Abstract

The spinal angle is an important indicator of body balance. It is important to restore the 3D shape of the human body and estimate the spine center line. Existing multi-image-based body restoration methods require expensive equipment and complex procedures, and single image-based body restoration methods struggle to accurately estimate internal structures such as the spine center line due to occlusion and viewpoint limitation. This study proposes a method to compensate for the shortcomings of the multi-image-based method and to overcome the limitations of the single-image method. We propose a 3D body posture analysis system that integrates depth images from four directions to restore a 3D human model and automatically estimate the spine center line. Through hierarchical matching of global and fine registration, restoration to noise and occlusion is performed. In addition, adaptive vertex reduction is applied to maintain the resolution and shape reliability of the mesh, and the accuracy and stability of spinal angle estimation are simultaneously secured using the level of detail (LOD) ensemble. The proposed method achieves high-precision 3D spine registration estimation without relying on training data or complex neural network models, and the verification confirms the improvement in matching quality.

1. Introduction

The posture and balance of a person serve as important indicators of overall physical health, extending beyond simple movement patterns. Various studies have shown that posture and balance are directly related to pain, musculoskeletal disorders, fall risk, and quality of life. Kumar et al. [1] noted that the registration and curvature of the spine, including the cervical vertebrae, are closely associated with musculoskeletal disorders. Additionally, Ishikawa et al. [2] found that spinal mobility and sagittal registration are directly connected to the quality of life and fall risk in older adults. Du et al. [3] and Hussein et al. [4] also emphasized that analyzing the spine is a crucial measure for understanding physical health. Furthermore, Smythe et al. [5] pointed out that while the concept of “good posture” is ambiguous, the evaluation of posture remains significant. These preceding studies indicate that estimating the spinal centerline to analyze human posture is an important task in fields such as rehabilitation medicine, ergonomics, and healthcare.

However, because the position of the spine corresponds to internal human structures, accurately determining the central axis using only typical 2D images is challenging. To overcome this limitation, various 3D human reconstruction techniques have been proposed. Methods based on multiple RGB cameras, as noted by Nogueira et al. [6], offer high accuracy but require expensive equipment and complex calibration procedures, limiting their use in general environments. In contrast, approaches using depth images have garnered attention for being relatively low-cost [7,8,9,10]. Research utilizing single-point depth images has been actively conducted [11,12]. However, as highlighted by Zhang et al. [13], there remains a limitation in reliably estimating the entire human shape or internal central structures like the spinal axis due to issues of occlusion from the frontal and rear perspectives.

To address these issues, this study proposes a system for reconstructing a 3D model of the human body by combining depth maps obtained from four directions—front, back, left, and right—and automatically estimating the spinal centerline from these data. The proposed system converts the depth data from each direction into point clouds and undergoes two stages: global registration based on RANSAC (random sample consensus) and FPFH (fast point feature histogram), followed by fine registration using the ICP (iterative closest point) algorithm to create an integrated 3D human model. The generated model is refined through a vertex reduction process to remove noise and correct the human shape, ensuring a stable human model. A morphological analysis is then performed on this 3D model to estimate the position of the spine.

The objective of this research is to present a method for inferring the central structures of the human body solely through pure geometric registration and morphological analysis, without reliance on complex training data or deep learning models. This approach avoids issues such as data sparsity and privacy regulations prevalent in medical imaging contexts, while ensuring that each stage of the algorithm is clear and interpretable, facilitating verification. Consequently, this study presents a 3D human analysis pipeline that can be utilized in both medical and non-medical environments, with the potential for expansion into various fields such as healthcare, rehabilitation medicine, posture correction, ergonomic design, and digital human modeling.

2. Background Research

Three-dimensional human body reconstruction plays a vital role in various applications, including medical diagnosis, body shape analysis, and virtual fitting. In particular, 3D modeling based on medical imaging provides essential information for accurately determining a patient’s body shape, which is crucial for diagnosis and treatment planning. Recent research can be categorized based on methods that utilize single RGB images, multi-view images, and depth information. Depth map-based 3D reconstruction offers fine geometric information that can be difficult to obtain using only an RGB camera, significantly enhancing the accuracy of shape restoration. In the context of medical imaging, depth information obtained from CT scans or depth sensors enables the accurate representation of body shapes while maintaining anatomical consistency.

The fusion of multi-view depth maps effectively addresses the occlusion problem of single views, allowing for the generation of complete 3D models. Approaches that use four-directional depth maps integrate information from the front, back, left, and right to create a fully comprehensive human model. Point cloud registration is a crucial step in 3D reconstruction, involving the integration of point cloud data acquired from different viewpoints into a single, consistent coordinate system. Traditional registration methods are typically composed of two main stages: feature-based global registration and iterative refinement, which help ensure accurate data registration.

2.1. Point Cloud Registration

2.1.1. Feature-Based Global Registration

RANSAC (random sample consensus) [14] has established itself as a standard method for estimating robust transformation matrices from data containing outliers. RANSAC removes outliers through random sampling and performs initial registration using only inliers, demonstrating relatively stable performance even in environments with noise and partial overlap. However, it may fail to converge in extreme cases where the outlier ratio exceeds 50%, and its computational cost can significantly increase with the number of iterations.

The FPFH (fast point feature histogram) [15] is a geometric feature descriptor that quantifies the normals, curvature, and surface curvature patterns around each point into a 3D histogram. FPFH enables more robust correspondence point detection compared to simple distance-based matching; however, it is sensitive to noise and shows reduced discriminative power in flat areas. Research by Zheng [16] has reported a decrease in FPFH accuracy in the fusion of multi-source point clouds with noise and local distortions, proposing a CNN-based virtual correspondence generation method to overcome this. Moreover, in flat surfaces, the small curvature variation reduces the discriminative capability of the FPFH, leading to mismatches in correspondence points in relatively flat regions of the human body, such as the back, chest, and abdomen.

Recently, Chu et al. [17] proposed a global alignment and stitching method for multi-view point clouds using 2D SIFT (scale-invariant feature transform)-based feature points. This approach extracts SIFT features from multiple camera images and matches them to 3D point cloud coordinates, demonstrating robust alignment results even in repetitive structures or complex scenes. However, it can only be effectively applied when sufficient texture or repetitive patterns are present.

Additionally, neural implicit representation-based registration methods have emerged. NeRF (neural radiance fields) and NICE-SLAM [18] can model input data as continuous functions, maintaining structural consistency of the entire scene in high-dimensional embedding space while minimizing local feature loss. This neural network-based approach helps overcome the limitations of traditional discrete descriptors, contributing to fast real-time processing and high-quality 3D reconstruction, although it entails high demands for large-scale parameters and dependence on training data.

Among these methods, RANSAC and FPFH are robust against noise and computationally efficient, enabling effective feature-based matching during global initial registration. In this research, we leverage these characteristics to first perform global registration using RANSAC and FPFH, followed by local refinement using the ICP algorithm. This procedure significantly enhances the precision of the final 3D model while ensuring both the stability of the initial registration and the accuracy of local optimization.

2.1.2. Precision Refinement: Limitations of Point-to-Point and Surface-Based Approaches

The ICP algorithm [19] is a representative method for the fine registration of point clouds. Traditional point-to-point ICP iteratively finds the nearest points between two point clouds and computes a rigid transformation to minimize the sum of squared distances between the points. However, this approach has critical limitations, including slow convergence speed, susceptibility to becoming stuck in local optima, and the potential to converge in entirely different directions when the initial registration is inaccurate.

Go-ICP [20] stated that “ICP can only guarantee convergence to local minima due to its iterative nature,” and introduced branch-and-bound-based global optimization to address this issue. Low et al. pointed out that ICP often becomes trapped in local minima close to the optimal solution and proposed multi-resolution surface smoothing as a potential solution. However, these methods also significantly increase computational costs, making them unsuitable for real-time applications such as in healthcare.

To overcome these problems, point-to-plane ICP was proposed, which achieves significantly faster convergence rates and higher accuracy by minimizing the perpendicular distance between points and tangential planes. Rusinkiewicz et al. [21] demonstrated that the point-to-plane approach performs excellently on data rich in surface information, with convergence speed improving several times when normal vectors can be reliably estimated. Furthermore, plane-to-plane ICP [22] utilizes plane information from both source and target point clouds to perform surface-normal guided registration. This approach considers the local planar structure of both point clouds simultaneously, providing a broader geometric context than point-wise correspondences and increasing the potential to avoid local optima.

