Featured Application

This methodology has direct application in the advanced dynamic monitoring of indu trial and electrical distribution networks through the use of high-resolution synchronized measurements. Dynamic characterization based on microPMUs complements conventional monitoring infrastructures, enabling the identification of transient phenomena and local dynamic behavior in modern industrial power grids. The proposed approach supports the integration of synchronized measurement platforms for advanced dynamic analysis and near real-time monitoring applications.

Abstract

The growing penetration of power electronics and nonlinear loads in industrial electrical networks has increased the dynamic complexity of these systems, exceeding the analysis capabilities of traditional approaches based on quasi-stationary models. In this context, this paper presents a methodology for the dynamic characterization of an industrial electrical network based on high-resolution synchrophasor measurements obtained using a microPMU. The proposed approach is based on the identification of a linear dynamic model in state space using subspace techniques based on real data recorded during a short-duration transient event. The results show that the identified model is capable of adequately capturing local underdamped dynamics and reproducing the temporal response observed in the measurements. This evidences the presence of dynamic modes associated with the interaction between the network and power electronics-based devices. Similarly, the stability analysis of the identified model demonstrates its consistency and robust gains in temporal variations within the analysis window. Overall, the results confirm that the combination of microPMU and data-based modeling techniques is an effective tool for improving dynamic observability and understanding the transient behavior of industrial power grids, complementing classical analysis and simulation methods.

1. Introduction

The operation and planning of electric power systems are currently undergoing a profound transformation driven by the growing penetration of distributed energy resources, the electrification of demand, and the extensive use of power electronics. This new scenario significantly increases the dynamic complexity of power grids at the transmission and distribution levels, challenging traditional assumptions about the stability, inertia, and quasi-stationary behavior of the electric system. In particular, the progressive replacement of synchronous generation by electronic converters modifies the classic frequency and voltage support mechanisms. This makes it necessary to rethink conventional approaches to dynamic analysis and modeling [1].

One of the most critical aspects in this context is system stability, understood from a comprehensive perspective that includes frequency phenomena, electromechanical oscillations, and rapid dynamics induced by converters. Recent literature shows a renewed interest in reviewing and reevaluating voltage stability concepts, as well as the indices traditionally used for their evaluation, highlighting their strengths and limitations in modern operating scenarios [2,3]. These studies show that many of the historical indicators were developed under assumptions that are now insufficient to describe systems dominated by electronic loads and converter-based generation.

At the same time, an increase has been identified in the occurrence of complex dynamic phenomena such as broadband oscillations, sub-synchronous interactions, and nonlinear behaviors that cannot be adequately captured by traditional RMS models. Recent studies have shown that such oscillations can arise from the interaction between fast controls, converters, and network characteristics. This motivates the use of more detailed modeling approaches with higher temporal resolution [4,5].

In this context, the comparison between transient electromagnetic (TEM) models and phasor (RMS) models has become particularly relevant. Although RMS models continue to be widely used due to their computational efficiency, several studies have shown that they lack the ability to adequately represent system dynamics in networks with high penetration of power electronics, HVDC links, and advanced converters. Recent research has shown that the inappropriate choice of the modeling domain can lead to erroneous conclusions about frequency stability and dynamic system response [6].

In addition, the evolution of electricity demand has introduced new types of loads commonly referred to as emerging loads. These loads are characterized by intensive use of rectifiers, converters, and electronic controls. Data centers, large industrial facilities, and advanced electrified processes are representative examples of these emerging loads, whose internal dynamics can significantly influence the stability of the electrical system. The adequate modeling of this type of load has been recognized as an open challenge and an active area of research [7].

Given this scenario, approaches based exclusively on physical models have practical limitations, especially when dealing with real industrial systems with high complexity, multiple sources of uncertainty, and poorly documented configurations. In response to these limitations, data-driven methodologies have emerged that focus on state estimation, dynamic evaluation, and characterization of system behavior based on real measurements. Recent studies have demonstrated the potential of these approaches to improve the observability and accuracy of analysis in low- and medium-voltage networks [8].

The use of high-resolution synchrophasor measurements, particularly through micro-PMUs, is emerging as a key enabler for this type of analysis. These units allow for the capture of fast dynamic phenomena with significantly higher temporal and angular resolution than conventional measurement systems such as network analyzers, facilitating the identification of local dynamics, interactions between converters, and short-duration transient events. Conventional monitoring infrastructures based on RMS values and network analyzers are often unable to capture fast transient phenomena and local dynamic behavior in modern electrical networks [9]. Recent developments in synchronized measurement technologies and open synchrophasor platforms have enabled enhanced observability and advanced dynamic analysis capabilities, supporting the practical deployment of PMU-based solutions in industrial and distribution systems [10]. However, the correct interpretation of these data requires a rigorous understanding of the uncertainty associated with the measurements, as well as the specific quality metrics for the phasor domain [11].

On the other hand, the growing dependence on automated control and protection strategies, such as underfrequency load shedding, has highlighted the need to evaluate their performance under scenarios with high penetration of distributed generation and unconventional dynamic behavior. In this regard, data-driven approaches have been proposed to analyze the effectiveness and dependencies of these schemes in modern systems [12].

Finally, the impact of large-scale photovoltaic generation continues to be a central issue, especially in relation to voltage stability, dynamic response, and power quality. Recent studies have shown that the effect of these plants cannot be adequately evaluated without considering their dynamic interaction with the grid and other power electronics-based devices [13].

Overall, the reviewed literature reveals a clear gap in methodologies that integrate high-resolution synchrophasor measurements with data-driven dynamic models, particularly in real industrial networks. This work focuses on the need to move towards a more accurate dynamic characterization of this type of system using micro-PMU data to capture and model phenomena that remain hidden under traditional approaches, thus contributing to the understanding and safe operation of modern electrical networks.

In contrast to most existing PMU-based oscillation studies focused on transmission-level systems and low-frequency electromechanical modes, this work addresses the dynamic characterization of a real industrial low-voltage network using synchrophasor measurements with a high reporting rate in the phasor domain obtained from a microPMU. The proposed output-only, data-driven approach enables the identification of local, short-duration underdamped dynamics under naturally occurring disturbances, without relying on detailed physical models or known system inputs.

By combining subspace identification with systematic statistical and modal validation under short observation windows, this study extends current PMU and microPMU-based methods toward the analysis of converter-dominated industrial environments, where intermediate-frequency dynamics play a relevant role during transient voltage recovery.

