Featured Application

This study provides an integrated assessment of microplastic (MP) presence across marine, riverine, and wastewater treatment plant samples in Northern Greece—a region where such data are largely lacking. The proposed analytical workflow, combining microscopy and Py–GC/MS, offers a transferable framework for monitoring programs in Mediterranean coastal zones. The findings offer valuable insights for environmental authorities in establishing baseline MP levels and guiding mitigation strategies for regional water/wastewater quality management.

Abstract

Microplastics (MPs) and nanoplastics (NPs) have emerged as pervasive pollutants across different aquatic systems on a global basis, yet integrated assessments linking wastewater, riverine, and marine environments remain scarce. The present study provides the first comprehensive evaluation of MPs in three interconnected aquatic matrices of Northern Greece, namely surface seawater from the Thermaic Gulf, surface freshwater from the Axios River, and influent and effluent wastewaters from the Thessaloniki WWTP (Sindos). During two sampling periods spanning late 2023 and spring 2024, suspected MPs were isolated, morphologically classified by stereomicroscopy, and chemically characterized through pyrolysis–gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (Py–GC/MS). MPs were ubiquitously detected in all substrates, exhibiting distinct spatial and compositional patterns. Seawater samples displayed moderate concentrations (1.5–4.8 items m−3) dominated by fibers and fragments, while riverine samples contained slightly higher levels (0.5–2.5 items m−3), enriched in fibrous forms and polyolefins (PE, PP). Wastewater influents showed the highest MP abundance (78–200 items L−1; 155.6–392.3 µg L−1), decreasing significantly in effluents (11–44 items L−1; 27.8–74.3 µg L−1), corresponding to a removal efficiency of 81–87.5%, being the first indicative removal efficiencies in a Greek WWTP. Among the different polymers detected, polyethylene, polypropylene, and poly(ethylene terephthalate) were identified as the most prevalent polymers across all matrices. Interestingly, a shift toward smaller size classes (125–500 µm) in effluents indicated in-plant fragmentation processes, while increased concentrations during December coincided with increased rainfall, highlighting the influence of hydrological conditions on MP fluxes. The combined morphological and polymer-specific approach provides a holistic zunderstanding of MP transport from inland to marine systems, establishing essential baseline data for Mediterranean environments and reinforcing the need for integrated monitoring and mitigation strategies.

1. Introduction

Microplastics (MPs) have been ubiquitously detected across marine, freshwater, terrestrial, and atmospheric compartments, emerging as one of the most pervasive environmental contaminants of the 21st century [1,2,3,4]. Their persistence, small size, and large surface area facilitate the adsorption and transport of hazardous chemicals and pathogens, enabling their distribution throughout ecosystems and thus increasing their ecological and toxicological relevance. Concerning their presence, MPs have been detected in various aquatic organisms, including fish and bivalves [5,6], and can be transferred within the planktonic food web [7], ultimately reaching humans mainly through seafood consumption [8]. Moreover, MP detection in human stool, lungs, and placentas has raised increasing concern regarding their internal exposure routes and potential human health effects [9,10]. In general, MP toxicity is related, among other parameters, to the size, polymer type, concentration as well as the duration of exposure and the presence of chemical additives [11].

As far as the sources and pathways of MPs are concerned, these are diverse and complex, encompassing both aquatic and land-based origins. Secondary MPs are generated through physical, chemical, and biological weathering processes such as photo-oxidation, abrasion, and microbial parameters leading to the fragmentation of larger plastic debris [12,13,14]. Land-based sources include paths such as urban runoff, riverine transport, and effluent discharges from wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) and notably constitute major contributors to aquatic plastic pollution [3,15,16]. Although conventional and advanced WWTPs can retain a large portion of MPs within primary and secondary stages of wastewaters treatment, these facilities are not specifically designed to capture particles in the micrometer size scale [17,18,19]. Consequently, fine and buoyant particles based on the density of the plastic particles, can surpass treatment processes and be continuously released into the receiving aquatic bodies, while retained MPs enter in the sewage sludge which can later re-enter the environment through agricultural applications [16].

Within this global framework, the region of Northern Greece represents a particularly significant case for investigating MP pollution due to its strong coupling between urban, riverine, and coastal systems. The Thermaic Gulf, one of the most productive marine ecosystems in Greece, sustains extensive fishing and mussel-farming activities that are vital to the local and national economy [20,21]. Plastic pollution in this region not only poses potential ecological risks but also carries implications for food security and human health, as aquaculture products are directly exposed to MP pollution via several media. Despite the environmental as well as the economic significance of the area, comprehensive data on MP distribution in Northern Greece remain scarce.

Only recent studies have started to address this knowledge gap on MP presence in Nothern Greece. Kermenidou et al. (2023) [22] provided the first documentation of MPs in seawater, sediments, and fish species from the Thermaic Gulf, highlighting the prevalence of polyolefin-based polymers such as polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP) and suggesting potential trophic transfer. A later study by our group [15] extended this research by performing a one-year monitoring campaign applying a pyrolysis–gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (Py–GC/MS) methodology to quantify MPs in the effluents of the Thessaloniki WWTP located in Sindos, identifying temporal variability and dominance of low-density polymers in discharged waters. Furthermore, Kalaronis et al. (2025) [23] reported complementary findings for sand, seawater, and effluent matrices in Northern Greece, providing essential data on morphological and spectroscopic characteristics of MPs in the general region. Collectively, the abovementioned studies have established a strong foundation for understanding MP occurrence in individual aquatic matrices; however, no research to date has concurrently examined the marine, riverine, and wastewater environments under a unified analytical framework.

Based on the above, such an integrated approach is essential for elucidating the source–sink continuum of MPs from inland to marine environments. The Axios River, which discharges directly into the Thermaic Gulf, serves as a major conduit for land-based pollutants, while the Thessaloniki WWTP, located within the same watershed, constitutes a significant point-source of treated effluents potentially contributing to the MP load of the receiving coastal waters. Given that both the Axios River and the Thessaloniki WWTP discharge directly into the inner Thermaic Gulf, these three systems represent an interconnected land–river–sea pathway, making it important to examine their MP profiles within a unified framework. Within this context, investigating these three interconnected environments concurrently allows for a comprehensive understanding of MP transport dynamics, spatial variability, and removal efficiency along the hydrological continuum.

From an analytical perspective, most existing Mediterranean studies have relied on microscopic and spectroscopic techniques, such as FTIR and Raman microscopy [24,25,26]. While these approaches provide valuable polymer identity information, they are limited by particle size detection thresholds and potential interference from organic matter, often resulting in the underestimation of total polymer loads [27]. From the other side, thermoanalytical techniques, particularly Py–GC/MS or other conjugated thermoanalytical techniques, offer a robust alternative by enabling direct quantification of polymer mass independently of particle size or morphology [28,29,30]. Although the use of Py–GC/MS has expanded in recent years within this analytical era [19,31,32], its application to integrated, multi-compartment studies providing accurate mass concentration data remains limited. Beyond MPs, there is a growing scientific focus on even smaller plastic particles, namely nanoplastics (NPs, <1 µm), which remain analytically challenging mainly due to their size, colloidal behavior, and extremely low mass concentrations. Under this light, developing workflows capable of bridging the micro–nano continuum is therefore a key research priority. The optimized Py–GC/MS pretreatment and polymer-specific analytical strategy developed and applied in the present study establishes a methodological foundation that can be adapted in future works toward the detection and quantification of NPs.

In this context, the present study represents the first comprehensive assessment of MP occurrence across three interconnected aquatic environments of Central Macedonia, Northern Greece, namely, surface seawater from the Thermaic Gulf, surface river water from the Axios River, and influent and effluent wastewater samples from the Thessaloniki WWTP located in Sindos. By combining stereomicroscopic examination with polymer-specific Py–GC/MS analysis, this study provides a robust evaluation of MP abundance, morphology, and composition across distinct substrates. The main objectives were to determine the occurrence and characteristics of MPs in each matrix, compare their concentration and polymeric composition to identify potential linkages between inland and coastal systems, as well as evaluate the influence of environmental conditions such as rainfall on their distribution and fluxes.

Despite the significance of the Axios–Thermaic ecosystem, no study to date has provided a unified assessment of MP occurrence across wastewater, riverine, and coastal environments in this region. Overall, this work delivers the first integrated depiction of MP pollution in Northern Greece, bridging the gap between isolated environmental compartments and providing critical baseline information for future monitoring, source apportionment, and risk assessment by applying an integrated optical–thermoanalytical approach. The outcomes are expected to support the design of effective mitigation strategies and policy measures to limit MP emissions from urban and industrial sources to the marine environment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Ultrapure water was obtained using a Milli-Q purification system (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) and further filtered through Ø 45 mm, 1.6 μm pore size Whatman glass fibre filters (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) prior to use. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30%) and iron (II) sulfate (FeSO4·7H2O) used for the Fenton oxidation were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Zinc chloride (ZnCl2, ≥98%) used for density separation was of analytical grade (Sigma-Aldrich). Ethanol (≥99.8%, analytical grade) was used for the cleaning and rinsing of all glassware and was purchased in glass bottles to avoid plastic contamination.

