Abstract

Accurate segmentation of 3D dental structures is essential for oral diagnosis, orthodontic planning, and digital dentistry. With the rapid advancement of 3D scanning and modeling technologies, high-resolution dental data have become increasingly common. However, existing approaches still struggle to process such high-resolution data efficiently. Current models often suffer from excessive parameter counts, slow inference, high computational overhead, and substantial GPU memory usage. These limitations compel many studies to downsample the input data to reduce training and inference costs—an operation that inevitably diminishes critical geometric details, blurs tooth boundaries, and compromises both fine-grained structural accuracy and model robustness. To address these challenges, this study proposes DiffusionNet++, an end-to-end segmentation framework capable of operating directly on raw high-resolution dental data. Building upon the standard DiffusionNet architecture, our method introduces a normal-enhanced multi-feature input strategy together with a lightweight SE channel-attention mechanism, enabling the model to effectively exploit local directional cues, curvature variations, and other higher-order geometric attributes while adaptively emphasizing discriminative feature channels. Experimental results demonstrate that the coordinates + normal feature configuration consistently delivers the best performance. DiffusionNet++ achieves substantial improvements in overall accuracy (OA), mean Intersection over Union (mIoU), and individual class IoU across all data types, while maintaining strong robustness and generalization on challenging cases, such as missing teeth and partially scanned data. Qualitative visualizations further corroborate these findings, showing superior boundary consistency, finer structural preservation, and enhanced recovery of incomplete regions. Overall, DiffusionNet++ offers an efficient, stable, and highly accurate solution for high-resolution 3D tooth segmentation, providing a powerful foundation for automated digital dentistry research and real-world clinical applications.

1. Introduction

Accurate segmentation of three-dimensional dental structures is fundamental to orthodontic diagnosis, treatment planning, prosthodontics, and a broad range of digital dentistry applications [1]. With the growing availability of intraoral scanners and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) [2], large-scale acquisition of high-fidelity 3D dental models has become increasingly accessible. Such high-resolution data preserve detailed geometric and topological information, providing a robust foundation for achieving clinically reliable, fine-grained segmentation outcomes.

However, performing automatic segmentation directly on high-resolution 3D dental meshes remains highly challenging. Dental models typically consist of hundreds of thousands of vertices, imposing substantial burdens on computational cost, GPU memory consumption, and inference efficiency for deep learning-based approaches [3]. Most existing approaches to 3D dental segmentation reduce computational cost by downsampling the input data. While such strategies partially alleviate the computational burden, they inevitably sacrifice fine-grained geometric details at tooth boundaries, which are critical for accurate delineation. This limitation becomes particularly pronounced in complex clinical scenarios, such as cases with missing teeth or partially scanned data, where segmentation performance often degrades substantially. Consequently, segmentation pipelines that rely heavily on downsampling struggle to meet the practical demands of applications requiring both high precision and strong robustness. Consequently, how to effectively exploit the rich geometric information inherent in raw high-resolution meshes while maintaining computational efficiency remains an open and fundamental problem in 3D dental segmentation.

In recent years, advances in geometric deep learning have opened new avenues for overcoming these limitations. DiffusionNet is a diffusion-operator-based geometric learning framework that propagates features by simulating diffusion processes on surfaces, thereby avoiding reliance on regular convolutional structures. This design enables DiffusionNet to effectively capture complex geometric relationships while maintaining relatively low computational complexity. Prior studies have demonstrated that DiffusionNet performs robustly on high-resolution meshes with more than 100,000 vertices and achieves nearly 90% segmentation accuracy on RNA molecular datasets comprising over 20,000 vertices [4], highlighting its strong potential for high-resolution geometric learning tasks. These characteristics make DiffusionNet an appealing and effective foundation for addressing the challenges of large-scale, high-resolution 3D dental segmentation.

Although DiffusionNet demonstrates notable advantages in high-resolution geometric modeling, its original design primarily emphasizes the global propagation of diffusion features. As a result, it lacks targeted modeling of direction-sensitive geometric information and channel-wise feature selection, both of which are critical for tooth segmentation. This limitation constrains its ability to accurately capture complex local morphologies and fine-grained structural boundaries.

Motivated by the above challenges, we propose DiffusionNet++, an enhanced high-resolution 3D dental segmentation framework designed to achieve both efficient and robust segmentation. Building upon the standard DiffusionNet architecture, our method introduces two key modifications tailored to the geometric characteristics of 3D teeth:

- Direction-sensitive normal features, which strengthen the model’s ability to capture local geometric patterns and curvature-related variations.

- A lightweight Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) channel-attention module, enabling the network to adaptively emphasize informative features while suppressing redundant channels, thereby improving the discriminative power of the learned representations.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- 1.

- This study introduces DiffusionNet++, an enhanced framework for high-resolution 3D tooth segmentation. By integrating normal features and a lightweight SE channel-attention mechanism, the method substantially improves segmentation performance without incurring significant additional computational cost. Comprehensive comparative experiments further demonstrate that the coordinates + normals constitute the optimal input-feature configuration for 3D dental segmentation.

- 2.

- DiffusionNet++ demonstrates strong robustness and reliability across diverse and challenging clinical scenarios. The proposed method consistently achieves superior results on cases involving missing teeth and partially scanned data. Ultimately, it attains an overall accuracy (OA) of 95.87% and a mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) of 89.80%, providing compelling evidence of its effectiveness and practical applicability.

- 3.

- This study provides the first systematic investigation on the automatic segmentation of raw high-resolution 3D dental meshes. The proposed approach overcomes the prevailing reliance on aggressive downsampling in existing methods, offering a new pathway for preserving fine-grained geometric details and achieving clinically viable accuracy.

2. Related Works

2.1. 3D Data Segmentation

Three-dimensional data segmentation is an important research area in computer graphics and computer vision. This technique is widely applied in object reconstruction, shape analysis, and medical image processing. Its primary goal is to partition 3D data into structurally coherent or functionally independent subregions for further analysis and processing. Currently, the main representations of 3D data include voxel, view, point cloud, and mesh. Each representation has distinct characteristics, leading to different segmentation approaches.

- 1.

- Voxel Segmentation: Voxel, short for volumetric pixel, is analogous to a pixel in 2D space but occupies volume in 3D space. Each voxel can store information such as color and density, making it well suited for representing objects with regular structures. Daniel Maturana et al. proposed VoxNet [5], which employs a 3D convolutional neural network (CNN) to process voxel data; however, voxel sparsity leads to increased computational costs. To address this limitation, Hu et al. proposed VMNet [6], a 3D deep network that combines voxel and mesh representations, leveraging both Euclidean and geodesic information to enhance the accuracy of sparse voxel segmentation. Nevertheless, when processing high-resolution data, the number of model parameters increases significantly, limiting the model’s generalization ability. Consequently, voxel-based methods incur substantial computational costs, posing challenges in balancing spatial resolution and computational efficiency.

- 2.

- View Segmentation: View-based segmentation methods project 3D objects from multiple viewpoints to generate 2D images, upon which conventional 2D image segmentation techniques are applied to achieve 3D segmentation. Su et al. proposed the MVCNN [7], which renders 3D data from 12 predefined viewpoints and employs a two-stage CNN architecture for feature extraction. The first stage utilizes a shared-parameter CNN to extract features from each view, followed by max-pooling to aggregate multi-view information, while the second stage learns a compact 3D shape representation. To address variations in recognition performance across different viewpoints, Feng et al. introduced GVCNN [8], which groups views, assigns weights, and performs pooling within each group, and subsequently fuses the group-level features to obtain a holistic representation. Furthermore, Abhijit Kundu et al. proposed Virtual Multi-View Fusion [9], which generates virtual views, renders synthetic images, trains a 2D semantic segmentation model, and fuses multi-view predictions onto 3D mesh vertices for 3D scene segmentation. While view-based methods effectively leverage well-established 2D image segmentation techniques with relatively low computational cost, they are fundamentally constrained by their 2D projections. Consequently, these methods struggle to fully capture 3D topological structures and geometric relationships. In addition, complex geometries often lead to information loss due to occlusions from certain viewpoints.

- 3.

- Point cloud segmentation: Point cloud is an unordered three-dimensional data representation consisting of a set of points, each with 3D coordinates (x, y, z), and may include additional attributes such as color and normal vectors. PointNet [10], proposed by researchers at Stanford University in 2017, is a deep learning network specifically designed for processing point cloud data. It consists of a point cloud feature extractor and a global feature aggregator and performs well in 3D object classification and segmentation. PointNet++ [11] is an improved version of PointNet proposed by Qi et al. It addresses PointNet’s limitation of ignoring local structures. PointNet++ employs a multi-scale hierarchical aggregation strategy, enabling the model to better capture local information, particularly in cases of uneven point cloud density. Weng et al. proposed the 3D-PAM [12] to enhance 3D point cloud semantic segmentation. By incorporating plane-guided information, 3D-PAM improves the ability to recognize object boundaries and large surface areas while capturing the global scene structure, effectively overcoming the limitations of traditional methods in these aspects. Point cloud data is inherently unstructured, allowing flexible adaptation to objects of various shapes. However, its unordered nature hinders the modeling of complex topological relationships, which negatively affects segmentation accuracy.

- 4.

- Mesh Segmentation: Three-dimensional mesh data is a collection of vertices, edges, and faces. Feng et al. proposed MeshNet [13], which treats mesh faces as fundamental units. It employs multi-level feature extraction to capture local details and global topological information for segmentation. V. V. Singh et al. introduced MeshNet++ [14], an enhanced version of MeshNet equipped with specialized convolution and pooling modules for multi-scale local feature learning. Alon Lahav et al. proposed MeshWalker [15], which performs random walks along the mesh surface to extract geometric and topological features, followed by an RNN for segmentation. Hanocka et al. introduced MeshCNN [16], a pioneering architecture that operates directly on mesh edges. It designs novel edge-based convolution, pooling, and unpooling operations: the convolution aggregates features from an edge and its four neighboring edges, while the pooling operation collapses edges on the mesh surface, allowing the network to effectively capture fine-grained local geometry. Sharp et al. proposed DiffusionNet [4], which replaces traditional, computationally expensive geometric convolutions and pooling layers with a learnable diffusion process. By independently learning diffusion times for each feature channel, the network dynamically adapts its receptive field, enabling effective modeling of both local geometric details and global structural information. A multilayer perceptron (MLP) is then employed to nonlinearly fuse and enhance the multi-scale diffused features, leading to robust and accurate performance on 3D classification and segmentation tasks.

2.2. Three-Dimensional Tooth Segmentation

Three-dimensional tooth segmentation is a crucial task in medical image processing and computer-aided design. Its goal is to separate each individual tooth from complex dental data, ensuring that the tooth and gum positions comply with the labeling standards defined by the International Dental Federation (FDI) [17]. However, due to the intricate morphology of teeth, their close spatial arrangement, and the high cost of data annotation, 3D tooth segmentation remains technically challenging. Depending on the different representation methods of 3D data, the 3D tooth segmentation methods are also different.

- 1.

- Voxel Segmentation: Cui et al. proposed ToothNet [18], a two-stage deep learning framework for 3D tooth segmentation. In the first stage, a deep supervision network is trained to extract tooth edge information. In the second stage, the extracted edge information and original data are input into a 3D Region Proposal Network (RPN), together with spatial relationship features of the teeth, to enhance tooth recognition accuracy. Ahn et al. proposed the WCTN [19], which integrates voxel grid division, weighted sparse convolution, and global feature extraction. It employs an adaptive feature fusion strategy to effectively integrate local and global information, thus making it particularly suitable for uniformly dense dental data.

- 2.

- View Segmentation: Zhang et al. proposed a view-based segmentation approach utilizing the harmonic field parameter space [20]. The method performs harmonic parameterization, projection, and data augmentation on labeled 3D dental data to generate a corresponding 2D image dataset for training. The segmentation mask is obtained through image segmentation approaches and then mapped back to 3D space for further processing. Mochen Yu et al. introduced a deformable exemplar-based conditional random field model [21] for tooth segmentation and mapping back to 3D. Ahmed Rekik et al. proposed a multi-stage dental segmentation framework, TSegLab [22], in which 3D dental geometries are first unfolded into 2D representations via curvature-based and harmonic mapping. A coarse segmentation is then performed using Mask R-CNN, after which the results are projected back into 3D space and further refined through a graph neural network (GNN) to explicitly model tooth geometry and spatial relationships. Kim Taeksoo et al. proposed a 3D tooth segmentation method based on Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) [23]. Their approach slices 3D teeth into 2D images along the horizontal direction, fills the missing areas via generative modeling, and then stacks and reconstructs the 3D model to complete the segmentation. TJ Jang et al. presented a stepwise segmentation strategy that integrates both 2D and 3D information [24]. Their method first identifies individual tooth regions in 2D images and localizes the corresponding three-dimensional regions of interest (ROIs), after which fine-grained segmentation is performed directly in 3D space. While view-based segmentation methods are effective for simple tooth models or single-tooth segmentation, their performance degrades significantly in complex cases involving tooth crowding or misalignment.

