Abstract

Stone cultural relics are primarily composed of sandstone, a water-sensitive rock that is highly susceptible to deterioration from environmental solutions and dry-wet cycles. Sandstone pagodas are often directly exposed to natural elements, posing significant risks to their preservation. Therefore, it is crucial to investigate the performance of sandstone towers in complex solution environments and understand the degradation mechanisms influenced by multiple environmental factors. This paper focuses on the twin towers of the Huachi Stone Statue in Qingyang City, Gansu Province, China, analyzing the changes in chemical composition, surface/microstructure, physical properties, and mechanical characteristics of sandstone under the combined effects of various solutions and dry-wet cycles. The results indicate that distilled water has the least effect on the mineral composition of sandstone, while a 5% Na2SO4 solution can induce the formation of gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O). An acidic solution, such as sulfuric acid, significantly dissolves calcite and diopside, leading to an increase in gypsum diffraction peaks. Additionally, an alkaline solution (sodium hydroxide) slightly hydrolyzes quartz and albite, promoting calcite precipitation. The composite solution demonstrates a synergistic ion effect when mixed with various single solutions. Microstructural examinations reveal that sandstone experiences only minor pulverization in distilled water. In contrast, the acidic solution causes micro-cracks and particle shedding, while the alkaline solution results in layered spalling of the sandstone surface. A salt solution leads to salt frost formation and pore crystallization, with the composite solution of sodium hydroxide and 5% Na2SO4 demonstrating the most severe deterioration. The sandstone is covered with salt frost and spalling, exhibiting honeycomb pores and interlaced crystal structures. From a physical and mechanical perspective, as dry-wet cycles increase, the water absorption and porosity of the sandstone initially decrease slightly before increasing, while the longitudinal wave velocity and uniaxial compressive strength continually decline. In summary, the composite solution of NaOH and 5% Na2SO4 results in the most significant deterioration of sandstone, whereas distilled water has the least impact. The combined effects of acidic/alkaline and salt solutions generally exacerbate sandstone damage more than individual solutions. This study offers insights into the regional deterioration characteristics of the Huachi Stone Statue Twin Towers and lays the groundwork for disease control and preventive preservation of sandstone cultural relics in similar climatic and geological contexts.

1. Introduction

As crucial components of cultural heritage, stone relics embody and transmit human history and culture [1,2]. These relics primarily consist of stone pagodas, grottoes, and carved stones, which are widely distributed, possess a long history, and hold significant value [3,4]. Common materials used in the construction of stone relics include sandstone, granite, limestone, and marble [5,6]. Among these, sandstone—which is mainly composed of quartz, feldspar, and calcite—has a broad geographical distribution. With its medium-soft hardness, adaptability to various carving techniques, rich natural tones, and granular texture, sandstone has become the preferred material for stone cultural relics [7,8].

As a typical water-sensitive rock, sandstone is particularly vulnerable to the effects of environmental solutions [9]. Sandstone features a naturally interconnected network of primary pores and secondary cracks, created by weathering, erosion, and tectonic activity. Aqueous solutions can penetrate the rock quickly through capillary action, osmotic pressure, and gravity. These solutions not only fill the pore spaces but also interact with the mineral composition and cementing materials of sandstone, leading to mineral dissolution, hydration expansion, and irreversible microstructural rearrangement [10]. Consequently, sandstone cultural relics are often subjected to erosion from various aqueous sources, and their impacts should not be underestimated [11].

Moreover, acidic components in these solutions primarily dissolve the cementing materials in sandstone, weakening the cohesive forces between particles, loosening the structure, and inducing cracks. In contrast, alkaline substances can cause clay minerals to expand and partially decompose, compromising the overall structural stability. Soluble salts are a major cause of damage to sandstone cultural relics. They mainly come from two sources: natural sources (like rain, groundwater) and human activities (like industrial pollution and historical conservation treatments) [12]. The salts are transported within the stone by water infiltration, capillary action, and wet-dry cycles. They accumulate at evaporation fronts and other areas of frequent moisture movement, which predisposes the stone to salt damage [13]. On a microstructural scale, salt crystallization and environmental cycling (dry-wet/freeze–thaw) alter sandstone. Crystallizing salts clog pores, reduce permeability, and generate microcracks along grains and cement. This process ultimately leads to grain detachment and the coalescence of microcracks into larger fractures [14]. The presence of acidic, alkaline, and soluble salts can significantly diminish the mechanical properties of sandstone, severely jeopardizing the safety of cultural relics [15,16].

The outdoor environment, especially the dry-wet cycles induced by temperature and humidity changes, can also adversely affect sandstone performance, threatening the stable preservation of these cultural relics [17]. During dry-wet cycles, the morphology and content of cemented and clay minerals in sandstone continue to change. These cycles contribute to the gradual formation of honeycomb pores within the sandstone, leading to the development of internal cracks that progress from a dispersed distribution to penetrating shear bands [18]. Additionally, the wetting-drying cycle facilitates the continuous migration, crystallization, and dissolution of solutions, aggravating the formation and propagation of pore cracks in sandstone. The combination of dry-wet cycles and erosive solutions results in synergistic damage and further deterioration [17].

As distinctly independent artificial structures, sandstone pagodas encapsulate a variety of advanced techniques characteristic of ancient stone relics [19]. However, these pagodas are frequently exposed to the natural environment and are impacted by the synergistic effects of multiple solutions and dry-wet cycles. Outdoor precipitation and humidity greatly influence the stone pagoda, as moisture directly interacts with the pagoda’s structure. Consequently, the pH value and chemical composition of precipitation and water can lead to the deterioration of sandstone pagodas; simultaneously, the outdoor dry-wet cycles exacerbate the effects of precipitation and aqueous solutions, resulting in irreversible damage [20].

Although extensive research has been conducted both domestically and internationally on water erosion, the deterioration of stone cultural relics, and related issues [21,22,23], previous studies have often inadequately addressed the multi-factor synergistic effects prevalent in natural environments, rendering it challenging to accurately reflect the actual deterioration of cultural relics. Additionally, there is a scarcity of research focusing on the deterioration of stone pagodas in complex solution environments and natural conditions.

In light of the above considerations, this paper investigates the Huachi Stone Statue Twin Towers in Qingyang City, Gansu Province, as a case study. Based on the actual environmental conditions surrounding the Stone Statue Twin Towers, a series of synergistic dry-wet cycle tests were conducted. The chemical composition, surface/microstructure, physical properties, and mechanical characteristics of sandstone specimens subjected to dry-wet cycles were analyzed, allowing for an investigation into the damage and deterioration patterns of sandstone under environmental stress. This research aims to explore the regional characteristics of the Huachi Stone Statue Twin Towers and provide a scientific basis for disease control and preventive protection of sandstone pagodas in analogous areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

The Shuangta Pagoda of Stone Statues in Huachi County was constructed during the Jin Zhenglong and Dading reigns (1156–1189). Initially, it was situated at the confluence of Shuangtagou and the Baozichuan River in Zhangcha Village, Linzhen Township, Huachi County, Qingyang City, Gansu Province (see Figure 1). In September 2001, the pagoda was relocated to Dongshan Forest Park in Huachi County, Qingyang City.