All laboratory glassware was rinsed thrice with ultrapure water and ethanol, and kept covered with aluminum foil to prevent airborne contamination. Polymeric reference materials of common plastics were used for quality control and for confirming polymer identification during Py–GC/MS analysis. Fragments of high-density polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), polystyrene (PS), poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET), poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC), polyamide/nylon-6,66 (PA), polyurethane (PU), polycarbonate (PC), and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) were cut with a scalpel into small pieces (10–100 µg) and used as polymer standards. Additives commonly found in commercial plastics (e.g., UV stabilizers) were not detected in the total ion chromatograms (TICs), likely due to their low concentrations (<1%). The solvents used for the standard mixtures were as follows: dichloromethane (DCM, Fluka > 98%, analytical grade), tetrahydrofuran (THF, Carlo Erba (Milan, Italy), for HPLC, non-stabilized), and 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP, Fluorochem (Hadfield, UK)), while calcium carbonate (CaCO3, 98.5–100.5%) was obtained from ChemLab (Zedelgem, Belgium). All solvents and reagents were of analytical or HPLC grade and were used as received without further purification.

2.2. Study Area

The present study was conducted in the region of Central Macedonia, Northern Greece, encompassing three interconnected aquatic environments that represent different stages of anthropogenic influence: marine (Thermaic Gulf), riverine (Axios River), and wastewater effluents from the Thessaloniki’s WWTP located in Sindos.

The Thermaic Gulf, a semi-enclosed embayment in the northwestern Aegean Sea, is a major receiving body for both riverine discharges and urban wastewater inputs [33,34]. It is characterized by intense coastal activities, including port operations, industrial zones, and dense urban development [35]. The Gulf receives also inflows from four major rivers, namely Axios, Aliakmon, Loudias, and Gallikos, which collectively transport considerable quantities of suspended solids and organic matter from upstream agricultural and industrial regions [36,37].

The Axios River, the primary freshwater contributor to the Gulf, has a total length of approximately 388 km, with an average discharge of 158 m3/s, and drains a catchment area extending across Greece and North Macedonia [38]. It flows through agricultural, urban, and industrial areas, serving as a major vector for the transport of land-based pollutants and plastic litter into the marine environment.

As for the third studied area, the Thessaloniki’s WWTP (operated by EYATH S.A. and located in Sindos, Greece) treats approximately 155,000–160,000 m3/day of wastewater from more than one million inhabitants. The plant operates a secondary activated sludge treatment system, followed by chlorination, before discharging the treated effluent into the inner Thermaic Gulf. The facility receives both domestic sewage and industrial effluents (5–10%), as well as stormwater runoff due to the combined sewer network in Thessaloniki [39]. Therefore, the WWTP acts as a significant intermediate node linking terrestrial and marine compartments [40].

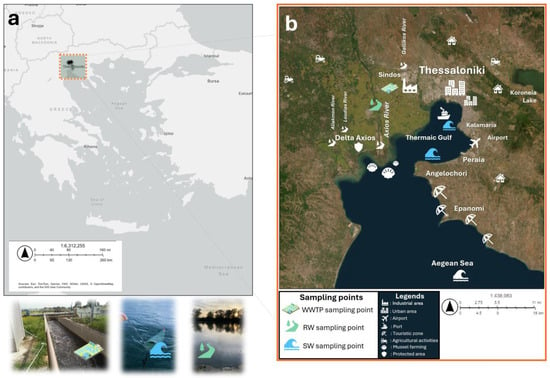

As for the geographical location of all sampling points along with major anthropogenic activities in the surrounding area, these are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Locations of sampling sites in the study area of the Thermaic Gulf and adjacent riverine and wastewater systems. (a) Geographic position of the study region within Greece. (b) Satellite map showing the three sampling matrices. Major geographical and anthropogenic features are also shown, including the urban and industrial zones of Thessaloniki, the agricultural areas surrounding the Axios Delta, and the mussel farming sites along the western coastline.

2.3. Sampling Methodology

Sampling campaigns were performed between October 2023 and May 2024, encompassing two distinct sampling periods selected to represent different hydrological and meteorological conditions. Wastewater influent and effluent samples were collected during October–December 2023, whereas river water and seawater samples were collected during March–May 2024. Samples were obtained from three representative matrices: seawater, river water, and wastewater influent/effluent.

For all sampling procedures, metallic and glass equipment was used, and plastic materials were avoided to minimize sample contamination. All containers were rinsed three times with ultrapure water and ethanol prior to use. Samples were stored in glass bottles, sealed with aluminum foil, and transported to the laboratory at 4 °C for further processing within 48 h. Detailed sampling and pre-treatment information for the whole series of samples is presented in Supplementary Material, Section S1, Table S1.

- (i)

- Seawater samples:

Surface seawater was collected from two stations located within the inner Thermaic Gulf, including the Port of Thessaloniki and the Angelochori coastal area during the period March–May 2024. During sampling, wind conditions were calm, with speeds not exceeding 2 Beaufort, resulting in wave heights below 50 cm [41]. Sampling campaigns were conducted using a plankton net (KC, Silkenborg, Denmark) with a 100 µm mesh size, 30 cm mouth diameter, and 80 cm length, towed for approximately 10–15 min at a vessel speed of 1–3 knots. The effective filtered volume was determined using a Hydro-Bios flowmeter (Altenholz, Germany) mounted at the net opening. Collected material was rinsed from the cod-end with filtered deionized water and transferred to pre-cleaned glass bottles.

- (ii)

- River water samples:

Grab samples (5–20 L each) were obtained from the Axios River for the same sampling months as above, where direct access was achieved from the riparian zone at locations that allowed safe sampling [42,43]. Water was collected instantaneously at approximately 0.5 m below the river surface using clean PE containers. The volume of each sample ranged between 5 and 20 L, depending on the prevailing conditions at the sampling site. Particular care was taken to avoid disturbance of the substrate or the inclusion of solid particles from the riverbed into the sample. All samples were immediately stored in a shaded and cool environment during transport to the laboratory and kept at 4 °C until further pre-treatment.

- (iii)

- WWTP samples:

Sampling was conducted on a monthly basis over three consecutive months (October–December 2023), covering both the influent (inlet) and effluent (outlet) streams of the Sindos WWTP. Sample collection was carried out with the kind assistance of the WWTP personnel. For influent samples, grab sampling was performed at the plant’s inlet channel, immediately after the primary mechanical screening stage, at a depth of approximately 0.5 m below the water surface. The volume of influent samples ranged between 2 and 5 L, according to existing conditions. Samples were collected in clean containers previously rinsed with distilled water and covered with aluminum foil to prevent contamination.

In contrast, for effluent sampling, composite samples were used, representing a 3–4-day collection period. These composite samples were collected from the plant’s outlet channel, after the chlorination stage, and provided a more representative profile of the treated wastewater, as in our previous study [15]. The total volume of effluent samples ranged between 70 and 85 L. After collection, effluent samples were on-site filtered through a series of sieves with graded mesh sizes (e.g., 5 mm, 2 mm, 1 mm, 0.5 mm, and 0.125 mm), following a volume-reduced sampling approach. For influent samples, immediate filtration was performed through two successive sieves with mesh sizes of 4 mm and 0.125 mm to remove coarse debris and retain the MP fraction of interest.

Residues retained on each sieve were rinsed with 100–500 mL of ultrapure water and transferred into clean glass beakers or Erlenmeyer flasks, covered with aluminum foil, and stored at 4 °C until further laboratory processing. Through this procedure, the final volume of each concentrated sample was reduced to approximately 1–2.5 L, facilitating subsequent pre-treatment and analytical steps.

2.4. Pre-Treatment and Isolation of MPs

For the further processing of the collected samples and the isolation of suspected MPs, a multistep pre-treatment procedure was applied. Each sample (1–2 L) was first vacuum-filtered using glass filtration equipment and glass fiber filters. The selected filters were suitable and fully compatible with subsequent Py–GC/MS analysis. All filtration steps were conducted under a laboratory fume hood to prevent airborne contamination. Following filtration, the filters were transferred to clean Petri dishes and left to dry at room temperature for approximately three hours.

To remove any residual organic matter adhering to the filter surfaces or sample containers, ultrapure water was used for a final rinse. The filters were then transferred into clean glass Erlenmeyer flasks, where 30 mL of H2O2 was added per filter to promote oxidative digestion and degradation of organic matter. Within this step, samples were being stirred at 60 °C under gentle magnetic stirring (150 rpm) for 48–72 h. In cases where organic content remained high (as in the occasion of wastewater samples), the Fenton reagent was applied under controlled conditions (not exceeding 40 °C) to enhance oxidation efficiency. It should be noted that according to the literature, the application of strong oxidative agents, such as H2O2 and Fenton’s reagent, may induce partial fragmentation of very brittle or already weathered plastic particles, particularly when longer digestion times are required [44]. Although the selected treatment conditions follow widely used protocols and were optimized in our case to balance effective removal of organic matter with preservation of particle structure, a minor bias toward smaller size fractions cannot be fully excluded. In some river water samples, when necessary (e.g., RW_2), a density separation step using a saturated ZnCl2 solution was applied after digestion to remove denser mineral particles and facilitate more efficient isolation and identification of MPs, which generally exhibit lower densities. The density separation step using ZnCl2 was applied selectively in river-water samples based on the observed particulate load via microscopy.

For all wastewater samples, oxidative digestion using Fenton’s reagent was systematically applied due to their high organic load. This treatment proved highly effective in reducing turbidity and removing organic residues, allowing for clearer sample matrices and improved microplastic recovery [45]. After digestion, filters were carefully rinsed with ultrapure water to detach MP particles from the surface and then re-filtered using clean glass fiber filters. The final filters were stored in Petri dishes within a desiccator until microscopic observation and, finally, Py–GC/MS analysis.

