Featured Application

Item retrieval in puzzle-based storage parking systems, incorporating diverse algorithms (e.g., A*) and heuristics (e.g., Manhattan distance, Chebyshev distance, and an occupancy-based variant). Ongoing work focuses on large-scale parking spot decomposition, enabling path searches in systems with a high number of parking spots.

Abstract

The increasing demand for efficient parking lots in urban environments has intensified research into puzzle-based storage parking systems. However, this high-density approach introduces challenges related to optimizing retrieval time and determining efficient vehicle access paths. Research shows that standardized testing platforms are needed to enable fair comparisons of algorithmic approaches in the puzzle-based storage (PBS) field. This study introduces a comprehensive, modular, and free environment for the systematic evaluation of shortest-path algorithms within PBS problems. The paper provides a practical example of the environment’s application and outlines future development perspectives. Moreover, the article provides a comparative analysis of vehicle retrieval performance across a spectrum of scenarios, including variations in parking lot dimensions, occupancy densities, movement strategies (orthogonal versus octilinear), and input/output point configurations. Experiments reveal that grid size, storage density, and depot placement significantly influence retrieval efficiency, computational complexity, and solution optimality, which is consistent with the literature. This study demonstrates that the environment encompasses all essential elements for conducting research and allows reliable comparisons of results across various algorithm implementations.

1. Introduction

Increasing efficiency, reducing errors, and lowering costs have, for years, transformed how work and common tasks are carried out across various sectors. These improvements have been achieved by eliminating the human factor, which plays a significant role across industry, services, and other areas. Technological progress and the development of intelligent transport systems contribute to the increasingly widespread adoption of autonomous solutions to improve the functioning of urban infrastructure.

Advanced driver assistance systems (ADASs) and autonomous vehicles are continually evolving, making driving safer and easier. Various positioning systems make it possible to reach the destination. The most common positioning system is the global satellite navigation system (GNSS), which is commonly used outdoors. The accuracy of this system is limited in highly urbanized areas, buildings, and other underground route buildings (e.g., carparks and tunnels). When GNSS signals are unavailable, alternative technologies and systems are used to determine position, such as ultra-wideband (UWB), Bluetooth, radio frequency identification (RFID), wireless fidelity (Wi-Fi), simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM), and vision cameras [1,2,3,4,5]. Relocating the vehicle would be infeasible and, more importantly, unsafe without the perception of the vehicle’s immediate environment. Sensors such as lidars, radars, or vision cameras are employed to monitor the surroundings. Thanks to these systems and algorithms for analyzing data derived from them, vehicle movement is becoming increasingly accurate and safe.

Driving and parking are tasks that many people perform multiple times every day—from ordinary people to professionals (e.g., forklift operators and truck drivers). Often, these activities are complex, and people’s responses are not quick enough. Fully or partially autonomous vehicles are being developed and deployed, with performance improving steadily, to reduce risk and increase efficiency in these tasks. Data analysis and control algorithms are also becoming increasingly refined. These apply not only to cars, buses, and trucks encountered on city roads but also to industrial vehicles, such as forklifts and automated guided vehicles (AGVs).

Autonomous parking systems, which are equipped on vehicles, are not new but are now increasingly common [6]. The systems integrated into the vehicle autonomously assess the availability of adequate parking space before executing the parking maneuver [7]. Realizing vehicle autonomy depends on a complex interplay of various positioning systems and environmental perception technologies. These systems work together seamlessly, utilizing advanced algorithms and, very often, artificial intelligence to create a comprehensive understanding of the vehicle’s surroundings.

Finding parking spaces in crowded car parks is also challenging, especially during rush hour [8]. One function of parking systems is to indicate available free parking spaces. Parking systems are no longer limited only to ADAS subsystems on board the vehicle but also to systems and software monitoring large areas that are located outside the vehicle.

In increasingly crowded cities, parking spaces are becoming smaller, making parking challenging or even impossible for less experienced drivers and autonomous parking assistant systems. A simple solution might be to increase the number of parking spaces. However, as noted, finding free space in city centers to establish new parking facilities is becoming more difficult. Parking lots are constructed both at street level and as underground or above-ground structures [9,10]. These structures increase parking capacity near city centers, where space is limited. Fully automatic parking facilities are also being developed, enabling vehicles to be parked automatically. In automated parking lots, human error can be eliminated completely, thereby minimizing the free spaces between vehicles. These solutions and systems are being examined not only for specialized parking structures but are also being adapted for existing open parking areas [11,12].

Increasing the number of parking spaces is not the only aspect in which parking systems in smart cities are analyzed [13,14]. The example aspects in which the car parks are studied are the structure of parking lots, the distribution of vehicles, and their number in the defined parking structure [15,16]. Parking management systems are being developed to optimize parking utilization and reduce the time required to find a space [17,18,19]. Automating access to private (with supervised access) parking lots is also an important issue not only for the parking supervisor but also for the drivers [20]. Due to the increasing popularity of electric cars, parking spaces that offer the possibility of charging vehicles are also important [21,22]. Parking space management systems that account for the need for vehicle charging must be efficient and address not only drivers’ needs but also those of parking lot owners.

However, parking assistants and intelligent parking lots are not, and will not be, sufficient in future cities, where parking spaces will be at a premium. The car parks that maximize the use of available space are those whose structures are based on the PBS system [23,24].

1.1. Related Works

PBS systems are designed to increase storage capacity in limited spaces. Utilizing these structures for car parks enhances parking availability in urban areas. PBS parking lots are being analyzed with a view toward their broader use, as are the algorithms being developed or tuned. The vehicle is not placed in a parking space by the vehicle itself or the driver but by specially designed AGVs (called shuttles). The shuttle picks up the vehicle from the input/output point (I/O point, depot) and then places it in a designated parking space. This process is fully automated and requires no driver intervention. Of course, each solution has its advantages and disadvantages. The disadvantage of the PBS parking system is the time required to place the vehicle in a parking space (often in a grid structure with identical field dimensions) and to hand it over to the driver. The key is the time required to hand over the vehicle, as the driver waits at a designated location.

