Abstract

China’s roof-cutting and pressure relief gob-side entry retaining (RCPR-GER) technology provides an efficient non-pillar mining solution that significantly enhances coal recovery. This paper presents a systematic review of the technological progress in Chinese coal mines from 2011 to 2023, based on an analysis of 1038 publications from CNKI, EI, and Web of Science using VOS viewer and Origin software. Four main technical approaches are examined: gob-side entry retaining without roadside filling, with roadside filling, with roof-cutting and pressure relief, and hybrid methods. Five key roof-cutting techniques are evaluated: dense drilling, high-pressure water-jet slotting, hydraulic fracturing, blasting, presplitting, and roof water injection softening. Successful applications have been documented in coal seams with thicknesses of 1.6–6.15 m and burial depths of 92–1037 m, demonstrating wide adaptability. The roof-cutting short-beam theory underpins the mechanism, which reduces roadway deformation, shortens the cantilever beam length, and alters stress transfer paths. Compared to previous reviews on general gob-side entry retaining, this study offers a dedicated synthesis and comparative analysis of RCPR-GER technologies, establishing a selection framework grounded in geological compatibility and engineering practice. Future research should focus on adaptive parameter design for deep hard composite roofs, quantitative modeling of passive roof-cutting effects, optimization of cutting timing and orientation, and floor-heave control technologies to extend applications under complex geological conditions.

1. Introduction

Coal mining operations worldwide are increasingly challenged by the depletion of shallow resources and the transition to deep extraction, with China exemplifying this trend through an average mining depth increase of 8–12 m annually [1,2,3]. Traditional coal pillar mining methods, while historically effective, result in substantial resource waste with pillar recovery rates typically below 60%, creating significant economic and environmental concerns [4]. Consequently, the development of non-pillar mining technologies has emerged as a critical priority for sustainable coal extraction. Among these, Gob-Side Entry Retaining (GER) technology represents a promising solution, capable of improving resource recovery rates to over 90% while maintaining operational safety [5]. Specifically, the roof-cutting and pressure relief gob-side entry retaining (RCPR-GER) technology has gained significant attention for its potential to address resource utilization and safety challenges in deep coal seams [6,7,8].

The application of GER technology in China spans over six decades, with its early development progressing slowly. A phase of rapid growth commenced in the 1980s, driven by the nation’s push for mechanized mining and bolt support technology. However, the technologies of this period relied mainly on passive support and simple filling methods. The roadside support structures often suffered from insufficient strength, slow early-load-bearing capacity, and inadequate yieldability, making it difficult to effectively control roof rotation and subsidence. Consequently, their application was primarily limited to shallow depths, thin coal seams, and low-stress conditions. Currently, Chinese scholars have conducted extensive and in-depth research on the technical and theoretical aspects of GER. Various technologies, including GER without roadside filling, GER with roadside filling, and RCPR-GER, have been widely implemented in coal mines with shallow, deep, thin, and medium–thick seams. However, relevant studies indicate that coal resource mining in China is progressively moving into deeper regions, with an average mining depth increase of 8–12 m/a [3]. The prevalence of hard roofs in deep mining poses challenges for the application of traditional roadside filling GER. Consequently, to overcome these limitations, pillar-free mining technology achieved key breakthroughs by focusing on active control and high-performance support. Against this backdrop, Academician He Manchao proposed the RCPR-GER method, utilizing bidirectional cumulative tension blasting, providing robust technical support for GER under deep, hard roof conditions. This technique aims to shorten the roof cantilever beam length, block stress transfer, and maintain entry integrity through temporary support and reinforcement. Nevertheless, the application of RCPR-GER technology in deep mining and certain complex conditions still faces significant limitations and shortcomings.

This paper provides a comprehensive review of the development status of RCPR-GER technology in China. It covers the evolutionary history, main technical types, characteristics of surrounding rock structure, key roof-cutting processes, and offers an in-depth analysis of typical engineering case studies from the coal mining sector. Finally, it identifies existing problems within the current RCPR-GER technology and suggests potential directions for future improvement.

2. Basic Studies on Roof-Cutting and Pressure Relief Gob-Side Entry Retention

2.1. Basic Literature on Pressure Relief Gob-Side Entry Retaining and Roof-Cutting

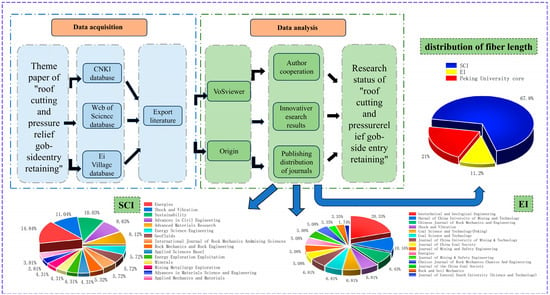

This section analyzes the research status of roof-cutting and pressure relief gob-side entry retaining from 2011 to 2023, using data from CNKI, EI, and Web of Science databases, visualized with VOSviewer (1.6.18) and analyzed with Origin software (2022a). Figure 1 depicts the research concepts.

Figure 1.

Research idea.

To systematically and transparently present the research status in the field of roof-cutting and pressure relief gob-side entry retaining, this study follows a structured literature retrieval and screening process. A detailed explanation of the keyword strategy and literature screening procedure is provided below.

- (1)

- Keyword Search Strategy

A systematic search strategy was employed for this study. For Chinese literature, the CNKI database was used with the subject search formula: ‘SU = (gob-side entry retaining OR non-pillar mining) AND (roof-cutting OR pressure relief OR roof presplitting)’. For English literature, the EI (Engineering Village) and Web of Science databases were searched using the topic-based formula: ‘TS = ((gob-side entry retaining OR non-pillar mining) AND (roof cut* OR pressure relief OR roof presplitting))’. The search period covered 1 January 2011 to 30 November 2023.

- (2)

- Literature Screening Process

The literature screening adhered to systematic and reproducible principles and consisted of four main steps:

Initial Retrieval and Deduplication: A total of 1038 documents were retrieved from the three databases (CNKI: 583; EI Village: 48; Web of Science: 407). Duplicate records were removed using reference management software and manual verification.

Title and Abstract Screening: Based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, the titles and abstracts of the deduplicated documents were reviewed to exclude those that were clearly irrelevant or did not meet the document type requirements.

Full-Text Review: The full texts of the initially screened documents were obtained and thoroughly evaluated for content relevance and research depth. Documents that were unfocused, had incomplete data, or lacked clear methodological descriptions were excluded.

Final Confirmation: Through the above three-tier screening process, the final set of literature for quantitative and visual analysis in this review was determined. The entire process ensured that all included documents are directly and closely related to the core theme of roof-cutting and pressure relief gob-side entry retaining.

The initial search yielded 1038 publications. After deduplication and screening, 583 relevant Chinese papers (including 126 from Chinese core journals and 19 indexed in EI), 48 papers from EI, and 407 SCI papers from Web of Science were included for analysis. The distribution of domestic and foreign journals in the field of roof-cutting and pressure relief gob-side entry retaining is illustrated in Figure 1. Reference source not found. The number of SCI journals accounts for approximately 67.8%, the number of Chinese EI journals accounts for approximately 11.2%, and the number of Peking University core journals accounts for approximately 21%.

Following the inaugural theoretical and applied research on RCPR-GER in deep mines, significant scholarly efforts have been dedicated to advancing this field [9]. Subsequent foundational work established critical stability principles and support technologies for GER in fully mechanized caving faces, which in turn spurred the successful development of paste filling techniques [10]. A major leap forward was the introduction of novel GER methods utilizing high-water material for roadside filling, representing a significant optimization of pillar-free mining technology and coal mining system layout [11]. Further innovations have focused on the mechanisms and control technologies for surrounding rock in specific contexts, such as gob-side entry driving with large mining height and small coal pillars [12]. Concurrently, substantial progress has been made in support materials and equipment, including the development of flexible formwork concrete theory, specialized materials, and integrated preparation, transportation, and support units for gob-side entry retaining [13]. Meanwhile, relevant international studies have also revealed the universal applicability of similar mechanical principles. For example, research on the interaction between stress redistribution and cantilever roof behavior in longwall mining [14] and analysis of stress evolution beneath coal pillars and its impact on the stability of adjacent roadways in close-distance coal seams [15] both indicate that the core mechanical challenges of roof control and stress management are common issues faced in global deep coal mining. This further confirms the broad relevance of the technical principles discussed in this paper.

