Abstract

Biodegradable mulching film (BMF) is a promising alternative to petroleum-based plastic mulching film. Thermal conductivity is an important quality factor of BMF that affects the heat transfer between ambient to soil and plant growth. The objective of this research was to enhance the thermal conductivity of fiber film through an environmentally friendly agent and optimized processing conditions. Response surface methodology (RSM) was used to optimize the processing conditions. With optimized process conditions of 70 g/m2 basis weight, 1.5% wet strength agent content, 0.5% neutral sizing agent content, 15% charcoal addition ratio, and 55 °SR beating degree, the films showed satisfactory thermal conductivity (0.0714 W/m·K) and high dry and wet tensile strengths (33.4 and 12.2 N). The addition of charcoal increased the thermal conductivity of the film by 34.31%. This promising result shows the biodegradable fiber film is able to increase soil temperature and meet the required temperature for crop growth.

1. Introduction

Plastic mulching film (PMF) has been widely used in modern intensive farming in order to inhibit weed growth, increase soil temperature, reduce water evaporation, control the leaching of crop nutrients, and increase the yield [1,2]. About one million tons of petroleum-based PMF is consumed annually in the farmlands of China [3,4]. However, petroleum-based PMF is not easily degraded in farmland, and its bio-degradation rate is very low even after years of exposure to soil microbial communities [5,6,7]. Furthermore, wind and rain erosion often cause the entire film to break into small pieces, thus making the recycling very difficult and time-consuming [8,9]. Ultimately, most plastic residues are commonly left in the field or burned by farmers, which leads to serious environmental pollution. Biodegradable materials mainly include biodegradable ceramics and biodegradable plastics [10,11]. To address this issue, the development of a biodegradable film with desired properties for both plant growth and environmental impact has become a research focus [12,13,14].

Biodegradable mulching film (BMF) is a promising alternative to petroleum-based PMF. At present, the degradable film can be mainly divided into photo-degradable, biodegradable, photo-biodegradable mulching, and plant fiber films [15,16,17]. Although some progress has been made in the first three degradable films, they are mainly synthesized by the co-polymerization of starch and other nutrients with degradable organic compounds. The adoption of these films is always favorable due to high costs, incomplete degradation, etc. To overcome this issue, researchers have developed plant fiber films derived from plant raw materials, such as softwood, hardwood, hemp, reed, waste cotton, straw, etc. Plant fiber film has great potential to replace petroleum-based PMF, due to its green, environmentally-friendly, biodegradable, and renewable properties [18,19,20,21,22]. In addition to plant fiber film, rice wastes like straw, husk, etc. have many applications [23,24,25]. Most previous studies related to plant fiber films have been focused on improving the mechanical strength, light transmittance, water vapor permeability, heat preservation, soil moisture conservation, and other functions of the films [26,27,28]. However, studies regarding the thermal conductivity of plant fiber film mulching are quite limited. In view of the positive effects of temperature on plant morphological attributions, physiological growth, photosynthetic characteristics, physiological chemistry, and crop growth and development [29,30], increasing the ambient temperature of crop growth is necessary.

One solution to improve the ambient temperature of crop growth is to improve the thermal conductivity of plant fiber film, which will accelerate the heat exchange inside and outside the greenhouse. In the daytime, high thermal-conductivity film allows the rapid input of external heat into the greenhouse in order to improve the ambient temperature of plant growth, thus enhancing the plant photosynthesis and formation of nutrient components. At night, high thermal-conductivity film allows the rapid output of internal heat into the atmosphere in order to lower the ambient temperature of plant growth, thus weakening the plant respiration and reducing the loss of daytime-photosynthesized nutrition components [31,32]. However, the thermal conductivity of the currently reported fiber film itself is very low [33]. Thus, developing plant fiber film with high thermal-conductivity is highly desirable.

Charcoal as an environmental-friendly additive has high thermal-conductivity and is, therefore, a great warming agent to improve the thermal conductivity of plant fiber film [34]. In this work, charcoal was used to enhance the thermal conductivity of fiber film. Furthermore, to avoid the addition of charcoal on the fiber film strength, wet strength agent and neutral sizing agent were used to enhance the dry and wet strengths of the film. Response surface methodology (RSM) was employed to optimize the processing variables (basis weight, neutral sizing agent, charcoal addition ratio, wet strength agent, and beating degree of the reaction mixture) that affect dry tensile strength, wet tensile strength, and thermal conductivity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Rice straw fiber used as raw material was produced by a D200 straw fiber extruder with particle size under 10 mm and an average aspect ratio of 22.8 to 58.3 [35]. Kraft pulp (KP) wood fiber with 27% moisture content (wb) was used for the framework to maintain mechanical strength. The wet strength agent used for tensile strength improvement was purchased from Xinghuo Chemical Plant (Mudanjiang, China). Polyamide polyamine epichlorohydrin resin (PPE) which was a water-soluble, cationic, thermosetting resin was used as a wet strength agent. The neutral sizing agent used for hydrophobicity enhancement was purchased from Jinhao Chemical Plant (Qingzhou, China). Alkyl ketene dimer (AKD) which was obtained by emulsifying stearoyl chloride and triethylamine hydrochloride was used as a neutral sizing agent. Charcoal obtained with particle size less than 0.12 mm, the thermal conductivity of 129 W/m·K from Tianjin Ebory Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China) was used for improving the thermal conductivity. All of these chemicals are laboratory level and triple distilled water was used for all solutions.

