Abstract

Distributed drive electric vehicles (DDEVs) offer remarkable advantages in handling stability owing to the independent torque and steering control of each wheel. Traditional in-dependent strategies have the disadvantages of slow response speed and unsmooth control interval switching. To overcome the performance tradeoffs of traditional independent strategies, this study proposes an integrated control approach combining four-wheel steering (4WS) and direct yaw moment control (DYC) to achieve coordinated multiobjective optimization. Based on phase-plane theory, the vehicle’s stable domain is divided using a double line method, and speed-dependent control regions and weights are designed to enable smooth switching between control modes. Simulation results demonstrate that, in high-adhesion conditions, compared with the DYC-only strategy, the integrated system reduces the maximum sideslip angle by about 77.8% and the cost function peak by 22.4%. Moreover, it decreases the maximum rear-wheel steering angle by 38.4% and maximum sideslip angle by about 15.4% compared with 4WS-only strategy. Under low-adhesion conditions, compared with the DYC-only strategy, the integrated system reduces the maximum sideslip angle by about 21.1% and the cost function peak by 37.6%. Additionally, the integrated system decreases the maximum rear-wheel steering angle by 60.2% and maximum sideslip angle by about 64.3% compared with 4WS-only strategy.

1. Introduction

The intelligent chassis serves as the fundamental platform for next generation power systems and plays a crucial role in improving vehicle safety, reliability, and handling. The high-precision control of DDEVs enables more sophisticated vehicle dynamics control. However, the strong coupling among various vehicle subsystems and the inherent nonlinearities in the vehicle dynamics model make it challenging to achieve full six-degree-of-freedom (6-DOF) dynamic control under complex driving conditions. In particular, interference and conflicts frequently arise between the steering and driving systems when performing longitudinal and lateral control tasks. Consequently, integrated coordination between these subsystems is crucial to ensure that vehicles can be operated with greater safety, comfort, and ease, especially in hazardous or dynamically complex environments.

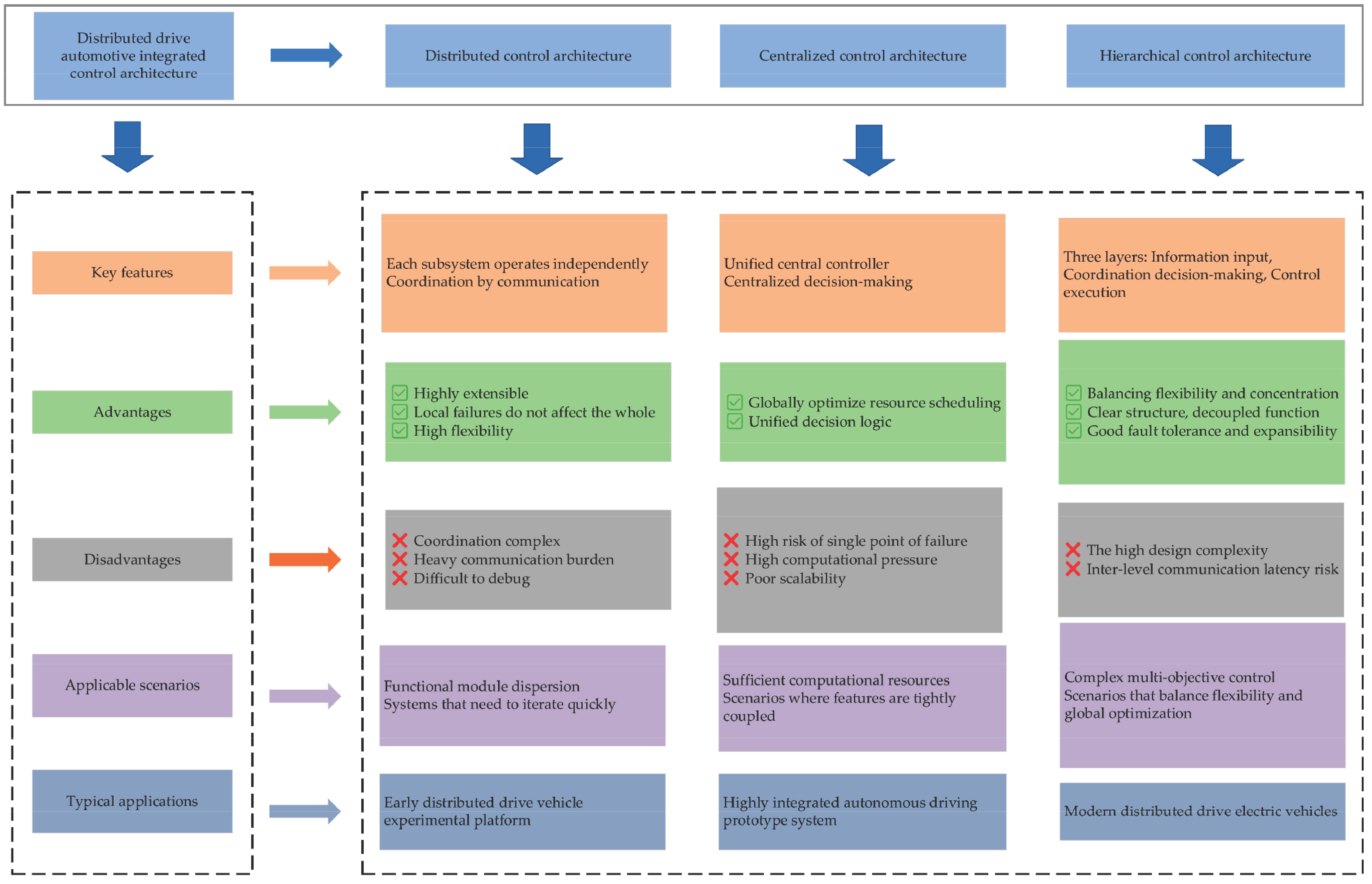

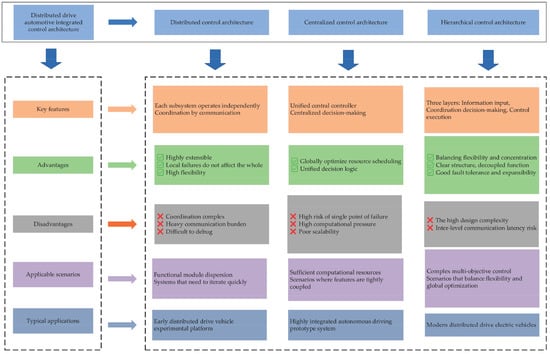

With the enhanced controllability enabled by distributed drive technology, integrated control strategies are gradually evolving from conventional two-dimensional dynamics control toward three-dimensional global cooperative control [1]. Based on the multidimensional coupling characteristics of vehicle dynamics, Etsuko et al. [2] categorized integrated control strategies for DDEVs into four types: longitudinal–lateral, lateral–vertical, longitudinal–vertical, and comprehensive longitudinal–lateral–vertical integrated dynamics control. Fan et al. [3] further proposed that DDEVs’ integrated control architectures can be divided into three principal configurations, as illustrated in Figure 1. The longitudinal and lateral motions of the vehicle are significantly coupled. By adopting integrated strategies that simultaneously optimize longitudinal and lateral tire forces, multidimensional vehicle motion states can be effectively regulated.

Figure 1.

Analysis of the integrated control architecture.

Chen et al. [4] developed a collision-avoidance controller that integrates both longitudinal and lateral control, ensuring stability during maneuvers and guaranteeing collision-free paths through optimal control. Soltani et al. [5] employed an adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference framework to merge active front-wheel steering with active braking, achieving reduced braking distances and improved lateral stability. He et al. [6] integrated a drive system with a stability control system using fuzzy set theory to enhance both handling stability and trajectory-tracking accuracy. Fang et al. [7] combined active front-wheel steering with direct yaw moment control, improving lateral stability and path-tracking precision. Li et al. [8] utilized model predictive control (MPC) to integrate steering and driving systems for improved vehicle posture stability and trajectory-tracking performance. Similarly, Zhao et al. [9] incorporated steering and driving subsystems using adaptive prediction time linear quadratic regulator (APTLQR) and sliding mode control (SMC) strategies to strengthen path-following performance and lateral stability. Mu et al. [10] proposed an integrated control framework that unites steering and driving systems, employing MPC to coordinate lateral path tracking and longitudinal speed regulation.

Four-wheel steering provides higher steering flexibility than front-wheel steering and has been widely used in steering systems, A considerable amount of research has been conducted on the integrated control of four-wheel steering (4WS) and direct yaw moment control (DYC) systems, with a focus on handling stability, path-tracking accuracy, active safety, and system robustness. Zhang et al. [11] introduced a hierarchical control architecture combining a Nash game with MPC to enhance path-tracking precision and handling stability. Wang Y. et al. [12] designed a hierarchical structure employing game-theoretic principles to improve lateral stability and path tracking under extreme conditions. Wang et al. [13] proposed a hierarchical framework integrating linear quadratic regulator (LQR) and SMC to enhance handling stability. Hang et al. [14] employed a hierarchical control structure based on optimal control theory to examine vehicle stability and robustness in extreme scenarios. Chen et al. [15] proposed a hierarchical framework that incorporates an adaptive LQR control strategy to optimize vehicle stability. Hang et al. [16] further extended hierarchical MPC to investigate active safety and robustness enhancement. In contrast, Sun et al. [17] implemented a decentralized dual sliding-mode controller to study lap-time optimization and path tracking for racing vehicles. Lai et al. [18] developed a decentralized framework combining nonlinear MPC (NMPC), dual PID control, optimal control, and SMC to maintain vehicle stability during emergency collision-avoidance maneuvers.

In recent years, predictive control and adaptive control have become research hotspots in the field of DDEV dynamics control, with nonlinear model predictive control (NMPC) and adaptive model predictive control (AMPC) being the most representative advanced methods, which have made remarkable progress in handling complex nonlinearities and parameter uncertainties [19,20,21]. NMPC has been widely studied for its ability to directly handle nonlinear dynamics and hard constraints. Bai et al. [19] propose an NMPC-based integrated longitudinal–lateral stability control strategy for DDEVs, which fully considers the nonlinear characteristics of tire force and suspension dynamics. Chu et al. [20] develop a fast iterative NMPC for autonomous high-speed overtaking of intelligent chassis, which improves computational efficiency by simplifying the nonlinear tire model. Wang et al. [21] propose a specific adaptive model predictive control strategy for path following of four-wheel independent drive automated vehicles, based on the real-time updating system model. The modified tube-based model predictive control method is applied to realize path following under the influence of the disturbance.

Nevertheless, existing research on integrated control of 4WS and DYC systems in DDEVs still presents several limitations. These limitations include insufficient model fidelity, inadequate estimation of critical vehicle states, overly coarse hierarchical design of controllers, and a lack of quantitative partitioning and weighting within integrated control frameworks. Simplified vehicle models are often adopted, and execution strategies are not fully optimized for specific control objectives. Furthermore, the coupling mechanisms between subsystems have not been thoroughly analyzed, and control regions have yet to be quantitatively defined.

