Abstract

As shallow coal resources become increasingly depleted, coal mining is extending to greater depths, making mine thermal hazards an increasingly prominent issue. This paper proposes a novel system for synergistic geothermal energy extraction from deep coal mine aquifers and coal seam cooling, aimed at achieving integrated geothermal exploitation and mine thermal hazard control. Based on a high-temperature mine in the Yuanyanghu Mining Area of Ningxia, a dual-stage, single-branch three-dimensional numerical model was established to simulate the effects of water injection pressure, water injection temperature, and level spacing on the system’s cooling performance and geothermal energy extraction efficiency. The results indicate that increasing injection pressure enhances early-stage geothermal energy extraction capacity and coal seam cooling rate, but the heat extraction power declines over long-term operation as the produced water temperature approaches the injection temperature. Lowering injection temperature significantly improves water–rock heat exchange efficiency, accelerates coal seam cooling, and increases geothermal energy extraction. Increasing level spacing helps improve geothermal energy extraction power but weakens the direct cooling effect on the coal seam. Considering the influence patterns of each parameter, the optimal combination was determined as water injection pressure of 10 MPa, water injection temperature of 10 °C, and level spacing of 80 m, which delivers the best overall performance by enabling rapid coal seam cooling and sustained geothermal energy extraction, with a cumulative geothermal output reaching 129.45 MW after 10 years of operation. This study provides a theoretical basis and technical reference for the integrated management of thermal hazards and geothermal resource development in deep coal mines.

1. Introduction

Due to the intensive exploitation, shallow coal resources are becoming increasingly depleted, shifting the focus of coal mining gradually toward deep resources and making their development increasingly urgent [1,2]. However, deep mining is accompanied by a series of technical and environmental challenges, among which mine thermal hazards are particularly prominent. According to statistics, below the constant temperature zone, rock temperature increases with depth at a gradient of 1.7–3.0 °C/100 m [3]. The original rock temperature in existing deep mining shafts can reach up to 37 °C [4]. Severe mine thermal hazards adversely affect the health and work efficiency of underground personnel, necessitating substantial investments to improve the underground environment [5]. Meanwhile, the existing mine cooling technology system remains inadequate, relying primarily on artificial refrigeration and non-artificial cooling methods [6,7,8]. These approaches generally suffer from limitations such as insufficient cooling capacity, high initial investment, poor economic viability, and inadequate applicability, which severely constrain the efficient exploitation of deep coal resources [9,10]. The thermal energy stored in deep mines actually represents a vast potential source of renewable energy. If such geothermal resources can be effectively developed and utilized, it would not only alleviate underground high temperatures and control thermal hazards but also transform a disadvantage into a valuable resource [11,12]. The extracted heat can be used to meet daily heating demands in mining areas (such as building heating in winter and hot water for bathing), thereby reducing reliance on traditional energy sources and enhancing the overall economic benefits and sustainability of coal mines.

In recent years, extensive research has been conducted on mine thermal hazard management and geothermal energy development. Regarding thermal hazard control, Yan et al. [13] developed a fully coupled hydraulic-mechanical (HM) dual-medium model for the Chensilou Coal Mine via numerical simulation. Their findings indicate that geothermal reinjection amplifies mining-induced disturbance to faults, whereas positioning production wells near or within faults aids in stability control. Chen et al. [14] proposed a split-type vapor compression refrigeration (SVCR) system through numerical simulation and compared it with chilled-water and ice-slurry systems. Their results demonstrate that the SVCR system exhibits superior thermal performance under moderate mining depths and not excessively low evaporation temperatures. Based on field measurements, numerical simulations, and engineering applications, Zhao et al. [15] introduced a coordinated “heat-source barrier + cooling equipment” strategy that consistently maintained ambient temperature below 30 °C in a high-temperature working face, achieving energy savings of 10% during high-temperature periods and over 50% during low-temperature periods. In the realm of mine geothermal energy development, Wang et al. [16] constructed three 3D models (RG, RP, and GP) for the Jiahe Coal Mine in Xuzhou via numerical simulation. Their findings indicate that the RG model more accurately reflects actual conditions, and that intermittent and cyclic thermal storage modes can improve system efficiency. By combining geochemical analysis, hydrogen-oxygen isotope tracing, and underground transient electromagnetic methods, Zhen et al. [17] elucidated the geothermal accumulation mechanism in the Pingdingshan No. 10 Mine. The implemented system yielded an annual net profit of USD 412,990 and an annual CO2 reduction of 9471 tons. Through techno-economic analysis, Menéndez et al. [18] confirmed that mine water from flooded Spanish mines can provide stable thermal energy for building heating and cooling, with a CO2 emission factor as low as 0.048 kg CO2/kWh. Wang et al. [19] numerically verified the feasibility of seasonal thermal energy storage in underground coal mine reservoirs, demonstrating an effective heat recovery rate exceeding 70%, which surpasses the performance of aquifer thermal storage systems. Employing value-chain and energy-system analyses, Gerbelová et al. [20] found that replacing coal-fired power plants with geothermal facilities in Slovakian coal regions could reduce CO2 emissions by 34% and stimulate related industries such as geological exploration. To advance the integrated management of geothermal exploitation and thermal hazard control in deep mining, Li et al. [21] constructed numerical fluid-dynamics and heat-transfer models, highlighting the significant influence of geological stratification on mine thermal storage efficiency. They identified an optimal rock configuration with “high thermal conductivity near heat exchange pipes and low thermal conductivity farther away.” Yan et al. [22] established a thermal-hydraulic-mechanical (THM) coupled model, showing that mining-induced stress creates alternating zones of high and low fracture apertures, which constrict effective flow channels and lead to declining production capacity with increasing extraction distance. Through numerical simulation, Lv et al. [23] clarified the four-stage evolution pattern of floor failure during coordinated coal and geothermal energy extraction in deep mines. Existing research reveals that most studies on coal mine geothermal development focus on abandoned or closed mines, whereas investigations into the coordinated extraction of coal and geothermal resources remain inadequate. There is a pressing need to explore in depth the cooling effect on coal seams achieved through geothermal energy extraction both during and prior to mining operations. Current research indicates that the field of geothermal development primarily focuses on Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS) and the co-extraction of mine geothermal resources. The core revolves around multi-field coupling mechanisms such as thermal-hydraulic-mechanical processes, with emphasis on investigating the effects of natural fractures, geological parameters, and engineering parameters on hydraulic fracturing outcomes, heat extraction efficiency, and engineering safety. A series of significant findings have been established: Khalaf et al. [24] investigated the influence of cold fluid injection on stress field redistribution and fracture propagation behavior in geothermal reservoirs using thermo-poroelasticity theory and the displacement discontinuity method. Their research demonstrated that thermal exchange between cold fluid and hot rock can significantly increase fracture aperture, enhance injection efficiency, and induce a 90° reorientation of the minimum principal stress direction, thereby altering fracture growth paths. Zhang et al. [25] through the establishment of a fully coupled THMD model, demonstrated that a low in situ stress ratio leads to hydraulic fractures preferentially propagating along natural fractures, that elevated reservoir temperature facilitates hydraulic fracture propagation, and that natural fractures can guide hydraulic fractures to form heterogeneous zones. Long et al. [26] by constructing a THM coupled model based on FDEM incorporating natural fractures with three cementation types, showed that horizontal stress difference is the dominant factor affecting fracture network complexity, that increased reservoir temperature promotes the opening of natural fractures, and that injection flow rate has a more pronounced impact on fracture morphology than fluid viscosity. Liu et al. [27] by developing a three-dimensional THM coupled model validated against theoretical solutions and field measurements, found that heat extraction efficiency is lower when a single natural fracture is located between the injection and production wells, while multiple natural fractures can expand the cooling zone and significantly enhance heat extraction efficiency. Zhao et al. [28] by constructing a THMV coupled model integrating multiple physical fields, revealed that lowering the injection temperature improves heat extraction and cooling effects but increases roadway stress, that increasing injection volume is detrimental to sustainable extraction, and that a higher geothermal gradient significantly increases cumulative heat production. Jiang et al. [29] through establishing a THM coupled model considering temperature-dependent water properties and thermal-induced stresses, indicated that variations in water properties and the stress field can increase the Darcy velocity within fractures, that fracture aperture has a greater influence on the temperature field than density, and that uniformly distributed DFNs are more suitable for EGS reservoirs.

