Abstract

To address the issues of parameter coupling and high computational demands in existing feed-forward Gaussian splatting methods, we propose Gaussian Patch-level Mixture-of-Experts Splatting (GaPMeS), a lightweight feed-forward 3D Gaussian reconstruction model based on a mixture-of-experts (MoE) multi-task decoupling framework. GaPMeS employs a dual-routing gating mechanism to replace heavy refinement networks, enabling task-adaptive feature selection at the image patch level and alleviating the gradient conflicts commonly observed in shared-backbone architectures. By decoupling Gaussian parameter prediction into four independent sub-tasks and incorporating a hybrid soft–hard expert selection strategy, the model maintains high efficiency with only 14.6 M parameters while achieving competitive performance across multiple datasets—including a Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) of 0.709 on RealEstate10K, a Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) of 19.57 on DL3DV, and a 26.0% SSIM improvement on real industrial scenes. These results demonstrate the model’s superior efficiency and reconstruction quality, offering a new and effective solution for high-quality sparse-view 3D reconstruction.

1. Introduction

High-fidelity, real-time 3D reconstruction remains a central challenge in the fields of computer vision and computer graphics. In recent years, research focus in this domain has undergone a notable evolution—from emphasizing rendering quality to balancing real-time performance, and, more recently, enhancing model generalization. Neural Radiance Fields (NeRF) have achieved remarkable breakthroughs in the photorealism of novel view synthesis; however, their inherent computational complexity and slow inference speed significantly hinder their applicability in scenarios requiring efficient interaction [1]. Against this backdrop, 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS) has emerged as an innovative approach that effectively combines discrete and continuous scene representations, achieving real-time rendering capability while maintaining high-quality synthesis results [2,3].

Nevertheless, conventional 3DGS frameworks predominantly rely on a per-scene optimization paradigm [4]. In response to the challenge of accumulated reconstruction errors caused by inaccurate Gaussian ellipsoid localization in complex scenes, researchers have drawn inspiration from the success of depth-guided sparse-view NeRFs [5,6,7,8,9] and proposed introducing depth priors to optimize geometric representation within individual scenes. Li et al. [10] proposed DNGaussian, which for the first time incorporated an L2 loss on depth priors to constrain the initialization of Gaussian positions, achieving performance surpassing the original 3DGS model across multiple datasets. R. Kumar et al. [11] developed Depth-Aware 3DGS, which takes monocular depth maps as inputs and jointly optimizes them with depth priors during Gaussian pruning, significantly improving 3D reconstruction metrics. To overcome the limitations of traditional sparse point cloud initialization, Xu et al. [12] introduced FreeSplatter, leveraging the pretrained simultaneous localization and mapping model algorithm to enhance camera pose estimation and point cloud initialization quality, thereby improving reconstruction accuracy.

In addition, researchers have explored observation loss functions [13,14,15] and scene densification strategies based on precise depth sensor measurements. These methods introduce depth error penalty terms to enforce alignment between Gaussian distributions and true scene geometry. To improve geometric consistency under sparse-view settings, Han et al. [16] proposed generating supplementary viewpoints via optical warping and designed a binocular view matching loss, effectively reducing distortions around transparent objects and boundary regions—albeit at the cost of partial information loss. However, these approaches typically require scene-specific designs, which considerably limit their generalization and transferability across diverse environments.

To overcome this limitation, the Feed-Forward 3DGS (FF-3DGS) framework was proposed [17], with the primary goal of reconstructing renderable 3D Gaussian representations directly from sparse or multi-view inputs through a single forward pass, thereby enhancing the generalization performance of the reconstruction model.

To address the problem of Gaussian ellipsoid localization being prone to local optima, David Charatan et al. [18] proposed the PixelSplat model, which replaces direct regression of the ellipsoid center with the prediction of a discrete probability distribution along each camera ray. Building upon this, Chen et al. [19] introduced MvSplat, which incorporates a plane-sweep cost volume to explicitly construct cross-view geometric cues. This approach enables the joint learning of multiple Gaussian parameters under RGB-only supervision, highlighting the importance of explicit geometric representations in feedforward models. Xu et al. [20], leveraging the Depth Anything pretrained model [21], proposed DepthSplat, the first bidirectional auxiliary framework that integrates depth estimation with Gaussian splatting, effectively overcoming the geometric representation bottleneck. Extending this line of work, Zheng et al. [22] developed NexusGS, which enhances the scale robustness of depth features through epipolar matching and optical flow estimation, further improving model efficiency. Despite these advances, existing methods generally share two key limitations:

(1) an excessive focus on predicting the Gaussian center position, while relatively neglecting other crucial parameters—such as the covariance matrix—that significantly affect reconstruction quality; and (2) the introduction of complex refinement networks to fuse multi-source features, which substantially increase model complexity and training cost. GaPMeS addresses these two challenges effectively through a lightweight expert network ensemble and a dual-level patch-granularity routing and selection strategy, achieving a better balance between accuracy, efficiency, and generalization.

Moreover, when integrating multi-source features, existing approaches commonly face inherent challenges in modality alignment. The local detail features extracted by Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), the geometric cues produced by monocular depth models, and the global semantic representations captured by Vision Transformers (ViTs) differ markedly in both semantic granularity and spatial resolution [23]. Coarse-grained fusion at the whole-image level often fails to reconcile these structural discrepancies across modalities, leading to representational conflicts and information loss. Current methods typically incorporate complex feature refinement modules following feature extraction, relying on Encoder–Decoder architectures and joint training with visual backbones to improve accuracy. However, such strategies significantly increase model complexity, parameter count, and training overhead.

To address the aforementioned challenges, we propose a novel feedforward Gaussian splatting architecture, GaPMeS (Gaussian Patch-level Mixture-of-Experts Splatting). The main contributions are as follows:

(1) A multi-task learning-based decoupled prediction mechanism, which decomposes the parameter prediction of Gaussian ellipsoids into several structurally relevant sub-tasks. This design alleviates gradient competition and representational entanglement among tasks, thereby improving the coordination between geometric and appearance modeling.

(2) A patch-level Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) feature selection strategy, which adaptively selects appropriate input modalities for each prediction task at a finer patch granularity. This approach effectively mitigates large-scale modality alignment difficulties and enhances the model’s ability to integrate multi-source information.