2.2. Preparation of Fiber Film

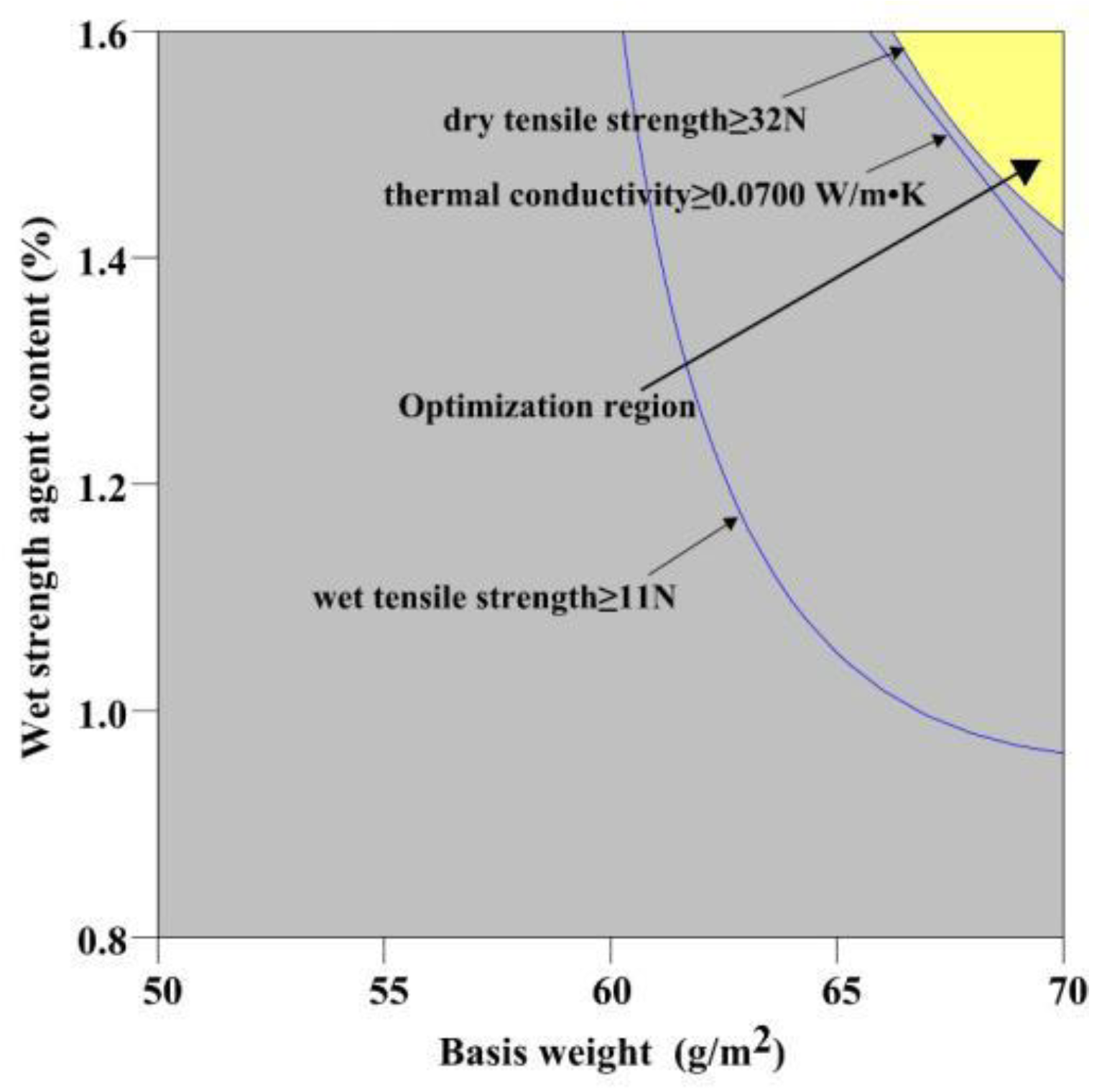

Rice straw fiber and KP wood fiber were beaten to form pulps with designed beating degrees. The beating degree was determined by a ZTG-100 pulp degree test machine (Yueming Small Test Machine Co., Ltd., Changchun, China) following Chinese Standard QB/T 24325 (2009). Charcoal, wet strength agent, and neutral sizing agent were added to the pulp and homogeneously mixed. The film samples were prepared following Chinese Standard QB/T 24324 (2009). Film samples were dried by a film dryer at a vacuum pressure above 96 kPa, temperature about 97 °C, and drying time 5–7 min. Drying film samples were conditioned at room temperature (23 ± 1 °C) and 50% ± 2% relative humidity for at least 24 h before testing. Figure 1 was the schematic illustration of manufacturing the BMF. Dry tension strength and wet tension strength was tested by a ZL-300 pendulum paper tensile strength test machine (Yueming Small Test Machine Co., Ltd., Changchun, China) according to Chinese Standard GB/T 12914 (2008) and GB/T 465.2 (2008), and thermal conductivity was measured by a DRL-III thermal conductivity tester (Xiangtan Xiangyi Apparatus Co., Ltd., Hunan, China) according to ASTM D 5470 (2006).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration.

2.3. Experimental Design

Initially, preliminary experiments were conducted following a single factorial method to identify the major processing parameters affecting the performance of the fiber film and to find out the optimal ranges. Five processing parameters including basis weight (g/m2), neutral sizing agent content (%), charcoal addition ratio (%), wet strength agent content (%), and beating degree (°SR) were selected based on the single factorial method.

The central composite design approach was used to study the effects and interaction of basis weight, neutral sizing agent content, charcoal addition ratio, wet strength agent content, and beating degree on dry and wet tensile strengths and thermal conductivity of rice straw fiber films. The central composite design is a type of response surface methodology (RSM). RSM is a general linear model in which attention is focused on characteristics of the fit response function; in particular, where optimum estimate response values occur. There were five levels of basis weight (50 to 70 g/m2), neutral sizing agent content (0.5% to 0.9%), charcoal addition ratio (0% to 20%), wet strength agent content (0.8% to 1.6%), and beating degree (35 to 55 °SR). The ranges and levels of independent variables are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Central composite design for five variables at five levels.

