Abstract

HIV neuroinvasion results in neuronal dysregulation and compromised neurocognition. Neuroplasticity measures, such as HIV cognitive rehabilitation, have shown potential for partially reversing cognitive deficits after HIV invasion. Previous functional NIRS (fNIRS) studies have demonstrated that customized attention brain training (ABT) has the potential to alter brain activity in adolescent HIV. Nonetheless, the effects of ABT on brain functional connectivity in adolescent HIV remain unclear. This study investigated behavioral and functional connectivity changes in adolescent HIV amongst participants (n = 26) receiving 12 weeks of ABT compared to treatment-as-usual (TAU) controls. Twenty-six adolescents living with HIV were recruited and randomly assigned to either the ABT group (n = 13) or the TAU group (n = 13). Participants completed NEPSY-II and fNIRS measures before and after the training. Functional connectivity (FC) measures were evaluated using seed-based correlation analysis, located in the central executive network (CEN) and across the hemispheres. No significant behavioral differences were noted on the NEPSY-II and BRIEF scores; however, functional connectivity measures indicated that the ABT group exhibited significantly increased FCs in the left hemisphere (p < 0.05) following brain training. Additionally, thresholding analysis indicated that the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex may serve as a potential marker for brain training in adolescent neuro-HIV.

1. Introduction

The Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) not only interferes with the body’s immune system but also has a deleterious effect on the body’s central nervous system [1]. Markedly, when HIV permeates the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and enters the cerebral cortex, 15–60% of people affected by neuro-HIV are indicated to experience progressive cognitive and motor decline [2]. Cognitive decline is noted in multiple domains, including working memory (WM) [3], attention and processing speed [4,5], executive functions [6] and response inhibition [7]. Collectively, cognitive deficits arising from neuro-HIV are referred to as HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) [8].

Pointedly, despite the development of highly active antiretroviral drugs (ARTs), the cerebral cortex continues to be a cellular reservoir for HIV, primarily due to the differentiation of monocytes into macrophages within the cortex [1,9]. Once in the cerebral cortex, HIV-initiated pathogenetic neuroinflammation is indicated to result in aberrant neural transmission [10], white and gray matter loss [11], neuronal apoptosis [12] and catecholaminergic dysregulation [13], resulting in the persistence of HAND, both in adult [14] and adolescent HIV [8].

Due to the limitations of ARTs, particularly their limited permeability in the cerebral cortex [1], coupled with their neurotoxicity [8], HIV brain training (the neuroscience literature uses the following terms: HIV brain training, HIV adaptive training, HIV cognitive rehabilitation, HIV cognitive remediation, HIV cognitive intervention, and HIV computerized cognitive training interchangeably; in the article, the terms HIV brain training and HIV cognitive training will be preferred) protocols have taken added pre-eminence to reverse cognitive impairment, following neuro-HIV. For example, with reference to adolescents with HIV, brain training protocols have been applied to remediate attention [15], working memory [3], and executive functions [16,17]. Notwithstanding the above, there continues to be a dearth of research pairing behavioural outcomes with subsequent HIV brain training and neuroimaging measures to investigate the efficacy of brain training protocols at a neuronal level, especially in children and adolescents living with HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa [18,19].

At the time of writing, limited studies have paired behavioural outcomes, with neuroimaging outcomes to investigate HIV brain training. In their study [20] used functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), to investigate the effects of working memory training (WMT), on near and far transfer cognitive gains, coupled with blood oxygen level dependency (BOLD) changes, before and after brain training. Findings indicated that WMT was associated with significantly, reduced BOLD, activation in the frontal and parietal regions, of HIV+ patients (n = 33; mean age = 50; SD = 4.8), and HIV negative controls (n = 41; mean age = 52; SD = 4.8) receiving WMT. As noted by the authors, reduced BOLD activation and increased performance on untrained near tasks (Digit Span and Spatial-Span) following WMT were suggestive of improved intrinsic functional connectivity and reduced neuronal demand to complete working memory tasks [20].

In a study using functional near infrared spectrometry (fNIRS), [21] investigated neuronal changes amongst HIV+ adolescents (n = 13; mean age = 16; SD = 1.2); receiving brain training to remediate attention skills, and HIV+ controls (n = 13; mean age = 17; SD = 1.3). Findings indicated decreased BOLD activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal (DLPF) and frontopolar network when completing incongruent trials on the Stroop Colour Word Test (SCWT) following HIV brain training. Although decreased BOLD activation was indicative of improved neural efficiency in the SCWT, behavioural improvements did not reach statistical significance post-brain training.

Notwithstanding the above (i.e., decreased BOLD activation, following HIV brain training), neuronal adaptation is best investigated through functional connectivity analysis [22,23]. Functional connectivity (FC) is defined as the “temporal correlations between spatially remote brain events” [24] p.58. The advantage of FC analysis, as opposed to functional segregation, is that FC enables the study of distributed processing and functional interaction across and within brain regions. FC analysis, therefore, enables the determination and analysis of cortical synchrony and temporal dependence (time) of neuronal activation within the cortex. As previously noted, there is a paucity of research investigating the relationship between cortical brain plasticity and neuro-HIV. Notwithstanding this limitation, there is an even greater dearth of research investigating functional brain connectivity following HIV cognitive rehabilitation in adolescent populations.

1.1. Functional Connectivity and HIV Brain Training

A literature review indicates that the sole study investigating FC following HIV brain training is the study by [25]. They investigated FC, subsequent working memory training (WMT), in adult HIV populations using resting-state fMRI (rsfMRI). rsfMRI investigates changes in intrinsic functional networks during states of rest when subjects are not engaged in performing a specific cognitive task or receiving any cognitive stimulation [26]. The advantage of resting state analysis is that it enables the identification of intrinsic brain connectivity; and the identification of biomarkers for brain health and brain injury [23]. In its application, rsfMRI uses spontaneous BOLD signals to study FC, both in spatially distinct and near brain regions.

