Abstract

Due to the unpredictability of seismic and the complexity of collection environments, significant uncertainty exists regarding their impact on cultural relics. Moreover, existing research on the causal analysis of seismic damage to cultural relics remains insufficient, thereby limiting advancements in risk assessment and protective measures. To address this issue, this paper proposes a seismic damage risk assessment method for cultural relics in collections, integrating deep learning and reinforcement strategies. The proposed method enhances the dataset on seismic impacts on cultural relics by developing an integrated deep learning-based data correction model. Furthermore, it incorporates a graph attention mechanism to precisely quantify the influence of various attribute factors on cultural relic damage. Additionally, by combining reinforcement learning with the Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) strategy, this method refines seismic risk assessments and formulates more targeted preventive protection measures for cultural relics in collections. This study evaluates the proposed method using three public datasets in comparison with the self-constructed Seismic Damage Dataset of Cultural Relics (CR-SDD). Experiments are conducted to assess and analyze the predictive performance of various models. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method achieves an accuracy of 81.21% in assessing seismic damage to cultural relics in collections. This research provides a scientific foundation and practical guidance for the protection of cultural relics, offering strong support for preventive conservation efforts in seismic risk mitigation.

1. Introduction

As invaluable cultural relics of human history and culture, the preservation and study of cultural relics in museums play a crucial role in advancing the understanding of human civilization [1,2]. With the increasing number of cultural relics being housed in museums, their centralized management enhances protection and preservation efforts. However, this concentration also significantly raises the risk of large-scale destruction in the event of sudden disasters. Natural disasters, particularly seismic events, pose a severe threat to cultural relics due to their unpredictability and destructive force, often resulting in irreparable losses [3]. The available datasets on the seismic impact on cultural relics remain limited and incomplete. Moreover, existing research on the damage mechanisms of seismic events lacks depth, significantly hindering advancements in seismic risk assessment and protection efforts for cultural relics. Consequently, there is an urgent need to enhance existing datasets on the seismic impact on cultural relics. Building upon this foundation, this study proposes a quantifiable risk assessment method to address the uncertainty associated with seismic impacts on cultural relics. This study leverages artificial intelligence and automation technologies to offer a novel perspective on the seismic impact on cultural relics.

Due to the invaluable nature and uniqueness of cultural relics, collecting seismic data from actual cultural relics presents significant challenges [4]. While imitation cultural relics are utilized in simulation experiments to obtain relevant data [5], discrepancies in material, structure, and other critical attributes between these replicas and actual cultural relics [6] introduce inherent biases between simulation and real-world data [7]. Furthermore, analyzing the damage process of cultural relics constitutes a complex system involving interactions among multiple factors, including material composition, structural integrity, age, and preservation conditions [8], all of which collectively influence the extent of seismic-induced damage. Existing research methods are predominantly experimental and often focus on isolated factors rather than comprehensively analyzing the intricate interactions within the system, thereby constraining the accuracy of risk assessments [9]. In the context of seismic risk assessment and preventive protection of cultural relics, existing studies primarily rely on machine learning models or experience-based prediction methods [10]. However, these approaches struggle to effectively handle complex dynamic systems, failing to comprehensively capture factor interactions and their evolving nature, which limits the validity and reliability of assessment results [11,12]. To enhance the accuracy of seismic risk assessment for cultural relics in collections and to improve the scientific foundation of preventive protection strategies, it is imperative to incorporate advanced artificial intelligence techniques, such as deep learning and reinforcement learning. These technologies facilitate a deeper exploration of the complex relationships among multidimensional data, including cultural relic attributes, environmental conditions, and seismic characteristics, enabling the development of a more comprehensive and precise assessment model. Building upon this foundation, the integration of intelligent optimization algorithms enables the formulation of targeted recommendations for seismic preventive protection measures, thereby offering robust technical support for the long-term preservation and transmission of cultural heritage.

In general, existing methods for seismic risk assessment of cultural relics in collections exhibit the following limitations: (1) the absence of accurate and comprehensive datasets on the seismic impacts of cultural relics in collections, primarily due to missing or biased data collection; (2) the influence of numerous factors on the seismic impact of cultural relics, making it challenging to quantitatively assess the significance of each contributing factor; (3) the absence of systematic seismic risk assessment models for cultural relics, limiting the ability of existing methods to provide efficient and personalized recommendations for preventive protection against seismic disasters. To address these challenges, this paper introduces a seismic damage risk assessment method for cultural relics in collections, leveraging deep learning and reinforcement strategies. The contributions are as follows:

- A data correction method based on integrated deep learning is introduced to incorporate simulated data from imitation cultural relics, thereby supplementing and refining the attributes of real cultural relic seismic damage data. This approach addresses the issues of missing data and inaccuracies within the dataset on seismic damage impacts.

- The SHAP algorithm is employed to analyze the seismic impact characteristics of cultural relics in collections and to examine the correlation between seismic factors and cultural relic damage. This analysis enhances the development of the ontology layer within the seismic knowledge map of cultural relics.

- The fusion graph attention mechanism is utilized to analyze the influence weights of seismic damage factors affecting cultural relics. This approach enables the construction of a seismic damage knowledge map and quantifies the impact of each attribute on the damage levels of cultural relics.

- A hybrid deep reinforcement learning approach is implemented to assess the risk of seismic-induced damage to cultural relics. This method examines the influence of various attribute data on damage levels and provides targeted recommendations for preventive protection measures against seismic events.

The remaining chapters of this paper are organized as follows: Section 2 reviews existing data mining and analysis techniques, as well as risk assessment methods; Section 3 presents the methodology employed in this study; Section 4 offers a comparative analysis of the refined dataset of seismic impacts on cultural relics and the risk assessment scenario; and Section 5 concludes the paper, outlining future research directions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Cultural Relics Data Processing Methods

With the rapid advancement of metrological equipment and information technology, the application of data processing techniques within the field of cultural heritage protection and research has become increasingly extensive. These methods have evolved from initial manual collection and statistical analysis toward the integration of deep learning and technological means, thereby providing significant convenience for the construction of cultural heritage datasets and conservation analysis.

During the acquisition of cultural heritage data, noise interference remains a prevalent issue. To address the challenges associated with complex data morphology, structural variations, sparsity, irregularity, and cross-data fusion encountered by traditional point cloud registration methods in processing cultural heritage data, the feasibility of employing convolutional neural networks for the rapid in situ recognition and classification of paper-based molds was investigated by Liu et al. [13]. Machine learning approaches were utilized by Chen [14] and Wang [15] to construct data processing models for artifact classification. Addressing the issue of incomplete data regarding the actual seismic impact on museum collections, a centroid localization method oriented towards small sample sets was proposed by He et al. [16] to determine the centroid attributes of artifact bodies. For the automatic extraction of surface damage information from fine 3D color models of painted artifacts, extraction methods based on fine 3D data and artifact segmentation methods based on multi-feature weighted random forest training were proposed by Hu [17] and Zhao [18], respectively. Additionally, a refined feature extraction technology for mural cracks, combining attention mechanisms with U-Net neural networks, was introduced by Cui et al. [19]. In terms of data preprocessing and correction, a data prediction method using a Long Short-Term Memory network optimized by a Bayesian algorithm (BO-LSTM) was proposed by Li et al. [20], which adopted moving average data smoothing techniques to enhance prediction accuracy. A method combining fractional mixed optimization with feedforward neural networks was created by Rathod et al. [21] to correct missing values and data errors during the preprocessing stage, thereby avoiding classification confusion. Furthermore, taking the Tang Dynasty tomb murals in the Shaanxi History Museum as a case study, an ontology model for mural-type cultural resources was constructed by Gao et al. [22] using a top-down approach, in which actual case data were imported into a Neo4j (2025.09.0) graph database according to a hierarchical structure.

Despite the significant convenience provided by these technologies for the protection, management, and research of cultural heritage, numerous challenges persist in practical applications. Due to the difficulty of cultural heritage data acquisition and the presence of partial data loss, it is often difficult for existing methods to perform effective corrections, resulting in a general lack of complete and precise artifact datasets within the museum domain. Simultaneously, current artifact data processing methods based on artificial intelligence remain relatively limited; although efficiency has been improved, there remains substantial room for improvement in processing precision.

2.2. Seismic Damage Risk Assessment Methods

Seismic damage risk assessment enables the evaluation of the probability and severity of potential safety risks to cultural artifacts based on existing conditions. In recent years, driven by technological progress, significant advancements have been achieved in the field of artifact seismic damage risk assessment [23]. Through the introduction of advanced detection technologies, intelligent analysis methods, and management systems, the scientific rigor, precision, and efficiency of this risk assessment process have been enhanced.

