Abstract

Introduction: Anxiety is a common problem during pregnancy and postpartum that can have important consequences for mothers and their babies. Having preventive psychological interventions to apply during the perinatal stage could help to reduce its adverse effects. The aim of this study was to find out which psychological interventions have been applied for the prevention of perinatal anxiety, what therapeutic approach and application format have been most commonly used, and which interventions have proven to be most effective. Methods: A literature review was conducted in the PsycInfo, Medline, and SCOPUS databases to identify articles published between March 2015 and March 2025. Results: Twenty studies were selected that met the inclusion criteria. Twelve of the interventions analyzed were indicated prevention programs and eight were universal prevention programs, with most taking place in pregnancy (n = 18). Mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapy were the most commonly employed approaches. Regarding the application format, interventions conducted face-to-face and online were equally frequent, as well as those carried out individually or in groups. The duration ranged from 4 to 14 sessions. Cognitive behavioral therapy interventions, applied face-to-face and in groups, proved to be the most effective. Conclusions: Preventive psychological interventions are effective in reducing anxiety during pregnancy. Further research is needed to draw conclusive results on their long-term effects and efficacy in the postpartum period.

1. Introduction

The perinatal period represents a time when the risk of developing a mental health problem increases [1,2] or exacerbating a pre-existing condition [3]. An estimated 20% of women may develop a mental disorder during the perinatal stage, primarily anxiety and depression [4,5]. In recent years there has been a growing interest in exploring the prevalence and consequences of anxiety in the perinatal period (e.g., [6,7,8]), leading to the knowledge that anxiety is a common mental health problem during the perinatal stage [6]. The rates of anxiety disorders and symptoms during pregnancy are between 15.0% and 23.0%, and between 9.0% and 15.0% during postpartum [6,9,10].

Untreated perinatal anxiety leads to adverse consequences for both mothers and their children [11]. Regarding mothers, it has been associated with an increased likelihood of developing postpartum depression [12], an increased risk of preeclampsia, obstetric complications, and bonding problems [13,14]. As for newborns, it has been observed that they are more likely to have lower birth weight and poor cognitive development, among others [15,16,17]. These consequences can result in increased use of educational and healthcare resources [18], which translates into higher economic costs for society [19]. The above justifies the importance of early detection and intervention on anxiety to promote the well-being of mothers and children.

While there is increasing interest in maternal mental health, most research has focused on assessing and treating perinatal depression [8,20,21]. However, the literature on effective treatment and clinical management of perinatal anxiety through psychological interventions is limited [22]. An example of this is the absence of a review on the subject in the Cochrane Library, as opposed to the existence of a specific review on the prevention of postpartum depression [23]. It is important to keep in mind that in this period women prefer psychological interventions [24] and, in addition, a non-pharmacological approach should be adopted because of the potential risks of medication use during pregnancy, such as miscarriages, birth malformations or breastfeeding difficulties, among others [25,26,27].

When researching existing psychological interventions to address perinatal anxiety, it is important to clarify the difference between interventions aimed at prevention and those aimed at treatment. The latter refer to interventions aimed at reducing or eliminating a disease once it has begun, although ideally it would be possible to prevent its onset. Several approaches have shown promise for the treatment of perinatal anxiety, such as cognitive behavioral therapy [28], interpersonal therapy [8] or mindfulness-based therapies [29]. On the other hand, preventive interventions refer to actions aimed at avoiding the onset and consequences of a disease. In the context of perinatal anxiety, prevention could avoid possible adverse health consequences for women and their babies (e.g., increased likelihood of postpartum depression, obstetric complications, bonding problems, lower birth weight, poorer cognitive development). Prevention also has the potential to reduce health care costs [30] and barriers that prevent people from receiving treatment, such as the lack of mental health professionals [31] to meet the growing mental health care needs of this population. Thus, prioritizing prevention could reduce the burden on health systems.

Preventive interventions are classified according to their scope. Thus, universal prevention interventions target the entire population, whereas indicated prevention interventions focus on a high-risk population [32]. Both universal and indicated approaches have been effective in preventing mental health problems in perinatal populations. For example, interventions to prevent perinatal depression have been shown to be effective [33] and are recommended by the United States Preventive Services Task Forces (USPSTF) for women at risk for developing perinatal depression [34]. Most studies evaluating interventions to prevent perinatal depression have used an indicated prevention approach, including individuals at increased risk for depression as determined by elevated depressive symptoms or a history of depression [34]. In addition, due to the high comorbidity between anxiety and depression [7], some studies aimed at preventing perinatal depression have assessed perinatal anxiety as a secondary outcome [34]; however, it is unclear to what extent interventions developed to prevent depression may also prevent perinatal anxiety. In this regard, it should be noted that the decrease in anxiety levels may be due to an indirect effect by improving depressive symptoms, without having a direct effect on anxiety.

