Featured Application

The ML Ontology presented in this article is the information backbone of a data science platform used for training machine learning models from datasets. Features include a training configuration wizard and interactive help.

Abstract

This article presents an industry-ready ontology for the machine learning domain, which is named “ML Ontology”. While based on lightweight modelling languages, ML ontology provides novel features including built-in queries and quality assurance, as well as sophisticated reasoning. With ca. 700 individuals that define key ML concepts and ca. 5000 RDF triples, ML Ontology ranks among the largest domain-specific ontologies for ML. An experiment to estimate the correctness and completeness of ML terminology included in ML Ontology indicates an F1-score of 0.83. A benchmark evaluating query performance reveals query response times far below 100 ms even for complex queries and memory consumption below 3.5 MB. Its industry-readiness is demonstrated by benchmarks as well as two use case implementations within a data science platform. ML Ontology is open source and published under an MIT license.

1. Introduction

Why still work on ontologies while generative artificial intelligence (AI), in particular large language models (LLM) today allow solving problems for which ontologies have been used traditionally? The reason is that there are still numerous use cases, also in industry, in which the explicit specification of concepts and their relationships are most useful. Ontologies [1] serve exactly this purpose. Many ontologies have been developed for the life sciences domain, e.g., Gene Ontology (GO) (https://geneontology.org), SNOMED CT (https://www.snomed.org) and MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) (https://meshb.nlm.nih.gov) (all weblinks accessed on 6 January 2026). However, in the AI domain and the field of ML in particular, there are only a handful of ontologies available (e.g., [2,3,4,5]). In this article, an ontology for the ML field is presented which is named ML Ontology. ML Ontology is based on existing work and expands on the following aspects:

- 1.

- Volume: ML Ontology, together with OntoDM, ranks among the most comprehensive ontologies for the domain of ML with respect to the number of ML concepts and relationships modelled.

- 2.

- Performance: ML Ontology allows high-performance query access suitable for industry applications.

- 3.

- Balance between simplicity and expressiveness: ML Ontology is based on simple technology particularly suited for industry use, while at the same time offers expressive power, including sophisticated reasoning where needed.

- 4.

- Extensibility and adaptability: ML Ontology is modularised and can be easily extended and adapted to differing use cases.

- 5.

- Built-in quality management: ML Ontology comprises built-in quality checks that can be adapted use-case-specifically in order to ensure quality requirements from industry.

- 6.

- Standards: ML Ontology is solely based on Semantic Web (SW) (https://www.w3.org) standards like RDF (https://www.w3.org/RDF), RDFS (https://www.w3.org/TR/rdf-schema) and SPARQL (https://www.w3.org/TR/sparql11-overview) and may also well be deployed using industry-ready Labeled Property Graph (LPG) databases like Neo4j (https://neo4j.com).

- 7.

- Public availability: ML Ontology is published open source (https://github.com/hochschule-darmstadt/MetaAutoML/blob/main/controller/managers/ontology/ML_Ontology.ttl) under an MIT license.

Many of those properties are crucial for using ontologies in industry applications, including sufficient volume, performance, expressiveness, extensibility and adaptability, quality and conformance to standards. In this article, the term industry-ready is used for ontologies that exhibit those properties.

ML Ontology has been developed over a period of more than five years by more than 15 different knowledge engineers with knowledge in the ML field. In the current version it consists of ca. 5000 RDF triples. The following two use cases use ML Ontology, and demonstrate its industry readiness:

- 1.

- Configuration wizard: ML Ontology serves as the information backbone for a data science platform. Its usage in the configuration wizard for expert configurations of ML training runs is demonstrated.

- 2.

- Interactive help: ML Ontology is used as the information source for the interactive help system of the data science platform, helping users understand complex terminology in machine learning.

The main contribution of this article is an industry-ready ontology for the ML field, which expands on previous work with built-in quality management and a balance between simplicity and expressiveness, leading to extensibility, adaptability and high-performance access.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. Section 2 references related work. Section 3 explains the methodology used for developing ML Ontology. Section 4 is the core of this article and outlines the architecture of ML Ontology. In Section 5, two use cases are introduced which demonstrate successful application of ML ontology. Section 6 discusses findings and Section 7 concludes this article.

2. Related Work

2.1. Definitions and Semantic Web Standards for Ontologies

A commonly cited definition of ontology is “an explicit specification of a conceptualisation” by Gruber [1]. Gruber furthermore explains conceptualisation as “the objects, concepts, and other entities that are presumed to exist in some area of interest and the relationships that hold them”. This definition is broad enough to include formal upper-level ontologies but also knowledge graphs, thesauri and other forms of knowledge representation.

The world-wide web consortium (W3C) (https://www.w3.org) has standardised modelling languages for ontologies under the Semantic Web (SW) umbrella. RDF (Resource Description Framework) allows specifying structured information as subject–predicate–object triples in a machine-readable and interoperable way. RDFS (RDF Schema) is an extension of RDF that provides basic vocabulary for defining classes, properties, and relationships to build simple ontologies. OWL (Web Ontology Language) (https://www.w3.org/TR/owl-features) is a powerful ontology language built on RDF/RDFS that allows for rich, logic-based modelling of complex relationships and constraints between concepts. SPARQL (SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language) is a query language designed to retrieve and manipulate data stored in RDF format, similar in syntax to SQL but tailored for graph-based data.

W3C’s standardisation efforts have spawned the definition of numerous widely-accepted ontology schemas. SKOS (Simple Knowledge Organization System) (https://www.w3.org/2004/02/skos) is a W3C standard that provides a lightweight RDF-based framework for representing controlled vocabularies like thesauri, taxonomies, and classification schemes. SHACL (Shapes Constraint Language) (https://www.w3.org/TR/shacl) is a W3C recommendation for validating RDF graphs against a set of conditions to ensure data integrity and consistency.

2.2. Labeled Property Graphs and GQL

Labeled Property Graphs (LPG) [6] are also graph-based data models like RDF/RDFS. One prominent LPG database system is Neo4j, which is widely used in industrial practice. GQL (Graph Query Language) (https://www.gqlstandards.org) is a standardisation effort by ISO (International Organization for Standardization) (https://www.iso.org), which is gradually being adopted by graph database systems such as Neo4j.

2.3. Lightweight vs. Heavyweight Ontologies

The term knowledge graph has been used in recent years (Although the term knowledge graph has been already used since 1972, the current use of the phrase stems from the 2012 announcement of the Google Knowledge Graph [7]). For example, Google Knowledge Graph uses simple standardised schemas like Schema.org (https://schema.org). Schema.org specifies a limited number of classes (currently about 800) such as persons, organisations, locations, products, events, etc. Simple standardised modelling languages including RDFa, Microdata and JSON-LD may be used to specify concrete entities. ML Ontology can be categorised as a knowledge graph.

In own previous work [8] we discuss various flavours of ontologies that can be subsumed under Gruber’s definition referring to them as lightweight versus heavy-weight. We consider knowledge graphs as lightweight since simple modelling languages and schemas are used. Lightweight ontologies are relatively easy to use and are used frequently in industry practice, e.g., by all major internet search engine providers and tech companies, including Google, Amazon, eBay, Facebook, IBM, LinkedIn and Microsoft [7].