- 3.

- Point cloud segmentation: Joon Im et al. employed a Dynamic Graph Convolutional Neural Network (DGCNN) to achieve automatic segmentation of 3D dental point cloud data [25]. By dynamically constructing graph structures within local neighborhoods, their method captures and models the underlying geometric features of the point clouds. Farhad Ghazvinian Zanjani et al. proposed Mask-MCNet [26], a Mask R-CNN-based framework for 3D dental point cloud segmentation. The method achieves instance-level segmentation by predicting 3D bounding boxes for each tooth and then segmenting the point clouds within each bounding box. Cui et al. proposed TSegNet [27], a two-stage network designed for the segmentation of 3D dental point cloud data, with PointNet++ serving as the backbone. In the first stage, the farthest point sampling (FPS) method is applied to calculate the centroid of each tooth. The centroid information is subsequently used to segment individual teeth, and this hierarchical framework enhances the model’s capability to handle complex dental geometries. Similarly, Qiu et al. proposed the Darch algorithm [28], which refines centroid estimation by incorporating the dental arch structure rather than relying solely on farthest point sampling. Specifically, a Bézier curve is utilized to generate an initial dental arch, which is further refined using a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN). Based on the refined dental arch, an arch-aware point sampling (APS) method is proposed to guide accurate centroid estimation and improve tooth segmentation precision.

- 4.

- Mesh Segmentation: Lian et al. proposed MeshSegNet [29], an end-to-end deep learning framework for the automatic segmentation of 3D dental mesh data. MeshSegNet employs a graph-based learning module to extract multi-scale local features and integrates local and global geometric information to enhance segmentation accuracy. Building upon this, Wu et al. developed TS-MDL [30], a two-stage model that utilizes an efficient variant of MeshSegNet, iMeshSegNet, for initial dental segmentation in the first stage, followed by PointNet to regress dental surface heatmaps for fine-grained shape refinement. Zhao et al. proposed TSGCN [31], which uses a dual-stream architecture to simultaneously learn coordinates and normal vector features. It integrates self-attention mechanisms to enhance global feature processing, thus achieving excellent results in dental shape segmentation. Li et al. introduced ThisNet [32], which emphasizes the dental region and improves segmentation and labeling accuracy by combining a dental similarity module with global context information. Furthermore, Zheng et al. proposed TeethGNN [33], a graph neural network for dental mesh segmentation. It employs a dual-branch architecture to predict triangle labels and centroid offsets and then applies the clustering algorithm to separate adjacent teeth. This design enables precise boundary localization and effectively addresses the issue of incomplete segmentation. Lucas Krenmayr et al. introduced DilatedToothSegNet [34], a graph neural network-based approach for 3D dental segmentation. By incorporating dilated edge convolution to expand the receptive field, the method captures long-range geometric dependencies, resulting in a substantial improvement in segmentation accuracy on 3D dental meshes.

3. Methods

3.1. Network Structure

This study proposes DiffusionNet++, an automatic high-resolution 3D tooth segmentation framework based on a learnable diffusion mechanism, aimed at achieving precise, robust and efficient segmentation of complex dental geometries. Compared with the standard DiffusionNet, DiffusionNet++ introduces targeted enhancements in both feature modeling and network architecture, enabling more effective capture of local geometric details and global topological structures of teeth.

At the input stage, normal features are incorporated to enhance the model’s sensitivity to local curvature and surface orientation. Systematic feature comparison experiments demonstrate that the coordinates + normals input configuration yields the best performance for tooth segmentation, effectively preserving global spatial context while substantially strengthening the delineation of fine-grained local boundaries.

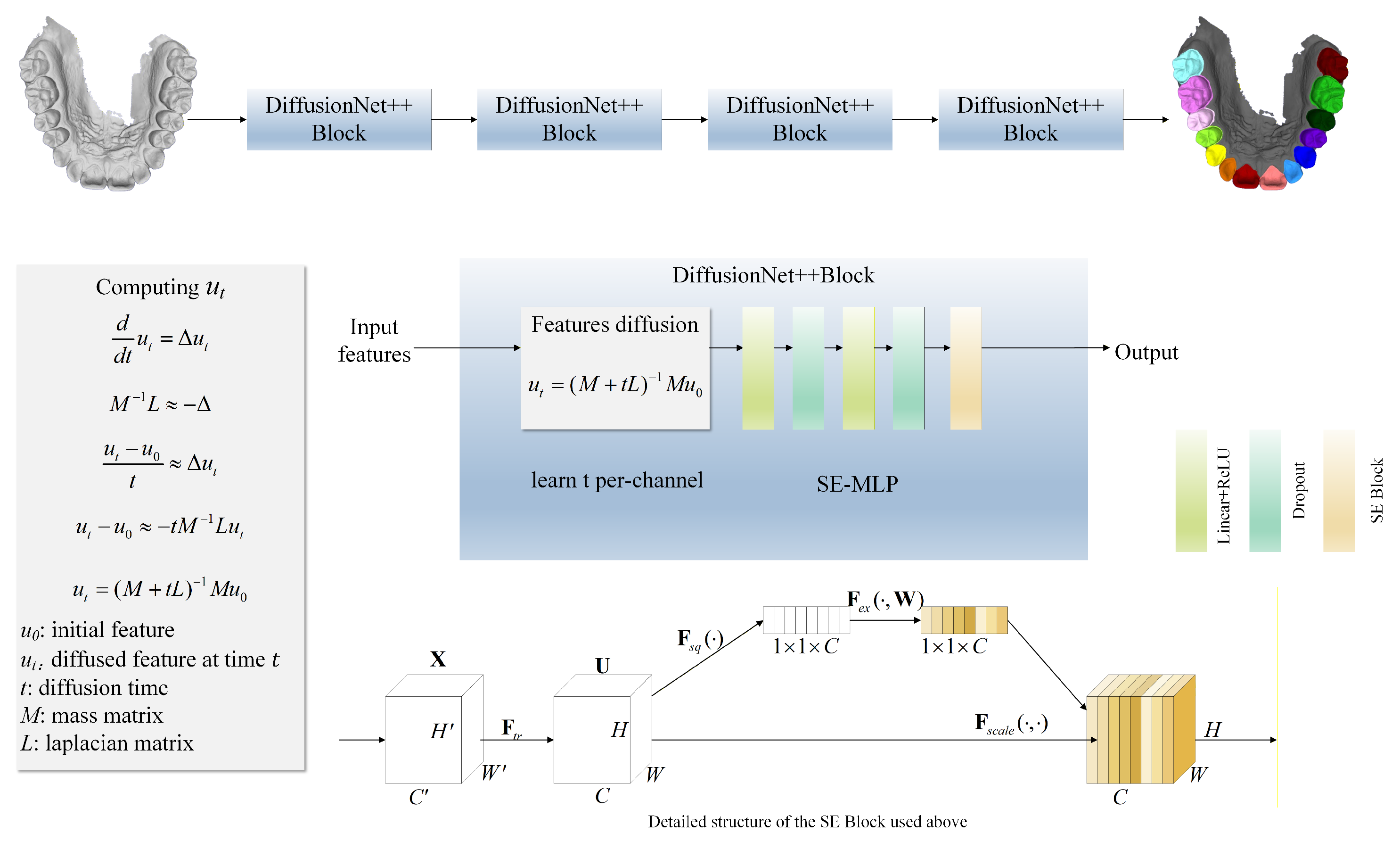

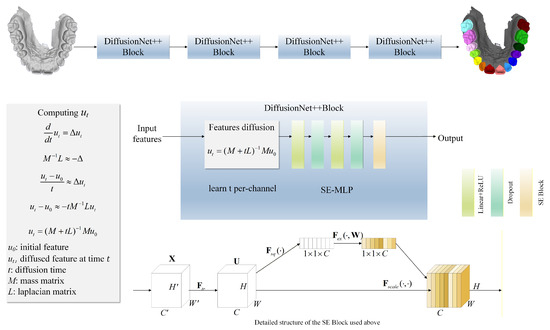

In terms of network architecture, DiffusionNet++ is composed of multiple sequential DiffusionNet++ Blocks, each integrating two core components. The first is a feature diffusion module, designed to model local and global geometric relationships across multiple scales. The second is an SE-MLP module, which leverages a SE channel attention mechanism to adaptively amplify discriminative features while suppressing redundant information, thereby enhancing the representational capacity. Through this architectural design, the model is able to precisely capture fine-grained structural details from high-resolution dental data while maintaining semantic consistency and robustness. The overall architecture of DiffusionNet++ is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Network structure flow chart. The model is composed of a series of DiffusionNet++ Blocks, each comprising a feature diffusion module and an SE-MLP. The SE-MLP integrates an SE Block within an MLP to perform channel-wise feature reweighting.

3.2. Input Features

The standard DiffusionNet utilizes vertex coordinates and the Heat Kernel Signature (HKS) as its input features. Vertex coordinates encode the absolute spatial positions of each point on the 3D mesh, providing the foundational information for the network to capture local geometric structures. The HKS characterizes the residual heat at each surface point across multiple diffusion time scales, enabling it to effectively capture smooth variations of global geometric structure and thus making it widely adopted in shape analysis tasks. However, HKS is inherently isotropic, rendering it insensitive to directional changes. As a result, its representational capacity is substantially limited in regions exhibiting pronounced directional variation and high curvature, such as sharp cusps, ridges, and grooves on dental surfaces, where detailed local geometry is dominated by anisotropic structural cues. Consequently, HKS alone cannot adequately encode these direction-dependent, fine-scale geometric features.

In contrast, the normal vector is a unit vector defined at each vertex of the mesh, perpendicular to the local surface where that vertex lies. Normal vectors not only characterize the outward–inward orientation and local inclination of the surface but also reflect the intensity of curvature variations through changes in normals between adjacent vertices. For instance, sharp grooves or cusps on dental surfaces exhibit pronounced shifts in normal direction, whereas smooth regions display only gradual variation. Incorporating normal vectors into the input feature space therefore enables the network to perceive and discriminate geometric differences along specific orientations during the diffusion process, enhancing its sensitivity to direction-dependent structures and improving its ability to recognize complex geometric patterns.

Three-dimensional tooth segmentation is a task that is highly sensitive to local variations in surface orientation and curvature, with its central challenge lying in the accurate delineation of fine boundaries and highly curved structures. The HKS, as an inherently isotropic descriptor, lacks sufficient sensitivity to directional differences and local curvature variations. From a geometric standpoint, HKS is not a strongly task-relevant feature for 3D tooth segmentation. Consequently, incorporating HKS as an input feature in tooth segmentation models often fails to provide the critical local information required for precise boundary discrimination. Moreover, when combined with highly discriminative features such as surface normals, HKS may introduce redundant or even disruptive information. This redundancy can attenuate the model’s ability to focus on key local regions during feature diffusion and fusion, ultimately constraining segmentation performance and, in some cases, leading to measurable performance degradation.

Building on the above analysis, this study adopts the coordinates + normals combination as the input feature in DiffusionNet++ to enhance the model’s capacity for feature representation in direction-sensitive regions. This design aligns the input features more closely with the inherent characteristics of the 3D tooth segmentation task, thereby effectively improving the model’s segmentation accuracy and stability.

