Abstract

This study evaluated the effects of bacterial fermentation (Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, CHOOZIT®, and YO-MIX®) and enzymatic hydrolysis (Protamex® and Neutrase® at 1% w/w and 5% w/w) on the proximate composition and antioxidant activity of bee pollen from the Colombian tropical dry forest. Both treatments significantly modified the nutritional profile, increasing moisture content (48–71% fermented; 50–68% hydrolyzed) while reducing protein and carbohydrate fractions. Fermentation produced strain-dependent antioxidant effects: L. plantarum maximized ABTS scavenging, while YO-MIX® 1:1 achieved the highest DPPH activity. Enzymatic hydrolysis demonstrated superior and more consistent improvements across all assays: Neutrase® 1% achieved 8.5-fold ABTS enhancement, while Protamex® 1% maximized DPPH scavenging (8-fold). All enzymatic treatments increased total phenolic content by 70–84%. Protamex® 1% emerged as the optimal treatment, achieving the highest DPPH activity (2689 µM Trolox equivalents/g pollen), substantial antioxidant enhancement across all assays, and preserved nutritional stability (201 kcal/100 g). These findings support the use of mild enzymatic hydrolysis for valorizing Colombian tropical bee pollen as a functional food ingredient with enhanced bioavailability.

1. Introduction

Bee pollen is recognized as one of the most complete natural foods due to its exceptional nutritional and bioactive composition. It contains proteins (10–40% dry basis, db), lipids (1–20% db), and carbohydrates (20–60% db). Bee pollen also has vitamins, minerals, phenolic compounds, and enzymes that confer antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and immunomodulatory properties [1,2]. However, the bioavailability of these nutrients is significantly limited by the presence of sporopollenin, a highly resistant biopolymer composed of carotenoids and carotenoid esters that forms the outer wall (exine) of pollen grains [3,4]. This structural barrier hinders the digestion and absorption of bioactive compounds, thereby reducing the functional potential of pollen in human nutrition and limiting its application as a functional food ingredient [3].

In recent years, various biotechnological strategies have been explored to overcome this limitation and enhance the functional properties of bee pollen [5]. Among these, bacterial fermentation and enzymatic hydrolysis have emerged as promising approaches [6,7]. Fermentation with lactic acid bacteria, particularly species such as Lactiplantibacillus plantarum (formerly known as Lactobacillus plantarum) and Lactobacillus rhamnosus, has been shown to improve the digestibility of pollen by partially degrading the sporopollenin wall through the production of organic acids and extracellular enzymes. This process increases the release of bioactive compounds, enhances antioxidant activity, and generates bioactive peptides with potential health benefits [8,9].

Recent studies have demonstrated that fermentation significantly modifies the chemical composition and functional properties of pollen. Damulienė et al. [10] reported that bacterial fermentation increased lactic acid production from 0.2% to 2.8% over 72 h and improved the bioavailability of phenolic compounds by 35–50% in bee pollen, with concurrent increases in 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging activity of 40–65%. The study also demonstrated enhanced antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Similarly, Xue et al. [11] highlighted that fermentation with Limosilactobacillus reuteri decreased pH from 5.8 to 4.4 and enhanced the nutritional value through increased free amino acid content (from 12.3 mg/g to 18.7 mg/g) and improved protein digestibility (from 68% to 82%). Cheng et al. [12] emphasized the potential of fermented pollen as a functional ingredient in food production, citing improvements in antioxidant capacity (25–60% increase in FRAP values) and bioactive compound release, particularly phenolic acids and flavonoids.

Enzymatic hydrolysis using commercial proteases represents another effective approach to improving pollen functionality. Proteases such as Protamex® (from Bacillus sp.) and Neutrase® (from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens) facilitate the breakdown of structural proteins in the pollen wall, improving nutrient bioavailability and generating bioactive peptides with antioxidant, antimicrobial, and immunomodulatory properties [13].

The comparative evaluation of bacterial fermentation and enzymatic hydrolysis is essential for establishing evidence-based processing recommendations, as each strategy offers distinct advantages and limitations [5]. Bacterial fermentation provides multiple benefits beyond cell wall disruption, including the production of probiotic metabolites, organic acids with antimicrobial properties, exopolysaccharides, and bacteriocins with antibacterial effects [14]. However, fermentation processes are inherently variable due to their dependence on microbial metabolism, environmental conditions, and substrate composition, requiring longer processing times (48–72 h) and careful control of parameters such as pH, temperature, and oxygen availability [14,15]. In contrast, enzymatic hydrolysis offers greater process control, reproducibility, and shorter reaction times (2–6 h), enabling precise modulation of the degree of hydrolysis and targeted release of specific bioactive compounds [16]. Nevertheless, enzymatic treatments require higher initial investment in enzyme acquisition and may not generate the probiotic-associated health benefits conferred by fermentation. Given these complementary characteristics, a systematic comparison of both approaches using standardized substrates and analytical methods is necessary to guide the selection of optimal processing strategies for specific functional food applications.

Pasarin and Rovinaru [17] demonstrated that enzymatic hydrolysis with Protamex and Alcalase 2.4L achieved degrees of hydrolysis of 9–10% in multifloral pollen, with significant release of soluble peptides (from 8.2 mg/g to 15.6 mg/g) and improved antioxidant capacity (IC50 of DPPH values decreased from 2.8 mg/mL to 1.6 mg/mL). Li et al. [18] reported that deep enzymatic hydrolysis with combinations of proteases and carbohydrases improved nutrient release by 45–70%, increased total phenolic content by 38%, and enhanced antioxidant activity (2,2′-azino-bis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid, ABTS) values increased from 156 μM Trolox equivalents/g to 234 μM Trolox equivalents/g).

Adaškevičiūtė et al. [19] demonstrated that fermentation significantly altered the polyphenolic composition of bee pollen, with increases in specific compounds such as quercetin (from 0.8 mg/g to 2.1 mg/g), kaempferol (from 0.3 mg/g to 0.9 mg/g), and phenolic acids (from 3.2 mg/g to 5.7 mg/g), contributing to enhanced antioxidant properties. The fermentation process also led to partial depolymerization of complex phenolic compounds, making them more bioavailable for absorption in the gastrointestinal tract.

Recent studies have further expanded our understanding of pollen biotransformation. Sakhraoui et al. [20] characterized multifloral bee pollen from distinct geographical regions and demonstrated significant variability in bioactive composition related to botanical origin. Xue et al. [11] reported that synergistic fermentation combining bacteria and enzymes enhanced the nutritional value and intestinal health benefits of tea bee pollen. Furthermore, Damulienė et al. [10] showed that the combination of fermentation and enzymatic hydrolysis improved the antibacterial properties of bee pollen against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens. Despite these advances, no study has systematically compared the effects of multiple bacterial strains (including both single-strain and commercial mixed cultures) and different proteolytic enzymes on the same pollen substrate from tropical ecosystems. The present study addresses this gap by providing the first comprehensive comparative analysis of bacterial fermentation and enzymatic hydrolysis on bee pollen from the Colombian tropical dry forest, evaluating their differential impacts on proximate composition, fermentation dynamics, and antioxidant capacity using a multi-assay approach.

Despite these advances, there is limited information on the comparative effects of different fermentation strains and enzymatic treatments on the physicochemical and bioactive properties of bee pollen from tropical regions. The Montes de María subregion, located in the central area of the departments of Bolívar and Sucre in the Colombian Caribbean, is an area of high biodiversity characterized by tropical dry forest ecosystems with over 1800 plant species recorded [21]. The region experiences a bimodal rainfall pattern with annual precipitation of 800–1200 mm, creating unique ecological conditions that favor diverse floral species and, consequently, polyfloral bee pollen with distinctive compositional characteristics [22,23]. Bee pollen from this region represents a valuable but underexplored resource with potential applications in functional food development and nutraceutical industries. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of bacterial fermentation (using L. plantarum and commercial cultures CHOOZIT® and YO-MIX®) and enzymatic hydrolysis (using Protamex® and Neutrase® at concentrations of 1% w/w and 5% w/w) on the proximate composition, pH dynamics, lactic acid production, total phenolic content, and antioxidant activity of bee pollen from the Montes de María tropical dry forest. This research aims to contribute to the valorization of regional bee pollen and provide scientific evidence for its use as a functional ingredient in the food and nutraceutical industries.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pollen Collection and Pretreatment

Raw bee pollen was collected from apiaries located in the Montes de María (9.7397° N, 75.1200° W; Bolívar, Colombia) during the dry season (January–February 2025) and stored in polyethylene bags at 4 °C in darkness until analysis. Once the pollen was obtained, samples were dried in an oven with hot air for 7 h at 53 °C (INB 400 oven, Memmert, Büchenbach, Germany) to prevent contamination by microorganisms and undesirable fermentation processes. After drying, the pollen was sieved using a 100-mesh stainless-steel sieve with 4 mm openings and dimensions of 60 cm × 90 cm.

