Abstract

This study compares the two (2D)- and three-dimensional (3D) accuracy of tooth reduction depths in porcelain laminate veneer prepared using conventional and 3D-printed guide techniques. Forty 3D-printed maxillary casts were divided into four groups: freehand (FH) (n = 10), silicone guide (SG) (n = 10), cross-shaped 3D-printed guide (3D_C) (n = 10), and stackable 3D-printed guides (3D_S) (n = 10). Butt-joint veneer preparation was performed on the left central incisor. Two-dimensional analysis was performed to assess trueness using mean absolute differences (MADs) from the planned depth at eight designated points, while precision was compared within groups. Three-dimensional analysis evaluated trueness by superimposing post-preparation scans with reference casts and precision via intra-group superimposition, with deviation errors measured using the Root Mean Square (RMS) method. One-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc tests were used (α = 0.05). In 2D analysis, 3D_S exhibited a significantly lower MAD than FH at most of the measured points (p < 0.05), more accurate incisal reduction at mesial and distal points compared to 3D_C (p < 0.001), and more accurate mesial (p = 0.011) and distal (p = 0.001) cervical margin preparation than SG. In the 3D trueness assessment, 3D_S exhibited significantly lower deviation errors than FH (p < 0.001) and SG (p = 0.012) while also achieving the highest overall 3D precision with the lowest RMS (0.067 ± 0.013), followed by 3D_C (0.086 ± 0.019). Veneer preparation guided by a stackable 3D-printed guide resulted in more accurate tooth reduction depths compared to the other three techniques.

1. Introduction

Porcelain laminate veneers (PLVs), a minimally invasive approach for correcting discoloration, malposition, and morphological defects in anterior teeth, have become a cornerstone of modern esthetic dentistry. It is essential to optimize the tooth reduction depth, balancing the dual requirements of providing sufficient space to maintain restorative-material strength while preserving enamel for reliable bonding [1,2], for long-term clinical success.

Various techniques have been proposed for veneer preparation. In the conventional hands-free (FH) technique, commonly used due to its simplicity, depth-gauge burs are often utilized to create initial depth grooves, serving as a reference for completing subsequent veneer preparation [3]. However, the accuracy of this method largely depends on clinical skills and experience, which may lead to inconsistencies in reduction depth. Using a silicone guide (SG) is a conventional alternative approach in which a silicone index is fabricated based on a diagnostic wax-up of the desired final tooth contour [4], assessing reduction depth by measuring the spaces between the prepared tooth surface with a silicone template using a periodontal probe [5,6]. Despite the usefulness of SGs in providing a reference for tooth reduction, the accuracy of the tooth reduction depth may be compromised by the clinician’s freehand skills and the rigidity of the putty index [4].

With advancements in digital technology, the issue of attaining an inaccurate tooth reduction depth in conventional veneer preparation can be effectively addressed through computer-assisted veneer preparation. Various 3D-printed tooth reduction guides have recently been developed, primarily to facilitate the creation of depth grooves that assist in subsequent tooth reduction. Figueira et al. designed a simple guide with open window access, but its limited control over bur movement resulted in greater variability in tooth preparation depth [7]. Tinoco et al. proposed a cross-shaped guide that creates vertical and horizontal depth grooves at the mid-labial surface of the tooth; however, its reliance on subsequent freehand PLV preparation may result in inconsistent tooth reduction depths [8]. Gao et al. designed a more complex guide with multiple depth-guiding holes on the labial surface and incisal edge, used in combination with a calibrated bur with depth scales [9]. Despite this guide refinement, a deviation up to 0.3 mm was still reported. In addition to the guide designs, the accuracy of these guides is also affected by the type of printing technology used. Nevertheless, commonly used printing methods in tooth reduction guide fabrication including Digital Light Processing (DLP), Stereolithography (SLA), Liquid Crystal Display (LCD), and multi-jet printing (MJP) technology demonstrate a precision range between 25.4 μm and 62.0 μm [10], which falls within clinically acceptable limits.

Previous studies on the accuracy of guided veneer preparation have mainly reported site-specific linear measurements, which may not fully represent the overall tooth reduction accuracy across the entire prepared surface, as evaluated by 3D accuracy analysis. Therefore, this study aims to design a stackable 3D-printed guide (3D_S) to assist with each step of veneer preparation with less freehand assistance and to compare both the 2D and 3D accuracy of tooth reduction depths among veneers prepared using 3D_S, FH, SG, and a cross-shaped 3D-printed guide (3D_C). The null hypothesis was that there would be no significant difference in the 2D and 3D accuracy of the tooth reduction depth among the four veneer preparation techniques.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Size Calculation

Based on a previous study (Gao et al. 2022) [11], a minimum sample of 40 dental casts (10 dental casts per arm) was required after calculating the sample size for an expected power of 90%, alpha value of 0.05, and effect size of 0.52 (G* Power 3.1) to detect significant differences among the four groups.