In recent years, research has intensified, forming a collaborative academic network centered on key research groups from several leading Chinese universities and institutes. It is anticipated that future advancements in RCPR-GER will continue to rely on and benefit from such robust scholarly and team cooperation, fostering further exchange and innovation in the field.

2.2. Technical Types of Gob-Side Entry Retaining

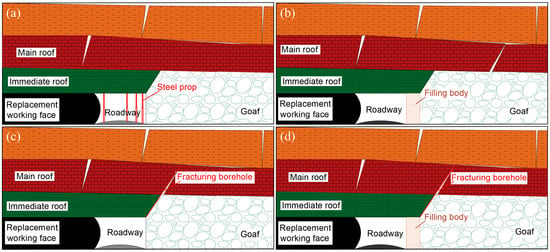

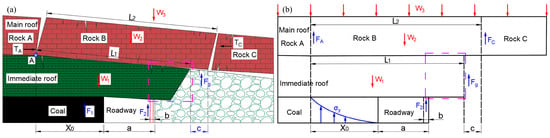

Gob-side entry retaining technology was initially developed in Germany in the 1950s and later applied in countries like the UK, Australia, and the former Soviet Union, yielding significant economic benefits. China introduced this advanced technology in the 1970s [16]. With advancements in coal mining technology and support materials, GER has evolved into four main types (Figure 2):

Figure 2.

Summary of technical types of gob-side entry retaining. (a) Gob-side entry retaining without roadside filling, (b) Roadside filling gob-side entry retaining, (c) Roof-cutting pressure relief gob-side entry retaining, (d) Roadside filling roof-cutting pressure relief gob-side entry retaining.

- (1)

- Gob-side Entry Retaining Without Roadside Filling

The technology of gob-side entry retaining without roadside filling (Figure 2a) is applicable to shallow burial depths, thin coal seams with minimal mine pressure, and mines that do not consider closed goaf and no gas hidden dangers [17]. In the initial phase, the gob-side entry retaining wall without roadside filling was predominantly constructed with wooden pillars, I-beams, U-shaped steel, and other materials as roadside support. The passive roof-cutting effect (referred to as the passive roof-cutting effect, which is achieved through high-resistance roadside support structures rather than active fracturing techniques) and gangue-retaining effect of metal pillars were employed to create a metal pillar roof-cutting gob-side entry retaining structure [18]. The key to successful gob-side entry retaining without roadside filling lies in the support structure’s ability to rapidly develop high resistance against the acting forces. This is essential to ensure that the direct roof outside the roadway is cut off in time, preventing its collapse from causing damage to the roadway. Consequently, as the dimensions of the roadway, the thickness of the coal seam, and the depth of mining increase, the roadway side support gradually adopts a combination of a hinged roof beam and a single pillar, which offers enhanced support performance. Additionally, metal mesh and I-steel are employed for gangue-retaining support, addressing the issue of the limited strength of a closed goaf. Yin [17] employed the use of a π-beam and a single hydraulic prop in order to create a robust passive roof-cutting support structure, thereby guiding the main roof to collapse in accordance with the predetermined position. Yang [19] employed the support force generated by the single hydraulic prop to facilitate passive cutting of the top while utilizing the I-beam with the metal mesh to safeguard the lateral aspect. At present, this technology is only applied to shallowly buried thin coal seams, and there is no documented instance of its successful application in thick coal seams or ultra-thick coal seams. It is essential to collaborate with roof-cutting and pressure relief technology to develop roof-cutting and pressure relief gob-side entry retaining technology.

- (2)

- Roadside Filling Gob-side Entry Retaining

The technology of gob-side entry retaining with roadside filling is widely used in shallow thin coal seams and medium–thick coal seams. The roadside filling body in this technology plays the role of a coal pillar in gob-side entry driving [20,21], but it does not eliminate the long cantilever structure on the side of the goaf, resulting in the stress concentration in the goaf on the roof of gob-side entry retaining, and the deformation of gob-side entry retaining is serious, as shown in Figure 2b. The filling body must suppress the roof separation in the early stage to maintain its integrity. The traditional roadway filling body, such as a wooden crib, gangue, concrete wall, etc., affects the construction process, and the deformation control of the roadway surrounding rock is difficult. The bearing capacity of the traditional backfill is small, and it is difficult to meet the bearing capacity requirements in the case of a large mining height or a hard roof. Therefore, the backfilling body has been gradually developed into a high-water quick-setting material, paste material, and flexible formwork concrete material with special mechanical properties such as high strength, strong adaptability, rapid construction, and low cost [13], and continuous backfilling can be realized.

Guo [22] used high-water materials for roadside filling in Xinyuan Mine and found that the optimum width of the filling body was 1.5 m and the strength was 8.1 MPa. Guo [23] proposed a layered paste filling mining technology for retaining thick coal seams. The compressive strength of the top-layer filling body is 3 MPa, and the compressive strength of the bottom-layer filling body is 7.5 MPa. Hao [24] determined that the width of the flexible formwork concrete filling body in Xinjing mine was 1.2 m by numerical simulation and achieved a good effect of retaining the roadway.

The characteristics of various filling materials are shown in Table 1. Compared with gob-side entry retaining without roadside filling, roadside filling gob-side entry retaining technology has a wide range of applications for filling materials. The author believes that without considering the closed goaf, for shallowly buried deep, or thin coal seam mines, both technologies can meet the requirements of roadway retaining, but the former has a lower material cost. For medium–thick coal seams or hard roof mines, the former can use the unit support with greater support resistance for roadway support, but the initial investment cost is higher. The latter can use the flexible formwork concrete material with better performance as the backfill, and the cost is also higher.

Table 1.

Characteristics of filling material.

- (3)

- Roof-cutting and Pressure Relief Gob-side Entry Retaining

The dominance of roof-cutting and pressure relief methods in deep mining stems from a shift from passive support to active modification of the roof structure and stress path. Traditional roadside filling replaces the coal pillar with an artificial support but struggles under high stress in deep conditions, as it cannot address the long cantilever of the main roof over the goaf, which transfers significant bending moments and stress to the roadway support.

In contrast, roof-cutting severs the connection between the roadway roof and the goaf-side main roof, transforming the long cantilever into a shorter, more easily caving structure (short beam). This reduces the bending moment and load on the support, lowers resistance and deformation requirements, and promotes the timely caving of roof strata. The compacted goaf waste then provides early support, further alleviating stress on the entry. This active cutting-transforming-releasing mechanism offers a more robust and often more economical solution for maintaining stability under high in-situ stresses, making it the preferred approach in deep and hard roof mining conditions in China.

With the improvement of coal mining and support technology, combined with the research results of the international coal industry, Academician He Manchao proposed the technology of roof-cutting and pressure relief gob-side entry retaining [25,26,27]. Based on the theory of roof-cutting short beam [28], the working face is actively cut on the side of the goaf, and the roadway roof is reinforced by U-shaped steel, constant resistance large deformation anchor cable, single hydraulic prop, unit support, and other support materials, so as to cut the roadway and the basic roof of the goaf, so as to change the stress transfer path of the roof above the roadway and realize automatic roadway formation, as shown in Figure 2c. The technology has significant economic advantages. The above-mentioned support materials replace the filling body, which not only reduces the production cost but also optimizes the coal mining process.

In addition, the burial depth of the coal seam applied by this technology is mostly less than 650 m, which is mainly applied to thin coal seams and medium–thick coal seams, and is less applied to thick coal seams. Therefore, although the technology has potential, it still needs further breakthroughs in theoretical research to promote its large-scale application in deep mines. At present, hydraulic fracturing and blasting presplitting technology are commonly used for roof-cutting in Chinese mines. Hydraulic fracturing technology is suitable for rock layers with certain permeability, which can absorb and transmit water pressure. Due to the existence of roof joint cracks, the development direction of hydraulic fracturing cutting is difficult to control, and it is easy to destroy the integrity of the roof. The subsequent development of directional hydraulic fracturing and high-pressure water-jet cutting well controls the development direction of presplitting cutting. Blasting presplitting technology is usually applied to medium-hard rock and hard rock layers with good integrity and bearing capacity. The problem of blast control is the main reason for its limited application in high-gas mines. Li [29] established a mechanical model of hard roof-staged hydraulic fracturing, roof-cutting, and retaining roadway, and studied the roof-cutting effect under different segmentation point spacing conditions through numerical simulation. Jia [30] divided the hard rock layers in the weakly bonded composite roof into four levels according to their thickness and formed a differential blasting presplitting grading pressure relief system.

