Abstract

This study provides a systematic overview of Natural Language Processing (NLP)-based frameworks for Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) and the early prediction of cyberattacks in Industry 4.0. As digital transformation accelerates through the integration of IoT, SCADA, and cyber-physical systems, manufacturing environments face an expanding and complex cyber threat landscape. Following the PRISMA 2020 systematic review protocol, 80 peer-reviewed studies published between 2015 and 2025 were analyzed across IEEE Xplore, Scopus, and Web of Science to identify methods that employ NLP for CTI extraction, reasoning, and predictive modelling. The review finds that transformer-based architectures, knowledge graph reasoning, and social media mining are increasingly used to convert unstructured data into actionable intelligence, thereby enabling earlier detection and forecasting of cyber threats. Large Language Models (LLMs) demonstrate strong potential for anticipating attack sequences, while domain-specific models enhance industrial relevance. Persistent challenges include data scarcity, domain adaptation, explainability, and real-time scalability in operational-technology environments. The review concludes that NLP is reshaping Industry 4.0 cybersecurity from reactive defense toward predictive, adaptive, and intelligence-driven protection, and it highlights the need for interpretable, domain-specific, and resource-efficient frameworks to secure Industry 4.0 ecosystems.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

Industry 4.0, or the fourth industrial revolution, is, in fact, a radical change in production brought about by the infusion of cyber-physical systems, IoT, cloud computing, and artificial intelligence. The digital transformation in production now enables autonomous decision-making, real-time analytics, and connected supply chains to work together effectively, blurring the boundary between the physical and digital worlds [1]. Factories are taking steps toward becoming smart environments by leveraging data, thereby enabling unprecedented efficiency and productivity; however, this also increases the attack surface available to threat actors [2].

Increasing usage of IoT devices, Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA), and Industrial Control Systems (ICS) makes it easy for cyber intrusions into the manufacturing environment [3]. Scholarly work and real-world scenarios have demonstrated that a supposedly isolated manufacturing network can be compromised via indirect vectors and multi-stage attack chains. Researchers have demonstrated that Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs), Human–Machine Interfaces (HMIs), and robotic systems within modular smart factories can be exploited to initiate physical disruption even under an air-gapped configuration [4]. Vulnerabilities within Cyber-Physical Production Systems (CPPS) create multiple pathways through which cascading failures between subsystems can propagate, increasing operational risk [4].

Further, experiments on the SCADA infrastructures of petrochemical plants have shown that altering sensor or control data can lead to process instability and safety risks [5]. Research on automated composite manufacturing emphasises that cyber sabotage of production lines is possible [6]. These scenarios demonstrate that perimeter defence or signature-based detection cannot be relied upon for manufacturing security; rather, predictive and adaptive safeguards that anticipate dynamic threats are needed.

Large-scale attacks occurred in the United Kingdom in 2025, when Marks & Spencer suffered a supply chain breach and production at Jaguar Land Rover had to be shut down [7,8,9], thereby highlighting how cyberattacks on Industry 4.0 ecosystems can take many cascading forms, both economically and operationally. This paper demonstrates an acute need for pre-emptive cybersecurity interventions using deep learning and natural language processing to detect threats before they fully materialise.

1.2. Problem Statement

Despite growing awareness of cybersecurity risks in Industry 4.0, most cyber defence methodologies remain proactive and general. The arsenal of signatures-based Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS), rule-driven firewalls, or periodic vulnerability assessments falls short of identifying new, case-specific threats in complex industrial environments. Because these defence systems rely on pre-established attack signatures to function, they struggle to keep pace with rapidly evolving threats that outpace the deployment of security updates. Traditional cybersecurity frameworks treated Information Technology (IT) and Operational Technology (OT) as fundamentally separate problems, seeking separate security solutions, thereby overlooking that modern Industry 4.0 systems require integrated security monitoring that accounts for the convergence and interdependencies between the two domains [2].

Another gap is in the lack of domain-specific cyber threat intelligence. Most available CTIs are oriented toward enterprise IT or cloud environments rather than ICS, SCADA, or IoT-enabled manufacturing networks. This, by extension, yields a very high level of useful, actionable intelligence for industry stakeholders regarding specific vulnerabilities by sector, attack vectors, and adversarial behaviours [10]. Predictive capabilities, such as early-warning systems that forecast attack patterns or exploit propagation, remain underdeveloped in research on cybersecurity within manufacturing.

There is, therefore, an urgent need to adopt advanced analytical techniques that can accommodate large volumes of unstructured data, such as vulnerability reports, social media chats, security advisories, and technical forums. One pathway to automation, among others proposed in this paper, is the use of NLP. This kind of automation enables earlier threat detection, thereby enhancing situational awareness and moving from reactive defence toward predictive and proactive cybersecurity in Industry 4.0 manufacturing systems.

1.3. Objectives of the Review

This literature review aims to explore and synthesise recent research on NLP-based cybersecurity frameworks to enhance predictive threat intelligence and realise Industry 4.0 environments. It attempts to carry out the following:

- Identify and classify existing NLP-driven frameworks, algorithms, and methodologies used for CTI extraction, threat detection, and early attack prediction within Industry 4.0.

- Assess how these NLP-driven methods fit within manufacturing and industrial control settings, particularly in Internet of Things (IoT), SCADA, and ICS contexts.

- Evaluate research gaps at the crossroad of NLP, CTI, and Industry 4.0 cybersecurity on matters related to data quality as well as interpretability and scalability issues.

- Offer future research directions that integrate predictive analytics, AI, and NLP to develop anticipatory, domain-specific cybersecurity schemes for digital manufacturing systems.

This review, therefore, aims to achieve these goals and provides a structured understanding of how NLP technologies can be leveraged for cyber resilience and threat anticipation in systems within the context of Industry 4.0.

1.4. Scope and Contribution

The scope of this content centres on peer-reviewed academic literature and technical reports that discuss the application of NLP, Artificial Intelligence AI, and machine learning to cybersecurity, particularly for CTI extraction and modelling future threats.

The review focuses on studies published between 2015 and 2025, a period of rapid emergence of Industry 4.0 technologies and advances in NLP. The inclusion criteria cover studies that:

- Assess NLP-based systems for cyber threat analysis, information extraction, or predictive attack modelling.

- Apply these techniques in contexts relevant to Industry 4.0, including manufacturing, IoT, ICS, and SCADA systems.

- Offer empirical evaluations, comparative analyses, or frameworks showing measurable improvement in detection or prediction capability.

Studies that focus solely on non-industrial or purely theoretical applications of NLP without practical or experimental validation in cybersecurity contexts shall be excluded.

The contribution of this review is threefold. First, it synthesized disparate research on NLP-based CTI and predictive defence mechanisms into a single framework. Second, a critical assessment has been made of the practical implementability and adaptability of these approaches in manufacturing environments that inherently possess heterogeneous data sources and real-time operational requirements. Third, existing challenges have been articulated, ranging from the scarcity of labelled industrial datasets and the semantic vagueness inherent in unstructured threat intelligence data to IT/OT integration barriers, and future research avenues to mitigate them have been proposed. In sum, this paper adds academic and practitioner insights toward reframing industrial cybersecurity from a logic of reactive threat response to an anticipatory, intelligent, Data-Driven Predictive Defence.

2. Background

Cybersecurity Threat Intelligence (CTI) refers to cyber threat information that has been systematically aggregated, analysed, and contextualised to support informed security decision-making [11]. Its primary objective is to transform raw data into actionable intelligence concerning threat actors, their capabilities, intentions, and operational methods, thereby enabling organisations to move from reactive defence mechanisms toward intelligence-driven security operations.

CTI is typically categorised into four complementary levels: strategic, operational, tactical, and technical intelligence [12,13]. Strategic CTI focuses on long-term threat trends, geopolitical drivers, and adversary motivations to support executive decision-making and policy formulation. Operational CTI examines adversary campaigns, infrastructure, and capabilities over medium timeframes to assist analysts and incident responders. Tactical CTI addresses tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs), enabling anticipation of attack behaviours, while technical CTI provides short-lived Indicators of Compromise (IoCs), such as IP addresses or file hashes, for direct integration into detection systems. This layered taxonomy ensures the relevance of intelligence across organisational and operational levels, although its transient nature necessitates continuous updating and automation.

