Abstract

Glide-snow avalanches pose a major challenge for operational forecasting and local avalanche authorities. Although their key prerequisite, a moist interface between the snowpack and smooth ground, is well known, predicting the timing of glide-snow avalanches remains difficult. We analyzed five seasons of avalanche monitoring data in the Planneralm area of Styria, Austria. Glide-snow avalanche activity in the study area follows typical temporal patterns, with the highest release probability in the early afternoon and peak activity from mid-March to mid-April. Using meteorological data and avalanche observations as input, we trained machine-learning models to predict hours with glide-snow avalanche release. The most significant predictors were the mean air temperature of the preceding 48h, the day of the winter season, the hour of the day, and the decrease in snow height. The combination of those variables suggests a longer-term predisposition toward glide-snow avalanche release, as well as short-term driving factors. Our decision tree model correctly identified the vast majority of avalanche hours (recall 90%) at the cost of a moderate false alarm rate (15%). Our model could support operational glide-snow avalanche forecasting by identifying hours with elevated glide-snow potential that warrant increased attention and may require warnings or temporary closures by local authorities.

1. Introduction

Glide-snow avalanches (Figure 1) appear to be occurring more frequently and across a wider range of locations in recent years. For example, 59% of the avalanche forecasts in the Swiss Alps during winter 2017/18 referred to glide-snow avalanches [1]. Since these avalanches cannot be released artificially and their timing is difficult to predict, they often lead to considerable costs through long-term preventive closures of roads, railway lines, or ski runs. Despite recent advances, forecasting the release of glide-snow avalanches remains a major challenge for both researchers and warning services. In some winters, glide-snow avalanches pose a particularly severe problem for local authorities and forecast centres, e.g., [2]. Reliable and easily accessible tools for assessing days with potential avalanche activity would therefore be of substantial practical value.

Figure 1.

Glide-snow avalanches within the test area, Planneralm. Photos: A. Gobiet and A. Riegler, 2017, GeoSphere Austria.

The conditions required for snow gliding are well known: (i) a smooth snow-soil interface with minimal roughness, such as grass or exposed rock; (ii) a snow temperature of 0 °C at the snow-soil boundary, enabling the presence of liquid water; and (iii) a slope angle exceeding 15°, e.g., [3,4]. Refs. [5,6] further identify a deep snowpack without a distinct weak layer as an additional prerequisite. The liquid water required at the snowpack base can originate from three processes: (i) heat stored in the ground during a warm autumn, which melts the lowermost snow layer after the first substantial snowfall; (ii) melt-water or rain percolating from the snow surface down to the snow-soil interface; and (iii) water generated by melting due to solar radiation, (e.g., on exposed rocks) or supplied by natural springs flowing along the snow-soil boundary, e.g., [3]. These prerequisites highlight that, in addition to meteorological conditions, soil characteristics also exert a strong influence on snow gliding. However, soil properties such as moisture are difficult to measure or even estimate during winter as they require in-situ measurements. In contrast, meteorological data are usually more accessible and therefore more practical for use in predictive tools.

Glide-cracks frequently develop prior to the release of a glide-snow avalanche. However, while some glide-snow avalanches release immediately after the opening of a glide-crack, some glide-cracks do not produce any glide-snow avalanches at all [7]. Consequently, predicting the exact timing of release from the occurrence of glide-cracks remains highly challenging.

Dreier et al. (2016) [8] examined the influence of meteorological conditions on glide-snow avalanche activity on the Dorfberg above Davos, Switzerland, distinguishing between cold- and warm-temperature glide-snow avalanche events. Cold-temperature events are defined as glide-snow avalanches that occur when air temperatures are below freezing, and no form of liquid precipitation has occurred [9]. These two types of glide-snow avalanches are driven by different sources of liquid water—with the latter receiving liquid water from the ground, independent of weather and meteorological conditions. In the Dorfberg area, a significant amount of cold glide-snow avalanches was observed [7,8,10,11]. Dreier et al. (2016) [8] showed that under cold conditions, the primary drivers were minimum air temperature and the amount of new snow prior to release. In contrast, during warm events, air temperature, snow surface temperature (estimated from outgoing long-wave radiation), and a reduction in snow height emerged as the most influential factors.

While many studies, e.g., [7,8,10] concentrate on the well-equipped and well-monitored Dorfberg above Davos, an area very prone to glide-snow avalanche release, comparatively fewer investigations have been conducted in other regions. One other study site is located in Glacier National Park in Montana [12,13]. Peitzsch et al. (2015) [12] studied terrain components and developed a spatial model for identifying areas prone to glide-snow avalanche release. In their study, the glide factor (an index of ground class or surface roughness combined with aspect) was the most important terrain variable influencing the release of snow avalanches. The other variables of importance in their study were the maximum slope and the seasonal sum of solar radiation. Moreover, in the Aosta Valley in Italy, Maggioni et al. (2019) [14] analyzed the soil conditions to find driving factors for glide-snow avalanche release. They found a significant exponential relationship between snow-glide rate and the soil volumetric liquid-water content. Although recent studies have advanced the physical understanding of glide-snow processes, they often rely on complex variables or data that are difficult to obtain in operational settings. As a result, their practical applicability for real-time avalanche forecasting remains limited.

Within this work, we study glide-snow avalanche occurrence at our research site Planneralm (Figure 2) in Styria, Austria [15]. The aim was to assess the local occurrence of glide-snow avalanches, link them to meteorological conditions, and compare our results with results from other sites. The occurrence of cold versus warm glide-snow avalanches, as well as a potential diurnal distribution of glide-snow avalanche occurrence, is important to local avalanche warning authorities and to backcountry travelers and recreationists for risk management. The seasonal distribution of glide-snow avalanche occurrence, on the other hand, might be of interest to future generations to assess a possible shift here due to climate change.

Figure 2.

The Planneralm, Styria, Austria, picture taken from the weather station Großer Rotbühel (station 100). The monitored glide-snow avalanche slopes can be seen on the right. Photo: G. Zenkl, GeoSphere Austria, 2025.

We therefore focused on two main research questions: (1) What are the local temporal patterns of glide-snow avalanche occurrence, including diurnal and seasonal variability? (2) Can data from nearby weather stations support a simple machine-learning model capable of predicting glide-snow avalanche occurrence at our specific location? Moreover, we want to provide the basis for developing a local, operationally practical prediction tool, which would provide substantial value to avalanche commissions and warning services.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

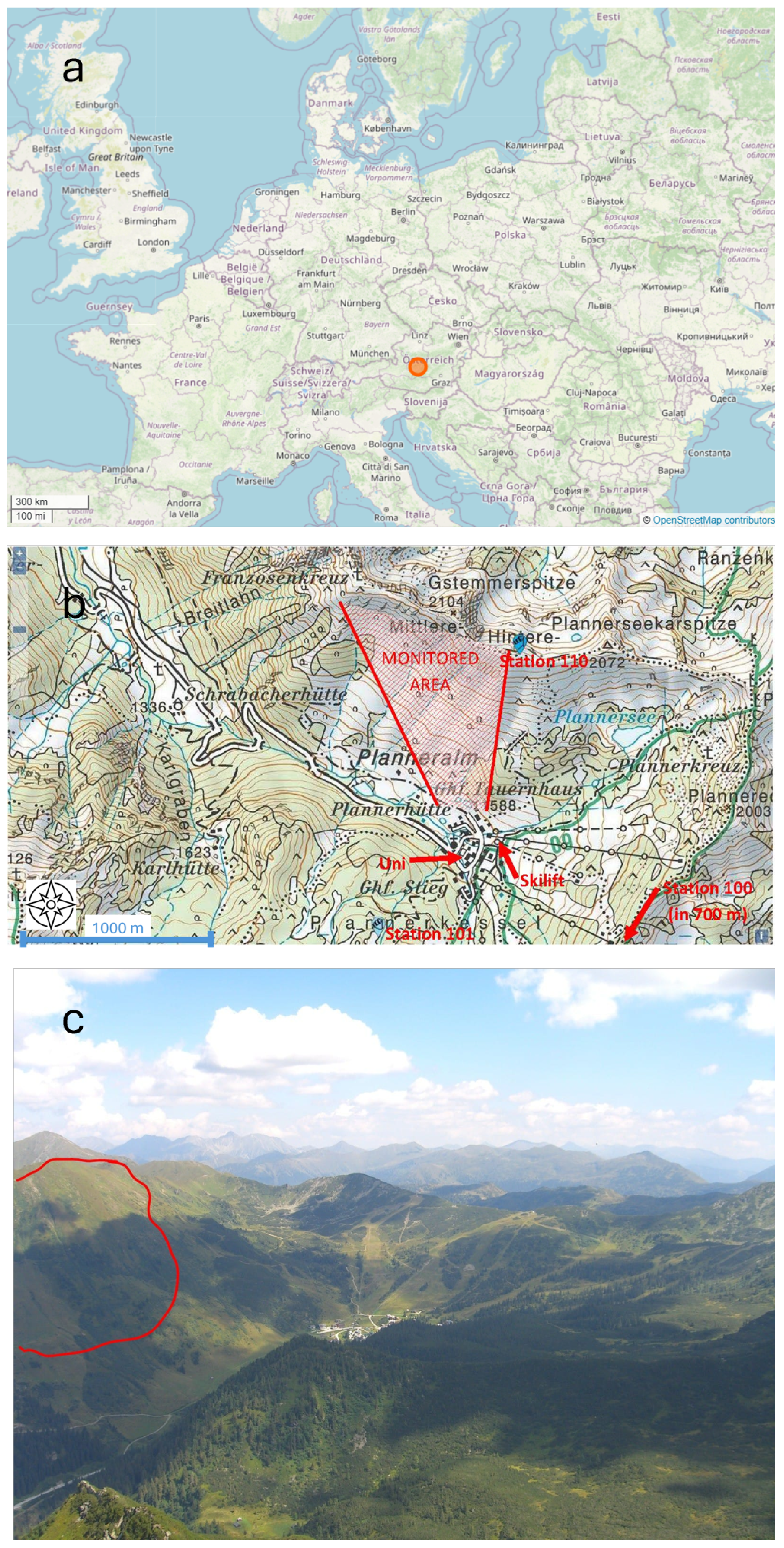

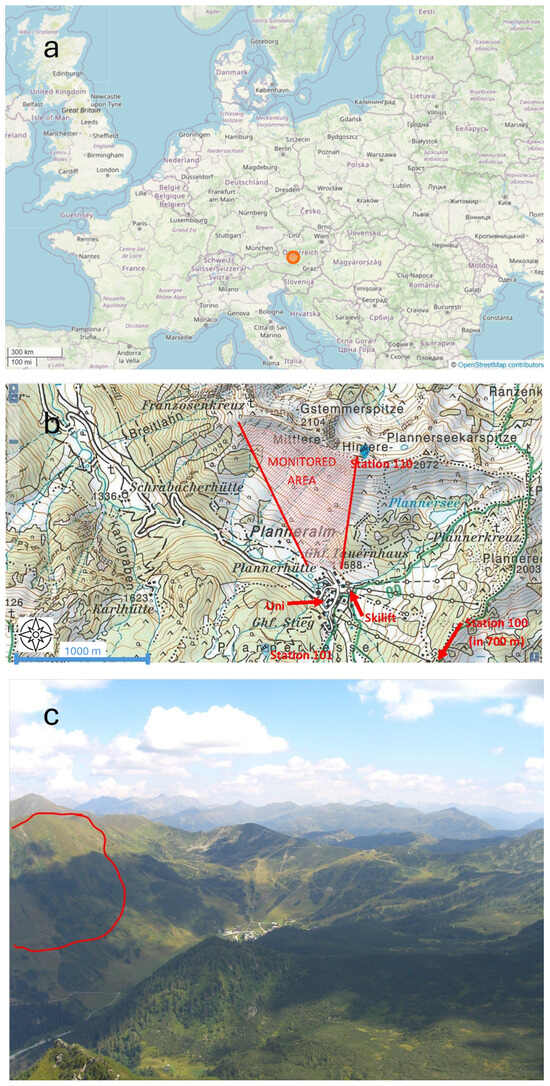

Our study area is the Planneralm in central-western Styria, Austria, at coordinates 47.4040774° N and 14.1996136° E. The Planneralm lies in the Niedere Tauern mountain range, with elevations ranging from 1600 to 2100 m a.s.l. An overview map of central Europe showing the location of the Planneralm is shown in Figure 3a. A detailed map of the study area showing the monitored glide-snow slopes and the locations of the weather stations is shown in Figure 3b.

Figure 3.

(a): Map of Central Europe showing the location of the Planneralm (orange circle) in Styria, Austria. (b): Map of the Planneralm area, the slopes monitored by the camera are marked red, and the locations of the meteorological stations are also indicated. (c): Summer overview photo of the Planneralm area, photographed from the west, the monitored avalanche slopes are indicated by the red outline. Sources: OpenStreetMap contributors, 2025, CC BY-SA 2.0; BEV—Bundesamt für Eich- und Vermessungswesen, Austrian Map, 2025, CC BY 4.0; Wikipedia, 2010, CC BY 2.0.

The monitored slopes exhibit a continuous increase in slope angle, starting from below 10° at the minimum elevation point (within the field area) up to 55°, close to the mountain ridge at roughly 2100 m a.s.l. This coincides with the natural slope spectrum for glide avalanches, which are mostly documented within a range of 30–40° [16] with a minimum inclination of 15° [17].

