Abstract

Rubber particles have been proven to have the advantages of improving the energy absorption effect and enhancing the friction between soil particles when used to modify the soil. The rubber-modified soil technology also provides a new solution for the pollution-free disposal of waste rubber. However, when rubber particles are used to modify collapsible loess, they cannot significantly enhance its strength. Previous studies have not systematically clarified whether combining rubber particles with different cementation mechanisms can overcome this limitation, nor compared their shear mechanical effectiveness under identical conditions. In view of this, a dual synergistic strategy is implemented by combining rubber with lime and rubber with enzyme-induced calcium carbonate precipitation (EICP). Direct shear tests and scanning electron microscopy are used to evaluate four modification approaches: rubber alone, lime alone, rubber with EICP, and rubber with lime. Accordingly, shear strength, cohesion, and internal friction angle are quantified. At a vertical normal stress of 100 kPa and above, samples modified with rubber and lime (7–9% lime and 6–8% rubber) achieve peak shear strength values of 200–203 kPa, representing an 86.4% increase compared to rubber alone. Microscopic analysis reveals that calcium silicate hydrate gel effectively anchored rubber particles, forming a composite structure with a rigid skeleton and elastic buffer. In comparison, the rubber and EICP group (10% rubber) shows a substantial increase in internal friction angle (24.25°) but only a modest improvement in cohesion (16.5%), which is due to limited continuity in the calcium carbonate bonding network. It should be noted that the performance of EICP-based modification is constrained by curing efficiency and reaction continuity, which may affect its scalability in conventional engineering applications. Overall, the combination of rubber and lime provided an optimal balance of strength, ductility, and construction efficiency. Meanwhile, the rubber and EICP method demonstrates notable advantages in environmental compatibility and long-term durability, making it suitable for ecologically sensitive applications. The results offer a framework for loess stabilization based on performance adaptation and resource recycling, supporting sustainable use of waste rubber in geotechnical engineering.

1. Introduction

Loess in China is primarily distributed across the northwestern, northern, and northeastern regions and is characterized by aeolian deposition as well as a porous, multi-structured fabric. In its natural state, this distinctive physical structure endows loess with relatively high strength. However, when exposed to water, the dissolution of soluble carbonates leads to rapid degradation of the soil structure, resulting in hydro-collapse, landslides, and other geohazards that pose serious threats to engineering safety. In response to the geological conditions and engineering demands in loess regions, extensive studies were conducted both domestically and internationally. Xu Zhangjian et al. [1] focused on loess landslides and systematically analyzed their distribution patterns, classifications, and formation mechanisms, highlighting the critical role of loess properties in landslide initiation and evolution. Yao Qinglin [2] conducted zonation studies on earthquake-induced landslides in northwestern China and revealed the influence of geological structures and topography on landslide susceptibility. Chen Yongming et al. [3] investigated loess landslides triggered by historical strong earthquakes and emphasized that seismic landslides represent the predominant earthquake-induced hazard in loess regions. These studies provide an important scientific basis for geohazard prevention and engineering construction in loess regions. Nevertheless, the mechanisms governing loess failure under multi-factor coupling conditions—particularly the interactions among water infiltration, stress states, and material heterogeneity—remain insufficiently understood. Consequently, enhancing the mechanical properties and water stability of loess through effective and sustainable improvement technologies remains imperative.

Traditional chemical improvement methods, such as cement, lime, and fly ash, have been widely applied as stabilizing agents. Jefferson et al. [4] applied cement–loess mixtures for soil replacement treatment and reported a significant reduction in collapsibility accompanied by improved bearing capacity. Yang Zhongcheng et al. [5] demonstrated that, with increasing curing age, the compression coefficient of cement-stabilized loess decreased while the compression modulus increased, and that specimens stabilized with 5% cement exhibited optimal water stability. Jia et al. [6] reported that calcium sulfoaluminate cement exhibits advantages such as low-temperature production, early strength development, and reduced carbon emissions, and that its unconfined compressive strength can exceed 0.7 MPa after one day of curing when combined with lime or fly ash. Zhou Jianji et al. [7] found that loess stabilized with 7% lime exhibited minimal compressibility and nearly eliminated collapsibility, whereas excessive lime content resulted in abnormal expansion due to free lime hydration. Li Zhiqing et al. [8] investigated lime–fly ash–loess mixtures and reported that fly ash and loess jointly formed a dense microstructure, while lime activated the pozzolanic activity of fly ash to generate hydration products, thereby enhancing cohesion and reducing shrinkage.

In addition to cement- and fly ash-based systems, the bentonite–lime combination has attracted increasing attention. Gao Mengna et al. [9] revealed, through unconfined compressive strength tests and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis, that bentonite effectively filled soil pores while lime formed a cementitious structure, resulting in a strength increase of approximately 4.01 times and a significant reduction in porosity. Guo Tingting et al. [10] observed that, among lime–fly ash–loess mixtures with varying fly ash contents, the mixture with a volumetric ratio of 1:2:7 exhibited the highest shear strength, although prolonged curing was required to activate the pozzolanic reaction. Zhang Yuchuan et al. [11] further reported that the long-term permeability of lime–fly ash–loess mixtures decreased with curing time; however, limited clay content restricted fly ash activation, resulting in early strength values of only 60–80% of those of lime-stabilized loess. Almuaythir et al. [12] conducted a mechanistic comparison of lime stabilization and alternative reinforcement approaches and emphasized that lime-induced pozzolanic reactions primarily enhance soil cohesion through chemical bonding. These findings highlight the necessity of distinguishing chemically dominated cementation mechanisms from physically dominated reinforcement pathways.

Despite their effectiveness, traditional stabilization methods generally enhance shear strength by increasing soil cementation and stiffness. However, these methods are often associated with high carbon emissions, increased brittleness, and reduced deformation tolerance, particularly under medium to high stress levels or cyclic loading conditions. Consequently, increasing attention is directed toward alternative or composite modification strategies that aim to balance strength enhancement with deformation capacity.

In recent years, microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation (MICP) has attracted increasing attention owing to its environmentally friendly and sustainable characteristics. Whiffin et al. [13] first applied MICP to sand reinforcement and reported a significant improvement in compressive strength. Qabany et al. [14] demonstrated that the concentration of the cementation solution strongly affects solidification performance; however, MICP requires stringent bacterial cultivation conditions and exhibits poor permeability in fine-grained soils [15,16]. To overcome these limitations, enzyme-induced calcium carbonate precipitation (EICP) has been developed by replacing microbial activity with plant-derived urease, thereby simplifying the treatment process and improving cementation uniformity. Chen et al. [17] conducted systematic experiments on rubber–clay mixtures treated with EICP and showed that, although rubber particles partially inhibited carbonate precipitation efficiency, their incorporation significantly enhanced shear-related mechanical parameters. Meng et al. [18] achieved a fourfold increase in calcium carbonate generation through a multi-stage grouting process, with the unconfined compressive strength of treated sand exceeding 10 MPa. Zhang et al. [19] compared different calcium sources and found that aragonite crystals formed by EICP optimized pore structure and improved both compressive and tensile strength. He [20], Neupane [21], Almajed [22], Yuan Pengbo [23], and Wang Haozhe [24] further confirmed the effectiveness of EICP in improving soil mechanical properties. Nevertheless, most EICP-related studies have primarily focused on compressive strength, permeability reduction, or environmental feasibility, whereas the contributions of EICP treatment to individual shear strength components—particularly cohesion and internal friction angle—remain insufficiently clarified.