The macroscopic appearance of the post-digestion filters varied notably among samples, especially for influents, reflecting their high suspended solids content. In contrast, effluent filters appeared more uniform and cleaner, facilitating more accurate MP identification. Finally, the lower detection limit for MPs was defined by the sampling and pre-treatment methodology used for each sample type. Specifically, for river water and wastewater samples, the detection limit was set at 125 µm, corresponding to the mesh size of the sieves employed, while for seawater samples, it was >100 µm, in accordance with the plankton net aperture used [46]. Herein, it should be acknowledged that the use of a 100–125 µm mesh size inherently restricts the detection of smaller MP particles (<100 µm), a fact that may lead to a relative underestimation of the finest fraction and limits direct comparability with studies employing finer filtration cutoffs or spectroscopic techniques with lower size-detection thresholds. To evaluate recovery efficiency, spiking experiments were conducted by adding known quantities of polymer reference mixtures into ultrapure water (~1 L) and processing them using the same protocol [15]. Recovery rates were consistently above 80% for all tested polymers.

A schematic overview of the pre-treatment steps applied to all aqueous samples is presented in Supplementary Material, Section S1, Figure S1.

2.5. Characterization and Analysis of MPs

The isolated particles retained on glass fiber filters after pre-treatment were subjected to both microscopic and thermoanalytical examination. Morphological classification and enumeration actions were performed via stereomicroscopy, while Py–GC/MS analysis was employed for chemical identification and quantification of polymer types. Quality assurance and control measures were applied throughout the analytical workflow to minimize contamination and ensure data reliability.

2.5.1. Microscopic Observation

All filters were examined under a stereomicroscope (Carl Zeiss SteREO Discovery.V20, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with a ProgRes GRYPHAX Altair digital camera. Suspected MPs were visually identified and categorized according to shape (fibers, fragments, films, foams, and pellets), color, and size. Image analysis and dimensional measurements were performed using JENOPTIK GRYPHAX® software (version 2.1) at magnifications ranging from ×7.5 to ×50. The classification of synthetic fibers was based on morphological criteria including: (i) smooth and homogeneous surface texture, (ii) absence of cellular or organic structures, (iii) uniform diameter along the entire length, and (iv) distinctive curvature and color uniformity [47].

2.5.2. MP Number Concentration Calculation

The abundance of MPs in each sample was calculated as the number of items per unit of sampled water volume, expressed as items/m3 for seawater and river samples, and items/L for wastewater samples. Concentrations were determined according to Equation (1):

All values were corrected for laboratory and procedural blanks, which were subtracted from the final results. MP abundance values are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of replicate analyses, with procedural blanks subtracted. Given the limited number of samples per matrix and the exploratory nature of this survey, formal inferential statistical tests (e.g., ANOVA) were not applied, as they would not yield meaningful or robust comparisons. Figures were finished using OriginPro 2018. Information as regards the statistical analysis concerning the Py–GC/MS methodology established for quantitative analysis of MPs is the same as in our previous work [15].

2.5.3. Py–GC/MS

Chemical identification and quantification of nine polymer types (Table S2) were performed with a double-shot pyrolyzer (EGA/PY-3030D, Frontier Laboratories, Fukushima, Japan) coupled to a Shimadzu GC–MS (QP2010 Ultra Plus/MS-QP2010SE, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). Full analytical conditions, marker compounds selection, and validation data for the developed methodology are provided thoroughly in Supplementary Material, Sections S2 and S3.

Aliquots of the digested, dried residue, either scraped directly from the glass-fiber filter or hand-picked under a stereomicroscope, were transferred to stainless-steel (Eco-cup) pyrolysis cups in the presence of CaCO3 (catalyst) to enhance diagnostic marker formation for specific polymers (e.g., PET/benzophenone, PC/4-isopropenylphenol, PU/MDA). Samples were analyzed in single-shot mode at 600 °C under helium (flow ~1.0 mL min−1). Chromatographic separation was achieved on an Ultra ALLOY® (5% diphenyl/95% dimethylpolysiloxane) column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm) with oven programming 50 °C (1 min) to 300 °C (10 °C min−1, 4 min hold). The MS operated in EI (70 eV), and scanning m/z 45–500. Polymer identification relied on characteristic pyrolysis marker compounds and F-Search (Frontier, v4.3) library matching, verified against polymer standards for PE, PP, PS, PET, PVC, PA, PC, PMMA, and PU (see Section S2, Table S5).

Quantification used extracted-ion chromatograms of the selected marker ions (Table S5) and external calibration from gravimetrically prepared multi-polymer standards analyzed under identical conditions (see Section S3). The method showed excellent linearity (typically R2 ≥ 0.98), reproducibility (RSD < 15% for most polymers), and mass-on-cup LOD/LOQ ranges of ~3.6–37 µg (LOD) and 10.8–112.6 µg (LOQ), respectively (Table S6). Method validation with binary and 9-polymer mixtures confirmed accurate recovery and reliable library identification in complex matrices (Section S3, Table S7).

2.5.4. Contamination Mitigation

To minimize the introduction of extraneous MP particles, multiple contamination control measures were applied throughout sampling, sample processing, and analysis. All laboratory work was carried out under a laminar flow cabinet or fume hood to limit airborne contamination. Laboratory personnel consistently wore cotton lab coats, latex gloves, whereas the use of plastic equipment was strictly avoided; instead, only glass, stainless steel, or Teflon-coated materials were used.

Before use, all glassware and metal tools (e.g., tweezers) were rinsed thrice with ethanol solution and ultrapure Milli-Q water, then covered with aluminum foil when not in operation. Work surfaces were thoroughly wiped with 70% v/v aqueous ethanol solution before and after each analytical session. All reagents used during sample preparation, including hydrogen peroxide and zinc chloride, were pre-filtered through 1.6 µm glass fiber filters (Whatman GF/F, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) to remove potential contaminants.

To evaluate possible contamination throughout the analytical workflow, procedural, laboratory, and instrumental blanks were systematically included. Procedural blanks (n = 5) consisted of filtered Milli-Q water processed through the entire digestion, separation, and filtration protocol alongside environmental samples. Laboratory blanks (n = 5) were open Petri dishes containing pre-filtered Milli-Q water, exposed to ambient laboratory conditions during sample handling to assess airborne deposition. Instrumental blanks (n = 10) were run between every ten Py–GC/MS injections to check for potential polymer carryover.

Blank analyses showed negligible contamination. No detectable polymer peaks were observed above quantification limits in the Py–GC/MS chromatograms, and only sporadic fibers (<2 item per filter) were found under the stereomicroscope. These background values were subtracted from the corresponding sample results to yield corrected concentrations. Overall, these rigorous controls ensured that all reported data accurately represent the environmental presence of MPs, free from significant laboratory or procedural bias.

3. Results

3.1. Seawater Samples

The occurrence of MPs in the Thermaic Gulf was investigated through the analysis of six surface-water samples collected from two coastal stations: within the Port of Thessaloniki (samples named SW_1) and the less impacted Angelochori coastal area (SW_2). Each site was sampled three times (March, April, and May 2024) to capture potential seasonal variation in abundance and composition (see Supplementary Material, Table S1). All samples contained MPs, with clear differences between the two sites in terms of particle size, morphology, and color distribution.

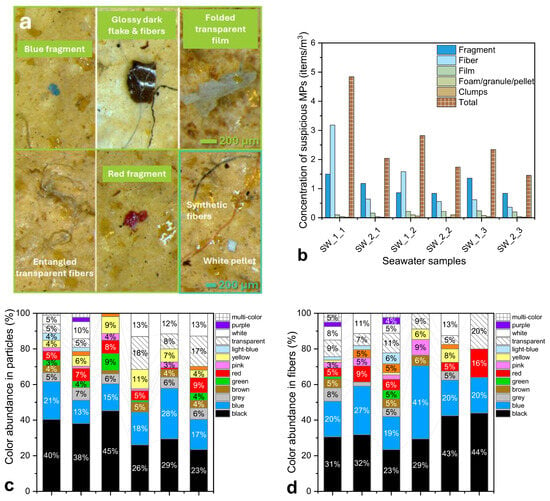

Representative stereomicroscope images of isolated MPs are presented in Figure 2a, which illustrates the morphological diversity observed in the seawater samples. The main morphological types recorded included fibers, fragments, films, and spherical particles, all typical of secondary MPs resulting from the degradation of larger plastic debris. Synthetic fibers, often found as blue or black, were the dominant color class, followed by angular fragments, thin semi-transparent films, and occasional spherical particles and pellets. Many particles showed evidence of environmental weathering, such as rounded edges, surface cracks, and pitting, consistent with prolonged mechanical and photo-oxidative degradation. Fibers were frequently entangled with one another or with organic residues, compatible with origins from synthetic textiles, fishing lines, or nets, whereas films likely derived from degraded packaging materials. The morphological variability observed between samples reflects the multitude of potential sources affecting the inner Gulf.

Figure 2.

(a) Representative images of suspected MPs observed in seawater samples, including fragments, fibers, films, and pellets. (b) Concentration of suspected MPs (items/m3) in seawater samples collected from March to May, categorized by morphology. (c,d) Color distribution (%) of identified particles (c) and fibers (d) in seawater samples. (e,f) Size distribution of particles (e) and fibers (f) represented by boxplots, showing variability among sampling periods.

