Featured Application

The findings of this study can be applied to the design, selection, and digital manufacturing of functional orthodontic appliances for the treatment of skeletal Class II malocclusion. By demonstrating how different appliance design architectures and production workflows influence skeletal and dentoalveolar responses, the results may support evidence-based decision-making in digital orthodontic treatment planning and CAD/CAM-based functional appliance fabrication.

Abstract

Functional appliances constitute a common treatment approach for skeletal Class II malocclusion. However, evidence regarding the effects of appliance design and manufacturing workflows on treatment outcomes remains limited. This study aimed to compare the skeletal, dentoalveolar, and soft tissue effects of conventionally fabricated, prefabricated, and digitally designed functional appliances. A total of 28 growing patients with skeletal Class II malocclusion were retrospectively assessed and evenly assigned to four treatment groups: Twin Block, PowerScope, Invisalign Mandibular Advancement, and digitally designed Herbst. Skeletal, dentoalveolar, and soft tissue parameters were evaluated using lateral cephalometric radiographs obtained before (T0) and after treatment (T1). Statistical analyses included one-way ANOVA, repeated-measures ANOVA, and the Kruskal–Wallis test. All treatment modalities demonstrated significant sagittal improvement, characterized by reductions in ANB and Wits values and increases in SNB angle and mandibular length (Co–Gn). The Twin Block appliance showed a significantly greater increase in mandibular length compared with the other groups (p = 0.037). Dentoalveolar adaptations were more pronounced in the PowerScope and Invisalign Mandibular Advancement groups. In conclusion, within the limitations of this retrospective pilot study, functional appliances with different design and manufacturing characteristics appear to produce distinct skeletal and dentoalveolar response patterns, and digitally designed systems may represent clinically effective alternatives for the treatment of skeletal Class II malocclusion; however, these findings should be considered preliminary and interpreted with caution.

1. Introduction

Class II malocclusion is among the most prevalent anomalies encountered in orthodontic practice, affecting approximately one-third of the population. The most characteristic clinical feature of this malocclusion is mandibular retrusion, which results in marked sagittal disharmony within the craniofacial complex [1]. The effects of Class II malocclusion extend beyond skeletal and dental components and may substantially influence an individual’s quality of life. It can affect orofacial functions such as chewing, speaking, and swallowing, and may cause negative psychosocial effects due to its influence on facial appearance [2,3]. Correction of skeletal discrepancies through stimulation of mandibular growth contributes to a significant improvement in both functional harmony and facial esthetics [4].

Functional appliances used in the treatment of Class II malocclusion are designed to apply forces to the teeth and jawbones by modifying the activity of muscle groups that influence mandibular position and function. These forces are generated through changes in the sagittal and vertical positioning of the mandible, resulting in both orthodontic and orthopedic effects [5].

Functional appliances were first introduced into clinical practice in the 1930s and, although they have long been considered a fundamental approach in orthodontic treatment, their working mechanisms and effectiveness are still being discussed today [5]. Functional treatment can be performed using either removable or fixed functional appliances. The main difference between these two approaches is the level of patient compliance required, which greatly influences treatment effectiveness and the predictability of outcomes [6]. Functional appliances used in the orthodontic management of Class II malocclusion may be produced using three different fabrication approaches. In conventional techniques, appliances are manually fabricated by skilled orthodontic technicians, customized for each patient according to individual anatomic and occlusal characteristics. Prefabricated (ready-made) appliances, on the other hand, are manufactured in predetermined standard sizes. In recent years, with the widespread adoption of computer-aided design and manufacturing (CAD/CAM) technologies, digitally planned and three-dimensionally printed functional appliances have been introduced into clinical practice [7].

The Twin Block appliance, originally introduced by Clark, is among the most frequently applied conventional functional appliances for the management of skeletal Class II malocclusion. The Twin Block consists of two interlocking removable plates with inclined acrylic bite blocks that guide the mandible forward during occlusion [8].

The PowerScope appliance has been introduced as a hybrid option within fixed functional systems and has gained increasing clinical attention in recent years. Owing to its prefabricated design, the appliance can be applied directly in the clinical setting without requiring laboratory procedures, which constitutes a practical advantage [9]. With its telescopic mechanism, the appliance maintains the mandible in a continuous forward position, contributing to both skeletal and dentoalveolar modifications. Treatment progression is supported by the internal nickel–titanium spring mechanism, while the ball-and-socket joint architecture enables lateral mandibular mobility consistent with physiological movement patterns, potentially improving patient comfort [10,11]. As a fixed functional system, it removes the dependence on patient compliance and enables a single-phase, predictable treatment process [12]. With the advancements in digital technology over the past two decades, diagnostic methods and treatment planning in orthodontics have shifted from traditional approaches to fully digital applications [13]. For a long period, orthodontic appliance fabrication was predominantly based on manual production techniques. Traditional manufacturing processes involved multiple time-consuming steps with a high potential for error, such as impression taking, plaster model casting, wire bending and acrylic application. However, these methods have now been largely replaced by digital manufacturing technologies, including CAD/CAM systems, three-dimensional printing, and laser sintering [14,15].