(3) GaPMeS does not rely on the end-to-end optimization of feature extractors during training, which grants it higher generalization capability and deployment flexibility under limited computational resources. We conducted extensive experiments across multiple datasets under constrained hardware conditions to validate the superior performance of GaPMeS.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 1 presents the motivation behind the GaPMeS model, which leverages a MoE framework to optimize the feedforward Gaussian process. Section 2 provides a detailed overview of existing methods, outlining their fundamental principles and inherent limitations. Section 3 elaborates on the proposed GaPMeS methodology in detail. In Section 4, we conduct comprehensive evaluations on both public and industrial plant datasets, including comparative experiments, ablation studies, gradient conflict analyses, and multi-class visualization experiments, which collectively demonstrate the superiority of GaPMeS. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and highlights directions for future work.

2. Related Work

2.1. Feed-Forward Gaussian Splatting

Recent advances in FF-3DGS have demonstrated that incorporating pre-trained models that provide depth, semantic (e.g., DINOv2 features [24,25]), and texture cues plays a crucial role in accurately estimating the spatial positions (mean parameters) of Gaussian ellipsoids—an essential factor for achieving high-quality reconstruction. However, these studies have also revealed a fundamental limitation in the current paradigm: existing approaches tend to overemphasize the prediction of the mean parameters of Gaussian ellipsoids while neglecting other critical parameters (e.g., covariance matrices) that substantially influence reconstruction quality. This imbalance in parameter optimization leads to gradient conflicts among different reconstruction sub-tasks—such as geometry estimation and appearance modeling—within shared feature representations, resulting in blurred details and performance degradation in regions with complex structures or high-frequency textures.

2.2. Mixture-of-Experts Model and Multi-Task Optimization

Multi-task learning (MTL) aims to enable a single model to learn multiple related tasks simultaneously, thereby improving data utilization efficiency and model generalization capability [26,27]. However, the effectiveness of this approach heavily depends on the degree of inter-1 correlation. When the relationships among tasks are weak, or their objectives diverge, traditional shared-parameter architectures are prone to gradient conflict—a phenomenon where different tasks produce conflicting gradient directions during backpropagation, leading to suboptimal optimization and degraded task performance. Consequently, achieving a balance between knowledge sharing and parameter separation has become a central challenge in multi-task learning [28].

To address this issue, Ma et al. [29] proposed the multi-gate mixture-of-experts (MMoE) model, whose core innovation lies in replacing the conventional single shared backbone with a pool of expert networks, while assigning each task an independent gating network. This design allows the model to dynamically combine expert representations based on input features, thereby generating task-specific representations tailored to individual objectives. As a result, it significantly enhances MTL performance while maintaining data efficiency.

Subsequent studies have further elucidated the underlying mechanisms of MoE architectures. First, such frameworks effectively decouple shared knowledge from task-specific knowledge—for example, Tang et al. [30] treated pre-trained parameters as shared knowledge and task vectors obtained through fine-tuning as task-specific knowledge. Second, MoE frameworks demonstrate strong architectural adaptability, as they can be seamlessly integrated as bottleneck components into various network layers (e.g., feature extractors or connectors) [31], making them suitable for a wide range of applications. These prior works directly inspire the design of our method, which enhances feature selection efficiency in multi-task learning by incorporating the decoupling principles and dynamic routing mechanisms of the MoE framework.

3. Methods

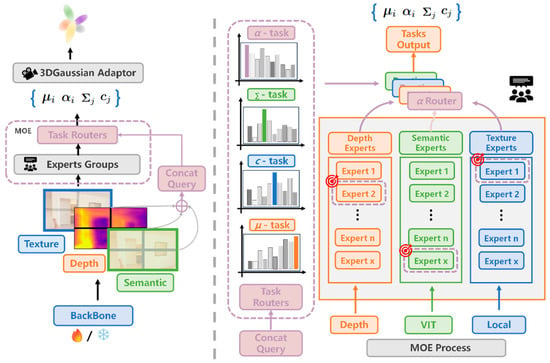

The overall architecture of GaPMeS is illustrated in Figure 1. GaPMeS employs a dual-routing network to achieve feature selection and task-specific decoupling. The input data are first processed by a backbone network to extract texture, depth, and semantic features, which are then concatenated along the channel dimension to form a spatially aligned unified query representation. This representation is fed into both the feature-learning expert router and the task-selection router, which dynamically activate the most relevant expert groups based on a Gumbel-TopK sparse routing mechanism. The activated experts subsequently generate outputs that are independently regressed into 3DGS parameters through task-specific prediction heads, thus realizing forward decoupling in MTL. GaPMeS consists of three core components: multi-modal feature alignment and patch-wise processing, task-oriented patch-level MoE selection, and multi-task decoupled 3DGS parameter prediction. The detailed design of each module is presented in the following sections.

Figure 1.

GaPMeS Framework, the left part illustrates the overall architecture of the model, while the right part presents the expert selection process based on routing values.

3.1. Multimodal Feature Alignment and Patch-Wise Processing

The model input primarily consists of fundamental feature maps with different channel dimensions obtained from three backbone networks: the monocular depth estimation features derived from a pretrained depth estimation model, the local visual features extracted from CNNs, and the global semantic features obtained from ViT. Before being processed by the task-specific expert groups, these features must be channel-aligned and dimensionally normalized.

To preserve the complementary information contained within different feature types—namely, local visual cues from , global semantic representations, and long-range dependencies from —this module employs 1D CNNs as basic channel preprocessing layers. The process can be described by Equation (1):

where denotes the spatial resizing function, and represents the predefined standard feature map resolution.

After multimodal feature extraction, the aligned feature maps are concatenated to form a unified representation . This representation is then uniformly partitioned along the spatial dimensions into image patches, converting the full-scale feature map into a sequence of local patch tokens . This patch-level transformation provides the foundation for subsequent fine-grained routing [32].