Color distribution analysis (Figure 2c,d) showed a predominance of blue, black, and transparent/white tones, with brightly colored particles (red, yellow, orange) being scarcer. The color heterogeneity indicates complex and overlapping pollution sources, including textile fibers, tire-wear residues, paint flakes, and packaging waste, while color fading likely results from long-term exposure to sunlight and seawater oxidation.

Particle-size distribution (Figure 2e,f) revealed that the majority of suspected MPs fell within the 500–1000 µm size range for irregular particles, while fibers were typically 500–1500 µm long. Median values consistently remained below 500 µm, whereas a few large outliers (>2000 µm) were observed, particularly for fibers. These dimensions overlap with those of many zooplanktonic organisms and their prey, implying a high potential for non-selective ingestion by lower-trophic species. Smaller particles (<300 µm), although less frequent, may be of greater biological relevance due to their increased bioavailability and ability to penetrate tissues of higher organisms. The overall prevalence of fine-sized MPs suggests that pollution in the Thermaic Gulf is chronic and advanced, dominated by particles produced through ongoing fragmentation of legacy plastics. The similarity in size distributions between SW_1 and SW_2 implies that hydrodynamic mixing and dispersion processes tend to homogenize MP characteristics across the inner Gulf.

Total MP concentrations (Figure 2b) ranged between 1.5 and 4.8 items m−3, with an average of 2.9 ± 1.0 items m−3. Higher values were consistently recorded at the Port of Thessaloniki, where urban, industrial, and port-related activities exert stronger anthropogenic pressure, whereas the Angelochori station exhibited comparatively lower loads. These levels correspond to mild pollution relative to other semi-enclosed Mediterranean systems (see Section S4, Table S8), placing the Thermaic Gulf among the less MP polluted coastal regions.

3.2. River Samples

The investigation of MPs in the Axios River aimed to assess the contribution of riverine discharges to the MP load of the Thermaic Gulf, since rivers are internationally recognized as key pathways for transporting MPs from terrestrial to marine environments [48,49,50]. Previous studies have shown that MP pollution in the Gulf is mainly controlled by riverine inflows [51,52,53], which can carry plastic loads up to 40–50 times higher than those typically recorded in open-ocean surface waters [54]. In the Mediterranean context, river discharges such as those of the Pineios and Kifisos have been reported to reach or exceed 25–30 items/m3 [53,55]. Despite their recognized significance, river systems in Greece remain underexplored with respect to MP pollution.

In this study, three surface-water samples (RW_1–3) were collected from the Axios River at different times to provide an initial assessment of its MP load. The first sample (RW_1, 20 L) exhibited high sand content, as observed during pre-treatment and microscopic examination. Consequently, several white and black particles, likely inorganic materials or natural sediments, were excluded from the final count to avoid overestimation. This led to the inclusion of an additional density-separation step (using ZnCl2 solution) in subsequent samples (RW_2 and RW_3), as described in Section 2.4, to enhance separation efficiency and particle recovery.

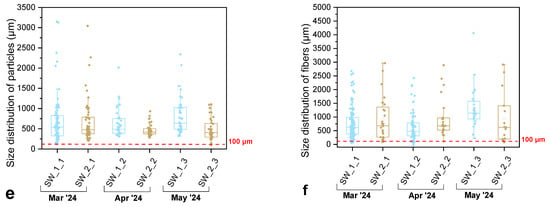

The concentrations of MPs in Axios River samples were relatively low but indicative of measurable pollution (Figure 3b). The highest value recorded was 2.5 items/m3 (RW_1), comparable to the lower range reported for the Rhine River [56] and significantly below those observed in highly urbanized systems such as the Seine or Elbe, where concentrations can exceed 100 items/m3 [57,58]. The subsequent samples, RW_2 and RW_3, exhibited lower concentrations (0.5–0.8 items/m3), likely influenced by smaller sampling volumes (5 L) and natural hydrological variability. Although moderate, these values confirm the presence of MPs in the Axios River and support the notion that rivers act as important vectors transporting MPs from inland areas to coastal ecosystems.

Figure 3.

(a) Representative images of suspected MPs observed in river water samples, including fragments, fibers, and pellets. (b) Concentration of suspected MPs (items/m3) in river water samples collected from March to May, categorized by morphology. (c,d) Color distribution (%) of identified particles (c) and fibers (d). (e,f) Size distribution of particles (e) and fibers (f) represented by boxplots, illustrating variability among sampling periods.

Morphological analysis (Figure 3b) revealed that the majority of identified particles were fibers and fragments, as indicated also by the microscopy images (Figure 3a), while films and spherical particles were rare or absent. Fibers were typically straight or slightly curved, varying in length and color, suggesting origins from synthetic textiles, urban wastewater effluents, or agro-industrial sources. Fragments displayed irregular shapes, rough surfaces, and signs of discoloration, indicative of mechanical abrasion and photo-oxidative weathering. Herein, the predominance of fibers aligns with findings from other Mediterranean river studies, where fibrous MPs are the most common morphology due to wastewater and urban discharge inputs [53,59]. For comparison convenience please check Section S4, Table S9. In sample RW_1, the presence of fiber agglomerates suggested possible aggregation with organic or inorganic particles, which may enhance their environmental stability and persistence in the water column.

As for the color distribution of these types of samples (Figure 3c,d), it showed that transparent/white and black particles were most common, with smaller proportions of blue and green items. Brightly colored MPs were scarce, consistent with other river studies reporting the dominance of neutral or weathered polymers due to environmental exposure and photodegradation [60,61].

Particle-size distribution (Figure 3e) showed that most MPs were within the 200–1000 µm size range, with median values generally below 500 µm. The majority of particles and fibers were concentrated near 300–500 µm, while a few larger outliers (>1500–2000 µm) were observed, mostly among fibers. Notably, this pattern mirrors the relative reported for the Ebro River [58] and the Têt River [62], where most MPs fell between 250 and 700 µm. Such size distributions are indicative of advanced degradation of macroplastics through photo-oxidation and mechanical fragmentation, particularly in upper water layers, coupled with selective settling of larger, denser particles. Smaller MPs (<300 µm) were detected less frequently, likely due to methodological limitations of stereomicroscopic detection and potential masking by adhering organic matter. Fibers, as presented in Figure 3f, were generally within the 500–1500 µm range, a typical feature of synthetic fibers released from textile washing and industrial effluents, which is in agreement with European river datasets [53,63].

3.3. Comparison Between Seawater and River Water Samples—Quantitative Results

The comparative evaluation between surface seawater and river water samples revealed distinct differences in the morphological distribution, color composition, particle size range, and polymer composition and concentrations of the identified MPs. It is thought that these differences reflect the contrasting hydrodynamic regimes and pollution sources influencing each aquatic environment. A comparative discussion of these separate matrices is delivered below for each characteristic, separately.

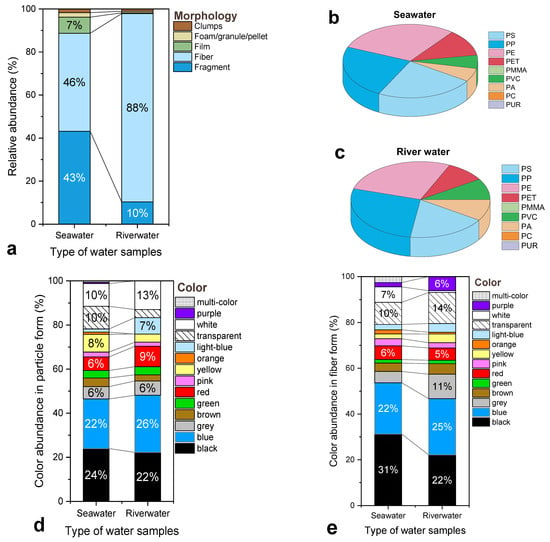

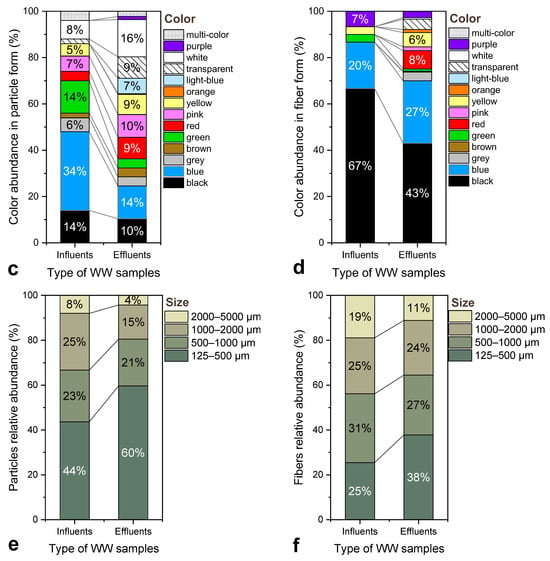

Morphological characteristics: As shown in Figure 4a, fibers dominated the river water samples, accounting for 88% of the total relative abundance, compared to 43% in seawater. In contrast, seawater samples exhibited a more balanced composition between fibers (43%) and fragments (48%), while films, pellets/spherical particles, and aggregates contributed minor proportions. The prevalence of fibers in the Axios River is consistent with findings from other large European rivers, such as the Elbe and Rhine, where fibers constitute the dominant morphotype [58]. The observation of fiber agglomerates in river samples, especially RW_1, may be linked to association with organic matter or incomplete removal of sediment-bound materials during pre-treatment. These results suggest that riverine MPs are primarily derived from anthropogenic discharges, notably textile fibers, urban runoff, and wastewater effluents, whereas the more heterogeneous composition in seawater reflects mixed coastal and marine sources.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the characteristics of suspected MPs in seawater and river water samples: (a) Relative abundance of morphological categories; (b,c) Relative frequency of polymer types identified in seawater and river samples, respectively; (d) Color distribution of particle-shaped MPs; (e) Color distribution of fiber-shaped MPs; (f) Size distribution of particles; and (g) Size distribution of fibers.