Regarding research on risk assessment methodologies, scholars have conducted explorations centered on graph design, impact analysis, and optimization modeling. A risk assessment knowledge graph was constructed by Liu et al. [24] through the optimization of event text augmentation algorithms, providing a framework for the structured understanding of risk factors. Under a dynamic probabilistic risk assessment framework, state-of-the-art structural models were employed by Kasapoglu et al. [25] to design conditional core damage probability estimates for benchmark earthquakes. To achieve efficient seismic risk and resilience assessment, a comprehensive framework based on performance-based earthquake engineering methods was proposed by Guo [26] and Dahal [27], who also established a two-level fuzzy comprehensive evaluation system. Seismic casualty assessment models capable of simultaneously considering multiple influencing factors were proposed by Ren [28] and Amaducci [29], respectively. Focusing on seismic risk, a single-layer multi-risk approach was adopted by Polese et al. [30], wherein each risk was evaluated through independent analysis. An updated vulnerability quantification strategy for seismic intensity scales was proposed by Li et al. [31], alongside the establishment of a risk assessment model based on improved macro-seismic measures. To simulate seismic damage more realistically, the impact of different ground motion models on hazard and risk estimation was investigated by Rudman et al. [32]. In the context of utilizing machine learning to optimize risk assessment models, the necessity of research via physical models was emphasized by Altun and Shi [33], who noted that comprehensive assessments of multiple natural events, such as earthquakes, are required. These studies collectively propel risk assessment methods toward more systematic and intelligent development.

Through damage risk assessment, potential risks to artifacts can be identified in a timely manner, allowing for the implementation of effective protection measures to ensure the safety and integrity of the artifacts. However, due to the specificity of cultural artifacts and the multiplicity of factors influencing seismic damage, existing risk assessment methods struggle to effectively evaluate the importance of each individual seismic impact factor. Additionally, currently, there is a lack of systemic damage risk assessment models specifically targeted at cultural artifacts, which hinders the provision of efficient and precise guidance for real-world applications.

2.3. Seismic Vulnerability Assessment of Cultural Heritage

Currently, the seismic vulnerability assessment of cultural heritage has transitioned from qualitative description to performance-based quantitative analysis. Mainstream methodologies primarily encompass numerical simulation based on the Finite Element Method (FEM), macro-element model analysis, and empirical assessment combined with on-site investigation. The research scope is also progressively expanding from the refined analysis of individual building entities to a multi-scale comprehensive assessment system that incorporates geological environments, urban textures, and the interaction of building clusters, aiming to provide a more scientific basis for decision-making in heritage conservation.

In the realm of refined assessment for individual buildings, significant progress has been achieved through the utilization of advanced detection and numerical technologies, with increasing attention paid to the intersection of structural performance and heritage value. A detailed assessment of historic buildings following earthquakes was conducted by Kilic [34] using multi-source data to determine structural status, prioritizing the physical integrity of valuable assets. For complex structures with unique geometric forms, in-depth seismic performance analyses were performed on a medieval bell tower and the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba by Nastri et al. [35] and Requena-Garcia-Cruz et al. [36], respectively. These studies revealed the dynamic response characteristics of high-rise and large-span historical masonry structures, effectively linking mechanical behavior to the preservation of architectural significance. To address the demand for rapid post-earthquake assessment, the feasibility of simplified finite element models was validated by Demircan [37]. in the analysis of partially collapsed historical mosques. Furthermore, the critical role of geotechnical solutions in mitigating seismic risk for heritage sites was emphasized by Fiamingo et al. [38]. At the regional and cluster levels, typical historical masonry churches in the Banat region were systematically investigated by Monaco et al. [39,40], where seismic performance was quantified via numerical simulation to establish typological paradigms. Regarding interactions within building clusters, Schiavoni et al. [41] compared different modeling approaches for adjacent structural units. Notably, recent advancements have begun to explicitly integrate value assessment with physical risk; for instance, a multi-attribute-based procedure was proposed by Mascheri et al. [42] to simulate seismic loss scenarios in historical urban areas. This approach attempts to quantify vulnerability not merely as structural failure, but as a function of the intrinsic cultural value at risk, marking a shift towards value-centered risk assessment.

The theoretical foundation of the aforementioned methodologies is predominantly rooted in structural mechanics and deterministic physical modeling. Whether employing high-precision finite element methods for micro-analysis or macro-element models for regional assessment, these approaches emphasize the explicit mathematical formulation of failure mechanisms, focusing on stress redistribution, displacement drifts, and material nonlinearity under seismic loading. These mechanism-based methods provide a rigorous physical explanation of damage evolution and serve as the bedrock for understanding structural stability. Complementing this mechanical perspective, the research presented in this paper introduces a data-driven paradigm to the vulnerability assessment of collection artifacts. By synthesizing the mechanical attributes inherent in these structural models into a high-dimensional feature space, this study aims to mine the latent correlations between seismic excitation and artifact damage. This approach transitions the assessment task from a purely boundary-value problem to a pattern recognition task, leveraging deep learning to capture the complex, nonlinear interactions that govern the susceptibility of cultural relics within their specific preservation environments. To provide a clear overview of the research landscape and highlight the gaps addressed by our proposed methodology, a synthesis of representative state-of-the-art findings is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Synthesis of state-of-the-art methods in cultural heritage and seismic risk assessment.

3. Uncertainty Analysis of Seismic Effects on Cultural Relics in Collections

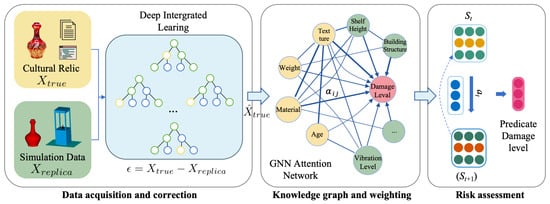

To provide a holistic view of the methodology, the overall framework is illustrated in Figure 1. The process consists of three interconnected stages: (1) Data Acquisition, where multi-source heterogeneous data are collected from historical archives and replica shaking table experiments; (2) Data Correction, where a deep integrated learning model aligns simulated data distributions with real-world characteristics to address data sparsity; and (3) Weighting and Assessment, where a Graph Attention Network (GAT) dynamically assigns importance weights to seismic factors, guiding the deep reinforcement learning agent in assessing risk and optimizing protection strategies.

Figure 1.

Schematic framework of the proposed seismic damage risk assessment method. The framework proceeds from raw data collection (real and simulated), through deep integrated learning for error correction and data augmentation, to the final risk assessment model driven by graph attention weights and reinforcement learning strategies.

3.1. Seismic Impact Dataset Refinement of Cultural Relics in Collections Based on Deep Integrated Learning

Various statistical categories exist for data related to the seismic impact on cultural relics. The dataset encompasses not only the ontological attributes of cultural relics but also contextual data related to their preservation environment and seismic activity. In this study, the seismic specification for cultural relics in Chinese collections is adopted as the baseline index to supplement and refine existing seismic impact datasets of cultural relics. Subsequently, a data attribute processing strategy is developed to address anomalies and missing values while eliminating noise introduced during the measurement process. Finally, missing data are supplemented with experimental data to enhance the dimensionality of the dataset, while integrated learning is employed to fuse multiple machine learning or deep learning frameworks, ensuring both data accuracy and reliability.

3.1.1. Seismic Impact Data Collection and Supplementation of Cultural Relics in the Collection

The dataset on the seismic impacts of cultural relics in collections comprises numerous detailed attributes, making it relatively comprehensive. In this study, the statistical analysis primarily focuses on the data attributes related to the seismic damage of cultural relics in collections. These attributes are further supplemented and classified into four primary categories: cultural relic ontology, exhibition and collection facilities, preservation space, and seismic information, each with its respective secondary classifications. The refined dataset encompasses comprehensive data attributes related to the seismic damage impact on cultural relics (see Table A1 in Appendix A). The collection of data on seismic-induced damage to cultural relics necessitates specialized professional knowledge and extensive practical experience. Following a seismic event, the heritage management department typically mobilizes experts and technicians for an immediate on-site assessment. Initial data on the damage sustained by cultural relics, along with the contributing factors, is systematically collected, thoroughly analyzed, and meticulously documented.

Given the unpredictability and destructiveness of seismic events, the limited application of monitoring technologies, existing technical constraints, and the challenges associated with data collection, accurately documenting and statistically analyzing the damage sustained by certain cultural relics remains difficult. During the construction of the seismic impact dataset for cultural relics, ensuring dataset completeness is a primary objective. This study not only compiles seismic and vibrational response data recorded from actual cultural relics under various conditions—encompassing damage records of the relics themselves, as well as contextual environmental data such as building structures, storage methods, and seismic information from past seismic events—but also conducts shaking table tests using simulated cultural relics in a controlled laboratory environment to obtain numerical data, such as floor acceleration time histories. In Figure 2, the data acquisition process for simulated cultural relics in a laboratory setting is depicted.

