Abstract

The use of vibrational transport for granular materials has significantly increased in the technological industry due to its reliability, operational efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and relatively uncomplicated technological setup. These transportation methods typically utilize various forms of asymmetry, such as kinematic, temporal (time), wave, and power asymmetry, to induce controlled motion on oscillating surfaces. This study analyses the motion of the granular materials on an inclined plane, where the central innovation lies in the creation of an additional system asymmetry of frictional conditions that enables the granular materials to move upward. This asymmetry is created by introducing dry friction dynamic manipulations. A mathematical model has been developed to describe the motion of particles under these conditions. The modelling results proved that in an inclined transportation system, the asymmetry of frictional conditions during the oscillation cycle—created through dynamic dry friction manipulations—generates a net frictional force exceeding the gravitational force, thereby enabling the upward movement of granular particles. Additionally, the findings highlighted the key control parameters governing the motion of granular particles. λ, which represents the segment of the sinusoidal period over which the friction is dynamically louvered, serves as a parameter that controls the velocity of a moving particle on an inclined surface. The phase shift ϕ serves as a parameter that controls the direction of the particle’s motion at various inclination angles. Experimental investigations were conducted to assess the practicality of this method. The experimental results confirmed that the granular particles can be transported upward along the inclined surface with an inclination angle of up to 6 degrees, as well as provided both qualitative and quantitative validation of the model by illustrating that motion parameters exhibit comparable responses to the control parameters, and strongly agree with the theoretical findings. The primary advantage of the proposed vibrational transport method is the capacity for precise control of both the direction and velocity of granular particle transport using relatively simple mechanical setups. This method offers mechanical simplicity, low cost, and high reliability. It is well-suited to assembly line and manufacturing environments, as well as to industries involved in the processing and handling of granular materials, where controlled transport, repositioning, or recirculation of granular materials or small discrete components is required.

1. Introduction

Transport of granular materials can be achieved using various approaches. For transportation, the objects and granular particles are usually subjected to unilateral constraints, where they do not require an external force directly applied to them to move, such as gripping, squeezing, or picking up [1,2,3,4]. While commonly used solutions with conventional vibrating, stirring, shaking or knocking techniques operate well with coarser powders, they are limited with fine powders. Different cohesive and adhesive behaviors of materials can lead to agglomeration and adhesion to surfaces, making the transportation of granular particles challenging. Vibrational transport applications are used in various fields and technological industries such as biotechnology, cell biology, materials processing, and semiconductors [5,6,7,8,9].

To effectively carry out vibrational transport tasks, asymmetry is a crucial factor in enabling the movement of an object on the surface of the vibrational plane. When asymmetry is present, the net friction force over a complete vibration cycle is not neutralized, which facilitates the motion of the object. Vibrational transport methods typically leverage different forms of asymmetry, such as temporal, spatial, power (force), kinematic, or wave asymmetry, to induce movement.

Temporal asymmetry, also referred to as time asymmetry, is induced when the forward and backward speeds are different, with the forward motion experiencing longer than the motion backwards. The nature of motion of objects on a vibrating surface subjected to oscillations, where the forward velocity did not match the backward velocity in each cycle, generating the necessary temporal asymmetry for movement was studied by Reznik et al. [10]. Similarly, Mayyas [11,12] investigated the stick-slip behavior of an object on an oscillating plane, where temporal (time) asymmetry was used to force the object’s movement. Viswarupachari et al. [13] examined particle motion on a rigid surface subjected to asymmetric vibrations, resulting in temporal asymmetry. Hunnekens et al. [14] have shown that temporal asymmetry can be achieved by designing an appropriate periodic motion profile for a vibrating surface to enable object transport.

Based on the theory of vibrational transportation, power asymmetry occurs when the transportation system has an inclination angle or when a constant force acts on the objects being moved. Another form of asymmetry is kinematic asymmetry, which is created by asymmetric vibration paths or the law of motion along these paths. In practice, these two types of asymmetries can also be combined. Baksys and Puodziuniene [15,16] demonstrated the motion characteristics of a compliant body on an inclined plane under conditions where various forms of asymmetry, such as power asymmetry and kinematic asymmetry, are simultaneously applied.

Higashimori et al. [17] proposed an innovative method for omnidirectional nonprehensile manipulation utilizing a single actuator. The proposed system consisted of a manipulator with a plate end-effector connected through an underactuated joint mechanism comprising an active joint controlled by an actuator and a viscoelastic passive joint. Notably, the axes of these joints are arranged non-parallel, enabling the plate’s vibrational orbit to change based on the frequency and offset angle of the actuator’s input. Adachi et al. [18] introduced a unique setup for a granular vibration pumping system where an eccentric cam mechanism vibrates a tube in a certain way to lift granular materials. Frei et al. [19] presented the friction forces enabling objects to be transported along a planar horizontal surface with around two degrees of freedom to get a kinematic asymmetry using the horizontal and vertical vibrations. Vrublevskyi [20] investigated vibrational motion, which was achieved through kinematic asymmetry, where the sloped surface underwent harmonic oscillations and polyharmonic oscillations in the axial and perpendicular directions. The kinematic asymmetry type is widely used in industrial vibrational transportation applications [21,22,23,24].

A further type of asymmetry is wave asymmetry, which is induced by traveling waves and can be applied to achieve the motion of granular particles [25,26,27,28,29]. Approaches utilizing various multifrequency vibrations are also applied to transport granular materials. Hui et al. [30] presented a novel method for transporting dry granular materials utilizing various frequencies by an audio system. The research has shown that the velocity and direction of the granular flow can be controlled by modulating the sign and amplitude of the waveform. Dunst et al. [31] studied and observed the vibrational handling of fine powders, showing how mechanical waves generated by piezoelectric actuators achieved powder movement under a combination of low and high frequency excitations.