With reference to HIV brain training, ref. [25] investigated FC, as estimated by independent component analysis (ICA) and graph theory. With reference to graph theory, they investigated whether WMT (CogMed) resulted in “network normalization” within resting state networks (RSNs), as determined by eigenvector centrality and local efficacy measures. In summary, eigenvector centrality measures the contribution of a node within a cortical network (e.g., default mode network). Specifically, nodes with higher eigenvector centrality represent those that are not only well-connected within a network but also connected to other highly central nodes within the network. Consequently, highly connected nodes act as hubs for information flow, enabling efficient communication between nodes within a network. Similarly, local efficiency measures how efficiently information is exchanged within a local neighborhood of a node within a network.

In their investigation, ref. [25] investigated “network normalization”, pre- and post-WMT, in the default mode network (DMN), cognitive control network (CON) (the CEN is referred to as the Cognitive Control Network (CON) in the study; a growing body of research suggests the CON and CEN may share the same anatomical correlates [27,28]), the visual network (VIS), the auditory network (AUN), and subcortical networks (SC). The authors defined “network normalization” as the process of restoring or optimizing the functional connectivity patterns within the cortex to typical neuronal network patterns. As such, ref. [25] investigated whether HIV+ participants would indicate similar network organization to HIV-negative controls post WMT, as determined by eigenvector centrality and local efficiency analyses.

Participants were inclusive of HIV+ (n = 53; mean age = 50; SD = 1.5), and HIV seronegative controls (n = 48; mean age = 49; SD = 1.6), matched for sex, race, and socioeconomic status. At pre-intervention, findings indicated abnormalities in RSNs in the HIV+ group, as indicated by eigenvector centrality and local efficiency measures. Post-intervention (one month) measures indicated that “the eigenvector centrality of the ventral DMN in PWL (people with HIV) becomes more like that of SNs (seronegative)” [25], p. 1560. The authors concluded that changes in eigenvector centrality ‘may suggest that the vDMN with high eigenvector centrality might be a key neural substrate leading to normalization of brain function following WMT” [25], p. 1560. Notably, eigenvector centrality normalization (in the HIV+ group) was associated with improved memory outcomes at post-assessment. Notwithstanding this finding, the study did not provide statistical significance measures (p-values) for post-assessment measures (attention, executive functions), except for detailing improved cognitive outcomes in memory function.

1.2. The Present Study

As noted, there is a dearth of research investigating HIV brain training outcomes, paired with objective neuroimaging measures in Sub-Saharan Africa [19]. In a previous study [29], our research group illustrated the feasibility of fNIRS to investigate regional hemodynamic activity in pediatric and adolescent HIV. In a follow-up study [21], we investigated the effect of attention training on hemodynamic activation within the CEN, in adolescent HIV. Findings indicated that brain attention training (12 weeks) in adolescent HIV is associated with decreased hemodynamic activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPF) and frontopolar network, in response to completing incongruent trials, on the Stroop Color Word Test (SCWT). The previous findings investigated block-averaged hemodynamic activation (HbO) in response to cognitive stimuli. The current study explored task-based functional connectivity, pre- and post-attention brain training, using seed-based functional connectivity.

A substantial departure from [25], who investigated FC using rsfMRI in an adult HIV population, this investigation explored FC within an adolescent HIV population. The decision to pursue fNIRS optical imaging techniques was based on cost limitations associated with fMRI in Sub-Saharan Africa [30]. Additionally, as opposed to studying FC using graph theory (eigenvector centrality and local efficiency), the current study used fNIRS task-related seed-based correlation. Seed-based correlation connectivity is based on the selection of an priori “seed” or “seed region,” which is selected based on a priori relevance to the field of study [31,32]. The technique examines the temporal correlation of hemodynamic activity between the seed and distant nodes/voxels within a cortical network of interest [31,32]. Seed-based connectivity analysis has provided insights into cortical synchrony in neuro-HIV [33] and has helped establish biomarkers for neurological disorders [34], and psychological treatment [35]. In addition to studying FC, the study investigated near and far cognitive transfer emanating from attention brain training. Due to the scarcity of published research on seed-based correlation analysis to investigate FC in fNIRS, the study did not propose any hypotheses but explored the following study questions.

1.3. Study Research Questions

- Compared to controls, do HIV+ participants receiving attention training indicate improved cognitive outcomes on behavioral measures post-intervention?

- Compared to controls, do HIV+ participants receiving attention training indicate greater functional connectivity in either of the hemispheres (left or right) within the CEN post-intervention?

- Which voxels (if any) would “survive” increased seed correlation thresholding (0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8) at post-training (within the experimental group)?