In summary, existing research has provided a foundation for mine thermal hazard control, geothermal energy development, and geothermal energy systems. However, technologies currently applied in active mines are constrained by issues such as limited cooling coverage, slow response times, and the risk of water inrush associated with cooling by water injection. Furthermore, the absence of integrated system-level design hinders the ability to meet the requirements for safe and efficient mining in deep, high-temperature coal seams. Consequently, it is imperative to develop a safe methodology that can achieve underground cooling while mitigating water inrush hazards, thereby enabling safe coal face operations alongside efficient geothermal energy utilization. To address the aforementioned challenges, this study proposes a novel system for synergistic geothermal energy extraction from deep coal mine aquifers and coal seam cooling. The core innovations of this work are (1) a dual-stage, single-branch well layout combined with directional drilling technology, designed specifically for active deep coal mines to achieve simultaneous geothermal extraction and targeted coal seam cooling during mining operations; (2) a shift in application scenario from post mining geothermal recovery to integrated pre mining and mining phase implementation, enabling real time thermal hazard control alongside energy exploitation; (3) systematic parameter optimization and definition of safe operational boundaries for key injection production parameters (pressure, temperature, level spacing) to balance cooling performance with sustained heat extraction; and (4) a scalable field implementation methodology adaptable to varying geological and mining conditions. These advancements extend the existing “geothermal exploitation + heat hazard control” concept into a mining integrated, cooling oriented framework, offering a novel solution for the co-development of geothermal energy and thermal hazard mitigation in active deep coal mines.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Typical Mine and Technical Principle of the System

The Shicaocun coal mine is situated in the Yuanyanghu mining area of the Ningdong coalfield in Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region. It is classified as a Grade-I high-temperature mine, covering an area of approximately 31.4 km2. The mine employs a comprehensive development system combining a main inclined shaft, auxiliary vertical shafts, and return air inclined shafts, with the coal seam buried at a depth of 851 m. A total of 36 boreholes were deployed, including 3 approximately steady-state boreholes (S204, 1002, 1009) and 33 simplified temperature-measurement boreholes, these boreholes were deployed to systematically obtain ground temperature data in the study area, aiming to reveal the geothermal distribution patterns in deep coal seams. Specifically, all aligned along a southwest–northeast direction. Among them, borehole S307 reaches the maximum depth of 1100 m, penetrating the entire coal seam sequence within the mine field, and its bottom-hole temperature is 42.32 °C. In contrast, borehole S202 has the shallowest depth of 591 m, with a bottom-hole temperature of 30.06 °C. The average bottom-hole temperature across all measurement points is 35.42 °C. All data were used to establish the initial geothermal field model of the study area and served as the foundation for subsequent geothermal anomaly assessment and thermal hazard evaluation. Overall, the ground temperature exhibits an increasing trend with depth, with a maximum geothermal gradient of 3.41 °C/100 m—significantly higher than the national average for coal mines in China (2.0–2.5 °C/100 m) [28]. These findings indicate the presence of a pronounced geothermal anomaly in the deep sections of the mine, which complicates thermal hazard control. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop a novel synergistic system for geothermal energy extraction and coal seam cooling in deep coal mine aquifers. The geographical location of the Shicaocun coal mine is shown in Figure 1, and the field temperature measurement data are provided in Table 1 below.

Figure 1.

Geographic location map of the Shicaocun coal mine.

Table 1.

Continuous temperature measurement data from all temperature-measuring boreholes in the typical mine.

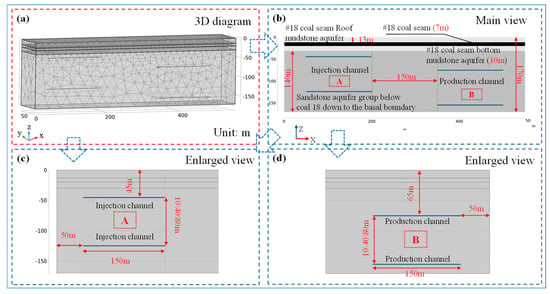

The geothermal energy extraction and coal seam cooling system for deep coal mine aquifers operates by drilling production and injection wells into the aquifer beneath the coal seam. Using water as the heat transfer medium, it extracts thermal energy from deep rock formations and delivers it to the surface. To achieve efficient rock cooling and heat extraction while improving borehole utilization, this system integrates multi-level directional branched drilling technology with a synergistic approach that combines mine thermal hazard control and geothermal exploitation. Numerical models are established to systematically analyze the operational performance of the multi-level branched layouts of the production and injection wells. Both injection and production wells consist of two sections: a vertical segment and a deviated (or inclined) segment. The injection channels are generally positioned at higher horizontal levels than the production channels, and the injection channels and production channels are located in different areas, as shown in Figure 2. Within the target aquifer, multiple branches are arranged along several horizontal planes, with the aquifer beneath the coal seam serving as the target layer for borehole completion. Cold water is injected into the deep formation through the injection well, evenly permeating the aquifer via its branched channels. During flow, the water undergoes heat exchange with the high temperature rock mass, gradually increasing in temperature while correspondingly lowering the temperature of the rock surrounding the injection branches. This enables large scale and efficient cooling of the coal seam. The heated water in the aquifer is then extracted to the surface through the production well and its branched network. The recovered thermal energy can be utilized for mining operations and residential heating within the mine.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the numerical model and mesh generation (10/40/80 m denote the vertical distances between injection and production wells under different layout schemes): (a) 3D diagram; (b) main view; (c) injection channel enlarged view; (d) production channel enlarged channel.