3.3. Features Diffusion

Compared with traditional convolution or pooling operations, the feature diffusion mechanism offers a lighter-weight, more stable, and inherently more robust approach to feature propagation in deep learning models [35]. Its core principle is rooted in the heat diffusion equation: each feature channel undergoes an independent diffusion process, with the diffusion time t treated as a learnable parameter. This design allows different channels to automatically acquire receptive fields of varying scales. As , the diffusion process becomes negligible, preserving primarily local geometric information. In contrast, as , the diffusion process progressively spans the entire surface, causing the features to converge toward a global average, which is conceptually analogous to global pooling. Unlike conventional convolutions whose kernel sizes are fixed and thus impose strict limits on the receptive field, feature diffusion enables dynamic integration of local and global information. As a result, it provides a natural advantage when modeling highly complex geometric structures with pronounced curvature variations, such as those found in high-resolution dental surfaces. In continuous space, the diffusion of features over a surface can be formally described by the heat diffusion equation:

Here, denotes the scalar field (i.e., the feature representation) at diffusion time t, and represents the Laplace–Beltrami operator, which governs diffusion on curved surfaces. The solution of this equation evolves the initial feature field over time t, producing its diffused form and thereby enabling continuous propagation of features across the surface.

However, the 3D dental data used in this study are represented as discrete triangular meshes, rendering the continuous Laplace–Beltrami operator inapplicable in its original form. Consequently, a discrete approximation is required. In practice, the continuous operator −Δ can be approximated using the Laplacian matrix L together with the mass matrix M, such that

The matrix L denotes the discrete Laplace–Beltrami operator, which approximates the second-order differential operator defined on a surface and thus characterizes geometric variations on a 3D mesh. The Laplacian matrix is defined as

Here, i and j denote vertex indices, while and represent the interior angles opposite to edge (i, j) in the two adjacent triangles. The diagonal entries are defined such that the sum of each row of the Laplacian matrix equals zero. The mass matrix encodes the area associated with each vertex, and its equation is

denotes the geometric area of a triangular face incident to vertex i, and the factor reflects the uniform distribution of the triangle’s area among its three vertices. Both the Laplacian matrix and the mass matrix are computed using the cotan_laplacian and vertex_areas functions provided by the potpourri3d geometric processing library.

With the Laplacian matrix L and mass matrix M obtained, the discretized heat diffusion equation can be used to model feature propagation on the mesh. In this work, we employ an implicit time-stepping scheme to solve the diffusion process. By discretizing the continuous heat equation along the temporal dimension with a time step t, we obtain

Substituting the Laplacian matrix L and the mass matrix M into the formulation yields

Rearranging the equation yields the final form:

Solving the above equation yields the diffused feature at a given diffusion time t. The diffusion time t is not manually fixed as a hyperparameter but is a learnable parameter, introduced independently for each feature channel and initialized uniformly to 0. During training, t is automatically updated through backpropagation, enabling the model to adaptively adjust the diffusion extent according to task requirements. This design allows the network to effectively capture geometric and semantic information across multiple scales. In contrast to conventional convolutional networks which rely on manually designed kernel sizes or complex hierarchical downsampling and pooling structures to achieve multi-scale modeling, the diffusion operation offers a more flexible and intrinsically multi-scale alternative. It avoids explicit local parameterization and circumvents the intricate topological operations often required for constructing multi-resolution pathways.

Because the diffusion operation fundamentally reduces to solving a well-posed system of linear equations, it is computationally stable and highly efficient, without incurring the substantial overhead that convolution or pooling operations introduce as data resolution increases. This mathematical advantage enables the model to maintain excellent scalability and numerical stability when processing high-resolution 3D geometric data, while producing feature representations that are globally coherent yet sensitive to fine-grained local structure.

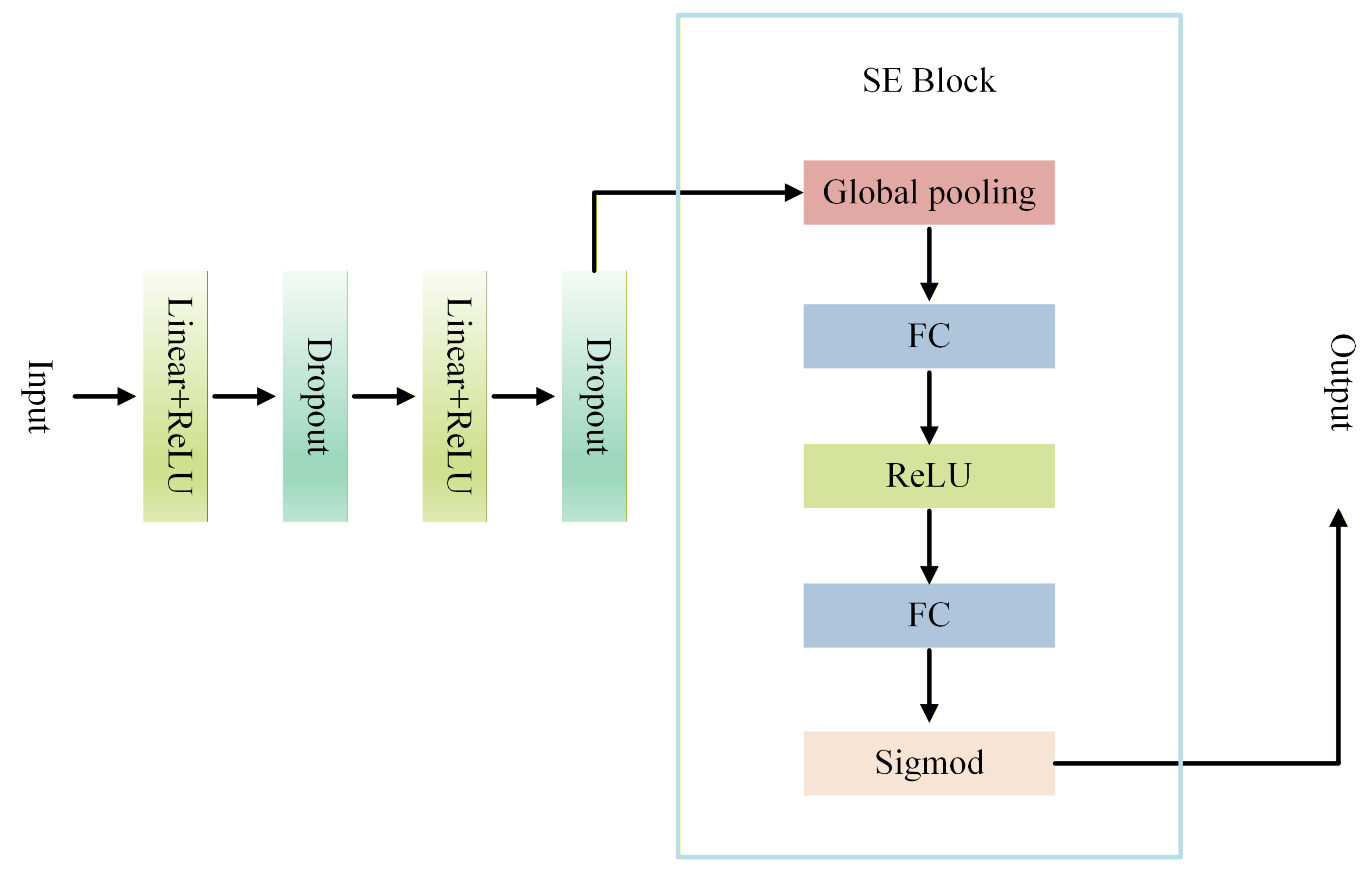

3.4. SE-MLP

After feature propagation through diffusion, the network must further integrate geometric information across multiple scales and directions. At this stage, the standard DiffusionNet relies on a multilayer perceptron (MLP) to perform critical feature mixing and nonlinear transformations. However, the conventional MLP treats all feature channels uniformly: linear layers apply identical weights across channels, and activation functions are applied consistently to each channel. This uniform treatment overlooks the varying contributions of different feature channels in complex 3D geometric tasks, limiting the network’s ability to dynamically modulate channel importance in response to local geometry and regional semantics, and consequently constraining the expressive power of the learned features [36].

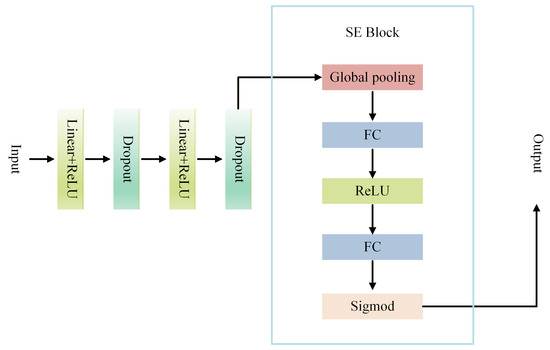

To address this limitation, we introduce an enhanced SE-MLP architecture that incorporates the SE channel attention mechanism into the conventional MLP framework, transforming the MLP from indiscriminate channel processing to dynamically focusing on salient channels. By explicitly modeling inter-channel dependencies, the SE-MLP emphasizes discriminative geometric features while suppressing redundant or noisy information in complex 3D dental data, thereby substantially enhancing both feature selection and overall representational capacity. The overall architecture is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of SE-MLP.

We adopt the ReLU activation function due to its simplicity, computational efficiency, and effectiveness in alleviating the vanishing gradient problem. In the context of high-resolution 3D tooth segmentation, ReLU facilitates stable gradient propagation, which is essential for learning fine-grained geometric details [37]. Although alternative activation functions such as GELU or tanh were also considered, they were empirically found to be less efficient and more prone to saturation, making them less suitable for our setting.

The SE Block implements channel-wise attention through the following three steps, dynamically modulating the importance of each channel in feature representation:

- 1.

- Squeeze: The input features are globally average-pooled across the spatial dimensions, compressing the spatial distribution of each channel into a single global statistic. This operation effectively captures each channel’s overall contribution to the feature representation and provides a foundation for subsequent channel weight modeling.

- 2.

- Excitation: Two consecutive fully connected layers are employed to learn inter-channel dependencies. The first layer performs channel-wise dimensionality reduction to reduce parameters and extract compact features, followed by a ReLU activation. The second layer restores the original channel dimension to model the complete distribution of channel importance.

- 3.

- Scale: The learned channel weights are passed through a Sigmoid function to map them to the range [0,1] and then multiplied with the original features in a channel-wise manner, achieving adaptive feature recalibration. Important channels are amplified, while less relevant channels are suppressed.

By integrating the SE Block into the MLP to form the SE-MLP architecture, the model achieves fine-grained, channel-wise adaptive feature modulation. Specifically, the SE Block performs a squeeze-and-excitation operation on each channel of the MLP output: spatial information within each channel is first aggregated via global average pooling to capture its overall importance within the geometric structure; this is followed by two small fully connected layers that generate channel attention weights, which are then used to recalibrate the original channel features. Consequently, the high-dimensional feature vectors produced by the MLP are dynamically reweighted by the SE Block, enabling the model to automatically emphasize locally discriminative structures in 3D dental data while suppressing redundant or irrelevant features.

4. Experiments

4.1. Dataset and Preprocessing

The dataset used in this study consists of 280 high-resolution 3D intraoral scans, each comprising approximately 200,000 vertices, and was divided into training and testing sets at an 8:2 ratio. This dataset captures a wide spectrum of clinically relevant irregularities, including missing teeth and partially scanned data. Segmentation was performed directly on the original high-resolution 3D dental data, preserving fine-grained geometric details. No data augmentation strategies, such as rotation or scaling, are applied during preprocessing. To reduce variations in pose across samples, principal component analysis (PCA) was applied to center the coordinates and align the primary axes of all inputs, thereby enhancing visibility and standardizing the 3D orientation [38].