The article is organized as follows: Section 2, entitled Methodology and System Characterization, describes the proposed approach for the dynamic characterization of the industrial power grid based on high-resolution synchrophasor measurements, including data acquisition using micro-PMUs, the processing and selection of transient events, the formulation of the local dynamic model, and the statistical and modal validation criteria. Section 3 presents the results obtained, addressing the adjustment of the identified model, the statistical validation of residuals, the modal robustness analysis against variations in the time window, and the modal synthesis of the system under study. Section 4 discusses the results in the context of recent literature, analyzing the implications of dynamic modeling based on microPMU data for industrial electrical networks dominated by power electronics. Finally, Section 5 presents the conclusions of the work and suggests possible lines of future research.

2. Methodology and System Characterization

The proposed methodology for the dynamic characterization of the electrical system is based on data-driven approaches and advanced measurements, which have become particularly relevant in modern electrical systems dominated by power electronics, high operational variability, and reduced equivalent inertia. In this context, some studies have shown that traditional dynamic analysis methods based exclusively on physical models and linearization around an operating point have limitations in capturing transient phenomena, weakly damped oscillations, and local dynamics induced by short-duration disturbances [14].

In particular, recent research has shown that data-driven approaches allow for a more flexible and realistic representation of the dynamics of complex electrical systems by directly learning the dynamic behavior from measured time trajectories, without requiring exhaustive knowledge of the topology, electrical parameters, or internal control structures. In this vein, the use of data-learned dynamic formulations, such as those based on neural differential equations, has shown a high capacity to capture the continuous temporal evolution of the system and adequately describe transient responses and nonlinear dynamic phenomena, overcoming the limitations of conventional analytical models [14].

Complementarily, synchrophasor data analysis has been widely recognized as an effective tool for the dynamic characterization of electrical systems, especially for the identification of oscillatory modes and the evaluation of dynamic behavior under both environmental and disturbed conditions. Recent studies based on real synchrophasor measurements have shown that characterization approaches supported by advanced signal processing allow the extraction of relevant dynamic information even in scenarios where classical techniques based on RMS values or time averages are insufficient. These studies also highlight the advantage of measurement-based methods in operating directly on real signals, which makes them particularly suitable for systems with high operational uncertainty and a significant presence of electronically controlled devices [15].

In line with these developments, the methodology adopted in this work is oriented towards the local dynamic characterization of the system based on high-resolution synchrophasor measurements, favoring an output-only approach based on real data, which allows capturing local transient and oscillatory dynamics without resorting to detailed system models or simplifying assumptions that could compromise the fidelity of the dynamic representation.

The methodological approach is designed to leverage real field data to identify and model transient dynamics that are not adequately captured by conventional monitoring schemes based on RMS values, network analyzers, or quasi-stationary approximations.

The methodology begins with the acquisition of synchronized voltage, current, power, and frequency data using a microPMU installed at a strategic point in the industrial power grid. Subsequently, the recorded data undergo a preprocessing stage that includes record cleaning, signal time alignment, and measurement consistency verification. Next, a systematic analysis of the processed signals is performed to identify and select transient events of interest, with an emphasis on those that exhibit oscillatory or underdamped behavior.

Once the transient event has been selected through graphical identification, a local dynamic model of the system is formulated based exclusively on the measured variables. This output-only identification approach allows for an equivalent dynamic representation of the system without requiring detailed information on the network topology, electrical parameters, or internal control structures of the connected devices. Finally, the identified model is subjected to statistical and modal validation processes that allow its consistency, robustness, and ability to capture the dominant dynamics observed in the measured response to be evaluated.

2.1. Data Acquisition with MicroPMU

The microPMU is a portable semi-direct measurement device that uses current transformers and measures voltage directly, as the industrial electrical system is low voltage. The use of high-resolution synchrophasor measurements has established itself as a key enabler for advanced dynamic analysis in modern electrical networks, both in monitoring applications and in the analysis and validation of dynamic models, including the use of real and synthetic data for the development of analytical and control methodologies [16].

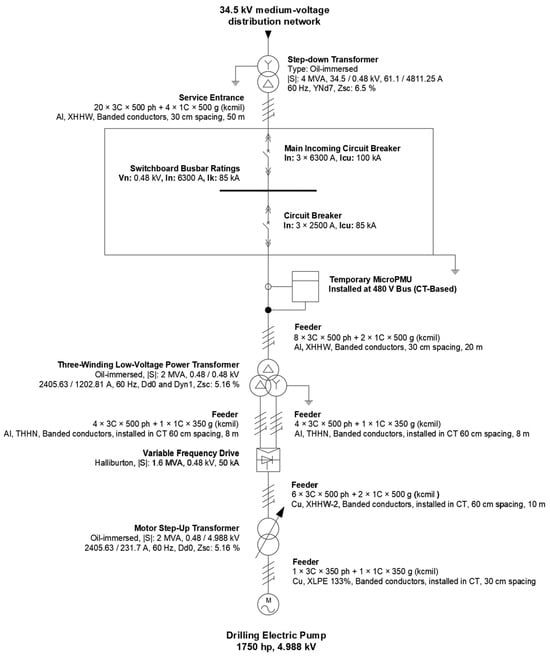

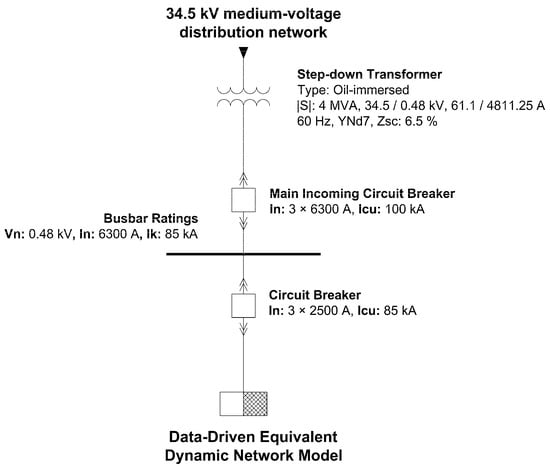

Data acquisition was performed using a microPMU phasor measurement unit (PQube 3, Powerside®, Alameda, CA, USA) installed on the 480 V low-voltage panel of a three-phase busbar with a capacity of 6300 A and a maximum short-circuit current of 85 kA in an industrial electrical system associated with an oil extraction facility, as shown in Figure 1. This instrument, based on the IEEE C37.118 standard [17], records RMS magnitudes, phasor angles, and derived variables with a time resolution of 120 samples per second, ensuring synchronization via GPS signal.

Figure 1.

Single-line diagram of the microPMU connection point in the industrial power grid under study.

The measurements included phase voltages and currents, active, reactive, and apparent power, power factor, and frequency. The records were stored in CSV format, with each file corresponding to one continuous minute of operation, allowing short-duration electrical or mechanical transients to be captured. The data were captured over a period of 29 days from 20 April to 18 May 2025.