3.2. Task-Oriented Patch-Level Experts Selection

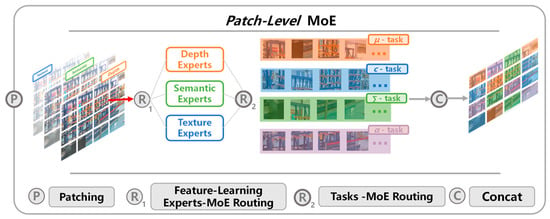

Since each expert network operates as an independently parameterized neural module, it does not directly participate in the feature selection process. Therefore, a dedicated routing network is required to adaptively allocate input representations across different reconstruction sub-tasks. To achieve finer-grained task representation learning, our method performs patch-level routing computation. Specifically, two gating networks are designed: the Feature-Learning Experts MoE Routing for processing input feature representations, and the Task MoE Routing for selecting task-specific feature maps. The overall workflow is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The complete workflow of the patch-level Mixture-of-Experts.

For each image patch , its multimodal features are concatenated along the channel dimension to form a query vector , this concatenated query vector is then fed into both the Feature-Learning Experts-MoE Routing and Task-MoE Routing networks—corresponding to and in Figure 2—to generate the initial routing logits. The process can be formally expressed as in Equations (2)–(6).

Considering computational efficiency, GaPMeS adopts linear layers as the , denotes the standard uniform distribution function, and denotes the -th image patch. Equations (5) and (6) correspond to two independent and identically distributed random sampling processes for the same image patch. Specifically, Equation (5) adds Gumbel noise to the feature–expert routing, while Equation (6) injects another independent Gumbel noise for task routing.

To enable differentiable expert routing for feature extraction, we employ a Gumbel-based selection mechanism. The routing network outputs a routing score for each expert, which is perturbed during training by adding Gumbel noise , resulting in . The expert with the maximum perturbed score is selected.

The Gumbel–Softmax [33] trick is a differentiable discrete sampling method based on extreme value distributions. It samples noise from a standard Gumbel distribution, adds it to the log-probabilities, and applies a temperature-controlled Softmax to obtain a continuous approximation of a one-hot vector. The temperature parameter controls the degree of relaxation: low temperatures approximate true discrete sampling, while higher temperatures produce smoother distributions for stable gradients.

This formulation is motivated by the need to perform expert routing decisions within a gradient-based optimization framework. Directly selecting the expert with the highest routing score would introduce a non-differentiable operation, preventing effective backpropagation. By applying the Gumbel perturbation, the maximum operation becomes a practical approximation of sampling from a categorical distribution, which allows gradients to flow through the selected expert during training. In addition, the injected stochasticity helps avoid deterministic expert assignment and encourages balanced utilization of different experts, leading to more stable optimization. During inference, the Gumbel noise is removed, and expert selection is performed deterministically based on the learned routing scores.

Subsequently, the Top-K selection algorithm is applied to determine which expert networks to activate. This process is formulated in Equations (7) and (8):

where denotes the set of selected feature expert indices for patch represents the preset number of activated experts, corresponds to the task-specific expert index selected for patch. The task-gating routing network activates only one expert for each patch, which is considered the optimal expert for the parameter prediction task associated with .

Both hard routing and soft routing are computed in parallel. In the soft routing path, the Gumbel-TopK trick [31] is introduced to enable gradient propagation through the discrete routing vector during backpropagation, ensuring the trainability of the routing network. This process is described in Equations (9) and (10):

where is the hyperparameter temperature coefficient, typically set to 0.8; are the hard routing weights of the two routing networks for are the soft routing weights of the two routing networks for is the identifier of the expert selected by the two gating networks.

To further simplify computation and improve operational efficiency, this study adopts a combined gradient propagation method. While saving computational resources, it also ensures the computational efficiency of the model. For each , the parameter propagated during the gradient calculation process can be described by Equation (11):

where is a learnable balance parameter; denotes the stop-gradient operation, which can prevent the gradient of from directly affecting the error term , ensuring that the update of primarily relies on the gradient of the loss function rather than the noise brought by hard quantization.

3.3. Multi-Task Decoupled Gaussian Parameter Prediction Module

To avoid the expert network becoming overly bloated and computationally expensive, we replace the large representation refinement layers commonly used in existing methods with a lightweight three-layer convolutional neural network. This design choice is motivated by practical computational constraints and the goal of enabling efficient feed-forward inference under limited hardware resources, and the same resource-aware principle is applied consistently throughout our experimental pipeline, including baseline reproductions conducted under constrained training settings to ensure fair and comparable evaluation. Any is processed as shown in Equations (12)–(15):

where is an inverse operation; it collects all patches that feature assigned to task , and CONCAT them back into a complete feature map is the task identifier and is the output result of the feature learning expert group network.

To ensure that the numerical ranges and physical meanings of different physical quantities are consistent, this paper selects appropriate nonlinear mapping activation functions for each of the four task heads. The aggregated expert output will pass through a layer, then be mapped back to the spatial resolution and average-pooled. The computation process for each task head is shown in Equation (16):

where Sigmoid applies the opacity to [0, 1], thereby satisfying its physical interpretability as a probability; Tanh constrains the central coordinates and color to (−1, 1), facilitating subsequent normalization to camera coordinates; ReLU ensures the non-negativity of the covariance or expansion vector , thus making the Gaussian matrix positive-definite.

The above decoupling design ensures the numerical consistency of the four types of Gaussian parameters while enabling effective gradient divergence through a two-level architecture that transitions from shared to task-specific representations. This approach achieves an efficient decoupling of Gaussian primitive parameters without relying on bulky U-Net refinement networks, thereby avoiding the parameter coupling issues commonly observed in traditional feedforward Gaussian methods.

3.4. Novel View Rendering and Loss Functions

Given the camera’s extrinsic matrix, the 3D Gaussians can be projected onto the 2D image plane. The projection process is shown in Equations (17) and (18):

where is the Jacobian matrix of the projective transformation. Subsequently, the overlapping Gaussians are sorted based on their post-projection depth values, generating a sequence of Gaussians affecting each pixel.

GaPMeS adopts the classical volume rendering equation, performing cumulative composition on the ordered Gaussians along the pixel ray, as shown in Equations (19) and (20):

where represents the probability that the ray reaches the -th Gaussian splat unoccluded; denotes the final synthesized color for pixel is the RGB value of the -th Gaussian; and is the opacity of the -th Gaussian splat multiplied by its 2D Gaussian distribution weight.

The loss function employed is the standard 3DGS model loss function, as shown in Equation (21):

where the computation process and explanation for Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) can be found in Section 4.1; is predefined loss weighting context; is the th viewpoint image obtained from inference rendering; and is the ground-truth -th viewpoint image.