- (4)

- Roadside Filling, Roof-cutting, Pressure Relief, Gob-side Entry Retaining

With the gradual development of coal mining into deep mining, the geological conditions are complex, and the requirements for roof-cutting and pressure relief gob-side entry retaining technology are more stringent. It is difficult to control the deformation of the surrounding rock only by active roof-cutting. Therefore, based on the key layer theory of Academician Qian [31], the technology of gob-side entry retaining with roof-cutting and pressure relief by roadside filling is proposed. By cutting the roof, the stress transfer path of the roof is changed, and the damage to the roof beam structure and the surrounding rock of the roadway is reduced. At the same time, the roadside embankment body develops rapidly, and high-water embankment and flexible concrete embankment appear. The surrounding rock control effect is better, as shown in Figure 2d.

In addition, the mechanized automatic filling system has been further developed and improved, and the filling rate has been significantly increased, which provides favorable conditions for the development and application of this technology. At present, the technology of gob-side entry retaining with roadside filling, roof-cutting, and pressure relief has been successfully extended to complex geological conditions and is widely used in large dip angles, thick coal seams, and deep coal seams [32]. Ma [33] applied flexible formwork filling and energy-collecting blasting technology in a 6 m thick coal seam to ensure the stability of the retained roadway. Liu [34] established a mechanical model of roof-cutting under high water filling conditions and designed the specific process of roof-cutting, roadway support, and high-water filling blasting. Table 2 below presents a comparison of the main technical types of gob-side entry retaining.

Table 2.

Comparison of the main technical types of gob-side entry retaining.

The dominance of roof-cutting and pressure relief methods, particularly in deep mining, stems from a fundamental shift in control strategy: from passively supporting the roof load to actively modifying the roof structure and stress path. Traditional roadside filling methods essentially replace the coal pillar with an artificial support body. While effective in shallow depths, this approach struggles in deep conditions where high stresses lead to excessive compression and failure of the filling body, and crucially, it does not address the long cantilever of the main roof over the goaf. This long cantilever transfers significant bending moments and stress concentrations to the roadway support system.

In contrast, roof-cutting technology proactively severs the physical and mechanical connection between the roadway roof and the goaf-side main roof. This transforms the long, fixed-end cantilever beam into a shorter, more easily caving structure (the short-beam concept). The primary engineering benefits are twofold: (1) It drastically reduces the bending moment and suspended load imposed on the roadside support, lowering its required resistance and deformation capacity. (2) It facilitates timely caving of the roof strata behind the support, allowing the goaf waste to compact and provide early support, further mitigating stress on the retained entry. This active cutting-transforming-releasing mechanism offers a more robust and often more economical solution for maintaining entry stability under high in-situ stresses, which is why it has become the preferred approach in deep and hard roof mining conditions in China.

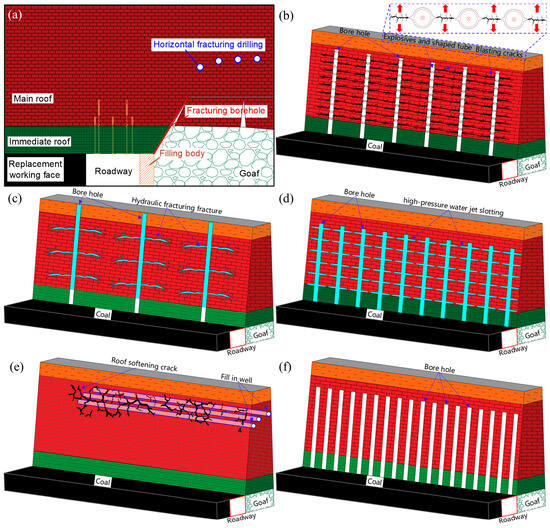

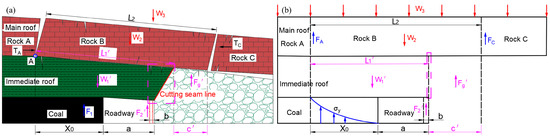

2.3. Top-Cutting Pressure Relief Technology

Roof-cutting and pressure relief technology play an important role in dealing with the problem of hard roof falling. Its core is to subtly change the shape of the surrounding rock of the roof, destroy the integrity of the roof, and then make the roof fall in time, effectively reducing the pressure strength of the roof, preventing the occurrence of rock bursts to a large extent, and achieving effective pressure relief. The commonly used roof-cutting and pressure relief technologies (Figure 3) include blasting, presplitting roof-cutting, hydraulic fracturing roof-cutting, high-pressure water-jet slotting pressure relief, roof water injection softening, and dense drilling roof-cutting [35,36].

Figure 3.

Commonly used roof-cutting pressure relief technology. (a) The schematic diagram of roof-cutting pressure relief technology, (b) The presplitting roof-cutting technology of blasting, (c) Hydraulic fracturing roof-cutting, (d) The high-pressure water-jet slotting pressure relief technology, (e) The roof water injection softening technology, (f) The roof-cutting technology of dense drilling.

- (1)

- Blasting Presplitting Roof-cutting

The presplitting roof-cutting technology of blasting (Figure 3b) is widely used in the pressure relief of the roadway surrounding rock. Directional blasting technology [37] can destroy the surrounding rock along the set fracture direction. This technology is based on the principle of two-way shaped blasting, which can produce tensile stress concentration [38,39] to artificially control the fracture direction of the roof rock structure (along the dip direction or strike direction of the working face) [40]. With its efficient and fast characteristics, the technology has obvious advantages in the application of impact hazard areas [36]. He [41] used innovative energy-harvesting blasting technology to successfully cut off the stress transfer of the roof of the retained roadway and realized the directional presplitting of the roof. At the same time, the roof reinforcement was carried out in combination with the anchor net support technology. This comprehensive scheme has a simple process and a significant effect on the retained roadway and has been widely promoted and applied. Yuan [42] established the mechanical model of the surrounding rock of roof-cutting and retaining roadway in a large mining height working face with a thin direct roof and found that the distribution characteristics of an approximate exponential function curve between tensile stress and roof-cutting height.

- (2)

- Hydraulic Fracturing Roof-cutting

Hydraulic fracturing roof-cutting is a new technology developed in recent years to weaken the strength of the roof [2]. It injects water under high pressure into the rock layer, thereby widening the internal cracks of the rock mass, increasing the degree of joint fracture development in the rock layer, and achieving the purpose of weakening the roof strength [43,44,45]. There are two main ways to arrange hydraulic fracturing wells, as shown in Figure 3c. One is to arrange fracturing wells in the advanced coal face near the side of the roadway support to weaken or cut off the roof. The second is to arrange fracturing boreholes horizontally in the whole roof above the roadway support to form cracks and make the roof collapse easier. Kang [46] carried out hydraulic fracturing on the hard roof and, at the same time, monitored the stress variation characteristics near the borehole. It was found that the stress of the coal seam was significantly reduced, and the pressure relief was obvious. Lin [47] thoroughly discussed the three-dimensional stress distribution law of the roof during the advancement of the working face and found that the pressure relief effect of hydraulic fracturing is most significant when the direction of the principal stress coincides with the direction of the roadway. Wu [48] carried out the directional hydraulic fracturing test for hard and thick roofs and determined the specific range of directional hydraulic fracturing roof-cutting and the boundary of plastic change in the surrounding rock after pressure relief.

- (3)

- High-pressure Water-jet Slotting Pressure Relief

The high-pressure water-jet slotting pressure relief technology is to impact the coal rock mass with high-pressure water, thereby creating a pressure relief weakening area, which can effectively relieve the high stress inside the coal body and is widely used in the field of roof-cutting pressure relief and coal seam permeability improvement [49,50]. The rock-breaking process of high-pressure water-jet is complex, and the breaking time is very short. The rock-breaking process involves the three-phase coupling problem of fluid, solid, and gas. Many scholars have proposed the rock-breaking theory of high-pressure water jets, including rock-breaking theory [51], dense core-splitting rock-breaking theory [52], cavitation-breaking theory [53], stress wave-breaking theory [54], but most of them are still at the hypothesis stage. Therefore, the rock fracture mechanism is not clear, and the theoretical research lags behind the practical application research, so the basic theory needs to be further improved. The single-factor experiments of different jet pressures studied by our research group are shown in Figure 3d.