Förstner [23] theoretically demonstrated that efficient and accurate motion estimation is possible from plane-based correspondences. Chen et al. [24] empirically showed that plane-based alignment can achieve high accuracy and robustness in structured environments, such as building facades, as well as in shapes exhibiting partial plane characteristics, such as human surfaces, using real point cloud data. In the same study, they utilized the PLADE (plane-based descriptor) to demonstrate that plane information is effective in 3D feature representation, proving that it enables stable alignment in relatively flat areas of the human body, such as the back, chest, abdomen, and thighs.

2.1.3. Applying Vertex Reduction After ICP Registration

Vertex reduction in point clouds is typically performed during the preprocessing stage for the purposes of operational efficiency and data light weighting. However, recent studies have increasingly applied vertex reduction in the post-processing stage after registering (aligning) point clouds from multiple viewpoints. Efficiently simplifying the data after registration allows for the effective removal of redundant areas and unnecessary vertices, while preserving geometric features (such as curvature and edges) and maintaining accuracy.

Lawin et al. [25] employed a density-adaptive point set registration technique, conducting ICP-based alignment on multi-view data with differing densities, followed by post-processing downsampling to correct observed density differences in the aligned results. In terms of feature preservation, Potamias et al. [26] proposed a vertex reduction method that selects salient points based on learned features of the point cloud’s structural characteristics (such as edges and curvature), demonstrating that high simplification rates can still achieve excellent shape preservation and geometric consistency. Additionally, Xueli Xu et al. [27] reported a case where a feature-preserving mesh simplification technique was applied in the post-processing stage in densely aligned 3D microscopy data, maintaining the quality of the final model.

Post-processing vertex reduction, especially in the context of integrated point clouds after ICP registration, serves as a tool to flexibly adjust the trade-off between data quality and operational efficiency according to needs. For example, in medical settings, regions that require high precision (e.g., areas where surface curvature changes rapidly) can minimize reduction, while flatter areas can be aggressively simplified. This strategy reduces the overall data volume while effectively preserving essential information.

2.2. Deep Learning-Based 3D Reconstruction: Fundamental Limitations in the Healthcare Data

Deep learning-based 3D reconstruction methods have been rapidly evolving. PointNet-based matching networks (PointNetLK, DCP, and PCRNet) and Transformer-based multi-view fusion models are representative examples, demonstrating impressive performance through training on large datasets.

Notably, PointNetLK [28] combines the PointNet architecture with Lucas-Kanade optimization to implement robust rigid registration between two 3D point sets. The advantages of PointNetLK include direct and fast registration without using RANSAC, as well as excellent noise robustness inherent in the PointNet framework. However, its optimization performance may degrade in clinical data or highly noisy environments, and it has a significant dependency on large training datasets.

DCP (deep closest point) [29] incorporates an attention mechanism to enable fine correspondence generation and transformation estimation between two point clouds. This model guarantees robust performance in complex transformation situations and is adaptable to various environments, but it also suffers from a complex network structure and increased training and inference times. Additionally, like PointNetLK, DCP requires sufficient annotated large-scale data to achieve optimal performance.

PCRNet [30] operates by incrementally increasing registration precision through a recurrent neural network (RNN) structure integrated with PointNet. The main advantage of PCRNet is that it exhibits rapid convergence and robust registration performance even with a relatively small network. However, it may be vulnerable to convergence stability and errors in cases of high data complexity or significant noise.

As highlighted, while deep learning-based 3D reconstruction demonstrates excellent registration performance in large general datasets, it faces fundamental limitations in the medical data environment. First, there is the issue of data scarcity. Due to privacy regulations and high collection costs, it is extremely difficult to secure the substantial amounts needed for large-scale training in medical data. A comprehensive review by Chen et al. [31] identified data scarcity and labeling costs as significant obstacles to deep learning in medical imaging, especially pointing out that annotation work is even more complex and time-consuming for 3D data. The research by Xiao et al. [32] noted the inaccuracies and noise problems in depth-based motion capture data, emphasizing the need for additional training data to correct these issues, which is challenging to obtain in medical settings.

Second, there is the challenge of shape diversity and generalization. Even for the same patient, subtle differences in posture, body shape, and capturing conditions can significantly hinder the generalization of the learned models. In medical applications, constructing training datasets that cover various body types (e.g., obese, muscular, underweight), ages (e.g., pediatric, adult, elderly), and posture variations is virtually impossible. Research by Guan et al. [33] systematically analyzed the domain adaptation issues of medical deep learning models, reporting a sharp decline in performance on new patient data with distributions different from the training data.

Third, ethical and security constraints pose significant challenges. There is a risk of patient data being leaked during the deep learning model training process, as well as concerns about the ability to trace back original data from the trained models. Furthermore, the black-box nature of these models makes it difficult to provide the interpretability and decision-making transparency required in medical practice, which can pose significant obstacles in the regulatory approval process for medical devices.

2.3. The Contributions and Approach Methods of Our Paper

This research aims to construct an accurate 3D human model from four-directional medical depth maps, featuring structural distinctiveness compared to existing studies. We propose a hierarchical registration pipeline using RANSAC-FPFH-Plane ICP and adopt plane-to-plane ICP-based precision registration instead of the conventional point-to-point ICP method. The plane-to-plane approach is particularly suitable for medical depth data, as it utilizes surface normal information to achieve faster convergence rates than point-to-point methods, thereby reducing processing time required in clinical workflows. Additionally, plane information provides a broader geometric context than point information, decreasing the likelihood of becoming trapped in local optima, and allows for quick and stable convergence to the global optimum when the initial registration obtained from the four-directional fixed capture is relatively good.

Especially for body parts with strong planar characteristics, such as the back, chest, abdomen, and thighs, plane-to-plane correspondences are significantly more stable and accurate than point-to-point correspondences. By explicitly considering the surface normal consistency between viewpoints in the four-directional fixed capture environment, the registration quality across viewpoints can be further improved. Moreover, this methodology operates purely based on geometric principles without relying on large-scale training data or external data, fundamentally circumventing the limitations of medical data, such as data scarcity, ethical constraints, and difficulties in generalization. Each step of the algorithm is clear and interpretable, ensuring the verifiability and reliability required in medical device regulatory approval processes.

Through this approach, this research presents a clinically applicable 3D human reconstruction method that simultaneously attains the accuracy, stability, interpretability, and practicality required in medical environments without the need for complex deep learning models.

3. Proposed Method

3.1. System Overview

The 3D human posture analysis system proposed in this study operates on depth maps generated under controlled conditions and consists of a multi-stage pipeline that extracts high-quality 3D meshes and spinal skeletal information from depth images. The depth maps used in this study were generated using data obtained from the SizeKorea (Seoul, Republic of Korea) database, which is a nationally managed anthropometric survey that collects and provides standardized high-resolution 3D human body models [34]. The human body dimensions survey is measured periodically every five years and is conducted for people aged 20 to 69. The data for this study were data from the 8th Human Dimension Survey 2020 to 2023.

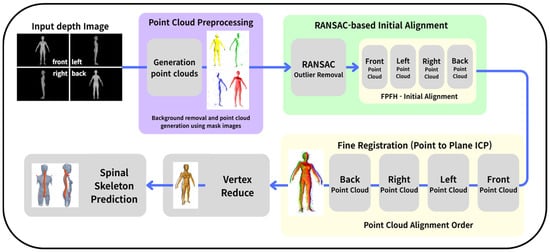

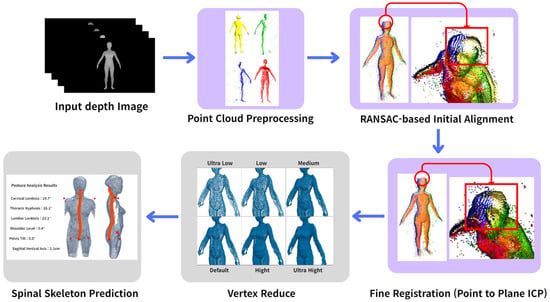

Figure 1 shows the overview of proposed method. The system first receives depth images from four directions (front, left, right, and back) to generate 3D point clouds for each view. In this process, a mask image is applied for background removal, and points are generated according to the unique coordinate systems of each view. Since the point clouds generated from multiple views possess different local coordinate systems, a registration process is essential to integrate them into a single global coordinate system. This system adopts a two-step registration strategy. The first step is global registration, which combines the RANSAC (random sample consensus) algorithm with the FPFH (fast point feature histograms) feature descriptor. The second step utilizes the ICP algorithm for fine registration. After the global initialization, we incorporate a quality-driven feedback mechanism that quantitatively assesses geometric consistency among the aligned views and automatically re-runs the alignment with adjusted parameters when the quality is insufficient. After initial registration, the point-to-plane ICP algorithm is applied to achieve fine registration. The registration process proceeds in the order of side views (left and right) followed by the back view, structured to minimize cumulative errors by aligning in the order of higher view overlap.

