Abstract

Underwater wireless sensor networks (UWSNs) are increasingly used in marine monitoring and naval coastal surveillance, where limited bandwidth, long propagation delays, and physically exposed nodes make efficient authentication critical. This paper analyzes the maritime-surveillance-oriented protocol of Jain and Hussain and identifies vulnerabilities to physical capture, replay, and denial-of-service (DoS) attacks. We propose a PUF-assisted mutual authentication and session key agreement protocol for UWSNs. The design relies on lightweight symmetric primitives (one-way hash and XOR) and uses a fuzzy extractor to support stable PUF-based key material. In addition, a lightweight continuous authentication procedure is introduced to facilitate fast re-authentication under intermittent link disruptions commonly observed in underwater communication. Security is evaluated using BAN logic, the Real-or-Random (ROR) model, and security verification with the Scyther tool. An analytical overhead evaluation reports a computational cost of 5.972 ms per mutual authentication and a 1152-bit communication overhead, supporting a practical security–efficiency trade-off for resource-constrained UWSN deployments.

1. Introduction

As wireless sensor networks (WSNs) became widely adopted in terrestrial environments, similar concepts were extended to marine environments, leading to the development of underwater wireless sensor networks (UWSNs). Compared to land-based networks, UWSNs face unique challenges due to the physical properties of water, including high attenuation, limited bandwidth, long propagation delay, and frequent link disruptions. To satisfy complex monitoring requirements, UWSNs typically integrate heterogeneous nodes that can be categorized into static nodes, semi-mobile nodes, and mobile nodes [1,2]. Among them, mobile nodes are particularly suitable for coastal and maritime surveillance because they can autonomously traverse wide areas and collect data from diverse coastal points. Recent advances in unmanned technologies, battery lifetime, and underwater communication systems have further improved the operational efficiency and reliability of mobile nodes, enabling sustained monitoring in rapidly changing coastal environments [3].

The design and communication technologies for UWSNs in naval coastal surveillance have continuously evolved [4]. However, many studies have focused primarily on network architectures and deployment frameworks, while security issues during underwater communication remain insufficiently addressed [5,6]. In underwater environments, sensor nodes exchange data over open channels, which makes confidentiality and integrity vulnerable to external threats—especially in sensitive scenarios such as naval surveillance, where security breaches may cause severe operational consequences. Moreover, underwater acoustic communication often suffers from high attenuation and short transmission ranges, which results in unstable links and frequent retransmissions. Therefore, practical UWSN security protocols must be not only secure but also lightweight for resource-constrained sensor nodes, and they should support fast re-authentication to accommodate intermittent link disruptions.

1.1. Related Work and Motivation

Recent authentication research for UWSNs and underwater IoT (IoUT) can be broadly categorized into lightweight designs and public-key-based designs, with additional works addressing routing efficiency and trust management. Islam and Taher [7] proposed a lightweight scheme to mitigate Sybil attacks using node identities and a hierarchical fuzzy trust system; however, their approach does not address several routing-related threats (e.g., blackhole and wormhole attacks) and may be less adaptable to highly dynamic environments. Almuhaideb and Al-Khulaifi [8] developed a mutual authentication protocol for IoUT using lightweight operations combined with elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) and reported resistance to attacks such as man-in-the-middle and replay attacks; nevertheless, ECC-based mechanisms may still impose non-trivial computational overhead and require additional scalability/performance evaluation for dynamic large-scale deployments. Kapileswar et al. [9] proposed an energy-efficient routing protocol for IoT-enabled UWSNs based on the bald eagle search (BES) optimization algorithm. The scheme aims to balance traffic and residual energy during route selection to improve network lifetime. The authors evaluated energy consumption, residual energy, packet delivery ratio, throughput, delay, and network lifetime, and reported improved performance compared with representative routing baselines.

Al Guqhaiman et al. [10] proposed a lightweight multi-factor authentication model for UWSNs to detect malicious activities and protect MAC/routing operations against common attacks (e.g., Sybil, blackhole, wormhole, flooding-related threats). Instead of heavy cryptography, their scheme authenticates packets using multiple header-level factors such as IMAC, AoA/DoA, and hop count, which are checked against locally stored neighbor information without requiring accurate time synchronization or precise localization. The approach supports monitoring and mitigation by dropping suspicious packets and isolating malicious nodes.

Kumar et al. [11] proposed SafeCom, a mutual authentication and dynamic session key sharing protocol for UWSNs, considering a practical architecture with sensor nodes, a sink, and a base station (with optional AUV-assisted forwarding). The authors validated security via informal analysis and simulation using the Scyther tool, and compared computational and communication overhead with representative schemes. However, SafeCom relies on a secure provisioning assumption during the registration stage and does not explicitly address surveillance-oriented requirements such as hardware cloning resistance under physical capture and fast re-authentication under intermittent underwater link disruptions, which motivate our work.

Khatwani and Roy [12] analyzed ECC-based authentication protocols and highlighted their susceptibility to clogging attacks, where an adversary can repeatedly trigger computationally expensive ECC operations (e.g., point multiplication) by sending forged or replayed requests, thereby exhausting a victim’s energy and processing resources. This observation implies that, despite strong cryptographic foundations, ECC-heavy designs can be operationally fragile in resource-constrained and intermittently connected UWSN settings, motivating lightweight primitives and early-request filtering for practical deployments.

Yang and Zou [13] proposed a device-to-device authentication protocol for IoT environments. They pointed out the limitations of secure channels in registration phase and proposed a protocol structure where the server distributes a public key but cannot reverse-compute the private key. In their protocol, they utilized ECC to support direct authentication among IoT devices and reduce the dependency on a central trusted authority.

Overall, existing protocols often provide either strong cryptographic security with relatively higher overhead (e.g., ECC-based approaches) or lightweight schemes that do not explicitly address both physical capture/cloning risks in physically exposed sensor nodes and the practical requirement of fast re-authentication under intermittent underwater connectivity. In 2021, Jain and Hussain proposed an authentication mechanism explicitly targeting maritime territory and frontier surveillance in underwater environments [14].

We selected this work as a baseline because it directly aligns with surveillance-oriented UWSN deployments and adopts a lightweight symmetric-key-based design that is suitable for resource-constrained sensor nodes. This operational context closely matches naval coastal surveillance considered in this paper, making a mission-relevant baseline for analysis and improvement. In addition, this protocol has been referenced by subsequent studies in the UWSN security literature, indicating that it serves as a representative starting point for further analysis and enhancement.