The reutilization of waste tire resources provides an additional pathway for loess improvement. Globally, approximately 9 million tons of waste tires are generated each year, with a recycling rate of only 15–20%. In 2022, China alone produced 12.28 million tons of waste tires, of which 6.75 million tons were recycled [25]. Edil et al. [26] found that soils mixed with tire shreds exhibit enhanced elasticity, while Lee et al. [27] verified the engineering potential of rubber–sand mixtures through triaxial testing. Hu et al. [28] reported that rubber inclusions improve deformation resistance and stability while simultaneously reducing environmental burdens. Deng An et al. [29] observed that moderate rubber contents (10–20%) significantly enhance shear strength, whereas excessive rubber content leads to strength degradation [30,31]. To balance strength enhancement and deformation capacity, rubber particles have been combined with EICP treatment. Wang Yi et al. [32] and Zhang Jianwei et al. [33] demonstrated that rubber–EICP systems can simultaneously enhance strength and deformability, although the influence of rubber particles on EICP efficiency remains unclear. Chen et al. [34] further showed that calcium carbonate crystals formed network-like cementation structures on rubber surfaces and within soil pores, thereby achieving synergistic enhancement of strength and flexibility. Al-Mahbashi et al. [35] investigated lime-stabilized clayey soils incorporating waste rubber and demonstrated that rubber particles improved shear capacity and deformation tolerance primarily through physical interaction rather than chemical participation. Chai Shaobo et al. [36,37] further examined the dynamic mechanical properties of rubber–EICP-modified loess and highlighted its vibration reduction potential.

Lime stabilization remains one of the most widely adopted techniques for loess improvement. However, when rubber particles are incorporated into lime-stabilized loess, their role differs fundamentally from that of conventional mineral aggregates. Rubber particles are chemically inert in alkaline environments and interact with lime-treated loess primarily through physical embedding, stress redistribution, and interfacial friction. Existing studies on rubber–lime systems often treat rubber as a secondary additive and rarely examine the coupled effects of rubber and lime contents on shear parameters and failure mechanisms.

Based on the above analysis, several unresolved issues remain. The shear mechanical behavior of rubber–lime-modified loess under varying mix proportions has not been systematically clarified. Direct comparisons between rubber–lime and rubber–EICP systems in terms of their contributions to cohesion and internal friction angle are scarce. Moreover, the fundamentally different reinforcement pathways of chemical cementation and biomineralization require further elucidation. It is therefore hypothesized that rubber particles primarily enhance shear resistance through physical buffering and frictional effects, whereas lime-induced cementation predominantly contributes to cohesion, and that rubber–lime and rubber–EICP systems exhibit distinct shear reinforcement mechanisms.

It is therefore hypothesized that rubber particles primarily enhance shear resistance through physical buffering and frictional effects, whereas lime-induced cementation predominantly contributes to cohesion, and that rubber–lime and rubber–EICP systems exhibit distinct shear reinforcement mechanisms. Accordingly, this study aims to: (i) investigate the shear mechanical behavior of loess modified with lime and rubber under varying mix proportions and stress conditions; (ii) quantitatively distinguish the respective contributions of cohesion and internal friction angle in lime-only, rubber-only, rubber–EICP, and rubber–lime systems; (iii) elucidate the synergistic and contrasting reinforcement mechanisms associated with chemical cementation, biomineralization, and rubber-induced physical buffering.

2. Experimental Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

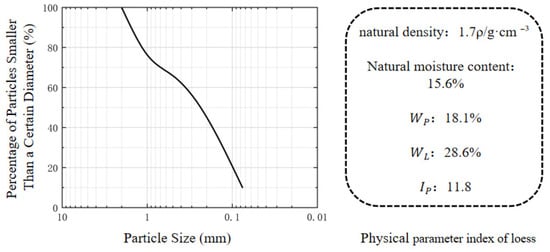

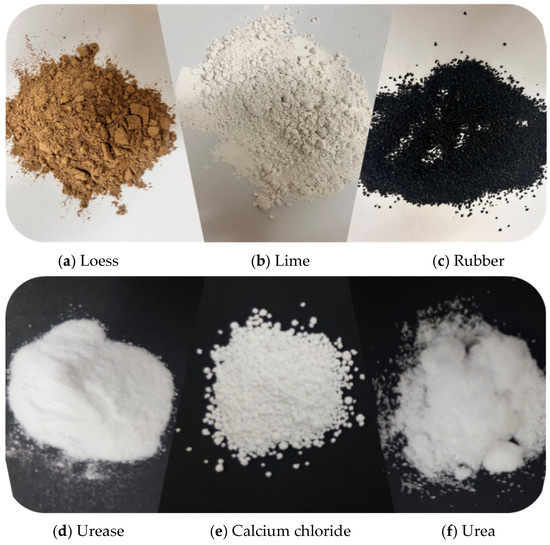

The loess used in this study is collected from an undisturbed layer at a depth of 10 m in a foundation pit located in the Chang’an District of Xi’an, China. The soil is predominantly composed of silt-sized particles, with a liquid limit of 28.6% and a plastic limit of 18.1%, and exhibits typical collapsible behavior. The particle size distribution curve and basic physical properties are shown in Figure 1. The lime employed is hydrated lime powder with a particle size of 200–300 mesh, a Ca(OH)2 content of 90–95%, a residual CaO content of 3–5%, an apparent density of 220–230 kg/m3, a particle passing rate of 85–90%, and a saturated solution pH ranging from 12.4 to 12.8, meeting the requirements for high-activity cementitious materials. The rubber particles consist of regenerated rubber with a particle size range of 1–2 mm, a density of 1.03 g/cm3, and an elastic modulus of 3 MPa. Regarding rubber particle size selection, previous studies on rubber–EICP-modified loess demonstrate that particles within the range of 1–2 mm provide an optimal balance between shear strength enhancement and material dispersion. Smaller particles (<1 mm) tend to behave as fine fillers with limited stress-buffering capacity, whereas larger particles (>2 mm) are prone to segregation and the formation of localized weak zones. Therefore, rubber particles with a size of 1–2 mm are adopted to ensure uniform mixing, stable soil–rubber interfacial contact, and optimal mechanical performance. The materials used in the tests are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Grain size distribution curve and physical properties of loess.

Figure 2.

Experimental materials.

For the EICP treatment, urease is extracted from jack beans with an enzymatic activity of 1 U/mg and is stored at 2–8 °C to maintain catalytic activity. The cementation solution is prepared by mixing 0.5 mol/L calcium chloride and 1.2 mol/L urea at a volume ratio of 1:1 to induce calcium carbonate precipitation through biomineralization. The EICP formulation—consisting of a urease concentration of 200 g/L and a cementation solution concentration of 1 mol/L—is selected based on prior experimental optimization. This formulation ensures sufficient calcium carbonate precipitation within a 72 h curing period while maintaining reaction controllability and uniformity, thereby providing a reliable basis for comparison with the rubber–lime system under identical testing conditions.

The lime content is designed using a cross-combination scheme with rubber content, with both components increased stepwise. This design allows systematic exploration of the coupled effects of lime-induced cementation and rubber-induced elastic buffering, rather than evaluating each material independently. The selected lime content range (3–11%) covers commonly reported effective dosages for loess stabilization, enabling identification of an optimal combination while avoiding insufficient cementation at low contents and excessive brittleness at high contents.

2.2. Sample Preparation

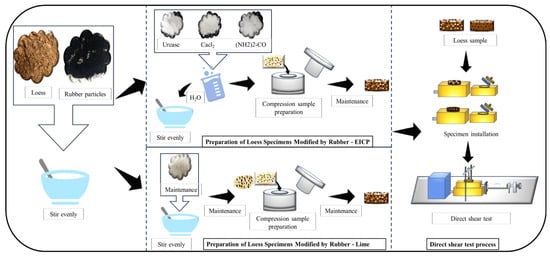

The specimen preparation process is designed with loess as the primary material, with three modification groups: (i) a rubber-only group; (ii) a rubber–EICP combined modification group; (iii) a rubber–lime combined modification group.

