Featured Application

The methodology proposed in this work is directly applicable to the durability design of metallic foundations in large-scale photovoltaic power plants, enabling engineers and asset owners to quantify soil corrosivity, estimate the service life of galvanized or ZnAlMg-coated steel piles, and define steel thickness allowances with a traceable and auditable procedure.

Abstract

Soil corrosion is a critical durability and cost factor for metallic foundations in photovoltaic (PV) power plants, yet it is still addressed with fragmented criteria compared with atmospheric corrosion. This paper reviews the main soil corrosivity drivers relevant to PV installations—moisture and aeration dynamics, electrical resistivity, pH and buffer capacity, dissolved ions (notably chlorides and sulfates), microbiological activity, hydro-climatic variability and geological heterogeneity—highlighting their coupled and non-linear effects, such as differential aeration, macrocell formation and corrosion localization. Building on this mechanistic basis, an engineering-oriented methodological roadmap is proposed to translate soil characterization into durability decisions. The approach combines soil corrosivity classification according to DIN 50929-3 and DVGW GW 9, tiered estimation of hot-dip galvanized coating consumption using AASHTO screening, resistivity–pH correlations and ionic penalty factors, and verification against conservative NBS envelopes. When coating life is insufficient, a traceable steel thickness allowance based on DIN bare-steel corrosion rates is introduced to meet the target service life. The framework provides a practical and auditable basis for durability design and risk control of PV foundations in heterogeneous soils. The proposed framework shows that, for soils exceeding AASHTO mild criteria, zinc corrosion rates may increase by a factor of 1.3–1.7 when chloride and sulfate penalties are considered, potentially reducing coating service life by more than 40%. The methodology proposed enables designers to estimate the penalty factors for sulfates () and chlorides () in each specific project, calculating the appropriate values of and using electrochemical techniques—ER/LPR and EIS—to estimate the effect of the soluble salts content in the , not properly catch by the proxy indicator when sulfate and chloride content are over AAHSTO limits for mildly corrosive soils.

1. Introduction

The structural degradation of steel and aluminum, whether exposed to the atmosphere or buried in soil, has been extensively investigated by numerous authors [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Consequently, corrosion is a well-established phenomenon in both environments; however, comprehensive and standardized tools for the quantitative assessment of corrosion rates are essentially available only for atmospheric corrosion. In this context, international standards such as UNE-EN ISO 9223:2012 [8], UNE-EN ISO 9224:2012 [9], UNE-EN ISO 9225:2012 [10] and UNE-EN ISO 9226:2012 [11] provide a coherent framework to classify atmospheric corrosivity and to determine reference corrosion rates for the first year of exposure as well as for long-term performance.

By contrast, for metallic structures that are fully or partially buried—such as the driven steel piles used in photovoltaic support structures—the available regulatory guidance and validated technical documentation remain limited. This scarcity is largely attributable to the wide range of interacting parameters governing soil corrosion and to the inherent difficulty of observing and monitoring buried systems. Existing standards, including DIN 50929-3:2024-05 [12], DVGW GW 9:2011 [13], AWWA C105/A21.5-18 [14] and UNE-EN 12501-1:2003 [15], primarily focus on classifying soil corrosivity based on selected environmental factors. Nevertheless, they generally provide corrosion rate data only for uncoated carbon steels and do not offer methodologies to estimate the service life of structures protected by hot-dip galvanized coatings or by more recent ZnAlMg alloy coatings.

Several metallic materials commonly employed in photovoltaic power plants exhibit inherently good corrosion resistance, notably aluminum and carbon steel protected by Fe–Zn galvanizing or by ZnAlMg self-protective coatings. However, critical elements of the system include the driven piles, pile–earthing grid connections, interfaces between dissimilar metals (steel–aluminium), and bolted assemblies. Inadequate corrosion-oriented design can, therefore, lead to increased corrective and preventive maintenance costs and, in severe cases, may compromise the structural service life of the installation [16].

Within this framework, the objective of the present work is to synthesize the most influential drivers of soil corrosivity in photovoltaic power plants and, on this basis, to propose an engineering-oriented methodological framework that establishes a traceable link between soil characterization and two key design decisions: the estimation of the durability of zinc-based coatings (HDG and ZnAlMg) and the sizing of the required steel overthickness when the target service life exceeds the expected coating lifetime.

Although soil-induced corrosion also affects other photovoltaic components such as grounding systems, cable conduits and auxiliary metallic structures, the present work intentionally focuses on driven steel foundations, as they govern the structural integrity, load transfer and long-term durability of PV installations. The corrosion mechanisms and mitigation strategies for other subsurface components involve additional electrical, regulatory and operational considerations that fall outside the scope of this review.

Section 2 reviews the main physical, chemical, biological and geological drivers governing soil corrosivity in photovoltaic installations. Section 3 presents an engineering-oriented methodological framework that integrates DIN 50929-3, DVGW GW 9, AASHTO and NBS approaches to translate soil corrosivity into coating durability and steel overthickness requirements. Section 4 provides a critical discussion of the applicability, assumptions and limitations of the proposed framework, while Section 5 identifies key research needs and emerging trends. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the main conclusions of the study.