Polymer composition: The distribution of polymer types identified by Py–GC/MS is illustrated in Figure 4b,c. Seawater samples were dominated by PE, PP, and PS, which together accounted for more than 60% of the total relative abundance. These polymers are typically associated with packaging materials, single-use products, and fishing-related plastics, consistent with other coastal studies [22,64]. River samples displayed greater heterogeneity in polymer composition. Although PE and PP remained the most abundant, substantial proportions of PET and PA were also recorded. The increased presence of PET likely originates from textile fibers, beverage bottles, and industrial materials, while PA is often linked to effluents from WWTPs or runoff containing synthetic textiles or aquaculture residues. PVC, detected in higher proportions for the river samples, indicates inland industrial or construction-related inputs. Overall, it is noteworthy that PE and PP consistently dominate both the riverine and marine matrices. Considering the hydrological connectivity between the Axios River and the inner Thermaic Gulf, such overlap in dominant polymer types is consistent with a land-to-sea transport pathway, in line with the known influence of riverine particulate inputs on the Gulf’s coastal waters [65]. The recurring presence of shared polymers, combined with similar morphological characteristics, suggests that riverine discharges may contribute to the MP burden observed offshore. However, given the limited number of samples, this interpretation remains qualitative and is not intended as a definitive source-apportionment.

Color distribution: The color variability observed across both environments (Figure 4d,e) possibly reflects the diversity of pollution sources and degradation states of the MPs. In seawater, the predominant colors among particles were black (24%), blue (26%), and transparent (22%), while fibers exhibited similar patterns, with blue (30%) and transparent (25%) being the most frequent hues. River samples also showed high proportions of black and blue fibers, alongside occasional colored particles (red, green, purple), which are likely associated with synthetic textiles, dyed plastics, or painted surfaces. Such distributions agree with studies linking colored MPs to wastewater and agricultural runoff inputs [18,66]. The overall dominance of dark and neutral tones in both matrices suggests possible extensive photo-oxidative weathering and aging during transport and exposure. However, it has to be noted that no direct source-apportionment analysis was performed, and therefore specific product-level origins cannot be inferred from these characteristics alone.

Particle size distribution: The particle-size analysis (Figure 4f,g) revealed notable differences between the two environments. In seawater, most MPs were within the 125–500 µm range, whereas the river samples exhibited a higher proportion of smaller particles (<125 µm), particularly among fragments. These smaller MPs may originate from primary sources, such as industrial abrasives or synthetic fibers, or indicate advanced degradation of larger plastics. Similar trends have been documented by Lechner et al. (2014), who observed that rivers often act as conduits for smaller microplastic particles due to limited dispersion and reduced exposure to solar radiation compared to marine systems [67]. The broader size spectrum in seawater likely reflects mechanical mixing, aggregation, and resuspension processes occurring in the nearshore zone of the Thermaic Gulf.

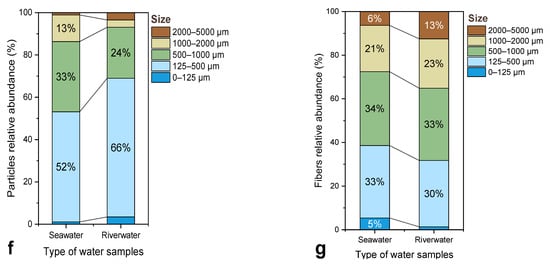

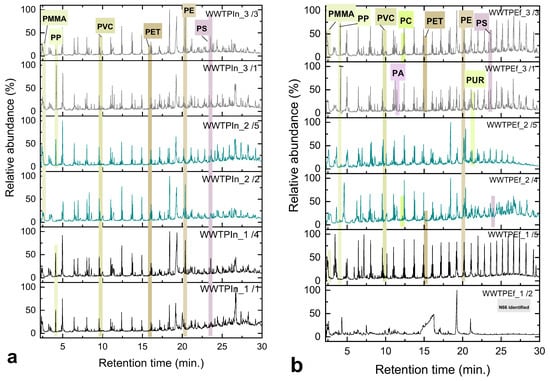

Quantitative data and Py–GC/MS results: Quantitative polymer analysis by Py–GC/MS instrumentation provided complementary information on MP concentrations expressed in mass-based units (µg/L) (see Section 4, Table 1). The chromatograms of representative samples are shown in Figure 5. In seawater samples, measurable concentrations were primarily detected for PE, PP, PS, and PET, ranging from below the LOQ to approximately 0.01 µg/L. Polymers such as PVC, PUR, and ABS were present only at trace levels or were undetected. Conversely, river water samples exhibited markedly higher polymer mass concentrations, with PE reaching up to 13.4 µg/L and PP up to 10.4 µg/L (sample RW_2_2). These results confirm that Axios River acts as a significant source of plastic pollutants entering the marine zone. The values obtained by our analytical methodology are comparable to concentrations reported for major European rivers such as the Danube and Rhine, where PE and PP were identified at similar or higher levels [53,56]. The elevated polymer mass, despite relatively low item counts, further suggests that riverine MPs are larger or denser particles, whereas seawater samples are dominated by lighter and finer fibers.

Table 1.

Comprehensive table of MP mass concentrations (μg/L) detected in the studied environmental samples using the Py–GC/MS technique.

Figure 5.

Representative total ion chromatograms (TICs) of selected samples: (a) seawater and (b) river water, with annotated peaks corresponding to the detected polymers.

Together, these findings underline the complementary nature of number- and mass-based assessments: abundance data capture particle frequency, while Py–GC/MS quantification reveals polymeric load, offering a more complete view of the transport continuum from riverine to marine environments.

3.4. WWTP Samples

Following the assessment of seawater and river water, this section focuses on suspected MPs in influent and effluent wastewater from the Thessaloniki WWTP. As discussed earlier, WWTPs are pivotal interfaces in moderating environmental MP pollution, acting as primary receivers of urban and industrial discharges before their final release to natural waters [3,18,19]. The Thessaloniki’s facility, located on the city’s western periphery and serving > 1 million inhabitants, treats 155,000–160,000 m3 day−1 via secondary activated sludge and chlorination, with the treated effluents discharged into the Thermaic Gulf [39]. Although mechanical/biological steps remove a substantial fraction of particulates, numerous studies show that non-negligible MP loads can persist in the final effluent, influenced by seasonality, meteorology, and hydraulics [15,68,69,70].

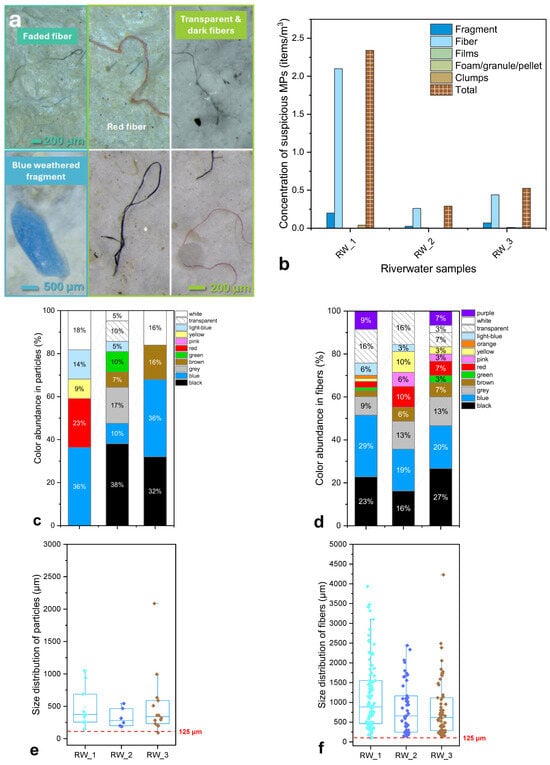

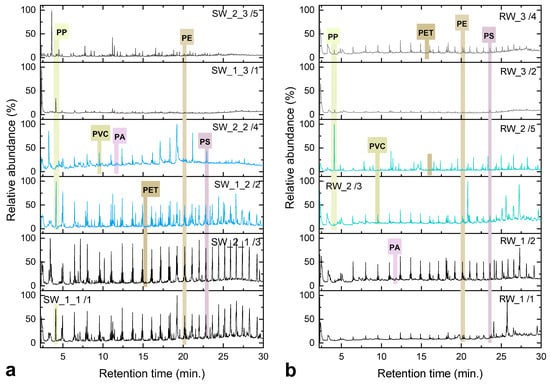

Concerning the influent samples studied within the framework of the present work, stereomicroscopy images (Figure 6a) revealed high morphological diversity (fibers, irregular fragments, thin films, occasional spherical particles), spanning a wide color palette (neutral to vivid). According to Figure 6c, fibers were abundant and constituted the dominant class, consistent with releases from laundering and domestic wastewater; long, flexible, curved fibers (blue/red/neutral colored) often appeared entangled or embedded in aggregates with organic/inorganic residues, signs which are indicative of complex matrices that can shield MPs through pre-treatment and digestion [18]. Angular fragments with sharp/irregular edges were frequent, displaying roughness, cracks, and discoloration, pointing as hallmarks of secondary weathering and abrasion [71]. Semi-transparent films likely originated from packaging and bags were also observed, whereas multicolored MP pieces (including painted and multilayered plastics) could possibly mark the consumer packaging and composite materials as additional sources.