Figure 1.

The original and current site of Huachi Stone Statue Twin Towers.

The geological strata in the vicinity of the tower belong to the K1h of the Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous Huanhe Formation. The lithology of this strata is characterized by calcareous, cemented fine-grained feldspathic sandstone, which is known to be easily weathered [11].

According to the annual reports of Gansu Province, the county annals of Huachi County, and relevant weather forecast records, the area where the Huachi Stone Statue Twin Towers are located experiences a temperate continental climate, characteristic of a seasonal frozen soil zone. Winters are cold, while summers are hot and rainy. This region exhibits a significant annual temperature variation, with extreme high temperatures reaching 38 °C and extreme lows dropping to −26.5 °C. The average daily maximum temperature difference is recorded at 16.6 °C, with a maximum difference of 26.1 °C. Relative humidity reaches a daily maximum of 100%, with an average relative humidity of 62%.

Annual precipitation in this region totals approximately 500 mm, with a monthly average of 41.67 mm. The highest recorded average pH value of precipitation is 8.0. Notably, acid rain occurs between August and November, with pH values ranging from 4.8 to 5.6 [24]. The region benefits from about 2300 h of annual sunshine, and the average evaporation rate is around 1450 mm. The significant seasonal fluctuations in temperature and rainfall patterns—as well as the high evaporation rate—pose a risk for the deterioration and damage of the stone statue twin towers due to the combined effects of precipitation and dry-wet cycles.

Rainwater and winter snow samples from the vicinity of the Huachi Stone Statue Twin Towers were collected, and their characteristics were analyzed using an ion chromatograph and a pH tester. The ion composition, concentrations, and pH of the precipitation were evaluated. The findings revealed that the pH of winter snow samples was 5.6, while that of rainwater samples was 5.4. The analysis further identified that the dominant ions in the precipitation include Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+ and SO42− (the main cation is Na+).

2.2. Material

2.2.1. Rock Samples

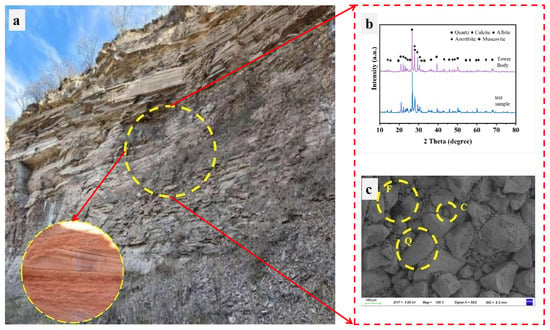

This study selected undisturbed red sandstone from the original site of the Huachi Stone Statue Twin Towers, located in Baozichuan, Linzhen Township, Huachi County, Qingyang City, Gansu Province, as the sampling site (see Figure 2a). The collected red sandstone samples appeared reddish-brown in their wet state and exhibited low levels of sedimentary impurities. To ensure the rock samples were representative of the materials used in the twin towers, we conducted analyses of their chemical composition, physical properties, and microstructure.

Figure 2.

Characterization of the red sandstone. (a) Field outcrop near the Huachi Twin Towers, showing the sampling location (circled). (b) XRD patterns of the tower stone and a laboratory sample. (c) SEM image illustrating the granular framework and pore structure, with key components labeled: quartz (Q), feldspar (F), and calcite cement (C).

Figure 2b and Table 1 present the X-ray diffraction (XRD) and X-ray fluorescence (XRF) test results for both the rock samples and fragments from the Huachi Stone Statue Twin Towers.

Table 1.

XRF of rock samples and tower body samples.

XRD mineral analysis results show:

Main components: Quartz, feldspar (including plagioclase and alkali feldspar), and calcite.

Minor components: Mica and clay minerals.

Trace components: Diopside and dolomite.

Notably, the samples have broadly similar major-element compositions. Variations in SiO2, Al2O3, and especially CaO are due to differences in carbonate binder content and weathering.

Physical property tests revealed that the rock samples possess a porosity of 10.56%, a water absorption rate of 5.03%, and a saturated water absorption of 6.86%. Figure 2c illustrates the microstructure of the rock samples, which show no significant pore development, indicating a compact structure.

The Huachi Stone Statue Twin Towers are located in Huachi County, Gansu, at the edge of the Loess Plateau. The area’s bedrock is Mesozoic red sedimentary rock, mainly sandstone with some siltstone and mudstone layers. Its well-developed bedding patterns point to an ancient river and lake depositional environment.

The building stones of the twin towers were sourced from the local red sandstone. No intrusive rocks, contact-metamorphic zones, or outcrops of high-grade metamorphic rocks (like gneiss) are found near the site. Petrographic analysis confirms the stone has a typical clastic texture, composed of quartz and feldspar grains held together by carbonate and clay cement. Minor amounts of diopside and dolomite detected by XRD are simply accessory minerals and do not indicate a skarn origin for this sandstone.

2.2.2. Solution Selection

To simulate the aqueous environment (ion distribution, ion content, and pH) at the site of the Huachi Stone Statue, several solutions were prepared: a Na2SO4 solution, acidic solutions at pH 4 and 6 (using H2SO4), and an alkaline solution at pH 8 (using NaOH). Additionally, to assess the combined effects on the tower structure, composite solutions were prepared by adding 5% Na2SO4 to each of the acidic and alkaline solutions (i.e., pH 4, 6, and 8 + 5% Na2SO4).

All solutions were prepared using distilled water as the solvent. Analytical-grade reagents were used throughout:

- Na2SO4 (white powder, density: 2.68 g/cm3, melting point: 884 °C, boiling point: 1404 °C) was used to prepare the salt solution.

- Concentrated H2SO4 (colorless, odorless, transparent oily liquid, concentration: 98%, density: 1.84 g/cm3, melting point: 10.31 °C, boiling point: 337 °C) was used to prepare the required acidic solutions.

- NaOH (white, odorless, translucent pellets, density: 2.13 g/cm3, melting point: 318 °C, boiling point: 1388 °C, highly soluble in water) was used to prepare the alkaline solution.

All chemicals (Na2SO4, H2SO4, and NaOH) were supplied by Tianjin Damao Chemical Reagents Partnership (Tianjin, China).

2.3. Specimen Preparation

2.3.1. Rock Sample Preparation

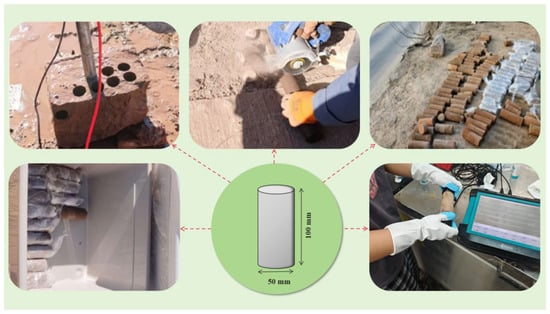

In accordance with the relevant standards of the International Society of Rock Mechanics (ISRM) [25], cylindrical rock specimens with dimensions of 50 mm in diameter and 100 mm in height were prepared from the sampling site. To minimize anisotropy, the preparation followed a five-step procedure: coring, cutting, grinding, flatness inspection, and wave velocity measurement.

