx1 expression [116]. As GPx1 is an enzyme that catalyzes the reduction of hydroperoxides and hydrogen peroxide by GSH to attenuate oxidation [166], reduced expression can lead to oxidative injury to cell. Moreover, the expression of BACE1 is also decreased [153] and is thought to be inhibited post-transcription, probably at the protein level [148]. Although not studied yet, a similar down-regulation of PSEN-2 gene expression can be expected by polyphenol consumption [167]. Moreover, polyphenols may also prevent neuritic plaque deposition by increasing α-secretase activity and by reducing cleavage of the APP to amyloidogenic soluble APP-β and β-CTFs [142] and hence, preventing the accumulation of the latter in synapses [148,165]. Taken together, these studies suggest that the polyphenols likely regulate gene expressions to reduce oxidation and formation of Aβ fibrils. Moreover, the polyphenols also increase the expression of the transcription factor Nrf2, which is responsible for regulating the induction of antioxidant genes, thereby improving defense against oxidative injury [139]. To protect the CNS further, the polyphenols reduce the level of pro-inflammatory markers, such as NFκB, TLR4 [139,157], COX-2 [151], MHC class II, TNFα [114,127,146], IL-1α [149], IL-1β [147,151,168], IL-6 [157,169] and increase anti-inflammatory cytokines [115], thereby reducing neuroinflammation. Furthermore, by decreasing neuroinflammation, these substances also attenuate the immunoreactivity of microglia and astroglia in the hippocampus, EC, and amygdala, which is commonly observed in AD neuropathology [115,122,142,146,149,150].

Additionally, the polyphenols reduce tau hyperphosphorylation and subsequent formation of NFT [170] and decrease the deposition of Aβ-plaques [140,156,171]. They also seem to exert a neuroprotective effect by preventing neuronal injury [136,152] and apoptosis [119,136,151] and by regulating the ACh system, where they increase ACh and choline acetyltransferase (ChAT), and decrease acetylcholinesterase (AChE) [119,123] and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) [153]. These polyphenols’ effects also lead to minimization of deficits of memory and cognitive [172,173,174,175]. As honey contains a number of these polyphenols, its consumption can be expected to have similar potential to prevent and treat CNS pathology in AD. The therapeutic potential of the polyphenols: flavonoids and phenolic acids, are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

The effectiveness of honey in minimizing neurodegeneration is attributed to its neuroprotective effects on the brain [30,34], including the prefrontal cortex [176,177,178] and hippocampus [34,35,179,180]. Honey prevents neurodegeneration by attenuating two main phenomena, which are oxidative stress and neuroinflammation [36,132]. The reduction in neuroinflammation [181] is due to the attenuation of oxidative stress [30,31] and the prevention of free radical-mediated injury to the brain tissue [182,183]. This effect is evident by an increase in the antioxidant enzyme such as SOD and a reduction in the oxidative-stress markers, such as plasma MDA and protein carbonyl in aged brains [176,177]. Subsequently, as the hippocampal pyramidal neurons are highly susceptible to oxidative damage, this reduction of oxidative stress probably rescues them from insult and degeneration [34,182].

Further, along with the hippocampus, injury to the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and piriform cortex is commonly observed in AD, both of which are associated with memory and cognition. Unlike other primary sensory cortices, which are minimally affected by the AD pathology, the piriform cortex is possibly affected even before or along with the development of the cognitive symptoms [184,185,186]. Hence, it is also considered a predictive marker of the conversion to AD [184,187]. Similarly, the damage to the mPFC in AD is evident as defective functioning [188,189] and abnormal connectivity with other associated brain areas [190]. Even though no such study has been undertaken to look at the injuries in these areas, the neuroprotective effects of honey may also rescue the mPFC and piriform cortical injury.

Although researchers widely accept the neuroprotective capacity of honey, we still do not have much data on the effects of honey on the physiology and/or anatomy of the human brain, and, therefore, its potential to act on the CNS is not fully understood to date. It is probably due to the late advent of technologies to study the brain in honey-related research and the limitation to researching human CNS. However, to overcome the limitation of experimental access to the human brains and to understand the possible effect of honey on the microscopic level, the research is now predominantly being carried out in rodents.

5. Effects of Honey on Memory, Cognition, and Behavior

Cortical Aβ deposition exerts effects on temporal lobe atrophy and resultant cognitive impairment in individuals with AD [191]. From psychophysiological perspective, cognition, learning, and memory are believed to be mainly determined by the cortico-hippocampal (C-H) circuit’s normal functioning [192,193]. As ACh is the principal neurotransmitter in synapses, the amount of ACh also plays an essential role in learning behavior and cognitive performance [194]. Although relatively constant, the amount of ACh still normally fluctuates, according to the need in the memory processes, such as encoding and retrieval [195]. Essentially, since the integrity of the C-H circuit depends upon the normal physiology of neurons and synapses, the Aβ plaque formation, and therefore AD, may affect the circuit by damaging neurons [196], reducing the number of cholinergic neurons [197], decreasing the ChAT activity [198,199], decreasing ACh release [200], and impairing synapses, which results in defective transmission [72,74]. Surprisingly, ageing and Aβ fibrillogenesis also decrease the AChE activity [201,202]; this finding is unexpected and in contrast to the decreased ACh indicates that the reduction in ACh is likely due to degeneration of the cholinergic neurons along with an increase in another cholinesterase enzyme activity, such as BChE [203] and not due to elevated AChE levels, as the latter is itself hydrolyzed by the former [204,205]. The intake of honey is found to reduce the level of BChE with a further decline in the level of AChE [176,206]. Although the exact mode of action is still not understood, this cholinesterase inhibition, together with neuroprotection, results in improved cognition and memory [207] after honey consumption, as observed in rodents [180,182,208,209] and humans [37,210]. The effects of honey as a nutraceutical agent in improving memory and cognition are further discussed in Table 3 (in rodents) and Table 4 (in humans).

Table 3.

Effects of honey intake on memory and cognition in animal model.

Table 4.

Effects of honey consumption on memory and cognition in humans.

6. Honey on Dopaminergic Neurons—Important Players in Memory Deficits in AD

In addition to ACh, dopamine plays a significant role in learning and memory functions. Besides being secreted from dopaminergic neurons (DN) of the Ventral tegmental area (VTA) and substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpC) in the midbrain [216,217], dopamine is also released by locus coeruleus (LC), located in the brainstem, which co-releases dopamine along with noradrenaline [218,219]; this released dopamine from LC innervates CA3 [220], and is thought to be the primary source of supply to the dorsal hippocampus [218,221]; however, a recent study suggests that the midbrain modulate dopaminergic innervation to the dorsal hippocampus and this stimulation is sufficient to arouse aversive memory even in the absence of input from LC [216]. To aid with the understanding of the contrasting source of dopamine, Takeuchi et al. proposed that although the projection of dopaminergic fibers from LC is denser than the midbrain [221], the midbrain and LC both modulate dorsal hippocampus in different kinds of memory consolidation processes [222]. Since the DN in the VTA are the primary site for dopamine synthesis, the DN in the midbrain-hippocampal (M-H) loop are vital in learning, memory formation, and consolidation [223,224]. The DN, and the secreted dopamine, modulate synaptic plasticity and contribute to the LTP in the hippocampus [225], thereby playing an essential part in the genesis and fortification of the episodic [226], aversive [216], and spatial memories [224]. Moreover, dopamine, together with norepinephrine, is crucial for the recognition memory [227,228]. In non-diseased brains, the number of DN and, therefore, the functional connectivity of the midbrain tends to decline with age [229,230], which may appear as deficits in learning and memory [231]. Similarly, as AD is a disease of old age, there is degeneration of DN [232,233]; However, due to the Aβ pathology, probably more damage occurs to the dopaminergic synapses in the M-H loop. Due to the mentioned insult, there is a decrease in dopamine, leading to impaired synaptic plasticity [234,235] and deficits of memory [233,236]. Polyphenols are found to prevent the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons and increase dopamine levels [137,237,238,239,240,241]. Although all these studies discuss the attenuation of neuroinflammation with/without Parkinson’s disease, similar results are expected in the AD model. As the insults to DN and reduced dopamine in AD are recently being studied in detail, more research is encouraged to be conducted on the AD M-H loop to understand the effect of honey and its constituent polyphenols on memory improvement in AD.