2.2. Cast Preparation

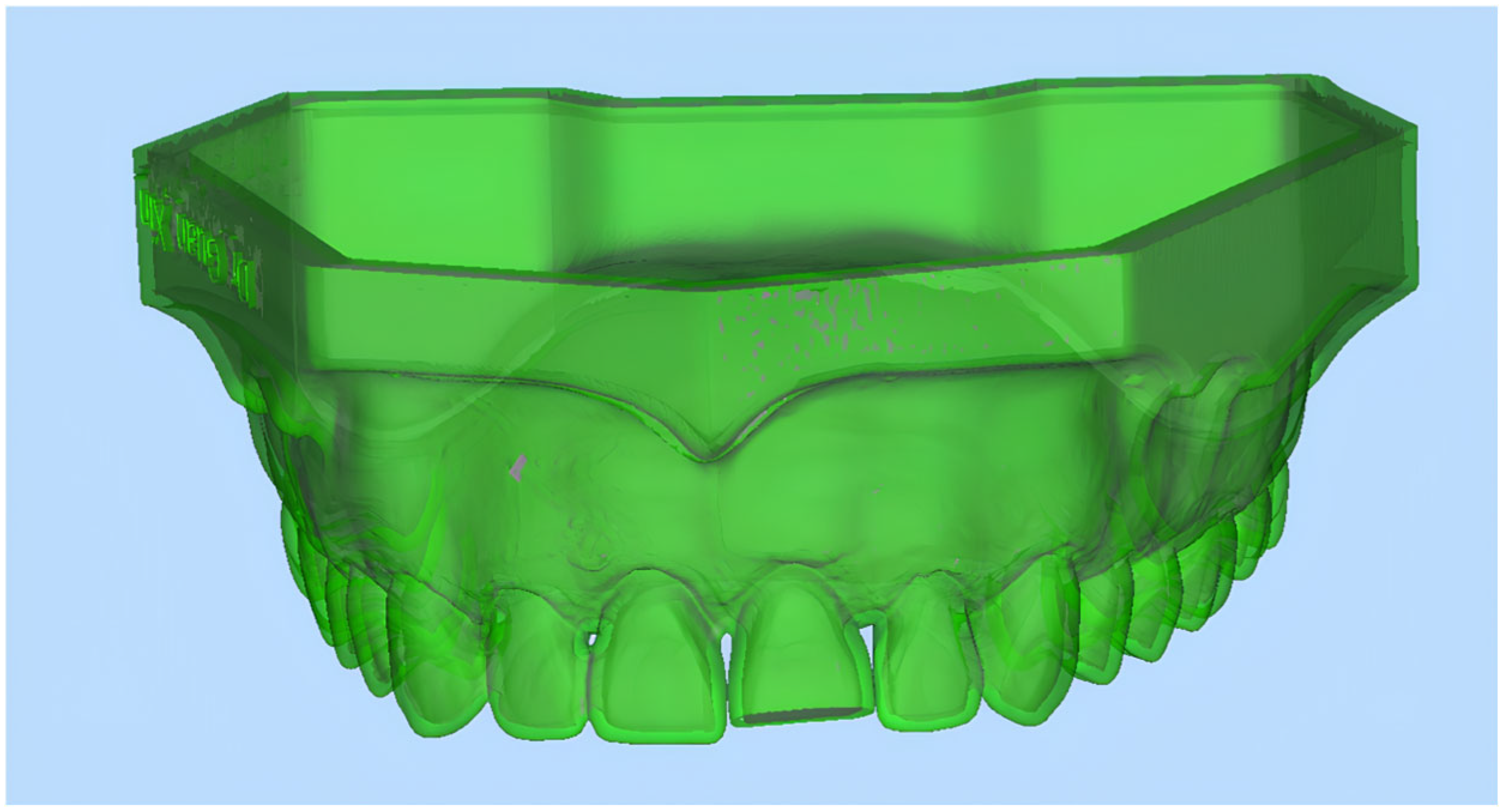

This in vitro study was conducted in the Simulation Clinic, Faculty of Dentistry, The National University of Malaysia. A maxillary complete-dentate typodont (Frasaco, Germany) was scanned using a laboratory scanner (3Shape Trios E4, Copenhagen, Denmark) with up to 4 μm accuracy to generate a digital cast in standard triangle language (STL) format. The laboratory scanner was calibrated following manufacturer’s recommendation prior to each scan. The digital cast was then used to design tooth reduction guides for 3D_C and 3D_S groups and to perform virtual PLV preparation on the maxillary left central incisor following butt-joint design at the pre-determined depths (1.5 mm for incisal reduction, 0.5 mm for labial reduction, and 0.3 mm for cervical margin reduction) [12,13] (Figure 1), serving as a reference (R) for 3D accuracy analysis. The digital cast was then printed using a 3D printer (ProJet MJP 3600; 3D Systems, Rock Hill, SC, USA) to produce forty 3D-printed dental casts. Each 3D-printed dental cast was labeled with identification numbers 1–40. The casts were then randomly allocated into four veneer preparation groups (FH, SG, 3D_C, and 3D_S) according to a computer-generated random number sequence, with 10 casts assigned to each group.

Figure 1.

Virtual butt-joint veneer preparation on maxillary left central incisor.