In contrast, heavy-weight ontologies use modelling languages with much higher semantic expressiveness, such as OWL (https://www.w3.org/TR/owl-features) or F-logic [9]. Such ontology modelling languages allow knowledge engineers to express reasoning, logical operators, quantifiers, etc.

The architecture of ML Ontology is based on own previous work [10] which presents an extensible approach to multi-level ontology modelling. In particular, a lightweight mechanism for using inferencing in an extensible and use-case-specific way is presented. This lightweight approach is also employed for ML Ontology to balance simplicity and expressiveness.

2.4. Ontologies for Machine Learning and External Knowledge Graph Alignment

There are relatively few ontologies for the ML domain that are published, maintained and publicly available. ML Schema (https://ml-schema.github.io/documentation) [2] has been developed by the W3C Machine Learning Schema Community Group. It is a top-level ontology for describing ML algorithms, datasets, models, and experiments. It has been used for mapping OntoDM, DMOP, Exposé and MEX Vocabulary. ML Ontology is also linked to ML-Schema. OntoDM-core [3] is a comprehensive ontology for data mining and ML, aligned with top-level ontologies such as BFO and OBI. In contrast to ML Ontology, OntoDM-core focusses on ML experiments. DMOP (Data Mining OPtimization Ontology) [4] provides representations of ML workflows, focussing on optimisation and meta-mining. DMOP does not seem to be publicly available. Exposé Ontology [5] is used to describe and reason about ML experiments. It does not seem to be publicly available. MEX Vocabulary (https://github.com/mexplatform/mex-vocabulary/tree/master) [4] is a lightweight vocabulary for describing ML experiments and their configurations.

Wikidata (https://www.wikidata.org) is a large-scale, general-purpose knowledge graph. It is the information backbone of Wikipedia and serves as a central source of open data. Wikidata also includes numerous entries for the ML domain. ML Ontology links ML concepts to Wikidata.

2.5. MLOps and Metadata Management

Modern MLOps platforms provide comprehensive facilities for experiment tracking, artifact management, lineage capture, and model governance. MLflow (https://mlflow.org) offers tracking of parameters, metrics, artifacts, and models, backed by file or relational stores with tool-specific schemas and REST APIs designed for operational integration. Kubeflow Pipelines builds on TensorFlow Extended (TFX) to orchestrate end-to-end ML workflows; its ML Metadata (MLMD) component captures executions, artifacts, and contexts to support reproducibility [11]. These systems support lifecycle management within their respective ecosystems.

However, their metadata models are largely non-semantic: the meaning of fields is implicit in tool-specific identifiers and JSON/protobuf schemas, and interoperability is commonly achieved via bespoke adapters or import/export conventions. They typically do not provide a formally shared, machine-interpretable domain vocabulary for ML concepts (e.g., ML areas, tasks, approaches, metrics) that can be reused across heterogeneous libraries and AutoML solutions.

It is important to distinguish the scope of ML Ontology from prior ontologies focused on experiment annotation and meta-mining (ML Schema Core Specification [2], DMOP [4], Exposé [5], MEX Vocabulary). Likewise, operational MLOps tools such as MLflow and Kubeflow target the process and artifact metadata of ML experiments. The goal of ML Ontology is not to annotate ML experiments or formalize MLOps; instead, it targets interoperability of various ML implementations when used together in one use case scenario. Specifically, ML Ontology harmonizes terminology for ML tasks, approaches, metrics, libraries, AutoML solutions, and configuration items, enabling cross-library alignment and user-facing assistance (cf. the configuration wizard and interactive help in Section 5).

3. Methodology

The construction of ML Ontology was carried out following the METHONTOLOGY framework [12,13], which is a well-established methodology for ontology development that provides a structured approach to the specification, conceptualization, formalization, and implementation of ontologies. The process ensures methodological rigor and traceability across all stages of development.

3.1. Specification

The initial step involves defining the purpose, scope, and intended use of the ontology. ML Ontology was designed to provide common vocabulary for ML concepts and their relationships to support applications that integrate different ML tools and frameworks. Competence questions were formulated to guide the ontology’s coverage and ensure alignment with user requirements. Examples include:

- What are the main categories of machine learning algorithms (e.g., supervised, unsupervised, reinforcement)?

- Which ML approaches are suitable for classification tasks (e.g., decision trees)?

- What are the common evaluation metrics used for regression models (e.g., mean squared error)?

- Which ML libraries support regression (e.g., scikit-learn)?

Domain experts from academia and industry were consulted in form of workshops to validate the scope and relevance.

3.2. Conceptualization and Formalization

In this phase, the knowledge gathered during specification was structured into a conceptual model. Key concepts, relationships, and attributes relevant to machine learning were identified. This included classes such as ML area, ML task, ML approach, Metric, ML library etc., along with their properties and interrelations. A glossary of terms was created to ensure consistency and avoid ambiguity. Hierarchical taxonomies and semantic relations were drafted to represent the domain knowledge. A shared spreadsheet was used to collaboratively define and refine the conceptual model.

As a step towards formalization, the modeling approach was defined. To ensure industry readiness, ML ontology uses a lightweight modelling approach and is implemented as a knowledge graph. The modelling language used is RDF/RDFS. ML Ontology includes limited number of RDFS classes (ca. 10) and a large number of instances (ca. 700) representing ML concepts. Some SKOS properties like skos:prefLabel, skos:altLabel or skos:broader are used for attributes and relationships. SPARQL is used as query language and SPARQL Update for reasoning; SHACL is used for quality assurance.

3.3. Implementation and Evaluation

ML Ontology was implemented manually in a series of iterative cycles by ML experts and knowledge engineers. Naming conventions on IRIs were defined to ensure consistency. They are based on preferred labels of instances, e.g., support_vector_machine for the instance with preferred label “support vector machine”. A toolchain including shared spreadsheets, an RDF generator (https://github.com/hochschule-darmstadt/RDFGenerator) and a GitHub repository for version control was used.

Evaluation and quality assurance were performed in various ways. As part of a committer workflow, a single reviewer with domain expertise reviewed all changes before merging them into the main branch. In addition, automated quality assurance checks were implemented as part of the ontology and executed regularly. Finally, competency questions defined during specification were used to validate the ontology’s coverage and correctness.

4. Results

4.1. ML Ontology Schema

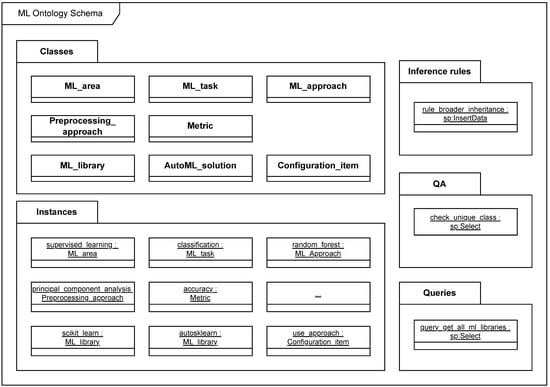

Figure 1 shows the schema of ML Ontology as a UML diagram (https://www.omg.org/spec/UML). ML Ontology consists of four modules:

Figure 1.