A new method utilizing the approach of controlled dry friction for bidirectional and omnidirectional transportation on a vibrating horizontal platform with controlled dry friction has been proposed. Research has shown that omnidirectional motion can be implemented by achieving asymmetry through controlled friction between the moving object and the transport surface [32]. A newly proposed bidirectional vibrational transportation method using a horizontally oscillating platform, where dynamic dry friction is controlled through periodic high-frequency vibrations between the surface and the object [33].

In summary, previous studies on asymmetries in frictional conditions have mainly focused on direction-dependent surface friction properties, horizontal surfaces, or larger-scale objects, where gravity plays a more significant role. This study presents a vibrational transportation method for granular materials that utilizes sinusoidal oscillation cycles and dry friction dynamic manipulations to create an additional asymmetry in an inclined transportation system. The goals of this study are twofold: to develop a mathematical model to investigate the feasibility of upward motion of particles and to identify the relevant control parameters, and to conduct an experimental investigation to assess the practicality of the proposed method.

2. Methodology

2.1. Mathematical Model

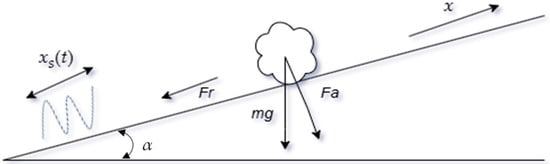

Figure 1 demonstrates the dynamic model of the granular particle on an inclined plane with the forces exerted on it.

Figure 1.

A dynamic model describing the transport of granular particles on an inclined surface undergoing longitudinal oscillations.

Consider a granular particle placed on an inclined surface that oscillates longitudinally with displacement (t). The equation of motion is influenced by:

- Gravity:

- Normal force:

- Friction force:

- Oscillatory motion:

Here m is the particle mass, g is the gravity, α describes the slope of the inclined surface, and μ(ωt) is the function of the dry friction coefficient that is synchronized with the function of the platform’s longitudinal harmonic motion. The normal force between the surface and the granular particle consists of a portion of the total weight force. In this model, the adhesion force, and the cohesion force are considered negligible due to the physical characteristics of the material and controlled experimental conditions. Granular table salt typically consists of medium to coarse grains (250–500 μm) with relatively smooth, cubic surfaces that exhibit minimal van der Waals or electrostatic interactions under dry conditions. Furthermore, the experiments and modeling are conducted in a low-humidity environment, which prevents the formation of moisture-induced capillary bridges that would otherwise enhance cohesive behavior.

Equation (1) represents Newton’s second law of motion, which describes the motion of the granular particle on an inclined surface in a longitudinal direction (x-axis):

Thus, the equation can be written as follows:

Dividing by m:

Non-dimensional analysis was employed to identify the characteristic of the control parameter as illustrated in Equation (4):

The following non-dimensional equation can describe the directional motion of the granular particles on the inclined surface:

The non-dimensional average velocity is demonstrated in Equation (6):

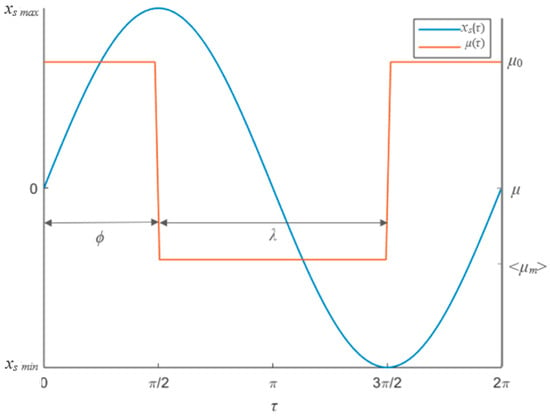

Figure 2 represents the functions driving the dry friction coefficient and the sinusoidal harmonic oscillations.

Figure 2.

Functions driving the dry friction coefficient and the sinusoidal harmonic oscillations.

The following equation describes the function representing the dry friction behavior corresponding to the inclined platform oscillating in a longitudinal direction.

where ϕ is the phase shift between the sinusoidal oscillations and the function governing the dry friction coefficient, λ represents the segment of the sinusoidal period over which the friction is dynamically lowered, ⟨μm⟩, is the lowered value of the friction coefficient.

The dry friction can be adjusted in practical applications by introducing high-frequency vibrations between the object and the contacting surface. Consequently, under the influence of vibrations, the time-averaged effective dry friction force between the granular particles and the transportation surface can be significantly reduced.

2.2. Methodology of Experiments

Experimental research was conducted to assess the technical characteristics of the proposed method. Granular particles were moved upward on a harmonically oscillating inclined plane by dynamically manipulating dry friction. Granular salt was chosen as the experimental material due to its well-characterized and consistent physical properties, which make it ideal for studying vibrational transport phenomena. Commercial table salt typically has a particle size range between 250 and 500 μm, offering an adequate scale for observing dynamic behaviors while minimizing cohesion and adhesion effects under dry conditions. Its bulk density, approximately 2.16 g/cm3, is high enough to produce significant inertial effects when subjected to vibrational forcing, thereby enhancing motion sensitivity to frictional modulation. The model was simplified by neglecting adhesive forces, as the salt was transported under controlled humidity conditions. Additionally, salt is widely available, inexpensive, chemically stable, and non-toxic.