The specific sampling steps are illustrated in Figure 3:

Figure 3.

Preparation process of rock samples.

- Coring: A handheld core drilling machine equipped with a 50 mm × 450 mm diamond drill bit was used to extract cylindrical samples from the rock mass.

- Cutting: The irregularly shaped cores were cut to a uniform height of 100 mm using a rock cutting machine.

- Grinding: The two end surfaces of each cylinder were ground flat using an angle grinder. The final surface roughness and deviation from perpendicularity to the cylinder axis were controlled to be less than 0.05 mm and 0.25°, respectively.

- Flatness Inspection: The flatness and parallelism of the end surfaces were verified.

- Wave Velocity Test: The P-wave velocity of each prepared specimen was measured using a Haichuang Gaoke HC-F800 (Beijing Haichuang High Tech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) comprehensive tester. Specimens with similar wave velocities were selected for subsequent testing to ensure consistency.

2.3.2. Solution Preparation

The following solutions were prepared: distilled water, 5% Na2SO4, H2SO4 (pH = 4, 6), NaOH (pH = 8), H2SO4 (pH = 4, 6) + 5% Na2SO4, and NaOH (pH = 8) + 5% Na2SO4. The specific compositions and quantities of materials used for each solution are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Solution composition and material dosage.

- 5% Na2SO4 Solution: Anhydrous Na2SO4 powder was directly weighed, stirred into distilled water, and dissolved to a final volume of 1 L.

- H2SO4 Solutions (pH = 4, 6): For each, 1 L of distilled water was measured, and concentrated H2SO4 was added dropwise under continuous monitoring with a pH meter until the target pH was achieved.

- NaOH Solution (pH = 8): 1 L of distilled water was measured, and NaOH pellets were added under pH meter monitoring until the target pH of 8 was reached.

- Composite H2SO4 (pH = 4, 6) + 5% Na2SO4 Solutions: For each, anhydrous Na2SO4 powder was first weighed and dissolved in 1 L of distilled water. Concentrated H2SO4 was then added dropwise to this solution under pH meter monitoring to adjust to the target pH.

- Composite NaOH (pH = 8) + 5% Na2SO4 Solution: Anhydrous Na2SO4 powder was first weighed and dissolved in 1 L of distilled water. NaOH pellets were then added to this solution under pH meter monitoring to adjust the pH to 8.

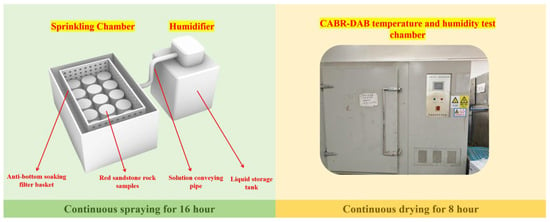

2.4. Dry-Wet Cycle Conditions

To simulate the characteristic dry-wet deterioration of the Huachi Stone Statue towers under local climatic conditions, a specific dry-wet cycle regime was designed. Each cycle consisted of continuous solution spraying for 16 h, followed by continuous drying for 8 h.

Rock samples were subjected to 0 (control), 25, 50, 75, and 100 dry–wet cycles using each of the solutions listed in Table 2: distilled water, 5% Na2SO4, H2SO4 (pH = 4 and 6), NaOH (pH = 8), H2SO4 (pH = 4, 6) + 5% Na2SO4, and NaOH (pH = 8) + 5% Na2SO4. After the prescribed cycles, the apparent morphology, microstructure, physical properties, and uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) of the specimens were tested. The cycle numbers (0, 25, 50, 75, and 100) were selected to provide an initial baseline (0 cycles) and to capture progressive deterioration at representative intervals while keeping a practical balance between experimental resolution and workload [26]. The experimental scheme and cycle numbers are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Dry-wet cycle scheme and numbering.

The spraying phase was conducted in a custom-built precipitation simulation chamber, consisting of a humidifier and a spray chamber (internal dimensions: 180 mm × 260 mm × 150 mm). To simulate the monthly precipitation at the site, the chamber’s water consumption was calibrated to 1.95 L per 16 h spraying period. Following spraying, samples were transferred to a CABR-DAB temperature and humidity test chamber for the 8 h drying phase. The drying temperature was set to 45 °C based on local extreme high-temperature records. The dry-wet cycle experimental setup is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Dry-wet cycle device.

2.5. Test Methods

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was conducted on rock samples after 100 dry-wet cycles, following ISO 22278:2020 [27], using a D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer (Brooke (Beijing) Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). Prior to testing, samples were pulverized and sieved through a 200-mesh (75 μm) sieve, then pressed into tablets. The scanning range was 10° to 80° (2θ) at a speed of 10°/min.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed in accordance with ISO 16700:2015 [28] to characterize the microstructure of the red sandstone, using a ZEISS Sigma 360 scanning electron microscope (Beijing Ruike Zhongyi Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). For SEM observation, approximately 1 cm-sized sample fragments were coated with a 10 nm gold film and imaged at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV. Apparent morphology was observed using a Zeiss stereomicroscope (Beijing Ruike Zhongyi Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), as per the industry standard SY/T 5913-2012 [29].

The water absorption rate (W) of cycled samples was determined by the free immersion method, according to the national standard GB/T 50266-2013 [26]. First, samples were oven-dried at 105 °C to obtain their dry mass (m1). Subsequently, the dried samples were immersed in water in a stepwise manner: water was added to 1/4, 1/2, 3/4, and finally the full height of the specimen after 2, 4, 6, and 48 h of total immersion, respectively. The saturated mass (m2) was then measured after 48 h. Water absorption was calculated using Equation (1):

Porosity was measured using a Macro-SP nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) instrument (Suzhou Newmai Analytical Instrument Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China) to investigate the effect of dry-wet cycles on the pore structure of the sandstone [30]. The NMR parameters were as follows: sampling frequency of 100 kHz, main frequency of 12 MHz, RF delay of 0.02 ms, sampling points of 1024, and a waiting time of 3000 ms. Each sample was tested three times, and the average value was taken.

The P-wave velocity was measured using the pulse-echo method with a Haichuang High-tech HC-F800 comprehensive tester to assess the internal compactness and deterioration level of the sandstone after cycling. The test emission frequency was 54 kHz, with a sampling accuracy of 0.1 μs.

Uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) tests were performed on standard cylindrical sandstone samples after dry-wet cycling using a HYE-300B microcomputer electro-hydraulic servo pressure testing machine (loading rate: 0.1 kN/s). The tests were conducted in accordance with both the ISRM standard [25] and the national standard GB/T 50266-2013 [26,31] to study the mechanical property degradation under cyclic conditions.

