Abstract

This study addresses critical safety and productivity challenges faced by tower crane operators due to limited visibility during lifting operations. An intelligent crane-mounted visual system was implemented to enhance operator visibility, reduce communication faults, and improve overall crane performance in high-rise construction. The study followed a five-stage methodology: a literature review of visual and sensor technologies for collision prevention, site visits to identify visibility challenges, a comparative analysis of cranes with and without the vision system, and an impact assessment on safety and quality. The crane-mounted video system significantly improved efficiency, safety, and work quality, reducing cycle time, defined as the duration from hook pickup to placement, by 25%, with this reduction statistically significant at p < 0.001 using a two-paired t-test. Fewer near-miss incidents and lower idle times for workers and operators were observed, even when a less experienced operator operated the system. A cost–benefit assessment indicates that crane vision systems can generate annual economic benefits exceeding 240,000 NIS through accident prevention and time savings, based on the project context. This study’s contribution lies in providing a comprehensive, real-world evaluation of retrofitting older cranes with advanced vision technologies, demonstrating measurable impacts on safety, productivity, and economic outcomes.

1. Introduction

Tower cranes are a critical component of large-scale construction projects, yet their operation is associated with significant safety risks and productivity challenges. Operators often face limited visibility, blind spots, and communication issues, which increase the likelihood of accidents and reduce productivity. To mitigate these risks, various technological solutions have been developed, including crane-mounted vision systems, sensor-based monitoring, augmented reality, and machine-learning-based lift-planning frameworks.

Among these solutions, improving operator visibility remains a practical and direct approach to enhancing crane operations. Retrofitting existing cranes with camera-based vision systems offers a feasible means to support operators during lifting activities, improve situational awareness, and streamline material-handling processes, without requiring fundamental changes to crane structure or site layout.

This study evaluates a crane-mounted vision system in a live construction environment, grounded in socio-technical and situational awareness frameworks. It investigates impacts on safety, quality, and productivity. Moreover, an economic evaluation is presented to its benefits. By addressing these objectives, this study demonstrates actionable methods to enhance safety and efficiency in crane operations.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Crane Vision Systems and Productivity

Crane vision systems consist of a video camera mounted on the trolley of the tower crane and a monitor installed in the operator’s cabin. The camera, equipped with multiple zoom levels, moves along the crane’s jib with the trolley and wirelessly transmits live footage of the work area to the operator’s screen. This allows the operator to continuously monitor the loading and unloading zones, as well as the hook and load movement path. The primary purpose of the system is to address visual obstruction of work zones, a common problem on many construction sites. Such obstructions pose safety hazards and slow down crane operations.

As the primary material-handling equipment on construction sites, the tower crane often serves as a critical bottleneck to project progress. Time studies conducted on-site have shown that this visual system can significantly reduce cycle times [1,2], depending on site conditions and the nature of the lifting task. A recent work by Elgendi et al. [3] introduces a vision-based framework for accurately measuring tower crane cycle times using object-tracking algorithms. Tested on two case studies in Egypt, the system proved highly accurate, offering a practical solution to improve crane productivity estimation.

2.2. Human Factors and Safety Risks

Several studies have identified key risk factors and accident causes in tower crane operations. Human-related factors, such as operator inexperience, fatigue, miscommunication, and inadequate training, consistently contribute to crane accidents. Raviv et al. [4] demonstrated that technical failures are the most critical risk factor in the tower crane domain, whereas human-related failures are the second most significant. Zhang et al. [5] identified the critical causes of tower crane accidents as workers’ improper actions, inadequate safety training and inspection, low safety awareness, and mismanagement by safety engineers. Similarly, Tam and Fung [6] found that inadequate training and practitioner fatigue were key causes of unsafe tower crane practices in Hong Kong’s construction industry. Shin [7] examined 38 fatal tower crane accidents in Korea between 2001 and 2011 and found that 68.4% occurred during these processes, mainly due to non-compliance with procedures and unsafe worker actions. Jiang [8] identified major risk factors contributing to tower crane failures, including insufficient basic bearing capacity, inadequate structural resistance, improper binding or lifting operations, failure of monitoring equipment, hoisting dead zones, fatigue cracks in chords, and failed connections between components.

