Abstract

Edible mushrooms (Suillus luteus) represent valuable sources of nutrients and bioactive compounds that are sensitive to drying conditions. The objective of this study was to determine the drying time, kinetic model, effective diffusivity, activation energy, and color changes in S. luteus samples subjected to convective and vacuum drying at 70 and 50 °C, respectively, following pretreatments with 1% citric acid or blahing. The shortest drying time to reach equilibrium moisture was 14 h at 70 °C under a vacuum, whereas the longest was 44 h at 50 °C under convective drying. The Midilli, logarithmic, and Henderson and Pabis models provided the best fits for vacuum drying. The effective moisture diffusivity values ranged from 5.83 × 10−9 m2s−1 at 50 °C to 1.159 × 10−8 m2s−1 at 70 °C, while the mean activation energies for vacuum and convective drying were 10.27 kJmol−1 and 24.7 kJmol−1, respectively. The highest rehydration capacity was observed in untreated samples dried under a vacuum, with a value of 3.5 g H2O/g dry matter, whereas convective drying yielded 2.4 g H2O/g dry matter. The greatest shrinkage with respect to thickness was observed in those treated with citric acid and blanching. Correlation analysis of color revealed a strong negative relationship between lightness (L*) and total color difference (ΔE), as well as high positive correlations among a*, b*, and C*, suggesting that color transformations occur jointly throughout dehydration. The findings indicate that effective diffusivity increased with temperature, untreated samples exhibited greater water loss, and rehydration ratios were higher in untreated compared with pretreated samples.

1. Introduction

Edible mushrooms are recognized as functional foods due to their high concentrations of nutraceutical components and bioactive compounds. They are characterized by high protein content, low fat and energy values, and substantial levels of minerals such as iron and phosphorus, as well as vitamins including riboflavin, thiamine, ergosterol, niacin, and ascorbic acid. In addition, mushrooms contain bioactive compounds, including secondary metabolites and polysaccharides [1,2,3,4]. Several studies have shown that these biologically active compounds possess a range of pharmacological properties, including antitumor, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antioxidant, hepatoprotective, antiviral, immunomodulatory, hypocholesterolemic, and antibacterial effects [4,5,6].

Due to their high moisture content, mushrooms are highly perishable and begin to deteriorate shortly after harvest, with a typical shelf life of 1–3 days at room temperature [7]. Drying represents an efficient method for prolonging the shelf life of mushrooms by reducing their moisture content [8]. It also enhances the physicochemical and microbiological stability of the product [9]. However, processing parameters such as temperature, time, and air velocity must be considered to minimize the impact on product quality [10].

High-temperature drying can lead to the degradation of polysaccharides and proteins, increasing the concentration of saturated fatty acids due to oxidation, hydrolysis, and the Maillard reaction [8]. The application of chemical pretreatments prior to drying can mitigate these effects. Dried mushrooms have a distinctive flavor and are commonly employed in various food formulations such as soups and salads [11].

During the drying process, two simultaneous water transport mechanisms occur: diffusion, which transfers moisture from the interior of the solid product to its surface, and convection, whereby moisture is removed from the surface by a carrier gas (or, under vacuum application in non-convective dryers, vapor removal to the surrounding medium occurs as a result of the low partial vapor pressure in the chamber generated by the vacuum) [12]. In most dehydration processes, water removal occurs via convective evaporation [13,14], involving simultaneous heat, mass, and momentum transfer [15], and in porous material such as mushroom, water can also be transported by pressure-driven capillary flow and the heat [16].

The design and optimization of drying systems are based on mathematical modeling to describe the physical phenomena as accurately as possible [17,18]. Among the most widely used drying kinetics models in the literature are the Fick, Newton, Page, Modified Page, Modified Page, Modified Henderson and Pabis, Wang and Singh, Peleg, and logarithmic models [19,20,21,22]. These models are classified as theoretical, semi-theoretical, or empirical and have been extensively validated across various food matrices [13,19,23,24].

Dehydration also induces significant changes in the optical and chromatic properties of food, with color being a critical determinant of consumer acceptance [25]. Thus, the assessment of color parameters (L*, a*, b*, C*, h°, and ΔE) and the analysis of their statistical correlations allow the evaluation of the effects of drying conditions and pretreatments on product appearance [26]. Analytical tools such as radar charts and chromatic correlation matrices offer a detailed interpretation of the interactions among color variables and their relationship to product quality.

Considering the growing demand for natural ingredients and healthier foods, the preservation of edible mushrooms through optimized drying techniques has gained importance to add value and promote consumption diversity. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to evaluate the influence of drying temperature, drying method, and pretreatment of the edible mushroom Suillus luteus to extend its shelf life, as well as to establish the drying parameters, kinetic models, and color variation profiles of the dehydrated mushrooms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

Mushrooms of the species Suillus luteus were used as the raw material. The specimens were collected in June 2023 from pine (Pinus radiata) forests located in Soccllaccasa, Abancay-Apurímac (Peru), at an altitude of 3759 m a.s.l. A total of 20 kg of fresh, healthy mushrooms was harvested, selecting only those with firm caps and yellowish spongy bases and free from dark spots or soft texture. High-quality samples of relatively uniform size (cap diameter 4–8 cm, cylindrical sipe 2–3 cm long and 1–2 cm in diameter) were chosen.

Prior to drying, the mushrooms were washed under running water, separated from their stems, and cut vertically into four slices with a thickness of 0.4 cm. A portion of the samples was immersed in hot water at 87 °C (blanching) for 1 min, another portion was immersed in a 1% (w/c) citric acid solution for 15 min at 20 °C, and a third portion was left untreated. These procedures followed the methodology described by Maray et al. [27], with some modifications. The ratio of immersion liquid to mushroom mass was maintained at 5:1, as reported by Hassan and Medany [28], also with some modifications. Immersion-based pretreatments aimed at preventing the browning inherently involved in contact with water, whereas the control samples did not undergo any immersion step. As a result, these differences in processing led to variations in the initial moisture content.

2.2. Drying Equipment

The experimental work was conducted in the Laboratory of Agroindustrial Product Processing and the General Chemistry Laboratory of the Professional Academic School of Agroindustrial Engineering at the National University Micaela Bastidas of Apurímac, located at an altitude of 2700 m a.s.l. Drying was carried out using two different methods: (i) convective drying in a Memmert oven, model 30-750 (Baviera, Germany), equipped with mechanical ventilation (0 ms−1) and (ii) vacuum drying in a Memmert oven, model VO49 (Baviera, Germany), operating at an air pressure of 50 mbar. For each drying temperature, two pretreatments were evaluated: blanching at boiling water for 1 min and immersion in a 1% (w/c) citric acid solution, as well as control samples without pretreatment. The experimental design is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Coding of treatments for drying Suillus luteus mushrooms under different temperatures and pretreatments.

2.3. Experimental Drying Process

The sliced mushroom samples were subjected to drying treatments, during which the mass variation was recorded at predetermined temperature and time conditions at intervals of 60 and 120 min using an analytical balance (Sartorius ENTRIS 224-1S, Goettingen, Germany). The drying process was considered complete when the sample mass remained constant between two measurements. The dried samples were subsequently cooled and packaged in low-density polyethylene bags. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

For the analysis of drying kinetics, the moisture content was expressed on a dry basis, defined as the ratio between the mass of water and the mass of dry solids, as shown in Equation (1) [17,29].

where is dry basis moisture and is wet basis moisture

The moisture content in the drying was obtained by plotting the moisture content against the drying time [14,30].

The effective moisture diffusivity () was estimated using the theoretical diffusion model based on Fick’s second law (Equation (2)). The analytical solution for a flat plate (Equation (3)) was used to fit the experimental drying curves. In the model, the first 200 terms of the series were considered for the estimation of The analysis was conducted under the assumptions that (i) internal resistance to mass transfer predominates over external resistance and (ii) the average of the initial and final thickness of the samples during drying is considered.

where MR is the moisture ratio, X(t) is the moisture content at time t (kg H2O/kg dry matter), X0 is the initial moisture content (kg H2O/kg dry matter), Xe is the equilibrium moisture content (kg H2O/kg dry matter), L is the half-thickness of the sample (m), and n is the number of terms in the series.

The experimental data were further correlated using other theoretical and semi-theoretical kinetic models, including those proposed by Henderson and Pabis, Midilli, Logarithmic, Page, and Lewis, which have demonstrated superior fitting performance, as reported in previous studies (Table 2).

Table 2.

Kinetic drying models analyzed to correlate the experimental drying data of Suillus luteus mushrooms.

It is well established that temperature has a significant influence on the diffusion coefficient, an effect that can be described by the Arrhenius relationship (Equation (4)) [13,35].

whereis the equivalent diffusivity constant (m2s−1), Ea is the activation energy (kJmol−1), is the universal gas constant (8.314 Jmol−1K−1), and is the absolute temperature (K).

2.4. Rehydration Experiments

To determine the initial moisture content, the gravimetric method by oven drying was used, following the AOAC 930.04 (1995) [36] standard. The rehydration capacity was determined following AACC Method 88-04 [37], with certain modifications. The procedure consisted of immersing the dried samples in a beaker containing 80 mL of distilled water maintained at 20 °C. After predetermined time intervals, the samples were removed, dried with absorbent paper, and subsequently weighed. Measurements were recorded every 20 min until a constant weight (two measurements had the same weight) was achieved, using a sample-to-water ratio of 1:15. The total duration of the rehydration trials was 140 min. Rehydrated samples were weighed using a Sartorius analytical balance (model ENTRIS 224-1S). The rehydration capacity of the Suillus luteus mushrooms was expressed as the ratio between the mass of absorbed water (g) and the mass of the dry sample (g) (Equation (5))

where RR is the rehydration ratio, Wr is the weight of the rehydrated matter (kg), and Wd is the weight of the dry matter (kg).

The rehydration curve model was based on Fick’s equation (Equation (6))

2.5. Dimensional Shrinkage Experiments

To calculate the shrinkage of mushrooms during drying, it is important to understand how the process affects their structure. Shrinkage is calculated (by measuring the change in diameter or height) primarily by comparing the dimensions after drying. This is the simplest and most practical method: measure how the mushroom shrinks in a specific direction (length, width, or height). This involves selecting representative samples in slices or with uniform shapes. Measure the initial thickness (ei) with calipers. Dry the mushroom, following your drying process. Measure the final thickness (ef) after one round of drying. Allow the mushroom to cool to room temperature and measure again [38,39].