4. Experiments and Discussion

4.1. Evaluation Metrics

The study employs the Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), PSNR, and LPIPS to provide a comprehensive evaluation of model performance. These three metrics complement each other across structural fidelity, numerical accuracy, and perceptual similarity, collectively validating the model’s effectiveness in depth estimation and novel view synthesis tasks. Specifically, SSIM focuses on local structural consistency, PSNR emphasizes global pixel-level accuracy, and LPIPS assesses visual quality from a higher-level semantic perspective. Together, they offer a multi-faceted quantitative analysis of model performance [27,28,29,34].

SSIM measures the similarity between generated and ground-truth images in terms of luminance, contrast, and structure, with a range of ; values closer to 1 indicate higher structural consistency. The computation of SSIM is defined as in Equations (22) and (23):

where and are the local window mean values of images and respectively; are the local window standard deviations of images is the local window covariance of images and are set as non-zero constants.

where are predefined constants; typically represents the luminance comparison between the different images; typically represents the edge visibility contrast between the different images; and is positively correlated with the main contour distinctions between the two images.

PSNR is a pixel-level accuracy metric based on mean squared error, expressed in decibels. Higher PSNR values indicate better image quality. The computation of PSNR is defined in Equations (24) and (25):

where denotes the maximum pixel value of the image.

The core objective of LPIPS is to simulate the human visual system and measure image similarity at the level of deep semantic features [35]. It typically uses the perceptual representations from a pretrained VGG network [36] as the basis for evaluation. The computation of LPIPS is defined in Equations (26) and (27):

where denotes the layer index of the visual network model; represents the unit-normalized feature vector at position in layer of the inferred/rendered image; and represents the corresponding feature vector for the ground-truth image. denotes the squared L2 norm, used to amplify the penalty for discrepancies.

4.2. Computational Constraint Experimental Setup

We used the RealEstate10K [37] and DL3DV [38] datasets, which are standard benchmarks in 3D reconstruction covering diverse indoor and outdoor scenes. Following prior work, we adopt the following training and testing splits. RealEstate10K consists of real estate videos collected from YouTube and is divided into 67,477 training scenes and 7289 testing scenes. For DL3DV, we follow the official DL3DV-Benchmark split and evaluate our method on 140 test scenes. The training data are drawn from the DL3DV-480p dataset, with all test scenes explicitly excluded to avoid data leakage. For the custom industrial dataset, due to the limited number of available samples and to assess the generalization capability of the proposed model, we directly evaluate the model using weights pretrained on RealEstate10K without additional fine-tuning on the industrial data.

Due to computational constraints, the down-sampling factor for the multi-view branch features was dynamically adjusted according to the input image resolution; for example, was used for the RealEstate10K dataset (image resolution 256 × 256). To ensure a fair and resource-aware comparison, all baseline models were retrained under the same limited hardware conditions using an NVIDIA RTX 5880 ADA (48GB), rather than replicating the original large-scale training configurations reported in their respective papers. As a result, the reproduced baseline results are not intended as direct replications of the original reference settings, but as best-effort evaluations under constrained computational resources. Pre-trained backbone models followed the UniMatch configuration to ensure fair comparison [39]. To avoid out-of-memory (OOM) issues, all experiments were standardized with a total of 30K iterations, a total batch size of 4, and a single-GPU batch size of 1. Specifically, on the RealEstate10K dataset, the number of auxiliary views was extended to four. For the DL3DV dataset, the model was first pretrained for 1K iterations on RealEstate10K, after which the backbone was frozen, and the pretrained model was trained for 30K iterations with two reference views per single-frame image. All experiments were implemented in the PyTorch (version 2.0) framework, optimized using the AdamW [40] optimizer combined with a cosine learning rate scheduler. For inference, considering general applicability, we use the NVIDIA RTX 4090 (24 GB) as the benchmark device for performance comparison.

In addition to the above, other configuration parameters are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Configuration parameter list.

During the feature extraction stage, we employed pretrained models, including the monocular depth estimation model Depth_Anything_v2 (ViT-B) and the visual semantic representation model DINOv2 (ViT-B). For the MoE framework, we drew inspiration from the LoRA [41] paradigm and adopted lightweight trainable networks such that both the expert networks and the routing network were re-trained for each training run. This design enabled task-adaptive feature transformation of pretrained model knowledge for each Gaussian parameter prediction, while avoiding retraining the pretrained backbones, thereby significantly reducing training overhead.

4.3. Effectiveness Comparison Experiments

The baseline models selected for comparison include state-of-the-art feedforward 3DGS and feedforward NeRF frameworks:

- Depthsplat [20]: Employs a collaborative training architecture combining FF3DGS with the Depth Anything depth estimation model, enabling the simultaneous optimization of parameters in both models during training.

- Mvsplat [19]: Utilizes a cost-volume similarity computation method to determine candidate depths for each Gaussian ellipsoid, and adopts a cross-view Transformer architecture to extract multi-view features.

- Pixelsplat [18]: Applies an epipolar line pairing and sampling strategy to identify candidate depths for each Gaussian ellipsoid, also employing a cross-view Transformer for feature extraction.

- PixelNeRF [42]: Constructs a 3D-NeRF representation by integrating multi-view 2D image features through a cross-view Transformer model.

- Transplat [43]: Transformer-based method that utilizes depth-awareness to achieve high-quality, generalizable 3D reconstruction and novel view synthesis from sparse input images.

The comparative experimental results on the RealEstate10k and DL3DV datasets are presented in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 2.

Experimental results on the RealEstate10K dataset (4 views).

Table 3.

Experimental results on the DL3DV dataset (2 views).

Table 4.

Experimental results on the DL3DV dataset (4 views).

The experimental results on the RealEstate10K (4-view) (Table 2) demonstrate that the proposed method achieves state-of-the-art performance across multiple key metrics. Specifically, our model, with only 14.6 M parameters, surpasses all baseline methods in SSIM (0.709), PSNR (20.20), and LPIPS (0.258). Notably, even models with substantially larger parameter counts—DepthSplat (117.0 M) and PixelSplat (125.8 M)—underperform compared to our lightweight design, validating the effectiveness of our multi-task decoupling architecture and mixture-of-experts framework. This design enables the model to explicitly learn inter-task relationships from data: for highly correlated tasks, the gating networks tend to select similar expert combinations; for tasks with greater divergence, they favor different expert sets, thereby effectively mitigating task conflicts. For the relatively low-parameter models Mvsplat and Transplat, they still adhere to the mainstream approach of constraining Gaussian ellipsoid positions through depth cues. The features fed into their Gaussian parameter predictors are optimized primarily for depth estimation, which consequently leads to suboptimal reconstruction quality.