ML Ontology schema.

- Classes: Definition of all classes and properties to be used in the ontology;

- Instances: Instances of the specified classes with all their properties that model ML concepts and their relationships;

- Inference rules: Forward-chaining inference rules may be applied in a use-case-specific manner to enhance the expressiveness of the ontology;

- QA: Quality assurance (QA) checks can be used in a use-case-specific manner to ensure integrity of the ontology;

- Queries: Sample queries that may be used in applications utilising the ontology.

The main classes of ML Ontology are as follows.

- ML_area with instances for supervised learning, unsupervised learning and reinforcement learning;

- ML_task with ca. 40 instances, e.g., for classification, regression, and clustering;

- ML_approach with ca. 120 instances, e.g., for artificial neural network, random forest, and support vector machine;

- Preprocessing_approach with ca. 10 instances, e.g., for principal component analysis and kernel approximation;

- Metric with ca. 120 instances, e.g., for accuracy, f-measure and mean squared error;

- ML_library with ca. 30 instances, e.g., for Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, and PyTorch;

- AutoML_solution with ca. 30 instances, e.g., for AutoSklearn, TPOT, and Auto-PyTorch;

- Configuration_item with ca. 240 instances, e.g., for ensemble size, use approach, and metric.

In addition, there are ca. 15 predefined sample queries (e.g., get all dataset types), 5 quality assurance checks (e.g., check unique class) and one inference rule (broader inheritance). Classes and instances are explained in more detail in the following sections.

4.2. Ontology Classes

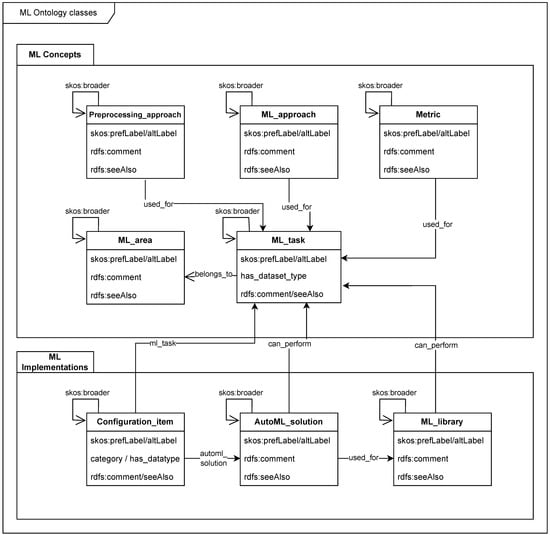

Figure 2 shows the main classes of ML Ontology as a UML diagram. The classes are organised in two modules:

Figure 2.

ML Ontology classes.

- ML concepts formalise terminology in the ML domain: concepts and their interdependencies;

- ML implementations specify ML libraries, AutoML solutions and their concrete configuration options.

Instances of all classes are specified by a set of common properties:

- skos:prefLabel: the preferred label of the individual, e.g., “support vector machine”. This label is used for the IRI of the individual, e.g., support_vector_machine;

- skos:altLabel: alternative labels or acronyms, e.g., “SVM”;

- rdfs:comment: short description of the individual, e.g., “Set of methods for supervised statistical learning”;

- rdfs:seeAlso: ontology linking, e.g., the Wikidata entry for support vector machine <https://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q282453>.

In addition, there are class-specific properties and properties that link instances of difference classes:

- used_for links ML approaches, preprocessing approaches and metrics to ML tasks they can be used for, e.g., the ML approach support vector machine can be used for ML tasks classification and regression.

- belongs_to links ML tasks to ML areas, e.g., the ML task classification belongs to the ML area supervised learning.

- can_perform links instances of ML library or AutoML solution to ML tasks, e.g., ML library scikit-learn can perform ML task classification.

- ml_task links configuration items to ML tasks.

- skos:broader is used for modelling taxonomies between instances of the same class, e.g., the broader term of tabular regression is regression.

4.3. Ontology Alignment

Ontology alignment allows identifying correspondences between concepts in different ontologies to enable semantic interoperability across heterogeneous data sources. It reduces ambiguity, enhances reusability of knowledge, and allows applications to make use of linked data.

In ML Ontology, classes have been aligned with concepts from the ML Schema Core Specification (Namespace <https://www.w3.org/ns/mls#>) and instances with Wikidata entries via rdfs:seeAlso. See Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Alignment between ML Ontology and ML Schema.

Table 2.

Alignment between ML Ontology and Wikidata.

Beyond name-level correspondences, we evaluate alignment with ML Schema along class intent, hierarchy organization, and data-level constraints:

- ML_task vs. mls:Task: Both denote problem descriptions in ML. ML Schema constrains tasks with mls:definedOn. ML Ontology models dataset-specific variants via has_dataset_type and taxonomies using skos:broader.

- ML_approach/Preprocessing_approach vs. mls:Algorithm: Both capture algorithmic families independent of implementation. ML Ontology distinguishes general ML approaches and preprocessing approaches; both can be projected to mls:Algorithm.

- ML_library/AutoML_solution vs. mls:Implementation: ML Schema requires implementations to mls:implements an mls:Algorithm and to expose hyperparameters and quality characteristics. In ML Ontology, implementations are linked to tasks and approaches via can_perform and configuration relations (e.g., use_approach). Hyperparameters are represented as Configuration_item with enumerations and broader alignment terms.

- Metric vs. mls:EvaluationMeasure: Both denote model assessment measures; ML Ontology’s Metric instances linked via used_for to tasks are comparable with mls:EvaluationMeasure.

4.4. Ontology Instances

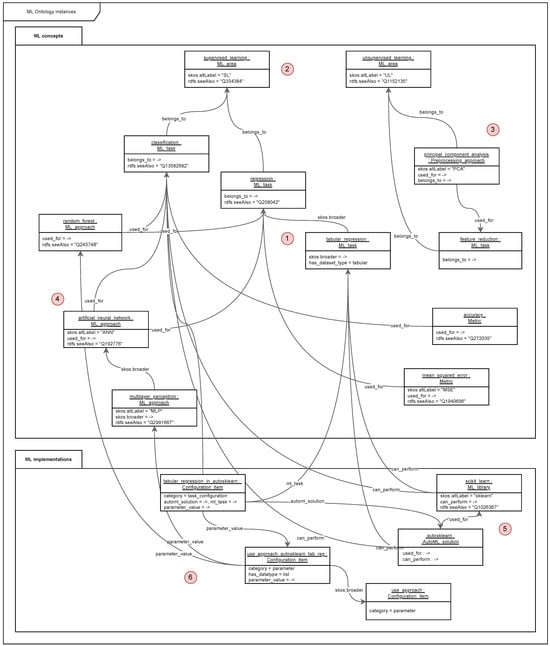

Figure 3 shows an example subset of ontology instances, their attributes and relationships as a UML diagram. RDF triples with their subject–predicate–object structure are oriented at natural languages. A triple in Turtle notation like

can be read as “The ML task regression belongs to the ML area supervised learning.” In the following, the various ML concepts depicted in Figure 3 are explained in order to illustrate the kind of knowledge being represented in ML Ontology. The areas explained are indicated with numbers in red circles, starting in the centre of the diagram.

|

Figure 3.