The observed slopes are mostly oriented to the South- East/South/South-West (Figure 3b). Although glide-snow avalanches can occur on every slope aspect, the named exposures are prone to producing glide-snow avalanche events [12], as those events are influenced by the amount of free water available, which in turn is dependent on solar radiation and air/snow temperature warming [18,19].

The vegetation is characterized by alpine meadows used for summer grazing, interspersed with mountain pines and groups of spruce. Toward the peaks, steeper rocky areas expose mica schist bedrock. Frequent winter avalanches contribute to severe erosion on some slopes, visible in summer as brownish meadow patches. The soil type is non-calcareous brown earth on unconsolidated sediments [20]. An overview summer photograph giving an impression of the geomorphology and vegetation is shown in Figure 3c.

The climate in Styria is dominated by high variability due to its orographic composition. The Planneralm belongs to the region Northside of the Niedere Tauern mountain range. This area comprises the biggest continuous mountain range in Styria, with climate characteristics typical for central alpine regions [21]. The weather fronts originating in the East and West are extenuated by the orographic lift in the more western parts of the Alps before they reach the Niedere Tauern mountain range. Thus, the precipitation frequency is reduced. However, the secondary orographic lift is of high significance as it constitutes a meteorological divide leading to a climatic difference between the North and the South of Styria [21].

2.2. Glide-Snow Avalanche Monitoring

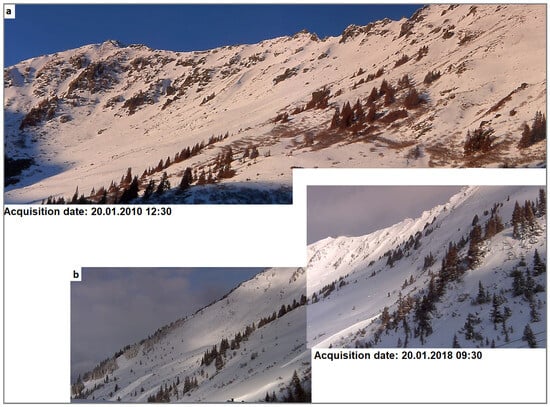

A panoramic camera, operated by GeoSphere Austria and capable of rotating 360°, was used to monitor avalanche-prone slopes and terrain features across multiple winter seasons. The panoramic camera enabled long-term monitoring of glide-snow avalanche activity with a measurement resolution of 30 min.

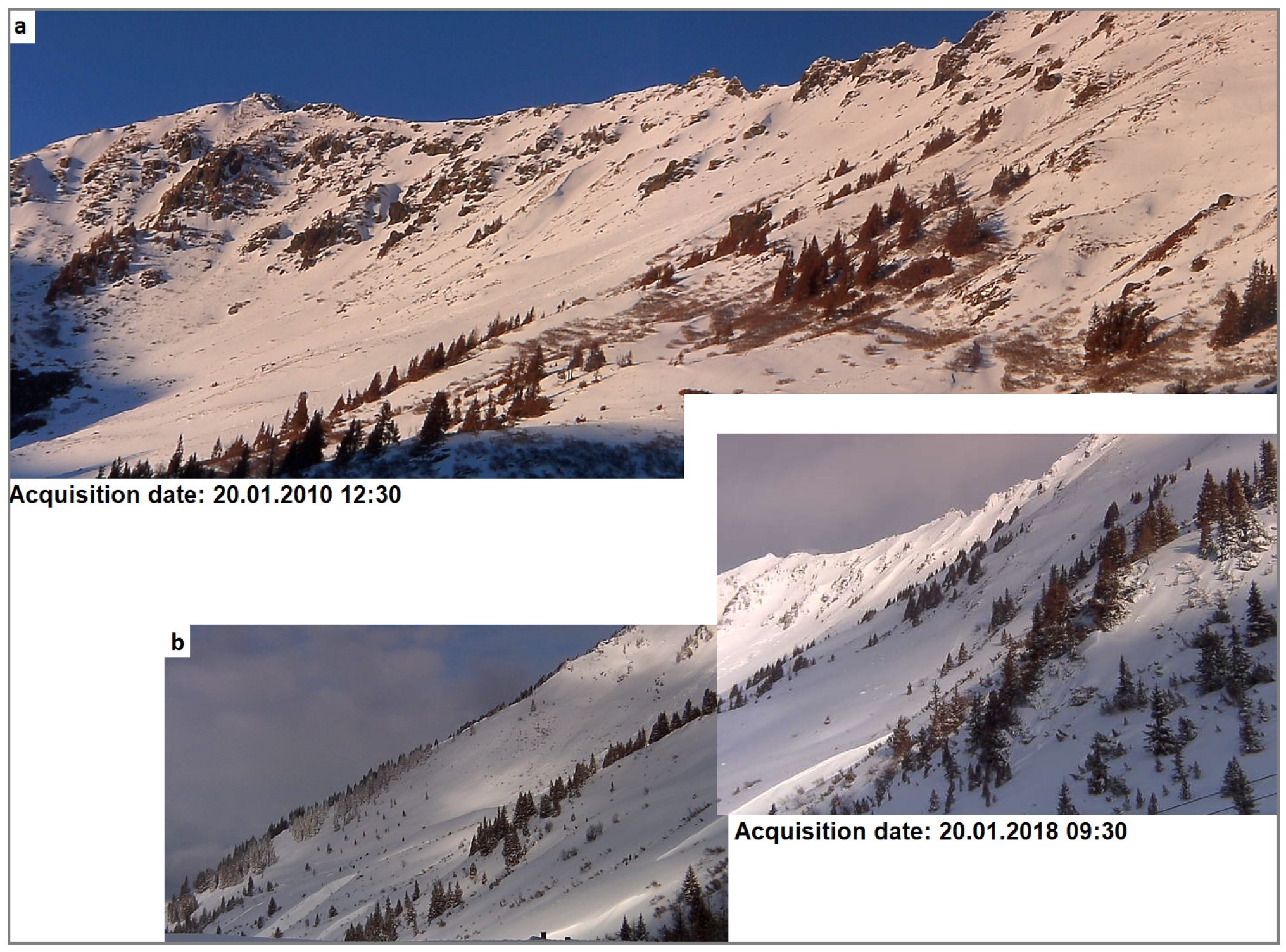

During the 2009/10 and 2010/11 winter seasons, the camera was installed at the former university sports center (Uni in Figure 3b, camera position 1 in Table 1). During the 2015/16, 2016/17, and 2017/18 winter seasons, the camera was relocated to a nearby lift station (Skilift in Figure 3b, camera position 2 in Table 1). Both camera locations provided comparable viewing angles of the monitored avalanche slopes, as can be seen in Figure 4. The observations from the two different camera locations can therefore be compared.

Table 1.

Meteorological and snow measurement stations used for observations.

Figure 4.

Image mosaic from the panoramic camera taken from (a) the first installation site (Uni) during the 2009/10 and 2010/11 winter seasons and (b) the second installation site (Skilift) during the three later seasons.

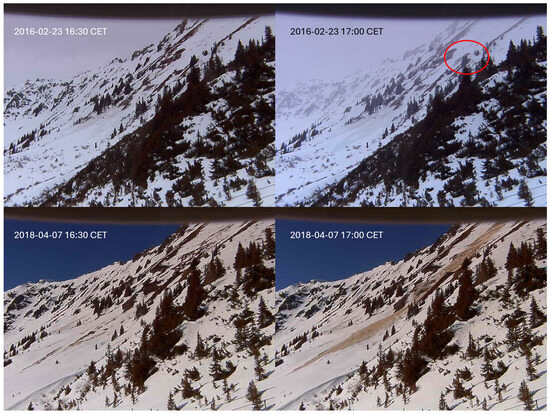

All images were screened manually, and both the occurrence and release time of glide-snow avalanches were recorded. An example of two subsequent images showing the occurrence of a glide-snow avalanche is shown in Figure 5. Two additional examples showing glide-snow avalanche releases are presented in Figure A1. While it can be difficult to spot a glide-snow avalanche on two images presented next to each other (e.g., Figure A1, upper two images), manually clicking through the image sequence on a screen makes changes between subsequent images considerably easier to detect.

Figure 5.

Glide-snow avalanche event recorded by the panoramic camera provided by the GeoSphere Austria on 14 March 2017, between 15:00 CET and 15:30 CET. On the left image of the hillside before and on the right image of the hillside after a glide-snow avalanche event. Usage of images with friendly permission from GeoSphere Austria, 2017.

The release time of the glide snow avalanche is defined as the time when the avalanche was first recorded. For example, in Figure 5, the assigned release time of the glide snow avalanche is 15:30 CET. As both release dates and relatively precise release times were recorded, we were able to investigate the seasonal and diurnal distributions of glide-snow avalanche releases at Planneralm.

2.3. Meteorological Data

In the close surroundings of the observed slopes, meteorological and snow data from several automated stations were used for the analysis (Figure 3). The stations are operated by the Province of Styria and GeoSphere Austria respectively, and the observed variables vary between stations. For the first two winter seasons we used data from station 100, which is further away from the slopes, and automated snow height measurements next to the university sports centre. Beginning in winter season 2015/16 we used temperature data from the newly erected station 110, directly above the monitored slopes, and automated snow height measurements from station 101.

For temperature homogenization in the decision tree and random forest model, we apply an adiabatic extrapolation to adjust measurements from the lower station 100 (Figure 2) to the elevation of the higher station 110. Station 100, located on the summit ridge 2 km from the observed area at an elevation of 2019 m, was used during the first two winter seasons. Station 110, situated on the summit ridge directly above the observed slopes at an elevation of 2089 m, was used during the last three winter seasons. Accordingly, temperature measurements from station 100 are corrected to account for the 70 m elevation difference between the two stations. Assuming a temperature lapse rate of −0.65 °C per 100 m elevation increase, we subtract 0.46 °C from the temperature values recorded at station 100 before using them as input for the decision tree and random forest model.

In order to determine whether the temperature series still contains an abrupt shift, we applied the non-parametric Pettitt test to the adiabatically corrected TA_mean series. The Pettitt test results revealed no evidence of a structural break in the time series, with the break indicator showing a non-significant coefficient (p_value = 0.568).

An overview of which data was used when, including the metadata from the stations, is given in Table 1. An even more detailed description of the study area, the weather stations, and the data can be found in [22].

We analyzed the data first visually and then also computed the Pearson correlation matrix of the various variables to examine pairwise linear relationships. The resulting matrix allowed us to identify potential multicollinearity and understand the structure of the input features. Moreover, we calculated the point-biserial correlations between glide-snow avalanche occurrence and meteorological variables.

2.4. Random Forest Model and Classification Tree

In order to learn from the observed data, we wanted to build a model tailored specifically to our study site in order to, in a first step, identify and later predict glide-snow avalanches. In short, we wanted a model that uses various meteorological and temporal data as input (predictor variables) and yields the output (target variable) “avalanche hour” (AH) or “non-avalanche hour” (NAH). “Avalanche hour” means that an avalanche happens within this hour, and “non-avalanche hour” means that no avalanche happens within this hour. As we wanted a transparent model that is easy to interpret and that also teaches something about the process, we decided on a classification tree model.

Classification trees [23] are a type of supervised machine learning model that recursively splits the data based on feature values to predict a categorical outcome. At each decision node, the algorithm selects the feature and threshold that best separate the observations according to a chosen criterion, such as Shannon entropy. This results in a tree-like structure of decision rules that is easy to visualize and interpret, allowing us to understand which factors contribute most to the occurrence of glide-snow avalanches. The model can be readily implemented in Python (Python version 3.8.10) [24] using widely available libraries, facilitating reproducibility and transparency in both model development and application.

To assess the relative importance of the input variables in predicting glide-snow avalanches, we additionally employed a random forest model [25]. This ensemble method builds multiple classification trees on bootstrapped subsets of the data and aggregates their predictions, thereby generally improving robustness and reducing overfitting compared to a single tree. By examining both the inherent feature importance derived from the model and permutation-based importance measures, we were able to identify which predictors contributed most to the model’s decisions, providing further insight into the factors controlling avalanche occurrence.

As model input variables (predictors), we extracted various variables which have proven to be of importance in avalanche forecasting, e.g., [8,19,26] from our temperature and snow-height data. These variables were: mean hourly/daily air temperature, maximum hourly/daily air temperature, minimum hourly/daily air temperature, difference of maximum to minimum daily temperature, mean temperatures for different preceding times (3 h, 5 h, 7 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, 120 h), snow height, 24 h-difference in snow height, 48 h-difference in snow height, five-day new-snow sum, 24 h-decrease in snow height, 48 h-decrease in snow height, hour of the day, and day of the winter season (starting to count on 1 October, the beginning of the hydrological year).

As most of the possible input variables are strongly correlated and some are even correlated by definition, e.g. the mean and the maximum air temperature, we had to carefully and iteratively find the most meaningful variables for our models. For the temperature variables, we decided to use the means, as they are most stable and are less prone to outliers than the maximum or minimum temperatures. For similar variables but at different time scales, such as 24 h-difference in snow height and 48 h-difference in snow height, or the temperatures with different preceding times, we systematically ran both models several times with each variable and noted model performance as well as impurity (gini) importance and permutation importance for the random forest model. Based on these evaluations, we selected the variables that demonstrated the best and most stable results across both models.