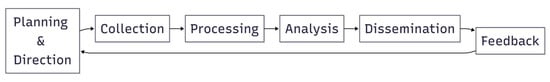

The CTI life cycle provides a structured framework for converting raw data into actionable intelligence. Adapted from classical intelligence models, it comprises six iterative phases: direction and planning, collection, processing, analysis, dissemination, and feedback [12,14,15], as illustrated in Figure 1. Intelligence requirements guide data collection from diverse sources, after which data are normalised and analysed to extract patterns and insights. Intelligence products are then disseminated to relevant stakeholders, and feedback is incorporated to refine subsequent cycles. This continuous process ensures alignment with organisational objectives and evolving threat landscapes [16].

Figure 1.

Six-phase cyber threat intelligence cycle.

The increasing volume and unstructured nature of CTI data have positioned NLP as a critical enabler within the CTI process. NLP integrates linguistics, computer science, and artificial intelligence to enable machines to process and interpret human language [17]. Early NLP systems relied on rule-based approaches grounded in linguistic theory [18], but their inability to address ambiguity and variability prompted a transition to data-driven statistical methods [19].

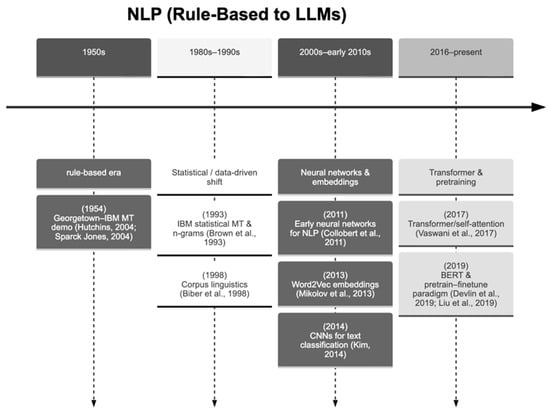

The emergence of deep learning marked a paradigm shift in NLP. Architectures such as Long Short-Term Memory networks, Convolutional Neural Networks, and transformers significantly improved the modelling of semantic and contextual relationships in text [20,21,22]. As shown in Figure 2, this led to the development of pre-trained language models such as BERT and GPT, which demonstrated that large-scale pre-training followed by task-specific fine-tuning achieves state-of-the-art performance across a wide range of NLP tasks [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30].

Figure 2.

Natural Language Processing: Historical Development [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30].

Transformer-based models, such as BERT and its variants, have demonstrated strong potential for converting textual CTI into predictive indicators, particularly when combined with knowledge graphs that encode relationships among vulnerabilities, attack techniques, and threat actors. These integrated ML–NLP systems enhance situational awareness and support pre-emptive response strategies, although challenges related to data quality, domain adaptation, and class imbalance remain significant [31].

These challenges are particularly acute within Industry 4.0 environments. Industry 4.0 represents the convergence of cyber-physical systems, IoT, artificial intelligence, and data-driven automation within industrial contexts [32]. While these technologies enable real-time monitoring, predictive maintenance, and adaptive manufacturing, they also expand the attack surface by increasing connectivity between information technology (IT) and operational technology (OT) systems [33]. Consequently, cybersecurity has become a foundational requirement for ensuring the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of industrial systems.

Industrial environments face a range of cyber threats, including ransomware, industrial espionage, advanced persistent threats, and insider attacks. High-profile incidents have demonstrated the severe operational and financial consequences of cyberattacks on manufacturing and critical infrastructure. These risks are exacerbated by legacy systems, inadequate network segmentation, and skills shortages. To mitigate such threats, standards such as the NIST Cybersecurity Framework and IEC 62443 [34,35,36,37,38] provide structured guidance for securing industrial automation and control systems [39,40].

Despite the availability of frameworks, implementing CTI effectively in Industry 4.0 remains challenging. Heterogeneous networks, organisational silos between IT and OT teams, limited expertise, and constrained resources, particularly among small and medium-sized enterprises, hinder the adoption of advanced CTI solutions [41,42]. Moreover, predictive CTI systems depend on the availability of large volumes of high-quality domain-specific data, which are often scarce. Addressing these barriers requires not only technological advances but also organisational change, workforce development, and cross-sector collaboration to strengthen cyber resilience.

3. Methodology

3.1. Review Protocol

This paper made use of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) structure to ensure replicability and reduce bias (Supplementary Materials). The systematic review protocol was prospectively registered in the Open Science Framework (OSF) to enhance transparency and methodological rigor (DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/5SAJW). This review also applied known Systematic Literature Review (SLR) methods [43]. Three major academic databases were selected to ensure comprehensive coverage of high-quality peer-reviewed literature in the areas of investigation: artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, and industrial systems: IEEE Xplore, Scopus, and Web of Science (WoS). The review protocol consisted of four stages:

- Defining research objectives and questions,

- Developing the search strategy,

- Establishing inclusion and exclusion criteria, and

- Extracting and synthesising data.

The main objective was to identify and analyse studies on NLP-based frameworks for CTI and early prediction of cyberattacks in manufacturing and Industry 4.0 environments.

3.2. Search Strategy

A systematic, repeatable search strategy was formulated to identify studies at the intersection of NLP, CTI, and manufacturing or industrial cybersecurity. In line with PRISMA and SLR best-practice principles, search terms were formulated through an iterative process that included reviewing pilot results and refining keyword groupings. The search was conducted in three major electronic databases, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, and Web of Science (WoS). As shown in Table 1, Boolean operators (AND, OR) and database-specific field tags were used to systematically combine key concepts.

Table 1.

Summary of the three main conceptual themes and their associated synonyms and related terms that were used to build all search expressions.

The search combined one or more terms from each theme to ensure that retrieved publications explicitly addressed all three research dimensions:

- The application of NLP methods,

- their use in CTI or cyber-attack prediction, and

- their deployment or relevance within manufacturing or industrial environments.

Search Parameters

- Databases searched: IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science (WoS)

- Publication years: 2015–2025

- Language: English

- Document types: Peer-reviewed journal articles and conference papers

- Subject areas: Computer Science, Cybersecurity, Engineering, and Industrial Systems

The keyword sets were finalized using the relevant database-specific search syntax. This ensured that a precise, comparable result set was generated across all sources and that all relevant literature was obtained for subsequent screening.

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To ensure rigour and relevance, the following criteria were applied:

3.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Peer-reviewed studies published between 2015 and 2025.

- Research written in English.

- Studies directly addressing NLP, CTI, or cyberattack prediction in manufacturing, Industry 4.0, or ICS contexts.

- Articles proposing or evaluating NLP-based frameworks or models for cybersecurity or threat intelligence.

3.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Non-English publications.

- Non-peer-reviewed literature (e.g., theses, reports).

- Studies not integrating NLP and CTI concepts.

- Duplicate records retrieved across databases.

- Records representing conference names only (not full papers).

After deduplication and screening, five duplicates were removed, and one study was excluded because it was a conference entry rather than a full research paper.

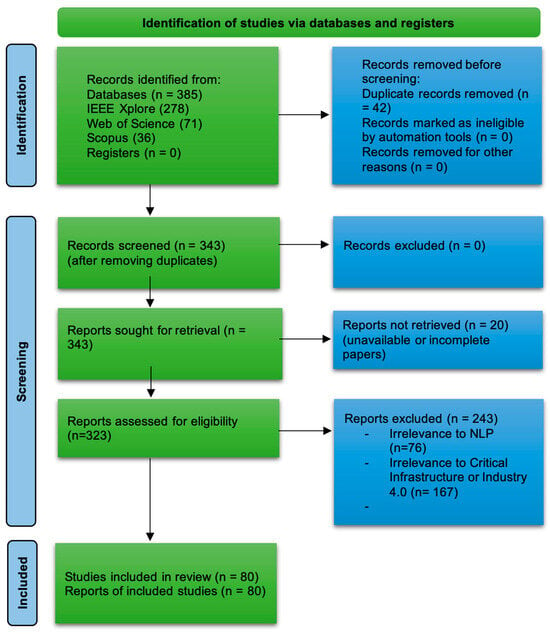

3.4. PRISMA Flow of Study Selection

The literature selection process followed the PRISMA 2020 framework, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for study selection [44].