2.2. Pollen Fermentation

Pollen fermentation with lactic acid bacteria was carried out to evaluate its effects on the physicochemical and bioactive characteristics of the substrate. For this purpose, the ATCC 8014 L. plantarum strain and the commercial starter cultures CHOOZIT® TM 82 LYO 50 DCU and YO-MIX® 885 LYO 50 DCU (Danisco–IFF, Épernon, France) were used, applying pollen:water ratios of 1:1 w/v and 1:2 w/v. At this stage, in addition to the treatments, two types of blank samples were included, corresponding to unfermented pollen with and without the addition of water.

2.3. Lactic Acid Bacterium Activation

The strain was reactivated following the manufacturer’s instructions. For this, the strain was inoculated into 9 mL of Man, Rogosa and Sharpe broth (MRS; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and incubated at 35 °C for 24 h under anaerobic conditions. It was then streaked onto MRS agar plates and incubated for an additional 24 h at 35 °C. Finally, the colonies were suspended in 0.1% saline until turbidity equivalent to a 0.5 McFarland standard was reached.

In the case of the commercial cultures CHOOZIT® and YO-MIX®, the lyophilized powders were rehydrated and inoculated into the corresponding medium under the same conditions described above.

2.4. Preparation of the Substrate and Fermentation

Before fermentation, 200 g of substrate was prepared according to each pollen-to-water ratio described above. The mixtures were transferred into 250 mL glass jars and sterilized at 121 °C for 15 min (All American 75X electric 40 L autoclave, Inmeza, Sarasota, FL, USA). Subsequently, the corresponding inoculum was added, and samples were incubated at 37 °C for 72 h under anaerobic conditions. The pH and lactic acid percentage were measured at 0 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h to monitor the progression of the fermentation process. For comparative purposes, an additional process was performed using an inoculum taken directly from the MRS broth of the activation stage, without adjustment to the McFarland standard. This sample, referred to as “pure inoculum,” was prepared at a pollen:water ratio of 1:1 w/v. Two blanks were also included: one without inoculum and another without pollen. All samples were prepared in duplicate, and the initial pH was adjusted to 5.8 using a 1 N NaOH solution (Merck, Germany). During each day of fermentation, 2 mL aliquots of each sample were withdrawn for titratable acidity analysis. This was conducted by adding 50 µL of phenolphthalein indicator (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and titrating with 0.1 N NaOH until a very faint pink color persisted for 15–30 s.

2.5. Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Pollen

The commercial enzymes Protamex® (protease from Bacillus spp. P0029, MERCK-SIGMA, Søborg, Denmark) and Neutrase® (protease from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens P1236, MERCK-SIGMA, Denmark) were used to prepare the enzymatic hydrolysates, evaluating two different enzyme–substrate concentrations: 1% w/w and 5% w/w. Before enzymatic hydrolysis, the substrate was sterilized. Subsequently, 100 g of pollen was added to a 250 mL flask suspended in 100 mL of water. The mixture was homogenized and sterilized at 121 °C for 15 min. The sterile substrate was then adjusted to the optimal pH with 0.1 N NaOH. Throughout the hydrolysis process, the temperature was manually maintained at 60 °C (C-MAG HS 7 heating plates, IKA, Staufen im Breisgau, Germany), with continuous agitation at 200 rpm. Hydrolysis was terminated by boiling for 2 min, after which the hydrolysates were filtered under vacuum to remove residues. Both the supernatant and residue were collected separately and kept refrigerated until characterization. Enzyme blanks were additionally obtained for each treatment under the same digestion conditions, but in the absence of the sample [16]. Each hydrolysis treatment was performed in triplicate using independently prepared pollen substrates.

2.6. Description of Physicochemical Analysis Methods

Physicochemical analyses of fresh, fermented, and hydrolyzed pollen were carried out according to the official methods of analysis approved by the Official Methods of Analysis (AOAC) [24]. Moisture content (method 925.10) was measured in an oven at 105 °C until the weight did not vary more than 0.1%; lipid content (method 920.39) was quantified by Soxhlet; dietary fiber (method 978.10) was analyzed from dried and defatted pollen obtained after moisture and lipid determinations, following the steps of acid digestion, washing, alkaline digestion, washing, and defatting; ash content (method 923.03) was measured by calcination of the organic matter in a muffle furnace at 550 °C until complete mineralization; whereas protein content (method 984.13) was determined by the Kjeldahl method with the Winkler modification. Finally, total carbohydrate content was calculated according to AOAC method 979.23. Total solids were determined gravimetrically, and caloric content was estimated using the Atwater factors.

2.7. Analysis of the Antioxidant Properties of Pollen

Antioxidant activity was determined by analyzing the reduction in DPPH absorbance (DPPH Assay Kit KF01007, BQC REDOX TECHNOLOGIES, Oviedo, Spain), 2,2-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS Antioxidant Capacity Assay Kit KF01002, REDOX TECHNOLOGIES, Oviedo, Spain), and ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP, FRAP Assay Kit KF01003, BQC REDOX TECHNOLOGIES, Spain) using kits following the manufacturer’s instructions. In the case of the FRAP assay, 10 μL of standard or sample was added to each well, followed by 220 μL of FRAP Working Solution in all wells. These wells were then incubated for 4 min at 25 °C. Absorbance was measured at 593 nm (Multiskan™ GO D01521, Thermo Fisher Scientific Oy, Vantaa, Finland). The methodology for the ABTS and DPPH assays was similar to that described above; however, the absorbance of the samples was measured at 734 nm for ABTS and at 517 nm for DPPH. Results were expressed as µM Trolox equivalents/g pollen using calibration curves prepared with Trolox standards for DPPH (expressed as µM Trolox equivalents/g pollen), ascorbic acid (Vitamin C; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) standards for ABTS (expressed as µM Vitamin C equivalents/g pollen), and ferrous sulfate standards for FRAP (expressed as µM Fe2+/g pollen).

2.8. Total Phenolic Content

Total phenolic compounds were quantified using the Folin–Ciocalteu colorimetric method with minor modifications [25]. For this analysis, around 1 g of pollen was weighed into a Falcon tube, to which 10 mL of a methanol–water mixture (1:1 v/v) was added, followed by vortex mixing for 10 s. Subsequently, 0.25 mL of the resulting extract was added to 2.5 mL of distilled water. Then, 0.5 mL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent and 1.0 mL of a sodium carbonate (Na2CO3; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) solution (75 g/L) were added. The samples were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. Finally, absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer. Total phenolic content was expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per gram of pollen (GAE/g pollen). A calibration curve was prepared using concentrations of 0 mg GAE/g pollen (blank), 11.2 mg GAE/g pollen, 22.4 mg GAE/g pollen, 44.8 mg GAE/g pollen, 67.2 mg GAE/g pollen, 89.6 mg GAE/g pollen, and 112 mg GAE/g pollen.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to identify potential differences among fresh, fermented, and hydrolyzed pollen under the various conditions evaluated. Quantitative variables (mean ± standard deviation) were analyzed using Tukey’s test at a 5% and 1% significance levels (p ≤ 0.05 and p ≤ 0.01, respectively).

3. Results and Discussion

The biotechnological transformation of bee pollen from the Montes de María subregion resulted in significant modifications to its physicochemical matrix and functional profile. The results indicated that both bacterial fermentation and enzymatic hydrolysis successfully disrupted the pollen structure, although they enhanced antioxidant properties through distinct mechanisms.