The percentage of dimensional shrinkage () for a given dimension is calculated as follows (Equation (7)):

where ei is the initial thickness and ef is the final thickness.

2.6. Color of Suillus luteus

The dried samples were ground and sieved (80 mesh). Color was measured with a calibrated colorimeter (PCE-CSM7). The parameters L*, a*, and b* were recorded, and from them, C*, h°, and ΔE were calculated following Mathias-Rettig and Ah-Hen [40]. Results were summarized in a correlation matrix, generated in Python (v. 3.13.4).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The experiments were conducted using a completely randomized factorial design (CRD) and three replicates. The factors evaluated included the dryer type (convective oven and vacuum oven), pretreatment method (blanching, citric acid, and control), and drying temperature (50 °C and 70 °C).

Data processing and statistical analysis were performed using R software (version 4.1.3). Experimental results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three replicates. Statistical significance was determined at p < 0.05. The experimental data were evaluated using the coefficient of determination (R2) and the reduced chi-square (χ2), with the root mean square error (RMSE) applied where ambiguity arose [41]. For modeling, Xlstat 2018.5 software was used.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Drying Rate

The moisture content of fresh mushrooms exhibits variability, depending on the species and collection site. In the present study, Suillus luteus samples, both fresh and subjected to various pretreatments, demonstrated moisture contents of approximately 85% wet basic moisture (ranging from 84.51% in T3 and 93.87% in T5), which is lower than the 94.63%, 94.8%, and 95.92% reported by Jacinto-Azevedo et al. [42] and Espinoza-Ticona et al. [43] for Suillus luteus mushrooms. However, pretreatments were found to increase the moisture content, with citric acid-treated samples showing the highest values. This increase may be attributed to alterations in the cellular structure and wall integrity, enhancing permeability and water retention [44]. Specifically, blanched mushrooms had an initial moisture content (wet basis) of 89.94 ± 0.91%, citric acid-treated mushrooms 92.13 ± 1.28%, and untreated samples 85.13 ± 1.24%.

The initial free moisture content for blanched samples was 8.5 kg water/kg dm, 10.4 kg water/kg dm for citric acid-treated samples, and 6.0 kg water/kg dm for the control, with the final free moisture values ranging from 0.01 a 0.02 kg water/kg dm at the end of the drying process.

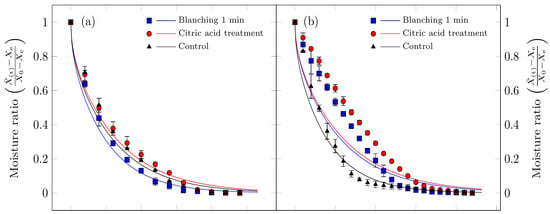

Dry-basis moisture content was calculated according to Equation (2). The results, presented in Figure 1, indicate that the citric acid-treated samples exhibited the highest initial free moisture, reflecting the effect of pretreatment on increasing water retention.

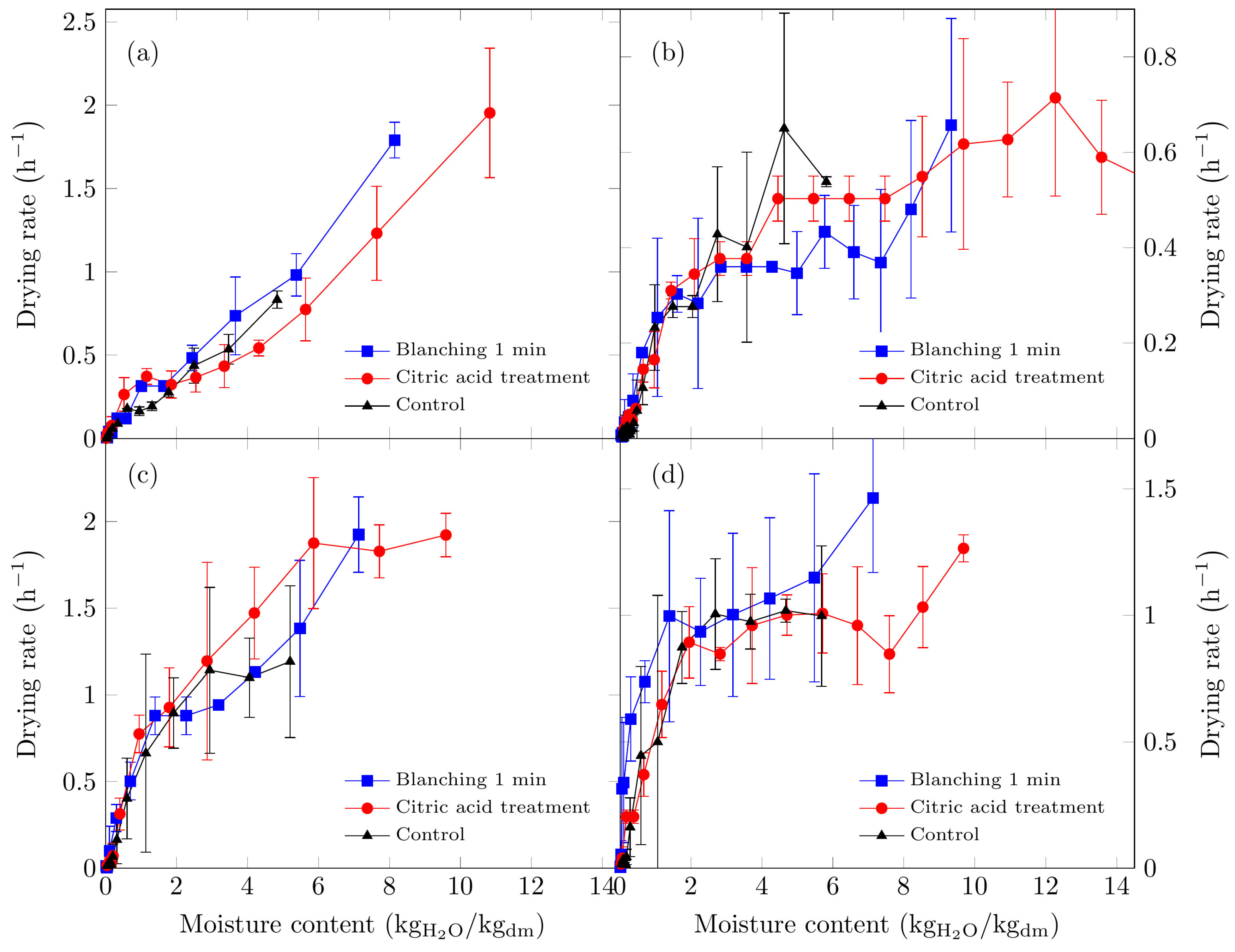

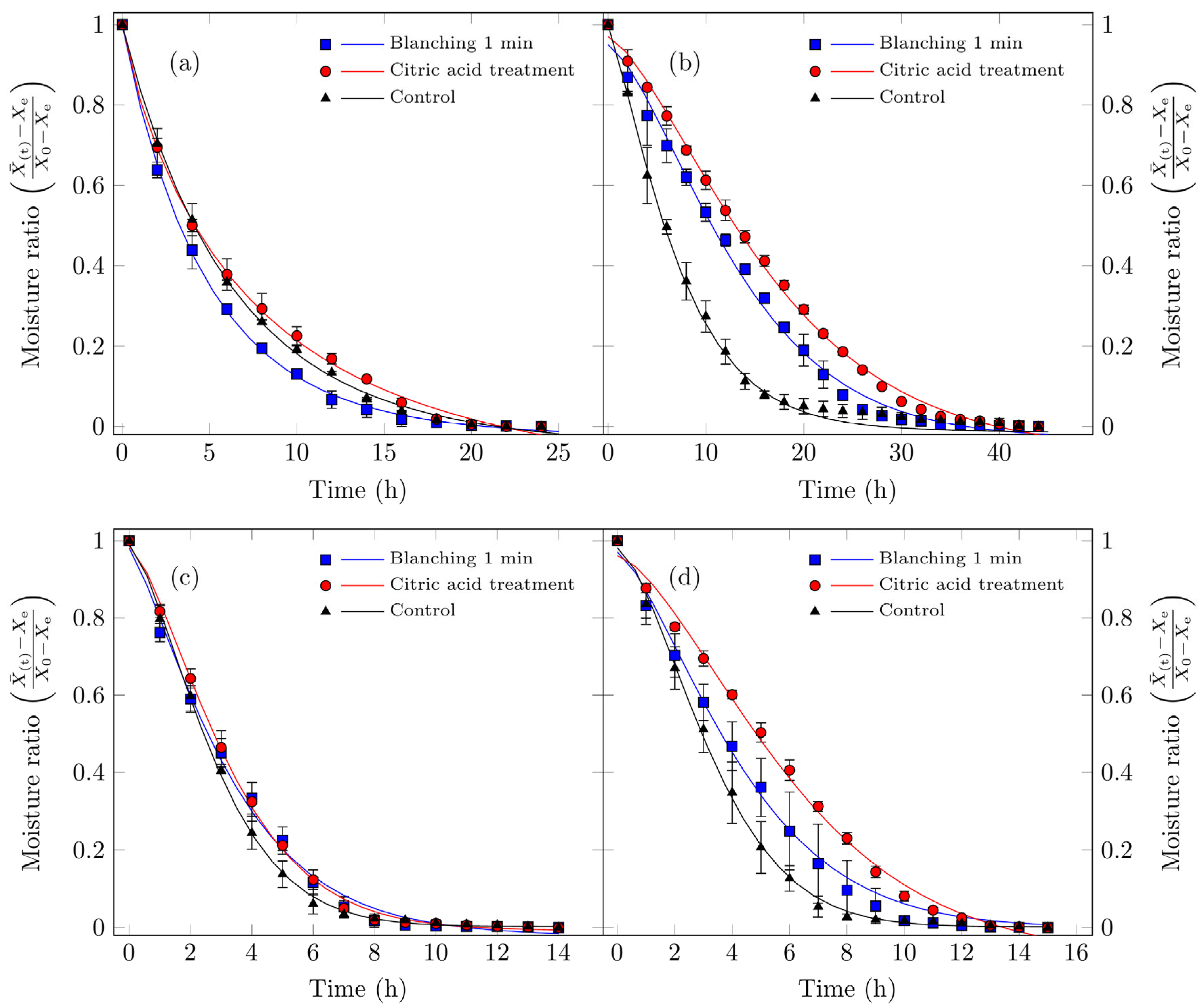

Figure 1.