Therefore, it is necessary to dedicate resources to the prevention of perinatal anxiety, even more so knowing its high prevalence and the consequences it entails for mothers and children. Knowing what type of preventive interventions are most frequently applied, the aspects they address, and which are the most effective would allow the development and implementation of preventive psychological interventions to reduce the probability of suffering anxiety at this stage of life.

So far, there have been few efforts aimed at preventing perinatal anxiety. Moreover, previous reviews have looked at interventions aimed at addressing anxiety and depression together [35], included both therapeutic and preventive interventions [36], have focused exclusively on preventing anxiety disorders [37], have analyzed a particular time in the perinatal stage such as pregnancy [38], or have focused on a specific therapeutic approach [29,39]. Therefore, there is a lack of studies that have focused on learning about existing psychological interventions to prevent or reduce the occurrence of both elevated anxious symptomatology and an anxiety disorder throughout the perinatal period. This review fills a gap in knowledge on this topic, as it is the first to focus on identifying psychological interventions aimed at preventing perinatal anxiety.

Knowing what preventive psychological interventions exist, their therapeutic approach, their components, and their efficacy may contribute to the development of appropriate interventions to address perinatal anxiety. This would contribute to avoiding its possible consequences for both mothers and their children. To this end, a systematic review of the research published on this subject in the last 10 years was carried out.

Based on the aforementioned, the main objective of this review was to know which psychological interventions have been applied for the prevention of perinatal anxiety. The specific objectives were to analyze (1) the most commonly used therapeutic approach and format; and (2) the type of interventions that have proven to be most effective.

2. Methods

The study’s selection process was carried out following recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [40]. Articles had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) be published in a scientific journal; (2) be written in English, but conducted in any country; (3) apply a psychological intervention with the aim of preventing or reducing perinatal anxiety; (4) the intervention had to be implemented during pregnancy or in the postpartum period; (5) evaluate the effect of the intervention quantitatively; (6) participants could not meet diagnostic criteria for a generalized anxiety disorder; and (7) published between March 2015 and March 2025. Additionally, studies evaluating pregnancy-specific anxiety were excluded, since it is known that it is a different entity from the diagnostic and continuous measures of general anxiety, as it is a specific type of anxiety characterized by fears and/or concerns about pregnancy [41]; those that assessed anxiety in conjunction with other emotional symptomatology (e.g., comorbidity between anxiety and depression, stress); those focused on specific anxiety disorders (e.g., obsessive compulsive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder); studies including non-representative samples (e.g., twin pregnancies, families without resources); and other reviews.

No large-language models or AI tools were used in the preparation of this manuscript.

2.1. Search Strategy

A literature search was carried out in the PsycINFO, Medline, and SCOPUS databases to identify papers published between the specified period (31 March 2015 to 31 March 2025). The following keywords were used in the initial search by combining them as follows: “psychological intervention” OR “prevention” (abstract/title) AND “perinatal anxiety” OR “prenatal anxiety” OR “postnatal anxiety” (abstract/title). Reference lists of retrieved articles were also examined.

2.2. Strategy for the Selection of Studies and Analysis of Results

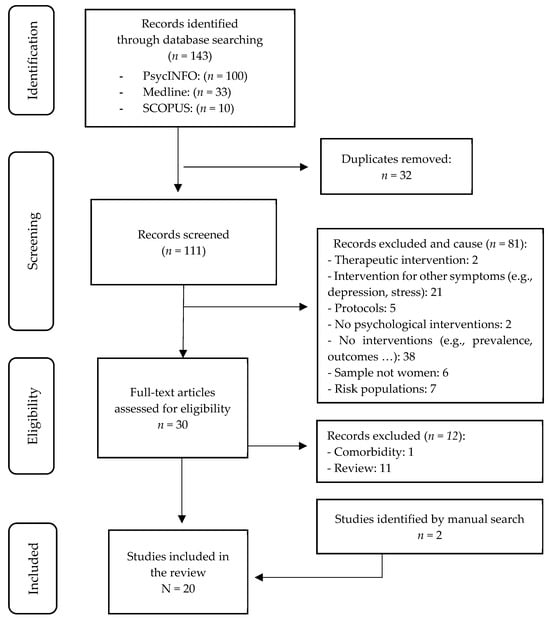

Article selection was performed independently by two investigators and, in case of discrepancies, discussed between them. When no agreement was reached, the third author decided whether the article should be included. First, all publications found within the search criteria were transferred to Refworks and all repeated publications were removed. Subsequently, the studies were selected by reading the titles and abstracts, and finally the full text. The complete selection process is summarized in Figure 1. The extracted data were synthesized by year, objective, sample, measures, results, and conclusions. Statistical data from the studies were evaluated.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

The search strategy designed resulted in a total of 143 potential scientific publications: PsycINFO (n = 100), Medline (n = 33), and SCOPUS (n = 10). Of these, 32 were duplicates (Table S1), so the final number of publications after eliminating duplicates was 111.