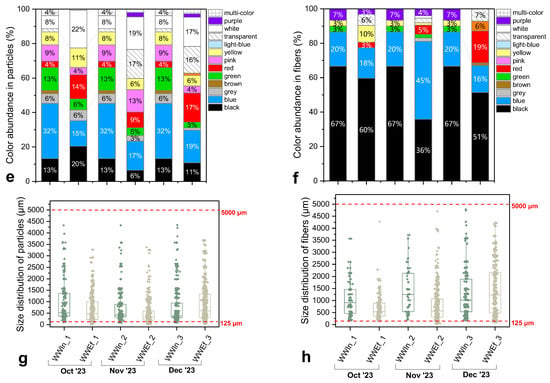

Figure 6.

(a,b) Representative images of suspected microplastics (MPs) observed in (a) influent and (b) effluent samples from the studied wastewater treatment plant (WWTP). (c,d) Concentration of suspected MPs (items/L) in (c) influent and (d) effluent samples, categorized by morphology. (e,f) Color distribution (%) of particles (e) and fibers (f). (g,h) Size distribution of particles (g) and fibers (h) represented by boxplots, illustrating the differences between influent and effluent samples.

MP size distributions of influents (Figure 6g,h) were broad, with a clear enrichment of particles within the 300–1000 µm size range for both fragments and fibers. However, smaller particles (<125 µm) also appeared after digestion, a fact probably consistent with the release from aggregates or biofilms during oxidation processes. The latter fact agrees with previously published reports justifying that wastewater MPs are predominantly <1000 µm, while fibers can span for sizes > 2000 µm [72]. This breadth of sizes underscores multiple sources (encompassing personal care products, textiles, packaging, tire wear, industrial residues, etc.). Influent abundances were also high, ranging from ~78 items L−1 (October) up to ≈200 items L−1 (December), despite modest analyzed volumes (3–5 L), indicating a persistent, diffuse MP burden in incoming flows.

As far as the effluent samples are concerned, they exhibited a marked MP reduction in counts relative to influent samples, evidencing partial removal by the applied treatment processes; nonetheless, all morphology classes (fibers, fragments, films, spherical particles, aggregates) remained detectable, as presented in Figure 6b,d. Fibers still dominated, but with lower frequency and less organic fouling, in line with the literature [26,73,74,75]. Some fibers showed mechanical wear (nicks, fraying), fading, or coiled shapes, constituting as typical signatures of textile-derived MPs traversing WWTPs. Irregular fragments with rough/cracked surfaces persisted (blue/green/white/transparent; frequent dark/black pieces) too; a fact being consistent with inputs from tires, industrial processes, and single-use packaging [72,76]. Transparent films and faded/printed particles also occurred across the studied samples, possibly attributed to packaging and personal-care/consumer products pathways. Moreover, yellowed particles likely reflect additive or specifically pigment alteration during wastewater treatment [70,76,77]. Since treatment chemistry can lead to pigments’ bleaching, inter-stage color comparisons can be misleading; we therefore avoid color-based source apportionment here [78].

Size distributions of the effluent samples were basically detected for sizes 300–1000 µm (medians ~400–600 µm), with occasional outliers > 3000–4000 µm (notably in late autumn–winter period). Additionally, persistence of large fibers and particles suggests imperfect settling, or hitchhiking within residual organic structures. Detectable < 125 µm particles (despite 125 µm sieving) again support post-digestion release from micro-aggregates [79]. Effluent MP abundances ranged between 11–44 items L−1 (maximum values in December), confirming that well-designed plants can still discharge residual MPs [2,15,80].

Overall, the plant substantially reduces MP counts but does not eliminate them. Specifically, larger fractions appear more effectively removed, whereas <300–500 µm classes are comparatively resilient [60]. Residual effluent composition (fiber-rich, weathered fragments, films) is consistent with urban-textile signatures and packaging-related inputs.

3.5. Comparative Analysis of WWTP Influent vs. Effluent—Quantitative Results

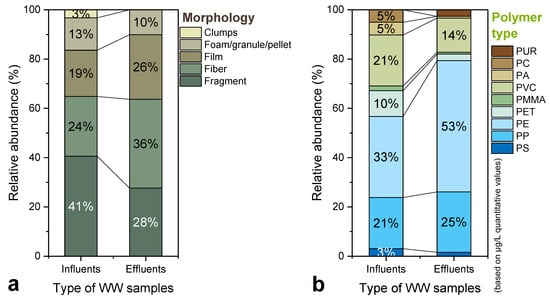

The dataset from the Thessaloniki’s WWTP, covering the period October–December 2023, revealed clear differences between influent and effluent samples, both in concentration levels and in the qualitative characteristics of the suspected MPs. Overall, the comparative evaluation of the samples highlights the degree of treatment efficiency and provides insight into the mechanisms governing MP removal and transformation during wastewater processing.

As depicted in Figure 7a, relative to influent, the effluent exhibited a distinct decline in fragments and aggregates and a relative increase in fibers (≈36%) and films (≈26%), while foams/pellets and clumps were almost entirely absent. This shift suggests selective retention by the treatment stages, which appear to more effectively remove heavier and three-dimensional particles, allowing lighter and filamentous morphotypes to pass through. Colour patterns also differed substantially between the two sample types, with the overall trends outlined in Figure 7c,d. The influent samples showed broad chromatic diversity, with black (≈14%) and blue (≈34%) dominating among particles, while black strongly prevailed among fibres (≈67%). In the effluent, black remained frequent (≈43% of fibres), but blue decreased and neutral tones such as white and transparent increased, which is consistent with pigment bleaching and surface weathering occurring during chemical and biological treatment. Because treatment processes may chemically alter surface pigments and chromophores, such inter-stage color comparisons should be interpreted with caution.

Figure 7.

Comparison of suspected MP characteristics in influent and effluent samples from the WWTP: (a) Relative abundance of morphologies, (b) Relative abundance of polymer types based on mass concentration (μg/L), (c) Color distribution of particle-shaped MPs, (d) Color distribution of fiber-shaped MPs, (e) Size distribution of particles, and (f) Size distribution of fibers. All values are expressed as percentages of the total number of identified MPs within each category.

A clear leftward shift toward smaller particle sizes was observed from influent to effluent, as observed in Figure 7e,f. The 125–500 μm size class increased in the effluent for both particles (from about 24% to 40%) and fibers (from about 22% to 38%), while larger size classes (1000–2000 μm and 2000–5000 μm) diminished considerably after treatment. This pattern is consistent with fragmentation or erosion of larger items within the physical, chemical and biological stages of the WWTP [12,18,81]. Primary and secondary treatment steps typically show higher removal for coarse fractions, allowing finer MPs to dominate the final effluent [24]. Therefore, the enrichment of smaller MPs in the effluent does not necessarily indicate poor performance; rather, it likely reflects the secondary generation of smaller MPs within the plant and the inherently size-selective nature of removal processes.

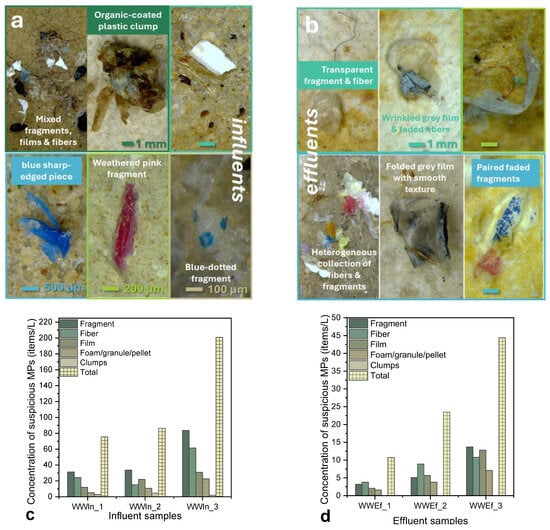

Regarding polymer composition, which is inclusively depicted at Figure 7b, PE, PP, PET and PVC dominated in influent samples and remained the most prevalent polymers in the effluent, with a relative rise in polyolefins (PE and PP) and a decrease in PA and PVC after treatment; trends that mirror international findings. The abovementioned polymers are ubiquitous in household and packaging materials, such as toothpaste tubes, cosmetic containers, beverage bottles, food bags and textiles, supporting a predominantly domestic origin of MPs in municipal wastewaters [17]. Additional sources of PE, PP and PS include the mechanical abrasion of consumer plastics, activities associated with the tire and textile industries, and road dust containing rubber residues [82,83]. Styrenic polymers, such as styrene-butadiene rubber (SBR) and acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), were sporadically detected but not quantified. The persistence of polyolefins after treatment is attributed to their low density (<1 g cm−3) and reduced settling potential, thus favoring their persistence in the final effluent [32,70]. Similar dominance of PE and PP has been reported in German WWTPs [75] and across a global dataset of 121 plants in 17 countries, where PE, PS and PP were the most frequent effluent polymers [68]. Textile-related polymers, including, for instance, PA and PET, were also present in notable proportions, consistent with emissions from synthetic garment washing [84,85]. Some of the most representative TICs for both the influent and effluent studied samples are presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Indicative TICs of random (a) influent and (b) effluent samples from the WWTP, with annotated peaks corresponding to the detected polymers.