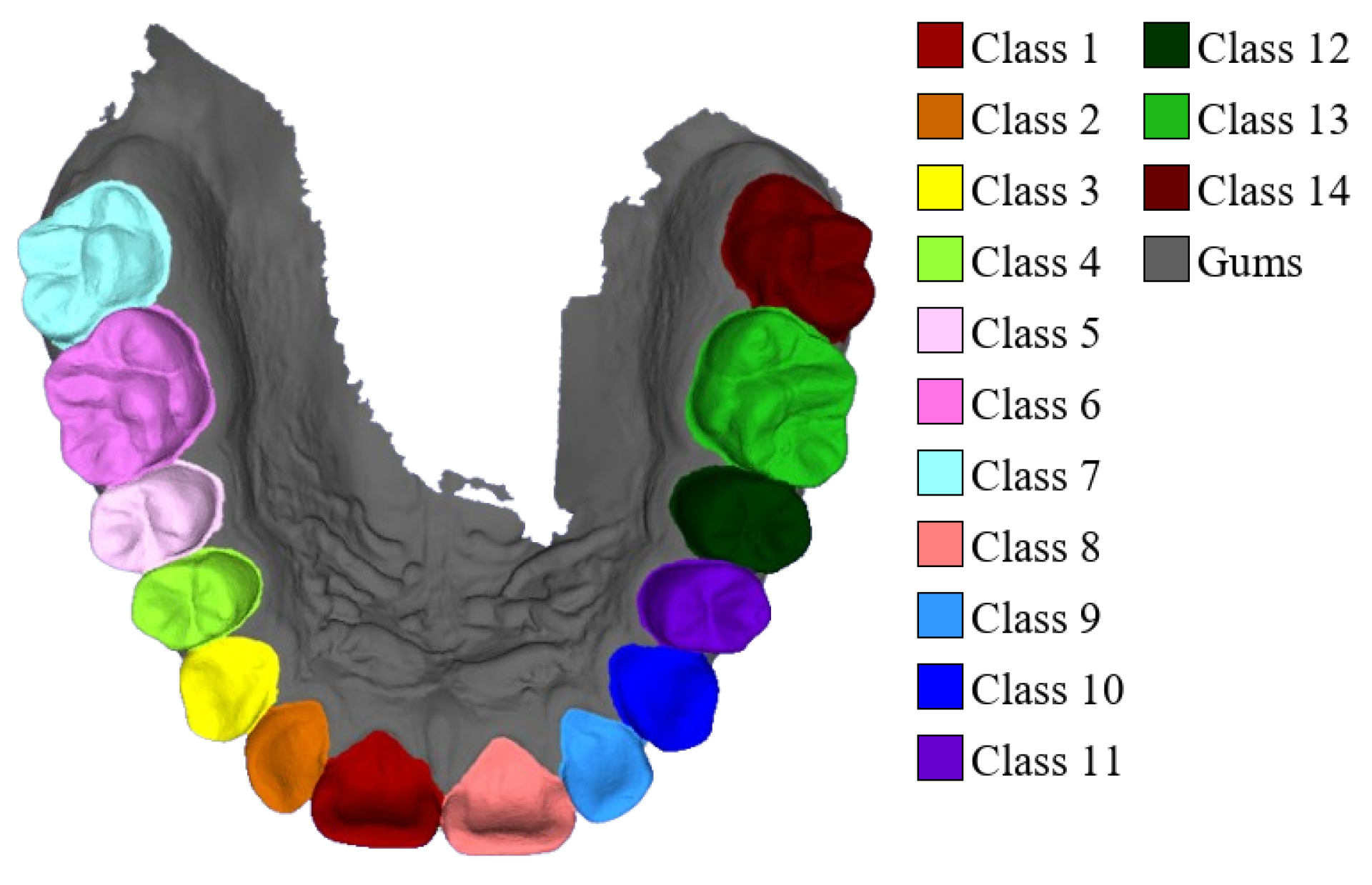

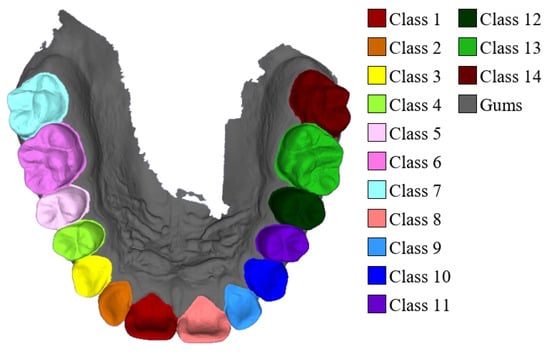

For semantic labeling, third molars (wisdom teeth) were excluded, with each sample containing up to fourteen teeth and the gums, resulting in fifteen semantic categories. The precise category distribution is illustrated in Figure 3. All samples were manually annotated using Blender 4.1 to ensure high-quality labels and accurate geometric boundaries. The dataset has been made publicly available at https://github.com/littlezhang231/Data (accessed on 12 December 2025).

Figure 3.

Fourteen tooth types and gums.

4.2. Experimental Setup and Evaluation Metrics

The proposed model was implemented in PyTorch 2.3.0 and trained on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 GPU. Training was guided by the cross-entropy loss function, and the Adam optimizer was employed with a batch size of 1 for 200 epochs. The initial learning rate was set to 0.001, maintained at this value for the first 150 epochs, and then linearly decayed over the final 50 epochs to ensure stable convergence.

To evaluate the performance of the model, we adopt three commonly used and representative evaluation metrics: Overall Accuracy (OA), Intersection over Union (IoU) for each category, and mean Intersection over Union (mIoU). OA is defined as the ratio of the number of samples correctly classified to the total number of samples, which is used to measure the overall classification accuracy of the model across all data. IoU is one of the core evaluation metrics widely used in 3D segmentation tasks, which can effectively reflect the segmentation accuracy of the model in different categories. It is calculated as the ratio of the intersection to the union between the predicted region and the ground truth region. mIoU comprehensively assesses the overall segmentation performance of the model in all categories by taking the arithmetic mean of the IoU of all categories. If the data consists of k categories, represents the prediction category as i and the actual category as j, and represents the prediction category as i and the actual category also as i. On this basis, the calculation formulas can be expressed as

4.3. Experimental Results

Given the current lack of methods capable of stably operating on extremely high-resolution 3D data in both dental segmentation and the broader 3D data segmentation domain, this study focuses on comparative analysis with the standard DiffusionNet to ensure fair evaluation and interpretability of methodological improvements. Building on the standard DiffusionNet architecture, we introduce direction-sensitive normal vector features and the SE channel attention mechanism to enhance the model’s representational capacity for high-resolution 3D dental segmentation. To systematically assess the effectiveness of these enhancements, we construct two models:

- Standard DiffusionNet without attention mechanisms.

- DiffusionNet++, the improved model integrating the SE channel attention mechanism.

For these two models, we conducted systematic comparative experiments under multiple input feature configurations (e.g., coordinates; coordinates + HKS) to evaluate the effectiveness of normal features and the SE channel attention mechanism, as well as to identify the optimal feature combination for high-resolution 3D dental segmentation. All models were evaluated under the same experimental settings described in Section 4.2, ensuring the comparability of results across different input feature combinations. To further assess the models’ robustness and generalization across diverse tooth morphologies and complex geometric structures, we performed experiments on datasets containing missing teeth and partially scanned data. Both quantitative and qualitative evaluations were provided to offer a comprehensive assessment of model performance.

4.3.1. Qualitative Experiments

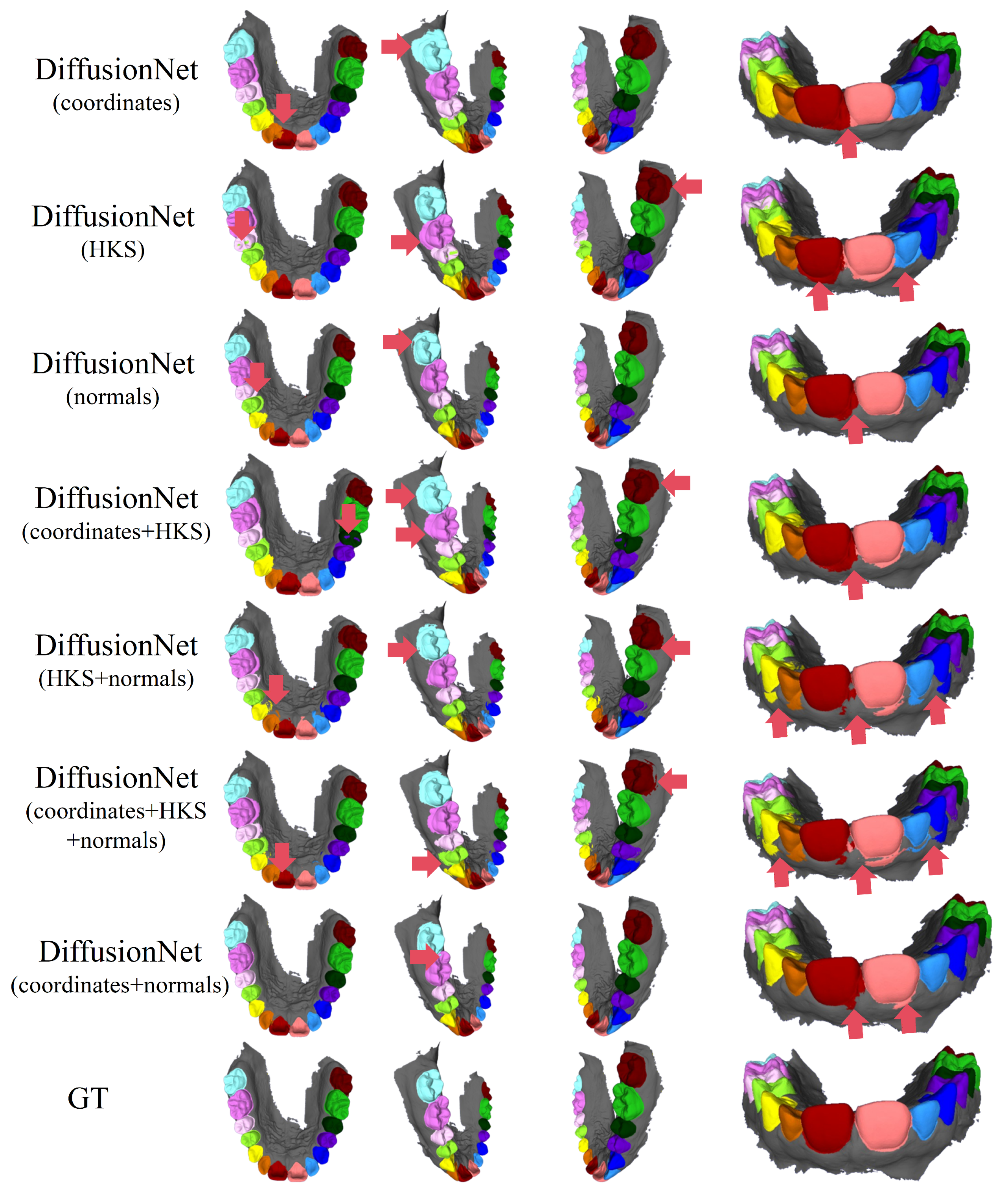

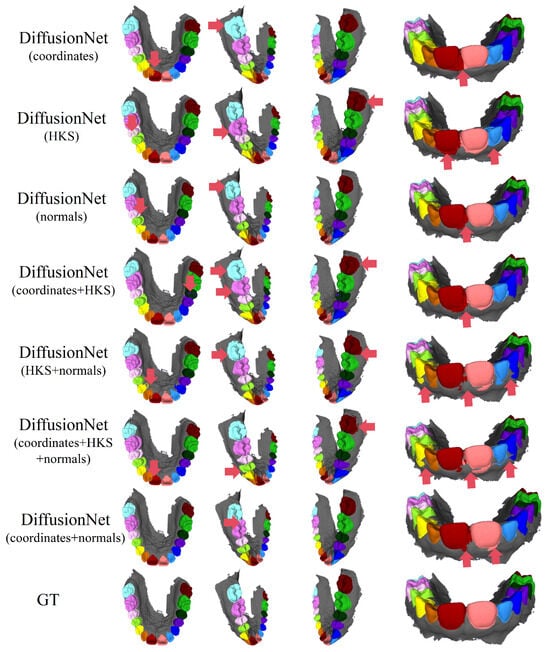

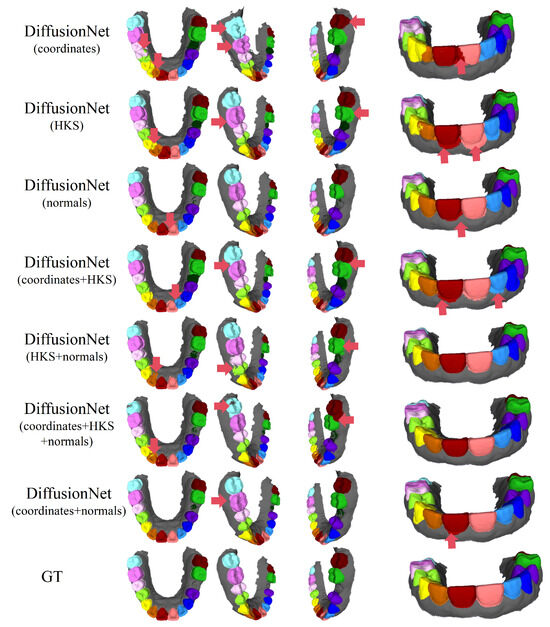

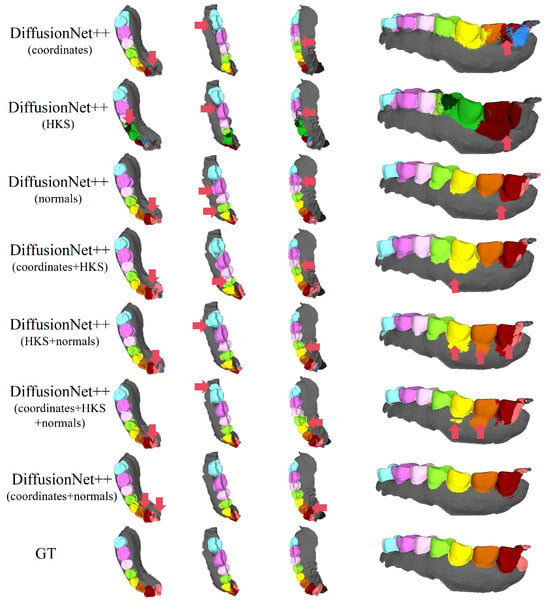

Figure 4 and Figure 5 present the qualitative segmentation results of the standard DiffusionNet under different input feature combinations. As can be clearly observed, when the model employs coordinates, HKS, or coordinates + HKS as input features, the resulting segmentations commonly exhibit blurred boundaries, local over-segmentation, and adhesion between adjacent teeth. Under these configurations, the model struggles to accurately capture the complex and fine-grained structural boundaries between individual teeth.