However, our analysis indicates that the protocol in [14] remains vulnerable to replay attacks, physical cloning attacks, and denial-of-service (DoS) attacks, and it does not fully achieve mutual authentication. Moreover, it does not sufficiently reflect the practical requirement of fast re-authentication under intermittently connected underwater acoustic links. These limitations motivate the design goals of our work. Accordingly, we use [14] as a practically aligned baseline for systematic vulnerability analysis and protocol-level improvement, while comparing our scheme with representative alternatives in Section 6.

To address the above gap, this paper proposes a secure and lightweight mutual authentication and session key agreement protocol for UWSNs in naval coastal surveillance. The key contributions of this work are as follows:

- We employ one-way hash functions and XOR operations to reduce computational and communication overhead on resource-constrained sensor nodes.

- We incorporate a physically unclonable function (PUF) to bind node identity to hardware and mitigate cloning risks under physical capture, using a fuzzy extractor to support stable PUF-derived cryptographic material. In particular, we integrate a PUF-based device to achieve the end-to-end lightweight authentication and key agreement workflow for preventing impersonation using a captured node’s stored data.

- A lightweight continuous authentication procedure is introduced to facilitate fast re-authentication under intermittent link disruptions common in underwater communication.

- Security is evaluated through informal analysis and formal methods, including BAN logic [15], the Real-or-Random (ROR) model [16], and security verification with the Scyther tool [17,18].

1.2. Organization

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the preliminaries, including the adversary model, PUF and fuzzy extractor background, and the system model. Section 3 reviews the baseline protocol of Jain and Hussain and analyzes its security vulnerabilities. Section 4 presents the proposed PUF-assisted mutual authentication and session key agreement protocol, including the continuous authentication procedure for intermittent underwater connectivity. Section 5 provides protocol-level security analysis using BAN logic, the Real-or-Random (ROR) model, and Scyther-based security verification. Section 6 evaluates performance in terms of security coverage as well as computational and communication overhead. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we introduce the adversary model, PUF, fuzzy extractor, and the proposed system model.

2.1. Adversary Model

To analyze the security of our proposed protocol, we modeled the adversary using the well-known Dolev–Yao (DY) model [19,20]. The capabilities of a malicious user, denoted as , can be defined as follows.

- can eavesdrop on, intercept, inject, replay, and modify messages transmitted over a public channel [19]. Based on these capabilities, is able to launch attacks such as MITM, replay, and impersonation.

- The adversary can compromise a legitimate sensor node and extract secret credentials stored in its memory by performing a power analysis attack. can steal the legal user’s mobile device or smart device and extract secret credentials stored in the memory by performing the power analysis attack [21].

Additionally, the sensor nodes operating underwater are military-grade and highly trusted, with minimal operational numbers to maintain stealth in underwater environments. We assume that legitimate sensor nodes are not designed to impersonate others under normal conditions, and such behavior is prohibited by strict security regulations. However, if a node is compromised by an adversary, impersonation becomes possible.

2.2. Physical Unclonable Function

Hardware has unique physical characteristics for each device even with the same design due to subtle process differences that occur during the manufacturing process. A PUF is a hardware structure to produce a device-specific output. Formally, for a given input (challenge) C, a PUF returns an output (response) R:

The pair is often referred to as a challenge–response pair (CRP). In practice, PUF responses may slightly vary across measurements due to temperature, voltage, aging, or measurement noise. Therefore, a PUF is commonly combined with a fuzzy extractor to reliably reproduce a stable private key from noisy responses without permanently storing sensitive keys in memory.

PUFs provide the following key properties in our threat model:

- Unclonability: For the same input C, no other circuit can generate exactly the same response .

- One-way Evaluability: The output R for the input C can be easily computed, but it should be computationally difficult to infer C or its internal structure in reverse through R.

- Unpredictability: PUF responses cannot be predicted externally in advance.

In particular, we integrate PUF-derived device binding into the end-to-end lightweight authentication and key agreement workflow so that a captured node’s stored data alone is insufficient for impersonation.

2.3. Fuzzy Extractor

This section explains the concept and operation of a fuzzy extractor [22]. Since physics-based inputs such as biometric information or PUF responses are vulnerable to environmental noise or measurement errors, it is difficult to obtain the same output. Fuzzy extractor is a technique designed to compensate for this uncertainty and reliably reproduce the same secret even when a certain level of noise exists. Let denote initial input of device , and let denote a later input in authentication phase. We assume that the deviation between and is bounded by a noise threshold t:

Note that represents the Hamming distance. From that, fuzzy extractor is useful for converting non-deterministic inputs such as PUFs or biometric information into stable secret parameters. Fuzzy extractor consists of two core algorithms:

- : It is a probabilistic algorithm that generates an initial secret. After receiving input , the smart device generates a secret string and a helper string .

- : It is a deterministic algorithm that reproduces the secret by compensating for the noise in input. When the smart device obtains , it compensates for the noise using the helper string and regenerates the original secret .

2.4. System Model

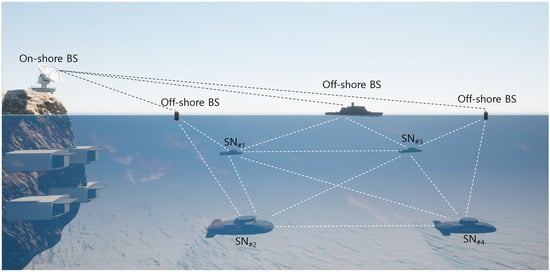

The proposed system model aims to secure communication in underwater wireless sensor networks through a lightweight and dynamic authentication protocol. As illustrated in Figure 1, the network architecture comprises multiple underwater sensor nodes () and base stations (). These entities work together to monitor the underwater environment and protect sensitive data during transmission. In this paper, we explicitly distinguish the physical/operational characteristics of underwater acoustic communication (e.g., high attenuation, limited bandwidth, long propagation delay, multipath, and intermittent connectivity) from the system and threat-model assumptions used for protocol design and verification. Our evaluation focuses on protocol-level security goals (mutual authentication and session key security) under the stated adversary model. Physical-layer channel effects such as bit errors caused by noise or multipath are assumed to be handled by standard lower-layer reliability mechanisms and are therefore outside the scope of the formal verification presented in this study. These aspects will be addressed in future implementation-oriented and empirical evaluations.

Figure 1.

System model for UWSN-based coastal surveillance.

- : The sensor nodes are deployed underwater to collect environmental and operational data. They communicate with neighboring nodes and base stations, ensuring secure data exchange through mutual authentication. Base stations serve as trusted entities that facilitate communication between sensor nodes and central monitoring systems. They also handle the initialization, authentication, and session key generation processes, which are critical for maintaining network security and reliability.