To address these challenges, this study explores both independent and integrated control strategies for 4WS and DYC in DDEVs. The primary goal is to integrate their complementary strengths, alleviate conflicts from functional coupling, and ultimately enhance both low-speed maneuverability and high-speed handling stability. Specifically, a 4WS controller is developed based on SMC, in which robustness is enhanced through a switching function and a reaching law. In parallel, a hierarchical DYC framework is established, comprising an MPC-based upper layer controller and a lower-layer torque-allocation module optimized via an optimal tire utilization strategy. This structure enhances the logic of hierarchical control execution. The coupling mechanism between 4WS and DYC is analyzed, and the vehicle stability region is partitioned using a phase-plane method. An integrated control-allocation algorithm is then proposed to define control regions and corresponding weightings for both systems, enabling coordinated and balanced control between the two subsystems.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 gives a detailed construction method for a DDEV dynamics model. Section 3 illustrates the design process of the integrated 4WS and DYC controller. Simulation comparative analysis is provided to demonstrate the advantage of the proposed approach with different scenario tests in Section 4. Finally, conclusions and outlooks are discussed in Section 5.

2. Development of the Dynamics Model

2.1. Establishment of the Ideal 2-DOF Model

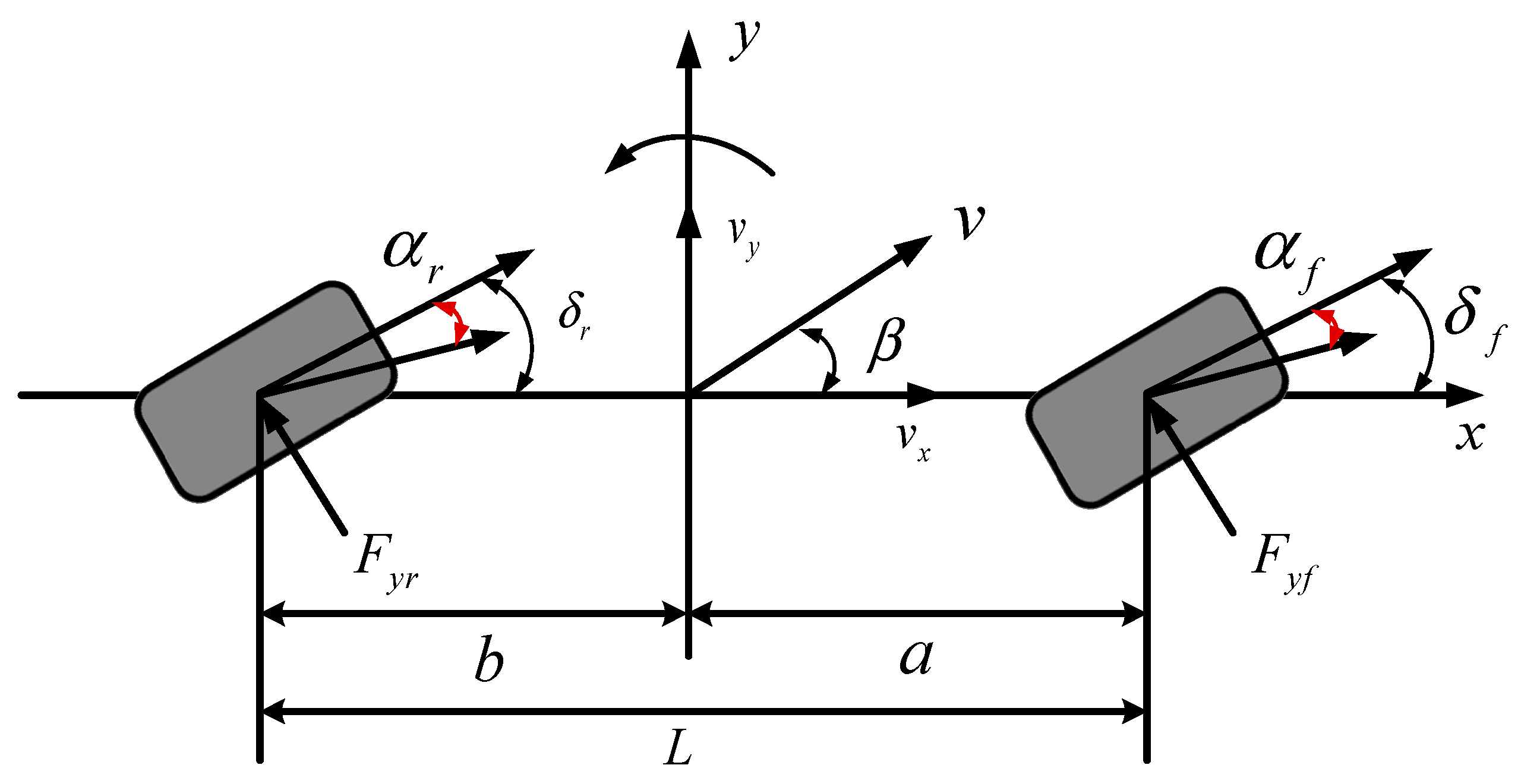

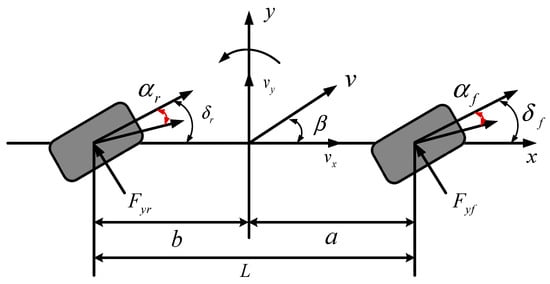

Based on the classical linear two-degree-of-freedom (2-DOF) vehicle dynamics framework, a linear 2-DOF 4WS coupled vehicle model is established by introducing the rear-wheel steering angle as an additional control input, as illustrated in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

Linear 2-DOF model of 4WS.

As shown in Figure 2, under the ISO 8855 standard [22] coordinate system, the linear 2-DOF 4WS vehicle dynamics equations are derived as follows:

When the vehicle is operating in a steady-state steering condition, both the front and rear-wheel steering angles and remain within limited amplitude ranges. Therefore, the small angle approximation may be applied, assuming .

Then, the front and rear-wheel slip angles are computed as follows:

where is yaw rate, and are the slip angle of the front and rear wheels, is sideslip angle.

By substituting Equation (2) into Equation (1), the following expression can be obtained:

In Equations (1)–(3), and represent the front and rear lateral deviation forces, and are the cornering stiffnesses of the front and rear wheels, and are the longitudinal and lateral speed.

The state variable is defined as , the input as , and the output as . Thus, Equation (3) is transformed into the state-space matrix representation below:

where , , , .

In the control strategy design of the 4WS system, a vehicle motion state evaluation system based on multiobjective optimization is constructed. The vehicle sideslip angle and the yaw rate are selected as the evaluation indicators for the vehicle motion state. The vehicle sideslip angle represents the degree of spatial consistency between the longitudinal direction of the vehicle and the velocity vector, and the yaw rate describes the vehicle’s rotational dynamics characteristics around the vertical axis. Therefore, to improve the vehicle’s stability and achieve accurate tracking of the desired driving trajectory, the vehicle should follow the motion law corresponding to the ideal yaw rate , while strictly controlling the vehicle sideslip angle within the minimum range [23]. Thus, the ideal vehicle sideslip angle is set to 0.

Under the steady-state response condition with , both the lateral velocity and the yaw rate become constant values (i.e., , ). The yaw rate at this instant is denoted as , which is given by:

where is a stability factor, .

In addition to considering the steady-state response conditions, it is also necessary to strictly satisfy the environmental constraints such as the road adhesion condition, that is, .

Therefore, the final formula of is:

2.2. Establishment of Full-Vehicle Model

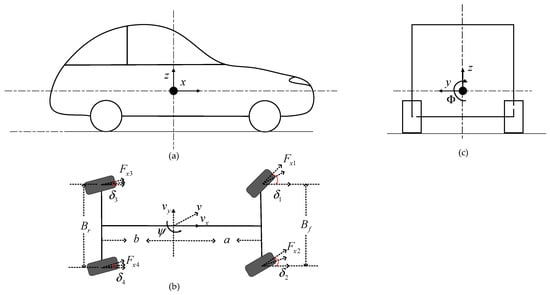

2.2.1. Establishment of 8-Degree-of-Freedom Model

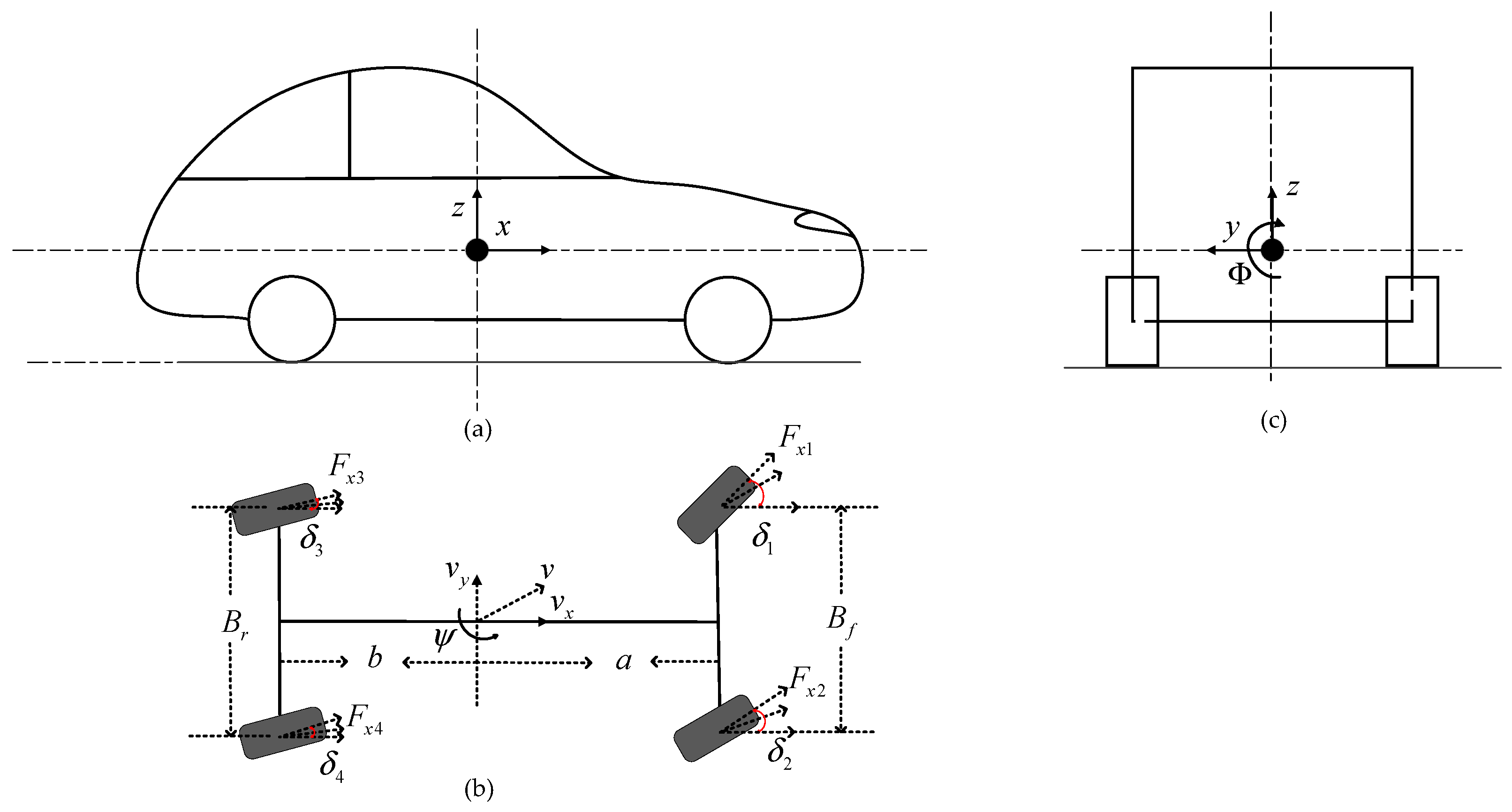

In this study, an 8-degree-of-freedom (8-DOF) vehicle dynamics model is established to derive critical vehicle state parameters. The model incorporates four primary degrees of freedom—longitudinal, lateral, yaw, and roll motions. Additionally, considering that the DDEV is equipped with four independently controlled in-wheel motors, a 4-DOF tire model is formulated to capture the independent rotational dynamics of each wheel. The diagram of 8-DOF model is shown in Figure 3, where represents the -th wheel, 1 and 2 represent the front-left and front-right wheels, and 3 and 4 correspond to the rear-left and rear-right wheels.