A total of 385 records were retrieved from the three databases; see Table 2. After removing 42 duplicates, 343 studies were screened. All were retrieved for full-text assessment; 20 records were excluded because they were conference names or lacked a full paper. Subsequently, 243 records were excluded as they were outside the research scope. Finally, 80 studies were included in the review.

Table 2.

Database Results.

3.5. Data Extraction and Analysis

A structured data extraction sheet was created using the consolidated dataset of 80 records. Each paper was analysed using predefined attributes to facilitate thematic and quantitative synthesis.

Data Extraction Fields:

- Bibliographic details: Author(s), year, and source.

- Methodology: Research design, model type, or framework used.

- NLP Technique: e.g., Transformer, BERT, LLM, …

The analysis emphasised the identification of trends in NLP methodologies applied to CTI, their effectiveness in early attack prediction, and gaps in industrial cybersecurity research.

4. Results

This section presents the results of the systematic literature review through a domain-based thematic synthesis, analysing how NLP and language-centric machine learning techniques are applied across different cyber–physical platforms. Rather than grouping studies solely by algorithms or tasks, the analysis is structured around application domains, including industrial manufacturing systems, power and energy infrastructures, the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), and emerging cyber–physical domains such as electric vehicles and smart grids.

This domain-oriented organisation reflects the reality that cybersecurity requirements, data characteristics, operational constraints, and risk profiles differ substantially across platforms. As a result, the role of NLP, whether in threat intelligence extraction, anomaly detection, reasoning, or explanation, varies across domains. The themes, therefore, capture how NLP is adapted and operationalised within each platform, while also revealing common methodological trends and cross-domain convergence toward transformer-based and LLM-centric approaches.

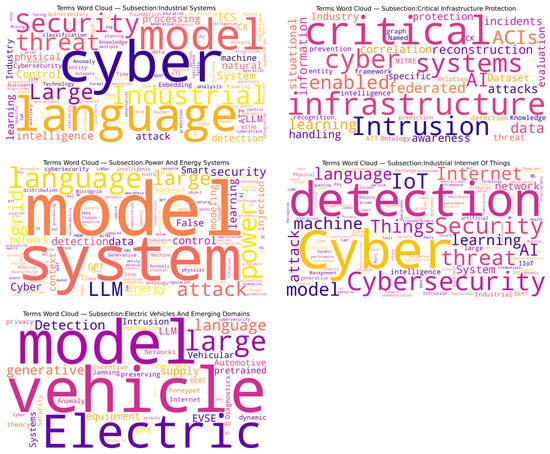

To provide an initial, high-level characterization of the reviewed literature within each domain, Figure 4 presents five word clouds generated from the authors’ keywords, corresponding to industrial systems, power and energy infrastructures, critical infrastructure, IIoT, and emerging cyber–physical domains such as electric vehicles. These word clouds visually highlight the dominant concepts, security concerns, and methodological emphases within each platform. While shared themes such as “cybersecurity”, “intrusion detection”, “machine learning”, and “language models” appear across domains, domain-specific priorities are also evident—for example, control- and grid-oriented terms in power systems, infrastructure resilience and incident handling in critical infrastructure, and scalability and device-centric security in IIoT. The word clouds, therefore, serve as an illustrative complement to the subsequent thematic analysis, motivating the domain-based structure adopted in this section.

Figure 4.

Word cloud generated from the authors’ keywords of the reviewed papers for each subsection.

4.1. Industrial Systems

Industrial cybersecurity research increasingly relies on NLP to convert heterogeneous, unstructured sources, including CTI reports, vulnerability descriptions, incident tickets, and system logs, into structured representations that can support detection, attribution, and response. Across the reviewed studies, three NLP task families dominate: (i) information extraction (NER, relation extraction, event extraction), (ii) text/sequence classification (attack technique classification, log/alert labeling), and (iii) semantic matching and retrieval (taxonomy alignment, similarity search, RAG). The literature also shows a clear methodological evolution from sparse lexical baselines (TF-IDF) and recurrent neural networks toward transformer encoders and LLM-centric pipelines.

4.1.1. Threat Intelligence Extraction: NER and Relation Extraction

Named Entity Recognition (NER) is the most common entry point for CTI automation because it transforms free text into operational indicators (actors, malware, tools, IoCs, affected assets, vulnerabilities, and ATT&CK techniques). Earlier CTI pipelines often relied on token-level tagging with classical features or BiLSTM-CRF models, but the reviewed studies show that transformer embeddings substantially improve performance by providing contextual representations of domain-specific terms and abbreviations.

Chang et al. [45] illustrate the industrial CTI NER problem well: CTI contains out-of-vocabulary (OOV) tokens. Their multi-feature approach shows the value of combining character-level cues with contextual representations to reduce OOV brittleness.

Beyond entity tagging, industrial studies increasingly focus on relation and event extraction, as a list of entities alone is insufficient for actionable defense. Mapping vulnerability to the affected component, then the technique, and to the observable indicator requires linking entities across sentences and documents. Work that integrates threat intelligence chains (e.g., DeBERTaIC) demonstrates how adding a structured intermediate representation improves downstream reasoning and attribution [46]. Similarly, large-scale knowledge representations show that extraction quality becomes the bottleneck: poor entity boundaries propagate errors into relation graphs and attack chains.

A second trend is semantic filtering and intelligence fusion. EnhanceCTI employs lightweight transformer variants (e.g., DistilBERT) for relevance filtering and sentence-level embeddings (e.g., SentenceBERT) for merging and consistency scoring across sources and industries, thereby separating “what is relevant” from “how sources agree” [47].

4.1.2. Log and Alert Understanding: Tokenization Choices, Representation, and Temporal Structure

Industrial environments generate massive volumes of semi-structured logs. NLP techniques appear here in two forms: textual representation of logs for detection and schema/field extraction for normalization.

For representation learning, Coote et al. [48] present a classic baseline: TF-IDF applied to log/event text, combined with an LSTM autoencoder. This family of methods is computationally inexpensive and can run near-edge, but it is sensitive to vocabulary drift, does not capture semantics of paraphrased events, and struggles when attackers mimic benign text patterns. In contrast, transformer-based approaches treat logs as sequences with subword tokenization, improving robustness to spelling variants and identifier changes.

Several papers advance log analytics by injecting structure and time. Zhang et al. [49] use an ontology and few-shot prompting for field extraction followed by temporal graph reasoning, reflecting a broader trend: (i) normalize events into structured “triples” or schemas, then (ii) apply temporal modeling to detect anomalous sequences. The key technical distinction is that anomaly detection improves when the model learns event-to-event transitions (temporal dependencies) rather than isolated log lines.

4.1.3. MITRE ATT&CK Integration: Technique Classification and Cross-Taxonomy Alignment

Industrial defenders increasingly treat MITRE ATT&CK (including ICS) as a lingua franca for threat analytics. NLP is used to map unstructured text (CTI, CVEs, alerts) into ATT&CK techniques, enabling standardized reporting, rule generation, and analytics.

Many studies show that embedding-based similarity outperforms simple frequency matching for linking different taxonomies (e.g., CWE or CVE to ATT&CK techniques) because it aligns items by meaning rather than by shared keywords [50]. Kim et al. [51] similarly demonstrate that semantically grounded mapping can recover attack paths and implications of techniques beyond surface overlap.

Technique classification also faces strong label imbalance (many rare techniques) and domain shift across sectors. AC_MAPPER [52] addresses this by combining input augmentation and class rebalancing, thereby improving macro-F1 under imbalance, an important contribution because operational CTI typically over-represents common techniques and under-represents emerging ones. At the platform level, OTuHunt [53] demonstrates how extraction and mapping can be operationalized to generate SIEM-friendly outputs and threat-hunting queries for OT/ICS environments.