Drying rate curves of Suillus luteus mushrooms under the following conditions: (a) vacuum oven drying at 50 °C, (b) convective oven drying at 50 °C, (c) vacuum oven drying at 70 °C, and (d) convective oven drying at 70 °C.

Higher drying rates were recorded using the vacuum oven (Figure 1a,c). At 50 °C under vacuum conditions, only the falling-rate period was observed, suggesting that moisture transport was predominantly via capillary diffusion when the vapor partial pressure remained below saturation. Similar observations have been reported by Walde et al. [45] for oyster and button mushrooms dried under a vacuum at 50 °C.

For mushrooms dried in the convective oven, a constant-rate period persisted until a moisture content of approximately 5 kg H2O/kg dm, followed by a falling-rate period at lower moisture levels.

At 70 °C in the vacuum oven, two distinct falling-rate periods were identified. The first occurred when the moisture level reached approximately 2 kg H2O/kg dm, followed by a marked decline in the drying rate. Citric acid-pretreated samples exhibited a constant-rate period extending to approximately 6 kg H2O/kg dm, likely due to enhanced cellular swelling from the pretreatment, resulting in higher interstitial moisture and a surface evaporation-controlled drying process at a constant rate. In vacuum drying, the relative humidity is reduced because the pressure is low and was not measured.

For convective drying at 70 °C, two drying-rate periods were observed: an initial constant-rate stage to approximately 2 H2O/kg dm, followed by a falling-rate period. The highest drying rates were achieved in the vacuum oven, consistent with previous studies that reported reduced drying times for edible mushrooms under vacuum conditions [45,46,47].

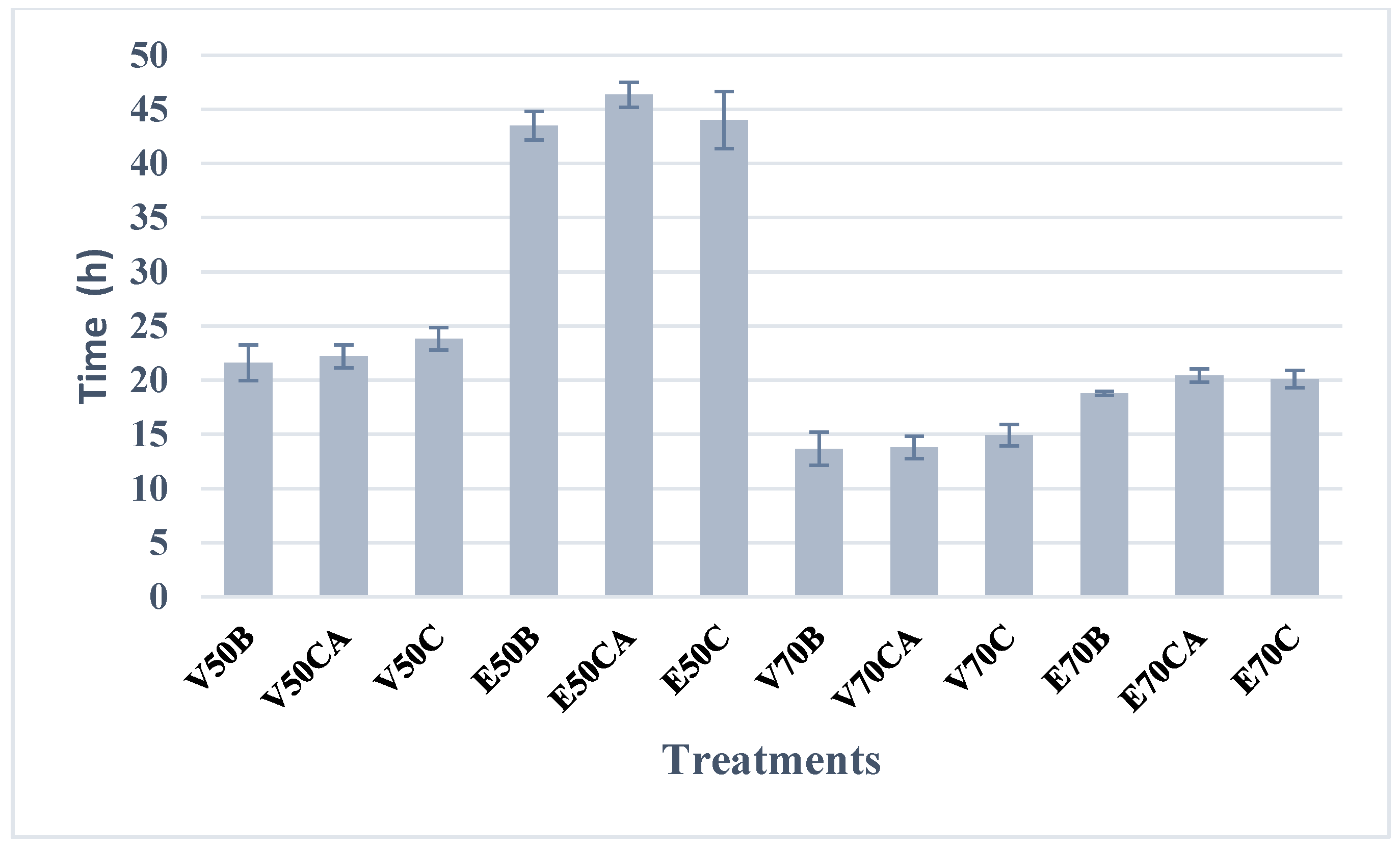

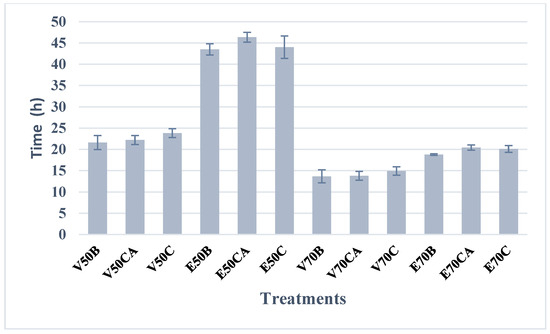

As illustrated in Figure 2, drying at 70 °C resulted in shorter drying times, with the vacuum oven exhibiting the shortest times. At this temperature, the removal of free moisture was most significant during the first seven hours across all six treatments, with water removal occurring most rapidly under vacuum drying conditions. Beyond this initial period, the drying rate decreased progressively until equilibrium moisture was reached under the specified drying conditions.

Figure 2.

Drying of edible Suillus luteus mushrooms. The final equilibrium moisture content ranged between 0.01 and 0.02 kg H2O/kg of dry matter, being reached after 14 h (vacuum drying at 70 °C) and 44 h (oven drying at 50 °C), depending on the treatment.