Figure 1.

System flow of proposed method.

Once the registration is complete, the point clouds are merged into a unified point cloud, which is then optimized into a six-level LOD (level of detail) model through a quadric error metrics-based vertex reduction algorithm. An ensemble technique is applied to independently extract spinal skeletal information from each LOD model. In this process, AI-based landmark detection is combined with anatomical proportions to estimate 17 key joint points and compute spinal angles. The spinal skeletal information predicted from the six LOD models is integrated using a voting method, effectively eliminating noise due to resolution differences by selecting the most frequently occurring coordinate for each joint point. This multi-resolution-based ensemble strategy enhances the robustness and accuracy of spinal skeletal predictions compared to a single model.

3.2. Preprocessing: Depth Map Analysis and Point Cloud Generation

This system receives depth images from four directions (front, left, right, and back) to generate 3D point clouds. The depth images are provided in bmp format as grayscale images, where the brightness value of each pixel represents distance from the camera information.

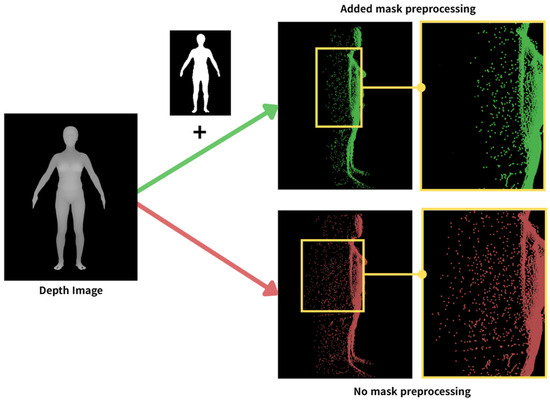

As can be seen in the no mask preprocessing example in Figure 2, directly converting the depth image to a point cloud resulted in excessive measurement noise, leading to significant distortion along the edges of the point cloud. To address this issue, this study introduced a mask-based preprocessing step to finely extract the foreground regions from the depth image. This allows for the proactive removal of unnecessary background points and sensor-induced noise, facilitating stable point cloud reconstruction.

Figure 2.

Difference in extracted point cloud with mask/no mask.

First, the input depth map is represented with integer values ranging from 0 to 255, but for numerical stability in subsequent processing, it is normalized to floating-point values in the range of 0.0 to 1.0. An adaptive mask generation method based on double thresholding is applied to efficiently separate the foreground (the human body) from the background. The lower threshold of 0.2 removes sensor noise and overly close areas, while the upper threshold of 0.95 filters out regions corresponding to the background and depth measurement limits.

The generated binary mask undergoes morphological opening and closing operations using elliptical structural elements, which helps eliminate residual noise and naturally refine the outline of the human body. The depth map with the refined mask is then transformed into a 3D point cloud using an inverse projection algorithm based on the pinhole camera model. A KD-tree-based hybrid neighbor search is conducted to extract up to 30 neighboring points within a 5 mm radius around each point, and principal component analysis (PCA) is applied to this local patch to estimate the normal vectors. The eigenvector corresponding to the smallest eigenvalue is chosen as the normal direction, and this high-quality normal information significantly enhances the precision of the subsequent point-to-plane ICP registration process.

3.3. FPFH Feature Descriptor Extraction

The ICP algorithm updates the nearest correspondences between two point clouds iteratively to optimize the transformation (rotation/translation). Consequently, due to the convergence characteristics of the algorithm, the initial pose is a key factor determining the overall registration quality. ICP is structured such that its objective function is nonlinear and easily converges to local minima. If the initial registration is inaccurate or if the relative distance between the two point clouds is significant, it continuously matches incorrect correspondences, leading to the accumulation of misalignments. Especially in structures with significant curvature changes, such as the human body, an inadequate initial pose can greatly distort the relative positions of arms, legs, and the torso, making it virtually impossible to recover in subsequent optimization iterations.

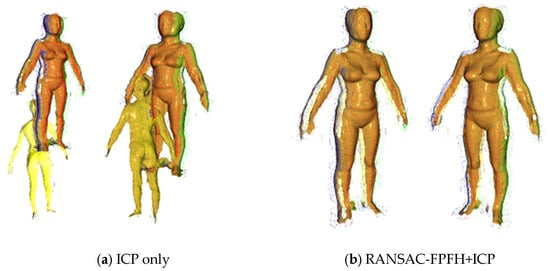

For this reason, fine registration using ICP must be conducted under conditions where a stable initial pose is ensured. As can be seen in Figure 3, applying ICP without initial registration can lead to misalignments that geometrically distort or overlap the overall shape by becoming trapped in local optima.

Figure 3.

Comparison of reconstruction quality with and without the proposed RANSAC-based initial registration. For comparison, the baseline uses point-to-plane ICP only. Different colors denote depth maps acquired from different viewing directions (front, back, left, and right).

To prevent this, the current study stabilizes the initial pose using global registration based on RANSAC-FPFH and then performs fine registration using point-to-plane ICP. To address this, the system utilizes RANSAC (random sample consensus)-based FPFH (fast point feature histogram) feature matching to achieve global initial registration, followed by fine registration through the point-to-plane ICP algorithm. This combined approach secures global exploration capabilities during initial registration and achieves high registration accuracy through local optimization in the fine registration phase.

3.3.1. Depth Normalization and Mask-Based Point Cloud Generation

The FPFH (fast point feature histograms) is a structurally robust local feature descriptor that effectively addresses issues such as partial observations, curvature discontinuities, and depth sensor noise that inevitably arise in human-based point cloud registration. By applying a center-point-based single accumulation structure, FPFH eliminates the excessive computational load of the higher-dimensional descriptor (PFH), which computes the relationship among all pairs of neighboring points, while reliably preserving the core geometric information of relative normal distribution.

The feature compression structure of FPFH effectively suppresses noise propagation commonly encountered in human data and offers a relatively uniform expression even in areas where curvature changes and quasi-planar structures coexist, such as at joints and the torso. Additionally, its low computational cost allows for near real-time processing speeds in this pipeline, which requires continuous processing from four viewpoints (front, back, left, right), providing a practical advantage. Consequently, FPFH is selected as the fundamental component of local feature descriptors.

3.3.2. Hierarchical Registration and Supplementary Design Framework

The system combines RANSAC–FPFH-based initial registration (initialization) with a hierarchical adaptive design that reflects the viewpoint-specific characteristics of the data and practical operational constraints. This integration ensures both robustness and efficiency in point cloud registration.

First, to address the varying point density and occlusion patterns depending on the viewpoint, an adaptive voxel downsampling technique was applied. Voxel sizes of 5.0 mm for the left and back views and 3.0 mm for the right view were established. A multi-scale progression approach was introduced to gradually converge from global registration to fine registration. Specifically, scale stages of [25.0, 12.0, 6.0] mm for the left and back views and [10.0, 5.0, 2.5, 1.0] mm for the right view were designed to enable stable convergence from the global contour to local details. This multi-scale structure allows for comprehensive representation of the overall shape in the initial stages while supporting the refinement of local registration in subsequent steps.

Additionally, the rotation degrees of freedom were constrained based on the viewpoint to minimize misregistration that can occur during the registration of symmetrical bodies. A limited small-angle rotation was permitted for the left and back views to ensure registration stability, while a broader rotation range was allowed for the right view, where pose variations during data collection are relatively larger, thereby expanding the convergence domain.

During the RANSAC phase, a fitness threshold was established, and if the inlier ratio did not meet a certain level, the process automatically proceeded to the next scale stage. When sufficient matching quality was achieved, early termination was implemented to reduce unnecessary sampling. This conditional progression was designed to minimize computational load while maintaining registration quality.

To improve robustness against occasional failures of global initialization under occlusion, noise, or challenging body poses, we introduce a quality-driven feedback mechanism that evaluates the geometric consistency of the initially aligned point clouds before proceeding to downstream steps. After initial alignment, we compute an alignment quality score based on the mean nearest-neighbor distance between sampled points across each aligned view pair. Specifically, for a pair of aligned point clouds, we measure the mean nearest-neighbor distance and convert it into an overlap quality in the range [0, 1] by normalizing with the expected body size. The final score is obtained by averaging the overlap quality over all view pairs.