2.3. Porcelain Laminate Veneer Preparation Using Four Different Techniques

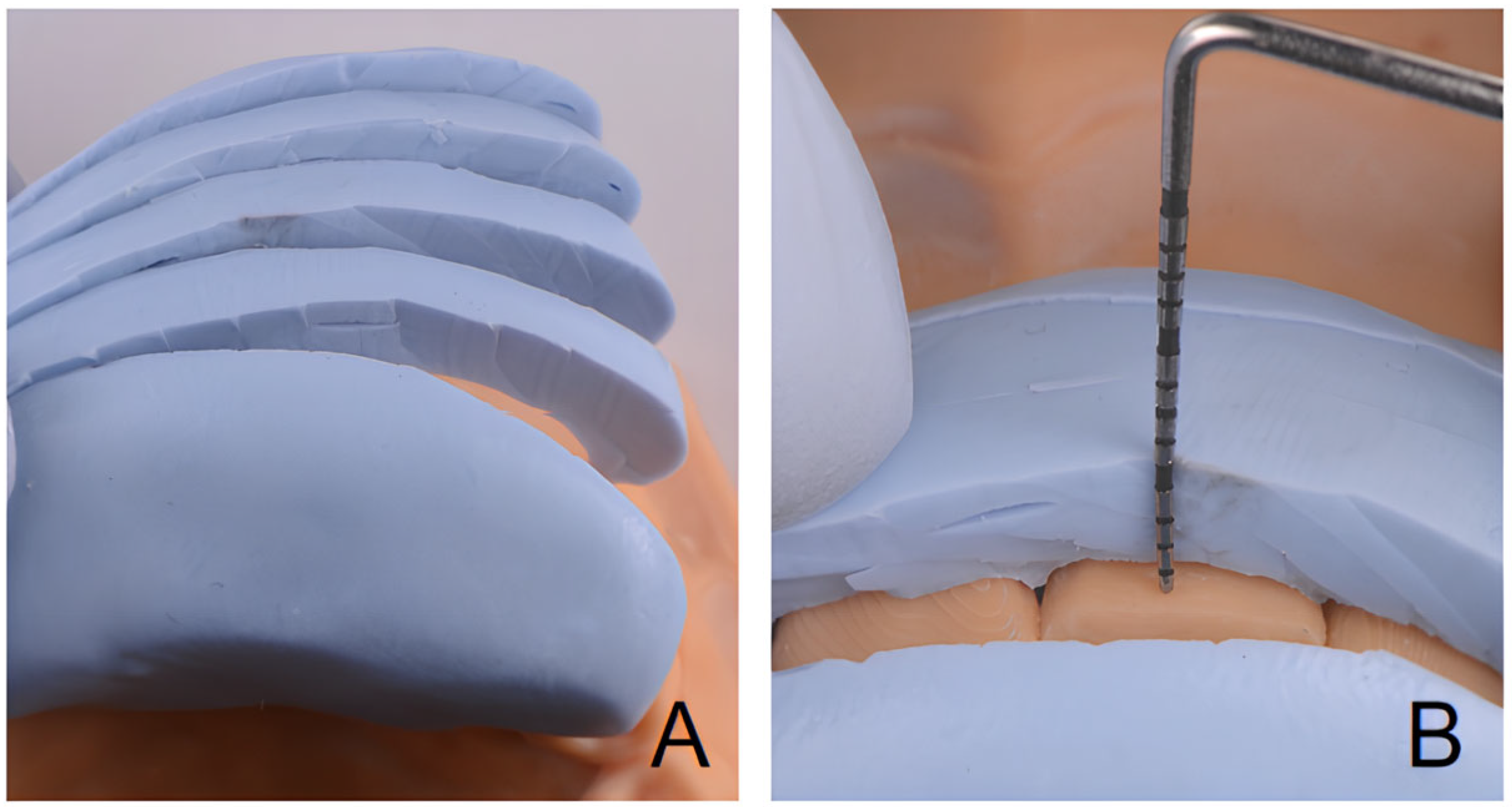

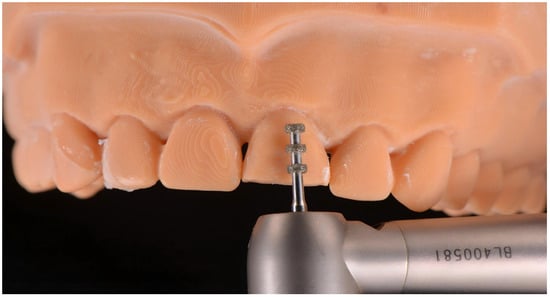

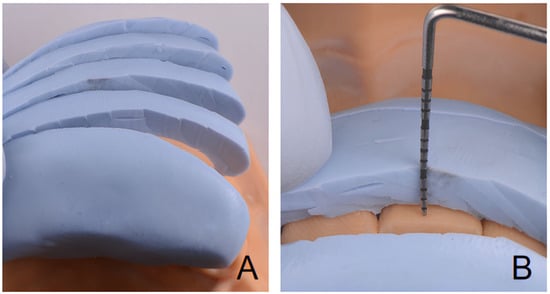

The maxillary left central incisor was designated as the target tooth for PLV preparation on the phantom head, following butt-joint design with pre-determined depths. All PLV preparation was performed by one clinician (X.G) who has five years’ clinical experience. In the FH group, three depth grooves were initially created at the incisal edge and labial surfaces using a 0.5 mm depth gauge bur (Figure 2). This was followed by subsequence freehand preparation to connect the grooves using a diamond chamfer bur (G/TR-32; Daobang, Foshan, China) to achieve the desired reduction depth. In the SG group, a silicone putty index of the maxillary right central incisor was fabricated and was sectioned horizontally at the incisal edge, incisal half and cervical half of the labial surface, and cervical regions. Veneer preparation was performed following the same technique as described for the FH group. The reduction depth was assessed using a periodontal probe, with the putty index serving as a guide (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

The initial reduction grooves were prepared using a depth gauge bur in the FH technique.

Figure 3.

SG technique. (A). Putty index sectioned horizontally. (B). Space verification using periodontal probe and silicone putty index.