7. Honey as a Nootropic Agent—Prevention, Treatment, or Both?

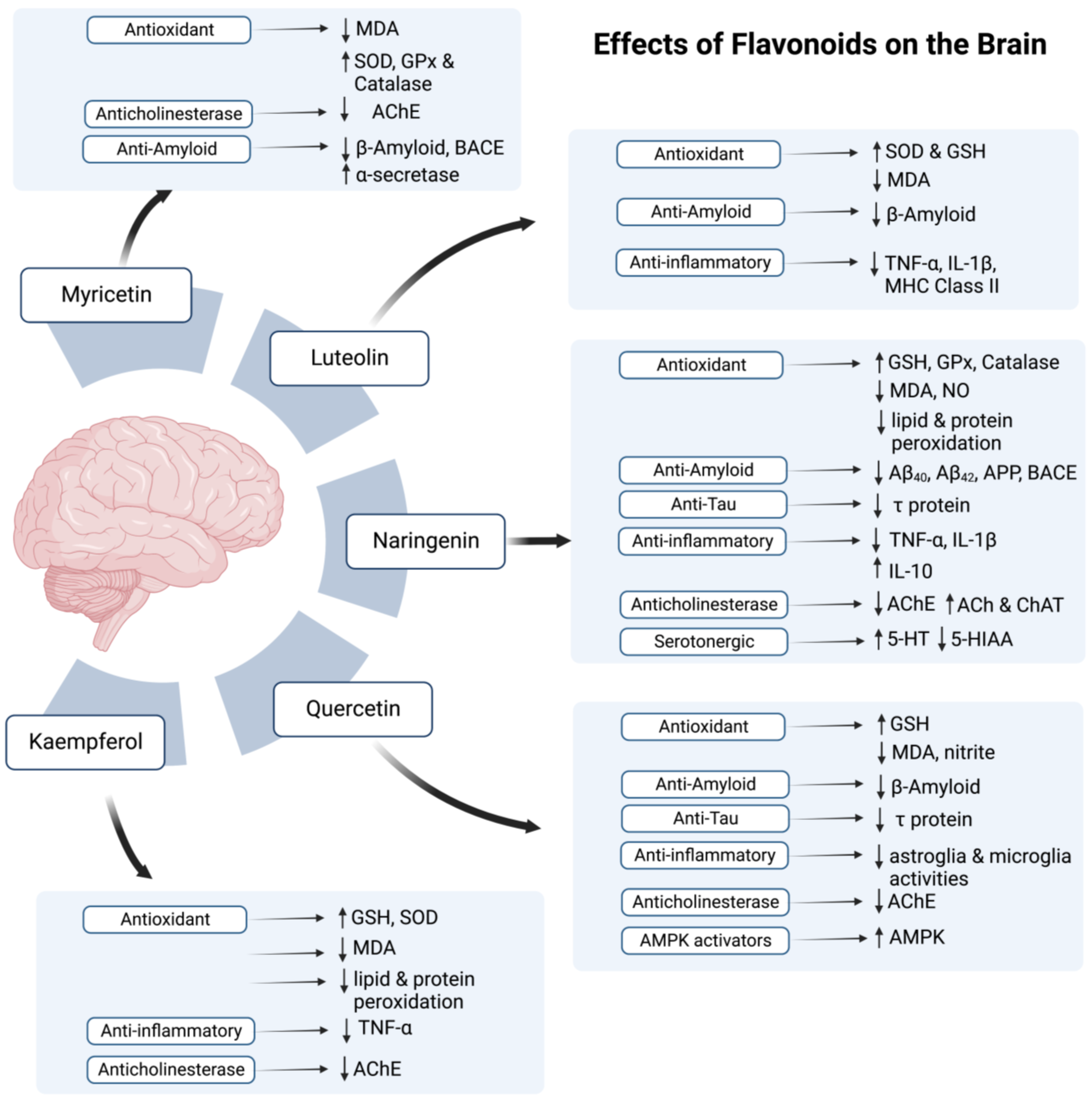

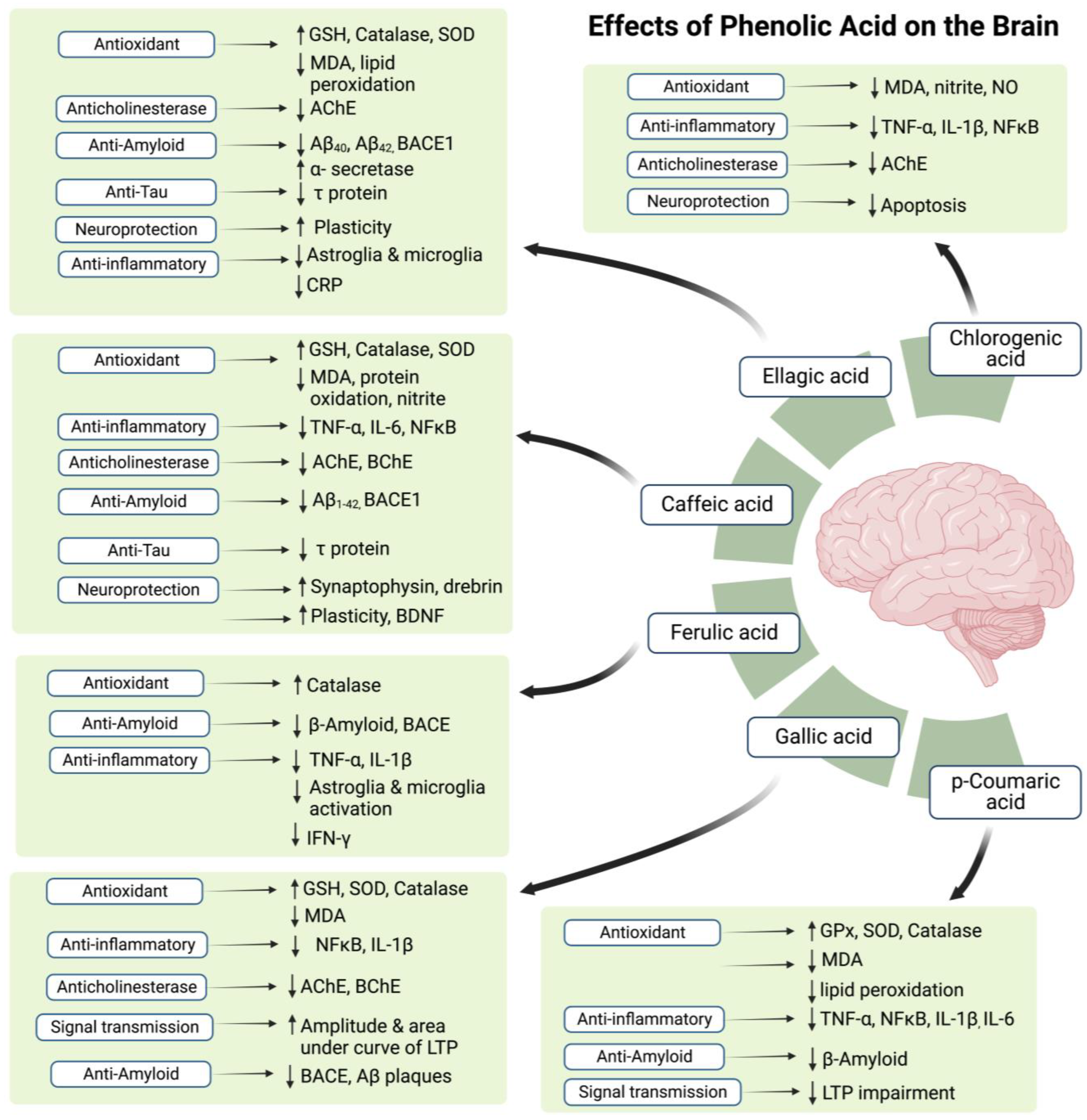

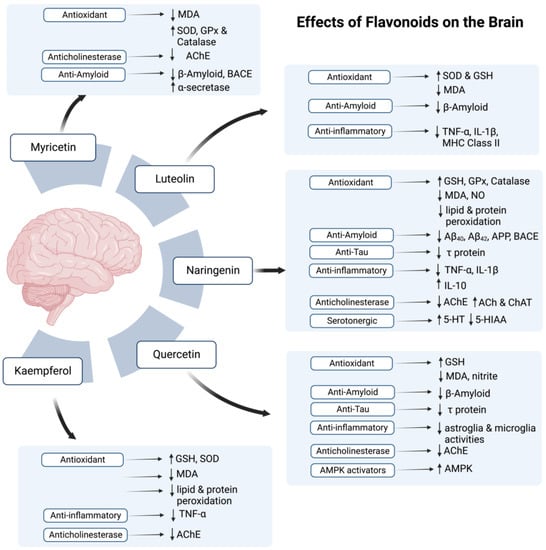

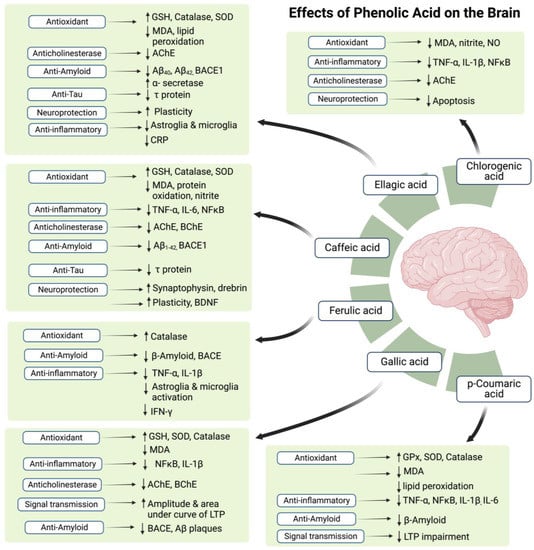

In light of the previous research, it is evident that by acting on the CNS and working through various mechanisms, honey acts as a nootropic agent (refer Figure 2 and Figure 3). Now the question arises of the right time to utilize these nootropic properties to alleviate AD symptoms. Another similar issue is understanding whether honey consumption is effective in preventing the development/conversion of mild cognitive impairment into AD, mitigating the damage during ongoing AD disease pathology or reversing the injury done to the brain by AD. Although, to our knowledge, this aspect is not assessed to date, the studies on polyphenols (discussed in Table 1 and Table 2) may suggest some possible effects. The intake of phenolic compounds before initiation of the AD neuropathology is found to halt the progression of the CNS disease, protect neurons, reduce neuroinflammation and oxidative damage, and minimize memory and cognitive deficits, as seen in the studies on the AD-rodent models [48,109,111,112,117]. Likewise, honey ingestion in subjects with developed AD may also cause effects similar to those observed in the polyphenols-treated AD model [121,122,125,126]. Since these polyphenols are abundant in honey, we can expect the same benefits with honey consumption in human subjects.

Figure 2.

The possible effects of flavonoids in honey on the brain. Symbol (↑) represents increase while (↓) represents decrease.

Figure 3.

The possible effects of phenolic acids in honey on the brain. Symbol (↑) represents increase while (↓) represents decrease.

Although honey is loaded with various kinds of polyphenols [100,102,103], the protective or curative effect of honey can be enhanced further by consuming it in combination with some nutraceutical agent [182,210,242]. Moreover, the synthesis of dimer by combining caffeic acid and ferulic acid [243], and the use of an amino acid (glutamine) conjugated with phenolic acid [244], both of which proved to be more efficient than the polyphenol alone, have paved a path for the likelihood of the advent of similar new combinations with honey that might emerge as the novel therapies for the prevention of AD. Moreover, a mixture of honey with other nutraceutical substances has proven to be effective in AD (for review: [245,246,247]) and can be appraised in prevention and/or management of AD.

In the same notion, the accurate dose of honey to prevent and/or treat AD has not been deduced to date. One of the important reasons of inability to draw conclusions is the fact that most studies are conducted on rodents, with very few studies on human subjects. Moreover, many confounding factors need to be addressed, such as the type of honey to be ingested, the therapeutic dose of honey, the minimum duration of honey intake, stage of AD (if given for treatment). Since few studies mentioned in Table 4 use a formulation of honey and other nootropic agents, another question arises whether combinations with such agents are more effective in terms of dosage and duration in improving human cognition. To our knowledge, currently there are no known studies on primates that observe the benefits of honey on cognition, or sporadic AD which is best modeled by the rhesus monkeys [248]. Comparative studies are encouraged in these areas, with possible usage of primates such as chimpanzees etc., to observe and deduce invaluable conclusions.

8. Conclusions and Future Directions

The phenolic compounds prevent damage to the neurons while promoting apoptosis in dysfunctional or cancer cells, which points toward different mechanisms of action in the brain cells than the rest of the body. On the same notion, the polyphenols are believed to exhibit oxidation-promoting properties for review: [249], rendering it necessary to explore the reasons for the switch between pro-oxidant and antioxidant characteristics to utilize these novel qualities appropriately. However, as various polyphenols have anti-amyloid and anti-tau potential, there is a possibility that they function as antioxidants in the cells that contain (or may contain) the Aβ aggregates and NFTs, whereas they promote oxidation in other abnormal cells; this aspect of these substances, as well as that of honey, needs further elaboration.