3.1. pH Evolution and Lactic Acid Production

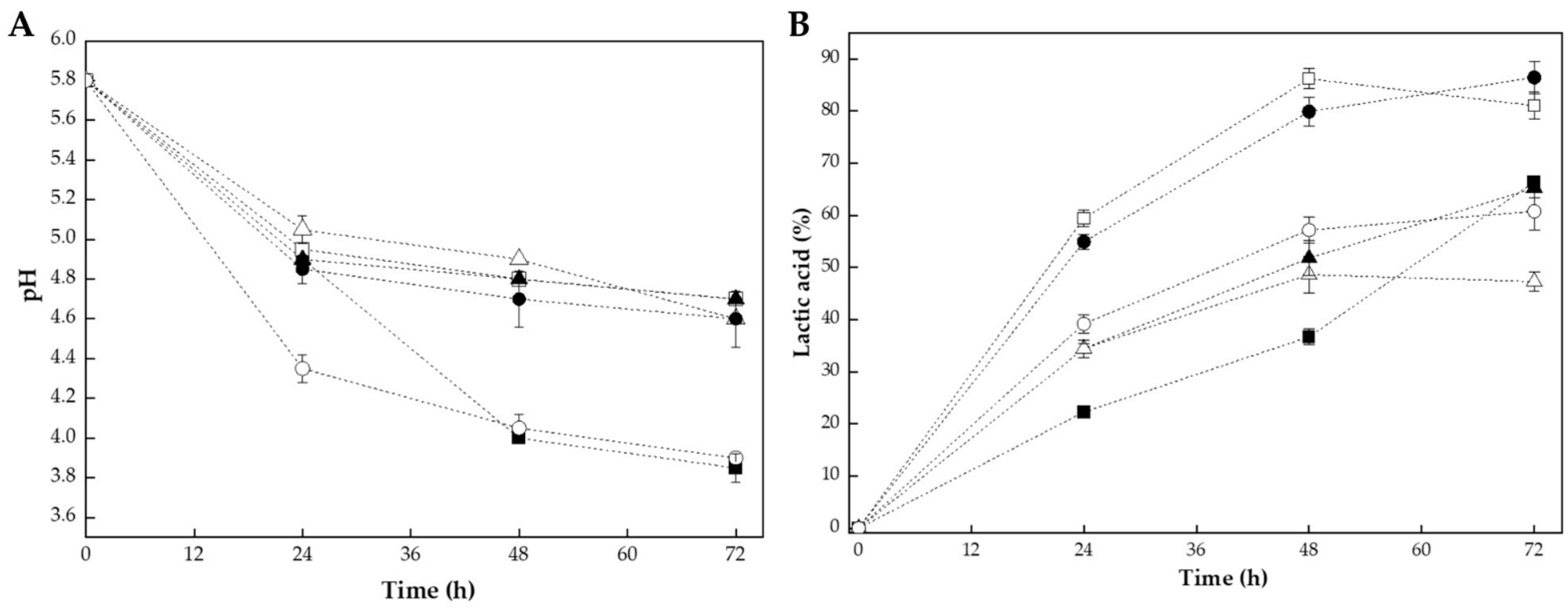

The fermentation of bee pollen with lactic acid bacteria resulted in characteristic changes in pH and titratable acidity over the 72 h incubation period. Figure 1 shows the evolution of pH (see Figure 1A) and lactic acid production (see Figure 1B) during fermentation with L. plantarum, CHOOZIT®, and YO-MIX® at pollen-to-water ratios of 1:1 w/v and 1:2 w/v.

Figure 1.

Evolution of chemical parameters during bee pollen fermentation with lactic acid bacteria over 72 h: (A) pH reduction and (B) titratable acidity increase (expressed as % lactic acid). Key: L. plantarum at pollen water ratios of 1:1 w/v (■) and 1:2 w/v (□) and commercial cultures CHOOZIT (1:1 w/v, ▲; 1:2 w/v, △) and YO-MIX (1:1 w/v, ●; 1:2 w/v, ○).

All fermentation treatments exhibited a progressive decrease in pH accompanied by an increase in lactic acid content, reflecting the typical dynamics of lactic fermentation [9,19]. The initial pH of 5.8 decreased to values ranging from 3.9 to 4.7 after 72 h, depending on the strain and pollen-to-water ratio. The most pronounced pH reduction was observed in L. plantarum 1:1 w/v and YO-MIX® 1:2 w/v treatments, both reaching a final pH of roughly 3.9, representing a decrease of around 1.9 pH units from the initial value (see Figure 1A).

This significant acidification indicated intense metabolic activity and efficient conversion of carbohydrates into lactic acid. The pH reduction pattern followed a typical three-phase fermentation curve. This pattern was consistent with bacterial growth kinetics, where lactic acid bacteria rapidly metabolize available sugars during the exponential growth phase [26].

Beyond the strongest acidification observed for L. plantarum 1:1 and YO-MIX 1:2, the remaining treatments also showed differentiated final pH values. After 72 h, YO-MIX 1:1 reached an intermediate pH of around 4.6, whereas L. plantarum 1:2 and both CHOOZIT fermentations (1:1 and 1:2) stabilized at about 4.7 (see Figure 1A). Thus, although all cultures followed a similar three-phase trajectory, L. plantarum 1:2 and YO-MIX 1:1 clearly acidified the pollen matrix more deeply than the other combinations (see Figure 1B).

The variation in final pH among treatments could be attributed to the combined effects of microbial metabolism and matrix composition. First, the strains differed in their intrinsic acidification capacity: fermentations with L. plantarum and YO-MIX reached lower pH values than those with CHOOZIT, in agreement with studies reporting that L. plantarum and thermophilic lactic consortia often produce higher amounts of lactic acid and achieve deeper acidification in bee pollen and other plant substrates than mixed starter cultures [15,19]. Second, the pollen-to-water ratio modulated both nutrient availability and buffering; in most cases, the 1:2 ratio led to less pronounced pH decreases than the corresponding 1:1 fermentations (e.g., LP 1:2 vs. LP 1:1 and CZT 1:2 vs. CZT 1:1), indicating that acid formed in more diluted systems was partially neutralized by the larger aqueous phase and soluble buffering components, as described for highly buffered plant matrices [27]. YO-MIX 1:2 was an exception, combining rapid early acidification with a final pH comparable to its 1:1 counterpart, which suggested that this consortium kept high metabolic activity and efficient carbohydrate utilization even under dilution, in line with its strong performance reported for plant-based fermentations inoculated with thermophilic lactic cultures. Overall, CHOOZIT (1:1 and 1:2), YO-MIX 1:1, and LP 1:2 exhibited the smallest net pH reductions, reflecting a more moderate acidification capacity and a stronger influence of matrix buffering in these culture–ratio combinations.

The evolution of titratable acidity (see Figure 1B) corroborated the acidification patterns observed in pH and revealed clear strain and ratio-dependent differences in lactic acid production. After 24 h, fermentations with L. plantarum 1:2 and YO-MIX 1:1 already displayed the highest lactic acid levels (59% and 55%, respectively), followed by CHOOZIT 1:1 and 1:2 (34%) and YO-MIX 1:2 (39%); while L. plantarum 1:1 showed the slowest onset of acid production (22%). Between 24 and 48 h, lactic acid accumulation remained most pronounced in LP 1:2 and YO-MIX 1:1, which reached 86% and 80%, respectively. Meanwhile, YO-MIX 1:2 and CHOOZIT (1:1 and 1:2) increased more moderately (57%, 52% and 49%), and LP 1:1 rose to 37%. At 72 h, YO-MIX 1:1 and LP 1:2 converged as the most acidified systems (86% and 81% lactic acid), while LP 1:1 (which had a pronounced increase in the last measurement interval), YO-MIX 1:2 and CHOOZIT 1:1 (65%) attained intermediate values (66% and 61%). Finally, CHOOZIT 1:2 slowed its lactic acid production during this time interval and ended up as the treatment with the lowest until reaching 47%. These magnitudes and acidification patterns were consistent with previous reports in which lactic acid bacterium fermentations of bee pollen and other plant matrices produced substantial lactic acid accumulation over 48–72 h, with strain-dependent differences in acidification efficiency [14,19].

In contrast to enzymatic hydrolysis, which achieves matrix disruption through direct proteolytic action within 2–6 h [18], bacterial fermentation requires extended processing times (e.g., 72 h) to achieve comparable structural modifications. However, the acidification observed during fermentation confers additional functional benefits not achievable through enzymatic treatment alone, including enhanced microbiological stability due to reduced pH, the production of organic acids with antimicrobial activity, and the potential generation of probiotic metabolites [14]. These findings suggested that the selection between fermentation and enzymatic hydrolysis should be guided by the specific functional attributes required for the target application.

When considered together with the pH results, titratable acidity profiles confirmed that treatments generating the largest lactic acid loads (LP 1:2 and YO-MIX 1:1) and those combining high acidity with the lowest terminal pH (LP 1:1 and YO-MIX 1:2) were responsible for the strongest overall acidification of the pollen matrix. In contrast, the CHOOZIT fermentations showed both lower lactic acid accumulation and smaller net pH decreases, while LP 1:2 combined high lactic acid levels with a comparatively higher final pH, pointing to a stronger buffering effect of the matrix in this condition. This hierarchy among treatments agreed with studies indicating that L. plantarum and thermophilic lactic consortia often achieve deeper acidification of bee pollen and related plant substrates than other starter cultures, and supports the interpretation that cumulative lactic acid production is the main driver of the acidification patterns seen in Figure 1A [14,19].

3.2. Proximate Composition of Fermented and Hydrolyzed Bee Pollen

The biotechnological processing of tropical bee pollen resulted in significant, strain- and concentration-dependent variations in its proximate composition, with key changes observed in moisture, protein, carbohydrate content, and caloric value (see Table 1). Statistical analysis using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test revealed that both fermentation and enzymatic hydrolysis significantly (p ≤ 0.05) altered the nutritional profile of bee pollen, although through distinct mechanisms.

Table 1.

Proximate composition of bee pollen after bacterial fermentation and enzymatic hydrolysis.

Fermentation significantly increased (p ≤ 0.05) moisture content from 32% in the unfermented pollen substrate (UPS) to values ranging from 48% to 71% across all fermented treatments. As can be seen in Table 1, the highest moisture levels were observed in the 1:2 w/v treatments, which was expected due to the higher initial water addition. However, even the 1:1 w/v treatments showed substantial moisture increases, indicating that the fermentation process promoted water retention through the production of hygroscopic metabolites such as lactic acid and exopolysaccharides. These findings were consistent with previous reports on lactic acid fermentation of bee pollen, where moisture increases of 40–65% have been documented during solid-state fermentation processes [9]. Enzymatic hydrolysis also increased moisture content in a concentration-dependent manner, with Neutrase treatments exhibiting significantly higher moisture (p ≤ 0.01) than Protamex at 1%. The greater moisture retention in Neutrase-hydrolyzed samples could be attributed to the more extensive protein hydrolysis, which exposes hydrophilic amino acid residues that bind water molecule [16].