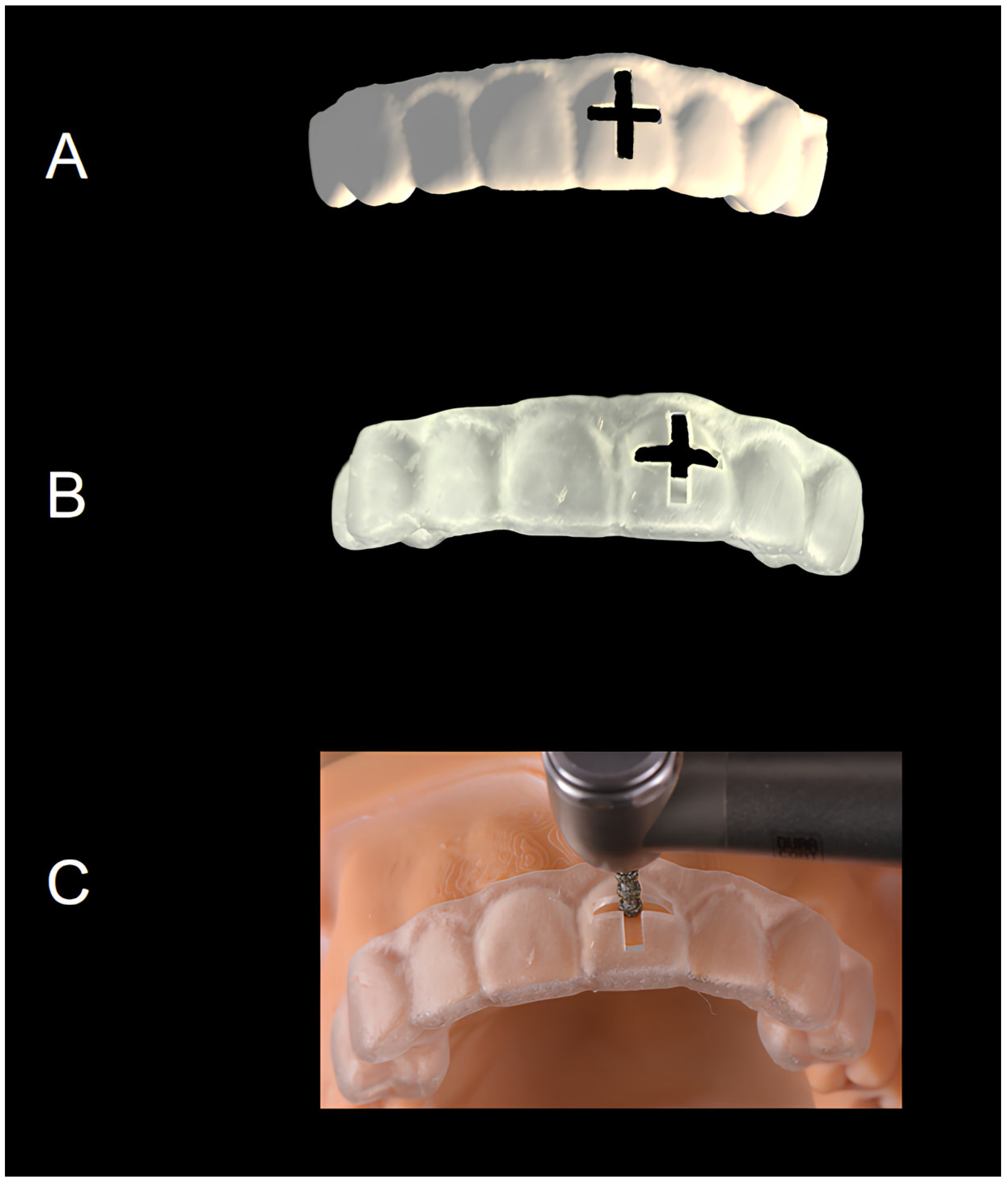

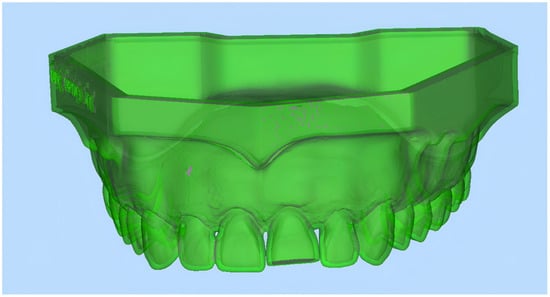

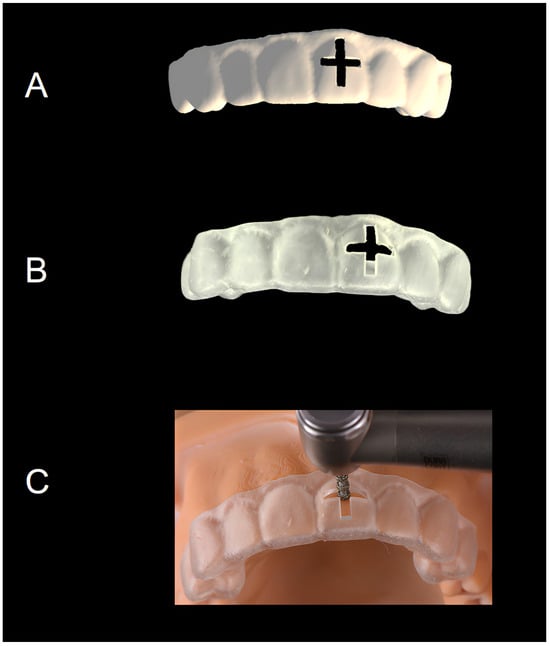

In the 3D_C group, a virtual tooth reduction guide with a cross-shaped window positioned 1.5 mm from the incisal edge of the maxillary right central incisor was designed using computer-assisted design (CAD) software (DentalCAD 3.1 Rijeka, exocad GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) (Figure 4A) [9], and 3D-printed using a 3D printer (ProJet MJP 3600; 3D Systems, Rock Hill, SC, USA) with a uniform 2 mm thickness (Figure 4B). After verifying its fit on the 3D-printed cast, a 0.5 mm deep cross-shaped groove was created by using a 2.5 mm thick depth gauge bur (G/EX-57, FG0807D, Daobang, Foshan, China) aligned with the guide surface under visual verification (Figure 4C). The guide was then removed, and veneer preparation of the incisal edge, incisal and cervical thirds of the labial surfaces, and cervical margins was completed freehand using a diamond chamfer bur (G/TR-32; Daobang, Foshan, China).

Figure 4.

3D_C veneer preparation technique. (A): Virtual guide design. (B): A cross-shaped 3D-printed guide. (C): Guided veneer preparation.

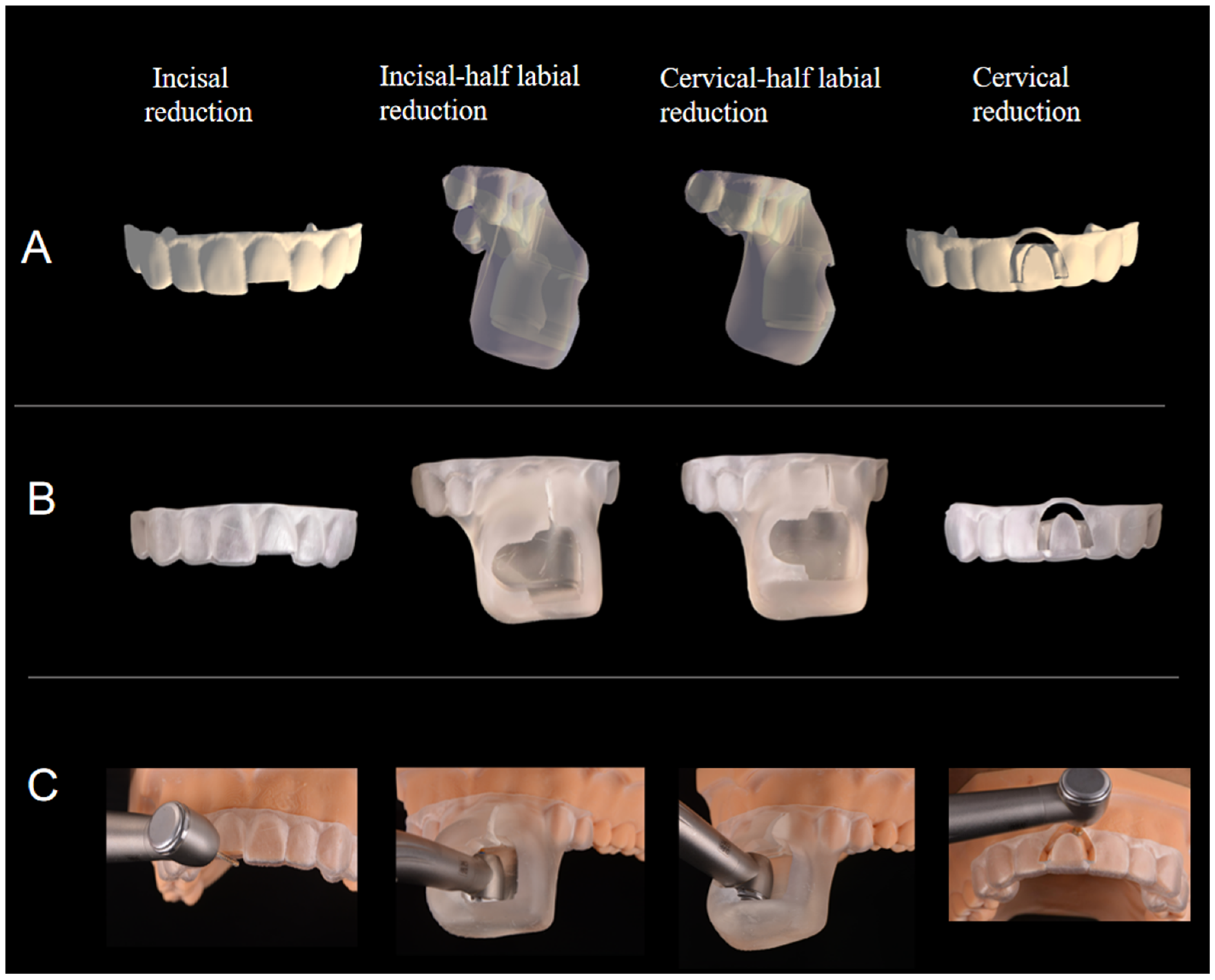

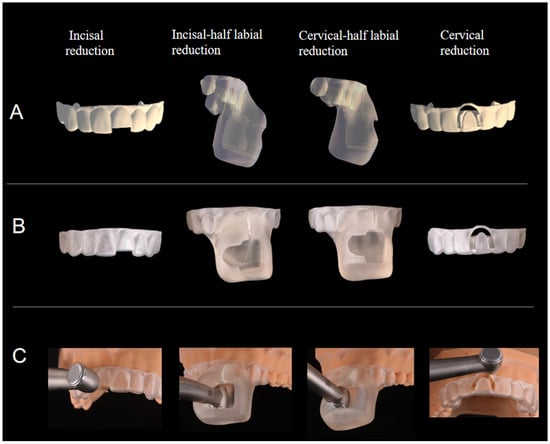

In the 3D_S group, four sequential tooth reduction guides designed to control both the pre-determined depth and direction of preparation were developed according to the methods described by Guan et al. [14] using CAD software (DentalCAD 3.1 Rijeka, exocad GmbH). The first guide featured a 1.5 mm incisal access window for incisal reduction (Figure 5A). The second and third guides facilitated the two-plane labial reduction with a 0.5 mm virtual inward offset and incorporated a guiding window and bur channel designed in AutoCAD software 2025 version 24.3 (Autodesk, San Rafael, CA, USA) to fit a virtual high-speed handpiece with a chamfer diamond rotary instrument (Figure 5A). The fourth guide was designed for cervical reduction, incorporating a window to fit a modified bur with a 0.3 mm length bur with a stopper (G/EX-58, Daobang, FG0807D, China) (Figure 5A). All the virtual guides were printed using a 3D printer (ProJet MJP 3600; 3D Systems, USA) with resin material (VisiJet M3 Crystal 3D Material, 3D System, USA), producing ten sets for each veneer preparation sequence (Figure 5B,C).