In addition, PBS parking lots eliminate the need to use alleys. In turn, densely packed vehicles do not facilitate a rapid return to the driver due to the lack of available driving routes. Most traffic occurs in parking spaces, which are often occupied by other vehicles. Therefore, an important aspect is identifying a path that enables the vehicle’s return in the shortest possible time.

Various path-planning algorithms for PBS systems are presented in the literature. They differ in the traffic rules allowed by AGVs, system size (number of parking spaces), number of AGVs, number of I/O points, and pathfinding algorithm.

The fundamental algorithm in this field is Dijkstra’s algorithm, which is widely used for path planning and has also proven effective in other fields [25]. It allows the shortest path between nodes in a graph with non-negative weights to be found. Because it searches the entire solution space, determining the optimal path is computationally expensive. The solution to this problem is the A* algorithm, which uses heuristics to optimize path search [26,27]. This algorithm belongs to the group of best-first search algorithms and is widely used in the PBS retrieval problem. It explores the graph by developing the most promising node selected according to a specified rule. The A* algorithm is also combined with other algorithms, e.g., to generate a smoother path via interpolation [28]. The A* algorithm has high memory requirements. Its modification, the recursive best-first search (RBFS) algorithm, has lower memory requirements because it does not store all possible states and is more flexible in environments with incomplete information [29].

In [24], the authors developed two algorithms based on the A* graph algorithm. The first is an exact algorithm that proved suitable for small- to medium-sized parking lots (up to 10 × 10). The second algorithm is a heuristic variant suitable for large parking lots; the average time to find the extraction path in a 30 × 30 parking lot was less than 10 s. The sequences of moves returned by the heuristic algorithm deviated from the optimal ones. The authors indicate that future research may focus on movement planning approaches that minimize retrieval time rather than the number of retrieval movements or the number of multiple items.

In [30], the authors proposed a solution for managing a PBS system that utilizes AGVs instead of self-propelled shelves. The authors also assume a limited number of AGVs, which yields a lower-cost solution. The presented heuristic algorithm for retrieval path planning divides the parking lot into three regions (A, B, and C) and applies specific rules to each region. The presented simulations confirmed the effectiveness of AGVs in PBS systems. The authors emphasize that reducing the number of AGVs increases the complexity of the PBS management system because it requires planning not only the movements of the loaded but also the unloaded AGVs.

In [31], the authors presented an optimal and a heuristic method for the simultaneous retrieval of multiple items. The presented optimal method enables the simultaneous extraction of two items, whereas the heuristic method allows the extraction of up to three items. Results indicate that extracting multiple items simultaneously reduces movement time by approximately 20% relative to extracting them individually. The authors also tested their system in a parking lot simulation, assuming that there were always three drivers in the queue to pick up a vehicle. They chose the first car in the queue and the closest of the two remaining. In this scenario, they also achieved a minimum 20% reduction in waiting time.

In [32], the authors proposed a heuristic method for battery retrieval in a puzzle-based energy storage system. The authors assumed a 9 × 9 PBS and performed 15 simulations with varying numbers of I/O points (3 or 4) and their different locations. The number of elements retrieved simultaneously equaled the number of I/O points. In the proposed algorithm, sequential decisions based on the current PBS status are made to retrieve all target items toward the I/O with a minimum number of steps. The average computing time was 6.6 s.

Due to the variety of implementations of the A* algorithm and other pathfinding algorithms, it is difficult to assess the quality of the resulting path and to compare results. The lack of an open-source, free, unified simulation environment for testing solutions in the context of PBS parking lots impedes straightforward analysis and reliable comparison. The lack of a common simulation environment has also been noted by other researchers [33]. Consequently, researchers are forced to create dedicated simulation software from scratch each time. For this purpose, numerical computing environments and high-level programming languages, such as MATLAB [31] or Python [23,32], are used. Each team implements its own tools for simulation, motion logic, initial state generation, and visualization, which is a time-consuming process, and the resulting platforms are not shared (see Table 1). Determining the components of the environment described in the literature is sometimes challenging. For instance, it is unclear whether a visualization module exists, whether bulk tests can be performed, whether tests must be entered manually, or how computation time is calculated. Therefore, a common environment is needed to enable a fair comparison of different algorithms and their modifications, which is proposed in this work.

Table 1.

The features and code availability of PBS in papers.

1.2. Open-Source Environment

In this paper, an open-source environment for testing shortest-path algorithms is proposed to address a gap in the field. The prepared environment for pathfinding provides a solid basis for testing various algorithms for smart parking lots and is freely available on GitHub (https://github.com/). Modularity allows for easy modification and adaptation to specific problems. Each module can be modified independently of the others, enabling rapid testing of individual changes. The entire environment is written in C++ and requires no additional paid components or libraries. The environment can be compiled on any system that has a C++ compiler. The independent test scenario description module enables the preparation of a transferable standard set of test scenarios that allows verification of whether a given algorithm modification is better or worse overall or in a specific application compared with others. Bulk testing allows an algorithm to be evaluated on a large test set, thereby simplifying the testing of developed algorithms or their modifications. This is particularly important because testing can take several days, depending on the algorithms and heuristics being tested, the available hardware resources, and the size of the parking lots being analyzed. Using the proposed environment, researchers can test their algorithms without implementing the components responsible for test preparation, test execution, or visualization. The unified environment saves time and makes it easy for other researchers to reproduce and modify the proposed algorithm.

The prepared environment described in this paper was evaluated using the A* algorithm. The shared repository includes all essential modules required for seamless functionality, along with sample scenarios that demonstrate setups and use cases. The scenario number is provided as an application launch parameter. It is straightforward to extend the system with new scenarios. To support efficient development and testing, the repository also includes scripts that streamline compilation and enable bulk testing, ensuring users can easily deploy and evaluate the system across a range of test cases. The results for the following test scenarios are included and presented in this paper: different parking sizes, parking densities (cars), movement strategies, number of depots (I/Os), and depot configurations.

1.3. Paper Organization

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the A* algorithm used in the library. Section 3 shows how to use the library and presents the result of an example retrieval problem. Section 4 discusses the results of different test scenarios. Section 5 summarizes the results obtained and indicates the direction of library development.