- (4)

- Roof Water Injection Softening

The roof water injection softening technology (Figure 3e) is mainly used in weakly cemented rock coal mines. After the roof is exposed to water, the shear strength and cohesion of the roof are reduced, thus forming a softening weak surface to achieve the purpose of indirect pressure relief [55]. This technology can effectively prevent the occurrence of rock failure events. The process is simple, and the cost is low. However, the technology needs to strictly control the softening and water injection parameters (hole spacing, water injection pressure, water injection time) to achieve the best softening and pressure relief effect. Yang [56] used high-pressure water injection in Wudong coal mine to change the internal structure of the surrounding rock, reduce the strength of the surrounding rock, and thus reduce the incidence of rock burst. Guo [57] studied the water softening characteristics and stress-seepage interaction of weakly cemented sandy mudstone, which provided a theoretical basis for the hydraulic coupling of weakly cemented sandy mudstone and played a certain guiding role in field engineering applications. Liu [58] investigated the mechanical properties and pore structure of rock fracture samples with different soaking times and found that the change in soaking time on the mechanical properties varied with the size of the sample.

- (5)

- Roof-cutting by Dense Drilling

The roof-cutting technology of dense drilling (Figure 3f) is to transform the surrounding rock structure of the lateral roof of the goaf. The overburden load and roof weight are used to cut off the basic roof of the hanging roof in the goaf, which can effectively reduce the roof pressure of the roadway. The operation and construction equipment of this technology are simple, and there is no need for blasting, but the roof-cutting effect of the broken seam zone formed by it is poor, which is not conducive to roof collapse [59]. Zhou [60] carried out the experiment of intensive drilling and roof-cutting in the field and found that intensive drilling and roof-cutting can realize the gob-side entry retention, and the deformation of the roadway can meet the normal use. Compared with the presplitting blasting roof-cutting technology, this method has larger deformation and longer duration. Li [61] studied the borehole roof-cutting under the condition of a bottom-layer regenerated roof and found that the tensile stress concentration of the roof increased due to the weakening zone caused by dense boreholes, which led to tensile fracture. At present, the research and application of dense borehole roof-cutting are still relatively few [62], and there is no detailed theoretical research and key parameter determination method for dense borehole weakening roof fracture.

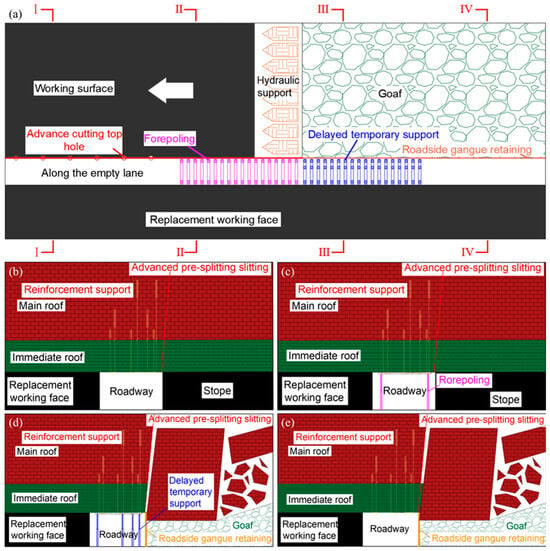

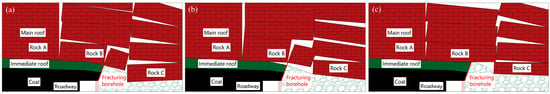

2.4. Process Flow of Roof-Cutting and Pressure Relief Gob-Side Entry Retaining

The process flow of roof-cutting and roadway support is shown in Figure 4a, including presplitting roof-cutting, reinforcement support, temporary support, gangue support, and air leakage prevention. First, presplitting, roof-cutting, and roadway reinforcement are carried out on the goaf side in the mining influence area in front of the working face to block the stress transfer of the roadway roof and control its deformation, as shown in Figure 4b. Advance support is then provided within the advance mining influence area to ensure that the surrounding rock of the roadway is in a stable state prior to mining, as shown in Figure 4c. Then, after the working face is mined, the dynamic pressure of the roof of the roadway is high, and the single hydraulic support, unit support, portal support, and other materials can be used for delayed temporary support in the roadway. In addition, to prevent the roof from collapsing into the roadway and to prevent air leakage in the goaf, the measures of gangue blocking and air leakage prevention are taken on the side of the goaf, as shown in Figure 4d. Finally, outside the area of mining influence behind the working face, the mining influence on the roof is relatively small, and its condition has gradually stabilized. The delayed temporary support can be removed, leaving only the gangue-retaining support, as shown in Figure 4e.

Figure 4.

Process flow chart of retaining lane along the goaf by cutting the top and discharging pressure. (a) Plane diagram of roof-cutting retaining roadway, (b) Section I-I, (c) Section II-II, (d) Section III-III, (e) Section IV-IV.

3. Characteristics of the Surrounding Rock Structure and Control Techniques for Gob-Side Entry Retaining with Roof-Cutting and Pressure Relief

3.1. Characteristics of the Surrounding Rock Structure for Gob-Side Entry Retaining with Roof-Cutting and Pressure Relief

The main difference between gob-side entry retaining and ordinary roadway is the deformation and degree of damage of the surrounding rock in the stage of severe deformation after mining. The deformation of the surrounding rock in gob-side entry retaining is closely related to the rotation and subsidence of the roof in the goaf, the structural stability of the surrounding rock in the roadway, and the filling rate of the goaf caused by the roof collapse [63,64]. In order to describe the deformation and failure characteristics of the surrounding rock of goaf-side entry retaining and to determine the best support parameters of the roadway and roadside, many scholars have established the structural model of the surrounding rock of goaf-side entry retaining [65], such as Figure 5 and Figure 6, which are the structural models of the surrounding rock of goaf-side entry retaining before and after roof-cutting. The models are primarily based on the following assumptions: (a) the roof strata are continuous and homogeneous linearly elastic materials; (b) the key rock block (Rlock B in Figure 5 and Figure 6) formed after the fracture of the main roof is treated as a rigid body, and its rotation and subsidence are the main causes of roadway surrounding rock deformation; (c) shear slippage and plastic deformation between strata are neglected, and load transfer satisfies static equilibrium conditions; (d) the support effect of the goaf gangue on the roof is simplified as a uniformly distributed force. It can be seen from the figure that the structural characteristics of the surrounding rock of the roof-cutting roadway are related to many factors, such as the bearing strength of the overburden rock, the cantilever length of the direct roof, the supporting resistance of the roadway side, and the supporting force of the cave gangue to the roof.

Figure 5.

Roof space structure and mechanical structure model of uncut entry retaining. (a) Roof space structure, (b) Mechanical structure model.

Figure 6.

Roof space structure and mechanical structure model of the roof-cutting entry retaining. (a) Roof space structure, (b) Mechanical structure model.

The resistance of the roadside support when the roadway is not cut is:

The resistance to the road when cutting the roof is calculated as follows:

x0: width of the limit equilibrium zone in the coal body; c, c′: width of the supporting gangue under rock block B before and after roof-cutting; a: roadway width; σy-plastic zone of coal roof support force; W1, W1′: direct roof load before and after roof-cutting; W2: basic top load; W3: rock block B overlying strata load; L1, L1′: the cantilever length of immediate roof before and after roof-cutting; L2: basic top cantilever length; FA: friction force between rock block B and rock block A; FC: friction force between rock block B and rock block C; TA: horizontal thrust of rock block A to rock block B; TC: horizontal thrust of rock block C to rock block B; F1: supporting force of coal in plastic zone to roof; F2, F2′: roof-cutting before and after the roadside support on the roof support force; Fg, Fg′:Supporting force of gangue on roof before and after roof-cutting.