4.1.4. LLM-Centric Methods: In-Context Learning, RAG, and Agentic Workflows

Recent industrial studies experiment with LLMs as flexible reasoning layers for detection, triage, and interaction. Preliminary evidence suggests LLMs can improve contextual interpretation, but they raise compute, latency, and validation concerns.

Ann et al. [54] and Jin et al. [55] explore LLM-assisted intrusion detection and analysis for ICS traffic and events. Compared with fixed classifiers, LLMs offer (i) rapid adaptation via in-context learning and (ii) natural-language explanations; however, they require careful prompt design, robust grounding, and clear operational constraints to avoid hallucination and unsafe recommendations.

A particularly relevant direction for industrial realism is the use of LLM-enabled interaction systems, such as honeypots. Chamotra et al. [56] combine finite-state protocol modeling (for correctness) with retrieval-augmented LLM responses (for flexibility), showing how hybrid designs mitigate the main weakness of pure LLM approaches (unreliable protocol state) while retaining adaptability.

4.1.5. Supporting Techniques and Complementary Industrial NLP Approaches

In addition to end-to-end CTI extraction and intrusion detection pipelines, several studies support NLP techniques that strengthen industrial cybersecurity workflows by improving semantic alignment, benchmarking, and model governance. Hybrid transformer–recurrent architectures have been applied to vulnerability classification, showing that contextual language representations (BERT) combined with sequential modeling (LSTM) can improve robustness when vulnerability descriptions are noisy or weakly structured [57]. Other work focuses on bridging heterogeneous security knowledge by connecting attack patterns to weakness taxonomies, improving traceability and downstream analytics in industrial reporting and threat modeling pipelines [58]. Complementing model development, dataset- and benchmark-oriented research proposes evaluation frameworks for IDS/IPS datasets that explicitly integrate MITRE ATT&CK relevance and industry-oriented metrics, addressing a key limitation of accuracy-only comparisons in operational environments [59]. NLP-based approaches are also used to support explainable anomaly and traffic detection in Industrial Control System (ICS) environments by integrating machine learning models with interpretability techniques to enhance transparency and operator trust [60,61]. Industrial control security surveys further emphasize the growing role of knowledge graphs as a semantic backbone for scalable reasoning and decision support in OT/ICS contexts [62]. Finally, emerging work suggests that prompting and LLM-driven reasoning can be applied beyond text analytics (e.g., to specification analysis and verification tasks), indicating a broader trajectory toward language-centered tooling across industrial assurance workflows [63]. Table 3 provides a structured overview of the reviewed industrial-system literature, illustrating how different NLP tasks and training strategies align with industrial security objectives and reflect the field’s methodological shift toward transformer- and LLM-based approaches.

Table 3.

Summary of NLP and LLM-based methods for industrial cybersecurity (Section 4.1). The table maps representative works to industrial security tasks, NLP task types, training strategies (TS), and language models used. Industrial security tasks include Behavior and Attack Analysis (BAA), Anomaly Detection (AD), Intrusion Detection (ID), and LLM Safety (LS). NLP task types include Named Entity Recognition (NER), Relation Extraction (RE), Semantic Similarity (SS), Text Classification (TC), Data Augmentation (DA), Information Extraction (IE), and Natural-Language Reasoning (R). Training strategy (TS) indicates whether models are fine-tuned (F), prompt-based (P), or not applicable (-). Filled circles (●) denote that a work explicitly addresses the corresponding industrial security task.

Across Industrial Systems, the literature indicates that the most robust pipelines are hybrid: transformer-based extraction and classification augmented with domain ontologies/knowledge, temporal modeling, and increasingly retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) or LLM components for reasoning and explanation.

The main technical trade-offs are (i) accuracy vs. deployability (edge constraints), (ii) semantic richness vs. auditability, and (iii) adaptability vs. safety assurance.

4.2. Critical Infrastructure Protection

Critical infrastructure protection (CIP) differs from general enterprise security because it is constrained by safety requirements, legacy OT assets, regulatory obligations, and the need for explainable decision-making under uncertainty. NLP is used in CIP primarily for compliance and standards reasoning, cross-source correlation and situational awareness, and knowledge graph construction.

A growing set of studies uses NLP/LLMs to interpret standards and translate them into actionable controls and recommendations. Mpatziakas et al. [64] propose an LLM-based advisory assistant that helps operators navigate cybersecurity standards in Industry 4.0 contexts. The novelty here is not merely text summarization; it is the mapping between normative requirements and operational mitigation actions.

CIP often requires correlating security data across heterogeneous sources (incident tickets, alerts, CTI reports, asset inventories, and policy documents). Settanni et al. [65] provide early foundational methods for correlating cyber incident information to support situational awareness. Although it is not transformer-based, the core challenge it addresses remains central: correlation is difficult when signals are sparse, noisy, and distributed across systems.

Chen et al. [31] apply a large-scale CIP knowledge graph built from regulations and standards using a BiLSTM-CRF model combined with a domain-specific BERT. Methodologically, this illustrates a pipeline with three stages: ontology design, information extraction, and relation prediction. A key advantage is auditability: each edge and node can be traced to extracted evidence. However, this also exposes a core weakness: extraction errors directly distort downstream risk reasoning.

Several complementary studies extend CIP-focused NLP beyond core compliance and knowledge graph pipelines [62,66]. Information-retrieval-based approaches leverage NLP to safeguard infrastructure by enabling efficient discovery and correlation of threat-relevant documents across large repositories [67]. Deep-learning-based threat detection methods for IIoT environments provide additional empirical evidence that infrastructure-scale protection benefits from combining network telemetry with semantic analysis [59,68]. Broader AI governance and trustworthiness studies in robotics and autonomous systems further reinforce the importance of explainability, accountability, and human oversight when deploying advanced NLP and LLM techniques in safety-critical infrastructure contexts [69].

4.3. Power and Energy Systems

Selim et al. [70] show how LLMs can be applied to interpret control-command text (e.g., Volt/VAR commands) for cyberattack detection. The technical significance is that the model is not merely classifying network packets; it interprets operator-meaningful command sequences. Compared with numeric anomaly detectors, language-based approaches can exploit the semantics of command intent (e.g., plausible vs. malicious control objectives).

Digital substations introduce the zero-day problem in IEC 61850 [71]. Manzoor et al. [72] use in-context learning to adapt to novel attacks with few examples, which is particularly attractive when labeled attack data is scarce. However, in-context learning performance is sensitive to prompt composition and demonstration selection. This implies that operational deployment should include prompt governance, evaluation of drifted conditions, and defensive prompting strategies.

Complementary work emphasizes domain extraction and rule creation. Yang et al. [73] use RoBERTa with a Bi-GRU and CRF for entity recognition to enhance situation awareness in power systems, thereby supporting downstream tasks such as IDS rule generation and structured reporting.

Grid operations increasingly require synthesizing electrical measurements with contextual data (weather, operator notes, social signals). Shen et al. [74] propose a security situational awareness framework that converts multimodal signals into structured text prompts for LLM processing. The methodological move here is crucial: rather than building a monolithic multimodal model, the system serializes diverse signals into a language representation. This can accelerate prototyping, but it also raises questions about information loss and prompt brittleness.

Zaboli et al. [75] extend multimodal reasoning through a framework for anomaly detection in energy management systems (EMS). Compared with single-modality detectors, multimodal systems can cross-validate anomalies (e.g., a control action that is numerically plausible but operationally suspicious). The trade-off is complexity: more modalities increase integration overhead and may introduce new failure modes if any modality becomes unreliable.

Explainability is especially important in power systems because operators must justify interventions. Sharshar et al. [76] integrate lightweight ML detection (e.g., LightGBM) with LLM-generated natural language explanations. This hybrid design highlights a recurring pattern across high-stakes settings: use a fast, validated detector for decision-making, and an LLM for explanation and operator support. The advantage is latency and reliability; the risk is that explanations may be persuasive but not faithful unless grounded in model evidence.