2. Materials and Methods

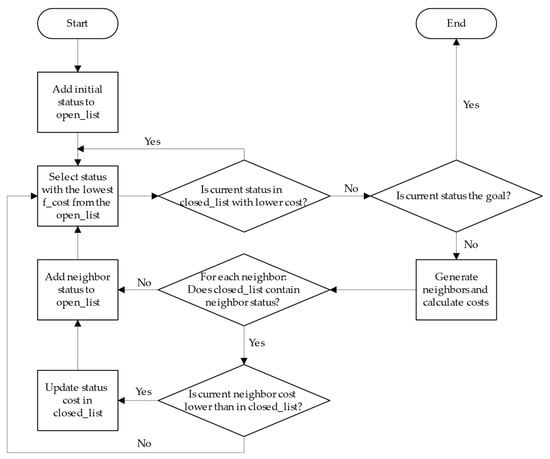

The pathfinding problem in the PBS system may be formulated as a weighted graph search. Each state corresponds to a specific vehicle arrangement, while transitions represent elementary moves—shifting a car to a neighboring escort. The goal is to reach a state where the target car occupies the destination position. This discrete structure makes graph search algorithms appropriate tools for finding the item-retrieval path. Among them, this work focuses on the A* algorithm. It expands the most promising nodes first, i.e., those with the lowest estimated total cost (f_cost), defined as the sum of the best-known cost to reach the current state from the start (g_cost) and the heuristic function (h_cost). If the heuristic is admissible, i.e., it always underestimates the actual cost or gives the actual cost, then the solution found will always be optimal. The A* algorithm is widely described in the literature [24,33,34]. The block diagram of the implemented A* algorithm and the pseudocode are presented in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively.

Figure 1.

A block diagram of the A* algorithm.

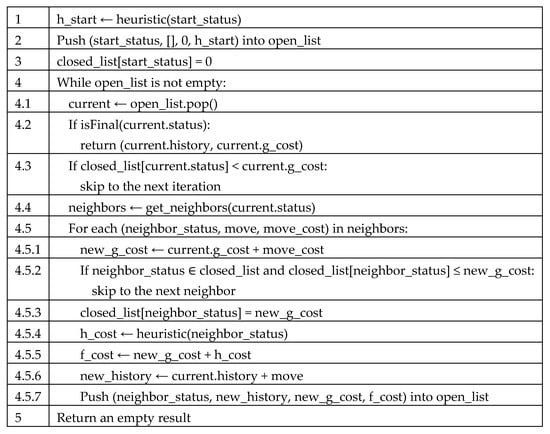

Figure 2.

A pseudocode of the A* algorithm.

The block diagram of the A* algorithm illustrates the systematic process for identifying the shortest path from an initial parking space to an I/O point (a goal node). The A* algorithm begins by initializing the open and the closed lists. The open list is a priority queue that stores nodes (parking states) to be explored, sorted by their f_cost, so the status retrieved from the open list is always the one with the lowest f_cost. The closed list is a hash map that stores the g_cost of each visited status to prevent revisiting statuses with worse paths. The algorithm iteratively selects the state with the lowest f_cost from the open list, checks if it is the final state, and generates neighboring states with their associated costs. Each neighbor is evaluated, and if a better path is found, it is added to the open list. The path is represented as a sequence of move identifiers, where each identifier records the specific action that transitions one status to another. For example, a move identifier could represent shifting a car from position (3,3) to (2,3). This allows the algorithm to provide a step-by-step replay of the solution path when reaching a goal.

The computational complexity of the A* algorithm depends on the quality of the heuristic and on the length of the optimal path to the goal, referred to as the search depth . In the case of a perfect heuristic that always predicts the exact cost, the time complexity is linear in , since the algorithm immediately follows the optimal path. Conversely, in the worst-case scenario, the computational complexity becomes , where is the branching factor of the graph.

The library is built around four core modules that enable flexible and efficient pathfinding (see Figure 3). The Status module enables representing the current state of the puzzle, tracking occupied positions and available movement spaces, and provides functions for generating and managing different configurations. The heuristic module defines cost estimation functions that help guide the search process by prioritizing which nodes to explore based on their estimated distance. The Neighbors module determines valid movements from a given status, defines rules for movement, and calculates the associated costs. Finally, the Route-Finding module implements search algorithms such as A* and Dijkstra’s, integrating heuristic evaluations and neighbor expansions to compute optimal retrieval paths.

Figure 3.

A block diagram of the introduced environment.

The library also includes three auxiliary modules. The Solution module converts between solution representations—state to move sequences and vice versa. The Visualization module provides methods to visualize the parking state or the retrieval path. The Is-Final module defines goal-checking functions to determine if the algorithm has successfully found a solution.

By extending or modifying the implemented scenarios, users can adapt to a variety of puzzle-based problems and systematically evaluate search strategies under different conditions. To evaluate the strategy on a large number of trials, multiple parking states may be randomly generated. The number of occupied cells is given as an input parameter. The procedure selects which positions are occupied by performing a random shuffle (using the Mersenne Twister pseudo-random generator) of the complete set of valid grid coordinates and extracting the required subset. Subsequently, the target car is defined by randomly designating one of the occupied positions as the target. This method guarantees that every possible configuration for a given number of occupied cells is equiprobable.

3. Examples

The repository includes a range of scenarios that demonstrate different use cases and capabilities of the library. These scenarios feature both orthogonal and octilinear movement strategies, configurations with multiple I/O points, and other features. They draw on various heuristics, neighbor-expansion rules, and custom criteria to determine when a desired status is achieved (for example, whether a target vehicle occupies a specified destination).