2.2. Establishment of Numerical Model

In this study, the numerical simulations were performed using COMSOL Multiphysics® software (Version 6.2), which integrates the Darcy’s Law and Heat Transfer in Porous Media modules for coupled fluid flow and heat transfer analysis. A dual-level, single-branch three-dimensional numerical model of the geothermal energy extraction and coal seam cooling system for deep coal mine aquifers was established using the Darcy’s Law and Heat Transfer in Porous Media modules. The model was developed to investigate the cooling performance under various parametric conditions. The unit model measures 550 m in length, 100 m in width, and 170 m in height, and is composed of 60,950 mesh elements. Both the injection and production channels are situated within the aquifer, each with a length of 150 m and a vertical separation of 150 m between their horizontal levels. The coal seam and the aquifer have thicknesses of 7 m and 140 m, respectively. All four lateral boundaries of the model are defined as no-flow, thermally insulated boundaries. Based on field measurements, the initial pressure is set to 2.25 MPa. The initial temperature field within the model was defined based on the geothermal gradient derived from the corrected borehole temperature measurements presented in Table 1, applying a linear increase with depth from the upper boundary. The diameters of the injection and production channels are 0.2 m. The simulation period spans 10 years. The mesh configuration and layout of the unit model are presented in Figure 2, and the parameters for each geological layer are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Model Parameters.

In the model, the Heat Transfer in Porous Media interface is added to couple the temperature field with the Darcy velocity field. The heat transfer process in the model is governed by the following Equation (1):

where ρ is density, kg/m3; Cp is the heat capacity, J/K; λ is the thermal conductivity, W/(m·°C); u is the Darcy velocity field, m/s; ∇T is the temperature difference, °C; and Qs is the heat source, W/m3.

Each rock layer in the model is defined as a porous medium. Given the low flow velocity and the resulting low Reynolds number within the aquifer, the flow regime remains in the Darcy range. Therefore, the Darcy–Forchheimer law, which accounts for inertial effects at higher velocities, is not required. Darcy’s law is sufficiently accurate for the conditions simulated in this study. By incorporating the Darcy’s Law interface, the flow of water in the pores of the rock layers is assumed to follow Darcy’s law. The Darcy velocity field is expressed as the following Equation (2):

where k is the permeability, m2; μ is the dynamic viscosity of the fluid, Pa·s; and ∇p is the pressure gradient, Pa/m.

2.3. Geothermal Resource Reserves

The geothermal resource reserves of the typical mine were evaluated using the thermal reservoir method. The calculation formula follows the standard thermal reservoir method widely used in geothermal potential assessment [30,31], expressed as the following Equation (3):

where Qtotal represents the geothermal resource potential, kJ; V is the volume of the thermal reservoir, m3; ρr and ρw denote the densities of rock and water, respectively, kg/m3; T is the average temperature of the thermal reservoir, °C; T0 is the reference temperature, °C; cr and cw are the specific heat capacities of rock and water, respectively, kJ/(kg·K); Φ is the rock porosity, %.

where RE is the recovery factor, %. Additionally, the heating power Wt can be calculated based on the recoverable geothermal energy [32,33], as shown in Equation (5):

where Wt is the heating power, MW; ΣWt is the annual utilizable geothermal energy, MJ (calculated over a 10-year period); D is the number of days per year dedicated to geothermal development, ×86,400 s; K is the heat efficiency ratio, typically taken as 0.6. Furthermore, the extractable geothermal fluid volume can be calculated using the following Equation (6):

where α is the standard coal conversion factor, typically taken as 4.1868. The parameters were obtained based on laboratory test results from the interim research report on the geothermal distribution patterns and mechanisms of thermal hazard formation in the No. 31 mining area of the typical mine.

Based on the occurrence conditions of the geothermal reservoir and the economic feasibility of development, the thickness of the thermal reservoir was determined to be 300 m, with the mine field area adopted as the assessment zone. In accordance with the geothermal occurrence characteristics of the Shicaocun Coal Mine, borehole geophysical data from the No. 18 coal seam were selected to represent the average temperature of the thermal reservoir. Using the thermal reservoir method, the geothermal resource potential of the Shicaocun area was thus calculated to be 1.29 × 1017 J. Assuming a recovery factor of 10%, the recoverable heat from the Shicaocun Coal Mine amounts to 1.29 × 1016 J. According to statistical data, the total heat within the Earth’s interior is approximately 170 million times the total known global coal reserves, with the practically usable portion equivalent to 494.8 trillion tons of standard coal [34]. Consequently, the total geothermal energy within the mine field can be converted to approximately 4.4 × 106 tons of standard coal equivalent, corresponding to a total thermal power of 13.6 MW. Assuming a heating load of 40 W/m2, the potential heating supply area reaches 340,000 m2. The above analysis indicates that the geothermal resources within this thermal reservoir are relatively abundant and hold certain exploitation value.

2.4. Model Validation

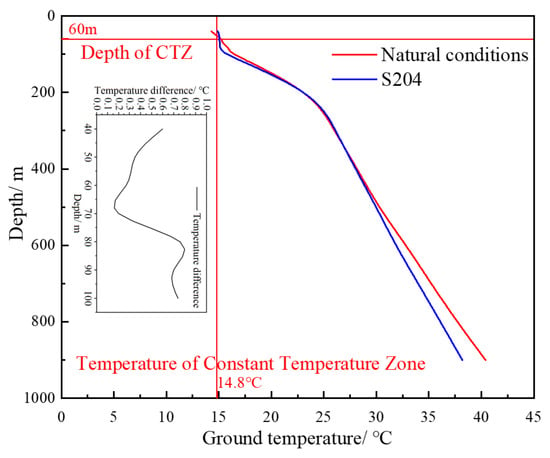

To ensure the reliability of the numerical model in simulating the thermal behavior of deep coal mine aquifers, a comprehensive model validation was conducted in this study. The validation process was carried out by comparing the simulated temperatures with field-measured temperature data from the Shicaocun Coal Mine. The field temperature data used for validation were obtained from 36 boreholes (as shown in Table 1). Specifically, downhole temperature data from borehole S204 were selected for validation. The numerical model was run under conditions without injection or production operations (under natural geothermal conditions), and the results were compared with the field temperature measurements, as shown in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3.

Model error verification.

The simulated temperature profile along borehole S307 (under natural geothermal conditions) was compared with field measurement data (as shown in Figure 3). The results indicate good agreement between the two, with an average relative error of less than 5% across the entire depth profile. This comparison confirms that the model’s initial temperature field and key rock properties (thermal conductivity and heat capacity) reasonably represent the actual mine conditions.