Total solid content inversely mirrored moisture trends, as expected from the complementary relationship between these parameters. Fermented samples showed total solids ranging from 29% (YM 1:2) to 52% (CZT 1:1), compared to 54% in UPS. The significance level was stronger for enzymatic hydrolysis (p ≤ 0.01) versus fermentation (p ≤ 0.05), indicating more consistent compositional changes through enzymatic processing. This observation agreed with the controlled nature of enzymatic reactions compared to the variable metabolic activity during microbial fermentation.

Protein content exhibited highly significant variation across both processing methods (fermentation: p ≤ 0.01; hydrolysis: p ≤ 0.05), decreasing from 29.1% in UPS to 10.5–19.5% in fermented samples and 7.2–11.2% in hydrolyzed samples. The decrease in crude protein measured in the solid matrix did not represent a nutritional loss but rather reflected the solubilization of structural proteins into bioavailable peptides and free amino acids that partition into the liquid fraction during analysis. Studies on bee pollen fermentation have demonstrated that while total protein content in the solid matrix decreases, there is a corresponding significant increase in free amino acids (up to 4.8-fold) and soluble peptides in the liquid fraction [28]. L. plantarum and commercial proteases (Protamex® and Neutrase®) degrade the rigid pollen exine and break down complex structural proteins into more digestible, small-molecule peptides [29]. The lowest protein values in enzymatic treatments could be attributed to the extensive proteolytic activity of Neutrase on internal pollen proteins, releasing them as soluble nitrogen compounds. This transformation has been confirmed by SDS-PAGE analysis, which shows the disappearance of high-molecular-weight protein bands and the appearance of low-molecular-weight peptide fractions after enzymatic treatment [16].

Comparing the proximate composition changes induced by both biotechnological approaches revealed distinct modification patterns. Bacterial fermentation produced more variable compositional changes depending on the strain and pollen-to-water ratio, whereas enzymatic hydrolysis yielded more consistent and predictable modifications across treatments [18]. The higher moisture retention observed in enzymatic hydrolysates (50–68%) compared to fermented samples at equivalent ratios suggested that proteolytic action exposed a greater number of hydrophilic binding sites. Furthermore, the more pronounced protein reduction in enzymatic treatments (7.2–11.2%) compared to fermentation (10.5–19.5%) indicated more extensive protein fragmentation, which may enhance the bioavailability of amino acids and peptides [16]. These differential effects on the nutritional matrix underscore the importance of selecting the appropriate processing method based on the desired functional and nutritional outcomes.

Lipid content showed no statistically significant differences among treatments within each processing category (p ˃ 0.05). Values ranged from 1.5% (CZT 1:1) to 8.1% (BS) in fermented samples and from 1.4% (PHP 1%) to 2.4% (PHP 5%) in hydrolyzed samples. The lack of significant variation suggested that both fermentation and enzymatic hydrolysis primarily target protein and carbohydrate fractions rather than lipid components. The relatively stable lipid content is advantageous for preserving the polyunsaturated fatty acid profile of bee pollen, which contributes to its nutritional and health-promoting properties [5,20].

Ash content decreased from 4.9% in UPS to 1.2–1.8% in fermented samples and 1.2–1.4% in hydrolyzed samples, although these differences were not statistically significant within treatment groups. The apparent reduction in ash percentage could be attributed to the dilution effect from increased moisture content and changes in the solid matrix composition during processing, rather than actual mineral loss. The mineral fraction of bee pollen, which includes essential elements such as K, P, Ca, Mg, and Zn, generally remains stable during biotechnological processing [14].

Carbohydrate content showed significant variation across both processing methods (p ≤ 0.05). In fermented samples, carbohydrates ranged from 16% (CZT 1:2) to 35% (CZT 1:1), compared to 41% in UPS. The reduction in carbohydrate content during fermentation was consistent with the utilization of fermentable sugars by lactic acid bacteria as carbon and energy sources, producing lactic acid as the primary metabolic end product [19]. Among enzymatic treatments, PHP 1% kept the highest carbohydrate content, while NHP 5% showed the lowest (see Table 1). The carbohydrate reduction in Neutrase treatments likely reflects the combined effects of protein hydrolysis exposing previously bound carbohydrates and the metabolic activity during the hydrolysis process. These findings were consistent with literature reports showing that fermentation and enzymatic processing induce substantial modifications in the carbohydrate composition of bee pollen [12].

Energy values, calculated using Atwater factors, decreased significantly from 317 kcal/100 g in UPS to 122 kcal/100 g–207 kcal/100 g in fermented samples and 130 kcal/100 g–201 kcal/100 g in hydrolyzed samples (p ≤ 0.05). The lowest caloric values were observed in the high-moisture 1:2 w/v fermentation treatments and in Neutrase hydrolysates. Notably, PHP 1% treatment kept the highest caloric value among enzymatic treatments, comparable to LP 1:1. This preservation of energy value, combined with its superior antioxidant performance, positioned PHP 1% as the optimal treatment for applications requiring both enhanced bioactivity and nutritional stability.

The choice between fermentation and enzymatic hydrolysis depends on the intended application. Fermentation with L. plantarum or commercial cultures (CHOOZIT®, YO-MIX®) offers the additional benefit of probiotic properties and the generation of bioactive metabolites through microbial secondary metabolism. However, the significant moisture increase, and caloric reduction could limit shelf stability and require additional drying steps. Enzymatic hydrolysis, particularly with Protamex® at 1% w/w, provides a more controlled and reproducible approach that maximizes bioactive compound release while preserving nutritional stability. The PHP 1% treatment represents the optimal compromise, achieving enhanced antioxidant activity without excessive caloric loss, making it suitable for functional food formulations and nutraceutical applications.