Related efforts apply generative models for forecasting-based anomaly detection in microgrids and measurement systems [77]. GPT-style modeling has been adapted for time-series forecasting and False Data Injection Attacks (FDIA) detection by comparing predicted vs. observed values. Unlike language-only tasks, this approach uses “generative pretraining” ideas to model nonlinear temporal dynamics.

Renewable infrastructures introduce distributed assets and data governance challenges. Bandara et al. [78,79] combine Llama-based models with blockchain and federated learning ideas for wind energy security, illustrating an architectural trend: distribute learning and governance while using LLMs for high-level reasoning or script generation.

At the edge/cloud boundary, Internet-of-Energy work often adopts two-tier designs. Reference [80] proposes a lightweight edge model (MiniLM-scale) for local alerting and a larger cloud LLM for forensic analysis and rule generation (e.g., Snort). Fu et al. [81] similarly use federated RAG to improve log analysis and threat detection. Sunxuan et al. [82] address resource allocation and fine-tuning delay constraints, reflecting the practical reality that security ML competes with other operational workloads.

In addition to the representative studies discussed above, several power-system-specific works examine the use of LLMs in smart grids from both opportunities and risks perspectives, including ChatGPT 4.0-style analyses and broader discussions of LLM applications and risks in smart-grid settings [83,84]. Other studies demonstrate hybrid “language and control/optimization” patterns, for example using LLM-aware or LLM-assisted approaches in adaptive distribution voltage regulation under operational constraints [85]. Complementary detection research also explores lower-level telemetry pathways, such as packet-payload anomaly detection designed for cyber-physical power systems, which can be paired with higher-level semantic reasoning for layered defense [86]. Beyond detection, semantic and knowledge-driven approaches support grid security operations through ontology-based reasoning of security contexts and infrastructure-scale semantic search capabilities that enhance the discovery and correlation of grid models and security-relevant artifacts [87,88]. Finally, recent work explores federated learning and LLM hybrid security frameworks, as well as real-time threat prediction/response for the Internet of Energy, aligning with the broader shift toward distributed and adaptive security intelligence in power systems [89,90]. Related distributed-energy security studies also highlight the feasibility of edge-deployable agents for tactic/technique attribution in microgrid environments, a capability that is increasingly relevant as grids decentralize [91].

Power and energy studies demonstrate three distinct NLP/LLM roles: (i) interpreting commands and protocol text, (ii) converting multimodal grid context into language for reasoning, and (iii) providing explainable narratives on top of fast detectors. The dominant open problems are rigorous validation under distribution shift, real-time constraints, and ensuring explanation faithfulness and operational safety.

4.4. Industrial Internet of Things

SecurityBERT [92] represents a central design pattern: a BERT-style encoder adapted for resource-constrained deployment through (i) byte-level tokenization to improve robustness to non-standard payloads and identifiers, and (ii) privacy-preserving fixed-length encodings to limit data leakage. This contrasts with classical IDS pipelines that rely on manual features or n-gram statistics, which often underperform in the face of protocol variability and obfuscation.

Ali et al. [93] similarly use BERT for representation learning, combining it with an MLP classifier and methods for handling imbalance. Compared with end-to-end fine-tuning of large models, this approach can reduce training complexity and facilitate deployment. Diwan et al. [94] provide a broader analysis of attack categories and emphasize that practical IIoT security requires multilayered strategies that extend beyond model performance. Breve et al. [95] propose a BERT-based model that checks the semantic consistency of IoT/automation rules by detecting contradictions and logically incompatible conditions within natural-language or structured policy specifications.

Healthcare IoT introduces regulatory constraints and safety-critical operations. Rajamäki [96] analyzes Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) risks and tool mapping within the DYNAMO project context, underscoring gaps in interoperability and real-time monitoring.

IIoT datasets are frequently imbalanced, and rare attacks are operationally important. Melícias et al. [97] compare GPT-based and interpolation-based augmentation methods with synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE) variants, highlighting an important nuance: augmentation benefits depend on the classifier family and the geometry of the feature space. Deep models may benefit from richer synthetic diversity, whereas tree-based methods sometimes gain less.

Explainability is essential for actionable IIoT defenses, especially when false positives can disrupt production. Khandan et al. [98] combine fusion-based detection with explainable outputs and LLM-assisted mitigation guidance grounded in MITRE D3FEND. Compared with “black-box IDS” designs, this line of work treats the IDS as a socio-technical tool in which operator trust and response quality are part of the performance targets. Liu, Li, and Hulayyil [99] employ pretrained language models to intelligently detect and classify cyber attack patterns in Industrial Internet of Things environments, demonstrating the effectiveness of transfer learning-based NLP approaches for pattern recognition and threat identification across heterogeneous IIoT networks. Cimino and Deufemia [100] present SIGFRID, an unsupervised and platform-agnostic approach for detecting interference and anomalies in Industrial Internet of Things automation rules, enabling threat detection without labeled data or dependency on proprietary IoT platforms.

Distributed IIoT deployments introduce privacy and governance constraints. Deng et al. [101] propose leakage-resilient, differentially private aggregation mechanisms that reduce communication costs while defending against reconstruction attacks, thereby directly addressing a primary barrier to collaborative learning in critical infrastructure contexts.

Security and data management methods complement model-level privacy. Mao et al. [102] present a searchable encryption scheme that supports dynamic data management for IIoT, reflecting that secure analytics often requires secure storage and query mechanisms. Blockchain-enabled authentication is also explored: Xie et al. [103] introduce cross-domain anonymous authentication with traceability, enabling secure identity management across organizational boundaries.

Beyond implementation-focused intrusion detection systems, several studies provide survey-level and cross-domain perspectives on IIoT security, highlighting systemic vulnerabilities, dataset limitations, and evaluation challenges that are not always visible in model-centric studies [104]. Recent reviews further examine the emerging role of large language models in IoT security, synthesizing advances in representation learning, contextual reasoning, and natural-language interfaces while also identifying open challenges related to scalability, trustworthiness, and deployment constraints [105,106].

Complementary research extends IIoT security analysis to adjacent communication-centric domains, demonstrating that language-model-based techniques can generalize beyond traditional industrial networks. For example, pre-trained LLMs have been applied to cyber threat detection in satellite networks, while BERT-based intrusion detection methods have been explored for vehicular and wireless environments, indicating methodological overlap with IIoT security despite differing threat surfaces [107,108].

Taken together, these studies reinforce the need to evaluate IIoT security solutions not only in isolation, but also in relation to broader networked and cyber-physical ecosystems, where lessons learned from satellite, vehicular, and wireless domains can inform more robust and transferable NLP-driven defense strategies [104,105].

4.5. Electric Vehicles and Emerging Domains

Electric Vehicle (EV) charging systems combine time-series signals (state-of-charge trajectories, power draw) with transactional and operational context (session metadata, pricing, user behavior). As a result, EV studies often adopt multimodal or hybrid designs.

Honnalli et al. [109] integrate sequential forecasting (LSTM) with LLM-based interpretation of generated plots through structured prompts. This approach illustrates a broader NLP technique: language models as interpreters of derived representations (e.g., summaries or plots) rather than raw sensor streams. The advantage is rapid prototyping and human-aligned explanations; the risk is that model performance may depend on visualization conventions and prompt design.

Honnalli et al. [110] extend this by using RAG to ground LLM decisions in domain knowledge, thereby reducing hallucination and improving consistency in novel situations. Compared with pure ML detectors trained on fixed feature sets, RAG-enabled LLM pipelines can adapt to evolving policies, threat reports, and infrastructure conditions by updating the retrieval corpus rather than retraining the entire model.

Security for autonomous systems and CPS requires integrating discrete logic, continuous dynamics, and adversarial behavior. Andreoni et al. [111] surveys generative AI for autonomous security and resilience. For formal CPS analysis, classical modeling approaches (e.g., timed automata, transition systems) remain relevant for safety verification and attack-impact reasoning [112,113,114].