Figure 5.

3D_S veneer preparation technique. (A) Four virtual guide designs. (B) Four 3D-printed guides. (C) Guided veneer preparation.

Prior to proceeding with each step of PLV preparation in the 3D_S group, an accurate positioning of each guide was verified through visual inspection. The incisal reduction was assisted by the first guide and performed using a diamond chamfer bur (G/TR-32; Daobang, Foshan, China) to achieve a 1.5 mm incisal reduction. The incisal and cervical thirds of the labial surface were then prepared using the diamond chamfer bur (G/TR-32; Daobang, Foshan, China) under the guidance of second and third guides to obtain a labial reduction depth of 0.5 mm. Finally, the cervical margin reduction was guided by the fourth guide and performed using a modified diamond bur (G/EX-58; Daobang, Foshan, China) to prepare a margin depth of 0.3 mm. Each PLV step is shown in Figure 5C.

2.4. Two-Dimensional Tooth Reduction Depth Assessment

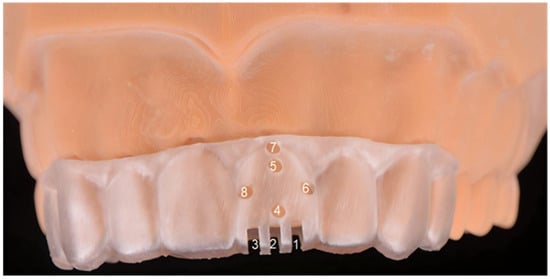

In the present study, the 2D and 3D accuracy were assessed in terms of two main variables: trueness and precision. This was performed by a single researcher (B.Y.H) who was blinded to the veneer preparation group. The 2D reduction depth was measured using a digital caliper (Casio, Shenzhen, China) at eight locations determined using the 3D-printed measurement guide (Figure 6). To determine the trueness of the reduction depth, each reduction depth was compared with the corresponding pre-determined depth (an incisal reduction of 1.5 mm depth, a labial reduction of 0.5 mm, and chamfer margins with a depth of 0.3 mm) and calculated as the mean absolute difference (MAD) following the formula below:

where

Figure 6.

Three-dimensional measurement guide with eight measurement points: 1: Distal point of incisal edge. 2: Mid-point of incisal edge. 3: Mesial point of incisal edge. 4: Incisal half of labial surface. 5: Cervical half of labial surface. 6: Distal point of cervical margin. 7: Mid-point of cervical margin. 8: Mesial point of cervical margin.

- xi = the reduction depth;

- d = the pre-determined depth;

- n = the number of samples.

The precision of the reduction depth was evaluated by determining the consistency of the reduction depth measurements relative to the mean reduction depth within each tooth preparation group. The precision is expressed as the MAD and was calculated using the following formula:

where

- xi = the reduction depth;

- μ = the mean reduction depth within each tooth preparation group;

- n = the number of samples.

2.5. Three-Dimensional Deviation Assessment

For 3D trueness analysis, forty 3D-printed prepared casts were scanned using a laboratory scanner (3Shape Trios E4, Denmark) to generate forty STL files. Each STL file was then superimposed onto a reference (R) using an automatic best-fit algorithm using 3D metrology software (Geomagic Control X software, version 2017.0.1; 3D Systems, Rock Hill, SC, USA). For 3D precision assessment, STL files within the same group were superimposed pairwise using the same alignment procedure. After superimposition, the maxillary left central incisor was segmented and defined as the region of interest (ROI). The surface deviation within the ROI was computed for both trueness and precision using Root Mean Square (RMS) values.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 27.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to confirm that the data for both 2D and 3D accuracy evaluation were normally distributed, with p > 0.05. One-way ANOVA with the Bonferroni post hoc test for pairwise comparison was used to compare the trueness and precision of the tooth reduction depth and 3D deviation across the four techniques with a confidence interval of 95% (α = 0.05).

3. Results

Forty maxillary left central incisors were prepared using four techniques: FH (n = 10), SG (n = 10), 3D_C (n = 10), and 3D_S (n = 10). The 2D trueness of the tooth reduction depth was compared among the four veneer preparation groups (Table 1), revealing significant differences at the incisal, labial, and cervical margin regions (p < 0.05). 3D_S showed the lowest deviation across all areas compared to FH (p < 0.05) and showed higher accuracy than 3D_C at the mesial and distal points of the incisal edge (p < 0.001), and SG at the cervical margin, particularly at the mesial (p = 0.011) and distal (p = 0.001) points. 3D_C outperformed FH in incisal-half labial reduction (p = 0.003), and at both the mesial (p = 0.026) and distal (p = 0.03) points of the cervical margin.

Table 1.

Two-dimensional trueness comparison of tooth reduction depths across four veneer preparation techniques (N = 40).

The 2D precision of the tooth reduction depths is compared among the four veneer preparation groups in Table 2. 3D_S demonstrated significantly higher precision in incisal reduction at all the measured points compared to FH (p < 0.05), at the mesial and distal points compared to 3D_C (p < 0.05), and at the mid-point compared to SG (p < 0.05). For labial reduction, both 3D_C and 3D_S exhibited significantly greater precision than FH and SG (p < 0.05). Furthermore, 3D_S achieved the highest precision in cervical margin reduction among all groups (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Two-dimensional precision comparison of tooth reduction depths across four veneer preparation techniques (N = 40).

