Featured Application

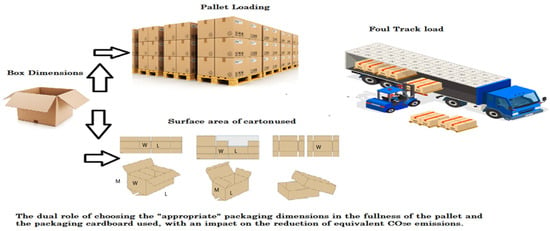

The proposed methodological framework is applicable across secondary and tertiary packaging configurations for bulk products. By systematically recalculating and optimizing package dimensions, the framework enables measurable reductions in the associated ecological footprint, particularly with respect to carbon dioxide emissions. These environmental gains arise from enhanced transport efficiency manifested in increased payload capacity per pallet and from the decreased consumption of corrugated cardboard required for packaging.

Abstract

Packaging is a fundamental component of food supply chains, enabling product protection, handling, and distribution from production to final consumption. In this context, the selection of secondary and tertiary packaging dimensions plays a critical role in improving logistics efficiency and reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions associated with material use and transportation. This study proposes a sustainable packaging logistics (SPL) framework that systematically evaluates and optimizes packaging carton dimensions to enhance pallet utilization, transport efficiency, and packaging material efficiency. The framework is applied to a real-world case study from a meat processing company, demonstrating how alternative carton dimension configurations, while maintaining a constant product weight and functional equivalence, can significantly influence pallet-loading efficiency, transported payload, and associated CO2-equivalent emissions. Rather than constituting a full life cycle assessment (LCA), the proposed approach adopts LCA-informed indicators to quantify material and transport related emission implications of packaging design choices. By integrating packaging design, palletization constraints, and logistics performance, the SPL framework provides a structured analytical basis for identifying packaging configurations that reduce material intensity and transport-related emissions. The results highlight the importance of packaging dimension optimization as a practical and scalable strategy for emission reduction in food supply chains. The proposed framework is intended to support decision-making in packaging design and to serve as a robust preparatory tool for future, more comprehensive LCA studies.

1. Introduction

Climate change pressures have led to investigations into food supply chains regarding their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Packaging, particularly the secondary and tertiary packaging used for grouping and transporting food products, plays a crucial role in modern supply chains. These packaging layers are essential components that can significantly influence the overall carbon footprint of food distribution. Secondary packaging, such as carton boxes that group food items, and tertiary packaging, including pallets, crates, and stretch wrap utilized for shipping, protect and secure products during handling and transit. Although these packaging layers do not come into direct contact with the food, they have a significant impact on logistics efficiency, material usage, and end-of-life waste, ultimately affecting CO2-equivalent (CO2 e) emissions.

In recent years, industry and academia have shown a growing interest in optimizing packaging to reduce environmental footprints, mainly motivated by corporate sustainability goals and regulations, thus aiming to reduce packaging waste and emissions [1] (pp. 614–627). Optimizing secondary and tertiary packaging offers a great opportunity to cut emissions without changing the food product itself. Improved packaging design can lead to lighter materials, better space utilization in transport, and higher recyclability or reusability, all contributing to lower CO2 e emissions [2] (p. 110). At the same time, packaging must still fulfill its primary functions: protecting food and preventing spoilage or damage. Inadequate packaging can lead to food loss–an outcome that could increase overall emissions by wasting the embedded resources in food [3] (pp. 11–14). Therefore, a balance is needed to minimize packaging-related emissions while preventing product waste, requiring a holistic, life-cycle perspective. Life cycle assessment (LCA) has become a standard method to quantify the environmental impacts of packaging choices across their lifespan. Recent studies have applied LCA to evaluate innovations like switching materials (e.g., plastic to cardboard), adopting reusable packaging systems [2] (p. 110) and optimizing package dimensions for transportation efficiency. These efforts provide a knowledge base to inform a global framework for sustainable packaging design. In summary, this article explores the sustainability of cardboard packaging redesign, analyzing its carbon footprint and presenting insights from a real-world case study in the Greek food industry.

2. Understanding the Role of Packaging in an Effective Supply Chain

There is an augmented demand to move goods worldwide due to economic and population growth as well as increasingly demanding consumer behavior. The need for packaging follows this growth because packaging facilitates the movement of goods, and apart from its main function, which is protection, it plays an important role in various logistics activities and their environmental performance [4] (p. 333). Moreover, as regulatory agencies and governments enforce environmental sustainability in companies, there is a build-up of pressure from customers and stakeholders for sustainable packaging design [5] (pp. 1699–1710). As a result, companies are impelled to make their supply chains greener. This is performed particularly by (1) minimizing their plastic consumption, and (2) reducing their carbon footprint (CF). As a result, more and more companies resort to the adoption of cardboard packages.

2.1. Overview of Corrugated Cardboard Packaging

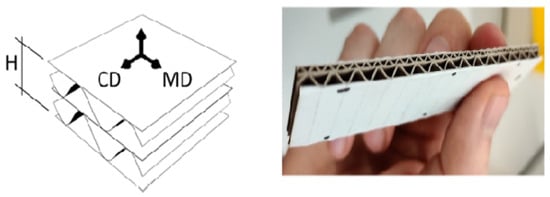

Nowadays, packaging is highly dependent on plastics, weighing a share of 44% of all the plastic produced in Europe in 2021 [6] (p. 22), all due to the combination of characteristics and versatility that are typical of this material. Corrugated cardboard is a packaging material composed of one or more layers of fluted paper (called “fluting”) sandwiched between flat linerboards, assembled typically using starch-based adhesives to form a lightweight yet strong structure suitable for packaging applications. The orientation of the fibers, shown in Figure 1, makes the corrugated board stronger along the direction of the wave.

Figure 1.

Geometrical configuration and material directions of multiwall corrugated board (left) and cross-sectional view of a multiwall corrugated board showing linerboards and fluting (right) (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/355034296_New_Edge_Crush_Test_Configuration_Enhanced_with_Full-Field_Strain_Measurements#fullTextFileContent, accessed on 7 January 2026).