First, the undisturbed loess is oven-dried at 105 °C, ground, and passed through a 2 mm sieve to remove coarse particles. The materials are then mixed according to the designated proportions. For the lime–rubber combined modification group, predetermined volumes of hydrated lime powder and rubber particles are weighed accordingly and gradually added to the loess, followed by thorough dry mixing until homogeneity is achieved. The rubber alone group is prepared by mixing loess and rubber particles based solely on the specified rubber volume ratio. For the rubber-EICP combined modification group, the mixing water is replaced with an equal volume of urease solution and cementation solution (urease activity: 1 U/mg; cementation solution composed of 0.5 mol/L CaCl2 and 1.2 mol/L urea at a 1:1 volume ratio, pH adjusted to 7.4). The mixture is stirred twice to promote the biomineralization reaction. All modified loess samples are adjusted to an optimal moisture content of 16% using purified water (or EICP reagents). The specimens are compacted in layers using a standard cutting-ring compactor (61.8 mm × 20 mm) and compressed to a 95% degree of compaction using a hydraulic jack. After molding, the specimens are sealed and cured in a constant temperature and humidity chamber (with temperature 25-30 °C, relative humidity ≥ 95%) for 72 h to ensure full cementation reaction. Control groups (lime alone, rubber alone, and Undisturbed loess) are prepared following the same procedure, with only material ratios adjusted to maintain consistency and data comparability. The specimen preparation process is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Specimen preparation and experimental procedure.

2.3. Experimental Instruments and Experimental Protocols

The shear strength tests of the modified loess are conducted using a ZJ-type strain-controlled direct shear apparatus. A total of five specimen categories are tested, including undisturbed loess, rubber-alone specimens (with rubber contents of 4%, 6%, 8%, and 10%), lime-alone specimens (with lime contents of 3%, 5%, 7%, 9%, and 11%), rubber–lime combined specimens (5 × 4 cross combinations, with lime contents of 3%, 5%, 7%, 9%, and 11% paired with rubber contents of 4%, 6%, 8%, and 10%, resulting in 20 groups), and rubber–EICP combined specimens (with rubber contents of 4%, 6%, 8%, and 10% treated using a urease concentration of 200 g/L and a cementation solution concentration of 1 mol/L). The direct shear tests are performed in accordance with the Chinese national standard GB/T 50123 [38], which is widely adopted in geotechnical engineering practice in China. According to this standard, fast direct shear tests for fine-grained soils are typically conducted at shear rates ranging from approximately 0.8 to 1.2 mm/min. In this study, a shear rate of 0.8 mm/min is selected to represent the conventional fast-shear condition. Vertical normal stresses of 50, 100, 200, and 300 kPa are applied sequentially. The peak shear strength, residual shear strength, cohesion (c), and internal friction angle (φ) are determined under each test condition to evaluate the improvement effects systematically. The detailed testing scheme is summarized in Table 1. For each test condition, at least three parallel specimens are prepared and tested, and the reported shear strength parameters represent averaged values to ensure repeatability and reliability of the experimental results.

Table 1.

Test scheme for shear characteristics.

3. Shear Properties of Loess Improved by Rubber–Lime Combination

As a key indicator for evaluating the engineering stability of loess, shear strength directly reflects the combined effects of lime cementation, EICP-induced mineralization, and the elastic buffering of rubber particles. This section focuses on the shear strength responses of four modification approaches—rubber alone, lime alone, rubber–EICP combined, and rubber–lime combined—under different vertical normal stresses (50–300 kPa) and dosage gradients. By examining variations in peak shear strength and the relative contributions of cohesion and internal friction angle, the intrinsic differences among the reinforcement mechanisms are identified. All shear strength parameters discussed in this section are obtained under identical fast direct shear conditions specified by GB/T 50123, ensuring comparability among different modification methods.

3.1. Variation Pattern of Shear Strength

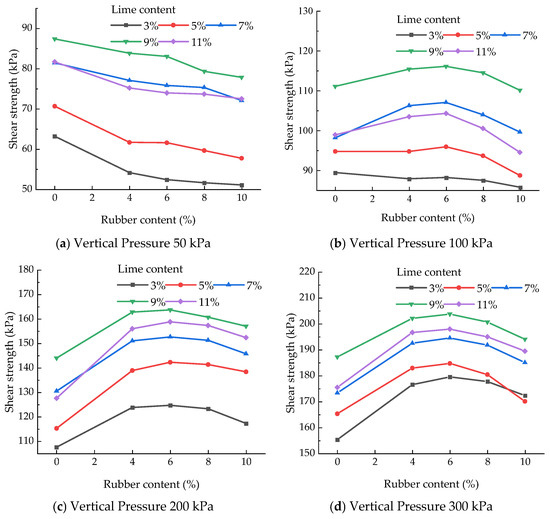

Variations in the shear strength of lime–rubber-modified loess with different rubber and lime contents are investigated through direct shear tests. The objective is to identify the optimal mixing ratio range by comprehensively evaluating the influence of rubber and lime contents on shear performance. The evolution of shear strength under different vertical normal stresses is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Variation in shear strength of specimens with lime content.

When the vertical normal stress is 50 kPa, the shear strength of lime-modified loess is significantly higher than that of the lime–rubber composite specimens. As the vertical normal stress increases to 100 kPa and above, the shear strength of the composite specimens gradually exceeds that of the lime-alone group. At vertical normal stresses of 200 and 300 kPa, the shear strength of the composite specimens, under the same lime content, first increases and then decreases with increasing rubber content, with peak values generally observed at rubber contents of 6–8%. When the rubber content is held constant, the shear strength exhibits a similar trend with increasing lime content, increasing initially and then decreasing, with optimal performance observed at a lime content of 9%, while specimens with 7% and 11% lime show comparable values. Considering material efficiency and economic feasibility, the lime content is considered appropriate within the range of 7–9%. Overall, the combined modification achieves the highest shear strength when the rubber content ranges from 6% to 8% and the lime content ranges from 7% to 9%. Outside this range, excessive rubber addition results in a reduction in shear strength, particularly under high vertical normal stresses.

A comprehensive optimization analysis reveals that the combined modification achieves the best shear performance when the rubber content ranges from 6–8% and the lime content ranges from 7–9%, with a notable reduction in material cost. These phenomena are closely related to the synergistic interaction among the materials. At low vertical pressure (50 kPa), the lime-modified soil forms a rigid skeleton through its self-cementation effect, and its shear strength primarily depends on cohesive bonding between soil particles. Under this condition, the elastic characteristics of rubber particles cannot effectively participate in stress transfer. Instead, they reduce the number of particle contacts by replacing part of the soil matrix, thereby weakening the overall strength. With increasing vertical pressure, the advantage of the rubber’s elastic modulus becomes more evident. Its compressive deformation redistributes local stresses, enhances the frictional resistance at the soil–rubber interfaces, and effectively increases the internal friction angle.

Meanwhile, a moderate amount of rubber particles fills the soil pores, improving compactness and structural stability. However, excessive rubber addition (>8%) leads to particle agglomeration and the formation of shear-weak zones, causing strength reduction. The optimization of lime content stems from its cementation effect: insufficient dosage results in poor bonding, while excessive dosage causes over-hardening and micro-crack formation, reducing structural integrity. Under high-pressure conditions, the synergistic effect of lime and rubber reaches its maximum—lime maintains a rigid framework through cementation, while rubber buffers local deformations through elasticity, jointly enhancing the shear performance of the modified loess.