Figure 4.

The qualitative experimental comparison results of DiffusionNet. Different colors indicate different tooth categories, as defined in Figure 3. The red arrows highlight regions with segmentation errors.

Figure 5.

The qualitative comparison of DiffusionNet results with zoomed-in views. Different colors indicate different tooth categories, as defined in Figure 3.

In contrast, when normal vectors are incorporated into the input features, including normals, HKS + normals, coordinates + HKS + normals, and coordinates + normals, the segmentation performance of model is markedly improved. Specifically, feature combinations involving normal vectors exhibit superior preservation of global tooth morphology and more coherent, well-defined boundaries in fine-detail regions, resulting in enhanced structural continuity and segmentation accuracy.

Overall, input feature configurations that include normal vectors consistently outperform those without them. Among all normal-enhanced feature combinations, the coordinates + normals configuration yields the most outstanding results, producing clear, stable segmentations with virtually no noticeable missegmentation. These findings provide strong evidence for the critical role of normal vectors in 3D dental segmentation and highlight their unique effectiveness in capturing discriminative local geometric structures.

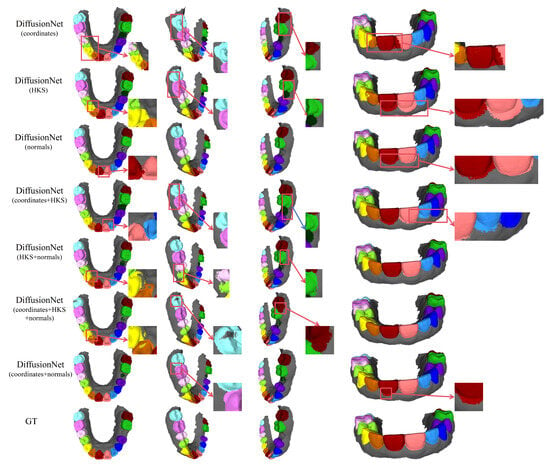

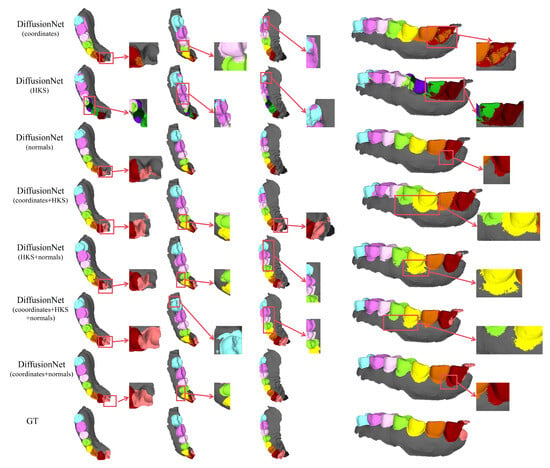

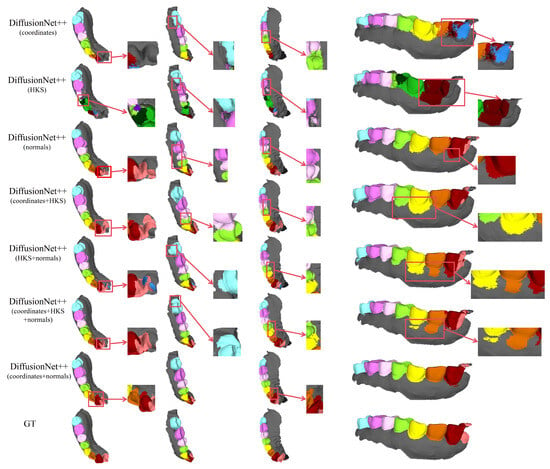

Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 present the qualitative segmentation results of DiffusionNet under two challenging scenarios: datasets with missing teeth and partially scanned data. Despite the pronounced geometric defects and structural incompleteness inherent in these data, the model is able to recover the main tooth structures with high fidelity when normals are incorporated into the input features. In particular, clear and continuous segmentation boundaries are preserved along missing regions and incomplete edges, demonstrating strong structural consistency.

Figure 6.

The qualitative experimental comparison results of DiffusionNet on missing teeth. Different colors indicate different tooth categories, as defined in Figure 3. The red arrows highlight regions with segmentation errors.

Figure 7.

The qualitative comparison of DiffusionNet results with zoomed-in views on missing teeth. Different colors indicate different tooth categories, as defined in Figure 3.

Figure 8.

The qualitative experimental comparison results of DiffusionNet on partially scanned data. Different colors indicate different tooth categories, as defined in Figure 3. The red arrows highlight regions with segmentation errors.

Figure 9.

The qualitative comparison of DiffusionNet results with zoomed-in views on partially scanned data. Different colors indicate different tooth categories, as defined in Figure 3.

Among all normal-enhanced feature configurations, the coordinates + normals combination exhibits the most outstanding performance. This configuration not only substantially reduces local mis-segmentation but also more accurately delineates the boundaries between adjacent teeth and missing regions, thereby demonstrating superior adaptability and stability under complex deformations and localized geometric loss.

In contrast, when the model relies solely on coordinates, HKS, or their combination (coordinates + HKS), pronounced under-segmentation and misclassification are consistently observed near missing regions and along incomplete scan boundaries. These results indicate that global positional information or diffusion-spectrum-based features alone are insufficient to effectively capture local geometric variations under structurally incomplete conditions. By contrast, the local surface orientation information provided by normal vectors compensates for geometric ambiguity introduced by missing data, thereby significantly enhancing segmentation robustness in complex defect scenarios.

In conclusion, these findings conclusively demonstrate the effectiveness of normal features under missing and incomplete data conditions and further confirm that coordinates + normals constitute the most robust and high-performing input feature combination for DiffusionNet in complex 3D dental segmentation tasks.