It is valued for its high strength-to-weight ratio (its fluted structure provides rigidity to support heavy loads) and its affordability as a low-cost packaging medium. Its key advantages include biodegradability, recyclability, wide availability, and effective protective properties, making it a sustainable alternative to plastic in many logistics and retail contexts.

The lifecycle of corrugated cardboard begins with raw material sourcing, where fibers are derived from both virgin sources (mainly sustainably managed forests) and recycled paper, with recycled content reaching up to 82% for containerboard in Canada. During manufacturing, paper is processed into liner and fluting layers, shaped into boards through corrugation, and glued together in controlled conditions using water-based adhesives. In the usage phase, it is commonly used for transport packaging due to its protective strength, stack ability, and compatibility with various product types, although its weight can increase transport emissions compared to plastic alternatives in global supply chains. At the end of its life, corrugated cardboard is typically recycled up to seven times before fiber degradation limits further use. However, lamination, adhesives, and printing inks can hinder recyclability and lower pulp quality, prompting the need for better design-for-recycling practices.

2.2. Packaging Design Strategies (Dimension Optimization, Formats, Materials) Studied for CO2 e Reduction

Packaging plays a critical role in modern supply chains by protecting products and improving handling and transportation efficiency, but it also contributes significantly to environmental impacts such as greenhouse gas emissions (CO2 e) and solid waste generation. In Europe alone, approximately 81.5 million tons of packaging waste were generated in 2008, highlighting the magnitude of the sustainability challenge [1] (pp. 614–627). Growing environmental awareness and regulatory pressure have increased interest in sustainable packaging solutions that reduce carbon footprints and material waste while maintaining functional performance.

Recent research identifies key strategies for reducing packaging-related environmental impacts, including resizing and optimizing packaging dimensions, material substitution, lightweighting, and reuse or recycling. Poorly designed packaging can result in excessive material use, increasing emissions, or insufficient protection, leading to product losses and additional avoidable emissions. Several studies demonstrate that effective packaging design can significantly reduce emissions in food logistics by minimizing material use and improving transport efficiency.

Light-weighting and downsizing are among the most widely applied strategies. Reducing unnecessary material and void space lowers packaging mass and volume, leading to direct emission reductions from material production and indirect reductions from improved transport efficiency. For example, ref. [7] (pp. 2037–2047) reported that a 10% size reduction in rice snack packaging, combined with fewer printing colors, reduced package weight by approximately 10% and lowered the product carbon footprint. Similarly, ref. [8] (pp. 800–809) achieved an 11% reduction in CO2 e emissions per glass bottle by reducing bottle weight by 24%, with further reductions achieved through increased bottle volume and reuse. Switching from 0.75 L to 1.0 L bottles reduced emissions by 13% for disposable bottles and up to 39% for reusable bottles, while reuse over five cycles reduced emissions by 36%. Combined light weighting, reuse, and renewable electricity resulted in total emission reductions of up to 47%.

Packaging format selection also strongly influences environmental performance. A Finnish study showed that replacing glass bottles with alternatives such as Bag-in-Box (BiB), beverage cartons, PET bottles, and pouches yielded significant benefits, with BiB achieving the highest emission reductions [9] (pp. 768–780). In a mango supply chain, ref. [10] (p. 242) found that a 10% reduction in packaging weight resulted in a 9–10% reduction in overall environmental impact. Similarly, ref. [11] (p. 244) demonstrated that tailoring box dimensions to specific fruits and vegetables could reduce emissions by over 30% between the best- and worst-performing scenarios. Corrugated packaging redesign has also been shown to provide logistics and cost benefits while reducing CO2 emissions per delivered unit [12] (pp. 307–320). However, trade-offs remain, as highlighted by [13] (p. 117), who noted that lightweight materials may compromise durability, recycled plastics may reduce mechanical performance, and compact packaging often requires redesign and standardization.

Material substitution offers further emission reduction potential by replacing high-impact materials with lower-impact or reusable alternatives. Polypropylene has been shown to outperform single-use corrugated boards when reused multiple times due to its durability and lower cumulative impacts [14] (p. 822). Nevertheless, plastic packaging can incur higher end-of-life impacts related to recyclability and environmental leakage, particularly in regions with inadequate waste management systems [14] (p. 822).

Reusability and recyclability are critical determinants of packaging sustainability. According to [14] (p. 822), reusable polypropylene express boxes exhibit lower overall environmental impacts than single-use corrugated cartons when reused at least twice, although their benefits diminish with additional reuse due to cleaning-related water consumption. While corrugated cartons benefit from established recycling systems, they are associated with higher chemical oxygen demand and eutrophication impacts from pulp and paper processing. In contrast, polypropylene packaging shows lower freshwater ecotoxicity but higher primary energy demand due to polymer production.

In summary, integrating lightweighting, dimensional optimization, material substitution, reuse, and recycling can substantially reduce CO2 e emissions and broader environmental impacts. However, there remains a clear need for more empirical LCA data on packaging characteristics such as shape, weight, and material type, which are often insufficiently represented in food LCA studies. Improved data availability would significantly support LCA practitioners and enhance the robustness of sustainability assessments [15,16].

2.3. Impacts of Packaging Redesign on Logistics and Supply Chain Efficiency

Optimizing packaging in the food industry has a direct impact on logistics efficiency, influencing storage, handling, and transportation performance, and consequently affecting supply chain CO2 emissions. Efficient packaging improves cubic utilization of transport units, allowing more products to be shipped per pallet or vehicle, reducing shipment frequency, fuel consumption, and associated emissions. In contrast, poorly designed or oversized packaging leads to unused space, unnecessary trips, or increased use of protective fillers, undermining both economic and environmental performance.

A key factor in logistics optimization is the standardization of secondary packaging dimensions to improve palletization and container loading efficiency. Aligning carton dimensions with pallet footprints and container constraints maximizes volumetric utilization and minimizes overhang and void space. Packaging optimization also reduces the need for additional protective materials, which are often required when packaging is oversized relative to its contents, thereby increasing material use and emissions during production.