Figure 3.

The diagram of 8-DOF model. (a) Side view of 8-DOF, (b) lateral view of 8-DOF, (c) longitudinal view of 8-DOF.

Where is longitudinal tire force, is front and rear track width, is wheel angle, is yaw angle, is roll angle, is longitudinal axis, lateral axis and vertical axis, is distance from center of mass to front axle, is distance from center of mass to rear axle.

All vehicle dynamics equations are established in the standard body-fixed coordinate system (ISO 8855), with the origin at the center of gravity, x-axis pointing forward, y-axis to the left, and z-axis upward [24,25].

The differential equation for the longitudinal translation of the vehicle body is expressed as follows:

The differential equation for the lateral displacement of the vehicle body is given by:

The differential equation of yaw rotation of the car body is as follows.

The differential equation for governing the roll motion of the vehicle body is expressed as follows.

The notations in Equations (7)–(10) are summarized in Table 1. In this study, the general asphalt pavement is taken as the simulation pavement, is set to 0.015.

Table 1.

Symbol definition of DDEV.

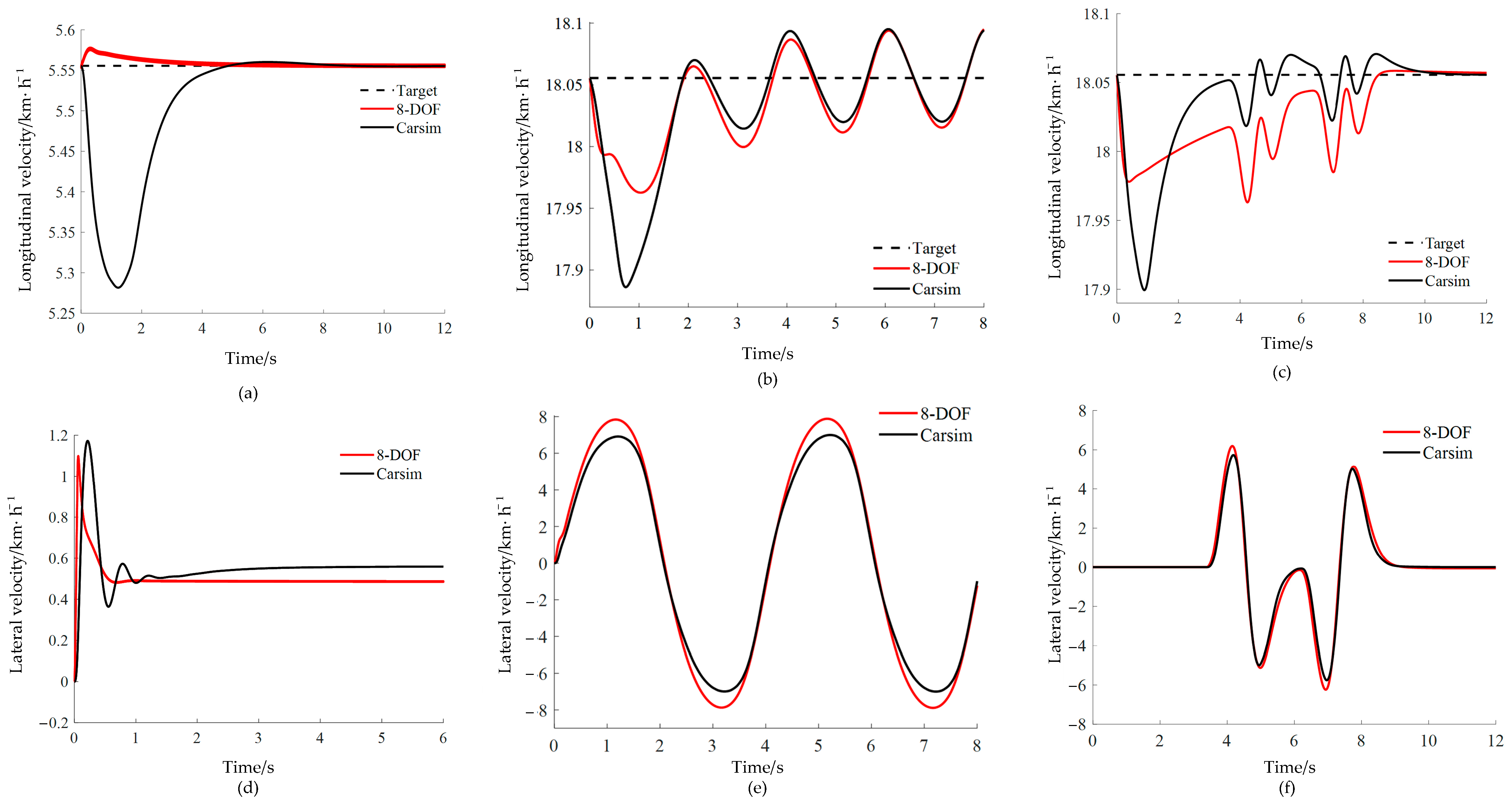

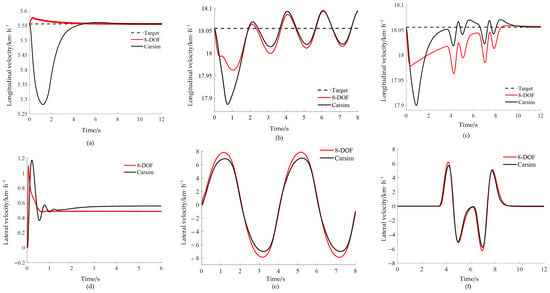

In order to verify the effectiveness of the 8-DOF model, the 8-DOF model is compared with the high-precision Carsim vehicle model. The dynamic response comparison between the 8-DOF model and Carsim model is conducted under three typical operating conditions—angular step (steering wheel angle 57.3°, target speed 20 km/h), angular sine (amplitude 90°, period 4 s, target vehicle speed 65 km/h (GB/T 6323-2014 [26])), and double lane change (target vehicle speed 65 km/h (GB/T 40521.1-2021 [27])), as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Verification diagrams of the 8-DOF model under angular step, angular sine, and double line change conditions. (a) Longitudinal velocity under angular step; (b) Longitudinal velocity under angular sine; (c) Longitudinal velocity under double lane change; (d) Lateral velocity under angular step; (e) Lateral velocity under angular sine; (f) Lateral velocity under double lane change.

As can be seen from Figure 4a–c, the constructed 8-DOF model exhibits a faster transient response. The 8-DOF model has a shorter longitudinal speed adjustment time, converges quickly to the target speed, and has a smaller overshoot. Figure 4d–f show that the lateral acceleration of the 8-DOF model exhibits dynamic characteristics consistent with those of the Carsim vehicle model in the time domain response, and the relative error in the steady-state phase is less than 10%.

2.2.2. Establishment of Tire Model

For the tire model, the dynamic equations of the four wheels during the driving process are given as:

The magic formula (MF) tire model features high parameter identification efficiency, simple mathematical representation, and accurate representation of tire dynamic response characteristics. The MF tire model with a composite sine function structure is selected to synchronously compute the time varying characteristics of tire longitudinal and lateral forces. The MF tire model uses three-dimensional input parameters, including longitudinal slip ratio, slip angle, and vertical load. Based on these inputs, the model calculates the longitudinal force, lateral force, and self-aligning torque as outputs. However, the self-aligning torque is not considered in Section 2.2.2 and is set to a default value of zero. The unified analytical expressions of the MF tire model are:

where denotes longitudinal force or lateral force, indicates longitudinal slip rate or sideslip angle, is the vertical offset, is the horizontal offset, D, C, B, and E are peak factor, shape factor, stiffness factor, and curvature factor, respectively, which can be derived by the fitting method.

When ignoring the horizontal and vertical drift of the curve, and are both set to zero. The lateral force under no longitudinal slip and the longitudinal force under no side slip are shown as follows:

where is vertical load, , are coefficients of , respectively.

is the normal pressure between the tire and the ground, and it is also the basis of tire adhesion capacity and directly determines the maximum peak value of tire force. Based on the tire model data of 215_55_R17 in the Carsim platform, the curve fitting tool of Matlab is used to directly fit the unknown parameters (D, C, B, and E) of the MF tire model. The fitting results of corresponding parameters under pure lateral deviation and pure longitudinal slip are shown in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. quantify the influence of on the nonlinear characteristics of tire force, correcting stiffness and peak values under different wheel loads to avoid errors caused by fixed parameters. describe the nonlinear growth law of tire force with longitudinal slip ratio or slip angle, determining the rising slope and saturation rate of the curve.

Table 2.

Fitting results of MF tire model parameters under pure lateral deviation.

Table 3.

Fitting results of MF tire model parameters under pure longitudinal slip.

Under real operating conditions, the tire is subjected to both longitudinal and lateral slip simultaneously, resulting in more complex situations. To improve the accuracy of the MF tire model, the longitudinal and lateral forces under combined slip conditions are derived from the cases of the pure longitudinal slip and lateral slip, as described below:

where is longitudinal slip quantity, , is lateral slip quantity, , is resultant theoretical slip, .

2.2.3. Establishment of In-Wheel Motor Model

The internal electromagnetic and electrical dynamics of the in-wheel motors are simplified and neglected. A second-order transfer function with calibrated motor parameters is adopted as an equivalent model to characterize the torque-tracking performance between the commanded torque and the actual motor output torque. The specific form and parameters are given in Equation (15).

where is target output torque of the motor, is actual output torque of the motor, represents damping ratio related to the characteristics of the motor, = 0.05.

3. Design of the Integrated 4WS and DYC Controller

The 4WS system offers significant advantages in stability control when tire lateral forces remain within their linear range. However, in the nonlinear region—when tire lateral forces saturate—its regulation capability becomes insufficient. Therefore, the DYC system must be engaged to cooperatively exploit tire longitudinal forces. According to the tire friction ellipse theory, longitudinal force saturation reduces the available lateral force reserve, posing a risk of lateral dynamic instability. Under such conditions, 4WS control should be disabled to avoid affecting vehicle stability. To fully utilize tire adhesion characteristics, a dynamic coordination mechanism between the two subsystems must be established.