As the target variable, we used “avalanche hours, meaning “this is an hour where a glide-snow avalanche occurs”. As warm glide-snow avalanches are driven by meteorological variables, whereas cold glide-snow avalanches are driven by pre-existing ground conditions [10], these two kinds of glide-snow avalanches need to be modeled separately [8] or at least with measurements of the liquid water content of the snow/soil interface as input data [11]. As we only observed two cold glide-snow avalanche events and have no measurements of liquid water at the snow/soil interface available, we restrict our modeling to warm glide-snow avalanche events. So, strictly speaking, our “avalanche hour” event is an hour where a warm-glide snow avalanche event occurs, and a “non-avalanche hour” is an hour where no warm-glide snow avalanche occurs.

In the avalanche input data for the classification tree, as well as for the random forest model, we assigned the label “avalanche hour” (AH) for three consecutive hours surrounding a recorded avalanche event. Firstly, we took the hour where the avalanche was first recorded, which means that it actually happened within the last 30 min. Secondly, we accounted for the possibility that the avalanche occurred before the time the image was taken by taking the hour before the recorded avalanche event. Thirdly and finally, we took the hour after the recorded avalanche event as AH, taking into account that maybe conditions were also good for warm glide-snow avalanche release the hour after the avalanche actually released; however, the avalanche was already down. Note that we also experimented with 1 h, 6 h, 8 h, 12 h, and 24 h (daily) time-frames; however, the three-hour time-frame gave the most robust results with the best classification performance. Moreover, a three-hour period seems a realistic time frame for conditions promoting the release of warm glide-snow avalanches.

3. Results

3.1. Avalanche Observation and Meteorological Results

In the five winter seasons, a total number of 92 glide-snow avalanches were observed. We observed 90 warm-temperature glide-snow avalanche events and two cold-temperature glide-snow avalanche events. The two cold glide-snow avalanche events both released during the night (the nights leading to 15 March 2016 and 9 February 2018, respectively).

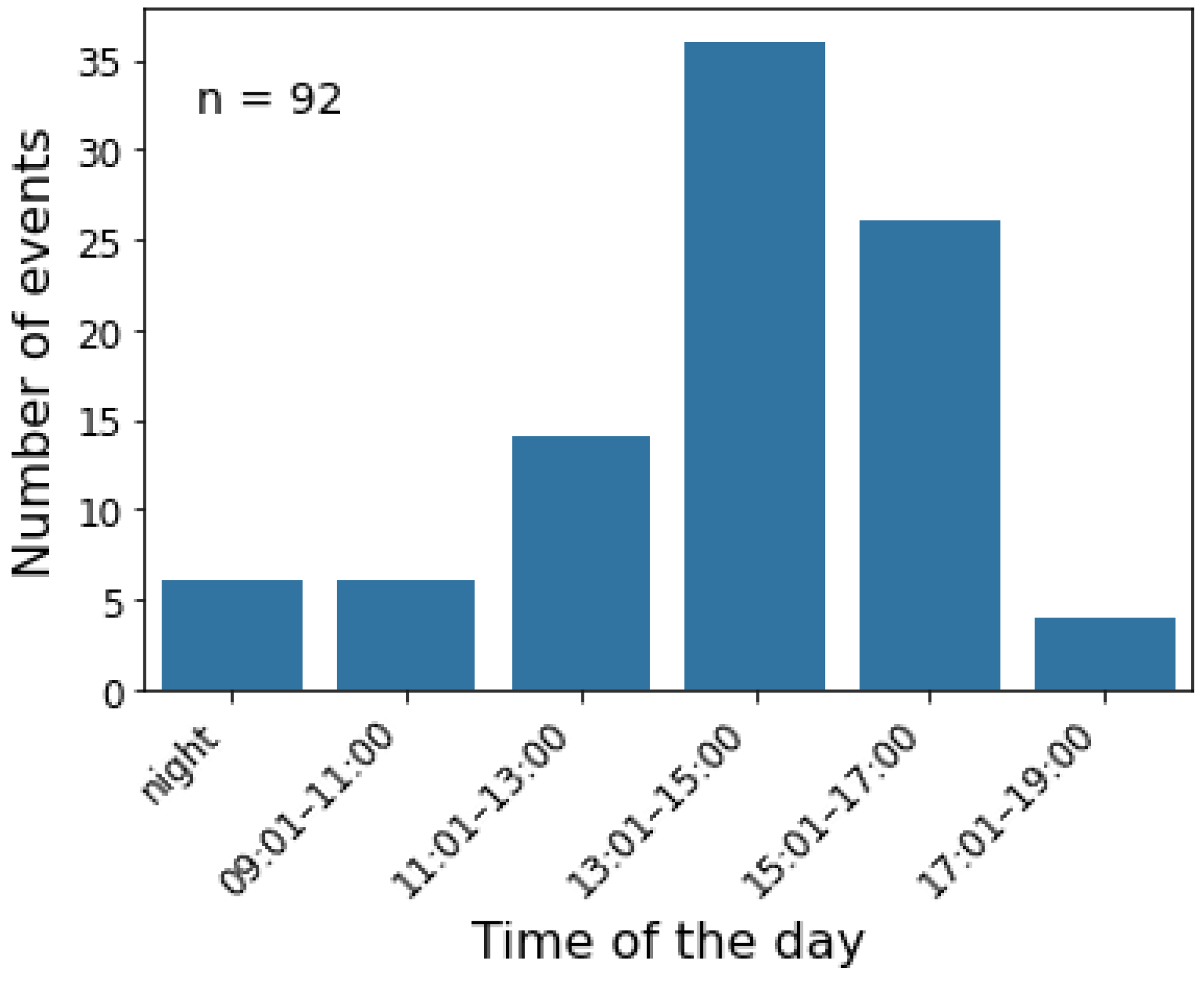

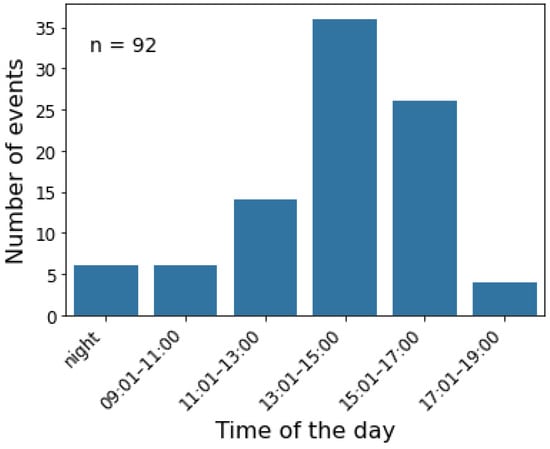

A key observation from our monitoring campaign was the timing of each event. Figure 6 presents the daytime distribution of the 92 glide-snow avalanche events recorded over five winter seasons. Events occurring after nightfall are classified as “night”. The majority (67%) of all observed glide-snow avalanche events were released in the afternoon between 13:00 and 17:00, and an even greater majority (83%) of all glide-snow avalanche events released between 11:00 and 17:00.

Figure 6.

Diurnal distribution of glide-snow avalanche releases.

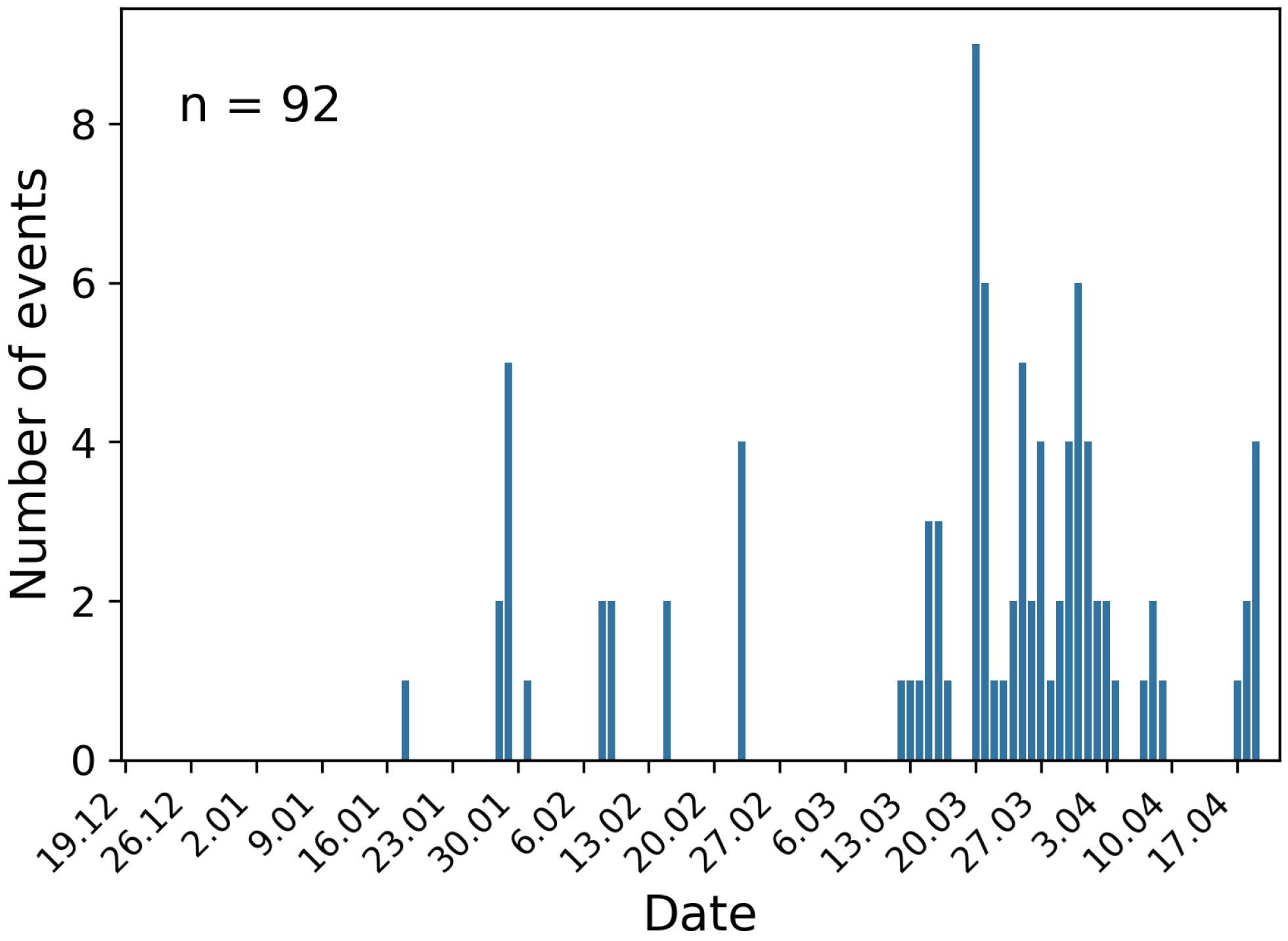

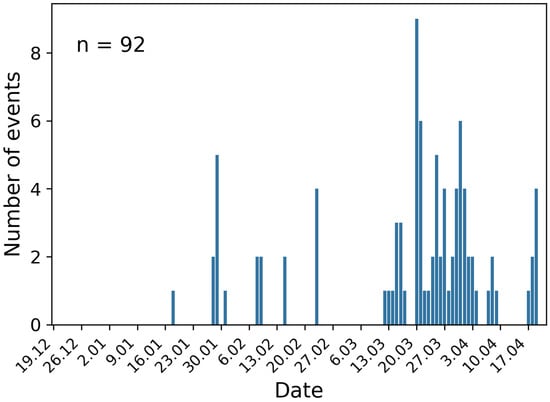

The seasonal distribution, i.e., the number of glide-snow avalanche events on a given date over all five winter seasons, is shown in Figure 7. We find that a majority (72%) of the observed glide snow avalanches released between the 12th of March and the middle of April.

Figure 7.

Seasonal distribution of glide-snow avalanche releases.