Ismail and Muhamad [9] identified six types of tower crane accidents: load loss, crane collisions, crane collapse, falls from height, caught in between, and struck by moving objects, with most accidents occurring during material hoisting, especially in the evening. Zhou et al. [10], adopting a socio-technical systems perspective, identified the top five critical factors as the safety and reliability of crane structural components, safe crane driver operation, the reliability of the tower crane foundation, the reliability of crane safety devices, and subcontractor safety inspections. Ali et al. [11] reviewed tower crane safety technologies (TCSTs) and categorized them into pre-construction management, real-time monitoring, anti-collision systems, and stability control.

Operators’ experience also significantly affects safety. Shapira and Lyachin [12] show that crane operators’ experience and proficiency have the greatest influence on construction site safety. Shapira et al. [1] report on the development and implementation of a tower-crane-mounted live video system, demonstrating significant time savings across various lifting operations. Lee et al. [2] present a prototype incorporating wireless video control and RFID technology to improve operational speed and safety. Wang et al. [13] propose a learning-based framework combining imitation and reinforcement learning to optimize tower crane lift paths.

2.3. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Crane Operations

Recent research highlights the growing role of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) in crane safety. Raj and Teizer [14] emphasize the link between crane-related accidents driven by human error and ML-based safety enhancement. Cho and Han [15] introduced a reinforcement learning framework for intelligent lift planning, while Li et al. [16] developed CraneGAN for automated tower crane layout planning. Jiang and Jiang [17] analysed crane boom dynamics, showing that luffing induces greater vibration and fatigue damage than lifting. These studies demonstrate the potential of AI-driven systems to complement human operators and enhance safety and productivity.

2.4. Limited Visibility and Vision-Based Solutions

Crane operators face several challenges that limit visibility, including obstructed loading and unloading areas, low-light conditions, shaded zones, inconvenient angles, and distant targets [1]. These blind spots increase accident risk and reduce operational efficiency. Vierling et al. [18] developed CNN-based human-detection methods, while Cheng and Teizer [19] improved operator awareness through laser scanning and worker tracking. Sun et al. [20] and Pazari et al. [21] applied YOLO-based systems to detect workers and falling-load danger zones. These studies collectively show that vision-based monitoring effectively mitigates safety risks.

2.5. Advanced Technology Integration

Technological advancements further enhance crane safety. Lee et al. [22] developed a sensor- and BIM-based navigation system for blind lifts. Lin et al. [23] integrated 4D BIM with AR, while Hu et al. [24] and Cai et al. [25] applied path-planning algorithms to reduce collisions. Jiang and Ding [26] used transfer learning to detect unsafe hoisting behaviours, and Jiao et al. [27] utilized UAV-based inspection for high-definition monitoring.

Integration of AI/ML systems with BIM, AR, and vision technologies enables dynamic hazard visualization and trajectory optimization, reducing human error and improving operational efficiency [15,16].

2.6. Inspection, Maintenance, and Historical Developments

Inspection and maintenance remain critical to crane safety. Radlov and Ivanov [28] and Rahim Abdul Hamid et al. [29] emphasized the importance of inspection frequency and operator training. Automated approaches include sensor-based collision prevention [30], blockchain-supported inspections [31], and game-theoretic safety modelling [32].

Historically, improving crane visibility has enhanced safety and productivity. Everett and Slocum [33] introduced CRANIUM, while Rosenfeld and Shapira [34] demonstrated the effectiveness of semi-automatic navigation, highlighting the feasibility of retrofitting older cranes.