Some recent studies have demonstrated the potential of flavonoids in prevention of memory decline in elderly individuals [250,251,252,253]. Similarly, the research on animal models of AD (mentioned in Table 1 and Table 2) have shown an effectiveness of polyphenols in prevent and/or treat AD symptoms. However, the source of phenolic compounds in all these studies are variable. Considering the fact that the phenolic compounds can be obtained from various sources, notably fruits, vegetables, beverages, and nuts [254,255], the same polyphenols from distinct sources may have different pharmacological activities, and their polyphenolic potential, especially the capacity to act as an anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory agent, may also vary accordingly. In the light of these considerations, new studies focusing primarily on the flavonoids and phenolic acids derived from honey are highly encouraged to understand the polyphenolic potential of honey.

Although an increased level of AChE is observed in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of AD patients [256], an overall reduction of AChE concentration is found in the AD brain [201,202]. The reduced amount of AChE suggests that AD pathology can be due to the reduction of some neuroprotective variant of AChE (e.g., AChE-R) in the absence of an increase in AChE activity [202]. Taking this into consideration, although the most reliable drug to treat mild to moderate AD is donepezil, an AChE inhibitor, it paradoxically increases the amount of AChE in the CSF [257,258]. These findings suggest that the AChE could have different properties inside the brain and within the CSF, pointing toward the possibility that the effect of honey on memory and cognition is due to neuroprotection with/without some mechanism other than AChE inhibition.

The role of dopaminergic system has been studied for a long time; however, its importance in memory deficits in AD was not clear. With the new studies on the role of dopaminergic system in learning and memory, a decline in dopamine levels with the damage in synapses is observed in AD. Furthermore, it is found that restoration of the dopaminergic levels is associated with improvement of memory deficits in AD [259]. For this purpose, dopamine agonists are being tested and proven to reverse the memory-related symptoms [260,261]. Moreover, the dopamine and its derivatives are found effective to reverse oxidative stress, inflammation, and Aβ load [262]. However, the dopamine replacement methods have given promising results, the effects of polyphenols and honey are still not being elucidated. Considering the polyphenol composition of honey, it can be more effective in treating various aspects of AD neuropathology compared to dopamine alone. On the same note, despite the fact that honey consumption is found to have a miraculous role in treating various diseases [263,264,265], its effectiveness in neurodegenerative diseases is still under evaluation. Having being proven to positively affect cognition and memory, the antioxidant capacity of honey also suggests its potential to manage neurological disorders and neurodegenerative diseases. More studies are needed to be conducted using animal models of neurodegenerative diseases, such as AD, to study the benefits of honey in its treatment and management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and M.F.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.; writing—review and editing, M.F.Y., F.A., J.K., and S.L.T.; supervision, M.F.Y., F.A., J.K. and S.L.T.; project administration, M.F.Y.; funding acquisition, M.F.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by UKM Research University Grant, grant number GUP-2021-038.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- da Silva Filho, S.R.B.; Barbosa, J.H.O.; Rondinoni, C.; dos Santos, A.C.; Salmon, C.E.G.; da Costa Lima, N.K.; Ferriolli, E.; Moriguti, J.C. Neuro-Degeneration Profile of Alzheimer’s Patients: A Brain Morphometry Study. NeuroImage Clin. 2017, 15, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein-Koerkamp, Y.; Rolf, A.H.; Kylee, T.R.; Moreaud, O.; Keignart, S.; Krainik, A.; Hammers, A.; Baciu, M.; Hot, P.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Amygdalar Atrophy in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2014, 11, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeTure, M.A.; Dickson, D.W. The Neuropathological Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2019, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Sidhu, J.; Goyal, A.; Tsao, J.W. Alzheimer Disease. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Dementia. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 16 November 2022).