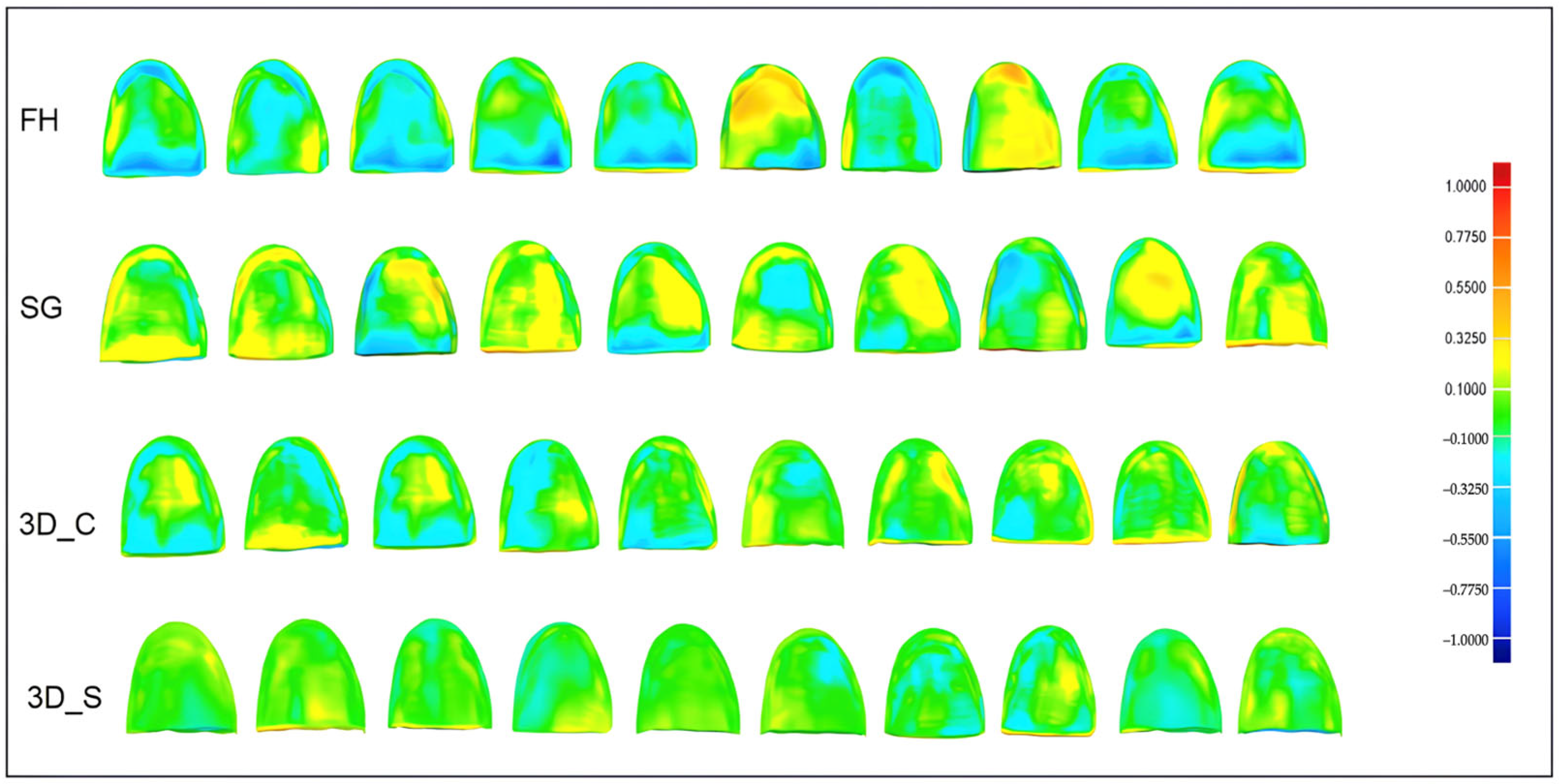

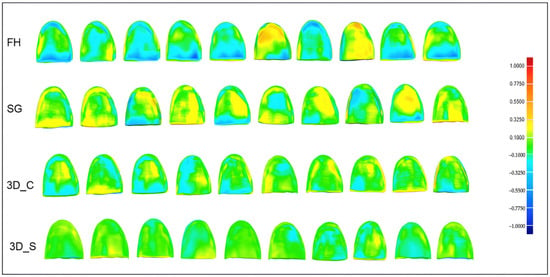

The trueness and precision as measured by the Root Mean Square Errors (RMSEs) in three-dimensional analysis are compared in Table 3. 3D_S demonstrated significantly lower deviation errors in trueness than FH (p < 0.001) and SG (p = 0.012). Furthermore, 3D_C showed significantly higher precision than FH (p = 0.002). The 3D deviation maps comparing the trueness of the tooth reduction depths among the four groups are illustrated in Figure 7. 3D_S exhibited the highest trueness, with most labial reduction within the nominal deviation range (±0.1 mm, green). FH showed the greatest deviations, especially with respect to under-reduction in the cervical half of the labial surfaces (−0.1 mm to −1.0 mm). SG and 3D_C demonstrated moderate trueness, with 3D_C performing better.

Table 3.

Three-dimensional accuracy comparison of tooth reduction depths across four veneer preparation techniques.

Figure 7.

Three-dimensional deviation maps for FH, SG, ST_P, and ST_C in trueness comparison (max/min nominal: 0.1 mm (green); max/min critical: 1.00 mm (dark red and dark blue)).

4. Discussion

Accurate tooth preparation is a prerequisite for PLVs to achieve optimal esthetic results and bonding strength. Therefore, this study aimed to develop a series of stackable 3D-printed tooth reduction guides to improve the accuracy of the tooth reduction depth. The null hypothesis was rejected because there was a significant difference in the accuracy of the tooth reduction depth among veneer preparation techniques, with 3D_S demonstrating superior accuracy compared to the other three techniques.

Among all the techniques evaluated, the conventional FH technique was the least accurate, with greater deviation at all the measured points, possibly due to its high dependence on the operator’s freehand skills. These findings are consistent with previous studies [11,15]. Notably, when comparing different preparation sites, labial reduction demonstrated slightly better accuracy, being approximately 0.1 mm more precise than incisal and cervical margin preparations, likely due to the use of a wheel-shaped depth gauge bur. This finding is supported by Ahlers et al., who highlighted the significance of using a depth gauge bur in achieving more controlled depths during initial veneer preparation [3].

The SG technique, which uses a silicone index for guidance, showed limited improvement in accuracy, except for incisal reduction. This may be due to the putty’s thickness and flexibility. Retaining a bulk of putty index around the incisal edge [4] reduces the likelihood of distortion, thereby improving the accuracy of incisor reduction. However, horizontal slicing of the putty for labial and cervical margin preparation reduces its rigidity [16], compromising the accuracy of space verification, and thus leading to greater deviations in reduction depth.

The introduction of CAD/CAM systems has improved PLV preparation accuracy by enabling the design and 3D-printing of tooth reduction guides, allowing for better control of reduction depth. This improvement was demonstrated in this study, where both the 3D_C and 3D_S techniques exhibited lower mean deviations. These findings suggested that the achieved reduction depths on labial surfaces and at the cervical margins remained within enamel and were consistent with the ideal ranges of 0.4–0.6 mm and 0.201–0.399 mm for the labial surfaces and cervical margins respectively, as recommended by Cherukara et. al. [17]. Enamel preservation during PLV preparation is crucial for optimizing bonding strength and thus improving the long-term survival of the PLV [18].