3. Results and Discussion

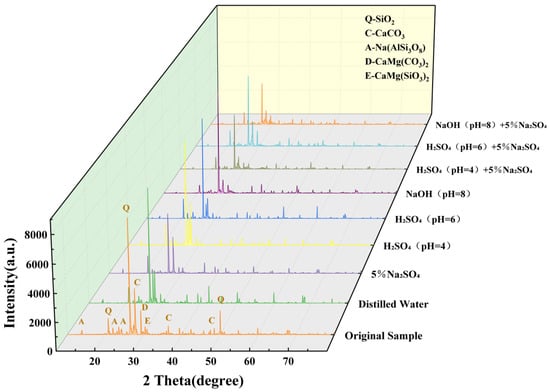

3.1. Chemical Composition

Figure 5 presents the XRD patterns of rock samples subjected to 100 dry-wet cycles in different solutions. The main mineral components of the pristine sample are identified as quartz (SiO2), calcite (CaCO3), plagioclase (including albite, Na(AlSi3O8)), diopside (CaMg(SiO3)2), dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2), and a trace amount of clay minerals. After 100 dry-wet cycles, the diffraction peak intensities of quartz (SiO2) in samples treated with different solutions show a decreasing trend. In contrast, the diopside peaks remain relatively stable.

Figure 5.

XRD pattern of rock samples after dry-wet cycle.

By comparing the XRD patterns of rock samples after dry-wet cycles of different solutions, it is found that the solution type directly affects the chemical composition of rock samples after dry-wet cycles. When the solution is distilled water, the rock sample’s chemical composition is close to that of the original sample, and the peak strength decreases only slightly. This may be because some soluble substances dissolve in water during the dry-wet cycle. When the solution is 5% Na2SO4, the chemical composition of the rock sample changes slightly after the dry-wet cycle. It is mainly due to a slight weakening in the diffraction peak intensities of quartz and feldspar, as well as the emergence of gypsum secondary peaks. This is due to the reaction between the SO42− ion in Na2SO4 and the calcium in the rock sample, which produces gypsum and other products [32].

When the solution is H2SO4, the chemical composition of the rock sample is obviously dissolved, the intensity of the characteristic peak of quartz is obviously weakened, and the diffraction peak of diopside almost disappears. At the same time, the secondary diffraction peaks of gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O) were significantly enhanced. This is due to the reaction of H+ in H2SO4 solution with carbonate binder (CaCO3, etc.) in rock samples, resulting in the dissolution of binders (see Formula (2)). SO42− in acidic solution also reacts with calcareous and quartz in rock samples to form gypsum (see Formula (3)) and silica gel (see Formula (4)). It is worth noting that the acidic environment also dissolves diopside (see Formula (5)), which is why the diopside peak weakens [33].

When the solution is NaOH, the diffraction peaks of quartz and albite in XRD are slightly weakened, and the diffraction peaks of calcite show an increasing trend. This is because quartz and feldspar (such as albite) will slowly hydrolyse with OH to form soluble sodium silicate (Na2SiO3) (see Formula (6)) and sodium aluminate (NaAlO2) (see Formula (7)). However, due to the slow reaction between NaOH solution and rock samples under dry-wet cycle conditions, the XRD characteristic peaks of soluble products (sodium silicate, sodium aluminate) are weak. At the same time, the alkaline environment inhibits the dissolution of calcite and even promotes the precipitation of new calcite by the combination of a small amount of Ca2+ in the solution and CO2 in the air, resulting in the enhancement of the diffraction peak of calcite [34].

When a composite solution of acid/alkali and salt is used, SO42− in the salt solution will interact with the ions in the acid-base solution. When H2SO4 +5% Na2SO4 solution is used, H+ will strongly dissolve the calcite in the rock (see Formula (2)), resulting in the weakening of the calcite diffraction peak; at the same time, H+ will destroy the silicate crystal structure of quartz (see Formula (4)) and feldspar (see Formula (8)), damage the lattice integrity of quartz, and significantly reduce the diffraction peak intensity. However, Ca2+ produced by calcite dissolution will react rapidly with SO42− provided by the superposition of H2SO4 and Na2SO4 to form gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O), so strong secondary peaks appear in gypsum.

When the solution is NaOH + 5% Na2SO4, NaOH slowly hydrolyzes quartz (see Formula (6)), so the peak is weakened. SO42− in the solution will combine with a small amount of Ca2+ dissolved in calcite to form gypsum, but the amount of Ca2+ released is small, resulting in only a weak secondary peak in gypsum. At the same time, SO42− in the solution will also react with diopside, feldspar, and clay minerals to form ettringite (see Formula (9)). It is worth noting that the alkaline environment inhibits calcite dissolution, thereby enhancing the calcite diffraction peak.

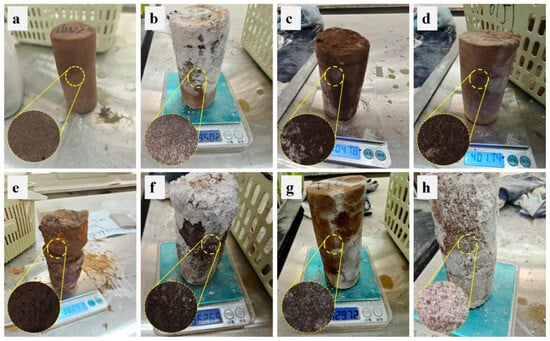

3.2. Appearance

Figure 6 shows the apparent morphology of rock samples in different solutions after 100 dry-wet cycles. Compared with the original samples, the edges of the rock samples after dry-wet cycles show a certain degree of powdering and passivation, accompanied by a decrease in gloss. The surface of the rock sample is passivated and rough because, during the dry-wet cycle, water within the rock sample gradually evaporates outward, forming a humidity gradient. The rock surface becomes embrittled under capillary action, gradually changing from smooth to rough [35].

Figure 6.

Morphology of rock samples after dry-wet cycles: (a) distilled water; (b) 5%Na2SO4; (c) H2SO4 (pH = 4); (d) H2SO4 (pH = 6); (e) NaOH (pH = 8); (f) H2SO4 (pH = 4) + 5%Na2SO4; (g) H2SO4 (pH = 6) + 5%Na2SO4; (h) NaOH (pH = 8) + 5%Na2SO4.

As shown in Figure 6a, after the dry-wet cycle of the pure aqueous solution, the rock sample surface showed only slight powdering, with no white salt frost. As can be seen from Figure 6b, under the action of 5% Na2SO4, obvious powdering and crusting phenomena appeared on the surface of the rock sample, and a large amount of salt frost (Na2SO4 and CaSO4) was distributed on the surface; it was observed through a Zeiss microscope that the pores were also filled with a large number of salt crystals. It can be seen from Figure 6c to Figure 6d that, under the action of acidic sulfuric acid solution, continuous micro-notches and severe pulverization appeared on the surface of the rock sample, and particles at the edges were severely detached. As shown in Figure 6e, under the action of the alkaline NaOH, layered peeling, radial splitting, and obvious shell formation occurred on the rock sample’s surface, and a large amount of white, powdery material that did not fall off accumulated beneath the shell layer. It is worth noting that the bad morphology of rock samples under alkaline solutions lies between that under acidic and salt solutions, and salt frost and lamellar spalling are not as obvious as in salt solutions.

The changes in the composite solution of acid/alkali and salt reflect the changes in each solution. Due to interactions among various ions, the rock samples’ surfaces exhibit salt frost and crust formation, and the internal pores are filled with a large number of salt crystals (Figure 6f–h). Moreover, the alkaline compound salt solution caused the most obvious deterioration of the sample, with salt frost and peeling covering almost all parts of the specimen.

