Featured Application

The proposed ontology supports the semantic integration and comparison of green-synthesized nanomaterials for environmental remediation by unifying material properties, remediation mechanisms, performance indicators, and provenance information. It enables sustainability-aware assessment of adsorption and photocatalytic systems across heterogeneous studies and provides a FAIR-compliant foundation for transparent data querying and future integration with explainable AI tools.

Abstract

Green-synthesized nanomaterials have emerged as promising candidates for environmentally sustainable remediation; however, experimental evidence describing their synthesis routes, physicochemical properties, remediation performance, and sustainability-relevant attributes remains fragmented, inconsistently reported, and difficult to integrate across studies. This work addresses this challenge by proposing an ontology-based semantic framework for the interoperable integration of green-synthesized nanomaterials, contaminants, and remediation processes, incorporating explicit provenance metadata and structured sustainability descriptors. The ontology was developed using the Linked Open Terms (LOT) methodology and implemented in OWL 2 DL, with selective alignment to established vocabularies including eNanoMapper, ChEBI, ENVO, and PROV-O. Adsorption and photocatalysis were instantiated as representative remediation mechanisms to evaluate the framework’s capacity to accommodate structurally distinct processes. Logical reasoning and SHACL-based validation were applied to assess semantic consistency, provenance traceability, and data completeness. The results demonstrate that the proposed ontology effectively integrates heterogeneous experimental data within a unified, FAIR-compliant semantic framework, supports conservative and provenance-aware inference, and enables comparative analysis across mechanistically diverse remediation systems without structural modification. This ontology-based approach provides a robust foundation for sustainability-aware knowledge integration in environmental nanotechnology and establishes the basis for future extensions involving data quality assessment and explainable AI-driven analysis.

1. Introduction

The rapid evolution of green nanotechnology has positioned biosynthesized and green-synthesized nanomaterials as key enablers of environmentally sustainable remediation strategies. By employing biological resources, benign solvents, and low-energy synthesis routes, these materials offer reduced toxicity profiles and lower environmental burdens compared with conventionally produced nanomaterials, while maintaining high efficiency in the removal of hazardous contaminants from water and soil systems [1,2]. Their demonstrated effectiveness in adsorption and photocatalytic processes underscores their growing relevance in addressing persistent environmental pollution challenges [3,4].

Despite this progress, the advancement of green nanomaterials toward scalable and reproducible environmental applications is increasingly constrained by data-related limitations rather than by material performance alone. Contemporary research produces large volumes of heterogeneous experimental data describing synthesis conditions, physicochemical properties, operational parameters, and remediation outcomes. However, this information is frequently reported using inconsistent terminologies, variable measurement protocols, and narrative descriptions that lack formal structure. In particular, critical operational variables—such as pH, temperature, catalyst or adsorbent dosage—and key performance metrics, including removal efficiency and adsorption capacity, are often documented in incompatible formats, severely limiting cross-study comparability and reproducibility [3,4,5]. As a result, potentially valuable experimental evidence remains fragmented across isolated information silos.

To enable meaningful reuse of this growing body of knowledge, such datasets must be transformed into what is increasingly referred to as AI-ready data. Current benchmarks in data-intensive research and Industry 4.0 initiatives emphasize that AI readiness requires more than machine-readable formats alone; data must be enriched with explicit semantic structure, standardized descriptors, and formal provenance information to support automated reasoning, validation, and reliable downstream analytics [6,7,8]. Within this context, Semantic Web technologies—particularly ontologies and knowledge graphs—have emerged as a robust solution for managing heterogeneity, enabling interoperability, and ensuring shared conceptual understanding across disciplines [9,10].

Existing semantic resources, including chemical and environmental ontologies such as ChEBI [11] and EnvO [12], provide well-established foundations for representing chemical entities and environmental contexts. Nevertheless, a critical gap persists in the formal semantic representation of green synthesis pathways and their associated sustainability implications. Current models rarely encode biosynthetic routes, solvent greenness, energy demand, or material reusability in a manner that supports structured comparison or computational assessment. This limitation is particularly significant given the growing need to align nanomaterials research with international environmental management frameworks, notably the ISO 14000 and ISO 14001 series [13,14], which emphasize lifecycle thinking, environmental aspects, and continuous improvement. Recent studies have shown that integrating ontologies with process-chain and materials knowledge modeling is essential for the effective digitalization and system-level understanding of materials science workflows [15,16].

In response to these challenges, this work proposes an ontology-driven semantic framework that prioritizes interoperability and reuse rather than the creation of an isolated domain model. The framework is built upon the extension and systematic reuse of the eNanoMapper ontology [17], which is adopted as a central interoperability hub. By leveraging eNanoMapper’s established structure for nanomaterial characterization, the proposed approach integrates physicochemical descriptors, remediation mechanisms, green synthesis attributes, and sustainability indicators within a unified semantic model. This design enables:

- The standardized representation of green-synthesized nanomaterials together with their biosynthetic routes and synthesis conditions [18,19].

- The structured organization of experimental parameters and remediation outcomes into machine-actionable formats, conceptually analogous to hierarchical semantic compression approaches used in computer vision and knowledge encoding [8,20].

- The enforcement of data consistency and quality through the application of structural validation mechanisms and constraint-based modeling [21,22].

By embedding these capabilities within a semantically grounded architecture, the proposed framework adheres to the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data principles [23] and establishes a foundation for transparent, reproducible, and explainable AI (XAI) applications in environmental engineering. In doing so, it addresses not only the technical challenges of data integration but also the broader sustainability and governance requirements increasingly expected of green nanotechnology research.

The innovative contribution of this work lies not in the creation of another domain ontology, but in the integration of sustainability, remediation mechanisms, and provenance into a unified, machine-actionable semantic framework. Unlike existing ontologies that primarily focus on material characterization or regulatory nanosafety, the proposed model formalizes ISO 14000-aligned [13,14] sustainability descriptors as first-class semantic entities, enabling explicit reasoning and validation rather than narrative annotation. Furthermore, the ontology adopts a mechanism-agnostic design that supports structurally distinct remediation processes—such as adsorption and photocatalysis—without requiring architectural modification, thereby demonstrating true generality. A further novelty is the explicit semantic treatment of incomplete or missing sustainability data, which prevents unsupported inferences and preserves the integrity of environmental assessments. Finally, by embedding provenance, validation constraints, and interoperability from the outset, the framework enables AI-ready data generation by design, establishing a robust foundation for future explainable and knowledge-guided artificial intelligence applications.

2. Related Work

2.1. Green-Synthesized Nanomaterials for Environmental Remediation

The rapid development of green nanotechnology has positioned biosynthesized and environmentally benign nanomaterials as key agents for sustainable remediation of contaminated water and soil systems. Green-synthesized nanomaterials—produced using plant extracts, biopolymers, low-toxicity solvents, or energy-efficient routes—offer reduced environmental burden while maintaining high removal efficiencies for a wide range of pollutants.

Reviews in this area consistently report the effectiveness of materials such as zero-valent iron nanoparticles, polymer–nanoparticle composites, and bio-derived adsorbents for the removal of dyes, heavy metals, and emerging contaminants [2,4,18,24].

Despite strong experimental performance, the literature reveals persistent shortcomings that limit knowledge reuse. Synthesis conditions, physicochemical descriptors, and remediation outcomes are frequently reported using heterogeneous terminologies and inconsistent levels of detail. Sustainability claims—such as reduced toxicity, recyclability, or low energy demand—are often qualitative and rarely linked to standardized environmental management criteria. As a result, comparative assessment across material classes and synthesis routes remains difficult, and the integration of results into reusable, machine-actionable datasets is severely constrained.

These limitations highlight the need for structured knowledge representations capable of capturing not only material identity but also synthesis context, operational conditions, lifecycle considerations, and experimentally grounded performance indicators in a unified semantic framework.

2.2. Photocatalytic Nanomaterials for Environmental Remediation

Photocatalysis represents a distinct and increasingly important class of remediation mechanisms within green nanotechnology. Semiconductor-based nanomaterials—most notably TiO2 and its doped or composite derivatives—have been extensively investigated for the degradation of organic pollutants through light-driven redox reactions [3].

More recent studies have expanded this landscape to include green-synthesized photocatalysts, visible-light-active systems, and hybrid materials incorporating carbon-based components such as carbon quantum dots, which enhance charge separation and light absorption [2,4].

While photocatalytic systems demonstrate strong potential for sustainable remediation, they introduce a level of mechanistic and operational complexity that is rarely addressed in a standardized manner. Critical parameters such as band-gap energy, irradiation wavelength, light intensity, catalyst loading, and reactive oxygen species generation are often reported inconsistently or incompletely. Moreover, sustainability assessments for photocatalysis—particularly those related to energy demand and lifecycle impacts—are seldom formalized, despite their central relevance to environmentally responsible deployment, as outlined in the ISO 14000 family of standards [13,14].

From a knowledge-management perspective, photocatalysis exposes the limitations of static material-centric representations. Effective modeling requires explicit semantic links between material properties, irradiation conditions, reaction pathways, and performance outcomes [15,16]. The absence of such integrated representations further reinforces the need for ontology-based frameworks [17,25] capable of capturing mechanistically diverse remediation processes within a coherent and interoperable structure.

2.3. Environmental Sustainability and ISO 14000 Reporting

The ISO 14000 and ISO 14001 standards establish internationally recognized principles for environmental management systems, emphasizing lifecycle thinking, resource efficiency, waste minimization, and transparent documentation [13,14].

In the context of green nanomaterials, these principles are directly relevant to synthesis routes, remediation processes, and material reuse cycles. However, sustainability-related descriptors remain weakly formalized within scientific datasets, and compliance with ISO-aligned reporting practices is rarely explicit. Recent efforts in digitalizing material knowledge have emphasized that such standards must be integrated into ontology-driven frameworks to ensure system-level understanding [15,16].