- : The are strategically deployed both on-shore (land-based) and off-shore (marine-based) to facilitate efficient communication and coordination between underwater sensor nodes and central monitoring systems.

3. Jain and Hussain’s Protocol and Vulnerability Analysis

This section reviews the authentication protocol proposed by Jain and Hussain [14], which is used as the baseline scheme in this study for surveillance-oriented UWSN deployments. The protocol is designed to establish secure communication between sensor nodes and the base station using lightweight symmetric primitives, and it mainly comprises a sensor node registration phase and an authentication phase.

For clarity, the notations used in the baseline protocol are summarized in Table 1. Based on this description, we then analyze the protocol’s security limitations and demonstrate its vulnerability to replay, physical capture/cloning, and denial-of-service (DoS) attacks, as well as incomplete mutual authentication.

Table 1.

Notation of Jain and Hussain’s protocol.

3.1. Review of Jain and Hussain’s Protocol

3.1.1. Initial Phase

During the initial phase, the generates and initializes global parameters required for authentication. Each sensor node is assigned a unique identifier (), a random value (), and a secret key (), which are securely stored for use in the registration and authentication phases.

3.1.2. Sensor Node Registration Phase

In the registration phase, the communicates with the over a secure channel. encrypts a request message using its secret key . The value is a hash computed as . The decrypts the message, verifies the and hash, and computes an intermediate value . It then generates an authentication credential and sends message to and message to .

Both nodes decrypt the messages, verify the timestamps, and store the credentials if verification is successful. Once the registration is complete, secure communication can proceed.

3.1.3. Authentication Phase

After registration, mutual authentication is performed over a public channel. Sensor node encrypts an authentication request using symmetric encryption and sends it to . Here, is a random number, and is a stored credential.

decrypts the message and verifies the random number and credential. If successful, responds with message . then verifies the response. Upon successful verification, mutual authentication is complete, and both nodes establish a session key for secure communication.

3.2. Cryptanalysis of Jain and Hussain’s Protocol

This section analyzes the vulnerabilities of Jain and Hussain’s protocol which is susceptible to various attacks, including physical and cloning, replay, and DoS attacks. Moreover, Jain and Hussain’s protocol cannot ensure mutual authentication. Details are as follows.

3.2.1. Physical and Cloning Attack

Sensor nodes deployed in UWSN environments are often located in physically unprotected environments, such as underwater regions where direct access control is difficult. As a result, these nodes are highly susceptible to physical capture by adversaries. Once a node is compromised, an attacker can extract sensitive credentials from its memory, including the node identity , the shared secret key , and session-related nonces .

Using the extracted set , the attacker can generate a clone node that imitates the original sensor node’s identity and cryptographic behavior.

A typical physical and cloning attack proceeds in the following stages:

- Step 1:

- Physical capture of the sensor node .

- Step 2:

- Extraction of authentication credentials from memory:

- Step 3:

- Deployment of a clone node and transmission of forged messages, such aswhere denotes symmetric encryption using the compromised key .

Due to the absence of freshness verification mechanisms such as timestamps or challenge–response structures in , the receiving node may accept even a replayed or forged message as valid. An attacker can also construct:

where is a newly generated nonce that appears valid, thereby allowing the clone node to initiate repeated authentications.

Jain and Hussain’s protocol relies solely on symmetric key cryptography and lacks robust countermeasures against cloning, such as physical tamper resistance, key revocation, or anomaly-based intrusion detection. Consequently, the protocol cannot effectively prevent identity reuse or node impersonation stemming from physical compromise.

In UWSN environments, where real-time monitoring is limited and physical inspection is impractical due to the deployment context, detecting cloned nodes is particularly challenging. Therefore, Jain and Hussain’s protocol remains vulnerable to physical and cloning attacks due to both structural weaknesses and environmental constraints.

3.2.2. Replay Attack

In UWSN environments, where propagation delays are substantial and time synchronization among sensor nodes is difficult to maintain, ensuring the freshness of authentication messages becomes crucial. These environmental characteristics significantly amplify the vulnerability to replay attacks, wherein previously transmitted messages are maliciously reused to deceive the system.

While Jain and Hussain’s protocol incorporates timestamps and nonces in certain parts of the authentication process, it fails to include such freshness parameters in critical messages like and . This omission exposes the protocol to replay-based intrusions.

An adversary can capture a legitimate authentication message exchanged between nodes and store it locally. After a time delay , the adversary can retransmit the identical message to the recipient. Since the protocol lacks any form of freshness verification such as timestamps or session tokens, the replayed message is accepted as valid. For instance, a captured message is reused as follows:

The receiving node decrypts and processes the message as if it were a legitimate new request. This vulnerability arises because the protocol does not include mechanisms such as session tokens, timestamps, or challenge–response values to detect message freshness.

Similarly, the attacker can replay another message :

These replayed messages are interpreted as new authentication attempts, granting the adversary unauthorized access or causing unnecessary resource consumption. In UWSN environments, where communication is delayed and synchronization is unreliable, distinguishing replayed messages from fresh ones becomes especially difficult, thereby increasing the likelihood of a successful attack.

Therefore, due to the absence of freshness verification in essential messages, Jain and Hussain’s protocol remains highly vulnerable to replay attacks. This weakness is further exacerbated in the delay-prone and asynchronous communication environments typical of UWSN environments.

3.2.3. DoS Attack

DoS attacks aim to exhaust a sensor node’s computational and energy resources by continuously transmitting a large volume of authentication requests. In Jain and Hussain’s protocol, each incoming request triggers cryptographic computations, which consume both processing power and battery capacity.

As a result, if an adversary repeatedly sends forged authentication messages to a node , the node is forced to handle every incoming request. This leads to potential resource exhaustion and service disruption. For instance, the attacker may impersonate a legitimate node and flood with continuous authentication attempts, causing unnecessary computational overhead and energy depletion.

This type of attack becomes particularly severe in UWSN environments, where sensor nodes operate under strict energy limitations and physical maintenance is highly impractical. Furthermore, Jain and Hussain’s protocol does not incorporate any rate-limiting, anomaly detection, or filtering mechanisms to mitigate excessive or malicious traffic.

Consequently, the protocol remains vulnerable to resource-based DoS attacks, especially in UWSN environments where resilience against such energy-draining threats is critical.

3.2.4. Mutual Authentication Issue

Although Jain and Hussain’s protocol claims to provide mutual authentication between sensor nodes and the base station, it relies solely on symmetric key cryptography, which introduces several limitations. Each node authenticates its peer using pre-shared secret keys. However, this approach inherently assumes that all key materials remain secure throughout deployment.