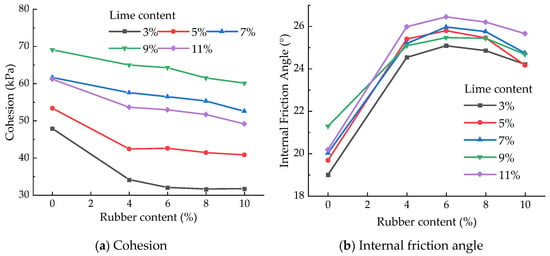

3.2. Interaction Effects of Cohesion and Internal Friction Angle

The variation patterns of cohesion and internal friction angle with different material ratios for the lime–rubber-modified loess are shown in Figure 5. In terms of cohesion, the composite samples consistently exhibit lower values than the lime-alone group. With increasing rubber content, cohesion gradually decreases and tends to stabilize when the rubber content reaches 4–8%. At a fixed rubber content, cohesion first increases and then decreases with rising lime content, with peak values concentrated in the 7–9% range. Conversely, the internal friction angle of the composite samples is consistently much higher than that of the lime-modified soil, reaching its maximum when the rubber content is 6–8%. However, excessive rubber addition (>8%) leads to a reduction in the internal friction angle.

Figure 5.

Variation in cohesion and internal friction angle with lime content.

In contrast, the internal friction angle continuously increases with lime content, attaining its maximum at 11%, though the values within the 7–9% range remain comparably high. Comprehensive analysis of shear strength and cost-effectiveness indicates that a rubber content of 6–8% and a lime content of 7–9% remain the optimal combination, balancing performance improvement and material economy. The above phenomena are governed by the synergistic mechanism between lime and rubber. Lime enhances the inter-particle bonding through its cementation reaction, while the inclusion of rubber particles partially replaces soil grains, disrupting the lime’s cementation network and thereby causing a systematic reduction in cohesion. When the rubber content reaches 4–8%, the pore-filling effect becomes saturated, and cohesion enters a plateau stage. The improvement in the internal friction angle results from the high surface roughness and elastic deformation of rubber particles. A moderate rubber dosage (6–8%) substantially increases frictional resistance along the soil–rubber interfaces and allows elastic deformation to absorb shear energy and delay crack propagation. Nevertheless, excessive rubber incorporation leads to particle agglomeration and the formation of weak shear planes, reducing interfacial friction efficiency. The continuous enhancement of the internal friction angle with lime content is attributed to the cementation capacity of lime. Although high lime content (11%) further strengthens particle bonding, it significantly increases cost, while a 7–9% dosage already establishes a stable structural framework. Through their combined action, lime provides rigid support, and rubber enhances energy dissipation through frictional mechanisms under high vertical pressures, ultimately achieving a comprehensive improvement in the shear performance of the modified loess.

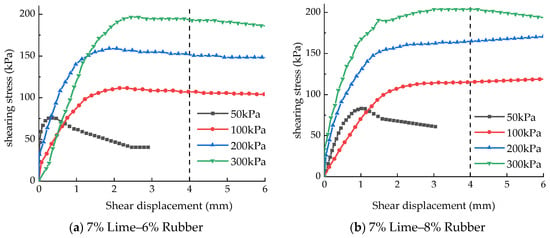

3.3. Optimal Mix Selection and Engineering Applicability Analysis

Based on the variation patterns of shear strength, cohesion, and internal friction angle discussed above, it is determined that the shear performance of the modified loess achieves a comprehensive improvement when the rubber content ranges from 6–8% and the lime content ranges from 7–9%. In the following section, four representative specimens (6% rubber with 7% lime, 6% rubber with 9% lime, 8% rubber with 7% lime, and 8% rubber with 9% lime) are selected for further analysis. The shear displacement–stress curves of these specimens under different vertical pressures are examined to investigate their strain characteristics and to elucidate the deformation behavior of the lime–rubber-modified loess under varying loading conditions.

The differences in strain characteristics exhibited by the four types of lime–rubber composite loess under various vertical pressures are shown in Figure 6. At a vertical pressure of 50 kPa, the shear stress of all specimens increases rapidly with displacement, followed by a sharp decline after reaching the peak value, indicating a distinct strain-softening behavior. As the vertical pressure increases to 100 kPa and above, the shear stress–displacement curves of the specimens progressively shift toward higher displacement regions, accompanied by a significant increase in peak shear stress. Specimens with 7–9% lime and 6–8% rubber contents exhibit a bimodal pattern under 200 kPa, suggesting the occurrence of a multi-stage failure mechanism within the material. At a higher vertical pressure of 300 kPa, all specimens show no apparent post-peak stress drop, demonstrating excellent resistance to continuous deformation and displaying a typical strain-hardening behavior. Figure 6 presents the stress–strain curves of the specimens, and the corresponding strain characteristics under different vertical pressures are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 6.

Shear stress–displacement curves under different vertical pressures.

Table 2.

Statistical summary of specimen strain characteristics.

The above phenomena can be attributed to the evolution of the internal structure of the material. Under low vertical pressure (50 kPa), the failure of the soil is primarily governed by cohesive failure between particles, where lime cementation dominates the initial strength. However, the elastic buffering capacity of the rubber particles is limited, resulting in a sharp post-peak strength drop. As the pressure increases, the advantage of the rubber particles’ elastic modulus becomes more pronounced. The compressive deformation of rubber enables stress redistribution, which effectively delays crack propagation. Meanwhile, at a higher lime content (9%), a dense cemented network is formed, and together with the enhanced frictional interaction provided by the rubber particles, the shear stress is maintained at a relatively stable level over a larger displacement range. The observed bimodal pattern may stem from the staged failure of the soil–rubber contact interfaces and lime-cemented zones. The initial peak corresponds to the fracture of the cementation skeleton, whereas the secondary peak is mainly controlled by the frictional energy-dissipation mechanism of the rubber particles. Under high vertical normal stress, the synergistic interaction between lime and rubber reaches its optimum; the rigid skeleton provided by lime resists shear deformation, while the elastic deformation of rubber absorbs strain energy, ultimately leading to a simultaneous enhancement of shear strength and ductility.

4. Comparison of Shear Performance of Four Types of Improved Loess Technologies

To systematically elucidate the mechanistic differences among the four improvement techniques—rubber alone, lime alone, rubber–EICP composite, and rubber–lime composite—a comprehensive comparative study is conducted in this stage. The variations in shear strength, cohesion, and internal friction angle are examined in conjunction with failure mode observations and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analyses to reveal the performance differentiation trends of the various modification strategies. Particular emphasis is placed on clarifying the functional boundaries between lime-induced cementation and enzyme-induced mineralization when coupled with rubber particles. Lime primarily enhances shear resistance under medium to high normal stresses by establishing a rigid cemented skeleton, whereas EICP treatment mainly improves frictional resistance by promoting interparticle interlocking through carbonate precipitation. To avoid potential bias induced by testing conditions, all comparative shear tests in this section are performed using the same specimen size, loading protocol, and fast-shear rate defined by the national testing standard.

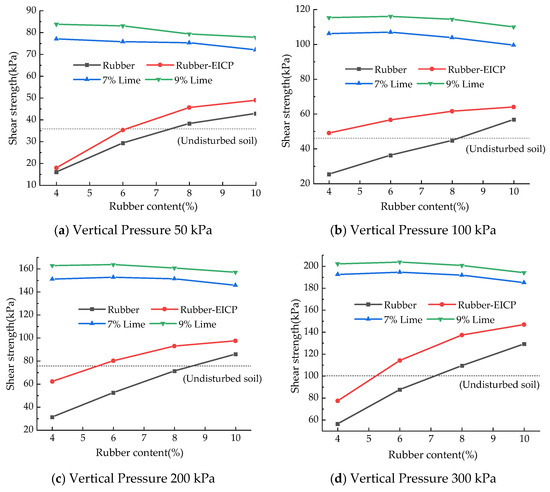

4.1. Comparison of Differences in Shear Strength

The shear strength comparison is first conducted to evaluate the differences among the four improvement methods. Variation patterns of shear strength with increasing rubber content under different vertical normal stresses are investigated for rubber-alone, rubber–EICP composite, and rubber–lime composite specimens with 7% and 9% lime contents. The objective is to identify the modification approach that provides the most effective enhancement in loess shear performance. The corresponding shear strength variation curves are illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Comparison of shear strength variation curves.