ML Ontology instances.

(1) ML task tabular regression is a specialisation of the concept regression, hence the broader relationship. The specified dataset type is tabular. tabular is an instance of the auxiliary class Enum (not depicted in Figure 2), which allows formalising categorised named vocabularies. In this case, the category is dataset type and instances are tabular, text, etc. Where there are Wikidata entries for respective concepts, there are links to respective entries, e.g., for regression the entry Q208042 (https://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q208042 (accessed on 6 January 2026)).

(2) The ML task regression belongs to ML area supervised learning (acronym “SL”, Wikidata ID Q334384). Another ML task belonging to supervised learning is classification. The metric accuracy can be used for classification and the metric mean squared error can be used for regression.

(3) An ML task belonging to ML area unsupervised learning is feature reduction, just like the preprocessing approach principal component analysis (PCA).

(4) The ML approaches random forest and artificial neural network (ANN) can both be used for ML tasks classification and regression. The ML approach multilayer perceptron (MLP) is a specialisation of artificial neural network, hence the broader relationship.

(5) Auto-Sklearn is an AutoML solution that can be used for generating ML models for ML library Scikit-learn. Both can perform ML tasks classification and regression.

(6) We show exemplary a configuration item tabular regression in autosklearn. It configures multiple parameter values, one of which is use approach for configuring the ML approaches that Auto-Sklearn supports (here random forest and artificial neural network). The broader term is use approach, necessary for aligning the parameter configurations between various AutoML solutions.

4.5. Ontology Queries

Traditionally, ontologies and queries are separated. Ontologies are published, e.g., as open data, whereas SPARQL queries are developed as part of applications using the data. However, we argue that ontologies and queries belong together because predicates and classes used in queries depend on their definitions in the ontology. Therefore, sample SPARQL queries are published as part of ML Ontology, providing application developers wishing to access ML Ontology a starting point for their implementation.

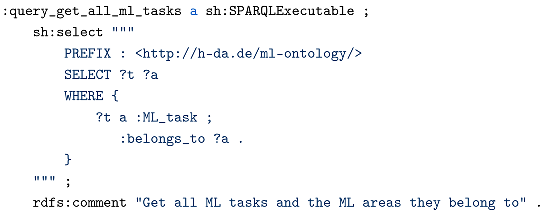

SHACL is employed for storing SPARQL sample queries within ML Ontology. Consider Listing 1 with statements for specifying a SPARQL query which gets all ML tasks and the respective ML areas they belong to, e.g., classification belongs to supervised learning.

| Listing 1: Sample ontology query. |

|

The class sh:SPARQLExecutable (Namespace <http://www.w3.org/ns/shacl#>) is instantiated and used with the property sh:select for specifying the SPARQL query.

4.6. Quality Assurance

Like many other ontologies, ML Ontology has been curated by a number of different knowledge engineers over a longer period of time. As in software development, architectural integrity is an important aspect in ontology development. In software development, regression testing is a standard approach for ensuring quality over development time. We consider the same to be applicable for ontology development. To operationalize built-in quality management, ML Ontology ships with a small but expressive base profile of declarative constraints that are evaluated as SPARQL checks embedded in the ontology. Each check is defined as a SPARQL SELECT query stored alongside the data (using SHACL/SPARQL executable forms) and interpreted with the conventional pass criterion “no results returned”; any bindings produced by a query represent concrete violations that can be reported or fixed. This design keeps the constraints versioned with the ontology and ensures that validation semantics co-evolve with the schema and instances.

From a software engineering perspective, embedding the checks in the ontology rather than in application code provides the following benefits: (i) single source of truth for invariants across heterogeneous consumers; (ii) portability and reproducibility of validation independent of specific stacks or runtimes; (iii) tight coupling of constraints with ontology versions enabling traceable evolution; and (iv) ease of automation in CI pipelines and data release processes without duplicating logic in multiple applications.

The current base profile groups checks into typing, vocabulary, and schema conformance. Table 3 summarizes the shipped checks and their intent.

Table 3.

Overview of built-in quality checks. Checks are encoded as SPARQL SELECT queries and pass if they return no results; profiling reports are informational.

Coverage. The typing checks ensure that all IRIs used as objects correspond to declared classes and that no individual is assigned multiple ML Ontology classes. The vocabulary check verifies that every predicate from the ontology namespace appearing in the data is explicitly declared as an rdf:Property. The schema-conformance check reports the observed subject and object classes for each predicate, enabling inspection of domain–range alignment and the detection of potential type inconsistencies. All checks are implemented as SPARQL SELECT queries and follow a “no results means compliance” convention.

Execution. In practice, the checks are executed automatically as part of ontology CI and release workflows and can be rerun on ingestion by consuming systems. Since each check is a pure query artifact stored with the ontology, validation is independent of a particular application and can be reproduced across RDF engines.

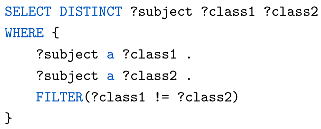

Example. Listing 2 shows a simple sample SPARQL query for check unique class.

| Listing 2: Sample check. |

|

The expected behaviour is that this query returns no results. However, if there are multiple class assignments for a subject, then those are listed in the result set. An example could be XGBoost which is the name of an ML approach as well as the name of an ML library. The query will return a row, if erroneously the same IRI had been used for both concepts, ML approach and ML class.

4.7. Reasoning

A lightweight approach for modelling ML Ontology has been chosen deliberately. However, some use cases may require sophisticated reasoning [14]. For this reason, a lightweight yet powerful reasoning mechanism is employed in ML Ontology, which has been proposed in own previous work [10].

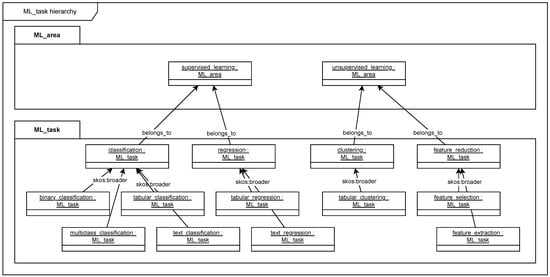

Consider the following example depicted in Figure 4. For ML tasks, various hierarchies have been specified. For example, classification may be refined according to the number of classes (binary classification, multiclass classification) or according to the dataset types (tabular classification, text classification, etc.). skos:broader has been chosen deliberately as a predicate with rather weak semantics to allow for various kinds of hierarchical groupings. The root of this hierarchy, the ML task classification, is specified as belonging to the ML area supervised learning. Logically speaking, one can state that if an ML task belongs to some ML area then all specific variants of this ML task belong to the same ML area, e.g., text classification belongs to supervised learning since classification belongs to supervised learning. In order to foster completeness of ML Ontology, one could add a quality check, ensuring that for all ML tasks, an ML area is assigned which it belongs to, forcing knowledge engineers to manually model all belongs to relationships. However, this is not only tedious but also introduces redundancy that should be avoided.

Figure 4.

ML task hierarchy.