3. Methods

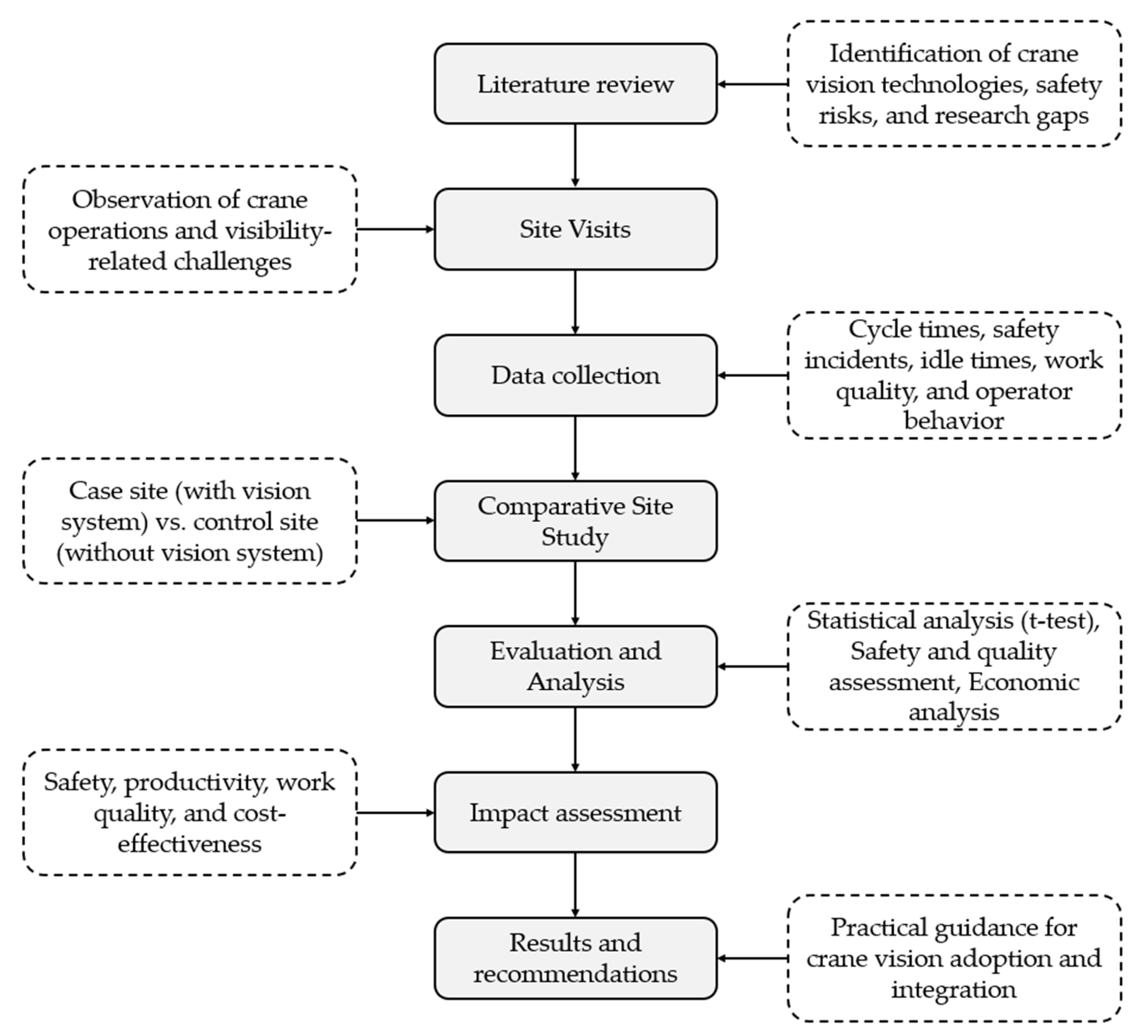

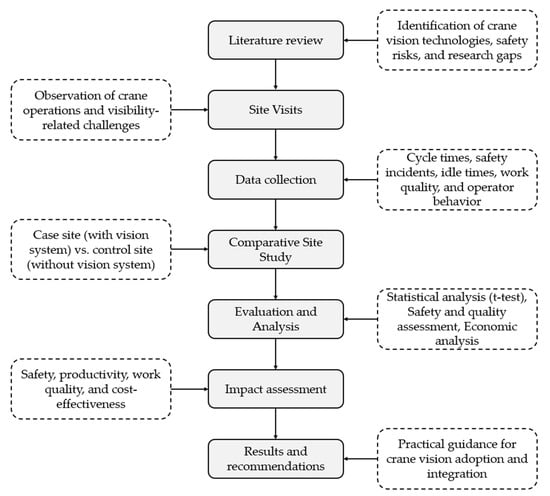

The research methodology is presented in Figure 1. First, a comprehensive literature review was conducted to summarize global advances in the use of cameras, sensors, and AI-enabled vision technologies for collision prevention and safety enhancement on construction sites. This was followed by site visits at several active construction projects to gain practical insights into operator visibility constraints, communication practices, and crane operation workflows faced by crane operators and site managers. These insights specifically included: (i) identification of recurring blind zones during lifting and landing operations; (ii) limitations in direct line-of-sight between the operator, load, and target location; (iii) communication difficulties between crane operators and signalers, particularly in congested or multi-crane environments; (iv) physical strain and awkward postures adopted by operators to compensate for limited visibility; and (v) operational delays caused by repeated pauses and repositioning due to uncertainty in load placement.

Figure 1.

Research flow chart.

Next, system implementation and data collection were conducted, including the installation of a crane-mounted vision system (CVS-9, Israel) and the continuous recording of operational data on lifting activities, cycle times, and safety events. A comparative site study was then performed, analysing a project that employed the crane vision system against a control group of cranes operating on the same construction site without such technology. This analysis focused on clearly defined performance indicators related to safety, productivity, work quality, and labor utilization.

Subsequently, quantitative evaluation and statistical analysis were carried out, including a t-test to assess whether the observed differences between the case study and control sites were statistically significant. An impact assessment was then conducted to evaluate the effects of implementing the vision system on site safety, work quality, labor productivity, and operator working conditions, thereby clarifying the mechanisms by which improved visual awareness influences performance. The Equivalent Uniform Annual Worth (EUAW) method was employed to assess the system’s economic feasibility. Finally, recommendations are presented based on the results and discussion.