Several studies report significant logistics efficiency gains from packaging redesign. For example, wine packaged in glass bottles transported over long distances exhibits high CO2 e emissions, particularly when heavy bottles are used, whereas bulk packaging significantly reduces transport weight and freight emissions; however, bottling at the destination increases energy demand [9] (pp. 768–780). According to [11] (p. 244), larger boxes with higher fill rates reduced the number of required transport trips, while refrigeration energy and partial truckloads were identified as the main contributors to transport-related emissions. In Greece, ref. [17] (pp. 590–599) showed that optimizing corrugated box design reduced transport weight, fuel consumption, and CO2 emissions, while also lowering storage costs and palletization errors, achieving cost savings of up to 35% per box. Similarly, redesigning secondary corrugated packaging increased pallet density, reduced packaging costs, and improved vehicle utilization [12] (pp. 307–320).

Packaging redesign has also been shown to enhance load efficiency in fresh produce logistics. For example, ref. [1] (pp. 614–627) optimized packaging for Luochuan apples, increasing the transported quantities by up to 10.106 units compared to standard packaging, while improving pallet fit and reducing unused space. The use of dual-purpose packaging for both transport and retail further reduced handling complexity.

Although some studies do not directly address packaging optimization, they highlight transport-related factors that indirectly influence packaging decisions. The study by [18] (pp. 2601–2618) emphasized that transport mode, energy source, and load handling significantly affect emissions, suggesting that tertiary packaging design plays an important indirect role. Shifting from road to combined road–rail transport can reduce CO2 emissions by up to 6.3% with a 10% modal shift, while electric trucks can achieve approximately 20% energy savings [4] (p. 333). Additionally, ref. [16] (pp. 649–661) demonstrated that improved truckload utilization and routing performance reduced CO2 e emissions by 9–10% per cubic meter and reduced fleet requirements from four to three trucks per scenario.

Further evidence confirms the link between packaging design and transport efficiency. According to [19] (pp. 11–13), lightweight and compact packaging increases vehicle fill rates and reduces the number of trips, while secondary and tertiary packaging—though often contributing less than 10% to total emissions—remain underreported in LCA studies. The authors therefore recommend the development of more holistic and standardized LCA frameworks. Similarly, ref. [20] (pp. 687–692) showed that optimizing transport unit fill rates through improved bin arrangement increased average fill ratios from 55% to 71%, reducing unnecessary transport activity. Finally, ref. [21] (p. 4921) emphasized that efficient packaging reduces logistics and warehousing costs and supports material reduction, while also identifying challenges related to performance trade-offs, stakeholder coordination, and variability in recycling infrastructure.

Overall, the literature consistently demonstrates that packaging optimization directly translates into improved logistics efficiency and reduced transport-related CO2 emissions.

2.4. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) for Assessing Packaging Design

Life cycle assessment (LCA) is a widely established method for quantifying the environmental impacts of packaging decisions across their life cycle. Recent studies have applied LCA to assess packaging innovations such as material substitution (e.g., plastic to cardboard), the adoption of reusable packaging systems [2] (p. 110), and the optimization of packaging dimensions to improve transport efficiency [22] (p. 1870).

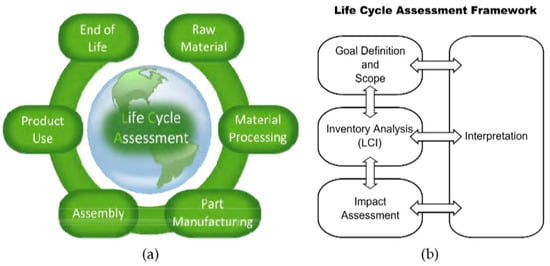

Within LCA, (please see Figure 2), the definition of system boundaries is critical for ensuring accurate impact assessment. The cradle-to-gate approach evaluates impacts from raw material extraction through manufacturing, ending at the factory gate before distribution or use. In contrast, the cradle-to-grave approach considers the full life cycle, including distribution, use, and end-of-life treatment, providing a more comprehensive environmental profile. An extension of this concept is the cradle-to-cradle model, which replaces disposal with recycling or upcycling processes, enabling materials to re-enter production cycles. This approach supports circular economy principles by enhancing resource efficiency and reducing waste through closed-loop systems [23] (p. 96).

Figure 2.

(a) Cradle-to grave life cycle assessment and (b) LCA framework according to ISO standards 14040 and 14044 (International Organization for Standardization 2006) (PDF) Life Cycle Assessment of Organic Photovoltaics. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/221929088_Life_Cycle_Assessment_of_Organic_Photovoltaics#fullTextFileContent (accessed on 7 January 2026).

Life cycle assessment (LCA) is widely used to quantify carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2 e) emissions associated with packaging systems across their full life cycle, including raw material extraction, manufacturing, transportation, use, and end-of-life management. End-of-life scenarios may include reuse, recycling, or final disposal. In food packaging LCAs, functional units vary: some studies adopt a “per kg of food delivered” basis, linking packaging impacts to transport service [24] (pp. 1899–1915), while others use a “per packaging unit over its lifetime” approach, such as CO2 e per use of a reusable crate [25] (p. 7). Both approaches are informative, capturing either the service function of packaging or its efficiency over multiple reuse cycles.

Recent LCA studies provide quantitative insights into packaging-related emissions. They consistently show that (i) material production impacts are important, but transport emissions can be equally or more significant for secondary and tertiary packaging; (ii) lightweight and compact packaging generally reduces CO2 e when functional requirements are met; and (iii) results are highly sensitive to assumptions regarding reuse rates, recycling scenarios, and system boundaries [19] (pp. 11–13), [24] (pp. 1899–1915). End-of-life treatment can significantly alter net emissions depending on whether packaging is recycled, landfilled, composted, or energy-recovered, although these aspects are considered out of scope for the present study.