A systematic search was then carried out in which the retrieved studies were screened. A series of inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to guide the selection process. After reading the title and abstract of the studies, the investigators excluded a total of 81 studies for (1) being therapeutic interventions, i.e., for women who met the criteria for a mental disorder; (2) being interventions aimed at other symptomatology (e.g., depression, stress, distress); (3) being protocols; (4) not being psychological interventions; (5) addressing aspects other than an intervention (e.g., prevalence, consequences); (6) not being psychological interventions; (7) addressing aspects other than an intervention (e.g., prevalence, consequences); (8) not being psychological interventions; and (9) not addressing aspects other than an intervention (e.g., prevalence, consequences); (10) the sample was not women; and (11) they were at-risk populations (e.g., low-income women, battered women, etc.).

After selection, the full text of each of the 30 selected articles was analyzed and, finally, 18 studies were included. The other 12 were excluded because they addressed comorbidity between anxiety and depression (n = 1) or because they were systematic reviews (n = 11). Two other studies identified by a hand search were added. Thus, 20 articles were finally included in the review.

The quality of the selected studies was assessed using the Mixed Methods Assessment Tool (MMAT) [42] through two general screening questions and five specific questions, depending on the design of each study (in this case, quantitative randomized controlled trials and quantitative non-randomized studies). The researchers re-read the full text of each article, extracting the information of interest/relevance for the review. The selected results were then compiled in table format (Table S2). Based on the data provided by MMAT, it can be observed that, at a general level, the studies included in the review show a low risk of bias, allowing robust conclusions to be drawn in relation to psychological interventions to prevent perinatal anxiety.

3.2. Characteristics of Selected Studies

Twenty articles were reviewed that applied a psychological intervention to prevent or reduce anxiety during pregnancy or postpartum. Most of the interventions were applied in pregnancy (n = 18) and only two were applied in the postpartum. Australia and China were the countries with the most interventions (n = 5 each), followed by the Netherlands (n = 3) and Iran (n = 2). Romania, the USA, the UK, India, and Canada each contributed one study.

Regarding the type of design employed in each investigation, most were randomized controlled trials (n = 15), two were quasi-experimental studies, and three were pre-post designs. Great variability was observed in the sample size of each study ranging from 29 [43] to 529 women [44]. The total number of women included in the studies was 2889, being 2617 pregnant women and 272 postpartum women.

Several questionnaires were used to assess anxiety. Specifically, nine studies evaluated anxiety with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7), being the most commonly used instrument. Five studies used the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), two the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS) and the Perinatal Anxiety Screening Scale (PASS). The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM-A), the Anxiety Subscale of the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS-A), and the Anxiety Subscale of the EPDS (EDS-3A) were employed in one study each.

Regarding who delivered the interventions, all were applied and/or guided by mental health professionals (psychologists/psychiatrists) or other trained professionals (e.g., midwives, meditation teachers).

With regard to ethical aspects, all studies included in the review had a data protection protocol in place, which guaranteed the confidentiality of participants’ personal data. Furthermore, women were required to sign an informed consent form before participating in the study. Regarding online interventions, women were given a password to access the sessions in order to preserve their anonymity.

3.3. Characteristics of Interventions

3.3.1. Type of Prevention Program

Of the 20 interventions reviewed, eight were universal prevention interventions (Table 1) and 12 were indicated prevention interventions (Table 2). All universal prevention interventions [43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50] were delivered during pregnancy. Regarding indicated prevention, 10 interventions were conducted in pregnancy [51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60] and two [61,62] were applied in the postpartum.

Table 1.

Universal prevention interventions.

Table 2.

Indicated preventive interventions.

3.3.2. Therapeutic Approach and Application Format

In terms of the therapeutic approach applied, nine interventions employed mindfulness, eight employed cognitive behavioral therapy, one employed peer support therapy, one employed attentional bias training and one combined several therapeutic approaches (see Table 1 and Table 2).

Regarding the type of prevention applied, four of the universal interventions used cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), two used mindfulness, one used peer support therapy and one used attentional bias training. Regarding the indicated prevention interventions, seven interventions employed mindfulness or mindfulness-based CBT, four employed CBT, and one combined several therapeutic approaches.

Of the 18 interventions implemented in pregnancy, seven employed mindfulness-based interventions [49,50,55,56,57,58,59,60] and two employed cognitive behavioral therapy-based mindfulness [54,58]. CBT was employed in seven interventions [44,45,47,48,51,52,53]. It should be noted that Anton and David [45] applied Rational Emotive Therapy (RET) and Sharma et al. [48] progressive muscle relaxation. On the other hand, Fontein-Kupiers et al. [46] conducted a peer support program where strategies and support resources were provided to prevent maternal distress. Finally, in the study by Dennis-Tiwary et al. [43], an attentional bias training program (ABMT) was applied, which consisted of training attention away from threat, i.e., redirecting attention away from stimuli perceived as negative or threatening, with the aim of reducing attentional bias towards threat.