It can be seen from Equations (1) and (2) that the width of the gangue in the goaf and its roof support force, the length of the direct roof cantilever, and its load directly affect the magnitude and distribution of the roadside support resistance. In the process of roof-cutting and retaining roadway, the roadside support is very important for roof support, and its performance is directly related to the deformation and stability of the roadway. After roof-cutting, the roadside support needs to adapt to the new stress distribution and rock movement caused by the change from the F-type rock support structure to the I-type structure. Academician He [66] established a mechanical model of the surrounding rock structure-roadside support body for roof fracture in the whole process of roadway support and calculated the resistance of roadside support by this model. Professor Bian [67], based on the roof structure fracture and caving characteristics of gob-side entry, constructed the mechanical model and calculation formula of roadside support resistance in different mining stages, which provided a theoretical basis for partition precision support in different stages. Li [68] thoroughly studied the relationship between the roadway support resistance and its compression and established the corresponding mathematical model. He believed that in the later stage of the roadway, the core of the backfill should maintain the stability of the big structure rather than changing its shape.

In addition, it can be seen from Figure 5 and Figure 6 that there is a great correlation between the resistance of the roadside support and the load of the immediate roof and the main roof (i.e., the thickness of the immediate roof and the main roof). Professor Shen [69] divided the thickness of roof layers into three levels, including thin layers, medium–thick layers, and thick layers. Considering that the height of roof-cutting can make the roof fall and fill the goaf, the roof structure model under different thicknesses of the immediate roof and main roof is obtained by theoretical and numerical simulation research. As shown in Figure 7, based on different immediate roof thicknesses, it is found that the smaller the thickness of the immediate roof, the smaller the height of the goaf, and the larger the space for rotational and translational settlement of the main roof over the goaf. As shown in Figure 8, based on different main roof thicknesses, the greater the thickness of the main roof, the greater its ability to resist deformation and fracture; the closer the fracture location is to the deep part of the coal face, the smaller the deformation of the support roadway. Professor Zuo [70], based on the theory of medium-thickness plate, studied in depth the relationship between the thickness of rock layers and their fracture structure and found that when the rock layers are thin, they undergo tensile fracture to form a masonry beam structure; when the thickness of the rock layer is moderate, the layer fracture is caused by tensile shear effect; when the thickness of the rock layer is large, the step rock beam is formed by shear fracture. The structural characteristics of the surrounding rock determine the stability and bearing capacity of the roadway. Therefore, the understanding and rational use of the structural characteristics of the surrounding rock is the key to the roof-cutting and retaining roadway technology.

Figure 7.

Classification model based on immediate roof thickness. (a) Thin-layer direct roof; (b) Medium–thick-layer immediate roof; (c) Thick immediate roof.

Figure 8.

Classification model based on the main roof thickness. (a) Thin-layer basic roof, (b) Medium–thick-layer basic roof, (c) Thick-layer basic roof.

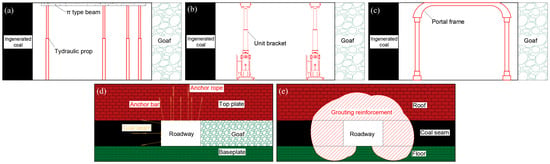

3.2. Technology Used to Control the Surrounding Rock

Bolt support technology has been widely used in most coal-producing countries in the world. Australia has studied by means of in-situ stress tests and numerical simulations, and the bolt support rate of coal roadways is 100%. Since the introduction of Australia’s advanced technology in 1987, the bolt support rate in the UK has rapidly increased to 80% [71]. In addition, in most parts of Europe, metal support is gradually being replaced by bolt support. China has been using bolted support technology since 1956, and the bolted support rate of coal faces is 75% [72].

At present, bolt and anchor cable support is widely used in roadway support, but with the increase in mining depth, it is difficult for ordinary high-strength bolts and anchor cables to effectively control the deformation of the roadway surrounding rock under deep and complex conditions. Kang [63] pointed out that in the process of deep mining, the ground stress supported by the roadway support is greatly increased, the rotational deformation of the roof is more severe, and the deformation of the roadway support is serious. To this end, China Coal Technology and Engineering Group has developed a high-tensile, strong bolt (cable) support system [73], which provides a strong guarantee for deep gob-side entry support. Aiming at the problems of large deformation, high ground pressure, and difficult support in deep soft rock roadways, He [74] put forward the theory of soft rock engineering mechanics and developed a constant resistance and large deformation bolt (cable).

Based on the existing basic support system in the roadway, when the roadway is disturbed by mining activities or geological structures, further reinforcement measures are taken, i.e., the support in the roadway is strengthened. This method of strengthening the support is varied and can be divided into active support (single hydraulic support, unit support), passive support (portal support), grouting reinforcement, and anchor cable support according to the different support principles behind them. The support elements can be categorized by their primary function and deployment phase: permanent support (e.g., anchor rods/cables, grouting reinforcement) ensures long-term integrity, while temporary reinforcement support (e.g., hydraulic props, unit brackets) provides active, high-resistance control during critical periods of mining-induced stress adjustment. The type of reinforced support in the roadway is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Schematic diagram of the main support element types employed in gob-side entry retaining (including both permanent and temporary reinforcement support). (a) Hydraulic prop, (b) Unit Bracket, (c) Portal frame, (d) Anchor rod and anchor rope support, (e) Grouting reinforcement.

After in-depth exploration and research, the application of grouting reinforcement technology theory and its materials has made remarkable progress [75], but the application of this technology in gob-side entry support is rare [76]. Due to the problems of long service life, obvious separation failure of coal and rock mass, and the development of deep cracks in the gob-side entry, it is difficult to control the roof separation by bolted mesh cable support. Therefore, the fractured rock layers are joined together by grouting to form a complete roof, which can also ensure the anchoring effect of bolts and cables [77].

Single hydraulic props and unit supports are commonly used in pillar roadway reinforcement support in the mining stage of gob-side entry retaining working face. A single hydraulic prop is generally used with a π-beam, which has a certain setting force and working resistance and can effectively reduce the deformation of the surrounding rock and maintain the stability of the roadway. The unit support [78] was first applied in the Shendong mining area, which greatly improved the supporting effect in the roadway. The unit support has greater initial support force, working resistance, and better stability than the single hydraulic support. China Coal Science and Industry Mining Research Institute Co., Ltd. developed a self-moving two-column unit support with an initial support force and working resistance of 5000 kN and 6500 kN, respectively [79].

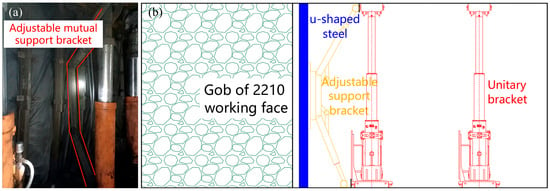

The research group implemented roof-cutting and pressure relief gob-side entry retaining in the 8201 auxiliary transport crosshead of Dongjiang Coal Industry. The lagging temporary support was supported by a single hydraulic prop + π beam support and unit support, respectively. The effect of field implementation is shown in Figure 10. In addition, in the 2210 working face of Jining Coal Industry, a set of adjustable support with radian is set up in the middle of the U-shaped steel side and the unit support, and the supporting force of the unit support is used to effectively prevent the bending deformation of the U-shaped steel in the goaf and the heave in the roadway and to reduce the lateral pressure of the gangue in the goaf, as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 10.

Dongjiang coal industry field implementation effect. (a) Unit Bracket, (b) Single hydraulic prop + π beam, (c) The intersection of single hydraulic prop and unit support.

Figure 11.

Application diagram of adjustable support. (a) On-site implementation diagram; (b) Theory implementation diagram.

4. Discussions

The roof-cutting and pressure relief gob-side entry retention technology has been successfully applied in mines with different coal seam thicknesses (thin coal seam, medium coal seam, thick coal seam), different excavation depths (shallow and deep), different roof structures (hard roof, composite roof), different gas conditions (low gas, high gas), and other complex conditions, which can guide mines with similar conditions. The typical application cases are shown in Table 3, including 5 cases independently completed by our research group (serial numbers 4–8). In addition, the research group did not adopt the technology of roadway filling and roof-cutting. Notably, in the 2104 working face of Huahong Coal Industry, the research group implemented a successful gob-side entry retaining by optimally deploying dense single hydraulic props (a passive roof-cutting approach) without employing additional roadside filling or active roof-cutting techniques. This case specifically demonstrates the effectiveness and feasibility of the passive roof-cutting strategy under the given gentle geological conditions (serial number 16).

Table 3.