Most remediation studies embed sustainability considerations within narrative discussion rather than structured metadata, limiting their utility for systematic evaluation or decision support. The lack of standardized sustainability descriptors hinders cross-study comparison and prevents automated reasoning over environmental impacts. This disconnect between experimental practice and environmental management standards represents a critical gap that semantic technologies are well positioned to address.

2.4. Computational Semantics and Ontology-Based Knowledge Representation

The formalization of environmental and chemical knowledge through semantic technologies has expanded significantly in response to challenges associated with data heterogeneity, fragmentation, and limited reusability. Foundational ontologies such as ChEBI provide standardized vocabularies for chemical entities [11], while the Environment Ontology (EnvO) captures biomes, environmental features, and stressors relevant to ecological and regulatory contexts [12].

These resources have played a central role in harmonizing terminology across disciplines; however, their scope remains largely descriptive and static. Such ontologies provide limited support for modeling synthesis pathways, remediation mechanisms, or experimentally derived performance metrics, particularly for nanomaterial-enabled processes arising from green synthesis routes [2,24]. Consequently, they cannot independently support sustainability-aware integration of remediation data or enable process-level reasoning across heterogeneous studies.

2.5. Nanomaterial-Focused Semantic Models and Their Limitations

Within nanotechnology, the most significant semantic modeling effort to date is eNanoMapper [17], which integrates multiple ontologies to support standardized description of nanomaterial composition, physicochemical properties, and toxicological profiles. eNanoMapper represents a substantial advance in nanosafety and regulatory reporting and has achieved broad adoption within the research community.

However, its design priorities reflect regulatory risk assessment rather than sustainability-oriented performance evaluation. Green synthesis pathways, solvent greenness, reuse cycles, remediation efficiency metrics, and lifecycle attributes are underrepresented. This limitation is particularly evident for widely studied systems such as zero-valent iron nanoparticles and carbon-based nanomaterials, which are extensively reported for environmental remediation [2,4,24] but lack unified semantic representations linking synthesis, performance, and sustainability. These characteristics position eNanoMapper not as a complete solution, but as a robust interoperability hub that can be extended to incorporate ISO 14000-aligned sustainability metadata [13,14].

2.6. Ontology-Driven Process Modeling, Interoperability, and Validation

Recent work increasingly recognizes that isolated material descriptions are insufficient for large-scale digitalization. The concept of ontology–knowledge collaboration has emerged as a strategy for modeling complex, process-driven systems. Wang et al. [15] demonstrated that semantic integration across design and process layers improves consistency in complex engineering domains, while Garcia-Trelles et al. [16] proposed ontology-driven process-chain modeling as a foundation for digital materials science.

These approaches mark a shift from static taxonomies toward dynamic representations of material transformation but remain largely focused on manufacturing and engineering workflows rather than environmental remediation or sustainability assessment.

Interoperability and data quality remain central challenges. Titocci et al. [26] emphasized the necessity of both manual and automated alignment strategies to reconcile heterogeneous vocabularies—an issue directly applicable to physicochemical descriptors and performance metrics reported across remediation studies. In parallel, the push toward AI-ready data has highlighted the limitations of weakly structured datasets. Barbosa-Santillán and León-Sandoval [8] showed that semantic technologies must precede probabilistic and machine learning models to ensure consistency, interpretability, and reliable inference.

Beyond conceptual modeling, validation of semantic structures has become a critical requirement. Libraries such as rudof [22], which support SHACL and ShEx constraint languages, enable explicit validation of data completeness and structural conformance [21].

However, their effectiveness depends on the availability of domain-specific ontologies that encode sustainability-relevant constraints—an area that remains underdeveloped in green nanomaterials research.

2.7. Synthesis and Identified Research Gap

Taken together, the reviewed literature reveals a clear disconnect between advances in green nanomaterial remediation and the semantic infrastructures required to integrate, validate, and reuse the resulting knowledge. Existing ontologies provide strong foundations for chemical classification [11], environmental context [12], and nanosafety [17], yet they fall short in representing green synthesis pathways, mechanistically distinct remediation processes such as photocatalysis [3], and ISO-aligned sustainability indicators [13,14] within a unified framework.

The present study addresses this gap by extending established semantic resources to bridge material characterization with sustainable environmental management. By integrating process-level modeling [15,16], provenance [7], and sustainability-aware descriptors within an interoperable ontology, this work contributes a validated, AI-oriented knowledge ecosystem [6,8] tailored to contemporary green remediation research. Table 1 shows a comparative overview of revised nanomaterials and related work.

Table 1.

Comparative overview of related work on semantic technologies and green nanomaterials for environmental remediation.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Ontology Development Methodology

The construction of the proposed semantic framework was guided by the Linked Open Terms (LOT) methodology [27]. LOT is an industrial-oriented, iterative workflow specifically designed to facilitate the engineering of ontologies through the reuse of existing conceptual assets, thereby ensuring high levels of interoperability while optimizing developmental resources. Following the strategic requirements for environmental knowledge management, the methodology was executed through four distinct phases:

Phase 1: Requirements Elicitation and Knowledge Acquisition. The foundational requirements were established by identifying the core information needs of the green remediation domain. This was achieved through the formulation of competency questions (CQs) and the systematic analysis of experimental datasets concerning green-synthesized nanomaterials [20,21,25]. A primary requirement identified during this phase was the necessity for alignment with international environmental management standards, specifically the ISO 14000 family, to ensure that the resulting data structures support life-cycle thinking and regulatory compliance [13,14,15,16].

Phase 2: Selection and Assessment of Reusable Ontological Assets. In adherence to the principle of ontological parsimony and reusability [28,29], an extensive survey of existing semantic models was performed. eNanoMapper [19] was selected to serve as the central interoperability hub for the framework. Its established architecture for nanomaterial characterization provides a robust nucleus for the integration of peripheral ontologies, including ChEBI [11] for molecular classification and EnvO [12] for environmental context. This “hub-and-spoke” approach avoids the creation of redundant vocabularies and fosters a unified semantic landscape.

Phase 3: Formal Implementation and Extension. The eNanoMapper HUB was extended to incorporate specialized modules that were previously absent or underrepresented. These include formal representations of biosynthetic pathways, green reducing agents, and specific remediation performance indicators, such as adsorption isotherms and removal kinetics [5,18,30]. The formalization was implemented using the OWL API [31] and Protégé, ensuring strict compliance with the OWL 2 Web Ontology Language specifications for description logic and computational tractability [32,33].

Phase 4: Structural Validation and Quality Assurance. The final phase focused on transforming the resulting knowledge into AI-Ready Data. To guarantee data integrity beyond simple logical consistency, structural constraints were implemented using SHACL (Shapes Constraint Language) and ShEx (Shape Expressions). This validation layer, supported by high-performance libraries such as rudof [24], ensures that the RDF data generated by the framework adheres to the rigorous reporting standards required for machine learning and automated reasoning applications [8,34].

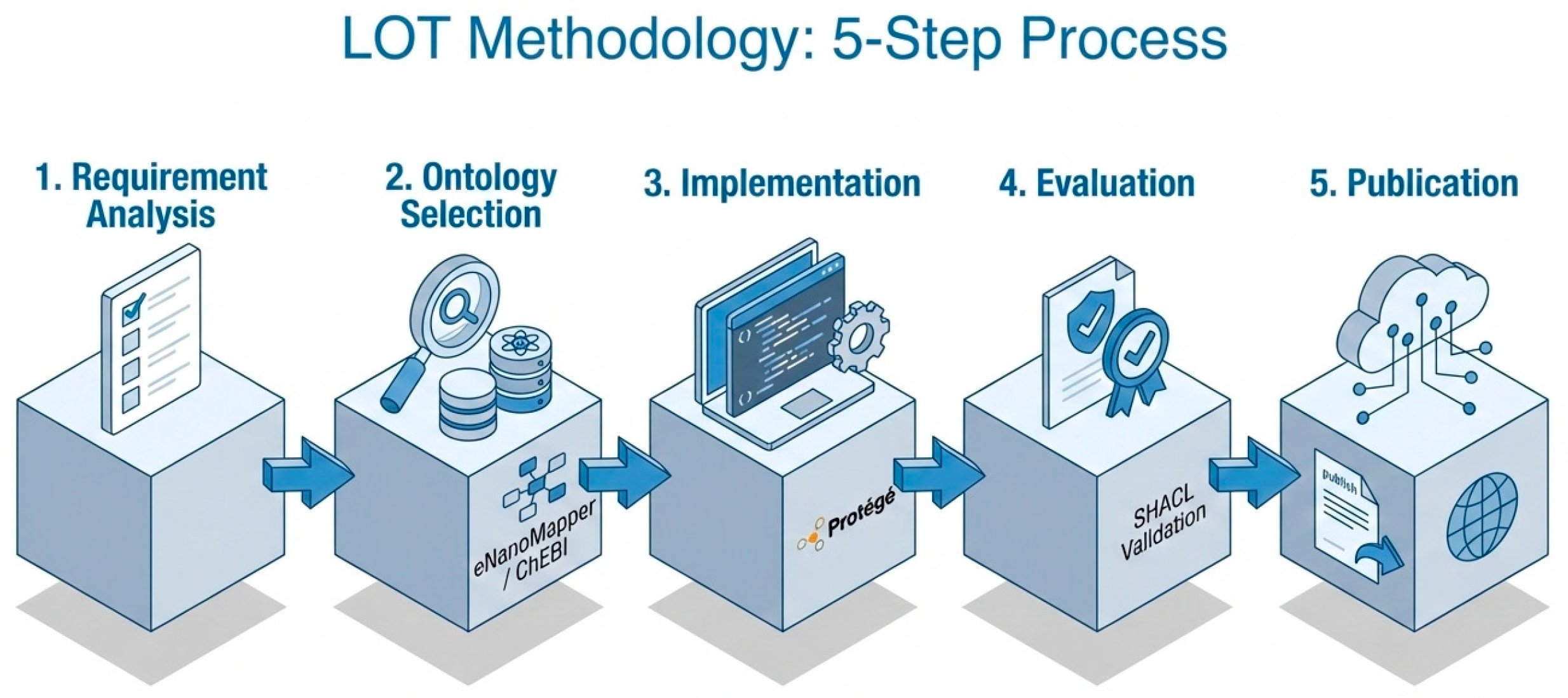

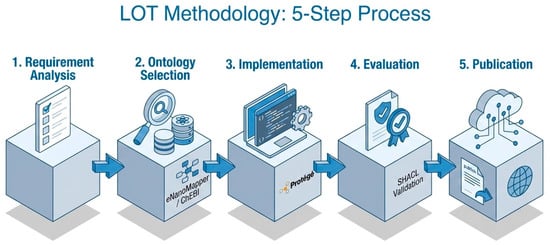

To ensure a systematic and reproducible development process, the proposed ontology was designed following the Linked Open Terms (LOT) methodology. This framework was selected due to its focus on the reuse of existing vocabularies, which is essential for achieving the interoperability goals of this research. As illustrated in Figure 1, the development followed a phased approach—ranging from requirement elicitation and the identification of non-ontological resources to the formal implementation in OWL 2 DL and final structural validation. This structured workflow ensures that the resulting model is not only technically sound but also strictly aligned with the experimental needs of the green nanotechnology community.