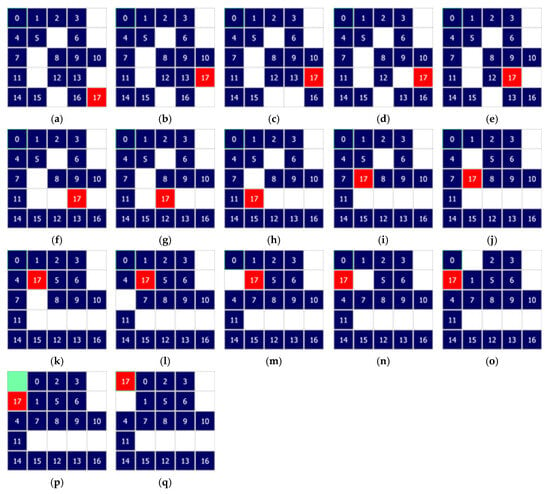

Figure 4 illustrates a single-item retrieval using orthogonal movement with one I/O point located in the corner as an example of library usage.

Figure 4.

Example of preparing a test scenario using the developed library.

Figure 5 presents the steps of the solution found by the library. The example involves a parking lot with 25 parking spaces (5 × 5). The depot is located in the top left corner. The blue blocks mean parking spaces occupied by cars. The red block represents the parking space occupied by the vehicle to be retrieved from the parking lot. The white blocks denote escorts. The movement is carried out immediately if escorts are on the designated route (Figure 5a,b,g,h). If another vehicle stands on the designated road, it should be removed from the road using escorts (Figure 5c–f,i–p). In the final step, the vehicle is transferred to an I/O point and removed from the parking lot (Figure 5q).

Figure 5.

The algorithm determines the following steps to remove vehicle no. 17. (a) initial state of the parking; target vehicle at position (4, 4); (b) vehicle no. 17 moved from (4, 4) to (4, 3); (c) vehicle no. 16 moved from (3, 4) to (4, 4); (d) vehicle no. 13 moved from (3, 3) to (3, 4); (e) vehicle no. 17 moved from (4, 3) to (3, 3); (f) vehicle no. 12 moved from (2, 3) to (2, 4); (g) vehicle no. 17 moved from (3, 3) to (2, 3); (h) vehicle no. 17 moved from (2, 3) to (1, 3); (i) vehicle no. 17 moved from (1, 3) to (1, 2); (j) vehicle no. 5 moved from (1, 1) to (2, 1); (k) vehicle no. 17 moved from (1, 2) to (1, 1); (l) vehicle no. 7 moved from (0, 2) to (1, 2); (m) vehicle no. 4 moved from (0, 1) to (0, 2); (n) vehicle no. 17 moved from (1, 1) to (0, 1); (o) vehicle no. 1 moved from (1, 0) to (1, 1); (p) vehicle no. 0 moved from (0, 0) to (1, 0); (q) vehicle no. 17 moved from (0, 1) to (0, 0).

At least one escort must be present in the parking lot to allow the vehicle to be retrieved. The number of escorts (and therefore the number of spaces occupied by vehicles) affects the time required to find a solution (path and movements) and to retrieve the vehicle from the parking lot.

4. Results

All tests were conducted on a system running Ubuntu 24.04.1 LTS with a kernel version of 4.4.0-19041-Microsoft under the Windows Subsystem for Linux (version 2.4.10). The hardware included an AMD Ryzen 5 2600 Six-Core Processor, providing 12 logical cores at a maximum frequency of 3.4 GHz, and 39 GB of total memory (approximately 32 GB available during the tests).

The experiments were built around single-item retrieval tasks in a PBS system. An item was randomly selected for every trial and has to be retrieved from its location to the I/O point. Each grid cell was modeled as a square of 5 m.

As a heuristic, a variant of the Manhattan distance was used that accounts for not only the distance from the target car to the destination but also the number of vehicles between them. Three metrics were recorded throughout experiment runs: the number of steps in the resulting path, the total path distance, and the execution time (in milliseconds) taken to produce a solution.

4.1. Impact of Parking Size

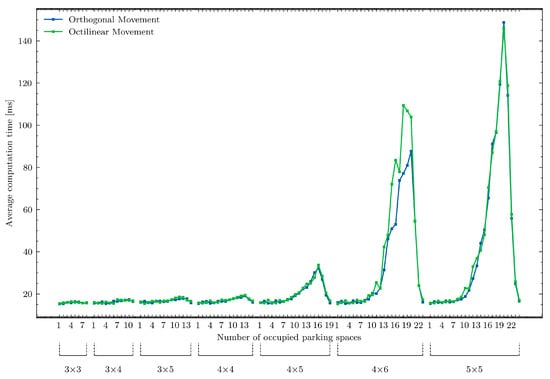

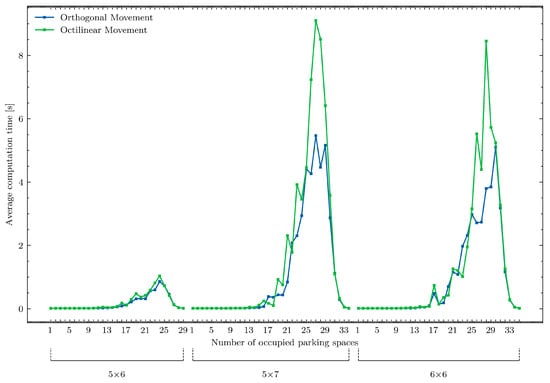

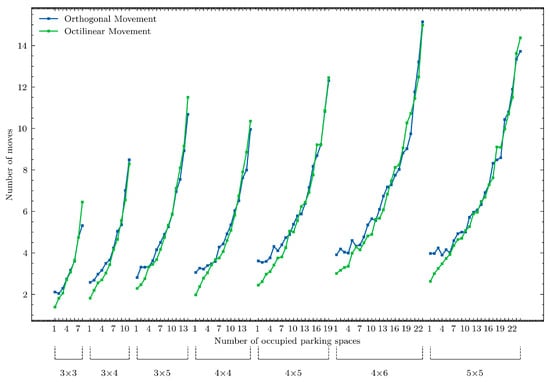

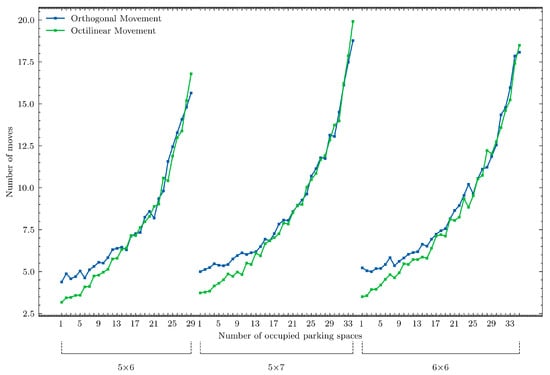

A set of experiments examined how computation time, path length, and the number of steps required for retrieval vary with grid size. Grid sizes ranged from 3 × 3 to 6 × 6, and fill levels ranged from 1 to max_fill—1. For each unique combination of grid size and fill level, the retrieval task was repeated 200 times (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Average computation time due to the parking size and the number of occupied parking spaces.