Particle size significantly impacts the vibrational transport of granular materials by influencing their dynamic response, frictional behavior, and energy absorption characteristics. Moreover, the particle size substantially influences the surface contact mechanics, where larger particles generate greater normal forces, leading to higher friction, which affects the efficiency of friction-asymmetry-based transport mechanisms. For granular salt in the size range of 250–500 µm and density approximately 2.16 g/cm3, the particles are well suited to such vibrational systems with moderate frequency and amplitude. These parameters, combined with tailored frictional asymmetry, enable effective uphill or bidirectional transport, as shown in this study.

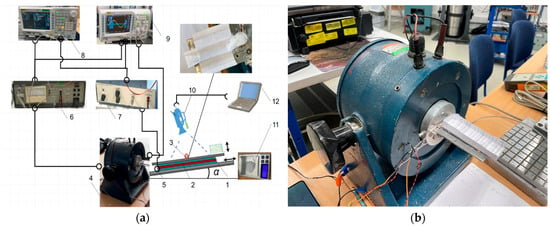

The schematic diagram in Figure 3a shows the experimental test bench for transporting granular particles on an inclined surface undergoing oscillations in the longitudinal direction. Figure 3b presents an overall view of the test bench. It includes an inclined platform (1) with a transportation surface (2), and a piezoelectric actuator (3) installed beneath the surface. The granular particles were placed on the surface of the inclined plane. The roughness of the transportation surface is about Ra 0.4 μm, which provides a balance between limiting unwanted adhesive forces and enhancing controllable frictional behavior, making it ideal for studying and optimizing vibrational transport of dry granular materials like salt. High-frequency vibrations of 5820 Hz were periodically excited by the piezoelectric actuator to manipulate frictional behavior between the particles and the transportation surface. The duty cycle controlling pulses of these vibrations was synchronized with signal of the sinusoidal signal (Figure 2). A waveform generator (DG4202, RIGOL, Beijing, China) (8) was used to generate the signals. The sinusoidal signal was amplified by a power amplifier (LV-103, Metra Mess- und Frequenztechnik in Radebeul, Radebeul, Germany) (6) and fed to an electrodynamic vibrator (ESE 211, VEB Robotron-Meßelektronik, Dresden, Germany) (4). The electrodynamic vibrator was driving the inclined platform in the longitudinal direction. The oscillations of the platform were registered by a vibration sensor (5). A piezo linear amplifier (EPA-104, Piezo Systems Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA) (7) was used to amplify the signals applied to the piezoelectric actuator. The signals were monitored by a digital oscilloscope (DS1054, RIGOL) (9). The transportation of the granular salt was captured using a Phantom v711 camera (Vision Research, Wayne, NJ, USA) camera (10). Video recordings with a resolution of 1280 × 800 pixels at 60 frames per second were analyzed using PCC 3.8 software. For a known particle displacement, the elapsed time was determined from frame counts, and the average velocity was calculated accordingly. The quantity of the transported granular salt was measured by micro-weight scaling of capacity 0.01–100 g (AWS, Beijing, China) (11) and a PC (12).

Figure 3.

Experimental setup for granular particles transportation: (a) principle diagram: (1), transportation surface; (2), piezoelectric actuator; (3), granular particle; (4), electrodynamic shaker; (5), vibration sensor; (6), power amplifier; (7), piezo linear amplifier; (8), waveform generator; (9), digital oscilloscope; (10), camera; (11), micro weighing scale; (12), PC; (b) overall view of the experimental setup.

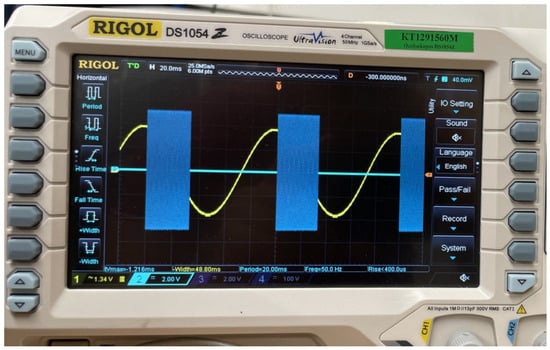

An oscillogram of the piezoelectric actuator and sinusoidal signals is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Oscilloscope presenting the piezoelectric and sinusoidal signals.

3. Results

3.1. Results of Modelling

The process of transportation on an inclined plane was investigated numerically by solving Equation (5) using MATLAB (Release R2023a), employing the Runge–Kutta ordinary differential equation solver, ODE45. To ensure numerical stability of the solution, the maximum integration time step was set to 10−4 s. The solver’s absolute and relative tolerances were set to 10−6. These settings produced stable and reliable results for the problem under investigation within a reasonable computation time.

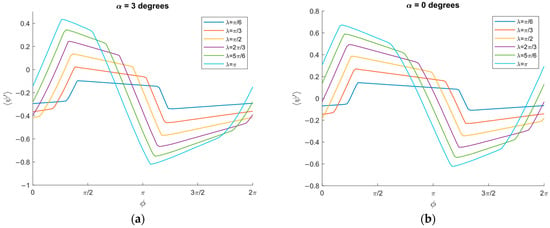

Figure 5 demonstrates how the non-dimensional average velocity varies with respect to the phase shift ϕ across different inclinations. At an inclination angle of α = 0 degrees, the non-dimensional average velocity increased significantly in a range from ϕ = 0 to ϕ = π/2, reaching its peak at ϕ = π before gradually decreasing in a range from ϕ = π/2 to ϕ = 3π/2 (Figure 5a). When the inclination angle increased to α = 3 degrees, the average velocity noticeably decreased in a range from ϕ = π/2 to ϕ = π, under μ0 = 0.3 and ⟨μm⟩/μ0 = 3/10 (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Non-dimensional average velocity of the granular particles vs. the phase shift ϕ: (a) α = 0 degrees, γ = 1, μ0 = 0.3, ⟨μm⟩/μ0 = 3/10; (b) α = 3 degrees, γ = 1, μ0 = 0.3, ⟨μm⟩/μ0 = 3/10.