Under a vertical pressure of 50 kPa, the shear strength of the rubber-alone specimens increases from 16.05 kPa (4%) to 42.87 kPa (10%) as the rubber content increases, whereas that of the rubber–EICP composite specimens only rises from 17.87 kPa to 48.94 kPa, exhibiting a smaller increment. In contrast, the rubber–lime composite specimens with 7% lime and 9% lime maintain shear strengths in the ranges of 72.06–77.06 kPa and 77.83–83.82 kPa, respectively, significantly exceeding both the rubber-alone specimens and the undisturbed loess (35.88 kPa) [34]. When the vertical pressure increases to 300 kPa, the advantage of lime modification becomes even more pronounced. The specimen with 9% lime and 8% rubber reaches a shear strength of 203.81 kPa, representing an 86.4% increase compared with the rubber-alone specimen (109.35 kPa) and a 48.5% increase relative to the rubber–EICP composite (137.25 kPa).

Although the rubber–EICP composite specimens exhibit lower shear strength than the lime-modified specimens, they show a notable increment at low rubber contents (4–6%). For instance, under 100 kPa, the shear strength of a 6% rubber–EICP specimen reaches 56.6 kPa, compared with 36.26 kPa for the rubber-alone specimen, demonstrating its unique potential within specific content ranges [34,37]. These observations can be attributed to differences in the synergistic mechanisms of the modification methods. Rubber-alone modification enhances shear strength primarily through frictional reinforcement; however, its loose structure cannot form a stable skeleton, limiting strength improvement. EICP technology increases particle bonding by filling pores with calcium carbonate precipitates, yet its mineralization efficiency is constrained by environmental conditions, and at high contents, cementation tends to saturate.

In contrast, lime modification establishes a rigid skeleton via a strong cementation reaction, significantly enhancing both cohesion and internal friction angle. Under high-pressure conditions (e.g., 300 kPa), the synergy between the lime skeleton and the elastic deformation of rubber particles optimizes shear strength and ductility simultaneously. Thus, the lime skeleton provides rigid support, while rubber particles redistribute stress to delay crack propagation. Furthermore, the optimized lime content range of 7–9% avoids excessive hardening-induced brittleness while maximizing the cementation network density, which underlies its superior performance over other modification approaches.

In summary, the rubber–lime composite demonstrates an irreplaceable comprehensive advantage under high-pressure and properly proportioned conditions, whereas EICP technology shows promising potential in low-carbon, low-content applications.

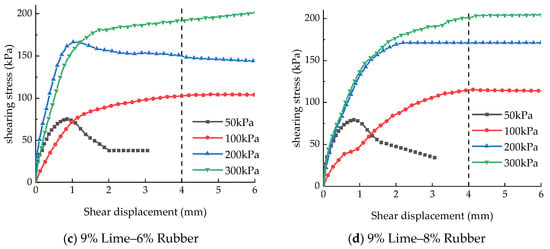

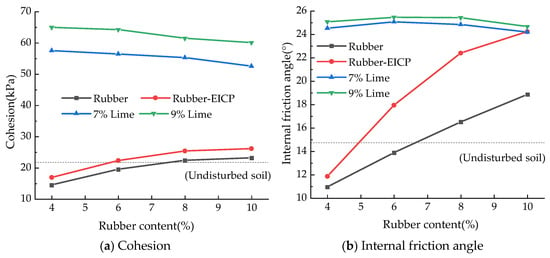

4.2. Comparison of Differences in Cohesion and Internal Friction Angle

Based on the shear strength analysis, this section further investigates the variation patterns of cohesion and internal friction angle with increasing rubber content for four improvement methods: 7% lime, 9% lime, rubber-alone, and rubber–EICP composite. In this study, the rubber-alone modification is consistently adopted as the baseline, and the growth rates of cohesion and internal friction angle for the remaining three modification approaches are calculated to quantitatively evaluate their relative enhancement effects. The differences in the mechanisms underlying cohesion and internal friction angle improvement among the four methods are illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Comparison of cohesion and internal friction angle variation curves.

In terms of cohesion, the rubber–lime composite specimens (with 7% and 9% lime) exhibit outstanding performance. The specimen with 9% lime and 4% rubber reaches a cohesion of 64.99 kPa, which is 4.5 times that of the rubber-alone specimen (14.48 kPa) and nearly three times higher than that of the undisturbed loess (21.76 kPa). Even when the rubber content increases to 10%, the cohesion of the 9% lime-modified loess specimen remains at 60.10 kPa, far exceeding that of other modification methods. By comparison, the cohesion of rubber-alone specimens increases only from 14.48 kPa to 23.15 kPa, remaining below that of the undisturbed loess. The rubber–EICP composite specimens exhibit slightly higher cohesion (16.87–26.12 kPa), but the values are still significantly lower than those of the lime-modified specimens [34].

The variation trend of the internal friction angle differs among the modification methods. It increases from 11.85° (4% rubber) to 24.25° (10% rubber) for the rubber–EICP composite specimens, reaching an increment of 104%. By contrast, the internal friction angle of the lime-modified specimens slightly decreases from 25.08° (9% lime with 4% rubber) to 24.68° (10% rubber), indicating that EICP provides a more pronounced improvement in frictional performance at higher rubber contents [34,36,37]. The observed differences arise from the distinct mechanisms of modification. Rubber-alone modification increases the internal friction angle by enhancing particle-to-particle friction; however, its loose structure cannot form an effective cementation network, resulting in low cohesion. EICP technology improves particle interlocking through microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation, significantly enhancing the internal friction angle, but the cementation strength is limited by mineralization efficiency, leading to modest cohesion improvement. Lime modification, however, primarily relies on cementation; that is, lime reacts with soil particles to form hydration products, generating a rigid skeleton and markedly increasing cohesion. Excessive rubber incorporation displaces part of the soil particles, weakening the continuity of the cementation network and slightly reducing cohesion. The increase in the internal friction angle for lime-modified specimens is moderate, possibly due to the increased brittleness of the solidified soil and restricted particle rearrangement. By contrast, the synergistic effect of lime and rubber under high-pressure conditions is more effective. Specifically, the lime skeleton provides rigid support, while the elastic deformation of rubber particles absorbs energy and enhances friction, resulting in a balanced improvement of both cohesion and internal friction angle. Although EICP technology significantly improves the internal friction angle at high rubber contents (e.g., 10% rubber, 24.25°), its cohesion (26.12 kPa) is only 42% of that of the lime-modified specimens, indicating limitations in overall performance. Therefore, the rubber–lime composite exhibits an irreplaceable advantage in comprehensive shear performance, whereas EICP is more suitable for scenarios requiring high frictional performance with relatively low cementation demand.