Several product-specific LCAs highlight packaging as a major emissions contributor. In the mango supply chain in India, ref. [10] (p. 242) identified packaging and cultivation as the dominant environmental hotspots, with packaging contributing approximately 36% of the total global warming potential. In a cradle-to-grave LCA of pizza production, ref. [26] (pp. 106–119) found that packaging accounted for 9.6% of the total greenhouse gas emissions for takeaway pizzas, while ingredients dominated overall impacts. Using ISO 14067:2018, ref. [11] (p. 244) reported that cardboard box manufacturing accounted for 75–85% of the total CO2 e emissions, transport for 7–17%, and end-of-life for less than 4%, emphasizing the importance of packaging efficiency and transport distance. Similarly, ref. [27] (pp. 753–766) compared distribution crates made of plastic, corrugated cardboard, and wood, showing that transport and manufacturing dominated emissions, and that multi-use plastic crates performed best when supported by sufficient reuse cycles, while wood crates benefited from renewability and reuse potential.

Including transport and distribution stages is particularly critical for secondary and tertiary packaging LCAs. For example, ref. [28] (p. 106871) showed that corrugated cardboard cushioning inserts had higher CO2 e emissions than plastic alternatives in global B2B transport due to increased weight and volume, especially in air freight. This highlights the importance of evaluating material substitutions through LCA, as increased transport emissions can offset gains from using ostensibly more sustainable materials.

Logistics-related studies further reinforce the link between packaging efficiency and emissions. Although not directly focused on packaging, ref. [29] (pp. 121–130) demonstrated that improved palletizing and space utilization can reduce transport costs by up to 30% and storage costs by 25%, while also lowering CO2 e emissions from fuel and energy use.

Despite this evidence, several authors note that the indirect environmental impacts of packaging are insufficiently addressed in food LCAs. According to [30] (pp. 37–50), secondary and tertiary packaging are often excluded or insufficiently analyzed, and scenario or sensitivity analyses addressing transport efficiency and food waste are rare. Similarly, ref. [21] (p. 4921) highlighted the lack of standardized methodologies and holistic supply chain perspectives, while ref. [20] (p. 3336) emphasized that improvements in load efficiency directly translate into reduced fuel consumption, vehicle usage, and logistics-related emissions.

Overall, the recent LCA literature underscores the need for a systems-based approach to packaging assessment, recognizing packaging not only as a material input but as an enabler of logistics efficiency and waste reduction. Expanding system boundaries and incorporating indirect effects and scenario analysis are essential for robust evaluations of sustainable packaging solutions in food supply chains.

3. Proposed Framework and Implementation for Sustainable Packaging Logistics

This study evaluates the influence of secondary and tertiary packaging design on logistics efficiency and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions using a life cycle assessment (LCA) approach. The framework focuses on how carton type selection and dimensional optimization affect pallet utilization, packaging material demand, and transport efficiency, ultimately influencing total CO2-equivalent (CO2 e) emissions. The methodology is applied and validated through a representative transportation case study. The framework is generic and applicable to all bulk product categories.

Goal and Scope Definition

The goal of the LCA is to quantify potential reductions in CO2 e emissions achieved through optimized packaging dimensions and carton type selection. The functional unit is defined as the transportation of an equal mass of bulk product packaged in secondary cartons and transported via palletized full truckload distribution.

The system boundaries include the following:

- Production of corrugated carton packaging (secondary packaging),

- Palletization and load unit formation (tertiary packaging),

- Road transportation of palletized goods.

Primary product production and end-of-life treatment of packaging materials are excluded from the system boundaries and are assumed to remain constant across all scenarios.

Step 1: Inventory Modeling of Alternative Packaging Dimensions

A computational recalculation of feasible alternative secondary packaging dimensions is performed within the Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) phase. The alternative dimensions are constrained by pallet base dimensions and maximum allowable pallet height. All candidate configurations enclose an identical bulk product volume (within statistically acceptable tolerances), ensuring functional equivalence across scenarios.

The resulting dimensional configurations are considered functionally equivalent packaging alternatives, and are therefore directly comparable within the LCA framework.

Step 2: Palletization Efficiency and Transport Load Optimization

All alternative packaging configurations derived in Step 1 maintain equal product mass per unit. However, improved pallet volume utilization is achieved, resulting in increased transported payload per pallet and per vehicle. This affects the transport-related inventory flows by reducing the fuel consumption per functional unit, thereby lowering transport-related CO2 e emissions.

Step 3: Carton Type Selection and Packaging Material Inventory

For each set of alternative packaging dimensions, a carton type is selected that meets mechanical, logistical, and commercial requirements. Standard corrugated carton designs, including slotted, folder, and telescope cartons, are evaluated without limiting the general applicability of the method.

Within the LCI, carton surface area is used as a proxy for carton material consumption. Among all feasible carton type dimension combinations, the configuration that minimizes carton material input is selected as optimal.

Step 4: Life Cycle Impact Assessment of CO2-Equivalent Emissions

Using the optimized packaging configurations, a Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) is conducted with a focus on the global warming potential (GWP) indicator, expressed in CO2 e.

Two main impact pathways are evaluated:

Firstly, packaging-material-related emissions are evaluated, driven by corrugated board production and dependent on carton surface area, board grade, number of layers, and recycled content.

Secondly, transport-related emissions are also evaluated, driven by fuel consumption per transported mass, vehicle payload utilization, fuel type, transport distance, and the proportion of partially loaded trips.

By increasing payload efficiency and reducing carton material demand, the optimized packaging configurations achieve a net reduction in total CO2 e emissions per functional unit.

Interpretation and Dual Optimization Objective

The proposed LCA-based framework serves a dual optimization objective:

- Minimization of corrugated carton material consumption per functional unit;

- Minimization of transport-related CO2 e emissions through improved load utilization.

All alternative packaging configurations are functionally equivalent with respect to delivered product volume per kilogram and pallet filling degree. Differences in environmental performance therefore arise solely from variations in packaging material inputs and transport efficiency.

The results demonstrate that CO2 e emissions associated with corrugated carton production are significantly higher per unit than emissions attributable to fuel consumption per individual carton. Consequently, packaging material optimization constitutes the dominant emission reduction pathway within the assessed system.

Finally, the overall environmental performance is influenced by key LCA parameters, including transport distance, vehicle capacity, fuel type, backhaul utilization, carton weight, board composition, and recycled content, all of which are explicitly considered within the inventory modeling.