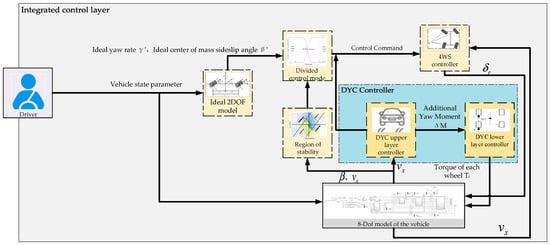

A hierarchical control architecture is adopted herein to balance the advantages of centralized and decentralized control and ensure independent subsystem operation. As shown in Figure 5, the integrated control framework systematically unites the core modules of 4WS and DYC into a multilayered control architecture. This architecture divides the control hierarchy into an information input layer, an intermediate controller layer, and an execution layer. Through the bidirectional exchange of critical information—including vehicle state sensing data (e.g., sideslip angle, yaw rate, and wheel load) from the information input layer, weighted control commands (for steering angle and yaw moment) from the intermediate controller layer, and real-time actuator feedback (e.g., actual wheel steering angle, motor output torque) from the execution layer—dynamic coordination between the 4WS and DYC subsystems is effectively achieved. This coordination specifically addresses the inherent longitudinal–lateral–yaw coupling characteristics of vehicle dynamics and ensures synchronized operation among multiple actuators (i.e., four-wheel steering mechanisms and distributed in-wheel motors), thereby meeting the requirements for precision, real-time performance, and robustness in multisubsystem cooperative control. This provides the necessary support for implementing the control strategy.

Figure 5.

Block diagram of integrated control system architecture.

3.1. Partition of the Stability Region

The phase-plane analysis method is employed to study the stability of nonlinear dynamical systems, and a stability evaluation system based on state parameters is constructed.

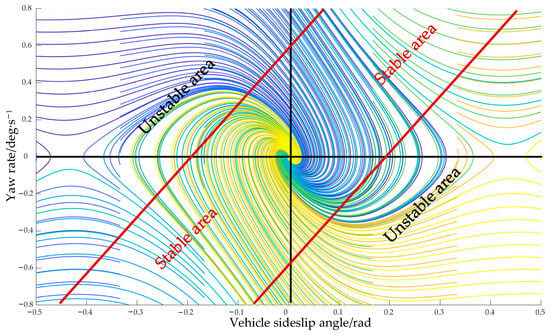

Currently, two typical phase-plane models are mainly applied: the phase plane and the phase plane. The yaw rate, as an initial characterization parameter for vehicle instability, has important monitoring value. However, in the phase plane, since the yaw rate is not used as a criterion for vehicle instability, this method cannot fully reflect the actual stability state of the vehicle. Moreover, under noncritical working conditions, the phase plane shows limited practicality.

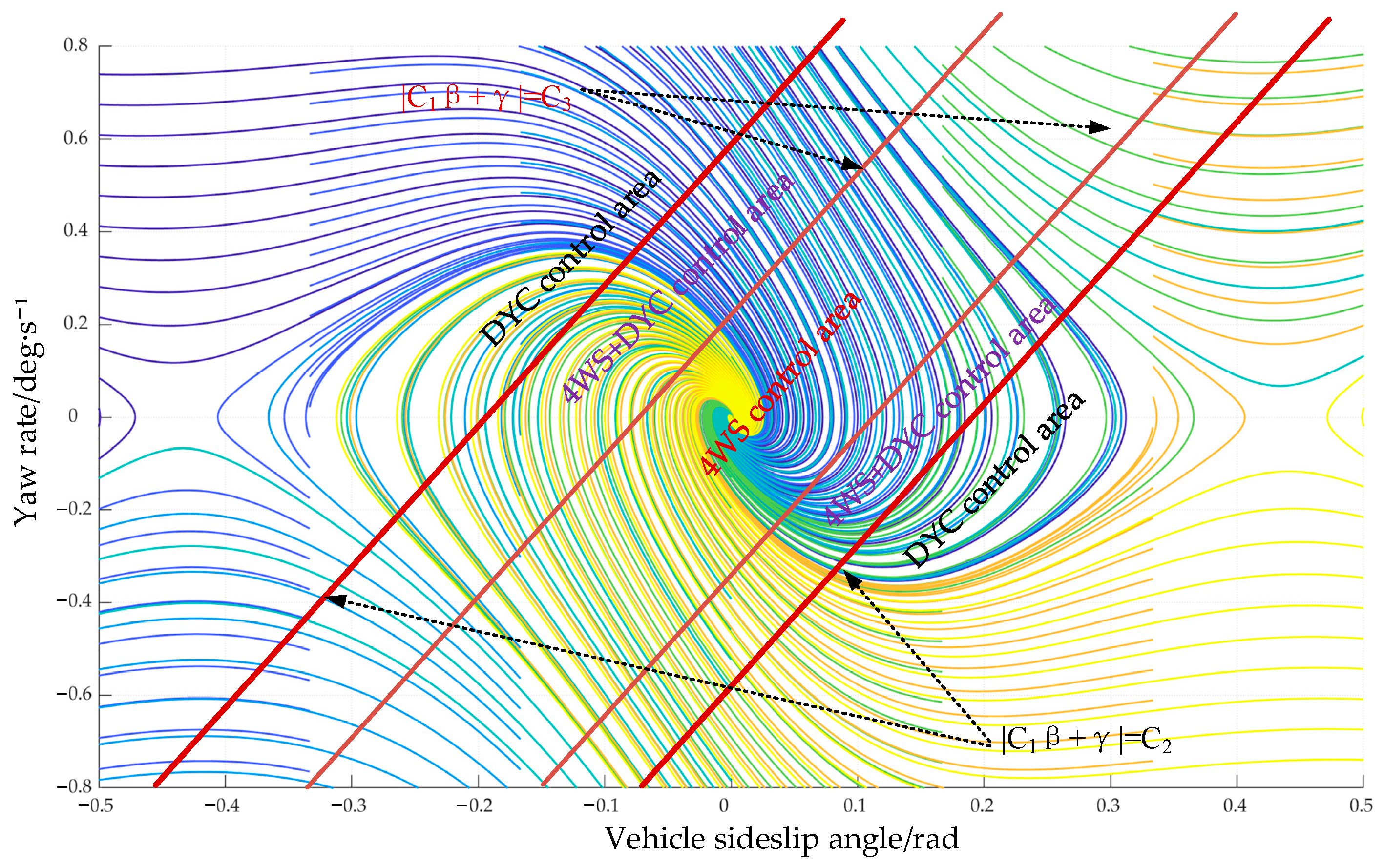

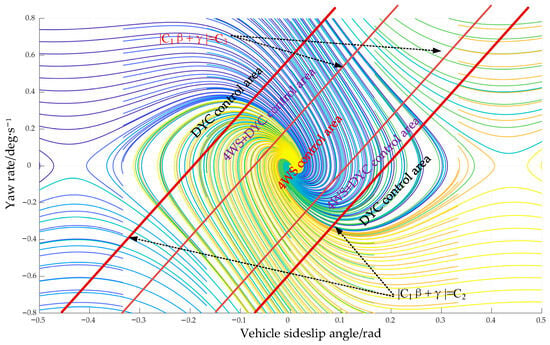

Therefore, considering the two state variables of the vehicle comprehensively, the phase plane is selected to establish a dual parameter cooperative criterion for accurate identification of the stability boundary, and the double line method is introduced to divide the stable region. The specific approach is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of phase plane.

Based on the phase plane, the phase-plane data of longitudinal dynamic parameters (vehicle speed) and tire–road interaction parameters (road adhesion coefficient) under various operating conditions and different initial vehicle states () can be obtained. The two boundary lines between two stable and unstable intervals are obtained in the phase plane, and the slope and absolute intercept of the two boundary lines are set as and , respectively. The distance between the two lines can be obtained through the simulation test.

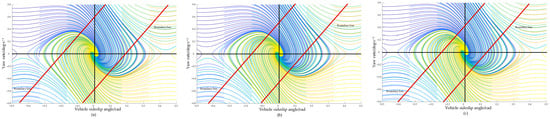

The road adhesion coefficient is defined as μ = 0.85, the given speed intervals are 20 km/h, 40 km/h, and 60 km/h, and the phase plane is painted at each interval of 20 km/h under different vehicle initial states. The stable region of the phase plane under different vehicle speeds is shown in Figure 7:

Figure 7.

The stability region of the phase plane at different vehicle speeds: (a) 20 km/h vehicle speed, (b) 40 km/h vehicle speed, (c) 60 km/h vehicle speed.

It can be seen from Figure 7 that, when the vehicle speed varies from 20 to 60 km/h, the boundary of the vehicle stability region is almost unchanged, and the vehicle speed has almost no influence on the boundary range of the phase-plane stability region. Taking = 60 km/h as an example, the parameters of the stability region under different road adhesion coefficients are displayed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Parameters of the stability region with different road adhesion coefficients.

Based on the slope and absolute intercept of the two boundary lines in Table 4 under different road adhesion coefficients, the calculation formula of distance S between the two lines is derived as follows:

Based on test data presented in Table 4, the mapping relationship between the slope and absolute intercept of the two boundary lines for the stability region, and the road friction coefficient , can be established via a fitting method as shown below:

3.2. Partition of the Integrated Control Mode

According to the control characteristics of the 4WS system and the DYC system, the lateral force of tires tends to saturation, and both front and rear wheels have steering angle limits due to mechanical structure constraints and tire physical properties. Specifically, the rear-wheel steering angle, as an additional control input of the 4WS system, usually has a stricter steering threshold to avoid exceeding the tire linear slip region. Moreover, the optimal working range of the 4WS system is in the region where the tire slip characteristics are linear. Therefore, to prevent the 4WS system from destabilizing the vehicle by forcing the tires into their nonlinear range or reaching steering limits, the control strategy is divided into three regions based on vehicle stability: the stable region (controlled by 4WS), the unstable region (controlled by DYC), and the transition region (coordinated control by 4WS + DYC).

The boundary equation between the 4WS + DYC and DYC regions, determined by the double line method, can be expressed as follows:

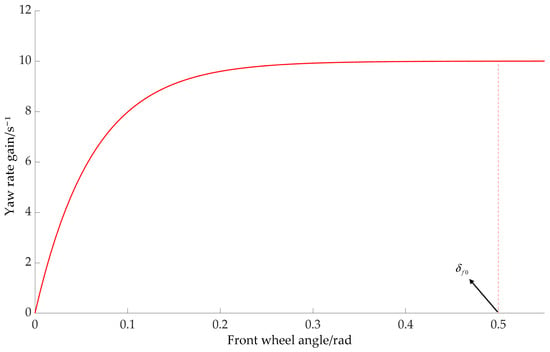

The boundary between the 4WS and 4WS + DYC regions is determined by the yaw rate gain. The relationship between the yaw rate gain and the front-wheel steering angle is , as shown in Figure 8. When is stable, it means that the lateral force of the tire is in the linear working area, and the 4WS system can achieve the expected stability control independently. When deviates from the stable value with the increase in the front-wheel steering angle, it indicates that the tire is approaching or entering the nonlinear zone, and 4WS control can no longer meet the demand.

Figure 8.

Relationship between and .

Based on the curve in Figure 8, the steering angle at which the yaw rate gain enters its steady state can be determined. This will enable the ideal 2-DOF model to accurately calculate the steady-state yaw rate , where is also the absolute intercept of the boundary between the 4WS and 4WS + DYC regions. Therefore, the boundary equation between the 4WS and 4WS + DYC regions can be expressed as follows:

The stable region in Figure 6 is redivided, and the partition of the obtained control regions is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Division of integrated control regions.