Beyond EV-charging-specific pipelines, several emerging studies investigate LLM-powered threat intelligence for electric-vehicle cyber-physical systems, emphasizing proactive detection of novel/zero-day behaviors and the role of language-based reasoning in synthesizing signals, reports, and contextual evidence [115]. Parallel work in vehicular ecosystems addresses collaborative threat sharing under privacy constraints, showing that large-scale vehicular defense requires incentive-compatible and privacy-preserving mechanisms for exchanging threat indicators across stakeholders [116].

A key recent NLP trend is converting non-text structures into text to leverage LLM embeddings. Fragkos et al. [117] introduce GraphLLM-CPS, converting graph representations of Cyber-physical systems (CPS) data into textual formats to learn node embeddings for anomaly detection. This textualization strategy parallels multimodal grid approaches: it trades modality-specific modeling for leveraging LLM priors, which can be effective but requires careful evaluation to avoid information loss.

4.6. Summary

Across industrial manufacturing, power and energy systems, IIoT platforms, and emerging cyber–physical domains, the literature reveals a consistent shift from reactive, detection-centric cybersecurity toward context-aware, intelligence-driven defence enabled by NLP. Early approaches focused on basic extraction and classification, whereas recent transformer-based and LLM-centric methods support semantic fusion, threat reasoning, explainability, and early warning. Despite this methodological convergence, domain-specific constraints remain decisive: industrial environments emphasise deployability across heterogeneous IT/OT systems, power and energy platforms prioritise interpretability and human-in-the-loop decision-making in safety-critical contexts, and IIoT deployments require scalable, privacy-aware solutions for resource-constrained devices. Emerging domains further explore multimodal and language-centric representations to enable anticipatory security. Overall, the results indicate that while language-based models are increasingly central to cybersecurity across platforms, their operational roles, risks, and maturity remain strongly shaped by domain-specific requirements.

Table 4 presents representative examples of how different NLP paradigms are applied to specific cybersecurity task roles across industrial domains, rather than serving as an exhaustive review of the literature. The table highlights both the functional capabilities and practical trade-offs of each methodological era. Sparse/Lexical methods rely on keyword matching, frequency statistics, and rule-based representations, offering high interpretability, low computational overhead, and ease of deployment, which makes them attractive in resource-constrained industrial environments; however, they are highly sensitive to vocabulary drift, limited semantic expressiveness, and poor cross-domain generalization. RNN-based methods model sequential and temporal dependencies, enabling improved contextual understanding and event or relation extraction, but they typically require labelled data, exhibit limited transferability across domains, and are affected by domain shift between IT and OT contexts. LLM-centric methods leverage large pre-trained language models, prompting strategies, and retrieval-augmented reasoning to support semantic fusion, multilingual processing, explanation, and higher-level threat interpretation; at the same time, their adoption in industrial CTI is challenged by fine-tuning cost, hallucination risk, data confidentiality concerns, and deployment constraints in safety-critical systems. The task tags illustrate how each paradigm expands the functional scope of NLP, reflecting a shift from operationally lightweight information extraction toward reasoning-driven and decision-support capabilities that underpin anticipatory cybersecurity.

Table 4.

CTI-Focused NLP/ML Methods with Task-Level Tags. Task tags: NER = Named Entity Recognition · RE = Relation/Event Extraction · CLS = Classification · MAP = ATT&CK/taxonomy mapping · RET = Retrieval/RAG · REAS = Reasoning/explanation.

5. Challenges and Research Gaps

The literature indicates a growing dependence on NLP techniques for CTI extraction, threat reasoning, and predictive defence in digital manufacturing systems. However, several gaps persist. First, data scarcity and representativeness limit scalability, as many datasets used to train models do not accurately reflect real industrial system behaviour or multi-stage adversarial campaigns. Second, interpretability and transparency remain underdeveloped, particularly as Transformer architectures become increasingly complex, making it difficult for analysts to interpret model outputs in mission-critical environments. Third, scalability and deployment feasibility pose challenges, as many deep learning frameworks require computational resources that are not always available on IIoT or control-system nodes.

In addition to the identified gaps in data availability, interpretability, and scalability, a further research gap concerns the use of social media and open-source communication platforms as early-warning channels for Industry 4.0 environments. Although several studies demonstrate that social media can reveal emerging exploit discussions and vulnerability awareness earlier than formal advisories, these approaches have been applied primarily in general enterprise IT contexts rather than in ICS, SCADA, IIoT, or cyber–physical production systems. Industrial environments exhibit unique operational semantics, device behaviours, and threat patterns that are not directly reflected in mainstream security discourse on social platforms, resulting in early cyberattack signals relevant to Industry 4.0 remaining largely undetected by current NLP-based monitoring systems. Additionally, the mapping of open-source intelligence signals to structured threat-behaviour taxonomies, such as MITRE ATT&CK for ICS or Enterprise, remains limited. Current studies mostly centre on keyword identification or vulnerability mentions rather than contextualization within tactics, techniques, pre-attack behaviours, or kill-chain progression. In the absence of ATT&CK-aligned predictive interpretation, industry practitioners perceive a reduced operational usefulness of social media intelligence. Therefore, constructing domain-aware social media analytics pipelines capable of detecting subtle yet meaningful threat cues and translating them into ATT&CK-based warnings is an important yet underexplored research direction.

Such gaps highlight the need for domain-adaptable, explainable, and resource-aware NLP frameworks specifically designed for cyber–physical and industrial infrastructures.

6. Future Research Directions

In future work, it would be beneficial to develop multimodal threat intelligence ecosystems that integrate text-based CTI with complementary modalities, such as network telemetry, sensor data, and visual process models. The development of domain-specific language models adapted for the manufacturing and ICS corpus will be key to improving contextual understanding of industrial terminology and attack patterns. Transfer learning and federated or privacy-preserving learning methods can be leveraged to address data scarcity and concerns about data confidentiality through cross-organizational collaboration, without requiring the sharing of sensitive data. Additionally, the development of lightweight, edge-deployable NLP architectures will improve the scalability of real-time inference systems in industrial environments. Research should also address human-AI collaboration frameworks, in which analysts validate and provide guidance on NLP inferences, enabling a combination of automation and human judgment to improve the reliability of the decision-making process. In addition to accuracy, future systems need to address explainability and transparency, using interpretable attention maps or symbolic reasoning layers to ensure accountability in safety-critical industries. Research into multilingualism and cross-domain adaptation is also necessary to enable CTI systems to understand the global threat intelligence available in all regional languages and sectors, given that predictive cyber defense should itself advance in tandem with the increasingly global, transnational shape of Industry 4.0 systems.

7. Discussion

A synthesis of the available literature shows that NLP-based frameworks have evolved from simple entity extraction to sophisticated graph-reasoning and LLM-assisted systems for predictive analysis. Comparative analysis reveals that transformer-based and knowledge-integrated models achieve high contextual precision at high levels of automation but are not implementable in industrial environments due to data heterogeneity and domain transfer issues, including scalability constraints. The use of NLP and DL in predictive CTI represents a paradigm shift toward anticipatory cyber defense; however, practical implementations remain limited to research prototypes and pilots in a few organizations. For academia, these results underline the need for more integrated collaboration between linguistics, cybersecurity engineering, and industrial informatics. For the industry, the implications include restructuring SOC operations and adopting adaptive, machine-assisted pipelines for threat analysis. Standards for data sharing and model validation, as well as ethical AI-based cybersecurity automation, should be a concern for policymakers. Indeed, while NLP has been redefining the scope of cyber threat analysis and early prediction, in real-world scenarios, governance, interpretability, and human-in-the-loop integration are the factors that translate technical novelty into actual impact.