3.1. The Problem of Palletizing

Secondary packaging, which determines the external dimensions of a package before it is placed on a pallet, is often not a primary concern in the production planning process of industrial units. Instead, packaging box selection is typically based on empirical methods to ensure compatibility with the final product’s dimensions. However, when a product has specific size and weight requirements, the choice of packaging is optimized to maximize its efficiency. Examples of such products include bicycles, hair dryers, and shoes. For bulk products, packaging selection is primarily driven by achieving a predetermined weight per unit sold, such as 5 kg, 10 kg, 12.5 kg, or 20 kg packages. In this discussion, we will focus on these bulk agri-food products, which offer flexibility in their arrangement within the packaging without the risk of deformation ([22] (p. 1870).

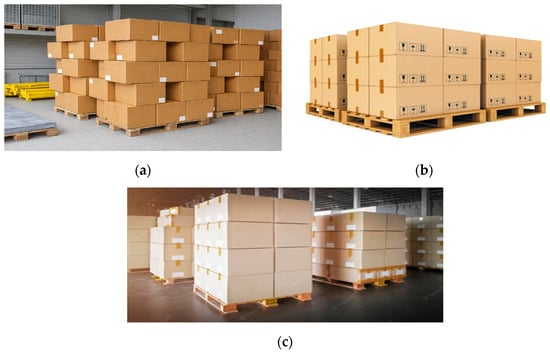

The unscientific and empirical approach to determining packaging box dimensions often results in computational complexities when solving pallet loading problems, (please see Figure 3), whether for manufacturers (MPLP) or distributors (DPLP). Additionally, during temporary storage on pallets in warehouses (PLP), workers often arrange boxes based on convenience rather than following a structured plan [31] (p. 231). This lack of organization leads to common practical issues, such as the following:

Figure 3.

Possible problems of placing the boxes on the pallet (a,b) and the ideal dimensions of boxes for optimal placement on a pallet (c), [32] (pp. 1474–1481).

- ▪ Boxes extending beyond the pallet’s edges, making them difficult to manage during storage and transport.

- ▪ Uncovered surfaces, which can cause stability issues due to a high center of gravity [32] (pp. 2601–2618).

- ▪ Inefficient use of pallet volume, leading to suboptimal fullness.

- ▪ Difficulty in counting and tracking packed boxes.

Despite these challenges, limited research has been conducted on the consequences of poorly chosen packaging dimensions and their impact on logistics and storage efficiency [32] (pp. 1474–1481).

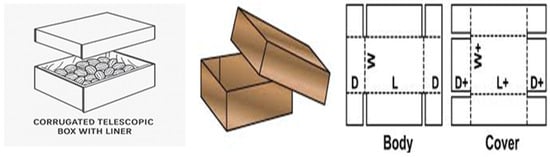

3.2. Box (Carton) Selection

Based on an expanded methodological approach, we recalculate the box dimensions as submultiples of the pallet dimensions while preserving both the original carton volume and the weight of the packed bulk product. This procedure enables a systematic recalculation of packaging carton dimensions with the objective of optimizing pallet utilization. This method aims to maximize pallet volume fullness, reduce filling time, enhance stability, and improve various other critical parameters related to the protection and handling of goods. However, some of these factors fall outside the scope of this study and will not be discussed further. A key aspect of this methodology is that each recalculated carton dimension ensures the same product weight as initially specified while being strategically designed to facilitate efficient pallet construction. Specifically, the dimensions of the cartons are selected as integer multiples of the pallet dimensions, ensuring a structured and space-efficient arrangement. Furthermore, selecting different types of cartons results in variations in the total paper surface area required for a given set of dimensions, thereby influencing the overall material weight. As will be demonstrated in Table 1 multiple alternative sets of carton dimensions may be derived, all of which accommodate the same product weight. For each of these dimension combinations and for a given carton type, the corresponding paper surface area, and consequently, the total paper weight, will differ. To illustrate this concept, we present a case study on the recalculation of packaging dimensions in the following section. One of the most popular and widely consumed products is the 12.5 kg package for whole nut kernels. The common packaging parameters is a corrugated carton telescope type, with standard dimensions 450 mm × 300 mm × 300 mm.

Table 1.

Optimized new packaging dimensions weight (12.5 kg).

Furthermore, different carton types can be used for bulk products. In Table 2, the carton surface area (S) is calculated for the most common corrugated carton types (slotted, folder, and telescopic). As shown, the total carton surface area, and therefore material consumption, depends directly on carton dimensions, highlighting the critical role of box dimensional design in packaging material use.

Table 2.

Box surface calculations.

In Table 1, a permissible deviation of up to 300 g in the net weight of the packaged product is considered, remaining within the acceptable tolerance limits defined by statistical quality control standards for weight variability. For all evaluated combinations of carton dimensions, the resulting aggregate content weight consistently approximates 12.2 kg, thereby ensuring uniformity in volumetric efficiency (carton fill rate) and gross pallet loading weight. The reconfiguration of carton dimensions introduces several logistics optimizations benefits from an operations research perspective:

- (a)

- Improved pallet space utilization efficiency,

- (b)

- Increased transportable mass per pallet,

- (c)

- Enhanced structural stability during transit, and

- (d)

- Improved material handling efficiency, particularly in palletization and depalletization operations.

Among these, aspects (a) and (b) are of primary analytical interest in this study, as they contribute directly to the minimization of transportation frequency and the reduction in GHG emissions per unit of product transported, which is a key strategy in climate-smart supply chain optimization. In the shaded region of Table 2, representing feasible dimensional configurations, we identify and select the carton geometry that best aligns with the dual objectives of logistics efficiency and GHG emission intensity reduction. Carton dimensions that extend to the maximum allowable pallet footprint, while theoretically optimal in space-filling terms, are excluded due to ergonomic inefficiencies and manual handling constraints, which may compromise operational feasibility and labor safety. Accordingly, the highlighted carton dimensions in Table 1 represent a Pareto-optimal compromise, balancing transportation system optimization with practical usability, and contributing indirectly to carbon footprint mitigation in the agricultural product supply chain.