Among various 3D-printed guide designs [8,11,19,20], the commonly used cross-shaped 3D printed guide (3D_C) [8,18] was chosen as one of the comparative groups in this study due to its simplicity. Although 3D_C significantly improved accuracy at the incisal half of the labial reduction and the cervical margins compared to the FH, its overall trueness was lower than that of 3D_S, likely due to the need for freehand finishing. Furthermore, a single depth groove at the midpoint, 1.5 mm below the incisal edge, did not significantly improve the incisal reduction trueness over FH and SG.

The 3D_S guide, which eliminates the freehand preparation, achieved the lowest mean deviation (≤0.1 mm) at most points, highlighting the advantage of fully controlled bur movement during guided veneer preparation. The window access in the first 3D_S guide allowed more precise guidance for incisal reduction, reducing the deviation 2–3-fold compared to the other three groups. This is clinically important because accurate incisal reduction helps achieve an optimal PLV thickness, thereby improving fracture resistance and supporting favorable long-term clinical outcomes [21]. The incorporation of window access and a bur-guiding channel in the second and third 3D_S guides enhanced the control of bur movement during labial reduction. This significantly minimized the reduction depth deviation compared to the FH and SF groups and helped maintain the intra-enamel preparation, thereby optimizing bonding strength. Despite enhancing accuracy, the bulky window access design may be a challenge for patients with limited mouth opening; therefore, further refinement is needed to enhance its clinical applicability across a wider range of situations. However, compared to the first-fit system, which also provides full control of bur movement for labial reduction, the 3D_S guide design avoids the need for a specialized handpiece, reducing additional costs [16].

The fourth 3D_S guide incorporated window access to control the movement of a length-modified rotary instrument, achieving the highest trueness at the cervical area, with a mean deviation of 0.1 mm. This precision helps in keeping enamel thickness within 0.59 mm [22] for the optimal bonding of PLVs [19]. To achieve the designated cervical margin depth of 0.3 mm, a cost-effective approach was employed using a chamfer bur with a stopper, modified in length and calibrated via CAD software during the guide design, eliminating the need for custom rotary instruments.

In this study, the accuracy of the tooth reduction depth was comprehensively assessed using both 2D and 3D deviation analyses. The 2D measurements provided site-specific evaluation at eight locations, designated at the incisal edge, labial surface, and cervical margins, that could be directly compared with the pre-determined reduction depths across the four different PLV preparation techniques. As an evaluation standard, the use of a digital caliper offers greater accuracy and reproducibility compared with digital measurements performed using the “2D deviation analysis” in software [23,24,25]. In contrast, 3D deviation analysis offered a holistic evaluation of the prepared tooth, capturing the entire curved surface and serving as a validation tool for overall accuracy. The findings demonstrated consistency between the two methods, with 3D analysis confirming the superior accuracy of the 3D_S guide, particularly in achieving highly accurate and consistent labial reduction (±0.1 mm), as shown in the 3D deviation color map. The 3D_S guide effectively preserved the two-plane labial contour as compared to the other groups, ensuring the uniform reduction essential for optimal ceramic thickness and esthetics in PLV fabrication. In contrast, the FH samples commonly exhibited under-preparation at the cervical half of labial surfaces, risking over-contoured PLVs and compromised esthetic and periodontal health [26,27].

From a cost-effectiveness perspective, compared with the conventional FH and SG approach, the use of 3D_S for a simple case involving a single PLV preparation may not be economically justified, as it often requires a complex guide design and incurs additional costs for printing multiple guides. However, 3D_S is particularly beneficial in more complex cases that demand a high level of preparation accuracy to optimize esthetic and bonding performance, such as cases involving multiple PLV, mal-aligned teeth, or discolored teeth.

Additive manufacturing enables the fabrication of precise 3D-printed tooth reduction guides with complex designs, offering advantages over subtractive manufacturing, by minimizing material waste and production time [28]. Clear resin is recommended for the 3D-printed guide to enhance the visibility of the rotary instrument’s movement and the tooth surfaces to be prepared [29,30]. In addition, the use of a transparent 3D-printed guide facilitates visual inspection to verify proper guide seating on the 3D-printed casts. However, this approach remains subjective and may compromise the accuracy of tooth reduction and subsequent measurements. Therefore, future studies should incorporate a more objective verification method, such as using intraoral scans to confirm guide positioning as suggested by Bittar et al. [31]. To prevent wear from repeated contact with the bur, ten guides were fabricated per tooth sample in the 3D_C and 3D_S groups.

To optimize the dimensional accuracy of the dental casts for PLV preparation in this study, dental casts were 3D-printed using a laboratory scanner with an accuracy of 4 μm, printing layer thickness of 50 μm, and 0° build platform angle [32]. However, the digital workflow would introduce cumulative scan–print errors potentially affecting the study’s outcome. To minimize the cumulative scan–print errors, the laboratory scanner was calibrated according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, and the printing protocols were standardized and strictly followed, including the use of optimal printing parameters. The postprocessing procedures were also carefully controlled, including cleaning with 90% isopropyl alcohol and post-curing at 60 °C.

The 3D-printed dental casts may undergo dimensional changes over time [33], potentially affecting accuracy assessment. To minimize this inherent deformation, all the 3D-printed casts in this study were printed with a hollow design, kept in a dark box, and used for PLV preparation and measurements 28 days after printing. Vincze et al. reported that dimensional changes of less than 25 μm occurred within 10 weeks, which was within the clinically acceptable range, suggesting that reprinting of casts is not necessary [34].

This study has several limitations. First, it did not assess the tooth reduction depth after polishing, which may contribute to additional tooth loss. Second, the design of 3D_C may not represent the most appropriate comparator for the tested design, despite its simple design; its single-point incisal reduction guidance feature could have biased the outcome in favor of the newly developed 3D_S design. Third, given the relatively small sample size with multiple point-wise comparisons, future studies should include larger sample sizes to reduce the risk of a Type II error. Fourth, the involvement of a single operator in parameter measurement, although eliminating inter-operator variability, limited the external validity and assessment of how the clinical experience of individuals may influence the accuracy of conventional versus guided PLV preparation. Fifth, the design and fabrication of the 3D_S guide can be time-consuming and technically demanding, potentially limiting its accessibility in routine clinical practice. Future improvements should therefore focus on simplifying and automating the design process through advanced CAD/CAM software and a streamlined workflow to enhance feasibility in different clinical situations. While the current 3D_S guide design is feasible for single PLV preparation, further refinement, especially for labial reduction, is needed to extend its applicability to multiple PLV preparation. Further studies should incorporate enamel thickness analysis to further validate the effectiveness of this innovative protocol in enamel preservation. Sixth, this was an in vitro study involving tooth preparation on 3D-printed dental casts, which have properties different from natural enamel; therefore, the findings should be interpretated with caution and may not be directly generalizable to clinical practice.