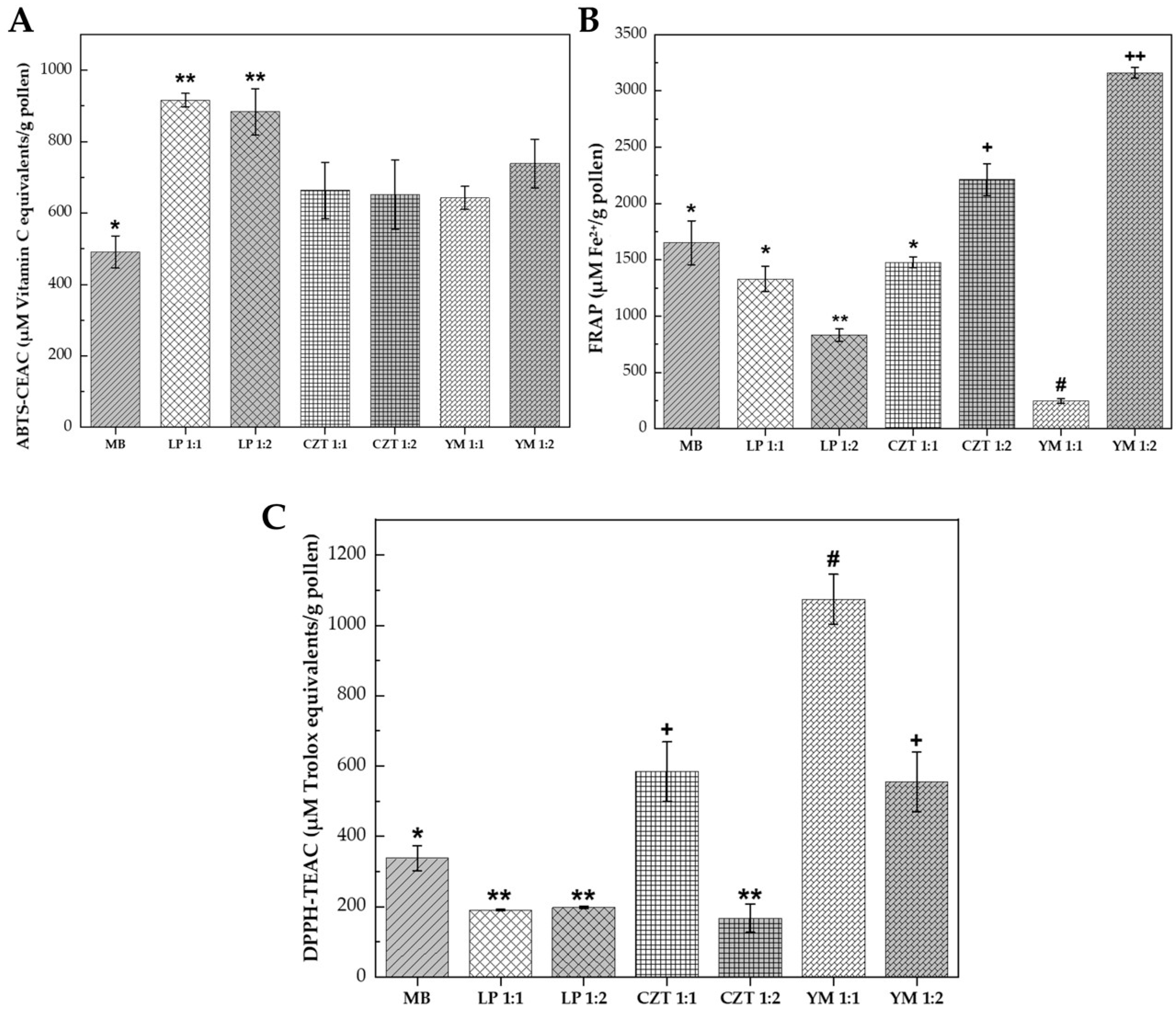

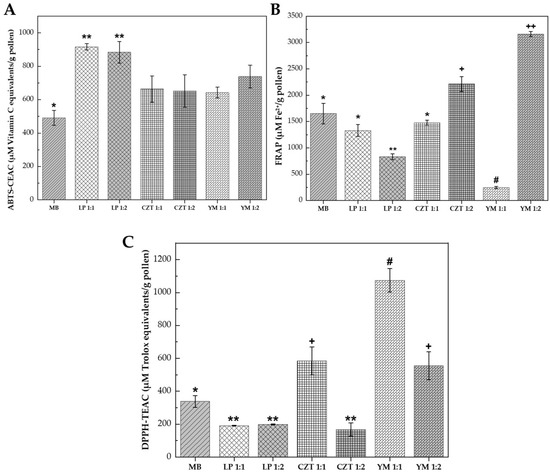

3.3. Antioxidant Activity of Fermented and Hydrolyzed Bee Pollen

The fermentation of bee pollen with lactic acid bacteria resulted in strain-specific and ratio-dependent modifications to its antioxidant profile, as evaluated through three complementary assays: ABTS radical scavenging capacity, ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP), and DPPH radical scavenging activity (see Figure 2). The divergent responses observed across these assays reflected the distinct mechanisms by which different antioxidant compounds interact with free radicals, highlighting the complexity of the antioxidant matrix generated during fermentation [30].

Figure 2.

Antioxidant activity of bee pollen fermented with lactic acid bacteria for 72 h. Key: (A) ABTS radical cation scavenging capacity expressed as µM Vitamin C equivalents/g pollen. (B) Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) expressed as µM Fe2+/g pollen. (C) DPPH radical scavenging activity expressed as µM Trolox equivalents/g pollen. Treatments: BS, unfermented blank sample (control); LP 1:1 and LP 1:2, fermented with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum at pollen:water ratios of 1:1 w/v and 1:2 w/v, respectively; CZT 1:1 and CZT 1:2, fermented with CHOOZIT® TM 82 LYO 50 DCU at pollen:water ratios of 1:1 w/v and 1:2 w/v, respectively; YM 1:1 and YM 1:2, fermented with YO-MIX® 885 LYO 50 DCU at pollen:water ratios of 1:1 w/v and 1:2 w/v, respectively. Bars represent mean ± standard deviation (n = 2). Different symbols (*, **, +, #, ++) indicate statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) according to Tukey’s test following one-way ANOVA.

Fermentation significantly enhanced ABTS scavenging capacity compared to the unfermented control (see Figure 2A). The unfermented blank sample (BS) exhibited the lowest activity and was statistically different (p ≤ 0.05) from all fermented samples. Both L. plantarum treatments demonstrated the highest ABTS scavenging activity, forming a superior statistical group that was significantly higher than both the control and the commercial cultures. This 1.9-fold increase in ABTS scavenging capacity indicates that L. plantarum fermentation is particularly effective at releasing or generating hydrophilic antioxidant compounds capable of neutralizing the ABTS cation radical.

The commercial cultures CHOOZIT® and YO-MIX® showed intermediate ABTS values. CZT 1:1 (663 µM Vitamin C equivalents/g pollen) and CZT 1:2 (652 µM Vitamin C equivalents/g pollen) exhibited similar activities, while YM 1:1 (642 µM Vitamin C equivalents/g pollen) and YM 1:2 (739 µM Vitamin C equivalents/g pollen) showed comparable performance, with increases of 31–50% over the control. These findings agreed with previous studies demonstrating that lactic acid fermentation enhances the release of phenolic compounds from the pollen matrix through cell wall degradation and enzymatic biotransformation [31].

The FRAP assay revealed substantial strain-dependent variability in electron-donating capacity (see Figure 2B). Remarkably, the YO-MIX® 1:2 treatment achieved the highest reducing power (3160 µM Fe2+/g pollen), representing a 1.9-fold increase compared to the unfermented control (1650 µM Fe2+/g pollen) and showing a statistically significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) from all other treatments. In contrast, the YM 1:1 treatment exhibited the lowest FRAP value (244 µM Fe2+/g pollen), which was lower than the unfermented blank sample. This 13-fold difference between the two YO-MIX® ratio treatments suggested that the pollen-to-water ratio modulates the metabolic pathways of this thermophilic consortium, potentially affecting the balance between phenolic compound synthesis and degradation.

The CHOOZIT® treatments showed a clear ratio-dependent effect: CZT 1:2 (2211 µM Fe2+/g pollen) exhibited the second highest FRAP activity after YM 1:2, representing a 1.3-fold increase over the control, while CZT 1:1 (1477 µM Fe2+/g pollen) showed values slightly below the control. The L. plantarum treatments showed variable FRAP responses: LP 1:1 (1330 µM Fe2+/g pollen) exhibited activity similar to the control, while LP 1:2 (829 µM Fe2+/g pollen) showed a 50% reduction compared to the unfermented blank. This pattern indicated that while L. plantarum exceled at ABTS scavenging, it did not consistently enhance ferric ion reduction and may have even reduced this capacity depending on the substrate concentration. These findings were consistent with reports by Miłek et al. [28], who observed opposite trends between FRAP and DPPH assays in fermented bee pollen, attributing this to the differential reactivity of specific phenolic compounds toward different radical species.

The DPPH assay revealed contrasting patterns compared to the ABTS results (see Figure 2C). The YO-MIX® 1:1 treatment demonstrated the highest DPPH scavenging capacity (1074 µM Trolox equivalents/g pollen), representing a 3.2-fold increase over the unfermented control (338 µM Trolox equivalents/g pollen) and showing a statistically significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) from all other treatments. Unexpectedly, the L. plantarum treatments (LP 1:1: 191 µM Trolox equivalents/g pollen; LP 1:2: 198 µM Trolox equivalents/g pollen) exhibited lower DPPH scavenging values than the unfermented blank, representing a 43–44% decrease. This suggests that while L. plantarum fermentation enhances ABTS-reactive compounds, it consumes or structurally transforms specific native compounds that are highly reactive toward the DPPH radical.

This apparent paradox between ABTS and DPPH responses could be explained by the different mechanisms underlying these assays. The DPPH assay measures hydrogen atom transfer capacity in a lipophilic environment, while ABTS measures single electron transfer capacity in a hydrophilic system [32]. The CHOOZIT® 1:1 treatment showed elevated DPPH activity (584 µM Trolox equivalents/g pollen), representing a 1.7-fold increase over the control, while CZT 1:2 exhibited reduced values (168 µM Trolox equivalents/g pollen) similar to the LP treatments. The YM 1:2 treatment showed intermediate activity (556 µM Trolox equivalents/g pollen). This pattern indicated that the antioxidant profile shift during fermentation was not simply a matter of increased or decreased activity, but rather a qualitative transformation of the antioxidant compound profile. Adaškevičiūtė et al. [19] reported similar findings, noting that fermentation can decrease DPPH radical scavenging activity while simultaneously increasing total phenolic content, due to the structural modification of flavanones and dihydrochalcones that respond to Folin–Ciocalteu but not to DPPH.

The divergent antioxidant responses observed across the three assays can be attributed to several concurrent mechanisms during lactic acid fermentation. First, the acidification of the pollen matrix (pH decrease from 5.8 to 3.9–4.7) promoted the release of bound phenolic compounds through hydrolysis of ester bonds linking phenolic acids to cell wall polysaccharides [14]. Second, bacterial β-glucosidases catalyzed the deglycosylation of flavonoid glycosides to their corresponding aglycones, which typically exhibit higher antioxidant activity but different radical specificity [12]. Third, the metabolic activity of lactic acid bacteria generated new bioactive compounds, including short-chain fatty acids, exopolysaccharides, and bacteriocins, that contribute to the overall antioxidant capacity [15].

The superior ABTS scavenging of L. plantarum fermentation suggested efficient release of water-soluble phenolic acids (caffeic, ferulic, and p-coumaric acids), while the exceptional DPPH activity of YO-MIX® 1:1 indicated generation of hydrogen-donating compounds, possibly including phenolamides and flavonoid aglycones. The variability in FRAP responses with YM 1:2 showing a 1.9-fold increase while YM 1:1 showed a 6.8-fold decrease reflected the complex balance between synthesis and degradation of electron-donating compounds during fermentation, which is highly sensitive to substrate concentration. These results support the recommendation by Dudonne et al. [33] that multiple antioxidant assays should be employed to comprehensively characterize the antioxidant profile of fermented products, as each method reflects different aspects of antioxidant capacity.