3.3. Track Cargo and Carton Weight CO2 e Consumption Equivalent

Trucks come in various dimensions and payload capacities. With advancements in technology, some trucks now utilize natural gas as fuel, while others are hybrid or fully electric. Without limiting the scope of this study, our focus will be on a 40-ton truck, capable of carrying a maximum load of 20–25 tons. The truck and trailer dimensions are as follows: internal length: 13.6 m, internal width: 2.4–2.5 m, internal height: 2.4–2.8 m.

For Euro pallet-sized cargo, the maximum number of pallets that can fit within the truck’s loading area is 33 pallets. We assume a single-level pallet arrangement, as the pallet height (including its base) is 1.9 m, which does not allow stacking a second layer of pallets above the first level. Based on CO2 emissions assessment tables, fuel consumption is 30–40 L per 100 km, and CO2 emissions per liter of diesel is 2.68 kg CO2/L [33] (p. 10724).

Regarding the CO2 emissions associated with the manufacturing of corrugated cardboard for packaging cartons, data from DS Smith provides key insights. For a flute-type CB carton, the corrugated cardboard structure consists of a double-wall combination of C-flute and B-flute layers. For a carton with dimensions (595 mm × 390 mm × 167 mm), the weight is 738 g, equivalent to 753 g/m2. This information is essential for evaluating the environmental impact of packaging materials and optimizing logistics and supply chain sustainability [34].

3.4. Sustainable Packaging Logistics and Box (Carton) Dimensions

The importance of selecting optimal packaging dimensions is analyzed below, with particular emphasis on their implications for supply chain efficiency and environmental performance. Carton box dimensions are typically determined by the target net weight per unit, which is influenced by both market-driven constraints (e.g., price competitiveness and consumer preferences) and the functional requirements of the packaging system.

Multiple feasible dimension combinations exist, as shown in Table 1, where all proposed optimized dimensions are submultiples of the pallet dimensions, and the resulting carton volume for bulk product packaging remains equivalent to that of the original design. The evaluation of these alternatives constitutes a critical component of the design space exploration within an operations research framework. Beyond the dimensional specification of primary packaging, it is critical to account for the secondary packaging system including the type and surface area of paperboard materials required, which vary by carton type. Detailed quantitative assessments were performed for common carton formats such as regular slotted containers, telescope style lid and base boxes, and folder type. A telescope type carton is provided in Figure 4. Selecting optimal carton dimensions contributes significantly to tertiary packaging efficiency, enabling higher carton counts per pallet and maximizing the payload mass per transport unit (e.g., truck), (please see Figure 5). This optimization directly supports the reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions per kilogram of transported product by minimizing the transport frequency and improving vehicle load factor utilization. Moreover, the choice of carton dimensions, in conjunction with the selected carton type, determines the material intensity of the packaging system, particularly the paperboard surface area required which directly influences the CO2-equivalent (CO2 e) emissions associated with packaging production. As a result, optimizing both dimensional parameters and material configurations is essential not only for cost-efficiency, but also for enhancing the climate resilience and carbon mitigation potential of agricultural product supply chains.

Figure 4.

Packaging of walnuts in shell, a corrugated telescope box, and the total surface of two pieces of carton.

Figure 5.

Impact of box dimensions on pallet utilization, carton material use, and full-truck CO2 e emissions.

3.5. Case Study—Choosing Appropriate Carton Dimensions to Reduce the Ecological Footprint

The key assumptions for the following calculations are as follows:

- All calculated alternative dimensions lead to the same level of packaging efficiency.

- For all calculations of paper usage, depending on the type of carton and its dimensions, we assume the use of the same type of cardboard, specifically CB carton, with an equivalent weight of 753 g/m2.

Our purpose is to calculate the improvement in CO2 emissions per carton due to a greater load carried per piece and due to the use of less cardboard for the selected dimensions of the packaging carton.

Let us consider a typical distance of transport of the goods at 200 km. The total emission for the type of truck described in Section 3.3 is as follows: total fuel consumption equivalent CO2 = . The total number of boxes transported is 33 pallets × 48 cartons/pallet = 1584 cartons and a total weight of 19.32 tons. While with the original dimensions of the carton, we transported 33 pallets × 40 cartons/pallet = 1320 cartons and a total of 16.5 tons. As a final result, we extract that we have the following:

The carton is constructed from CB-flute corrugated cardboard, a double-wall configuration combining C-flute and B-flute layers. According to a DS Smith technical datasheet, a carton with external dimensions of 280 mm × 400 mm × 110 mm has a total mass of approximately 473 g, corresponding to a board areal density of 685 g/m2. A broad review of corrugated cardboard carbon footprints reports cradle-to-grave emissions around 0.94 kg CO2 e per kg of corrugated board, reflecting combined production and end-of-life contributions [35]. Table 3 shows a total reduction of 14.5% in CO2-equivalent emissions per kilogram of transported load attributable to fuel consumption. This result highlights the importance of recalculating carton packaging dimensions, as improved pallet and truck volume utilization directly enhances transport efficiency and reduces fuel-related emissions.

Table 3.

CO2 e per box and per kgr of both products to fuel truck consumption.

Based on Table 4 and Table 5, we conclude that the original packaging uses the minimum paper surface, and therefore the equivalent CO2 emissions. In this case, we choose to use another type of carton packaging instead of the telescope slotted type, resulting in a 60% reduction in equivalent CO2 e/kgr emissions due to the reduction in the use of cardboard.

Table 4.

Optimized new packaging dimensions weight (12.5 kgr), telescope-type carton.

Table 5.

Optimized new packaging dimensions weight (12.5 kgr), slotted-type carton.

3.6. Sensitivity Impact Analyses

A transport scenario impact analysis is performed by varying key operational parameters, including transport distance (±50 km), empty running ratio (0%, 10%, and 20% of total vehicle kilometers), and fuel pathway (100% fossil diesel, a 50% diesel–50% hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO) blend, and a 50% diesel–50% compressed natural gas (CNG) dual-fuel configuration). All scenarios are evaluated for a constant vehicle payload capacity of 25 tn, ensuring the comparability of CO2-equivalent emissions per functional unit.