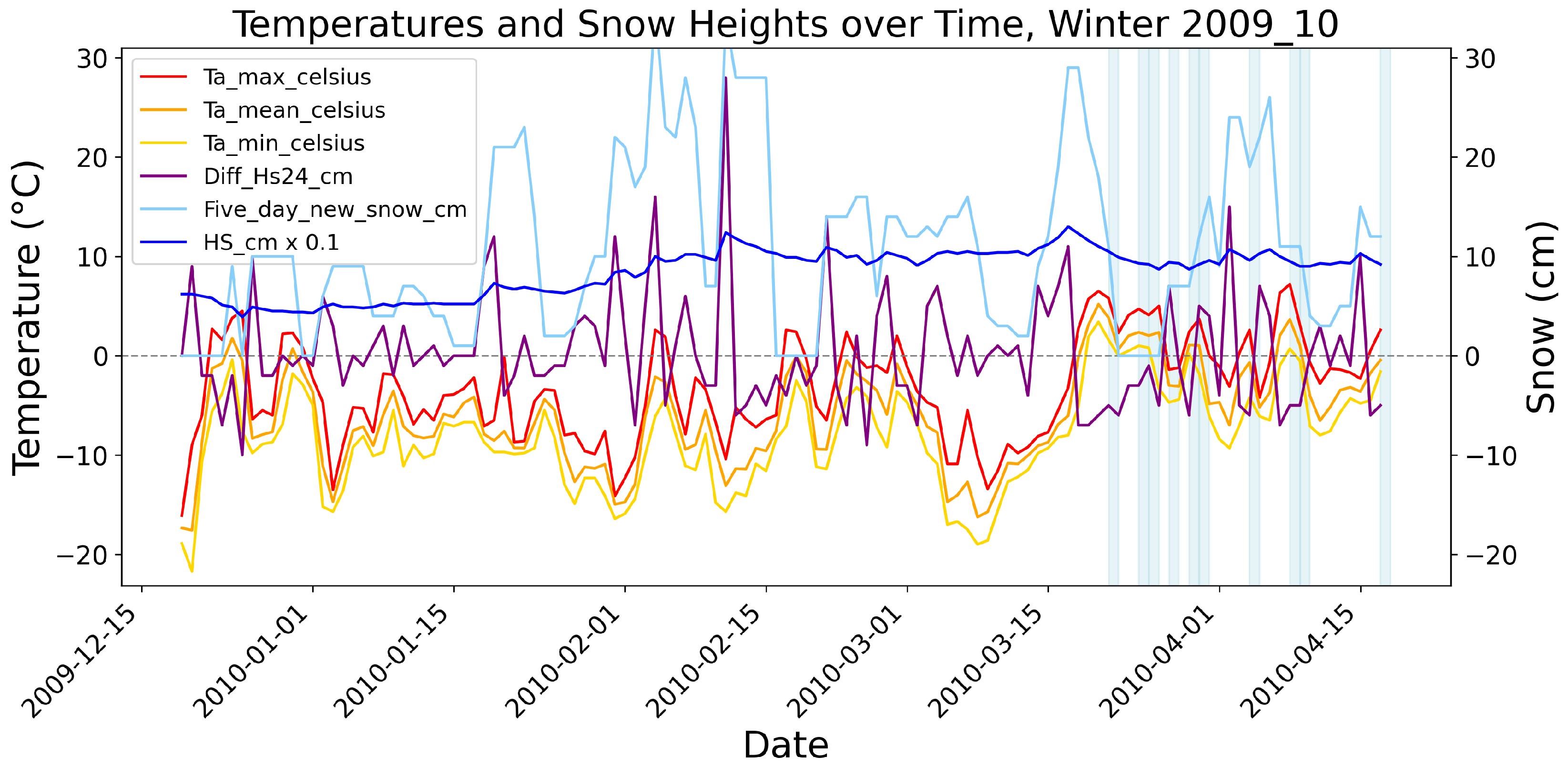

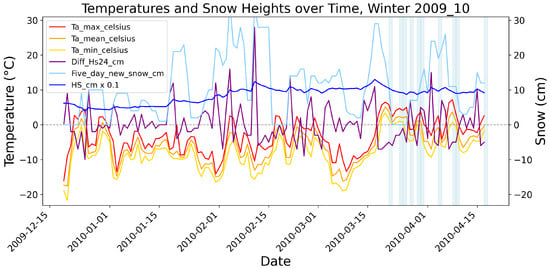

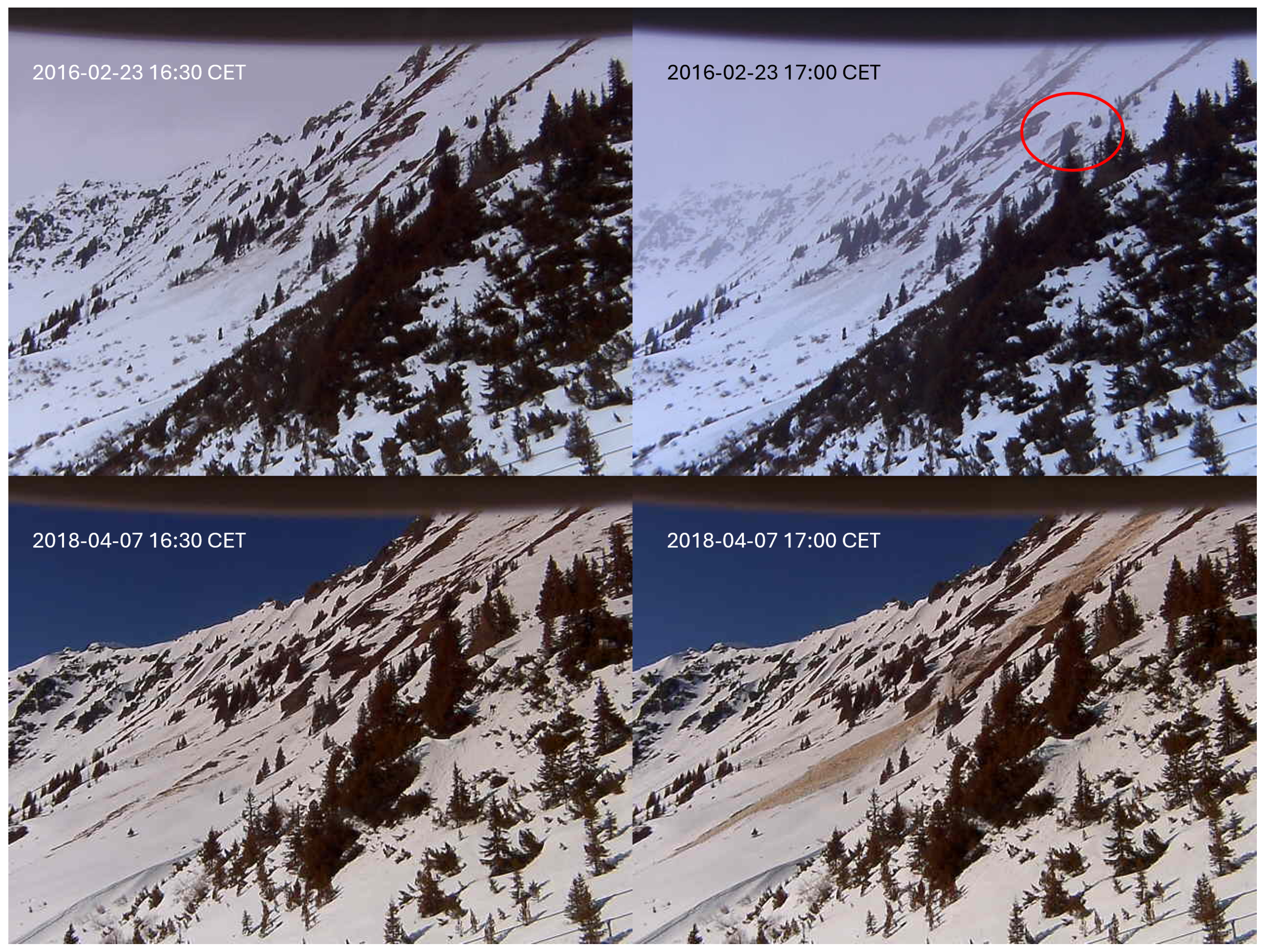

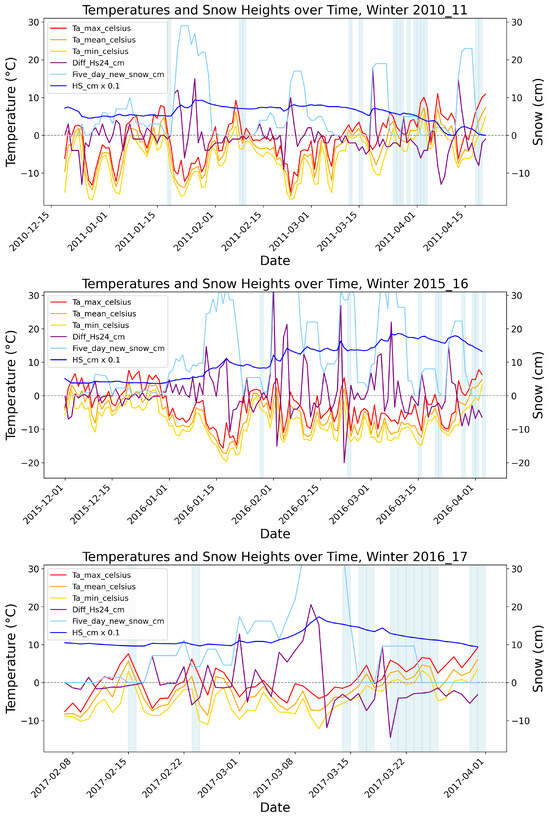

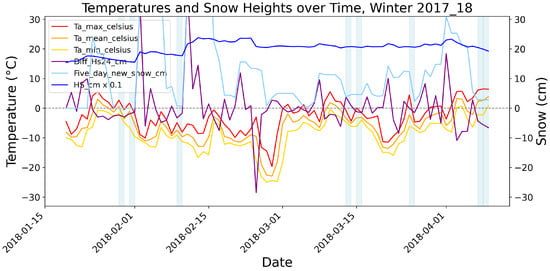

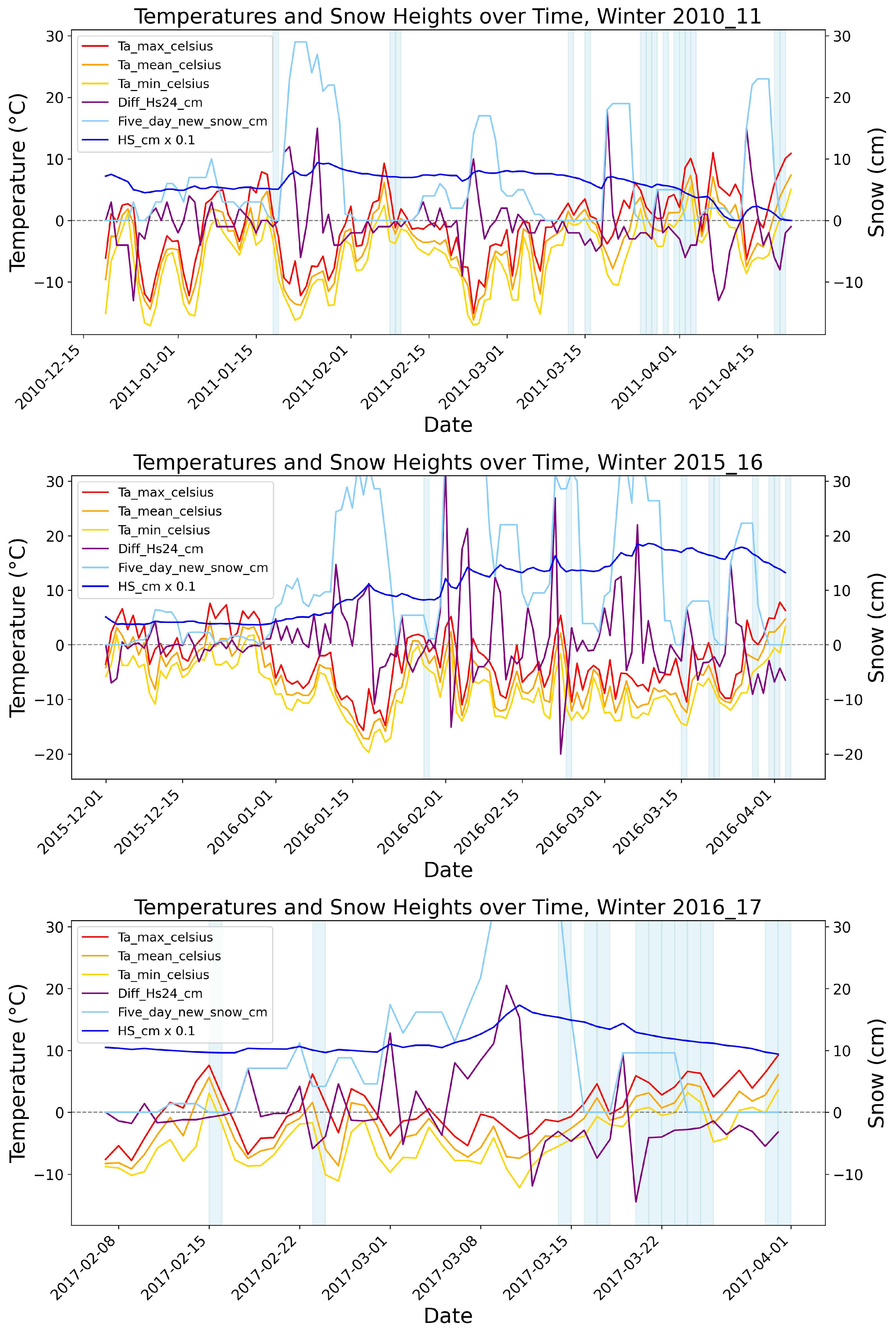

The temporal progression of the winter season 2009/10 with glide-snow avalanche days as well as the meteorological variables maximum daily air temperature, mean daily air temperature, minimum daily air temperature, 24 h difference in snow height, five-day new snow sum, and snow height (×0.1 for better visibility) is shown in Figure 8. The respective graphs from the winter seasons of 2010/11, 2015/16, 2016/17, and 2017/18 are depicted in the Appendix A (Figure A2).

Figure 8.

Observed glide-snow avalanche events and recorded meteorological data for the winter 2009/10. Glide-snow avalanche days (light-blue vertical bars), maximum daily air temperature (°C, red), mean daily air temperature (°C, orange), minimum daily air temperature (°C, yellow), 24 h-difference in snow height (cm, purple), five-day new snow sum (light-blue), and 0.1 × snow height (cm, blue).

It can be seen that the Planneralm is quite an active area with respect to glide-snow activity, the main season for glide-snow avalanche activity roughly being mid-March to mid-April. There is a significant moderate positive correlation between glide-snow avalanche days (AD, i.e., a day where a glide-snow avalanche is released) and all daily air temperatures (point-biserial correlation AD and Ta_min_celsius: 0.36, p-value: 4 × 10−17; AD and Ta_max_celsius: 0.36, p-value: 1 × 10−16; AD and Ta_mean_celsius: 0.37, p-value: 2 × 10−17).