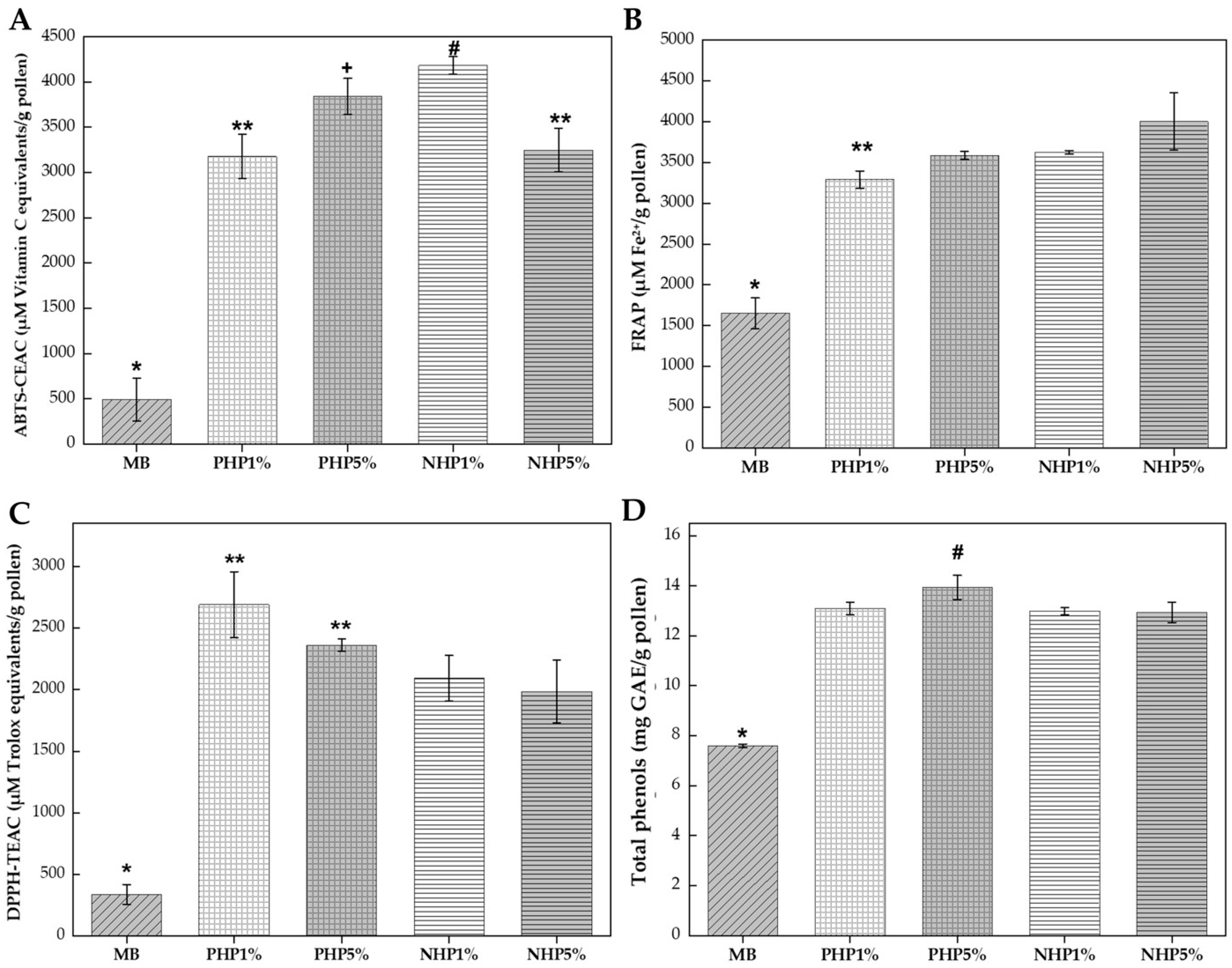

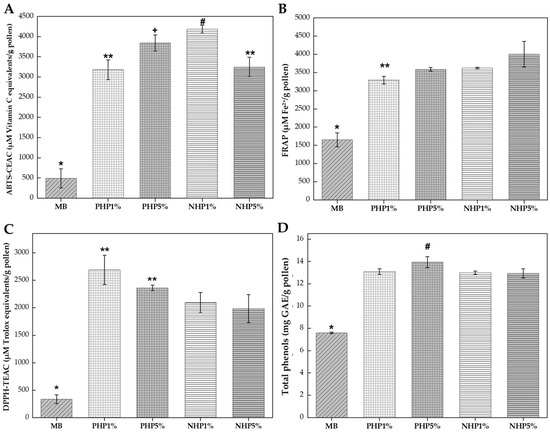

3.4. Antioxidant Activity and Total Phenolic Content of Enzymatically Hydrolyzed Pollen

As can be seen in Figure 3, enzymatic hydrolysis with Protamex® and Neutrase® proteases resulted in substantial and consistent enhancements of antioxidant capacity across all evaluated assays, demonstrating a more uniform improvement compared to the variable responses observed during fermentation. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05) revealed that all enzymatic treatments significantly differed from the unhydrolyzed control, confirming the effectiveness of proteolytic processing for enhancing bee pollen bioactivity.

Figure 3.

Antioxidant activity and total phenolic content of enzymatically hydrolyzed bee pollen. Key: (A) ABTS radical cation scavenging capacity expressed as µM Vitamin C equivalents/g pollen. (B) Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) expressed as µM Fe2+/g pollen. (C) DPPH radical scavenging activity expressed as µM Trolox equivalents/g pollen. (D) Total phenolic content expressed as mg gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per gram of pollen. Treatments: BS, unhydrolyzed blank sample (control); PHP 1% and PHP 5%, pollen hydrolyzed with Protamex® at 1% and 5% enzyme-to-substrate ratio (w/w), respectively; NHP 1% and NHP 5%, pollen hydrolyzed with Neutrase® at 1% and 5% enzyme-to-substrate ratio (w/w), respectively. Different symbols (*, **, +, #) indicate statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) according to Tukey’s test following one-way ANOVA.

All enzymatic hydrolysis treatments improved ABTS scavenging capacity compared to the unhydrolyzed blank (see Figure 3A). The BS control exhibited the lowest activity (491 µM Vitamin C equivalents/g pollen) and was significantly different (p ≤ 0.05) from all hydrolyzed samples. The NHP 1% treatment achieved the highest ABTS value (4182 µM Vitamin C equivalents/g pollen), representing an 8.5-fold increase over the control, followed by PHP 5% (3840 µM Vitamin C equivalents/g pollen), NHP 5% (3248 µM Vitamin C equivalents/g pollen), and PHP 1% (3178 µM Vitamin C equivalents/g pollen). Statistical analysis revealed that NHP 1% differed significantly (p ≤ 0.05) from all other treatments, while PHP 5% formed a distinct intermediate group.

The higher performance of Neutrase® at 1% concentration suggested that moderate enzymatic action optimizes the release of ABTS-reactive compounds without excessive degradation of antioxidant peptides. Proteases such as Protamex® and Neutrase® not only hydrolyze storage proteins but also physically disrupt the structural protein matrix of the pollen exine and intine, effectively releasing internal phenolic compounds, particularly glycosylated flavonoids and hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives that exhibit strong ABTS radical scavenging activity [16]. This mechanism was consistent with findings by Dong et al. [29], who demonstrated that Protamex® hydrolysis combined with ultrasonication achieved significant cell wall disruption in rape bee pollen, enhancing the extractability of intracellular bioactive compounds.

All enzymatic treatments significantly improved ferric reducing power compared to the unhydrolyzed control (see Figure 3B). The BS showed the lowest FRAP value (1650 µM Fe2+/g pollen), while the hydrolyzed samples achieved substantially higher values. The NHP 5% treatment exhibited the highest FRAP value (4002 µM Fe2+/g pollen), representing a 2.4-fold enhancement over the control. The NHP 1% treatment showed similar activity (3622 µM Fe2+/g pollen; 2.19-fold increase), followed by PHP 5% (3585 µM Fe2+/g pollen; 2.17-fold increase) and PHP 1% (3290 µM Fe2+/g pollen; 1.99-fold increase). Statistical analysis indicated that NHP 5% differed significantly (p ≤ 0.05) from the Protamex® treatments, while PHP 5% and NHP 1% formed a homogeneous subgroup. This consistent enhancement across enzyme types and concentrations indicates that proteolytic hydrolysis universally improves electron-donating capacity, likely through the release of phenolic compounds and generation of antioxidant peptides containing electron-rich amino acid residues (tyrosine, tryptophan, histidine) [34].

The DPPH assay revealed a pronounced difference between Protamex® and Neutrase® hydrolysates (see Figure 3C). The PHP 1% treatment exhibited the highest DPPH scavenging capacity (2689 µM Trolox equivalents/g pollen), representing an 8-fold increase over the unhydrolyzed control (338 µM Trolox equivalents/g pollen) and showing a statistically significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) from the Neutrase® treatments (p ≤ 0.05). The PHP 5% treatment also demonstrated high activity (2362 µM Trolox equivalents/g pollen; 6.98-fold increase), forming a statistical group with PHP 1%. In contrast, the Neutrase® hydrolysates showed lower but still substantial improvements: NHP 1% (2091 µM Trolox equivalents/g pollen; 6.2-fold increase) and NHP 5% (1985 µM Trolox equivalents/g pollen; 5.9-fold increase).