Figure 2.

Data acquisition process of imitation cultural relics.

3.1.2. Multi-Source Heterogeneous Data Preprocessed for Cultural Relics

Given the varying temporal and spatial resolutions of different data sources, data alignment and standardization are necessary to ensure the accuracy of seismic impact data on cultural relics and the consistency of measurement units. Additionally, signal processing techniques are employed to eliminate noise from both experimental and monitoring data. To address missing values and outliers, an automated template matching approach and detection methodology are developed. The specific detection steps are outlined in the following section.

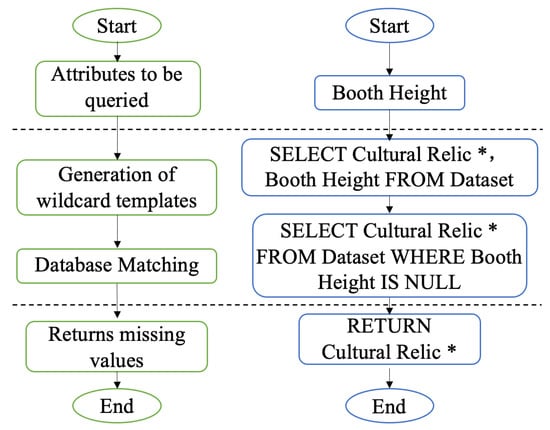

Step 1: Missing Value Detection. The existing database or table containing seismic impact data on cultural relics is examined. As illustrated in Figure 3, the process of querying cultural relic attribute information is depicted. The green section on the left represents the logical framework for heritage information retrieval, while the right side illustrates the actual data transfer process involved in automated template matching. Template matching is utilized to activate wildcard-based searches (where “*” serves as a wildcard) to locate cultural relics and their corresponding collection values. This enables the identification of missing values through template queries, ensuring that any missing data are remeasured and supplemented accordingly.

Figure 3.

Missing value detection process. “*” represents the search results.

Step 2: Outlier Detection. The dataset containing attributes related to the seismic impact of cultural relics, such as age, material, and shape, is used to define the item set I as a combination of several attributes. For a given item set I, the support is defined as the frequency of occurrence of the item set, which is the ratio of the number of times the item set appears in the entire dataset to the total number of records. The calculation process is presented in Equation (1).

Here, denotes the number of occurrences of item set I in the dataset, and n represents the total number of cultural relics records in the dataset. The support threshold is set to distinguish between frequent and rare item sets. If , the item set I is classified as a frequent item set, representing a common combination of attributes. Conversely, if , the item set I is considered a rare item set, representing unusual or unreasonable combinations. The anomaly score is computed for each cultural relics record r, defined as the degree of deviation from the frequent item set. The anomaly score increases if all combinations of the cultural relics’ attributes are rare items, as shown in Equation (2).

Here, denotes the set of combined items for each attribute of the cultural relics r. A lower indicates a rarer set of items, resulting in a higher . By setting an anomaly scoring threshold , if , the cultural relics data can be classified as a potential outlier.

Step 3: Outlier Processing. For the abnormal data items in the dataset, the normal data points are grouped into a reference set , and all data points containing abnormal values are recorded. Each abnormal value is treated as a separate target. For each abnormal data point , its distance from all normal data points is calculated. The Euclidean distance is used in the calculation process, as shown in Equation (3).

3.1.3. Simulation Data Correction Based on Integrated Learning

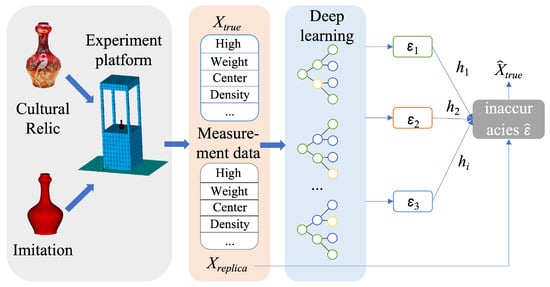

Due to the value of cultural relics, it is challenging to directly obtain their ontological measurements and conduct experiments to gather the relevant attributes. Therefore, for the missing and unaccounted data on the seismic impact of these relics, laboratory tests using imitation cultural relics on shaking tables are employed. However, differences between imitation cultural relics and real cultural relics result in errors between the measured data and the actual values. To address this, this paper proposes an integrated learning architecture to correct the error by learning the nonlinear relationship between the attributes of imitation cultural relics and the error using a multi-group approach. The data correction process for imitation cultural relics based on integrated learning is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Data correction of imitation cultural relics based on integrated learning.

First, the measurement error and the target model are defined. The attribute representing the seismic impact of cultural relics is denoted as X. represents the measured value of the imitation cultural relics, including data attributes such as weight, density, volume, and others. represents the known measured value of the real cultural relics. represents the error between the measured value of the imitation cultural relics and the real value. The error is then represented by Equation (6):

Based on this, the target model is constructed to predict the error based on the measurement property of the imitation cultural relics. This model is used to correct the measurement values of the imitation cultural relics to better approximate the real values.

Next, the integrated learning error prediction model is developed. In this paper, the random forest method is used to construct multiple decision trees and average the results. The prediction provided by the random forest model represents the error between the real value and the value of the imitation cultural relics. The random forest model is expressed as the integration of multiple decision trees , as shown in Equation (7):

Here, n represents the number of decision trees, and refers to a single decision tree.

Finally, model training and data correction are performed. Bootstrap sampling is used to randomly select data from the training set to construct a training subset for each tree. At each node of every tree, a subset of features is randomly selected for splitting to increase model diversity and reduce overfitting. Decision trees are constructed for each random subset, with the depth of the tree and the splitting method controlled by the hyperparameter n. Each tree is trained independently to model the nonlinear relationship of the error. The measured data of the replica cultural relics are input into the trained random forest model to obtain the error prediction . The measurement data of the replica cultural relics are corrected based on the error prediction , allowing the attributes to approximate those of the real cultural relics, as shown in Equations (8) and (9).

3.2. Cultural Relics Seismic Impact Factor Analysis by Fusion Graph Attention

The mechanism by which seismic events impact the destruction of cultural relics is complex, involving not only the texture, center of gravity, and other characteristics of the relics themselves, but also factors such as the height of the storage location, the material of the contact surface, and other spatial attributes related to the preservation of the relics. Therefore, to quantify the impact mechanism of seismic damage to cultural relics, it is necessary to identify the key factors influencing the damage and determine their respective weights. This paper combines the collection of cultural relics seismic damage data to construct a mapping of impact factors. It employs a graph attention mechanism to analyze the factor weights and quantify the influence of different factors on the seismic damage to cultural relics.

3.2.1. Ontology Layer Design for Cultural Relics Seismic Knowledge Graphs

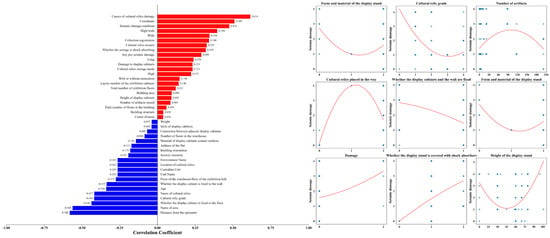

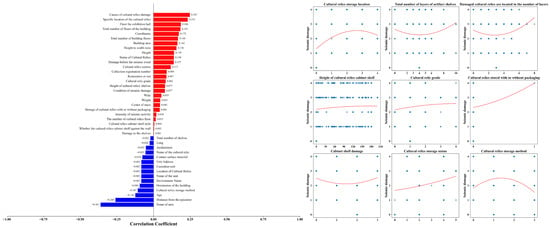

To systematically identify and analyze the potential impact factors on cultural relics during seismic events, and to better assess the risk, formulate protection measures, and optimize the seismic program before and after seismic events, it is essential to identify the factors that have a significant impact on the state of cultural relics during seismic events. However, due to the numerous attributes influencing the seismic damage of cultural relics, a preliminary correlation analysis of the attributes in the seismic damage dataset is first conducted to minimize the interference of irrelevant factors. Figure 5 presents the correlation analysis of each parameter in the exhibition hall with the damage to cultural relics, including the correlation coefficients between each parameter and the damage, as well as the relationship analysis between the exhibition hall damage and certain features.

Figure 5.

Correlation analysis between exhibition hall parameters and the Seismic Damage Level. The bar chart (left) ranks factors based on their Pearson correlation coefficients with the damage severity. The scatter plots (right) visualize the relationships between specific independent variables and the dependent variable (Damage Status, graded 0–5).