The factors used for comparison between the case study site (with crane vision) and the control site (without crane vision) are presented in Table 1. The evaluation methods are also presented, with some grounded in the literature and others in the authors’ expert judgement and site-specific observations.

Table 1.

Factors used for crane vision evaluation.

4. Results and Discussion

The case study involves a residential building located in Haifa, Israel. The project comprises seven floors and covers a total area of 800 square meters. The total project budget is 62 million NIS, with a planned duration of 24 months. At the time of the research, the project was in the finishing phase, in its 20th month. A total of 95 workers were on site, and two flat-top tower cranes were in operation.

Twenty observations were taken at each stage (with/without a crane-mounted video camera system). The results are presented in Table 2. The implementation of the crane-mounted video camera system at the case study site led to substantial improvements in operational efficiency, safety, and work quality compared to the control site. Compared with the control site, the case study site demonstrated statistically significant improvements in cycle time and reductions in idle time, near-miss incidents, and labor input.

Table 2.

Comparison between the case study and the control sites.

The average cycle time with the crane vision system was significantly lower (mean = 5.25 min, standard deviation = 0.54) than without it (mean = 7.00 min, standard deviation = 0.63), p < 0.001, reflecting a 25% reduction in cycle time due to the use of the crane vision system in a Two-paired t-test.

Safety performance also improved over the 24-month project duration; only one near-miss incident was reported at the case study site, compared with three at the control site. This represents a 67% reduction in near-miss events. Work quality was rated high at the case site (versus moderate), and crane operator hygiene was evaluated as very high. Project duration was relatively shortened due to lower worker and crane operator idle times (4.0 and 1.25 min, respectively) compared to the control site (5.5 and 1.5 min). Despite having a crane operator with slightly less experience (5 vs. 7 years), the case study site outperformed the control, highlighting the effectiveness of the video system in enhancing performance across key construction metrics under comparable material handling conditions.