2.5. Simulation Scheme

The performance of the deep coal mine aquifer geothermal energy extraction and coal seam cooling system is evaluated primarily in terms of cooling effectiveness and heat extraction efficiency. Key performance indicators include the average aquifer temperature (Taq), the average coal seam temperature (Tcs), the extracted water temperature (Toutlet), and the geothermal energy extraction rate (Q). The main operational parameters identified as influential are the water injection pressure (Pwi), the water injection temperature (Twi), and the level spacing (Lls) between channels.

This study adopts a single-factor experimental approach to examine the effects of these parameters on the system’s operational performance in the numerical model, with the objective of identifying an optimal configuration. By varying one parameter at a time in the simulations and summarizing the results over a 10-year operational period, the influence mechanism of each parameter on system performance is elucidated. In accordance with the Coal Mine Safety Supervision Regulations, the temperature in a coal mine working face must not exceed 26 °C. Consequently, for evaluating cooling performance, achieving a temperature of 26 °C is defined as effective cooling. Furthermore, to reflect the need to reach suitable mining conditions promptly, the effective cooling width of the coal seam after two years of operation is used as a specific evaluation metric. The system’s heat extraction efficiency is assessed based on the extracted water temperature (Toutlet) and the geothermal energy extraction rate (Q). For the experimental design, three levels are assigned to each parameter (Pwi, Twi, Lls). When analyzing the effect of one parameter, the other two are held constant. The specific level values are listed in Table 3, and the corresponding simulation schemes are detailed in Table 4.

Table 3.

Parameter Level Schemes.

Table 4.

Simulation Schemes.

3. Simulation Results and Analysis

3.1. Water Injection Pressure

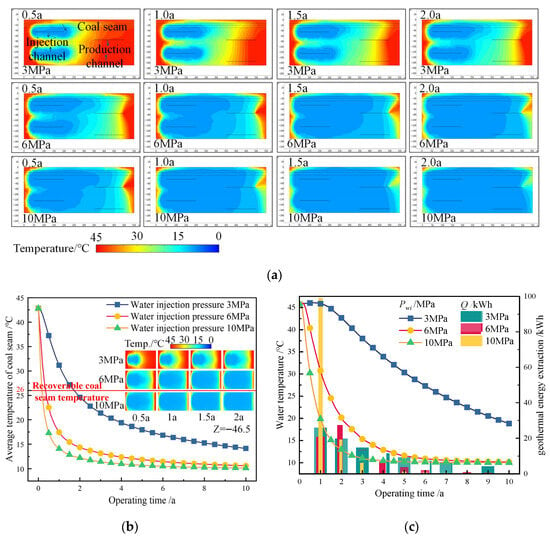

The influence patterns of different water injection pressures (The water injection temperature is set to 10 °C, and the level spacing is 80 m for all cases) on the cooling effectiveness and heat extraction efficiency of the deep coal mine aquifer geothermal energy extraction and coal seam cooling system are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Influence patterns under different water injection pressure conditions: (a) Temperature contours on the X-Z cross-section (at the middle of the model) within the study area; (b) average coal seam temperature curve and temperature contours on the central cross-section; (c) extracted water temperature curve and histogram of geothermal energy extraction.

As shown in Figure 4a: Within the study area, cooling effectiveness is enhanced with rising water injection pressure. During initial injection, the rock adjacent to the injection channel first exchanges heat with the cold injected water, leading to localized cooling. As a result, thermal convection develops along the flow field, propagating from the injection channel toward the production channel. After 0.5 years of simulation, the cooling-front advance is more pronounced at higher pressures: at injection pressures of 3, 6, and 10 MPa, the effective cooling widths reach 207.04 m, 385.17 m, and 468.61 m, respectively. After 2 years, the aquifer cooling effect strengthens further with increasing injection pressure, resulting in effective cooling across most of the rock mass in the study area. Because permeability and porosity are lower in the overlying strata, flow resistance rises when water migrates into the surrounding rock of the coal seam floor. This causes the primary flow direction to shift, extending laterally along the coal seam floor and thereby expanding the cooling zone along the seam strike.

As shown in Figure 4b: After two years of operation, the effective cooling widths of the coal seam measured 357.30 m, 487.03 m, and 517.29 m at injection pressures of 3, 6, and 10 MPa, respectively— demonstrating that a higher pressure yields a broader cooling extent within the same period. Following 10 years of simulation, the final average temperatures of the coal seam under these pressures were 14.14 °C, 10.62 °C, and 10.15 °C. Therefore, the time needed to cool the average seam temperature below the 26 °C threshold was reduced to 1.8 years, 0.4 years, and 0.2 years.

As shown in Figure 4c: The produced water temperature declines with both longer runtime and higher injection pressure. Although the geothermal energy extraction rate decreases over time, it rises with increased pressure during the first operational year. At lower injection pressures, thermal breakthrough is delayed, allowing extracted water to retain elevated temperatures for longer; however, the corresponding flow rate is lower, resulting in limited heat extraction power. Over a 10-year period, the average produced water temperatures at 3, 6, and 10 MPa were 31.85 °C, 16.26 °C, and 13.22 °C, respectively. By the end of the simulation, these temperatures fell to 18.83 °C, 10.19 °C, and 10.02 °C, while the corresponding average extraction rates reached 10.73 kWh, 13.33 kWh, and 12.94 kWh. After the sixth year, under 6 MPa and 10 MPa conditions, the water temperature approaches the injection temperature, causing a subsequent drop in heat extraction power. Thus, while higher pressure boosts early-stage extraction performance, its advantage diminishes over time.

In summary, as the injection pressure increases, the cooling effectiveness, coverage, and rate for both the aquifer and the coal seam are enhanced. When the water flow reaches the surrounding rock of the coal seam floor, it turns and spreads along the strike of the coal seam. After 10 years of operation, the final average temperatures of the coal seam under injection pressures of 3 MPa, 6 MPa, and 10 MPa are 14.14 °C, 10.62 °C, and 10.15 °C, respectively. The temperature of the extracted water decreases with longer operation time, and the reduction is more pronounced at higher pressures. The geothermal energy extraction rate increases with pressure during the first year, but after the sixth year of operation, the high-pressure cases experience a drop in heat extraction power as the extracted water temperature approaches the injection temperature, falling below that of the low-pressure case.