Influent concentrations based on particle counts were relatively high, reaching approximately 78 items L−1 in October and up to 200 items L−1 in December, reflecting diverse urban sources such as textiles, industrial residues, personal-care products and stormwater inputs. The corresponding effluent concentrations were lower, between 11 and 44 items L−1 (maximum in December), confirming partial but incomplete removal by conventional treatment processes.

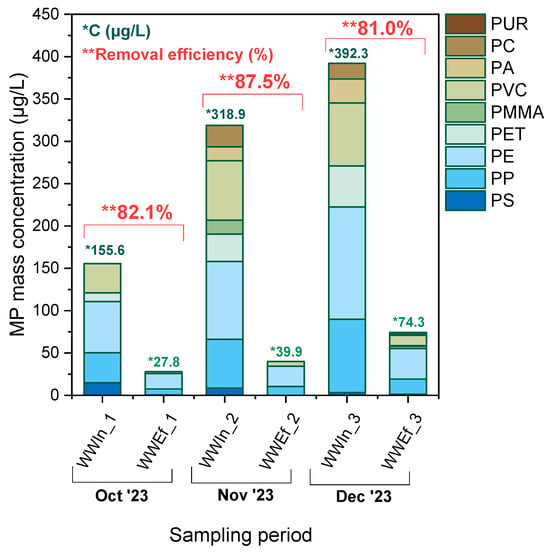

Mass-based quantification using analytical pyrolysis provided additional insight into the polymer load of the samples. Figure 9 summarizes the concentrations (µg L−1) of identified polymers in influent and effluent samples. The removal efficiency (retention capacity) for MPs larger than 125 µm was also calculated as in Equation (2):

where and are the influent and effluent concentrations (in µg L−1), respectively. The maximum total concentration in the influent occurred in December (392.3 µg L−1), followed by November (318.9 µg L−1) and October (155.6 µg L−1). The effluent concentrations for the same months were 74.3, 39.9 and 27.8 µg L−1, respectively, indicating a substantial decrease due to treatment. The calculated removal efficiencies ranged between 81.0% and 87.5%, with the highest recorded values captured in November. Noteworthy is also the fact that these values fall within the range typically reported for conventional WWTPs (≈70–90%) [19,86,87,88].

Figure 9.

Mass concentration of MPs (μg/L) per polymer type in influent (WWIn) and effluent (WWEf) samples from the WWTP during the October–December 2023 period. Removal efficiency values of microplastics are shown in red as percentages.

The variety of polymers remained similar throughout, with PE, PP and PET prevailing in both influent and effluent, consistent with findings from other studies [15,16,53,70,89]. Quantification based on polymer mass, rather than particle count, provides a more representative measure of pollution load, especially for denser or thicker particles that may be underestimated in visual enumeration. The shift from number-based (items L−1) to mass-based (µg L−1) assessment offers a clearer picture of total environmental impact. Reported effluent concentrations in the literature vary widely owing mainly to differences in influent composition, sampling strategy, particle size cut-offs and analytical methodology [32,84]. For instance, Simon et al. (2018b) [58] reported MP values of 0.5–11.9 µg L−1 in WWTP effluents; Barkmann-Metaj et al. (2023a) [90] recorded 0.2–10.8 µg L−1 (mean 3.7 µg L−1) in industrial-park wastewaters, whereas Sanz & Rodríguez (2024a) [32] measured 17 µg L−1 for activated-sludge systems and 10 µg L−1 for membrane bioreactors, demonstrating technology-dependent variability. All these discrepancies underline the need for harmonized MP monitoring protocols, a topic currently under consideration by the European Commission. Furthermore, the heterogeneity of effluent matrices and differences in analytical workflows pose challenges for inter-study comparison and reproducibility [91]. In this study, where the detection limit was set at 125 µm, the data confirm preferential retention of larger MPs during early sedimentation, while smaller fractions escape into the effluent, in agreement with previous observations.

An interesting temporal pattern emerged when considering meteorological conditions. The highest effluent concentration (74.3 µg L−1) was measured in December 2023, coinciding with a period of intense rainfall during the preceding week (mean daily precipitation ≈ 36 mm; cumulative ≈ 61 mm). Previous research has shown that heavy or prolonged rainfall events can lead to increased MP inflows to wastewater systems and elevated effluent concentrations, especially in combined sewer systems where stormwater is channeled together with municipal wastewaters [31,60,92,93]. Such conditions can result in hydraulic overloads that shorten residence time, reduce settling efficiency, and increase turbulence, with these factors collectively enhancing the escape of small particles and fibers. Consequently, the December peak is likely linked to increased urban runoff and partial overloading of the plant, confirming that rainfall intensity is a major driver of temporal variability in WWTP MP emissions. Although higher MP loads were observed following rainfall events, this association should be interpreted qualitatively, as the number of sampling dates does not allow for a statistically robust correlation analysis.

Based on the plant’s average daily discharge of 155,000–160,000 m3 d−1, the measured effluent concentrations correspond to an estimated outflow of approximately 7 × 109 items d−1 or 1.18 × 1010 µg d−1, equivalent to about 4.3 × 1012 µg of MPs released annually into the receiving water body, herein the Thermaic Gulf [26,31]. This estimate underlines the role of the Thessaloniki WWTP as a potential point source of MPs to coastal ecosystems and further emphasizes the need for targeted mitigation measures such as tertiary filtration or advanced polishing technologies.

In summary, the Thessaloniki WWTP achieves substantial MP reduction in both particle counts and polymer mass, with higher removal for coarse and three-dimensional particles, whereas fine fibers and thin films persist in the treated effluent. The observed influent–effluent contrast in size distribution and polymer composition indicates that particles smaller than 300–500 µm remain the most difficult to capture, while polyolefin-rich and buoyant MPs dominate the residual discharge. All the above findings reinforce the importance of integrating mass-based polymer-specific quantification with hydrometeorological context to accurately assess WWTP performance and the downstream flux of MPs to aquatic environments.

4. Discussion

This study presents a comprehensive assessment of MP pollution across three distinct aquatic compartments in Northern Greece: surface seawater from the Thermaic Gulf, surface freshwater from the Axios River, and influent and effluent samples from the Thessaloniki (Sindos) WWTP. For each substrate, three consecutive sampling campaigns were conducted over a three-month period, taking into account the prevailing meteorological conditions. The pre-treatment methodology was adapted to the specific organic load and matrix characteristics of each substrate to ensure optimal isolation of MPs prior to analysis. After organic matter removal, suspected MPs were classified morphologically by stereomicroscopy according to their shape, size, and color, followed by qualitative and semi-quantitative polymer identification using Py–GC/MS based on the optimized protocol developed and in detail described in Supplementary Material, Sections S2 and S3.

The overall results (summarized in Table 1) confirm the widespread presence of MPs in all studied substrates, with variations in morphology, color, size distribution, polymer composition, and concentration levels. Generally, the findings reflect a clear gradient in MP abundance from seawater and river water to wastewater, consistent with the degree of anthropogenic influence in each system.

In surface seawater samples from the Thermaic Gulf, MP concentrations ranged from 1.5 to 4.8 items m−3, representing low-to-moderate pollution levels compared with other Mediterranean sites [22,94]. Fibers and fragments were the dominant morphological types, typically transparent, blue, or black, with particle sizes between 500 and 1000 µm and fibers between 500 and 1500 µm. This size range aligns with typical fragmentation products of larger plastic items via photo-oxidative weathering under marine exposure. The observed polymer spectrum, including mainly PE, PP, and PS, is consistent with dominant sources such as packaging materials, fishing gear, and consumer plastic debris.

In the Axios River samples, MP concentrations estimated microscopically ranged between 0.3 and 2.5 items m−3, whereas Py–GC/MS quantification indicated polymer mass concentrations substantially higher than those in seawater (7.3–56.8 µg L−1). Fibers, primarily black and transparent, were abundant, along with organic aggregates and film-like fragments. The dominance of PE and PP and the presence of PET and PS mirror patterns observed in rivers receiving mixed urban, agricultural, and industrial inputs [53,95]. The Axios River thus acts as a transitional vector linking inland pollution sources to coastal deposition zones, supporting the notion that rivers serve as key conduits of MPs from land to sea.

The highest MP loads were found in wastewater samples from Thessaloniki’s WWTP. Influent concentrations ranged from 75.5 to 200.8 items L−1, with corresponding mass-based concentrations of 155.6–392.3 µg L−1, whereas effluent concentrations dropped to 10.7–44.4 items L−1 and 27.8–74.3 µg L−1, respectively. These data indicate removal efficiencies of 81–87.5%, comparable to values reported for European WWTPs [32,90,96]. However, a shift toward smaller particle size classes was observed post-treatment, with an increased proportion of the 125–500 µm fraction, possibly due to fragmentation and mechanical stress during aeration and filtration. This shift toward smaller size classes in the effluent, together with the decrease in overall polymer mass, is consistent with size-selective retention and potentially partial size reduction during treatment, although it does not constitute direct evidence of fragmentation within the WWTP [97]. In the effluent, PE, PP, and PS were dominant, followed by minor fractions of PET and PVC, supporting the inference that domestic and urban wastewater remains the primary source of MPs entering treatment systems.