The combined results indicate that improved crane visibility through the vision system not only reduces cycle times and idle times but also enhances work quality and safety simultaneously. Reduced cycle times and smoother load handling correlate with fewer near-miss incidents, suggesting that operational efficiency directly supports safer work practices. High-quality placements of building components were achieved without compromising speed, demonstrating that enhanced visibility mitigates the traditional trade-off between productivity and quality.

4.1. Labor Input Savings

The system reduces both the direct working time of labor crews involved in load handling and the indirect working time of the crane operator, signaller, and management personnel engaged in the operation. The case study demonstrates a 25% reduction in typical crane cycle times (Table 1), aligning with findings from previous research. Shapira et al. [1] reported mean time savings of 14–29% in total travel time and 11–26% in total cycle time, which includes loading and unloading operations. Similarly, Lee et al. [2] found that total cycle times for individual lifting activities improved by 9.9–38.9%, with an average improvement of 26.5%. These results collectively underscore the significant impact of visual assistance systems on enhancing crane productivity.

The system also effectively saves at least one hour of labor per day for a typical six-person crew (in loading and unloading areas) whose work pace is largely dictated by the crane. In addition, it reduces the labor inputs of at least three higher-cost personnel: the foreman, crane operator, and signaller. The average daily savings in labor input amount to the equivalent of at least 10 work hours. On high-pressure construction sites where the crane operates intensively, the average daily savings can reach up to 20 work hours. The vision system reduces labor input not only through faster operation but also by significantly lowering maintenance and repair demands on the crane. It enables smoother handling, which minimizes wear on structural and mechanical components and prevents frequent damage to hoisting cables. These benefits result in substantial cost savings, estimated at over 50,000 NIS annually per crane, by avoiding downtime, spare parts, and unnecessary labor.

4.2. Quality

The vision system enhances the crane operator’s ability to position formwork and building components accurately. With a continuous visual of both the load and the work area, supported by a zoom function, the operator can assist ground crews in achieving precise placements. Beyond improved precision, the system helps prevent collisions and contact between the load and nearby objects, particularly in loading and unloading zones. These are critical moments where minor impacts can compromise quality and endanger site safety. Additionally, the results indicate that improvements in placement accuracy were achieved without sacrificing cycle time, highlighting that operational efficiency and work quality are mutually reinforced. Additionally, the system’s sensitive camera enables near “night vision,” allowing for accurate and high-quality work even in low-light conditions, such as during nighttime operations with only general floodlight illumination.

4.3. Occupational Health and Safety

While the system contributes to work efficiency, its most significant benefit lies in the realm of safety. Cranes are a major factor in many construction site accidents. By giving crane operators clear visibility into hidden, distant, and poorly lit areas, the vision system helps prevent hazardous situations. Operators can now directly observe how loads are rigged or unloaded, intervene when necessary, and even refuse to lift improperly secured loads or those using faulty lifting gear. This visibility increases the operator’s sense of responsibility and promotes a culture of caution among the team, as the operator can no longer claim, “I didn’t see how it was tied.”

A major source of crane-related accidents is miscommunication between the crane operator and the signalman or crew leader on the ground, who guides the operator via radio without visual contact. Mistakes can occur due to reversed directions (e.g., “right” meaning different things for each party), language barriers, overcorrections, or delayed reactions. In contrast, when the operator can visually confirm the load’s position in real time, complementing, rather than replacing, radio guidance, they operate more confidently and safely.

Additionally, the system improves the operator’s hygiene and ergonomics. It reduces physical strain on the eyes and body, eliminating the need to lean out of the cabin or squint to locate the load. The result is a calmer, less physically demanding work environment, enhancing both the operator’s well-being and the safety of workers and everyone around the crane work envelope.