If an adversary compromises a sensor node and extracts its shared key, the attacker can impersonate the legitimate node and bypass mutual authentication with or the base station. In symmetric key infrastructures, the compromise of a single key undermines the entire trust relationship in both directions. Moreover, Jain and Hussain’s protocol lacks mechanisms for key revocation, re-authentication, or dynamic key updates. Without such recovery mechanisms, the system cannot recover from key compromise events. As a result, the protocol fails to guarantee robust and continuous mutual authentication in realistic and adversarial deployment environments.

4. Proposed Protocol

In this section, we propose a secure and lightweight authentication protocol specialized for underwater environments to address the security shortcomings of Jain and Hussain’s protocol. The proposed protocol consists of three phases: Registration, authentication, and continuous authentication phases. Table 2 shows the basic notations and descriptions of the proposed protocol.

Table 2.

Notation of proposed protocol.

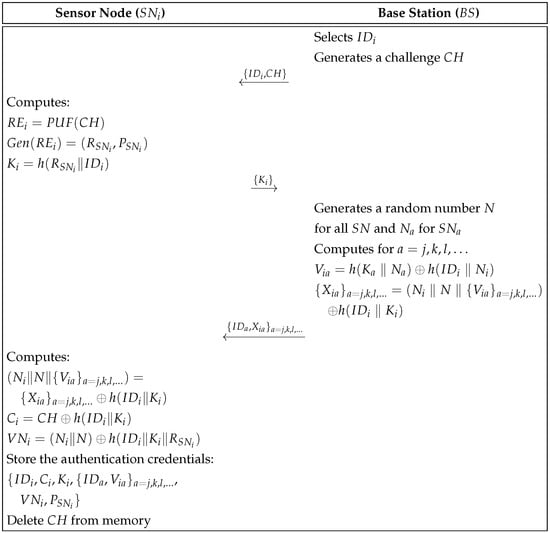

4.1. Registration Phase

The registration phase is the process where establish initial communication with the and share key information required for authentication. This phase is conducted securely through a secure channel. In this paper, the “secure channel” refers to a protected setup step performed before deployment or during controlled maintenance (e.g., on-site configuration or a physically protected link), not the normal underwater acoustic communication link used during operation. All sensor nodes must go through the registration phase with the . Typically, in underwater environments, nodes operate based on confidentiality and are composed of highly reliable nodes with minimal operational redundancy. This completes the registration phase for sensor nodes. We show the registration phase in Figure 2 and details are as follows.

Figure 2.

Registration phase of the proposed protocol.

- Step 1:

- selects the unique identifier for and generates a random challenge . Then, sends and to through a secure channel.

- Step 2:

- computes , derives , and calculates . Then, sends to .

- Step 3:

- generates a network-wide random value N and additional random values . It computes and . Then, sends to .

- Step 4:

- calculates and . Then, stores and deletes from its memory.

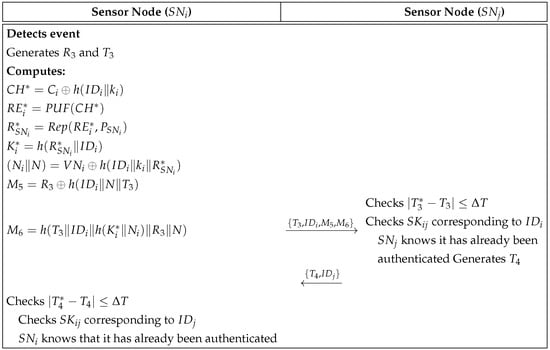

4.2. Authentication Phase

The authentication phase is the process where two sensor nodes in the network mutually verify their trustworthiness and establish a session key necessary for secure communication. We show the authentication phase in Figure 3. This phase involves exchanging messages through a public channel and is conducted through the following steps:

Figure 3.

Mutual authentication and session key agreement phase of the proposed protocol.

- Step 1:

- detects an event and generates a random nonce and a timestamp . It computes the challenge value , followed by . Using , it reconstructs as , and calculates the secret key as . Then, it retrieves the network values and N from using , and computes and . Finally, sends the message to through the public channel.

- Step 2:

- Upon receiving the message at timestamp , verifies the validity of the timestamp by checking whether . If valid, retrieves corresponding to and computes the challenge value as . It then calculates , reconstructs , and derives the secret key . Using , it retrieves the network values and N as , and calculates . Next, it computes and checks whether . If the check fails, the process is terminated. Otherwise, generates a random nonce and records the timestamp , then calculates and . Finally, sends the message back to through the public channel.

- Step 3:

- Upon receiving the response at timestamp , verifies the validity of the timestamp by checking whether . If valid, calculates and then computes . It then verifies whether . If the check fails, the process is terminated. Otherwise, computes the session key as .

- Step 4:

- computes the same session key using If all computations are successful, mutual authentication is achieved, and a secure session key is established between and .

4.3. Continuous Authentication Phase

In UWSN environments, sensor nodes utilize acoustic signals because the propagation characteristics of acoustic waves are directly influenced by factors such as water density, salinity, and pressure. As a result, underwater communication has a shorter transmission range and higher signal attenuation compared to communication in the air. Moreover, water currents and physical obstacles can cause signal distortion and multipath interference, further destabilizing the communication link [23,24]. At the protocol level, if a message is corrupted and fails verification, the protocol execution is aborted and retried, and our lightweight continuous authentication procedure enables fast re-authentication after intermittent link disruptions. Thus, we propose the continuous authentication phase to consider unstable connections in UWSN environments. The continuous authentication phase ensures ongoing verification between two sensor nodes, and , after the initial session key has been established. This process is conducted over a public channel to maintain secure communication. Figure 4 shows the continuous authentication phase and the steps are as follows:

Figure 4.

Continuous authentication phase of the proposed protocol.

- Step 1:

- Sensor node detects an event and generates a random nonce along with a timestamp . It calculates the challenge value as and evaluates the PUF response using . Using this, reconstructs as and computes the secret key . The common and unique nonce values are derived as , and subsequently, calculates and . Finally, sends the message to over the public channel.

- Step 2:

- Upon receiving the message at timestamp , verifies the validity of the timestamp by checking . It then checks the existence of the session key corresponding to . If exists, determines that it has already been authenticated. generates a new timestamp and computes the message .

- Step 3:

- Upon receiving the message at timestamp , verifies the validity of the timestamp by checking . It confirms the continued authentication with based on the response, completing the continuous authentication process and ensuring secure and uninterrupted communication between and .