Typical cases of gob-side entry retaining using roof-cutting and pressure relief.

5. Engineering Suggestions and Conclusions

5.1. Engineering Suggestions

Based on the systematic review of the principles, surrounding rock control mechanisms, and typical engineering cases of roof-cutting and pressure relief technology for gob-side entry retaining presented earlier, this section provides a comparative analysis of the main technologies. The aim is to clarify their effectiveness, limitations, and applicability under different geological and stress conditions, thereby offering guidance for technology selection in engineering practice.

1. Blasting Presplitting Roof-Cutting demonstrates high efficiency and reliability in creating directional fracture planes in medium-hard to hard, intact roof strata. Its effectiveness in altering the roof stress transfer path is well-proven and contributes significantly to reducing roadway deformation. However, the inherent safety risks associated with explosives fundamentally limit their application in high-gas mines. Furthermore, achieving the desired cutting height and angle becomes technically challenging and economically costly in deep mining environments with high in-situ stress or ultra-thick composite roofs, as the energy required for effective rock fragmentation increases substantially. Additionally, the disturbance generated by blasting can adversely affect existing support.

2. Hydraulic Fracturing Roof-Cutting offers a safer alternative for gas-rich mines and is particularly suitable for roof strata with certain permeability. It effectively creates fracture networks to weaken the roof. Its main limitation lies in the difficulty of precisely controlling fracture propagation direction in naturally jointed roofs, which may compromise roof integrity. While directional hydraulic fracturing technology mitigates this issue, its equipment and operations are more complex. This technology shows significant pressure relief potential in thick, hard roofs under high stress, but its effectiveness decreases in extremely low-permeability or very soft rock layers.

3. High-Pressure Water-Jet Slotting for Pressure Relief provides a precise and controllable method for creating pressure relief slots, beneficial for alleviating local stress concentration and enhancing coal seam permeability. Its application is often constrained by high-power equipment requirements and a relatively shallow effective range in extremely hard rock. The theoretical understanding of its rock-breaking mechanism currently lags behind engineering applications.

4. Roof Water Injection Softening is a low-cost, simple-process technology primarily effective in weakly cemented rock formations. Its success heavily depends on precise control of injection parameters (pressure, time, spacing) to achieve uniform softening while avoiding roof instability or water inrush. The applicability of this technology to hard, low-porosity rock strata is limited.

5. Dense Drilling Roof-Cutting carries minimal operational risk and is suitable for various gas conditions. However, compared to blasting or hydraulic fracturing, it creates a weaker and more discontinuous cutting plane, leading to poorer roof caving characteristics and potentially larger, longer-lasting roadway deformations. This technology is often considered for thin to medium–thick coal seams under relatively low stress or situations where other active cutting techniques are not feasible.

6. Technology Synthesis and Selection Considerations:

(1) For conditions of shallow depth, thin coal seam, low gas, and minimal strata pressure: Gob-side entry retaining without roadside filling or simple dense drilling roof-cutting may be economically viable options.

(2) For conditions of medium–thick coal seam, medium burial depth, and hard roof: Blasting presplitting or directional hydraulic fracturing combined with high-strength roadside support (e.g., constant resistance and large deformation anchor cables, unit supports) are proven effective methods. The choice between them depends on gas conditions (blasting for low gas, hydraulic fracturing for high gas).

(3) For conditions of deep mining, thick coal seam, or hard composite roof: A combined technology of active roof-cutting (blasting/hydraulic fracturing) and high-performance roadside filling body (e.g., flexible formwork concrete) is often necessary to manage high stresses and complex roof structures. Here, the economic cost of filling must be weighed against the benefit of enhanced roadway stability.

(4) For complex conditions such as multi-seam mining, large dip angles, or strong dynamic pressure influence: Technology selection must be based on detailed mechanical analysis of the specific overburden structure. The timing, orientation, and parameters of roof-cutting require a refined design based on key stratum theory and actual stress distribution.

In summary, there is no universally optimal technical solution. Selection must be based on a comprehensive evaluation of geological conditions (burial depth, coal seam thickness, roof lithology and structure, gas content), stress environment, safety regulations, economic feasibility, and on-site equipment and expertise. Future research should focus on developing quantitative models to predict the performance of these technologies under specific interacting parameters, thereby further bridging the gap between theory and customized engineering practice.

5.2. Conclusions

This review systematically examined the development, technical types, and engineering applications of roof-cutting and pressure relief gob-side entry retaining (RCPR-GER) technology in China. The main conclusions are as follows:

1. For deep, hard, and composite roofs, field evidence demonstrates that an inappropriately low roof-cutting height fails to isolate key stratum stress transfer, leading to severe roadway deformation, while an excessive height introduces unnecessary complexity and cost. Therefore, determining the adaptive roof-cutting parameters tailored to specific composite roof structures is the foremost challenge for deep application.

2. The passive roof-cutting effect provided by high-resistance roadside support structures (e.g., single hydraulic props) offers a viable and economical strategy for entry retaining under gentle geological conditions (e.g., shallow depth, thin seams), as proven by field cases. However, its quantitative design criteria and synergistic mechanisms with active cutting require further mechanical modeling and validation.

3. In multi-seam mining scenarios, the presence of remnant upper-seam coal pillars critically influences stress distribution in the lower gate road. Inappropriate roof-cutting parameters under this condition can hinder mining efficiency, necessitating a thorough analysis of the superimposed stress field for parameter optimization.

4. Beyond the height and angle, the orientation of roof-cutting (toward the goaf or coal pillar side) fundamentally alters the fracture position of roof layers, thereby affecting the cantilever length and load on the retained entry. This parameter requires equal attention in design to control entry deformation effectively.

5. The interaction between active roof-cutting (e.g., blasting) and existing reinforcement support can lead to prestress loss in bolts/cables. The quantitative relationship between blast-induced dynamic load, crack propagation, and support effectiveness needs further investigation via coupled models.

6. A universal optimal solution does not exist. A successful application relies on a holistic evaluation integrating geological conditions, stress environment, safety regulations, and economic feasibility. This review synthesizes a conditional selection framework, and future work should focus on developing intelligent decision-support systems that integrate these multi-dimensional parameters.

7. Practical Engineering Implications

The synthesis and analysis presented in this review translate into direct practical guidance for mining engineers and designers. Primarily, it provides a conditional decision-making framework for selecting between no-filling, passive, active, and composite GER techniques, moving beyond trial-and-error or purely empirical approaches. The compiled case database (Table 2) serves as a vital reference for initial parameter estimation (e.g., cutting height, support resistance) under analogous geological conditions. Furthermore, the critical discussion on parameter interactions (e.g., between cutting height, orientation, and support design) highlights the necessity for integrated system design rather than isolated component optimization. This underscores the practical importance of detailed geological assessment and advanced numerical modeling prior to implementation, ultimately aiming to reduce the risk of entry failure, enhance long-term stability, and improve the overall economic viability of pillarless mining in increasingly challenging depths.

The synthesized analysis and case studies presented herein provide an updated reference and a technical selection framework for implementing RCPR-GER under increasingly complex mining conditions.