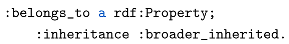

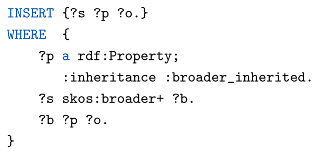

Another approach, which has been chosen, is to introduce use-case-specific reasoning to add correct belongs_to relationships even when they have not been modelled explicitly. Consider Listing 3 with a declaration of the property belongs_to.

| Listing 3: Declaration of the property belongs_to. |

|

Like all properties used as predicates in ML Ontology, belongs_to is declared as an RDF Property. In addition, the meta-property inheritance specifies its inheritance behaviour as broader inherited. Inheritance is a mechanism adopted in computer science, in particular in object-oriented programming, for propagating properties across hierarchical structures, enabling derived entities to access characteristics of their predecessors. Listing 4 shows a use-case-specific rule that implements such inheritance behaviour for properties that have been declared as broader inherited.

| Listing 4: Example rule. |

|

An INSERT statement from the SPARQL Update specification is used which allows inserting new triples into an ontology. This allows implementing production rules that can be used for forward chaining reasoning. In this rule, triples are selected of which predicate ?p is broader inherited. Then, triples ?b ?p ?o are selected, for which the subject ?b is in a direct or indirect broader relationship with an individual ?s. If those conditions are satisfied then a new triple ?s ?p ?o is inserted into the ontology.

For example, if the query variable ?p is bound to the predicate belongs to and ?b is bound to classification and ?s is bound to text classification, then the following RDF triple is added to the ontology.

|

This inference rule is stored as part of ML Ontology using the SHACL class sh:SPARQLRule. If reasoning is needed in some use case context then all inference rules need to be executed after loading ML Ontology into an RDF store and before executing queries. After this, a query for ML tasks that belongs to supervised learning will also return text classification even if this is not explicitly specified in the ontology.

Note that other predicates used in ML task (e.g., skos:prefLabel, has_dataset_type, etc.) do not have the meta-property broader inherited and therefore those values are not inherited along the broader hierarchy. So, the label for classification will not be inherited to text classification.

Another property which has been specified as broader inherited is used_for which is used in various classes (e.g., ML approach, preprocessing approach, metric) for linking those concepts to ML tasks they can be used for. Take the example of the ML approach multilayer perceptron (MLP) which is a specialisation of artificial neural network (ANN). ANN can be used for classification and regression. Therefore, by applying the above inference rule, MLP can also be used for classification and regression even if this has not been modelled explicitly. Another example is the preprocessing approach kernel principal component analysis which is a specialisation of principal component analysis (PCA). PCA can be used for feature reduction. Therefore, by applying the inference rule, kernel principal component analysis can also be used for feature reduction.

This mechanism allows use-case-specific reasoning to be implemented transparently and easily. Ontology modelling is still lightweight while the full expressive power of SPARQL may be used for specifying complex inference rules. From an operational standpoint, inferred triples are materialized using SPARQL Update at ontology release time—i.e., whenever ML Ontology is updated and re-deployed as an information backbone of an application—by computing the closure into a dedicated inferred graph that is dropped and recomputed on each release. This batch rematerialization avoids per-triple synchronization and data bloat, constrains growth via selective rules and forward chaining. Batch rematerialization has been chosen due to its simplicity and low cost at the present scale [15,16,17,18].

5. Application Use Cases

5.1. ML Training Configuration Wizard

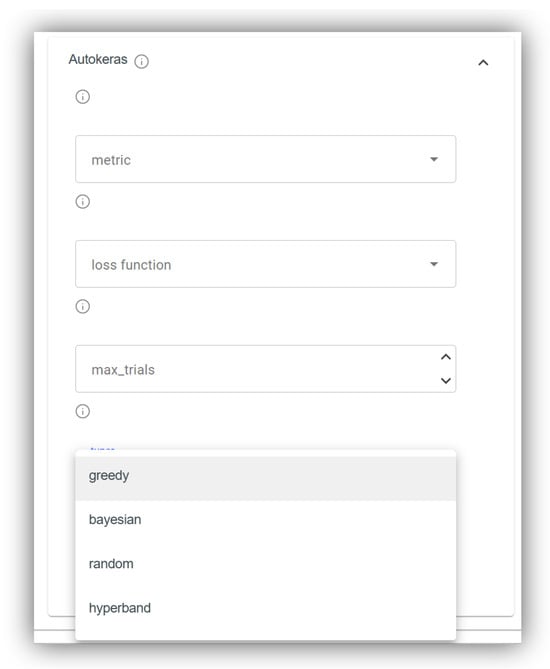

One of the primary applications of ontologies is the alignment of heterogeneous vocabularies within a given application domain. Here, a use case involving the configuration wizard of the data science platform OMA-ML [19] is presented. OMA-ML operationalises the concept of Meta-AutoML [20]. Meta-AutoML enables the automated generation of ML models for specific datasets by orchestrating multiple competing AutoML [21] implementations. While business domain experts (e.g., biologists) may want to provide minimal input to configure the training process, AI specialists can fine-tune the underlying parameters to optimise model performance. However, the configuration interfaces and terminologies used across different AutoML solutions vary significantly, posing challenges for interoperability and consistent user experience. In the example of tabular regression, Auto-Sklearn offers 4 parameters for configuring a metric (r2, mean squared error, mean absolute error, median absolute error) while AutoKeras offers 7 different parameters (additionally including root mean squared error, mean absolute percentage error, mean squared log error, cosine similarity, log cosh error, but lacking r2 and median absolute error). Also, parameter naming is different between both libraries. What is called mean_squared_error in Auto-Sklearn is called MeanSquaredError in AutoKeras.

An ontology is perfect for aligning the differently used terminologies. ML Ontology is used as the information backbone of the OMA-ML platform. The various configuration options of different AutoML solutions are specified using the classes Configuration_item, ML_library and AutoML_solution as explained in Section 4.4.

The ML training configuration wizard of OMA-ML enables users to set up ML training processes by selecting applicable configuration options provided by the chosen AutoML solutions. Refer to Figure 5 for a screenshot illustrating this functionality. The interface displays configuration parameters such as metric, loss function, max_trials, and tuner for AutoKeras. For the tuner parameter, selectable options are presented in a dropdown menu, including greedy, bayesian, random, and hyperband. All parameters and their corresponding values are dynamically retrieved from ML Ontology.

Figure 5.

Use case configuration wizard.

5.2. Interactive Help

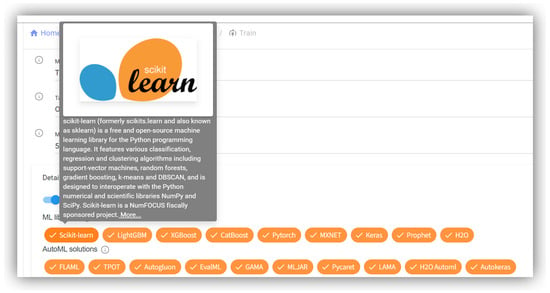

Another use case is interactive help. Data science platforms such as OMA-ML are used by persons with varying levels of expertise in AI and ML. To support this diversity, it is beneficial to provide accessible information not only on core ML concepts—such as ML areas, ML tasks, ML approaches, and metrics—but also on implementations, including ML libraries and AutoML solutions. The alignment of ML Ontology with Wikidata plays a crucial role in enabling this functionality. Approximately 350 ML-related terms are linked to corresponding Wikidata entries, which in turn connect to Wikipedia articles available in multiple languages, facilitating multilingual and context-aware assistance. See Figure 6 for a screenshot illustrating the selection interface for ML libraries and AutoML solutions in OMA-ML. When hovering over a library (e.g., Scikit-learn), a pop-up appears displaying an image and summary text from the English Wikipedia article, along with a link for further reading.