3.2. Modeling Results

The variables which proved most useful for our classification tree and random forest model were the day of the winter (day_of_winter), the hour of the day (hour), the mean hourly air temperature (TA_mean), the difference in snow height in the last 24 h (diff_HS24_cm), and the mean air temperature of the preceding 48 h (TA_mean_48h).

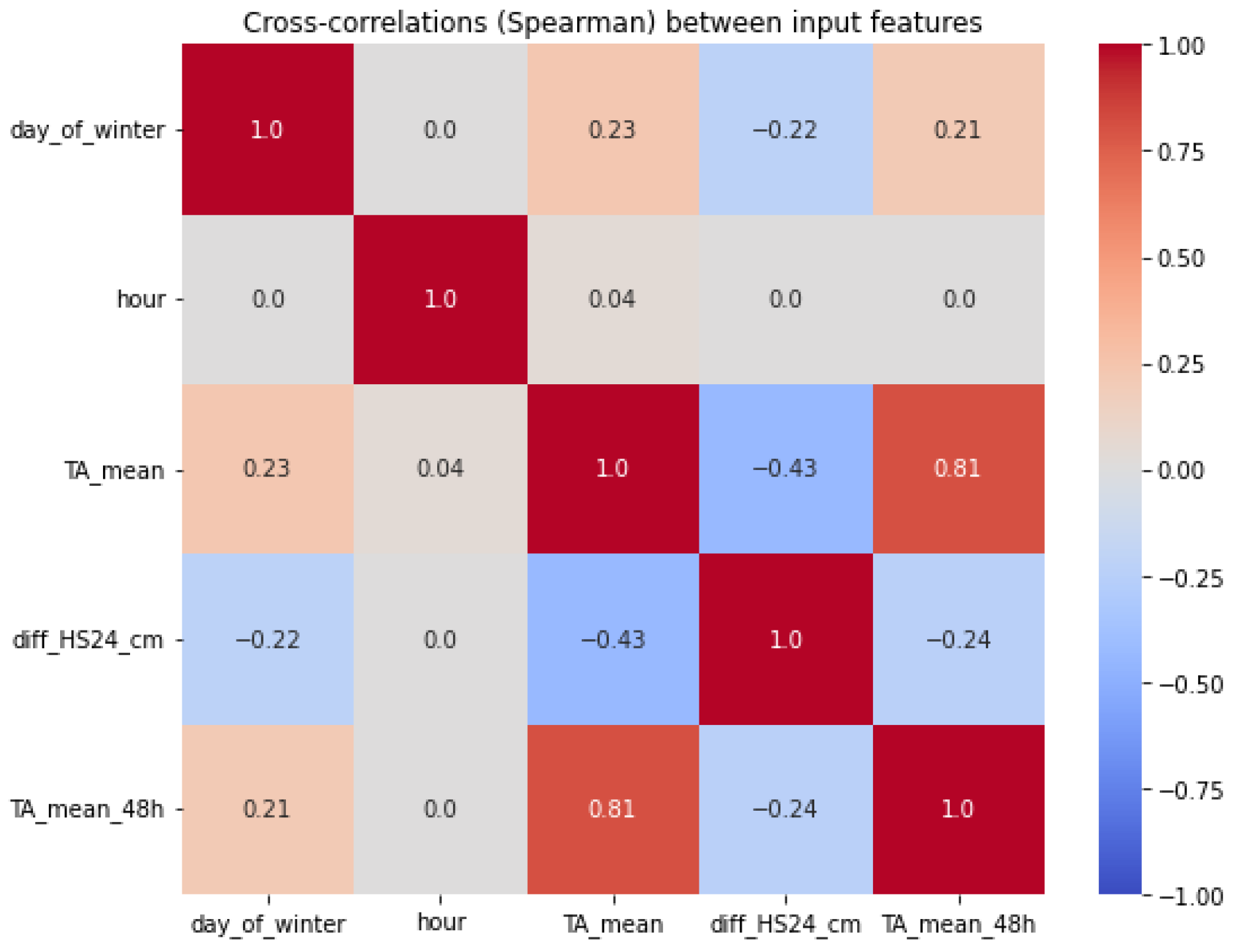

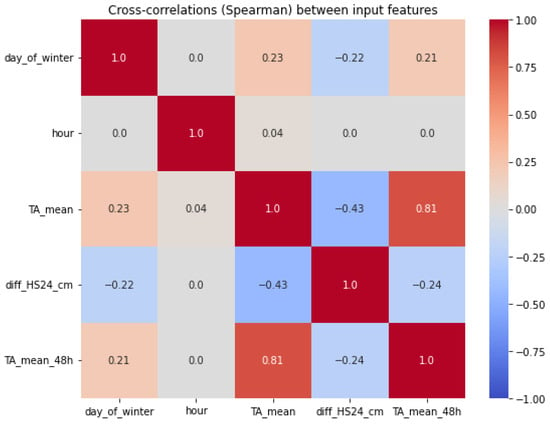

The cross-correlation matrix Figure 9 between the five meteorological and temporal input variables shows the correlations among the predictors. Mean air temperature of the preceding 48 h (TA_mean_48h) exhibits a high positive correlation with the mean hourly air temperature (TA_mean) (r = 0.81), as expected. TA_mean also shows a moderate negative correlation with the difference in snow height in the last 24 h (diff_HS24_cm) (r = −0.43). All remaining variable pairs show only weak or negligible linear correlations.

Figure 9.

Heat map showing the cross-correlations between the variables day_of_winter, hour, TA_mean, diff_HS24_cm, and TA_mean_48h.

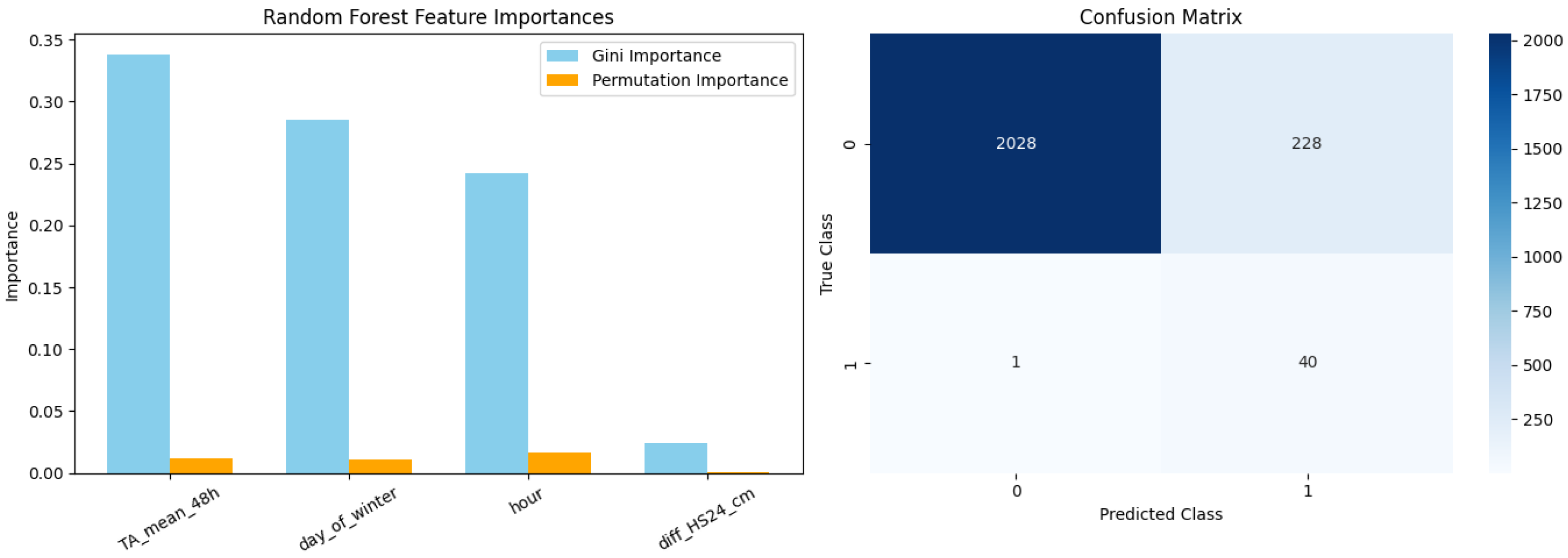

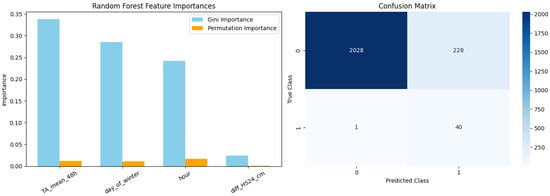

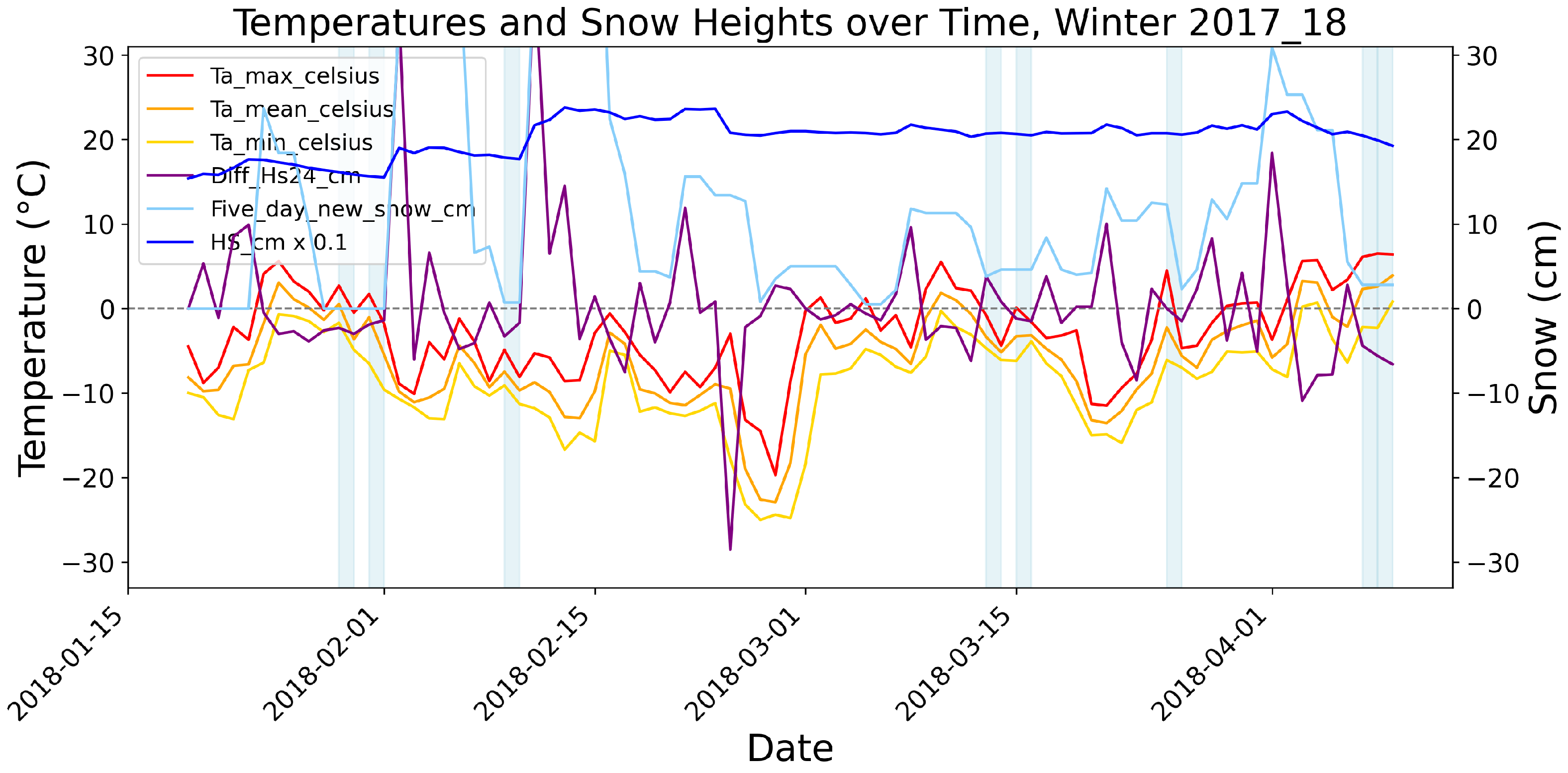

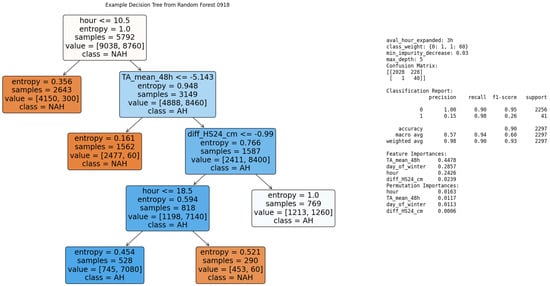

Figure 10 summarizes both the drivers of the random forest model and its predictive performance, whereas an example tree of the random forest model is shown in the Appendix A in Figure A3. On the left panel of Figure 10, we see the feature importances. From the impurity (gini) importance, we see that TA_mean_48h is the dominant predictor (≈0.34), followed by day_of_winter (≈0.29) and hour (≈0.24). diff_HS24_cm contributes little (≈0.02). Permutation importance confirms the same ranking: hour shows the largest drop in performance when permuted, while TA_mean_48h and day_of_winter also contribute positively, diff_HS24_cm has a negligible effect. These importance values remained stable across 30 model runs.