Equation (1) is a fitted empirical quadratic polynomial model as shown

where, y represents the response variable, β0 the intercept; β1, β2, β3, β4, and β5 are the coefficients of the independent variables; β11, β22, β33, β44, and β55 are the quadratic coefficients; β12, β13, β14, β15, β23, β24, β25, β34, β35, and β45 are the interaction coefficients; and x1, x2, x3, x4, and x5 are the independent variables. Multivariate regression analysis and optimization process were performed using Design Expert software version 6.0.10.0 (Stat Ease Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed and p value less than 0.05 is used as significant level. The optimum values of the independent variables were found out by conducting three-dimensional response surface analysis of the independent and dependent variables [36,37,38] The detailed experimental design is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Experimental design and results.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Regression Models

RSM, which combines mathematics and statistics together, is usually used to analyze the relative significance of different operating parameters even in complicated systems [39,40,41,42]. Therefore, this method was used to optimize the parameters used in this study. The central composite design was adopted to optimize the process to enhance the thermal conductivity of film made by charcoal and rice straw.

Thirty-six experiments were carried out to study the effects and interactions of basis weight, neutral sizing agent content, charcoal addition ratio, wet strength agent content, and beating degree on dry and wet tensile strengths and thermal conductivity of films. These are represented in Table 2. Table 2 also shows the values of dry tensile strength, wet tensile strength, and thermal conductivity at each experimental designed condition.

The regression model results indicated that the best models are the quadratic model for dry and wet tensile strengths, and a linear model for thermal conductivity. Table 3 shows the significance of the regression model parameters.

Table 3.

Significance of the regression model parameters.

The R2 for dry and wet tensile strengths and thermal conductivity models are 0.901, 0.873, and 0.781, respectively. The p values are all less than 0.001 showing that the models are highly significant, and there is only a 0.01%, 0.01%, and 0.1% chance of occurrence of model f value because of noise. The lack of fit was not significant with p values larger than 0.05 for all three models. The three model equations are shown as Equations (2)–(4).

where, y1, y2, and y3 are dry and wet tensile strengths (N) and thermal conductivity (W/m·K), respectively; x1, x2, x3, x4, and x5 are basis weight (g/m2), neutral sizing agent content (%), charcoal addition ratio (%), wet strength agent content (%), and beating degree (°SR), respectively.

3.2. Response Surface Analysis

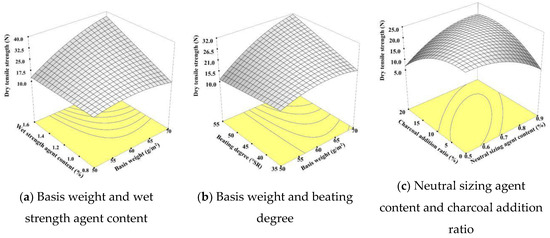

3.2.1. Interactive Effects on Dry Tensile Strength

The combined effect of basis weight and wet strength agent on dry tensile strength of the BMF with others staying constant (0.7% neutral sizing agent, 10% charcoal addition ratio, and 45 °SR beating degree) is shown in Figure 2a. The dry tensile strength increased as basis weight increased, however, the increase was not significant at low wet strength agent content. This is mainly because the dry tensile strength of the BMF was proportional to the fibers per unit area of the sample. Dry tensile strength also increased as wet strength agent content improved. Wet strength agent in the BMF not just forms a covalent bond with carboxyl of fiber, but enhances the network structure of the BMF through the self-bridging reactions within the wet strength agent and between the wet strength agent and fibers, thus wet strength agent has the function to increase the dry tensile strength [43]. Figure 2a also shows that the interaction of basis weight and wet strength agent content had a significant effect on dry tensile strength. Dry tensile strength reached the highest at 70 g/m2 basis weight and 1.6% wet strength agent content.

Figure 2.

Effects of five variables on dry tensile strength (a) Basis weight and wet strength agent content (b) Basis weight and beating degree (c) Neutral sizing agent content and charcoal addition ratio.

The combined effect of basis weight and beating degree on dry tensile strength of the BMF with others staying constant (0.7% neutral sizing agent content, 10% charcoal addition ratio, and 1.2% wet strength agent) is shown in Figure 2b. Dry tensile strength improved initially when basis weight increased from 50 to 60 g/m2 and then decreased slightly when the basis weight increased from 60 to 70 g/m2 at a low beating degree. At a low beating degree, even the addition ration keeps constant, the charcoal content increased as basis weight increased. The increase in charcoal reduces the binding force between fiber and fiber. Therefore, dry tensile strength decreased at a high basis weight. However, at a high beating degree, dry tensile strength increased as basis weight increased. This is mainly due to when at a high beating degree, the hydrogen bonds on the fiber surface and the bond strength between the fibers increased. The result also indicates that the effects of basis weight on dry tensile strength were greater than that of beating degree based on ANOVA analysis. The interaction of basis weight and beating degree also had significant effect on dry tensile strength. Dry tensile strength reached the highest at 70 g/m2 basis weight and 55 °SR beating degree.