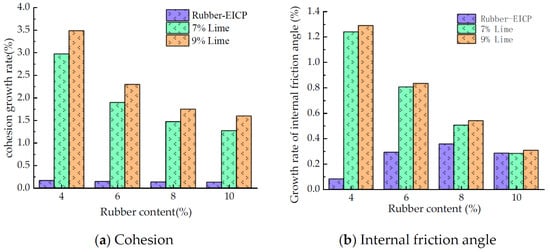

4.3. Comparison of Differences in the Growth Rates of Cohesion and Internal Friction Angle

Although the shear performance of rubber-modified loess is significantly improved compared with that of the undisturbed loess, there remains a marked difference relative to the other three modification techniques. Therefore, in the following analysis, the rubber-alone modification is taken as the baseline, and the growth rate of cohesion and the growth rate of internal friction angle are defined, as shown in Equations (1) and (2), respectively:

where C is the growth rate of cohesion of the specimen; ca refers to the cohesion of the loess modified with rubber alone; cb represents the cohesion of the other three types of modified loess specimens; Ψ is the growth rate of the internal friction angle of the specimen; φa is the internal friction angle of the loess modified with rubber alone; and φb represents the internal friction angle of the other three types of modified loess specimens.

The differences in the enhancement of shear performance among the three soil modification methods are shown in Figure 9. Taking the rubber-alone modification as the baseline, the cohesive strength growth rate of the lime-modified soil with a 9% lime content reaches 348.83% at a 4% rubber dosage, which is much higher than that of the EICP technique (16.51%) and the 7% lime group (297.41%). As the rubber content increases to 10%, the 9% lime group still maintains a growth rate of 159.62%, whereas that of the EICP group decreases to 12.83%, indicating that lime modification exhibits stronger stability in cementation enhancement under varying dosage conditions [34].

Figure 9.

Comparison of cohesion and internal friction angle growth rates.

In contrast, the variation trend of the internal friction angle growth rate is markedly different. The rubber–EICP composite specimens perform better at higher rubber contents, reaching 35.74% at an 8% rubber dosage, which is lower than the increments observed in the 7% lime group (50.56%) and 9% lime group (54.12%). However, with a further increase to 10% rubber dosage, the growth rate of EICP decreases to 28.58%, while that of the lime-modified soil tends to remain stable at approximately 30% [34].

The high cohesive strength growth rate of the lime-modified soil originates from its strong cementation reaction. Lime reacts with soil particles to form hydrated compounds, constructing a dense and rigid skeletal structure that significantly enhances interparticle bonding. At a lime content of 9% and a low rubber dosage (4%), the cemented network remains almost intact, leading to nearly a 3.5-fold increase in cohesion. However, as the rubber dosage increases, the replacement of soil particles by rubber partially disrupts the cementation continuity, thereby causing a gradual decline in the growth rate.

The EICP technique, on the other hand, provides only limited improvement in cohesion because it relies on microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation (MICP) to fill soil pores. The cementation strength is restricted by mineralization efficiency, making it difficult to form a continuous rigid framework. Nevertheless, EICP exhibits a distinct advantage in improving the internal friction angle, as the calcium carbonate precipitates enhance particle interlocking and increase the roughness at the soil–rubber interface, thus markedly improving frictional resistance (particularly at rubber dosages between 6% and 8%).

The moderate increase in the internal friction angle of the lime-modified soil is attributed to the limited particle rearrangement caused by the rigid skeletal framework and the increased brittleness of the solidified structure, which weakens the energy dissipation mechanism through friction. Overall, the rubber–lime composite modification achieves an optimal balance between cohesion and internal friction angle through the synergistic effects of cementation enhancement and elastic buffering, whereas the EICP technique is more suitable for conditions emphasizing frictional performance with low cementation demand, such as surface slope reinforcement, thereby demonstrating unique application advantages.

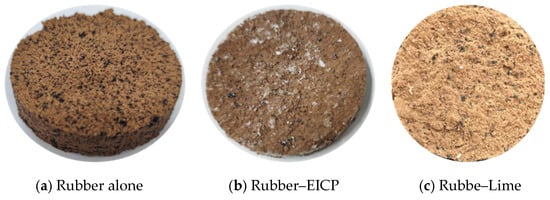

4.4. Comparison of Differences in Damage Modes

To further investigate the shear failure patterns of the modified loess, a comparative analysis is conducted on the failure morphologies of specimens modified by rubber alone, rubber–EICP technology, and rubber–lime. This analysis aims to elucidate the influence of different modification mechanisms on the deformation and fracture characteristics during the shear process.

As shown in Figure 10a, the specimen modified with rubber alone exhibits a rough and loosely layered shear surface, with numerous traces of detached rubber particles visible on the failure plane. A distinct particle-sliding zone is observed along the shear edge, indicating that the failure is predominantly governed by frictional sliding.

Figure 10.

Failure patterns of modified loess specimens.

In contrast, Figure 10b shows that the rubber–EICP composite specimen presents a relatively smoother surface, partially covered by white calcium carbonate precipitates. Discontinuous cemented fracture zones appear along the shear plane, accompanied by radial micro-cracks at the edges, suggesting progressive failure of the cemented regions during shearing.

As illustrated in Figure 10c, the rubber–lime composite specimen exhibits the most compact and integrated structure. The shear surface displays step-like multi-level fractures, with dense secondary cracks surrounding the main crack. The lime-cemented zones exhibit shell-like fracture surfaces, and the rubber particles are tightly bonded to the soil matrix, showing only localized elastic rebound marks under high vertical normal stress (e.g., 300 kPa).

The observed differences in failure morphology arise from the synergistic effects of internal modification mechanisms. In the soil specimen with rubber alone, the absence of effective cementation causes interparticle contacts to rely mainly on frictional interlocking, leading to loose and brittle failure as sliding occurs along particle interfaces. The EICP-modified specimen enhances local bonding through calcium carbonate precipitation, but the discontinuous cementation network results in preferential cracking along weakly bonded zones.

In contrast, the rubber–lime composite benefits from the strong cementation reaction of lime, forming a rigid skeleton, while the elastic deformability of rubber particles dissipates shear energy. The rigid framework resists the initial shear load and induces step-shaped primary cracks, whereas rubber elasticity delays the propagation of secondary cracks, leading to the formation of a multi-level fracture system with superior energy absorption capacity.

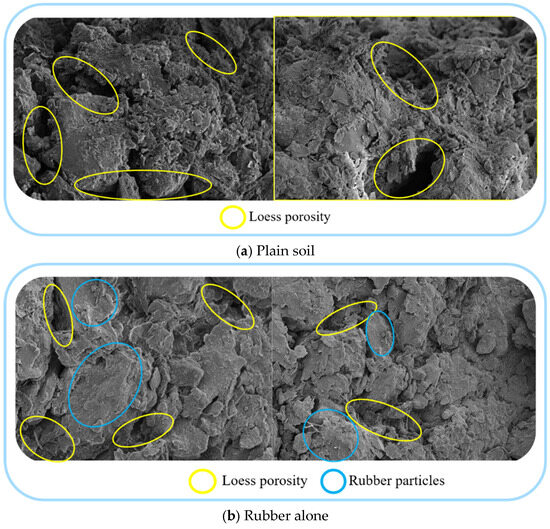

4.5. Comparison of Differences in Cementation Mechanisms

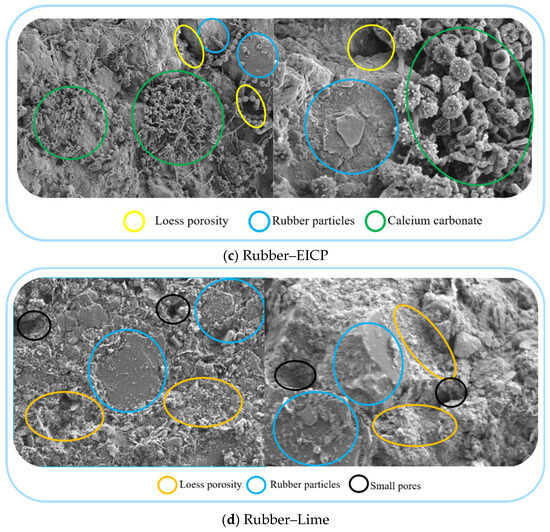

To further validate the analysis of the failure mechanisms for rubber-modified, rubber–EICP, and rubber–lime-treated loess, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) tests are conducted on specimens of undisturbed loess, rubber-modified loess, rubber–EICP composites, and rubber–lime composite loess. The microstructural morphology of each specimen is examined to observe microscopic variations within the soil matrix, and the results are used to cross-verify the mechanistic interpretations proposed in the preceding sections. For each treatment condition, SEM observations are performed on multiple representative fields across at least three specimens, and the presented images are selected as representative microstructures that are consistent with the observed macroscopic mechanical behavior.