These results show that ϕ serves as a parameter that controls the direction of the particle’s motion, as this parameter determines the phase shift that sets the asymmetry of the frictional conditions and, as a result, the orientation of the net force vector.

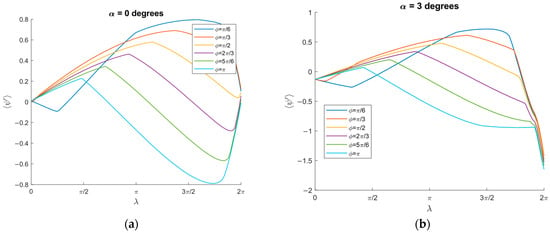

At α = 0, the average velocity gradually increased, reaching a maximum in a range from π to 2π/3 at ϕ = π/4. However, beyond λ = 2π, the average velocity of the granular particles decreased, causing the particles to move downward in the opposite direction, as shown in Figure 6a.

Figure 6.

Non-dimensional average velocity vs. λ: (a) α = 0 degree, γ = 1, μ0 = 0.3, ⟨μm⟩/μ0 = 3/10; (b) α = 3 degrees, γ = 1, μ0 = 0.3, ⟨μm⟩/μ0 = 3/10.

For α = 3 degrees, the average velocity experienced a slight increase, reaching its peak in a range from λ = π to λ = 3π/2, before noticeably decreasing at λ = 2π. At this point, the granular particle reversed, moving backward in a negative direction (Figure 6b).

These results show that λ serves as a parameter that controls the velocity of a moving particle on an inclined surface, as it increases the asymmetry of the frictional conditions, resulting in a larger magnitude of the net force.

3.2. Experimental Results

The experimental transportation platform was subjected to sinusoidal oscillations characterized by an amplitude of A = 2.04 mm and an angular frequency of ω = 65.8 rad/s. The transportation of granular particles was achieved by adjusting and modifying the values of λ and ϕ. The transportation of granular salt was studied using two different flow channels, measuring 1.5 cm and 3 cm in width and 10 cm in length. The factor-of-two difference in width enables direct comparison between confined and weakly confined flow regimes under identical experimental conditions. Approximately 5 g of granular salt was initially poured at the tip of each channel. The transported granular salt’s average velocity and flow rate were measured using a stopwatch and a micro-weight scale.

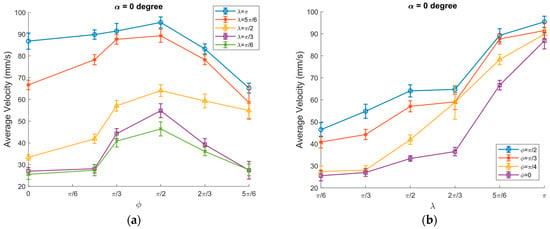

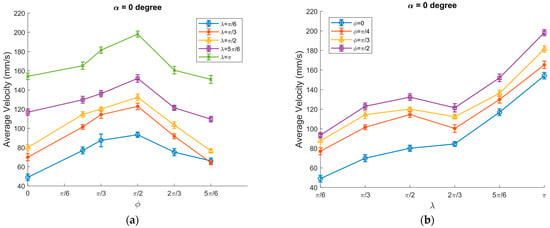

The average velocity of granular salt particles was significantly increased and reached the highest value of 92 mm/s at λ = π, ϕ = π/2 and the minimum value of 65 mm/s at λ = π and ϕ = 5π/6 at α = 0 degrees, A = 2.04 mm, ω = 65.8 rad/s, μ0 = 0.3, μm /μ0 = 3/10, and channel width 3 cm, as presented in Figure 7a. The average velocity of the moving object dramatically increased and achieved the highest value at λ = π and ϕ = π/2, as demonstrated in Figure 7b. The width of the modified dry friction λ has significantly influenced the velocity of granular particles.

Figure 7.

Average transportation velocity of granular particles vs.: (a) ϕ; (b) λ at α = 0 degrees, A = 2.04 mm, ω = 65.8 rad/s, μ0 = 0.3, ⟨μm⟩/μ0 = 3/10 and channel width = 3 cm.

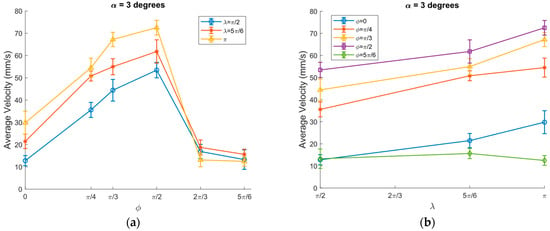

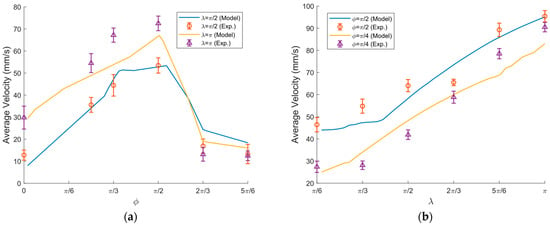

The average velocity of granular particles significantly decreased after subjecting the platform to a 3 degrees inclination angle. The average velocity reached the highest values at a phase shift of ϕ = π/2 and λ = π (Figure 8a). At 3 degrees inclination angle, the granular particles achieved motion mainly at three significant parameters λ = π/2, λ = 5π/6, and λ = π. The highest value average of the average velocity was achieved at λ = π and ϕ = π/2, where α = 3 degrees, A = 2.04 mm, ω = 65.8 rad/s, μ0 = 0.3 and μm /μ0 = 3/10, as presented in Figure 8b. These findings proves that λ serves as a parameter that controls the velocity of the granular salts.