5. Security Analysis

The analysis in this section is limited to protocol-level security verification (mutual authentication and session key security) using BAN logic, the ROR model, and Scyther-based security verification. This verification does not aim to model physical-layer underwater channel behavior; such effects will be considered in future implementation and experimental studies.

5.1. Informal Analysis

5.1.1. Replay Attacks

An adversary captures messages , , , and transmitted via open channels. Then, the adversary submits these messages to the sensor node and to conduct the authentication process. However, and check the freshness of messages using timestamp and random nonces. Thus, the adversary cannot have advantage in this attack. Thus, the proposed protocol is secure against replay attacks.

5.1.2. MITM Attacks

In this attack, an adversary sends fake messages between and to authenticate with each sensor node. However, the adversary cannot generate and because these parameters are masked in the shared secret N. Thus, the proposed protocol can prevent MITM attacks.

5.1.3. Impersonation Attacks

Suppose that an adversary disguises as a sensor node and tries to authenticate with another sensor node. To be recognized as a legitimate sensor node, the adversary must generate . However, the adversary cannot compute because N is a shared key of sensor node and . Thus, the proposed protocol can prevent impersonation attacks.

5.1.4. Physical and Cloning Attacks

In this attack, the adversary obtains a sensor node and extracts authentication credentials . After that, the adversary tries to generate the authentication request message using the credentials. However, the adversary cannot compute the message because and N are encrypted with , which is generated by . Therefore, the proposed protocol can prevent stolen smart device attacks.

5.1.5. Ephemeral Secret Leakage (ESL) Attacks

Assume that an adversary obtains and , and attempts to compute the session key . However, the adversary does not have any advantage because , , , and are encrypted with and which can be retrieved using . Thus, the proposed protocol is secure against ESL attacks.

5.1.6. DoS Attacks

In this attack, the adversary collects numerous messages transmitted via public channels and sends them to the other sensor node. In the proposed protocol, sensor nodes always check the timestamp and discard the message if it does not arrive within the allowance period. Thus, the proposed protocol can prevent DoS attacks.

5.1.7. Mutual Authentication

In the proposed protocol, timestamps are included in messages. Thus, sensor nodes can verify the freshness of the messages. Moreover, sensor nodes check the freshness of random nonces and using the shared secret N. If these parameters are valid, each sensor node can ensure the legitimacy of messages. Thus, the proposed protocol guarantees mutual authentication.

5.2. BAN Logic

Mutual authentication is an essential property in security protocols. BAN logic [15] is a formal analysis to prove mutual authentication using logical rules, idealized forms, and assumptions. Although BAN logic provides an abstract, assumption-driven reasoning framework and may not capture all adversarial behaviors or implementation/channel-level details, we utilize BAN logic to prove logical mutual authentication of the proposed protocol. We show the notations and descriptions of the BAN logic in Table 3.

Table 3.

Notations and descriptions.

5.2.1. Rules

In BAN logic, there are five rules to analyze authentication protocols.

- Message meaning rule (MMR): MMR is a rule when an entity receives a message encrypted with a shared key, the entity trusts the message.

- Nonce verification rule (NVR): NVR is a rule that believes a message was sent from a sender if the message content is fresh and the sender is sure to have sent it.

- Jurisdiction rule (JR): JR is a rule about permissions, meaning that if you have permission to receive a message, the other party can also receive the message.

- Belief rule (BR): BR is that if an entity believes a tuple, it also believes its elements.

- Freshness rule (FR): FR is a rule that believes that if a message is fresh, then its tuples are also fresh.

5.2.2. Goals

In our protocol, the network participants are required to authenticate each other and establish a session key to provide secure communication and prevent data leakage issues. Thus, the goals of our protocol in BAN logic are that the participants are legitimate and share session key securely. Thus, goals of our protocol can be shown as follows:

- Goal 1:

- Goal 2:

- Goal 3:

- Goal 4:

5.2.3. Idealized Forms

In the proposed protocol, and exchange messages and to establish the session key . Thus, the idealized forms of the proposed protocol are shown as follows:

5.2.4. Assumptions

To apply BAN logic, we introduce assumptions to reflect the pre-established trust and freshness of the proposed protocol. These assumptions can be derived according to registration phase, and freshness of random nonce and timestamps. Assumptions of BAN logic in our protocol are shown as follows:

- :

- :

- :

- :

- :

- :

5.2.5. BAN Logic Proof

Based on the idealized forms and assumptions, we prove the goals by applying the BAN logic rules to the message flow of the proposed protocol.

- Pr1:

- We get from .:

- Pr2:

- Using , we get from MMR and .:

- Pr3:

- Using , we get from FR and .:

- Pr4:

- Using , we get from NVR and .:

- Pr5:

- We get from .:

- Pr6:

- Using , we get from MMR and .:

- Pr7:

- Using , we get from FR and .:

- Pr8:

- Using , we get from NVR and .:

- Pr9:

- Using , and can compute the session key. Thus, we get and as follows:: (Goal 1): (Goal 4)

- Pr10:

- Using and , we get and from JR as follows:: (Goal 3): (Goal 2)

5.3. ROR Model

If the session key security is not preserved, the reliability of the proposed protocol cannot be guaranteed. Thus, we verify the security of the session key using ROR model [16]. In our protocol, we define participants for sensor nodes () and (). Note that and are instances. In ROR model, the attacker can perform various queries using the abilities where can eavesdrop, capture, insert, and delete messages.

- : can eavesdrop messages that are exchanged via public channels. Thus, this query is a passive attack.

- : It is an active attack that can send messages to network participants via public channels.

- : can extract secret parameters of and . Thus, this query is an active attack.

- : In this query, tests the security of the session key by flipping an unbiased coin. After that, obtain the result 1, 0, and . When 1 is obtained, it means that can distinguish the session key. When 0 is obtained, cannot distinguish the session key and random nonce. Otherwise, gets value.

Theorem 1.

We define that is the probability of breaking the session key security. Moreover, we define that C’, s’, , and are Zipf’s parameters [25], queries of send, PUF, and hash, respectively. The advantage that breaks the security of PUF and the range space of hash functions are and , respectively. Therefore, can be shown as follows:

In our protocol, we define four games following the related works [26,27,28]. Note that the probability of winning the game is ().