As shown in Figure 11a, the undisturbed loess specimen exhibits a loose microstructure, in which soil particles are irregularly stacked with predominantly point contacts. The porosity is relatively high and randomly distributed, and partial separation of clay mineral lamellae can be observed in localized regions.

Figure 11.

Microstructural images of specimens under different treatment conditions.

In Figure 11b, the SEM image of the rubber-alone specimen reveals that rubber particles are discretely embedded within the soil matrix, forming only localized frictional contacts with surrounding particles. Scratches and abrasion marks are visible on the rubber surfaces, while distinct voids appear along the soil–rubber interfaces, indicating weak interfacial bonding between the two phases.

As illustrated in Figure 11c, the rubber–EICP composite specimen shows a large number of coral-like or spherical calcium carbonate crystals adhered to the soil particle surfaces. A triphasic “soil–CaCO3–rubber” interlocking structure is observed in certain regions; however, the cementation layer thickness is non-uniform, and some unfilled pore channels remain within the matrix.

In contrast, Figure 11d demonstrates that the rubber–lime composite specimen exhibits a dense and continuous cementation network, where soil particles are encapsulated by calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) gel, forming a rigid interconnected skeleton. The rubber particles are tightly anchored within the cementitious matrix, and no visible interfacial cracks are detected. Only a few micron-scale voids are observed in high-stress zones, which are likely induced by the elastic rebound of rubber particles under compression.

The undisturbed loess lacks cementation, and particle interactions rely solely on van der Waals forces and mechanical interlocking. During shear, particles are prone to slip and pore collapse, resulting in low-strength failure. In the rubber-alone specimens, the inclusion of rubber particles enhances shear strength through frictional effects. However, the discrete rubber particles fail to form effective stress transmission pathways, and the presence of microscopic voids concentrates shear energy at localized contact points, triggering particle detachment and progressive failure. In the rubber–EICP composite specimens, the calcium carbonate precipitates partially fill voids and enhance particle interlocking. Nevertheless, crystal growth is constrained by microbial activity and environmental conditions, forming a discontinuous cementation network. Under shear, failure preferentially occurs along the weakly cemented zones, consistent with the intermittent fracture bands observed macroscopically. For the rubber–lime composite specimens, the C–S–H gel cementation constructs a rigid skeleton, while the elastic modulus contrast of rubber particles promotes uniform shear stress distribution. The cemented network resists the initial shear, forming primary cracks, whereas the elastic rebound of rubber particles absorbs energy and guides the propagation and branching of secondary cracks. The presence of microscopic voids further delays crack penetration, achieving a synergistic optimization of strength and ductility. This “rigid skeleton–elastic buffering” composite structure provides microscopic validation for the absence of brittle failure under high vertical normal stress observed in the shear stress–strain curves.

4.6. Comprehensive Performance Analysis

Comprehensive performance evaluation indicates that single-material modifications using either rubber particles or lime exhibit certain advantages in terms of initial cost and construction convenience. However, their intrinsic limitations lie in singular performance characteristics and limited sustainability. The rubber-alone modification lacks effective cementation, resulting in moderate improvement in shear strength, and is prone to progressive failure over time due to particle dispersion. In contrast, the lime-alone modification forms a rigid skeleton through solidification reactions, enhancing strength; however, over-hardening may induce brittle fractures, and alkaline leachate can adversely affect the surrounding environment. Compared with these single-material approaches, the rubber–lime composite modification demonstrates a more balanced and comprehensive performance. The strong cementation effect of lime establishes a stable rigid skeleton, significantly enhancing shear strength and overall load-bearing capacity, while the elastic buffering of rubber particles effectively absorbs shear energy and delays crack propagation. The synergistic interaction of these two mechanisms ensures structural stability under high vertical normal stress and facilitates easy mix ratio control during construction, making this composite strategy a preferred solution for high-demand engineering applications.

The EICP technique, owing to its environmental compatibility and low-carbon characteristics, provides an alternative and potentially sustainable approach for soil improvement. Enzyme-induced calcium carbonate precipitation forms a mineralized bonding network within soil pores without reliance on microbial metabolism, thereby reducing biological sensitivity and enhancing construction controllability. Although EICP-treated soils exhibit improved frictional resistance and durability, their cementation efficiency is constrained by carbonate precipitation continuity and reaction conditions, resulting in relatively limited cohesion development compared with lime-stabilized systems. Consequently, EICP-based modification appears more suitable for applications emphasizing frictional enhancement and environmental compatibility rather than high load-bearing demand.

5. Conclusions

The shear mechanical behavior of loess modified with rubber particles combined with lime and enzyme-induced calcium carbonate precipitation (EICP) is systematically investigated, with particular emphasis placed on distinguishing the contributions of cohesion and internal friction angle under identical stress paths. Based on the experimental results, microstructural observations, and comparative analyses, the following conclusions are drawn:

- (1)

- Regarding the first objective, which aims to clarify the shear mechanical behavior of rubber–lime-modified loess under varying material proportions and stress conditions, the results demonstrate that rubber–lime composite modification significantly enhances shear strength compared with rubber-only and lime-only treatments. Under medium to high normal stresses (≥100 kPa), the combined system exhibits stable shear resistance and improved deformation capacity. Optimal performance is achieved when the rubber content ranges from 6% to 8% and the lime content ranges from 7% to 9%, at which a balance between strength enhancement and material efficiency is obtained.

- (2)

- Regarding the second objective, which focuses on quantitatively distinguishing the contributions of cohesion and internal friction angle among different modification strategies, it is found that lime-induced cementation predominantly contributes to cohesion enhancement, whereas rubber particles mainly improve shear resistance through frictional interaction and elastic stress redistribution. Rubber–EICP modification primarily increases the internal friction angle by enhancing interparticle interlocking, but its contribution to cohesion remains limited due to the discontinuous nature of calcium carbonate bonding. In contrast, the rubber–lime system exhibits a complementary enhancement mechanism, in which significant cohesion improvement is accompanied by a moderate but stable increase in internal friction angle.

- (3)

- Regarding the third objective, which aims to elucidate the synergistic and contrasting reinforcement mechanisms associated with chemical cementation, biomineralization, and rubber-induced physical buffering, microstructural observations confirm that rubber–lime-modified loess forms a dense and continuous cemented skeleton dominated by hydration products, with rubber particles firmly embedded within the matrix. This “rigid skeleton–elastic buffering” structure effectively redistributes shear stress and delays crack propagation, explaining the superior shear performance and ductility observed under high normal stress conditions. In comparison, rubber–EICP-treated loess exhibits localized and discontinuous mineralized bonding, which favors frictional enhancement but limits cohesive strength development.

From an engineering perspective, the results indicate that rubber–lime composite modification is particularly suitable for applications requiring high shear strength and deformation tolerance under medium to high stress levels, such as foundation reinforcement and load-bearing soil layers. Rubber–EICP modification, while exhibiting lower cohesion, offers advantages in terms of environmental compatibility and frictional enhancement, making it more appropriate for low-stress or environmentally sensitive applications such as surface stabilization and slope protection.