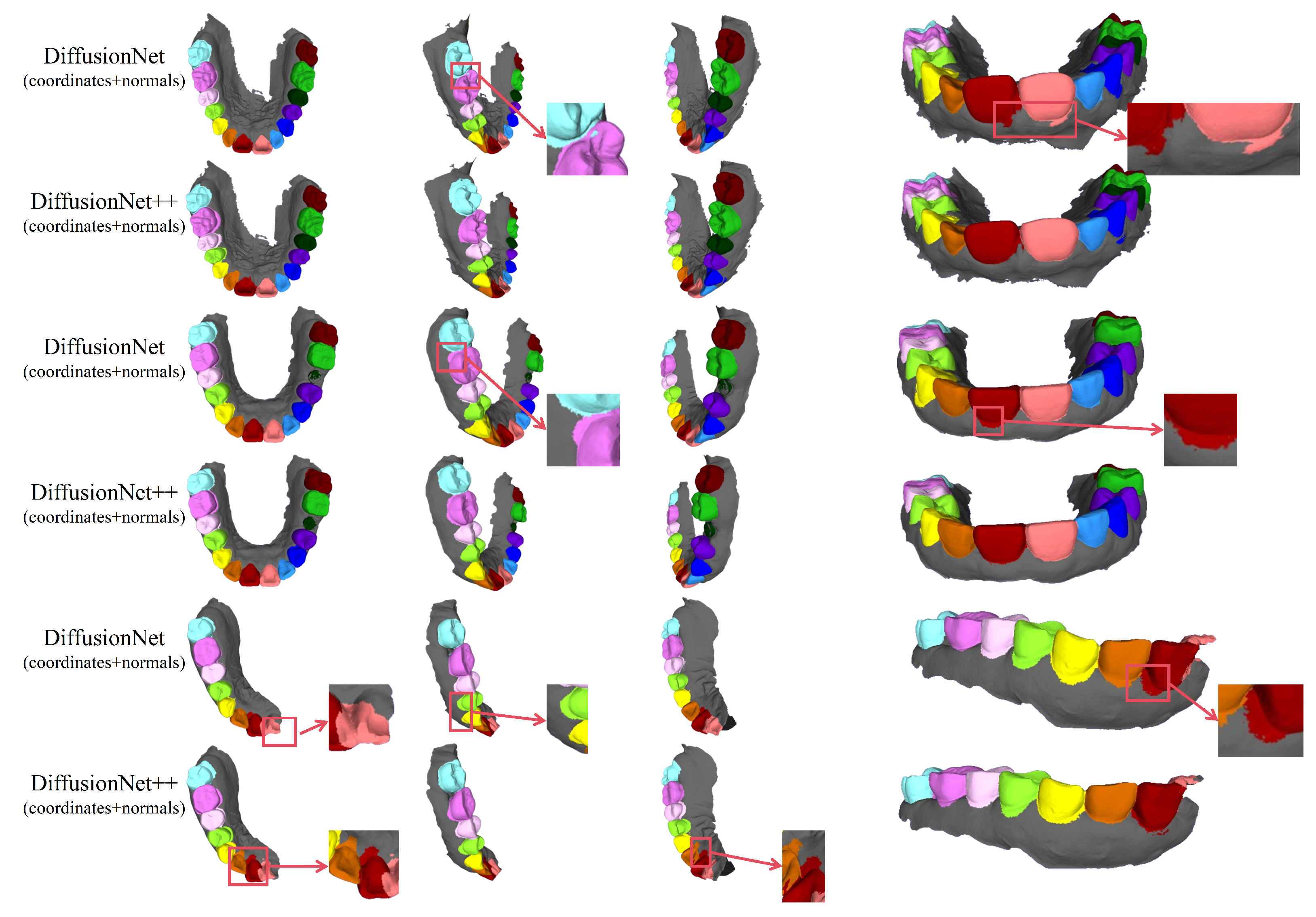

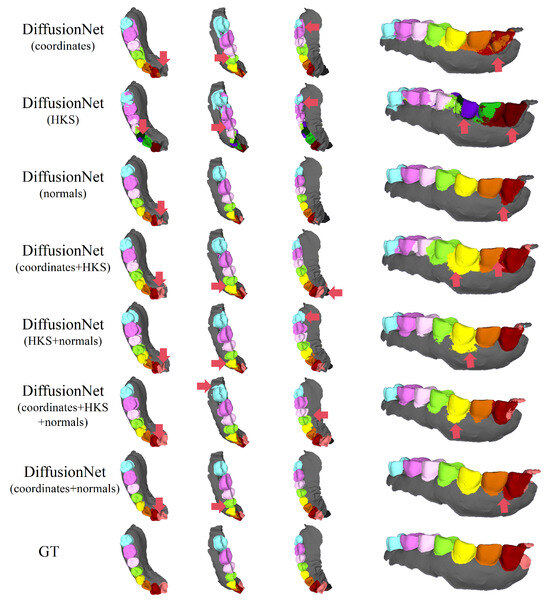

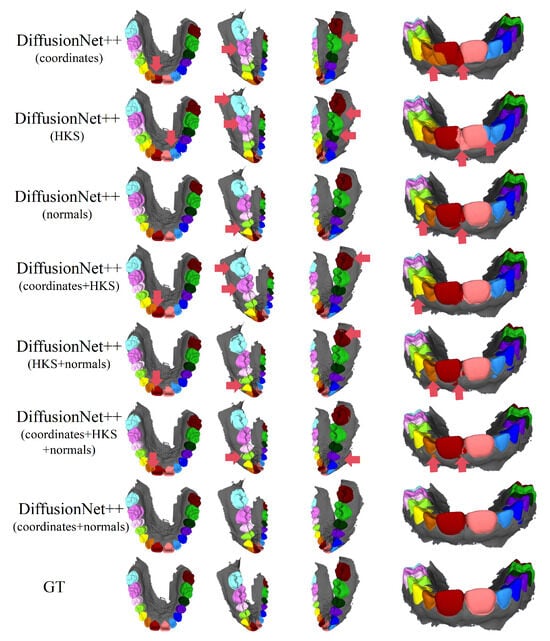

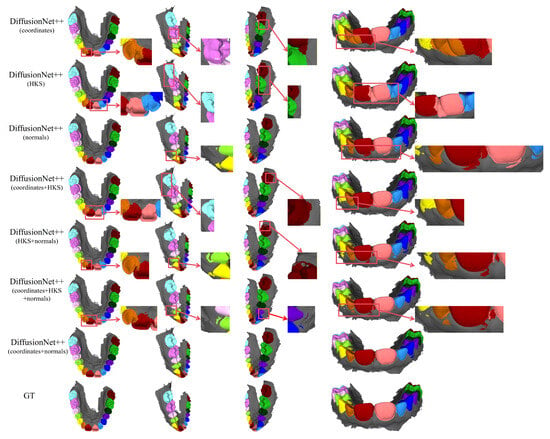

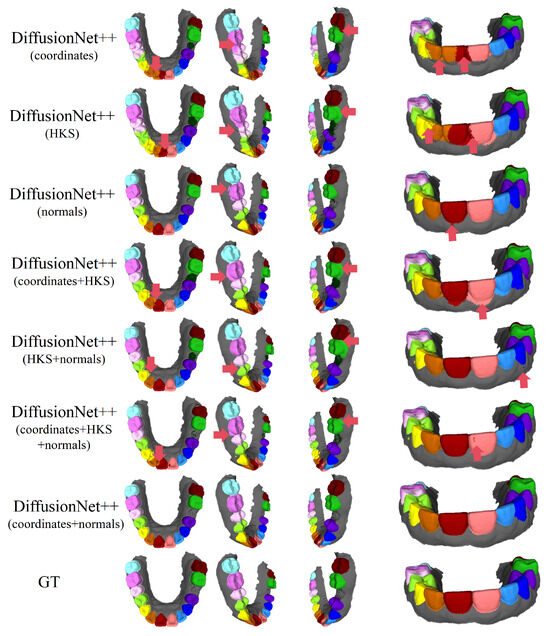

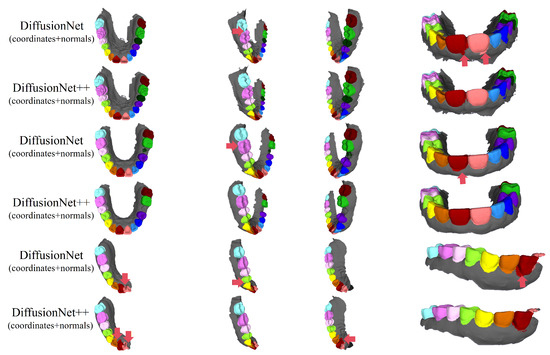

Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15 present the qualitative segmentation results of the improved model, DiffusionNet++, across different data types. Consistent with the observations made for the standard DiffusionNet, a clear reduction in missegmentation and classification errors is observed when normal vectors are incorporated into the input features. In particular, the segmentation exhibits higher precision and improved structural continuity along tooth boundaries, missing regions, and the edges of incomplete scans, indicating that the inclusion of normal features substantially enhances the model’s ability to discriminate complex local geometric structures.

Figure 10.

The qualitative experimental comparison results of DiffusionNet++. Different colors indicate different tooth categories, as defined in Figure 3. The red arrows highlight regions with segmentation errors.

Figure 11.

The qualitative comparison of DiffusionNet++ results with zoomed-in views. Different colors indicate different tooth categories, as defined in Figure 3.

Figure 12.

The qualitative experimental comparison results of DiffusionNet++ on missing teeth. Different colors indicate different tooth categories, as defined in Figure 3. The red arrows highlight regions with segmentation errors.

Figure 13.

The qualitative comparison of DiffusionNet++ results with zoomed-in views on missing teeth. Different colors indicate different tooth categories, as defined in Figure 3.

Figure 14.

The qualitative experimental comparison results of DiffusionNet++ on partially scanned data. Different colors indicate different tooth categories, as defined in Figure 3. The red arrows highlight regions with segmentation errors.

Figure 15.

The qualitative comparison of DiffusionNet++ results with zoomed-in views on partially scanned data. Different colors indicate different tooth categories, as defined in Figure 3.

Among all normal-enhanced feature configurations, the coordinates + normals combination demonstrates the most stable and reliable performance, consistently producing clear, complete, and structurally coherent segmentation results across all data types. These findings further corroborate the effectiveness of normal features in 3D dental segmentation and confirm that coordinates + normals constitute the optimal input feature configuration for DiffusionNet++.

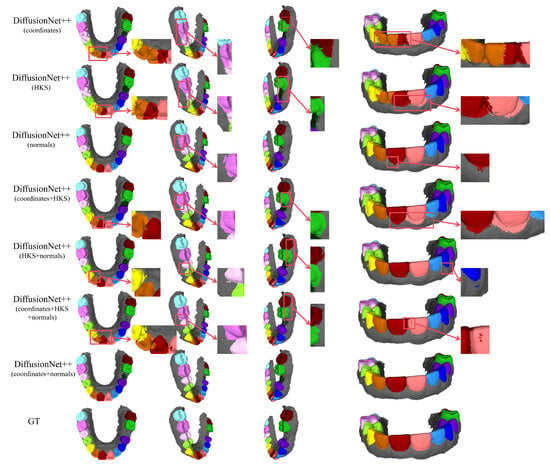

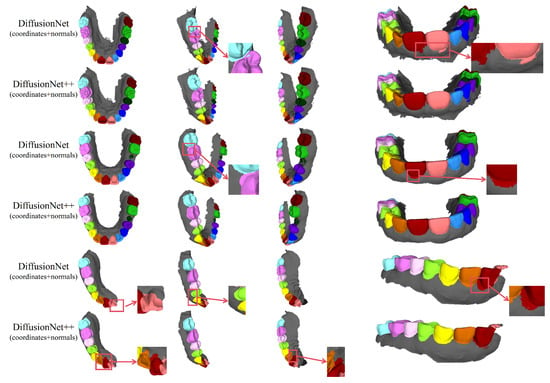

Figure 16 and Figure 17 compare the segmentation results of DiffusionNet and DiffusionNet++, which use the optimal input feature combination, across different data types. While both models achieve generally reliable segmentation, the enhanced DiffusionNet++ exhibits clear advantages in delineating boundary gaps and interdental spacing. These results confirm that the proposed architectural improvements effectively enhance segmentation accuracy and robustness, further demonstrating the superiority and practical applicability of the SE channel attention mechanism.

Figure 16.

The qualitative experimental comparison results of DiffusionNet and DiffusionNet++. Different colors indicate different tooth categories, as defined in Figure 3. The red arrows highlight regions with segmentation errors.

Figure 17.

The qualitative experimental comparison of DiffusionNet and DiffusionNet++ results with zoomed-in views. Different colors indicate different tooth categories, as defined in Figure 3.

4.3.2. Quantitative Experiments

Table 1 presents the quantitative evaluation results for DiffusionNet. Notably, when using the coordinates + normals feature combination, the model achieved the highest OA of 95.05% and mIoU of 88.58%. Among the 15 semantic classes, 11 attained their best IoU scores with this configuration, substantially outperforming all other feature combinations. For the remaining four classes, the highest IoU scores were also obtained with feature combinations that include normal vectors. These findings collectively demonstrate that the incorporation of normals consistently provides a stable and substantial performance advantage across all categories.

Table 1.

The quantitative experimental comparison results of DiffusionNet. A represents the coordinates, B represents HKS, and C represents normals. The bold numbers indicate the best performance in each row.

Table 2 and Table 3 present the quantitative evaluation results of DiffusionNet in two complex scenarios: data with missing teeth and partially scanned data, respectively. By comparing different input feature combinations, it can be found that when the model uses coordinates + normals as input features, it achieves the best overall performance in both scenarios, with OA reaching 90.11% and 89.91%, respectively, and corresponding mIoU values of 77.54% and 77.40%, which are significantly better than other feature combinations.

Table 2.

The quantitative experimental comparison results of DiffusionNet on missing teeth. A represents the coordinates, B represents HKS, and C represents normals. The bold numbers indicate the best performance in each row.

Table 3.

The quantitative experimental comparison results of DiffusionNet on partially scanned data. A represents the coordinates, B represents HKS, and C represents normals. The bold numbers indicate the best performance in each row.

From the perspective of IoU for each class, in the scenario with missing teeth, the coordinates + normals feature combination achieves the highest IoU in 14 out of 15 categories, with only class 7 obtaining the best result when using only normals as input features. In the partially scanned data scenario, the coordinates + normals feature combination performs optimally in 10 out of 15 categories, while class 6, class 9, class 13, and class 14 achieve the highest IoU when using only normal vectors as features; in addition, class 8 achieves the best performance when using the coordinates + HKS + normals feature combination. The best IoU scores for individual classes were consistently obtained with feature combinations that included normals. Overall, input configurations incorporating normals consistently and significantly outperformed those without normals across all evaluation metrics.

Table 4 presents the quantitative evaluation results of DiffusionNet++. It can be observed that when the model adopts coordinates + normals as input features, it achieves the best overall performance, with an OA of 95.87% and a mIoU of 89.80%. Among the 15 categories, 11 categories achieved the highest IoU, while class 2, class 3, class 7, and class 13 performed best when only normal input features were used. Overall, the optimal results of the model all originated from feature combinations that included normals, a trend consistent with the experimental conclusion of the standard DiffusionNet.

Table 4.

The quantitative experimental comparison results of DiffusionNet++. A represents the coordinates, B represents HKS, and C represents normals. The bold numbers indicate the best performance in each row.

Table 5 and Table 6 report the quantitative evaluation results of DiffusionNet++ under two complex conditions. When the model used coordinates + normals as input features, DiffusionNet++ achieved the best overall performance in both scenarios, with OA and mIoU reaching 91.14% and 78.66% for datasets with missing teeth, 90.75% and 79.26% for partially scanned data. These results indicate that this feature combination has good robustness and stability under different data quality conditions.

Table 5.

The quantitative experimental comparison results of DiffusionNet++ on missing teeth. A represents the coordinates, B represents HKS, and C represents normals. The bold numbers indicate the best performance in each row.

Table 6.

The quantitative experimental comparison results of DiffusionNet++ on partially scanned data. A represents the coordinates, B represents HKS, and C represents normals. The bold numbers indicate the best performance in each row.

From the perspective of IoU for each class, in the scenario with missing teeth, the coordinates + normals feature combination achieved the highest IoU in 11 out of 15 categories, while class 6, class 7, class 11, and class 12 performed best when only normals were used as input features.

Under the condition of partially scanned data, the coordinates + normals combination performed optimally in 8 out of 15 categories; class 1, class 3, class 4, class 5, class 10, and class 13 achieved the highest IoU when only normals were used as input features; and class 8 achieved the best result when using the HKS + normals feature combination.

Summarizing the experimental results from Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6, it can be concluded that DiffusionNet++ achieved the best overall performance when using coordinates + normals as input features under different data types and complex scenarios. Moreover, any input feature combination that includes normals consistently outperforms those that do not. This pattern is highly consistent with the trend presented by DiffusionNet under the same experimental settings, further verifying the crucial role of normal vector features in the task of 3D tooth mesh segmentation.