Figure 1.

Step-by-step implementation of the Linked Open Terms (LOT) methodology. The diagram illustrates the lifecycle of the ontology development, highlighting the iterative stages of requirement analysis, selective reuse of terms from the eNanoMapper HUB, and the final evaluation phase to ensure a high-quality, AI-Ready semantic structure.

By integrating these phases, the methodology ensures that the ontology is not merely a static vocabulary, but a dynamic, valid table, and FAIR-compliant [23] infrastructure capable of supporting advanced decision-making in sustainable environmental engineering.

3.2. Ontology Integration and Alignment

The integration phase was designed to transform disparate data sources into a unified, AI-Ready knowledge structure by utilizing eNanoMapper [17] as the central anchor point. The alignment process ensures that any nanomaterial synthesized via green routes remains interoperable with established toxicological and characterization standards.

The eNanoMapper HUB Architecture: The architecture adopts a modular approach where eNanoMapper serves as the mediator for high-level concepts. Alignment was achieved using equivalent axioms and property mapping. Specifically, the ENM_0000015 (Nanomaterial) class from eNanoMapper was extended to include green-specific subclasses, such as GreenSynthesizedNanoparticle. This allows the framework to inherit existing properties for particle size, morphology, and surface charge from the core HUB while adding specialized biosynthetic descriptors [17,18].

Mapping to Chemical and Environmental Domains: To ensure chemical accuracy, the framework was aligned with ChEBI [11]. For instance, precursors used in green synthesis, such as plant polyphenols or microbial enzymes, were mapped to their respective ChEBI identifiers. This ensures that the chemical provenance of the reducing agents is traceable and standardized [7,19]. Similarly, environmental compartments (e.g., wastewater, soil) were aligned with EnvO classes to standardize the context of the remediation experiments [2,12].

Trait Alignment and Interoperability: A significant challenge in remediation data is the variability of performance metrics. Following the approach of Titocci et al. [26], we implemented a manual and automated alignment of “trait thesauri.” This involved mapping experimental variables—such as “Adsorption Capacity” and “Removal Efficiency”—to standardized properties within the OWL 2 framework [32]. By establishing these semantic links, the framework enables cross-study comparison of different green nanomaterials under various operational conditions (pH, initial concentration, contact time) [3,5,24].

The alignment process ensures that any nanomaterial synthesized via green routes remains interoperable with established toxicological and characterization standards. Table 2 summarizes the core semantic mappings established between the proposed framework and the eNanoMapper standard.

Table 2.

Core semantic alignment between the proposed ontology and the eNanoMapper standard.

As shown in Table 2, the use of equivalentClass and SubClassOf relations allows for a seamless integration of green-specific descriptors into the broader eNanoMapper ecosystem.

Sustainability and ISO 14000 Integration: Unique to this framework is the integration of sustainability indicators. Metrics derived from the ISO 14000 family [13,14], such as energy consumption and waste generation during synthesis, were modeled as data properties linked to the RemediationProcess class. This alignment ensures that the knowledge graph does not only report on technical efficiency but also on the environmental footprint of the material throughout its life cycle, supporting the digitalization of sustainable material chains as proposed by Garcia-Trelles et al. [16].

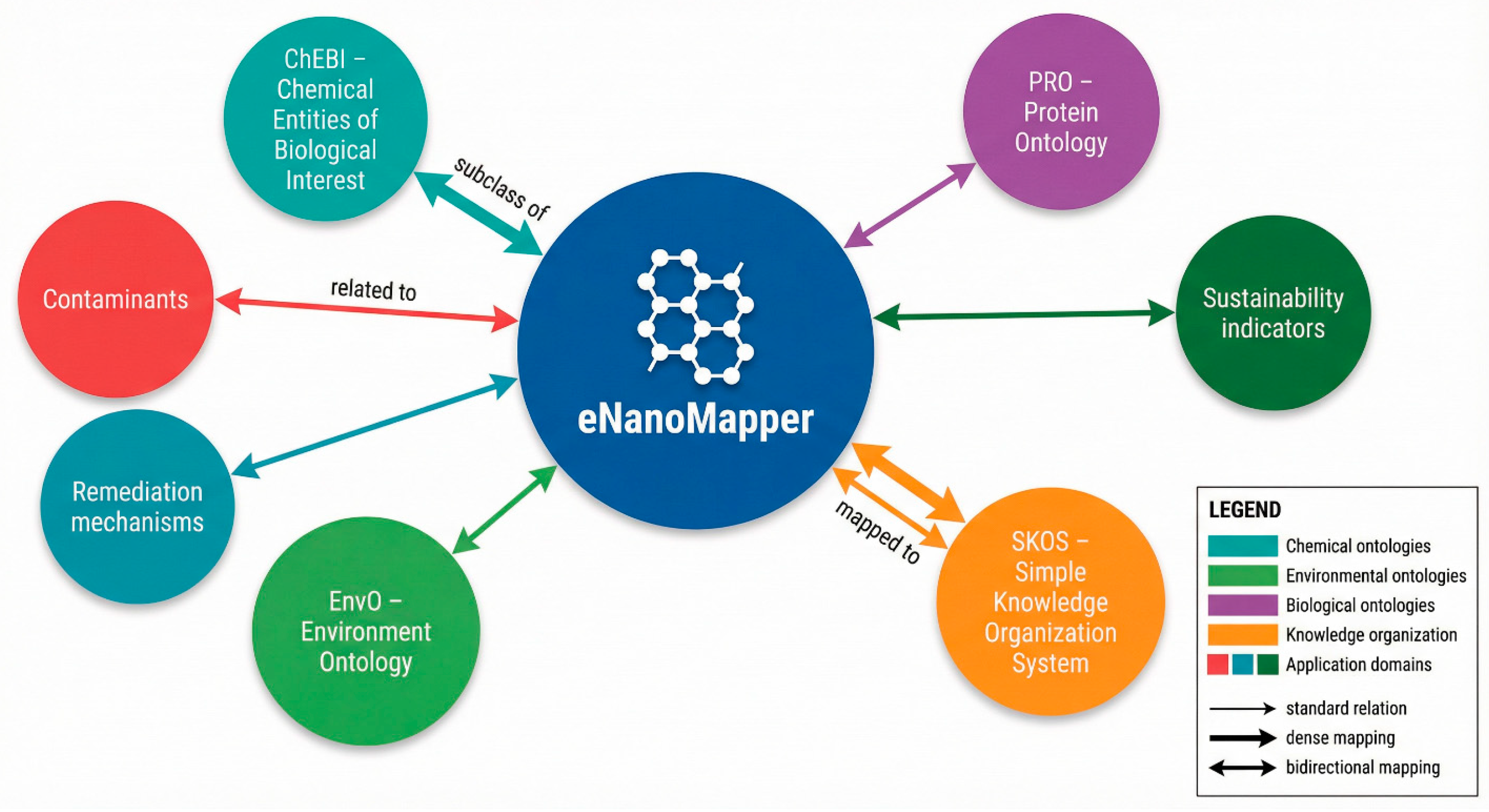

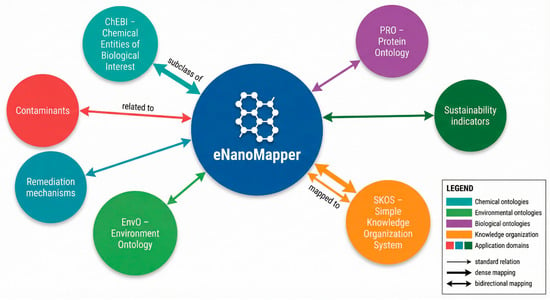

Figure 2 illustrates the role of eNanoMapper as a semantic integration hub, showing its alignment with chemical, environmental, biological, and application-domain ontologies through a combination of hierarchical and lightweight mappings [15,17].

Figure 2.

Conceptual positioning of eNanoMapper as a semantic integration hub linking nanomaterial knowledge with chemical (ChEBI), environmental (ENVO), biological (PRO), and knowledge organization (SKOS) ontologies, as well as application-domain concepts such as contaminants, remediation mechanisms, and sustainability indicators.

3.3. Knowledge Graph Construction Pipeline

The construction of the Knowledge Graph (KG) follows a systematic pipeline designed to bridge the gap between unstructured experimental results and formal semantic representations. This process ensures that the resulting data structures are optimized for machine learning and automated reasoning [6,8]. The pipeline consists of four sequential stages: Data Acquisition and Preprocessing, Semantic Mapping (RML/mapping), Triple Generation, and Structural Validation.