The Herbst appliance, one of the most commonly used fixed functional devices in the treatment of Class II malocclusion, was traditionally fabricated manually through banding and laboratory procedures. With recent advances in computer-aided manufacturing technologies, the appliance can now be digitally designed and directly produced as a metal device [16]. Intraoral scanners make it possible to capture a highly accurate digital model of the patient’s mouth and greatly reduce impression errors [17]. The digital data obtained allow the appliance to be virtually designed using computer-aided design (CAD) software. Then, with advanced manufacturing technologies such as laser sintering, the appliance can be directly produced in metal form [16]. With this method, the appliance can be planned in a three-dimensional environment using CAD/CAM software (3Shape Appliance Designer module, 2019; 3Shape A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark), and directly manufactured from biocompatible metals such as cobalt–chromium or titanium without the need for a plaster model. This digital production workflow not only enhances clinical efficiency but also enables the creation of highly precise, patient-specific appliance designs [14,15].

The Invisalign Mandibular Advancement (MA) system is a treatment modality that combines the principles of functional therapy with digital clear aligner technology for the management of skeletal Class II malocclusion. As a fully digital appliance, it is individually planned and customized using three-dimensional intraoral scans of the patient and computer-aided design software. Through specially designed “precision wings,” the system advances the mandible while simultaneously allowing for dental alignment [18,19]. Previous studies have evaluated the skeletal and dentoalveolar effects of various functional appliances in Class II patients. Mills and McCulloch [20] and Trenouth [21], in studies conducted on samples of approximately 28–30 subjects, reported significant skeletal and dentoalveolar improvements in individuals treated with the Twin Block appliance. Arora et al. [22]. compared the effects of PowerScope and Forsus appliances in a similar sample size (n = 28). Kong and Liu [23] demonstrated that Invisalign MA treatment effectively promotes mandibular growth in adolescent patients with mandibular retrusion.

The aim of this study was to compare the skeletal, dental, and soft tissue changes in patients with Class II malocclusion treated with conventional functional appliances (Twin Block and PowerScope) and those treated with digitally designed functional appliances (Invisalign MA and digital Herbst). The null hypothesis of the study stated that there would be no significant differences in skeletal, dental, or soft tissue changes among patients treated with Twin Block, PowerScope, Invisalign MA, and digital Herbst appliances.

2. Materials and Methods

This investigation was conducted as a retrospective cohort pilot study following approval from the XXX University Non-Interventional Research Ethics Committee (Decision No: 2025.06.30, Date: 25 June 2025). The study was based on the retrospective evaluation of archived patient records obtained from the Department of Orthodontics, XXX University.

The study sample comprised 28 growing patients, who were evenly allocated into four treatment groups (n = 7 per group). A priori power analysis was performed using G*Power (version 3.1) to estimate a reasonable sample requirement for pilot data. The analysis was conducted with α = 0.05 and an assumed effect size of f = 0.60, which is commonly referenced in functional appliance research. This calculation indicated that a total of approximately 28 participants would provide a statistical power close to 80% (1–β ≈ 0.80).

Nevertheless, owing to the retrospective design of the study and the limited number of eligible patient records, each treatment group ultimately included seven individuals. Accordingly, the present study was classified as a retrospective pilot investigation, and all statistical analyses were therefore performed with an exploratory approach.

The inclusion criteria for the study were ANB ≥ 4°, a normo- or hypodivergent growth pattern, and being in the S or MP3cap stage of skeletal maturation. Individuals with congenital tooth agenesis, craniofacial syndromes, maxillofacial trauma, temporomandibular joint disorders, or a history of systemic or periodontal disease were excluded from the study. The participants were divided into four groups according to the type of functional appliance used: Twin Block (n = 7, mean age 12.23 ± 0.96 years, 3 females, 4 males), PowerScope (n = 7, mean age 12.81 ± 1.06 years, all females), Digital Herbst (n = 7, mean age 12.99 ± 1.18 years, 3 females, 4 males), and Invisalign MA (n = 7, mean age 12.50 ± 1.66 years, 3 females, 4 males). Evaluations were performed using lateral cephalometric radiographs taken at the pretreatment (T0) and posttreatment (T1) stages. The images were analyzed with Dolphin Imaging software (version 11.95 Premium; Dolphin Imaging& Management Solutions, Chatsworth; GA, USA). A total of thirty skeletal, dentoalveolar, and soft tissue parameters were assessed in the measurements.

In the skeletal evaluation, the following parameters were measured: SNA, SNB, ANB, Wits, Co-Gn, A-Na Perp, Pg-Na Perp, FMA, GoGn-SN, P-A facial height, skeletal convexity angle, and the ratios of upper and lower facial height to total facial height (UFH/TFH, LFH/TFH).

For the dentoalveolar assessment, the measurements included U1-SN, U1-PP, U1-FH, U1-NA (mm), L1-NB, IMPA, U1-PP (mm), L1-MP (mm), U6-PP, L6-MP, overjet, and overbite. In the soft tissue analysis, upper and lower lip distances to the E-plane, nasolabial angle, and soft tissue convexity angle were measured.