We additionally report the per-epoch training time of the compared methods on the RealEstate10K dataset. DepthSplat requires approximately 14.45 s per epoch, while MV-Splat and TransSplat take about 7.34 s per epoch. In contrast, GaPMeS achieves a reduced training time of approximately 6.29 s per epoch. This efficiency gain stems from the removal of heavy refinement layers, resulting in faster training and lower inference overhead.

Experiments on the more challenging DL3DV dataset further validate the superiority of our approach (Table 4). When the number of input views increases to four, Depthsplat, Pixelsplat, and PixelNeRF all encounter out-of-memory (OOM) issues, whereas our model remains stable and significantly outperforms the only runnable baseline, MVSplat, achieving +0.142 SSIM and +5.67 PSNR improvements. Even under the two-view setting (Table 3), our model attains the best SSIM and PSNR scores with the fewest parameters (14.6 M). Additionally, the latest H3R [44] employs SD-VAE representations to replace the semantic representations from DINO, further enhancing its method’s performance. This also validates our conclusion that choosing an appropriate representation for the Gaussian adapter can improve model performance more effectively than employing sophisticated refinement networks.

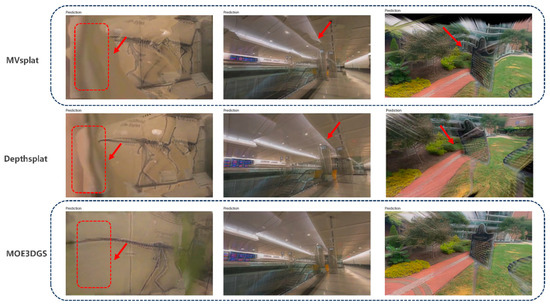

To further validate the GaPMeS model, Figure 3 presents a qualitative comparison with MVSplat and DepthSplat in novel view synthesis. For fine textures (e.g., the museum scene in the first column), MVSplat and DepthSplat show noticeable blurring and detail loss, with DepthSplat even producing ghosting at key structures (arrows), whereas GaPMeS successfully reconstructs clear contours and background textures. Baseline models often share low-level features across tasks, causing gradient interference and task coupling conflicts—for example, differences in spatial distribution between transparency and covariance objectives can lead to blurred details. In challenging scenarios with complex geometry and reflective surfaces (e.g., the subway scene in the second column), baseline methods produce artifacts, while GaPMeS, leveraging fine-grained representation learning, nearly eliminates distortions and generates structurally accurate and photorealistic results. Similarly, for sparse structures and background separation (e.g., the outdoor sign scene in the third column), GaPMeS avoids the striping artifacts seen in MVSplat and DepthSplat, achieving clean edges and precise reconstruction. These qualitative results demonstrate that GaPMeS consistently produces high-fidelity, artifact-free images across diverse complex scenes, confirming the effectiveness of our multi-task decoupling architecture and mixture-of-experts design, achieving visual quality surpassing larger models like DepthSplat with only 14.6 M lightweight parameters.

Figure 3.

Visualization-based comparative experiments.

4.4. Ablation Studies and Subtask Independence Analysis

To evaluate the effectiveness of each core component in the GaPMeS model, we conducted a systematic ablation study on the RealEstate10K dataset, with results presented in Table 4.

- All-Module: The complete model containing all components.

- w/o-Depth: Removes the depth branch from the multimodal input and its associated expert processing networks.

- w/o-Experts_MoE: Removes the feature-learning expert group and its corresponding gating network.

- w/o-Tasks_MoE: Removes the task-selection routing gating network, directly using the full feature map for Gaussian parameter prediction.

The ablation study results as shown in Table 5 clearly validate the necessity of each core component in GaPMeS; while the complete model achieves optimal performance (SSIM 0.709, PSNR 20.20), removing any component leads to significant performance degradation. Specifically, eliminating depth features causes a 33.3% relative drop in SSIM, underscoring the fundamental role of geometric priors. Removing the expert selection mechanism results in a 21.9% decrease in PSNR, demonstrating the value of adaptive multi-modal feature fusion. Most notably, the absence of the task decoupling component causes the most severe performance deterioration (34.3% SSIM reduction), strongly confirming that mitigating gradient conflicts through the dual-path routing mechanism constitutes the core contribution of our method.

Table 5.

Ablation experimental results.

To evaluate the robustness of the GaPMeS model to variations in key hyperparameters, we conduct systematic sensitivity experiments on three factors: the MoE temperature parameter (), the number of experts (), and the number of experts activated during task selection (). All experiments are performed on the RealEstate10K dataset and evaluated using SSIM, PSNR, and LPIPS. The results are reported in Table 6.

Table 6.

Parameter sensitivity experimental results.

The sensitivity analysis demonstrates that GaPMeS exhibits strong robustness across variations in key hyperparameters. Adjusting the temperature parameter within the range of 0.4 to 0.8 results in only minor performance fluctuations (SSIM remaining above 0.682), indicating that the routing mechanism is insensitive to the degree of stochasticity. Model performance remains stable when the number of experts is set to six or eight (SSIM of 0.709 and 0.687, respectively), with a noticeable degradation only observed when reduced to four, suggesting sufficient capacity flexibility. Similarly, activating either one or two experts yields near-optimal performance (SSIM of 0.691 and 0.709), demonstrating the stability of sparse activation strategies. Overall, under common configurations ( = 0.6–0.8, 6–8 experts, = 1–2), performance variations remain within 5%, with optimal values lying in a reasonable range. Even under suboptimal settings, GaPMeS consistently outperforms most baseline methods, confirming its inherent fault tolerance and adaptability, and making it well-suited for deployment in computation-limited environments without extensive hyperparameter tuning.