Figure 10.

Random forest model: variable importances (left) and confusion matrix (right).

On the right panel of Figure 10, we see the classification (predictive) performance. The confusion matrix shows strong overall accuracy. Out of all samples, the model correctly classified 2028 true negatives and 40 true positives, with 228 false positives and 1 false negative. This corresponds to very high recall for AH (40/41 ≈ 97.6%) and high specificity for the NAH (2028/2256 ≈ 89.9%), indicating the model rarely misses positive events while keeping false alarms relatively low. Also, the confusion matrix stayed stable over 30 model runs.

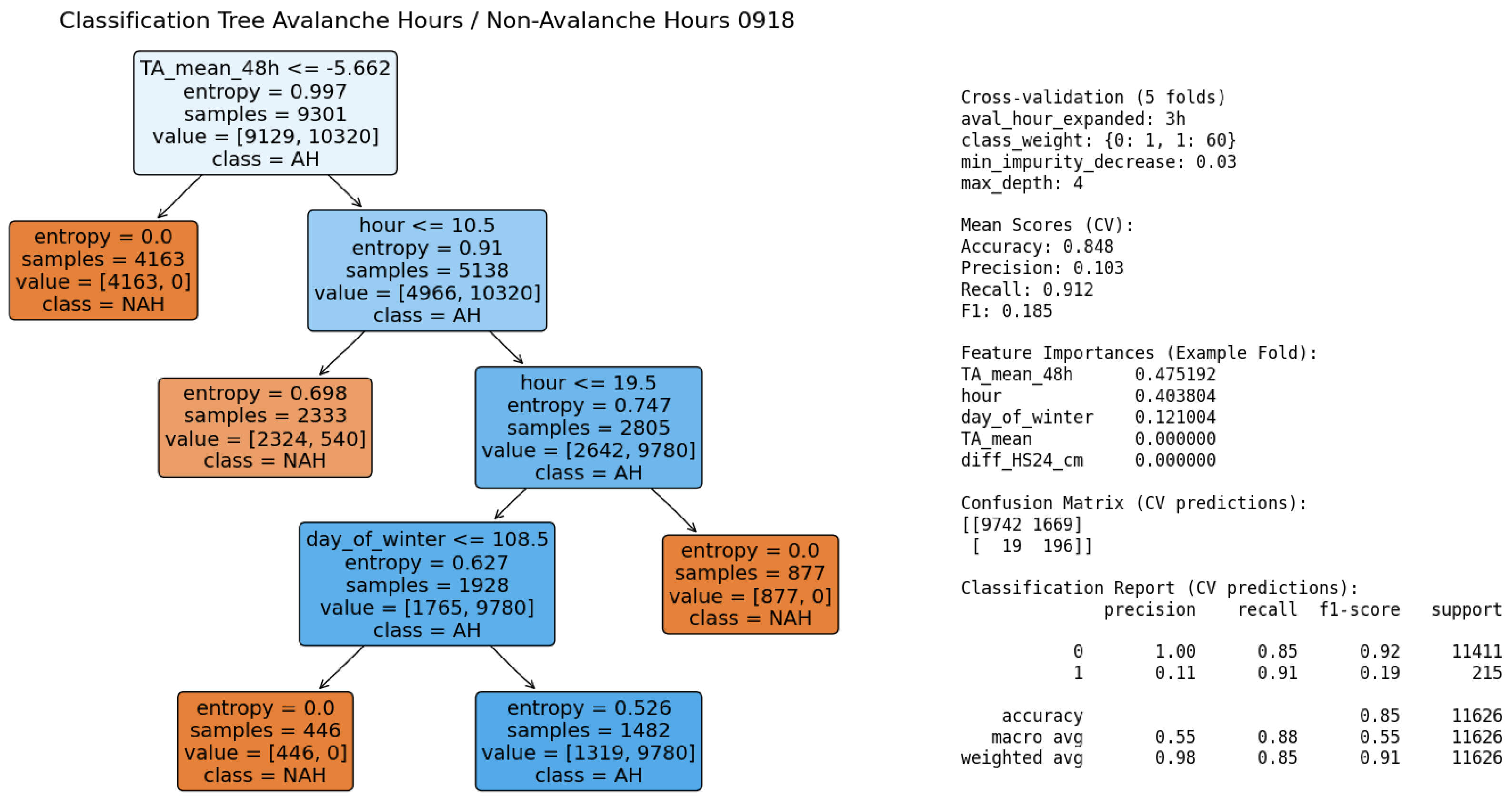

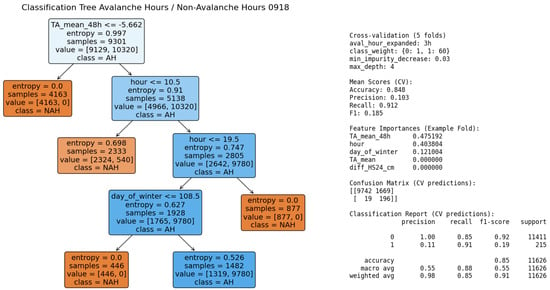

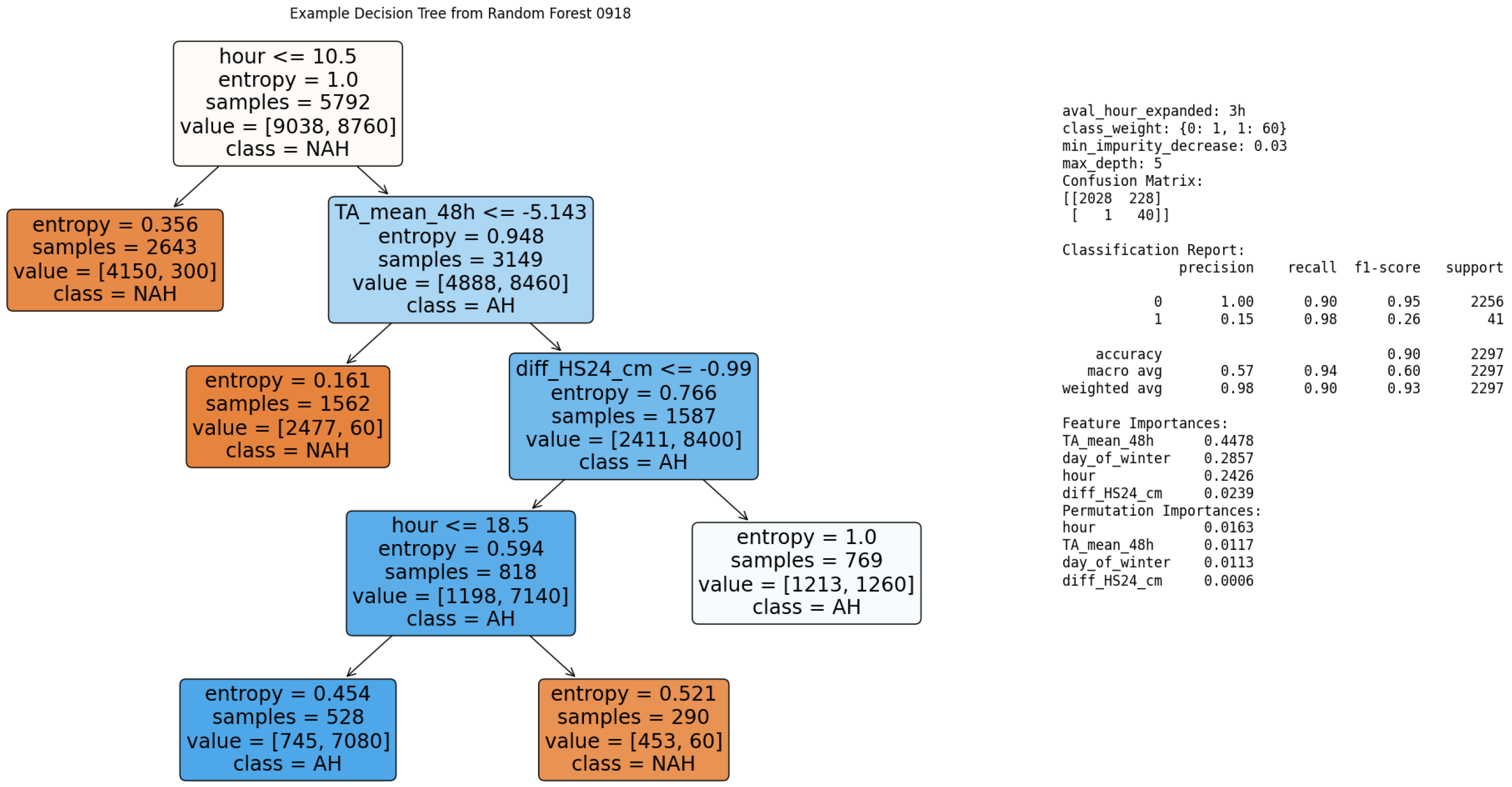

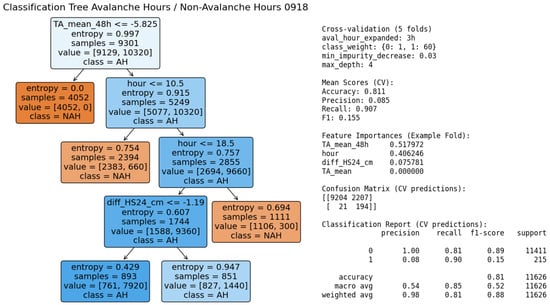

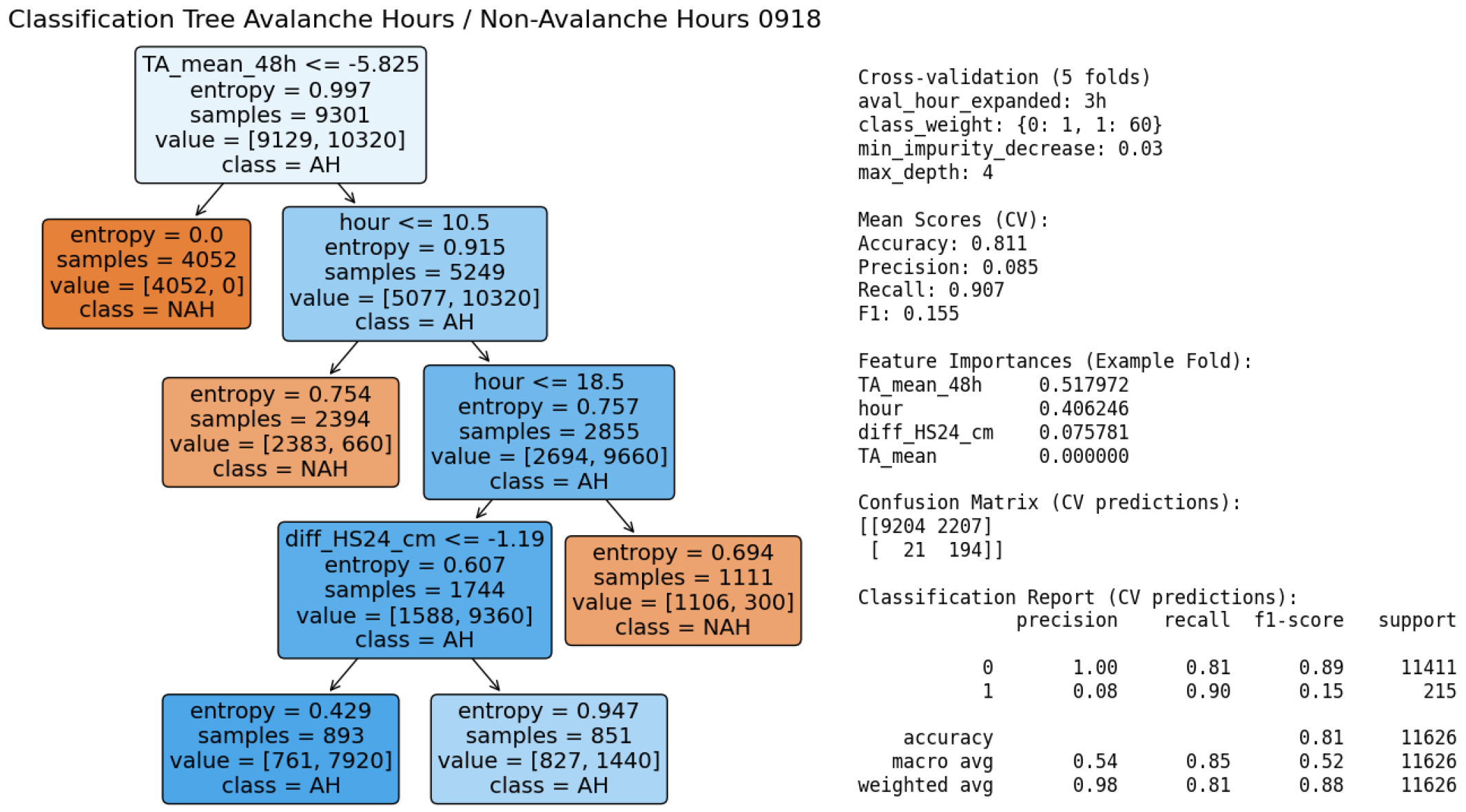

Figure 11 shows our classification tree trained to separate avalanche hours (AH) from non-avalanche hours (NAH) using five-fold cross-validation and class weighting (1:60). A similar classification tree, but without day of winter as an input variable, is additionally shown in the Appendix A, Figure A4.

Figure 11.

Classification tree discriminating between avalanche hours (AH) and non-avalanche hours (NAH).