All measurements were performed by the same researcher (AA). To assess measurement reliability, cephalometric analyses of five randomly selected patients from each group were repeated after a two-week interval, and the agreement between the two sets of measurements was evaluated using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).

In all treatment groups, mandibular advancement was adjusted individually based on the patient’s initial sagittal discrepancy, overjet values, incisor inclinations, and clinical response, including functional adaptation and patient tolerance during treatment. The primary treatment objective was to achieve a functional Class I relationship; therefore, the extent of mandibular advancement varied among patients. As a result, a single standardized numerical value for mandibular advancement could not be applied across all individuals.

The PowerScope appliance (American Orthodontics, Sheboygan, WI, USA) was applied in all cases after the alignment of the maxillary and mandibular dental arches was completed and 0.019 × 0.025-inch stainless steel archwires were placed. The appliance was positioned at the mesial side of the maxillary first molar and the distal side of the mandibular canine (Figure 1). The internal nickel–titanium spring mechanism, designed to advance the mandible, delivers a constant force of 260 g to ensure continuous activation throughout the treatment period. To achieve this force level, the middle telescopic tube of the appliance must reach its fully compressed position. Depending on tooth size and the individual severity of the Class II malocclusion, 1 mm, 2 mm, or 3 mm spacers were used during appliance placement to achieve optimal activation. As a fixed appliance, the PowerScope is designed for continuous 24-h use and was worn by patients for an average duration of 7.71 ± 1.70 months.

Figure 1.

(A–C) Intraoral frontal and lateral views of the Power Scope appliance.

The Herbst appliance was digitally designed on a 3D maxillary model and fabricated from a cobalt–chromium (Co-Cr) alloy using the selective laser melting (SLM) technique in a dental laboratory (Orthodigi, İzmir, Turkey). The posterior teeth were covered with metal on both their buccal and lingual surfaces. To connect the right and left segments, two metal bars with a diameter of 1 mm were incorporated in the maxilla, and a single anteriorly extending metal bar was used in the mandible (Figure 2). The maxillary and mandibular jaws were connected by a telescopic mechanism extending between the maxillary first molar and the mandibular first premolar. At the beginning of treatment, the mandible was advanced approximately 5 mm to achieve an edge-to-edge incisal relationship, and the appliance was activated in this position. During follow-up visits, the degree of activation was gradually increased in increments of 1–2 mm, allowing for progressive mandibular advancement until a Class I molar relationship was achieved in the posterior region. As a fixed appliance designed for continuous 24-h use, it was worn in the mouth for an average duration of 8.57 ± 0.98 months.

Figure 2.

(A–C) Intraoral frontal and lateral views of the digitally designed Herbst appliance.

The Twin Block appliance was fabricated on an articulator using wax bite registration and dental casts to achieve a Class I occlusal relationship (Figure 3). The appliance was worn for 20–22 h per day. When clinically indicated, an expansion screw was incorporated and activated twice per week by a quarter turn each time to achieve maxillary expansion. After expansion was completed, the screw was fixed, and appliance wear was continued. In the Twin Block group, the appliance was used for an average duration of 12.29 ± 2.36 months, and selective acrylic trimming was performed in the posterior regions to maintain vertical control of the molar segments.

Figure 3.

(A–C) Intraoral frontal and lateral views of the twin-block appliance.

In the Invisalign MA group, when clinically indicated, a preparatory phase known as the pre-MA stage was implemented prior to mandibular advancement. This phase was indicated in cases presenting with deep bite (>8 mm), maxillary incisor retrusion, posterior crossbite, or maxillary molar rotation (>20°). After the necessary corrections were completed during the pre-MA phase, mandibular advancement was initiated, with the jaw position advanced in 2 mm increments at eight-week intervals (Figure 4). The total treatment duration was 9.71 ± 1.25 months, and the aligners were prescribed to be worn for 20–22 h per day.

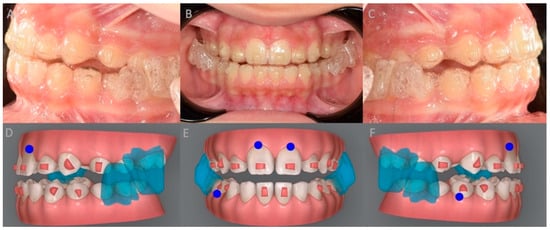

Figure 4.

(A–C) Intraoral frontal and lateral views of MA the appliance (D–F) MA appliance design on the patient’s STL-based models. The blue shaded areas represent the mandibular advancement wings of the appliance.

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software, version 26.0. Descriptive statistics were presented as mean ± standard deviation. The normality of variable distributions was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test along with skewness and kurtosis values. Group comparisons were conducted using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for variables that followed a normal distribution. For post hoc analyses, the Bonferroni test was applied when homogeneity of variances was confirmed, whereas Tamhane’s T2 test was used when the assumption of homogeneity was not met. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used for comparisons involving variables that did not follow a normal distribution. Repeated-measures analysis of variance was applied to determine time-dependent differences in cephalometric values. A significance level of 0.05 was adopted for all statistical evaluations.