The combined effect of neutral sizing agent content and charcoal addition ratio on dry tensile strength of the BMF with other parameters remaining constant (60 g/m2 basis weight, 1.2% wet strength agent content, and 45 °SR beating degree) is shown in Figure 2c. It was observed that at low charcoal addition ratio, dry tensile strength decreased as neutral sizing agent content improved. This is probably because the physical adsorption occurred between the cationic charges of neutral sizing agent and the anionic charges of pulp fiber. The formation of low polymer components (or discrete fragments) in the neutral sizing agent led to the uneven distribution of charges on the fiber surface and the localized cation patching points, thus causing the decrease in dry tensile strength. At a high charcoal addition ratio, dry tensile strength increased as neutral sizing agent content improved. Neutral sizing agent ester with cellulose. The neutral sizing agent acted as an adhesive on the surface of the fibers forming a strong hydrogen bond, which increased the binding force among pulp fibers and enhanced dry tensile strength [44]. According to Figure 2c, the effect of charcoal addition ratio on dry tensile strength was a little stronger than that of neutral sizing agent content based on an ANOVA analysis. The maximum dry tensile strength value appeared at 0.6% neutral sizing agent content and 7% charcoal addition ratio.

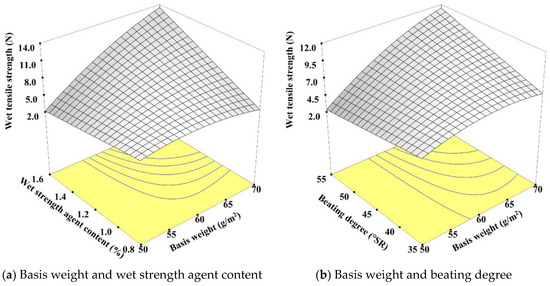

3.2.2. Interactive Effects on Wet Tensile Strength

The combined effect of basis weight and wet strength agent content on wet tensile strength of the BMF with others staying constant (0.7% neutral sizing agent content, 10% charcoal addition ratio, and 45 °SR beating degree) is shown in Figure 3a. Both wet strength agent content and basis weight had significant effects on wet tensile strength. Wet tensile strength increased as both wet strength agent content and basis weight improved, especially at large wet strength content and high basis weight. This is mainly because the increase of the fiber number of the BMF enhanced the bonding ability between the fibers and resulted in increasing wet tensile strength. Meanwhile, the wet strength agent was acting as resin for enhancing the fiber networks through forming a strong crosslink with fibers, thus improving wet tensile strength. Figure 3a also shows the interaction of wet strength agent and basis weight had a significant effect on wet tensile strength. The largest wet tensile strength was attained at 70 g/m2 basis weight and 1.6% wet strength agent content.

Figure 3.

Effects of five variables on wet tensile strength(a) Basis weight and wet strength agent content (b) Basis weight and beating degree (c) Neutral sizing agent content and beating degree (d) Charcoal addition ratio and wet strength agent content.

The combined effect of basis weight and beating degree on wet tensile strength of the BMF with others staying constant (0.7% neutral sizing agent content, 10% charcoal addition ratio, and 1.2% wet strength agent content) is shown in Figure 3b. Wet tensile strength decreased slightly with the increase of beating degree when basis weight lower than 60 g/m2. This is mainly because the overbeating degree shortened the fiber and weakened the strength of the single fiber, thus wet tensile strength declined. Wet tensile strength increased as the beating degree improved at 60 to 70 g/m2 basis weight. The continuous increase of basis weight enhanced the number of fibers unit area and enhanced the binding force among the fibers, thus improving wet tensile strength [45,46]. The highest wet tensile strength appeared at 70 g/m2 basis weight and 55 °SR beating degree.

Figure 3c shows the combined effect of neutral sizing agent content and beating degree on wet tensile strength of the BMF with other parameters remaining constant (60 g/m2 basis weight, 10% charcoal addition ration, and 1.2% wet strength agent content). At low neutral sizing agent content and beating degree, there was a tiny improvement in wet tensile strength as beating degree and neutral sizing agent content improved. But at large neutral sizing agent content and beating degree, wet tensile strength decreased significantly as beating degree and neutral sizing agent content improved. This may be because of the following reasons. The neutral sizing agent readily reacted with the fibers to form ketene ester derivatives on the surface of the fiber. Meanwhile, the exposure of the internal hydrophobic group (long chain alkyl group) to the surface of fibers increased the hydrophobic properties of the fiber, thus enhancing the wet tensile strength at low neutral sizing agent content. When the neutral sizing agent increased to the high level, the emulsion particles became larger and the dispersion capability became weaker, thus the wet tensile strength decreased. The sizing effect reduced, thus decreasing wet tensile strength accordingly. According to Figure 3c, the effect of beating degree on wet tensile strength was a little stronger than that of neutral sizing agent content. The largest wet tensile strength appeared at 0.5% neutral sizing agent content and 55 °SR beating degree.

Figure 3d shows the combined effect of charcoal addition ratio and wet strength agent content on wet tensile strength of the BMF with others staying constant (60 g/m2 basis weight, 0.7% neutral sizing agent content, and 45 °SR beating degree). Wet tensile strength enhanced uncommonly as wet strength agent content improved at low charcoal addition ratio from 0% to 10%. The chemical crosslink formed by the mutual reaction of the functional group of wet strength agent itself can generate an interlaced chain network structure around the fibers. The chemical crosslink with strong hydrophobic function prevented the water absorption and expansion of the hemicelluloses, thus the wet tensile strength increased. At a high charcoal addition ratio, the wet strength agent content did not show a significant effect on wet tensile strength. This is likely because, at a high charcoal addition ratio, the anionic charges of fiber and the cationic charges of wet strength agent reached to equal, thus the effect of wet tensile strength on wet tensile strength was not significant [47,48]. On the basis of Figure 3d, the effect of wet strength agent content on wet tensile strength was greater than that of charcoal addition ratio. The largest wet tensile strength appeared at a 6% charcoal addition ratio and 1.6% wet strength agent content.