Author Contributions

D.D.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. X.W.: Writing—review & editing, Data curation, Investigation. J.L.: Data curation, Project management, Roles/Writing—original draft. B.Z.: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. X.F.: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. Y.C.: Data curation, Project management. S.T.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. H.S.: Data curation, Project management. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 52274134, 52474139, 51604184, and 52374080), and the Applied Basic Research Project of Shanxi Province, China (grant numbers 202403011242005).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, F.; Guo, L.F.; Zhao, L.Z. Research on coal safety range and green low-carbon technology path under the dual-carbon background. J. China Coal Soc. 2022, 47, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Xia, Y.C.; Yao, T.W.; Jiang, X.; Xiao, P.Y.; He, Z.X.; Zhou, D.S. Formation mechanisms of hydraulic fracture network based on fracture interaction. Energy 2021, 243, 123057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Research on Key Parameters and Surrounding Rock Control of No Gateside Pack Top Cutting Pressure-Relief of Gob-Side Entry Retaining in Deep Mining; Anhui University of Science and Technology: Huainan, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.S. Process and brainstorming in underground space development. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2022, 18, 733–742. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Zou, B.P.; Tao, Z.G.; He, M.C.; Hu, B. Construction and Application of an Intelligent Roof Stability Evaluation System for the Roof-Cutting Non-Pillar Mining Method. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, H.Y.; Wang, Y.J.; Liu, B.H.; Hou, S.L.; Cheng, Y. Stability Analysis of the Entry in a New Mining Approach Influenced by Roof Fracture Position. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.C.; Wang, X.Y.; Bai, J.B.; Xu, C.T.; Chu, Y.; Hou, B.; Niu, Z.P.; Wang, X. Research on the Stability Mechanism and Control Technology of Surrounding Rock in Filling Working Face with Gob-Side Entry Retaining. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.F.; Li, G.; Gong, W.L.; Wang, J.; Deng, H.L. Energy Evolution Pattern and Roof Control Strategy in Non-Pillar Mining Method of Goaf-Side Entry Retaining by Roof Cutting—A Case Study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.F.; He, M.C.; Yu, X.P.; Huang, Z.G. Research on the Technique of No-Pilar Mining with Gob-Side Entry Formed by Advanced Roof Caving in the Protective Seam in Baijiao Coal Mine. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2011, 28, 511–516. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J.B.; Wang, W.J.; Hou, Z.J.; Huang, H.F. Control mechanism and support technique about gateway driven along goaf in fuly mechanized top coal caving face. J. China Coal Soc. 2000, 25, 478–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.H.; Wu, J.; Qiu, Y.X. Rules of ground pressure and strata control in gateways maintained in goaf. J. China Coal Soc. 1992, 17, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.S.; Wang, P.F.; Cui, S.Q.; Fan, M.Z.; Qiu, Y.M. Mechanism and surrounding rock control of roadway driving along gob in shallow-buried, large mining height and small coal pillars by roof cutting. J. China Coal Soc. 2021, 46, 2254–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L. Research Development and Application of Complete Set of Flexible Formwork Support Control and Efficient Mining Technology in Coal Mine Strata; Xi’an University of Science and Technology: Xi’an, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Le, D.T.; Vu, T.H.; Nguyen, T.T. Analysis of Factors Influencing Roof Weighting and Coal Wall Stability in Longwall Mining under the Combined Effect of Stress Redistribution and Cantilever Roof Behavior. Min. J. 2022, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Le, D.T.; Vu, T.H. Numerical modeling analysis of floor stress distribution under coal pillars and roadway stability in close-distance coal seams. Min. J. 2025, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Y.; Gao, Y.G.; Chen, J.; Cui, X.M.; Chai, H.B. Surrounding rock stabilization and deformation evolution of gob-side entry retaining in deep colliery with mega-height coal seam extracted. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2021, 17, 897–908. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Z.J.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Deng, M.; Yan, S.; Bai, J.B. Gob-Side Entry Retained with Soft Roof, Floor, and Seam in Thin Coal Seams: A Case Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.B. Application of gob-side entry retaining technology without roadside filling in medium-thick coal seam of Xinyuan colliery. Jiangxi Coal Sci. Technol. 2022, 03, 34–36+40. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, G.P. Application research on roadway retention technology of roadless side filing body along gob in nanling coal mine. Coal Mine Mod. 2019, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.Y. Practice of non pillar mining in large and medium thick coal seam in yongcheng mining area. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2019, 15, 256–259. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, Y. Numerical simulation on mechanical characteristics of surrounding rock of gob-side entry retaining. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2015, 11, 1564–1571. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Ma, Q.H.; Wang, W.; Yuan, L. Study on determination of filing body parameters of high water filing gob-side entry retaining in soft surounding rock. J. Shanxi Inst. Energy 2024, 37, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.C.; Song, G.Y.; Ran, D.W.; Song, G.D. Research on mining technology of thick coal seam retaining layering paste filling. Coal 2022, 31, 19–22+64. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, X.F.; Hao, B.Y.; Xie, Y.S.; Zhang, T. Research and application of reasonable width of flexible-formwork concrete filings beside gob-side entry retaining in medium-thickness coal seam. Min. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2019, 46, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.G.; Li, G.H.; Cao, H.T.; Wang, H.J.; Shi, X.Y.; Zhao, Q.Q.; Han, Z.; Zhang, T.; Dai, W.; Zhang, J. Study on the Support System Mechanism of Entry Roof with Roof Cutting Pressure Releasing Gob-Side Entry Retaining Technology. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 2022, 5366168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Wang, Q.; Tian, X.C.; Wang, H.S.; Yang, J.; He, M.C. Stress and deformation evolution characteristics of gob-side entry retained by roof cutting and pressure relief. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. Inc. Trenchless Technol. Res. 2022, 123, 104419104419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.Y.; Wang, J.; Hu, J.Z.; Zhu, D.Y.; Sun, H.; Ma, X.E.; Ming, W.; Li, W. Innovative Control Technique for the Floor Heave in Goaf-Side Entry Retaining Based on Pressure Relief by Roof Cutting. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 7163598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.C.; Song, Z.Q.; Wang, A.; Yang, H.H.; Qi, H.G.; Guo, Z.B. Theory of longwall mining by using roof cuting shortwall team and 110 method—The third mining science and technology reform. Coal Sci. Technol. Mag. 2017, 1, 1–9+13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.J.; Gao, L.; Liu, Y.Q.; Wang, B.; Lei, S. Research on technology and application of hydraulic staged fracturing roof cutting and retaining roadway in hard roof. China Min. Mag. 2023, 32, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, H.S.; Wang, L.; Peng, B.; Wang, G.Y.; Zhang, D.S.; Zhuo, J.; Wang, Y.B. Mechanism and application of classification roof control-pressure relief of gob-side entry retained with weakly caking compound roof. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 2023, 52, 1191–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M.G.; Miu, X.X.; Xu, J.L. Research on key layer theory in rock control. J. China Coal Soc. 1996, 21, 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.X.; Li, S.; Hou, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.L.; Yi, T. Gob side entry protection technology of small coal pillar in steeply inclined three-soft thick coal seam. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2022, 18, 1392–1400. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.T.; Zhang, C.S.; Zhang, S.L.; Zhang, C.; Han, B.C. Research on key parameters of cutting and retaining roadway of thick coal seam in fully mechanized caving and its engineering application. J. Taiyuan Univ. Technol. 2024, 55, 1031–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.F. Research on the application of roof cutting and pressure relief technology in gob side entry retaining with high water content materials. Jinneng Hold. Sci. Technol. 2023, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.G.; Li, X.W.; He, T. Application status and prospect of backfill mining in Chinese coal mines. J. China Coal Soc. 2020, 45, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.K. A comparative analysis of deep hole roof pre-blasting and directional hydraulic fracture for rockburst control. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2021, 38, 706–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.R.; Wu, Y.Y.; Guo, F.F.; Zou, H.; Chen, D.D.; Zhang, X.; Ma, X.; Liu, R.; Wu, C. Application of Pre-Splitting and Roof-Cutting Control Technology in Coal Mining: A Review of Technology. Energies 2022, 15, 6489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.N.; Gao, Y.B.; Wang, J.; Fu, Q.; Qiao, B.W.; Wei, X.J.; Zhang, X. Study on Bidirectional Blasting Technology for Composite Sandstone Roof in Gob-Side Entry-Retaining Mining Method. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.G.; Li, Y.H.; He, F.L.; Fu, G.S.; Gao, S. Study on Stability Control of Retained Gob-Side Entry by Blasting Fracturing Roof Technology in Thick Immediate Roof. Shock. Vib. 2021, 2021, 6613562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Feng, H.L.; Cao, K.; Han, X.B.; Han, X. Optimization of blasting source parameters in blasting construction of close passing through historic site tunnel. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2022, 18, 1292–1304+1316. [Google Scholar]