Table 6 highlights in bold the minimum and maximum CO2-equivalent emissions (kg CO2 e per carton). Calculations assume a constant carton weight of 12.5 kg, are based on Table 2 and Table 3, and correspond to 1584 cartons per palletized truckload. The results show that transport distance, empty running percentage, and fuel type strongly influence CO2 e emissions per carton.

Table 6.

Transport scenario impact analysis.

4. Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that the optimization of packaging carton dimensions plays a central role in enhancing pallet utilization and improving the environmental performance of transportation systems for bulk agricultural products. When examined in the context of previous work on transport efficiency, life cycle assessment (LCA), and packaging design, our findings reinforce the established premise that dimensional alignment between packaging units and pallet bases is a key determinant of load efficiency and operational sustainability. The incorporation of transportation provider constraints such as allowable loading heights, cargo bay geometry, and pallet compatibility demonstrates that packaging configuration must be considered holistically within the logistics chain rather than as an isolated design variable.

The analysis confirms that, for a fixed net product weight, all evaluated carton dimension sets yield-equivalent pallet-level mass and identical payload totals for a standard 40-ton truck configuration. This finding is consistent with prior studies emphasizing that geometric optimization does not inherently alter transport weight-based indicators when net product content remains constant. As a result, CO2 emission intensity (CO2 e/kg/km) remains stable across all feasible dimensional permutations, underscoring that weight distribution, rather than dimensional profiling, governs emissions outcomes at the tertiary packaging level.

However, the study extends the existing literature by demonstrating that carton surface area, and consequently, the quantity of cardboard required, emerges as the decisive optimization factor when environmental outcomes are assessed at the packaging material level. By comparing three principal packaging formats (slotted containers, telescope boxes, and folder-type cartons), we identify the dimension sets that minimize cardboard mass while preserving load capacity. This materially efficient design approach not only reduces the CO2 e associated with packaging production but also amplifies sustainability gains when scaled across high-volume, repeatable logistics operations.

A further contribution of this work is the identification of a consistent downward trend in CO2 e/kg/km as net package weight increases. This effect arises from improved fuel-to-weight efficiency within the transport system, a finding aligned with established transport energy-use models. Importantly, applying the proposed methodology to a meat-processing industrial facility confirms its robustness and generalizability, particularly for bulk, geometry-independent products that are not constrained by product shape. This strengthens its relevance for LCA practitioners seeking to refine system boundaries and emission factors related to packaging inputs and transport dynamics.

Overall, the proposed framework advances the methodological integration of packaging design, operations research, and environmental assessment. By recalibrating packaging dimensions to reduce material intensity while maintaining load efficiency, the approach supports broader decarbonization objectives within the supply chain and logistics systems. The implications extend beyond a single product category, indicating considerable potential for sector-wide adoption and cumulative global CO2 emission reductions.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the strategic optimization of packaging carton dimensions, when aligned with pallet specifications, transportation constraints, and operational requirements can significantly enhance both logistical efficiency and environmental performance. While dimensional variations do not affect pallet mass or transport-related CO2 e/kg/km for fixed net product weights, they exert a substantial influence on the amount of packaging material required. Reducing carton surface area therefore becomes the primary lever for lowering material-related emissions without compromising unit-load performance.

Across the three evaluated carton formats, we identify optimized dimension sets that minimize cardboard consumption and yield the lowest associated CO2 e emissions. Additionally, increasing the net weight per package improves transport efficiency by reducing emissions intensity through enhanced fuel-to-weight utilization. The implementation of this methodology in an industrial meat-processing facility confirms its validity and adaptability within LCA frameworks focused on item-level CO2 e impact reduction.

The proposed recalibration approach not only enables the transport of higher effective payloads, but also decreases the environmental footprint of packaging systems. When applied at scale, this method holds substantial potential for CO2 reduction across the bulk product manufacturing and distribution sectors. Furthermore, we recommend that future LCA models incorporate updated emission factors reflecting both transport weight-based impacts and packaging material footprints, thereby improving accuracy, comparability, and decision-making in sustainability-oriented supply chain analyses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.V.; methodology, T.M.; software, T.M.; validation, K.V. and T.M.; formal analysis, K.V.; investigation, T.M.; resources, K.V.; data curation, T.M.; writing—original draft preparation, K.V.; writing—review and editing, K.V. and T.M.; visualization, T.M.; supervision, S.D.; project administration, S.D.; funding acquisition, T.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in (https://www.lemke-b2bshop.de/en/products/persipanrohmasse-12-5-kg?srsltid=AfmBOoosDIlL2emNfW1bVEd2i1ED-8mssLWjC9Xd0MhNoDIZOB1mRrKO) accessed on 12 January 2026, for typically 12.5 kg packing and coregulate carton for packaging.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ding, X.; Wei, W.; Zhang, B.; Scherer, R.; Damaševičius, R. Apple Packaging Redesign in Luochuan Based on the Concept of Sustainable Packaging. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Industrial Design (AIID), Guangzhou, China, 28–30 May 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 614–627. [CrossRef]