3. Results

An intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) value greater than 0.95 for all parameters indicated a high level of measurement repeatability.

The shortest treatment duration was observed in the PowerScope group (7.71 ± 1.70 months), whereas the longest was recorded in the Twin Block group (12.29 ± 2.36 months). The treatment duration was 8.57 ± 0.98 months in the Herbst group and 9.71 ± 1.25 months in the MA group (Table 1). A statistically significant difference in treatment duration was found among the groups (p < 0.05). Although the time effect was not significant (p = 0.113), the intergroup difference was significant (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Treatment Duration by Groups.

Table 2.

Results of repeated-measures ANOVA for cephalometric variables.

Baseline (T0) comparisons revealed statistically significant intergroup differences for several cephalometric parameters, including ANB angle, A–Na perpendicular, Pg–Na perpendicular, skeletal convexity, UPH/TFH, LFH/TFH, overjet, L1–NB, IMPA, UL to E-plane, and LL to E-plane (p < 0.05). Other baseline skeletal, dentoalveolar and soft tissue variables did not differ significantly among the groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of Baseline (T0) Cephalometric Characteristics and Descriptive Statistics.

Post hoc analyses demonstrated that changes in the SNA angle varied significantly between the treatment modalities (p < 0.05). The greatest increase in SNA was observed in the Invisalign MA group, followed by the Twin Block group, whereas minimal change was noted in the PowerScope group. Post hoc analysis revealed that mandibular length (Co-Gn) showed the greatest increase in the Twin Block group. This increase was statistically significant compared with the Power Scope, Invisalign MA and digital Herbst groups (p < 0.05). (Table 4). P–A face height also differed among treatment modalities, showing an increase in the Twin Block and Invisalign MA groups and decreases in the Herbst and Power Scope groups (p < 0.05).

Table 4.

Intergroup Comparison of T1–T0 Changes for Cephalometric Variables.

Dentoalveolar responses differed among the treatment groups. Post hoc analyses showed that increases in lower incisor protrusion (L1–NB) were significantly greater in the Power Scope and Invisalign MA groups compared with the Herbst and Twin Block groups (p < 0.05). In contrast, the increase in lower incisor inclination (IMPA) was significantly greater in the Herbst and Power Scope groups than in the Invisalign MA and Twin Block groups (p < 0.05). Significant intergroup differences were also observed for vertical lower incisor position (L1–MP, mm), with a greater reduction noted in the Herbst group compared with the Invisalign MA group (p < 0.05). Additionally, reductions in overbite differed significantly among treatment modalities, with more pronounced decreases observed in the Herbst and Power Scope groups (p < 0.05). Molar positional changes varied between groups, and post hoc comparisons revealed significant intergroup differences for both maxillary (U6–PP) and mandibular molar positions (L6–MP) (p < 0.05).

Post hoc analyses revealed significant intergroup differences in upper lip position relative to the E-plane (UL–E plane), with a more pronounced reduction observed in the Herbst group compared with the other treatment modalities (p < 0.05). Significant differences were also identified for lower lip position relative to the E-plane (LL–E plane), with greater protrusion observed in the Invisalign MA and Twin Block groups compared with the Herbst and Power Scope groups (p < 0.05). Detailed cephalometric measurements at T0, T1, and T1–T0 are reported in Supplementary Table S1. For variables showing significant intergroup differences, post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed to identify specific group contrasts, and the detailed results are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

4. Discussion

Functional appliances have long constituted a cornerstone in the management of growing patients, designed to guide the development of maxillomandibular relationships and enhance facial aesthetics [4,5]. The principal objective of these therapies is to stimulate mandibular growth to correct underlying skeletal discrepancies. Nevertheless, treatment outcomes may differ considerably according to the timing of intervention, the specific appliance design, and the method by which mandibular advancement is achieved [1,24,25].

Although a substantial body of literature has investigated the effectiveness of functional appliances, studies providing direct comparisons among different appliance types remain scarce. Furthermore, the generalizability of current evidence is limited by heterogeneous sample compositions and methodological inconsistencies across studies [26,27]. The paucity of studies focusing on emerging treatment modalities—particularly digital systems—highlights the growing relevance of this topic. Accordingly, the present study aimed to provide a unique contribution to the literature by comparatively evaluating the dentoskeletal and soft tissue effects of conventional (Twin Block), modern hybrid (PowerScope), and digitally designed functional appliances (Invisalign MA, digital Herbst) in patients treated during the same growth period.

The null hypothesis proposed in this study stated that no significant differences would be observed among the four functional appliance groups with respect to skeletal, dentoalveolar, and soft tissue changes. However, the findings of the present investigation indicated that this hypothesis could not be fully supported. Within the limitations of this pilot study, differences in response patterns were observed among the treatment groups. Relatively greater skeletal changes, reflected by increases in Co–Gn length, were noted in the Twin Block group, whereas the PowerScope group demonstrated more pronounced dentoalveolar responses, particularly with respect to incisor inclination. Additionally, changes in soft tissue parameters appeared to be more evident in the Twin Block group, suggesting a potential influence of removable functional appliances on mandibular projection.