- He, M.C.; Zhu, G.L.; Guo, Z.B. Longwall mining cutting cantilever beam theory and 110 mining method in China-The third mining science innovation. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2015, 7, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.F.; Zhu, C.; Yuan, Y. Reasonable parameters of roof cutting entry retaining in thin immediate roof and large mining height fully-mechanized face. J. China Coal Soc. 2019, 44, 1981–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xu, S.G. Study on fracture propagation law and influencing factors under glauberite hydraulic fracturing. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2023, 19, 1536–1543+1632. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Kang, H.P. Pressure Relief Mechanism of Directional Hydraulic Fracturing for Gob-Side Entry Retaining and Its Application. Shock. Vib. 2021, 2021, 6690654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Peng, S.J.; Wu, B.; Xu, J.; Yan, F.Z.; Chen, Y.X. Exploration on the characteristics of 3D crack network expansion induced by hydraulic fracturing: A hybrid approach combining experiments and algorithms. Energy 2023, 282, 128968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.P.; Feng, Y.J. Monitoring of stress change in coal seam caused by directional hydraulic fracturing in working face with strong roof and its evolution. J. China Coal Soc. 2012, 37, 1953–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Guo, K.; Sun, Z.Y.; Wang, T. Study on fracturing timing of hydraulic fracturing top-cutting and pressure relief in roadway with strong dynamic pressure. J. China Coal Soc. 2021, 46, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.Z.; Kang, H.P. Pressure relief mechanism and experiment of directional hydraulic fracturing in reused coal pillar roadway. J. China Coal Soc. 2017, 42, 1130–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.L. Numerical study and application of pressure relief and permeability enhancement technology for hydraulic cutting of tunnel uncovering coal. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2020, 16, 291–296. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.R.; Chen, L.; Liu, W.C.; Zhang, H.L.; Wang, J.X.; Liu, Q. Investigation on jet diffusion mechanism with applications to enhancing efficiency in forming directional fractures. Energy 2023, 262, 125568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.F. Coal Damage and Evolution Law under Influence of High Pressure Water Hydraulic Cutting and Their Application; China University of Mining & Technology, Beijing: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.A.; Wang, Y.L. Review of Modern Rock Fragmentation Methods in Coal Mine Construction. Jinneng Hold. Sci. Technol. 2023, 1–8+61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Cao, W.Y.; Xie, Q.G.; Zeng, L.; Zhou, S.W.; Kang, C.Z. Research status and development trend of high pressure jet assisted drilling technology. Nat. Gas Ind. 2023, 43, 116–126. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Z.L.; Zhang, D.; Lu, Y.Y.; Liu, W.C.; Xiao, S.Q.; Cao, S.R. Propagation of stress wave and fragmentation characteristics of gangue-containing coal subjected to water jets. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021, 95, 104137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Yang, Y.; Cao, G.Y.; Liu, Y.; Shao, W.X. Study on the permeability characteristics of sandstone under hydrostatic pressure and model improvement. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2024, 20, 776–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.D.; Li, J.B.; Zhang, W.G.; Li, C.G.; Wang, P. Research on water injection softening of hard rock and its effect evaluation in Wudong Coal Mine. Coal Eng. 2018, 50, 51–53. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.T.; Teng, T.; Zhu, X.Y.; Wang, Y.M.; Li, Z.L.; Tan, Y. Characterization and Modeling Study on Softening and Seepage Behavior of Weakly Cemented Sandy Mudstone after Water Injection. Geofluids 2021, 2021, 7799041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.F.; Xu, G.; Zhang, C.; Kong, B.; Qian, J.F.; Zhu, D.; Wei, M. Time Effect of Water Injection on the Mechanical Properties of Coal and Its Application in Rockburst Prevention in Mining. Energies 2017, 10, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, R.J.; Xin, Q.F.; Li, Y.; Cheng, S.S.; Fu, Z.P.; Qing, Y. Research and Application of Roof Cutting Technology for Gob-side Entry Retaining. Shanxi Coal 2022, 42, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F.W. Research on the Technique of Guiding Gob-Side Entry Formed by Advanced Roof Caving with Weaking Bore in Three-Soft Coal Seam; Xi’an University of Science and Technology: Xi’an, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.Y.; Zheng, L.J.; Zhang, J.X.; Wang, S.; Wang, W.; Huang, Z.J. Dense boreholes for weakening bottom layer by cutting roof and pressure relief of gob-side entry retaining. Saf. Coal Mines 2022, 53, 111–118+125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.G.; Wang, Y.G.; Yang, Y.H.; Gai, Q.K.; Zhang, X.X.; Gao, Y.B. Research and application of non pillar mining technology for cutting roof and retaining roadway in Rongkang Coal Mine. China Min. Mag. 2023, 32, 288–294. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H.P.; Niu, D.L.; Zang, Z.; Lin, J.; Li, Z.H.; Fan, M.J. Deformation characteristics of surrounding rock and supporting technology of gob-side entry retaining in deep coal mine. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2010, 29, 1977–1987. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.H.; Zhou, X.H.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.J. Investigation on control mechanism of balanced and coordinated deformation of tunnel surounding rock and application in engineering. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2023, 19, 79–86+94. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.T.; Shang, J.J.; Zhao, B.; Cao, Q.H. Surrounding rock structural characteristics and anchor-cable strengthened support technology of the gob-side entry retaining with roof cutting and pressure releasing. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2021, 40, 2296–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.C.; Chen, S.Y.; Guo, Z.B.; Yang, J.; Gao, Y.B. Control of surrounding rock structure for gob-side entry retaining by cutting roof to release pressure and its engineering application. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 2017, 46, 959–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, W.H.; Yang, J.; He, M.C.; Zhu, C.; Xu, D.M. Research and application of mechanical models for the whole process of 110 mining method roof structural movement. J. Cent. South Univ. 2022, 29, 3106–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.M. Control design of roof rocks for gob side entry. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2000, 19, 651–654. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.C. Study on Overlying Strata Movement Mechanism of Gob-Side Entry Retaining and Entry Retention Measures in Thick Three-Soft Coal Seam; Henan Polytechnic University: Jiaozuo, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, J.P.; Yu, M.L.; Sun, Y.J.; Wu, G.S. Analysis of fracture mode transformation mechanism and mechanical model of rock strata with different thicknesses. J. China Coal Soc. 2023, 48, 1449–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.B. Surrounding Rock Control of Gob-Side Entry Driving; China University of Mining and Technology Press: Xuzhou, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, B. High Strength Bolt Support Technology and Application to Mine Large Cross Section Seam Gateway. Coal Sci. Technol. 2011, 39, 5–8+18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.P.; Wang, J.H.; Lin, J. Case studies of rock bolting in coal mine roadways. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2010, 29, 649–664. [Google Scholar]

- He, M.C. Progress and challenges of soft rock engineering in depth. J. China Coal Soc. 2014, 39, 1409–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.F.; Li, S.J.; Zhou, Y.H.; Huang, Z.; Fan, T. Study on the fracture characteristics of sandstone and the effect of grouting reinforcement under different confining pressure. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2023, 19, 680–690. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.G.; Song, C.C. Mechanical and Acoustic Emission Characteristics of Grouted Reinforcement in Fissure-Containing Rock-like Specimens. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.Y.; Sun, Z.H.; Deng, M.; Xin, J.L. Grouting Technique for Gob-Side Entry Retaining in Deep Mines. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 5343937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.C. Research and application of new goaf retaining technology equipment in Shendong Mining Area. Coal Sci. Technol. 2022, 50, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.P. Development and prospects of support and reinforcement materials for coal mine roadways. Coal Sci. Technol. 2021, 49, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Qin, Q.; Jiang, B.; Jiang, Z.G.; He, M.C.; Li, S.C.; Wang, Y. Geomechanics model test research on automatically formed roadway by roof cutting and pressure releasing. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2020, 135, 104506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xu, S.; He, M.C.; Jiang, B.; Wei, H.Y.; Wang, Y. Dynamic mechanical characteristics and application of constant resistance energy-absorbing supporting material. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2022, 32, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Y. Research on collaborative control technology for surrounding rock pressure relief and support of gob-side entry. Coal Sci. Technol. 2020, 48, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.L.; Ma, S. Roof cutting gob-side entry retaining in high cutting face under complex stress disturbance. Coal Eng. 2020, 52, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.P. Active Pressure Relief Control Technology of Gob-side Entry Retaining with Roof in Composite Rock Stratum. Energy Energy Conserv. 2023, 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.S. Support-unloading combined technology for gob-side entry retaining in shallow high-cutting working face. Coal Eng. 2022, 54, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.P.; Liu, S.W.; Fu, M.X.; Peng, B.; He, Y.F. Research and application of influencing factors of key parameters of roof cutting and pressure relief by Dense Drilling. Coal Sci. Technol. 2023, 51, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L. Design of roof cutting and pressure relief in 103 working face of Changyuhe coal mine. Coal Mine Mod. 2022, 31, 13–15+20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.