If the alignment quality score falls below a threshold (set to 0.4 in our experiments), the pipeline automatically triggers an adaptive refinement loop that re-invokes the alignment module with modified settings (e.g., increased RANSAC iterations or alternative ICP strategies) and re-evaluates the result using the same metric. This loop is fully automated and implemented as modular functions (assess_alignment_quality and apply_adaptive_refinement), ensuring that only geometrically consistent reconstructions are passed to mesh generation and LOD ensemble skeleton analysis.

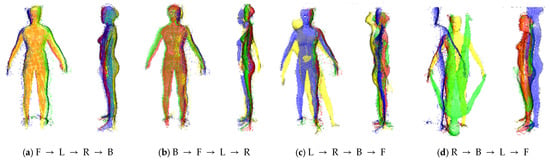

3.3.3. Importance of Registration Order

The registration order significantly influences the overall registration quality based on the viewpoint characteristics and shape overlap of each view. In this study, an appropriate registration sequence was established for the multiple input point clouds. As shown in Figure 4, applying the correct order allows the four viewpoints to be stably aligned into a single coherent shape; however, if the order is reversed, the relative positions of the front, side, and back point clouds become distorted, leading to serious mismatches or overlapping errors. This occurs because errors from the initial registration phase propagate to subsequent views, and particularly in human data with many partial observations, the impact of order selection becomes even more pronounced.

Figure 4.

Comparison of output results by registration order. F, B, R, and L denote the front, back, right, and left views, respectively. (a) Result with the correct order; (b–d) results with incorrect orders. Colors indicate the corresponding views.

To minimize this error propagation, this study adopted a gradual registration procedure of front, left/right side, and back. The front view was prioritized for several reasons: it most clearly represents the center axis of the human body and provides stable structural reference points that define bilateral symmetry, such as shoulder width, hip width, and thoracic contours. Additionally, the front view tends to have superior sensor field of view and observation quality, making it the most suitable reference.

Subsequently, the left and right sides are sequentially aligned to the previously established front-based target to enhance the transverse cross-section structure of the human body, and finally, the back point cloud is aligned to complete the overall shape. This order is designed to perform registration starting from the areas with the highest overlap between views to suppress cumulative errors, ensuring that the lower overlapping back view is minimally affected by initial errors.

3.4. Fine Registration (Point-to-Plane ICP)

The objective of this stage is to minimize the remaining positional and orientational discrepancies after the global initial registration (RANSAC–FPFH) by aligning them to the local surface geometry. Since human data features extensive quasi-planar or low-curvature regions, such as the thoracic spine, scapula, and pelvis, an accurate fine registration algorithm is essential.

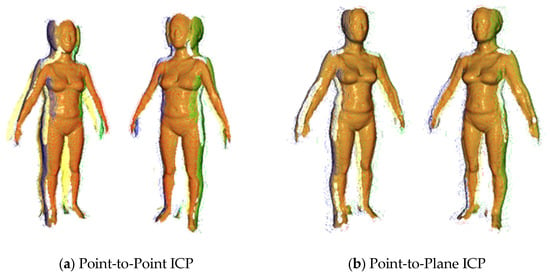

Figure 5 shows the comparison of the performance of point-to-plane ICP and point-to-point ICP by replacing only the cost function under the same initial global registration and the same correspondence update procedure. In the full-body registration scenarios, point-to-plane ICP consistently outperformed point-to-point ICP in several respects.

Figure 5.

Comparison of output quality between point-to-point ICP and point-to-plane ICP after the RANSAC-based initial registration. Colors indicate depth maps acquired from different viewing directions (front, back, left, and right).

In this stage, RMSE (root mean square error) and fitness score are used to quantitatively evaluate the performance of the ICP algorithm. RMSE is the most widely used metric for measuring alignment accuracy between two point clouds, quantifying the average distance error between the aligned point cloud and the reference data. The fitness value ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating that many correspondences between the two point clouds match. Particularly for partially overlapping point clouds obtained from medical depth maps, fitness directly reflects the ratio of valid correspondences contributing to the alignment process, making it essential for assessing the reliability of the alignment.

Prior studies have comprehensively evaluated alignment results by using both RMSE and fitness together. RMSE measures the precision of the alignment, while fitness measures the reliability of the alignment, allowing for an objective assessment of the overall performance of the alignment algorithm. This is particularly advantageous in medical applications, such as this study based on geometric alignment, as it enables the evaluation of pure geometric performance without the bias of artificial training data, thereby ensuring clinical reliability.

As shown in Table 1, in the combination of front and left views, both methods exhibited similar performance (RMSE: 4.3246; fitness: 0.6715). However, in the combination of front and right views, point-to-plane ICP slightly improved the RMSE from 1.6576 to 1.6528. The most notable difference occurred in the combination of front, left/right, and back views, where point-to-plane ICP reduced the RMSE from 5.2462 to 4.5653, approximately a 13.0% decrease, while simultaneously improving the fitness value from 0.8024 to 0.8416, an increase of about 4.9%. This result clearly illustrates the effectiveness of normal direction constraints in complex scenarios with significant cumulative errors, such as back registration.

Table 1.

Numerical comparison with point-to-point ICP and point-to-plane ICP (the lower the value, the better the performance, and the higher the ICP fitness, the better the performance).

These findings align with the theoretical characteristics whereby point-to-point ICP is sensitive to slight sliding errors in the surface tangential direction due to isotropic distance minimization, while point-to-plane ICP utilizes geometric constraints in the surface normal direction to directly suppress residuals and expand the convergence domain. Additionally, the dataset exhibits positional noise for individual points due to the characteristics of the depth sensor; however, normals are estimated through local averaging, making them relatively stable. For these reasons, the fine registration algorithm in this process was adopted as point-to-plane ICP. The statistical significance of these differences is further validated using paired statistical tests in Section 4.3.

3.5. Adaptive Vertex Reduction

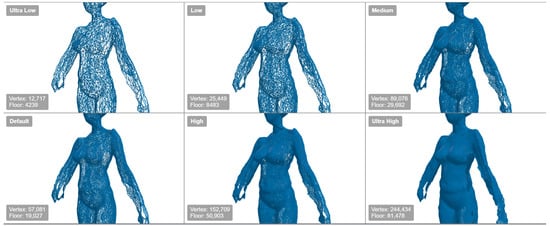

This stage focuses on adjusting computational costs and resolution according to demands while preserving the shape fidelity of the human mesh after preprocessing and registration. It minimizes shape distortion and volume deviation by combining adaptive decimation reflecting curvature, surface density, and anatomical importance with step-wise normal recalculation and smoothing. The six levels of detail (LOD) generated from the same original source form a subset hierarchy that ensures consistency in coordinate systems, boundaries, and normals across resolutions. Figure 6 shows the example of vertex reduction results by LOD.

Figure 6.

Examples of meshed images by LOD.

Adaptive vertex reduction removes degenerate, duplicate, and abnormal elements, recalculates normals, and secures a normalized input mesh, subsequently reducing the number of vertices step-by-step to meet target retention rates. The quality-prioritized path utilizes precision reduction with boundary preservation and low tolerance to minimize surface distortion and volume deviation. The speed-prioritized path achieves the same goal by dividing it into five short steps to enhance throughput. By opting for step division over a single substantial reduction, cleanup and normal correction are immediately performed at the end of each step to suppress local collapse, silhouette loss, and non-manifold remnants. After reduction, lightweight smoothing and post-processing are applied to alleviate fine jaggedness and noise, ensuring the stability of sensitive contours and joint silhouettes in skeleton estimation and measurement. The pipeline operates consistently in the order of preprocessing, reduction, intermediate cleanup, normal correction, and smoothing. Table 2 summarizes the reduction rates of the six LODs produced in this stage.

Table 2.

The rate of vertex reduction depends on LOD (reduction rate was calculated in comparison with the original).