: This game is a initial game that guesses with no information of the proposed protocol. Thus, selects a random bit q. Thus, we can get the following:

: executes query to obtain and which are transmitted through public channels. With the information, guesses the session key from . However, the adversary cannot obtain any information because is masked in the long-term secret parameter N. Thus, we can get the following:

: In this game, tries to calculate the session key using hash and send queries. Using these queries, attempts to decrypt and to reveal the random nonce and . However, cannot obtain these parameters due to the “cryptographic one-way hash function”. Thus, the adversary does not have any advantages in this game and we get the following inequation using birthday paradox [29]:

: This is the last game that performs query and reveals secret parameters and . Then tries to calculate N to decrypt and . However, the adversary cannot retrieve secret parameters from the extracted information and because they are encrypted by PUF. Thus, we can get the following:

After , guesses a bit p and the following is obtained:

Using the triangular inequality, the following is obtained:

Multiplying 2, we can get the following:

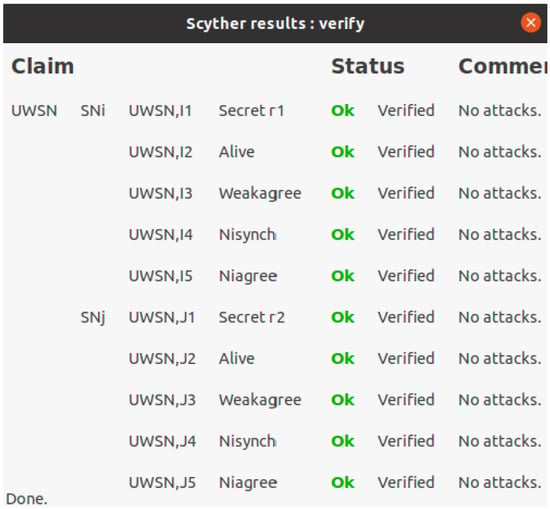

5.4. Security Verification Using Scyther

Scyther [17,18] is an automated verification tool to analyze and verify the security of authentication protocols, and detects various attack scenarios. Scyther tool verifies security properties through multiple independent executions for security protocols, and is widely used for research purposes due to its intuitive interface. Scyther tool can be executed on various operating systems such as Windows, Linux, and Mac OS X. The security protocols are described in a dedicated description language, “Security Protocol Description Language (SPDL)”. Then, Scyther tool automatically performs verification and outputs analysis results based on claim events, such as “Aliveness”, “Weak Agreement”, “Non-injective Agreement”, and “Non-injective Synchronization”. If “OK” and “No attacks” are displayed for each claim, it means that the corresponding security property is satisfied. It should be noted that Scyther performs verification under the Dolev–Yao adversary model and does not simulate physical-layer channel noise (e.g., bit errors due to attenuation or multipath). Therefore, our Scyther-based verification focuses on protocol-level properties (e.g., authentication and session key secrecy) against an active attacker who can eavesdrop, replay, and modify messages. In the SPDL model, we represent the main protocol participants as roles (e.g., SN and BS) and verify the security claims for representative protocol sessions. Regarding denial-of-service (DoS), Scyther is not intended to model resource-exhaustion effects; thus, DoS resilience is discussed based on the protocol design choices (lightweight operations and early verification checks) and the comparative overhead analysis in the performance section. Figure 5 shows the Scyther verification results for the proposed protocol.

Figure 5.

Scyther simulation results under claim events.

- Aliveness: The participant ensures that the communication partner actually performs the protocol.

- Weak-agreement: The participant ensures that the communication partner actually performs the protocol and is aware of who they were communicating with.

- Non-injective agreement: The participant ensures that there is a mutual agreement between communication parties and that they share consistent session values.

- Non-injective synchronization: The participant ensures that messages are exchanged in a given order and that the session flow was synchronized.

6. Performance Analysis

This section evaluates the performance of our proposed protocol in terms of security properties, computational costs, and communication costs. The goal of this analysis is to show that the proposed protocol provides enhanced security coverage while maintaining moderate computational cost, indicating its practicality for underwater deployments. Compared with existing protocols, the proposed method achieves a reasonable balance between security robustness and efficiency, suggesting that it can be feasibly implemented in real underwater sensor systems. It should be noted, however, that the evaluation in this paper is conducted at the protocol/analytical level, focusing on security verification and overhead comparison. More comprehensive statistical analysis and illustrative real-world demonstrations under practical underwater channel conditions (e.g., intermittent connectivity and packet errors) are beyond the scope of the current study and will be addressed in future work through implementation and empirical validation.

6.1. Security Properties

As presented in Table 3, the proposed authentication protocol satisfies all core security attributes, whereas existing protocols overlook several of them either partially or entirely. For example, the protocols by Xie et al. [30] and Algarni et al. [31] are vulnerable to physical cloning attacks and ESL attacks, respectively. Jain and Hussain’s protocol [14] is vulnerable to replay, MITM, and DoS attacks, primarily due to the absence of nonce- or timestamp-based freshness mechanisms and rate-limiting strategies. Moreover, none of the existing protocols considered in this study support continuous authentication, which is a critical requirement in highly dynamic and resource-constrained UWSNs, where intermittent connectivity and session instability are common. In contrast, the proposed protocol is specifically designed to maintain authentication continuity under such conditions, thereby enhancing its applicability to real-world deployments.

This continuous verification capability is particularly valuable in UWSN environments, where environmental interference, multipath distortion, and acoustic signal attenuation frequently disrupt communication. By supporting ongoing re-authentication after the initial session is established, the proposed protocol ensures that security is not compromised even if the connection is temporarily lost and then resumed. This not only prevents potential session hijacking or impersonation during link recovery but also reinforces session integrity throughout the mission duration.

6.2. Computation Costs

This subsection analyzes and compares the computational complexity of the proposed authentication protocol with three representative protocols: Jain and Hussain [14], Xie et al. [30], Algarni et al. [31], and Yang and Zou [13].According to [32], the evaluation of the execution time is conducted using Raspberry-Pi 4B (ARM Cortex A72 @ 1.5GHz 4 core CPU, 8GB RAM, Ubuntu 20.04.2 LTS). Moreover, the evaluation is based on the execution time of standard cryptographic operations, which are adopted for a fair relative comparison among protocols rather than for absolute benchmarking, since actual execution time can vary depending on hardware specifications and implementation details.