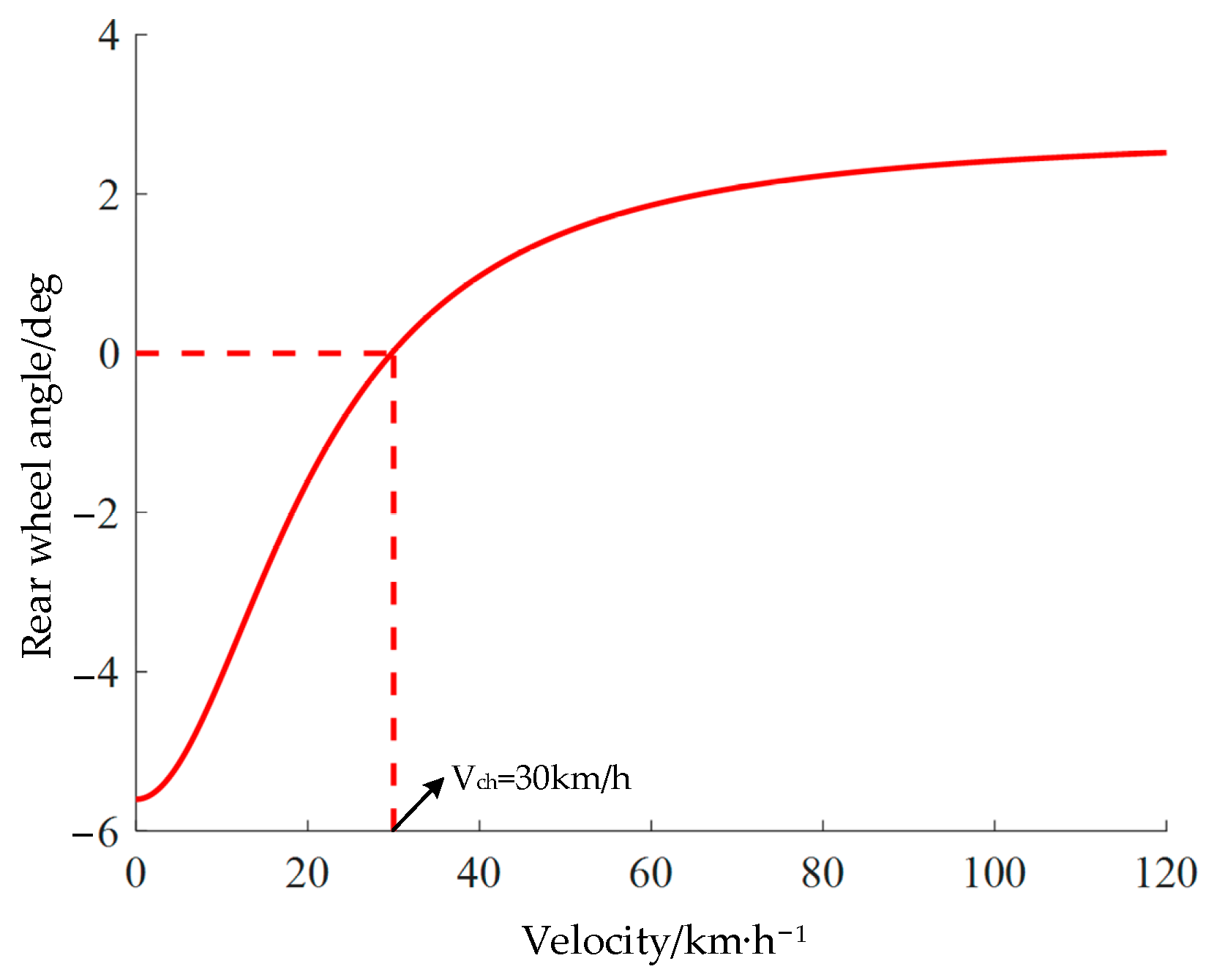

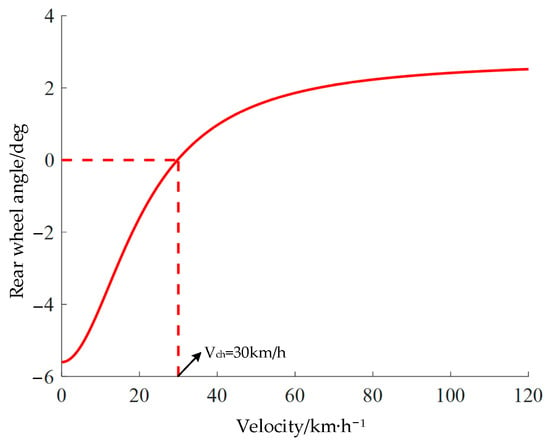

Based on the control region partitioning in Figure 9, it is necessary to develop reasonable switching rules for the integrated 4WS/DYC across different regions. Furthermore, within a single control region, a dynamic allocation of control weights between the 4WS and DYC systems must be achieved. To simultaneously achieve the objectives of low-speed maneuverability and high-speed stability for the vehicle, the formulation of switching rules and a control weight allocation scheme must consider the vehicle speed and control regions. When the actual vehicle speed is lower than the critical vehicle speed , the 4WS control strategy is adopted to improve the vehicle’s low-speed maneuverable performance. When the vehicle speed is higher than the critical vehicle speed , the cooperative control mode of 4WS and DYC is activated and the closed loop control of the vehicle’s dynamic stability is realized through the cooperative adjustment of torque distribution and rear-wheel steering angle. The critical vehicle speed is the speed threshold at which the 4WS system’s front- and rear-wheel steering angles switch from reverse deflection to same-direction deflection, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Curve diagram.

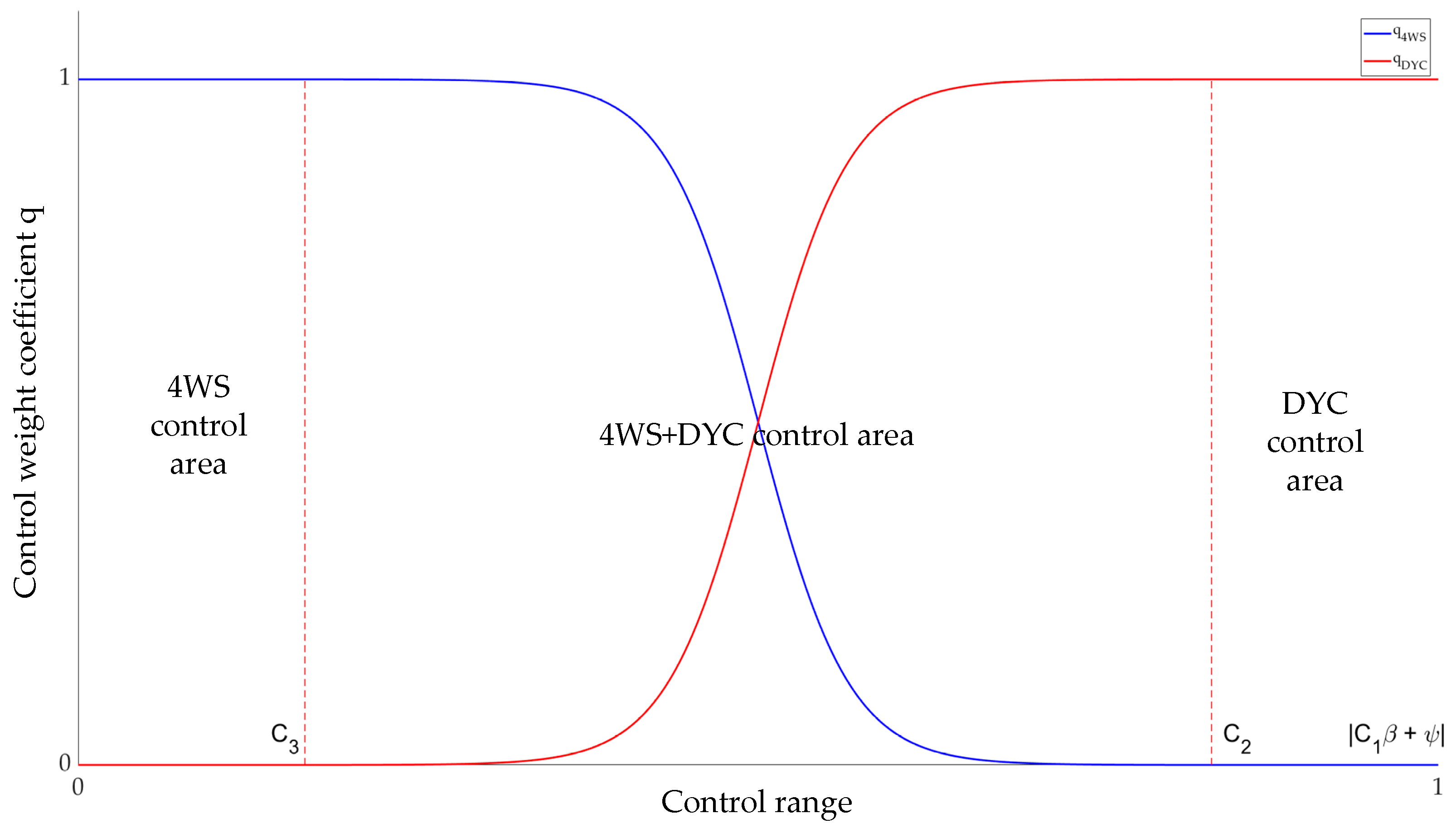

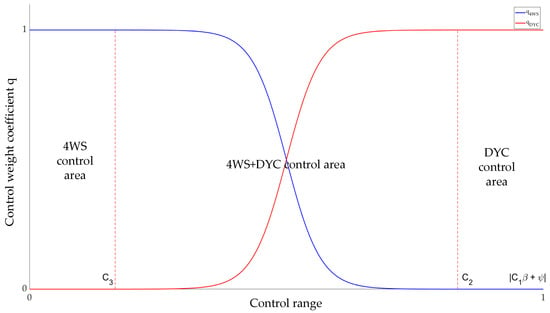

For the switching rules and control weights when the vehicle speed is higher than the critical vehicle speed , they are determined based on the control region corresponding to the vehicle’s current state. When the vehicle is in the 4WS control region, the control weight for 4WS and for DYC; when the vehicle is in the DYC region, the control weight for 4WS and for DYC; when the vehicle is in the 4WS + DYC region, the sigmoid function is used to redistribute the control weights of 4WS and DYC for joint control. The expression of the control weight is:

where is equal to the ratio of to , that is, . is related to , and . The control weight of 4WS is . The core role of is to regulate the change rate of in the transition region, and its value is usually between 4 and 8. In order to ensure stable parameters and smooth sigmoid function, is set to 4.

The weight curve when the vehicle speed is higher than the critical vehicle speed is shown in Figure 11:

Figure 11.

Relationship between weight coefficients and control intervals.

The switching rules and control weight allocation of the 4WS and DYC integrated controller are shown in Table 5:

Table 5.

Integrated control rules and weight allocation.

3.3. Design of 4WS Controller Based on Sliding Mode Control

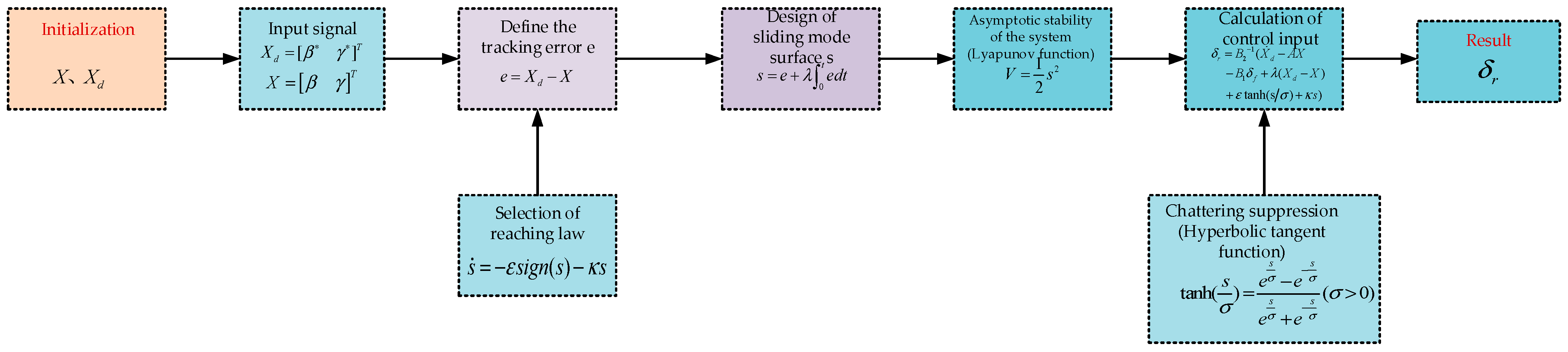

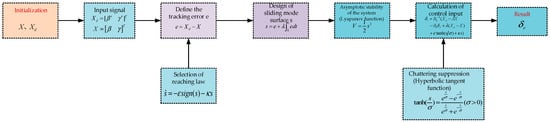

The 4WS system controller is designed following the process illustrated in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Design flowchart of 4WS system controller.