Figure 6 provides the correlation analysis of each parameter with the damage to cultural relics in the warehouse, including the correlation coefficients between each parameter and the warehouse damage, as well as the relationship between the damage and certain characteristics of the warehouse. It is important to interpret the observed correlations within the context of the physical mechanism. The variable ‘Causes of cultural relics damage’ refers to the specific failure mechanism (tipping, collision, or displacement) rather than the severity of the damage itself, which explains the nonlinear relationship observed in the scatter plots. Furthermore, certain attributes such as ‘Name of Area’ exhibit high correlations with damage levels because they function as spatial proxies. These variables implicitly encode critical geospatial information, including the distance from the epicenter, local site conditions, and regional seismic intensity, thereby serving as effective indicators of risk in the absence of direct seismic measurements.

Figure 6.

Correlation analysis between storehouse parameters and the Seismic Damage Level. The bar chart (left) displays the Pearson correlation coefficients, indicating the strength of the linear relationship between each factor and the damage outcome. The scatter plots (right) detail the distribution of damage levels across key attributes, such as ‘Distance from epicenter’ (numerical) and ‘Building structure’ (categorical/encoded), illustrating how specific storage conditions correlate with higher seismic risks.

Based on the correlation analysis presented in Figure 5 and Figure 6, the influencing factors were categorized to guide the ontology design. Factors such as ‘Seismic intensity’, ‘Distance from the epicenter’, and ‘Cultural relics texture’ exhibited strong correlations with damage severity, identifying them as direct physical drivers of seismic impact. Conversely, attributes like ‘Name of area’ and ‘Unit Address’ serve as contextual proxies, implicitly capturing regional seismic hazard characteristics. These insights directly informed the ontology layer design (Table 2) by prioritizing high-correlation attributes as primary nodes. Furthermore, this distinction established the initial feature focus for the Graph Attention Network, ensuring that the model assigns higher attention weights to physically significant drivers during the risk assessment process.

Table 2.

Ontology layer design for seismic damage knowledge graph for cultural relics in collections.

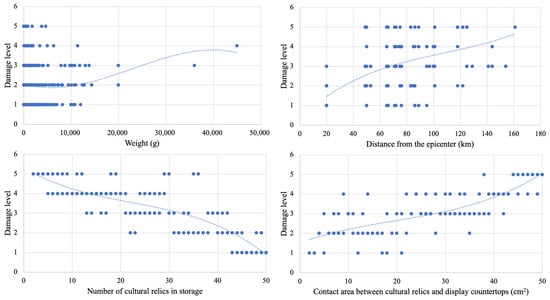

Figure 7 presents scatter plots of attributes and damage status of cultural relics from selected datasets. Based on the third-order polynomial fitting trend line of the cultural relics attribute data, a correlation is observed between the quality attribute and the seismic damage to cultural relics, although this correlation decreases as the quality increases. The distance from the epicenter is highly correlated with the damage level, with cultural relics closer to the epicenter experiencing higher levels of damage. The number of stored cultural relics and the contact area have similar effects on the damage level, with both trend lines remaining relatively flat.

Figure 7.

Correlation analysis of cultural relics’ seismic damage dataset attributes and damage levels.

Based on the correlation analysis, which initially screened the attributes that significantly impact the damage status of cultural relics, we integrated the latest whole-system seismic design concepts to develop an ontology layer. This layer includes multilevel category indexes from the seismic impact dataset of the cultural relics collection, which is used to construct the cultural relics seismic impact factor mapping. The structure of the ontology layer for the cultural relic seismic impact knowledge map is shown in Table 2. Considering the structural damage already accumulated in the historical environment of the artifacts themselves, the seismic with and without damage attributes are defined in the artifact body layer, which essentially reflects the cumulative results of fatigue damage under microseismic-like or cyclic loading.

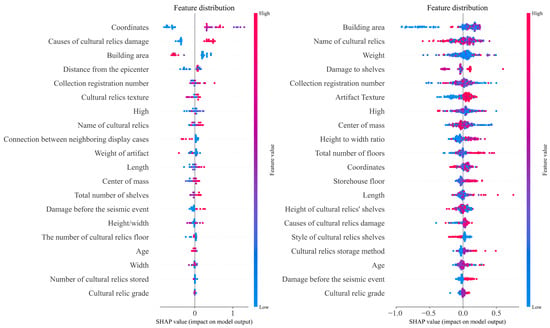

In this paper, the SHAP algorithm is used to analyze the seismic impact features of cultural relics in the collection. A SHAP value is assigned to each feature in the dataset, indicating both its positive and negative impacts. The average of the absolute SHAP values of each feature is considered its importance, and the correlation between these features and the damage to cultural relics is analyzed. Figure 8 presents the SHAP values of certain features in the exhibition hall and the storage room, respectively, in relation to the damage to the cultural relics. This provides a more intuitive understanding of the ontology layer analysis of the seismic damage knowledge map of the cultural relics in the collection. The figure shows that for features such as cultural relics texture, center of mass, cabinet shelf style, unit address, and shelf height, the SHAP values increase as the feature values increase.

Figure 8.

SHAP analysis of seismic impact characteristics of cultural relics in the collection (left: exhibition hall, right: storage room).

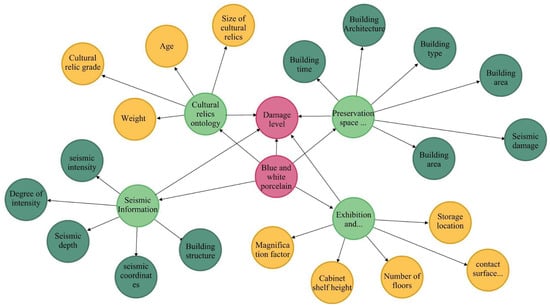

Additionally, the SHAP analysis highlights ‘Cultural relic grade’ as a contributing feature, where its value distribution correlates with the model’s output, indicating that artifacts of higher historical hierarchy are weighted differently in the damage prediction process due to their inherent preservation priority. Finally, based on the structured seismic impact data of the cultural relics in the collection, this paper combines top-down and bottom-up approaches to construct the seismic impact factor mapping for the collection. The ontology layer design architecture is shown in Figure 9. Within this architecture, ‘Cultural relic grade’ is explicitly mapped as a core attribute, ensuring that the assessment framework prioritizes high-value artifacts during the semantic reasoning process of seismic impact factors.

Figure 9.

Ontology layer architecture of seismic impact factors for cultural relics in the collection (partially displayed).

3.2.2. Seismic Impact Analysis Based on Graph Attention

This paper follows the ontology layer design to construct the knowledge graph of seismic-damaged cultural relics and employs a graph attention network to iteratively propagate information between cultural relic attribute nodes and edges based on the structure of the graph database. The attention coefficients of node features and edges capture the complex dependency relationships between factors, enabling the assessment of each factor’s impact on the seismic damage to cultural relics. The impact analysis process of the cultural relics seismic damage graph is illustrated in Figure 10, outlining the following steps.

Figure 10.

Calculation process of impact factor weights for cultural relics’ seismic damage graph.

Step 1: Construct the knowledge map of cultural relics seismic damage. Normalization is performed before constructing the knowledge map to ensure consistent data ranges, as shown in Equation (10).

The nodes and edges of the cultural relics seismic knowledge graph are thus defined. The vector of nodes, characterized by factor values, is denoted as . Here, represents the initial eigenvector of node i, and denotes the eigenvalue of factor i in dimension n. The weights for the edges are initialized to 1 and are subsequently updated through iterations.

Step 2: Graph Attention Network Construction. In the heritage seismic knowledge graph, each node updates its features by interacting with the features of its neighboring nodes. Attention weights are calculated using Equation (11).

Here, and denote the feature vectors of the nodes, and W is the trainable weight matrix used to transform the features. represents the trainable vector used to compute the attention coefficient. represents the set of neighbors of node i. Based on the attention weights , the node features are updated by weighted summation, as shown in Equation (12). is the activation function.

Step 3: Loss and Influence Weight Evaluation. The graph attention mechanism updates the node and relation weights based on the graph topology and selects the cross-entropy loss function for model training, as shown in Equation (13).

Here, represents the actual level of damage to the cultural relics, represents the predicted damage, N denotes the total number of cultural relics, and C denotes the damage level category. The relative correlation between the factors is assessed using the attention weights on the edges of the graph. A higher attention weight indicates a greater influence of node i on node j. This allows for the determination of the degree of influence of various factors on the damage to cultural relics, providing guidance for preventive protection against seismic, and facilitating the adjustment of protection strategies.