8. Conclusions

This review proves how NLP can contribute to the proactive transformation of cybersecurity in manufacturing by enabling detection, interpretation, and anticipation of emerging threats. Through a systematic analysis of state-of-the-art frameworks, this study examines how NLP-driven CTI, augmented with machine learning and large language models, can address the gap between unstructured threat data and actionable intelligence. Within Industry 4.0, Cyber–Physical Systems integrate IoT, SCADA, and ICS infrastructures, enabling the use of Predictive NLP models that can deliver significant advantages, such as reducing response times and improving situational awareness and support for resilient operations. However, for this to be realized, data quality, explainability, and domain-adaptation challenges must be addressed. Multimodal analytics, domain-specific models, and human–AI teaming are the way forward. The cybersecurity role of NLP would go beyond being just descriptive to being transformative by enabling a move from reactive defense to intelligent, predictive, adaptive protection of digitally integrated factories of the future.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16020619/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, and writing, original draft preparation were carried out by M.A. and S.J. Supervision, advisory support, refinement of research direction, and writing, review and editing were provided by S.J. and K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors show their appreciation to colleagues and peers who provided insights and feedback during the development of this review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ross, P.; Maynard, K. Towards a 4th industrial revolution. Intell. Build. Int. 2021, 13, 159–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuptuk, N.; Hailes, S. Security of smart manufacturing systems. J. Manuf. Syst. 2018, 47, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukwandu, E.; Hewage, C.; Hindy, H. Editorial: Cyber security in the wake of fourth industrial revolution: Opportunities and challenges. Front. Big Data 2024, 7, 1369159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, F.; Balduzzi, M.; Vosseler, R.; Rösler, M.; Quadrini, W.; Tavola, G.; Pogliani, M.; Quarta, D.; Zanero, S. Smart factory security: A case study on a modular smart manufacturing system. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 180, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stănculescu, M.S. A case study of an industrial power plant under cyberattack. Energies 2021, 14, 2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S.; Pearce, H.; Yampolskiy, M.; Oromiehie, E.; Prusty, B.G. On cyber sabotage risks in automated manufacturing of composites. J. Manuf. Syst. 2025, 77, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Guardian. Cyber-Attack Cost Marks and Spencer Lost Sales, Company Results Reveal. 21 May 2025. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2025/may/21/cyber-attack-cost-marks-and-spencer-lost-sales-company-results-reveal (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Reuters. M&S Says Cyber Hackers Broke Through Third-Party Contractor. 21 May 2025. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/ms-says-cyber-hackers-broke-through-third-party-contractor-2025-05-21/ (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Reuters. Britain’s JLR Hit by Cyber Incident That Disrupts Production, Sales. 2 September 2025. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/britains-jlr-hit-by-cyber-incident-that-disrupts-production-sales-2025-09-02/ (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Upadhyay, D.; Sampalli, S. SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) systems: Vulnerability assessment and security recommendations. Comput. Secur. 2020, 89, 101666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.; Badger, L.; Waltermire, D.; Snyder, J.; Skorupka, C. Guide to Cyber Threat. NIST Special Publication, 2016. pp. 1–5. Available online: https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/5218969/Department-of-Commerce-U-S-NIST-Special.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Alaeifar, P.; Pal, S.; Jadidi, Z.; Hussain, M.; Foo, E. Current approaches and future directions for cyber threat intelligence sharing: A survey. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2024, 83, 103786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zibak, A.; Sauerwein, C.; Simpson, A.C. Threat Intelligence Quality Dimensions for Research and Practice. Digit. Threat. Res. Pract. 2022, 3, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palo Alto Networks. What Is Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI)? Cyberpedia, 2019. Available online: https://www.paloaltonetworks.com/cyberpedia/what-is-cyberthreat-intelligence-cti (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Recorded Future. What are the 6 Phases of the Threat Intelligence Lifecycle? Threat Intelligence Blog, 5 February 2024. Available online: https://www.recordedfuture.com/blog/threat-intelligence-lifecycle-phases (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Montasari, R.; Carroll, F.; Macdonald, S.; Jahankhani, H.; Hosseinian-Far, A.; Daneshkhah, A. Application of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Producing Actionable Cyber Threat Intelligence. In Digital Forensic Investigation of Internet of Things (IoT) Devices; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Jurafsky, D.; Martin, J.H. Speech and Language Processing: An Introduction to Natural Language Processing, Computational Linguistics, and Speech Recognition, 3rd ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. Syntactic Structures; Mouton: New York City, NY, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein, J. Introduction to Natural Language Processing; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Convolutional Neural Networks for Sentence Classification. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Doha, Qatar, 25–29 October 2014; pp. 1746–1751. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins, W.J. The Georgetown-IBM Experiment Demonstrated in January 1954. In Machine Translation: From Real Users to Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 102–114. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, P.F.; Pietra, V.J.; Della Pietra, S.A.; Della Mercer, R.L. The Mathematics of Statistical Machine Translation: Parameter Estimation. Comput. Linguist. 1993, 19, 263–311. [Google Scholar]

- Biber, D.; Conrad, S.; Reppen, R. Corpus Linguistics: Investigating Language Structure and Use; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Collobert, R.; Weston, J.; Bottou, L.; Karlen, M.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Kuksa, P. Natural Language Processing (Almost) from Scratch. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2493–2537. [Google Scholar]

- Mikolov, T.; Chen, K.; Corrado, G.; Dean, J. Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1301.3781v3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (NAACL-HLT), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, K.S. Natural language processing: A historical review. In Current Issues in Computational Linguistics: In Honour of Don Walker; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1994; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. Roberta: A robustly optimized bert pretraining approach. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.11692. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, F.; Qin, J. A management knowledge graph approach for critical infrastructure protection: Ontology design, information extraction and relation prediction. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. Prot. 2023, 43, 100634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudhaibi, A.; Albarrak, M.; Aloseel, A.; Jagtap, S.; Salonitis, K. Predicting Cybersecurity Threats in Critical Infrastructure for Industry 4.0: A Proactive Approach Based on Attacker Motivations. Sensors 2023, 23, 4539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monostori, L.; Kádár, B.; Bauernhansl, T.; Kondoh, S.; Kumara, S.; Reinhart, G.; Sauer, O.; Schuh, G.; Sihn, W.; Ueda, K. Cyber-physical systems in manufacturing. Cirp Ann. 2016, 65, 621–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 62443-1-1:2009; Security for Industrial Automation and Control Systems: Models and Concepts. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- IEC 62443-1-2; Security for Industrial Automation and Control Systems: Master Glossary of Terms and Abbreviations. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. Available online: https://syc-se.iec.ch/deliveries/cybersecurity-guidelines/security-standards-and-best-practices/iec-62443/ (accessed on 12 August 2024).

- IEC 62443-1-3; Security for Industrial Automation and Control Systems: Cyber Security System Conformance Metrics. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. Available online: https://www.iec.ch/dyn/www/f?p=103:38:417212030183982::::FSP_ORG_ID,FSP_APEX_PAGE,FSP_PROJECT_ID:1250,20,18900 (accessed on 12 August 2024).