2. Materials and Methods

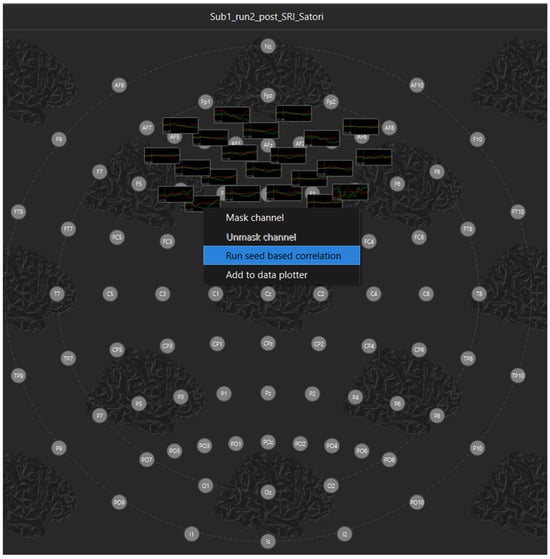

The materials and methods pertaining to the study are described in a previously published manuscript [36]. With specific reference to seed-based analysis, the study followed fNIRS guidelines for conducting resting state functional connectivity analysis, using Satori fNIRS (NIRX Software, Version 1.8.2, Brain Innovation, BV, the Netherlands). As such, seed-based correlations were calculated for each run/subject based on seed “S3-D2.” Seed-based correlation was performed by computing the temporal correlation between the a priori seed (S3-D2) and the rest of the channels. This procedure was performed for all participants, inclusive of the experimental and control groups. An example of a corresponding seed correlation of subject 1 is illustrated in Figure 1. An example of a seed-based map for all experimental subjects at pre-intervention is illustrated in Figure 2. Based on a priori evidence indicating the plasticity of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (L-DLPF) in HIV cognitive rehabilitation [20,37,38], this seed was selected as the seed region for the cross-correlation. For the fNIRS analysis, this seed, (channel 6; x = −31; y = 39; z = 4l; Supplementary Materials Figure S1 and Table S1) indicated a specificity of 92%, as determined by fOLD [39].

Figure 1.

Seed-based correlation first-level analysis.

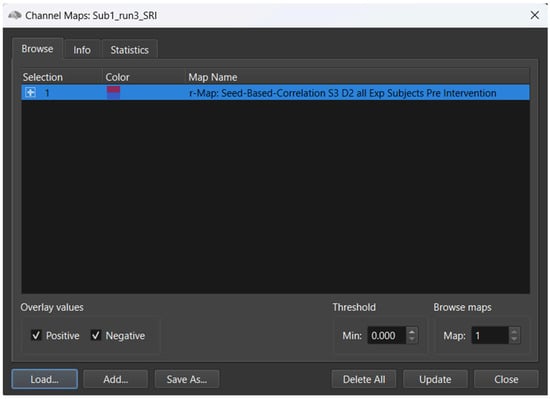

Figure 2.

Seed-based correlation second-level analysis.

Similarly to other implementations, adopting fNIRS seed-based FC, i.e., [34], in order to increase the normality of the distribution of correlation values, Fisher’s r-to-z transformation was applied to each correlation coefficient. As such, Fisher’s transformed bivariate correlation coefficients were calculated between the seed BOLD time series and each of the individual channel BOLD time series (Supplementary Materials Figure S2A). Following Fisher’s r-to-z normalization, transformed correlation maps were generated for each subject and for the group-level analysis at pre-test and at post-intervention. As such, connectivity correlation (r) maps were derived, representing the size and direction of the correlation. All correlation values ranged from −1 to +1. Negative correlations within the correlation maps were coded as “cold” colors (blue), while positive correlation values were coded as “warm” colors (red) (Figure 2).

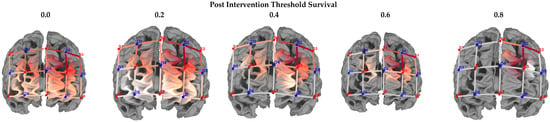

To further focus our analysis on identifying regions (channels) showing greater connectivity with the seed region (S3-D2) at post-rehabilitation, we employed seed survival thresholding. The percentage of surviving channels after thresholding increment would thus be indicative of channels with the greatest correlation to the seed. For instance, if the threshold was set at r = 0.2, this threshold determined how many voxels/channels “survive” a correlation greater than 0.2. For the study, threshold increments of r = 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 were set for threshold “survival” analysis to determine functional connectivity. Functional connectivity was computed separately for each hemisphere, i.e., for the seed (S3-D2), with the corresponding channel in each given hemisphere. The thresholding and seed-based analysis were performed within Satori fNIRS (NIRX Software, Version 1.8.2, Brain Innovation, BV, the Netherlands). Functional connectivity differences in the two hemispheres were computed using the paired and between-subjects t-test.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

Table 1 summarizes the sample characteristics at baseline. Chi-squared tests revealed no significant differences between the groups by ethnicity (χ2 = 0.38, p = 0.827) and schooling (χ2 = 0.195, p = 0.658). There were differences by sex (χ2 = 3.86, p = 0.05) and age group (χ2 = 3.94, p = 0.05). Although all participants were on a course of cART (n = 26), significant differences were noted in terms of medication between the groups (χ2 = 6.01, p = 0.01), with three participants in the treatment group on an additional course of psychotropic medication (n = 2), coupled with one child on ADHD medication (n = 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants and their comparisons (Mean/SD).

Research Question 1

In the first research question, the study investigated whether the experimental group would indicate improved behavioral outcomes following the brain training.

3.2. Behavioral Data

3.2.1. Baseline Comparisons Between Intervention and Control Groups

At baseline, despite randomization to groups, the experimental group obtained a significantly higher score on the geometric puzzle (t = 2.52; p = 0.001; d = 0.9), indicating greater ability with visuospatial perception and mental rotation relative to the control group. There were no other significant differences (p > 0.05) between the groups on any of the baseline assessments, indicating equivalence (Table 2) (Supplementary Materials Data S1).

Table 2.

Neuropsychological Performance in the Experimental and Control Groups at Baseline.

3.2.2. The Effect of the Intervention: Differences Between Experimental and Control Groups Post-Test

Differences in pre- and post-brain training scores are indicated in Table 3. For the NEPSY-II, the only significant difference in favor of the experimental group was the Inhibition (INI) task (difference = 1.5; 95% CI (5.69, 6.81); F (1, 22) = 7.45; p = 0.012, d = 0.253). The control group showed significantly greater scores on the Response Set on post-assessment (difference = 2.48; 95% CI (7.02, 9.17); F (1, 21) = 5.61; p = 0.027, d = 0.21), compared to the treatment group. Although the treatment group indicated greater mean scores on several NEPSY-II subtests post-training, these were not statistically significant. For the BRIEF functional scales, the treatment group showed significantly elevated scores in the BRI (difference = 7.41; 95% CI (15.5, 19.1); F(1, 23) = 15.71; p = 0.001, d = 0.4) and MI (difference = 8.59; 95% CI (20.18, 25.81); F(1, 23) = 9.64; p = 0.05, d = 0.29) compared to the control group. In summary, the attention brain training was associated with limited near and far cognitive transfer, as measured by behavioral profiles from the NEPSY and BRIEF.