3.2. Diffusion Model in the Mushroom Drying Process

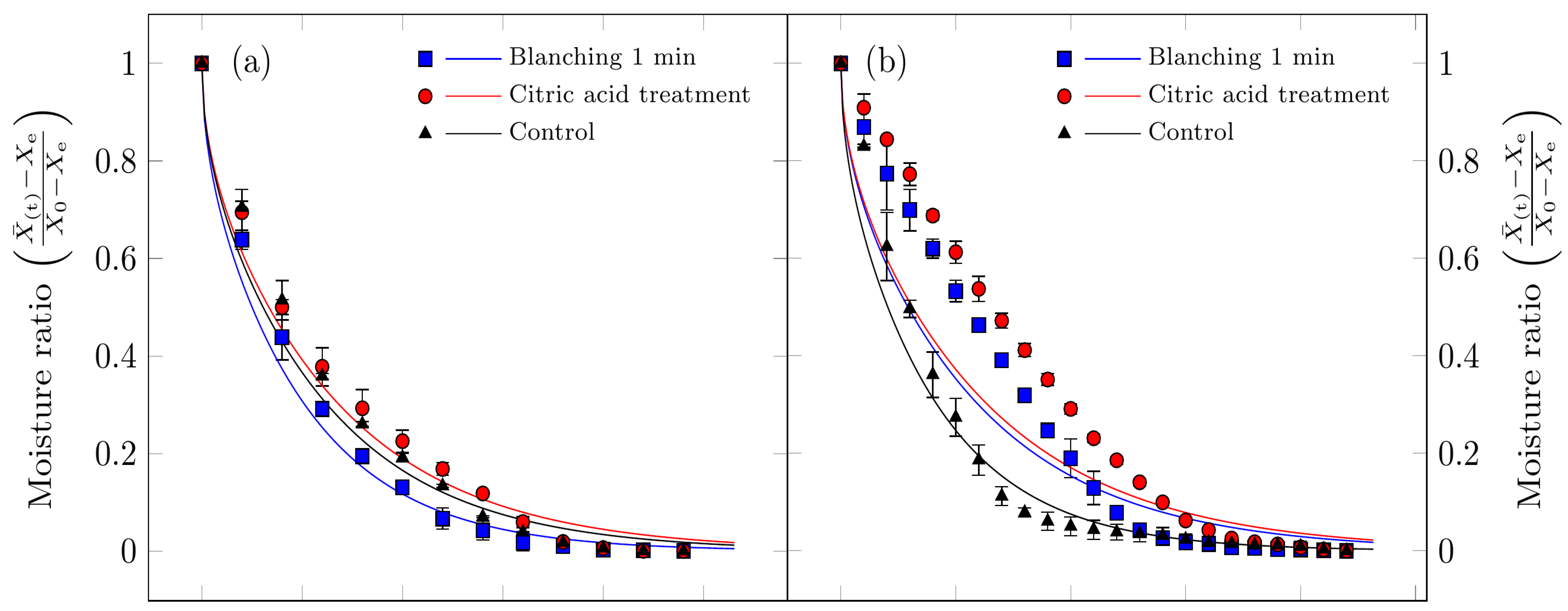

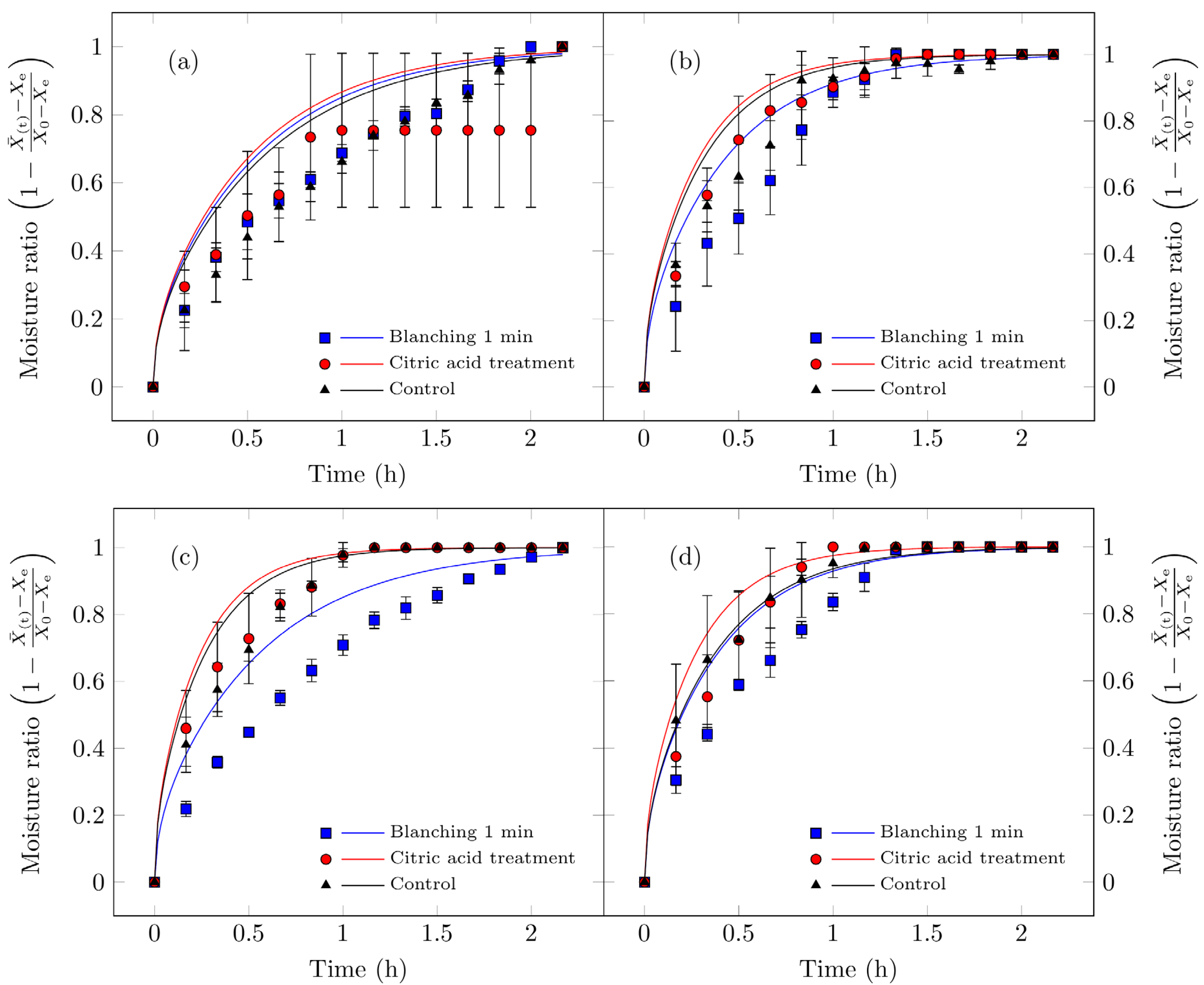

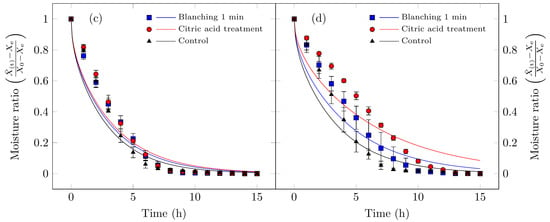

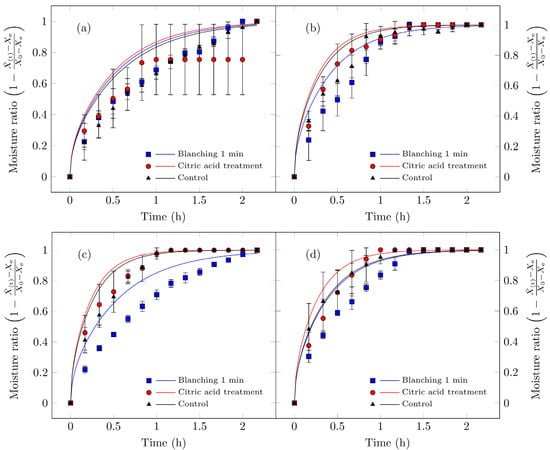

Figure 3 presents both the experimental moisture content data and the values calculated using Fick’s diffusion model. As expected, the free moisture content decreased over time for all drying processes studied.

Figure 3.

Drying curves for Suillus luteus mushrooms under the following conditions: (a) vacuum oven drying at 50 °C, (b) convective oven drying at 50 °C, (c) vacuum oven drying at 70 °C, and (d) convective oven drying at 70 °C. Experimental data are represented by points, and solid lines indicate values fitted using Fick’s diffusion model (Equation (3)).

For vacuum oven drying at 50 °C, as discussed in the drying rate section, both moisture content and drying rate decrease continuously throughout the drying period. This behavior indicates that the underlying physical mechanism governing moisture transport is dominated by internal vapor diffusion. In other words, water is transported from the interior tissue to the drying air at a rate slower than the surface evaporation [48]. These observations are consistent with previous studies on various food products [5,7,49,50].

For the other treatments, the diffusion model exhibited lower predictive accuracy. This is attributable to the fundamental assumption of the diffusion model, namely that internal moisture forces govern the drying process, which is not fully satisfied. In these cases, a constant-rate drying period was observed at the onset (Figure 4b,d), during which, the high surface maintained the sample’s surface in a continuously wet state. Under such conditions, the drying process is governed by convective mass transfer, a factor not accounted for in the initial model assumptions. Additionally, several treatments exhibited multiple falling-rate periods.

Figure 4.

Drying kinetics curves for Suillus luteus mushrooms under the following conditions: (a) vacuum oven drying at 50 °C, (b) convective oven drying at 50 °C, (c) vacuum oven drying at 70 °C, and (d) convective oven drying at 70 °C. The points represent experimental data, while the solid lines correspond to the data fitted using the Midilli model (Table 2).

As summarized in Table 3, all treatments demonstrated high correlation coefficients (0.956 < R2 < 0.995) and relatively low chi-square values. For vacuum oven drying at 50 °C, the continuous decline in both moisture content and drying rate over time corroborates that the dominant mechanism controlling moisture migration is internal vapor diffusion or bound water transport from the tissue to the drying air, occurring at a slower rate than surface evaporation [48]. These findings agree with previous studies on other food products [5,7,49,50].

Table 3.

Effective diffusivity values for the drying of Suillus luteus mushrooms.

Considering effective diffusivity as a quantitative metric for evaluating drying processes, Table 3 demonstrates that drying at 70 °C is substantially more efficient than at 50 °C. This enhanced efficiency is attributable to the increased kinetic energy of water molecules at higher temperatures, which accelerates moisture transport. Notably, for vacuum oven drying at 70 °C, pretreatment did not significantly influence effective diffusivity. In contrast, for the other treatments, pretreatment exerted a significant influence, particularly the citric acid pretreatment, which exhibited a higher water retention capacity, thereby reducing the effective diffusivity.

The effective diffusivity values for the drying of Suillus luteus mushrooms (Table 3) ranged from 3.505 × 10−9 ± 7.268 × 10−10 m2s−1 to 1.477 × 10−8 ± 3.147 × 10−9 m2s−1, consistent with the values reported for convective drying of food products and comparable with the values of 4.084 × 10−10 m2s−1 to 1.78 × 10−9 m2s−1 reported by Da Silva et al. [51], with previous studies reporting effective moisture diffusion coefficients ()) of 5.96 × 10−10 m2s−1 and 10.15 × 10−10 m2s−1 for both mushrooms, and was within the range of moisture diffusion values for food ingredients (10−10 to 10−6 m2s−1) [52].

The experimental logarithmic moisture ratio ln(MR) as a function of time for drying at 50 °C yielded slopes ranging from −0.4533 to −1.257, with high coefficients of determination (R2 > 0.9088). Similarly, at 70 °C, slopes varied from −0.3454 to −0.9682, with R2 > 0.918. The fitted Deff values indicate that Fick’s second law of diffusion accounts for at least 95% of the experimental data at both drying temperatures.

As expected, effective moisture diffusivity increased with drying temperature. Moreover, pretreated samples exhibited higher Deff values compared with untreated controls (Table 3), who noted that fat content significantly reduces water diffusivity. Pretreatment solutions likely influenced internal mass transfer during drying. The effective diffusivity values obtained are within the general range for food materials (10−12 to 10−8 m2s−1) [35], consistent with reports from other researchers [7].

In the drying of mushroom (Suillus luteus), there is high structural variability, such as thickness, and porosity changes over time, which affects the internal moisture gradient, local temperature, and surface area (equation: ). Indeed, with only two temperature points, it is highly sensitive to experimental error; any small error in the temperature difference causes large variations in the operating characteristics . In our experiment, these data were considered because they fall within the ranges of other related research.

In the calculated activation energy, the correlation coefficient is 1, because it was determined with two temperatures of 50 °C and 70 °C.

The results clearly indicate that both product morphology and increased drying temperature enhance the solubility and permeability of the cell walls in Suillus luteus, thereby increasing the diffusion coefficient and reducing drying time. Highly effective moisture diffusion coefficients ) of 7.42 × 10−10 and 7.85 × 10−10 m2s−1 have been reported [52].