During the dry-wet cycles, SO42− in the solution migrates towards the specimen surface along with moisture. Upon migration, it reacts with components in the rock to form secondary expansive products, such as gypsum. The crystallization pressure generated by these products damages the inter-particle bonds on the rock surface. Concurrently, H+ from H2SO4 continuously corrodes silicate minerals, leading to the loss of inter-particle cementation, resulting in layered exfoliation and surface loss. These observations are consistent with the XRD peak changes observed for acidic solutions in Figure 5. In alkaline solutions, products like ettringite clog pores and accumulate near the surface, forming a dense, hard shell. The difference in the thermal expansion coefficient between this shell and the underlying rock, coupled with stresses from wetting and drying, leads to degradation phenomena such as separation and bulging.

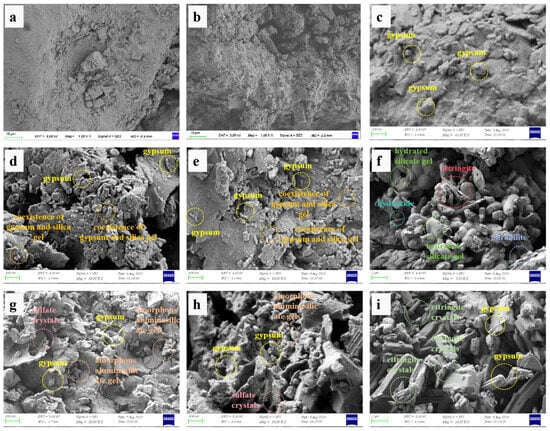

3.3. Microstructure

Figure 7 presents the microstructure of the pristine rock sample and samples subjected to 100 dry-wet cycles in different solutions.

Figure 7.

SEM microstructures of sandstone samples after 100 dry–wet cycles in different solutions: (a) Original sample; (b) distilled water; (c) 5%Na2SO4; (d) H2SO4 (pH = 4); (e) H2SO4 (pH = 6); (f) NaOH (pH = 8); (g) H2SO4 (pH = 4) + 5%Na2SO4; (h) H2SO4 (pH = 6) + 5%Na2SO4; (i) NaOH (pH = 8) + 5%Na2SO4.

- Pristine Sample (Figure 7a): The original rock shows no obvious layering and has fewer pores and cracks.

- Distilled water (Figure 7b): The sample surface exhibits densely distributed micropores and slight crack development. Some exfoliated particle fragments are present, but no new reaction products are observed in the microstructure.

- H2SO4 Solutions (Figure 7d,e): Samples cycled in H2SO4 solutions show significant pitting and layered damage due to acid dissolution. A large number of prismatic and flaky/flocculated sediments are generated. The prismatic precipitates are gypsum, while the flaky-flocculated mixtures are likely products from the coexistence of gypsum and silica gel. This corresponds to the significant enhancement of the secondary gypsum diffraction peaks in Figure 5.

- NaOH Solution (Figure 7f): The sample treated with NaOH exhibits a distinct spherical structure with fibrous features. These spherical aggregates are formed by the agglomeration of hydrated silicate gel (produced from the reaction of quartz with OH−) through van der Waals forces [37,38]. Notably, some prismatic ettringite, flaky magnesium hydroxide, and fish-scale-shaped mirabilite (Na2SO4·10H2O) are also observed.

- Composite Acid/Salt Solution (H2SO4 + 5% Na2SO4) (Figure 7g,h): The microstructure combines features of both single solutions. The rock surface shows a honeycomb-like porous structure with numerous needle/rod-shaped gypsum crystals and granular thenardite (Na2SO4, formed from the evaporation and precipitation of Na+). Abundant fragments composed of exfoliated minerals, sulfate crystals, and amorphous aluminosilicate gels chaotically fill cracks or adhere to particle surfaces.

- Composite Alkali/Salt Solution (NaOH + 5% Na2SO4) (Figure 7i): A densely packed, interwoven crystalline structure is observed. It contains numerous prismatic and needle-shaped ettringite crystals (formed from Ca2+, Al3+, and SO42− under OH− attack), with massive glauberite (Na2SO4·CaSO4) filling the gaps between ettringite crystals. Residual particles from mineral dissolution are distributed on the surface and within the pores.

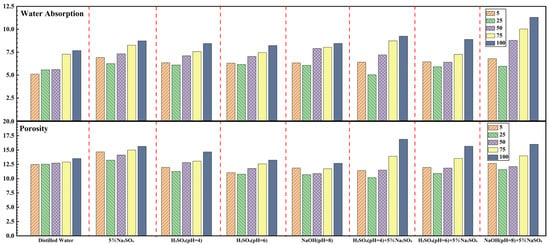

3.4. Physical Properties

3.4.1. Water Absorption and Porosity

The water absorption and porosity of rock samples subjected to dry-wet cycles in different solutions are presented in Figure 8. With an increasing number of cycles, both parameters for samples in all solutions exhibit a similar trend: an initial slight decrease followed by a sustained increase. However, the magnitude of change and the final values differ significantly depending on the solution type.

Figure 8.

Water absorption (top) and porosity (bottom) of sandstone samples after 5, 25, 50, 75, and 100 dry–wet cycles in distilled water, 5% Na2SO4, H2SO4 solutions (pH = 4\6), NaOH solution (pH = 8), and mixtures of H2SO4 (pH = 4\6) + 5% Na2SO4 and NaOH (pH = 8) + 5% Na2SO4.

After 100 cycles, the water absorption rates for samples treated with Distilled Water, 5% Na2SO4, H2SO4 (pH = 4), H2SO4 (pH = 6), NaOH (pH = 8), H2SO4 (pH = 4) + 5% Na2SO4, H2SO4 (pH = 6) + 5% Na2SO4, and NaOH (pH = 8) + 5% Na2SO4 were 7.4%, 8.7%, 8.4%, 8.2%, 8.5%, 9.2%, 8.9%, and 11.3%, respectively. The corresponding porosity values were 14.17%, 15.7%, 14.99%, 13.54%, 15.17%, 16.57%, 15.72%, and 17.34%.

Compared to other solutions, samples cycled in distilled water show a slower increase and lower final values for both water absorption and porosity. This indicates that deterioration under distilled water is primarily a physical process, likely driven by the gradual expansion and interconnection of micro-pores. This occurs as clay mineral particles within the red sandstone undergo repeated shrinkage and swelling due to water loss and uptake [39].

For H2SO4 and NaOH solutions, the water absorption and porosity initially show a brief decrease, followed by a sharp increase with continued cycling. By 25 cycles, both parameters exhibit a slight reduction. However, after 50 cycles, they begin to rise sharply, with final values substantially higher than those observed for distilled water.

This pattern can be attributed to the early formation of gypsum (in acidic conditions) and hydrated aluminosilicate gels (in alkaline conditions), as seen in Figure 5 and Figure 7. Initially, these products partially clog the rock’s micropores, temporarily reducing water absorption and porosity. As cycling progresses, the continued generation and accumulation of these products exert internal stress, causing original pores to burst and new microcracks to form. Concurrently, ongoing chemical erosion further weakens the internal structure, leading to the rapid expansion and interconnection of the pore network and, consequently, the observed rise in water absorption and porosity.