The correlation with meteorological conditions revealed a significant influence of rainfall on MP concentrations. December, the wettest sampling month (total precipitation: 61 mm), coincided with the highest influent and effluent loads. In combined sewer systems such as that of Thessaloniki, stormwater inflow increases the hydraulic load, shortens residence times, and reduces sedimentation efficiency, promoting MP passage through treatment [31,60,92,93]. These findings highlight the importance of hydrological events in regulating MP fluxes and stress the need to incorporate seasonal meteorological data into monitoring frameworks. It is necessary to highlight that the apparent increase in MP abundance during periods of higher rainfall should be considered an inferred trend rather than a quantified relationship, given the limited temporal resolution of the dataset.

Morphologically, fibers were the most prevalent category across all substrates, a finding consistent with global studies identifying fibers as the dominant MP type in aquatic environments [12,98]. Their ubiquity can be attributed to textile washing, domestic effluents, and abrasion of synthetic materials. The most frequent colors, recorded as transparent, black, and blue, reflect typical sources such as packaging films, synthetic textiles, and fishing gear. The occurrence of multi-colored or printed fragments, occasionally observed under the microscope, suggests contributions from consumer packaging and personal care products (PCCPs). However, source interpretations presented within this study remain qualitative and refer to broad activity categories, including for instance urban wastewater inputs, packaging materials, aquaculture residues. The aforementioned associations are intended as indicative rather than definitive, since color and polymer identity do to apply for explicit source appointing without additional data.

From a comparative standpoint, the mass-based MP concentrations derived from Py–GC/MS (ranging from a few µg L−1 in seawater to several hundred µg L−1 in WWTP influent) provide a more integrated measure of plastic pollution load than particle counts alone. The methodological integration of stereomicroscopic identification and pyrolytic polymer characterization enabled both morphological and chemical validation of results, enhancing confidence in cross-matrix comparisons. The overall pattern, incorporating increasing MP load along the land–sea continuum (WWTP > river > sea), underscores the interconnectedness of anthropogenic activity, wastewater management, and environmental contamination pathways.

Collectively, the results demonstrate that MPs are omnipresent in aquatic systems of Northern Greece and that WWTPs, despite achieving substantial removal, remain major point sources of fine, buoyant, and polyolefin-rich particles to receiving waters. The observed influence of rainfall further suggests that episodic overflows and urban runoff play a decisive role in regulating temporal variability in MP emissions. The Axios River and WWTP effluents constitute the main upstream inputs to the Thermaic Gulf, and the recurring presence of similar dominant polymers across the three matrices is consistent with this hydrological and anthropogenic linkage. Together, these observations support the interpretation of a connected land–river–sea continuum, even though the current dataset does not allow a quantitative source-apportionment. Although a full ecological or socio-economic assessment is beyond the scope of this monitoring-based study, the findings have several potential implications for the Thermaic Gulf. The presence of MPs in surface waters of an area hosting extensive mussel farming raises questions about possible exposure pathways for filter-feeding organisms, while the broader fisheries sector suggests relevance for seafood-consuming populations. The predominance of buoyant polymers also indicates that a proportion of particles may eventually accumulate in nearshore or benthic zones following weathering and biofouling, which could influence habitats of commercial species. All these aspects are highlighted here only as qualitative considerations, as more detailed organism-level, sediment-focused, and economic studies would be required to evaluate actual risks and would be valuable for future studies within the region.

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Perspectives

The present study delivers an integrated, multi-tiered assessment of MP pollution across three hydrologically connected matrices, namely river water of Axios, coastal seawater from Thermaic Gulf, and wastewaters from a municipal WWTP in Thessaloniki, representing an aquatic system under high anthropogenic pressure in northern Greece, where relevant data are scarcely reported.

Herein, the combination of stereomicroscopic characterization and CaCO3-assisted Py–GC/MS analysis provided both morphological and compositional insights into MP occurrence. According to stereo-microscopy observations, MP concentrations ranged from 0.5 to 2.5 items m−3 in river water, 1.5 to 4.8 items m−3 in seawater, and 75.5 to 200.8 items L−1 in WWTP influent, with an average removal efficiency of approximately 85% in the treatment process. Despite this retention, MPs were still present in the WWTP effluent (10.7–44.4 items L−1), confirming partial downstream redistribution to the receiving aquatic environment. Chemical characterization revealed that polyolefins (PE, PP) dominated all sample types, reflecting their widespread consumer use and persistence, while PET, PVC, PS, and PA were also detected, particularly in the WWTP and river samples, indicating urban and domestic inputs. Concerning the developed Py–GC/MS methodology, it was optimized and validated with CaCO3 as a catalytic agent, and enabled sensitive, selective, and reproducible identification and quantification of these polymers, even in complex matrices with high organic loads.

While this study offers a first integrated view of MPs across three connected aquatic systems, several practical considerations should be kept in mind when interpreting the results and for future directives. Firstly is the volumes of sampled water that could be collected and processed differed between the matrices, which inevitably affects the absolute concentrations reported and may limit direct cross-comparison. Additionally, the mesh size used during sampling (100–125 µm) could lead to the release of smaller particles that were not captured, and the dataset should therefore be viewed as representative of the larger MP fraction. The use of different mesh sizes across matrices (100 µm for seawater and 125 µm for river and wastewater samples) represents an inherent limitation of the study, as even small differences in size cutoffs may result in the loss of smaller MP particles and affect quantitative comparability. Although the oxidative digestion protocol was selected for its effectiveness in removing organic material, it is possible that very fragile or heavily weathered particles were partly altered during treatment. Finally, in the river samples, density separation was used only when the suspended material made it necessary, which may introduce some variation within this subset. It has to be highlighted that these aspects do not change the overall interpretation of the spatial and compositional patterns we report, but they do provide useful context for understanding the scope of the study and for guiding future monitoring designs in the region. To conclude, this integrated approach highlights the power of multi-parametric monitoring, combining morphological and molecular-level evidence to unravel the sources, transport pathways, and environmental fate of MPs. The findings provide essential baseline information for understanding pollution dynamics and further improving WWTP management, which functions both as a significant sink and a secondary source of MPs. Beyond the MP scale, future research should focus on extending this analytical framework toward the detection and quantification of NPs, which represent the final fragmentation stage of larger plastics and remain largely unexplored due to analytical limitations. The pretreatment and Py–GC/MS workflow demonstrated here, which are already capable of selective polymer identification in complex matrices, provide a scalable methodological basis for such downscaling. In this frame, adapting this workflow to NPs will enable a more complete assessment of the plastic degradation continuum and strengthen future environmental monitoring and risk-assessment strategies. At the same time, the study underscores the urgent need for standardized, scientifically validated protocols covering all stages of MP assessment, ranging from sampling and pre-treatment to chemical analysis, aiming to enhance data comparability across studies and to support the development of robust regulatory frameworks and effective mitigation strategies for MP pollution in aquatic environments.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16020772/s1. Section S1: Sampling and pre-treatment details. Table S1. Summary of sampling details for the collected aquatic environmental samples; Figure S1. Pre-treatment stages of real aqueous samples applied in the laboratory for MP isolation. Section S2: Py–GC/MS methodology and reference materials. Table S2. List of reference polymers used for Py–GC/MS method development. Table S3. Concentrations of reference polymers in standard solutions A, B, and C. Table S4. Analytical conditions for Py–GC/MS analysis. Table S5. Characteristic pyrolysis products and representative ions for the nine studied polymers. Section S3: Py–GC/MS method performance and interactions. Figure S2. EGA pyrogram of CaCO3. Figure S3. Pyrograms of the PE-PP mixture with and without the addition of CaCO3. Figure S4. Catalyst effect on the pyrograms of PS, PVC, PA, and PMMA. Figure S5. Effect of the catalyst on the pyrograms of PET, PC, and PU polymers. Figure S6. Catalyzed reactions of PET, PU, and PC pyrolysis products leading to the formation of characteristic compounds BP, MDA, and IPP, which serve as marker compounds for the quantification of the respective polymers. Figure S7. Pyrogram of the complete mixture containing the nine studied polymer standards. The peaks corresponding to the characteristic pyrolysis products of each compound are highlighted. Table S6. Calibration parameters for the studied polymers, including R2 values, LOD, LOQ, and RSD% (n = 3); Figure S8. m/z spectra of the characteristic pyrolysis products selected for quantification. Table S7. Qualitative and quantitative results for polymer mixtures. The detected polymer amounts, as determined from the calibration curves, along with the identification probability provided by the F-Search software, are presented. Section S4: Literature data concerning MP occurrence in aqueous substrates. Table S8. Overview of reported MP concentrations in the Mediterranean Sea. Table S9. Summary of studies reporting MP abundance in European river systems. Table S10. Summary of previous studies reporting the occurrence and concentrations of MPs in WWTPs. The reported size range corresponds to the dominant fraction of MPs detected.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.A.L. and D.N.B.; methodology, N.M.A.; validation, N.M.A. and D.A.L.; formal analysis, N.M.A.; investigation, N.M.A.; resources, D.N.B. and D.A.L.; data curation, N.M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, N.M.A.; writing—review and editing, D.A.L. and D.N.B.; visualization, N.M.A., D.N.B. and D.A.L.; supervision, D.A.L. and D.N.B.; project administration, D.A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.