This stage is introduced to simultaneously satisfy three demands. First, anatomical areas such as near the spine, joint contours, and feature edges must be protected throughout the reduction process, combining conservative reduction in the quality-prioritized path with step-wise smoothing and normal recalculation to minimize shape distortion. Second, since the size and noise characteristics of input meshes can vary significantly in real-world applications, a complexity-aware policy automatically determines retention rates and post-processing intensity to consistently maintain output quality and processing times amid data diversity. Lastly, different resolution requirements coexist for the same subject, including analysis, real-time inference, streaming, and storage; thus, standardizing the six LODs in Table 2 and maintaining a subset hierarchy obtained by further simplifying higher results ensures consistency in coordinates, boundaries, and normals during resolution transitions. Consequently, this adaptive reduction achieves accuracy, efficiency, and consistency, enhancing the robustness of succeeding modules and the operational efficiency of the entire pipeline.

3.6. Estimating Skeleton Based on Multiple LOD Ensembles

The spinal skeleton is automatically estimated through a 3D human mesh categorized into six levels of detail (LODs). The proposed skeleton estimation module consists of the following steps:

- Initializing 3D joints using AI-based 2D pose landmarks;

- Predicting independent skeletons from each LOD mesh;

- Determining the final skeleton through median-based ensemble voting.

The initial joint coordinates of the skeleton are derived from 2D pose landmarks extracted from a frontal image. The frontal depth map is fed into the pose estimation model of MediaPipe Pose to detect full body key points, including the shoulders, elbows, wrists, pelvis, knees, and ankles. Among these, key points that directly contribute to spinal alignment and disk risk assessment are selected, including the head, neck, upper spine, middle spine, lower spine, and both shoulder and pelvic joints, defining the basic skeleton structure.

The initialized 3D joint coordinates are refined independently within each of the six LOD meshes. Neighboring vertices around the joint candidates are collected using KD-tree-based nearest neighbor searches, and the curvature and normal distribution of the local patch are analyzed to fine-tune the joint positions to conform with the body contour and anatomical orientation.

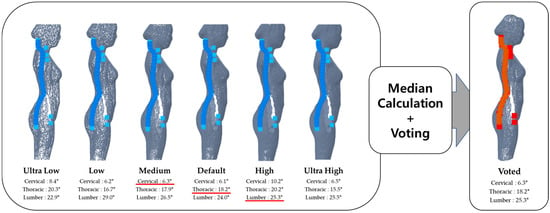

The final selected joint points are connected in the order of neck, upper spine, middle spine, and lower spine to form the spinal centerline, while the 3D curvature angles of the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar regions are calculated through the dot product of adjacent segment vectors. The spine is divided into three anatomical regions using anatomical ratio-based landmarks. The vertical distance between the C7 point—corresponding to the base of the cervical spine—and the sacral promontory is defined as the effective spinal length. Based on this length, the top 20% interval is classified as the cervical region, the 20–50% interval as the thoracic region, and the 50–80% interval as the lumbar region. This proportional division method absorbs absolute length variations due to individual height and body shape differences while consistently reflecting the physiological positions of spinal curvature reported in the literature. Each segment angle is also calculated individually across the six LODs, then the value closest to the median is adopted as the final value, minimizing estimation deviations of spinal angles due to differences in resolution and mesh reduction.

The skeleton is estimated by integrating the independently predicted joint candidates from different LODs through a median-based ensemble voting approach (Figure 7). There are differing characteristics between the ultra-low and ultra-high LODs regarding quantization bias, surface smoothing degree, and noise sensitivity. In the ultra-low LOD, the mesh resolution is significantly reduced, maintaining the overall body contour while losing detailed structure, which decreases the accuracy of joint position estimation. In contrast, the medium LOD strikes a balance between structural stability and detailed shape representation but may show insufficient local representation at certain joints. The high and ultra-high LODs reflect fine shapes excessively, leading to high precision; however, they are overly sensitive to noise and local misalignments, which increases the likelihood of encountering outlier joint angles. These characteristics suggest that simply increasing the LOD resolution does not necessarily lead to improved estimation accuracy. Therefore, this study adopted a median-based ensemble voting strategy to leverage the advantages of independently predicted joint candidates from different LODs while compensating for their disadvantages, ultimately estimating the final skeleton.

Figure 7.

LOD-wise variation in joint-angle estimation and the median-based voting result. Blue and red are used for visualization only. Underlined values indicate the angle selected by voting.

The purpose of introducing the multi-LOD ensemble is to mitigate local bias errors and ensure consistency in joint estimation across variations in resolution. Table 3 quantitatively evaluates how much the proposed median-based voting strategy reduces the inter-LOD deviation compared to average interpolation. In the cervical and lumbar regions, the median-based voting significantly reduced the angular deviation compared to the mean value (0.1131° vs. 0.9897° for cervical and 0.0894° vs. 0.2401° for lumbar), while maintaining a level of consistency similar to the mean-based approach in the thoracic region. Here, the deviation refers to the mean absolute difference (i.e., the mean absolute deviation) between each LOD candidate and the final result, with smaller values indicating higher geometric stability (inter-LOD consistency) of joint estimation across different resolutions.

Table 3.

Ensemble voting: median vs. mean deviation analysis.

Average interpolation generates virtual coordinates that were not actually observed at any LOD and reflects the inherent noise and bias present at the LOD level. In contrast, the median-based voting approach selects only candidates closest to the central tendency of actual predictions, thus suppressing the influence of outliers and preserving real anatomical structures that have been observed on the mesh surface multiple times. Consequently, the proposed voting strategy enhances the robustness and reliability of spinal curvature estimation by compensating, integratively, for the structural biases arising from different LODs.

The reasons for adopting a multi-LOD ensemble are threefold. First, local quantization and smoothing biases that arise during mesh reduction can lead to skewed joint positions when using only a single resolution. By independently estimating joints across different LODs and selecting the actual value closest to the central tendency, systematic errors can be reduced through the offsetting of LOD-specific biases. Second, uniformly sampling (50,000 points) and applying standardized normal estimation parameters (radius = 5; max_nn = 30) normalize the input distribution across LODs, ensuring homogeneity in point and normal statistics and compensating for the under-sampling or over-sampling of certain LODs with predictions from others. Third, using frontal image-based landmarks as a global guide helps reduce initial uncertainties in point-based 3D estimation and encourages multiple LOD candidates to converge under a common anatomical reference.

Choosing “the actual prediction closest to the central tendency” instead of direct average coordinates in voting is intended to exclude unrealistic interpolated coordinates, assuming that the internal estimator already satisfies geometric constraints such as relative length and angles between joints, thus maintaining only actual mesh-based solutions. The computational complexity increases linearly with the number of LODs; however, by processing each LOD path in parallel or in batches, the overall computational time can be efficiently managed. The visualization results are generated in a common coordinate system, making it easy to compare overlays between LODs, and when combined with the LOD hierarchy defined in Section 3.5’s adaptive vertex reduction, it functions as a key module supporting real-time inference, precise analysis, and long-distance visualization.

3.7. Body Shape Analysis According to Spinal Angle

This study aims to quantify the risk of cervical and lumbar disks by utilizing metrics that reflect the body’s posture and balance from the extracted skeleton. To quantify disk risk, key body points are extracted using MediaPipe Pose, and the angles and ratios calculated from these coordinates are used to assess the risk of neck and back disk injuries. To evaluate disk risk, a clear definition of body metrics is necessary. Therefore, this study rigorously defines six variables (cervical lordosis angle, thoracic kyphosis angle, lumbar lordosis angle, shoulder levelness, pelvic angle, and spinal registration) that directly map to the scoring rules of ISO 11226 (static posture of workers) [35] and RULA/REBA [36] behavior-level scoring, performing posture-based disk risk diagnostics based on these quantified results.

The justification for adopting ISO 11226 and RULA/REBA as criteria lies in their complementary roles as an international standard (ISO) and a practical field tool (RULA/REBA). ISO 11226 systematically defines angular postures of the head, neck, and torso, static holding times (holding/recovery), support status, and left–right symmetry (tilt–rotation), allowing for the definition of posture-induced loads acting on the lumbar and cervical disks and deriving risk indicators (i.e., normal, caution, and risk) across angle intervals [37]. RULA/REBA, through a total of four levels of action ratings that integrate posture, load, frequency, and coupling information, provides a tool that scores postures such as “leaning forward,” “tilting to the side,” and “twisting the torso,” presenting posture risk levels while assigning situational weighting above the absolute permissible criteria provided by the ISO [38].