Beyond their clinical effectiveness, the material composition and design features of functional appliances are also critical determinants of overall treatment success [28]. Twin Block appliances, composed of acrylic plates and manually bent wire components, present certain limitations in terms of structural durability and stability. These shortcomings may lead to issues such as fracture, wear, and volumetric deformation, thereby necessitating repeated laboratory adjustments throughout the course of treatment [1,8].

While the fixed structure of conventional Herbst appliances offers an advantage in terms of patient compliance, their fabrication from manually shaped wire components increases the risk of misfit due to measurement and assembly errors. In recently developed digital Herbst systems, however, CAD/CAM-assisted production and laser melting technologies have eliminated the need for plaster models, enabling the fabrication of highly precise and biocompatible (Co-Cr or titanium-based) customized appliances. These advancements have not only improved the efficiency of the manufacturing process but also enhanced the predictability of clinical outcomes [13,15,16].

The Invisalign MA system, owing to its polymer-based material, offers an appealing alternative that enhance treatment acceptance, particularly among patients with high aesthetic expectations. Although Invisalign MA may present certain limitations compared with fixed functional systems in terms of force transmission and its reliance on patient compliance, its favorable aesthetic properties and ease of use have been associated with improved patient cooperation when compared with removable appliances such as the Twin Block [18,19,29,30].

PowerScope, with its single-piece design, does not require laboratory preparation; its telescopic configuration, nickel–titanium internal spring mechanism, and ball-and-socket joint connection provide patient comfort and allow a degree of lateral mandibular movement. However, a tendency toward increased mandibular incisor proclination has been reported, suggesting potential clinical limitations related to material flexibility and the control of force direction [12,31].

The design and material characteristics of different functional appliances may influence the dentoskeletal and soft tissue responses observed during treatment. In the present study, improvements in sagittal skeletal relationships were observed across all appliance groups over the treatment period. Changes in the SNA, SNB, and ANB angles, as well as in Wits appraisal values, suggest that functional appliances can contribute to the regulation of maxillomandibular positional relationships. In particular, the increases in SNB angle and the reductions in ANB and Wits values observed in the Twin Block and Herbst groups are indicative of anterior mandibular positioning and an overall improvement in sagittal skeletal relationships. Similar effects of the Twin Block appliance on mandibular growth have also been reported by Cozza et al. [1] and Koretsi et al. [27].

In this study, an increase in Co–Gn length was observed across all treatment groups, with the greatest mean increase recorded in the Twin Block group. This finding suggests that removable functional appliances may contribute to mandibular growth during the active treatment phase. When the available evidence is considered, particularly the recent meta-analysis published by Xu et al. [32], it has been shown that no statistically significant difference exists between Herbst and Twin Block appliances with respect to Co–Gn changes, whereas a more pronounced increase in Go–Gn was observed in favor of the Herbst appliance. Rather than indicating conflicting results, these differences are more likely related to the use of distinct outcome measures that reflect different anatomical components of mandibular growth. Specifically, Co–Gn and Go–Gn measurements represent different aspects of mandibular morphology, capturing effective mandibular length and posterior mandibular components from different perspectives. Moreover, the studies included in the meta-analysis by Xu et al. [32] exhibited substantial heterogeneity in terms of patient populations, growth stages, appliance designs, and activation protocols, which may further contribute to variability in treatment responses. In this context, the effects of functional appliances on mandibular growth should be interpreted using a comprehensive and cautious approach that considers clinical context and methodological differences across studies.

In the MA group, sagittal correction appeared to be achieved predominantly through dentoalveolar mechanisms. This observation is partially consistent with the findings of Blackham [31] and Koukou et al. [19], who suggested that the mandibular advancement capacity of aligner-based systems may be limited, yet still clinically meaningful. Caruso et al. [18] reported that, in short-term treatment outcomes, the reduction in ANB angle was more pronounced in the Twin Block group (−5.6°) compared with the MA group (−3.4°). Conversely, Blackham [31] demonstrated that, from a skeletal perspective, the MA group did not exhibit outcomes substantially different from those observed in the Twin Block group. These findings suggest that, while the primary effects of MA therapy are concentrated at the dentoalveolar level, a limited skeletal contribution may also occur under specific clinical conditions. In addition, Ravera et al. [32] reported that treatment effects varied according to the patients’ growth stage, showing that aligner-based therapy primarily induced dentoalveolar changes at the CVM2 stage, whereas a more pronounced skeletal contribution was observed at the CVM3 stage.