- Mega, M.S.; Cummings, J.L.; Fiorello, T.; Gornbein, J. The Spectrum of Behavioral Changes in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 1996, 46, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisberg, B.; Doody, R.; Stöffler, A.; Schmitt, F.; Ferris, S.; Möbius, H.J. Memantine in Moderate-to-Severe Alzheimer’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1333–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.M.; Keating, G.M. Memantine. Drugs 2006, 66, 1515–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyjolfsdottir, H.; Eriksdotter, M.; Linderoth, B.; Lind, G.; Juliusson, B.; Kusk, P.; Almkvist, O.; Andreasen, N.; Blennow, K.; Ferreira, D.; et al. Targeted Delivery of Nerve Growth Factor to the Cholinergic Basal Forebrain of Alzheimer’s Disease Patients: Application of a Second-Generation Encapsulated Cell Biodelivery Device. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2016, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, J.S.; Harvey, R.J. Donepezil for Dementia Due to Alzheimer’s Disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2018, CD001190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M.E.; Stamford, A.W.; Chen, X.; Cox, K.; Cumming, J.N.; Dockendorf, M.F.; Egan, M.; Ereshefsky, L.; Hodgson, R.A.; Hyde, L.A.; et al. The BACE1 Inhibitor Verubecestat (MK-8931) Reduces CNS β-Amyloid in Animal Models and in Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 363ra150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, P.; Schmidt, R.; Kontsekova, E.; Zilka, N.; Kovacech, B.; Skrabana, R.; Vince-Kazmerova, Z.; Katina, S.; Fialova, L.; Prcina, M.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of the Tau Vaccine AADvac1 in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 1 Trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Tanaka, T.; Han, D.; Senzaki, K.; Kameyama, T.; Nabeshima, T. Protective Effects of Idebenone and α-Tocopherol on β-Amyloid-(1–42)-Induced Learning and Memory Deficits in Rats: Implication of Oxidative Stress in β-Amyloid-Induced Neurotoxicity in Vivo. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999, 11, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohkura, T.; Isse, K.; Akazawa, K.; Hamamoto, M.; Yaoi, Y.; Hagino, N. Evaluation of Estrogen Treatment in Female Patients with Dementia of the Alzheimer Type. Endocr. J. 1994, 41, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkura, T.; Isse, K.; Akazawa, K.; Hamamoto, M.; Yaoi, Y.; Hagino, N. Long-Term Estrogen Replacement Therapy in Female Patients with Dementia of the Alzheimer Type: 7 Case Reports. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 1995, 6, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baranowska-Wójcik, E.; Szwajgier, D.; Winiarska-Mieczan, A. Honey as the Potential Natural Source of Cholinesterase Inhibitors in Alzheimer’s Disease. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2020, 75, 30–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azman, K.F.; Zakaria, R. Honey as an Antioxidant Therapy to Reduce Cognitive Ageing. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2019, 22, 1368–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordin, A.; Saim, A.B.; Idrus, R.B.H. Honey Ameliorate Negative Effects in Neurodegenerative Diseases: An Evidence-Based Review. Sains Malays. 2021, 50, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuns, B.; Rosani, A.; Varghese, D. Memantine. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rossom, R.; Adityanjee; Dysken, M. Efficacy and Tolerability of Memantine in the Treatment of Dementia. Am. J. Geriatr. Pharmacother. 2004, 2, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, L.; Selkoe, D. Verubecestat for Prodromal Alzheimer’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 388–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, R.; Salloway, S.; Brooks, D.J.; Tampieri, D.; Barakos, J.; Fox, N.C.; Raskind, M.; Sabbagh, M.; Honig, L.S.; Porsteinsson, A.P.; et al. Amyloid-Related Imaging Abnormalities in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease Treated with Bapineuzumab: A Retrospective Analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2012, 11, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, N.; Llewellyn, D.; Isaac, M.G.E.K.N.; Tabet, N. Vitamin E for Alzheimer’s Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 4, CD002854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, S.; Szabó, A.; Hegyi, A.E.; Török, B.; Fazekas, C.L.; Ernszt, D.; Kovács, T.; Zelena, D. Estradiol and Estrogen-like Alternative Therapies in Use: The Importance of the Selective and Non-Classical Actions. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artero, A.; Tarín, J.J.; Cano, A. The Adverse Effects of Estrogen and Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators on Hemostasis and Thrombosis. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2012, 38, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, L.; Kohlich, A.; Hirschwehr, R.; Siemann, U.; Ebner, H.; Scheiner, O.; Kraft, D.; Ebner, C. Food Allergy to Honey: Pollen or Bee Products?: Characterization of Allergenic Proteins in Honey by Means of Immunoblotting. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1996, 97, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Costanzo, M.; De Paulis, N.; Peveri, S.; Montagni, M.; Canani, R.B.; Biasucci, G. Anaphylaxis Caused by Artisanal Honey in a Child: A Case Report. J. Med. Case Reports 2021, 15, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguiar, R.; Duarte, F.C.; Mendes, A.; Bartolomé, B.; Barbosa, M.P. Anaphylaxis Caused by Honey: A Case Report. Asia Pac. Allergy 2017, 7, 48–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Rahbi, B.; Zakaria, R.; Othman, Z.; Hassan, A.; Ahmad, A.H. Protective Effects of Tualang Honey against Oxidative Stress and Anxiety-Like Behaviour in Stressed Ovariectomized Rats. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2014, 2014, e521065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sairazi, N.S.M.; Sirajudeen, K.N.S.; Asari, M.A.; Mummedy, S.; Muzaimi, M.; Sulaiman, S.A. Effect of Tualang Honey against KA-Induced Oxidative Stress and Neurodegeneration in the Cortex of Rats. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafin, N.; Othman, Z.; Zakaria, R.; Hussain, N.H.N. Tualang Honey Supplementation Reduces Blood Oxidative Stress Levels/Activities in Postmenopausal Women. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2014, 2014, e364836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candiracci, M.; Piatti, E.; Dominguez-Barragán, M.; García-Antrás, D.; Morgado, B.; Ruano, D.; Gutiérrez, J.F.; Parrado, J.; Castaño, A. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of a Honey Flavonoid Extract on Lipopolysaccharide-Activated N13 Microglial Cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 12304–12311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sairazi, N.S.M.; Sirajudeen, K.N.S.; Muzaimi, M.; Mummedy, S.; Asari, M.A.; Sulaiman, S.A. Tualang Honey Reduced Neuroinflammation and Caspase-3 Activity in Rat Brain after Kainic Acid-Induced Status Epilepticus. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2018, 2018, e7287820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, N.A.; Lin, T.S.; Yahaya, M.F. Stingless Bee Honey Reduces Anxiety and Improves Memory of the Metabolic Disease-Induced Rats. CNS Neurol. Disord.-Drug Targets-CNS Neurol. Disord. 2020, 19, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, A.K.; Phyu, H.P.; Al-Ani, I.M.; Talib, N.A. Potential Protective Effect of Honey against Chronic Cerebral Hypoperfusion-Induced Neurodegeneration in Rats. J. Anat. Soc. India 2014, 63, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, H.; Ouchemoukh, S.; Amessis-Ouchemoukh, N.; Debbache, N.; Pacheco, R.; Serralheiro, M.L.; Araujo, M.E. Biological Properties of Phenolic Compound Extracts in Selected Algerian Honeys—The Inhibition of Acetylcholinesterase and α-Glucosidase Activities. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2019, 25, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Himyari, F.A. P1-241: The Use of Honey as a Natural Preventive Therapy of Cognitive Decline and Dementia in the Middle East. Alzheimers Dement. 2009, 5, P247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafin, N.; Zakaria, R.; Othman, Z.; Nik, N.H. Improved Blood Oxidative Status Is Not Associated with Better Memory Performance in Postmenopausal Women Receiving Tualang Honey Supplementation. J. Biochem. Pharmacol. Res. 2014, 2, 110–116. [Google Scholar]