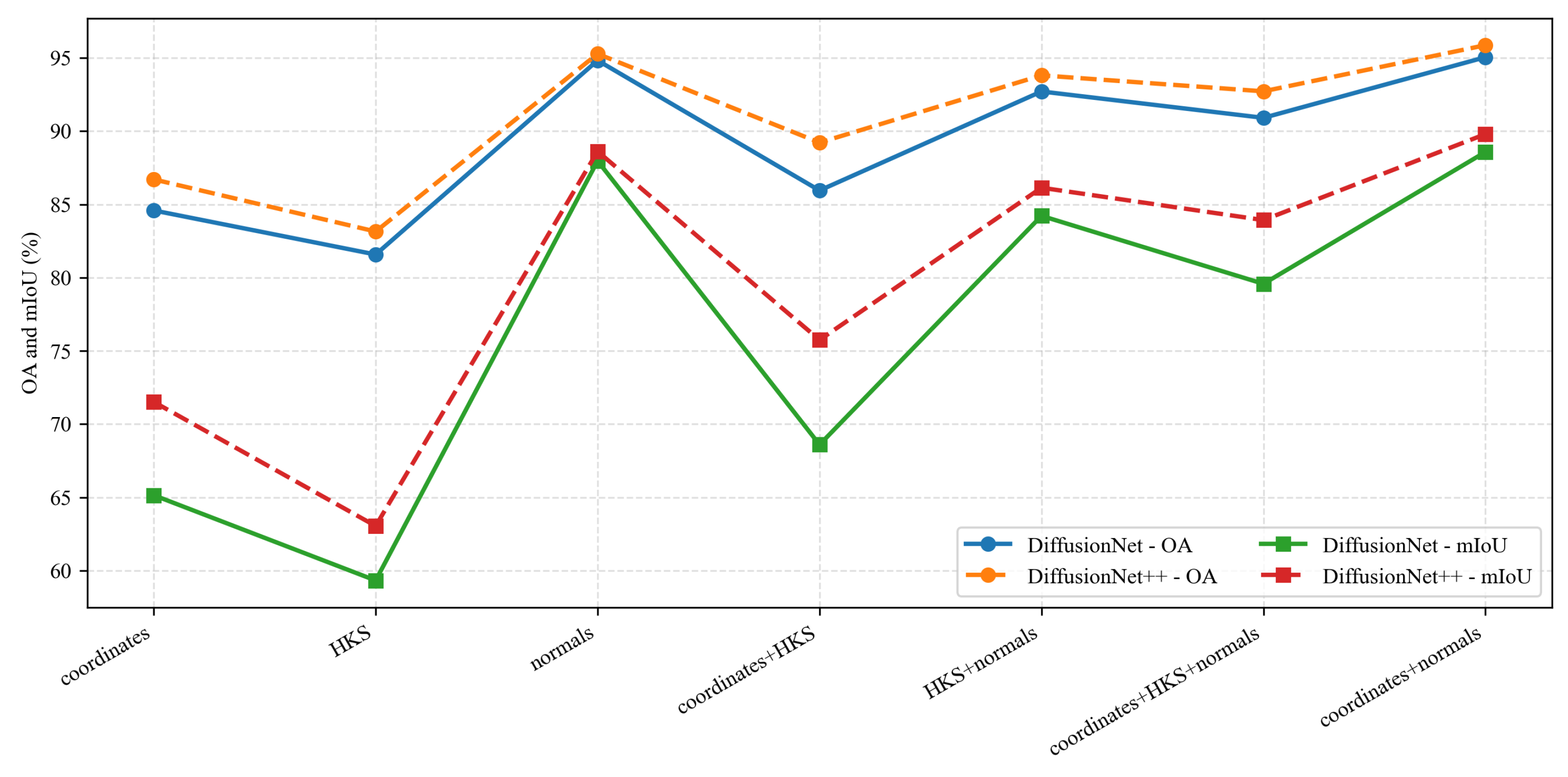

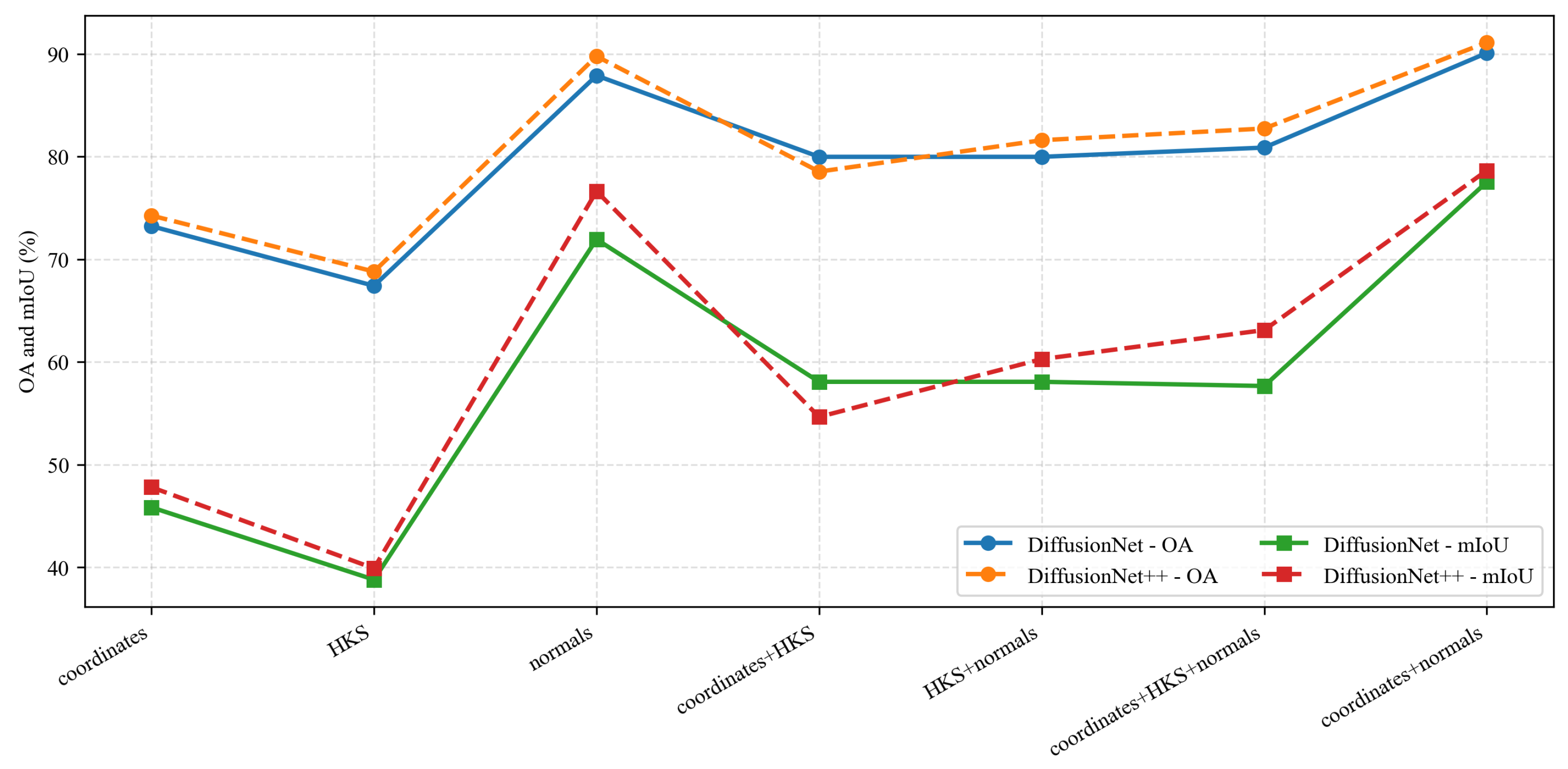

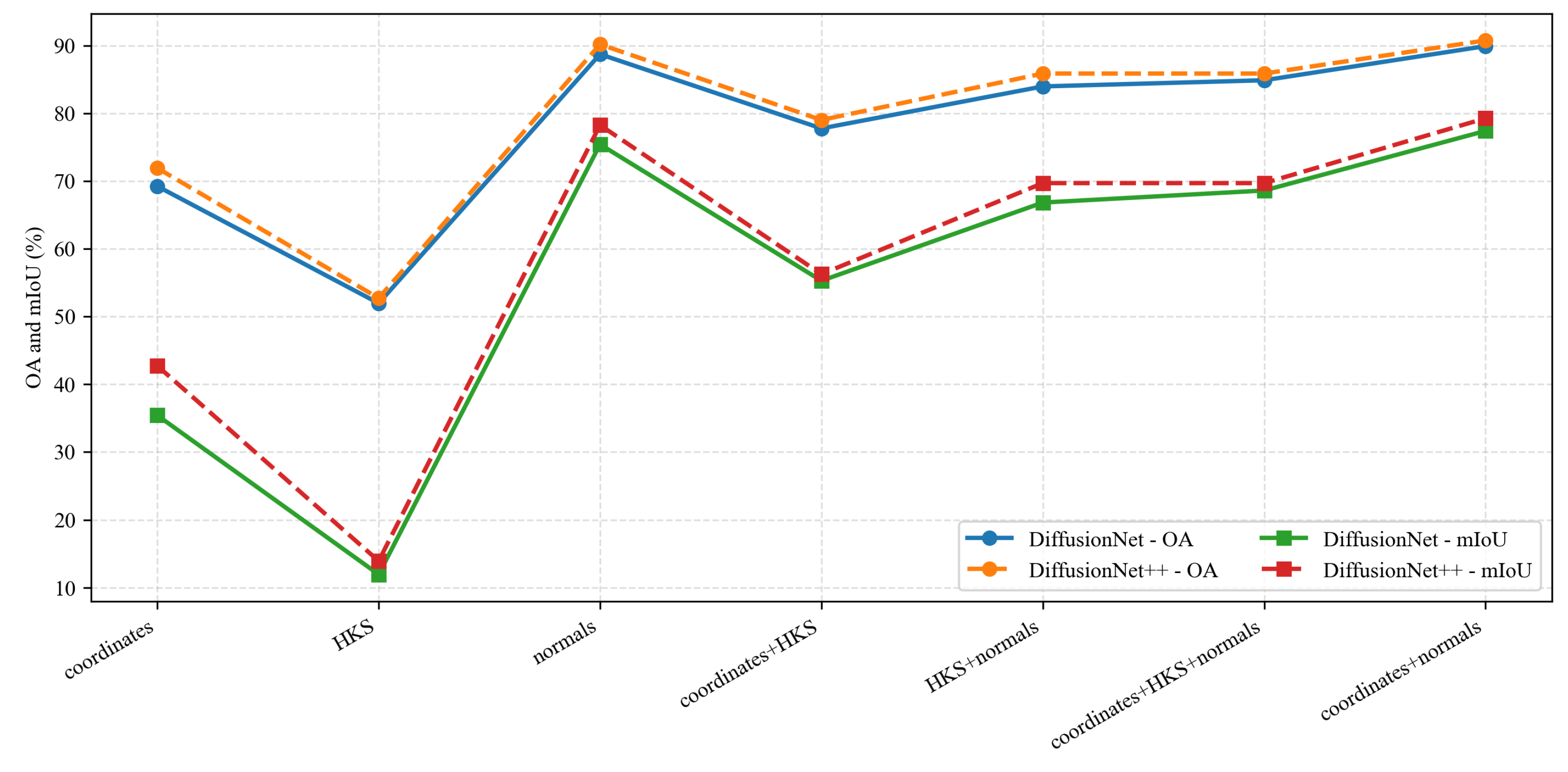

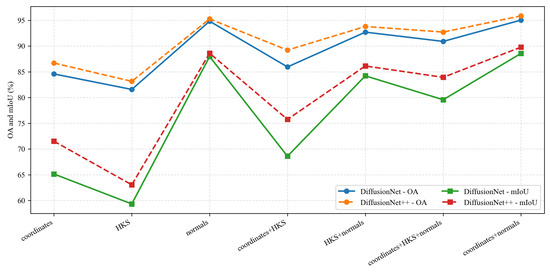

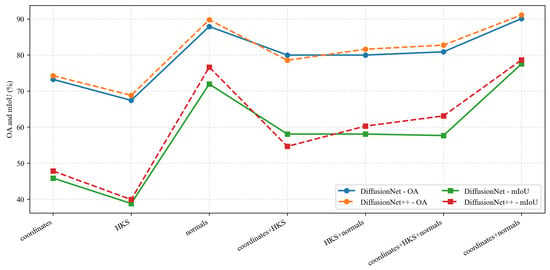

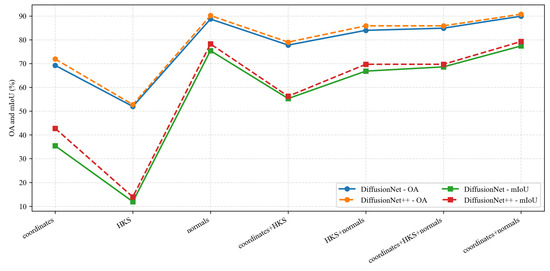

Under identical data types and input feature configurations, we conducted a systematic comparison between DiffusionNet and DiffusionNet++, as illustrated in the Figure 18, Figure 19 and Figure 20. When using coordinates + normals as the input feature combination, both models consistently outperform other feature settings, indicating that normal vectors provide a clear advantage in capturing local dental geometric structures. Moreover, under the same input features, DiffusionNet++ achieves consistently superior overall performance compared with the original DiffusionNet, exhibiting stable improvements in both OA and mIoU. These results further demonstrate that the architectural enhancements introduced in DiffusionNet++ substantially strengthen feature representation and global modeling capability, thereby effectively improving both the accuracy and robustness of 3D dental segmentation.