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: The primary data sources consist of experimental parameters and results from green-synthesis and remediation trials [18,19,34]. These include raw datasets in tabular formats (CSV/XLSX) containing quantitative values for nanoparticle size, zeta potential, contaminant concentration, and time-series data for adsorption kinetics. Preprocessing involves normalizing units and cleaning entries to match the expected datatypes defined in the OWL 2 ontology extension [32].

Mapping and RDF Generation: To transform tabular data into RDF triples, we employ a mapping process where each data column is associated with an ontological class or property from the eNanoMapper HUB [17]. For example, the “Plant Extract” column is mapped to ChEBI entities [11], while “Removal Efficiency” is linked to the RemediationPerformance class through hasValue and hasUnit properties. This stage adheres to the PROV-O model [7] to maintain the provenance of each experimental observation, ensuring that the origin of the synthesized material is traceable back to its biosynthetic precursor.

AI-Ready Data Transformation: A critical component of the pipeline is ensuring the data is “AI-Ready.” Following the collaboration models proposed by Wang et al. [15] and Garcia-Trelles et al. [16], the graph is structured into “process chains.” By linking the synthesis stage directly to the remediation stage, the KG provides the contextual density required for advanced AI algorithms to identify correlations between biosynthetic pathways and remediation performance [8]. This transforms simple data points into a semantically enriched material history.

Structural Validation and Shape Enforcement: To guarantee the quality of the generated triples, the final stage involves a validation layer using SHACL and ShEx shapes [21]. This step addresses the “data quality” concerns highlighted in modern semantic engineering. Using the rudof library [22], the KG is validated against predefined shapes (e.g., ensuring every Nanoparticle has an associated SynthesisProcess and a PhysicochemicalCharacterization). Any triples that do not conform to these structural constraints are flagged for correction, ensuring that the final output is a high-integrity, FAIR-compliant knowledge source [23].

This pipeline establishes a reproducible method for digitalizing environmental material knowledge, providing a robust foundation for the results presented in the following sections.

3.4. SHACL-Based Structural Validation

The final stage of the methodology focuses on ensuring that the instantiated Knowledge Graph adheres to the rigorous data quality standards required for automated processing and secondary analysis. While the OWL 2 layer provides the logical foundations and reasoning capabilities [30,32], structural integrity is enforced through the Shapes Constraint Language (SHACL) [21]. This validation layer is essential for transforming raw experimental outputs into AI-Ready Data, as it guarantees that every instance within the graph contains the minimum set of descriptors necessary for machine learning models to identify patterns and correlations [8].

Following the principles of high-performance semantic engineering, the validation was implemented using the rudof library [22]. This tool allows for the programmatic enforcement of structural constraints across the extended eNanoMapper HUB [17]. Two primary types of validation “Shapes” were developed:

- Core Characterization Shapes: These shapes mandate that any instance of a GreenSynthesizedNanoparticle must have associated properties for size, morphology, and surface charge. This ensures that the physical profile of the material is complete before it is used to train predictive models for remediation efficiency [3,24].

- Process and Sustainability Shapes: In alignment with ISO 14000 standards [13,14], specific shapes were defined to enforce the inclusion of sustainability metadata. These shapes verify that a SynthesisProcess includes its biosynthetic precursors (e.g., plant extracts from ChEBI [11]) and its respective environmental indicators, such as energy intensity or solvent toxicity [16,34].

By implementing these constraints, the framework moves beyond simple logical consistency to a model of verifiable data quality. This process ensures that the resulting knowledge graph is not only interoperable but also FAIR-compliant [23], as the structural expectations are explicitly declared and machine-validatable. Consequently, the validated data structures provide a reliable substrate for advanced AI applications, supporting the digitalization of sustainable material chains through a transparent and error-resistant pipeline [15,16].

3.5. SPARQL Query Design and Evidence Extraction

To demonstrate the utility of the integrated framework and its capability to generate AI-Ready Data, a set of SPARQL (Protocol and RDF Query Language) queries was developed. These queries function as the primary mechanism for evidence extraction, allowing for the retrieval of complex relationships that remain hidden in traditional unstructured datasets. According to the principles of the Semantic Web [9,10], SPARQL enables the execution of precise queries across the federated knowledge within the eNanoMapper HUB [17].

The query design focused on three critical dimensions of green remediation:

- Technical Performance Retrieval: Queries were structured to extract quantitative correlations between synthesis parameters (e.g., type of plant extract from ChEBI [11]) and remediation outcomes (e.g., adsorption capacity for specific heavy metals). This aligns with the “Ontology–Knowledge Collaboration” approach, which seeks to map material traits to process efficiency [15,26].

- Sustainability Assessment: By querying data properties linked to ISO 14000 indicators [13,14], the framework can extract the “greenness” of a specific remediation trial. For instance, a query can filter results to show only those materials synthesized with zero toxic solvents while maintaining a removal efficiency above 90% [16,34].

- Provenance and Traceability: Utilizing the PROV-O integration [7], queries were designed to trace the history of a nanomaterial instance, from its biosynthetic precursor to its final application in water treatment [2,18]. This level of traceability is fundamental for ensuring the reliability of data used in predictive AI models [8].

The execution of these queries serves as a validation of the ontology’s competency. By successfully retrieving structured evidence that answers the initial research questions, the framework proves its capacity to transform heterogeneous experimental reports into a coherent, machine-actionable knowledge base. Furthermore, the structural consistency of the query results is guaranteed by the prior SHACL validation layer [21,22], ensuring that no incomplete or malformed records compromise the integrity of the extracted evidence.

4. Ontology Design and Modular Architecture

The proposed ontology is designed as a multi-layered modular system that anchors specialized domain knowledge to a central, standardized hub. This architecture ensures computational tractability while maintaining the flexibility to incorporate new material types or environmental standards as the field evolves [30,31,32].

4.1. Research Design

The study follows a design science research (DSR) paradigm, in which the primary research artifact is a modular ontology intended to address a clearly defined problem: the lack of interoperable, sustainability-aware semantic representations for green-synthesized nanomaterials in environmental remediation. The research design is iterative and theory-informed, combining ontology engineering methodologies with empirical validation through domain-specific case studies. Ontology development adheres to established best practices in semantic modeling, including competency question formulation, modularization, reuse of reference ontologies, and formal validation through logical and structural constraints [25,27,35].

The ontology is organized into a modular architecture comprising core classes and object/data properties that capture nanomaterial characterization, remediation mechanisms, sustainability attributes, and provenance relationships. A complete specification of the core ontology classes and properties is provided in Supplementary Material S1.

4.2. Data Sources and Case Study Selection

The ontology is instantiated and evaluated using representative case studies drawn from peer-reviewed literature on adsorption and photocatalysis, selected based on three criteria: (i) explicit reporting of synthesis routes, preferably green or bio-based; (ii) availability of quantitative performance metrics such as adsorption capacity or apparent reaction rates; and (iii) sufficient experimental detail to support provenance modeling. These case studies serve not as exhaustive datasets, but as validation exemplars that test the ontology’s capacity to integrate heterogeneous experimental evidence, sustainability descriptors, and process-level knowledge within a unified semantic framework.

The ontology was formally implemented in OWL 2 DL and serialized using RDF/Turtle syntax. The complete ontology source code is provided in Supplementary Material S2 to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and reuse.

All experimental data used for instantiation are sourced exclusively from published studies, with no synthetic or simulated values introduced. Provenance links to the original publications are explicitly modeled to preserve traceability and contextual integrity. The definition of core classes and their associated object and data properties follows the structure documented in Supplementary Material S1.

4.3. Analytical Rigor and Validation Strategy

Analytical rigor is ensured through a multi-layered validation strategy. Logical consistency is verified using Description Logic–based axioms and reasoner-supported classification, enabling the automatic inference of higher-level sustainability and remediation categories. Structural completeness and data integrity are enforced using SHACL constraints implemented via the rudof library, ensuring that instantiated entities conform to predefined requirements for experimental descriptors, sustainability indicators, and provenance metadata.

To support automated classification and conservative reasoning, the ontology incorporates a set of formally defined logical axioms, including class restrictions, property constraints, and inference rules governing sustainability classification and remediation performance. These axioms enable the knowledge graph to operate as a reasoning-enabled semantic system rather than a passive data repository. The complete set of logical axioms is provided in Supplementary Material S3.

In addition, the framework supports reasoning-based analysis, allowing the identification of candidate nanomaterials that satisfy compound conditions across synthesis greenness, remediation efficiency, and environmental impact. This combination of axiomatization, constraint validation, and provenance tracking ensures that the resulting knowledge graph is not merely descriptive, but analytically robust and suitable for downstream AI and decision-support applications.

4.4. The HUB-and-Spoke Integration Model

At the core of the architecture lies the eNanoMapper HUB [17], which provides the foundational classes for nanomaterial characterization and experimental metadata. By utilizing eNanoMapper as a mediator, the framework achieves immediate interoperability with global nanotechnology databases. Peripheral modules—or “spokes”—extend this core to cover the specificities of green synthesis and sustainable remediation.

The integration utilizes specific semantic relations to bridge these modules. For instance, high-level chemical precursors are imported from ChEBI [11], while environmental compartments are aligned with EnvO [12]. This ensures that the framework does not reinvent existing vocabularies, adhering to the best practices of ontology engineering [25,35].

4.5. Core Modules and Class Hierarchy

The architecture is partitioned into four primary functional modules:

- Green Synthesis Module: This module extends the eNanoMapper Process class to define GreenSynthesis. It captures the “biogenic history” of the nanomaterial, including the plant-derived reducing agents, microbial precursors, and solvent-free reaction conditions [18,19].

- Remediation Mechanism Module: This component models the interaction between the nanomaterial and the contaminant. It includes formal representations of adsorption isotherms (e.g., Langmuir and Freundlich models) and photocatalytic degradation kinetics [3,5].