Table 3.

Mean and standard deviation for treatment and control groups pre- and post-assessment.

3.2.3. Research Question 2

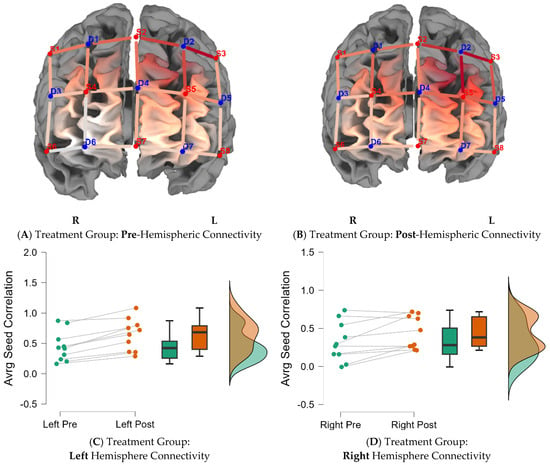

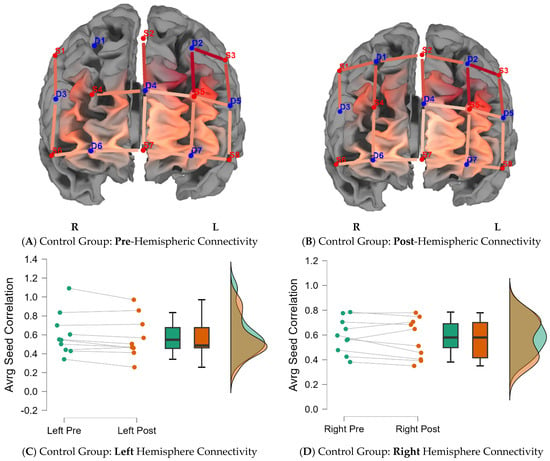

In the second research question, the study investigated whether the treatment group would indicate greater functional connectivity in either hemisphere (right or left) due to brain training. Figure 3 indicates average seed correlation differences within the treatment group pre- and post-training (Supplementary Materials Table S2D for average seed correlations). Figure 4 indicates average seed correlation differences within the control group, pre- and post-training (mean average scores for seed correlations are noted in Supplementary Materials Table S2D).

Figure 3.

Functional connectivity across the hemispheres for the treatment group. Note: Seed correlations pre- (A) and post-intervention (B) for the treatment group BY seed (S3-D2). Average differences for the left and right hemispheres, pre- and post-training, for the treatment group are indicated in the caption (C,D).

Figure 4.

Functional connectivity across the hemispheres for the control group. Note: Seed correlations pre- (A) and post-intervention (B) for the control group BY seed (S3-D2). Average differences for the left and right hemispheres, pre- and post-training, for the control group are indicated in the caption (C,D).

3.3. Neuroimaging Data

3.3.1. Answering Question 2: Between-Subject Analysis

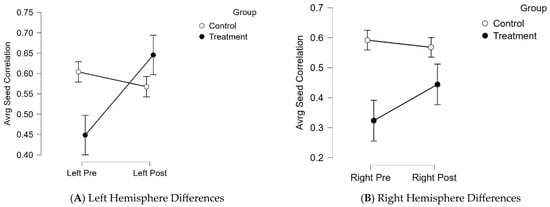

Average seed-correlation differences between groups by hemispheres were calculated by controlling for pretest scores using Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVAs) (Supplementary Materials Figure S2B,C). The treatment group showed significantly greater connectivity in the left hemisphere (difference = 0.1; 95% CI (0.57, 0.64); F (1, 17) = 37.98; p = 0.0001, d = 0.7), compared to the control group, post-brain training. There were no significant differences between groups on right hemisphere connectivity. Figure 5 summarizes group differences by hemisphere, emphasizing greater FC in the left hemisphere of participants in the treatment group post-brain training (M = 0.64; SD = 0.26), compared to baseline (M = 0.44; SD = 0.24).

Figure 5.

Between- subject differences in hemisphere activation Note: (A). The treatment group indicated a significant increase in functional connectivity in left hemisphere activation, pre- and post-training. (B). The treatment group showed increased functional connectivity in the right hemisphere, with a slight decrease in right hemisphere activation in the control group.

3.3.2. Research Question 3

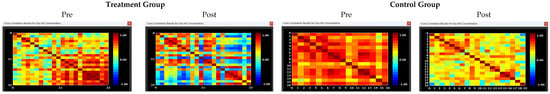

In the final research question, we investigated which voxels would “survive” increased seed correlation thresholding (0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8) post-training (within the experimental group). This data was used to estimate which voxel would indicate the largest correlation with the seed, thus providing a reasonable “marker” for cognitive rehabilitation protocols. Figure 6 illustrates the correlation matrices, both pre- and post-training, by group. As illustrated in Figure 7, increased thresholding (at 0.8) led to the survival of two channels (S2-D2 and S3-D5), inclusive of voxels in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (x = −9; y = 41; z = 50) and those in the pars triangularis of Broca’s Area (x = −46; y = 39; z = 26) (Table 4).

Figure 6.

Correlation matrices pre- and post-intervention. Note: Correlation matrices for seed-based correlation connectivity in the HIV treatment and control group, pre- and post-training. The intensity maps indicate highest FC as denoted in red blocks (strong correlation). Lower or weaker connectivity is denoted in yellow/blue boxes. The treatment group showed increased connectivity post-intervention in left activation. There was a slight decrease in connectivity in the control group at post-measures.