4.4. Impact on Project Duration

Experienced users of the crane-mounted vision system report a time savings of at least two workdays per month, particularly during the structural frame stage. The value of each saved day, based on site overhead costs alone, is estimated at no less than 5000 NIS, totalling a monthly savings of approximately 10,000 NIS. Shortening the project duration benefits both the contractor and the developer by reducing financing costs, enabling earlier occupancy or productive use of the building, and avoiding delay penalties or securing early completion bonuses.

4.5. Economic Implications

The implementation of crane vision systems presents a compelling case for enhancing both safety and operational efficiency in construction projects. From an economic perspective, the investment in a crane vision system proves to be beneficial. The capital cost of purchasing the system is approximately 45,000 NIS, with an alternative rental option available at 2500 NIS per month. The system is estimated to have a useful economic life of five years, and annual maintenance and reinstallation costs are projected at around 5000 NIS. In terms of safety benefits, it is conservatively assumed that the system helps prevent at least two light accidents per year. According to Bachar et al. [35], the direct and indirect cost of each light accident is estimated at 75,000 NIS, resulting in an annual savings of 150,000 NIS purely from reduced incident costs. Additionally, by improving crane visibility and control, the system enhances operational efficiency, contributing to time savings estimated at 10,000 NIS per month. To quantitatively assess the economic viability of the system, the Equivalent Uniform Annual Worth (EUAW) method was employed using an annual effective interest rate of 5% (in monthly terms, it’s 0.41%). The results of the analysis show that the EUAW for purchasing the system is approximately 257,000 NIS, while the EUAW for renting it is about 242,044 NIS. These figures underscore the substantial economic advantage of integrating the system into regular crane operations.

The combination of safety improvements, shortened project durations, and considerable cost savings strongly supports the argument for widespread adoption of crane vision systems. Given the demonstrable benefits, there is an urgent need to revise current safety regulations and construction standards to mandate the use of such systems on tower cranes. Updating these standards would align policy with best practices in safety and productivity, ultimately leading to safer worksites and more efficient construction processes.

EAUW(purchase) = 10,000 × (F/A,0.41%,12) + 150,000 − 45,000 × (A/P,5%,5) − 5000 = 257,332 NIS

EAUW(rental) = 10,000 × (F/A,0.41%,12) + 150,000 − 2500 × (F/A,0.41%,12) = 242,044 NIS

While crane-mounted vision systems are not yet legally required by law, their proven safety and productivity benefits have made them a recognized best practice and increasingly common in high-risk or high-visibility construction projects. These systems are now frequently incorporated into internal safety protocols, particularly in operations involving blind lifts, congested urban sites, and multi-crane environments. Best-practice protocols typically include the integration of real-time video feeds into pre-lift planning procedures, formal operator training on visual system use, and the inclusion of visual monitoring as a standard component in method statements and lifting plans. Contractors should require the video system to be tested and documented during daily crane inspections, with recorded footage archived for safety audits and incident investigation. When combined with traditional communication protocols between operators and signallers, vision systems can significantly enhance spatial awareness and reduce the likelihood of load misplacement, collisions, and near-miss incidents. In practice, the use of crane-mounted cameras provides a practical and immediate layer of risk mitigation. Their growing presence on job sites reflects not a regulatory obligation, but a proactive response to operational complexity, safety expectations, and the need for greater precision in modern lifting operations.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the substantial safety, productivity, and quality gains associated with the implementation of a crane-mounted video camera system in active construction environments. The results from the comparative case study highlight measurable improvements in operational performance, even when operated by a less experienced crane operator. A 25% reduction in crane cycle time was achieved, translating into significant labor input savings and enhanced overall efficiency. Additionally, safety incidents, particularly near-miss events, were notably reduced, while improvements in work quality and ergonomic conditions for the operator were observed. A Benefit-to-Cost-Ratio analysis (BCR) shows that crane vision systems significantly improve safety and efficiency, with an annual economic benefit exceeding 240,000 NIS through accident prevention and time savings.

From an implementation perspective, this study highlights the potential of crane-mounted vision systems to improve safety and efficiency; however, the translation of these findings into policy and regulation requires further investigation. Future studies should examine context-specific implementation strategies, including regulatory differences across countries, cost implications for small and medium-sized contractors, and phased or incentive-based adoption pathways.