Figure 6.

Use case interactive help.

Empirical validation. To assess the effectiveness of OMA-ML’s interaction design and assistance features, two user studies were conducted and published. A first two-stage qualitative usability study investigated factors contributing to positive user experience in AI systems and evaluated OMA-ML against ISO 9241-110:2020, deriving recommendations that emphasize trust-building interaction principles [22]. A subsequent study implemented these recommendations and demonstrated measurable UX improvements in suitability for tasks, self-descriptiveness, user engagement, and learnability within OMA-ML, supporting an iterative, human-centered approach to AI [23].

6. Discussion

In this section, ML Ontology is compared with requirements specified in Section 1.

6.1. Volume

ML Ontology is notably comprehensive, encompassing ca. 700 individuals that define key machine learning concepts. With roughly 5000 RDF triples, it ranks among the largest domain-specific ontologies for ML that we are aware of. The only ontology for the ML domain comparable in volume is OntoDM with ca. 660 classes representing ML concepts, described by ca. 3700 annotations (AnnotationAssertions, subClassOf relationships, AnnotationProperties, DisjointClasses etc.). The ML Schema Core Specification as an upper-level ontology only specifies 25 classes. According to [4], DMOP includes ca. 720 classes representing ML concepts, described by ca. 4300 annotations (data properties, logical axioms etc.). However, the ontology does not seem to be publicly available, just like the Exposé ontology for data mining experiments. Finally, the MEX vocabulary comprises ca. 250 classes.

To situate ML Ontology relative to prior work, Table 4 offers a compact comparison along scope focus, public availability, size, reasoning/validation support, and intended use.

Table 4.

Comparison of ML Ontology and related ML/DM ontologies.

To formally evaluate correctness and completeness of ML Ontology, a gold standard for ML terminology would be needed. However, to the best of our knowledge, no such gold standard exists. Therefore, an experiment has been performed to estimate correctness and completeness of ML Ontology. The experiment was performed using a state-of-the-art generative AI chatbot (MS Copilot with GPT-5). In this experiment, instances of the main ML Ontology classes were presented and correctness of the instances (false positives for evaluating precision) and missing instances (false negatives for evaluating recall) was prompted for. Table 5 shows the results of this experiment.

Table 5.

Precision, Recall, and F1 Score for ML Ontology classes with examples of false negatives.

The experiment has shown that ML Ontology has a high precision of 1.00, indicating that all instances included in the ontology are correct. This is not surprising since the ontology has been curated by domain experts. The recall is 0.71, suggesting that while the ontology covers a substantial portion of relevant instances, there are still some missing concepts. Samples are shown in Table 5. To include those concepts in ML Ontology is subject to ongoing and future work. The overall F1 Score is 0.83.

6.2. Performance

A benchmark has been performed to evaluate the performance of SPARQL queries on ML Ontology. For this, 9 SPARQL queries of varying complexity have been executed on ML Ontology. Simple queries retrieve all instances of a specific class, medium queries join classes, and high-complexity queries contain aggregations, filters, or transitive closures. Each query has been executed 100 times with execution time and memory usage recorded.

Setup: In-memory SPARQL engine: rdflib 7.1.4, CPU: Intel Core Ultra 7 165H, 3.80 GHz, 32 GB RAM. Table 6 shows the results of this benchmark including the number of results, execution time, and memory usage.

Table 6.

Benchmark results for SPARQL queries: number of results, execution time, and memory usage.

The table shows three sample queries for each complexity category including the number of results. The time column shows the medium execution time from 100 runs in milliseconds. The memory column shows the memory usage observed at query execution in megabytes. The execution times are all below 100 ms, even for complex queries, indicating good performance. Memory usage is also low, with a maximum of 3.35 MB observed for medium-complexity queries. Overall, the benchmark demonstrates that SPARQL queries on ML Ontology can be executed efficiently with low resource consumption, making it suitable for real-time applications.

6.3. Balance Between Simplicity and Expressiveness

ML Ontology deliberately uses lightweight modelling approach (knowledge graph implemented in RDF/RDFS) which is particularly suited for industry use. Reasoning in RDF-based systems is commonly implemented using (i) OWL reasoning under Description Logic (DL) semantics or (ii) SPARQL-based rule execution with forward materialization, optionally organized through SHACL rules. Both approaches support automated inference, but they differ fundamentally in semantics, expressiveness, performance characteristics, and operational behavior.

- SPARQL-Based Materialization with SHACL Organization.

In SPARQL-based inferencing, rules are expressed as CONSTRUCT or INSERT queries that derive new triples and materialize them into the RDF graph. SHACL Rules and SHACL-SPARQL provide a standardized organizational layer for such rule sets [24], defining rule targets, conditions, and metadata, while delegating execution to SPARQL query evaluation. The resulting materialization pipeline repeatedly applies rules until a fixpoint is reached, similar to rule engines such as VLog [25] or WebPIE [26]. This approach is operational, closed-world, and highly flexible, enabling arbitrary graph transformations.

- OWL Reasoning.

OWL 2 DL provides a model-theoretic semantics based on expressive Description Logics [27]. OWL reasoners support classification, satisfiability checking, and query answering under open-world, monotonic semantics. The language includes constructs such as existential and universal quantification, cardinality restrictions, and complex role inclusion axioms. OWL reasoning provides strong global guarantees but is computationally more demanding: full OWL 2 DL reasoning is ExpTime to N2ExpTime-complete [27], and empirical studies show that even optimized reasoners struggle with large or expressive ontologies [28,29]. Query answering under OWL Direct Semantics requires specialized optimizations and still incurs substantial overhead compared to simple SPARQL evaluation [30,31].

We compare both approaches with respect to expressiveness, performance, and operational complexity. For an overview see Table 7.

Table 7.

Comparison of SPARQL-based materialization (with or without SHACL rules) and OWL reasoning.

- Expressiveness.

SPARQL UPDATE supports arbitrary insert/delete operations on RDF graphs. Since iterative application of such rules constitutes a graph-rewriting system, and graph-rewriting systems are known to be Turing-complete [32], iterative SPARQL UPDATE is computationally Turing-complete. Practical systems already exploit this expressiveness for iterative graph algorithms [33,34]. This allows SPARQL-based inferencing to express transformations and procedural behaviors that lie beyond the expressive power of OWL 2 DL. Conversely, OWL provides model-theoretic constructs such as existential and universal quantification, cardinality restrictions, and complex role inclusion axioms [27] that are not natively available in SPARQL rules unless explicitly simulated operationally. Thus, SPARQL-based inferencing is more expressive in a computational sense, whereas OWL is more expressive in a logical and model-theoretic sense.