Activation energy (Ea) was calculated according to Equation (4). For vacuum oven drying with blanching, Ea was 2.59 kJmol−1; for vacuum oven with citric acid pretreatment, 8.44 kJmol−1; for vacuum oven control, 4.89 kJmol−1; for convective oven with blanching, 23.35 kJmol−1; for convective oven with citric acid, 33.01 kJmol−1; and for convective oven control, 29.68 kJmol−1. The coefficient of determination (R2 = 1) indicates that the temperature dependence of the drying process is accurately represented by the Arrhenius equation for all treatments. These Ae values are within the typical range for foods (12.7–110 kJmol−1) according to Doymaz [31]. For reference, Ae values of 23 and 21 kJmol−1 have been reported for P. florida and P. sajor-caju, respectively [52]. In shiitake mushrooms, drying followed zero-order kinetics with increasing temperature: the z-value for hardness was 49.67 °C (Ea = 25.92 kJmol−1), and the z-value for moisture content was 67.31 °C (Ea = 37.32 kJmol−1) [53].

3.3. Fitting of Kinetic Models for Drying of Suillus luteus

Mass transfer phenomena during drying are commonly described using drying kinetic equations, as discussed in Section 2.3. The quality of fit for each model depends on the drying conditions, type of dryer, and the physical characteristics of the material. The fitting results for the kinetic models evaluated in this study are presented in Table 4 and Table 5, including parameters and statistical data for the drying models analyzed.

Table 4.

Mathematical models of moisture ratio and drying time for Suillus luteus mushrooms at 50 °C.

Table 5.

Mathematical models of moisture ratio and drying time for Suillus luteus mushrooms at 70 °C.

All the mathematical models evaluated demonstrated a satisfactory fit to the experimental data (0.9474 < R2 < 0.9988). However, to identify the model that most accurately represents the drying behavior, the selection criteria prioritized the lowest chi-square values (χ2) and highest R2 values. On the basis of these parameters, the Midilli model exhibited the most suitable indicators for describing the dehydration process of Suillus luteus mushrooms, characterized by low χ2 values and high R2 values (Table 4 and Figure 4).

In accordance with previous research, the semi-empirical model has been widely applied to describe the drying curves of mushrooms, pistachios, pollen, and grape by-products [33,54], arranged in thin layers. Studies on edible mushrooms have also demonstrated the superiority of the Midilli model in predicting the drying kinetics for chanterelle mushrooms [55], Agaricus bisporus [56,57,58,59], and Lentinus edodes [19]. The most distinctive feature of the model proposed by Midilli et al. [33] over other models lies in the incorporation of a linear term (), which confers the ability to simultaneously describe both the constant-rate and falling-rate drying periods. In the present study, constant-rate periods were observed at high moisture levels, during which the mushrooms’ surface remained continuously saturated with water. The Midilli model is useful for describing the drying kinetics of mushrooms in thin layers, but it has limitations in adaptability and extrapolation, does not consider quality aspects beyond water loss, does not incorporate microstructural effects, and has weaknesses such as a lack of preference compared with simpler models with better fits, an excess of parameters, its empirical nature, and its sensitivity to drying conditions [56,57,58,59].

The modified Henderson–Pabis model, characterized by the highest correlation coefficient (R2) and the lowest root mean square error (RMSE) and chi-square (χ2) values, provided the best fit for each drying curve [60]. The statistical parameters of the Midilli et al. model provided the most accurate thin-layer drying representation of the drying kinetics of chanterelle mushrooms [55].

Drying mushrooms presents specific challenges due to their structural and morphological characteristics. Çelen et al. [57] investigated the convective drying behavior of mushrooms under varying temperatures and slice thicknesses, showing that temperature significantly influences moisture removal, with the logarithmic model yielding the best fit. Similarly, Doymaz [31] studied the effect of pretreatment on mushroom slice drying and rehydration, observing improvements in pretreated samples; the drying process predominantly occurred during the falling-rate period, and the logarithmic model best represented the experimental data. In contrast, Guo et al. [19] analyzed the dehydration of Lentinus edodes mushrooms using nine classical mathematical models and found that the Midilli–Kuck model provided the best fit. Likewise, Shanker et al. [9] investigated the drying of oyster mushrooms using convective, vacuum, and solar drying methods at temperatures ranging from 60 to 80 °C, with pretreatments including blanching, citric acid, and sodium metabisulfite. Among the models tested, the Page model provided the best representation of the drying kinetics of oyster mushrooms, followed by the Modified Page model.

As shown in Table 3 and Table 4, the magnitude of the drying rate constant () varied significantly as a function of the external drying conditions [61]. The data obtained here indicate that the drying rate increased more markedly under vacuum conditions than with a simple increase in temperature. In most drying models (Newton, Page, Henderson–Pabis, logarithmic, Midlilli, etc.), the constant is called the drying constant, and its interpretation varies from model to model. In empirical models such as those of Newton, Page, Henderson–Pabis, or Midilli, represents an adjusted parameter that reflects the apparent rate of the process and other associated parameters (such as ). In contrast, in models based on the Fick equations, k is directly related to the effective diffusion coefficient (). Therefore, the values of are not comparable between different models.

The pretreatment of the samples also exerted a notable influence on the drying kinetics under vacuum conditions (Figure 4b,d). Samples subjected to blanching and citric acid pretreatment exhibited higher moisture retention compared with untreated control samples. Similar behavior was observed at both 50 and 70 °C. The effect of such treatments on drying characteristics has also been reported in previous studies involving various agricultural products [62].

3.4. Rehydration of Edible Mushrooms (Suillus luteus)

As summarized in Table 6, the final moisture content after rehydration was significantly influenced by both the pretreatment type and drying method (Tukey’s HSD, 5%). At 50 °C, control samples (without pretreatment) achieved the highest final moisture levels under both convective drying (2.99 ± 0.31 g H2O/g dm) and vacuum drying (3.47 ± 1.33 g H2O/g dm), surpassing those subjected to blanching or citric acid pretreatments (≈1.25–1.33 g H2O/g dm). A similar trend was observed at 70 °C, wherein the control samples maintained higher moisture values than pretreated ones. Conversely, mushrooms pretreated with blanching or citric acid showed intermediate values ranging from ≈1.15 to 1.50 g H2O/g dm. These results demonstrate that pretreatments decreased the final rehydrated moisture content relative to the control samples across all drying conditions evaluated. A higher rehydration capacity generally indicates better quality of the dried products [28,63,64].

Table 6.

Final moisture values after rehydration of Suillus luteus mushrooms.

The fitting of the diffusional model (Table 7) adequately described the experimental drying curves (R2 ≈ 0.83–0.99; low χ2 values), yielding effective diffusivities within the range of 1.14 × 10−8 to 2.80 × 10−8 m2s−1. At 50 °C, the highest diffusivity values corresponded to vacuum drying, specifically for the citric acid pretreatment (2.39 × 10−8 m2s−1) and the control sample (2.18 × 10−8 m2s−1). At 70 °C, the highest values were observed for convective drying with citric acid pretreatment (2.80 × 10−8 m2s−1) and for vacuum drying with citric acid pretreatment (2.48 × 10−8 m2s−1).

Table 7.

Effective diffusivity values for the rehydration of Suillus luteus mushrooms.

The lower final moisture content observed in blanched or citric acid-treated samples compared with the controls suggests the occurrence of microstructural alterations, such as pore collapse, cell wall protein denaturation, or thermal browning. These alterations restrict water retention capacity despite facilitating initial water penetration. Similar trends have been reported for Agaricus bisporus and other edible mushrooms [65,66]. Likewise, Espinoza-Ticona et al. [43] reported higher rehydration ratios in untreated samples and those pretreated with vinegar, reaching 4.75 and 3.55 g H2O/g dm, respectively. The lowest rehydration values were observed in lemon-pretreated samples, with 2.84 and 2.14 g H2O/g dm. Argyropoulos et al. [67] reported a rehydration range of 3.17–7.87 g H2O/g dm in mushrooms pretreated with 1% citric acid for 5 min. The higher diffusivity observed in citric acid-treated samples (particularly at 70 °C) aligns with previous findings indicating that acid pretreatments can enhance mass transfer, shorten drying time, and/or increase effective diffusivity coefficients by altering the cellular matrix and permeability; however, the effect on final rehydration is not always beneficial when structural damage accumulates [68].

The effective rehydration diffusivity values on the order of 10−8 m2s−1 are consistent with the ranges reported for rehydration and reconstitution processes in mushrooms and other porous plant matrices, typically spanning from 10−10 to 10−8 m2s−1, depending on the temperature, porosity, and experimental methodology [63,69]. The food fit of the Fick diffusion model (R2 ≈ 0.99; low χ2 values) agrees with the widespread use of diffusional models to describe rehydration kinetics in mushrooms and porous food materials in general [70].