In postpartum, Appleton et al. [61] combined different therapeutic approaches (CBT, mindfulness and self-compassion) and Loughnan, Butler et al. [62] applied CBT via internet.

In terms of implementation format, five of the universal programs were carried out face-to-face and three were developed online. With respect to the indicated prevention programs, seven interventions were carried out online and five were face-to-face.

Of the 18 interventions implemented in pregnancy, nine were delivered face-to-face, of which five were mindfulness interventions [49,50,54,55,58] and four were CBT [45,47,48,51]. The remaining nine interventions [43,44,46,52,53,56,57,59,60] were conducted online, via platforms or apps. Regarding postpartum, one intervention was delivered face- to-face [61] and one online [62].

A large proportion of the interventions (n = 9) were conducted in a group format [45,49,50,51,54,55,58,61]. However, it should be noted that Anton and David [45] conducted the first individual session and Sharma et al. [48] do not specify the application format. The online interventions were conducted individually.

The number of sessions used ranged from 4 [47,48,49,53,56,57,60] to 10–14 sessions [51] in pregnancy, with a duration of four sessions being most common (n = 7). In postpartum, the recommended number of sessions to complete the online program was six [62] and the Appleton et al. [61] program consisted of eight sessions.

3.3.3. Effectiveness of Intervention

Of the 20 interventions analyzed (see Table 3), 12 [44,45,46,47,48,49,53,55,58,59,61,62] found significant reductions in anxiety levels in post-treatment assessments relative to those conducted at pre-treatment. Of these, six were universal prevention interventions [44,45,46,47,48,49] and six were indicated prevention [53,55,58,59,61,62].

Table 3.

Summary of the main characteristics of the selected studies.

Regarding the 18 interventions in pregnancy, 10 were effective in reducing anxiety. Of these, five were cognitive behavioral therapy interventions [44,45,47,48,53], four mindfulness [49,55,58,59], and another a peer support program [46]. Most (n = 6) were delivered face-to-face [45,47,49,55,58] versus online format [44,46,53,59]. Six interventions were conducted in groups [45,47,49,55,58,61] and four were developed individually [44,46,53,59]. In terms of the number of sessions of the interventions that were effective, four were comprised of four sessions [47,48,49,53], three had eight sessions [45,55,58], in one the number of sessions ranged from four to six [44], and one did not specify the number of sessions [46].

Regarding postpartum, the two interventions found that both CBT applied online [62] and psychotherapy developed face-to-face [61] proved to be effective in reducing anxiety levels. The number of sessions ranged from six to eight.

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications of the Study

One of the objectives of this review was to find out what type of psychological interventions have been most frequently applied to prevent or reduce anxiety during pregnancy and postpartum. It was found that indicated preventive interventions, that is, those aimed at reducing moderate or severe anxious symptomatology, were the most common in both pregnancy and postpartum. This is consistent with findings in other reviews investigating the efficacy of psychological interventions to address anxiety or anxiety disorders in the perinatal stage [36,37]. While early arrest of anxiety symptoms in the perinatal stage may help prevent the development of more serious mental health problems [63], most efforts have been aimed at reducing anxiety when it was already present. On the other hand, in this review it was observed that most of the interventions aimed at preventing perinatal anxiety were carried out during pregnancy (n = 18). These findings are in agreement with those found in other reviews [29,36,37], and they show us how little attention has been paid to the prevention of anxiety during postpartum. On the other hand, the advantage of performing psychological interventions during pregnancy is that they could be integrated into maternal education classes, which would reduce the associated stigma and costs [33]. Also, the benefits of preventing anxiety would extend to the baby before birth and would reduce the potential adverse consequences of experiencing anxiety during pregnancy for women, such as increased risk of postpartum depression. In addition, during gestation, women frequently seek health services and are more willing to receive help because they believe it will have a positive impact on their baby [18].

Regarding the therapeutic approach applied, mindfulness and CBT were the most employed approaches, although CBT was the one most associated with a significant reduction in anxiety levels. This is consistent with findings from other reviews where a greater number of interventions applying mindfulness have been observed [38], but a greater efficacy of CBT [36]. Our findings are also in line with the conclusions of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence [64] and Maguire et al. [8] who note that CBT is an effective intervention for addressing anxiety during the perinatal stage. Likewise, they agree with the recommendations of NICE [64] and the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health [65], which state that CBT should be the first-line treatment for addressing perinatal anxiety.