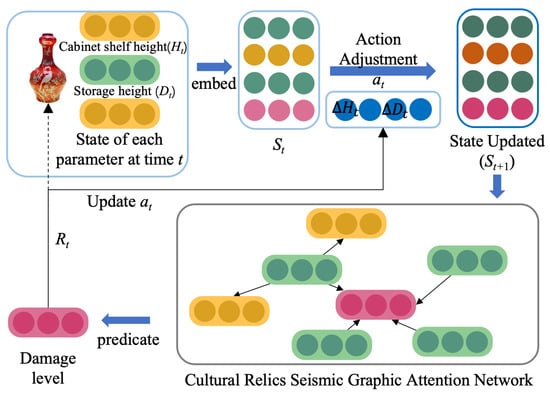

3.3. Cultural Relics’ Seismic Impact Factor Analysis by Fusion Graph Attention

By evaluating the factors affecting the seismic damage of cultural relics, a more intuitive analysis of the protection status of cultural relics under various environmental conditions can be performed, guiding the further enhancement of cultural relics protection. This is also the ultimate goal of preventive protection against seismic damage. However, due to objective factors, some conditions affecting seismic damage, such as the material and center of gravity of the cultural relics, have a significant impact on the damage level during a seismic event, but these factors cannot be adjusted or changed. Therefore, this paper employs reinforcement learning to adjust the conditions of the collection facilities, optimizing the environmental parameters for the preservation of cultural relics. This method simulates the pattern of changes in the damage state of cultural relics during seismic events and provides the optimal parameter adjustment plan, significantly reducing the risk of damage and ensuring the safety of the cultural relics. The specific process is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Cultural relics’ seismic impact risk assessment by fusing deep reinforcement learning.

3.3.1. Reinforcement Learning Problem Modeling

In the process of optimizing the preservation environment of cultural relics based on reinforcement learning, the goal is to minimize the risk of damage to cultural relics during a seismic event by adjusting the variable collection parameters (such as friction coefficients of contact surfaces, display case height, etc.). To achieve this goal, this study models the problem as a reinforcement learning problem, using a trained graph neural network with weight factors to predict the damage level of cultural relics, and combining the reinforcement learning algorithm to optimize the adjustment of environmental parameters. The following sections detail the modeling of the problem and the definition of the reinforcement learning environment from four aspects: state space, action space, reward function, and reinforcement learning environment design.

First, the state space of reinforcement learning is defined as the set of feature parameters that describe the current preservation environment of cultural relics. Each feature corresponds to a factor that influences the preservation conditions, thus characterizing the state of the environment. For example, adjustable continuous variables include the height of the display platform where the cultural relics are stored (D), measured in meters, with a value range of , and the height of the cultural relics cabinet shelf, which ranges from . The discrete variables are the styles of heritage cabinet shelves, which include four modes: shelves without guardrails, cabinets, display cabinets against the wall, and stand-alone display cabinets. These are encoded as , respectively. Specifically, refer to Exhibit 1. Each state can be represented by a multi-dimensional vector, , where t denotes the current time step, and the dimension of the state space is determined by the number of factors involved.

Second, the action space for tunable parameters is defined, where each action corresponds to adjusting a specific characteristic factor in the state. The actions can be either discrete or continuous, depending on the flexibility of the operation. In this study, a continuous action space is employed, with each action represented as . Here, and represent the adjustments made to the respective parameters. Each action is constrained by physical and practical conditions, with the adjustment limited to no more than 20% of the original value. After the action is executed, the state is updated, ensuring that the adjusted value remains within a reasonable range. This transition is governed by the reinforcement learning agent, as shown in Equation (14).

Finally, reward and penalty functions are defined to evaluate the optimization effect of the reinforcement learning agent on the damage risk. To align the problem with the objective of minimizing cultural relics damage, the reward function is defined as the negative value of the damage level, as shown in Equation (15).

Here, represents the predicted damage grade of cultural relics, calculated by the attention neural network of the seismic damage map based on the current preservation conditions. The values typically range from positive (e.g., 1 for slight damage and 6 for severe damage). When the adjusted damage level decreases, the reward function value increases, motivating the agent to learn better adjustment strategies. Conversely, if the adjusted damage level increases, the reward function value decreases, penalizing ineffective or harmful actions. By maximizing cumulative rewards, the reinforcement learning model can gradually learn how to optimize the preservation environment for the cultural relics.

3.3.2. Strategy Optimization and Risk Assessment

This study aims to optimize the parameters of the collection environment using reinforcement learning to minimize the damage risk to cultural relics. To achieve this, the Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) algorithm is chosen. This algorithm adjusts environmental parameters to train the policy network, generating optimal conditions that reduce the risk of seismic-induced damage to cultural relics.

The reinforcement learning network is a parameterized neural network, where the input is the current state of the environment , and the output is the adjustment of environmental parameters . This output adjustment directly modifies the parameters of the collection environment, thereby updating the conservation status of the cultural relics. The objective of the reinforcement learning network is to learn an optimal environmental adjustment strategy that minimizes the damage level by maximizing the reward function. Therefore, the objective function is defined in Equation (16).

The action value function estimates the cumulative reward over T time steps, starting from state and after executing the action , as shown in Equation (17).

To optimize the policy network, the gradient of the action with respect to the value function is computed by the value network. Then, the gradient of the current state with respect to the policy parameters is calculated to update the network parameters . According to the basic principle of policy gradients, the gradient is defined as shown in Equation (18).

Here, represents the sensitivity of the value network to the action , and reflects the response of the policy network to the input state. The reinforcement learning network learns the optimal parameter adjustment strategy through gradient updates and, by interacting and updating repeatedly, is able to analyze various collection conditions. This allows it to generate the most suitable adjustment strategy for the current state, minimizing the risk of cultural relics’ seismic damage after each adjustment.

3.4. Remarks

We introduced a novel closed-loop framework for seismic damage risk assessment and prevention. The primary novelties and research opportunities are threefold.

- Bridging the ‘Reality Gap’ in data. We propose a deep integrated learning-based data correction model. Unlike traditional methods that rely solely on sparse historical records, this approach validates the use of abundant laboratory simulation data by mathematically correcting the domain shift between replica experiments and authentic artifacts.

- Interpretable causal analysis. Moving beyond ‘black-box’ predictions, we utilize a Graph Attention Network (GAT) to construct a semantic knowledge graph. This mechanism explicitly quantifies the influence weights of complex factors, providing interpretable insights into the physical drivers of seismic damage.

- From assessment to active optimization. Distinct from existing studies that stop at risk estimation, this research employs deep reinforcement learning (DDPG) to actively formulate protection strategies. By dynamically optimizing environmental parameters, the method offers a transition from passive vulnerability assessment to active, automated preventive conservation.

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Experimental Environment and Dataset

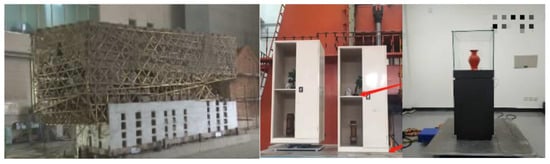

The experiment environment is divided into two main components: physical platform simulation experiments and model training based on deep learning. In the construction of the physical platform, three experimental setups are used to collect seismic data of cultural relics: the building level, floor level, and display cabinet level, as shown in Figure 12. Imitation cultural relics are placed in these experimental platforms to measure relevant seismic data, which are then used to supplement and correct the actual seismic data of the cultural relics, improving the overall dataset.

Figure 12.

Physical simulation experiment platform.

In addition to the deep learning-based experimental environment, the heritage seismic impact dataset was divided into training, validation, and test sets with a ratio of 7:2:1. The Adam optimizer was used for gradient updates during training. Model training was conducted over 100 iterations, with the initial learning rate set to 0.001, reduced by a factor of 0.1 after every 50 iterations, and a batch size of 8. To prevent overfitting, the L2 regularization method was applied. The reinforcement learning part was trained 100 times and explored 20 times. The experimental environment was implemented using the deep learning framework PyTorch and accelerated with CUDA 13.1.

To better evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method, three experimental datasets were selected for comparison in addition to the Seismic Damage Dataset of Cultural Relics (CR-SDD). These include House Prices [46], Concrete Compressive Strength [47], and Energy Efficiency [48]. Although these public datasets differ in domain from cultural heritage, they were selected to rigorously validate the mathematical robustness of the proposed correction method. The data correction task is fundamentally a regression problem requiring the model to learn complex, nonlinear mappings between high-dimensional attributes and continuous target variables, a structural characteristic shared by the CR-SDD, House Prices, Concrete Compressive Strength, and Energy Efficiency datasets. Testing on these established benchmarks allows for a standardized comparison against other state-of-the-art algorithms, ensuring that the model’s high performance on the heritage dataset is attributable to its superior feature extraction and generalization capabilities rather than dataset-specific overfitting.