- -

- TH: One-way hash function—0.006 ms

- -

- TM: Elliptic curve point multiplication—2.926 ms

- -

- TS: Symmetric key encryption/decryption—0.013 ms

- -

- TF: Fuzzy extractor—2.926 ms

- -

- TE: Modular exponentiation—0.358 ms

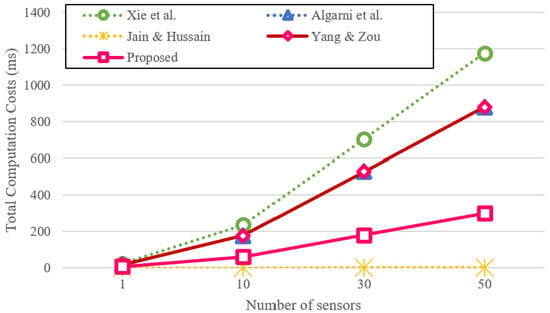

For transparency, the computation of each protocol is expressed in terms of the number of primitive operations (e.g., hash, FE, ECC), and their weighted sum is shown in Table 4. We also show the total computation costs of the proposed protocol and the related works [13,14,30,31] in Figure 6 and Table 5.

Table 4.

Security properties of the proposed protocol and related protocols.

Figure 6.

Total computation costs depending on the number of sensor nodes.

Table 5.

Computation costs of the proposed protocol and related protocols.

The results show that the proposed protocol requires slightly higher computational cost than Jain and Hussain’s protocol [14] due to the inclusion of additional hash and fuzzy-extractor operations. However, it achieves significantly stronger security properties while maintaining far lower complexity than the ECC-based protocols of Xie et al. [30] and Algarni et al. [31]. Specifically, Xie et al.’s method requires about 23.49 ms and Algarni et al.’s protocol about 17.59 ms per computation, whereas the proposed protocol performs the same authentication process in approximately 5.97 ms, reducing the computational burden by approximately three to four times compared to ECC-based protocols. This demonstrates that the proposed design maintains a reasonable balance between security robustness and computational efficiency, which is suitable for resource-constrained underwater environments.

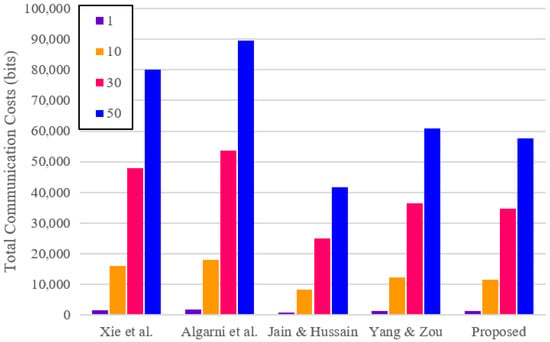

6.3. Communication Costs

This subsection evaluates the communication overhead of the proposed protocol compared with three existing protocols, including Jain and Hussain [14], Xie et al. [30], and Algarni et al. [31]. We define that the total bits of ECC point, hash function, random number, timestamp, and identity are 320 bits, 256 bits, 128 bits, 32 bits, and 32 bits, respectively [33]. Table 6 and Figure 7 show the total communication costs of the proposed protocol and related protocols [13,14,30,31]. The result shows that the proposed protocol requires 320 bits more than Jain & Hussain’s protocol. However, the proposed protocol achieves lower communication cost compared with Xie et al.’s protocol [30], Algarni et al.’s protocol [31], and Yang and Zou’s protocol [13]. In addition, the proposed protocol is a suitable protocol for UWSN environments, which reflects the special characteristics, such as supporting continuous authentication and providing high security.

Table 6.

Total communication cost of the proposed protocol and the related protocols.

Figure 7.

Total communication costs depending on the number of sensor nodes.

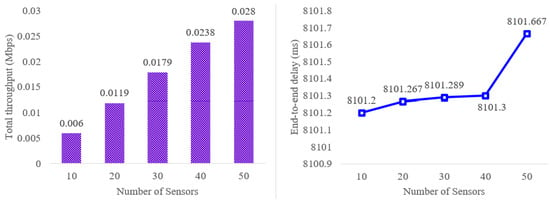

6.4. Simulation Study Using NS-3

We simulate the proposed protocol and derive throughput, end-to-end delay using NS-3 [34] to evaluate the realistic environment applicability. In the proposed protocol, there are two messages in the authentication phase: = 72 bytes, = 72 bytes. Based on the messages, we construct the underwater environments where sensors communicate with each other. We also specify the NS-3 simulation environments to fit underwater communications as follows:

- Operation System: Ubuntu 16.04 LTS

- CPU: Intel i9-13900 (13th Gen Intel Core 24 cores/32 threads, up to 5.60 GHz) (Intel, Santa Clara, CA, USA)

- Memory: 8GB RAM

- Simulation Time: 2000 s

- Number of Sensors: 10, 20, 30, 40, 50

- Mobility Model: ConstantPositionMobilityModel

- Underwater Stack: UanChannel and UanMacAloha

When the simulation is end, we can calculate throughput (, : Throughput, : Received total packets, : Packet size, : Total time) and end-to-end delay (, : End-to-end delay, : total message packets in authentication, : Received time, : Sent time) using flowmonitor files. The simulation results using NS-3 are shown in Figure 8. Based on the result, we can demonstrate that the throughput and end-to-end delay are increased as the number of sensors increases.

Figure 8.

Throughput and end-to-end delay results using NS-3.

7. Conclusions

Underwater acoustic communications inherently suffer from high attenuation, limited bandwidth, and intermittent connectivity, which makes coastal surveillance UWSNs particularly vulnerable to both operational disruptions and security threats. Motivated by these characteristics, we selected the mission-relevant protocol of Jain and Hussain as a baseline and identified critical limitations, including replay susceptibility, exposure to physical capture/cloning, denial-of-service potential, and incomplete mutual authentication. Based on these findings, we designed a secure and lightweight authentication and session key agreement protocol that combines hash/XOR-based computations with PUF-derived node binding and a continuous authentication procedure to support fast re-authentication after link disruptions. The security of the proposed protocol was validated at the protocol level through BAN logic, the ROR model, and Scyther-based security verification, while performance was assessed in terms of computational, communication overhead and security coverage compared with representative schemes. Overall, the results indicate that the proposed approach improves security robustness over the baseline while maintaining practical efficiency for surveillance-oriented UWSN deployments. In future work to validate the scientific contribution of the proposed protocol, we will move beyond protocol-level evaluation by implementing the proposed scheme on practical platforms (e.g., a USV or UUV/AUV). Moreover, we will conduct practical studies in an underwater acoustic networking testbed. Such experiments will enable more comprehensive statistical analysis and real-world case demonstrations, including latency, energy consumption, and re-authentication performance under dynamic channel conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.; formal analysis, D.K.; investigation, J.A.; methodology, J.A.; software, D.K.; supervision, Y.P.; validation, D.K. and Y.P.; writing—original draft, J.A.; writing—review and editing, D.K. and Y.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Science and ICT) (RS-2024-00450915).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ferri, G.; Munafò, A.; Tesei, A.; Braca, P.; Meyer, F.; Pelekanakis, K.; Petroccia, R.; Alves, J.; Strode, C.; LePage, K. Cooperative robotic networks for underwater surveillance: An overview. IET Radar Sonar Navig. 2017, 11, 1740–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidemann, J.; Stojanovic, M.; Zorzi, M. Underwater sensor networks: Applications, advances and challenges. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2012, 370, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terracciano, D.S.; Bazzarello, L.; Caiti, A.; Costanzi, R.; Manzari, V. Marine robots for underwater surveillance. Curr. Robot. Rep. 2020, 1, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.-S.N.; Hussein, L.A.; Ariffin, S.H.S. Analyzing the performance of acoustic channel in underwater wireless sensor network (UWSN). In 2010 Fourth Asia International Conference on Mathematical/Analytical Modelling and Computer Simulation; IEEE: Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia, 2010; pp. 550–555. [Google Scholar]