In the PowerScope group, the sagittal correction appeared to be relatively limited; however, this appliance demonstrated a more pronounced effect at the dentoalveolar level. Kalra et al. [33] reported that PowerScope primarily contributes to sagittal correction through dental mechanisms, particularly by inducing mandibular incisor proclination and maxillary molar retraction. Consistent with these observations, the present study showed increases in L1–NB and IMPA values in the PowerScope group, suggesting a predominant dentoalveolar response. With respect to overjet and overbite, reductions were observed across all treatment groups. A relatively greater reduction in overjet was noted in the digital Herbst group, which may be related to its dentoalveolar effects, including maxillary incisor retraction and mandibular incisor proclination. Regarding vertical facial dimensions, an overall increase was observed in the Twin Block and digital Herbst groups, whereas changes appeared to be more limited in the MA group. These findings are in line with experimental studies conducted in animal models, which have suggested that functional appliances may enhance mandibular growth, particularly in the vertical dimension [34,35].

Changes in the vertical dimension have also been reported to be associated with the vertical movements of the molars. Both the Herbst appliance and aligner-based systems have been reported to induce intrusion of the maxillary molars, thereby partially compensating for the clockwise rotation of the mandible resulting from occlusal opening [36,37]. In the study conducted by Caruso et al. [18] it was reported that neither the Herbst nor the MA appliance caused a significant change in the inclination of the mandibular plane relative to the Frankfurt horizontal or SN plane. These results indicate that the vertical effects of functional appliances may vary depending on the type of appliance, the patient’s growth stage, and the treatment protocols applied.

In the soft tissue evaluations, an increase in lower lip projection and a significant decrease in the UL–E Plane distance were observed in the MA group. This finding is consistent with the results reported by Caruso et al. [18] and Koukou et al. [19] who indicated that aligner-based MA systems have the potential to improve the aesthetic profile. In the PowerScope and Herbst groups, a decrease in upper lip protrusion and an increase in lower lip protrusion were observed, both of which were statistically significant. These changes can be explained by the anterior positioning of the mandible and the slight retroclination of the maxillary incisors induced by functional appliances.

In our study, soft tissue changes were observed to be most pronounced in the Twin Block group. Similarly, Baysal and Uysal [38], reported that in patients treated at the peak of the pubertal growth spurt, soft tissue changes achieved with the Twin Block appliance were more prominent compared to those obtained with the Herbst appliance, particularly demonstrating greater advancement of the lower lip and pogonion points. Almeida et al. [39] demonstrated that in 57 patients with Class II Division 1 malocclusion, treatment with the Herbst appliance over a 12-month period resulted in a reduction in facial convexity, an increase in the mentolabial angle, and retraction of the upper lip compared to untreated controls. These findings are consistent with the improvements in lip–chin relationships observed in the Herbst and Twin Block groups in our study and are further supported by the positive effects of functional appliances on soft tissues reported by Wu et al. [40].

The different response patterns observed among the treatment groups in the present study may be related to variations in appliance design and force transmission mechanisms. Previous studies have emphasized that fabrication methods and structural characteristics of functional appliances play a role in shaping the balance between dentoalveolar and skeletal effects [41]. In this context, the transmission of forces predominantly through dentoalveolar structures in archwire-integrated systems such as PowerScope, compared with the full-coverage clear aligner design that may help limit dentoalveolar compensation, suggests that treatment responses could vary according to appliance geometry and biomechanical behavior [22,32]. Similarly, in Herbst appliance designs based on a telescopic piston mechanism, factors such as anchorage configuration and the presence of interocclusal components have been reported to influence the nature of sagittal and vertical corrections, whereas in removable Twin Block designs, functional mandibular positioning may be more closely associated with underlying growth patterns [25,42,43].

Our study has certain limitations. Since the analyses were based solely on two-dimensional cephalometric measurements, it was not possible to assess asymmetric growth patterns or three-dimensional morphological variations in the soft tissues. In addition, the absence of a control group limits the ability to distinguish growth-related changes, and the long-term effects of the appliances were not evaluated within the scope of this study. In addition, the small sample size in each group (n = 7) reflects the pilot nature of the study and limits the statistical power of the analyses. Furthermore, given the evaluation of multiple outcome variables without formal adjustment for multiple comparisons, the risk of Type I error cannot be excluded. Accordingly, the study is underpowered to detect small-to-moderate intergroup differences, and statistically significant post hoc findings may be susceptible to both Type I (false positive) and Type II (false negative) errors. The presence of significant intergroup differences in certain variables at baseline (T0) represents another factor that may have influenced the interpretation of treatment outcomes. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution and considered exploratory and hypothesis-generating rather than confirmatory.

Future studies with larger sample sizes, prospective designs, three-dimensional imaging support, and long-term follow-up evaluations may allow for a more comprehensive assessment of the effect profiles of different functional appliances.

5. Conclusions

Given the retrospective pilot design and limited sample size, the following findings should be interpreted cautiously.

- An increase in mandibular length (Co–Gn) was observed in all treatment groups, with the greatest mean change identified in the Twin Block group.

- The PowerScope appliance demonstrated more pronounced dentoalveolar changes compared with the other functional appliances.

- Among the treatment groups, the mandibular advancement (MA) appliance showed relatively stable vertical facial height measurements throughout the treatment period.