The dynamics of the ideal 2-DOF reference model are formulated in a state-space equation as:

where .

The tracking error can be defined as:

In Equation (22), , and the derivative of is obtained as:

A sliding surface is designed with an integral term to suppress the chattering problem caused by SMC:

The sliding surface in Equation (24) is derived, and the exponential reaching law is selected to reduce external disturbances:

To ensure the asymptotic stability of the proposed 4WS control system, a Lyapunov function is constructed based on Lyapunov stability theory:

The negative definiteness of is proven as follows:

where is the reaching law chattering suppression coefficient, is the reaching law speed coefficient, and is the sliding surface proportional coefficient.

With the aim of satisfying the negative definiteness of , , , and are strictly greater than zero. The particle swarm optimization (PSO) proposed by [28] is adopted to obtain the optimum , , and , and the objective function of PSO is defined as:

where is the simulation time horizon, and is a weighting factor which is usually set to 0.1 based on engineering experience. Considering the balance between the computational efficiency and accuracy, the key parameters of PSO are listed in Table 6 by combining empirical parameters with a trial-and-error method.

Table 6.

Key parameters of PSO.

Through iterative optimization, the , , and are defined as 0.2, 4.7, and 6.7, respectively. In order to further verify the effect of the main SMC parameters on control performance, a sensitivity analysis for , , and is conducted on high-adhesion pavement. As shown in Table 7, when , , and deviate from the optimum value within the range of ±20%, the max sideslip angle and max yaw rate error will also change accordingly. Thus, it is essential to optimize the main SMC parameters through optimization algorithms.

Table 7.

Sensitivity analysis of main SMC parameters.

By combining the above equations, the control input is obtained as:

To mitigate the chattering phenomenon induced by the discontinuous sign function, traditional methods typically replace the sign function with a saturation function. However, the saturation function itself still has nonsmooth characteristics, which may cause new high-frequency oscillation problems. For this reason, a hyperbolic tangent function with continuous differentiable characteristics is used to replace the saturation function and the sign function, and its mathematical expression is:

Equation (30) is substituted into Equation (29) to yield the final form of the control input :

3.4. DYC Hierarchical Controller Design

3.4.1. Design of DYC Upper Layer Controller Based on MPC

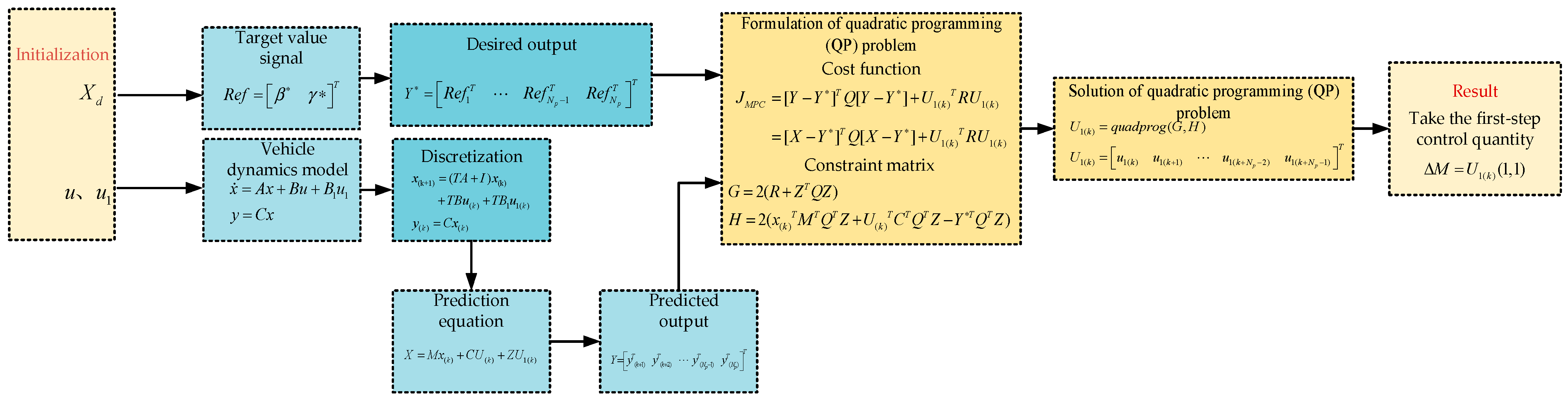

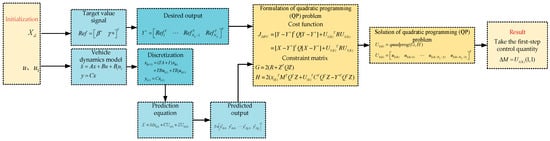

In the vehicle dynamics control architecture, decoupling the upper layer and lower layer controllers has important engineering significance. The additional yaw moment generated by the upper layer serves as a virtual control input and must be physically realized by the lower layer actuators. The lower layer controller achieves this target by dynamically adjusting the drive torque of each of the four wheels. Therefore, the upper layer and lower layer DYCs need to be designed respectively. The upper layer controller of the DYC system is designed using MPC theory, with the design process detailed in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Design flowchart of upper controller of DYC system.

By defining the state vector , the steering input , and the control input for additional yaw moment , the 2-DOF vehicle model can be rewritten in the following state-space representation:

where .

Equation (32) can be discretized using the forward Euler method as follows:

By introducing , , , , Equation (33) can be further simplified as:

By selecting the appropriate control and prediction time horizon, the discrete equation can be written in the form of a prediction equation as:

The control and prediction time horizon are both set to Np and the definitions of the matrices involved in Equation (35) are given below:

The reference vector Ref, comprising the desired sideslip angle and yaw rate, is defined as:

Assuming the reference signal Ref remains constant over the prediction horizon , the desired output is given by:

where , the prediction horizon is set equal to 10 to cover two time constants .

Since the output matrix is an identity matrix, the predicted output is equivalent to the predicted state :

To track the desired output , the optimal control input is obtained by minimizing the cost function , which is defined as:

The weights for the vehicle states and control inputs are represented by the matrices Q and R, which are specified as follows:

In practice, the elements of the weighting matrices = diag () and r are usually treated as constants to reduce the computational cost. The core function of the weighting matrices Q (state weight) and R (control input weight) is to balance the priority of multiobjective optimization. and are the weight of sideslip angle tracking error and yaw rate tracking error, respectively. and will affect the lateral stability and direction control accuracy when the vehicle turns. Based on engineering experience, and are defined as 2.98 and 1 by the trial-and-error method, respectively. r is the weight of the additional yaw moment , and it is defined as 0.15 [29]. Referring to the aforementioned sensitivity analysis of SMC parameters, the effect of the main MPC parameters on control performance is revealed by sensitivity analysis as described in Table 8.

Table 8.

Sensitivity analysis of main MPC parameters.

This strategy simplifies the optimization problem into a standard quadratic programming (QP) formulation.

During the simplification process, it can be considered that .

By assuming the control input (i.e., the steering angles) remains constant over the prediction horizon and neglecting irrelevant constant terms, the matrices G and H in Equation (40) are derived as:

For simplicity, explicit constraints on the additional yaw moment are omitted from the optimization problem, as defining their precise bounds is challenging. Instead, their physical limits are implicitly handled by the saturation of the actuators (e.g., wheel motors). The resulting unconstrained quadratic program is then solved to find the optimal control sequence :

According to the MPC theory, only the first term is taken as the additional yaw moment :

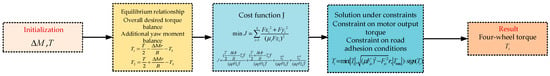

3.4.2. Design of DYC Lower Layer Controller Based on Optimal Tire Utilization

The upper layer controller generates an additional yaw moment based on the designed strategy, and the lower layer controller accordingly outputs accurate physical variables through the lower layer actuators. Therefore, the lower layer uses an optimal tire utilization method to distribute the required control effort among the individual wheel actuators.

Firstly, to keep the vehicle’s longitudinal speed stable, the sum of the torques of the four wheels should equal the total expected torque , and the following condition must be satisfied:

Secondly, the yaw moment generated by the differential torques of the four wheels must match the target yaw moment from the upper controller. This constraint is formulated as:

Since the wheelbases of the front and rear wheels are equal, and the influence of the wheel steering angle is ignored, Equation (45) can be simplified as:

The vertical tire load consists of a static component, dependent on vehicle mass and wheelbase, and a dynamic component, induced by longitudinal and lateral accelerations. Consequently, the total vertical tire force is calculated by summing these two components, expressed as:

where is the load transfer due to longitudinal acceleration, .

The vertical load on each wheel, , which is calculated using the load transfer Equation (47), also must satisfy the proportional relationship defined in Equation (48).

By combining the above equations, the expected torque of each wheel can be calculated as:

To fully utilize the adhesion potential of the tires, the optimal tire utilization rate distribution method is used to design the lower layer controller of the DYC system, as shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Design flowchart of lower controller of DYC system.

As illustrated in Figure 14, a complex nonlinear relationship exists between the tire’s longitudinal and lateral forces. To fully utilize the adhesion capacity of the four wheels, the concept of tire utilization rate is introduced:

The tire utilization ratio is a key parameter indicating how close a wheel is to its adhesion limit. A lower ratio represents a larger adhesion margin. Therefore, the optimization objective is to minimize the sum of the four wheels’ utilization ratios, which can be formulated as follows:

Since only longitudinal forces are considered here, the influence of lateral forces on the optimization result is ignored, and the objective function can be simplified as:

The relationship between longitudinal force and torque is given by:

Based on the torque distribution conditions in the equation above, the torque relationship can be obtained:

After substituting Equation (52) into Equations (53) and (54), the objective function is simplified to:

Since the quadratic terms for and have positive coefficients, and are set as the partial derivatives of with respect to and , respectively. The objective function achieves its minimum value when and are both zero. The calculations for and are:

By setting and , the solutions for and can be derived. Substituting these solutions into the aforementioned formulas yields and . Therefore, the four-wheel torque distribution results based on the optimal tire utilization rate strategy are given by Equation (57):

Since the torques of the four wheels after distribution are affected by the motor output torque and the tire friction ellipse, the torque of each wheel must also satisfy Equation (58):

Thus, the hierarchical DYC strategy is fully constructed. The upper MPC-based layer computes the total yaw moment required for vehicle stability, while the lower layer distributes this moment to the four drive wheels based on optimal tire utilization, thereby preserving tire adhesion margins. This integrated strategy enhances overall vehicle handling stability and safety.