- Tua, C.; Biganzoli, L.; Grosso, M.; Rigamonti, L. Life Cycle Assessment of Reusable Plastic Crates. Resources 2019, 8, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlig, E.; Sadzik, A.; Strenger, M.; Schneider, A.; Schmid, M. Food Wastage Along the Global Food Supply Chain and the Impact of Food Packaging. J. Consum. Prot. Food Saf. 2025, 20, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.; Pålsson, H. Industrial Packaging and Its Impact on Sustainability and Circular Economy: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 333, 130165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S.; Müller, M. From a Literature Review to a Conceptual Framework for Sustainable Supply Chain Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plastics Europe. Plastics—The Facts 2022: An Analysis of European Plastics Production, Demand and Waste Data; Association of Plastic Manufacturers: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Mungkung, R.; Dangsiri, S.; Gheewala, S.H. Development of a Low-Carbon, Healthy and Innovative Value-Added Riceberry Rice Product Through Life Cycle Design. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2021, 23, 2037–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponstein, H.J.; Meyer-Aurich, A.; Prochnow, A. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Mitigation Options for German Wine Production. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 212, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponstein, H.J.; Ghinoi, S.; Steiner, B. Increasing Sustainability in the Finnish Wine Supply Chain: A Country-of-Origin-Based Greenhouse Gas Emissions Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 768–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, R.; Agarwal, R.; Bajada, C.; Arshinder, K. Redesigning a Food Supply Chain for Environmental Sustainability—An Analysis of Resource Use and Recovery. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 242, 118374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo-Iacono-Ferreira, V.G.; Viñoles-Cebolla, R.; Bastante-Ceca, M.J.; Capuz-Rizo, S.F. Transport of Spanish Fruit and Vegetables in Cardboard Boxes: A Carbon Footprint Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 244, 118784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakoudis, E.D.; Tipi, N.S.; Bamford, C.G. Packaging Redesign—Benefits for the Environment and the Community. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2018, 11, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asim, Z.; Shamsi, I.R.A.; Wahaj, M.; Raza, A.; Hasan, S.A.; Siddiqui, S.A.; Aladresi, A.; Sorooshian, S.; Teck, T.S. Significance of Sustainable Packaging: A Case Study from a Supply Chain Perspective. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2022, 5, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Yao, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zeng, F.; Huo, L.; Xing, H.; Jiang, Y.; Lv, Y. The Impact of Packaging Recyclable Ability on Environment: Case and Scenario Analysis of Polypropylene Express Boxes and Corrugated Cartons. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 822, 153650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikström, F.; Williams, H.; Venkatesh, G. The influence of packaging attributes on recycling and food waste behavior—An environmental comparison of two packaging alternatives. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.Y.C.; Tai, A.H.; Zhou, E. Optimizing Truckload Operations in Third-Party Logistics: A Carbon Footprint Perspective in Volatile Supply Chains. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2018, 63, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakoudis, E.D.; Tipi, N.S. An Investigation into the Issue of Overpackaging: Examining the Case of Paper Packaging. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2020, 14, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.; Wang, P.; Lin, M. A Global Optimization Approach for Solving Three-Dimensional Open-Dimension Rectangular Packing Problems. Optimization 2014, 64, 2601–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bher, A.; Auras, R. Life Cycle Assessment of Packaging Systems: A Meta-Analysis to Evaluate the Root of Consistencies and Discrepancies. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 476, 143785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Tang, W.; Hai, Y.; Lang, M.; Liu, Y.; Li, S. Optimization of Truck–Cargo Matching for the LTL Logistics Hub Based on Three-Dimensional Pallet Loading. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morashti, J.A.; An, Y.; Jang, H. A Systematic Literature Review of Sustainable Packaging in Supply Chain Management. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Arca, J.; Comesaña-Benavides, J.A.; Garrido, A.T.G.; Prado-Prado, J.C. Rethinking the box for sustainable logistics. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. ILCD Handbook: General Guide for Life Cycle Assessment—Detailed Guidance; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hemachandra, S.; Hadjikakou, M.; Pettigrew, S. A Scoping Review of Food Packaging Life Cycle Assessments That Account for Packaging-Related Food Waste. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2024, 29, 1899–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Yao, J.; Zhao, X.; Ren, P.; Gustavsson, M.; Wu, C. Review on Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) Studies of Reusable Plastic Crates for Fruit and Vegetables. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2025, 18, 2457345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moresi, M.; Falciano, A.; Cimini, A.; Masi, P. Unveiling the Carbon Footprint of True Neapolitan Pizza: Paving the Way for Eco-Friendly Practices in Pizzerias. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2024, 36, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Borghi, A.; Parodi, S.; Moreschi, L.; Gallo, M. Sustainable Packaging: An Evaluation of Crates for Food Through a Life Cycle Approach. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 26, 753–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.; Molina-Besch, K. Replacing Plastic with Corrugated Cardboard: A Carbon Footprint Analysis of Disposable Packaging in a B2B Global Supply Chain—A Case Study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 191, 106871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Borghi, A.; Gallo, M.; Strazza, C.; Del Borghi, M. An Evaluation of Environmental Sustainability in the Food Industry through Life Cycle Assessment: The Case Study of Tomato Products Supply Chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 78, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Besch, K.; Wikström, F.; Williams, H. The Environmental Impact of Packaging in Food Supply Chains—Does Life Cycle Assessment of Food Provide the Full Picture? Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2018, 24, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljuhani, D.; Papageorgiou, L. Improved Layout Structure with Complexity Measures for the Manufacturer’s Pallet Loading Problem (MPLP) Using a Block Approach. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2021, 14, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Almasarwah, N.; Süer, G. A Two-Phase Algorithm to Solve a Three-Dimensional Pallet Loading Problem. Procedia Manuf. 2021, 39, 1474–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gialos, A.; Zeimpekis, V.; Madas, M.; Papageorgiou, K. Calculation and assessment of CO2e emissions in road freight transportation: A Greek case study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DS Smith. Sustainability Databook 2023 (Carbon Footprint Metrics). 2023. Available online: https://www.dssmith.com/globalassets/corporate/sustainability/sustainability-report-databook-2023/ds-smith-esg-databook-2023.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Cefic; ECTA. Guidelines for Measuring and Managing CO2 Emissions from Freight Transport Operations (Issue 1); European Chemical Industry Council (Cefic): Bruxelles, Belgium; European Chemical Transport Association (ECTA): Bruxelles, Belgium, 2011; Available online: https://www.ecta.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/ECTA-CEFIC-GUIDELINE-FOR-MEASURING-AND-MANAGING-CO2-ISSUE-1.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- European Environment Agency. EMEP/EEA Air Pollutant Emission Inventory Guidebook 2019: 1.A.3.b Road Transport; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019; Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/emep-eea-guidebook-2019 (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- EN 16258:2012; Methodology for Calculation and Declaration of Energy Consumption and Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Transport Services (Freight and Passengers). European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2012.

- Global Logistics Emissions Council. GLEC Framework for Logistics Emissions Accounting and Reporting (Version 2.0). Smart Freight Centre. 2019. Available online: https://www.smartfreightcentre.org/en/what-we-do/glec-framework/ (accessed on 7 January 2026).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.