- IEC 62443-2-1; Industrial Communication Networks—Network and System Security—Part 2-1: Establishing an IACS Security Program. International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- IEC 62443-3-3; Industrial Communication Networks—Network and System Security—Part 3-3: System Security Requirements and Security Levels. International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Ross, R.; Pillitteri, V.; Graubart, R.; Bodeau, D.; McQuaid, R. Developing Cyber Resilient Systems: A Systems Security Engineering Approach; No. NIST Special Publication (SP) 800-160 Vol. 2 (Draft); National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Büthe, T. Engineering uncontestedness? The origins and institutional development of the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). Bus. Politics 2010, 12, 1–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylde, V.; Rawindaran, N.; Lawrence, J.; Balasubramanian, R.; Prakash, E.; Jayal, A.; Khan, I.; Hewage, C.; Platts, J. Cybersecurity, data privacy and blockchain: A review. SN Comput. Sci. 2022, 3, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ani, U.P.D.; He, H.; Tiwari, A. Review of cybersecurity issues in industrial critical infrastructure: Manufacturing in perspective. J. Cyber Secur. Technol. 2017, 1, 32–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering, Version 2.3; EBSE Technical Report EBSE-2007-01; Software Engineering Group, School of Computer Science and Mathematics, Keele University: Keele, UK; Department of Computer Science, University of Durham: Durham, UK, 9 July 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhu, P.; He, J.; Kong, L. Research on Unified Cyber Threat Intelligence Entity Recognition Method Based on Multiple Features. In Proceedings of the 2023 4th International Conference on Computers and Artificial Intelligence Technology (CAIT), Macau, China, 13–15 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, K.; Tang, W.; Tan, L.; Yang, J. DeBERTaIC: A Framework for Cyber Threat Analysis Integrating DeBERTa Model and Attack Intelligence Chain. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2025, 71, 7756–7770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-S.; Pai, T.-W.; Sun, C.-Y. EnhanceCTI: Enhanced semantic filtering and feature extraction framework for industry-specific cyber threat intelligence. Comput. Secur. 2025, 158, 104649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coote, E.; Lachine, B. Platform Management System Host-Based Anomaly Detection using TF-IDF and an LSTM Autoencoder. In Proceedings of the MILCOM 2023—2023 IEEE Military Communications Conference (MILCOM), Boston, MA, USA, 30 October–3 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Su, X. Threat Detection Framework Based on Industrial Internet of Things Logs. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 195642–195657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva-Miranda, I.; Akbar, M. Analyzing Threat Vectors in ICS Cyberattacks. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData), Sorrento, Italy, 15–18 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.-Y.; Yoon, S.-S.; Euom, I.-C. V2TSA: Analysis of Vulnerability to Attack Techniques Using a Semantic Approach. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 166742–166760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarrak, M.; Alqudhaibi, A.; Jagtap, S. AC_MAPPER: A robust approach to ATT&CK technique classification using input augmentation and class rebalancing. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2025, 24, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaliwat, F.; Alqahtani, L.; Alzahrani, M.; Alamoudi, N.; Hakami, S.; Alharby, A.; Alharbi, N. OTuHunt: An Aggregated Threat Hunting & Intelligence Platform for OT/ICS Environment and MSSP Services. In Proceedings of the 2025 12th International Conference on Information Technology (ICIT), Amman, Jordan, 27–30 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ann, S.; Cho, S.-J.; Kim, H. A Preliminary Study on an Intrusion Detection Method using Large Language Models in Industrial Control Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 Fifteenth International Conference on Ubiquitous and Future Networks (ICUFN), Budapest, Hungary, 2–5 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Z.; Zhao, J.; Li, W.; Sheng, C.; Sun, T.; Lv, F. An Integrated Approach to Enhancing Equipment Anomaly Detection Efficiency in Large Language Models Using Multiple Machine Learning Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2025 5th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Industrial Technology Applications (AIITA), Xi’an, China, 28–30 March 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chamotra, S.; Barbhuiya, F.A. Advancing Industrial Honeypots: FSM and LLM Integration for Realistic ICS Protocol Emulation. IEEE Trans. Industr. Inform. 2025; Early Access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marali, M.; Dhanalakshmi, R.; Rajagopalan, N. A hybrid transformer-based BERT and LSTM approach for vulnerability classification problems. Int. J. Math. Oper. Res. 2024, 28, 275–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhan, A.; Rahman, M.; Akbar, M.; Hossain, M.S. AWEB to Bridge Cybersecurity Attack Patterns and Weaknesses. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData), Washington, DC, USA, 15–18 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tory, A.R.; Hasan, K.F. An evaluation framework for network IDS/IPS datasets: Leveraging MITRE ATT&CK and industry relevance metrics. Comput. Secur. 2025, 161, 104777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liu, Y.; Qin, Z.; Dong, F. A transformer-enhanced LSTM framework for robust malicious traffic detection in industrial control systems. Knowl. Based Syst. 2025, 321, 113725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, N.X.; Hoang, N.V.; Du, N.H.; Huong, T.T.; Tran, K.P. Explainable Anomaly Detection for Industrial Control System Cybersecurity. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 1183–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Xu, P.; Wang, K.; Naqvi, S.S.A. Overview of the Application of Knowledge Graph in Industrial Control Security Field. In Proceedings of the 2025 44th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Chongqing, China, 28–30 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wray, T.; Wang, Y. 5G Specifications Formal Verification with Over-the-Air Validation: Prompting is All You Need. In Proceedings of the MILCOM 2024—2024 IEEE Military Communications Conference (MILCOM), Washington, DC, USA, 28 October–1 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mpatziakas, A.; Schoinas, I.; Lalas, A.; Drosou, A.; Chatzidiamantis, N.; Tzovaras, D. Deciphering Standards for cybersecurity in Industry 40: Advisory AIfor Cybersecure IIoT. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Cyber Security and Resilience (CSR), Chania, Greece, 4–6 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Settanni, G.; Shovgenya, Y.; Skopik, F.; Graf, R.; Wurzenberger, M.; Fiedler, R. Correlating cyber incident information to establish situational awareness in Critical Infrastructures. In Proceedings of the 2016 14th Annual Conference on Privacy, Security and Trust (PST), Auckland, New Zealand, 12–14 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, C.; Lan, S.; Fei, W.; Wang, L.; Huang, G.Q.; Zhu, L. Towards Industrial Foundation Models: Framework, Key Issues and Potential Applications. In Proceedings of the 2024 27th International Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design (CSCWD), Tianjin, China, 8–10 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Salley, C.J.; Mohammadi, N.; Taylor, J.E. Safeguarding Infrastructure from Cyber Threats with NLP-Based Information Retrieval. In Proceedings of the 2023 Winter Simulation Conference (WSC), San Antonio, TX, USA, 10–13 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, K.; Tan, L.; Mumtaz, S.; Al-Rubaye, S.; Al-Dulaimi, A.; Bashir, A.K.; Khan, F.A. Securing Critical Infrastructures: Deep-Learning-Based Threat Detection in IIoT. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2021, 59, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Gray, J.; Cangelosi, A.; Meng, Q.; McGinnity, T.M.; Mehnen, J. The Challenges and Opportunities of Artificial Intelligence for Trustworthy Robots and Autonomous Systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Conference on Intelligent Robotic and Control Engineering (IRCE), Oxford, UK, 10–12 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Selim, A.; Zhao, J.; Yang, B. Large Language Model for Smart Inverter Cyber-Attack Detection via Textual Analysis of Volt/VAR Commands. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2024, 15, 6179–6182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 61850; Communication Networks and Systems for Power Utility Automation. International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Manzoor, F.; Khattar, V.; Liu, C.-C.; Jin, M. Zero-day Attack Detection in Digital Substations using In-Context Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Communications, Control, and Computing Technologies for Smart Grids (SmartGridComm), Venice, Italy, 17–20 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Niu, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhang, S.; Deng, X.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Liu, Y. A Cybersecurity Entity Recognition Method for Enhancing Situation Awareness in Power Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 4th New Energy and Energy Storage System Control Summit Forum (NEESSC), Hohhot, China, 29–31 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, B.; Li, Q.; Chen, B.; Li, Z. Large Language Model-Based Security Situation Awareness for Smart Grid: Framework and Approaches. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 173600–173613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaboli, A.; Hong, J.; Ştefanov, A.; Liu, C.C.; Hwang, C.S. Large Language Models for Power System Security: A Novel Multi-Modal Approach for Anomaly Detection in Energy Management Systems. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 203558–203585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharshar, M.; Saber, A.M.; Svetinovic, D.; Youssef, A.M.; Kundur, D.; El-Saadany, E.F. Large Language Model-Based Framework for Explainable Cyberattack Detection in Automatic Generation Control Systems. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Electrical Power and Energy Conference (EPEC), Waterloo, ON, Canada, 15–17 October 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Alankrita Pati, A.; Adhikary, N. Generative Pretraining Transformer Based False Data Injection Attack Detection Framework for DC Microgrid Under Uncertain Operating Condition. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE North-East India International Energy Conversion Conference and Exhibition (NE-IECCE), Silchar, India, 4–6 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bandara, E.; Bouk, S.H.; Shetty, S.; Gore, R.; Kompella, S.; Mukkamala, R.; Rahman, A.; Foytik, P.; Liang, X.; Keong, N.W.; et al. Bassa-Llama—Fine-Tuned Meta’s Llama LLM, Blockchain and NFT Enabled Real-Time Network Attack Detection Platform for Wind Energy Power Plants. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing (IWCMC), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 12–16 May 2025. [Google Scholar]