Regarding the format of application, it was observed that face-to-face interventions (n = 10) were as common as online interventions (n = 10). However, a greater number of interventions applied in the face-to-face format (n = 7) demonstrated their efficacy in reducing anxiety compared to the online format (n = 5). In this regard, it would be interesting to have studies comparing the efficacy of interventions according to the application format in order to draw reliable conclusions. It should be noted that during the perinatal stage interventions delivered via the Internet represent a tool with great potential [66], as they are usually more attractive and reduce the need to travel, one of the barriers associated with low access to treatments for psychological problems during this period [67]. Therefore, interventions developed online could be useful for preventing anxiety given their accessibility, anonymity, and cost-effectiveness [68].

Regarding the modality of application, most of the interventions were developed in a group setting (n = 9), and this format was also the one that showed the greatest efficacy (n = 6). This is interesting, since group interventions involve lower cost, high satisfaction for participants, and high compliance rates [63]. With respect to duration, it was found that the most frequent interventions consisted of four sessions (n = 7). Likewise, they were also the most effective. This seems to indicate that with brief interventions it would be possible to prevent perinatal anxiety. At the same time, having brief interventions would help facilitate adherence to them, since we are at a time in a woman’s life when one of the limitations to attending therapy is lack of time.

Finally, we believe it is important to highlight that regardless of the timing of the intervention, the type of preventive program, the therapeutic approach used, the delivery format, and the effectiveness of the intervention, it would be interesting to include in all interventions strategies aimed at addressing variables that have been shown to influence the development of perinatal anxiety. For example, it has been observed that women’s social or healthcare support can be a protective factor against perinatal anxiety [69]. Therefore, including strategies to improve social support in interventions could be beneficial. Another important aspect could be to include stress management strategies, as stress is often a risk factor for perinatal anxiety due to the multiple problems that can arise during pregnancy, such as miscarriage, stillbirth, or during the postpartum period, such as premature death, and difficulties in breastfeeding [70,71,72].

4.2. Limitations

Although, to our knowledge, this is the first review that analyzes preventive psychological interventions to address anxiety during pregnancy and postpartum, some limitations found should be pointed out. First, the existing controversy regarding the definition of anxiety is an important aspect to take into account, as the findings may vary depending on what each assessment instrument understands as anxiety. Also, the variability between the self-report instruments used and their cut-off points makes it difficult to interpret the results that may vary depending on what each assessment instrument understands as anxiety. Second, the review is limited to studies published in English, so the generalization of the findings is limited. Another limitation has to do with methodological aspects, such as the small sample size of some studies, [43,45], or the absence of a control group [44,49,55,61], and the scarcity of long-term follow-ups, which makes it difficult to generalize the results found.

The variability in the assessment instruments used and the shortcomings at the methodological level hinder the possibility of performing a meta-analysis of the findings, which could have provided additional information on the most effective type of intervention in terms of approach, duration, and application format. Another limitation was that publication bias was not assessed for the articles, as some of them did not meet the criteria required to perform a meta-analysis or complete Edger’s regression, which would have provided greater certainty about the results found. Likewise, the scarcity of interventions applied in the postpartum period makes it impossible to draw conclusions and extrapolate the results to the postpartum population. Additionally, this review excluded studies prior to 2015 and those based on high-risk populations (e.g., studies conducted on women with living in poverty situations, experiencing high-risk or twin pregnancies, or being victims of gender-based violence). Therefore, the generalization of the findings to these populations may be limited.

4.3. Future Research Directions

Future randomized controlled trials are required to evaluate the efficacy of preventive interventions during the perinatal stage, especially those aimed at universal prevention and during the postpartum period, as these are the interventions and the perinatal period that have been least researched. Another interesting methodological aspect would be to carry out long-term follow-up, as this would provide valuable information on which interventions maintain their efficacy over time.