3.2. Water Injection Temperature

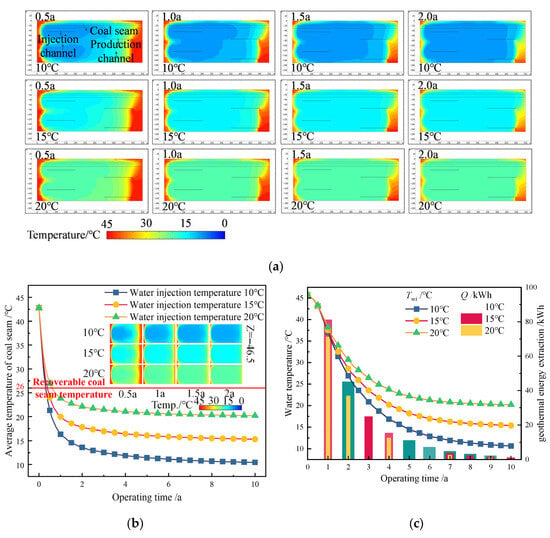

The influence patterns of different water injection temperatures (The water injection pressure is set to 6 MPa, and the level spacing is 80 m for all cases) on the cooling effectiveness and heat extraction efficiency of the deep coal mine aquifer geothermal energy extraction and coal seam cooling system are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Influence patterns under different water injection temperature conditions: (a) Temperature contours on the X-Z cross-section (at the middle of the model) within the study area; (b) average coal seam temperature curve and temperature contours on the central cross-section; (c) extracted water temperature curve and histogram of geothermal energy extraction.

As shown in Figure 5a: Within the study area, the cooling effectiveness decreases as the water injection temperature increases. The lower the injection temperature, the lower the resulting rock temperature after heat exchange. After 0.5 years of model operation, under different injection temperatures (10 °C, 15 °C, and 20 °C), the average aquifer temperatures are 21.16 °C, 24.05 °C, and 27.08 °C, respectively. After 1 year of operation, the average aquifer temperatures further decrease by 4.77 °C, 3.93 °C, and 3.05 °C compared to those at 0.5 years, representing reductions of 22.58%, 16.34%, and 11.26%, respectively. After 2 years of operation, the average aquifer temperatures are 13.42 °C, 17.69 °C, and 22.09 °C, corresponding to average temperature drops of 31.90 °C, 27.63 °C, and 23.23 °C from the initial condition. Therefore, for the same operating duration, a lower injection temperature results in a higher cooling rate within the study area.

As shown in Figure 5b: Higher water injection temperatures reduce both the cooling extent and rate of the coal seam. After two years, the coal seam exhibits significant cooling diffusion at injection temperatures of 10 °C, 15 °C, and 20 °C; lower temperatures correspond to greater average temperature reductions in the seam during this period. After 10 years, the final average seam temperatures under these conditions were 10.44 °C, 15.31 °C, and 20.21 °C, respectively, and the time required to cool the seam below 26 °C decreased accordingly to 0.3, 0.4, and 0.6 years. Thus, although injection temperature does not alter the flow-field direction or the propagation speed of the cooling front, a higher temperature reduces the thermal gradient between the injected water and the formation, thereby diminishing the heat flux and lowering overall cooling efficiency.

As shown in Figure 5c: The temperature of the extracted water increases with higher injection temperatures, whereas the geothermal energy extraction rate decreases as the injection temperature rises and also declines year by year with extended operating time. The thermal breakthrough times under different injection temperatures are identical. After thermal breakthrough is reached, the temperature of the extracted water gradually decreases. The average extracted water temperatures over 10 years at injection temperatures of 10 °C, 15 °C, and 20 °C are 19.27 °C, 22.44 °C, and 25.77 °C, respectively. The annual geothermal energy extraction rate throughout the operational period decreases with increasing injection temperature. The average heat extraction powers under the different injection temperatures are 21.00 kW, 18.63 kW, and 15.95 kW, respectively. Thus, heat extraction performance improves as the injection temperature is lowered. Hence, when applying the synergistic method for mine thermal hazard control and geothermal energy extraction, the injection temperature should be minimized as much as possible while ensuring compatibility with practical geothermal water utilization requirements.

In summary, increased water injection temperature reduces the cooling range and rate in both the aquifer and the coal seam. This is not due to changes in flow-field direction or cooling-front velocity, but rather results from a diminished thermal gradient between the injected water and the rock, which lowers the heat flux and thus reduces cooling efficiency. After two years, the aquifer experienced average temperature reductions of 31.90 °C, 27.63 °C, and 23.23 °C at injection temperatures of 10 °C, 15 °C, and 20 °C, respectively. Correspondingly, the time required to cool the coal seam below 26 °C increased from 0.3 years to 0.6 years as the injection temperature rose. Moreover, higher injection temperatures lead to warmer produced water and a lower geothermal energy extraction rate, with the latter also declining over time. Therefore, in practice, the injection temperature should be kept as low as operationally feasible while still meeting the requirements for geothermal utilization.

3.3. Level Spacing

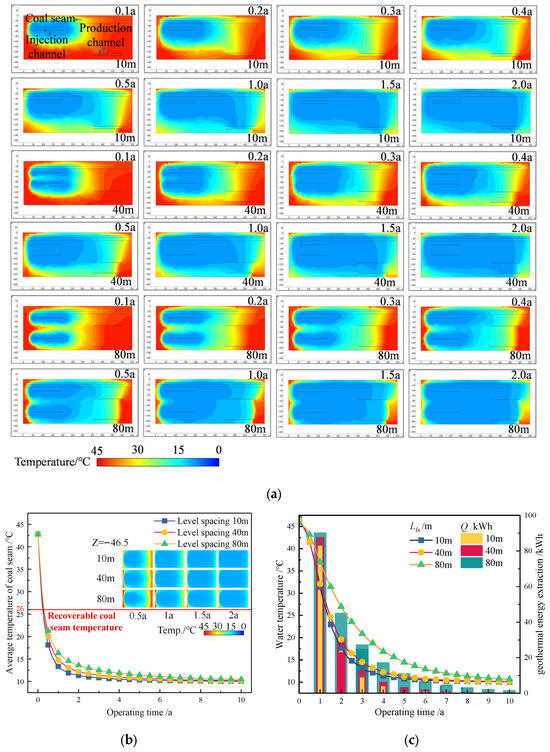

The influence patterns of different level spacings (The water injection pressure is set to 6 MPa, and the water injection temperature is 10 °C for all cases) on the cooling effectiveness and heat extraction efficiency of the deep coal mine aquifer geothermal energy extraction and coal seam cooling system are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Influence patterns under different level spacing conditions: (a) Temperature contours on the X-Z cross-section (at the middle of the model) within the study area; (b) Average coal seam temperature curve and temperature contours on the central cross-section; (c) Extracted water temperature curve and histogram of geothermal energy extraction.