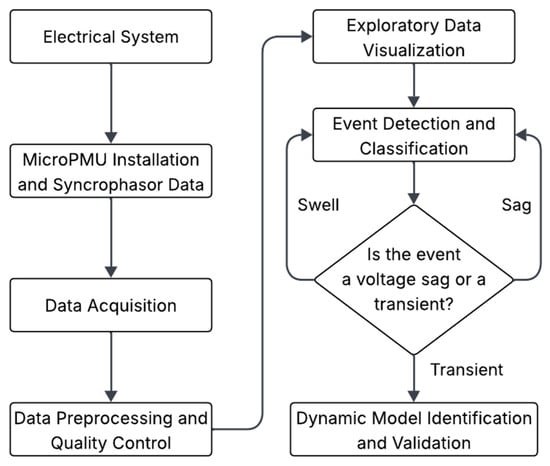

Prior to analysis, the data were verified and cleaned to eliminate redundant headers, incomplete timestamps, and missing values. This allows for temporal consistency between channels. The workflow carried out with the equipment and data processing to obtain the dynamic model is presented in Figure 2. The process begins with the acquisition of high-resolution synchrophasor measurements at a representative point in the industrial power grid, followed by a preprocessing stage aimed at ensuring temporal consistency, record cleansing, and consistency of the measured signals. Based on this processed data, relevant transient events are identified and selected through systematic analysis of the signals, prioritizing those that exhibit dynamic oscillatory behavior. Once the event of interest has been selected using graphical methods, a local dynamic model is formulated using state-space identification techniques under an output-only approach, using only the measured variables. Finally, the identified model is subjected to statistical and modal validation processes in order to evaluate its consistency, robustness, and ability to reproduce the observed dynamics, thus closing a methodological flow oriented towards dynamic characterization based on real field data.

Figure 2.

Workflow diagram for obtaining the dynamic model of the industrial power grid from data taken from the MicroPMU.

2.2. Processing and Selection of Transient Events

The data recorded by the microPMU underwent a review and filtering process to ensure its temporal consistency and relevance for dynamic analysis.

First, the temporal continuity of the files and the correspondence of the timestamps between the three voltage channels were verified. Subsequently, corrupt or incomplete records were removed, and the headers were normalized for direct reading in MATLAB Online (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA).

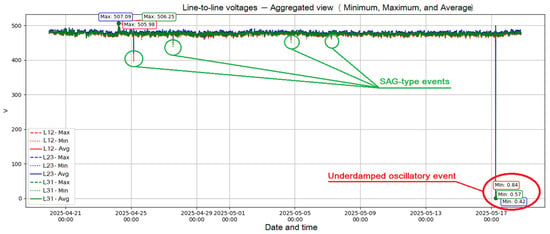

Since the microPMU stores measurements with a sampling frequency of 120 Hz, transient events were detected visually and systematically, as this type of event was not detected or highlighted by the equipment due to the characteristics of the event. The line voltages corresponding to the acquisition period (April–May 2025) are plotted, observing the behavior of the minimum, maximum, and average magnitudes over time using Python (Google Colab Environment).

This procedure allows the identification of different voltage sags (SAGs), characterized by moderate decreases without oscillations or significant dynamic characteristics. In addition, a single event with an evident underdamped response was recorded on 17 May 2025, at 06:13:31. This event presented a transient behavior where line voltages decreased to values close to zero and then recovered their nominal level with a short-duration ripple. This record is an ideal candidate for the identification of a second-order or higher dynamic model.

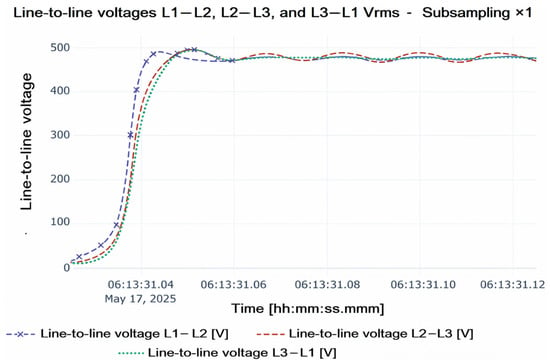

To illustrate the event selection process, Figure 3 shows the overall evolution of line voltages throughout the monitoring period, highlighting SAG events and the oscillatory event of interest with circles. Figure 4 enlarges the time interval of the underdamped event, showing in greater detail the temporal variation of the three line-to-line voltages and the ripple that characterizes the transient. These results constitute the experimental basis on which the time-domain identification techniques were applied.

Figure 3.

Evolution of line voltages recorded by the microPMU during the acquisition period (April–May 2025).

Figure 4.

Details of the underdamped oscillatory event recorded on 17 May 2025, at 06:13:31.

The lines represent the maximum, minimum, and average values of the voltages . The green circles indicate SAG-type events, while the red circle highlights the event with sub-damped oscillatory behavior selected for dynamic modeling.

The drop in line-to-line voltages to values close to zero and their subsequent recovery with transient oscillation can be observed, evidencing the dynamic response of the electrical system.

2.3. Formulation of the Local Dynamic Model

The dynamic representation of the electrical system was developed using a state-space approach because this dynamic systems model allows for the interaction of variables to be represented by identifying them from experimental data obtained directly from microPMU measurements.

Unlike classical physical models derived from equivalent RLC circuits in pre-established configurations, this approach focuses on the dynamic relationships observed between the measured variables, without requiring prior knowledge of the electrical parameters of the network or its loads. In other words, without knowing exactly how the network elements are connected.

This type of representation is particularly suitable in systems dominated by electronic converters where detailed physical models may be incomplete or unrepresentative of the actual dynamics, and where approaches inspired by concepts of virtual synchronization and equivalent behavior to synchronous machines have been widely discussed in recent literature [18].

The three-phase system was modeled considering the three-line voltages as output variables, grouped in the vector as shown in Equation (1)

In this case, there are no controlled physical input signals available because they respond to the actual behavior of the industrial power grid supply system. An output-only identification scheme was adopted, in which the internal dynamics of the system are described by a set of abstract states. Therefore, the discrete linear model in state space is expressed in Equations (2) and (3).

where

- is the internal state vector, representing the dynamic evolution of variables not directly observed;

- is the noise or disturbance vector associated with the measurement;

- A, C, and K are the experimentally identified matrices of the discrete model.

This model allows the local dynamic behavior of the electrical system during a transient event to be captured, using only the measured voltages as observables.

The result is a representation capable of reproducing the observed oscillations without relying on explicit physical parameters. These types of models allow the adjustment of parameters in industrial or distribution electrical networks that have high harmonic content due to the presence of nonlinear loads such as variable speed drives or networks impacted by mass electric mobility [19]. This allows the design parameters of these networks to be adjusted and opens up a very interesting window of research for the optimization of flexible operating limits in these networks.