Thus, according to the principles of ISO 11226 and RULA/REBA, if the angle of “leaning forward” for the neck and torso exceeds approximately 20°, or if there is a pronounced “tilt to the side” or “twisting” (asymmetry between shoulders and pelvis) in the frontal and rear views and an increase in global registration (SVA), the action level is escalated, and posture ratings are refined [39]. This dual assessment structure allows for the objective evaluation of neck and lumbar disk risks using only 2D key points extracted from frontal, rear, and side images, applying standards-compliant rules and providing grounded indicators for normal/caution/risk across angle intervals.

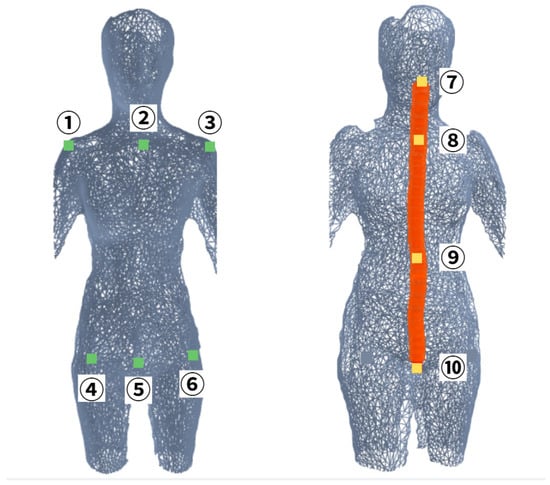

ISO 11226 describes the posture-induced mechanical loads on the neck and lumbar region based on angles (head/neck, torso), static holding times, support status, and left–right symmetry, while RULA/REBA scores forward flexion, lateral tilt, and torso twisting, as well as load, frequency of repetition, and object handling status (coupling) to indicate the urgency of interventions. Based on these definitions, this study selects six variables necessary for evaluating neck and lumbar disks: cervical lordosis angle, thoracic kyphosis angle, lumbar lordosis angle, shoulder angle, pelvic angle, and sagittal vertical axis. Based on the defined variables, calculations for each variable are based on the MediaPipe key point. Figure 8 shows the key points of the body that are utilized in the variables. The calculation formula and definition of the variables are set as follows.

Figure 8.

Anatomical locations of key point landmarks on the 3D body model (1: right shoulder (); 2: shoulder center (); 3: left shoulder (); 4: right hip (); 5: hip center (); 6: left hip (); 7: neck; 8: upper spine; 9: middle spine; 10: lower spine). Colors are used for visualization purposes only.

- Cervical Lordosis Angle ()

The cervical lordosis angle is approximated using neck flexion, defined as the difference between the trunk flexion angle (α) and the head flexion angle (β). The values of α and β are given by Equations (1) and (2), respectively, and the cervical lordosis angle is derived using their difference as shown in Equation (3). Therefore, the larger the angle, the more pronounced the loss of cervical lordosis and forward head posture become, which directly maps to the neck flexion item in ISO and the neck forward angle score in RULA [40]. represents the vertical reference vector, and as increases, the cervical lordosis decreases, which directly corresponds to the neck flexion item in ISO and the neck forward angle score in RULA.

- Thoracic Kyphosis Angle ()

The thoracic kyphosis angle is approximated using the upper and lower trunk segment angles. It is calculated as the angle between the vector directed from the midpoint of the shoulders to the ear and the vector directed from the midpoint of the shoulders to the hip joint midpoint, as shown in Equation (4). A larger value is interpreted as a tendency toward hyperkyphotic. As increases, the thoracic kyphosis deepens, bringing the posture closer to a kyphotic posture [41].

- Lumbar Lordosis Angle ()

The lumbar lordosis angle is approximated using the thoracolumbar–pelvic segment angle. It is calculated as the angle between the vector directed from the hip joint midpoint to the shoulder midpoint and the vector directed from the hip joint midpoint to the knee midpoint, as shown in Equation (5). A smaller value of indicates a tendency toward loss of lordosis or a flat back posture [42].

- Shoulder Angle ()

Shoulder levelness is calculated as the angle between the line connecting the left and right shoulders and the horizontal line, as shown in Equation (6). The indicators for the shoulders and pelvis (Equations (6) and (7)) quantify coronal plane symmetry violations (lateral bending/twisting) and are used as scoring items for lateral bending and twisting in RULA/REBA [43].

- Pelvic Angle ()

Pelvic tilt (obliquity) is calculated as the angle between the line connecting the left and right hip joints and the horizontal line, as shown in Equation (7).

- Sagittal Vertical Axis (SVA)

The spinal alignment is measured using a photo-based sagittal vertical axis (SVA). It is calculated by normalizing the difference between the horizontal coordinate of the head reference point and the horizontal coordinate of the hip joint midpoint, scaled by the total body length, as shown in Equation (8) [44]. In this case, a larger SVA value indicates a greater deviation from vertical alignment of the entire body.

This calculation procedure allows for the consistent mapping of the criteria of “angles, static holding, and symmetry” from ISO 11226 and the principles of “situational weighting (forward bending, lateral tilting, twisting, and load/frequency/coupling)” from RULA/REBA, using only the 2D key points provided by MediaPipe. Each variable can then be combined with the defined angle ranges (normal/caution/risk) to serve as input indicators for diagnosing the risk of cervical and lumbar disks. Table 4 summarizes the normal/caution/risk ranges for spinal angles as defined in this study. To enable a structured interpretation of the extracted spinal indicators, this study adopts posture angle ranges derived from the principles of ISO 11226 and RULA/REBA. Within the context of depth-based, non-contact posture analysis, these ranges are utilized to describe relative postural tendencies and to facilitate the stratification of posture conditions into normal, caution, and risk categories. Given the inherent measurement variability and quantization uncertainty associated with depth sensors, the use of stratified angle ranges is intended to enhance robustness and interpretability at the posture risk level rather than precise angle estimation.

Table 4.

Criteria for risk of disks through extracted indicator value.

Accordingly, the criteria summarized in Table 4 provide a consistent reference framework for ergonomic posture screening and longitudinal monitoring, rather than absolute clinical decision boundaries. This represents a redefinition of the risk level ranges specified in ISO 11226 and RULA/REBA within the spinal coordinate system adopted in this experiment. Accordingly, based on these posture assessment principles, the following table presents screening-level angle ranges adapted for depth-based spinal posture analysis.

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Experimental Environment

The programming language used is Python version 3.10.18, and the main libraries include OpenCV for image processing; TorchGeometry, NumPy (≥1.21.0), and SciPy (≥1.7.0) for numerical calculations; Pillow (≥8.3.0) for image input/output processing; Open3D (≥0.15.0) for 3D data processing; and MediaPipe (≥0.8.9) for human pose recognition. All experiments were executed on CPU without GPU acceleration. The hardware configuration consists of an Intel Core i5-14600 CPU, 31GB of DDR5 system RAM (Intel, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and approximately 80 GB of disk space used for experiments. The input data comprises depth maps with a resolution of 512 × 512, sampled at every 4 pixels (step = 4), with a depth scale adjusted to 100. A 3D integrated model was generated by aligning point clouds from the left, right, and rear views based on the frontal view. The registration process consists of two stages: FPFH-based RANSAC global registration (global registration) and point-to-plane ICP-based fine registration (local refinement). The registration parameters for each view direction are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Registration parameters by view direction.

To ensure bilateral consistency and reproducibility, we apply identical registration parameters to the left and right side views by explicitly reflecting the anatomical bilateral symmetry of the human body. Since the left/right side views exhibit comparable geometric complexity and similar overlap/occlusion patterns, using a standardized RANSAC budget avoids view-dependent bias in hypothesis sampling and yields more consistent alignment outcomes. Accordingly, we set the RANSAC iteration count to 50,000 for both left and right views. In contrast, the back view is integrated after the side views, benefiting from the already-aligned lateral structure, which effectively reduces the transformation search space. Therefore, 30,000 iterations are used for the back view to maintain efficiency while preserving robust alignment performance. This symmetric parameter design im-proves bilateral consistency and enhances the stability and reproducibility of the overall pipeline.

During the FPFH + RANSAC alignment, the maximum correspondence distance was set to 2.5 times the voxel size, with a minimum required number of correspondences set to 3 and a confidence level relaxed to 0.95. In the ICP stage, the correspondence distances for each scale were set to 3.0 times the voxel size, with the number of iterations configured as follows: [150, 200, 250, 300]. For normal estimation, the radius was set to 2.0 times the voxel size, and the maximum number of nearest neighbors (max_nn) was set to 30. Additionally, to achieve fine registration with minimal rotation, small rotation ICP was applied, with maximum rotation angles for each scale set to [2.0°, 1.0°, 0.5°] and iteration counts as [30, 30, 60]. For regions with restricted rotation, translation-only ICP was performed, applying the following parameters: iteration counts of [20, 20, 30] and a correspondence distance coefficient of 1.5.