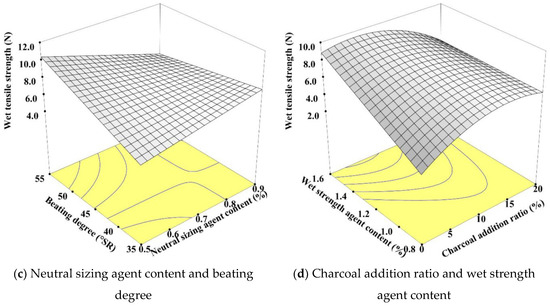

3.2.3. Effects on Thermal Conductivity

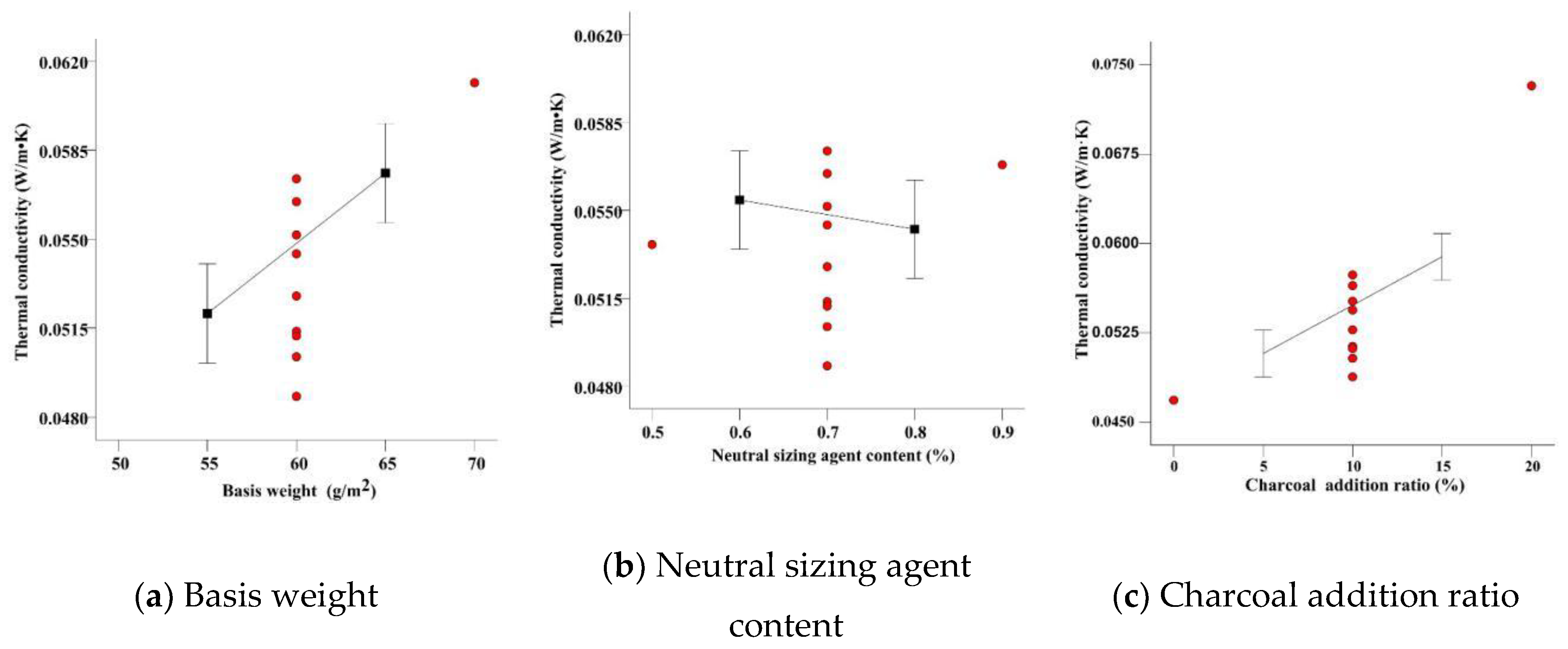

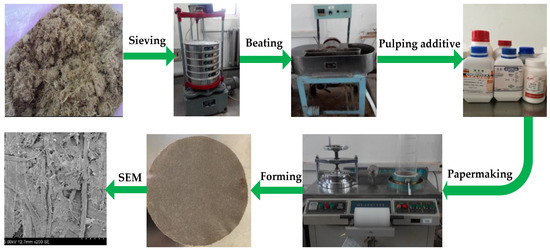

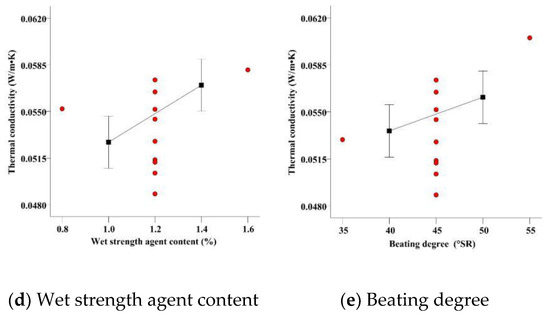

The regression model showed the linear relationship between the thermal conductivity and processing parameters (Equation (4)). Figure 4 shows the detailed effect of those processing parameters on the thermal conductivity. Thermal conductivity was positively correlated with basis weight (Figure 4a), charcoal addition ratio (Figure 4c), wet strength agent content (Figure 4d), and beating degree (Figure 4e), but negatively correlated with neutral sizing agent content (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Effects of five variables on thermal conductivity (a) Basis weight (b) Neutral sizing agent content (c) Charcoal addition ratio (d) Wet strength agent content (e) Beating degree.