4. Simulation Results and Discussion

To evaluate the performance of the proposed control strategy, a simulation platform is developed using MATLAB/Simulink 2020b. The proposed strategy is tested using a standard high-speed double lane change (DLC) maneuver on high- and low-adhesion surfaces. The major parameters of DDEV are shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

The major parameters of DDEV.

4.1. High-Speed High-Adhesion Double Lane Change Maneuver

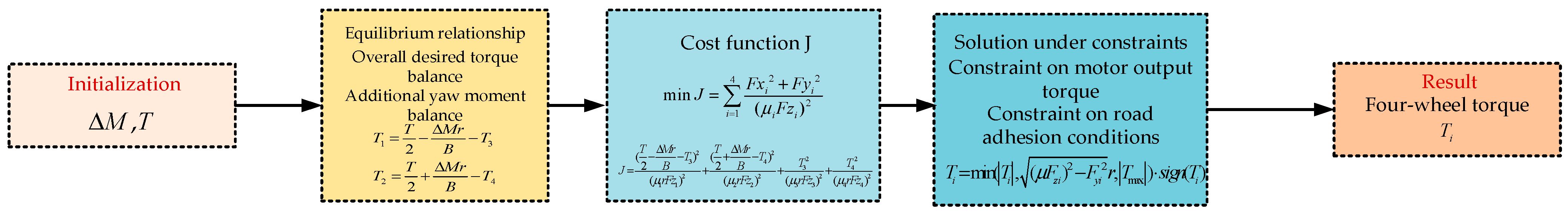

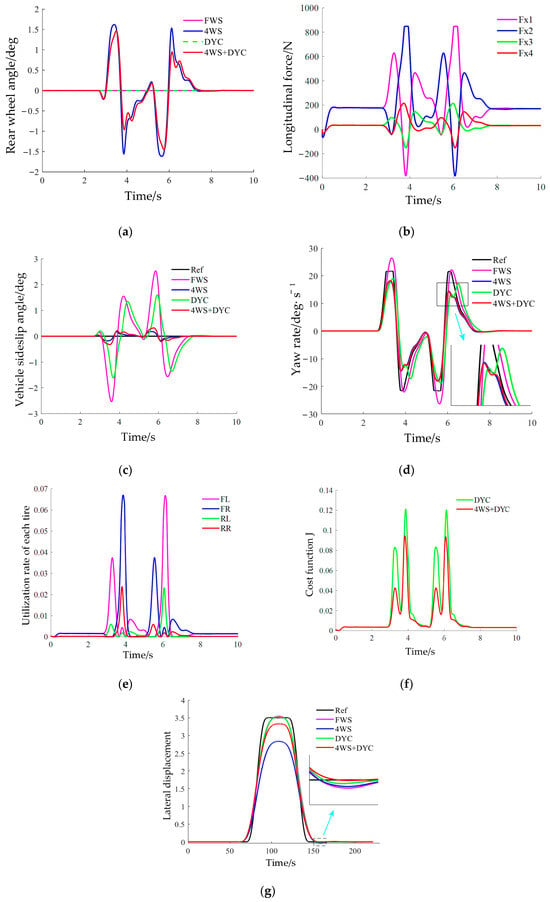

To evaluate the effect of road adhesion on vehicle stability, simulations were performed under high-adhesion (dry) and low-adhesion (slippery) conditions. In accordance with relevant standards, adhesion coefficients of 0.85 and 0.4 are used to represent dry and slippery road conditions, respectively. According to speed limit regulations of urban roads, on urban elevated roads, the maximum speed cannot exceed 80 km/h. Therefore, the vehicle speed is defined as 80 km/h during the simulation test. The particular test criteria are guided by ISO 15037-1: 2019 and ISO 3888-1:2018 standards [30,31]. The specific simulation results are shown in Figure 15, where FWS denotes front-wheel steering.

Figure 15.

Double lane change maneuver ( = 80 km/h, = 0.85). (a) Rear-wheel angle; (b) Tire longitudinal force; (c) Vehicle sideslip angle; (d) Yaw rate; (e) Utilization rate of each tire; (f) Cost function J; (g) Vehicle trajectory.

As shown in Figure 15a,b, the integrated 4WS + DYC is activated during the emergency lane change. Through coordinated operation of the two subsystems, the integrated control strategy demands smaller rear-wheel steering angles and lower additional yaw moments compared to scenarios where either subsystem operates independently. This finding is consistent with the weight allocation principle of integrated control schemes. Specifically, when the integrated control system intervenes during emergency lane changes, the maximum rear-wheel steering angle is reduced by 38.4% compared to the 4WS-only control configuration, thereby enhancing vehicle stability under high-speed conditions.

Figure 15c,d demonstrate that the integrated control system achieves the control targets for both vehicle sideslip angle and yaw rate. It overcomes the limitation of the DYC subsystem in sideslip angle suppression and ensures accurate tracking of vehicle sideslip angle and yaw rate to their target values. Under emergency lane change conditions, the maximum vehicle sideslip angle of the integrated control system is reduced by approximately 77.8% compared to the DYC-only control configuration, while showing 15.4% reduction from the 4WS-only control configuration. This confirms that the integrated control system avoids mutual interference between DYC and 4WS in regulating vehicle sideslip angle. Figure 15e,f further reveal that, in comparison to the DYC-only control configuration, the integrated strategy results in lower tire utilization rates and reduces the peak cost function by approximately 22.4%. This indicates that the integrated control system retains greater longitudinal force reserve capacity, enabling enhanced handling stability under more severe operating conditions.

Finally, the trajectory in Figure 15g shows that the 4WS subsystem in the integrated control system intervenes more moderately, exerting less influence on steering sensitivity than the 4WS system, which reduces lateral displacement errors during emergency lane changes and mitigates the degradation of obstacle avoidance performance observed in the 4WS system under high-speed conditions.

4.2. High-Speed Low-Adhesion Double Lane Change Maneuver

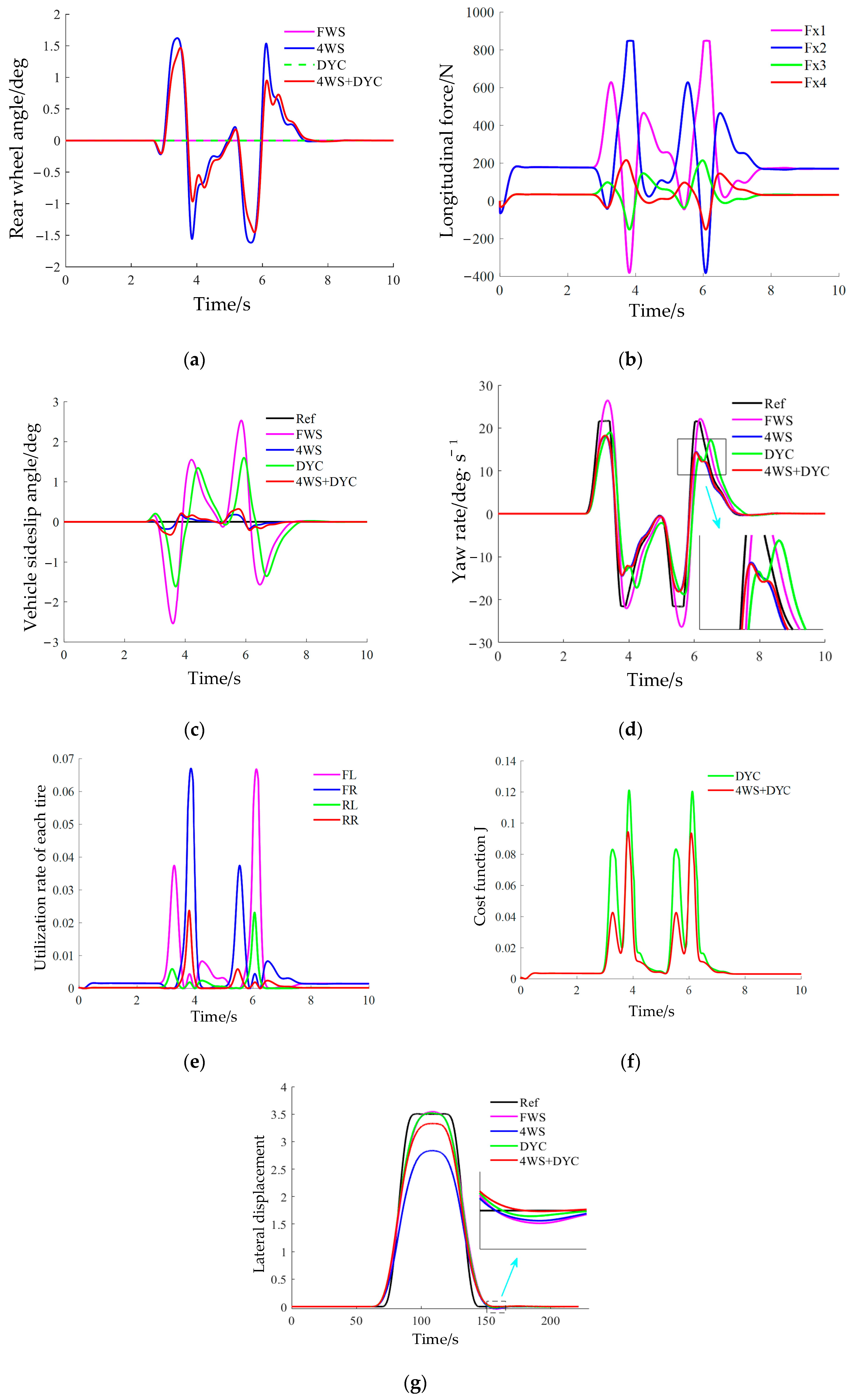

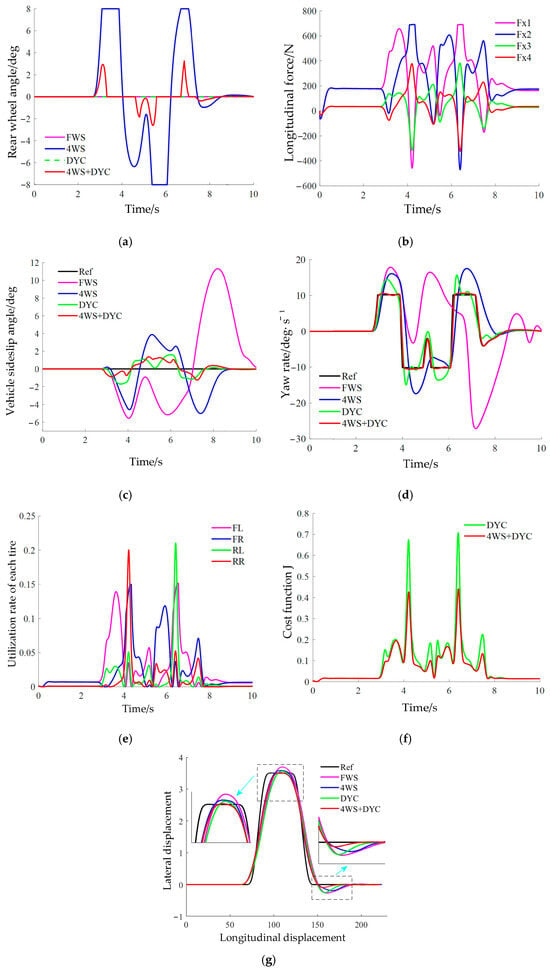

The adhesion coefficient of low adhesion road is selected as 0.4 and the vehicle speed is defined as 80 km/h. The specific results are presented in Figure 16:

Figure 16.