The dynamic model identified in this work is not intended to replace traditional physical models used in load flow studies or electromagnetic simulations. Instead, it provides a local dynamic representation of the electrical system obtained directly from high-resolution synchrophasor measurements. This model allows real dynamic behaviors that are not explicitly considered in quasi-stationary approaches to be captured and analyzed and acts as a complement to classic RMS and EMT studies.

2.4. Subspace Identification (N4SID)

The estimation of the A, C, and K matrices was performed using the N4SID subspace identification technique, widely used for the identification of linear systems in the time domain. This method allows the dominant dynamics of a system to be obtained directly from the measured outputs without requiring a prior physical model or structural assumptions about the number or type of internal states.

The applicability of this type of technique is particularly relevant in modern distribution and industrial networks, where increasing operational complexity and the need to exploit dynamic operating margins have led to the use of advanced dynamic analysis and corrective control tools. These depend critically on reliable dynamic models [20].

The procedure was applied over a time window of approximately 400 milliseconds centered on the identified oscillatory event. The signals were previously cleaned and centered by removing their average in order to preserve only the dynamic component of the transient.

The N4SID algorithm constructs delay matrices from the output signals and, using singular value decomposition (SVD), determines the dimension of the dominant subspace associated with the system dynamics. From this subspace, the matrices A, C, and K are estimated that minimize the quadratic error between the measured and estimated outputs.

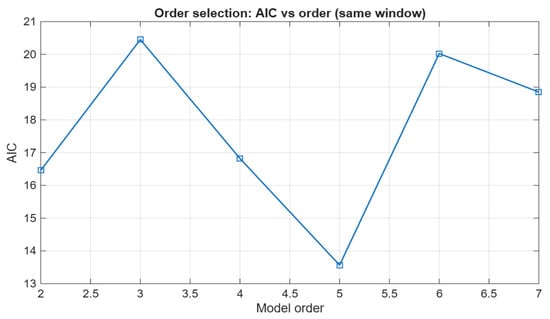

The order of the model was determined by analyzing the variation in the fit and the AIC information criterion for orders between 3 and 10. The order that offered the best compromise between fidelity and complexity was selected as the nominal model. With this model, the continuous and discrete representations used later for modal analysis were constructed. Finally, the equivalent dynamic model of the industrial electrical network under test is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Location in the single-line diagram of the equivalent dynamic model of the industrial electrical network.

2.5. Statistical and Modal Validation

The validation of the identified dynamic model was carried out through a set of three complementary stages, designed to evaluate its statistical consistency, dynamic fidelity, and robustness against temporal variations in the analysis interval. First, a residual analysis was performed to verify that the model errors did not show significant correlations and behaved as a white noise process, a necessary condition to ensure that the deterministic dynamics of the system were adequately captured. Second, the order of the model was evaluated by comparing different candidate orders, simultaneously analyzing the model fit and the Akaike information criterion (AIC), with the aim of selecting a parsimonious and numerically stable representation. Finally, a temporal robustness test was carried out, in which the identification process was repeated by shifting the analysis window around the transient event, with the purpose of evaluating the sensitivity of the natural frequencies and damping factors to variations in the observation interval. The details of each of these stages are presented below.

- Residual analysis.

The autocorrelation of the model residuals in the time domain was evaluated, verifying that they behaved as a white noise process without significant residual correlations. This condition ensures that the model correctly reproduces the deterministic structure of the system and that errors are due solely to noise or unmodeled effects.

This type of validation is especially relevant in systems dominated by converters with droop control strategies, where transient stability and correct damping of dynamic modes depend heavily on the control parameters and operating conditions of the system [21].

- 2.

- Model order evaluation.

The results obtained for different system orders were compared, observing the evolution of the fit (expressed as a percentage) and the AIC criterion. The final order was selected based on the convergence of both indicators, ensuring that the model was parsimonious and numerically stable.

- 3.

- Temporal robustness test.

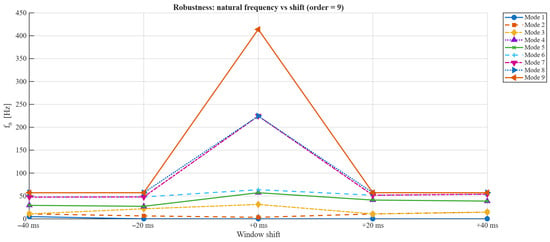

The identification process was repeated by shifting the time window of analysis ±20 ms and ±40 ms with respect to the central event. The consistency of the natural frequencies () and damping factors () obtained in each case allowed the sensitivity of the model to variations in the observation interval to be evaluated.

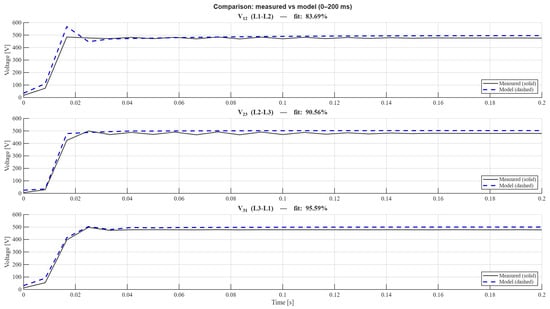

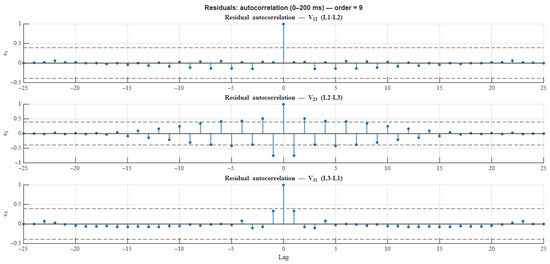

The quantitative results and graphical representations associated with these validations are presented in Section 3, specifically in Figure 6 and Figure 7, together with the physical interpretation of the identified dynamic modes.

Figure 6.

Comparison between measured voltages and the identified model in the 0–200 ms interval for .

Figure 7.

Autocorrelation of residuals from the identified model (order 9) for outputs .

2.6. Output-Only Identification and Reproducibility Setting

The identification problem was formulated as an output-only (time-series) model using three measured outputs: the phase-to-ground RMS fundamental voltage magnitudes. A fixed event window of 200 ms was used for all methods, defined as [0, 0.2] s with respect to the first sample of the record. The sampling period was dt = 8.3333, resulting in N = 25 samples in the identification window. Prior to estimation, each output was mean-removed (removeMean = 1), with no detrending and no normalization.