Figure 7.

Threshold survival: experimental group post-intervention averaging. Note: Comparison of different threshold levels, indicating surviving cortical regions, post-intervention (experimental group). Heatmaps were calculated using seed-based correlation. The 2D maps below indicate the surviving thresholds. Warmer colors in the 3D maps indicate greater seed-based function connectivity (Seed = S3-D2).

Table 4.

Cortical region surviving 80% thresholding.

4. Discussion

HIV crosses the BBB, leading to disturbed neuronal transmission, which is associated with decreased cognitive functions, collectively called HAND [2]. Given the persistence of HAND in the era of cARTs, our study explored the extent to which neuroplasticity, in the component of attention training, may lead to improved functional connectivity (FC) and improved behavioral outcomes, as determined by near and far cognitive transfer gains. To determine neural mechanisms that underlie improved FC, we employed seed-based correlational functional connectivity, with the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex being the primary seed of our study. Our analysis revealed nuanced findings related to functional connectivity and behavioral findings regarding subsequent attention training.

Contrary to previous studies, which indicate near and far transfer cognitive gains, subsequent cognitive training in adolescent neuro-HIV, e.g., [17], our study found that attention training resulted in minimal behavioral gains. Primarily, findings indicated that the sole cognitive domain indicating significant changes in the treatment group after the intervention was the Inhibition subtest (p = 0.012, d = 0.253). This task gives the ability to inhibit automatic responses in favor of novel responses. Notably, although the experimental group showed greater improvements (based on mean scores) on multiple near (auditory attention, inhibition switching) and far (memory and learning, visuospatial) cognitive measures post-intervention, these did not reach statistical significance.

Similarly, there were no near and far transfer effects on parent-rated functional scales on the BRIEF. Unexpectedly, the control group indicated improved performance on the Response Set (p = 0.027, d = 0.21), compared to the treatment group. Plausible explanations may exist for the above findings. Firstly, the elongated nature of the intervention (12 weeks, 30 sessions) and the timing of the intervention exercises might have resulted in both intervention fatigue and diminished adherence to the intervention. With reference to the length of the intervention, we chose to implement a longer intervention period, expecting more near-to-far transfer gains. This was evidently not the case. There is reason to believe that the prolonged length of the intervention might have resulted in diminished enthusiasm for the intervention [40], influencing post-assessment performance.

In a similar vein, the study implemented the intervention protocol after school hours (3 pm–5 pm) and occasionally over weekends; it is thus plausible that the timing of the intervention might have affected study adherence, as participants could not always complete the intervention due to fatigue. As such, although the intervention was customized to each participant, the nonlinear progress from one stage of the intervention to the next might have affected post-assessment scores. In line with the above, it is important to note that the control group performed better on the Response Set subtest compared to the treatment group. This finding may be explained by natural cognitive maturation independent of intervention. As highlighted by [41] and supported by [42], since participants in our study were largely adolescents attending primary or secondary schooling, education might naturally foster improved cognitive flexibility coupled with intensive brain reorganization experienced during adolescence. Irrespective of our behavioral findings, other studies e.g., [43] have reported a lack of near and far transfer gains amongst experimental samples and greater cognitive gains amongst controls [44] compared to the treatment group.

Notwithstanding behavioral findings, which indicated limited between-group differences on neuropsychological measures, post-intervention, the study found significant differences between the groups on average seed correlation FC measures. Notably, the findings indicated greater left hemisphere connectivity in the experimental group following the intervention. Nevertheless, hemispheric asymmetry has not been fully characterized in neuro-HIV [45]. Current evidence indicates compromised white matter integrity, particularly in right hemisphere structures, implicated in visuospatial processing in children and adults infected with HIV [46], which may result in specific impairments in visuospatial processing. Severe selective cortical thinning has also been observed in the left hemisphere (frontal eye field and perisylvian language areas) in neuro-HIV [47], with a comprehensive meta-analysis [48] indicating a proclivity for neuro-HIV to compromise the left inferior frontal gyrus function compared to controls. To this extent, significant group differences (HIV+ vs. HIV−), in left hemispheres cortical thinning (left inferior frontal, LDFPF, left inferior parietal), have been the primary explicator for observed differences in selective attention and inhibition outcomes, as measured by the Flanker Interference Task [49].

Collectively, cortical thinning in the left frontal gyrus, has been associated with symptoms associated with HAND [48], as such, our study findings indicating increased left hemisphere FC, subsequent to the intervention, are promising findings. Significantly, our findings indicating greater FC post-intervention within the treatment group may be suggestive of possible compensatory processes, in neuro-HIV, due to the intervention. At a clinical level, these findings are similar to fMIR studies, suggesting a lateralized pattern of functional connectivity, in which the left hemisphere has greater inter-hemispheric connectivity in clinical populations, including schizophrenia and autism [50,51].

Lastly, the study investigated the effect of threshold survival (r = 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8) on seed correlation FC within the treatment group at post-intervention. Increased thresholding (r = 0.8) led to the survival of two channels within the LDLPF and frontal eye field (BA 9: x = −46, y = 39, z = 20; BA 46: x = −9, y = 4, z = 50). These findings are significant, as they suggest that the LDLPF could be a potential marker for brain plasticity in the context of adolescent neuro-HIV. To this end, due to its modularity (efficiency) in processing multiple, distinct cognitive properties, including attention, memory, language, and learning [52], the left hemisphere is largely implicated in neuronal plasticity [52]. By implication, although inconclusive, threshold survival outcomes may suggest that the LDLPF may be a primary neural substrate for future brain plasticity protocols, especially given the heterogeneous nature of adolescent neuro-HIV [53].