Double lane change maneuver ( = 80 km/h, = 0.4). (a) Rear-wheel angle; (b) Tire longitudinal force; (c) Vehicle sideslip angle; (d) Yaw rate; (e) Utilization rate of each tire; (f) Cost function J; (g) Vehicle trajectory.

As illustrated in Figure 16a,b, under the simulated DLC maneuver on low-adhesion road surfaces, the integrated control strategy dynamically switches between the 4WS + DYC domains and the DYC-only control domain. The minimal intervention of the 4WS subsystem—evidenced by the rear-wheel steering angle approaching zero during the maneuver—signifies that the vehicle has transitioned into the unstable operating regime (i.e., DYC-only control). During this phase, control authority is exclusively assumed by the DYC subsystem to mitigate the instability risk arising from inadequate lateral force reserves. On low-adhesion road surfaces, the integrated control strategy reduces tire longitudinal force compared to the DYC-only subsystem. Specifically, the rear-wheel steering angle of the integrated control system is reduced by approximately 60.2% relative to the 4WS-only control configuration, which confirms that DYC intervention can effectively enhance the stability of the rear-wheel steering system under low-adhesion conditions.

As depicted by the trajectory in Figure 16g and the parameter variation trends in Figure 16c,d, the integrated strategy maintains the vehicle sideslip angle β and yaw rate γ closer to their desired values, while simultaneously minimizing lateral displacement and enhancing vehicle stability. The maximum vehicle sideslip angle of the integrated control system is reduced by approximately 64.3% compared to the 4WS-only control configuration, while showing 21.1% reduction from the DYC-only control configuration. This effectively addresses two key limitations of standalone subsystems: the limited corrective capacity of the 4WS subsystem under low-adhesion conditions, and the excessive longitudinal force output by the DYC subsystem during emergency obstacle avoidance—thus substantially improving the vehicle’s controllability. Figure 16e,f further illustrate that, compared with the DYC-only control approach, the integration of the 4WS subsystem in the integrated strategy lowers the utilization ratio of tire longitudinal force. This preserves a larger reserve capacity for the DYC subsystem to fully leverage its control potential. In addition, the peak value of the cost function for the integrated control system is 37.6% lower than that of the DYC-only subsystem.

The simulation results demonstrate that, on high-adhesion road surfaces, the integrated control strategy can rapidly converge the sideslip angle into a safe range. Compared to DYC-only control which generates yaw moment solely through torque distribution, integrated control enhances alignment between the vehicle’s driving direction and velocity vector, thereby fundamentally reducing the risk of fishtailing on low-adhesion surfaces. Furthermore, the integrated control can reduce the maximum sideslip angle of the 4WS-only control (approximately 4°) to within 1.5°. In contrast to 4WS-only control, integrated control enables additional posture regulation through generated yaw moments, significantly improving vehicle stability on slippery roads. The reduction in required rear-wheel steering angle implies that rear-wheel adjustments are made only minimally when it is necessary, ensuring fast response, lowering actuator load, and avoiding destabilizing oscillations caused by over-steering. Moreover, optimization of the cost function reveals that the coordinated operation of both systems produces smoother control outputs than DYC-only control, effectively mitigating stability fluctuations arising from conflicting control objectives.

Performance comparisons between integrated control and 4WS-only control and DYC-only control under DLC are shown in Table 10 and Table 11, respectively:

Table 10.

Performance comparison between integrated control and 4WS-only control under DLC.

Table 11.

Performance comparison between integrated control and DYC-only control under DLC.

5. Conclusions

This study focuses on the coordinated control of 4WS and DYC in DDEVs. An integrated control strategy is developed based on phase-plane theory: a 4WS controller is designed via SMC with an optimized reaching law and hyperbolic tangent function for chattering suppression, while a hierarchical DYC system is constructed—featuring an MPC-based upper layer for additional yaw moment calculation and a lower layer for torque allocation using an optimal tire utilization scheme. By fusing the phase plane with vehicle speed parameters, a double line method is introduced for stability region partitioning. Simulation results verify the strategy’s efficacy, demonstrating that the proposed approach significantly enhances low-speed maneuverability and high-speed handling stability under both high- and low-adhesion conditions, thereby effectively addressing the limitations of single-system control. Specifically, under high-speed high-adhesion conditions, the integrated control system reduces the vehicle sideslip angle by 77.8% compared to DYC-only control and decreases the maximum rear-wheel steering angle by 38.4% and the cost function peak by 22.4% during DLC relative to 4WS-only control. Under high-speed low-adhesion conditions, the rear-wheel steering angle and cost function peak are further reduced by 60.2% and 37.6% compared to 4WS-only control, respectively. The maximum vehicle sideslip angle of the integrated control system is reduced by approximately 64.3% compared to the 4WS-only control configuration.

Future work will focus on verifying the real-time performance of the proposed method through actual test vehicles and exploring its adaptability across different vehicle configurations and the variation in slip angles and suspension kinematics between inner and outer wheels.

Author Contributions

T.X.: Methodology, Writing—review and editing, Writing—original draft. J.H.: Writing—review and editing, Funding acquisition. S.Z.: Writing—review and editing, Writing—original draft, Software. W.S.: Writing—review and editing, Software. P.Z.: Writing—review and editing, Supervision, Resources. Y.H.: Writing—review and editing, Supervision, Resources. G.S.: Writing—review and editing, Software, Validation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Technology Innovation Program of Hubei Province (2024BAB077), Guangxi Science and Technology Major Program (AA23062056), Guangxi Special Hired Expert Program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Yuanyi Huang and Tie Xu are affiliated with SAIC GM Wuling Automobile Co., Ltd., Liuzhou, China. The authors declare that these affiliations do not influence the results or interpretation of this study, and no conflict of interest exists regarding the publication of this manuscript.

References

- Zhang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Sun, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, L.; Chen, T.; Yuan, C. A Review of Coordinated Control Technology for Chassis of Distributed Drive Electric Vehicles. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuyama, E.; Yamakado, M.; Abe, M. A State-of-the-Art Review: Toward Novel Vehicle Dynamics Control Concept Taking the Driveline of Electric Vehicles into Account as Promising Control Actuators. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2021, 59, 976–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Chen, M.; Huang, Z.; Yu, X. A Review of Integrated Control Technologies for Four In-Wheel Motor Drive Electric Vehicle Chassis. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2025, 47, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cheng, S.; Li, S.; Zhao, W.; Wang, C. Lateral and Longitudinal Integrated Emergency Collision Avoidance System with Handling Stability Guarantee. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 4930–4940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, A.; Azadi, S.; Jazar, R.N. Integrated Control of Braking and Steering Systems to Improve Vehicle Stability Based on Optimal Wheel Slip Ratio Estimation. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2022, 44, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Ma, J.; Zhao, X.; Song, R.; Liu, X.; Wang, L. Coordinated Stability Control Strategy for Intelligent Electric Vehicles Using Vague Set Theory. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 6793821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Liang, J.; Tan, C.; Tian, Q.; Pi, D.; Yin, G. Enhancing Robust Driver Assistance Control in Distributed Drive Electric Vehicles through Integrated AFS and DYC Technology. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Luo, Y. Integrated Coordination Control for Distributed Drive Electric Vehicle Trajectory Tracking. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2020, 21, 1047–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; An, J.; Chen, Q.; Li, Y. Integrated Path Following and Lateral Stability Control of Distributed Drive Autonomous Unmanned Vehicle. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, D.; Hua, C.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Fixed-Time Sliding-Mode Lateral-Longitudinal Control for Vehicle Platoon with Strict Lane Constraints and Recoverable Spacing Policy. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 14854–14865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, C.; Guo, C.; Zhou, M. Coordinated Control of 4WS and DYC for In-Wheel Motor Driven Electric Vehicles. Automot. Eng. 2024, 46, 1766–1779. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, G.; Jiang, H.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, G.; Wang, C.; Zhao, W. Coordination Control for Path Tracking and Stability of 4WS 4WID Automated Vehicles: A Game Theory Based Approach. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 7392–7403. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Song, Q. The Control of Handling Stability for Four-Wheel Steering Distributed Drive Electric Vehicles Based on a Phase Plane Analysis. Machines 2024, 12, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, P.; Xia, X.; Chen, X. Handling Stability Advancement with 4WS and DYC Coordinated Control: A Gain Scheduled Robust Control Approach. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 3164–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Han, Y.; Hang, P. Research on 4WIS 4WID Stability with LQR Coordinated 4WS and DYC. In Advances in Dynamics of Vehicles on Roads and Tracks, Proceedings of the 26th Symposium of the International Association of Vehicle System Dynamics, IAVSD 2019, Gothenburg, Sweden, 12–16 August 2019; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1508–1516. [Google Scholar]

- Hang, P.; Xia, X.; Chen, G.; Chen, X. Active Safety Control of Automated Electric Vehicles at Driving Limits: A Tube Based MPC Approach. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2022, 8, 1338–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, R.; Lu, Z.; Tian, G. Lap Time Optimization and Path Following Control for 4WS & 4WID Autonomous Vehicles. SAE Int. J. Adv. Curr. Pract. Mobil. 2022, 4, 1678–1688. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, F.; Wang, X. Enhancing Autonomous Vehicle Stability through Pre-Emptive Braking Control for Emergency Collision Avoidance. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Wang, Y.; Jia, M.; Tan, X.; Zhou, L.; Chu, L.; Zhao, D. An NMPC Based Integrated Longitudinal and Lateral Vehicle Stability Control via Double Layer Torque Distribution. Sensors 2024, 24, 4137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, H.; Meng, D.; Huang, S.; Tian, M.; Zhang, J.; Gao, B.; Chen, H. Autonomous High-speed Overtaking of Intelligent Chassis Using Fast Iterative Model Predictive Control. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 10, 1244–1256. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, C.; Qie, T.; Ma, M. Adaptive Model Predictive Control-Based Path Following Control for Four-Wheel Independent Drive Automated Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 14399–14412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO8855:2011; Road Vehicles–Vehicle Dynamics and Road-holding Ability–Vocabulary. Swedish Standards Institute (SIS): Stockholm, Sweden, 2011.

- Liao, Z.L.; Shu, X.; Cai, L.C.; Zhang, L.Y. Research on Steering Stability Control Strategy of Four-Wheel Independent Electric Drive Special Vehicles. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 248, 2041. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Cao, D.; Du, H. Modeling, Dynamics and Control of Electrified Vehicles; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Limebeer, D.J.N.; Massaro, M. Dynamics and Optimal Control of Road Vehicles; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 6323-2014; Controllability and Stability Test Procedure for Automobile. State Administration for Market Regulation, Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China (SAMR, SAC): Beijing, China, 2014.

- GB/T 40521.1-2021; Passenger Cars Test Track for A Severe Lane-Change Manoeuvre—Part 1: Double Lane-Change. State Administration for Market Regulation, Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China (SAMR, SAC): Beijing, China, 2021.

- Zhou, Z.; He, Y.; Li, Y. MSF-PSO: A Multi-Strategy Particle Swarm Optimization Framework for Dedicated Highway Traffic Control of Small Passenger Vehicles. Informatica 2025, 49, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, P.; Zhu, C.; Hu, Y.; Chen, H. MPC-based Strategy for Longitudinal and Lateral Stabilization of a Vehicle under Extreme Conditions. Sci. China (Inf. Sci.) 2022, 65, 263–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO3888-2:2018; Passenger Cars—Test Track for A Severe Lane-Change Manoeuvre—Part 1: Double Lane-Change. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- ISO15037-1:2019; Road Vehicles—Vehicle Dynamics Test Methods—Part 1: General Conditions for Passenger Cars. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.