As shown in Figure 6a, the differences in cooling effectiveness within the study area under varying level spacings are primarily evident during the early stages of operation. The distribution of the cooling range in the aquifer shows clearer distinctions in the initial phase, which later converge to become roughly similar. A larger level spacing corresponds to a longer time required for thermal breakthrough between injection channels. In the early stage, the overall cooling extent within the aquifer does not differ significantly across spacing scenarios. When the level spacing is 10 m, the flow field is initially dominated by horizontal movement; after spreading near the production channel, it exhibits a clear tendency for vertical diffusion. As the level spacing increases, the flow behavior changes: the two-stage injection channels tend to converge vertically before migrating laterally. At a spacing of 80 m, the aquifer exhibits the widest cooling coverage during the initial injection period. After two years of operation, the average aquifer temperatures under level spacings of 10 m, 40 m, and 80 m are 11.45 °C, 12.02 °C, and 13.42 °C, respectively.

As shown in Figure 6b: The cooling rate of the coal seam decreases with increasing level spacing, whereas the cooling range expands. After two years of model operation, the temperature reductions in the coal seam under level spacings of 10 m, 40 m, and 80 m are 31.51 °C, 30.61 °C, and 29.23 °C, respectively, showing relatively similar magnitudes. The maximum temperature difference among the different schemes is only 2.28 °C. A larger level spacing results in a slightly narrower effective cooling range for the coal seam, though the overall difference is not substantial. As the level spacing increases, injection activities in the upper-level interfere with those in the lower level, impeding the upward flow velocity of the lower-level water. Consequently, less cold water diffuses upward into the coal seam, leading to a relatively weaker cooling effect. Although the rate of decrease in the average coal seam temperature slows down with greater level spacing, the overall difference remains minor. The time required to lower the temperature to 26 °C is 0.3 years, 0.3 years, and 0.4 years, respectively.

As shown in Figure 6c: The temperature of the extracted water decreases as the level spacing increases, while the geothermal energy extraction rate increases with larger level spacing and declines annually with extended model operation time. After 10 years of operation under different level spacing schemes, the final extracted temperatures are 10.07 °C, 10.11 °C, and 10.64 °C, respectively, with minimal overall differences—the temperature variations among the schemes range between 0.04 °C and 0.57 °C. The average geothermal energy extraction rates under different level spacings are 12.51 kWh, 14.59 kWh, and 21.00 kWh, respectively. At a level spacing of 80 m, the interference effects between the two levels are reduced, allowing each level to perform its water injection and extraction functions more efficiently. This leads to an increased production flow rate, resulting in higher heat extraction power, which remains superior to other schemes throughout the operational period. The cumulative heat extracted over 10 years reaches 210.03 KWH.

In summary, the differences in cooling performance under different level spacings are primarily concentrated in the early stage of model operation, while the cooling extent in the aquifer becomes largely similar in the later phase. As the level spacing increases, the time required for thermal breakthrough between injection channels lengthens, resulting in a slower coal seam cooling rate and lower extracted water temperature. Larger spacing induces interference between injection activities at upper and lower levels, hindering the upward diffusion of the lower-level water flow and thereby reducing the amount of cold water entering the coal seam, thus weakening the cooling effect on the coal seam. The geothermal energy extraction rate increases significantly with larger level spacing and generally declines year by year over the operational period. At a spacing of 80 m, due to reduced interference between the two levels, both levels achieve higher water injection and extraction efficiency, leading to a greater production flow rate. After 10 years of operation, the cumulative geothermal energy extraction reaches 210.03 kWh, and its extraction rate remains higher than that of other schemes throughout the entire operational period.

3.4. Discussion

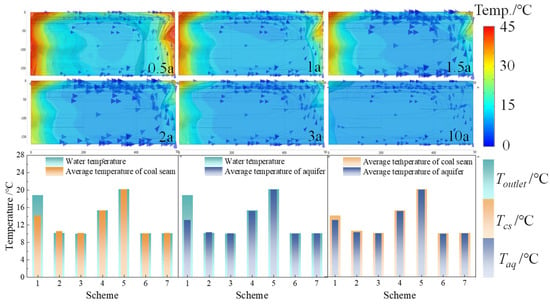

Based on the above analysis, the optimal parameter set for the dual-stage, single-branch system is determined as follows: a water injection pressure of 10 MPa, a water injection temperature of 10 °C, and a level spacing of 80 m (Scheme 3). The 10-year cooling performance and heat extraction efficiency achieved with this optimal configuration, along with comparative results, are presented in Figure 7 below.

Figure 7.

Temperature evolution contours over 10 years for the optimal parameter set and performance comparison histograms for different schemes.

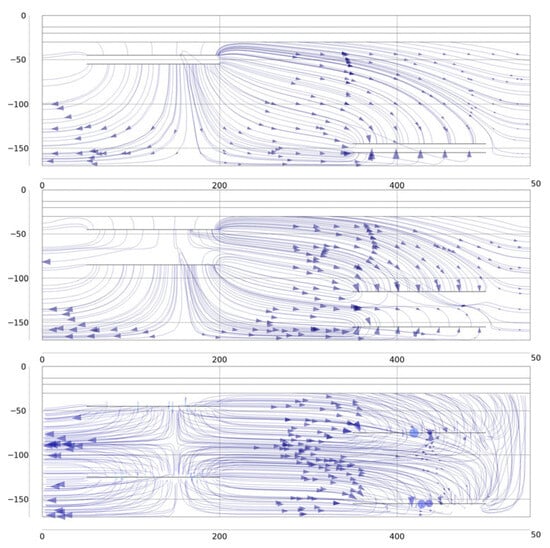

Based on the above analysis, the performance of the optimal parameter set (Scheme 3) is comparable to that of Scheme 6. This is further corroborated by the Darcy velocity field distribution within the aquifer, as illustrated in Figure 8. The injection and production channels are positioned 15 m from the upper and lower boundaries of the aquifer, respectively. In all three scenarios, the Darcy velocity field within the aquifer is generally directed from the injection channels toward the production channels. At a spacing of 10 m, the close proximity of the two levels leads to a superimposed flow effect. Conversely, with a 40 m spacing, flow interference occurs between the two levels, resulting in a more horizontally oriented velocity field. When the level spacing is increased to 80 m, interference between the levels is minimized, and the velocity field displays a distinct layered pattern. Moreover, a dual inlet–outlet flow structure is evident: flow paths originating from the upper injection channel predominantly converge into the upper production channel, while those from the lower injection channel mainly feed into the lower production channel. Therefore, the effective implementation of the proposed synergistic approach for mine thermal hazard control and geothermal energy extraction hinges on an appropriate selection of injection parameters. Subsequently, the channel layout can be tailored according to site-specific mine conditions. The proposed implementation workflow begins with modeling single-branch channels based on the actual geological strata to determine the optimal injection parameters and a safe level spacing. The required number of branches is then derived from the ratio of the actual working face width to the effective cooling width of the coal seam under the optimal scheme, thereby ensuring comprehensive areal cooling. It should be noted that the spatial scope of the present study is 550 m in length. For large-scale deployment of the synergistic thermal hazard control and geothermal energy extraction system, multiple sets of injection and production wells can be designed.