4.2. Prediction Results

Figure 9 visually illustrates the intermediate outputs generated at each stage according to the proposed system’s overall pipeline. Initially, unnecessary background is removed from the input four-direction depth images, creating independent point clouds for each viewpoint. Thanks to the mask-based preprocessing, the human outline is clearly delineated, and the fine surface shapes of regions such as the hands, feet, and head are extracted relatively stably.

Figure 9.

Intermediate output results by pipeline sequence. Purple shading denotes modules in the registration pipeline (point cloud generation/preprocessing, RANSAC-based initial alignment, and point-to-plane ICP refinement), while gray shading denotes the spinal-angle estimation pipeline (vertex reduction and spinal skeleton extraction for posture analysis).

In the RANSAC-based initial registration stage, a global registration initial value is formed among the point clouds of the four viewpoints based on FPFH feature matching. As shown in the figure, even with this initial alignment, the relationships between the body center axis and limb positions are largely consistent, and the overall body contour begins to integrate into a single structure. However, the head region exhibits somewhat unstable alignment at this initial stage due to complex geometric patterns caused by hair, contour variations, and the specular reflection in the depth images. This instability arises even though FPFH uses local normal-based features as the surface directionality of microstructures like hair is inconsistent.

In the fine registration stage, the point-to-plane ICP algorithm is applied to optimize the local correspondences among the point clouds more precisely. At this stage, the registration errors in complex curvature areas such as the head, shoulders, waist, and both arms are significantly reduced, and the slight displacements experienced in the initial stage are gradually corrected. In particular, the registration quality improves substantially in the top and temporal regions of the head, ultimately confirming that the entire body is seamlessly integrated into a coherent 3D shape.

This visual comparison demonstrates that the step-wise design of the system is effectively practical, with FPFH-based initial registration rapidly stabilizing the overall structure and ICP fine registration meticulously refining the detailed geometry.

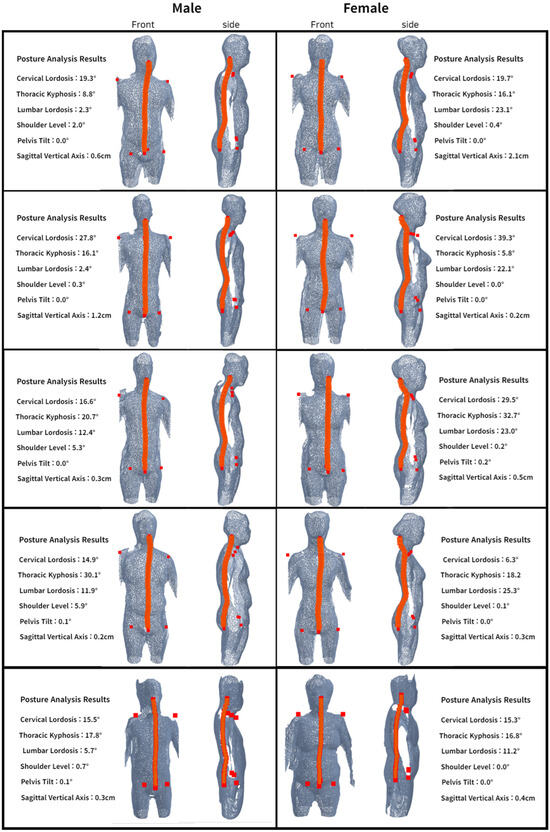

Figure 10 shows the reconstructed spinal centerline (in orange) and shoulder and pelvic reference lines by the proposed system for both male and female domains. The bottom row additionally includes subjects with obese body types, where the overall registration remains stable and the extracted reference lines remain visually coherent. In both the frontal and side views, the spinal centerline is naturally connected along the body’s central axis, and the symmetry of the shoulders and pelvis is stably maintained. Notably, in female subjects, the lumbar lordosis appears more pronounced due to body shape characteristics, while in male subjects, the curvature of the thoracic kyphosis is relatively gentle. These visual results demonstrate that the proposed system can reliably reconstruct the major anatomical axes (spine, pelvis, shoulders) of the human body, even with incomplete depth information from a single viewpoint.

Figure 10.

Results of proposed method for two domains (male/female), including subjects with obese body types (last row): The orange lines represent the spinal, pelvic, and shoulder skeletal lines.

Additionally, each visualized model presents detailed angular measurements of the spine, allowing for quantitative comparisons of cervical lordosis, thoracic kyphosis, lumbar lordosis, shoulder levelness, pelvic tilt, and sagittal vertical axis (SVA) for each subject. These measurements were evaluated against the normal body shape standards in Table 4 to assess postural registration.

The results show that most subjects fell within the ranges of cervical lordosis of 20–35°, thoracic kyphosis of 20–40°, and lumbar lordosis of 40–60°, classifying them as normal body shapes. However, some female subjects exhibited lumbar lordosis angles above 40°, indicating a tendency towards lumbar hyperlordosis, while some male subjects showed thoracic kyphosis angles below 10°, presenting a flat thoracic posture. Despite these variations, all subjects maintained shoulder levelness and pelvic tilt within 2° or less, indicating good left–right balance, with an average SVA of 1.1 cm, which is within the normal standard of <4 cm.

These findings suggest that the proposed system effectively utilizes four-direction depth maps to robustly address surface noise and viewpoint variations while maintaining spatial consistency in the spinal centerline, pelvic axis, and shoulder line, regardless of gender or body shape differences. Furthermore, the multi-LOD ensemble-based skeleton voting technique confirms that the spinal centerline is continuously estimated without interruption, even in low-resolution meshes. Consequently, the method demonstrated in this study provides a universal 3D posture analysis framework capable of quantitatively analyzing and visually representing differences in spinal curvature and trunk registration based on body shape characteristics between genders.

4.3. Processing Time

To address execution-time considerations for clinical deployment, we report the wall-clock processing time of the proposed pipeline. All timing measurements were obtained on the same workstation described in Section 4.1 using Python wall-clock timing.

As shown in Table 6, a full batch run over 131 datasets required 98.5 min (5910 s) in total, corresponding to 45.1 ± 8.4 s per dataset (min: 28.3 s; max: 67.8 s). This corresponds to a throughput of 79.9 datasets/hour and an overall processing efficiency of 95.2% according to our runtime logger. This runtime includes point cloud generation from multi-view depth images, preprocessing, RANSAC-FPFH global alignment, point-to-plane ICP refinement, bmesh construction, LOD generation, and LOD ensemble skeleton extraction.

Table 6.

End-to-end processing time statistics of the proposed pipeline (N = 131 datasets).

The current implementation is not designed for real-time interaction (e.g., per-frame feedback) and is intended for offline reconstruction and clinical screening workflows. Given the measured throughput (~80 datasets/hour), the proposed system supports batch-mode clinical pipelines, while real-time applications would require further optimization and/or GPU-accelerated implementations. Because the pipeline is modular, users can reduce execution time by lowering the number of LODs evaluated or by relaxing global-registration settings (e.g., fewer RANSAC hypotheses) when a faster but less robust mode is acceptable.

5. Discussion

5.1. Statistical Analysis

To assess whether the performance differences between point-to-point ICP and point-to-plane ICP are statistically significant, we performed paired statistical tests on the fine registration outcomes. For each multi-view reconstruction sample (N = 393), we measured ICP fitness and RMSE after local refinement under identical global initialization (RANSAC-FPFH) and correspondence update settings. RMSE and fitness follow the definitions described in Section 3.4.

Normality was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Both fitness and RMSE distributions significantly deviated from normality (p < 0.001 for all cases); therefore, we adopted a non-parametric paired comparison. For RMSE, 11 paired measurements contained non-finite values (infinite RMSE) due to non-convergent registrations; these pairs were excluded, resulting in 376 valid paired samples for RMSE analysis.

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed that the fitness difference was not statistically significant (W = 14,727; p = 9.91 × 10−2), although point-to-plane ICP achieved a marginally higher mean fitness (0.6610 vs. 0.6586; +0.37%). In contrast, the RMSE difference was statistically significant on the valid paired set (W = 26,774; p = 5.88 × 10−4, p < 0.001), indicating that point-to-plane ICP yields a small but consistent reduction in RMSE across samples (+0.75% improvement; lower is better) over the 376 valid pairs.