Figure 18.

The quantitative experimental comparison results of DiffusionNet and DiffusionNet++.

Figure 19.

The quantitative experimental comparison results of DiffusionNet and DiffusionNet++ on missing teeth.

Figure 20.

The quantitative experimental comparison results of DiffusionNet and DiffusionNet++ on partially scanned data.

5. Discussion

In this study, the model was evaluated on a dataset of 280 3D intraoral scans, which was partitioned into training and testing sets at an 8:2 ratio. The dataset includes a range of clinically relevant irregular scenarios, such as scans with missing teeth and partially scanned data, providing a rigorous benchmark for assessing the model’s robustness and generalization across varying data quality and completeness.

Compared with the standard DiffusionNet, the proposed DiffusionNet++ introduces systematic enhancements in both input feature design and feature modeling strategy. First, normal vectors are incorporated at the input stage to strengthen the model’s sensitivity to local geometric structure. Normal vectors explicitly encode surface orientation and curvature variations, serving as critical descriptors for capturing fine-grained geometric differences on tooth surfaces and playing a pivotal role in improving the accuracy of 3D dental segmentation. Second, a SE channel-attention mechanism is integrated into the network architecture, enabling adaptive recalibration of channel-wise feature responses. By emphasizing more discriminative feature representations, this mechanism further enhances feature expressiveness and leads to consistent improvements in segmentation performance.

Experimental results demonstrate that the model achieves an OA of 95.87% and a mIoU of 89.80% across the full dataset. Specifically, for scans with missing teeth, the OA reaches 91.14% with an mIoU of 78.66%; for partially scanned data, OA is 90.75% with an mIoU of 79.26%. Despite substantial variations in data quality, the model consistently maintains high segmentation performance, highlighting its robustness and generalizability. Furthermore, the results demonstrate that the coordinates + normals feature combination yields the best performance for the task of 3D tooth segmentation, providing an effective feature representation that achieves an excellent balance between computational efficiency and segmentation accuracy.

6. Conclusions

This study introduces DiffusionNet++, a segmentation framework capable of directly operating on high-resolution 3D intraoral scans. Existing 3D dental segmentation methods typically rely on downsampling to reduce computational costs, which inevitably leads to the loss of critical geometric details. In contrast, the proposed approach operates data at its native resolution, effectively preserving essential geometric information and enabling more accurate and robust representations of local structures.

We further enhance the DiffusionNet architecture by incorporating direction-sensitive normal vector features and a SE channel attention mechanism. Systematic experiments validate the effectiveness of both the normal vector features and the channel attention mechanism, demonstrating that the coordinates + normals combination is the most suitable feature set for high-resolution 3D dental segmentation. Moreover, evaluations across diverse data types confirm the robustness and generalizability of the proposed model.

In summary, this work represents a notable advancement in high-resolution 3D dental segmentation, addressing a critical gap in handling real-world, high-fidelity data and overcoming the limitations of conventional approaches that depend on resolution downsampling. Beyond dental applications, the DiffusionNet++ framework exhibits strong transferability, offering a promising solution for segmentation of other large-scale, high-resolution 3D datasets—an avenue that will guide our future research efforts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.Z., C.W. and S.W.; methodology, K.Z.; software, K.Z.; validation, K.Z.; formal analysis, K.Z., C.W. and S.W.; investigation, K.Z.; resources, K.Z. and C.W; data curation, K.Z., C.W. and S.W.; writing—original draft preparation, K.Z.; writing—review and editing, K.Z. and C.W.; visualization, K.Z.; supervision, C.W.; project administration, C.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in https://github.com/littlezhang231/Data (accessed on 20 January 2026).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lloyd, D.F.A.; Pushparajah, K.; Simpson, J.M.; Van Amerom, J.F.P.; Van Poppel, M.P.M.; Schulz, A.; Kainz, B.; Deprez, M.; Lohezic, M.; Allsop, J.; et al. Three-dimensional visualisation of the fetal heart using prenatal MRI with motion-corrected slice-volume registration: A prospective, single-centre cohort study. Lancet 2019, 393, 1619–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Wu, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Gong, D.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Q.; Huang, S.; Yang, M.; Yang, X.; et al. Deep learning-based model for detecting 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia on high-resolution computed tomography. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhtiarnia, A.; Zhang, Q.; Iosifidis, A. Efficient high-resolution deep learning: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, N.; Attaiki, S.; Crane, K.; Ovsjanikov, M. DiffusionNet: Discretization agnostic learning on surfaces. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2022, 41, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maturana, D.; Scherer, S. VoxNet: A 3D convolutional neural network for real-time object recognition. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Hamburg, Germany, 28 September–2 October 2015; pp. 922–928. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Bai, X.; Shang, J.; Zhang, R.; Dong, J.; Wang, X.; Sun, G.; Fu, H.; Tai, C.-L. VMNet: Voxel-Mesh Network for Geodesic-Aware 3D Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 15468–15478. [Google Scholar]

- Su, H.; Maji, S.; Kalogerakis, E.; Learned-Miller, E. Multi-view convolutional neural networks for 3D shape recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 945–953. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Ji, R.; Gao, Y. GV-CNN: Group-view convolutional neural networks for 3D shape recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kundu, A.; Yin, X.; Fathi, A.; Ross, D.; Brewington, B.; Funkhouser, T.; Pantofaru, C. Virtual multi-view fusion for 3D semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 518–535. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, C.R.; Su, H.; Mo, K.; Guibas, L.J. PointNet: Deep learning on point sets for 3D classification and segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 652–660. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, C.R.; Yi, L.; Su, H.; Guibas, L.J. PointNet++: Deep hierarchical feature learning on point sets in a metric space. In Proceedings of the NIPS’17: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, T.; Xiao, J.; Yan, F.; Jiang, H. Context-aware 3D point cloud semantic segmentation with plane guidance. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2022, 25, 6653–6664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Feng, Y.; You, H.; Zhao, X.; Gao, Y. MeshNet: Mesh neural network for 3D shape representation. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 January–1 February 2019; pp. 8279–8286. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.V.; Sheshappanavar, S.V.; Kambhamettu, C. MeshNet++: A Network with a Face. In Proceedings of the ACM Multimedia, Virtual, 20–24 October 2021; pp. 4883–4891. [Google Scholar]

- Lahav, A.; Tal, A. MeshWalker: Deep mesh understanding by random walks. ACM Trans. Graph. 2020, 39, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanocka, R.; Hertz, A.; Fish, N.; Giryes, R.; Fleishman, S.; Cohen-Or, D. MeshCNN: A network with an edge. ACM Trans. Graph. (ToG) 2019, 38, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinelli, G.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Malcangi, G.; Limongelli, L.; Montenegro, V.; Coloccia, G.; Laudadio, C.; Patano, A.; Inchingolo, F.; et al. White spot lesions in orthodontics: Prevention and treatment. A descriptive review. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2021, 35, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Li, C.; Wang, W. ToothNet: Automatic tooth instance segmentation and identification from cone beam CT images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 6368–6377. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, J.S.; Cho, Y.-R. Weighted Sparse Convolution and Transformer Feature Aggregation Networks for 3D Dental Segmentation. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 135172–135184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Song, Q.; Gao, L.; Lai, Y.-K. Automatic 3D tooth segmentation using convolutional neural networks in harmonic parameter space. Graph. Model. 2020, 109, 101071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Guo, Y.; Sun, D.; Pei, Y.; Xu, T. Automatic tooth segmentation and 3D reconstruction from panoramic and lateral radiographs. In Proceedings of the Pattern Recognition and Computer Vision: Third Chinese Conference, PRCV 2020, Nanjing, China, 16–18 October 2020; pp. 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Rekik, A.; Ben-Hamadou, A.; Smaoui, O.; Bouzguenda, F.; Pujades, S.; Boyer, E. TSegLab: Multi-stage 3D dental scan segmentation and labeling. Comput. Biol. Med. 2025, 185, 109535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Cho, Y.; Kim, D.; Chang, M.; Kim, Y.-J. Tooth segmentation of 3D scan data using generative adversarial networks. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, T.J.; Kim, K.C.; Cho, H.C.; Seo, J.K. A fully automated method for 3D individual tooth identification and segmentation in dental CBCT. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 44, 6562–6568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, J.; Kim, J.-Y.; Yu, H.-S.; Lee, K.-J.; Choi, S.-H.; Kim, J.-H.; Ahn, H.-K.; Cha, J.-Y. Accuracy and efficiency of automatic tooth segmentation in digital dental models using deep learning. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanjani, F.G.; Moin, D.A.; Claessen, F.; Cherici, T.; Parinussa, S.; Pourtaherian, A.; Zinger, S.; de With, P.H.N. Mask-MCNet: Instance Segmentation in 3D Point Cloud of Intra-oral Scans. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2019; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 128–136. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Z.; Li, C.; Chen, N.; Wei, G.; Chen, R.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, D.; Wang, W. TSegNet: An efficient and accurate tooth segmentation network on 3D dental model. Med. Image Anal. 2021, 69, 101949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Ye, C.; Chen, P.; Liu, Y.; Han, X.; Cui, S. Darch: Dental arch prior-assisted 3D tooth instance segmentation with weak annotations. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 20752–20761. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, C.; Wang, L.; Wu, T.-H.; Wang, F.; Yap, P.-T.; Ko, C.-C.; Shen, D. Deep multi-scale mesh feature learning for automated labeling of raw dental surfaces from 3D intraoral scanners. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2020, 39, 2440–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.-H.; Lian, C.; Lee, S.; Pastewait, M.; Piers, C.; Liu, J.; Wang, F.; Wang, L.; Chiu, C.-Y.; Wang, W.; et al. Two-stage mesh deep learning for automated tooth segmentation and landmark localization on 3D intraoral scans. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2022, 41, 3158–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Meng, D.; Cui, Z.; Gao, C.; Gao, X.; Lian, C.; Shen, D. Two-stream graph convolutional network for intra-oral scanner image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2021, 41, 826–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Gao, C.; Liu, F.; Meng, D.; Yan, Y. THISNet: Tooth Instance Segmentation on 3D Dental Models via Highlighting Tooth Regions. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 34, 5229–5241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Chen, B.; Shen, Y.; Shen, K. TeethGNN: Semantic 3D Teeth Segmentation With Graph Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2023, 29, 3158–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenmayr, L.; von Schwerin, R.; Schaudt, D.; Riedel, P.; Hafner, A. DilatedToothSegNet: Tooth Segmentation Network on 3D Dental Meshes Through Increasing Receptive Vision. J. Imaging Inform. Med. 2024, 37, 1846–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwood, J.; Towsley, D. Diffusion-convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the NIPS’16: Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Barcelona, Spain, 5–10 December 2016; Volume 29. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.-T.; Ahmad, N.; Khursheed, A. Enhancing 3D U-Net with Residual and Squeeze-and-Excitation Attention Mechanisms for Improved Brain Tumor Segmentation in Multimodal MRI. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2025, 144, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glorot, X.; Bordes, A.; Bengio, Y. Deep Sparse Rectifier Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Fourteenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS 2011); JMLR Workshop and Conference Proceedings: Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 2011; pp. 315–323. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Hamadou, A.; Smaoui, O.; Chaabouni-Chouayakh, H.; Rekik, A.; Pujades, S.; Boyer, E.; Strippoli, J.; Thollot, A.; Setbon, H.; Trosset, C.; et al. Teeth3ds: A benchmark for teeth segmentation and labeling from intra-oral 3D scans. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.06094. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.