- El-Rabaie, S.; Nabil, D.; Mahmoud, R.; Alsharqawy, M.A. Underwater wireless sensor networks (UWSN), architecture, routing protocols, simulation and modeling tools, localization, security issues and some novel trends. Netw. Commun. Eng. 2015, 7, 335–354. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, K.F.; Kabir, K.H.; Abdelgawad, A. Advancement of routing protocols and applications of underwater wireless sensor network (UWSN)—A survey. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2020, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.A.; Taher, K.A. A novel authentication mechanism for securing underwater wireless sensors from Sybil attack. In 2021 5th International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Information Communication Technology (ICEEICT); IEEE: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Almuhaideb, A.M.; Al-Khulaifi, D.M. An efficient authentication and key agreement scheme for the Internet of Underwater Things (IoUT) environment. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 175773–175789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapileswar, N.; Phani Kumar, P. Energy efficient routing in IoT based UWSN using bald eagle search algorithm. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2022, 33, e4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Guqhaiman, A.; Akanbi, O.; Aljaedi, A.; Chow, C.E. Lightweight multi-factor authentication for underwater wireless sensor networks. In 2020 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI); IEEE: Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2020; pp. 188–194. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, C.M.; Amin, R.; Brindha, M. SafeCom: Robust mutual authentication and session key sharing protocol for underwater wireless sensor networks. J. Syst. Archit. 2022, 130, 102650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatwani, C.; Roy, S. Security analysis of ECC based authentication protocols. In 2015 International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Communication Networks (CICN); IEEE: Jabalpur, India, 2015; pp. 1167–1172. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.; Zou, Z. An authentication and key agreement protocol for whole process open channel in D2D. In Proceedings of the 2025 4th International Symposium on Computer Applications and Information Technology (ISCAIT), Xi’an, China, 21–23 March 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 1475–1481. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, U.; Hussain, M. Security mechanism for maritime territory and frontier surveillance in naval operations using wireless sensor networks. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2021, 33, e6300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, M.; Abadi, M.; Needham, R.M. A logic of authentication. ACM Trans. Comput. Syst. 1990, 8, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, M.; Fouque, P.A.; Pointcheval, D. Password based authenticated key exchange in the three-party setting. In Public Key Cryptgraphy; Springer: Les Diablerets, Switzerland, 2005; pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Cremers, C.J. The Scyther Tool: Verification, Falsification, and Analysis of Security Protocols: Tool Paper. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Aided Verification, Princeton, NJ, USA, 7–14 July 2008; pp. 414–418. [Google Scholar]

- Scyther Tool. Available online: https://people.cispa.io/cas.cremers/scyther/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Dolev, D.; Yao, A. On the security of public key protocols. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1983, 29, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Park, K.; Park, Y. A machine learning attack-resistant PUF-based robust and efficient mutual authentication scheme in fog-enabled IoT environments. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 20652–20669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazid, M.; Bagga, P.; Das, A.K.; Shetty, S.; Rodrigues, J.J.; Park, Y. AKM-IoV: Authenticated key management protocol in fog computing-based Internet of vehicles deployment. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 8804–8817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodis, Y.; Reyzin, L.; Smith, A. Fuzzy extractors: How to generate strong keys from biometrics and other noisy data. In Advances in Cryptology-EUROCRYPT 2004, Proceedings of the International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Interlaken, Switzerland, 2–6 May 2004; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 523–540. [Google Scholar]

- Heidemann, J.; Ye, W.; Wills, J.; Syed, A.; Li, Y. Research challenges and applications for underwater sensor networking. In IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC 2006); IEEE: Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 228–235. [Google Scholar]

- Felemban, E.; Shaikh, F.K.; Qureshi, U.M.; Sheikh, A.A.; Qaisar, S.B. Underwater sensor network applications: A comprehensive survey. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2015, 11, 896832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Cheng, H.; Wang, P.; Huang, X.; Jian, G. Zipf’s law in passwords. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2017, 12, 2776–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S.; Lee, J.; Park, Y.; Park, Y.; Das, A.K. Design of blockchain-based lightweight V2I handover authentication protocol for VANET. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2022, 9, 1346–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, D.; Thakur, G.; Kumar, P.; Das, A.K.; Park, Y. Blockchain assisted intra-twin and inter-twin authentication scheme for vehicular digital twin system. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 15002–15015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.; Son, S.; Lee, J.; Park, Y.; Park, Y. Design of secure mutual authentication scheme for metaverse environments using blockchain. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 98944–98958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyko, V.; MacKenzie, P.; Patel, S. Provably secure password-authenticated key exchange using Diffie-Hellman. In Proceedings of the International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Bruges, Belgium, 14–18 May 2000; pp. 156–171. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Q.; Zhang, J. Lightweight drone-to-ground station and drone-to-drone authentication scheme for Internet of drones. Symmetry 2025, 17, 556–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algarni, A.D.; Innab, N.; Algarni, F. A verifiably secure and robust authentication protocol for synergistically-assisted IoD deployment drones. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, 314475–314503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.; Son, S.; Kim, M.; Lee, J.; Das, A.K.; Park, Y. A secure self-certified broadcast authentication protocol for intelligent transportation systems in UAV-assisted mobile edge computing environments. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 19004–19017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagga, P.; Das, A.K.; Wazid, M.; Rodrigues, J.J.; Choo, K.K.R.; Park, Y. On the design of mutual authentication and key agreement protocol in Internet of Vehicles-enabled intelligent transportation system. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 1736–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Network Simulator 3. Available online: https://www.nsnam.org (accessed on 26 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.