We additionally report effect sizes based on Cohen’s d computed from paired differences, which were small for both metrics (fitness: d = 0.0138; RMSE: d = 0.0188). Taken together, despite the marginal effect sizes, point-to-plane ICP demonstrates a statistically significant and consistent improvement in RMSE (with a slight gain in mean fitness); therefore, we adopt point-to-plane ICP as the fine registration step in the proposed pipeline.

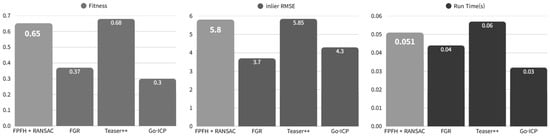

5.2. Comparison with SOTA Global Registration Baselines

The objective of this evaluation is to assess the robustness and computational efficiency of the initialization stage by benchmarking representative global registration baselines. Under the same preprocessing and evaluation protocol, the RANSAC–FPFH initializer was compared with TEASER++ [45], Fast Global Registration (FGR) [46], and Go-ICP [20]. Figure 11 summarizes the average fitness, inlier RMSE, and runtime. TEASER++ achieved the highest mean fitness (0.68), while RANSAC–FPFH followed closely (0.65). Although TEASER++ provides a slightly higher fitness, RANSAC–FPFH showed a more favorable computational overhead in our setting, maintaining an efficient runtime and a smaller resource footprint for repeated execution within the full reconstruction pipeline. FGR yielded the lowest inlier RMSE (3.7) but exhibited substantially lower fitness (0.37), suggesting that small residuals may still arise under limited overlap. Go-ICP was the fastest (0.03 s) but produced the lowest fitness (0.30). Since reliable overlap (high fitness) is essential for stable ICP refinement and the initialization step is executed repeatedly within the full pipeline, both overlap quality and runtime must be considered jointly. Therefore, RANSAC–FPFH is retained as the default initializer, as it provides near-competitive fitness with a lower runtime and reduced computational overhead, aligning with the goal of practical and resource-efficient deployment, while TEASER++ is considered as an alternative when maximum robustness is prioritized.

Figure 11.

Quantitative comparison of global registration methods used for the initialization stage. The bar plots report the average fitness, inlier RMSE, and runtime for FPFH+RANSAC, Fast Global Registration (FGR), TEASER++, and Go-ICP, evaluated under the same preprocessing and correspondence settings. Fitness indicates the degree of geometric overlap after initialization, inlier RMSE measures the residual alignment error over inlier correspondences, and runtime reflects the computational cost of the global registration step.

5.3. Limitations

As illustrated in the last row of Figure 10, the proposed pipeline can still achieve stable point cloud registration even for atypical body types such as obesity. However, it is important to note that the spinal curvature angles reported in this study are not derived from direct observation of the vertebrae but are instead estimated from the reconstructed external body surface obtained from depth measurements. Consequently, for subjects with substantial soft-tissue thickness or atypical body proportions, the clinical accuracy of curvature-related metrics (e.g., cervical/lumbar lordosis and thoracic kyphosis) cannot be guaranteed. In such cases, the reported angles should be interpreted as screening-level indicators rather than definitive diagnostic measurements.

Furthermore, dense hair and loose or thick clothing may introduce depth discontinuities and irregular surface microstructures, which can negatively affect surface-normal estimation and correspondence matching, particularly around the head and shoulder regions. To mitigate these effects, standardized acquisition conditions are recommended, such as minimizing hair-induced occlusions and using clothing that preserves the body silhouette. The proposed approach also assumes quasi-static capture with a consistent neutral pose across the four directional views. Large pose variations, self-occlusions, or inter-view motion reduce the overlapping surface area and can lead to non-convergent registration or inconsistent skeletal line extraction. Therefore, the method may be less reliable for complex poses or dynamic movements, and stable acquisition conditions with limited motion are preferred.

Finally, robust performance requires sufficiently dense and well-calibrated depth measurements. Increased sensor noise, missing returns, or low spatial resolution can propagate to point cloud artifacts, degrading both global and local registration and ultimately affecting the reliability of the extracted reference lines and angle estimates. Hence, the proposed pipeline is contingent on a minimum level of depth-sensor quality and stable calibration for consistent results.

Additionally, direct quantitative comparisons with deep learning-based methods (e.g., PointNetLK [28], DCP [29]) on standard benchmarks like SMPL were not conducted in this study. This decision stems from fundamental mismatches between our medical depth data—characterized by four-directional fixed-capture depth maps with specific scale and structural distributions—and the large-scale RGB-D/general human scan datasets used to train these models. Applying pre-trained learning-based models to our medical data without extensive fine-tuning or domain adaptation could lead to misleading performance comparisons; instead, we prioritized validation of geometric registration accuracy and stability under clinical acquisition constraints, which aligns with the primary goal of developing a training-free, interpretable pipeline for healthcare applications.

Regarding global registration, methods like TEASER++, Faster Global Registration, and Go-ICP, while offering strong theoretical guarantees, were not employed due to their computational overhead, which is prohibitive for real-time clinical workflows. These approaches incur significantly higher processing times (often 10–50× slower) and require extensive preprocessing, making them less suitable for point-of-care applications. Our RAN-SAC-FPFH pipeline achieves comparable robustness with sub-second execution on standard hardware, optimally balancing speed and accuracy under medical acquisition constraints.

6. Conclusions

A key contribution of this study is the presentation of a 3D analysis framework that can robustly reconstruct human structures purely through geometric registration and shape analysis, i.e., without complex deep learning networks or extensive additional training data. Furthermore, the adaptive mesh simplification and multi-LOD-based skeleton voting reduced resolution bias while enhancing robustness against voids and noise. This approach maximally avoids fundamental constraints in medical imaging environments, such as data sparsity, privacy concerns, and challenges in generalization, while maintaining the interpretability of each algorithmic step.

Future research could focus on improving the quality of 3D human model reconstruction from this system. Currently, only vertex reduction and mesh smoothing are performed on aligned models for spinal centerline estimation. However, introducing hole-filling techniques could facilitate continuous and natural surface restoration in missing areas, leading to more complete and detailed 3D model reconstructions.

To further extend this study clinically, utilizing specialized medical data such as X-ray or CT scans could enhance the geometric accuracy of the estimated spinal centerline by simultaneously reflecting both internal skeletal structures and external shapes. This may enable the techniques developed in this research to evolve into a medical anatomical 3D registration platform applicable for clinical diagnosis, surgical planning, and rehabilitation prognosis evaluation, extending beyond simple spinal estimation.

In addition, to further extend this study toward clinical research contexts, future work may incorporate specialized medical imaging data such as X-ray or CT scans. Such integration could enable a more detailed investigation of the relationship between external body geometry and internal skeletal structures. In the present study, the primary focus is placed on validating a depth-based geometric reconstruction framework, while clinical validation and diagnostic applications are left for future investigation.

Consistent with prior studies adopting ISO 11226 and RULA/REBA for vision- or depth-based posture analysis, the posture risk categories defined in this work are intended to support structured interpretation of posture tendencies in non-contact settings. Future studies that further align posture risk criteria with clinically grounded standards may enhance the precision and applicability of depth-based posture risk assessment.

Author Contributions

S.K., H.-J.L., J.L. and T.L. participated in all phases of manuscript production and contributed equally to this work. Their specific contributions are as follows: S.K. contributed to the methodology, software, and formal analysis; H.-J.L. and J.L. contributed to the investigation, resources, and data curation; C.K. contributed to the data preparation, original draft preparation, visualization, and project administration; T.L. contributed to reviewing and editing the manuscript, supervision, and project administration; and all authors contributed to the conceptualization and validation of the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Technology Innovation Program (RS-2024-00507228—development of process upgrade technology for AI self-manufacturing in the cement industry) funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Republic of Korea).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Kangwon National University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kumar, K.V.R.; Elias, S. Real-Time Tracking of Human Neck Postures and Movements. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, Y.; Miyakoshi, N.; Hongo, M.; Kasukawa, Y.; Kudo, D.; Shimada, Y. Relationships among spinal mobility and sagittal alignment of spine and lower extremity to quality of life and risk of falls. Gait Posture 2017, 53, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.H.; Zhang, Y.H.; Yang, Q.H.; Wang, Y.C.; Fang, Y.; Wang, X.Q. Spinal posture assessment and low back pain. EFORT Open Rev. 2023, 8, 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]