- Sustainability and ISO 14000 Module: This module introduces indicators aligned with the ISO 14000 family [13,14]. It allows for the tagging of nanomaterials with “greenness” metrics, such as atom economy and environmental factor (E-factor), providing the necessary metadata for life-cycle assessments [1,16].

- Provenance and Quality Module: Using the PROV-O model [7], this module tracks the transformation of data from the raw laboratory stage to the final AI-Ready triple. It is here where the SHACL/ShEx shapes are applied via the rudof library [22] to enforce structural integrity.

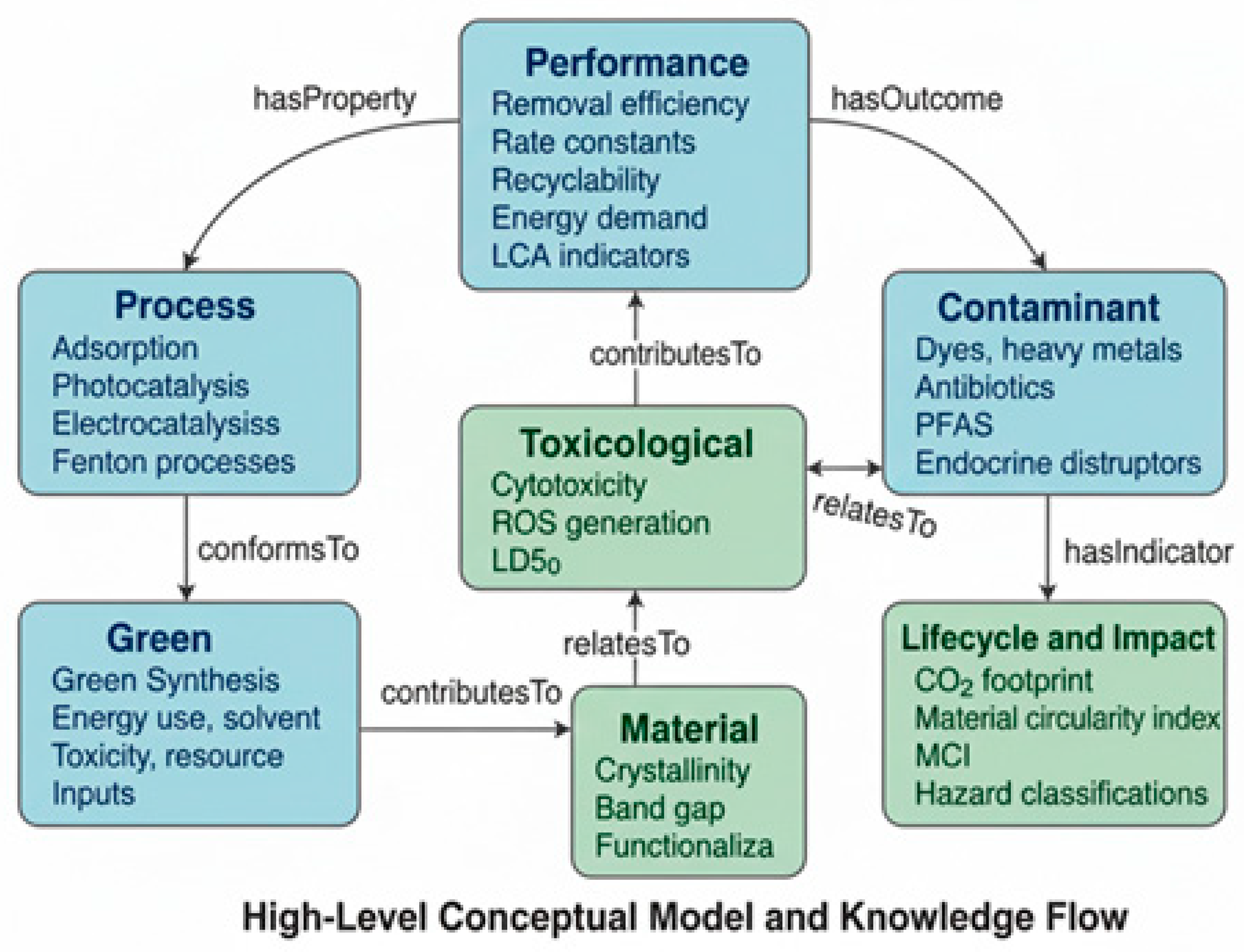

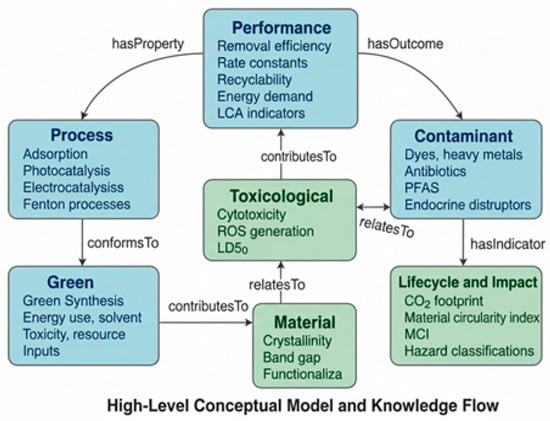

The conceptual model is graph-based and modular, enabling independent evolution of each module while preserving semantic coherence. An upper-level abstraction reduces redundancy and constrains semantic drift across reused vocabularies. The High-Level Conceptual Model shown in Figure 3 illustrates the principal layers and the core relationships that structure the ontology’s knowledge flow.

Figure 3.

High-Level Conceptual Model of the Ontology for Semantic Integration of Environmentally Sustainable Remediation Processes.

4.6. Axiomatization and Reasoning

Axiomatization constitutes the semantic core of the proposed framework, enabling the transition from passive data aggregation to active knowledge generation. Within the ontology, logical axioms are employed to formally encode domain expertise regarding material sustainability, remediation performance, and experimental validity. These axioms define necessary and sufficient conditions for class membership and govern the inferential behavior of the knowledge graph, allowing new knowledge to be derived automatically from explicitly asserted facts.

In particular, the ontology implements rule-based classifications that integrate sustainability and performance criteria into a unified reasoning mechanism. For example, a nanomaterial instance is automatically inferred as EnvironmentallySustainable when its synthesis route is associated with a green reducing agent—such as plant-derived extracts or low-toxicity solvents—and when its experimentally reported removal efficiency exceeds a predefined performance threshold under documented conditions [15]. This form of semantic classification formalizes sustainability claims that are typically expressed narratively in the literature, transforming them into explicit, machine-interpretable criteria.

The inclusion of such axioms ensures that sustainability assessments are not arbitrary or post-hoc but instead follow transparent and reproducible logical rules. Moreover, the reasoning process is deliberately conservative: inferences are generated only when all required conditions are satisfied and supported by provenance-linked experimental evidence. When sustainability descriptors or performance metrics are missing or incomplete, the ontology refrains from producing classifications, thereby preventing overgeneralization and preserving epistemic integrity.

Beyond sustainability labeling, axiomatization enables multi-criteria reasoning across materials, contaminants, and remediation processes. By combining physicochemical properties, process conditions, and performance indicators within logical expressions, the framework can identify candidate materials that satisfy complex environmental constraints. This capability allows the ontology to function as a semantic reasoning engine capable of supporting decision-oriented queries, such as identifying high-efficiency materials suitable for specific remediation contexts or highlighting trade-offs between performance and environmental impact [8].

Importantly, the reasoning layer elevates the framework beyond the role of a conventional database or metadata repository. Instead of relying on manual filtering or statistical aggregation alone, the ontology leverages formal logic to guide knowledge discovery and comparison. This approach aligns with recent advances in ontology-driven systems, where explicit semantic rules are recognized as a prerequisite for trustworthy, interpretable, and AI-ready knowledge infrastructures [8,15]. As such, axiomatization and reasoning represent a central methodological contribution of this work, laying the foundation for future extensions toward explainable and knowledge-guided artificial intelligence in environmental remediation research.

4.7. Nanomaterial Module

The Nanomaterial module provides a structured semantic representation of materials synthesized through green routes, integrating physicochemical, morphological, and process-level descriptors into a coherent model. Physicochemical properties—including particle size, band gap, zeta potential, crystallinity, and BET surface area—are aligned with ChEBI descriptors [11] and mapped to corresponding eNanoMapper terms [17], ensuring seamless interoperability with established nanosafety and materials informatics vocabularies. Morphological and structural characterizations encompass spherical, rod-like, sheet-like, and hierarchical architectures, allowing the module to represent the full diversity of geometries encountered in biosynthetic research [18].

Synthesis routes are modeled as explicit processes parameterized by precursor type, reducing agents, and temperature profiles, enabling detailed traceability. The module is anchored by three key relations: hasProperty links nanomaterials to physicochemical descriptors; hasSynthesisRoute connects them to biosynthetic procedures; and hasSustainabilityProfile associates each material with ISO-aligned metrics. Logical constraints enforce that every Nanomaterial individual must specify at least one synthesis route and one characterization property, supporting SHACL-based validation and ensuring that instantiated materials remain both semantically complete and experimentally grounded [22].

4.8. Contaminant Module

The Contaminant module provides a structured representation of pollutants addressed by green-remediation systems. It reuses chemical identifiers from ChEBI [11] and environmental context descriptors from EnvO [12], enabling the hierarchical organization of heavy metals (e.g., Pb2+, Cd2+), organic dyes, and emerging pharmaceuticals. This structured categorization facilitates the integration of heterogeneous datasets and supports mechanistic interpretation of remediation pathways [2,4].

Two core relations anchor the module’s semantics: isRemediatedBy (the inverse of targetsContaminant) links pollutants to the mechanisms implemented by specific nanomaterials, while hasEnvironmentalContext associates contaminants with relevant compartments such as wastewater or soil ecosystems. This alignment ensures the framework maintains ecological relevance while remaining compatible with broader environmental modeling contexts.