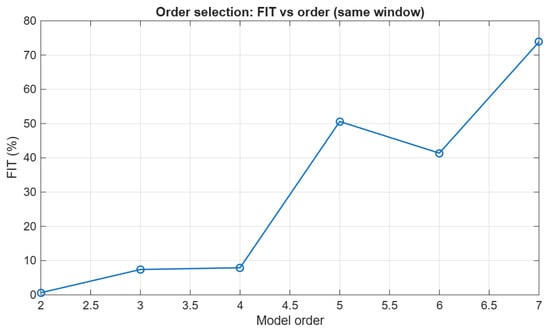

Subspace identification was performed using N4SID in output-only mode. The block-Hankel horizon (block rows) was set to 20, 20 and candidate model orders were tested in the range n = {2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7}. Order selection was supported by quantitative criteria FIT and AIC computed under identical windowing and preprocessing conditions, and by residual whiteness diagnostics based on the residual autocorrelation function ACF up to lag 30 with the significance level at α = 0.05. The selected model order for the reported results was n = 7.

3. Results

This section presents the results obtained from the application of the proposed methodology for the dynamic characterization of the industrial electrical system under study. The results cover both the analysis of the synchrophasor signals measured during selected transient events and the formulation and validation of the local dynamic model identified from these data. In particular, the model’s ability to reproduce the observed dynamic response is evaluated, the statistical consistency of the residuals is analyzed, and the robustness of the modal y behavior is examined in the face of variations in the identification time window. Likewise, metrics are presented that allow for the assessment of the quality of the fit and the dynamic representativeness of the model obtained, laying the foundations for its interpretation and discussion in the context of industrial electrical systems dominated by power electronics.

3.1. Fitting the Identified Model

Although multiple electrical quantities were recorded by the microPMU during the analyzed event, the dynamic identification was intentionally based on three-phase voltage measurements. Voltage signals exhibit a higher signal-to-noise ratio and a more direct relationship with the underlying grid dynamics, while power-related quantities (P, Q, S, and power factor) are derived variables that introduce additional nonlinearities and measurement uncertainty, which degrade the performance of linear identification models.

For completeness, dynamic models were also estimated for current, frequency, and power-related variables. As summarized in Table 1, the dominant oscillatory modes identified from voltage measurements consistently appear across the additional channels, although with lower fitting accuracy and reduced robustness. This confirms that the identified modes represent system-level dynamics rather than signal-specific artifacts, while justifying the selection of voltage as the primary variable for model identification.

Table 1.

Comparison of dominant dynamic modes across measured variables.

Figure 6 shows the comparison between the voltages measured by the microPMU and those reconstructed by the discrete model identified in the window from 0 to 200 ms. The model adequately reproduces the recovery time, final amplitude, and transient ripple observed after the voltage drop.

The quantitative adjustments calculated using the NRMSE indicator were the channel-wise NRMSE-based fits, exceeding 80% for and 90% for , while the corresponding multi-output FIT of the identified model remains above 75%, as reported in Table 1. This shows a good correspondence between the measured and simulated responses. This consistency confirms that the 9th-order linear model accurately captures the dominant dynamics of the event.

3.2. Model Order Selection and Quantitative Validation

A quantitative assessment of model complexity was carried out by comparing discrete-time state-space models of increasing order identified from the same oscillatory voltage event. Model orders ranging from 2 to 12 were evaluated using prediction accuracy on a validation segment and residual autocorrelation tests. The main quantitative results of this comparison are summarized in Table 2, which reports the model order, prediction fit, residual behavior, and a qualitative interpretation of the identified dynamics.

Table 2.

Quantitative benchmark against lower-order models (voltage).

Low-order models exhibit clear underfitting, as evidenced by poor prediction accuracy and the inability to capture the dominant oscillatory behavior. Increasing the model order improves the representation of the measured response, with higher orders yielding better predictive performance. However, beyond a certain complexity level, the improvement becomes marginal and may be accompanied by reduced robustness due to limited excitation in the short-duration event. Based on this trade-off, a model order of 9 is adopted as a parsimonious representation that satisfies the required validation criteria while reliably capturing the dominant system dynamics.

3.3. Statistical Validation of Residuals

In order to verify that the model structure does not leave any relevant dynamics uncaptured, the autocorrelation of the residuals was analyzed in the same 0–200 ms interval. Figure 7 shows that most correlations remain within the 95% confidence bands, indicating behavior close to white noise. This result supports the statistical validity of the model and suggests that the main dynamics were correctly identified.

3.4. Order Selection Evidence

Figure 8 and Figure 9 report the order-selection evidence for the N4SID models evaluated under identical windowing. The FIT metric increases notably for higher orders within the tested range, while the AIC criterion attains its minimum at order 5 and then increases. Considering the combined evidence (FIT/AIC trade-off) and the residual diagnostics, we selected order 7 for subsequent modal interpretation and baseline comparison.

Figure 8.

N4SID order-selection evidence: FIT (%) versus model order for the output-only voltage dataset under the 200 ms event window.

Figure 9.

N4SID order-selection evidence: AIC versus model order under the same 200 ms window and preprocessing.

3.5. Modal Robustness to Window Variations

Figure 10 presents the modal robustness analysis obtained by repeating the identification by shifting the analysis window by . The natural frequencies and the damping factors ζ estimated for each shift remained within a stable range, with standard variations of less than 15% for the most significant modes. The dominant modes were concentrated between 40 and 60 Hz, which corresponds to the oscillations associated with the three-phase system during voltage recovery.

Figure 10.

Robustness of natural frequencies versus window displacements ().

3.6. Modal Synthesis

Table 3 summarizes the natural frequencies and damping factors identified for the equivalent continuous model, together with the deviations obtained in the robustness analysis. Modes 4 to 6, located between 38 and 55 Hz, present intermediate damping (0.3 < ζ < 0.4) and are associated with the oscillatory response observed in the event. The higher frequency modes (>80 Hz) are interpreted as numerical components or residual noise effects.

Table 3.

Natural frequencies and damping factors identified from the equivalent continuous model.

3.7. Interpretation

The analysis shows that the underdamped event revealed the intrinsic dynamics of the three-phase system with intermediate frequency modes associated with the restoration of energy balance between phases. Modal consistency in the face of window changes and residual whiteness confirms the stability of the identified model.

These results validate the potential of data-based identification (N4SID) applied to microPMU measurements to characterize local events in industrial networks even without an explicit physical model.

3.8. Baseline Comparison Under Identical Windowing

To assess the incremental value of N4SID in this setting, we compared it against two baseline methods under the same 200 ms window and identical preprocessing: (i) a multivariable ARX model (VARX form) estimated in output-only configuration (nb = 0, nk = 0) with the same nominal order, and (ii) a DMD-like one-step predictor baseline (rank selected by a 99.9% energy threshold). Model quality was evaluated using (a) the multi-output FIT metric obtained from one-step-ahead prediction, and (b) residual whiteness based on the residual ACF.