The results (see Figure 7) show that while smaller grids (3 × 3 and 4 × 4) maintain relatively stable computation times and lower computational costs, moving to larger grids (5 × 5 and 6 × 6) increases computational cost dramatically (for microscale simulation).

Figure 7.

Average number of moves due to parking size and number of occupied parking spaces.

There is a decrease in the number of retrieval moves when transitioning from a 3 × 5 parking to 4 × 4, from 4 × 6 to 5 × 5, and from 5 × 7 to 6 × 6—even though the latter grids may offer more potential parking spaces. This suggests that using parking lots with equal row and column counts can yield better performance in puzzle-based storage. Furthermore, highly elongated rectangular layouts (in which one dimension substantially exceeds the other) tend to behave more like standard parking configurations than to provide the benefits typically associated with puzzle-based systems.

The mean execution time significantly exceeds the third quartile, indicating that the distribution is skewed by high values (see Table 2). In PBS systems, item retrieval complexity varies widely; among randomly selected parking states, some are naturally much easier to solve than others.

Table 2.

Execution time statistics of the experiment—orthogonal and octilinear movements.

While execution time is skewed by high values, the number of moves follows a more standard distribution (see Table 3). The mean remains close to the first and third quartiles, indicating that solution length is not disproportionately driven by extreme outliers and that it scales predictably with system size.

Table 3.

Statistics on the number of movements in the experiment—orthogonal and octilinear movements.

4.2. Effect of Storage Density

In this experiment, the fill level (occupancy) was varied from nearly empty to nearly full to represent a wide spectrum of actual storage densities. The fill level denotes the number of cells in the total grid that are occupied at any given time. A notable outcome is the significantly higher computation time at intermediate fill rates, around 80%, compared to grids that are nearly empty or nearly full. When the grid is almost empty, vehicles can move more freely with fewer path constraints to consider. When the grid is nearly full, fewer valid moves remain, thereby limiting the search’s branching factor. At intermediate fill levels, however, the algorithm must evaluate a larger number of potential moves and rearrangements.

The number of steps and the distance required to retrieve an item increase steadily as the fill level rises. However, this linear progression does not apply to computational time. In a 5 × 7 grid, the average computation time is longest if 27 of 35 spaces are occupied for both octilinear and orthogonal movement (see Figure 8). This is consistent with the challenges introduced when a grid is neither sparse nor fully packed. The increased complexity arises from navigating around a moderate but still variable number of obstacles, which expands the possible rearrangements and prolongs the pathfinding process.

Figure 8.

The average computation time for a 5 × 7 parking.

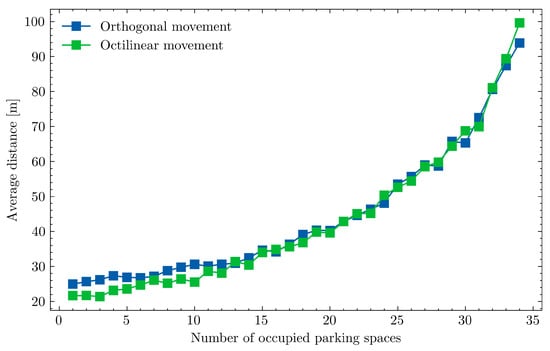

4.3. Movement Strategies: Orthogonal vs. Octilinear

Orthogonal (axis-aligned) movement restricts motion to up, down, left, and right steps. This approach is typically simpler to compute because the algorithm only considers movement in four directions. Octilinear movement includes both the orthogonal directions and additional diagonal moves. Diagonal moves require not only that the diagonal cell itself be unoccupied but also that the two adjacent axis-aligned cells be unoccupied to avoid corner collisions.

Allowing diagonal movements (octilinear movement) typically led to fewer steps in the solution path and a corresponding reduction in total path distance, with these benefits most pronounced when the grid had low fill levels (see Figure 9). In contrast, the potential for diagonal movement was diminished when the grid was nearly full. Consequently, there was little difference between the two movement strategies at high fill levels since diagonal paths were rarely available. Furthermore, the overhead of verifying multiple cells increased the processing time. Therefore, there remains a clear trade-off between path optimality, which is enhanced by diagonal moves at low fill levels, and the increased computational demands of managing diagonal pathfinding in heavily occupied puzzle-based storage environments.

Figure 9.

The average distance for 5 × 7 parking.

4.4. Multiple Input/Output Points

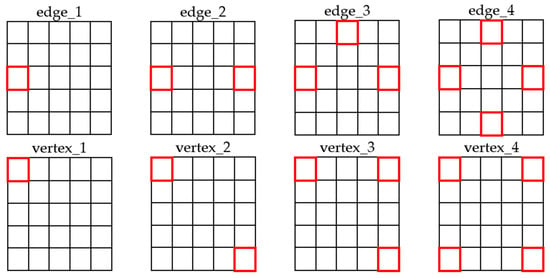

The first experiment used a single I/O point (depot) at coordinate (0,0). A subsequent experiment introduced multiple I/O points in a 5 × 5 grid, placing them along edges or at vertices. Each configuration, defined by placement (vertex or edge), number of I/Os, fill level, and chosen movement strategy, was run 2000 times. Figure 10 shows the tested depot configurations.

Figure 10.

The tested I/O points configurations.