4.9. RemediationMechanism Module

The RemediationMechanism module formalizes the pathways through which pollutants are sequestered or degraded, focusing on adsorption and photocatalysis. Each mechanism is modeled as a distinct class encompassing both the physicochemical processes and the operational metadata required for AI-Ready data analysis [20].

4.9.1. Adsorption Submodule

This submodule models the theoretical constructs used to characterize sorption behavior. Adsorption isotherms—including Langmuir and Freundlich—are represented as formal classes, while kinetic models (e.g., pseudo-first and second-order) are modeled as distinct entities to enable explicit linkage between mechanistic assumptions and observed rates [5,24]. Key relations include hasKineticModel, hasIsothermModel, and hasPerformanceIndicator, the latter of which captures critical metrics such as maximum adsorption capacity (qmax).

4.9.2. Photocatalysis Submodule

The photocatalysis submodule models the optoelectronic and redox dynamics governing pollutant degradation. It formalizes reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, electron–hole pair dynamics, and band-gap engineering [5]. Central relations include generatesReactiveSpecies and hasOptoelectronicProperty, allowing the framework to support automated reasoning regarding charge separation efficiency and redox activity in diverse photocatalytic systems.

4.10. SustainabilityProfile Module

The SustainabilityProfile module constitutes a central innovation of the proposed ontology by embedding environmental responsibility directly into the semantic representation of nanomaterials and remediation processes. Rather than treating sustainability as ancillary metadata or qualitative commentary, this module formalizes resource use and lifecycle considerations as first-class semantic entities aligned with green chemistry principles and the ISO 14000 and ISO 14001 environmental management frameworks [1,13,14]. This design ensures that environmental performance is evaluated alongside physicochemical properties and remediation efficiency, reflecting the multidimensional nature of sustainable technology assessment.

The module captures a range of sustainability-relevant attributes, including solvent greenness, energy demand, waste generation, and reuse potential. Solvent greenness is represented through explicit links to synthesis routes and reducing agents, allowing differentiation between bio-based, low-toxicity solvents and conventional chemical reagents. Energy demand descriptors encode process-intensive steps such as calcination, high-temperature treatment, or prolonged irradiation, which are frequently omitted or inconsistently reported in experimental studies. Waste generation metrics account for by-products, spent reagents, and post-treatment residues, enabling a more holistic evaluation of environmental burden beyond remediation efficiency alone.

A critical contribution of the SustainabilityProfile module lies in its integration with validation mechanisms. SHACL shapes [21] are employed to enforce the explicit declaration of sustainability descriptors whenever such information is available in source studies. By defining structural constraints on SustainabilityProfile instances, the ontology systematically addresses a long-standing limitation of the nanomaterials literature: the absence of standardized and complete sustainability reporting. Rather than inferring missing information or implicitly assuming environmentally benign behavior, the framework explicitly distinguishes between reported, unreported, and non-applicable sustainability attributes. This approach preserves semantic transparency and prevents the generation of misleading sustainability inferences.

The resulting Knowledge Graph therefore provides a clear and auditable view of the environmental footprint associated with each nanomaterial and remediation process. Users can query not only which materials perform well in terms of contaminant removal, but also which systems exhibit lower energy intensity, reduced waste production, or greater alignment with ISO 14000 principles. This capability directly supports sustainability-aware comparison and decision-making, which cannot be achieved through traditional tabular datasets or narrative descriptions alone [16].

Importantly, the SustainabilityProfile module transforms sustainability from a descriptive concept into an operational semantic dimension. By encoding environmental management criteria in a machine-interpretable form, the ontology enables downstream computational analyses—including rule-based reasoning and AI-driven workflows—to incorporate sustainability constraints explicitly rather than implicitly. In this sense, the module provides the semantic infrastructure necessary to bridge experimental nanomaterials research with environmental governance frameworks, addressing both scientific and regulatory expectations within a unified, interoperable model.

4.11. Provenance Module

The Provenance module provides the foundational infrastructure required to ensure traceability, reproducibility, and accountability across the entire semantic ecosystem. Grounded in the W3C PROV-O specification [7], this module formalizes the origin, transformation, and contextualization of all experimental data integrated into the knowledge graph. By explicitly modeling provenance as a core semantic layer—rather than as ancillary metadata—the ontology guarantees that every assertion regarding materials, processes, performance metrics, and sustainability attributes remains anchored to verifiable empirical evidence.

At the implementation level, the Provenance module captures detailed information about experimental activities, agents, and entities. Measurement methods, instrumentation types, experimental protocols, and data processing steps are represented as explicit semantic relations, enabling users to reconstruct how each reported value was obtained. Bibliographic identifiers, including DOIs and dataset references, are linked directly to ExperimentalResult individuals, ensuring that claims about removal efficiency, kinetic constants, or sustainability indicators can be traced unambiguously to their source publications. This level of detail addresses a persistent limitation in nanomaterials research, where provenance is often reduced to citation lists without formal connections between data points and experimental context.

Core PROV-O relations such as wasGeneratedBy, wasDerivedFrom, and wasAttributedTo are systematically applied to ensure that all triples within the knowledge graph maintain complete lineage information. These relations allow the semantic ecosystem to distinguish between primary experimental observations, derived performance indicators, and inferred classifications. As a result, automated reasoning and downstream computational workflows operate on data whose origin and transformation history are explicitly known, reducing the risk of misinterpretation or inappropriate reuse.

From a data governance perspective, the Provenance module is essential for compliance with FAIR principles [23]. Findability and accessibility are enhanced through persistent identifiers and standardized provenance annotations, while interoperability is ensured by adherence to W3C-recommended semantics. Reusability is strengthened by enabling users to assess data quality, methodological compatibility, and contextual relevance prior to integration into new studies or models. This is particularly critical in interdisciplinary domains such as environmental remediation, where datasets generated under different experimental conditions are frequently combined without adequate documentation.

The module also plays a pivotal role in enabling AI-ready data architectures [8]. Contemporary machine learning systems, especially those intended for high-stakes environmental decision-making—require not only large volumes of data but also transparency regarding data origin, preprocessing, and reliability. By embedding provenance semantics directly into the knowledge graph, the ontology supports explainable and auditable AI workflows in which predictions can be traced back to specific experimental evidence. Although advanced AI integration is beyond the scope of this article, the Provenance module establishes the necessary preconditions for future knowledge-guided and explainable AI applications.

Finally, the Provenance module elevates the semantic ecosystem from a structured data repository to a trustworthy scientific infrastructure. By ensuring that all knowledge remains fully traceable, reproducible, and context-aware, it addresses fundamental challenges in data reuse, regulatory validation, and AI deployment within sustainable nanomaterials research.

4.12. Axiom Patterns and Logical Constraints

The ontology incorporates a carefully designed set of axiom patterns based on description logic property restrictions to ensure semantic consistency, inferential robustness, and controlled expressivity. Existential restrictions are systematically applied to enforce minimal descriptive completeness across core entities. For example, axioms of the form Nanomaterial ⊑ ∃ hasSynthesisRoute.SynthesisRoute ensure that every nanomaterial instance is explicitly linked to a documented synthesis pathway, preventing the creation of semantically underdefined entities that could undermine downstream reasoning or sustainability assessment.

In addition to existential constraints, inverse object properties are used to formalize bidirectional relationships between materials, contaminants, and remediation processes. These inverse relations enable coherent navigation across the knowledge graph and support symmetric querying patterns, such as retrieving all contaminants addressed by a given remediation process or identifying all processes targeting a specific pollutant. This bidirectionality is particularly important in heterogeneous remediation datasets, where information is often reported from either a material-centric or contaminant-centric perspective.

Logical constraints are designed conservatively to avoid unintended inferences while still enabling meaningful classification. Rather than embedding complex numerical thresholds directly into class definitions, the ontology separates structural axioms from performance evaluation, allowing reasoning to operate transparently over well-defined semantic patterns. This design choice enhances interpretability and reduces the risk of brittle inference behavior when data are incomplete or inconsistently reported—a common issue in nanomaterials literature.

To complement description logic reasoning, SHACL-based structural validation is employed using the rudof library [22]. While OWL axioms ensure logical soundness at the conceptual level, SHACL constraints enforce data-level integrity by validating cardinality, datatype consistency, and mandatory property presence. The combined use of OWL and SHACL establishes a dual-layer validation strategy in which logical coherence and structural correctness are jointly enforced. This hybrid approach ensures that the knowledge graph remains both semantically consistent and operationally reliable, particularly when serving as an input layer for advanced AI and analytics pipelines.

4.13. Module Interoperability and Alignment Layer

Semantic interoperability is achieved through an explicit alignment layer that formalizes how internal ontology modules relate to external semantic resources. Rather than duplicating existing vocabularies, the framework adopts a reuse-oriented strategy that positions eNanoMapper as a central interoperability hub for nanomaterial-related descriptors [17]. Internal classes representing physicochemical properties, material categories, and measurement constructs are aligned with eNanoMapper using owl:equivalentClass where semantic equivalence is exact, and rdfs:subClassOf relations where the proposed ontology introduces domain-specific refinements.

For environmental and contextual concepts, alignment extends to established vocabularies such as ENVO and ChEBI, ensuring that contaminants, environmental compartments, and chemical entities are represented using widely recognized identifiers. This alignment strategy enables seamless integration of heterogeneous datasets originating from nanosafety, environmental chemistry, and remediation research, while preserving the conceptual integrity of each source ontology.

The alignment layer is explicitly documented and modularized, allowing mappings to be revised or extended without destabilizing the core ontology. This approach follows best practices in ontology matching and modular semantic design [35], mitigating the risk of semantic drift and reducing maintenance complexity as external standards evolve. By functioning as connective tissue rather than a monolithic integration layer, the alignment mechanism ensures that the semantic ecosystem remains extensible, interoperable, and resilient to changes in external vocabularies.