From a theoretical perspective, the findings align with broader concepts of human–machine interaction and safety optimization in construction operations. Methodologically, the comparative on-site approach offers practical insights but also limits the strength of causal inference, highlighting the need for broader, multi-site validation.

The visual monitoring system can not only improve real-time decision-making by offering continuous visibility of the lifting zones but also mitigate common sources of risk such as miscommunication, visual obstructions, and incorrect load handling. The system enables more precise placement of building components, smoother lifting operations, and a reduction in both crane and worker idle times. These effects collectively contribute to a shortened project duration and substantial cost savings in labor, equipment maintenance, and site overhead. From a financial standpoint, the system provides a highly favorable return on investment. Whether acquired through purchase or rental, the direct and indirect cost savings in labor, project time, equipment wear, and risk mitigation far exceed the system’s cost. More importantly, the potential to prevent even a single serious accident underscores the invaluable safety contribution of such technology.

The study provides empirical validation for the adoption of vision-based crane systems, reinforcing earlier findings in the literature while offering new evidence from a real-world implementation. It advocates for the retrofitting of existing crane fleets with intelligent vision technologies, especially in high-density and high-rise construction projects where visibility challenges are prevalent. As construction sites continue to grow in complexity, such systems represent a practical, cost-effective, and safety-enhancing innovation that should be increasingly integrated into standard crane operation practices.