Figure 8.

Average transportation velocity of granular particles vs.: (a) ϕ; (b) λ at α = 3 degrees, A = 2.04 mm, ω = 65.8 rad/s, μ0 = 0.3, ⟨μm⟩/μ0 = 3/10 and channel width = 3 cm.

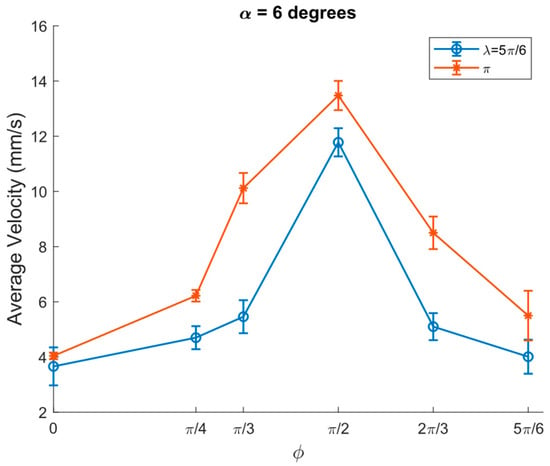

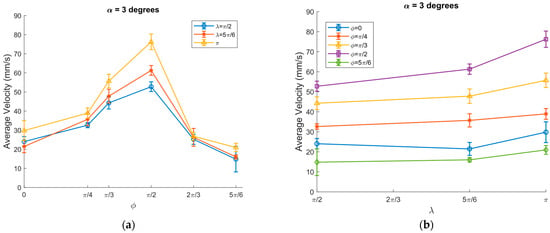

Various experiments have been carried out to determine the influence of the inclination angle on the transportation characteristics of granular particles, where the transportation of the granular particles was limited to specific parameters of ϕ and λ while they were moving upwards at an inclination angle of 6 degrees. As depicted in Figure 9, the average velocity reached the highest values of 14 mm/s and 12 mm/s at λ = π and λ = 5π/6, respectively, and at ϕ = π/2. The average velocity started to be lowered until it reached the minimum at ϕ = 5π/6.

Figure 9.

Average transportation velocity of granular particles vs. ϕ at α = 6 degrees, A = 2.04 mm, ω = 65.8 rad/s, μ0 = 0.3 and ⟨μm⟩/μ0 = 3/10, channel width = 3 cm.

The flow rate of the granular particles has been taken into consideration. Besides demonstrating the average velocity of the moving granular particles, the flow rate of the objects was observed and calculated. A micro weighing scale of 0.01 g–100 g and a stopwatch were used to determine the flow rate. Using this method, the flow rate of the granular particles at different inclination angles of 0, 3, and 6 degrees could be determined.

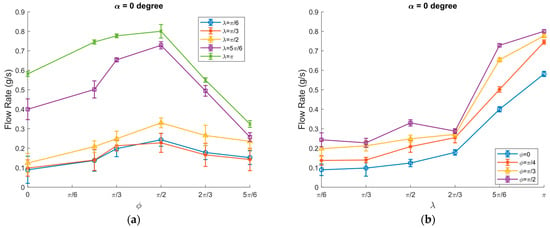

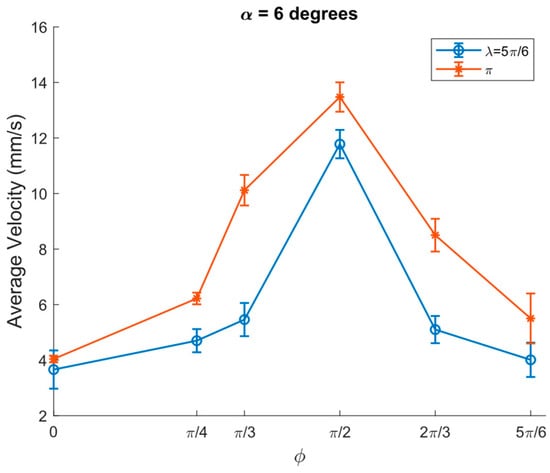

The flow rate was significantly increased in a range from ϕ = 0 to ϕ = π/2 and reached its maximum of approximately 0.8 g/s at λ = π. As λ increased further, it started to decrease and reached a minimum at ϕ = 5π/6 (Figure 10a). λ plays a significant role in controlling the flow rate. The flow rate reached a highest value at ϕ = π/2 and λ = π, as demonstrated in Figure 10b.

Figure 10.

The flow rate of granular particles vs.: (a) ϕ; (b) λ at α = 0 degrees, A = 2.04 mm, ω = 65.8 rad/s, μ0 = 0.3, and ⟨μm⟩/μ0 = 3/10, channel width = 3 cm.