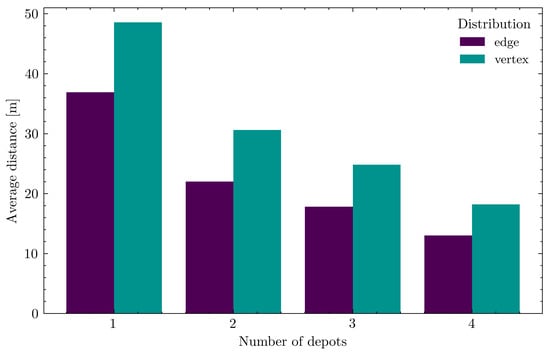

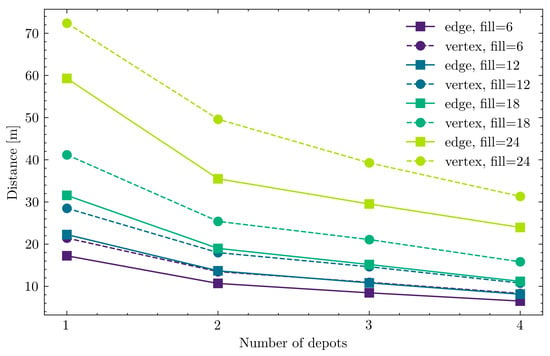

When more depots are available, the algorithm can often locate an efficient route that terminates closer to the item’s starting point, lowering overall pathfinding effort. These findings suggest a potential approach for puzzle-based storage systems, in which distributing multiple depots can reduce congestion and algorithm execution time. With edge-based placement, items are typically retrieved in fewer steps, over shorter distances, and with less computational time than with vertex-based placement (see Figure 11 and Figure 12).

Figure 11.

The average distance for 5 × 7 parking with 20 occupied parking spaces.

Figure 12.

Average execution time for 5 × 7 parking with 20 occupied parking spaces.

Edge-based I/O points consistently outperform vertex placements across all fill levels (see Figure 13). This advantage is geometric: the average distance from an edge midpoint to any grid cell is smaller than the average distance from a corner. Consequently, edge depots yield shorter retrieval paths.

Figure 13.

The average distance to several parking lots filled with different numbers of depots and their distribution.

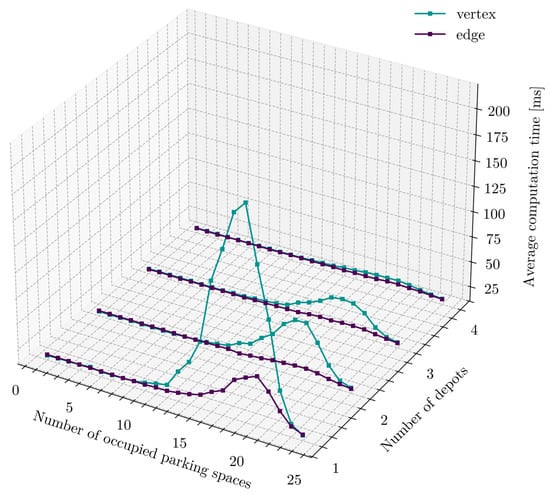

The mean and standard deviation of the execution time (see Table 4) decrease with increasing I/O counts, indicating that more I/Os simplify the problem and reduce the number of outliers. This is consistent with expectations, as more I/Os make it easier to identify a path to vehicle retrieval. A similar situation applies to the distance traveled (see Table 5): a larger number of I/Os enables the identification of a shorter path to vehicle retrieval. However, it is important to note that the I/Os are not concentrated at a single location in the presented cases.

Table 4.

Execution time statistics of the experiment—I/O distribution and count.

Table 5.

Distance statistics of the experiment—I/O distribution and count.

The grid is largely unoccupied at very low fill levels, enabling the pathfinding algorithm to quickly locate a route, regardless of whether depots are placed at edges or corners. Consequently, the time required for both strategies remains comparatively low and similar. At very high fill levels, the search becomes equally complex for both edge and vertex depots. In such near-saturated conditions, both configurations face similar constraints, resulting in comparable computation times and narrowing the gap between edge-based and vertex-based depots.

Edge-based I/Os show a clear time advantage at intermediate fill levels—around 80% occupancy. Under these conditions, there are still enough unoccupied cells for routing flexibility, allowing items near edges to be retrieved more directly. At the same time, the partially filled grid forces navigation of more roundabout paths to vertex-based I/Os, increasing computational effort.

5. Discussion

The most important element of the presented tests is the analysis of the locations and number of I/Os, as this aspect has not yet been examined in detail in the literature. Typically, one option is selected: vertices or edges, or some are on both edges and vertices simultaneously [24,32,35].

In [32], the authors also noted insufficient analysis of this problem and presented test results across various distributions and I/O counts (grid size 9 × 9). However, these tests were conducted on single trials, which does not allow for generalization of the results. Based on the results presented, no trends can be identified to support a specific solution. The tests presented in Section 4 (grid size 5 × 5) were repeated 2000 times for each configuration: I/O distribution (vertex or edge), number of I/Os, fill level, and chosen movement strategy. The number of tests supports generalization and indicates that placing the I/O on the sides yields better results. As the number of I/Os increases, the difference between I/Os’ locations decreases.

A comprehensive summary of computation time as a function of the number of depots and occupied cells for both depot configurations (vertex and edge) is presented in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Average computation time due to parking lot fill and the number of depots.

Tests of orthogonal and octilinear movements show that octilinear movements yield shorter solutions than orthogonal movements, but this comes at the cost of longer computation time. Above 50% parking capacity, this advantage disappears because diagonal movements are few or absent. Therefore, when parking capacity exceeds 50% (see Figure 7), there is no measurable benefit to using octilinear movement in terms of distance traveled. However, for capacities below 50%, it is still worthwhile to use octilinear movements because, with appropriate hardware resources, computation time will be shorter than the time required to retrieve the vehicle. This dependence decreases as the number of I/O points increases (see Table 5).