The higher DPPH scavenging of Protamex® hydrolysates indicated that this enzyme preferentially generated low-molecular-weight peptides and free amino acids with superior hydrogen-donating capability, a characteristic feature of DPPH activity [17]. Protamex®, being a broad-spectrum endoprotease from Bacillus spp., produced peptide fragments of varying sizes that may include specific sequences with enhanced radical scavenging activity. Pasarin and Rovinaru [17] reported that Protamex® hydrolysis of multifloral bee pollen achieved degrees of hydrolysis of 9–10%, generating soluble peptides with DPPH IC50 values decreased from 2.8 mg/mL to 1.6 mg/mL. Our results corroborate these findings and suggest that the 1% enzyme concentration represents the optimal balance between protein fragmentation and preservation of bioactive peptide sequences.

All enzymatic treatments significantly increased the extractable total phenolic content compared to the unhydrolyzed control (p ≤ 0.05) (see Figure 3D). The BS contained (7.6 mg GAE/g pollen), while hydrolyzed samples ranged from 13.0 mg GAE/g pollen to 14.0 mg GAE/g pollen, representing increases of 70–84%. The PHP 5% treatment achieved the highest phenolic recovery (14.0 mg GAE/g pollen; 84% increase), followed by PHP 1% (13.1 mg GAE/g pollen; 72% increase), NHP 1% (13.0 mg GAE/g pollen; 71% increase), and NHP 5% (13.0 mg GAE/g pollen; 70% increase). Statistical analysis revealed that except PHP5%, all treatments formed a homogeneous group with no significant differences among them (p ˃ 0.05), indicating that all treatments were equally effective at releasing bound phenolic compounds from the pollen matrix regardless of enzyme type or concentration.

The consistent enhancement in phenolic content across treatments confirmed that enzymatic action effectively disrupts the sporopollenin and cell wall structures, releasing phenolic compounds that were previously bound to proteins and polysaccharides [5]. This finding aligns with Li et al. [18], who reported that deep enzymatic hydrolysis of bee pollen with multiple enzymes increased total phenolic content from 8.2 mg GAE/g to 12.7 mg GAE/g and improved antioxidant potential through the degradation of cell wall components. The relatively uniform phenolic release despite varying antioxidant activities across enzyme treatments suggested that the type and size of released peptides, rather than the quantity of phenolic compounds, primarily determines the differential responses in DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP assays.

Comparing the two biotechnological approaches, enzymatic hydrolysis demonstrated more consistent and pronounced improvements in antioxidant capacity across all assays compared to fermentation. While fermentation with L. plantarum achieved a maximum 1.9-fold increase in ABTS activity, enzymatic hydrolysis with NHP 1% achieved an 8.52-fold enhancement. Similarly, the maximum DPPH improvement from fermentation (YM 1:1: 3.2-fold) was exceeded by enzymatic hydrolysis (PHP 1%: 8-fold). For FRAP, both approaches achieved comparable maximum enhancements (YM 1:2: 1.9-fold vs. NHP 5%: 2.4-fold), although the variability within fermentation treatments was substantially higher. This superior and more consistent performance of enzymatic treatment can be attributed to the direct and controlled action of proteases on the pollen matrix, which bypasses the metabolic variability inherent in microbial fermentation [35].

However, fermentation offers unique advantages not captured by antioxidant assays alone, including the generation of probiotic metabolites, production of bacteriocins with antimicrobial activity, and potential prebiotic effects [8]. The YO-MIX® 1:2 treatment, despite achieving only moderate ABTS enhancement (1.5-fold), demonstrated excellent FRAP activity (3160 µM Fe2+/g pollen), approaching the performance of the best enzymatic treatments, suggesting that this thermophilic consortium produces specific electron-donating metabolites that may have distinct biological activities.

The PHP 1% treatment emerges as the optimal choice for applications requiring maximized antioxidant activity with preserved nutritional stability. This treatment achieved the highest DPPH scavenging capacity (2689 µM Trolox equivalents/g pollen; 8-fold increase), substantial ABTS activity (3178 µM Vitamin C equivalents/g pollen; 6.5-fold increase), excellent FRAP enhancement (3290 µM Fe2+/g pollen; 2-fold increase), and significant phenolic content increase (13.1 mg GAE/g pollen; 72% increase), while maintaining the highest caloric value among enzymatic treatments (201.4 kcal/100 g) as reported in Table 1. These combined characteristics position PHP 1% as the superior treatment for functional food formulations requiring both enhanced bioactivity and nutritional preservation, supporting the conclusions of previous studies on the benefits of mild enzymatic hydrolysis for bee pollen valorization [10].

3.5. Limitations and Future Directions

While this study provides novel comparative insights into bee pollen biotransformation, several aspects merit consideration for future research. Antioxidant activity was evaluated using established in vitro chemical assays (DPPH, ABTS, FRAP) that, although widely accepted for screening purposes, do not capture the full complexity of in vivo antioxidant mechanisms. The identification and quantification of individual phenolic compounds through HPLC-MS/MS analysis would enable the characterization of specific bioactive molecules responsible for the observed antioxidant enhancements [19]. Additionally, correlation analysis between phenolic content and individual antioxidant assays would help delineate the relative contributions of phenolic compounds versus bioactive peptides to the enhanced antioxidant capacity. The study focused on polyfloral bee pollen from the Colombian tropical dry forest during a single harvest season; extending this comparative framework to other botanical origins and geographical regions would strengthen the generalizability of our findings. Furthermore, characterization of the bioactive peptides generated during enzymatic hydrolysis would facilitate structure-activity relationship studies [36].

Building upon the optimal processing conditions identified in this study, future research should pursue: (i) HPLC-DAD-MS/MS profiling of phenolic compounds in raw and Protamex®-treated pollen to identify the specific molecules driving antioxidant activity; (ii) mass spectrometric characterization of bioactive peptides and evaluation of their biological activities; (iii) molecular docking studies to elucidate interactions between identified compounds and relevant biological targets such as antioxidant enzymes and inflammatory mediators; (iv) in vitro cellular assays using intestinal epithelial models (e.g., Caco-2) and in vivo studies to validate bioavailability and biological efficacy; (v) evaluation of additional functional properties including antimicrobial activity, anti-inflammatory effects, and prebiotic potential; (vi) scale-up studies with techno-economic analysis to assess industrial feasibility of the optimized Protamex® and YO-MIX® processing protocols.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that both bacterial fermentation and enzymatic hydrolysis effectively enhance the functional properties of bee pollen from the Montes de María tropical dry forest from Colombia, although with distinct outcomes. Fermentation with lactic acid bacteria achieved characteristic acidification and lactic acid accumulation, with strain-specific antioxidant effects: L. plantarum enhanced ABTS scavenging while YO-MIX® 1:1 maximized DPPH activity. However, fermentation responses were highly variable across assays and strains.

Enzymatic hydrolysis produced more consistent and substantially greater improvements: Neutrase® 1% achieved 8.5-fold ABTS enhancement, Protamex® 1% maximized DPPH scavenging (8-fold), and all treatments increased total phenolic content by 70–84%. Among all treatments evaluated, Protamex® hydrolysis at 1% w/w emerged as the optimal strategy, achieving the highest DPPH activity, excellent performance across all antioxidant assays, significant phenolic release, and preserved caloric value.

Based on our findings, we offer the following practical recommendations for researchers and practitioners: (i) for applications requiring maximum antioxidant enhancement with process reproducibility, enzymatic hydrolysis with Protamex® at 1% w/w is recommended; (ii) for products intended to deliver probiotic benefits alongside improved bioactivity, fermentation with YO-MIX® at 1:1 w/v ratio represents the optimal choice; (iii) processing parameters should be optimized according to the target market requirements, considering that enzymatic treatments preserve higher caloric values while fermentation provides natural acidification and extended shelf life; (iv) quality control protocols should incorporate multiple antioxidant assays (DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP) to comprehensively characterize the functional profile of processed bee pollen products.