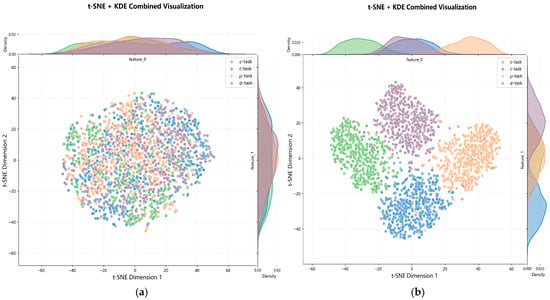

We employed t-SNE combined with KDE for feature-space visualization to verify the effectiveness of the task-oriented MoE mechanism. As shown in Figure 4, at the early stage of training, patch features selected by the task-MoE are highly entangled. After 30K iterations, features corresponding to different reconstruction sub-tasks form well-separated clusters in the reduced-dimensional space, with minimal overlap in their core distributions. This indicates that the MoE routing mechanism successfully decouples task-specific feature representations, enabling each expert network to learn highly specialized features and effectively alleviating ambiguity in multi-task Gaussian ellipsoid parameter prediction.

Figure 4.

Effectiveness analysis of feature selection in the Task-MoEs network: (a) patch representations selected by task heads at the early training stage; (b) after 30k iterations.

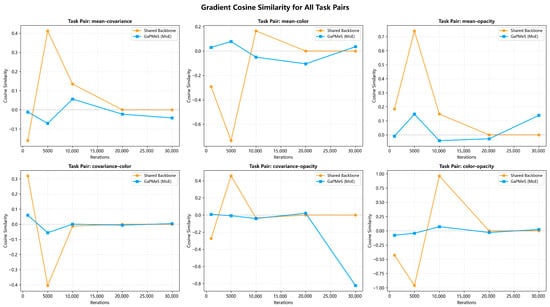

To further validate the effectiveness of our proposed MoE-based decoupling, this experiment employs a comparative design to reveal the optimization dynamics in multi-task learning through gradient analysis. The core idea is to construct a baseline model with explicitly shared parameters for reference. This Shared Backbone model follows a typical multi-task learning architecture: a single shared feature extraction backbone is followed by four independent task-specific heads. All task heads receive the same backbone features and perform their respective parameter predictions. This design ensures that all backbone parameters must simultaneously respond to gradient updates from all four tasks, creating a potential hotspot for gradient conflicts. Experimental results, shown in Figure 5, compare this baseline with GaPMeS, which uses path-separated routing, allowing precise quantification of the effectiveness of the MoE architecture in mitigating inconsistent gradient directions across tasks. We plot Gradient Cosine Similarity [45] over training iterations to compare the dynamics of gradient similarity between the Shared Backbone and GaPMeS during multi-task learning. The analysis shows that the Shared Backbone exhibits severe gradient conflicts: similarity scores fluctuate drastically and frequently drop to strongly negative values (e.g., the color-opacity task pair reaches nearly −1.0 at 5000 iterations), indicating strong antagonism between the optimization objectives of different tasks. In contrast, the GaPMeS model maintains stable similarity scores near zero across all six task pairs, demonstrating effective gradient decoupling. This result strongly confirms that GaPMeS successfully orthogonalizes task gradients, effectively alleviating multi-task gradient conflicts and ensuring a stable and efficient training process.

Figure 5.

Experimental analysis of the effectiveness of gradient decoupling in the MoE model.

4.5. Generalization Experiments

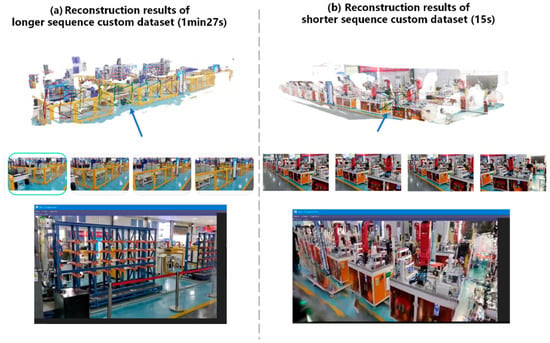

In this experiment, we tested the model on self-collected real industrial plant data, where accurate camera poses were unavailable. The dataset consists of six real industrial plant video sequences, ranging from 15 s to 1 min 27 s, covering a variety of common industrial facilities. Unlike traditional 3D Gaussian Splatting methods that rely on sparse point clouds initialized by COLMAP, our approach does not require sparse point cloud initialization. Instead, we employ the state-of-the-art visual SLAM model VGGT [46] to obtain accurate camera pose estimates, which are directly used as unprocessed 6-DoF poses. The model was fine-tuned on our dataset based on pretraining on the RealEstate10K dataset, with the number of auxiliary views set to two. Experimental results are presented in the following table, and the organization of our custom dataset follows the LLFF format [47]. The baseline models for comparison include feedforward methods (DepthSplat, MvSplat) and non-feedforward methods (3DGS, DNGaussian, DSNeRF [8], PIDSNeRF [9], Point-NeRF [48]). For the non-feedforward models, we consistently provided 20 input frames.

The experimental results on the real industrial plant dataset without precise camera poses demonstrate that the GaPMeS model exhibits outstanding overall performance in complex scenes. As shown in the Table 7, GaPMeS outperforms all baseline models in SSIM (0.611) and PSNR (18.10), while also achieving the best perceptual quality measured by LPIPS (0.253). Notably, compared with other feedforward methods such as DepthSplat and MvSplat, GaPMeS achieves significant improvements across all metrics—approximately 26% increase in SSIM—validating the advantages of the mixture-of-experts architecture in feature selection and task decoupling. We visualize the reconstructed content as shown in Figure 6, and the results demonstrate that our method exhibits strong reconstruction performance for both short-length and long-length videos.

Table 7.

Generalization test results.

Figure 6.

Generalization effectiveness experiments of GaPMeS on the industrial scene dataset.

Even when compared with non-feedforward methods that require multi-frame optimization, GaPMeS surpasses these methods in performance through its single forward-pass inference while maintaining real-time capability. This strongly demonstrates the method’s effectiveness in achieving high-quality reconstruction under limited computational resources. Additionally, scene-specific optimization methods place higher demands on input data quality—especially under sparse-view settings, where they require stronger geometric consistency priors from the input viewpoints, making them more sensitive to the selection of these viewpoints.