- Behl, C. Alzheimer’s Disease and Oxidative Stress: Implications for Novel Therapeutic Approaches. Prog. Neurobiol. 1999, 57, 301–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schönheit, B.; Zarski, R.; Ohm, T.G. Spatial and Temporal Relationships between Plaques and Tangles in Alzheimer-Pathology. Neurobiol. Aging 2004, 25, 697–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vossel, K.A.; Zhang, K.; Brodbeck, J.; Daub, A.C.; Sharma, P.; Finkbeiner, S.; Cui, B.; Mucke, L. Tau Reduction Prevents Aβ-Induced Defects in Axonal Transport. Science 2010, 330, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braak, H.; Del Tredici, K. Evolutional Aspects of Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2013, 33, S155–S161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellmerich, S.; Taylor, G.W.; Richardson, C.D.; Minett, T.; Schmidt, A.F.; Brayne, C.; Matthews, F.E.; Ince, P.G.; Wharton, S.B.; Pepys, M.B.; et al. Dementia in the Older Population Is Associated with Neocortex Content of Serum Amyloid P Component. Brain Commun. 2021, 3, fcab225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J.R.; Bjorklund, N.L.; Taglialatela, G.; Gomer, R.H. Brain Serum Amyloid P Levels Are Reduced in Individuals That Lack Dementia While Having Alzheimer’s Disease Neuropathology. Neurochem. Res. 2012, 37, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kuchibhotla, K.V.; Wegmann, S.; Kopeikina, K.J.; Hawkes, J.; Rudinskiy, N.; Andermann, M.L.; Spires-Jones, T.L.; Bacskai, B.J.; Hyman, B.T. Neurofibrillary Tangle-Bearing Neurons Are Functionally Integrated in Cortical Circuits in Vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haroutunian, V.; Schnaider-Beeri, M.; Schmeidler, J.; Wysocki, M.; Purohit, D.P.; Perl, D.P.; Libow, L.S.; Lesser, G.T.; Maroukian, M.; Grossman, H.T. Role of the Neuropathology of Alzheimer Disease in Dementia in the Oldest-Old. Arch. Neurol. 2008, 65, 1211–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Braunstein, K.E.; Zhang, J.; Lau, A.; Sibener, L.; Deeble, C.; Wong, P.C. The Neuritic Plaque Facilitates Pathological Conversion of Tau in an Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Model. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, U.A.; Liu, L.; Provenzano, F.A.; Berman, D.E.; Profaci, C.P.; Sloan, R.; Mayeux, R.; Duff, K.E.; Small, S.A. Molecular Drivers and Cortical Spread of Lateral Entorhinal Cortex Dysfunction in Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2014, 17, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P.T.; Abner, E.L.; Schmitt, F.A.; Kryscio, R.J.; Jicha, G.A.; Santacruz, K.; Smith, C.D.; Patel, E.; Markesbery, W.R. Brains With Medial Temporal Lobe Neurofibrillary Tangles But No Neuritic Amyloid Plaques Are a Diagnostic Dilemma But May Have Pathogenetic Aspects Distinct From Alzheimer Disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2009, 68, 774–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.-Z.; Liu, R.; Wang, X. Tau Ubiquitination in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 2022, 12, 786353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martín, T.; Cuchillo-Ibáñez, I.; Noble, W.; Nyenya, F.; Anderton, B.H.; Hanger, D.P. Tau Phosphorylation Affects Its Axonal Transport and Degradation. Neurobiol. Aging 2013, 34, 2146–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshiyama, Y.; Higuchi, M.; Zhang, B.; Huang, S.-M.; Iwata, N.; Saido, T.C.; Maeda, J.; Suhara, T.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Lee, V.M.-Y. Synapse Loss and Microglial Activation Precede Tangles in a P301S Tauopathy Mouse Model. Neuron 2007, 53, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaud, L.; Robakis, N.K.; Figueiredo-Pereira, M.E. It May Take Inflammation, Phosphorylation and Ubiquitination to ‘Tangle’ in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurodegener. Dis. 2006, 3, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennol, M.P.; Sánchez-Domínguez, I.; Cuchillo-Ibañez, I.; Camporesi, E.; Brinkmalm, G.; Alcolea, D.; Fortea, J.; Lleó, A.; Soria, G.; Aguado, F.; et al. Apolipoprotein E Imbalance in the Cerebrospinal Fluid of Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2022, 14, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corder, E.H.; Saunders, A.M.; Strittmatter, W.J.; Schmechel, D.E.; Gaskell, P.C.; Small, G.W.; Roses, A.D.; Haines, J.L.; Pericak-Vance, M.A. Gene Dose of Apolipoprotein E Type 4 Allele and the Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease in Late Onset Families. Science 1993, 261, 921–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, A.M.; Strittmatter, W.J.; Schmechel, D.; George-Hyslop, P.H.S.; Pericak-Vance, M.A.; Joo, S.H.; Rosi, B.L.; Gusella, J.F.; Crapper-MacLachlan, D.R.; Alberts, M.J.; et al. Association of Apolipoprotein E Allele Ε4 with Late-onset Familial and Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 1993, 43, 1467–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, M.; Smith, J.D. Apolipoprotein E Allele–Specific Antioxidant Activity and Effects on Cytotoxicity by Oxidative Insults and β–Amyloid Peptides. Nat. Genet. 1996, 14, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, D.A.; Mattson, M.P. Apolipoprotein E and Oxidative Stress in Brain with Relevance to Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 138, 104795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gralle, M.; Ferreira, S.T. Structure and Functions of the Human Amyloid Precursor Protein: The Whole Is More than the Sum of Its Parts. Prog. Neurobiol. 2007, 82, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovelet-Lecrux, A.; Hannequin, D.; Raux, G.; Meur, N.L.; Laquerrière, A.; Vital, A.; Dumanchin, C.; Feuillette, S.; Brice, A.; Vercelletto, M.; et al. APP Locus Duplication Causes Autosomal Dominant Early-Onset Alzheimer Disease with Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 24–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleegers, K.; Brouwers, N.; Gijselinck, I.; Theuns, J.; Goossens, D.; Wauters, J.; Del-Favero, J.; Cruts, M.; van Duijn, C.M.; Broeckhoven, C.V. APP Duplication Is Sufficient to Cause Early Onset Alzheimer’s Dementia with Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy. Brain 2006, 129, 2977–2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, F.K.; Al-Janabi, T.; Hardy, J.; Karmiloff-Smith, A.; Nizetic, D.; Tybulewicz, V.L.J.; Fisher, E.M.C.; Strydom, A. A Genetic Cause of Alzheimer Disease: Mechanistic Insights from Down Syndrome. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Fu, Y.; Yasvoina, M.; Shao, P.; Hitt, B.; O’Connor, T.; Logan, S.; Maus, E.; Citron, M.; Berry, R.; et al. β-Site Amyloid Precursor Protein Cleaving Enzyme 1 Levels Become Elevated in Neurons around Amyloid Plaques: Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 3639–3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; An, S.S.A.; Kim, S. Mutations in Presenilin 2 and Its Implications in Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementia-Associated Disorders. Clin. Interv. Aging 2015, 10, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, H.; Hardy, J.; Blennow, K.; Chen, C.; Perry, G.; Kim, S.H.; Villemagne, V.L.; Aisen, P.; Vendruscolo, M.; Iwatsubo, T.; et al. The Amyloid-β Pathway in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 5481–5503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Jing, T.; Wang, X.; Yao, D. Beta-Secretase/BACE1 Promotes APP Endocytosis and Processing in the Endosomes and on Cell Membrane. Neurosci. Lett. 2018, 685, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, G.; Gerber, H.; Koch, P.; Bruestle, O.; Fraering, P.C.; Rajendran, L. The Alzheimer’s Disease γ-Secretase Generates Higher 42:40 Ratios for β-Amyloid Than for P3 Peptides. Cell Rep. 2017, 19, 1967–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, S.J.; Dawbarn, D.; Wilcock, G.K.; Allen, S.J. α- and β-Secretase: Profound Changes in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 299, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scahill, R.I.; Schott, J.M.; Stevens, J.M.; Rossor, M.N.; Fox, N.C. Mapping the Evolution of Regional Atrophy in Alzheimer’s Disease: Unbiased Analysis of Fluid-Registered Serial MRI. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 4703–4707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetelat, G.A.; Baron, J.-C. Early Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Contribution of Structural Neuroimaging. NeuroImage 2003, 18, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheff, S.W.; Price, D.A.; Schmitt, F.A.; Mufson, E.J. Hippocampal Synaptic Loss in Early Alzheimer’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment. Neurobiol. Aging 2006, 27, 1372–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, K.F.S.; Ducatenzeiler, A.; Ribeiro-da-Silva, A.; Duff, K.; Bennett, D.A.; Cuello, A.C. The Amyloid Pathology Progresses in a Neurotransmitter-Specific Manner. Neurobiol. Aging 2006, 27, 1644–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R., Jr.; Lowe, V.J.; Weigand, S.D.; Wiste, H.J.; Senjem, M.L.; Knopman, D.S.; Shiung, M.M.; Gunter, J.L.; Boeve, B.F.; Kemp, B.J.; et al. Serial PIB and MRI in Normal, Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease: Implications for Sequence of Pathological Events in Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain 2009, 132, 1355–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzjohn, S.M.; Morton, R.A.; Kuenzi, F.; Rosahl, T.W.; Shearman, M.; Lewis, H.; Smith, D.; Reynolds, D.S.; Davies, C.H.; Collingridge, G.L.; et al. Age-Related Impairment of Synaptic Transmission But Normal Long-Term Potentiation in Transgenic Mice That Overexpress the Human APP695SWE Mutant Form of Amyloid Precursor Protein. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 4691–4698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen, J.S.; Wu, C.-C.; Redwine, J.M.; Comery, T.A.; Arias, R.; Bowlby, M.; Martone, R.; Morrison, J.H.; Pangalos, M.N.; Reinhart, P.H.; et al. Early-Onset Behavioral and Synaptic Deficits in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 5161–5166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoh, A.; Akaike, T.; Sokabe, M.; Nitta, A.; Iida, R.; Olariu, A.; Yamada, K.; Nabeshima, T. Impairments of Long-Term Potentiation in Hippocampal Slices of β-Amyloid-Infused Rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999, 382, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.H.; An, K.; Kwon, O.B.; Kim, H.; Kim, J.-H. Pathway-Specific Alteration of Synaptic Plasticity in Tg2576 Mice. Mol. Cells 2011, 32, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witton, J.; Brown, J.T.; Jones, M.W.; Randall, A.D. Altered Synaptic Plasticity in the Mossy Fibre Pathway of Transgenic Mice Expressing Mutant Amyloid Precursor Protein. Mol. Brain 2010, 3, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, M.A.; Scheff, S.W. Oxidative Stress in the Progression of Alzheimer Disease in the Frontal Cortex. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2010, 69, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, D.A.; Reed, T.T.; Perluigi, M.; De Marco, C.; Coccia, R.; Keller, J.N.; Markesbery, W.R.; Sultana, R. Elevated Levels of 3-Nitrotyrosine in Brain from Subjects with Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment: Implications for the Role of Nitration in the Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Res. 2007, 1148, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley-Whitman, M.A.; Lovell, M.A. Biomarkers of Lipid Peroxidation in Alzheimer Disease (AD): An Update. Arch. Toxicol. 2015, 89, 1035–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinney, J.W.; Bemiller, S.M.; Murtishaw, A.S.; Leisgang, A.M.; Salazar, A.M.; Lamb, B.T. Inflammation as a Central Mechanism in Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2018, 4, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyra e Silva, N.M.; Gonçalves, R.A.; Pascoal, T.A.; Lima-Filho, R.A.S.; de Paula França Resende, E.; Vieira, E.L.M.; Teixeira, A.L.; de Souza, L.C.; Peny, J.A.; Fortuna, J.T.S.; et al. Pro-Inflammatory Interleukin-6 Signaling Links Cognitive Impairments and Peripheral Metabolic Alterations in Alzheimer’s Disease. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Reyes, R.E.; Nava-Mesa, M.O.; Vargas-Sánchez, K.; Ariza-Salamanca, D.; Mora-Muñoz, L. Involvement of Astrocytes in Alzheimer’s Disease from a Neuroinflammatory and Oxidative Stress Perspective. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017, 10, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granic, I.; Dolga, A.M.; Nijholt, I.M.; van Dijk, G.; Eisel, U.L.M. Inflammation and NF-ΚB in Alzheimer’s Disease and Diabetes. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2009, 16, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyango, I.G.; Jauregui, G.V.; Čarná, M.; Bennett, J.P.; Stokin, G.B. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Bai, F.; Zhang, Z. Inflammatory Cytokines and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review from the Perspective of Genetic Polymorphisms. Neurosci. Bull. 2016, 32, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadani, S.P.; Cronk, J.C.; Norris, G.T.; Kipnis, J. IL-4 in the Brain: A Cytokine To Remember. J. Immunol. 2012, 189, 4213–4219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wu, P.; Siegel, M.I.; Egan, R.W.; Billah, M.M. Interleukin (IL)-10 Inhibits Nuclear Factor KB (NFĸB) Activation in Human Monocytes: IL-10 AND IL-4 SUPPRESS CYTOKINE SYNTHESIS BY DIFFERENT MECHANISMS (∗). J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 9558–9563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedberg, J.S.; Aytan, N.; Cherry, J.D.; Xia, W.; Standring, O.J.; Alvarez, V.E.; Nicks, R.; Svirsky, S.; Meng, G.; Jun, G.; et al. Associations between Brain Inflammatory Profiles and Human Neuropathology Are Altered Based on Apolipoprotein E Ε4 Genotype. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, L.M.; Ghura, S.; Koster, K.P.; Liakaite, V.; Maienschein-Cline, M.; Kanabar, P.; Collins, N.; Ben-Aissa, M.; Lei, A.Z.; Bahroos, N.; et al. APOE-Modulated Aβ-Induced Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s Disease: Current Landscape, Novel Data, and Future Perspective. J. Neurochem. 2015, 133, 465–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, F.; Feyen, L.; Freymann, K.; Tepest, R.; Maier, W.; Heun, R.; Schild, H.-H.; Scheef, L. Volume Reduction of the Entorhinal Cortex in Subjective Memory Impairment. Neurobiol. Aging 2006, 27, 1751–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajibola, A.; Chamunorwa, J.P.; Erlwanger, K.H. Nutraceutical Values of Natural Honey and Its Contribution to Human Health and Wealth. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreider, R.B.; Rasmussen, C.J.; Lancaster, S.L.; Kerksick, C.; Greenwood, M. Honey: An Alternative Sports Gel. Strength Cond. J. 2002, 24, 50–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Buelga, C.; González-Paramás, A.M. Chemical Composition of Honey. In Bee Products—Chemical and Biological Properties; Alvarez-Suarez, J.M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 43–82. ISBN 978-3-319-59689-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanov, S.; Jurendic, T.; Sieber, R.; Gallmann, P. Honey for Nutrition and Health: A Review. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2008, 27, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olas, B. Honey and Its Phenolic Compounds as an Effective Natural Medicine for Cardiovascular Diseases in Humans? Nutrients 2020, 12, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Y.; Meenu, M.; Yu, X.; Xu, B. Phenolic Acids and Flavonoids Profiles of Commercial Honey from Different Floral Sources and Geographic Sources. Int. J. Food Prop. 2019, 22, 290–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.M.; de Souza, E.L.; Marques, G.; Meireles, B.; de Magalhães Cordeiro, Â.T.; Gullón, B.; Pintado, M.M.; Magnani, M. Polyphenolic Profile and Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities of Monofloral Honeys Produced by Meliponini in the Brazilian Semiarid Region. Food Res. Int. 2016, 84, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranneh, Y.; Ali, F.; Zarei, M.; Akim, A.M.; Hamid, H.A.; Khazaai, H. Malaysian Stingless Bee and Tualang Honeys: A Comparative Characterization of Total Antioxidant Capacity and Phenolic Profile Using Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. LWT 2018, 89, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kek, S.P.; Chin, N.L.; Yusof, Y.A.; Tan, S.W.; Chua, L.S. Total Phenolic Contents and Colour Intensity of Malaysian Honeys from the Apis Spp. and Trigona Spp. Bees. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2014, 2, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniruzzaman, M.; Khalil, M.I.; Sulaiman, S.A.; Gan, S.H. Physicochemical and Antioxidant Properties of Malaysian Honeys Produced by Apis Cerana, Apis Dorsata and Apis Mellifera. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishore, R.K.; Halim, A.S.; Syazana, M.S.N.; Sirajudeen, K.N.S. Tualang Honey Has Higher Phenolic Content and Greater Radical Scavenging Activity Compared with Other Honey Sources. Nutr. Res. 2011, 31, 322–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putteeraj, M.; Lim, W.L.; Teoh, S.L.; Yahaya, M.F. Flavonoids and Its Neuroprotective Effects on Brain Ischemia and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Curr. Drug Targets 2018, 19, 1710–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Kamal, D.A.; Ibrahim, S.F.; Kamal, H.; Kashim, M.I.A.M.; Mokhtar, M.H. Physicochemical and Medicinal Properties of Tualang, Gelam and Kelulut Honeys: A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, R.A. Neuroinflammatory Processes Are Important in Neurodegenerative Diseases: An Hypothesis to Explain the Increased Formation of Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species as Major Factors Involved in Neurodegenerative Disease Development. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1346–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, V.; Bates, T.E.; Stella, A.M.G. NO Synthase and NO-Dependent Signal Pathways in Brain Aging and Neurodegenerative Disorders: The Role of Oxidant/Antioxidant Balance. Neurochem. Res. 2000, 25, 1315–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, R.; Januszewski, S.; Czuczwar, S.J. Myricetin as a Promising Molecule for the Treatment of Post-Ischemic Brain Neurodegeneration. Nutrients 2021, 13, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, M.; Darbandi, N.; Khodagholi, F.; Hashemi, A. Myricetin Protects Hippocampal CA3 Pyramidal Neurons and Improves Learning and Memory Impairments in Rats with Alzheimer’s Disease. Neural Regen. Res. 2016, 11, 1976–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhong, Y.; Gao, C.; Li, J. Myricetin Ameliorates Scopolamine-Induced Memory Impairment in Mice via Inhibiting Acetylcholinesterase and down-Regulating Brain Iron. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 490, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimmyo, Y.; Kihara, T.; Akaike, A.; Niidome, T.; Sugimoto, H. Multifunction of Myricetin on Aβ: Neuroprotection via a Conformational Change of Aβ and Reduction of Aβ via the Interference of Secretases. J. Neurosci. Res. 2008, 86, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Cheng, H.; Che, Z. Ameliorating Effect of Luteolin on Memory Impairment in an Alzheimer’s Disease Model. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 4215–4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Zhang, J.; Guo, L.; Xu, Y.; Sun, L.; Wang, S.; Feng, Y.; Gou, L.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y. Protective Role of Luteolin against Cognitive Dysfunction Induced by Chronic Cerebral Hypoperfusion in Rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2014, 126, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Dilger, R.N.; Johnson, R.W. Luteolin Inhibits Microglia and Alters Hippocampal-Dependent Spatial Working Memory in Aged Mice. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 1892–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Liu, L.; Wang, Q.; Gao, Y. Naringenin Alleviates Cognition Deficits in High-Fat Diet-Fed SAMP8 Mice. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.; Liaquat, L.; Ahmad, S.; Batool, Z.; Siddiqui, R.A.; Tabassum, S.; Shahzad, S.; Rafiq, S.; Naz, N. Naringenin Protects AlCl3/D-Galactose Induced Neurotoxicity in Rat Model of AD via Attenuation of Acetylcholinesterase Levels and Inhibition of Oxidative Stress. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0227631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghofrani, S.; Joghataei, M.-T.; Mohseni, S.; Baluchnejadmojarad, T.; Bagheri, M.; Khamse, S.; Roghani, M. Naringenin Improves Learning and Memory in an Alzheimer’s Disease Rat Model: Insights into the Underlying Mechanisms. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 764, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.B.; Khan, M.M.; Khan, A.; Ahmed, E.; Ishrat, T.; Tabassum, R.; Vaibhav, K.; Ahmad, A.; Islam, F. Naringenin Ameliorates Alzheimer’s Disease (AD)-Type Neurodegeneration with Cognitive Impairment (AD-TNDCI) Caused by the Intracerebroventricular-Streptozotocin in Rat Model. Neurochem. Int. 2012, 61, 1081–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Fu, M.; Wang, S.; Chen, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, N. Naringin Ameliorates Memory Deficits and Exerts Neuroprotective Effects in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease by Regulating Multiple Metabolic Pathways. Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 23, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongjaroenbuangam, W.; Ruksee, N.; Chantiratikul, P.; Pakdeenarong, N.; Kongbuntad, W.; Govitrapong, P. Neuroprotective Effects of Quercetin, Rutin and Okra (Abelmoschus Esculentus Linn.) in Dexamethasone-Treated Mice. Neurochem. Int. 2011, 59, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafpour, M.; Parsaei, S.; Sepehri, H. Quercetin Improved Spatial Memory Dysfunctions in Rat Model of Intracerebroventricular Streptozotocin-Induced Sporadic Alzheimer’sdisease. Natl. J. Physiol. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2015, 5, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabogal-Guáqueta, A.M.; Muñoz-Manco, J.I.; Ramírez-Pineda, J.R.; Lamprea-Rodriguez, M.; Osorio, E.; Cardona-Gómez, G.P. The Flavonoid Quercetin Ameliorates Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology and Protects Cognitive and Emotional Function in Aged Triple Transgenic Alzheimer’s Disease Model Mice. Neuropharmacology 2015, 93, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tota, S.; Awasthi, H.; Kamat, P.K.; Nath, C.; Hanif, K. Protective Effect of Quercetin against Intracerebral Streptozotocin Induced Reduction in Cerebral Blood Flow and Impairment of Memory in Mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2010, 209, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G.N.; Kim, J.H.; Kwak, J.H.; Jeong, C.-H.; Jeong, H.R.; Lee, U.; Heo, H.J. Effect of Quercetin on Learning and Memory Performance in ICR Mice under Neurotoxic Trimethyltin Exposure. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.-M.; Li, S.-Q.; Wu, W.-L.; Zhu, X.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, H.-Y. Effects of Long-Term Treatment with Quercetin on Cognition and Mitochondrial Function in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurochem. Res. 2014, 39, 1533–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beg, T.; Jyoti, S.; Naz, F.; Rahul; Ali, F.; Ali, S.K.; Reyad, A.M.; Siddique, Y.H. Protective Effect of Kaempferol on the Transgenic Drosophila Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. CNS Neurol. Disord.-Drug Targets-CNS Neurol. Disord. 2018, 17, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouhestani, S.; Jafari, A.; Babaei, P. Kaempferol Attenuates Cognitive Deficit via Regulating Oxidative Stress and Neuroinflammation in an Ovariectomized Rat Model of Sporadic Dementia. Neural Regen. Res. 2018, 13, 1827–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babaei, P.; Eyvani, K.; Kouhestani, S. Sex-Independent Cognition Improvement in Response to Kaempferol in the Model of Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurochem. Res. 2021, 46, 1480–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, R.; Kaundal, M.; Bansal, V. Samardeep Caffeic Acid Attenuates Oxidative Stress, Learning and Memory Deficit in Intra-Cerebroventricular Streptozotocin Induced Experimental Dementia in Rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 81, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, K.A.; Kumar, N.; Nayak, P.G.; Nampoothiri, M.; Shenoy, R.R.; Krishnadas, N.; Rao, C.M.; Mudgal, J. Impact of Caffeic Acid on Aluminium Chloride-Induced Dementia in Rats. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2013, 65, 1745–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Huang, D.; Lo, Y.M.; Tee, Q.; Kuo, P.; Wu, J.S.; Huang, W.; Shen, S. Protective Effect of Caffeic Acid against Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis via Modulating Cerebral Insulin Signaling, β-Amyloid Accumulation, and Synaptic Plasticity in Hyperinsulinemic Rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 7684–7693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadar, N.N.M.A.; Ahmad, F.; Teoh, S.L.; Yahaya, M.F. Comparable Benefits of Stingless Bee Honey and Caffeic Acid in Mitigating the Negative Effects of Metabolic Syndrome on the Brain. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Hua, L.; Han, B.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Bai, H.; Yin, H.; et al. Effects of Caffeic Acid on Learning Deficits in a Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2016, 38, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oboh, G.; Agunloye, O.M.; Akinyemi, A.J.; Ademiluyi, A.O.; Adefegha, S.A. Comparative Study on the Inhibitory Effect of Caffeic and Chlorogenic Acids on Key Enzymes Linked to Alzheimer’s Disease and Some Pro-Oxidant Induced Oxidative Stress in Rats’ Brain-In Vitro. Neurochem. Res. 2013, 38, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenno, R.; Dornlakorn, O.; Anosri, T.; Kaewngam, S.; Sirichoat, A.; Aranarochana, A.; Pannangrong, W.; Wigmore, P.; Welbat, J.U. Caffeic Acid Alleviates Memory and Hippocampal Neurogenesis Deficits in Aging Rats Induced by D-Galactose. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Li, X.; Meng, S.; Ma, T.; Wan, L.; Xu, S. Chlorogenic Acid Alleviates Aβ25-35-Induced Autophagy and Cognitive Impairment via the MTOR/TFEB Signaling Pathway. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2020, 14, 1705–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, W.; Qi, R.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Hu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Bie, M.; Wang, Y.; Fu, Y.; et al. Chlorogenic Acid Inhibits LPS-Induced Microglial Activation and Improves Survival of Dopaminergic Neurons. Brain Res. Bull. 2012, 88, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, S.-H.; Lee, H.-K.; Kim, J.-A.; Hong, S.-I.; Kim, H.-C.; Jo, T.-H.; Park, Y.-I.; Lee, C.-K.; Kim, Y.-B.; Lee, S.-Y.; et al. Neuroprotective Effects of Chlorogenic Acid on Scopolamine-Induced Amnesia via Anti-Acetylcholinesterase and Anti-Oxidative Activities in Mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 649, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiasalari, Z.; Heydarifard, R.; Khalili, M.; Afshin-Majd, S.; Baluchnejadmojarad, T.; Zahedi, E.; Sanaierad, A.; Roghani, M. Ellagic Acid Ameliorates Learning and Memory Deficits in a Rat Model of Alzheimer’s Disease: An Exploration of Underlying Mechanisms. Psychopharmacology 2017, 234, 1841–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harakeh, S.; Qari, M.H.; Ramadan, W.S.; Al Jaouni, S.K.; Almuhayawi, M.S.; Al Amri, T.; Ashraf, G.M.; Bharali, D.J.; Mousa, S.A. A Novel Nanoformulation of Ellagic Acid Is Promising in Restoring Oxidative Homeostasis in Rat Brains with Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Drug Metab. 