- Performance.

SPARQL-based materialization typically exhibits polynomial-time data complexity and scales well in practice, since inference reduces to repeated SPARQL query evaluation [35]. Once materialization is complete, query answering is extremely fast because it operates over an explicitly closed-world graph. In contrast, OWL reasoning is significantly more computationally demanding: full OWL 2 DL reasoning is ExpTime to N2ExpTime-complete [27], and empirical studies show that even optimized reasoners struggle with large or expressive ontologies [28,29]. Query answering under OWL Direct Semantics requires specialized optimizations and still incurs substantial overhead compared to simple SPARQL evaluation [30,31].

- Operational Complexity.

SPARQL-based materialization is conceptually simple and easy to integrate into existing RDF pipelines. Rules are transparent, debuggable, and can be organized and documented using SHACL [24]. OWL reasoning, while offering strong formal guarantees, requires more expertise in ontology engineering, careful modeling to avoid unintended inferences, and specialized tooling. Debugging and maintaining OWL ontologies in production environments is often more complex than managing SPARQL rule sets.

In total, SPARQL-based materialization with SHACL organization is a suitable choice for ML Ontology, balancing expressiveness, performance, and operational simplicity. It enables flexible, efficient inferencing tailored to practical application needs without the complexity and overhead of full OWL reasoning.

6.4. Extensibility and Adaptability

ML Ontology is modularised and can be easily extended and adapted to various use cases. The ontology schema provides a clear separation between classes, instances, inference rules, queries and QA checks (see Figure 1). ML Ontology classes are separated in ML concepts and ML implementations (see Figure 2). ML Ontology has been extended continuously over a period of more than five years and the ontology schema has proven stable.

ML Ontology is designed to be platform-agnostic and reusable across technological environments. It is serialized in RDF/Turtle and relies exclusively on Semantic Web standards (RDF/RDFS, SKOS, SHACL, SPARQL), ensuring independence from any specific runtime or storage system. The two application scenarios presented in this manuscript serve as implementation exemplars rather than architectural constraints; none of the classes, properties, or inference/QA mechanisms depend on features of a particular proprietary platform.

The module ML concepts provides a stable, domain-level vocabulary for machine learning independent of implementation concerns. Its classes (e.g., ML_area, ML_task) and relations (e.g., used_for, belongs_to, skos:broader) formalise shared concepts and their interdependencies. This module is intentionally generic and directly reusable in external contexts without modification.

The module ML implementations (e.g., classes ML_library, AutoML_solution) is also generic in its schema. The level of instance-level detail is purposefully scoped to concrete application needs. In the present release, configuration items are modelled more deeply for AutoML solutions because the motivating use cases focus on AutoML orchestration. If a deployment prioritises direct configuration of ML libraries instead, the ontology can be extended incrementally by adding new Configuration_item instances and enumerations, and by linking them to ML_library via existing relations (e.g., can_perform, ml_task, used_for), without changing the core schema.

- Adaptation guidance.

To reuse and tailor ML Ontology in other environments, practitioners typically:

- Extend instances: add domain-specific individuals for ML_task, ML_approach, Metric, and, when needed, new Configuration_item vocabularies for targeted libraries or frameworks.

- Wire semantics: reuse existing predicates (used_for, belongs_to, can_perform, ml_task) to express applicability, capabilities, and configuration scopes; optionally refine taxonomies via skos:broader.

- Maintain alignments: keep or extend published mappings to ML Schema (class-level) and Wikidata (instance-level) to facilitate integrations.

- Leverage QA and reasoning: embedded SHACL/SPARQL checks and the optional forward-chaining rule are orthogonal to any platform and can be reused unchanged; projects may add deployment-specific checks or rules as needed.

Adapting the ontology to additional tools or ecosystems requires only the addition of instances and lightweight enumerations, while the class/property schema remains stable. This design preserves generality in the conceptual core, keeps the implementation module schema generic, and localises application-specific effort to instance additions and optional profiles, thereby supporting reuse beyond the proprietary platform showcased in the examples.

6.5. Built-In Quality Management

ML Ontology comprises built-in quality checks that can be adapted use-case-specifically in order to ensure that quality requirements from the industry are met. As opposed to just documenting modelling guidelines, quality checks can be executed regularly, allowing guideline violations to be detected and fixed. In practice, when the quality checks were implemented first, dozens of modelling errors were detected and fixed. Due to the awareness created by the quality checks, modelling errors have become rare. ML Ontology has be co-edited by more than 15 knowledge engineers over more than 5 years and still has not deteriorated in quality.

6.6. Standards

ML Ontology is solely based on Semantic Web (SW) standards including RDF/RDFS and SPARQL, and uses state-of-the-art ontology schemas such as SKOS and SHACL. Experiments have shown that ML Ontology can easily be deployed as a Labeled Property Graph (LPG) if needed. ML Ontology could be imported without adaptation into Neo4j and the pre-defined SPARQL queries could be automatically converted to correct Cypher queries.

6.7. Public Availability

ML Ontology is published open source (https://github.com/hochschule-darmstadt/MetaAutoML/blob/main/controller/managers/ontology/ML_Ontology.ttl) under an MIT license.

In total, the criteria sufficient volume, performance, expressiveness, extensibility and adaptability, quality and conformance to standards are fulfilled. Therefore, ML ontology can be regarded as industry-ready.

6.8. Limitations

While ML Ontology has been designed to be performant, extensible, and adaptable, certain limitations should be acknowledged. ML is a fast-evolving field, and the ontology requires periodic updates to incorporate emerging concepts and techniques. This is particularly relevant for generative AI approaches, which are currently only partially covered. A semi-automated process for identifying missing concepts using generative AI has been outlined in Section 6 and may be used for future updates. In addition, automated alignment tools (e.g., AML [36]) may be used. Additionally, while the ontology has been tested in specific use cases, broader validation across diverse industry applications would further establish its robustness and versatility.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

In this article, ML Ontology has been presented, an industry-ready ontology for the ML domain. ML Ontology is comprehensive, provides good performance and is extensible and adaptable. In comparison to existing work, ML Ontology provides novel features, including built-in queries and quality assurance. Notably, ML Ontology provides sophisticated reasoning while being based on lightweight modelling languages (RDF/RDFS). Its industry-readiness has been demonstrated by benchmarks and use case implementations within a data science platform.