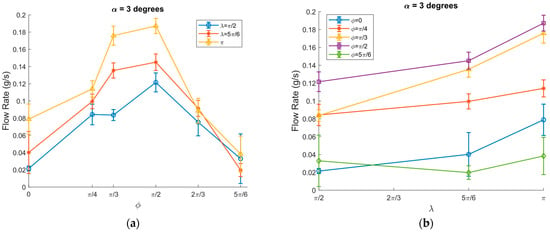

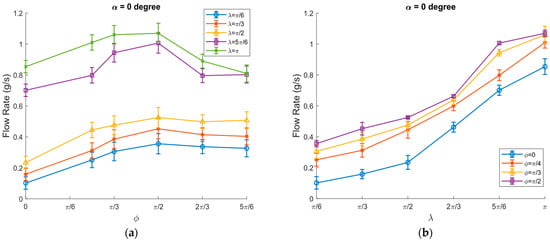

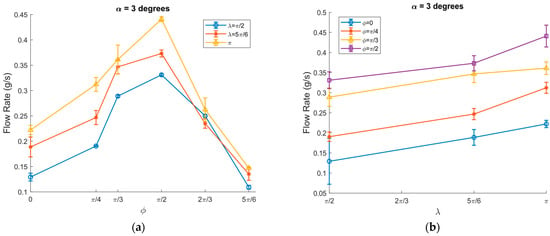

The flow rate was significantly decreased when the inclination angle of the transportation surface increased to 3 degrees. The maximum flow rate was approximately 0.2 g/s at ϕ = π/2 and λ = π. As ϕ increased further, it started to decrease and reached almost 0 g/s at ϕ = 5π/6, as shown in Figure 11a. The flow rate as a function of λ was sharply increased from λ = π/2 to λ = π (Figure 11b). The reduction in flow rate at higher inclination angles is due to the increased gravitational potential energy acting on the objects, which affects their motion.

Figure 11.

The flow rate of granular particles vs.: (a) ϕ; (b): λ at α = 3 degrees, A = 2.04 mm, ω = 65.8 rad/s, μ0 = 0.3, and ⟨μm⟩/μ0 = 3/10, channel width = 3 cm.

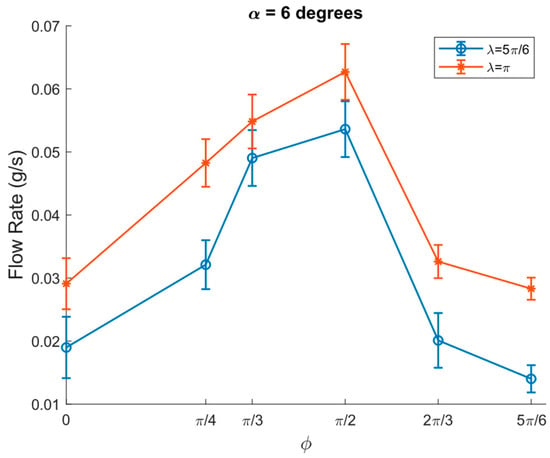

At 6 degrees inclination angle, the flow rate was decreased and reached a maximum of 0.06 g/s at ϕ = π/2 and λ = π, as illustrated in Figure 12. The transportation of the granular particles became effective only under specific parameters at higher inclination angles. For example, at 6 degrees inclination angle, the granular particles were able to move only on a modified dry friction coefficient of λ = π and λ = 5π/6.

Figure 12.

Flow rate of granular particles vs. ϕ at α = 6 degrees, A = 2.04 mm, ω = 65.8 rad/s, μ0 = 0.3, and ⟨μm⟩/μ0 = 3/10, channel width = 3 cm.

Transportation of Granular Particles in a Channel Width of 1.5 cm and Length of 10 cm

The transportation velocity of the granular particles was significantly increased at a 1.5 cm channel width. As shown in Figure 13a, the average velocity reached its highest value of approximately 200 mm/s at ϕ = π/2 and λ = π. λ has shown a more pronounced effect on the velocity of the granular particles, as illustrated in Figure 13b.

Figure 13.

Average transportation velocity of granular particles vs.: (a) ϕ; (b) λ at α = 0 degrees, A = 2.04 mm, ω = 65.8 rad/s, μ0 = 0.3, ⟨μm⟩/μ0 = 3/10 and channel width = 1.5 cm.

The average velocity of granular particles decreased when the inclination angle was α = 3 degrees. The average velocity reached its highest value of around 80 mm/s at a phase shift of ϕ = π/2 and λ = π (Figure 14a). At 3 degrees inclination angle, the granular particles were able to move at three parameters λ = π/2, λ = 5π/6, and λ = π. The highest value of the average velocity was observed at λ = π and ϕ = π/2, where α = 3 degrees, A = 2.04 mm, ω = 65.8 rad/s, μ0 = 0.3 and μm /μ0 = 3/10 as presented in Figure 14b.

Figure 14.

Average transportation velocity of granular particles vs.: (a) ϕ; (b) λ at α = 3 degrees, A = 2.04 mm, ω = 65.8 rad/s, μ0 = 0.3, ⟨μm⟩/μ0 = 3/10 and channel width = 1.5 cm.

Similarly, the experiments were performed at a higher inclination angle of 6 degrees, the maximum inclination angle at which the motion of granular particles can be achieved at a channel width of 1.5 cm. The average velocity reached the highest values of 29 mm/s and 22 mm/s at λ = π and λ = 5π/6, respectively, and at ϕ = π/2, as shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Flow rate of granular particles vs. ϕ at α = 6 degrees, A = 2.04 mm, ω = 65.8 rad/s, μ0 = 0.3, and ⟨μm⟩/μ0 = 3/10, channel width = 1.5 cm.

The flow rate was significantly increased between ϕ = 0 and ϕ = π/2 and reached a maximum of approximately 1 g/s at λ = π. As ϕ increased further, it started to decrease and reached a minimum at ϕ = 5π/6 (Figure 16a). As λ increased, the flow rate increased as well, reaching a highest value at ϕ = π/2 and λ = π (Figure 16b).

Figure 16.

Flow rate of granular particles vs.: (a) ϕ; (b) λ at α = 0 degrees, A = 2.04 mm, ω = 65.8 rad/s, μ0 = 0.3, and ⟨μm⟩/μ0 = 3/10, channel width = 1.5 cm.