Figure 8.

Characteristics of the Darcy velocity field in the aquifer under different level spacings.

4. Conclusions and Outlook

4.1. Conclusions

To address the practical challenges of controlling high-temperature hazards in mine roadways and co-exploiting geothermal energy in deep coal mines, this study proposes a novel geothermal energy extraction and coal seam cooling system utilizing deep mine aquifers. A three-dimensional, dual-level, single-branch heat-transfer model of the system was developed to elucidate the effects of key operational parameters on cooling performance and heat-extraction efficiency. Based on the findings, a synergistic methodology for combined thermal-hazard control and geothermal energy extraction adaptable to various mining conditions was formulated. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- Increasing the injection pressure enhances the cooling effect, coverage, and rate both in the aquifer and the coal seam. Once the water reaches the floor strata, it redirects and spreads laterally along the coal seam strike. After 10 years of operation, the final average temperatures of the coal seam under injection pressures of 3, 6, and 10 MPa were 14.14 °C, 10.62 °C, and 10.15 °C, respectively. The temperature of the produced water decreases over time, with a more pronounced drop observed at higher pressures. During the first year, the geothermal energy extraction rate increases with pressure. Beyond the sixth year, however, the heat extraction power in high-pressure scenarios declines as the produced water temperature approaches the injection temperature, eventually falling below that of the low-pressure case. This demonstrates the distinct applicability of different operational strategies: high pressure is favorable for short-term efficient heat extraction, while low pressure is more suitable for long-term stable recovery.

- (2)

- Higher injection temperatures reduce both the cooling range and rate within the aquifer and the coal seam. This reduction is attributed not to changes in the flow field direction or coolant propagation speed, but to a diminished thermal gradient between the injected water and the rock matrix, which lowers the heat flux and cooling efficiency. After two years, the average aquifer temperature decreased by 31.90 °C, 27.63 °C, and 23.23 °C for injection temperatures of 10 °C, 15 °C, and 20 °C, respectively. The time required to cool the coal seam below 26 °C increased from 0.3 years to 0.6 years as the injection temperature rose. Concurrently, the temperature of the produced water increased with higher injection temperature, while the geothermal energy extraction rate decreased annually, influenced by both the elevated injection temperature and the extended operational duration. Therefore, in practice, the injection temperature should be minimized to the lowest feasible level while still meeting the requirements for geothermal utilization.

- (3)

- The influence of level spacing on cooling performance is most pronounced during the early operational stage, with the cooling extents in the aquifer converging in later phases. Larger spacings prolong the time to thermal breakthrough between injection channels, slowing the coal seam cooling rate and lowering the temperature of the produced water. Excessive spacing can also cause interference between injection flows from upper and lower levels, impeding the upward migration of cooler water and reducing the volume reaching the coal seam, thereby weakening the overall cooling effect. In contrast, geothermal energy extraction increases significantly with larger spacing, although a general declining trend is observed over time. At an 80 m spacing, inter-level interference is minimized, allowing both injection and production operations to achieve higher efficiency and flow rates. After 10 years, the cumulative geothermal energy extraction reached 210.03 kWh, with its extraction rate consistently outperforming other configurations throughout the operational period.

- (4)

- Considering the influence patterns of all parameters, the optimal combination was determined to be an injection pressure of 10 MPa, an injection temperature of 10 °C, and a level spacing of 80 m. Under this optimal parameter set, the system’s cooling performance and geothermal energy extraction efficiency demonstrate significant improvement compared to other schemes. Consequently, a synergistic method for mine thermal hazard control and geothermal energy extraction has been established. First, appropriate injection parameter combinations are determined using simplified models based on the actual geothermal–geological conditions of the mine. Second, the layout of the flow channels can be tailored according to the specific on-site conditions. Finally, for larger-scale deployment of this synergistic system, multiple groups of injection and production wells can be designed.

4.2. Outlook

Based on the parametric laws revealed in this study, several important directions for future research are recommended:

- (1)

- Optimization of asymmetric well layouts: Examining configurations with differing level spacing or branch density between the injection zone and the production zone, to further enhance localized cooling intensity or thermal recovery efficiency.

- (2)

- Optimization of dynamic operational strategies: Developing and evaluating time-dependent injection–production schemes (e.g., dynamic adjustments of pressure and temperature parameters), tailoring operations to the shifting priorities from pre-mining rapid coal seam cooling to post-mining efficient long-term geothermal energy extraction.

- (3)

- Integration with complex geological conditions and THM coupling: Extending the model to incorporate heterogeneous aquifers, natural fracture networks, and fully coupled thermo-hydro-mechanical processes, in order to evaluate long-term reservoir performance and geomechanical stability under realistic field conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S. and H.A.; methodology, Y.S. and H.A.; software, X.L.; validation, Y.S., H.A. and X.L.; formal analysis, Y.S., H.A. and X.L.; investigation, H.A. and X.L.; resources, H.A. and X.L.; data curation, Y.S., H.A. and X.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.S., H.A. and X.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.S., H.A. and X.L.; visualization, Y.S., H.A. and X.L.; supervision, Y.S.; project administration, Y.S.; funding acquisition, Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by the Key Research and Development Program of Shaanxi (Program No. 2024PT-ZCK-70), Science and Technology Innovation Fund Project of China Coal Science and Technology Xi’an Research Institute (Group) Co., Ltd. (2023XAYJS21), and Science and Technology Innovation and Entrepreneurship Fund Special Project of Tiandi Science and Technology Co., Ltd. (2023-2-TD-ZD021).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Hongtao An was employed by Xi’an Coal Technology Geothermal Energy Development Co., Ltd. Author Yuliang Sun was employed by CCTEG Xi’an Research Institute (Group) Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HM | Hydraulic-Mechanical |