5. Conclusions

This review provides updated knowledge on the preventive psychological interventions that have been carried out to address anxious symptomatology during the perinatal stage. The results show that the most common interventions are indicated prevention interventions, as well as that more attention has been given to the prevention of anxiety during pregnancy (see Table 3). The therapeutic approach that has been shown to be most effective is CBT. In addition, the results support a wide variety of delivery modes, including face-to-face, online, group, and individual, suggesting that psychological interventions can be tailored to the individual needs of women during this period. Given the negative consequences of untreated perinatal anxiety for mothers and children and women’s preference for psychological interventions, the present review argues for the availability and use of such interventions in the perinatal stage. Accordingly, it would be important to have mental health professionals to accompany women at this time in their lives. This would allow for more specialized care and devote more time and resources to perinatal mental health care, mitigating the possible consequences that may arise from it.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/brainsci15080861/s1, Table S1. Duplicate removal process using the RefWorks tool. Table S2. MAT: Quantitative Non-Randomized Studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.M. and A.V.; methodology, M.C.M. and A.V.; literature searches: A.V. and C.M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.V.; writing—review and editing, M.C.M., A.V. and C.M.P.; supervision, M.C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hadfield, K.; Akyirem, S.; Sartori, L.; Abdul-Latif, A.M.; Akaateba, D.; Bayrampour, H.; Daly, A.; Hadfield, K.; Abiiro, G.A. Measurement of pregnancy-related anxiety worldwide: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biaggi, A.; Conroy, S.; Pawlby, S.; Pariante, C.M. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 191, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, A.; Downes, C.; Carroll, M.; Gill, A.; Monohan, M. There is more to perinatal mental health care than depression: Public health nurses reported engagement and competence in perinatal mental health care. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, e476–e487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guide for Integration of Perinatal Mental Health in Maternal and Child Health Services. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240057142?_ga=2.252791369.1707140999.1715966799-1484490870.1713198781 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Tang, X.; Lu, Z.; Hu, D.; Zhong, X. Influencing factors for prenatal stress, anxiety and depression in early pregnancy among women in Chongqing, China. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 253, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.-L.; Falah-Hassani, K.; Shiri, R. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2017, 210, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falah-Hassani, K.; Shiri, R.; Dennis, C. The prevalence of antenatal and postnatal co-morbid anxiety and depression: A metaanalysis. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 2041–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, P.N.; Clark, G.I.; Wootton, B.M. The efficacy of cognitive behavior therapy for the treatment of perinatal anxiety symptoms: A preliminary meta-analysis. J. Anxiety Disord. 2018, 60, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrampour, H.; McDonald, S.; Tough, S. Risk factors of transient and persistent anxiety during pregnancy. Midwifery 2015, 31, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Val, A.; Míguez, M.C. Prevalence of antenatal anxiety in European women: A literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.; Knapp, M.; Parsonage, M. Lifetime costs of perinatal anxiety and depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 192, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Míguez, M.C.; Fernández, V.; Pereira, B. Depresión postparto y factores asociados en mujeres con embarazos de riesgo [Postpartum depression and associated risk factors among women with risk pregnancies]. Behav. Psychol. 2017, 25, 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Della Vedova, A.M.; Santoniccolo, F.; Sechi, C.; Trombetta, T. Perinatal Depression and Anxiety Symptoms, Parental Bonding and Dyadic Sensitivity in Mother-Baby Interactions at Three Months Post-Partum. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, T. Prenatal anxiety effects: A review. Infant Behav. Dev. 2017, 49, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufford, A.J.; Salzwedel, A.P.; Gilmore, J.H.; Gao, W.; Kim, P. Maternal trait anxiety symptoms, frontolimbic resting-state functional connectivity, and cognitive development in infancy. Dev. Psychobiol. 2021, 63, e22166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göbel, A.; Stuhrmann, L.Y.; Harder, S.; Schulte-Markwort, M.; Mudra, S. The association between maternal-fetal bonding and prenatal anxiety: An explanatory analysis and systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 239, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigoriadis, S.; Graves, L.; Peer, M.; Mamisashvili, L.; Tomlinson, G.; Vigod, S.N.; Dennis, C.-L.; Steiner, M.; Brown, C.; Cheung, A.; et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of antenatal anxiety on postpartum outcomes. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2019, 22, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Muñoz, M.F.; Soto-Balbuena, C.; Olivares-Crespo, M.E.; Marcos-Nájera, R.; Al-Halabí, S. Tratamientos psicológicos para los trastornos mentales o del comportamiento asociados con el embarazo, parto o el puerperio. In Fonseca Coord, Manual de Tratamientos Psicológicos: Adultos; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2021; pp. 607–633. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, A.; Ganho-Ávila, A.; Berg, M.L.-V.D.; Lupattelli, A.; Rodriguez-Muñoz, M.F.; Ferreira, P.; Radoš, S.N.; Bina, R. Emerging issues and questions on peripartum depression prevention, diagnosis and treatment: A consensus report from the cost action riseup-PPD. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 274, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mahen, H.; Fedock, G.; Henshaw, E.; Himle, J.A.; Forman, J.; Flynn, H.A. Modifying CBT for perinatal depression: What do women want?: A qualitative study. Cog. Behav. Pract. 