5. Conclusions

Within the limitations of this study, a stackable 3D-printed tooth reduction guide proved to be a promising computer-assisted veneer preparation technique, significantly improving the accuracy of the tooth reduction depth compared to conventional freehand and silicone guide techniques. However, further clinical studies are warranted to validate its effectiveness in clinical practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: X.G. and I.M.T.; methodology: all authors; writing—original draft preparation: X.G.; reviewing and editing: I.M.T.; validation: I.M.T. and Y.H.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Da Cunha, L.F.; Pedroche, L.O.; Gonzaga, C.C.; Furuse, A.Y. Esthetic, occlusal, and periodontal rehabilitation of anterior teeth with minimum thickness porcelain laminate veneers. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2014, 112, 1315–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, E.; Bolay, Ş. Survival of porcelain laminate veneers with different degrees of dentin exposure: 2-year clinical results. J. Adhes. Dent. 2014, 16, 481–489. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlers, M.O.; Cachovan, G.; Jakstat, H.A.; Edelhoff, D.; Roehl, J.C.; Platzer, U. Freehand vs. depth-gauge rotary instruments for veneer preparation: A controlled randomized simulator study. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2023, 68, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhola, S.; Barker, D. Composite build-ups: A review of current techniques in restorative dentistry. Dent. Update 2020, 47, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nattress, B.R.; Youngson, C.C.; Patterson, C.J.W.; Martin, D.M.; Ralph, J.P. An in vitro assessment of tooth preparation for porcelain veneer restorations. J. Dent. 1995, 23, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouri, V.; Moldovani, D.; Papazoglou, E. Accuracy of direct composite veneers via injectable resin composite and silicone matrices in comparison to diagnostic wax-up. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, J.; Guaqueta, N.; Ramirez, D.I.; Kois, J. Veneer tooth preparation utilizing a novel digital designed workflow: A case report. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2023, 35, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villalobos-Tinoco, J.; Jurado, C.A.; Robles, M.; Azpiazu-Flores, F.X. Tooth-reduction 3D-printed guides for facilitating the provision of ultrathin laminate veneers: A cross-shaped novel design. Int. J. Esthet. Dent. 2023, 18, 390–404. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Li, J.; Liu, C. A stereolithographic template for computer-assisted teeth preparation in dental esthetic ceramic veneer treatment. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2020, 32, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Beh, Y.H.; Tew, I.M. Computer-assisted porcelain laminate veneer preparation: A scoping review of stereolithographic template design and fabrication workflows. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; He, J.; Fan, L. Accuracy of reduction depths of tooth preparation for porcelain laminate veneers assisted by different tooth preparation guides: An in vitro study. J. Prosthodont. 2022, 31, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alothman, Y.; Bamasoud, M.S. The success of dental veneers according to preparation design and material type. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 2402–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, S.Y.; Bennani, V.; Aarts, J.M.; Lyons, K. Incisal preparation design for ceramic veneers: A critical review. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2018, 149, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Liu, C.; Sheng, T.F.; Beh, Y.H.; Tew, I.M. Innovative stackable multijet-printed templates for precise veneer preparation: A dental technique. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Y.; Bai, H.F.; Zhao, Y.J. 3D evaluation of accuracy of tooth preparation for laminate veneers assisted by rigid constraint guides printed by selective laser melting. Chin. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 23, 183–189. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, B.P.D.; Stanley, K.; Gardee, J. Laminate veneers: Preplanning and treatment using digital guided tooth preparation. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2020, 32, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherukara, G.P.; Seymour, K.G.; Zou, L.; Samarawickrama, D.Y. Geographic distribution of porcelain veneer preparation depth with various clinical techniques. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2003, 89, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamantino, P.S.; De Andrade, G.S.; Diamantino, M.G.G.; Francci, C.E.; Saavedra, G.S.F.A.; Tribst, J.P.M. Laminate veneers phenomena: Esthetics above biology and function? Dent. Med. Probl. 2025, 62, 779–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robles, M.; Jurado, C.A.; Azpiazu-Flores, F.X. An innovative 3D printed tooth reduction guide for precise dental ceramic veneers. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Luo, T.; Zhao, Y. Accuracy of the preparation depth in mixed targeted restorative space type veneers assisted by different guides: An in vitro study. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2023, 67, 556–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Cisne Maldonado, K.; Espinoza, J.A.; Astudillo, D.A.; Delgado, B.A.; Bravo, W.D. Resistance of CAD/CAM composite resin and ceramic occlusal veneers to fatigue and fracture in worn posterior teeth: A systematic review. Dent. Med. Probl. 2024, 61, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jánosi, K.M.; Cerghizan, D.; Mureșan, I. Quantitative evaluation of enamel thickness in maxillary central incisors in different age groups utilizing cone beam computed tomography: A retrospective analysis. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redlich, M.; Weinstock, T.; Abed, Y. A new system for scanning, measuring and analyzing dental casts based on a 3D holographic sensor. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2008, 11, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenović, D.; Popović, L.; Mihailović, B. Comparison of measurements made on digital 2D models and study casts. Acta Fac. Med. Naiss. 2009, 26, 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Budiman, J.A. Comparing methods for dental casts measurement. Asian J. Appl. Sci. 2016, 4, 143–147. [Google Scholar]

- Javaheri, D. Considerations for planning esthetic treatment with veneers involving no or minimal preparation. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2007, 138, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaß, J.A.; Büsch, C.; Körner, G.A.; Bäumer, A.M. Ceramic anterior veneer restorations in periodontally compromised patients: A retrospective study. Clin. Adv. Periodontics 2023, 13, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüceer, Ö.M.; Kaynak Öztürk, E.; Çiçek, E.S. Three-dimensional-printed photopolymer resin materials: A narrative review on their production techniques and applications in dentistry. Polymers 2025, 17, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Souza, K.M.; Aras, M.A. Types of implant surgical guides in dentistry: A review. J. Oral Implantol. 2012, 38, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keßler, A.; Dosch, M.; Reymus, M.; Folwaczny, M. Influence of 3D-printing method, resin material, and sterilization on the accuracy of virtually designed surgical implant guides. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 128, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bittar, E.; Binvignat, P.; Villat, C.; Maurin, J.C.; Ducret, M.; Richert, R. Assessment of guide fitting using an intra-oral scanner: An in vitro study. J. Dent. 2023, 135, 104590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlea, P.; Stefanescu, C.; Dalaban, M.G.; Petre, A.E. Experimental study on dimensional variations of 3D printed dental models based on printing orientation. Clin. Case Rep. 2024, 12, e8630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarbah, M.; Aldowah, O.; Alqahtani, N.M.; Alqahtani, S.A.; Alamri, M.; Alshahrani, R.; Mohsinah, N. Dimensional stability of 3D-printed edentulous and fully dentate hollowed maxillary models over periods of time. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincze, Z.É.; Kovács, Z.I.; Vass, A.F.; Borbély, J.; Márton, K. Evaluation of the dimensional stability of 3D-printed dental casts. J. Dent. 2024, 151, 105431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.