For solutions containing Na2SO4 (i.e., Na2SO4 alone, H2SO4 + 5% Na2SO4, and NaOH + 5% Na2SO4), the changes in water absorption and porosity are markedly greater than those caused by distilled water or single-component solutions. The data for these three solution groups show two sharp increases—at around 25 and 75 cycles—resulting in a step-like progression. Notably, samples treated with NaOH + 5% Na2SO4 exhibit the highest final water absorption and porosity among all solutions.

The mechanism follows a similar pattern: initial pore blockage by reaction products, followed by product-induced expansion that enlarges pores and increases connectivity. A key factor in the NaOH + 5% Na2SO4 treatment is the generation of substantial ettringite. Initially, ettringite crystallizes within existing micropores, temporarily reducing porosity. However, its continued formation generates significant expansive stress on the pore walls. This stress, combined with the repeated volumetric changes during wet-dry cycling, opens original pores, induces new microcracks, and greatly enhances pore connectivity. The pronounced effect is due to the substantial volumetric expansion associated with ettringite formation and growth, which can reach up to 250% of the original volume upon water immersion and may continue as crystals grow or hydrate [40,41]. This expansive mechanism is also the primary reason for the drastic changes in porosity and water absorption observed in samples treated with Na2SO4, H2SO4 + 5% Na2SO4, and NaOH + 5% Na2SO4.

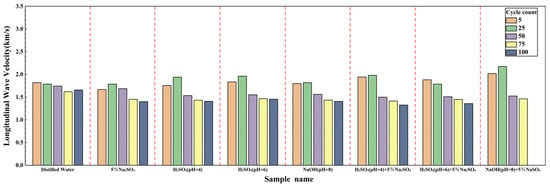

3.4.2. Longitudinal Wave Velocity

Figure 9 illustrates the variation in longitudinal (P-) wave velocity of rock samples after dry-wet cycles in different solutions. The wave velocity decreases with an increasing number of cycles for all solutions.

Figure 9.

Longitudinal wave velocity of sandstone samples after 5, 25, 50, 75, and 100 dry–wet cycles in distilled water, 5% Na2SO4, H2SO4 (pH = 4), H2SO4 (pH = 6) + 5% Na2SO4, and NaOH (pH = 8) + 5% Na2SO4.

The observed changes in P-wave velocity can be summarized as follows:

- Distilled water: The wave velocity decreases monotonically with cycling, indicating a uniform and gradual accumulation of damage from physical processes (e.g., microcrack expansion due to wetting/drying), without significant chemical alteration, as confirmed by XRD.

- Single Solutions (5% Na2SO4, H2SO4, NaOH): The wave velocity decreases at a relatively moderate rate. Samples in Na2SO4 and NaOH solutions show similar trends: slight initial fluctuations followed by a more rapid decline in later cycles. For H2SO4 solutions, the decrease follows a pattern of initial decline, brief stabilization, and then gradual acceleration. The reduction is slightly more pronounced at pH = 4 than at pH = 6.

- Composite Solutions (Acid/Salt & Alkali/Salt): These solutions cause a significantly sharper decline in wave velocity. After approximately 50 cycles, the wave velocity enters a phase of rapid decrease, with final values much lower than those for single solutions. The most drastic change occurs in the NaOH + 5% Na2SO4 solution, which shows a slight initial increase (likely due to pore-filling by early ettringite formation), followed by a sharp decline after 50 cycles, resulting in the lowest final wave velocity.

The decrease in wave velocity is fundamentally linked to the deterioration of the rock’s internal structure. Water infiltration softens mineral cementation, and repeated wetting/drying slowly expands microcracks, leading to a steady wave speed reduction that reflects cumulative physical damage [42]. In single solutions, initial pore-filling by small amounts of reaction products can cause minor fluctuations in wave speed. As cycling progresses, continued product expansion (e.g., gypsum, ettringite) or chemical dissolution (e.g., by H+) enlarges pores and cracks, accelerating the wave speed decline. The pronounced effect of composite solutions stems from the synergistic action of acid/alkali and SO42−, which generates abundant expansive products (e.g., ettringite) after about 50 cycles. These products drastically increase porosity and crack connectivity, leading to the rapid wave speed drop. The initial slight increase in wave speed for the NaOH + 5% Na2SO4 sample is attributed to transient pore-filling by nascent ettringite. However, the substantial expansive stress generated by continued ettringite growth soon overcomes this effect, causing severe damage and the lowest observed wave speed after 100 cycles.

3.5. Compressive Strength

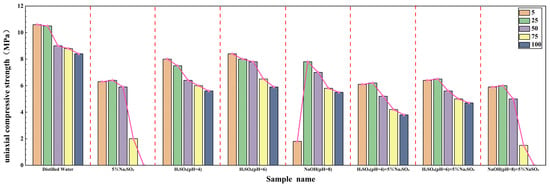

Figure 10 presents the uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) of rock samples after dry-wet cycles in different solutions.

Figure 10.

Uniaxial compressive strength of sandstone samples after 5, 25, 50, 75, and 100 dry–wet cycles in different solutions. The pink line indicates the overall decreasing trend in strength with increasing number of dry–wet cycles.

The UCS of all samples degraded with increasing cycles, but the degradation rate and final residual strength varied significantly:

- Distilled Water: UCS decreased in a stable, near-linear trend from an initial 11.2 MPa to 8.4 MPa (75% residual strength), consistent with slow physical deterioration.

- Acidic Solutions (H2SO4): Strength loss was more pronounced. After 100 cycles, residual strength was 50% (pH = 4) and 53% (pH = 6) of the initial value. This significant chemical weakening is attributed to the attack of H+ (in acid) or OH− (in alkali) on the silicate framework, breaking Si-O-Si and Al-O-Si bonds, which fundamentally compromises the cementing structure and weakens the entire sandstone matrix [43].

- Salt Solution (5% Na2SO4): Strength was briefly maintained around 6.4 MPa during the first 25 cycles, likely due to pore-filling by salt crystals. However, after 100 cycles, strength plummeted to 6.0 MPa, indicating severe damage from crystallization pressure.

- Composite Solutions: These caused the most severe strength reduction. The alkali-salt composite solution (NaOH + 5% Na2SO4) was particularly damaging, with strength dropping to 2.2 MPa after 100 cycles. This is due to the combined effects of chemical attack (OH−) and expansive crystal growth (ettringite and other sulfates), leading to extensive crack development and interconnection.

The decline in the strength of rock samples subjected to distilled water is attributed primarily to physical mechanisms. The wet-dry cycles induce the swelling and shrinkage of clay minerals and fluctuations in capillary water pressure. This results in the gradual loss of inter-particle cementation and the uniform propagation of micro-cracks, a process fully consistent with the observed monotonic decrease in P-wave velocity and the slow increase in porosity.