The divergent responses across DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP assays underscore the importance of multi-assay characterization for processed bee pollen products. While fermentation offers additional probiotic benefits, enzymatic hydrolysis provides a more controlled and reproducible approach for maximizing bioactive compound release. These findings provide scientific evidence for valorizing Colombian tropical bee pollen as a functional food ingredient with enhanced bioavailability and support the development of standardized processing protocols for the nutraceutical industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.F.T., D.C.M.-E. and M.A.-O.; validation, D.C.M.-E., M.A.-O. and J.J.C.; formal analysis, K.M.R.-V., I.L.-F., M.A.-O., J.J.C., B.J.A. and D.C.M.-E.; investigation, K.M.R.-V., I.L.-F., M.A.-O., J.J.C. and D.C.M.-E.; resources, D.F.T., D.C.M.-E. and M.A.-O.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M.R.-V., D.C.M.-E., M.A.-O., J.J.C. and B.J.A.; writing—review and editing, B.J.A., D.C.M.-E., M.A.-O. and J.J.C.; visualization, K.M.R.-V., I.L.-F., B.J.A. and D.C.M.-E.; supervision, D.F.T., D.C.M.-E. and M.A.-O.; project administration, D.F.T., D.C.M.-E. and M.A.-O.; funding acquisition, D.C.M.-E., D.F.T. and M.A.-O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research study was financially supported by the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation (MinCiencias)-Mission-oriented postdoctoral fellowships 934 CT391-2023 (Francisco José de Caldas National Fund for the Financing of Science, Technology and Innovation); Orchid program 935 CT287-2023 (Francisco José de Caldas National Fund for the Financing of Science, Technology and Innovation); and the Universidad Nacional de Colombia (Hermes 59259).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Program for Doctoral Formation (COLCIENCIAS, Grant 757-2016) and the Cooperativa Multiactiva de Apicultores Orgánicos Montes de María (COOAPOMIEL), especially Delia Belén Torres Montes, for their support and project management. D.F.T. and D.C.M.-E. would also like to thank J.T.-M.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Denisow, B.; Denisow-Pietrzyk, M. Biological and therapeutic properties of bee pollen: A review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 4303–4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komosinska-Vassev, K.; Olczyk, P.; Kaźmierczak, J.; Mencner, L.; Olczyk, K. Bee pollen: Chemical composition and therapeutic application. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 297425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, M.G.; Bogdanov, S.; de Almeida-Muradian, L.B.; Szczesna, T.; Mancebo, Y.; Frigerio, C.; Ferreira, F. Pollen composition and standardisation of analytical methods. J. Apic. Res. 2008, 47, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacini, E.; Hesse, M. Pollenkitt–its composition, forms and functions. Flora-Morphol. Distrib. Funct. Ecol. Plants 2005, 200, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalá-Orozco, M.; Lobo-Farfan, I.; Tirado, D.F.; Mantilla-Escalante, D.C. Enhancing the nutritional and bioactive properties of bee pollen: A comprehensive review of processing techniques. Foods 2024, 13, 3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieliszek, M.; Piwowarek, K.; Kot, A.M.; Błażejak, S.; Chlebowska-Śmigiel, A.; Wolska, I. Pollen and bee bread as new health-oriented products: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 71, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mărgăoan, R.; Stranț, M.; Varadi, A.; Topal, E.; Yücel, B.; Cornea-Cipcigan, M.; Campos, M.G.; Vodnar, D.C. Bee collected pollen and bee bread: Bioactive constituents and health benefits. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuluaga-Dominguez, C.M.; Quicazan, M. Effect of fermentation on structural characteristics and bioactive compounds of bee-pollen based food. J. Apic. Sci. 2019, 63, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urcan, A.C.; Criste, A.D.; Dezmirean, D.S.; Bobiș, O.; Bonta, V.; Burtescu, R.F.; Olah, N.-K.; Cornea-Cipcigan, M.; Mărgăoan, R. Enhancing antioxidant and antimicrobial activities in bee-collected pollen through solid-state fermentation: A comparative analysis of bioactive compounds. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damulienė, V.; Kaškonienė, V.; Kaškonas, P.; Mickienė, R.; Maruška, A. Improved Antibacterial Properties of Fermented and Enzymatically Hydrolyzed Bee Pollen and Its Combined Effect with Antibiotics. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 18, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, P.; Xu, L.; Tian, Y.; Lv, M.; Fang, P.; Dong, K.; Lin, Q.; Cao, Z. Effects of synergistic fermentation of tea bee pollen with bacteria and enzymes on growth and intestinal health of Apis cerana cerana. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2025, 8, 100343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Ang, B.; Xue, C.; Wang, Z.; Yin, L.; Wang, T.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, M.; Zhang, W. Insights into the fermentation potential of pollen: Manufacturing, composition, health benefits, and applications in food production. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 143, 104245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulug, S.K.; Jahandideh, F.; Wu, J. Novel technologies for the production of bioactive peptides. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 108, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barta, D.; Cornea-Cipcigan, M.; Margaoan, R.; Vodnar, D. Biotechnological processes simulating the natural fermentation process of bee bread and therapeutic properties—An overview. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 871896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cagno, R.; Filannino, P.; Cantatore, V.; Gobbetti, M. Novel solid-state fermentation of bee-collected pollen emulating the natural fermentation process of bee bread. Food Microbiol. 2019, 82, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuluaga-Domínguez, C.; Castro-Mercado, L.; Cecilia Quicazán, M. Effect of enzymatic hydrolysis on structural characteristics and bioactive composition of bee-pollen. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2019, 43, e13983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasarin, D.; Rovinaru, C. Chemical analysis and protein enzymatic hydrolysis of poly-floral bee pollen. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2022, 35, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhao, J.; Yu, W.; Qiao, Y.; Shu, X.; Ning, F.; Luo, L. Deep enzymatic hydrolysis of bee pollen with multiple enzymes: Improves nutrient release and potential biological activity of bee pollen. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaškevičiūtė, V.; Kaškonienė, V.; Barčauskaitė, K.; Kaškonas, P.; Maruška, A. The impact of fermentation on bee pollen polyphenolic compounds composition. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhraoui, A.; Arrari, F.; Sakhraoui, A.; Aylanc, V.; Rodriguez-Flores, M.S.; Seijo, M.C.; Vilas-Boas, M.; Mejri, M.; Falcão, S.I. Characterization of Multifloral Bee Pollen Collected from Geographically and Botanically Distinct Regions in Tunisia. Foods 2025, 14, 3986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEIBA. Flora y Análisis de Suelos de la Expedición Montes de María. Available online: https://i2d.humboldt.org.co/resource?r=montes-maria_plantas (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Environment, C.M.O. Bosque Seco Tropical. Available online: https://www.minambiente.gov.co/direccion-de-bosques-biodiversidad-y-servicios-ecosistemicos/bosque-seco-tropical/ (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Lobo-Torres, M.; Mantilla-Escalante, D.C.; Anaya, B.J.; Tirado, D.F.; Arenas-Gómez, C.M. Uncovering the Floral Origins of Honey Bee Pollen in Colombian Tropical Dry Forest: A Low-Cost DNA Barcoding Approach Reveals Cactaceae Dominance. Plants 2025, 14, 3652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, W. Official Methods of Analysis, 17th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Folin, O.; Ciocalteu, V. On tyrosine and tryptophane determinations in proteins. J. Biol. Chem 1927, 73, 627–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.; Almqvist, H.; Bao, J.; Wallberg, O.; Lidén, G. Overcoming extended lag phase on optically pure lactic acid production from pretreated softwood solids. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1248441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, B.; Wu, H.; Hou, D.; Wang, S.; Tong, X.; Jiang, Y. Impact of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum on the fermentation quality, nutritional enhancement, and microbial dynamics of whole plant soybean silage. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1565951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miłek, M.; Mołoń, M.; Kula-Maximenko, M.; Sidor, E.; Zaguła, G.; Dżugan, M. Chemical composition and bioactivity of laboratory-fermented bee pollen in comparison with natural bee bread. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.; Gao, K.; Wang, K.; Xu, X.; Zhang, H. Cell wall disruption of rape bee pollen treated with combination of protamex hydrolysis and ultrasonication. Food Res. Int. 2015, 75, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floegel, A.; Kim, D.-O.; Chung, S.-J.; Koo, S.I.; Chun, O.K. Comparison of ABTS/DPPH assays to measure antioxidant capacity in popular antioxidant-rich US foods. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2011, 24, 1043–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaškonienė, V.; Adaškevičiūtė, V.; Kaškonas, P.; Mickienė, R.; Maruška, A. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of natural and fermented bee pollen. Food Biosci. 2020, 34, 100532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumpf, J.; Burger, R.; Schulze, M. Statistical evaluation of DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, and Folin-Ciocalteu assays to assess the antioxidant capacity of lignins. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 233, 123470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudonne, S.; Vitrac, X.; Coutiere, P.; Woillez, M.; Mérillon, J.-M. Comparative study of antioxidant properties and total phenolic content of 30 plant extracts of industrial interest using DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, SOD, and ORAC assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 1768–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Huang, Y.; Islam, S.; Fan, B.; Tong, L.; Wang, F. Influence of the degree of hydrolysis on functional properties and antioxidant activity of enzymatic soybean protein hydrolysates. Molecules 2022, 27, 6110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhuang, Y. Antioxidant and anti-tyrosinase activities of phenolic extracts from rape bee pollen and inhibitory melanogenesis by cAMP/MITF/TYR pathway in B16 mouse melanoma cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maqsoudlou, A.; Sadeghi Mahoonak, A.; Mora, L.; Mohebodini, H.; Ghorbani, M.; Toldrá, F. Controlled enzymatic hydrolysis of pollen protein as promising tool for production of potential bioactive peptides. J. Food Biochem. 2019, 43, e12819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.