Limitations of this research include a single case study conducted on a site with two comparative crane groups. In addition, the findings may be influenced by site-specific characteristics, operator behavior, and contextual factors that limit generalizability. Moreover, safety performance was evaluated using absolute counts of reported near-miss incidents over the same project duration, as standardized safety indicators (e.g., incidents per lifting operation) were unavailable, which limits the robustness of the safety comparison. Further research is recommended to elaborate on the research population. Further research is also needed for the system integration with autonomous trajectory planning of the crane lifting maneuvering.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.V. and I.M.S.; methodology, F.S., I.V. and I.M.S.; software, I.V.; validation, F.S., I.V. and I.M.S.; formal analysis, I.M.S.; investigation, I.V.; resources, I.M.S.; data curation, F.S. and I.V.; writing—original draft preparation, F.S.; writing—review and editing, I.M.S.; visualization, F.S.; supervision, I.M.S.; project administration, I.M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shapira, A.; Rosenfeld, Y.; Mizrahi, I. Vision system for tower cranes. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2008, 134, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, U.K.; Kang, K.I.; Kim, G.H.; Cho, H.H. Improving tower crane productivity using wireless technology. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2006, 21, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgendi, E.B.O.; Shawki, K.M.; Mohy, A.A. Video analysis for tower crane production rate estimation. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2023, 28, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raviv, G.; Fishbain, B.; Shapira, A. Analyzing risk factors in crane-related near-miss and accident reports. Saf. Sci. 2017, 91, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, L.; Zhao, T. Identification of critical causes of tower-crane accidents through system thinking and case analysis. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, V.W.; Fung, I.W. Tower crane safety in the construction industry: A Hong Kong study. Saf. Sci. 2011, 49, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, I.J. Factors that affect safety of tower crane installation/dismantling in construction industry. Saf. Sci. 2015, 72, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T. Safety risk analysis and control of tower crane. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 546, 042070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, F.; Muhamad, R. Risk Assessment of Tower Crane Operation in High Rise Construction. J. Adv. Res. Occup. Saf. Health 2018, 1, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W.; Zhao, T.; Liu, W.; Tang, J. Tower Crane Safety on Construction Sites: A Complex Sociotechnical System Perspective. Saf. Sci. 2018, 109, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.H.; Zayed, T.; Wang, R.D.; Kit, M.Y.S. Tower crane safety technologies: A synthesis of academic research and industry insights. Autom. Constr. 2024, 163, 105429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapira, A.; Lyachin, B. Identification and analysis of factors affecting safety on construction sites with tower cranes. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2009, 135, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Huang, C.; Yao, B.; Li, X. Integrated reinforcement and imitation learning for tower crane lift path planning. Autom. Constr. 2024, 165, 105568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.; Teizer, J. State of the Art Review of Technological Advancements for Safe Tower Crane Operation. In 41st International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction; International Association for Automation and Robotics in Construction (IAARC): Singapore, 2024; pp. 364–373. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S.; Han, S. Reinforcement learning-based simulation and automation for tower crane 3D lift planning. Autom. Constr. 2022, 144, 104620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Chi, H.L.; Peng, Z.; Li, X.; Chan, A.P. Automatic tower crane layout planning system for high-rise building construction using generative adversarial network. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2023, 58, 102202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Jiang, X. Fatigue life prediction for tower cranes under moving load. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2023, 37, 6461–6466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vierling, A.; Sutjaritvorakul, T.; Berns, K. Crane safety system with monocular and controlled zoom cameras. In ISARC. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction; IAARC Publications: Singapore, 2018; Volume 35, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, T.; Teizer, J. Modeling tower crane operator visibility to minimize the risk of limited situational awareness. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2014, 28, 04014004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Lu, X.; Wang, Y.; He, T.; Tian, Z. Development and Application of Small Object Visual Recognition Algorithm in Assisting Safety Management of Tower Cranes. Buildings 2024, 14, 3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazari, P.; Didehvar, N.; Alvanchi, A. Enhancing tower crane safety: A computer vision and deep learning approach. Eng. Proc. 2023, 53, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Cho, J.; Ham, S.; Lee, T.; Lee, G.; Yun, S.H.; Yang, H.J. A BIM-and sensor-based tower crane navigation system for blind lifts. Autom. Constr. 2012, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Petzold, F.; Hsieh, S.H. 4D-BIM based real time augmented reality navigation system for tower crane operation. In Construction Research Congress 2020; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2020; pp. 828–836. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Fang, Y.; Moehler, R. Estimating and visualizing the exposure to tower crane operation hazards on construction sites. Saf. Sci. 2023, 160, 106044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Ye, Z.; Chen, S.; Liang, X. Reducing Safety Risks in Construction Tower Crane Operations: A Dynamic Path Planning Model. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Ding, L. Unsafe hoisting behavior recognition for tower crane based on transfer learning. Autom. Constr. 2024, 160, 105299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Wu, N.; Zhang, X.; Fan, J.; Cai, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z. Enhancing tower crane safety: A UAV-based intelligent inspection approach. Buildings 2024, 14, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radlov, K.; Ivanov, G. Analysis of accidents with tower cranes on construction sites and recommendations for their prevention. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 951, 012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim Abdul Hamid, A.; Azhari, R.; Zakaria, R.; Aminudin, E.; Putra Jaya, R.; Nagarajan, L.; Yunus, R. Causes of crane accidents at construction sites in Malaysia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci 2019, 220, 12028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleiman, J.P.; Zankoul, E.; Khoury, H.; Hamzeh, F. Sensor-based planning tool for tower crane anti-collision monitoring on construction sites. In Construction Research Congress 2016; ACES Library: Urbana, IL, USA, 2016; pp. 2624–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhong, B.; Li, H.; Chi, H.L.; Wang, Y. On-site safety inspection of tower cranes: A blockchain-enabled conceptual framework. Saf. Sci. 2022, 153, 105815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Zheng, X.; Shao, B.; Jin, L. Safety supervision of tower crane operation on construction sites: An evolutionary game analysis. Saf. Sci. 2022, 152, 105578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, J.G.; Slocum, A.H. Cranium: Device for improving crane productivity and safety. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 1993, 119, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, Y.; Shapira, A. Automation of existing tower cranes: Economic and technological feasibility. Autom. Constr. 1998, 7, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachar, R.; Urlainis, A.; Wang, K.C.; Shohet, I.M. Optimal allocation of safety resources in small and medium construction enterprises. Saf. Sci. 2025, 181, 106680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.