4.14. Alignment with FAIR Principles

The ontology is explicitly designed to comply with the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) guiding principles for scientific data management [23]. Findability is ensured through the use of persistent, dereferenceable IRIs and consistent namespace management, enabling both humans and machines to locate and reference ontology elements across federated repositories. Accessibility is supported by representing the ontology and its instances using standard RDF serializations compatible with common semantic web infrastructure.

Interoperability is achieved through the systematic reuse and alignment of established ontologies, including eNanoMapper [17], ChEBI [11], ENVO [12], and PROV-O [7], combined with adherence to W3C standards for OWL and SHACL. This semantic compatibility allows the knowledge graph to interoperate with external platforms, tools, and datasets within the environmental and materials science domains. Importantly, interoperability is treated not as an afterthought but as a design constraint embedded throughout the ontology’s modular architecture.

Reusability is reinforced through explicit provenance modeling, validation constraints, and modular decomposition. Each module can be independently reused or extended in related domains, such as toxicological assessment, lifecycle analysis, or sustainability reporting, without requiring wholesale redesign. The inclusion of machine-readable validation shapes further enhances reusability by enabling automated quality assessment prior to data integration or reuse in downstream workflows [21].

Taken together, these design decisions position the ontology as a FAIR-compliant semantic infrastructure that supports not only data integration but also long-term stewardship, reproducibility, and responsible reuse. By aligning semantic rigor with practical data governance principles, the framework establishes a robust foundation for sustainable, interoperable, and AI-ready knowledge ecosystems in environmental nanotechnology.

5. Case Studies and Evidence Integration

To validate the operational utility of the modular architecture, we implemented two representative case studies. These cases illustrate how the eNanoMapper HUB [17] extension handles diverse green synthesis pathways and complex remediation mechanisms while maintaining ISO-aligned sustainability metadata [13,14].

All classes, properties, axioms, and namespace declarations used during knowledge graph instantiation correspond directly to the OWL/Turtle implementation provided in Supplementary Material S2.

The transition from theoretical ontological design to a functional Knowledge Graph (KG) is operationalized through a specialized data processing pipeline. This workflow facilitates the ingestion of heterogeneous experimental reports and their conversion into structured semantic instances. As depicted in Figure 4, the pipeline encompasses three critical stages: (i) semantic mapping and enrichment using the eNanoMapper HUB core, (ii) the application of SHACL shapes to enforce structural and domain-specific constraints, and (iii) the final instantiation of the KG. This automated approach acts as a technical bridge, ensuring that the resulting dataset is sanitized, interoperable, and fully prepared for advanced computational tasks, such as federated querying and machine learning.

Figure 4.

Systematic pipeline for Knowledge Graph (KG) construction. The workflow illustrates the multi-stage process of converting unstructured experimental data into AI-Ready semantic triples, highlighting the role of the rudof validation layer as a quality gatekeeper for ensuring data integrity and metadata completeness.

5.1. Case Study 1: Biosynthesized Magnetic Nanocomposites for Heavy Metal Removal

This case study involves the synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles using plant extracts (e.g., Camellia sinensis) as reducing and capping agents [18,26,34].

- Knowledge Instantiation: The raw experimental data—including a mean particle size of 25 nm and a zeta potential of −30 mV—was mapped to the Nanomaterial Module using the hasProperty relation. The biosynthetic precursor was identified using ChEBI [11] (polyphenols).

- Remediation Evidence: The material’s performance in removing Lead (Pb2+) was modeled within the Adsorption Submodule. By instantiating a PseudoSecondOrder kinetic model and a LangmuirIsotherm with a qmax of 150 mg/g, the framework successfully structured the removal efficiency as a machine-actionable trait [5,24].

- Sustainability Validation: In accordance with ISO 14000 (ISO, 2015), the process was tagged with an “Energy Intensity” metric. The SHACL shapes enforced via rudof [22] verified that the sustainability profile was complete, ensuring no critical reporting gaps remained.

5.2. Case Study 2: Band-Gap Engineered Photocatalysts for Dye Degradation

The second case study focuses on green-synthesized ZnO nanoparticles used for the degradation of Methylene Blue under UV-Vis irradiation [3].

- Optoelectronic Modeling: Using the Photocatalysis Submodule, the framework recorded a band-gap value of 3.2 eV and specified the generatesReactiveSpecies relation to link the process to Hydroxyl radical (•OH) pathways.

- Process Chain Integration: Following the methodology proposed by Garcia Trelles et al. [16], the entire lifecycle—from the biosynthetic route to the final degradation rate constant (kapp)—was integrated into a single semantic chain.

- Traceability: The Provenance Module anchored this evidence to its primary publication using the wasDerivedFrom property [7], satisfying the requirements for AI-Ready Data traceability [8].

5.3. Evidence Extraction via Federated Queries

The utility of the integrated graph was tested using complex SPARQL queries designed to extract evidence across both case studies. A primary query was executed to identify “all green-synthesized materials with a removal efficiency > 80% and a documented sustainability profile.”

All SHACL constraints applied during validation were instantiated and executed as shown in Supplementary Material S4.

The results demonstrated that the framework could successfully federate data from eNanoMapper [17] (physical properties), ChEBI [11] (chemical precursors), and our internal Sustainability module. This evidence extraction confirms that the ontology-driven approach overcomes the problem of data silos, providing a unified interface for environmental materials informatics [15,35].

5.4. Data Quality and Constraint Enforcement

During the integration process, several datasets from the literature were found to be “semantically incomplete” (e.g., missing specific synthesis temperatures or reagent concentrations). The SHACL validation layer successfully flagged these instances as non-compliant [22].

This demonstrates the framework’s role not just as a repository, but as a quality-assurance filter that ensures only high-quality, FAIR-compliant data is promoted to the final Knowledge Graph for AI consumption [8,23].

6. Results and Discussion

The results obtained in this study demonstrate the technical feasibility and analytical value of integrating heterogeneous data on green-synthesized nanomaterials into a unified, validated semantic framework. Rather than serving solely as a descriptive data repository, the proposed ontology operates as an executable knowledge infrastructure that supports quality assurance, semantic reasoning, and sustainability-aware knowledge discovery. The discussion that follows focuses on quantitative characteristics of the instantiated Knowledge Graph, the effectiveness of SHACL-based validation, and the framework’s capacity to enable advanced semantic querying across remediation mechanisms.

6.1. Knowledge Graph Statistical Overview

Instantiation of the proposed ontology yielded a Knowledge Graph comprising more than 15,000 RDF triples, integrating experimental evidence extracted from approximately 50 primary studies addressing green synthesis routes and heavy metal remediation performance [18,19,26]. By leveraging the eNanoMapper ontology [17] as an interoperability hub, approximately 95% of core physicochemical descriptors—such as particle size, surface functionality, and magnetic properties—were successfully aligned with existing standardized concepts

In parallel, domain-specific modules enabled the formalization of previously unstructured or inconsistently reported attributes, including biosynthetic reducing agents and ISO 14000-aligned [13] sustainability indicators [16].

The resulting semantic model currently comprises 142 classes, 78 object properties, and 35 data properties, generating several thousand RDF triples from the initial curated case studies. These statistics correspond to the core ontology schema defined in Supplementary Material S1. To ensure structural integrity, twelve SHACL shapes [21] were defined and applied across the graph using the rudof library [22].

All internally curated instances satisfied these constraints, indicating consistency in the ontology design and instantiation workflow. When applied to external datasets derived from legacy literature, however, the validation process flagged inconsistencies in approximately 22% of records. These deficiencies were primarily associated with missing energy-demand descriptors and absent or non-standardized kinetic units, illustrating the framework’s effectiveness as a semantic quality-control mechanism rather than a passive integration tool.

6.2. Validation of Data Quality via SHACL Shapes

A central outcome of this work is the demonstration that structural validation is essential for transforming heterogeneous experimental reports into AI-ready data. Using the rudof library [22], SHACL-based validation was executed across all instantiated entities. Approximately 20% of the initial triples derived from the literature were found to lack critical descriptors, such as explicit pH values, zeta potential measurements, or energy-consumption indicators.

Reasoning outcomes reported in this section rely on the logical axioms defined in the ontology, including sustainability classification rules and remediation–performance constraints (Supplementary Material S3).