- The CR-SDD dataset contains data on artifacts in the collections of 56 museums in a province in southern China. It contains basic attribute information such as images, quality and size of the front, side, and bottom surfaces of 1352 cultural relics, as well as information on the seismic damage of the relics through statistics. In addition to the actual artifact data, the records include 35 distinct replicas, each subjected to 10 different earthquake intensities.

- The House Prices dataset is a publicly available dataset used for house price prediction. It contains 79 explanatory variables that describe various aspects of homes in Ames, Iowa, and aims to predict the final price of each home based on these attributes, predicting a single price output.

- The Concrete Compressive Strength dataset is used to predict the compressive strength of concrete. It contains 1030 examples, each with 9 attributes: 8 quantitative inputs and 1 quantitative output.

- The Energy Efficiency dataset is used to evaluate the heating load and cooling load requirements of buildings based on their parameters. It contains 768 samples with 8 features and is designed to predict 2 outputs from the features of each sample.

In order to measure the error between the predicted value and the true value , this paper uses the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) as evaluation metrics. These metrics measure the average absolute error between the predicted and true values. The calculation processes are shown in Equations (19) and (20).

Since the prediction of the damage level of cultural relics due to seismic damage is based on existing data for classification, this paper uses precision (P), recall (R), and the F1 score (F1) of each level as performance evaluation metrics for the model’s damage level prediction. The calculation processes are shown in Equations (21)–(23).

where denotes samples where the damage level was correctly predicted, denotes samples that were incorrectly predicted as positive when they should have been negative, and denotes samples that were incorrectly predicted as negative when they should have been positive.

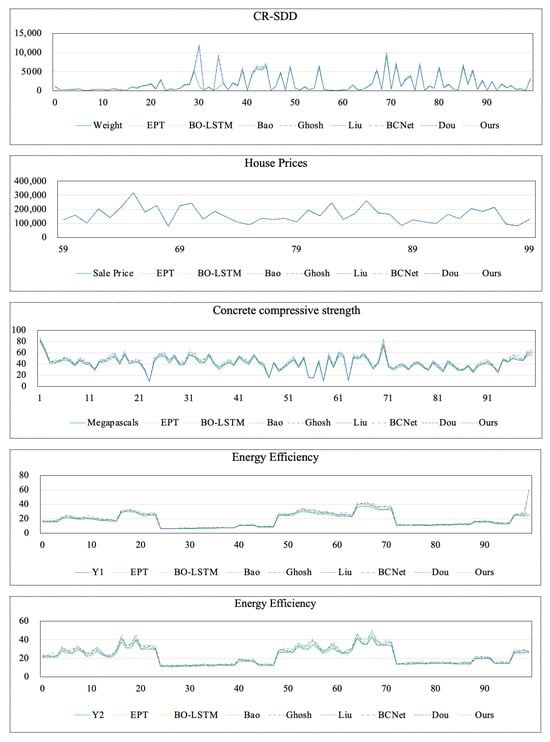

4.2. Correction Results of Cultural Relics Seismic Data

The integrated learning-based data correction method for replica cultural relics predicts the actual values of the cultural relics using the measured data from cultural relics replicas in the physical simulation platform. As shown in Table 3, the average evaluation results predicted by each model across four datasets are presented. It is important to note that for the cultural relics Seismic Impact dataset, the RMSE and MAE are averaged after predicting all types of simulation data. For the Energy Efficiency dataset, two output values are evaluated, while for the remaining two datasets, only a single prediction is evaluated.

Table 3.

Corrected results of seismic damage data for cultural relics. The best value is bold.

From the experimental evaluation results, it is evident that the method proposed in this paper achieves the best data prediction results across all three datasets, with the minimum MAE indicating that the predictions are closer to the real data. Particularly on the heritage seismic impact dataset, the model’s prediction results are more stable compared to the other prediction methods for the two real datasets, as reflected by the smallest RMSE.

The predictions of multiple models on four datasets are shown in Figure 13, with the model prediction results for 100 sets of cultural relics quality selected for presentation from the CR-SDD dataset. From the trend of the line graphs, it is clear that the prediction results of all eight methods are closer to the real values, with the quality predictions particularly aligning well with the true values, demonstrating the effectiveness of the selected model in data correction. In areas where local oscillations are more significant, the method proposed in this paper exhibits smaller oscillations compared to other models, indicating superior data correction performance. For the House Price dataset, 40 datasets are selected for comparison, and the smaller fluctuations in the predicted values are less noticeable in the graphs due to the large values for comparison. On the Energy Efficiency dataset, the correction effect of each model shows a larger gap from the real values, which is attributed to the small sample size of this dataset, making it difficult to effectively train the model. Considering the performance across all four datasets, the method proposed in this paper effectively achieves data correction.

Figure 13.

Correction results of the various methods on the comparison dataset.

Beyond statistical accuracy, the corrected values are supported by strong physical and conservation-based justifications. Physically, the integrated learning model explicitly maps the systematic deviations caused by material discrepancies (the density difference between a plaster replica used in testing and a bronze original) to the authentic physical parameters recorded in the ’Real-world Data’ subset. From a conservation perspective, this ensures that the corrected attributes align with the typological standards of the specific historical period. Consequently, the subsequent seismic risk calculations (toppling or sliding thresholds) reflect the actual mechanical behavior of the cultural heritage objects rather than the biased dynamic responses of the lightweight replicas.

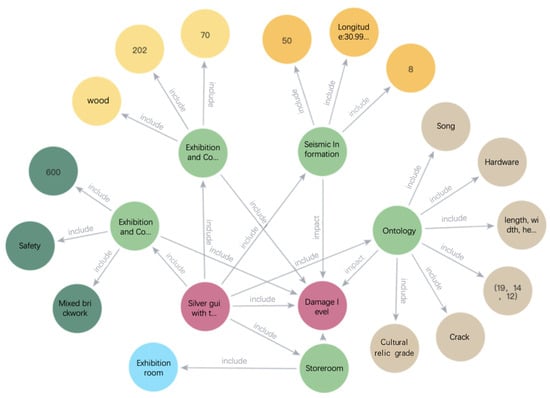

4.3. Seismic Factor Impact Weighting Assessment

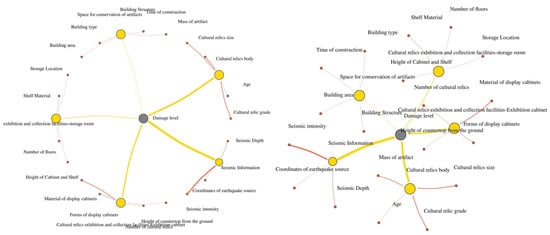

This paper constructs a knowledge graph for cultural relics seismic damage based on the ontology layer of the cultural relics seismic damage graph. Figure 14 shows a part of the graph visualization for specific cultural relics, where different nodes are connected through relationships, forming a graph structure that represents information about the seismic damage to cultural relics. As seen in the figure, different top-level influence factors have an impact on the damage to cultural relics, while bottom-level factors exert varying influence weights on the top-level factors. With the training of the graph attention mechanism network, a more stable influence structure can be obtained, which can be used to assess how the existing cultural relic collection environment influences the damage to the relics.

Figure 14.

Seismic damage knowledge graph to cultural relics.

To more intuitively demonstrate the influence of seismic damage factors on the damage level of cultural relics, this paper presents a weighted network diagram, as shown in Figure 15. In this diagram, circular nodes represent the factors, the connecting lines between them represent inclusion relationships, and the thickness of the connecting lines indicates the magnitude of the influence weights. From the distribution of weights, it is evident that, among the top-level factors (indicated by the yellow nodes), seismic information has the greatest influence on the damage level, while cultural relics exhibition and collection facilities—such as warehouses—have a smaller influence. Below each top-level node are the bottom-level factors (indicated by the red nodes). For example, under seismic information, seismic intensity shows the strongest correlation, with the connecting red line being the thickest, while the seismic source coordinates exhibit the smallest correlation. In parallel, the ’Cultural relic grade’ node exhibits a distinct connection weight, verifying that the model effectively accounts for the artifact’s hierarchical importance when aggregating potential damage risks. This network diagram provides a clearer understanding of the impact of different seismic factors on the preservation of cultural relics, helping to guide subsequent adjustments to the collection conditions for better protection.

Figure 15.

Impact factor weight distribution network map (partial).