Table 4 summarizes the comparison for the chosen order n = 7. N4SID achieved a FIT of 73.85% with a residual whiteness score of 0.9778, while the ARX (MIMO) baseline produced a higher predictive FIT (99.19%) with a similar whiteness score (0.9778). The DMD-like baseline reached a lower FIT (63.71%) but exhibited the highest whiteness score (1.0). Importantly, beyond predictive accuracy, N4SID provides a state-space realization suitable for modal interpretation; in the selected model, the dominant mode within 40–60 Hz was estimated at 56.78 Hz with damping ratio ζ = 0.0358, enabling a physically interpretable dynamic characterization that is not directly available from the predictor-only baselines.

Table 4.

Baseline comparison under identical 200 ms windowing and preprocessing (mean removal). Metrics include multi-output FIT (%), residual whiteness score (fraction of residual ACF lags within the α = 0.05 bounds), and dominant mode estimates (when available).

3.9. Advantages of Dynamic Modeling Based on MicroPMU Data

The results obtained in this work demonstrate the advantages of dynamic modeling based on microPMU data compared to traditional approaches based on physical models. Unlike conventional RMS or EMT models, which require detailed parameterization of electrical equipment and their control systems, the proposed approach allows the actual dynamic behavior of the system to be captured directly from field measurements.

In industrial environments, complete information on electrical and control parameters is often limited, confidential, or subject to uncertainty. In this context, microPMU-based identification eliminates the reliance on simplifying assumptions because the dynamic model is obtained from the actual response of the system to transient events, implicitly incorporating the interaction between the electrical network, transformers, power converters, motor load, and other elements of the industrial electrical network.

The identified models reproduce with high accuracy the transient responses measured in the 0 to 200 ms window. This demonstrates their ability to represent the local dynamics excited by real disturbances. In addition, the dominant modes identified in the 35 to 60 Hz range remain consistent across shifts in the analysis time window. This demonstrates the robustness of the identification process and the stability of the extracted modal content.

Another relevant advantage of the microPMU-based approach is its temporal resolution and synchronization. Unlike conventional monitoring systems, such as SCADA, RMS recorders, or network analyzers, microPMUs allow for the observation of sub-second dynamics that are critical in systems with high power electronics penetration. This enables the identification of oscillatory modes associated with converters and their interaction with the network, phenomena that are often underrepresented or directly ignored in classical models.

From a practical standpoint, the proposed method can be applied by temporarily installing measurement equipment, without interfering with normal system operation, thanks to its portability and without the need to model the entire electrical network. This makes dynamic modeling based on microPMUs a particularly suitable tool for diagnostic, validation, and dynamic characterization studies in real operating systems.

The results obtained in this work show that dynamic models identified from high-resolution synchrophasor measurements are a relevant contribution to the development of cyber–physical systems applied to industrial electrical networks. In particular, the ability to capture local system dynamics using models based on real data allows for the establishment of a dynamic representation that is consistent between the physical behavior of the system and its computational counterpart, a fundamental element in cyber–physical architectures geared toward advanced monitoring, dynamic analysis, and decision-making support.

In this context, the identified local dynamic model can be interpreted as a functional block within a digital twin of the electrical system, insofar as it reproduces the dynamic response observed in the face of real disturbances and is updated directly from field measurements. Unlike traditional digital twin approaches based exclusively on detailed physical models, the approach presented allows for the incorporation of dynamic information implicit in the data, reducing dependence on parameters that are difficult to obtain and improving the representativeness of the actual behavior of the system under variable operating conditions.

Likewise, the use of microPMU measurements as the primary source of information facilitates the integration of the identified model into continuous monitoring and near real-time analysis schemes, enabling applications aimed at early detection of dynamic changes, local stability assessment, and analysis of interaction between electronically controlled elements. In this sense, the results presented lay the foundation for the implementation of local digital twins, where the data-based dynamic model acts as a link between the physical system and its digital representation within a cyber–physical architecture.

Taken together, the results show that dynamic modeling based on microPMU data should be understood as a complement to traditional methods of electrical system analysis, providing experimental and localized information on the actual dynamic behavior of the system that is particularly valuable in scenarios where detailed physical models are not available or are difficult to implement.

3.10. Limitations and Scope of Applicability

The dynamic model was identified from a short-duration oscillatory transient naturally occurring in the system. It is important to note that the identification of electromechanical or electromagnetic modes requires sufficient excitation energy; therefore, only events exhibiting clear oscillatory behavior can be used for reliable modal estimation.

During the analyzed measurement period, no additional events with comparable oscillatory content were observed. This indicates that the system operates predominantly in a stable regime, where dynamic modes are not sufficiently excited for identification. Consequently, the proposed model represents the system dynamics around the operating condition associated with the analyzed event and should not be interpreted as a universal model valid for all operating points.

The limited number of suitable events reflects a practical constraint of data-driven identification based on passive measurements in real-world power systems rather than a limitation of the proposed methodology.

Modes consistently appearing across window shifts and measurement channels, with limited variance in frequency and damping, were classified as physical, while modes exhibiting high sensitivity or appearing above 80 Hz were treated as numerical artifacts.

4. Discussion

The results obtained in this work show that the high-resolution synchrophasor measurements provided by a microPMU allow the capture of local dynamics of the industrial electrical system that remain hidden under conventional RMS-based monitoring schemes. In particular, the underdamped event analyzed, with a duration of approximately 200 ms, reveals the presence of clearly identifiable oscillations in the range of 35 to 60 Hz with positive but moderate damping factors. This evidences the excitation of local dynamic modes induced by short-duration disturbances. This behavior is consistent with previously reported dynamics in grid-following converters subjected to sub-synchronous voltage fluctuations [5].

The observed oscillatory response can be interpreted as the aggregate result of multiple control loops acting simultaneously, including electronic converters, variable speed drives, and nonlinear industrial loads. The identified dynamic model reproduces the measured response with a fit consistently above 75%, which is in agreement with the quantitative results reported in Section 3 and confirms that the dominant dynamics of the event are adequately captured for the three-line voltages analyzed within the 0 to 200 ms window and shows that the dominant dynamics of the system are effectively captured by the equivalent state-space model. Recent studies have shown that even in apparently stable systems, the interaction between fast controls and network characteristics can induce damped or weakly damped oscillations whose detection requires high temporal resolution instrumentation [22].

From the perspective of grid-forming converter control, several studies have highlighted the critical role of parameters such as virtual impedance in shaping the dynamic response of the system. In particular, it has been shown that the choice of these parameters can substantially modify both the damping and the natural frequency of the dominant modes [23]. Although the system analyzed in this study does not explicitly implement grid-forming strategies, the modes identified with natural frequencies concentrated around typical converter–grid interaction values suggest equivalent dynamics strongly influenced by electronic controls and the effective impedance of the industrial grid.

Additionally, the stability of converter-dominated systems has recently been addressed using advanced analytical tools such as Lyapunov analysis supported by sum-of-squares optimization techniques, demonstrating the growing interest in rigorously characterizing the stability of this type of system [24]. In this context, the dynamic model identified in this work offers a complementary approach, based exclusively on real data, which allows direct observation of the system’s response to disturbances without resorting to detailed physical models or simplifying assumptions about internal control loops.