Significantly, threshold survival findings may suggest that the CEN (dorsolateral prefrontal, lateral inferior parietal), in concert with the default mode network (DMN), may play a critical role in neuro-HIV and brain plasticity. In their study, [25] found that working memory training led to increased functional connectivity and normalization of the ventral default mode network (DMN) in adult HIV. The authors explain that DMN “normalization” to that observed in HIV-negative controls indicates the value of brain training to reverse compromised cognitive decline in adult neuro-HIV. The conjoined interpretation of our findings and those by [25] and others may confirm the dual connection between the central executive network and the default mode network [54]. To date, research indicates that the CEN and the DMN complement each other in the manner that the CEN is responsible for “top-down attention processing,” which is a task-oriented cognitive process required in maintaining task vigilance, whilst the DMN contributes to “bottom-up processing,” required when the mind is at rest [55]. It suffices to say that the relationship between the role of the CEN and DMN in the context of HIV cognitive training is at an early stage; however, our findings in relation to those [25] provide early considerations that cortical training may enhance the association between the CEN and the DMN.

Summarily, improvements in brain training were noted at the neuronal level, and these improvements did not explicitly transfer to behavioral outcomes following brain training. As previously noted in a comprehensive systematic review investigating neuronal changes following working memory training [56], cortical changes often precede observable cognitive gains, which are often observed at later stages in brain training protocols.

Limitations and Future Directions

While the study contributes to the study of adolescent neuro-HIV, specifically neuroplasticity, and its effects on relevant cortical neural networks, there are limitations within the study that warrant discussion. Due to the high attrition rate experienced, the study had a relatively small sample size, consequently affecting statistical power to reliably extrapolate study findings. Moreover, as observed in topographical brain maps (r-maps), the high scalp coupling indexes (SCI = 0.75) employed in the study (pre- and post-fNIRS assessment) necessitated the removal of neuroimaging data from a few subjects (n = 3), affecting the final sample size for data analysis. It is recommended that future studies employ a larger sample size to cater for attrition rates and employ a lower SCI index when conducting fNIRS research with participants of color, as pigmentation may affect fNIRS pre-processing measures [57].

In addition to sample size improvements, study design improvements are suggested. It is recommended that future neuro-HIV studies, specifically with adolescent populations, employ an active control group instead of a treatment-as-usual control [40]. In terms of rehabilitation research, active controls have been noted to better ascertain the active ingredient in brain training protocols compared to passive controls. Lastly, our fNIRS protocol covered a limited region of interest (Supplementary Materials Figure S1 and Table S1) to investigate seed-based connectivity and neuroplasticity. It is recommended that future studies cover regions inclusive of the CEN and DMN to investigate FC and neuro-HIV brain training comprehensively. Similarly, although the study observed increased left-hemisphere connectivity within the experimental group, supposedly reflective of neuroplastic response (i.e., attention training), given that groups were nonequivalent at hemodynamic baseline (Figure 6), it is a possibility that FC findings may be representative of baseline instability, thus independent of the intervention. Future research could mitigate preponderance in baseline non-equivalence by matching participants across all indices before post-rehabilitation analysis.

Finally, there is a lack of consensus regarding optimal thresholds for investigating functional connectivity and survival analysis [58]. The study employed survival analysis based on an increment of 20%. Although fiducial for our study, it is recommended that future studies employ automated thresholding methods for fNIRS-FC as employed in [59]. Automated thresholding would bolster functional connectivity through, for example, using assortativity measures. FC assortativity would thus better estimate and quantify the tendency of different nodes within a network, therefore, evaluating the tendency of nodes to connect to other nodes with a similar (positive assortativity) or a dissimilar connection (negative assortativity).

5. Conclusions

The study applied seed-based connectivity to rsfNIRS data to assess functional connectivity in the context of brain training and adolescent neuro-HIV. Findings indicated that attention training was associated with limited behavioral changes post-rehabilitation but improved functional connectivity in the left hemisphere for participants receiving attention training. Significantly, thresholding indicated that LDLPF may be a possible marker for brain training in the context of adolescent neuro-HIV. Our findings hold promise for the upscaling of evidence-based brain training protocols to remediate maladaptive cognitive outcomes, sequent neuro-HIV.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16031270/s1, Figure S1: fOLD location decider, and fNIRS channels; Figure S2: Fischer-transformed average seed correlations; Data S1: Neuropsychological behavioral data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Z.; methodology, S.Z.; software, S.Z.; validation, S.Z.; formal analysis, S.Z.; investigation, S.Z.; resources, S.Z.; data curation, S.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Z. and D.B.; writing—review and editing, S.Z.; visualization, S.Z.; project administration, S.Z.; funding acquisition, S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the South African National Research Foundation (NRF), Thuthuka Grant (TTK200408511634), and the Article Processing Charge (APC) was funded by Rhodes University (PP05/2026).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee) of the University of the Witwatersrand (protocol code M211073, 9 December 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the author.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the supportive role of Harvard University, through the Center for African Studies (CAS), for providing time and resources to complete the writing of this manuscript. The corresponding author also acknowledges the supporting role of Kate Cockcroft and Aline Ferreira-Correia for their mentorship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CEN | Central executive network |