- Changes in overjet and overbite were observed across all groups, with the greatest mean reductions identified in the Herbst group.

- The design and material characteristics of different functional appliances may influence the dentoskeletal and soft tissue responses observed during treatment. Therefore, individualizing appliance selection not only according to skeletal treatment objectives but also based on the biomechanical properties of the materials used and the patient’s specific expectations may be beneficial for achieving favorable treatment outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16020756/s1, Table S1: Comparison of Cephalometric Parameters at T0 and T1, and Statistical Analysis of Intragroup and Intergroup Differences; Table S2: Post hoc pairwise comparisons between treatment modalities.

Author Contributions

İ.Ö.K.: Conceptualization, validation, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, visualization; M.K.A.: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, writing—review and editing; T.S.E.: Conceptualization, validation, investigation, writing—review and editing project administration; F.E.: Formal analysis; E.İ.K.: Conceptualization, methodology, resources; A.T.: Resources. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Non-Invasive Research Ethics Committee approved this study of Kırıkkale University (Decision No: 2025.06.30).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent to participate was obtained from all the participants in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cozza, P.; Baccetti, T.; Franchi, L.; De Toffol, L.; McNamara, J.A. Mandibular changes produced by functional appliances in Class II malocclusion: A systematic review. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2006, 129, 599.e1–599.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Rego, M.V.N.N.; Martinez, E.F.; Coelho, R.M.I.; Leal, L.M.P.; Thiesen, G. Perception of changes in soft-tissue profile after Herbst appliance treatment of Class II Division 1 malocclusion. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2017, 151, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Pan, Y.; Lin, T.; Lu, H.; Ai, H.; Mai, Z. Comparison of cephalometric measurements of the Twin Block and A6 appliances in the treatment of Class II malocclusion: A retrospective comparative cohort study. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruf, S.; Pancherz, H. When is the ideal period for Herbsttherapy—Early or late? Semin. Orthod. 2003, 9, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bishara, S.E.; Ziaja, R.R. Functional appliances: A review. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1989, 95, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahm, G.; Bartsch, A.; Witt, E. Micro-electronic monitoring of functional appliance wear. Eur. J. Orthod. 1990, 12, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segnini, C.; D’Antò, V.; Antonio, N.; Roser, C.J.; Knode, V.; Björn, L. 3D printed removable functional appliances for early orthodontic treatment—Possibilities and limitations. Semin. Orthod. 2023, 29, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, W.J. The twin block traction technique. Eur. J. Orthod. 1982, 4, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moro, A. Simplified correction of Class II using PowerScope. Orthotown 2016, 9, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Antony, T.; Amin, V.; Hegde, S.; Hegde, S.; Shetty, D.; Khan, M.B. The Evaluation and Clinical Efficiency of Power Scope: An Original Research. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2018, 8, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singaraju, G.; Vannala, V.; Ankisetti, S.; Mandava, P.; Ganugapanta, V.; Unnam, D. Evaluation of sagittal changes in Class II Div 2 patients with decelerating phase of growth by PowerScope appliance: A retrospective cephalometric investigation. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2019, 11, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, A.; Borges, S.W.; Spada, P.P.; Morais, N.D.; Correr, G.M.; Chaves, C.M., Jr.; Cevidanes, L.H.S. Twenty-year clinical experience with fixed functional appliances. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2018, 23, 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarraf, N.E.; Ali, D.M. Present and the future of digital orthodontics. Semin. Orthod. 2018, 24, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mortadi, N.; Eggbeer, D.; Lewis, J.; Williams, R.J. CAD/CAM/AM applications in the manufacture of dental appliances. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2012, 142, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, S.; Tarraf, N.E.; Kravitz, N.D. Three-dimensional metal printed orthodontic laboratory appliances. Semin. Orthod. 2021, 27, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, S.; Cornelis, M.A.; Hauber Gameiro, G.; Cattaneo, P.M. Computer-aided design and manufacture of hyrax devices: Can we really go digital? Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2017, 152, 870–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ender, A.; Attin, T.; Mehl, A. In vivo precision of conventional and digital methods of obtaining complete-arch dental impressions. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2016, 115, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, S.; Nota, A.; Caruso, S.; Severino, M.; Gatto, R.; Meuli, S.; Mattei, A.; Tecco, S. Mandibular Advancement with Clear Aligners in the Treatment of Skeletal Class II. A Retrospective Controlled Study. 2021. Available online: https://iris.unisr.it/handle/20.500.11768/120397 (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Koukou, M.; Damanakis, G.; Tsolakis, A.I. Orthodontic Management of Skeletal Class II Malocclusion with the Invisalign Mandibular Advancement Feature Appliance: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep. Dent. 2022, 2022, 7095467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, C.M.; McCulloch, K.J. Treatment effects of the twin block appliance: A cephalometric study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1998, 114, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenouth, M.J. Cephalometric evaluation of the Twin-block appliance in the treatment of Class II Division 1 malocclusion with matched normative growth data. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2000, 117, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, V.; Sharma, R.; Chowdhary, S. Comparative evaluation of treatment effects between two fixed functional appliances for correction of Class II malocclusion: A single-center, randomized controlled trial. Angle Orthod. 2018, 88, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Liu, X.Q. Efficacy of invisible advancement correction for mandibular retraction in adolescents based on Pancherz analysis. World J. Clin. Cases 2023, 11, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruf, S.; Pancherz, H. Herbst/multibracket appliance treatment of Class II division 1 malocclusions in early and late adulthood. a prospective cephalometric study of consecutively treated subjects. Eur. J. Orthod. 2006, 28, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruf, S.; Pancherz, H. The mechanism of Class II correction during Herbst therapy in relation to the vertical jaw base relationship: A cephalometric roentgenographic study. Angle Orthod. 1997, 67, 271–276. [Google Scholar]