The flow rate was significantly decreased when the inclination angle of the transportation surface increased to 3 degrees. The maximum flow rate was approximately 0.45 g/s at ϕ = π/2 and λ = π. As ϕ increased further, it started to decrease and reached almost 0.15 g/s at ϕ = 5π/6 (Figure 17a). The flow rate increased from 0.33 g/s to 0.45 g/s as λ increased from λ = π/2 to λ = π at ϕ = π/2 (Figure 17b).

Figure 17.

Flow rate of granular particles vs.: (a) ϕ; (b) λ at α = 3 degrees, A = 2.04 mm, ω = 65.8 rad/s, μ0 = 0.3, and ⟨μm⟩/μ0 = 3/10, channel width = 1.5 cm.

3.3. Comparison of the Experimental and Model Results

Figure 18 presents a comparison of the experimental and modeled results. The experimental values were slightly higher than those predicted by the model. One possible reason for this discrepancy is that the model did not account for the relationship between the effective friction coefficient and the relative sliding velocity. Nevertheless, the observed differences were within acceptable limits, and the experimentally determined average transport velocity closely mirrored the trends predicted by the model. A Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to determine the relationship between the experimental results and the model values. The study yielded a Pearson correlation coefficient of r = 0.855, indicating a strong positive linear relationship between the experimental data and the model outputs. The associated coefficient of determination (R2) was calculated as 0.730, implying that the model can explain approximately 73% of the variance in the experimental values. The correlation was found to be statistically significant (p = 0.030), confirming the validity of the relationship.

Figure 18.

Comparison of experimental and modeled average velocity as a function of: (a) ϕ; (b) λ at A = 2.04 mm, ω = 65.8 rad/s, μ0 = 0.3, and ⟨μm⟩/μ0 = 3/10.

4. Conclusions

The directional motion of the granular salts on an inclined surface subjected to sinusoidal oscillations has been studied, and the motion was achieved through dynamic dry friction manipulation.

The modelling results proved that in an inclined transportation system, the asymmetry of frictional conditions during the oscillation cycle—created through dynamic dry friction manipulations—generates a net frictional force exceeding the gravitational force, thereby enabling the upward movement of granular particles. Additionally, the findings highlighted the key control parameters governing the motion of granular particles. at various inclination angles. λ, which represents the segment of the sinusoidal period over which the friction is dynamically lowered, serves as a parameter that controls the velocity of a moving particle on an inclined surface, as it increases the asymmetry of the frictional conditions, resulting in a larger magnitude of the net force. The phase shift ϕ serves as a parameter that controls the direction of the particle’s motion, as this parameter determines the phase shift that sets the asymmetry of the frictional conditions and, as a result, the orientation of the net force vector.

Experimental investigations were conducted to validate and evaluate the technical feasibility of the proposed method. The experiments were carried out on two different flow channels, 1.5 and 3 cm in width. The findings confirmed that the granular particles can be transported upward along the inclined surface with an inclination angle of up to 6 degrees. The experimental findings have demonstrated that at the flow rate and average velocity reached higher values in the narrower flow channel with a width of 1.5 cm. In this case, under an inclination angle of 3 degrees, the highest value of the average velocity was observed at λ = π and ϕ = π/2, and the flow rate increased from 0.33 g/s to 0.45 g/s as λ increased from λ = π/2 to λ = π at ϕ = π/2.

The experimental results provided both qualitative and quantitative validation of the model by illustrating that motion parameters exhibit comparable responses to the control parameters, and strongly agree with the theoretical findings. The associated coefficient of determination (R2) was calculated as 0.73, implying that the model can explain approximately 73% of the variance in the experimental values.

The proposed vibrational transport method offers precise control over the direction and velocity of granular particles’ flow through tunable parameters (λ and ϕ). Compared to conventional techniques, this method enables the bidirectional transport of granular particles on the same plane. Therefore, the system is suitable for a range of practical applications, including the upward transport of granular materials for processing and their downward conveyance for recirculation or discharge. Such a configuration is particularly advantageous in batch-processing operations, where materials must be repositioned multiple times. In addition, the system can function as a temporary buffer, allowing excess material to be redirected downward when downstream equipment reaches capacity. The method is well-suited to assembly-line and manufacturing environments, as well as to industries involved in the processing and handling of granular materials, where controlled transport, repositioning, or recirculation of granular materials or small discrete components is required.