2021, 22, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Jiang, B.; Fei, H.; Sun, Z. Ellagic Acid Ameliorates Learning and Memory Impairment in APP/PS1 Transgenic Mice via Inhibition of Β-amyloid Production and Tau Hyperphosphorylation. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 16, 4951–4958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, T.; Koyama, N.; Yokoo, T.; Segawa, T.; Maeda, M.; Sawmiller, D.; Tan, J.; Town, T. Gallic Acid Is a Dual α/β-Secretase Modulator That Reverses Cognitive Impairment and Remediates Pathology in Alzheimer Mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 16251–16266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, W.S.; Alkarim, S. Ellagic Acid Modulates the Amyloid Precursor Protein Gene via Superoxide Dismutase Regulation in the Entorhinal Cortex in an Experimental Alzheimer’s Model. Cells 2021, 10, 3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.B.; Panchal, S.S.; Shah, A. Ellagic Acid: Insights into Its Neuroprotective and Cognitive Enhancement Effects in Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2018, 175, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.-Y.; Li, J.-N.; Liu, W.-L.; Huang, Q.; Li, W.-X.; Tan, Y.-H.; Liu, F.; Song, Z.-H.; Wang, M.-Y.; Xie, N.; et al. Ferulic Acid Ameliorates Alzheimer’s Disease-like Pathology and Repairs Cognitive Decline by Preventing Capillary Hypofunction in APP/PS1 Mice. Neurotherapeutics 2021, 18, 1064–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, T.; Koyama, N.; Tan, J.; Segawa, T.; Maeda, M.; Town, T. Combined Treatment with the Phenolics (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate and Ferulic Acid Improves Cognition and Reduces Alzheimer-like Pathology in Mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 2714–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.-J.; Jung, J.-S.; Kim, T.-K.; Hasan, M.A.; Hong, C.-W.; Nam, J.-S.; Song, D.-K. Protective Effects of Ferulic Acid in Amyloid Precursor Protein Plus Presenilin-1 Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer Disease. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2013, 36, 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, T.; Koyama, N.; Guillot-Sestier, M.-V.; Tan, J.; Town, T. Ferulic Acid Is a Nutraceutical β-Secretase Modulator That Improves Behavioral Impairment and Alzheimer-like Pathology in Transgenic Mice. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.-Y.; Kim, H.-S.; Kim, D.-H.; Yan, J.-J.; Lee, H.-K.; Suh, H.-W.; Song, D.-K. Inhibitory Effects of Long-Term Administration of Ferulic Acid on Astrocyte Activation Induced by Intracerebroventricular Injection of β-Amyloid Peptide (1–42) in Mice. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 29, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-S.; Cho, J.; Kim, D.-H.; Yan, J.-J.; Lee, H.-K.; Suh, H.-W.; Song, D.-K. Inhibitory Effects of Long-Term Administration of Ferulic Acid on Microglial Activation Induced by Intracerebroventricular Injection of β-Amyloid Peptide (1—42) in Mice. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2004, 27, 120–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.-J.; Seong, A.-R.; Yoo, J.-Y.; Jin, C.-H.; Lee, Y.-H.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, J.; Jun, W.J.; Yoon, H.-G. Gallic Acid, a Histone Acetyltransferase Inhibitor, Suppresses β-Amyloid Neurotoxicity by Inhibiting Microglial-Mediated Neuroinflammation. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2011, 55, 1798–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunlade, B.; Adelakun, S.A.; Agie, J.A. Nutritional Supplementation of Gallic Acid Ameliorates Alzheimer-Type Hippocampal Neurodegeneration and Cognitive Impairment Induced by Aluminum Chloride Exposure in Adult Wistar Rats. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 45, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunsuyi, O.B.; Oboh, G.; Oluokun, O.O.; Ademiluyi, A.O.; Ogunruku, O.O. Gallic Acid Protects against Neurochemical Alterations in Transgenic Drosophila Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Adv. Tradit. Med. 2020, 20, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajipour, S.; Sarkaki, A.; Farbood, Y.; Eidi, A.; Mortazavi, P.; Valizadeh, Z. Effect of Gallic Acid on Dementia Type of Alzheimer Disease in Rats: Electrophysiological and Histological Studies. Basic Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 7, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, M.T.; Naghizadeh, B.; Ghorbanzadeh, B.; Farbood, Y.; Sarkaki, A.; Bavarsad, K. Gallic Acid Prevents Memory Deficits and Oxidative Stress Induced by Intracerebroventricular Injection of Streptozotocin in Rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2013, 111, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashno, M.; Gholipour, P.; Salehi, I.; Komaki, A.; Rashidi, K.; Khoshnam, S.E.; Ghaderi, S. P-Coumaric Acid Mitigates Passive Avoidance Memory and Hippocampal Synaptic Plasticity Impairments in Aluminum Chloride-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease Rat Model. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 94, 105117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, S.; Gholipour, P.; Komaki, A.; Salehi, I.; Rashidi, K.; Khoshnam, S.E.; Rashno, M. P-Coumaric Acid Ameliorates Cognitive and Non-Cognitive Disturbances in a Rat Model of Alzheimer’s Disease: The Role of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 112, 109295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-B.; Lee, S.; Hwang, E.-S.; Maeng, S.; Park, J.-H. P-Coumaric Acid Enhances Long-Term Potentiation and Recovers Scopolamine-Induced Learning and Memory Impairments. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 492, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devi, S.; Kumar, V.; Singh, S.K.; Dubey, A.K.; Kim, J.-J. Flavonoids: Potential Candidates for the Treatment of Neurodegenerative Disorders. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosso, C.; Valentao, P.; Ferreres, F.; Andrade, P.B. The Use of Flavonoids in Central Nervous System Disorders. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013, 20, 4694–4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Godos, J.; Privitera, A.; Lanza, G.; Castellano, S.; Chillemi, A.; Bruni, O.; Ferri, R.; Caraci, F.; Grosso, G. Phenolic Acids and Prevention of Cognitive Decline: Polyphenols with a Neuroprotective Role in Cognitive Disorders and Alzheimer’s Disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freyssin, A.; Page, G.; Fauconneau, B.; Bilan, A.R. Natural Polyphenols Effects on Protein Aggregates in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Prion-like Diseases. Neural Regen. Res. 2018, 13, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.Y.D.; Dobrachinski, F.; Silva, H.B.; Lopes, J.P.; Gonçalves, F.Q.; Soares, F.A.A.; Porciúncula, L.O.; Andrade, G.M.; Cunha, R.A.; Tomé, A.R. Neuromodulation and Neuroprotective Effects of Chlorogenic Acids in Excitatory Synapses of Mouse Hippocampal Slices. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, T.; Ingelsson, M.; Fukumoto, H.; Ramasamy, K.; Kowa, H.; Frosch, M.P.; Irizarry, M.C.; Hyman, B.T. Expression of APP Pathway MRNAs and Proteins in Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Res. 2007, 1161, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezai-Zadeh, K.; Shytle, R.D.; Bai, Y.; Tian, J.; Hou, H.; Mori, T.; Zeng, J.; Obregon, D.; Town, T.; Tan, J. Flavonoid-Mediated Presenilin-1 Phosphorylation Reduces Alzheimer’s Disease β-Amyloid Production. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2009, 13, 574–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubos, E.; Loscalzo, J.; Handy, D.E. Glutathione Peroxidase-1 in Health and Disease: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Opportunities. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 15, 1957–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hole, K.L.; Williams, R.J. Flavonoids as an Intervention for Alzheimer’s Disease: Progress and Hurdles Towards Defining a Mechanism of Action. Brain Plast. 2020, 6, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Fan, Y.; Yan, E.; Liu, Z.; Zong, Z.; Qi, Z. Effects of Sodium Ferulate on Amyloid-Beta-Induced MKK3/MKK6-P38 MAPK-Hsp27 Signal Pathway and Apoptosis in Rat Hippocampus. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2006, 27, 1309–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Kelley, K.W.; Johnson, R.W. Luteolin Reduces IL-6 Production in Microglia by Inhibiting JNK Phosphorylation and Activation of AP-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 7534–7539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Kebede, M.T.; Kemeh, M.M.; Islam, S.; Lee, B.; Bleck, S.D.; Wurfl, L.A.; Lazo, N.D. Inhibition of the Self-Assembly of Aβ and of Tau by Polyphenols: Mechanistic Studies. Molecules 2019, 24, 2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamaguchi, T.; Ono, K.; Murase, A.; Yamada, M. Phenolic Compounds Prevent Alzheimer’s Pathology through Different Effects on the Amyloid-β Aggregation Pathway. Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 175, 2557–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochiai, R.; Saitou, K.; Suzukamo, C.; Osaki, N.; Asada, T. Effect of Chlorogenic Acids on Cognitive Function in Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized Controlled Crossover Trial. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2019, 72, 1209–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]