The data-driven approach adopted is in line with recent trends that seek to integrate physical knowledge and measured data to improve the interpretation of system dynamics. In particular, methods such as Physics-Informed Neural Networks have been proposed to incorporate physical constraints into machine learning-based models applied to grid-connected converters [25]. Although this work does not employ deep learning techniques, the subspace identification performed demonstrates that even moderate-order linear models (order 8–9) obtained directly from data can capture relevant dynamic information when high-quality synchrophasor measurements are available.

On the other hand, the use of real data from an industrial facility introduces challenges similar to those reported in studies on state and topology identification under limited measurement conditions. Recent research has shown that, in real distribution networks, measurement scarcity or uncertainty can be mitigated through probabilistic and data-driven approaches [26]. In this regard, this work demonstrates that, even with a single microPMU measurement point, it is possible to extract meaningful dynamic information from the system, as evidenced by the modal consistency observed under time shifts of up to ±40 ms in the analysis window.

Likewise, the literature has demonstrated the potential of synchrophasor measurements not only for monitoring but also for real-time control applications. Studies on the control of energy storage systems based on synchrophasors have shown that phasor information allows for the design of control strategies that are more robust against disturbances and variable grid conditions [27]. The results of this work reinforce this view by showing that the dynamics captured by the microPMU contain key information on damping and dominant frequencies that could be exploited in future advanced control and monitoring applications.

Finally, although the approach presented focuses on dynamic characterization rather than automatic event detection, the results are directly related to recent work on robust detection of islanding events in microgrids. These studies have highlighted the importance of capturing both transient and stationary characteristics for reliable event classification [28]. In this sense, the dynamic modes identified in this work could serve as a basis for the future development of hybrid schemes for dynamic characterization and event detection in industrial networks.

Overall, this discussion highlights that dynamic characterization based on microPMU data constitutes an effective bridge between recent theory on the stability and control of converter-dominated systems and the operational reality of industrial electrical systems. The proposed approach complements existing analytical and simulation methods by providing quantitative experimental evidence of real dynamics that must be considered in the design, operation, and monitoring of modern electrical networks.

5. Conclusions

This paper presented a methodology for the dynamic characterization of an industrial electrical network based on high-resolution synchrophasor measurements obtained using a microPMU. Using real data recorded during normal operation, it was possible to identify and model local transient dynamics that are not captured by traditional monitoring approaches based on RMS values or time averages.

The results confirm that microPMUs are a key tool for advanced dynamic analysis in modern electrical systems, particularly in industrial environments with high penetration of power electronics and nonlinear loads. This finding is consistent with recent developments aimed at facilitating the use, processing, and experimentation with synchrophasor data through open platforms and rapid prototyping tools, which seek to bridge the gap between measurement and practical application in electrical system analysis and control [29].

The dynamic model identified from the microPMU data allowed us to capture underdamped modes associated with the interaction between the grid and the electronic devices present in the installation. This result reinforces the idea that the dynamics observed in converter-dominated systems are strongly influenced by effective control parameters and system impedance, even when these are not explicitly known. Recent studies on sensitivity analysis in grid-forming control schemes have shown that variations in parameters such as droop and virtual inertia can significantly modify the stability and damping of the dominant modes [30]. This highlights the value of having dynamic models obtained directly from real measurements.

The observed underdamped response arises from the interaction between fast converter control loops and the effective network impedance during voltage recovery. Although the microPMU provides phasor-domain measurements, its 120 Hz reporting rate is sufficient to resolve oscillatory dynamics in the 40–60 Hz range, which are well below the Nyquist limit. The identified modes, therefore, reflect physical electrodynamic interactions rather than artifacts of digital sampling or phasor estimation.

From an applied perspective, the proposed methodology provides a solid basis for the development of future applications in advanced monitoring, dynamic diagnostics, and validation of control strategies in industrial electrical systems. The data-driven approach complements existing analytical and simulation methods by providing direct experimental evidence on the actual dynamic behavior of the system under short-duration disturbances.

The results obtained in this work demonstrate that dynamic characterization based on high-resolution synchrophasor measurements is a robust tool for the development of dynamic models oriented towards cyber–physical systems in industrial electrical networks. The proposed approach allows local system dynamics to be captured from real data, without requiring detailed physical models or complete information on topology or electrical parameters, which is particularly relevant in complex industrial environments dominated by power electronics.

In this sense, the dynamic models identified from microPMU data can be interpreted as fundamental components of local digital twins, providing a coherent dynamic representation between the physical system and its digital counterpart. This approach enables future applications associated with advanced dynamic monitoring, continuous assessment of local stability, and early detection of changes in the dynamic behavior of the system, laying the foundation for data-driven cyber–physical architectures updated from field measurements.

Finally, this work demonstrates that the integration of microPMU measurements with data-driven dynamic identification techniques represents a viable and promising path to improving the understanding and operation of modern electrical networks. Future lines of research include extending the analysis to multiple events and measurement points, as well as integrating the identified dynamic model into real-time testing and control platforms in order to evaluate its performance under more complex and realistic operating scenarios, in line with current trends in open tools and advanced control of electrical systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.R.A. and R.I.-R.; methodology, R.I.-R. and R.I.-R.; software, J.C.R.A.; validation, J.C.R.A. and J.R.-G.; formal analysis, J.C.R.A.; investigation, J.C.R.A. and J.R.-G.; resources, R.I.-R.; data curation, J.C.R.A.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.R.A.; writing—review and editing, J.C.R.A. and J.R.-G.; visualization, J.C.R.A.; supervision, J.R.-G.; project administration, J.R.-G. and R.I.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Electrical Machines and Drives (EM&D) from Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Energy Solutions Cooperation Network for Communities, code: 59384.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to confidentiality agreements with the industrial facility where the measurements were obtained.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the technical support provided during the measurement campaign and data acquisition process from CEN&T. The authors used DeepL to translate from Spanish to English. All outputs were reviewed and verified by the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| microPMU | Micro Phasor Measurement Unit |

| PMU | Phasor Measurement Unit |

| RMS | Root Mean Square |

| EMT | Electromagnetic Transients |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| N4SID | Numerical Subspace State-Space System Identification |

| CSV | Comma-Separated Values |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| NRMSE | Normalized Root Mean Square Error |

| SAG | Voltage Sag |

| SCADA | Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition |

| DER | Distributed Energy Resources |

| RES | Renewable Energy Sources |

| HVDC | High Voltage Direct Current |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| TVE | Total Vector Error |