It was found that the charcoal addition ratio was the most influential factor on thermal conductivity (Figure 4c). The highest thermal conductivity was 0.0733 W/m·K, which was achieved at the highest charcoal addition ratio (20%). Through the direct contact and tunnel effect, thermal conductivity was enhanced between the charcoal particles and fibers, thus improving the thermal conductivity of the whole film. Because of the existence of the fiber and charcoal particles, there were two types of thermal conductivities in the BMF. The first type is remote thermal conductivity formed by the mutual bonding of the fibers with a contact network path. The second type is short-range thermal conductivity formed by charcoal particles with the function of a bridging effect between the fibers [49,50]. Therefore, the thermal conductivity of the BMF was improved.

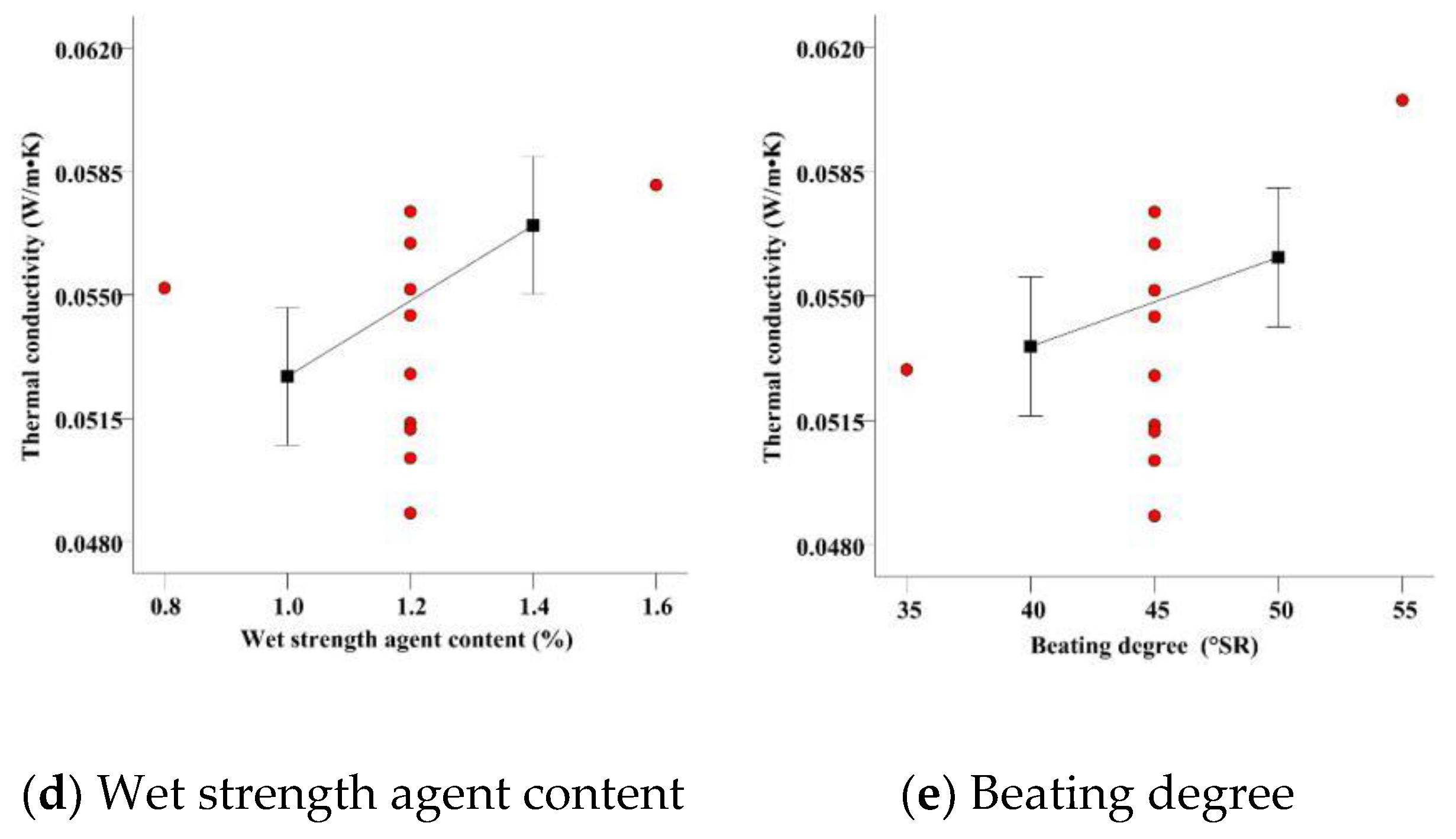

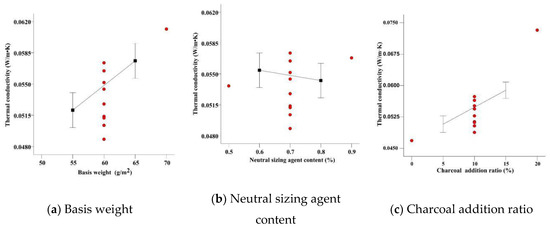

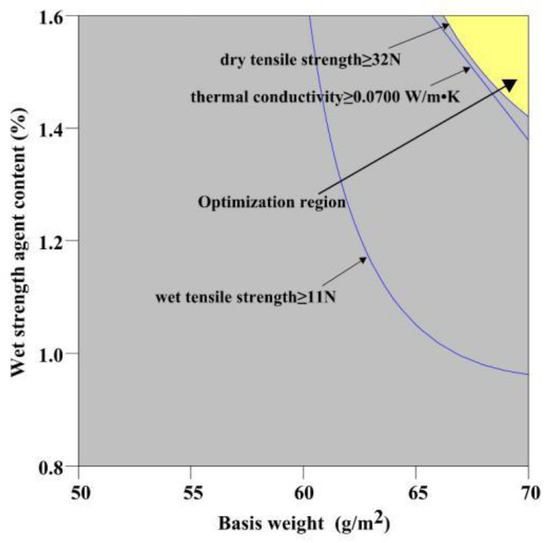

3.3. Optimization Analysis

The BMF with desired wet tensile strength, dry tensile strength, and thermal conductivity was obtained by optimized formulations and processing conditions. Due to the design model, the restrictions as previously required, and graphic optimization with the DX 6, the optimum conditions are basis weight 66 to 70 g/m2, wet strength agent content 1.4% to 1.6%, neutral sizing agent content 0.5%, charcoal addition ratio 15%, and beating degree 55 °SR (Figure 5). At the optimum condition, dry and wet tensile strengths are larger than 32 N and 11 N, and thermal conductivity is larger than 0.0700 W/m·K.