Future research will focus on developing a more detailed model that accounts for particle interactions and provides a comprehensive representation of adhesive behaviour, as well as on investigating its applicability across different materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.E.B., S.K.; methodology, R.E.B., S.K.; software, R.E.B., K.L., S.K.; validation, R.E.B.; formal analysis, R.E.B., S.K.; investigation, R.E.B.; resources, R.E.B., R.Č. M.L., M.D.; data curation, R.E.B.; writing—original draft preparation, R.E.B.; writing—review and editing, R.E.B., K.L., R.Č., M.L., M.D., S.K.; visualization, R.E.B.; supervision, S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ongoing research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ragulskis, K.; Spruogis, B.; Bogdevičius, M.; Matuliauskas, A.; Mištinas, V.; Ragulskis, L. Mechanical systems of precise robots with vibrodrives, in which the direction of the exciting force coincides with the line of relative motion of the system. Mechanika 2021, 27, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feemster, M.; Piepmeier, J.A.; Biggs, H.; Yee, S.; ElBidweihy, H.; Firebaugh, S.L. Autonomous microrobotic manipulation using visual servo control. Micromachines 2020, 11, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Jiang, C.; Li, G.; Lu, Q.; Chen, H. Design and Analysis of a Light-Operated Microgripper Using an Opto-Electrostatic Repulsive Combined Actuator. Micromachines 2021, 12, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, P.; Valarezo Añazco, E.; Kim, T. Object Manipulation with an Anthropomorphic Robotic Hand via Deep Reinforcement Learning with a Synergy Space of Natural Hand Poses. Sensors 2021, 21, 5301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warnat, S.; King, H.; Wasay, A.; Sameoto, D.; Hubbard, T. Direct integration of MEMS, dielectric pumping and cell manipulation with reversibly bonded gecko adhesive microfluidics. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2016, 26, 097001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janusas, T.; Urbaite, S.; Palevicius, A.; Nasiri, S.; Janusas, G. Biologically Compatible Lead-Free Piezoelectric Composite for Acoustophoresis Based Particle Manipulation Techniques. Sensors 2021, 21, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ma, T.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, J.; Hu, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Zheng, H. 3D Acoustic Manipulation of Living Cells and Organisms Based on 2D Array. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 69, 2342–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chircov, C.; Grumezescu, A.M. Microelectromechanical Systems (MEMS) for Biomedical Applications. Micromachines 2022, 13, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, N.F.A.; Deivasigamani, R.; Wee, M.F.; Hamzah, A.A.; Buyong, M.R. Integration of a Dielectrophoretic Tapered Aluminum Microelectrode Array with a Flow Focusing Technique. Sensors 2021, 21, 4957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reznik, D.; Canny, J.; Goldberg, K. Analysis of part motion on a longitudinally vibrating plate. In Proceedings of the 1997 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robot and Systems, Grenoble, France, 11 September 1997; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1997; pp. 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayyas, M. Modeling and analysis of vibratory feeder system based on robust stick–slip motion. J. Vibrat. Control 2021, 28, 2301–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayyas, M. Parallel Manipulation Based on Stick-Slip Motion of Vibrating Platform. Robotics 2020, 9, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswarupachari, C.; DasGupta, A.; Pratik Khastgir, S. Vibration induced directed transport of particles. J. Vib. Acoust. 2012, 134, 051005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunnekens, B.G.B.; Fey, R.H.B.; Shukla, A. Vibrational self-alignment of a rigid object exploiting friction. Nonlinear Dyn. 2010, 65, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baksys, B.; Baskutiene, J. The directional motion of the compliant body under vibratory excitation. Int. J. Non Linear Mech. 2012, 47, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baksys, B.; Puodziuniene, N. Modeling of vibrational non-impact motion of mobile-based body. Int. J. Non Linear Mech. 2012, 40, 861–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashimori, M.; Yamaguchi, K.; Shibata, A. Omnidirectional Nonprehensile Manipulation Using Only One Actuator. Robotics 2018, 7, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, M.; Shirode, K.; Yamato, S.; Tanaka, K.; Kanamori, H. Granular vibration pumping system for handling and characterizing particulate materials. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2024, 95, 055102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, P.U.; Wiesendanger, M.; Büchi, R.; Ruf, L. Simultaneous planar transport of multiple objects on individual trajectories using friction forces. In Distributed Manipulation; Böhringer, K.F., Choset, H., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrublevskyi, I. Vibratory conveying by harmonic longitudinal and polyharmonic normal vibrations of inclined conveying track. J. Vib. Acoust. 2022, 144, 011004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzoni, M.; Battarra, M.; Mucchi, E.; Dalpiaz, G. Motion analysis of a linear vibratory feeder: Dynamic modeling and experimental verification. Mech. Mach. Theory 2017, 114, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursky, V.; Krot, P.; Korendiy, V.; Zimroz, R. Dynamic Analysis of an Enhanced Multi-Frequency Inertial Exciter for Industrial Vibrating Machines. Machines 2022, 10, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, S.; Perchtold, D.; Steiner, W. Nonlinear and chaotic dynamics of a vibratory conveying system. Nonlinear Dyn. 2023, 111, 9799–9814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemiato, M.; Czubak, P. Control of the transport direction and velocity of the two-way reversible vibratory conveyor. Arch. Appl. Mech. 2019, 89, 1359–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, X.; Kojima, M.; Huang, Q.; Arai, T. Advances in Micromanipulation Actuated by Vibration-Induced Acoustic Waves and Streaming Flow. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; DasGupta, A. Generation of circumferential harmonic travelling waves on thin circular plates. J. Sound. Vib. 2020, 478, 115343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.X.; Jung, D.; Lee, H.; Go, G.; Nan, M.; Choi, E.; Kim, C.; Park, J.; Kang, B. Micromotor Manipulation Using Ultrasonic Active Traveling Waves. Micromachines 2021, 12, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palencia, J.L.D. Travelling Waves Approach in a Parabolic Coupled System for Modelling the Behaviour of Substances in a Fuel Tank. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharkongor, B.; Pohlong, S.S.; Mahato, M.C. Net transport in a periodically driven potential-free system. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2021, 562, 125341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, T.C.; Zhang, X.; Adiga, D.; Miller, G.H.; Ristenpart, W.D. Vibrational manipulation of dry granular materials in lab-on-a-chip devices. Lab A Chip 2024, 24, 966–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunst, P.; Bornmann, P.; Hemsel, T.; Sextro, W. Vibration-assisted handling of dry fine powders. Actuators 2018, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilikevičius, S.; Liutkauskienė, K.; Uldinskas, E.; El Banna, R.; Fedaravičius, A. Omnidirectional Manipulation of Microparticles on a Platform Subjected to Circular Motion Applying Dynamic Dry Friction Control. Micromachines 2022, 13, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilikevičius, S.; Fedaravičius, A. Vibrational Transportation on a Platform Subjected to Sinusoidal Displacement Cycles Employing Dry Friction Control. Sensors 2021, 21, 7280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.