ML Ontology can be considered ready for use in industry applications requiring the formalisation of ML concepts and their relationships. As future work, we envisage the extension of ML Ontology as an incremental, use-case-driven process. Further applications accessing ML Ontology may define requirements for extensions, e.g., the parametrisation of ML libraries. As ML Ontology is open source, we regard this as a community effort.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in GitHub at https://github.com/hochschule-darmstadt/MetaAutoML/blob/main/controller/managers/ontology/ML_Ontology.ttl.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gruber, T.R. A translation approach to portable ontology specifications. Knowl. Acquis. 1993, 5, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Publio, G.C.; Ławrynowicz, A.; Esteves, D.; Panov, P.; Soldatova, L.; Soru, T.; Vanschoren, J.; Zafar, H. ML-schema: Exposing the semantics of machine learning with schemas and ontologies. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.05351. [Google Scholar]

- Panov, P.; Soldatova, L.; Džeroski, S. Ontology of core data mining entities. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2014, 28, 1222–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keet, C.M.; Ławrynowicz, A.; d’Amato, C.; Kalousis, A.; Nguyen, P.; Palma, R.; Stevens, R.; Hilario, M. The data mining optimization ontology. J. Web Semant. 2015, 32, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanschoren, J.; Soldatova, L. Exposé: An ontology for data mining experiments. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Third Generation Data Mining: Towards Service-Oriented Knowledge Discovery (SoKD-2010), Barcelona, Spain, 24 September 2010; pp. 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Anikin, D.; Borisenko, O.; Nedumov, Y. Labeled property graphs: SQL or NoSQL? In Proceedings of the 2019 Ivannikov Memorial Workshop (IVMEM), Velikiy Novgorod, Russia, 13–14 September 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, A.; Blomqvist, E.; Cochez, M.; d’Amato, C.; Melo, G.D.; Gutierrez, C.; Kirrane, S.; Gayo, J.E.L.; Navigli, R.; Neumaier, S.; et al. Knowledge graphs. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humm, B.G.; Archer, P.; Bense, H.; Bernier, C.; Goetz, C.; Hoppe, T.; Schumann, F.; Siegel, M.; Wenning, R.; Zender, A. New directions for applied knowledge-based AI and machine learning: Selected results of the 2022 Dagstuhl Workshop on Applied Machine Intelligence. Inform. Spektrum 2023, 46, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kifer, M.; Lausen, G. F-logic: A higher-order language for reasoning about objects, inheritance, and scheme. In Proceedings of the 1989 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Portland, OR, USA, 31 May–2 June 1989; pp. 134–146. [Google Scholar]

- Bense, H.; Humm, B.G. An Extensible Approach to Multi-level Ontology Modelling. In Proceedings of the KMIS, Online, 25–27 October 2021; pp. 184–193. [Google Scholar]

- Baylor, D.; Breck, E.; Cheng, H.T.; Fiedel, N.; Foo, C.; Haque, S.; Haykal, Z.; Liu, A.; Córdoba, M.; Mewald, M.; et al. TFX: A TensorFlow-Based Production-Scale Machine Learning Platform. In Proceedings of the 23rd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Halifax, NS, Canada, 13–17 August 2017; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1387–1395. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Pérez, A.; Fernández-López, M.; Corcho, O. Ontological Engineering: With Examples from the Areas of Knowledge Management, e-Commerce and the Semantic Web; Springer: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Lopez, M.; Gomez-Perez, A.; Juristo, N. METHONTOLOGY: From Ontological Art towards Ontological Engineering. In Proceedings of the AAAI97 Spring Symposium, Stanford, CA, USA, 24–26 March 1997; pp. 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Huth, M.; Ryan, M. Logic in Computer Science: Modelling and Reasoning About Systems, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- SPARQL 1.1 Update. W3C Recommendation. 2013. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/sparql11-update/ (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- OWL 2 Web Ontology Language Profiles (Second Edition). W3C Recommendation. 2012. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/owl2-profiles/ (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- SKOS Simple Knowledge Organization System Reference. W3C Recommendation. 2009. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/skos-reference/ (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Calvanese, D.; Cogrel, B.; Komla-Ebri, S.; Kontchakov, R.; Lanti, D.; Rezk, M.; Rodriguez-Muro, M.; Xiao, G. Ontop: Answering SPARQL Queries over Relational Databases. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Semantic Web Conference (ISWC), Vienna, Austria, 21–25 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zender, A.; Humm, B.G. Ontology-based meta automl. Integr. Comput.-Aided Eng. 2022, 29, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humm, B.G.; Zender, A. An ontology-based concept for meta AutoML. In Proceedings of the IFIP International Conference on Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations, Hersonissos, Crete, Greece, 25–27 June 2021; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Feurer, M.; Klein, A.; Eggensperger, K.; Springenberg, J.; Blum, M.; Hutter, F. Efficient and Robust Automated Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–12 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, L.; Humm, B.G.; Krajewski, A.; Zender, A. Towards Improved User Experience for Artificial Intelligence Systems. In Proceedings of the Engineering Applications of Neural Networks; Iliadis, L., Maglogiannis, I., Alonso, S., Jayne, C., Pimenidis, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Zender, A.; Humm, B.G.; Holzheuser, A. Enhancing User Experience in Artificial Intelligence Systems: A Practical Approach. In Proceedings of the FedCSIS Conference on Computer Science and Intelligence Systems, Belgrade, Serbia, 8–11 September 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 113–131. [Google Scholar]

- Knublauch, H.; Kontokostas, D. Shapes Constraint Language (SHACL). Technical Report; W3C. 2017. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/2017/REC-shacl-20170720/ (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Carral, D.; Dragoste, I.; Krötzsch, M.; Urbani, J. VLog: A Rule Engine for Knowledge Graphs. In Proceedings of the ISWC, London, UK, 9–13 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Urbani, J.; Kotoulas, S.; Maassen, J.; van Harmelen, F.; Bal, H. OWL Reasoning with WebPIE: A Web-scale Parallel Inference Engine. Semant. Web 2016, 7, 267–283. [Google Scholar]

- Baader, F.; Calvanese, D.; McGuinness, D.L.; Nardi, D.; Patel-Schneider, P.F. The Description Logic Handbook: Theory, Implementation and Applications, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Alobaid, A.; Parsia, B.; Sattler, U.; Schneider, T.; Glimm, B. OWL2Bench: A Benchmark for OWL Reasoners. In Proceedings of the International Semantic Web Conference (ISWC), Online, 14–17 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Consortium, L. Benchmark Design for Reasoning; Technical Report, Deliverable D4.4.2; Linked Data Benchmark Council: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kollia, I.; Glimm, B.; Horrocks, I. Optimizing SPARQL Query Answering over OWL Ontologies. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2013, 48, 253–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glimm, B.; Ogbuji, C. SPARQL Query Answering over OWL Ontologies. In Proceedings of the Reasoning Web, Vienna, Austria, 3–8 September 2012; pp. 194–239. [Google Scholar]

- Rozenberg, G. (Ed.) Handbook of Graph Grammars and Computing by Graph Transformation; World Scientific: Singapore, 1997; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Techentin, R.; Gilbert, B.; Lugowski, A.; Deweese, K.; Gilbert, J. Implementing Iterative Algorithms with SPARQL. In Proceedings of the EDBT/ICDT 2014 Joint Conference Workshops, Athens, Greece, 28 March 2014; pp. 205–212. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, A.; Reutter, J.L.; Soto, A. Recursive SPARQL for Graph Analytics. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.01816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Meier, M.; Lausen, G. Foundations of SPARQL Query Optimization. In Proceedings of the ICDT, Athens, Greece, 13–19 June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Faria, D.; Pesquita, C.; Santos, E.; Palmonari, M.; Cruz, I.F.; Couto, F.M. The AgreementMakerLight Ontology Matching System. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Ontology Matching (OM 2013), Sydney, Australia, 21–22 October 2013; pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.