The computational complexity of the A* algorithm depends strictly on the heuristics used. The time required to obtain a solution is less crucial than memory dependencies. The algorithm stores solutions for all nodes, and the number of solutions grows exponentially with the solution length. For larger parking lots and limited memory resources, decomposing the problem into smaller ones is required. Decomposition can involve statically dividing the large parking lot into smaller sectors , each with its own I/O point and at least one escort. This solution reduces the maximum parking lot capacity by (assuming the parking lot has only one global I/O point). Moreover, in such a solution, a method and criteria must be defined to determine which sectors to use for vehicle retrieval, as searching through all possible solutions will not yield any benefit.

A separate issue is the system’s energy efficiency and the physical parameters of the AGV (acceleration, maximum speed, and lift time), which can also be used to find a better solution, for example, in terms of retrieval time or energy requirements. In such a case, the smaller number of steps or distance will not always be dominant because, depending on the AGV parameters, it may turn out that a slightly longer path will require fewer vehicle relocations (using escorts), which in turn will lead to a faster retrieval of the vehicle (assuming that the time and energy needed to lift the vehicle is higher than to travel a path).

Limitations

In more complex parking configurations, the A* algorithm implementation used in this research may run out of memory (RAM). As indicated in the literature, the RBFS algorithm is a solution to this problem. The RBFS algorithm does not store all visited states, yet it still yields promising results. Another solution is a different representation of the parking status. In the presented environment, the parking status is stored as a bool (1 byte) vector. The same information may be stored on 1 bit. Status might be represented as a bitboard—for example, a uint64_t can represent an 8 × 8 parking fragment; bitwise operations would be used to apply moves. This approach can be difficult to analyze, limiting the ability to implement changes to the presented algorithm quickly. Nevertheless, this approach is recommended for the final solution or implementing the solution on programmable logic devices.

In its current state, the environment does not include the implementation of functionalities such as simultaneous multi-item retrieval, optimization for minimum movement time or energy consumption (which would account for AGV acceleration or maneuvering costs), and multi-level parking lots. The last limitation can be decomposed into a single-floor problem, assuming that vehicles are not moved between floors but only to the I/O points (elevators).

Further work will focus on implementing additional heuristics and search algorithms, such as RBFS, as well as on functionalities currently constrained by the environment. Furthermore, the plan is to address the parking lot’s memory constraints by decomposing the problem into smaller subproblems.

6. Conclusions

The prepared testing environment is a ready tool for developing pathfinding algorithms, heuristics, and test scenarios for a PBS system parking lot. The modular architecture allows for easy customization of the environment to suit researchers’ needs. It also allows for the modification of a single component without requiring the reconstruction of the others. The unified environment allows for a fair comparison of different solutions. The presented results show that the library enables straightforward analysis of the prepared algorithms. The results obtained for different parking lot sizes are consistent with those from other studies, e.g., [24] However, when comparing the results, attention should be paid to the way they are presented. In [24], the X-axis shows the number of escorts (i.e., unoccupied cells), whereas in this paper, it shows parking lot occupancy (occupied cells), which is why the peaks appear at the end of the graph rather than at the beginning.

The presented analysis shows differences in the times required to compute and retrieve vehicles from the PBS parking lot, attributable to variations in depot configurations and numbers, parking lot occupancy (density), and movement types (orthogonal, octilinear). The placement of the I/Os and their number were carefully analyzed. Tests clearly indicate that placing the I/Os on an edge rather than a vertex reduces computation time and the distance the AGV must travel to retrieve a vehicle.

In the presented tests, the parking lot with 36 parking spaces was considered large-scale for the presented microscale simulation because of the time required to determine the path and the movements required on the average PC. This value is not large in the context of automated parking lots, but it illustrates the problem at a microscale.

The experiments indicate the need to decompose problems at a larger scale into smaller ones, which is one direction for further development of the presented library. This reduces exponential growth in the search space and keeps pathfinding computationally manageable, even in vast parking lots or warehouses.

This environment will remain open and will be further developed. The next direction for further development is considering real-world variability in cell dimensions. Rather than assuming uniform squares, the algorithm could factor in rectangular cells, potentially increasing computational overhead but yielding more accurate routes. Incorporating acceleration and braking costs would further align simulations with practical scenarios, where moving straight is generally more efficient than constant turning. Accounting for these dynamics adds complexity but captures real vehicle or robotic navigation more faithfully.

Additionally, prioritizing energy consumption within the objective function introduces a sustainability focus. Minimizing acceleration and braking not only reduces fuel or power use but also balances speed and ecological considerations, promoting greener logistics solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.P.; methodology, K.P. and K.W.; software, K.W.; validation, K.P., J.P., K.W. and D.G.; formal analysis, K.P., J.P. and K.W.; investigation, K.W.; resources, K.P., J.P., K.W. and D.G.; data curation, K.W.; writing—original draft preparation, K.P., K.W. and J.P.; writing—review and editing, J.P. and D.G.; visualization, K.W.; supervision, K.P., J.P. and D.G.; funding acquisition, J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education, partially by Statutory Research, and partially by Young Researchers funds of the Silesian University of Technology. It was partially supported by the Reactive Too project that has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research, Innovation, and Staff Exchange Programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Action (Grant Agreement No. 871163). Scientific work published as part of an international project co-financed by the program of the Minister of Science and Higher Education, entitled “PMW” in the years 2021–2025; contract no. 5169/H2020/2020/2.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The library that supports the findings of this study is available on GitHub at https://github.com/krzsztfwtk/puzzle-based-storage-library (accessed on 13 January 2026).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADAS | Advanced Driver Assistance System |