Figure 5.

Optimum analysis of technology parameters. Note: neutral sizing agent content 0.5%, charcoal addition ratio 2.4%, and beating degree 55 °SR.

3.4. Model Validation

The optimum model was validated by manufacturing the BMF at basis weight 70 g/m2, wet strength agent content 1.5%, neutral sizing agent content 0.5%, charcoal addition ratio 15%, and beating degree 55 °SR. Dry tensile strength, wet tensile strength, and thermal conductivity obtained from the validation experiment were 33.4 N, 12.2 N, and 0.0714 W/m·K, respectively, which were highly consistent with the predicted results (dry and wet tensile strengths larger than 32 N and 11N, and thermal conductivity larger than 0.0700 W/m·K). Hence, the optimum condition obtained from RSM design was reliable and applicable, and it indicates that RSM is a powerful tool for system optimization.

4. Conclusions

The addition of charcoal into rice straw fiber enhanced the thermal conductivity of BMF. The addition of charcoal increased the thermal conductivity of the film by 34.31% from 0.0469 to 0.0714 W/m·K. With optimum conditions (basis weight 70 g/m2, wet strength agent content 1.5%, neutral sizing agent content 0.5%, charcoal addition ratio 15%, and beating degree 55 °SR), the high dry tension strength (33.4 N) and high wet tension strength (12.2 N) were also achieved. In addition, the mechanical character of film also meets the agricultural requirements for plant growth. It is believed that the knowledge obtained from this research would be helpful to further improve the performance of plant fiber film.

Author Contributions

Methodology, X.M. and H.C.; Software, X.M. and H.C.; Validation, X.M.; Writing—original draft preparation, X.M.; Writing—review and editing, H.C. and D.W. This paper was prepared the contributions of all authors. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Science and Technology Research Project, grant number 2012BAD32B02-5 and National Key R&D Plan, grant number 2018YFD0201004.

Acknowledgments

This is contribution no. 19-070-J of the Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kasirajan, S.; Ngouajio, M. Polyethylene and biodegradable mulches for agricultural applications: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 32, 501–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lu, J.; Yi, Y.; Wang, H.; Nie, Z. Progress and prospect of the research of environmental friendly bast fiber mulch film. Plant Fiber Sci. China 2007, 29, 380–384. [Google Scholar]

- Bongarde, U.; Shinde, V. Review on natural fiber reinforcement polymer composites. IJESIT 2014, 3, 431–436. [Google Scholar]

- Halden, R. Plastics and health risks. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2010, 31, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wang, C.; Yi, Y. The development status of agricultural plastics mulching film and progress on degradable mulching films. Plant Fiber Sci. China 2007, 3, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, C.; Wallace, R.; Wszelaki, A.; Martin, J.; Cowan, J.; Walters, T.; Inglis, D. Deterioration of potentially biodegradable alternatives to black plastic mulch in three tomato production regions. HortScience 2012, 47, 1270–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Torley, P.; Halley, P. Emerging biodegradable materials: Starch-and protein-based bio-nanocomposites. J. Mater. Sci. 2008, 43, 3058–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; He, W.; Yan, C. ‘White revolution’to ‘white pollution’—Agricultural plastic film mulch in China. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Liu, E.; Shu, F.; Liu, Q.; Liu, S.; He, W. Review of agricultural plastic mulching and its residual pollution and prevention measures in China. J. Agric. Res. Environ. 2014, 31, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Kim, J.; Patil, S.; Park, J.; Park, S.; Lee, D. A wireless pressure sensor integrated with a biodegradable polymer stent for biomedical applications. Sensors 2016, 16, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróblewska-Krepsztul, J.; Rydzkowski, T.; Borowski, G.; Szczypiński, M.; Klepka, T.; Thakur, V. Recent progress in biodegradable polymers and nanocomposite-based packaging materials for sustainable environment. Int. J. Polym. Anal. Charact. 2018, 23, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkenstadt, V.; Tisserat, B. Poly (lactic acid) and Osage Orange wood fiber composites for agricultural mulch films. Ind. Crop Prod. 2010, 31, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Yan, C.; Zhao, C.; Chang, R.; Liu, Q.; Liu, S. Study on the pollution by plastic mulch film and its countermeasures in China. JAES 2009, 28, 533–538. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, C. Pollution and control countermeasures of farmland mulching film. HE J. Ind. Sci. Tech. 2015, 2, 177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Babu, R.; O’connor, K.; Seeram, R. Current progress on bio-based polymers and their future trends. Prog. Biomater. 2013, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immirzi, B.; Santagata, G.; Vox, G.; Schettini, E. Preparation, characterisation and field-testing of a biodegradable sodium alginate-based spray mulch. Biosyst. Eng. 2009, 102, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Huang, Z.; Yang, Y. A study on status and developmental trend of biodegradable plastic film. Chinese Agric. Sci. Bull. 2008, 9, 99. [Google Scholar]