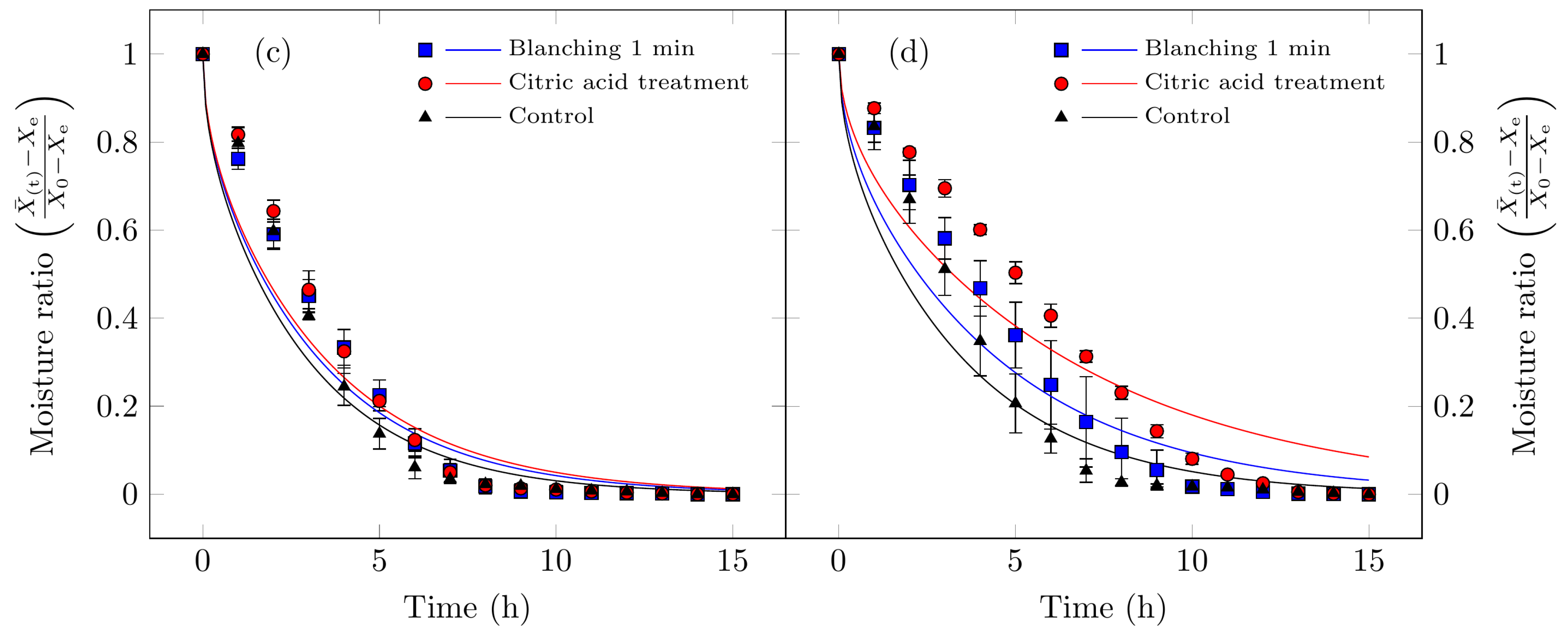

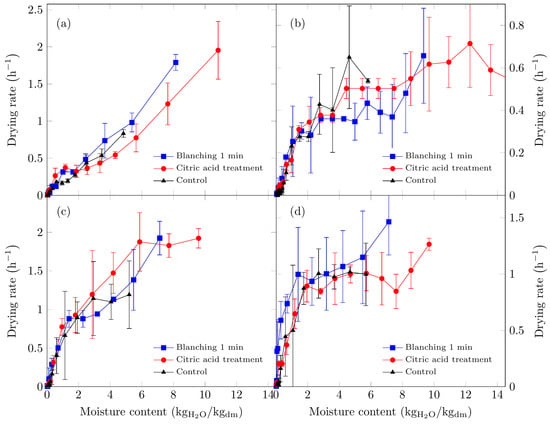

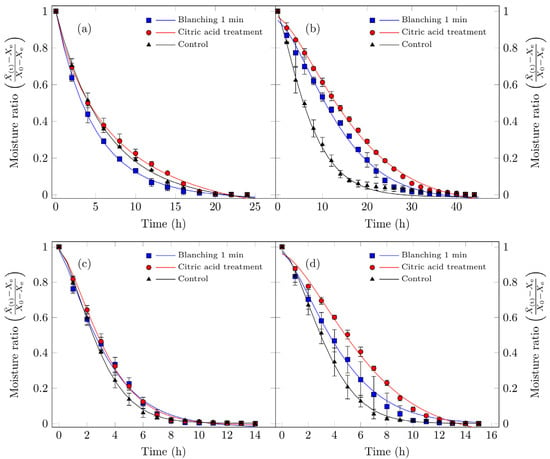

Figure 5 illustrates the rehydration kinetics of Suillus luteus mushrooms subjected to different drying conditions. The experimental results indicate that vacuum drying better preserves their microstructural integrity, thereby enhancing rehydration, particularly for untreated control samples, which exhibited the highest rehydration values. Moreover, these samples displayed consistent effective diffusivity values. These findings align with the findings of Giri and Prasad [46], who reported that vacuum drying maintains superior microstructural integrity (reduced collapse and increased porosity) relative to conventional convective drying, resulting in improved rehydration characteristics. The minimal impact on cellular structure (greater porosity/lower damage under reduced pressure) is consistent with recent studies on mushrooms and other porous matrices subjected to mild drying technologies [71].

Figure 5.

Hydration curves for edible Suillus luteus mushrooms dried under the following conditions: (a) vacuum oven drying at 50 °C, (b) convective oven drying at 50 °C, (c) vacuum oven drying at 70 °C, and (d) convective oven drying at 70 °C. Data points represent experimental measurements, and the continuous lines correspond to values fitted using the Fick model for hydration (Equation (6)). All treatments, including the samples treated with citric acid and dried under vacuum at 50 °C, reach a dimensionless moisture content of 1. In this specific treatment, a plateau is observed between approximately 1 and 2 h of rehydration before the moisture content finally reaches 1 at the end of the process. At this endpoint, the curves of all treatments converge, and this overlap may give the impression that a data point is missing for the citric acid treatment.

Increasing the drying temperature enhanced the effective diffusivity of the process but simultaneously reduced the rehydration capacity of the dried mushrooms. This effect can be attributed to structural collapse: experimental data indicate that samples dried at 70 °C exhibited higher diffusivity, particularly those pretreated with citric acid, yet did not achieve proportionally higher final moisture contents. Such behavior has been widely documented in mushrooms (e.g., shiitake, Agaricus bisporus) and other porous food matrices, where accelerated drying kinetics can be accompanied by reduced reconstitution capacity when structural damage surpasses a critical threshold [72,73]. Consequently, mushrooms dried at lower temperatures experience less cellular disruption and display higher rehydration rates than those subjected to elevated temperatures [63]. Doymaz et al. [31] evaluated Agaricus bisporus pretreated with citric acid and dried at 25 °C and 50 °C, reporting that lower drying temperatures improved rehydration capacity, consistent with the present findings, suggesting that both temperature and pretreatment significantly influence rehydration performance.

Rehydration models attempt to describe a highly complex physicochemical phenomenon.

The drying process permanently destroys and alters the mushrooms’ structure, and simple models cannot account for this damage, such as structural collapse and surface hardening. Rehydration models measure net weight gain over time. However, net weight gain is not the same as water absorption. The rehydration process is not a single, smooth curve. It occurs in stages, as empirical models do: rapid capillary absorption, slow diffusion, swelling, and equilibrium. The model treats the mushroom sample as a single, homogeneous, and isotropic block.

3.5. Dimensional Contraction of Suillus luteus

A thickness of 0.45 cm was considered for blanching and cooking in acid, and 0.4 cm for the control, and dimensional contraction was calculated using Equation (7) as shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Dimensional contraction of Suillus luteus mushrooms.

The greatest shrinkage with respect to thickness was observed in the treatment with citric acid (92.8%) dried in a vacuum oven at 70 °C, and the one that had the least shrinkage (86.5%) was the control treatment dried in the vacuum oven at 50 °C. These results are consistent with what was mentioned by Tran et al. [52], namely that as the temperature and speed of drying increase, the percentage of shrinkage increases, resulting in a change in the color and appearance of the mushroom. Water loss during mushroom dehydration causes a reduction in volume; this radial contraction stabilizes when the mushroom cells stop deforming due to drying. The contraction causes changes in cell structure that can damage the cells, affecting the quality of the dehydrated mushroom and its subsequent hydration [74].

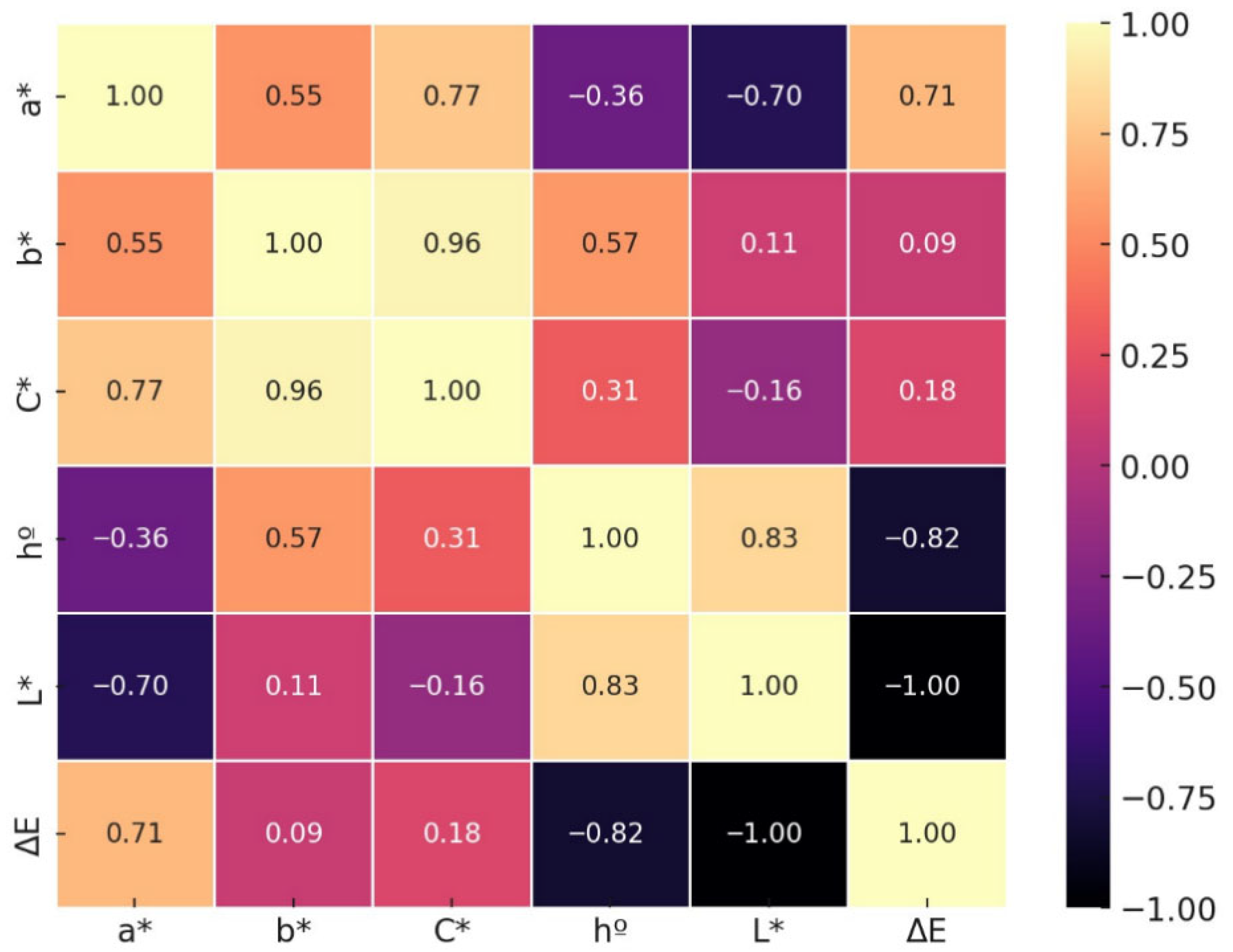

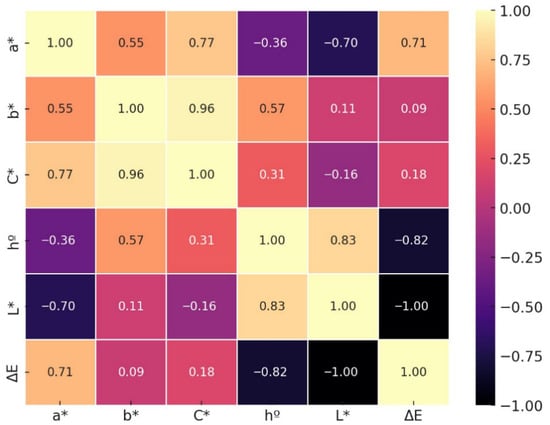

3.6. Color Correlation Matrix of Suillus luteus

The correlation matrix (Figure 6) of instrumental color variables in Suillus luteus revealed statistically significant relationships (p < 0.05), providing a detailed understanding of the interactions among chromatic parameters during dehydration. A strong negative correlation was observed between lightness (L*) and total color difference (ΔE), indicating that a reduction in mushroom brightness is associated with a greater deviation from its fresh state, which is critical for sensory and commercial perception.