For samples in acidic and alkaline solutions, strength attenuation is driven predominantly by chemical dissolution. In acidic environments, H+ ions preferentially attack and dissolve calcareous cement. In alkaline conditions, OH− ions slowly hydrolyze silicate minerals, such as feldspar and quartz. These reactions directly disrupt the connective pathways between skeletal grains within the rock matrix, weakening the overall load-bearing structure and leading to an accelerated loss of strength.

The most drastic strength reduction occurred in samples treated with Na2SO4, H2SO4 + 5% Na2SO4, and NaOH + 5% Na2SO4. This results from a synergistic amplification of salt crystallization pressure and chemical corrosion. In the Na2SO4 solution, repeated crystallization and dissolution during cycling generate expansive pressures that far exceed the cementation strength between sandstone particles. In the composite solutions (H2SO4 + 5% Na2SO4 and NaOH + 5% Na2SO4), chemical attack by acid or alkali further compromises the rock’s internal integrity, creating additional void space for salt crystallization. This combined process leads to the wholesale disintegration of inter-particle bonds, culminating in a precipitous, cliff-like drop in compressive strength.

4. Conclusions

This study investigated the deterioration behaviour of sandstone from the Huachi Stone Statue Twin Towers by subjecting samples to cyclic dry-wet treatments in distilled water; 5%Na2SO4; H2SO4 (pH = 4); H2SO4 (pH = 6); NaOH (pH = 8); H2SO4 (pH = 4) + 5%Na2SO4; H2SO4 (pH = 6) + 5%Na2SO4; NaOH (pH = 8) + 5%Na2SO4 that represent key local environmental factors. The chemical composition, apparent morphology, microstructure, physical properties, and uniaxial compressive strength were systematically analyzed. The principal conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- Chemical Composition: XRD analysis indicates the primary minerals in the pristine sandstone are quartz, calcite, and plagioclase (including albite). The chemical evolution post-cycling is strongly dependent on solution chemistry. Distilled water caused minimal change. In the 5% Na2SO4 solution, secondary gypsum formation was evident. Acidic (H2SO4) solutions significantly weakened quartz and diopside peaks while enhancing gypsum peaks, due to H+-driven dissolution and sulfate reaction. Alkaline (NaOH) conditions slightly attenuated quartz and albite peaks but enhanced calcite peaks, with sodium silicate and aluminate likely forming. In composite solutions (H2SO4/NaOH + 5% Na2SO4), ion synergy intensified reactions. For H2SO4 + Na2SO4, abundant gypsum formed from the released Ca2+ and SO42−. For NaOH + Na2SO4, gypsum formation was limited by suppressed calcite dissolution, while ettringite was generated.

- (2)

- Apparent Morphology: All cycled samples exhibited surface deterioration including edge rounding, powdering, and loss of gloss. Distilled water caused only slight deterioration. H2SO4 solutions induced micro-notching and particle detachment. NaOH led to layered exfoliation and crust formation. The 5% Na2SO4 solution resulted in prominent efflorescence and pore-filling salt crystals. Composite solutions combined these features, with NaOH + 5% Na2SO4 causing the most severe damage, nearly covering specimens with salt frost and exfoliation.

- (3)

- Microstructure: The pristine rock showed a dense structure with few pores. Post-cycling, distilled water induced micropore clusters and microcracks without new products. The Na2SO4 solution produced gypsum crystals that induced microcracking. H2SO4 solutions caused pitting, layered damage, and co-precipitation of gypsum with silica gel. NaOH treatment generated spherical hydrated silicate gel aggregates, alongside ettringite, magnesium hydroxide, and mirabilite. Composite solutions exhibited combined features: H2SO4 + Na2SO4 formed a honeycomb structure with needle-like gypsum and thenardite, while NaOH + Na2SO4 produced a dense intergrowth of ettringite and glauberite crystals.

- (4)

- Physical Properties (Water Absorption, Porosity, & Wave Velocity): Water absorption and porosity followed a general trend of an initial slight decrease followed by a sustained increase. Distilled water caused the slowest rise (final absorption: 7.4%; porosity: 14.17%), indicative of gradual physical pore expansion. Single-component solutions showed a temporary decrease due to initial pore-filling by reaction products, followed by a significant increase as product expansion and chemical dissolution widened pores. The NaOH + 5% Na2SO4 composite solution resulted in the highest final values (absorption: 11.3%; porosity: 17.34%), showing a stepwise increase. P-wave velocity changes correlated with porosity evolution. Velocity decreased monotonically in distilled water. In single solutions, decline was moderate, with initial fluctuations from pore-filling. Composite solutions, particularly NaOH + Na2SO4, triggered a rapid velocity decline after 50 cycles, reaching the lowest final value.

- (5)

- Compressive Strength: Uniaxial compressive strength degraded in all solutions, but the extent varied drastically. Distilled water caused a gradual linear decrease to 75% residual strength after 100 cycles, consistent with physical damage. Acidic and alkaline solutions led to more significant chemical weakening, with residual strengths of approximately 50–53% (H2SO4) and 43% (NaOH). Salt and composite solutions induced the most severe strength loss due to the synergy of salt crystallization pressure and chemical attack. The strength of samples in 5% Na2SO4 and NaOH + 5% Na2SO4 exhibited a stepwise, drastic failure, with residual strength approaching zero after 100 cycles.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z. and P.H.; methodology, J.Z., P.H. and Y.L.; validation, P.H. and Y.L.; investigation, P.H., Y.L., W.H. and Y.Z.; resources, J.Z., W.H., Y.Z., Q.W. and Y.N.; data curation, P.H. and Y.N.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Z. and P.H.; writing—review and editing, J.Z. and P.H.; visualization, P.H., Q.W. and Y.N.; supervision, J.Z.; funding acquisition, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [Gansu Provincial Department of Science and Technology] grant number [25YFFA088].