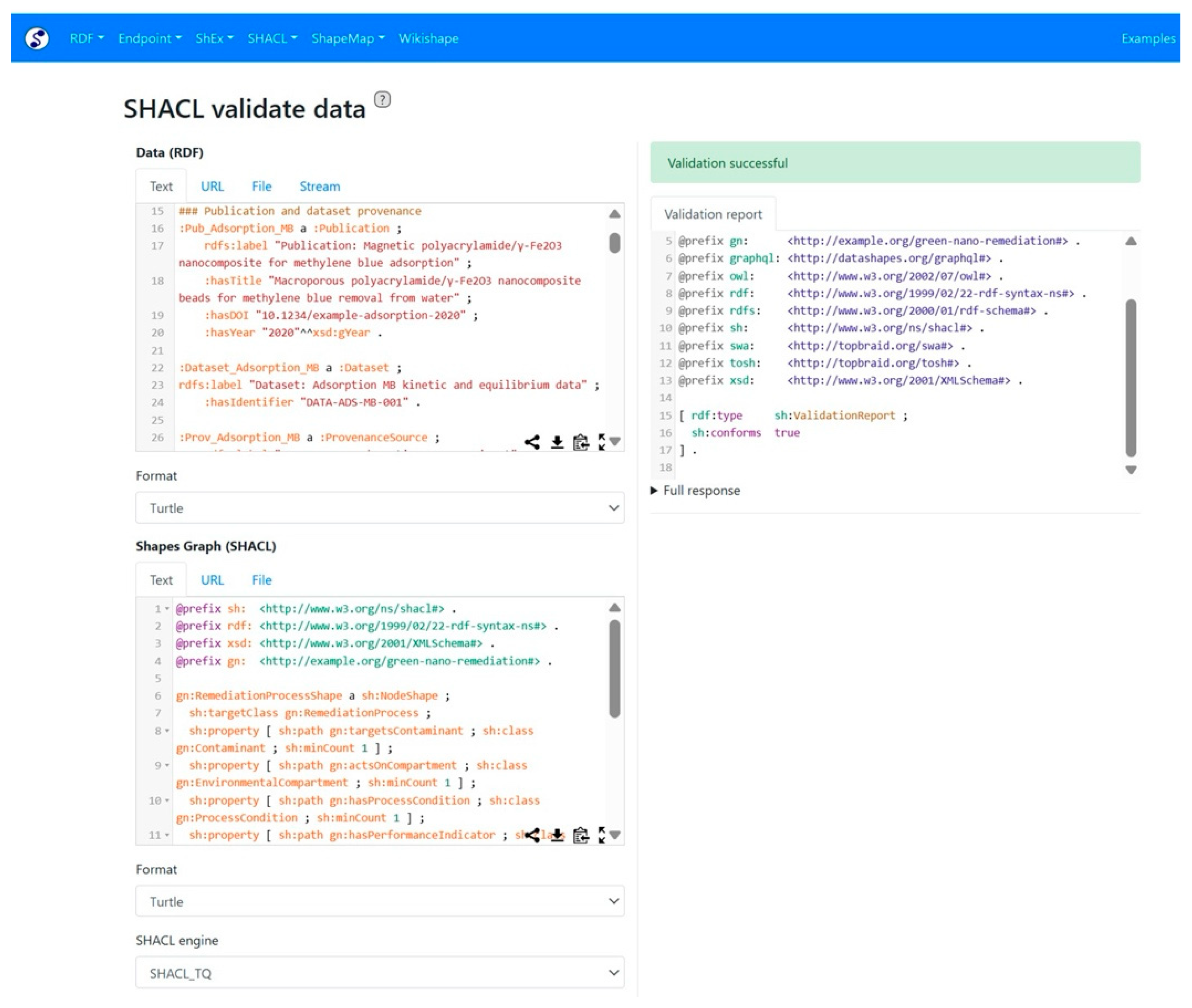

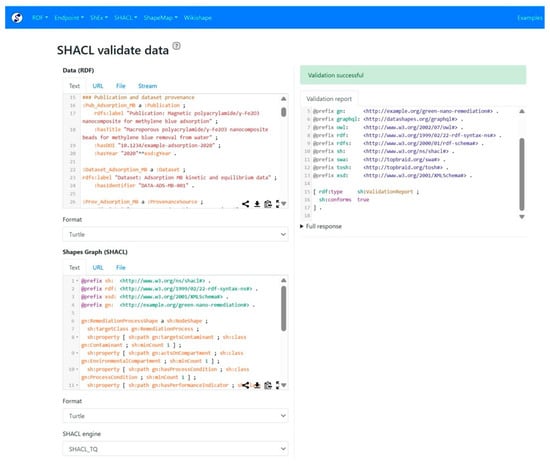

By enforcing these constraints, the ontology ensures that only semantically complete and structurally valid data are admitted into the Knowledge Graph. This validation layer moves beyond traditional logical consistency checking provided by OWL 2 reasoners and introduces explicit requirements for data completeness and interpretability. As illustrated in Figure 5, the validation reports generated by rudof confirm compliance with SHACL and ShEx constraints defined for the green remediation domain.

Figure 5.

Validation report generated by the rudof tool [22]. The interface demonstrates the enforcement of structural shapes (SHACL/ShEx) on the integrated Knowledge Graph.

This process is a prerequisite for ensuring that downstream machine learning and decision-support applications are trained on high-quality, unambiguous information, thereby supporting the development of AI-ready and FAIR-compliant datasets [8,23].

6.3. Semantic Querying and Knowledge Discovery

The practical utility of the framework was further evaluated through the execution of complex SPARQL queries designed to enable cross-domain knowledge discovery. Unlike conventional relational databases, the ontology-driven Knowledge Graph supports queries that traverse synthesis routes, physicochemical properties, remediation mechanisms, and sustainability descriptors within a single semantic context.

For example, a query linking plant-extract chemistry (via ChEBI identifiers [11]) with maximum adsorption capacity (qmax) revealed that materials synthesized using polyphenolic-rich precursors exhibited enhanced structural stability during magnetic recovery.

This relationship was explicitly represented through provenance and performance relations such as wasDerivedFrom and hasPerformanceIndicator [7,24]. These results illustrate the framework’s ability to preserve “material histories,” a capability that is essential for explainable AI applications in materials science and environmental engineering [17].

6.4. SPARQL Queries and Knowledge Discovery

Representative SPARQL 1.1 queries further demonstrate the Knowledge Graph’s capacity to support mechanistically grounded, sustainability-aware analysis. By leveraging OWL semantics, normalized descriptors, and provenance links, these queries enable the retrieval of insights that would otherwise require extensive manual curation from unstructured literature.

The framework supports queries that simultaneously integrate synthesis metadata, contaminant classes, performance indicators, and ISO-aligned sustainability attributes. For instance, researchers can identify green-synthesized nanomaterials achieving removal efficiencies above 90% for divalent heavy metals while also satisfying low-energy synthesis constraints defined in the SustainabilityProfile module. The integration of the Provenance module [7] ensures that all query results remain fully traceable to their original experimental sources, reinforcing auditability and trustworthiness.

6.4.1. Query Example 1—High-Performance Adsorbents

Retrieve nanomaterials synthesized with renewable solvents and exhibiting qmax > 100 mg·g−1 for any heavy metal.

| SELECT ?material ?qmax ?solvent WHERE { ?material a :Nanomaterial ; :hasSustainabilityProfile ?sust ; :hasPerformanceIndicator ?perf . ?sust :usesRenewableSolvent true . ?perf :qmax ?qmax . FILTER (?qmax > 100) } |

6.4.2. Query Example 2—Photocatalysts with Validated ROS Pathways

Retrieve photocatalysts with a narrow band gap, together with the band gap value and the reactive oxygen species (ROS) they generate. In practical terms, the query answers the question: Which photocatalysts in the knowledge graph are active under visible or near-visible light, and what reactive oxygen species do they generate?

Search for photocatalytic catalysts that have an associated optoelectronic property and also generate certain reactive species, filtering only those with a bandgap less than 3 eV. The result returns three pieces of data: the catalyst, its bandgap, and the reactive species generated.

| SELECT ?catalyst ?bandgap ?ros WHERE { ?catalyst a :Photocatalyst ; :hasOptoelectronicProperty ?opt ; :generatesReactiveSpecies ?ros . ?opt :bandGap ?bandgap . FILTER (?bandgap < 3.0) } |

6.4.3. Query Example 3—Sustainability Benchmarking

Retrieve materials ranked by the energy demand of their synthesis routes, together with a quantitative performance indicator, and orders the results from lowest to highest energy demand. Conceptually, the query answers the question: Which materials achieve a given remediation performance while minimizing synthesis energy demand?

For each material, gather three key pieces of information related to its synthesis and performance, and rank them in ascending order according to the energy demand of the synthesis route.

| SELECT ?material ?energyDemand ?performance WHERE { ?material :hasSynthesisRoute ?route ; :hasPerformanceIndicator ?perf . ?route :energyDemand ?energyDemand . ?perf :rateConstant ?performance . } ORDER BY ASC(?energyDemand) |

These examples show how the KG enables complex intersectional queries linking physicochemical, mechanistic, and sustainability dimensions. Collectively, these capabilities transform the Knowledge Graph from a static data store into a dynamic discovery engine that supports multi-criteria decision-making based on efficiency, chemical safety, and environmental impact [8,17].

The full OWL/Turtle instantiations of the adsorption and photocatalysis case studies, together with the SHACL shapes used for structural and semantic validation, are provided in Supplementary Material S4.

6.5. Ontology-Driven Insights and Implications

Several overarching insights emerge from the integrated semantic analysis. First, green synthesis does not inherently compromise remediation performance. Once normalized within the semantic framework, numerous, green-synthesized materials exhibit qmax and kapp values comparable to those of conventionally produced analogues, demonstrating that sustainability and functional efficiency can coexist [2,3].

Second, sustainability reporting across the literature remains highly inconsistent. The frequent absence of standardized energy-demand metrics and lifecycle descriptors underscores the necessity of structured sustainability modules and SHACL-based enforcement. By embedding these requirements directly into the ontology and validation workflow, the framework promotes transparency and reproducibility in sustainability assessment [22].

Third, the unified semantic representation enables cross-mechanistic reasoning. Adsorption and photocatalysis, traditionally evaluated in isolation, can be compared within a shared conceptual structure that integrates material properties, reaction mechanisms, and environmental impacts. This capability supports holistic evaluation strategies that align technical performance with sustainability objectives [16,17].

Finally, ontology-backed datasets are intrinsically better suited for AI-driven analysis. Explicit semantic relations, validated data structures, and consistent metadata significantly enhance the reliability and interpretability of downstream computational models. In this respect, the framework fulfills the core requirements for AI-ready data infrastructures in environmental informatics [8].

6.6. Discussion: Toward an AI-Ready Sustainable Framework

The integration of ISO 14001-aligned [14] sustainability descriptors represents a substantive advancement beyond existing nanomaterial ontologies [13,17]. By explicitly modeling energy demand, solvent greenness, and waste generation, the framework enables transparent comparison of the environmental footprint associated with different remediation strategies.

At the same time, the results confirm that semantic digitalization is not a one-time effort but an ongoing process. As emphasized by Garcia-Trelles et al. [16], sustained interoperability requires continuous alignment with emerging standards and vocabularies. The explicit alignment layer implemented in this framework ensures compatibility with external ontologies while minimizing semantic drift, in accordance with best practices for ontology matching and modular design [35].