Considering tree structure and drivers, the first split is on mean air temperature of the preceding 48 h (TA_mean_48h) at −5.66 °C, identifying cold conditions as the dominant control. For warmer conditions, hour of day (hour) provides the next strongest separation (splits at 10.5 h and 19.5 h), and day_of_winter with a split at day 108.5 corresponding to 16th January, which is four days after the coldest day of the average winter season (Figure A5). Feature importance from a representative fold quantifies this ranking: TA_mean_48h (0.48), hour (0.40), day_of_winter (0.12), while TA_mean and diff_HS24_cm contribute negligibly.

Considering predictive performance, the confusion matrix, where the rows represent the true classes NAH and AH (ground truth), and the columns represent the predicted classes by the model (NAH and AH predicted), is shown in Figure 11, right side in the middle. The confusion matrix shows 9742 true negatives (non-avalanche hours correctly classified as non-avalanche hours), 1669 false alarms (non-avalanche hours classified as avalanche hours), 19 false negatives (avalanche hours classified as non-avalanche hours), and 196 true positives (avalanche hours correctly classified as avalanche hours).

4. Discussion

Our results show that the release times of warm glide-snow avalanches as Planneralm (Figure 6) are strongly linked to the warmest hours of the day (Figure A6). The majority of events occurred during the early afternoon, closely following peak energy input, indicating a short response time of glide-snow avalanches to meteorological forcing. Seasonally, most avalanches occurred between mid-March and mid-April, when snowmelt is possible while a continuous snow cover persists.

Statistical analysis confirmed a significant relationship between avalanche occurrence and air temperature. Avalanche days were moderately but significantly correlated with daily minimum, mean, and maximum air temperatures, consistent with previous studies. However, high temperatures also frequently occurred on non-avalanche days, demonstrating that current air temperature alone is insufficient for reliable operational forecasting. By incorporating a time-lag variable and temporal information into our classification tree and random forest models, predictive performance improved substantially.

4.1. Discussion of the Modeling Results

Our decision tree (Figure 11, left side) identifies three main predictors for glide-snow avalanche days at Planneralm: TA_mean_48h, hour of the day, as well as day of the winter. In our dataset, glide-snow avalanche days mainly occurred when TA_mean_48h ≲−5.7 °C the hour of the day was between 11:00 and 19:00 CET, and the winter day was after 16 January. The feature importance analysis (Figure 11, right side) showed that TA_mean_48h was the dominant predictor (48%), followed by hour of the day (40%), and day of winter (12%). The variables TA_mean_48h and day of the winter live on a longer time-scale than the variable hour of the day. The combination of these time scales suggests that there needs to be a longer-term predisposition for warm-glide snow avalanche release, marked by the importance of TA_mean_48h and even more so on the day of winter. Additionally, there apparently needs to be a relatively short-term trigger for warm glide-snow avalanche release, reflected by the importance of hour and also the marked diurnal distribution of glide-snow avalanche events (Figure 6).

Note that the thresholds of this decision tree are entirely site-specific and data-driven. The thresholds are not intended to serve as fixed values with global applicability. Instead, these thresholds are specifically valid for the region in question, based on the available weather data collected at the corresponding weather station. The data is measured at the weather station, which is not located directly within the avalanche slope, as this is usually not the case. For reproducibility and transferability to other locations with different avalanche slopes and distinct weather station placements, our model would need to be retrained using data from those specific sites. Additionally, thresholds for temporal variables may vary across locations due to differences in diurnal or seasonal temperature patterns. Moreover, in case of a very strong seasonal shift due to either a very uncommon winter or a systematic shift due to climate change, the day_of_winter variable will decrease in meaning. In that case, we recommend using the diff_HS24_cm, variable instead, as it gives a similar tree; however, with less precision (Figure A4). The previous time of the temperature variable, i.e., the 48 h in TA_mean_48h, might depend on the average snow depth at a specific location, as it takes time for snow surface temperature and wetting to reach the bottom of the snowpack. Accordingly, we expect the time to increase for deeper snowpacks.

Comparing model evaluation of the classification tree (Figure 11, right side) to model evaluation of the random forest (Figure 10, right side), we see a similar ranking of predictor variables and roughly similar classification (predictive) performance, the random forest model performing slightly better. Those similarities in predictor ranking and classification importance stayed stable over 30 model test runs for each model; this stability increases the trustworthiness of model results.

Because avalanche hours are rare and the primary goal is not to miss events, the very high recall of both models is more important than their low precision. Consequently, our decision tree is tuned to rarely miss avalanche hours at the cost of many false alarms, consistent with the strong class imbalance (215 AH vs. 11’411 NAH). In this context, the single classification tree, despite its many false alarms, is practically useful: it captures about 90% of avalanche hours while remaining fully transparent, so each warning can be traced back to a small set of physical thresholds (mainly recent temperature, time of day, and season). The random forest improves precision and recall, but its ensemble structure makes it less suitable for operational or scientific interpretation of individual decisions.

Instead, the random forest is best viewed as a tool for discovering and assessing predictors’ stability. Its feature and permutation importances show that TA_mean_48h, hour, and day_of_winter are consistently dominant, with diff_HS24_cm providing secondary information. These stable rankings justify the variable choices in the single tree and reduce the risk that its structure is an artifact of one particular data split. In this way, the random forest provides a robust, data-driven basis for selecting predictors, while the classification tree provides an interpretable and operationally usable avalanche-detection rule set.

4.2. Usage of the Model as an Avalanche Warning Tool

Once our model is calibrated to a specific location, we expect it to be useful for warm-glide snow avalanche warning and prediction. Note that the success of calibrating the model to another location will depend on the available data and, presumably, on site-specific characteristics. The forecasters/avalanche commission members can take the predicted/measured mean temperature of the 48 h preceding the time of interest, as well as the hour of the day and the day of the winter, put this into the model, either via computer or manually using the classification tree. They then get a prediction “avalanche hour” or “non-avalanche hour” together with a certainty estimate of the prediction (Shannon Entropy), see e.g., Figure 11. In case the model predicts “avalanche hour”, forecasters or commission members are recommended to pay increased attention and, if applicable, issue a warning or a risk mitigation measure. Note that models not only assist experts in making their decisions but also in documenting their decisions. Documentation of compliance with diligence obligations is important for risk management, and a model such as ours can strengthen documentation.

4.3. Comparison to Other Studies on Glide-Snow Avalanches

Comparing our results to the results of Dreier et al. (2016) [8], who studied glide-snow avalanche release on the Dorfberg above Davos, we found quite similar conditions for warm glide-snow avalanche occurrence. There was one striking difference, however. While Dreier et al. (2016) [8] found almost twice as many cold glide-snow avalanches as warm glide-snow avalanche events (32 cold events compared to 17 warm glide-snow avalanche events), almost all of our glide-snow avalanche events were warm events (two cold events and 90 warm events). Fees et al. (2024) [7], in contrast, who also studied glide-snow avalanches on Dorfberg, detected 947 glide-snow events (650 surface [warm] events/297 interface [cold] events). Maggioni et al. (2019) [14], who studied glide-snow avalanche release with a focus on soil properties in Aosta Valley in the northwestern Italian Alps, also found more warm glide-snow avalanche events, with, however, a relatively low number of glide-snow avalanches in total (two cold versus seven warm glide-snow avalanche events). These differences suggest that the occurrence of cold glide-snow avalanches is highly site-specific and may depend strongly on local factors such as conditions for meltwater flow and groundwater availability.

Another notable difference compared to the glide-snow avalanche data presented in Fees et al. (2024) [7] is the diurnal distribution of glide-snow avalanche occurrence. While both datasets show a clear peak of glide-snow avalanche activity in the early afternoon, the data distribution even for warm glide-snow avalanches in Fees et al. (2024) [7] appears broader, with a less pronounced peak in the early afternoon. Moreover, Fees et al. (2024) [7] found that 18% of even their surface [warm] glide-snow avalanche events occurred during the night, and 14% of their interface [cold] glide-snow avalanche events occurred during the night. In contrast, night-time occurrence of glide-snow avalanches only happened for 4% of our warm glide-snow avalanche events (four out of 90) and 100% of our cold glide-snow avalanche events (two out of two).

Compared to previous studies on glide-snow avalanches, we found many similarities and a few slight differences, as discussed above. Note that most previous studies on glide-snow avalanche occurrence were carried out on the Dorfberg above Davos, e.g., [7,8,10,11]. The Dorfberg area is presumably the best-equipped and best-studied glide-snow avalanche release area in the world, with thoroughly measured and carefully analyzed data. Our study is, to our knowledge, the first longer-term study of glide-snow avalanche release performed at a different site, enabling this discussion about similarities and differences.

5. Conclusions and Outlook

5.1. Main Findings and Core Contributions

We observed glide-snow avalanche activity in our study area, Planneralm, Styria, in Austria, for five winter seasons. Within those five winter seasons, we detected 92 glide-snow avalanche events. We found that in our study region, the vast majority (98%) of all glide-snow avalanches were warm glide-snow avalanches, and most (83%) of the glide-snow avalanches released during the warm hours of the day, namely between 11:00 and 17:00. Also, most glide-snow avalanches released in spring, namely between the middle of March and the middle of April.

Moreover, we used the obtained data to train a decision tree and a random forest model for discriminating between avalanche hours and non-avalanche hours. For the avalanche hours, we found that 3 h time slots yielded the most meaningful and robust results. Moreover, we found that the most meaningful predictors for warm glide-snow avalanche hours in our study area were the mean temperature of the preceding 48 h, the hour of the day, and the day of the season. The classification tree model trained with those input variables showed a high recall, catching 90% of all warm glide-snow avalanche hours with a moderate rate (15%) of false alarms.

The significance of our findings is that we could show that the combination of longer-term variables, indicating a certain predisposition for warm glide-snow avalanche release, together with a short-term variable, indicating the need for a short-term trigger, gives the best and most robust modeling results. In our case, the longer-term variables were the mean temperature of the preceding 48 h and the day of the season, and the short-term variable was the hour of the day.

5.2. Model Applicability and Limitations

Our model is intended to be applicable to local avalanche forecasting and to avalanche commissions. The transparency of the classification tree aids direct human interpretability, credibility, and the estimation of applicability to a given situation. The limitation is that the model must be trained successfully on site-specific data. Training success will depend on available data and presumably on site-specific characteristics. The temperature threshold of TA_mean_48h ≲−5.7 °C is an indication that it needs to be cold enough for a long enough period to rule out warm glide-snow avalanches. Both the exact temperature value and the time span are presumably site-specific, and we expect those variables to vary for different locations. It is important to emphasize that models like ours are designed to support the decision-making process of avalanche experts, such as forecasters or commission members; the models are not meant to replace human judgment.

5.3. Recommendations for Future Research and Practical Avalanche Forecasting and Management

We have already planned an operational test season for local glide-snow avalanche forecasting (warm glide-snow avalanches only) together with the Avalanche Warning Service Styria, Austria. The idea is that forecasters use the classification tree to support their decision to issue a warning for a glide-snow avalanche release or, in difficult situations, also to close roads. Evaluating the outcome of this operational test season will further enhance model development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.R., A.E. and A.G.; methodology, I.R., A.E. and A.G.; software, I.R. and E.K.; validation, I.R., A.E., E.K. and A.G.; formal analysis, I.R., A.E., E.K. and A.G.; investigation, I.R., A.E., E.K. and A.G.; resources, I.R. and A.G.; data curation, I.R., A.E., E.K. and A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, I.R., A.E. and A.G.; writing—review and editing, I.R., A.E., E.K. and A.G.; visualization, I.R., A.E., E.K. and A.G.; supervision, I.R. and A.G.; project administration, I.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the four anonymous reviewers for their insightful, constructive, and innovative comments. Their feedback has improved this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Glide-snow avalanche events recorded by the panoramic camera provided by the GeoSphere Austria on 23 February 2016 and 7 April 2018, on both days between 16:30 CET and 17:00 CET. The left images show the hillside before, and the right images show the hillside after the respective glide-snow avalanche event. Usage of images with friendly permission from GeoSphere Austria, 2016 and 2018.

Figure A1.

Glide-snow avalanche events recorded by the panoramic camera provided by the GeoSphere Austria on 23 February 2016 and 7 April 2018, on both days between 16:30 CET and 17:00 CET. The left images show the hillside before, and the right images show the hillside after the respective glide-snow avalanche event. Usage of images with friendly permission from GeoSphere Austria, 2016 and 2018.

Figure A2.

Observed glide-snow avalanche events and recorded meteorological data for the winters 2010/11, 2015/16, 2016/17, and 2017/18. Days with glide-snow avalanche events. Number of glide-snow events (light-blue vertical bars), maximum daily temperature (°C, red), mean daily temperature (°C, orange), minimum daily temperature (°C, yellow), 24 h-difference in snow height (cm, purple), five-day new snow sum (light-blue), and 0.1 × snow height (cm, blue).

Figure A2.

Observed glide-snow avalanche events and recorded meteorological data for the winters 2010/11, 2015/16, 2016/17, and 2017/18. Days with glide-snow avalanche events. Number of glide-snow events (light-blue vertical bars), maximum daily temperature (°C, red), mean daily temperature (°C, orange), minimum daily temperature (°C, yellow), 24 h-difference in snow height (cm, purple), five-day new snow sum (light-blue), and 0.1 × snow height (cm, blue).

Figure A3.

Example tree from the random forest model.

Figure A3.

Example tree from the random forest model.

Figure A4.