| AGV | Automated Guided Vehicle |

| GNSS | Global Satellite Navigation System |

| UWB | Ultra-Wideband |

| PBS | Puzzle-Based Storage |

| RBFS | Recursive Best-First Search |

| RFID | Radio Frequency Identification |

| SLAM | Simultaneous Localization And Mapping |

| Wi-Fi | Wireless Fidelity |

References

- Paszek, K. UWB System for Frequent Positioning of Moving Objects. In Information Systems; Themistocleous, M., Bakas, N., Kokosalakis, G., Papadaki, M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 535, pp. 299–310. ISBN 978-3-031-81321-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ziębiński, A.; Biernacki, P. How Accurate Can 2D LiDAR Be? A Comparison of the Characteristics of Calibrated 2D LiDAR Systems. Sensors 2025, 25, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzechca, D.; Ziębiński, A.; Paszek, K.; Hanzel, K.; Giel, A.; Czerny, M.; Becker, A. How Accurate Can UWB and Dead Reckoning Positioning Systems Be? Comparison to SLAM Using the RPLidar System. Sensors 2020, 20, 3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paszek, K.; Grzechca, D. Using the LSTM Neural Network and the UWB Positioning System to Predict the Position of Low and High Speed Moving Objects. Sensors 2023, 23, 8270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzechca, D.; Paszek, K. Short-Term Positioning Accuracy Based on Mems Sensors for Smart City Solutions. Metrol. Meas. Syst. 2019, 26, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, C.; Kim, C.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Sunwoo, M. Re-Plannable Automated Parking System With a Standalone Around View Monitor for Narrow Parking Lots. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transport. Syst. 2020, 21, 777–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, C.; Sunwoo, M. Semantic Segmentation-Based Parking Space Detection with Standalone around View Monitoring System. Mach. Vis. Appl. 2019, 30, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodi, R.; Rawat, D.B.; Rios-Gutierrez, F. Smart Parking: Parking Occupancy Monitoring and Visualization System for Smart Cities. In Proceedings of the SoutheastCon 2016, Norfolk, VA, USA, 30 March–3 April 2016; IEEE: Norfolk, VA, USA, 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Stranieri, S. An Indoor Smart Parking Algorithm Based on Fingerprinting. Future Internet 2022, 14, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Chung, M.H.; Park, J.C. Field Experiment Examining Condensation Reduction Methods Based on Underground Parking Lot Types. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 24, 1913–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paidi, V.; Fleyeh, H.; Håkansson, J.; Nyberg, R.G. Smart Parking Sensors, Technologies and Applications for Open Parking Lots: A Review. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2018, 12, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin Nieto, R.; Garcia-Martin, A.; Hauptmann, A.G.; Martinez, J.M. Automatic Vacant Parking Places Management System Using Multicamera Vehicle Detection. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 20, 1069–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljohani, M.; Olariu, S.; Alali, A.; Jain, S. A Survey of Parking Solutions for Smart Cities. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 10012–10029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Rivano, H.; Le Mouel, F. A Survey of Smart Parking Solutions. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2017, 18, 3229–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millard-Ball, A. The Autonomous Vehicle Parking Problem. Transp. Policy 2019, 75, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Sun, C. An Optimization Design of Hybrid Parking Lots in an Automated Environment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, M.; Solanki, S.G.; Natarajan, E.; Keat, T.M. IoT Based Smart Parking System for Large Parking Lot. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 4th International Symposium in Robotics and Manufacturing Automation (ROMA), Perambalur, India, 10–12 December 2018; IEEE: Perambalur, Tamil Nadu, India, 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.; Hamad, M.S.; Abdel-Khalik, A.S.; Hamdan, E.; Ahmed, S.; Elmalhy, N.A. Improved Utilization for “Smart Parking Systems” Based on Paging Technique. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 3375–3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkata Sudhakar, M.; Anoora Reddy, A.V.; Mounika, K.; Sai Kumar, M.V.; Bharani, T. Development of Smart Parking Management System. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 80, 2794–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, Z.; Haneef, O.; Muhammad, N.; Khattak, S. Towards a Fully Automated Car Parking System. IET Intell. Trans Syst. 2019, 13, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuran, M.S.; Viana, A.C.; Iannone, L.; Kofman, D.; Mermoud, G.; Vasseur, J.P. A Smart Parking Lot Management System for Scheduling the Recharging of Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2015, 6, 2942–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.A.; Rodrigues, J.M.F. Intelligent Monitoring Systems for Electric Vehicle Charging. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, P.J.; Gue, K.R.; Usher, J.S. Puzzle-Based Parking. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 127, 103112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, A.; Koberstein, A.; Schocke, K.-O. An Optimal and a Heuristic Algorithm for the Single-Item Retrieval Problem in Puzzle-Based Storage Systems with Multiple Escorts. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 143–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Jiang, H.; Hua, L. Anti-Congestion Route Planning Scheme Based on Dijkstra Algorithm for Automatic Valet Parking System. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, C.; Luo, Q.; Yan, X. Path Planning Using an Improved A-Star Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2020 11th International Conference on Prognostics and System Health Management (PHM-2020 Jinan), Jinan, China, 23–25 October 2020; IEEE: Jinan, China, 2020; pp. 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Wang, B.; Xu, H. Research on Path-Planning Algorithm Integrating Optimization A-Star Algorithm and Artificial Potential Field Method. Electronics 2022, 11, 3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Tang, C.; Claramunt, C.; Hu, X.; Zhou, P. Geometric A-Star Algorithm: An Improved A-Star Algorithm for AGV Path Planning in a Port Environment. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 59196–59210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatem, M.; Kiesel, S.; Ruml, W. Recursive Best-First Search with Bounded Overhead. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Austin, TX, USA, 25–30 January 2015; AAAI: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; Volume 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfieri, A.; Cantamessa, M.; Monchiero, A.; Montagna, F. Heuristics for Puzzle-Based Storage Systems Driven by a Limited Set of Automated Guided Vehicles. J. Intell. Manuf. 2012, 23, 1695–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, M.; De Koster, R.B.M.; Zaerpour, N. Modelling Load Retrievals in Puzzle-Based Storage Systems. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2017, 55, 6423–6435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Wang, J. A Heuristic Method for Route Programming in Puzzle-Based Energy Storage Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 7th Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), Hangzhou, China, 15–18 December 2023; IEEE: Hangzhou, China, 2023; pp. 2195–2200. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Y.; Qi, M. A Heuristic Method for Load Retrievals Route Programming in Puzzle-Based Storage Systems 2021. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.09274. [Google Scholar]

- Weerasinghe, K.V.; Sgarbossa, F. Performance Analysis for Puzzle-Based Movable Racks System with Diagonal Movements. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2024, 58, 1234–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, E.; Zolghadr, M. An Item Retrieval Algorithm in Flexible High-Density Puzzle Storage Systems. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2021, 4, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.