5. Conclusions

The paper presents and validates GaPMeS, a feed-forward Gaussian splatting model designed for resource-constrained environments, which effectively addresses key challenges in existing feed-forward 3D Gaussian reconstruction methods through an innovative multi-task decoupling and mixture-of-experts architecture.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- Gaussian Parameter Prediction via Multi-task Decoupling: We propose a task-decomposed framework that splits Gaussian parameter estimation into four structurally related sub-tasks (mean, covariance, color, and opacity). This strategy mitigates gradient conflicts caused by optimization imbalance in conventional methods, thereby improving geometric accuracy and appearance fidelity in complex scenes.

- Task-oriented Patch-level Mixture-of-Experts Selection: A dual-gating routing mechanism is introduced to adaptively select the most suitable input modalities and expert combinations for each sub-task at the image-patch level. This design enables fine-grained alignment across depth, texture, and semantic features, alleviating representation conflicts and information loss caused by coarse feature fusion.

- Efficient and Computation-Adaptive Architecture: The proposed method eliminates the need for end-to-end backbone optimization during training. Through sparse activation and path separation, GaPMeS maintains a lightweight parameter count (14.6 M) while surpassing all baselines under the same experimental settings. Specifically, it achieves an SSIM of 0.709 on the 4-view RealEstate10K dataset (+3.5%), a PSNR of 19.57 on the 2-view DL3DV dataset (+2.7%), and a 26.0% relative SSIM improvement on the custom industrial dataset.

Despite these promising results, several limitations remain. Owing to computational constraints, the reconstruction performance of GaPMeS under higher-resolution or dense multi-view settings has not yet been fully validated. Moreover, during empirical evaluation, we observe that existing reconstruction methods—including our own—tend to perform well only under specific viewpoint distributions and exhibit limited generalization across heterogeneous datasets. This limitation primarily stems from the fact that most current models are designed to infer latent geometric cues of all objects within a scene; when the input data lack sufficient geometric information, reconstruction quality degrades substantially. To address this issue, we plan to incorporate generative models into the GaPMeS learning–rendering pipeline to provide stronger geometric priors.

In addition, the current multimodal feature extraction relies on pretrained backbones derived from specific datasets. Future work will explore large-scale joint or self-supervised pretraining strategies to further improve generalization and robustness across diverse scenarios

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and W.L.; methodology, J.L. and W.L.; formal analysis, W.L.; investigation, R.G.; resources, J.L. and R.G.; data curation, R.G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L. and W.L.; writing—review and editing, W.L.; visualization, R.G.; supervision, R.G.; project administration, J.L.; funding acquisition, W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Hubei Provincial Department of Science and Technology’s Science and Technology Talent Service Enterprise Project, grant number 2024DJC033.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The RealEstate10K dataset is available at https://github.com/google/realestate10k (accessed on 12 October 2025), and the DL3DV dataset can be accessed at https://github.com/hhutranscv/Dl3dvEasyDownload (accessed on 12 October 2025). The industrial plant dataset can be obtained upon request from the authors. The code can be accessed via https://github.com/jinwenliugoodlucky-lgtm/GaPMeS01 (accessed on 6 January 2026).

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude for the data support provided by Hubei Shiruida Heavy Engineering Machinery Co., Ltd.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Rui Guo was employed by the company Hubei Shiruida Heavy Engineering Machinery Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Chen, T.; Yang, Q.; Chen, Y. Overview of NeRF Technology and Applications. J. Comput.-Aided Des. Comput. Graph. 2025, 37, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, B.; Xu, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, Q.; Yang, W.; He, Y. 3d gaussian splatting as new era: A survey. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2024, 31, 4429–4449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerbl, B.; Kopanas, G.; Leimkühler, T.; Drettakis, G. 3D Gaussian splatting for real-time radiance field rendering. ACM Trans. Graph. 2023, 42, 139:1–139:14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, J.; Cao, Y.; Yan, L. Recent advances in 3d gaussian splatting. Comput. Vis. Media 2024, 10, 613–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Ge, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Hu, D. Td-nerf: Novel truncated depth prior for joint camera pose and neural radiance field optimization. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 14–18 October 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 372–379. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, D.; Su, Y.; Zhang, H. Enhancing View Synthesis with Depth-Guided Neural Radiance Fields and Improved Depth Completion. Sensors 2024, 24, 1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, X.; Xu, X.; Jin, T.; Jin, Z. Depth-based dynamic sampling of neural radiation fields. Electronics 2023, 12, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Liu, A.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Ramanan, D. Depth-supervised nerf: Fewer views and faster training for free. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 12882–12891. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Shao, H.; Deng, X.; Jiang, Y. PIDSNeRF: Pose interpolation depth supervision neural radiance fields for view synthesis from challenging input. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2025, 84, 22539–22559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Bai, X.; Zheng, J.; Ning, X.; Zhou, J.; Gu, L. Dngaussian: Optimizing sparse-view 3d gaussian radiance fields with global-local depth normalization. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 20775–20785. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Vats, V. Few-shot novel view synthesis using depth aware 3D gaussian splatting. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Gao, S.; Shan, Y. Freesplatter: Pose-free gaussian splatting for sparse-view 3d reconstruction. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Honolulu, HI, USA, 19–25 October 2025; pp. 25442–25452. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, C.; Gao, R.; Shao, K.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, R.; Zhang, Y. Li-gs: Gaussian splatting with lidar incorporated for accurate large-scale reconstruction. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 10, 1864–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Fu, L.; Peng, S.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Xia, J.; Zhou, X. LiDAR-RT: Gaussian-based ray tracing for dynamic lidar re-simulation. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Shanghai, China, 15–18 October 2025; pp. 1538–1548. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, R.; Xu, W.; Tang, L.; Wang, R.; Xu, W. Structure consistent gaussian splatting with matching prior for few-shot novel view synthesis. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 97328–97352. [Google Scholar]

- Han, L.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Y.S.; Zhou, J. Binocular-guided 3d gaussian splatting with view consistency for sparse view synthesis. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–15 December 2024; Volume 37, pp. 68595–68621. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.; Xu, X.; Yin, H.; Wang, Z.; Feng, J.; Zhou, J.; Lu, J. IGL-Nav: Incremental 3D Gaussian Localization for Image-goal Navigation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Honolulu, HI, USA, 19–25 October 2025; pp. 6808–6817. [Google Scholar]