- Briassoulis, D.; Dejean, C. Critical review of norms and standards for biodegradable agricultural plastics Part Ι. Biodegradation in Soil. J. Polym. Environ. 2010, 18, 384–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, A.; Li, J.; Li, F.; Wei, B. Study on the biodegradagility of plant fiber and starch dishware. J. Funct. Mater. 2009, 11, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Iwata, T. Biodegradable and bio-based polymers: Future prospects of eco-friendly plastics. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2015, 54, 3210–3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Pan, P.; Zhu, B.; Dong, T.; Inoue, Y. Mechanical and thermal properties of poly (butylene succinate)/plant fiber biodegradable composite. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2010, 115, 3559–3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, C.; Chen, R.; Sun, K. Development of application of plant fiber in full-biodegradable composites. Mater. Rev. 2007, 10, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Soltani, N.; Bahrami, A.; Pech-Canul, M.; González, L. Review on the physicochemical treatments of rice husk for production of advanced materials. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 264, 899–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, A.; Soltani, N.; Pech-Canul, M.; Gutiérrez, C. Development of metal-matrix composites from industrial/agricultural waste materials and their derivatives. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 46, 143–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, N.; Bahrami, A.; Pech-Canul, M.; Gonzalez, L. Improving the Interfacial Reaction between Cristobalite Silica from Rice Husk and Al–Mg–Si by CVD-Si 3 N 4 Deposition. Waste Biomass Valor. 2019, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gade, V.; Shirale, D.; Gaikwad, P.; Savale, P.; Kakde, K.; Kharat, H.; Shirsat, M. Influence of process parameters on the conductivity and surface morphology of polypyrrole films. Int. J. Polym. Mater. 2007, 56, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Li, H. Optimization of technical parameters for making mulch from rice straw fiber. TCSAE 2011, 27, 242–247. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Wang, C.; Yi, Y. The investigation report of plastics mulching film production and application in Japan. Plant Fiber Sci. China 2007, 6, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, D.; Yi, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, C. Study on the water conservation properties of environment friendly bast fiber mulch film. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2008, 10, 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, A.; Li, Z.; Gong, Y. Effects of biodegradable mulch film on corn growth and its degradation in field. J. CAU 2005, 2, 74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sandvik, S.; Heegaard, E.; Elven, R.; Vandvik, V. Responses of alpine snowbed vegetation to long-term experimental warming. Ecoscience 2004, 11, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welker, J.; Molau, U.; Parsons, A.; Robinson, C.; Wookey, P. Responses of Dryas octopetala to ITEX environmental manipulations: A synthesis with circumpolar comparisons. Glob. Chang. Biol. 1997, 3, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ho, V.; Segalman, R.; Cahill, D. Thermal conductivity of high-modulus polymer fibers. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 4937–4943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terao, T.; Zhi, C.; Bando, Y.; Mitome, M.; Tang, C.; Golberg, D. Alignment of boron nitride nanotubes in polymeric composite films for thermal conductivity improvement. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 4340–4344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; He, F. Analysis and Detection of Pulping and Papermaking; CHLIP: Beijing, China, 2003; pp. 234–283. [Google Scholar]

- Ay, F.; Catalkaya, E.; Kargi, F. A statistical experiment design approach for advanced oxidation of Direct Redazo-dye by photo-Fenton treatment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 162, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D. Design and Analysis of Experiments; ASU: Tempe, AZ, USA, 2017; pp. 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, R.; Swaminathan, T. Response surface modeling and optimization to elucidate and analyze the effects of inoculum age and size on surfactin production. Biochem. Eng. J. 2004, 21, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ming, X.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H. Optimization of technical parameters for making mulch from waste cotton and rice straw fiber. TCSAE 2015, 31, 292–300. [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar, K.; Pakshirajan, K.; Swaminathan, T.; Balu, K. Optimization of batch process parameters using response surface methodology for dye removal by a novel adsorbent. Chem. Eng. J. 2005, 105, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, A.; Cristóvão, R.; Loureiro, J.; Boaventura, R.; Macedo, E. Application of statistical experimental methodology to optimize reactive dye decolourization by commercial laccase. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 162, 1255–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fu, D.; Xu, Y.; Liu, C. Optimization of parameters on photocatalytic degradation of chloramphenicol using TiO2 as photocatalyist by response surface methodology. J. Environ. Sci.-China 2010, 22, 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Chen, H.; Han, Y.; Li, L.; Huang, Z. Optimization of technology parameters of making mulch from corn straw fiber. HL Pulp Paper 2011, 2, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, M.; Yassen, A.; Afify, M. Mechanical properties of rice straw fiber-reinforced polymer composites. Fiber Polym. 2011, 12, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.; Laurindo, J.; Yamashita, F. Effect of cellulose fibers addition on the mechanical properties and water vapor barrier of starch-based films. Food Hydrocoll. 2009, 23, 1328–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, N.; Yang, Y. Preparation and characterization of long natural cellulose fibers from wheat straw. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 8570–8575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chen, H.; Liu, S.; Dun, G.; Zhang, Y. Effect of plasticizers on properties of rice straw fiber film. J. NEAU (Engl. Ed.) 2014, 21, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.; Zheng, C.; Li, Y. Preparation and characterization of cellulose/chitosan composite film. J. Cellul. Sci. Technol. 2010, 2, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, L.; Qiu, J.; Liu, M.; Ding, S.; Shao, L.; Lü, S.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, Y.; Fu, X. Mechanical and thermal properties of poly (lactic acid) composites with rice straw fiber modified by poly (butyl acrylate). Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 166, 772–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Qiu, J.; Feng, H.; Zhang, M.; Lei, L.; Wu, X. Improvement of tensile and thermal properties of poly (lactic acid) composites with admicellar-treated rice straw fiber. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 173, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).