Figure 6.

Correlation matrix of chromatic variables in Suillus luteus subjected to different drying methods and pretreatments.

Additionally, strong positive correlations among a* (green–red), b* (blue–yellow), and chroma (C*) indicate that variations in color intensity and saturation occur in a coordinated matter, likely because of shared chemical reactions such as the Maillard product formation induced by high temperature drying.

The hue angle (h°) displayed moderate correlations with the other chromatic variables, suggesting that while it influences perceived color tone, its behavior is partially independent of both color intensity and lightness.

The strong negative correlation between lightness (L*) and total color difference (ΔE) indicates that reductions in brightness constitute a primary factor influencing the visual quality of dehydrated mushroom. This finding highlights the necessity of optimizing drying processes to minimize excessive darkening, thereby preserving perceived product quality. These observations are consistent with prior studies identifying lightness as a critical parameter for assessing freshness and acceptability [63,75].

In contrast, a*, b*, and chroma (C*) exhibited strong positive interrelationships, suggesting that chemical transformations influencing color saturation and hue act in a coordinated manner during the drying process. This pattern is likely associated with non-enzymatic browning reactions, particularly the Maillard reaction, which generates dark pigments and contributes to the observed chromatic modifications [7,76]. The hue angle, while less strongly correlated with the other colorimetric parameters, remains a relevant indicator for tracking modifications in hue independent of saturation or lightness, implying that drying can selectively alter chromatic tones and, consequently, the overall visual perception of the product [77].

4. Conclusions

The drying process of Suillus luteus mushrooms is strongly modulated by the temperature, drying method, and pretreatment. Among the conditions evaluated, vacuum drying at 70 °C with blanching pretreatment (V70B) was the most efficient, significantly reducing drying time and enabling greater water removal compared with conventional convective drying. These results indicate that reduced pressure drying facilitates moisture migration, thereby accelerating the drying process.

The semi-empirical Midilli model outperformed other models in characterizing the drying kinetics of S. luteus, effectively capturing both the constant- and falling-rate periods within a single equation. The diffusion model of Fick demonstrated satisfactory agreement under specific conditions, providing complementary insights into the mass transfer mechanisms.

Regarding product quality, both pretreatment and drying methods significantly influenced rehydration capacity and visual attributes. Untreated samples demonstrated superior rehydration, suggesting better preservation of the internal structure, whereas blanched and vacuum-dried samples better retained color, approximating the appearance of fresh mushrooms. The greatest shrinkage was observed in those that were pretreated with citric acid and blanching. Colorimetric analysis confirmed that vacuum drying combined with blanching effectively preserves chromatic properties, a determinant of commercial acceptability.

These findings underscore the importance of carefully selecting the drying parameters and pretreatments to produce high-quality dehydrated mushrooms. Integrating drying kinetics studies with colorimetric analysis provides a comprehensive basis for optimizing drying processes to preserve both structural and visual attributes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: G.C.-Q. and F.L.; methodology: A.F.-A., L.F.P.-F., and F.L.; software: A.F.-A., F.L., and V.J.H.-M.; validation: V.J.H.-M.; formal analysis: A.F.-A., L.F.P.-F., and F.L.; investigation: L.F.P.-F.; resources: G.C.-Q.; data curation: V.J.H.-M. and L.F.P.-F.; writing—original draft preparation: A.F.-A., F.L., and V.J.H.-M.; writing—review and editing: A.F.-A., L.F.P.-F., V.J.H.-M., and G.C.-Q.; visualization: F.L. and V.J.H.-M.; supervision: G.C.-Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in article.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the Escuela Profesional de Ingenieria Agroindustrial at the Universidad Nacional Micaela Bastidas de Apurímac UNAMBA for providing the necessary facilities for the experimental phase of this study, particularly the Processing Laboratory of Agroindustrial Products and the General Chemistry Laboratory. And the Vicerrectorado de Investigación of UNAMBA for their support in publishing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kalač, P.A. Review of chemical composition and nutritional value of wild-growing and cultivated mushrooms. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashir, A.; Vaida, N.; Ahmad Dar, M. Medicinal importance of mushrooms: A review. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2014, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Heleno, S.A.; Ferreira, R.C.; Antonio, A.L.; Queiroz, M.J.R.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C. Nutritional value, bioactive compounds and antioxidant properties of three edible mushrooms from Poland. Food Biosci. 2015, 11, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Mehra, R.; Guiné, R.P.; Lima, M.J.; Kumar, N.; Kaushik, R.; Ahmed, N.; Yadav, A.N.; Kumar, H. Edible Mushrooms: A Comprehensive Review on Bioactive Compounds with Health Benefits and Processing Aspects. Foods 2021, 10, 2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K. Role of edible mushrooms as functional foods—A review. South Asian J. Food Technol. Environ. 2015, 1, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R. Medicinal importance of mushroom. Asian J. Hort. 2018, 13, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurozawa, L.E.; Azoubel, P.M.; Murr, F.E.X.; Park, K.J. Drying kinetic of fresh and osmotically dehydrated mushroom (Agaricus blazei). J. Food Process Eng. 2012, 35, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oancea, S.; Popa, M.; Socaci, S.A.; Dulf, F.V. Comparative study of raw and dehydrated Boletus edulis mushrooms by hot air and centrifugal vacuum processes: Functional properties and fatty acid and aroma profiles. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanker, M.A.; Sehrawat, R.; Pareek, S.; Nema, P.K. Physico-chemical properties and drying kinetic evaluation of hot air and vacuum dried pre-treated oyster mushroom under innovative multi-mode developed dryer. Int. J. Hort. Sci. Technol. 2022, 9, 363–374. [Google Scholar]

- Popa, M.; Tăușan, I.; Drăghici, O.; Soare, A.; Oancea, S. Influence of convective and vacuum-type drying on quality, microstructural, antioxidant and thermal properties of pretreated Boletus edulis mushrooms. Molecules 2022, 27, 4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guine, P.F.R.; Barroca, M.J. Influence of freeze-drying treatment on the texture of mushrooms and onions. Croat. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 3, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sabarez, H.T. Chapter 4: Modelling of drying processes for food materials. In Modeling Food Processing Operations; Food Science, Technology and Nutrition; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 95–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Sharma, H.K. Chapter 5: Drying. In Agro-Processing and Food Engineering Operational and Application Aspects; Sharma, H.K., y Kumar, N., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 147–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, R.T.; Singh, R.K.; Kong, F. Dehydration. In Fundamentals of Food Process Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 321–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabarez, H.T. Computational modeling of the transport phenomena occurring during convective drying of prunes. J. Food Eng. 2012, 111, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikiatden, J.; Roberts, J.S. Moisture Transfer in Solid Food Materials: A Review of Mechanisms, Models, and Measurements. Int. J. Food Prop. 2006, 10, 739–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk, Z. (Ed.) Chapter 22: Dehydration. In Food Process Engineering and Technology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 513–566. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/chapter/monograph/abs/pii/B9780128120187000221?via%3Dihub (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Akter, F.; Muhury, R.; Sultana, A.; Kumar, U.D. A Comprehensive Review of Mathematical Modeling for Drying Processes of Fruits and Vegetables. Int. J. Food Sci. 2022, 2022, 6195257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.H.; Xia, C.Y.; Tan, Y.R.; Long, C.; Jian, M. Mathematical modeling and effect of various hot-air drying on mushroom (Lentinus edodes). J. Integr. Agric. 2014, 13, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Mejía, N.; Andrade-Mahecha, M.M.; Martínez-Correa, H.A. Modelamiento matemático de la cinética de secado de espagueti enriquecido con pulpa de zapallo deshidratada (Cucurbita moschata). Rev. U.D.C.A. Actual. Divulg. Cient. 2019, 22, e1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramarao, K.D.R.; Razali, Z.; Somasundram, C. Mathematical models to describe the drying process of Moringa oleifera leaves in a convective-air dryer. Czech J. Food Sci. 2021, 39, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.S.; Corrêa, P.C.; Silva, G.N.; Lopes, L.M.; De Sousa, A.H. Kinetics and mathematical modeling of the drying process of macaúba almonds. Rev. Caatinga Mossoró. 2022, 35, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reppich, M.; Jegla, Z.; Grondinger, J.; Azouma, Y.O.; Turek, V. Mathematical modeling of drying processes of selected fruits and vegetables. Chem. Ing. Tech. 2021, 93, 1581–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananda, P.D.; Kumar, G.S.; Kumar, S.A. Drying Kinetics and Mathematical Modelling of Raisin Production by Abrasive and Chemical Pre-Treatment of Grapes: Drying kinetics of grape with abrasive process. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2024, 83, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaquilla-Quilca, G.; Pérez-Falcón, L.F.; Lozano, F.; Fernandez-Ayma, A.; Espinoza-Ticona, Y.; Silva-Paz, R.J.; Huamaní-Meléndez, V.J. Dehydration of Suillus luteus mushroom at different drying temperature, drying method, and pretreatment. Cienc. Agrotec. 2024, 48, e016624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engin, D. Effect of drying temperature on color and desorption characteristics of oyster mushroom. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 40, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maray, A.R.; Mostafa, M.K.; El-Fakhrany, A.E.D.M. Effect of pretreatments and drying methods on physico-chemical, sensory characteristics and nutritional value of oyster mushroom. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2018, 42, e13352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, F.R.; Medany, G.M. Effect of pretreatments and drying temperatures on the quality of dried Pleurotus mushroom spp. Egypt. J. Agric. Res. 2014, 92, 1009–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujumdar, A.S. (Ed.) Handbook of Industrial Drying; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; p. 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, J.M.P.Q.; Barbosa de Lima, A.G. Transport Phenomena and Drying of Solids and Particulate Materials; Advanced Structured Materials; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; p. 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertekin, C.; Firat, M.Z. A Comprehensive Review of Thin-Layer Drying Models Used in Agricultural Products. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 701–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simha, P.; Gugalia, A. Thin Layer Drying Kinetics and Modelling of Spinacia oleracea Leaves. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Res. 2013, 8, 1053–1066. [Google Scholar]