- Pangrazio, M.N.K.; Pangrazio-Kulbersh, V.; Berger, J.L.; Bayirli, B.; Movahhedian, A. Treatment effects of the mandibular anterior repositioning appliance in patients with Class II skeletal malocclusions. Angle Orthod. 2012, 82, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koretsi, V.; Zymperdikas, V.F.; Papageorgiou, S.N.; Papadopoulos, M.A. Treatment effects of removable functional appliances in patients with Class II malocclusion: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Orthod. 2015, 37, 418–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliades, T.; Panayi, N.; Papageorgiou, S.N. From biomimetics to smart materials and 3D technology: Applications in orthodontic bonding, debonding, and appliance design or fabrication. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2023, 59, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, B.J.; Tai, S.K.; Blevins, R.; Daher, S. Prospective multicenter investigation of Invisalign treatment with the mandibular-advancement feature: An interim report. J. Clin. Orthod. 2022, 56, 458–463. [Google Scholar]

- Zybutz, T.; Drummond, R.; Lekic, M.; Brownlee, M. Investigation and comparison of patient experiences with removable functional appliances. Angle Orthod. 2021, 91, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackham, S.S. A Study of Short-Term Skeletal, Dental, and Soft Tissue Effects of Class II Malocclusions Treated with Invisalign ® with Mandibular Advancement Feature or Twin Block Appliance Compared with Historical Controls. University of British Columbia. 2020. Available online: https://open.library.ubc.ca/soa/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/24/items/1.0392341 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Ravera, S.; Castroflorio, T.; Galati, F.; Cugliari, G.; Garino, F.; Deregibus, A.; Quinzi, V. Short term dentoskeletal effects of mandibular advancement clear aligners in Class II growing patients. A prospective controlled study according to STROBE Guidelines. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2021, 22, 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Kalra, A.; Swami, V.; Bhosale, V. Treatment effects of “PowerScope” fixed functional appliance—A clinical study. Folia Med. 2021, 63, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Duncan, W.J.; Farella, M. Evaluation of mandibular growth using cone-beam computed tomography in a rabbit model: A pilot study. New Zealand Dent. J. 2012, 108, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Yuan, L.; Liu, J.; Mao, L.; Xia, L.; Fang, B. Hemifacial microsomia treated with a hybrid technique combining distraction osteogenesis and a mandible-guided functional appliance: Pilot study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2019, 155, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talens-Cogollos, L.; Vela-Hernández, A.; Peiró-Guijarro, M.A.; García-Sanz, V.; Montiel-Company, J.M.; Gandía-Franco, J.L.; Bellot-Arcís, C.; Paredes-Gallardo, V. Unplanned molar intrusion after Invisalign treatment. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2022, 162, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.; Ojima, K.; Dan, C.; Upadhyay, M.; Alshehri, A.; Kuo, C.L.; Mu, J.; Uribe, F.; Nanda, R. Evaluation of open bite closure using clear aligners: A retrospective study. Prog. Orthod. 2020, 21, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baysal, A.; Uysal, T. Soft tissue effects of Twin Block and Herbst appliances in patients with Class II division 1 mandibular retrognathy. Eur. J. Orthod. 2013, 35, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, M.R.; Flores-Mir, C.; Brandão, A.G.; de Almeida, R.R.; de Almeida-Pedrin, R.R. Soft tissue changes produced by a banded-type Herbst appliance in late mixed dentition patients. World J. Orthod. 2008, 9, 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Xia, Y.; Wang, B.; Chen, S.; Gu, K.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, M. Does mandibular advancement with clear aligners have the same skeletal and dentoalveolar effects as traditional functional appliances? BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, A.K.; Duggal, R. Treatment effects of twin-block and mandibular protraction appliance-IV in the correction of class II malocclusion. Angle Orthod. 2010, 80, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt, D.R.; McNamara, J.A.; Baccetti, T. Maxillary molar distalization or mandibular enhancement: A cephalometric comparison of comprehensive orthodontic treatment including the pendulum and the Herbst appliances. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2003, 123, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proffit, W.R.; Fields, H.; Larson, B.; Sarver, D.M. Contemporary Orthodontics—E-Book; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.