It should be noted that the present study is based on short-term laboratory curing conditions and does not explicitly address long-term durability, cyclic loading behavior, or field-scale performance. Future research should therefore focus on evaluating the long-term mechanical stability of rubber–lime and rubber–EICP systems under wetting–drying cycles, freeze–thaw conditions, and repeated loading, as well as validating the proposed mechanisms through large-scale or in situ tests.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, and formal analysis, Z.X., X.L. and S.C. Writing—review and editing, Z.X., X.L., T.X. and S.C. Supervision, Z.X., Y.Z. and S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Shaanxi Province Key Research and Development Plan Project (No. 2025SF-YBXM-525, No. 2025SF-YBXM-539) and the Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province (No. 2025JC-YBMS-535).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included in the article.

Acknowledgments

We fully appreciate the editors and all anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Zongxi Xie was employed by the company State Grid Hubei Electric Power Company Limited. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Xu, Z.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, M. Loess in China and loess landslides. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2007, 26, 1297–1312. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Q. Distribution characteristics and macroscopic influencing factors of seismic loess landslides in northwest China. Meteorol. Disaster Reduct. Res. 2007, 30, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Shi, Y. Basic characteristics of seismic landslides in loess area of northwest China. J. Seismol. Res. 2006, 29, 276–280+318. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson, I.; Evstatiev, D.; Karastanev, D. The treatment of collapsible loess soils using cement materials. In GeoCongress 2008: Geosustainability and Geohazard Mitigation; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2008; pp. 662–669. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Feng, Z. Experimental study on the engineering characteristics of cement-improved loess. Subgrade Eng. 2006, 02, 57–59. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, L.; Li, C.X.; Guo, J. Mechanical properties of lime-fly ash-sulphate aluminum cement stabilized loess. J. Renew. Mater. 2020, 8, 1357–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Liang, S.; Zhang, F.; Wu, W.T.; Yan, X.D. Experimental study on engineering performances of lime-stabilized loess. Railw. Eng. 2014, 9, 105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Yu, W.; Fan, L.; Fu, L.; Hu, R.; Lin, D.; Wang, Y. Experimental research on strength characteristics and engineering treatment of improved leoss soil. J. Eng. Geol. 2011, 19, 116–121. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, M.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, D. Experiment study on the strength and microstructure of bentonite-lime improved loess. Hydro-Sci. Eng. 2022, 5, 86–93. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, T.; Zhang, B.; Tian, Z.; Lu, D.H. Study on engineering characteristic of lime-flyash loess. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2004, 26, 719–721. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Yao, Y.; Zhou, H. Experimental study of shear strength and permeability of improved loess with long age. Rock Soil Mech. 2017, 38, 170–176. [Google Scholar]

- Almuaythir, S.; Zaini, M.S.I.; Hasan, M. Mechanistic and Comparative Assessment of Lime Stabilization and Multi-Pathway Soil Reinforcement Techniques. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 30041. [Google Scholar]

- Whiffin, V.S. Microbial CaCO3 Precipitation for the Production of Biocement. Ph.D. Thesis, Murdoch University, Perth, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Qabany, A.A.; Soga, K. Effect of chemical treatment used in MICP on engineering properties of cemented soils. In Bio- and Chemo-Mechanical Processes in Geotechnical Engineering: Géotechnique Symposium in Print 2013; ICE Publishing: London, UK, 2014; pp. 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Kavazanjian, E.; Hamdan, N. Enzyme induced carbonate precipitation (EICP) columns for ground improvement. In IFCEE 2015; American Society of Civil Engineers—ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2015; pp. 2252–2261. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Ye, W.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Y.G. Advances in soil cementation by biologically induced calcium carbonate precipitation. Rock Soil Mech. 2022, 43, 345–357. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Zhao, H. Effect of Rubber Particle Size and Content on the Mechanical Properties of Rubber–Clay Mixtures Solidified by Enzyme-Induced Calcium Carbonate Precipitation. Materials 2025, 18, 3429. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, H.; Shu, S.; Gao, Y.F.; Yan, B.; He, J. Multiple-phase enzyme-induced carbonate precipitation (EICP) method for soil improvement. Eng. Geol. 2021, 294, 106374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, H.X.; Cheng, X.H. Role of calcium sources in the strength and microstructure of microbial mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 77, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Gao, Y.F.; Gu, Z.X.; Chu, J.; Wang, L. Characterization of crude bacterial urease for CaCO3 precipitation and cementation of silty sand. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2020, 32, 04020071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, D.; Yasuhara, H.; Kinoshita, N.; Unno, T. Applicability of enzymatic calcium carbonate precipitation as a soil-strengthening technique. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2013, 139, 2201–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almajed, A.; Tirkolaei, H.K.; Kavazanjian, E., Jr.; Hamdan, N. Enzyme induced biocementated sand with high strength at low carbonate content. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P.; Zhu, L.; Zhong, X.; Dong, L.F.; Chen, W.W. Experimental investigation on the dynamic characteristics of earthen site soil treated by enzyme-induced calcium carbonate precipitation. Rock Soil Mech. 2022, 43, 3385–3392+3415. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wu, G.; Dai, Y.; Huang, C.; Chang, S. Research on optimization of EICP-PVA solidified silty sand based on response surface method. Highway 2023, 68, 264–272. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Cui, Y.; Wang, Q. 17 years of rapid development and prospects for China’s waste tire recycling industry. China Resour. Compr. Util. 2023, 41, 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Edil, T.B.; Bosscher, P.J. Engineering properties of tire chips and soil mixtures. Geotech. Test. J. 1994, 17, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Salgado, R.; Bernal, A.; Lovell, C.W. Shredded tires and rubber-sand as lightweight backfill. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 1999, 125, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Bai, J.; Kou, W.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y. Compaction and Dynamic Properties of Loess Enhanced by Waste Tire Rubber Particles. J. Vibroeng. 2025, 27, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, A.; Feng, J. Effect of scrap tire bead addition on shear behavior of sand. J. Army Eng. Univ. PLA 2009, 10, 483–487. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. Geotechnical Properties of Granulated Rubber and Loess Soil Mixtures. Ph.D. Thesis, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sherbiny, R.; Youssef, A.; Lotfy, H. Triaxial testing on saturated mixtures of sand and granulated rubber. In Geo-Congress 2013: Stability and Performance of Slopes and Embankments III; American Society of Civil Engineers—ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2013; pp. 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Tong, H.; Qiu, R.; Yuan, J. Research on mechanical properties of rubber-particle-improved soil cemented by micp. Ind. Constr. 2020, 50, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Qian, S.; Wang, X.; Bian, H.; Han, Z.; Shi, L. Experimental study on resistance of EICP and lignin joint-modified silt slope to rain erosion. J. Hohai Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2024, 52, 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Chai, S.Q.; Cai, D.B.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Liu, J. Experimental study on shear mechanical properties of improved loess based on rubber particle incorporation and EICP technology. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1270102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mahbashi, A.M.; Hassan, A.; Al-Shaibani, A. Enhancing Clayey Soil Performance with Lime and Waste Rubber Tyre Powder: Mechanical and Microstructural Insights. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 395, 132368. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, S.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Quan, D.; Fan, Z. Experimental study on dynamic properties of loess improved by rubber particles and EICP technology. Adv. Eng. Sci. 2024, 56, 134–146. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, S.; Liu, J.; Quan, D.; Fang, K.; Fang, Z.; Li, X. Study on the influence of rubber particle EICP modified soil damping layer on the damping performance of frame structure. Build. Sci. 2025, 41, 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 50123-2019; Soil Test Methods Standard (Standard for Geotechnical Testing Method). China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.