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, J.; Zhu, Z.; Zhong, H.; Pei, Q.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Xie, X. Research on Seismic Response Mechanism of Stone Cultural Relics Based on Discrete Element Method. J. Seismol. Res. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Arif, A.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, R.; Sajib, M.H.; Peng, N.; Zhuang, W.; Feng, M.; Yuan, M.; Zhang, Y. Crack Propagation and Strength Characteristics of Rock Mass Containing Cross-Cracks in Immovable Stone Cultural Relics. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2024, 42, 7307–7338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, C.; Mara, C.; Tie, F.; Dong, W. Study on Nanomaterials and Technology for Composite Strengthening of Stone Cultural Relics. Mater. Rep. 2025, 39, 380–384. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Navarro, C.; Elert, K.; Sebastian, E.; Esbert, R.M.; Grossi, C.M.; Rojo, A.; Alonso, F.J.; Montoto, M.; Ordaz, J. Laser cleaning of stone materials: An overview of current research. Stud. Conserv. 2003, 48, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Guo, Q.; Chen, W.; Sun, M.; Zhang, J. Research Progress in the Protection and Reinforcement of the Rock Mass of the Grotto Temple. Res. Conserv. Cave Temples Earthen Sites 2022, 1, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, M.F.; Voldoire, O.; Roussel, E.; Vautier, F.; Phalip, B.; Peou, H. Contrasting weathering and climate regimes in forested and cleared sandstone temples of the Angkor region. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2012, 37, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, H.; Lu, H.; Bao, H.; Li, L.; Chen, W.; Guo, J.; Liu, S. Research progress on the mechanism of deterioration and instability of the rock mass of grotto temples. Earth Sci. 2023, 48, 1603–1633. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Shao, G.; Huang, R.; Shi, B.; Di, Z.; Fang, J. Study on the weathering resistance of microbial mineralization cemented sandstone and its application in the restoration of limestone cultural relics. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2025, 44, 2112–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T. Research on the Evolution Mechanism of Single-Axis Compression Failure of Soluble Fissured Limestone After Dry and Wet Cycles. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Z.; Liu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, G.; Xia, Y.; Su, B.; Zhou, T.; Lv, G.; Luo, H. The migration and damage mechanism of salt in cultural relics. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 2017, 29, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Cao, Z.; Shen, Y.; Shang, X.; Luo, Y. Research on the regional characteristics of sandstone grotto diseases in the eastern part of the Loess Plateau. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 2024, 36, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Zhou, P.; Ma, H.; Zhou, W.Q. Practice of Stone Cultural Relics Conservation in Xi’an Center for the Conservation and Restoration of Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the 2005 Yungang International Academic Symposium (Conservation Volume); Yungang Grottoes Research Academy, Ed.; Xi’an Center for the Conservation and Restoration of Cultural Heritage: Xi’an, China, 2005; pp. 395–405. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Zhang, Y. Combined Effects of Salt, Cyclic Wetting and Drying Cycles on the Physical and Mechanical Properties of Sandstone. Eng. Geol. 2019, 248, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J. Research on the Protection of the Shangdang Yangtoushan Yandi Stone Carving Archives in Shanxi. Master’s Thesis, Yunnan University, Kunming, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, B.; Li, X.; Peng, N.; Sheng, Y.; Liang, Y. Experimental Study on Salt-Bearing Sandstone Samples Under the Change of Temperature and Humidity Cycle. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2025, 19, 1385–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Shuyun, Z.; Kefa, R. Study on the salt weathering and mechanism of the Banyueshan Giant Buddha in Ziyang City, Sichuan Province, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Deng, H.; Wan, L.; Wang, W.; Liu, P.; Qian, X. Study on the Degradation Effect of Fracture Characteristics of Fissured Sandstone under Dry and Wet Cyclic Conditions. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2024, 46, 1–10. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/32.1124.TU.20251031.1657.005 (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Xia, Y.; Ma, J. Research on the Pore Structure and Mechanical Properties of Red Sandstone under Dry and Wet Cycles. Sichuan Build. Mater. 2025, 51, 99–102+107. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. Survey and Research on the Existing Ancient Towers in the Eastern Gansu Region. Master’s Thesis, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.H.; Yi, J.E. Weathering damage evaluation of rock properties in the Bunhwangsa temple stone pagoda, Gyeongju, Republic of Korea. Environ. Geol. Int. J. Geosci. 2007, 52, 1193–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Guo, F.; Polk, J.S. Salt transport and weathering processes in a sandstone cultural relic, North China. Carbonates Evaporites 2015, 30, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Huang, M. The weathering characteristics of red sandstone under the simulated acid rain dry and wet cycle conditions. Chin. J. Geol. Hazard Control 2018, 29, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, R.; Jiang, X.W.; Ouyang, K.; Yang, X.; Wang, X.S.; Huang, J.Z.; Yan, H.B.; Wan, L. Rock moisture dynamics in sandstone caves responsible for weathering: Field observations and numerical modeling. Eng. Geol. 2025, 354, 108185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Huang, B.; Yao, Y.; Pu, J.; Zhang, T. Monitoring and statistical analysis of the characteristics of acid rain in the Loess Plateau cities of eastern Gansu. J. Arid Meteorol. 2005, 23, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- ISRM. Suggested Methods for Determining Uniaxial Compressive Strength; ISRM: Lisbon, Portugal, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 50266-2013; Engineering Rock Mass Test Method Standard. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2013.

- ISO 14544-2013; Fine Ceramics (Advanced Ceramics, Advanced Technical Ceramics)—Determination of Phase Content of Ceramic Powders—X-Ray Diffraction Method. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- ISO 16700-2004; Microbeam Analysis—Scanning Electron Microscopy—Guidelines for Calibrating Image Magnification. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2004.

- GB/T 35206-2025; Shale and Mudstone Rock Thin Section Identification. State Administration for Market Regulation, Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2025.

- Zhao, Y.; Xiao, T.; Zhao, E.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Wei, S. Pore structure and dynamic strength deterioration characteristics of weakly cemented sandstone under freeze-thaw cycles. China Min. Mag. 2025, 34, 226–233. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Yang, G.; Ye, W.; Liang, B. Study on the law and mechanism of strength deterioration of sandstone with different particle sizes under freeze-thaw cycles. J. Eng. Geol. 2024, 32, 2198–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Liu, C.; Wang, M.; Zhou, X.; Wang, P.; Hou, D. Molecular structure evolution and deterioration mechanism of hydrated calcium silicate under sulfate erosion. J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J. Research on the Mechanical Characteristics of Rock Macro- and Micro-Fractures and Subcritical Crack Propagation Behavior Under Complex Conditions. Ph.D. Thesis, Central South University, Changsha, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, N. The Mechanical Response and Instability Mechanism of Loaded Fissured Coal-Rock Combination Under the Action of Hydrochemistry. Master’s Thesis, Inner Mongolia University of Science and Technology, Baotou, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, J.; Li, C.; Zhou, J.-Q.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, D.; Wang, G. Multiscale evolution mechanism of sandstone under wet-dry cycles of deionized water: From molecular scale to macroscopic scale. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2023, 15, 1171–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. The Evolution of the Cenozoic Basin at the Western Margin of the Ordos Block. Ph.D. Thesis, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bothra, S.R. Polymer-modified concrete: Review. Int. J. Res. Eng. Technol. 2015, 4, 845–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J. Research on Shrinkage Cracks of Aerated Concrete Masonry Wall. Concrete 2007, 03, 92–94. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chao, D.; Jia, G. Microstructure and shear strength correlation of weak intercalation in red sandstone under dry and wet cycle conditions. Rock Soil Mech. 2018, 39, 1633–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Sun, J.; Zhang, P.; Yang, Q.; Wan, X.; Feng, X.; Wang, Z.; Ding, J. Research on the Preparation and Performance Optimization of Shielded-Tunneling Muck-Based Non-Burning Expanded Clay Agg. Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, B.; Chen, H.; Yang, L.; Wang, H.; Cao, J. Study on the influence of modified phosphogypsum with lime-cement-fly ash on the physical properties of cement. Inorg. Chem. Ind. 2022, 54, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinrong, L.; Zijuan, W.; Yan, F.; Wen, Y.; Luli, M. Macro/Microtesting and Damage and Degradation of Sandstones under Dry-Wet Cycles. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 2016, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Z.H.; Zhao, Z.M.; Hu, P.; Wang, Z. Research Progress of Alkali-Activated Cementitious Materials in Soft Soil Solidification. China Build. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 34, 19–22+27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.