| DMN | Default mode network |

| FN | Functional connectivity |

| fNIRS | Functional near-infrared spectrometry |

References

- Morgello, S. HIV neuropathology. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018, 152, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alford, K.; Vera, J.H. Cognitive impairment in people living with HIV in the ART era: A review. Br. Med. Bull. 2018, 127, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, S.; Cockcroft, K. Working with memory: Computerized, adaptive working memory training for adolescents living with HIV. Child. Neuropsychol. 2020, 26, 612–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, J.; Correia, A.F.; Schutte, E. Attention and concentration functions in HIV-positive adolescents who are on anti-retroviral treatment. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2014, 44, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Zhu, S.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Wang, K. Selective impairments of alerting and executive control in HIV-infected patients: Evidence from attention network test. Behav. Brain Funct. 2017, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugarski Ignjatovic, V.; Mitrovic, J.; Kozic, D.; Boban, J.; Maric, D.; Brkic, S. Executive functions rating scale and neurobiochemical profile in HIV-positive individuals. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, S.; Perez, A.; Fouche, J.P.; Phillips, N.; Joska, J.A.; Vink, M.; Myer, L.; Zar, H.J.; Stein, D.J.; Hoare, J. Efavirenz is associated with altered fronto-striatal function in HIV+ adolescents. J. Neurovirol. 2019, 25, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, S.; Ances, B.; Cinque, P.; Dravid, A.; Dreyer, A.J.; Gisslén, M.; Joska, J.A.; Kwasa, J.; Meyer, A.C.; Mpongo, N.; et al. Cognitive impairment in people living with HIV: Consensus recommendations for a new approach. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2023, 19, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmshurst, J.M.; Hammond, C.K.; Donald, K.; Hoare, J.; Cohen, K.; Eley, B. NeuroAIDS in children. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018, 152, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brew, B.J. Introduction to HIV infection and HIV neurology. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018, 152, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B.K.; Roth, L.M.; Grinspan, J.B.; Jordan-Sciutto, K.L. White matter loss and oligodendrocyte dysfunction in HIV: A consequence of the infection, the antiretroviral therapy or both? Brain Res. 2019, 1724, 146397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.K.; Sarma, A.; Chakraborty, T. Nano-ART and NeuroAIDS. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2016, 6, 452–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, R.; Gaskill, P.J. The role of catecholamines in HIV neuropathogenesis. Brain Res. 2019, 1702, 54–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cody, S.L.; Vance, D.E. The neurobiology of HIV and its impact on cognitive reserve: A review of cognitive interventions for an aging population. Neurobiol. Dis. 2016, 92, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basterfield, C.; Zondo, S. A feasibility study exploring the efficacy of cognitive rehabilitation therapy for paediatric HIV in rural South Africa: A focus on sustained attention. Acta Neuropsychol. 2022, 20, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, M.J.; Busman, R.A.; Parikh, S.M.; Bangirana, P.; Page, C.F.; Opoka, R.O.; Giordani, B. A pilot study of the neuropsychological benefits of computerized cognitive rehabilitation in Ugandan children with HIV. Neuropsychology 2010, 24, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boivin, M.J.; Nakasujja, N.; Sikorskii, A.; Ruiseñor-Escudero, H.; Familiar-Lopez, I.; Walhof, K.; van der Lugt, E.M.; Opoka, R.O.; Giordani, B. Neuropsychological benefits of computerized cognitive rehabilitation training in Ugandan children surviving severe malaria: A randomized controlled trial. Brain Res. Bull. 2019, 145, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benki-Nugent, S.; Boivin, M.J. Neurocognitive complications of pediatric HIV infections. In Neurocognitive Complications of HIV-Infection; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 147–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musielak, K.A.; Fine, J.G. An updated systematic review of neuroimaging studies of children and adolescents with perinatally acquired HIV. J. Pediatr. Neuropsychol. 2016, 2, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Løhaugen, G.C.; Andres, T.; Jiang, C.S.; Douet, V.; Tanizaki, N.; Walker, C.; Castillo, D.; Lim, A.; Skranes, J.; et al. Adaptive working memory training improved brain function in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive patients. Ann. Neurol. 2017, 81, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zondo, S.; Cockcroft, K.; da Silva Ferreira Barreto, C.; Ferreira Correia, A. Shining light into adolescent HIV neuroplasticity: A study of the prefrontal cortex using functional near infrared spectrometry. F1000Research 2025, 14, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, E.W.; Tomé, A.M.; Keck, I.R.; Górriz-Sáez, J.M.; Puntonet, C.G. Brain connectivity analysis: A short survey. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2012, 2012, 412512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahhosseini, Y.; Miranda, M.F. Functional connectivity methods and their applications in fMRI data. Entropy 2022, 24, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K.J. Functional and effective connectivity in neuroimaging: A synthesis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 1994, 2, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Long, Q.; Ernst, T.; Shang, Y.; Chang, L.; Adali, T. Independent component and graph theory analyses reveal normalized brain networks on resting-state functional MRI after working memory training in people with HIV. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2023, 57, 1552–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, B.; Yetkin, F.Z.; Haughton, V.M.; Hyde, J.S. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 1995, 34, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breukelaar, I.A.; Antees, C.; Grieve, S.M.; Foster, S.L.; Gomes, L.; Williams, L.M.; Korgaonkar, M.S. Cognitive control network anatomy correlates with neurocognitive behavior: A longitudinal study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2017, 38, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, V.; D’Esposito, M. The role of PFC networks in cognitive control and executive function. Neuropsychopharmacology 2021, 47, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zondo, S.; Ferreira-Correia, A.; Cockcroft, K. A feasibility study on the efficacy of functional near-infrared spectrometry (fNIRS) to measure prefrontal activation in paediatric HIV. J. Sens. 2024, 2024, 4970794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbole, G.I.; Adeyomoye, A.O.; Badu-Peprah, A.; Mensah, Y.; Nzeh, D.A. Survey of magnetic resonance imaging availability in West Africa. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2018, 30, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joel, S.E.; Caffo, B.S.; van Zijl, P.C.M.; Pekar, J.J. On the relationship between seed-based and ICA-based measures of functional connectivity. Magn. Reson. Med. 2011, 66, 644–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomason, M.E.; Dassanayake, M.T.; Shen, S.; Katkuri, Y.; Alexis, M.; Anderson, A.L.; Yeo, L.; Mody, S.; Hernandez-Andrade, E.; Hassan, S.S.; et al. Cross-hemispheric functional connectivity in the human fetal brain. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 173ra24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toich, J.T.F.; Taylor, P.A.; Holmes, M.J.; Gohel, S.; Cotton, M.F.; Dobbels, E.; Laughton, B.; Little, F.; Van Der Kouwe, A.J.; Biswal, B.; et al. Functional connectivity alterations between networks and associations with infant immune health within networks in HIV infected children on early treatment: A study at 7 years. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Quan, W.; Yang, L.; Chen, J.; Wang, J.; Wu, T. Classification of schizophrenia by seed-based functional connectivity using prefronto-temporal functional near infrared spectroscopy. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2020, 344, 108874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.Q.; Zhou, H.X.; Chen, X.; Castellanos, F.X.; Yan, C.G. Meditation effect in changing functional integrations across large-scale brain networks: Preliminary evidence from a meta-analysis of seed-based functional connectivity. J. Pac. Rim Psychol. 2020, 14, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zondo, S.; Cockcroft, K.; Ferreira-Correia, A. Brain plasticity and adolescent HIV: A randomised controlled trial protocol investigating behavioural and hemodynamic responses in attention cognitive rehabilitation therapy. MethodsX 2024, 13, 102808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ownby, R.L.; Acevedo, A. A pilot study of cognitive training with and without transcranial direct current stimulation to improve cognition in older persons with HIV-related cognitive impairment. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2016, 12, 2745–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ownby, R.L.; Kim, J. Computer-delivered cognitive training and transcranial direct current stimulation in patients with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder: A randomized trial. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 766311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimeo Morais, G.A.; Balardin, J.B.; Sato, J.R. fNIRS Optodes’ Location Decider (fOLD): A toolbox for probe arrangement guided by brain regions-of-interest. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, D.J.; Boot, W.R.; Charness, N.; Gathercole, S.E.; Chabris, C.F.; Hambrick, D.Z.; Stine-Morrow, E.A. Do “brain-training” programs work? Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2016, 17, 103–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, B.J.; Cannonier, T.; Conley, M.I.; Cohen, A.O.; Barch, D.M.; Heitzeg, M.M.; Soules, M.E.; Teslovich, T.; Dellarco, D.V.; Garavan, H.; et al. The adolescent brain cognitive development (ABCD) study: Imaging acquisition across 21 sites. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2018, 32, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bangirana, P.; Idro, R.; John, C.C.; Boivin, M.J. Rehabilitation for cognitive impairments after cerebral malaria in African children: Strategies and limitations. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2006, 11, 1341–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dovis, S.; Van der Oord, S.; Wiers, R.W.; Prins, P.J.M. Improving executive functioning in children with ADHD: Training multiple executive functions within the context of a computer game. A randomized double-blind placebo controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bikic, A.; Leckman, J.F.; Christensen, T.Ø.; Bilenberg, N.; Dalsgaard, S. Attention and executive functions computer training for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): Results from a randomized, controlled trial. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 27, 1563–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L.; Shukla, D.K. Imaging studies of the HIV-infected brain. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018, 152, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoare, J.; Phillips, N.; Joska, J.A.; Paul, R.; Donald, K.A.; Stein, D.J.; Thomas, K.G. Applying the HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder diagnostic criteria to HIV-infected youth. Neurology 2016, 87, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P.M.; Dutton, R.A.; Hayashi, K.M.; Toga, A.W.; Lopez, O.L.; Aizenstein, H.J.; Becker, J.T. Thinning of the cerebral cortex visualized in HIV/AIDS reflects CD4+ T lymphocyte decline. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 15647–15652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, S.; Vink, M.; Joska, J.A.; Koutsilieri, E.; Stein, D.J.; Emsley, R. HIV infection and the fronto-striatal system: A systematic review and meta-analysis of fMRI studies. AIDS 2014, 28, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, B.J.; McDermott, T.J.; Wiesman, A.I.; O’Neill, J.; Mills, M.S.; Robertson, K.R.; Fox, H.S.; Swindells, S.; Wilson, T.W. Neural dynamics of selective attention deficits in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder. Neurology 2018, 91, e1860–e1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribolsi, M.; Daskalakis, Z.J.; Siracusano, A.; Koch, G. Abnormal asymmetry of brain connectivity in schizophrenia. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Z.; Schijven, D.; Francks, C. Patterns of brain asymmetry associated with polygenic risks for autism and schizophrenia implicate language and executive functions but not brain masculinization. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 7652–7660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jajcay, L.; Tomeček, D.; Horáček, J.; Španiel, F.; Hlinka, J. Brain functional connectivity asymmetry: Left hemisphere is more modular. Symmetry 2022, 14, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, E.E.; Zeffiro, T.A. Brain structural changes following HIV infection: Meta-analysis. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2018, 39, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, M.D.; Finn, E.S.; Scheinost, D.; Papademetris, X.; Shen, X.; Constable, R.T.; Chun, M.M. A neuromarker of sustained attention from whole-brain functional connectivity. Nat. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, K.L.; Noudoost, B. The role of prefrontal catecholamines in attention and working memory. Front. Neural Circuits 2014, 8, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.J.; Mackenzie-Phelan, R.; Tully, J.; Schiöth, H.B. Review of the neural processes of working memory training: Controlling the impulse to throw the baby out with the bathwater. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 512761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwasa, J.; Peterson, H.M.; Jones, L.; Karrobi, K.; Parker, T.; Nickerson, N.; Wood, S. Demographic reporting and phenotypic exclusion in fNIRS. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, K.A.; Scheinost, D.; Finn, E.S.; Shen, X.; Constable, R.T. The (in)stability of functional brain network measures across thresholds. Neuroimage 2015, 118, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.L.; Ung, W.C.; Lim, L.G.; Lu, C.K.; Kiguchi, M.; Tang, T.B. Automated thresholding method for fNIRS-based functional connectivity analysis: Validation with a case study on Alzheimer’s disease. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2020, 28, 1691–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.