| SVCR | Split-Type Vapor Compression Refrigeration |

| THM | Thermal-Hydraulic-Mechanical |

| RG | Rock–Geothermal model |

| RP | Rock–Porous model |

| GP | Geothermal–Porous model |

References

- Chen, W. Going Deep: Safe Development and Utilization of Coal Resources Shifts to Subsurface Kilometers. China Strateg. Emerg. Ind. 2025, 28, 55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.P.; Zhou, H.W.; Xue, J.D.; Wang, H.W.; Zhang, R.; Gao, F. Research and consideration on deep coal mining and critical mining depth. J. China Coal Soc. 2012, 37, 535–542. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.X.; Wang, J.Y.; Zhou, N.; Kong, X.L.; Zhu, C.L.; Liu, H.F. Collaborative mining system of geothermal energy and coal resources in deep mines. Chin. J. Eng. 2022, 44, 1682–1693. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, G.X. Critical Challenges and Solutions for Deep Coal Mining Technology. Inn. Mong. Coal Econ. 2025, 16, 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.P.; Zhang, H.; Jian, C.G. Study on Mine Cooling Technique Based on Low Temperature Water Spray in Mine Ventilation Shaft. Coal Sci. Technol. 2012, 40, 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.X.; Li, G.D.; Chang, D.Q.; Li, Y.H. Present Situation and Prospect of Mine Geothermal Hazard Control Technology. Met. Mine 2023, 7, 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L. Research on Thermal Hazard Mitigation Technology in Coal Mines. Inn. Mong. Coal Econ. 2021, 10, 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.C.; Liu, F.; Liu, Q.J.; Xu, Y.J.; Li, D. Engineering practice of ground centralized cooling for Shoushan No. 1 Mine. Coal Eng. 2020, 52, 94–97. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Yang, L. Research and Review on Deep Mining Cooling. Coal Technol. 2016, 35, 152–154. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.F.; Li, M.G. Analysis of Coal Mine Thermal Hazard Mitigation Strategies: A Comparison of Active and Passive Cooling Methods. In Proceedings of the 6th Member Congress & Coal Mine Geothermal Prevention Academic Forum of Shandong Coal Society, Tengzhou, China, 22 April 2013; pp. 87–89. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D.J. Abandoned coal mine geothermal for future wide scale heat networks. Fuel 2017, 189, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, R.; Zhang, W.; Pan, Z. Numerical simulation of mine heat hazard governance and geothermal resource exploitation using extraction-ventilation collaborative method. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.H.; MA, D.; GAO, X.F.; Li, Q.; Hou, W.T. Fault zone mechanical response under co-exploitation of mine and geothermal energy: The combined effect of pore pressure and mining-induced stress. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2025, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liang, S.; Liu, J. Proposed split-type vapor compression refrigerator for heat hazard control in deep mines. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 105, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.B.; Tu, S.H.; Liu, X.; Ma, J.Y.; Tang, L. Study of energy-efficient heat resistance and cooling technology for high temperature working face with multiple heat sources in deep mine. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2023, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Guo, P.Y.; Fang, C.; Bu, M.H.; Jin, X.; Wang, J. Investigation of evaluation models for geothermal resources and intermittent operation/cycle thermal storage mode in closed coal mines. Geothermics 2025, 129, 103294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Z.; Yu, K.; Wan, Z.; Ju, Y.; Yu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Shi, P.; Sun, Z.; Lv, J. Geothermal energy accumulation mechanism and development mode in a deep mine: A case study. Geothermics 2026, 134, 103502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez, J.; Ordónez, A.; Fernández-Oro, J.M.; Loredo, J.; Díaz-Aguado, M.A. Feasibility analysis of using mine water from abandoned coal mines in Spain for heating and cooling of buildings. Renew. Energy 2020, 146, 1166–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Tang, J.; Hu, Z.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, K.; Kang, S.; He, X. Potential Evaluation of Cross-Seasonal Heat Storage of Coal Mine Underground Reservoir: A Case Study Based on Multiphysics Coupling Numerical Simulation Method. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbelová, H.; Spisto, A.; Giaccaria, S. Regional Energy Transition: An Analytical Approach Applied to the Slovakian Coal Region. Energies 2020, 14, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.Y.; Zhang, J.X.; Yan, H.; Zhou, N.; Li, M.; Liu, H.F. Numerical investigation into the effects of geologic layering on energy performances of thermal energy storage in underground mines. Geothermics 2022, 102, 102403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.H.; Ma, D.; Gao, X.F.; Duan, H.Y.; Li, Q.; Hou, W.T. Geothermal energy production potential of karst geothermal reservoir considering mining-induced stress. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2025, 35, 1153–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Xiong, L.; Ma, J.; Yu, K.; Cui, W.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, Z. Mechanism of Floor Failure During Coordinated and Sustainable Extraction of Coal and Geothermal Resources in Deep Mines: A Case Study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, M.S.; Rezaei, A.; Soliman, M.Y.; Farouq Ali, S.M. Thermo-Poroelastic Analysis of Cold Fluid Injection in Geothermal Reservoirs for Heat Extraction Sustainability. In Proceedings of the 56th U.S. Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium, Santa Fe, NM, USA, 26–29 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Li, Y.Y.; Zheng, H.; Fan, B.H. A Novel Fully Coupled Thermo-Hydro-Mechanical-Damage Model for Hydraulic Fracture Propagation in Fractured Geothermal Reservoirs. SSRN 2025, 185, 107364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, T.; Xie, Z.; Huang, Z.; Li, G.; Song, X.; Wu, X.; Li, J.; Yang, R.; Zou, W.; Sun, Z. Hydraulic fracturing of naturally fractured hot dry rock based on a coupled thermo-hydro-mechanical model. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2026, 257, 214163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, P.; Peng, J.; Xian, H.Y. Insight into the investigation of heat extraction performance affected by natural fractures in enhanced geothermal system (EGS) with THM multiphysical field model. Renew. Energy 2024, 231, 121030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.L.; Li, Z.J.; Xu, Y.; Zheng, G.G.; Qin, X.L. Integrating geothermal extraction with mine heat hazard control: A thermal–hydraulic–mechanical-ventilation coupling model for deep mines. Energy 2026, 342, 139608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Huang, H.; Guo, L.; Cao, Y.; Hu, Y.; Cui, S.; Wu, B.; Kang, F.; Zhang, L.; Shi, M.; et al. Influence of discrete fracture network on the performance of enhanced geothermal system considering thermal-hydraulic-mechanical multi-physical field coupling. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0320015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.J.; Ding, X. Calculation of geothermal resources based on parameter identification-a case study from the western slope of the Yinchuan plain. Acta Geol. Sin. 2020, 94, 2131–2138. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, T.; Fan, M.; Ren, Z.Q.; Zhang, H.M.; Tian, G.L. Evaluation study on geothermal resources in deep part of Panji mining area based on grey sequence method. Coal Technol. 2017, 36, 153–156. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, B.Q.; Pang, Z.H.; Kong, Y.L.; Gong, Y.L. Exploration and Amount Fine Evaluation of Geothermal Resources Based on Microtremor Survey Method. Sci. Technol. Dev. 2020, 16, 367–374. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.J.; Li, F.; Yan, J.H.; Hu, J.W.; Wang, H.K.; Ren, H.T. Evaluation methods and application of geothermal resources in oilfields. Acta Pet. Sin. 2020, 41, 553–564. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, H.; Xu, C.; Wu, H.; Zheng, Z.; Sun, X.; Wang, H.; Chai, J.; Li, Y. Research on the testing of ground temperature parameters in the middle and deep mines of the Mengshan mining area. China Coal 2017, 43, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.