Classification tree discriminating between avalanche hours (AH) and non-avalanche hours (NAH) without day_of_winter as an input variable.

Figure A4.

Classification tree discriminating between avalanche hours (AH) and non-avalanche hours (NAH) without day_of_winter as an input variable.

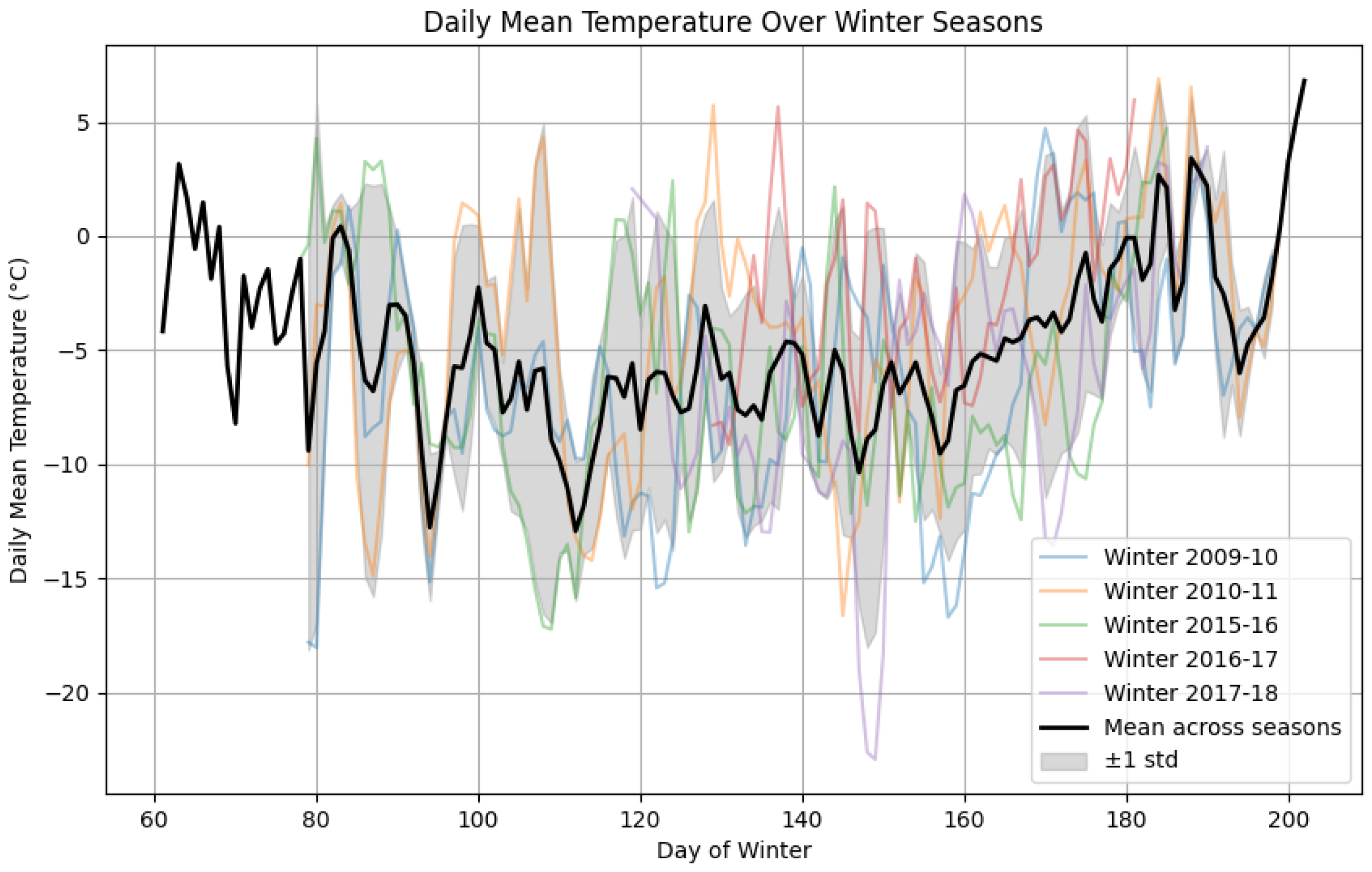

Figure A5.

Daily mean air temperature over the day of the winter season.

Figure A5.

Daily mean air temperature over the day of the winter season.

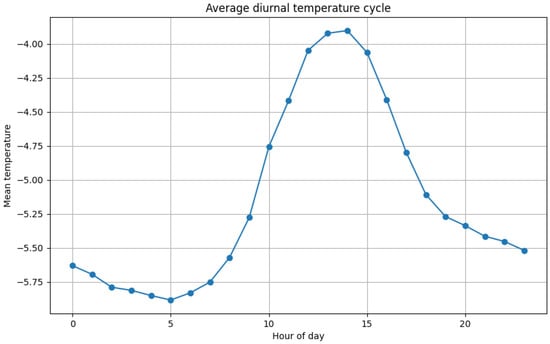

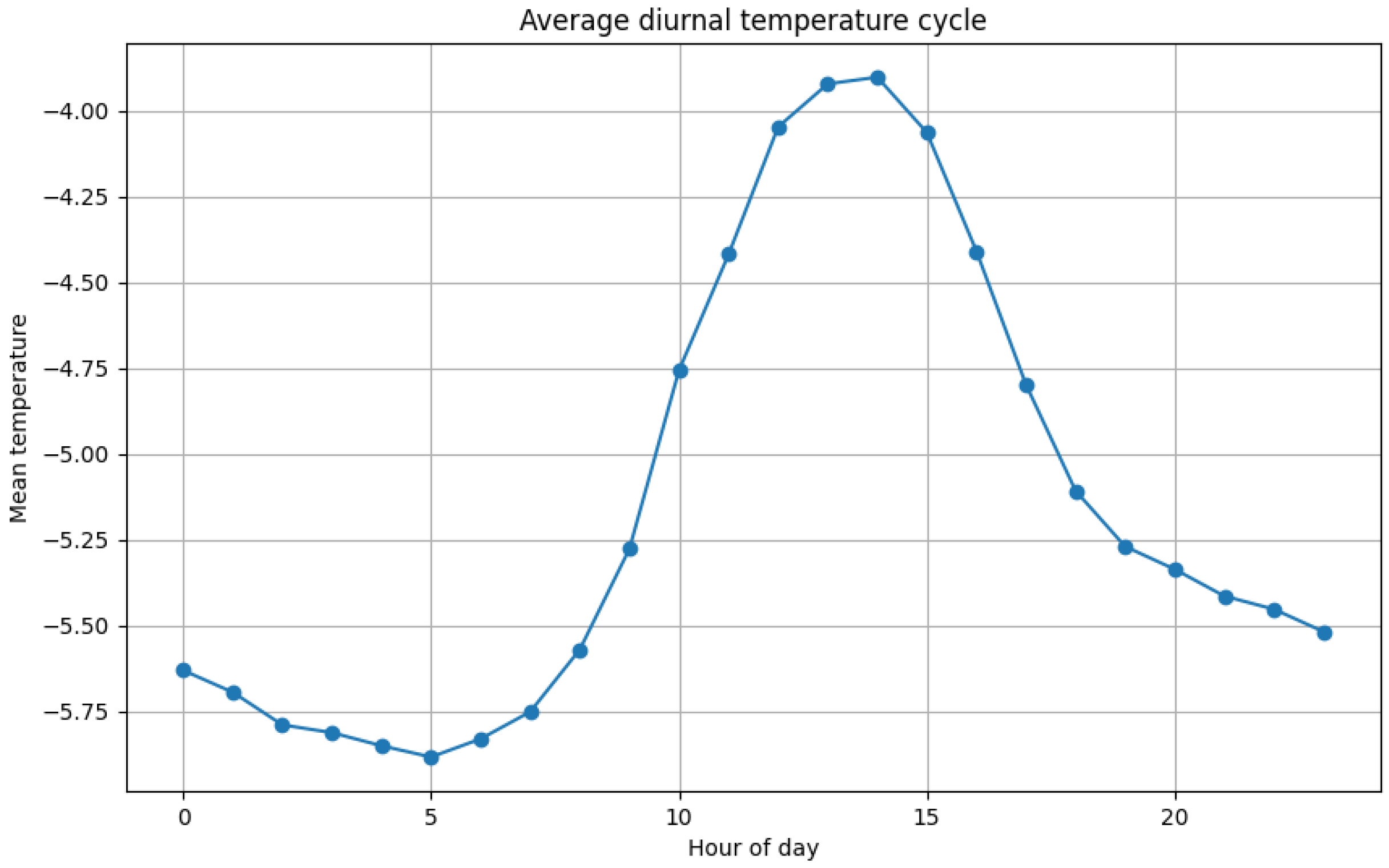

Figure A6.

Mean hourly air temperature over the hour of the day, averaged over all five seasons.

Figure A6.

Mean hourly air temperature over the hour of the day, averaged over all five seasons.

References

- Winkler, K.; Zweifel, B.; Marty, C. Schnee und Lawinen in den Schweizer Alpen. Hydrologisches Jahr 2017/18; WSL Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research SLF: Davos Dorf, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 77, p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Simenhois, R.; Birkeland, K. Meteorological and environmental observations from three glide avalanche cycles and the resulting hazard management technique. In Proceedings of the International Snow Science Workshop ISSW 2010, Lake Tahoe, CA, USA, 17–22 October 2010; pp. 846–853. [Google Scholar]

- McClung, D.; Clarke, G. The effects of free water on snow gliding. J. Geophys. Res. 1987, 92, 6301–6309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitterer, C.; Schweizer, J. Towards a better understanding of glide-snow avalanche formation. In Proceedings of the International Snow Science Workshop, Anchorage, AK, USA, 16–21 September 2012; pp. 610–616. [Google Scholar]

- Lackinger, B. Mechanics of snow slab failure from a geotechnical perspective. In Proceedings of the Symposium at Davos 1986—Avalanche Formation, Movement and Effects; Salm, B., Gubler, H., Eds.; IAHS Publication: Oxfordshire, UK, 1987; Volume 162, pp. 229–241. [Google Scholar]

- Höller, P. Snow gliding on a south-facing slope covered with larch trees. Ann. For. Sci. 2013, 71, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fees, A.; van Herwijnen, A.; Altenbach, M.; Lombardo, M.; Schweizer, J. Glide-snow avalanche characteristics at different timescales extracted from time-lapse photography. Ann. Glaciol. 2024, 65, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreier, L.; Harvey, S.; van Herwijnen, A.; Mitterer, C. Relating meteorological parameters to glide-snow ava-lanche activity. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2016, 128, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J.; McClung, D. Full-depth avalanche occurrences caused by snow gliding, Coquihalla, British Columbia, Canada. J. Glaciol. 1999, 45, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fees, A.; Lombardo, M.; van Herwijnen, A.; Lehmann, P.; Schweizer, J. The source, quantity, and spatial distribution of interfacial water during glide-snow avalanche release: Experimental evidence from field monitoring. Cryosphere 2025, 19, 1453–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fees, A.; van Herwijnen, A.; Lombardo, M.; Schweizer, J. Towards a model of glide-snow avalanche occurrence using in-situ soil and snow measurements. J. Glaciol. 2025, 71, e119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peitzsch, E.H.; Hendrikx, J.; Fagre, D.B. Terrain parameters of glide snow avalanches and a simple spatial glide snow avalanche model. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2015, 120, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resch, F.; Bair, E.; Peitzsch, E.; Miller, Z.; Fees, A.; van Herwijnen, A.; Reiweger, I. Comparison of the glide activity at two distinct regions using Swiss and U.S. datasets. In Proceedings of the International Snow Science Workshop ISSW 2023, Bend, OR, USA, 8–13 October 2023; pp. 144–149. [Google Scholar]

- Maggioni, M.; Godone, D.; Frigo, B.; Freppaz, M. Snow gliding and glide-snow avalanches: Recent outcomes from two experimental test sites in Aosta Valley (northwestern Italian Alps). Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 19, 2667–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberl, A.; Gobiet, A.; Studeregger, A.; Reiweger, I. Investigations on glide-snow avalanches. In Proceedings of the International Snow Science Workshop ISSW 2018, Innsbruck, Austria, 7–12 October 2018; pp. 920–924. [Google Scholar]

- Mitterer, C.; Schweizer, J. Glide snow avalanches revisited. Avalanche J. 2012, 102, 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- McClung, D.; Schaerer, P. The Avalanche Handbook, 2nd ed.; The Mountaineers: Seattle, WA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A. Review of Glide Processes and Glide Avalanche Release. Avalanche News 2004, 69, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mitterer, C.; Schweizer, J. Analysis of the snow-atmosphere energy balance during wet-snow instabilities and implications for avalanche prediction. Cryosphere 2013, 7, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BFW Bundesforschungszentrum für Wald. eBOD Digitale Bodenkarte Österreich. 2025. Available online: https://bodenkarte.at (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Podesser, A.; Wakonigg, H. Klimaatlas Steiermark. 2010. Available online: https://umwelt.steiermark.at (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Kindermann, E. Identifying Meteorological Release Factors of Glide Avalanches with Multivariate Statistical Analysis. Master’s Thesis, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Munich, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Loh, W.Y. Classification and regression trees. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2011, 1, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Müller, A.; Nothman, J.; Louppe, G.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. arXiv 2018, arXiv:cs.LG/1201.0490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweizer, J.; Jamieson, J.B.; Schneebeli, M. Snow avalanche formation. Rev. Geophys. 2003, 41, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.