- Midilli, A.; Kucuk, H.; Yapar, Z.A. new model for single-layer drying. Dry. Technol. 2002, 20, 1503–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratti, C. Advances in Food Dehydration; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Heldman, D.R.; Lund, D.B.; Sabliov, C. Handbook of Food Engineering; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; p. 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. 930.04 Loss on Drying (Moisture) in Plants. In Official Methods of Analysis, 17th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 1995.

- American Association of Cereal Chemists (AACC). Approved Methods of the AACC, 8th ed.; American Association of Cereal Chemists: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Mayor, L.; Sereno, A.M. Modelling shrinkage during convective drying of food materials: A review. J. Food Eng. 2004, 61, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujumdar, A.S. (Ed.) Chapter 4, Experimental technics in drying. In Handbook of Industrial Drying, 4th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathias-Rettig, K.; Ah-Hen, K. El color en los alimentos un criterio de calidad medible. Agro Sur 2014, 42, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, H.; de la Vara Salazar, R. Análisis y Diseño de Experimentos; Interamericana Editores, S.A. de C.V., Ed.; McGRAW-HILL: Mexico City, Mexico, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jacinto-Azevedo, B.N.; Valderrama, K.; Henríquez, M.; Aranda, P.A. Nutritional value and biological properties of Chilean wild and commercial edible mushrooms. Food Chem. 2021, 356, 129651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza-Ticona, Y.; Lozano, F.; Moreano-Alarcón, L.; Calixto-Muñoz, J.J.; Chaquilla-Quilca, G. Pre-treatments and drying methods on the physicochemical and sensory characteristics of wild mushrooms (Suillus luteus) from Apurimac-Perú. Chil. J. Agric. Anim. Sci. 2023, 39, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivanovic, S.; Busher, R.W.; Kim, K.S. Textural changes in mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus) associated with tissue ultrastructure and composition. J. Food Sci. 2000, 65, 1404–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walde, S.G.; Velu, V.; Jyothirmayi, T.; Math, R.G. Effects of pretreatments and drying methods on dehydration of mushroom. J. Food Eng. 2006, 74, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, S.K.; Prasad, S. Drying kinetics and rehydration characteristics of microwave-vacuum and convective hot-air dried mushrooms. J. Food Eng. 2007, 78, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, F.; Kashaninejad, M.; Jafarianlari, A. Drying kinetics and characteristics of combined infrared-vacuum drying of button mushroom slices. Heat Mass Transfer 2017, 53, 1751–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duangkhamchan, W.; Wiset, L.; Poomsa-ad, N. Evaluation of drying and moisture sorption characteristics models for Shiitake mushroom (Lentinussquarrosulus Mont.) and Grey Oyster mushroom (Pleurotussajor-caju (fr.) Singer). J. Sci. Technol. 2013, 20, 151–166. [Google Scholar]

- Xanthopoulos, G.; Lambrinos, G.; Manolopoulou, H. Evaluation of thin-layer models for mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) drying. Dry. Technol. 2007, 25, 1471–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpinar, E.K.; Bicer, Y. Modelling of the drying of eggplants in thin-layers. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2005, 40, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, C.K.F.; Da Silva, Z.E.; Mariani, V.C. Determination of the diffusion coefficient of dry mushrooms using the inverse method. J. Food Eng. 2009, 95, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.N.T.; Khoo, K.S.; Chew, K.W.; Phan, T.Q.; Nguyen, H.S.; Nguyen-Sy, T.; Show, P.L. Modelling drying kinetic of oyster mushroom dehydration—The optimization of drying conditions for dehydratation of Pleurotus species. Mater. Sci. Energy Technol. 2020, 3, 840–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Meng, Y.; Dang, Y.; Guo, S.; Qu, S.; Li, J.; Li, Y. Dynamics of quality change in process of shiitake mushroom (Lentinus edodes) cooking. J. Food Process Eng. 2023, 46, e14398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celma, A.R.; López-Rodríguez, F.; Cuadros Blázquez, F. Experimental modelling of infrared drying of industrial grape by-products. Food Bioprod. Process. 2009, 87, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, M.; Liu, Z.; Fang, Y.; Dou, X.; Awuah, E.; Soomro, S.A.; Chen, K. Computational intelligence and mathematical modelling in chanterelle mushrooms’ drying process under heat pump dryer. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 212, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izli, N.; Isik, E. Effect of different drying methods on drying characteristics, colour and microstructure properties of mushroom. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2014, 53, 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Çelen, S.; Kahveci, K.; Akyol, U.; Haksever, A. Drying behavior of cultured mushrooms. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2010, 34, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinani, T.S.; Hamdami, N.; Shahedi, M.; Havet, M. Mathematical modeling of hot air/electrohydrodynamic (EHD) drying kinetics of mushroom slices. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 86, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arıcı, R.Ç.; Mengeş, H.O. Determination of Drying Characteristics and Modelling of Drying Behaviour of Mushroom (Agaricus bisporus). Selcuk. J. Agric. Food Sci. 2012, 26, 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Forouzanfar, A.; Hojjati, M.; Noshad, M.; Szumny, A.J. Influence of UV-B pretreatments on kinetics of convective hot air drying and physical parameters of mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus). Agriculture 2020, 10, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, J.C.S.; Pereira, E.D.; Oliveira, K.P.; Costa, C.H.C.; Feitosa, R.M. Estudo da cinética de secagem da pimenta de cheiro em diferentes temperaturas. Rev. Verde Agroecol. Desenvolv. Sustentável 2015, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doymaz, I. Drying Kinetics and Rehydration Characteristics of Convective Hot-Air Dried White Button Mushroom Slices. J. Chem. 2014, 2014, 453175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, V.; Trandafir, I.; Ionica, M.E. Effects of pretreatments and drying temperatures on the quality of dried button mushrooms. South-West. J. Hortic. Biol. Environ. 2011, 2, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal, S.; Rai, R.D.; Arumuganathan, T.; Kumar, R.; Tewari, R.P.; Khare, V. Effect of pretreatments on the quality and acceptability of the cabinet dried oyster mushroom (Pleurotus florida). Mushroom Res. 2016, 24, 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, S.; Shivhare, U.S.; Ahmed, J.; Raghavan, V. Drying kinetics of Agaricus bisporus and Pleurotus florida mushroom. Trans. ASAE. Am. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2003, 46, 721–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumuganathan, T.; Shwet, K.; Rai, R.D.; Rajesh, K.; Tewari, R.P. Effect of pretreatments on the quality of the cabinet-dried white button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus). Mush. Res. 2015, 24, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Argyropoulos, D.; Heindl, A.; Müller, J. Assessment of convection, hot-air combined with microwave-vacuum and freeze-drying methods for mushrooms with regard to product quality. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 46, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Soto, G.; Ocanña-Camacho, R.; Paredes-López, O. Effect of pretreatment and drying on the quality of Oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus). Dry. Technol. 2001, 19, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezagah, M.E.; Kashaninejad, M.; Mirzaei, H.; Khomeiri, M. Osmotic dehydration of button mushroom: Fickian diffusion in slab configuration. Lat. Am. Appl. Res. 2010, 40, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- García-Pascual, P.; Sanjuán, N.; Bon, J.; Carreres, J.E.; Mulet, A. Rehydration process of Boletus edulis mushroom: Characteristics and modelling. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2005, 85, 1397–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos-Pezos, M.; Muñoz Fariña, O.; Ah-Hen, K.S.; Garrido Figueroa, M.F.; García Figueroa, O.; González Esparza, A.; González Pérez de Medina, L.; Bastías Montes, J.M. Effects of Drying Treatments on the Physicochemical Characteristics and Antioxidant Properties of the Edible Wild Mushroom Cyttaria espinosae Lloyd (Digüeñe Mushroom). J. Fungi 2025, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Segovia, P.; Andrés-Bello, A.; Martínez-Monzó, J. Rehydration of air-dried Shiitake mushroom (Lentinus edodes) caps: Comparison of conventional and vacuum water immersion processes. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 44, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutia, I.; Lakatos, E.; Kovács, A.J. Impact of Dehydration Techniques on the Nutritional and Microbial Profiles of Dried Mushrooms. Foods 2024, 13, 3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Xie, Y.; Wang, H. Computer vision online measurement of shiitake mushroom (Lentinus edodes) surface wrinkling and shrinkage during hot air drying with humidity control. J. Food Eng. 2020, 292, 110253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altikat, S.M.H.; Alma, A.; Gulbe, K.; Küçükerdem, E.K. Effects of different power levels used in microwave drying method on color changes of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus). J. Inst. Sci. Technol. 2022, 12, 2045−2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marçal, S.; Sousa, A.S.; Taofiq, O.; Antunes, F.; Morais, A.M.; Freitas, A.C.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Pintado, M. Impact of postharvest preservation methods on nutritional value and bioactive properties of mushrooms. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 110, 418–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Li, X.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Gao, X. Effects of air-impingement jet drying on drying kinetics, color, polyphenol compounds, and antioxidant activities of Boletus aereus slices. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 2131–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.