2012, 19, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sockol, L.E. A systematic review of the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for treating and preventing perinatal depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 177, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughnan, S.A.; Wallace, M.; Joubert, A.E.; Haskelberg, H.; Andrews, G.; Newby, J.M. A systematic review of psychological treatments for clinical anxiety during the perinatal period. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2018, 21, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, C.L.; Dowswell, T. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for preventing postpartum depression. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD001134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simhi, M.; Sarid, O.; Cwikel, J. Preferences for mental health treatment for post-partum depression among new mothers. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2019, 8, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, S.M.; Haber, E.; Frey, B.N.; McCabe, R.E. Cognitive-behavioral group treatment for perinatal anxiety: A pilot study. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2015, 18, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister-Williams, R.H.; Baldwin, D.S.; Cantwell, R.; Easter, A.; Gilvarry, E.; Glover, V.; Green, L.; Gregoire, A.; Howard, L.M.; Jones, I.; et al. British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus guidance on the use of psychotropic medication preconception, in pregnancy and postpartum. J. Psychopharmacol. 2017, 31, 519–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misri, S.; Abizadeh, J.; Sanders, S.; Swift, E. Perinatal Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Assessment and Treatment. J. Women’s Health 2015, 24, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sockol, L.E. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal women. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 232, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özer, D.; Dişsiz, M. Effects of mindfulness-based practices in the perinatal and postpartum periods on women’s health: A systematic review. Psikiyatr. Güncel Yaklaşımlar 2025, 17, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalopoulos, C.; Chatterton, M.L. Economic evaluations of interventions designed to prevent mental disorders: A systematic review. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2015, 9, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A.F.; Patten, S.B.; Brugha, T.S.; Mojtabai, R. Has increased provision of treatment reduced the prevalence of common mental disorders? Review of the evidence from four countries. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, R.F.; Mrazek, P.J.; Haggerty, R.J. Institute of Medicine report on prevention of mental disorders: Summary and commentary. Am. Psychol. 1996, 51, 1116–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, R.F. Prevent depression in pregnancy to boost all mental health. Nature 2019, 574, 631–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, E.; Senger, C.A.; Henninger, M.; Gaynes, B.N.; Coppola, E.; Soulsby Weyrich, M. Interventions to Prevent Perinatal Depression: A Systematic Evidence Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rae, C.; McRae, R.; Holliday, E.; Chojenta, C. Interventions to Prevent Relapse or Recurrence of Preconception Anxiety and/or Depression in Perinatal Women: A Systematic Review. Matern. Child Health J. 2025, 29, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinkscales, N.; Golds, L.; Berlouis, K.; MacBeth, A. The effectiveness of psychological interventions for anxiety in the perinatal period: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Psychother. 2023, 96, 296–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.; Julce, C.; Sarkar, P.; McNicholas, E.; Xu, L.; Carr, C.; Boudreaux, E.D.; Lemon, S.C.; Byatt, N. Can psychological interventions prevent or reduce risk for perinatal anxiety disorders? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2023, 84, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callanan, F.; Tuohy, T.; Bright, A.M.; Grealish, A. The effectiveness of psychological interventions for pregnant women with anxiety in the antenatal period: A systematic review. Midwifery 2022, 104, 103169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayrampour, H.; Trieu, J.; Tharmaratnam, T. Effectiveness of eHealth interventions to reduce perinatal anxiety: A systematic review and meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2019, 80, 18r12386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmore, E.R.; Gustafsson, H.; Gilchrist, M.; Wyman, C.; O’Connor, T.G. Pregnancy-related anxiety: Evidence of distinct clinical significance from a prospective longitudinal study. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 197, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), Version 2018; McGill University: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2018; Available online: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria%20manual_2018%20-08-01_ENG.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Dennis-Tiwary, T.A.; Denefrio, S.; Gelber, S. Salutary effects of an attention bias modification mobile application on biobehavioral measures of stress and anxiety during pregnancy. Biol. Psychol. 2017, 127, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahoney, A.; Shiner, C.T.; Grierson, A.B.; Sharrock, M.J.; Loughnan, S.A.; Harrison, V.; Millard, M. Online cognitive behaviour therapy for maternal antenatal and postnatal anxiety and depression in routine care. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 338, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, R.; David, D. A randomized clinical trial of a new preventive rational emotive and behavioral therapeutical program of prepartum and postpartum emotional distress. J. Evid.-Based Psychother. 2015, 15, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Fontein-Kuipers, Y.J.; Ausems, M.; de Vries, R.; Nieuwenhuijze, M.J. The effect of Wazzup Mama?! An antenatal intervention to prevent or reduce maternal distress in pregnancy. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2016, 19, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi, F.; Pourasghar, M.; Khalilian, A.; y Shahhosseini, Z. Comparison of group cognitive behavioral therapy and interactive lectures in reducing anxiety during pregnancy: A quasi experimental trial. Medicine 2016, 95, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Kaur, B. Effect of progressive muscle relaxation on anxiety among antenatal mothers attending antenatal OPD of GGSMC & Hospital, Faridkot, Punjab. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. 2020, 12, 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Warriner, S.; Crane, C.; Dymond, M.; Krusche, A. An evaluation of mindfulness-based childbirth and parenting courses for pregnant women and prospective fathers/partners within the UK NHS (MBCP-4-NHS). Midwifery 2018, 64, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Cui, Y.X.; Zhou, Y.Q.; Li, Y.L. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on prenatal stress, anxiety and depression. Psychol. Health Med. 2019, 24, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, H.; Verbeek, T.; Aris-Meijer, J.L.; Beijers, C.; Mol, B.W.; Hollon, S.D.; Ormel, J.; Van Pampus, M.G.; Bockting, C.L.H. Effects of psychological treatment of mental health problems in pregnant women to protect their offspring: Randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2020, 216, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, H.M.; Hoogendoorn, A.W.; Honig, A.; Broekam, B.F.P.; van Straten, A. The Effectiveness of a Guided Internet-Based Tool for the Treatment of Depression and Anxiety in Pregnancy (MamaKits Online): Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e15172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughnan, S.A.; Sie, A.; Hobbs, M.J.; Joubert, A.E.; Smith, J.; Haskelberg, H.; Mahoney, A.E.J.; Kladnitski, N.; Holt, C.J.; Milgrom, J.; et al. A randomized controlled trial of ‘MUMentum pregnancy’: Internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy program for antenatal anxiety and depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 243, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, A.L.; Madsen, J.W.; Giesbrecht, G.F.; Campbell, T.; Carlson, L.E.; Dimidjian, S.; Letourneau, N.; Though, S.; Tomfohr-Madsen, L. Effects of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in pregnancy on psychological distress and gestational age: Outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness 2021, 12, 1173–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townshend, K.; Caltabiano, N.J.; Powrie, R.; O’Grady, H. A preliminary study investigating the effectiveness of the caring for body and mind in pregnancy (CBMP) in reducing perinatal depression, anxiety and stress. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 1556–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Jia, G.; Sun, S.; Ye, C.; Zhang, R.; Yu, X. Effects of an Online Mindfulness Intervention Focusing on Attention Monitoring and Acceptance in Pregnant Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Midwifery Womens Health 2019, 64, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Zhou, X.; Ye, C.; Li, J.; Sun, S.; Yu, X. Emphasizing mindfulness training in acceptance relieves anxiety and depression during pregnancy. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 312, 114540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazdanimehr, R.; Omidi, A.; Sadat, Z.; Akbari, H. The effect of mindfulness integrated cognitive behaviour therapy on depression and anxiety among pregnant women: A randomized clinical trial. J. Caring Sci. 2016, 5, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Mao, F.; Wu, L.; Huang, Y.; Sun, J.; Cao, F. Effectiveness of digital guided self-help mindfulness training during pregnancy on maternal psychological distress and infant neuropsychological development: Randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e41298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lin, P.; Sun, J.; Sun, Y.; Shao, D.; Cao, D.; Cao, F. Prenatal stress self-help mindfulness intervention via social media: A randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 32, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appleton, J.; Fowler, C.; Latouche, L.; Smit, J.; Booker, M.; Fairbrother, G. Evaluation of group therapy intervention for anxiety and depression in the postnatal period. Matern. Child Health J. 2025, 29, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughnan, S.A.; Butler, C.; Sie, A.A.; Grierson, A.B.; Chen, A.Z.; Hobbs, M.J.; Joubert, A.E.; Haskelberg, H.; Mahoney, A.; Holt, C.; et al. A randomised controlled trial of ‘MUMentum postnatal’: Internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety and depression in postpartum women. Behav. Res. Ther. 2019, 116, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Balbuena, C.; Kovacheva, K.; Rodríguez-Munoz, M.F. Ansiedad durante el embarazo y postparto. In Rodríguez-Muñoz y Caparrós González Coords, Psicología Perinatal en Entornos de Salud; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2022; pp. 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Antenatal and Postnatal Mental Health: Clinical Management and Service Guidance CG192; NICE: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. The Perinatal Mental Health Care Pathways. In Full Implementation Guidance; National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Segovia, N.; Rodriguez-Munoz, M.F.; Olivares, M.E.; Izquierdo, N.; Coronado, P.; Le, H.N. Healthy moms and babies preventive psychological intervention application: A study protocol. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, A.Z.; Rosales, M.; Ruiz-Segovia, N.; Rodríguez-Munoz, M.F. Sistemas e-Health en el periodo perinatal. In Rodríguez-Muñoz Coord., Psicología Perinatal: Teoría y Práctica; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 371–381. [Google Scholar]

- Yasuma, N.; Narita, Z.; Sasaki, N.; Obikane, E.; Sekiya, J.; Inagawa, T.; Nakajima, A.; Yamada, Y.; Yamazaki, R.; Matsunaga, A.; et al. Antenatal psychological intervention for universal prevention of antenatal and postnatal depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 273, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahò, M. Conscious decisions in perinatal hospice: Innovative support for parenthood, family psychophysical well-being, and grief processing. Ital. J. Psychol. 2024, 51, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juarez Padilla, J.; Lara-Cinisomo, S.; Navarrete, L.; Lara, M.A. Perinatal anxiety symptoms: Rates and risk factors in Mexican women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 18, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.M.J.; Nogueira, D.A.; Clapis, M.J.; Leite, E.P.R.C. Anxiety in pregnancy: Prevalence and associated factors. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2017, 51, e03253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Val, A.; Posse, C.M.; Míguez, M.C. Risk Factors for Prenatal Anxiety in European Women: A Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).