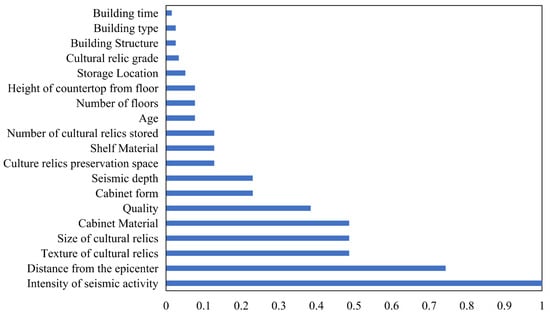

In this paper, 18 of the most highly ranked influences are selected, and their values are normalized and displayed. As shown in Figure 16, the graph represents the ascending order of importance of the feature attributes. Based on the analysis of the influence weights of these attributes, it can be seen that seismic intensity is the most important factor affecting the energy consumption of residential heating, followed by the distance from the epicenter and the texture of the cultural relics. It is crucial to interpret these weight distributions within the context of preventive conservation. Although the main building structure may not sustain severe damage during a seismic event, the internal collections may still face catastrophic risks due to micro-vibrations, tipping, or displacement. Consequently, the protection strategy must be refined: the risk thresholds for artifacts with high cultural relic grade should be set significantly lower than those for the building structure. This hierarchical approach ensures that even minor environmental fluctuations trigger proactive protective measures for the most valuable assets.

Figure 16.

Importance ranking of cultural relics’ seismic impact factors.

4.4. Risk Assessment of Cultural Relics’ Seismic Impacts

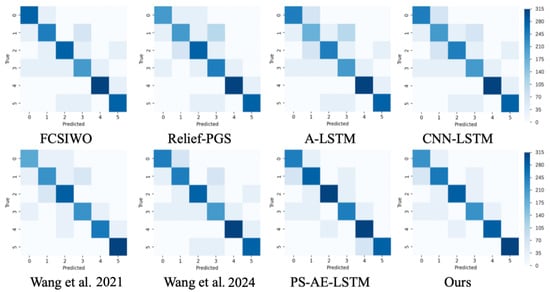

In this paper, we evaluate the attention network of the cultural relics seismic damage map based on the environmental parameters of the cultural relic collection to assess the model’s effectiveness in predicting the damage level of cultural relics during seismic events. As shown in Table 4, the results of damage level assessment from various methods on the cultural relics seismic damage dataset are presented. Among these methods, the approach proposed in this paper demonstrates the best performance in predicting the damage level, with an accuracy rate of up to 81.21%, effectively enabling the assessment of the seismic damage status of cultural relics.

Table 4.

Risk assessment results of various models on the cultural relics’ seismic damage dataset. The best value is bold.

As shown in Figure 17, the confusion matrix of the seismic damage prediction results of multiple models based on the attribute information of cultural relics is presented. The horizontal axis represents the predicted damage level, and the vertical axis represents the actual damage level, where the darker the diagonal line, the more correctly predicted the damage level of the cultural relics. From the experimental results, it can be seen that each model can generally achieve the correct prediction of the damage level of cultural relics, but there is confusion for relics with similar damage conditions, especially for the two cases of fracture and crack corresponding to categories 2 and 3. Due to their similar preservation environment and pre-damage state, methods such as Relief-PGS and A-LSTM exhibit misclassification. For predicting higher damage levels, methods like Wang et al. and PS-AE-LSTM show more accurate prediction results. Combining the prediction results of each category, the method proposed in this paper has the darkest diagonal color in the confusion matrix, indicating the best prediction performance for the damage grade of cultural relics.

Figure 17.

Confusion matrix for seismic damage prediction of cultural relics [57,58].

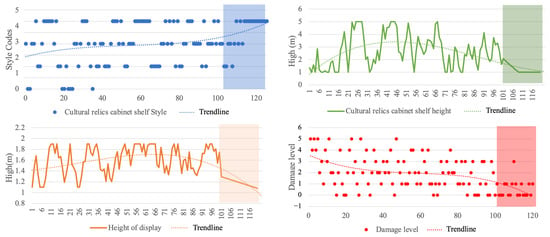

In order to better assess the impact of different factors on the seismic damage of cultural relics, this paper evaluates four adjustable parameters: the style of the cultural relics cabinet shelf, the height of the cultural relics cabinet shelf, the height of the display platform, and the damage level, for seismic damage risk assessment. The results of the cultural relics damage level assessment, after adjusting the parameters through reinforcement learning, are shown in Figure 18. The changes in the three parameters are significant in the early stages, indicating that the model is in the exploration phase. As the time steps increase, the fluctuation of the folding line gradually decreases and stabilizes. The last 20 steps show that the reinforcement learning model has selected better parameter values through the exploration process.

Figure 18.

Predicted results of seismic risk for cultural relics.

As observed from the results of the last 20 steps of the experiment, the model’s assessment of cultural relics damage level gradually decreased compared to the training stage and stabilized at levels 1 and 2. The importance ranking in Figure 18 aligns with established seismic vulnerability principles, where ‘Seismic intensity’ and ‘Texture’ (material fragility) are correctly identified as the dominant risk drivers. Furthermore, the reinforcement learning model’s specific recommendations, such as lowering the display height to reduce the center of gravity and prioritizing independent, stable cabinetry over wall-mounted fixtures, are fully consistent with current preventive conservation standards. These outputs confirm that the algorithm has successfully learned to optimize for physical stability, mirroring best practices in museum collection management. The style of the cultural relic shelves and cabinets tends to favor standalone display cabinets, while the height of the cultural relics cabinets and shelves is approximately 1 m, and the display table storage height is around 1.5 m. Therefore, in the given cultural relics storage environment, damage during a seismic event or other uncontrollable environmental factors can be minimized.

5. Conclusions

This paper addresses the challenge of incomplete datasets for the uncertainty analysis of cultural relics’ seismic damage and the risk assessment of their seismic damage. A novel method for seismic damage risk assessment is proposed, which combines deep learning and reinforcement strategies. The method includes a data correction model based on deep integrated learning, which adjusts the real cultural relics’ seismic damage attribute data using simulated data from replica cultural relics. Additionally, a knowledge graph of cultural relics’ seismic damage is constructed, allowing for the precise quantification of the influence of each attribute factor on the damage level of cultural relics using the graph attention mechanism. Finally, a reinforcement learning strategy is introduced to explore the impact of various attributes on the damage to cultural relics, providing targeted recommendations for the adjustment of the collection environment. The experimental results demonstrate that this approach can effectively assess the risk of seismic damage to cultural relics and offer valuable theoretical and technical support for their preventive protection against seismic events.

Despite the promising results, this study has several limitations that define the scope for future work. The current risk assessment framework is confined to isolated seismic impacts and does not yet account for coupled multi-hazard scenarios, such as fire or water leakage triggered by earthquakes. Additionally, due to the limited scope of the current seismic impact dataset on cultural relics, it is challenging to compare the data correction performance with other similar datasets. Future work will focus on expanding the existing dataset and incorporating additional relevant attributes of cultural relics to enhance the robustness and applicability of the proposed method. Future research will also focus on deepening multidisciplinary collaboration, integrating structural engineering data with heritage value assessments to develop more comprehensive, value-based loss probability models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.H. and Z.X.; methodology, L.H.; software, L.H.; validation, L.H., Z.X. and X.Y.; formal analysis, L.H.; investigation, Z.X.; resources, X.Y.; data curation, J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, L.H.; writing—review and editing, L.H.; visualization, L.H.; supervision, J.W., M.G. and W.W.; project administration, J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in House Prices [46], Concrete Compressive Strength [47], and Energy Efficiency [48].

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Full information for the cultural relic seismic knowledge graph.

Table A1.