- Charatan, D.; Li, S.; Tagliasacchi, A.; Sitzmann, V. pixelsplat: 3d gaussian splats from image pairs for scalable generalizable 3d reconstruction. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 19457–19467. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, H.; Zheng, C.; Zhuang, B.; Pollefeys, M.; Geiger, A.; Cham, T.-J.; Cai, J. Mvsplat: Efficient 3d gaussian splatting from sparse multi-view images. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 370–386. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Peng, S.; Wang, F.; Blum, H.; Barath, D.; Geiger, A.; Pollefeys, M. Depthsplat: Connecting gaussian splatting and depth. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Shanghai, China, 15–18 October 2025; pp. 16453–16463. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, J.; Zhang, H.; Miao, J. Depthanything and SAM for UIE: Exploring large model information contributes to underwater image restoration. Mach. Vis. Appl. 2025, 36, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Jiang, Z.; He, S.; Sun, Y.; Dong, J.; Zhang, H.; Du, Y. NexusGS: Sparse View Synthesis with Epipolar Depth Priors in 3D Gaussian Splatting. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Shanghai, China, 15–18 October 2025; pp. 26800–26809. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhai, Y.; Ma, Y.; Lecun, Y.; Xie, S. Eyes wide shut? exploring the visual shortcomings of multimodal llms. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 9568–9578. [Google Scholar]

- Oquab, M.; Darcet, T.; Moutakanni, T.; Vo, H.; Szafraniec, M.; Khalidov, V.; Fernandez, P.; Haziza, D.; Massa, F.; El-Nouby, A.; et al. Dinov2: Learning robust visual features without supervision. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.07193. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Zou, J.; Meng, L.; Yue, X.; Zhao, Q.; Li, J.; Song, C.; Jimenez, G.; Li, S.; Fu, G. Comparative analysis of imagenet pre-trained deep learning models and dinov2 in medical imaging classification. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 48th Annual Computers, Software, and Applications Conference (COMPSAC), Osaka, Japan, 2–4 July 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 297–305. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, W.; Ning, Z.; Qi, Z.; Yu, P.S. Mixture of experts (moe): A big data perspective. Inf. Fusion 2026, 127, 103664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Liu, X.; Luo, C.; Huang, J.; Zhou, R.; Liu, Y.; Hu, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, D.; et al. Multitask learning 1997–2024: Part I fundamentals. Harv. Data Sci. Rev. 2025, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Er, M.J. Mitigating gradient conflicts via expert squads in multi-task learning. Neurocomputing 2025, 614, 128832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhao, Z.; Yi, X.; Chen, J.; Hong, L.; Chi, E.H. Modeling task relationships in multi-task learning with multi-gate mixture-of-experts. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, London, UK, 19–23 August 2018; pp. 1930–1939. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, A.; Shen, L.; Luo, Y.; Yin, N.; Zhang, L.; Tao, D. Merging Multi-Task Models via Weight-Ensembling Mixture of Experts. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Vienna, Austria, 21–27 July 2024; pp. 47778–47799. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Hu, Y.; Mo, F.; Wu, J.; Zhu, X. Uni-med: A unified medical generalist foundation model for multi-task learning via connector-MoE. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 81225–81256. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, Y.; Hou, Q.; Cheng, M.-M.; Yang, J. Sm3det: A unified model for multi-modal remote sensing object detection. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, C.; Bowen, R.S.; Zabih, R. Channel selection using gumbel softmax. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 241–257. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Xiang, Z.; Lei, K.; Zhang, X.-Y. Multi-Task Model Fusion via Adaptive Merging. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Hyderabad, India, 6–11 April 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A.; Shechtman, E.; Wang, O. The unreasonable effectiveness of deep features as a perceptual metric. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 586–595. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S.R.; Qadri, S.; Bibi, H.; Shah, S.M.W.; Sharif, M.I.; Marinello, F. Comparing inception V3, VGG 16, VGG 19, CNN, and ResNet 50: A case study on early detection of a rice disease. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Tucker, R.; Flynn, J.; Fyffe, G.; Snavely, N. Stereo magnification: Learning view synthesis using multiplane images. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2018, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, L.; Sheng, Y.; Tu, Z.; Zhao, W.; Xin, C.; Wan, K.; Yu, L.; Guo, Q.; Yu, Z.; Lu, Y.; et al. Dl3dv-10k: A large-scale scene dataset for deep learning-based 3d vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 22160–22169. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.; Li, T.; Du, M.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Wang, Z.; Liu, H.; Xu, H. UniMatch: A Unified User-Item Matching Framework for the Multi-purpose Merchant Marketing. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 39th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), Anaheim, CA, USA, 3–7 April 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 3309–3321. [Google Scholar]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, New Orleans, LA, USA, 6–9 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, W. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Virtual, 25–29 April 2022; Volume 1, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, A.; Ye, V.; Tancik, M.; Kanazawa, A. pixelnerf: Neural radiance fields from one or few images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 4578–4587. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Zou, Y.; Li, Z.; Yi, M.; Wang, H. Transplat: Generalizable 3d gaussian splatting from sparse multi-view images with transformers. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2025, 39, 9869–9877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Zhu, L.; Zhao, N. H3R: Hybrid Multi-view Correspondence for Generalizable 3D Reconstruction. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Honolulu, HI, USA, 19–25 October 2025; pp. 7655–7665. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, T.; Kumar, S.; Gupta, A.; Levine, S.; Hausman, K.; Finn, C. Gradient surgery for multi-task learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 5824–5836. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Chen, M.; Karaev, N.; Vedaldi, A.; Rupprecht, C.; Novotny, D. Vggt: Visual geometry grounded transformer. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Shanghai, China, 15–18 October 2025; pp. 5294–5306. [Google Scholar]

- Mildenhall, B.; Srinivasan, P.P.; Tancik, M.; Barron, J.T.; Ramamoorthi, R.; Ng, R. Nerf: Representing scenes as neural radiance fields for view synthesis. Commun. ACM 2021, 65, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Xu, Z.; Philip, J.; Bi, S.; Shu, Z.; Sunkavalli, K.; Neumann, U. Point-nerf: Point-based neural radiance fields. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 5438–5448. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.