| SVD | Singular Value Decomposition |

| GFM | Grid-Forming |

| GFL | Grid-Following |

References

- Sami ur Rehman, S.M.; Lens, H. A Novel Limited Grid-Forming Strategy to Support Power System Stability under Primary Energy Source Limitations. IFAC PapersOnLine 2024, 58, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, F.H.; Khan, M.W.; Rahman, T.U.; Ehtisham, M.; Faheem, M.; Haider, Z.M.; Lehtonen, M. A Comprehensive Review on Voltage Stability in Wind-Integrated Power Systems. Energies 2024, 17, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, M.S.S.; Senjyu, T.; Danish, S.M.S.; Sabory, N.R.; Narayanan, K.; Mandal, P. A recap of voltage stability indices in the past three decades. Energies 2019, 12, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, X.; Wang, D.; Wen, T.; Zhou, Z.; Sun, L.; Yang, B. Analysis and Mitigation of Wideband Oscillations in PV-Dominated Weak Grids: A Comprehensive Review. Processes 2025, 13, 3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grüger, B.; Steinke, F.; Jamal, A.; Griepentrog, G. Grid-following Converter Dynamics under Large Sub-synchronous Voltage Fluctuations. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Kiel PowerTech, Kiel, Germany, 29 June–3 July 2025; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, S.; Hebing, A.; Pfendler, A.; Sturm, N.; Xiao, X.; Hanson, J. Frequency Stability and Fast Frequency Response in Hybrid AC-DC Transmission Grids: A Comparative Study of EMT and RMS Modeling Approaches. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE PowerTech, Kiel, Germany, 29 June–3 July 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrovic, A.; Strezoski, L.; Loparo, K.A. Doubly Fed Induction Machine Models for Integration into Grid Management Software for Improved Post Fault Response Calculation Accuracy—A Short Review. Energies 2025, 18, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, J.; Ellger, L.; Mora, E.; Duckheim, M.; Niessen, S. Assessing data-driven state estimation performance in low-voltage distribution grids. IET Conf. Proc. 2025, 2025, 1333–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rind, Y.M.; Raza, M.H.; Zubair, M.; Mehmood, M.Q.; Massoud, Y. Smart Energy Meters for Smart Grids, an Internet of Things Perspective. Energies 2023, 16, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carducci, C.G.C.; Pau, M.; Cazal, C.; Ponci, F.; Monti, A. SMU Open-Source Platform for Synchronized Measurements. Sensors 2022, 22, 5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingotti, A.; Costa, F.; Peretto, L.; Tinarelli, R. Closed-form expressions to estimate the mean and variance of the total vector error. Energies 2021, 14, 4641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ETG-Fb. 174: Transformation der Stromversorgung—Netzregelung und Systemfuhrung; VDE Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kiangebeni Lusimbakio, K.; Boketsu Lokanga, T.; Sedi Nzakuna, P.; Paciello, V.; Nzuru Nsekere, J.-P.; Tshimanga Tshipata, O. Evaluation of the Impact of Photovoltaic Solar Power Plant Integration into the Grid: A Case Study of the Western Transmission Network in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Energies 2025, 18, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Liu, E.; Wu, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, M. Neural ODE-Based Frequency Stability Assessment and Control of Energy Storage Systems. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lala, J.O.; Garzón, N.O.; Mora, H.C.; Echeverria, D.; Vega-Sánchez, J.; Ohishi, T. Characterization of Power System Oscillation Modes Using Synchrophasor Data and a Modified Variational Decomposition Mode Algorithm. Energies 2025, 18, 2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso Toro, F.; Frigo, G. Synthetic PMU Data Generator for Smart Grids Analytics. Metrology 2025, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Standard C37.118.1-2011; IEEE Standard for Synchrophasor Measurements for Power Systems. IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2011.

- Quintero-Durán, M.J.; Candelo-Becerra, J.E.; González-Niño, M.E.; Hernández-Moreno, S.A.; Váz, R.F. Synchronverter Control Strategy: A Review of Different Improvements and Applications. Energies 2025, 18, 3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acero, J.C.R.; Ruget, R.I.; García, J.R. Impact of Mass Electric Mobility on the Power Distribution Network: Case Study of San Andrés Island, Colombia. Int. Rev. Model. Simul. 2025, 18, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaarschmidt, K.; Schön, A.; Heid, J.; Wiemer, J.; Fabian, T.; Bornhorst, N. Transferring Curative System Operation Principles to Distribution Systems: Practical Insights into Opportunities and Challenges. In Proceedings of the ETG Kongress 2025 (ETG Fb. 176); VDE Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2025; ISBN 978-3-8007-6494-5. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Hua, L.; Guo, Q.; Li, C.; Chen, K. Transient Stability Control Method for Droop-Controlled Photovoltaics, Based on Power Angle Deviation Feedback. Energies 2025, 18, 5126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fose, N.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Moodley, P. Improved Control Technique for Enhancing Power System Stability in Out-of-Step Conditions. Energies 2024, 17, 4086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, L.; Hebing, A.; Pfendler, A.; Hanson, J. Influence of a virtual impedance on the dynamic behavior of the grid-forming control of inverter-based generation plants. IET Conf. Proc. 2025, 2025, 925–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xiao, X.; Hebing, A.; Jia, Y.; Choudhury, S.; Hanson, J. Lyapunov Stability Analysis of Grid Forming Converters Using Sum of Squares Optimization. In Proceedings of the IET Conference on Power Electronics, Machines and Drives (PEMD 2025); IET: London, UK, 2025; pp. 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mahdouri, E.; Al-Abri, S.; Yousef, H.; Al-Naimi, I.; Obeid, H. Physics-Informed Neural Networks in Grid-Connected Inverters: A Review. Energies 2025, 18, 5441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, L.; Stursberg, P.; Metzger, M.; Hofbauer, P.; Erhard, S.; Niessen, S. Probabilistic Switch State Identification Based on Scarce Grid Measurements: A Case Study on German Distribution Grids. In ETG-Fb. 176: ETG Kongress 2025; VDE Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2025; ISBN 978-3-8007-6494-5. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, P.M.; Vanfretti, L.; Chang, H.; Kar, K. Real-Time Control of a Battery Energy Storage System Using a Reconfigurable Synchrophasor-Based Control System. Energies 2023, 16, 6909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akıl, Y.; Boynuegri, A.R.; Yilmaz, M. Robust Detection of Microgrid Islanding Events Under Diverse Operating Conditions Using RVFLN. Energies 2025, 18, 4470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudette, M.; Vanfretti, L.; Tyagi, S. S3DK: An Open Source Toolkit for Prototyping Synchrophasor Applications. Electronics 2024, 13, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebing, A.; Jung, L.; Hanson, J. Sensitivity Analysis of a Grid-Forming Droop Control System for Power Converters. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Kiel PowerTech, Kiel, Germany, 29 June–3 July 2025; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.