Full information for the cultural relic seismic knowledge graph.

| First Level | Data Item (Second Level Classification) | Data Attribute | Attribute Range (Range/Unit) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preservation space for cultural relics | Name of the unit | Text, 56 unit names | (0, 1, 2, …, 55) |

| Building structure | Brick/brick/frame | (0, 1, 2) | |

| Building type | Museum Building/General Building | (0, 1) | |

| Building area | Numerical value | float | |

| Damage status | Collapsed/structurally damaged/severely damaged/slightly damaged/safe | (0, 1, 2, 3, 4) | |

| Total number of floors | Numerical value | int | |

| Type of storage location | Cultural relics storage/cultural relics exhibition hall | (0, 1) | |

| Store room floor/showroom floor | Numerical value | int | |

| Cultural relics ontology | Cultural relic grade | grade | int |

| Collection No. | Numeric | text | |

| Texture | Pottery/porcelain/metalware/masonry/organic matter | (0, 1, 2, 3, 4) | |

| Grade of cultural relics | Numerical value | int | |

| Age | In years | int | |

| Size | Length, width, height/caliber/diameter/bottom/belly diameter | float | |

| Weight | g | float | |

| Damage before the seismic event | Yes/No | (0, 1) | |

| Any restoration due to damage | Yes/No | (0, 1) | |

| Reason for damage to cultural relics | Damage due to the display cabinets (cabinets of cultural relics), shelves tipped over/due to cultural relics falling/tipped over/due to mutual collision damage/due to the collapse of the building damage/due to the display cabinets in the appendages (eg, lighting equipment, warning equipment, etc.) fall damage | (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) | |

| Destruction of cultural cultural relics | Radioactive damage/partial damage/fracture/crack/deformation/scratch/scratch | (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) | |

| Exhibition and storage facilities—storage room | Cultural relics storage location | Cultural relics shelves/cultural relics cabinet/ground | (0, 1, 2) |

| Cultural relics cabinet shelf material | Metal/wood/cement/others | (0, 1, 2, 3) | |

| Cultural relics cabinet shelf style | Shelf/cabinet without guardrail/cabinet against the wall/stand-alone display cabinet | (0, 1, 2, 3) | |

| The state of the door of the shelf of cultural relics at the time of earthquake | Flap door closed, but not secured, movable/Flap door closed and locked/Null value | (0, 1, 2) | |

| Total number of layers of artifact shelves | Numerical | int | |

| Damaged cultural relics are located in the number of layers | Numerical value | int | |

| Height of cultural relics cabinet shelf | Unit “cm” | float | |

| The form of the foot of the shelf of cultural relics | Flat foot | / | |

| Whether the cultural relics cabinet shelf against the wall | Yes/No | (0, 1) | |

| Cultural relics cabinet shelf between the fixed way | Yes/No | (0, 1) | |

| Cultural relics cabinet shelf and the ground fixed way | Yes/No | (0, 1) | |

| Whether there is a shock absorber on the countertop of the shelf of cultural relics | Yes/No | (0, 1) | |

| Damage | Overturned/undamaged/displaced/others | (0, 1, 2, 3) | |

| Cultural relics storage status | Vertical/Flat/Covered/Horizontal/Suspended/Other | (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) | |

| Cultural relics storage method | Hybrid/Freestanding/Compact/Other | (0, 1, 2, 3) | |

| Cultural relics stored with or without packaging | Yes/No | (0, 1) | |

| Cabinet shelf damage | Tipped over/undamaged/displaced/others | (0, 1, 2, 3) | |

| Contact surface material | Wooden/Fabric/Plexiglass/Other | (0, 1, 2, 3) | |

| Exhibition facilities—exhibition halls | Display case material | Wood/Plexiglass/Others | (0, 1, 2) |

| Form of exhibition cabinet | Against the wall display cabinets/stand-alone display cabinets | (0, 1) | |

| Number of artifacts | Numerical | int | |

| Height of countertop from the ground | Numerical | float | |

| Whether the display case and the building floor are fixed | Yes/No | (0, 1) | |

| Whether the display cabinets and the wall are fixed | Yes/No | (0, 1) | |

| Whether there are adjacent display cabinets | Yes/No | (0, 1) | |

| Whether there is any connection between the neighboring display cabinets | Yes/No | (0, 1) | |

| Damage | Undamaged/displaced | (0, 1) | |

| Other anti-vibration measures for display cases | Yes/No | (0, 1) | |

| Damage to ancillary equipment in the display cases | Intact/loose and not falling | (0, 1) | |

| Whether there is a special display stand in the display case | Yes/No | (0, 1) | |

| Whether the display stand is covered with shock absorbers | Cloth/Nothing/Other | (0, 1, 2) | |

| Height of the display stand | Numerical | float | |

| Form and material of the display stand | Wood/Plexiglass/Other | (0, 1, 2) | |

| The way of fixing the display table and the countertop of the exhibition cabinet | No fixing/welding/others | (0, 1,2) | |

| Cultural relics placed in the way | Flat/vertical/suspended | (0, 1, 2) | |

| Artifacts and display surface contact area | Numerical | float | |

| Fixed anti-vibration measures of cultural relics | No/Internal support method/Bolted wire method/Other | (0, 1, 2, 3) | |

| Seismic Information | Custodian unit | 56 Unit Names | (0, 1, 2, …, 55) |

| Address | Text | / | |

| Moment of the earthquake | Year/Month/Day Hour: Minute: Second | time | |

| Intensity of earthquake | Numeric value | float | |

| Magnitude | Numeric value, harmonized | float | |

| Seismic depth | Unit “km” | float | |

| Coordinates of earthquake source | Unit “degree-minute” | posion | |

| Distance to epicenter | Unit “km” | float | |

| Geological conditions | Complex/medium/simple | (0, 1, 2) |

References

- Damiani, A.; Poggi, V.; Scaini, C.; Kohrangi, M.; Bazzurro, P. Impact of the Uncertainty in the Parameters of the Earthquake Occurrence Model on Loss Estimates of Urban Building Portfolios. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2023, 95, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M.D.; Shumway, A.M.; Powers, P.M.; Field, E.H.; Moschetti, M.P.; Jaiswal, K.S.; Milner, K.R.; Rezaeian, S.; Frankel, A.D.; Llenos, A.L.; et al. The 2023 US 50-State National Seismic Hazard Model: Overview and Implications. Earthq. Spectra 2023, 40, 5–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z. Temporal, Spatial Distribution Characteristics, and Influencing Factors of National Key Cultural Relics Protection Units in the Yangtze River Delta. Sage Open 2024, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Aoki, N.; Wang, R.; Xu, S. Development of Cultural Heritage Conservation Planning in China. Plan. Perspect. 2024, 39, 925–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Song, D.; Geng, G.; Zhou, M.; Liu, J.; Li, K.; Cao, X. CPDC-MFNet: Conditional Point Diffusion Completion Network with Muti-Scale Feedback Refine for 3D Terracotta Warriors. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Chen, J.; Cui, X. Reinforced Protection of Fragile Bronze Cultural Relics Based on Nano-Cuprammonium Fiber Material. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zhu, J. Application of Epoxy Resin in Cultural Relics Protection. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 35, 109194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Palacios, S.M.; Meslem, A. Development of a New Tool for Seismic Risk Assessment and Multi-Criteria Decision Making. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 106, 104261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xie, Q.; Zhu, W. Rapid Assessment of Substation Earthquake Risk Based on Minimal Cut Sets. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 229, 110175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, J.; Zhang, T. A Relief-PGS Algorithm for Feature Selection and Data Classification. Intell. Data Anal. 2023, 27, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Chen, F.; Fu, B.; Chen, W.; Qiao, Y.; Shi, P.; Zhou, W.; Lin, H.; Liao, Y.; Gao, S. Earthquake-Induced Risk Assessment of Cultural Heritage Based on InSAR and Seismic Intensity: A Case Study of Zhalang Temple Affected by the 2021 Mw 7.4 Maduo (China) Earthquake. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 84, 103482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.; Fan, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Qi, Y.; Liu, M. Fine-Scale Spatiotemporal Earthquake Casualty Risk Assessment Considering Building Function Types. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 112, 104806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ben, S.; Liu, C.; Li, X.; Meng, Q.; Hao, Y.; Jiao, Q.; Yang, P. Web-Based Diagnostic Platform for Microorganism-Induced Deterioration on Paper-Based Cultural Relics with Iterative Training from Human Feedback. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Chen, D. Research on the Classification of Ancient Silicate Glass Artifacts Based on Machine Learning. Archaeometry 2024, 67, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, P.; Geng, G.; An, L.; Zhou, M. Enhancing Point Cloud Registration with Transformer: Cultural Heritage Protection of the Terracotta Warriors. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Wei, Q.; Gong, M.; Yang, X.; Wei, J. Transfer Learning-Based Center-of-Mass Positioning Methods for Cultural Relics. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 7911–7926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Huang, X.; Xia, G.; Liu, X.; Ma, X. A High-Precision Automatic Extraction Method for Shedding Diseases of Painted Cultural Relics Based on Three-Dimensional Fine Color Model. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Huang, H.; Xiao, N.; Yu, J.; Geng, G. A Point Cloud Segmentation Algorithm Based on Multi-Feature Training and Weighted Random Forest. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 36, 015407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Tao, N.; Omer, A.M.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, D.; Zhang, H.; Fang, Q.; et al. Attention-Enhanced U-net for Automatic Crack Detection in Ancient Murals Using Optical Pulsed Thermography. J. Cult. Herit. 2024, 70, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Shao, Y.; Lian, Y.; Li, P.; Lei, Q. Bayesian Optimization-Based LSTM for Short-Term Heating Load Forecasting. Energies 2023, 16, 6234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, N.; Wankhade, S. Fractional Cuckoo Search Invasive Weed Optimized Neural Network for Data Classification. Concurr.-Comput.-Pract. Exp. 2023, 36, e7948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]