2. Soil Corrosivity Drivers in Photovoltaic Power Plants

Soil constitutes a complex corrosive environment in which multiple interacting factors govern the degradation of buried metallic structures. These factors have been identified through a combination of field exposure tests and laboratory investigations conducted on both natural and simulated soils [6]. The most influential parameters include soil type, moisture content, degree of aeration, redox potential, acidity, buffering capacity, electrical resistivity, dissolved ionic species, and the presence of microorganisms and bacteria [2,6,7,17,18]. The following section defines and discusses each of these factors and their respective roles in controlling soil-induced corrosion.

2.1. Physical Parameters

2.1.1. Soil Texture

Soils are commonly classified according to the grain size of their constituent particles. In this context, the most widely adopted and accepted soil classification system is that developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) [19], in which soils are characterized based on the relative proportions of clay, silt and sand present in the medium [20]. However, this classification does not explicitly account for topsoils rich in organic matter, which are frequently encountered within the upper soil layers of photovoltaic power plant sites.

The finest particles (clays) are generally regarded as the most corrosive soil fraction due, among other factors, to their reduced degree of aeration and low electrical resistivity. Clay contents exceeding 80% in the fraction finer than 0.08 mm have been shown to significantly promote corrosion. Conversely, coarser particles such as gravels and sands tend to exhibit lower corrosivity because of higher permeability, improved aeration and higher resistivity. Nevertheless, as will be discussed later, the most detrimental configurations are those in which different soil types are simultaneously in contact with the metallic element, as such heterogeneity promotes differential aeration cells and accelerates localized corrosion processes. For this reason, particle size distribution analysis is routinely performed, as it provides an indirect indicator of several key parameters that are addressed in the subsequent sections.

2.1.2. Moisture

The primary role of subsurface moisture in the corrosion process is to provide the soil with ionic transport capability, thereby enabling both anodic and cathodic electrochemical reactions [20]. Fluctuations in soil moisture content markedly modify the physical and chemical properties of the soil, which in turn govern the corrosion susceptibility of grounding systems in photovoltaic installations [21,22].

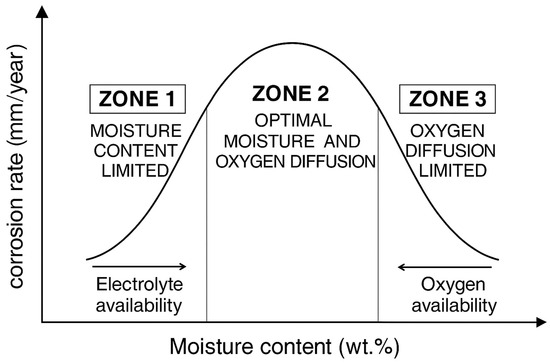

The corrosion of steel buried in soil is therefore closely linked to the moisture content of the surrounding environment. A dry soil requires a minimum level of moisture and dissolved salts to behave as an effective ionic conductor or electrolyte; under such dry conditions, corrosion rates remain low due to the high electrical resistivity of the medium [23,24]. Consequently, a direct relationship exists between soil moisture content and corrosion rate up to a critical moisture level, beyond which the corrosion rate decreases [6,7,25,26,27], as illustrated in Figure 1. This behaviour is generally attributed to the combined effects of enhanced electrical conductivity, the extent of electrochemically active surface area, and the rate of oxygen diffusion through the soil matrix [24,26,27,28,29].

Figure 1.

Relationship between soil moisture content and metal corrosion rate, adapted from [6].

Oxygen transport is intrinsically linked to soil porosity; therefore, when soil pores are fully filled with water, the diffusion of O2 through the wetted soil becomes the rate-limiting step, as oxygen diffuses much more slowly in water than in air [25,26,30,31]. Once a certain moisture threshold is exceeded, the limited ability of oxygen to reach the metal surface inhibits the cathodic reaction and consequently reduces the mass loss associated with metal corrosion [25]. From an electrochemical standpoint, the cathodic oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) constitutes the dominant cathodic process controlling corrosion kinetics in aerated soils.

Accordingly, the maximum corrosion rate occurs at an intermediate moisture level, at which the soil contains sufficient water to ensure adequate ionic conductivity, while still maintaining enough air-filled pores to allow rapid oxygen diffusion to the metal surface [32].

Several studies have quantified this critical moisture content for different soil types and materials:

- Mild steel: Maximum corrosivity is generally observed at approximately 65% of the soil water-holding capacity [24]. In silty soils, the peak corrosion rate typically occurs between 60% and 70% saturation [33].

- Bare Steel: The corrosion rate has been shown to reach a maximum at moisture contents of around 20 wt. % for sandy soils and approximately 25 wt.% for clayey, saline and calcareous soils [23].

- Galvanized Steel: In simulated soil environments, zinc corrosion remains low at saturation levels above 80%; however, at saturation degrees below 80%, corrosion increases markedly, reaching a maximum at around 50% saturation [30].

Furthermore, studies by Fu et al. and Noor and Al-Moubaraki [34,35] report a significant increase in corrosion rate at moisture contents exceeding approximately 10%. In addition, in soils with low water content, the effective wetted surface area in contact with the electrolyte may be extremely limited, promoting non-uniform corrosion; under such partially saturated conditions, corrosion tends to be faster and more localized [36].

Azoor et al. [27] investigated the corrosion behaviour of three different soils (sand, silt and clay). All three soils exhibited an increase in corrosion current density (icorr) with increasing degree of saturation up to a critical point, beyond which the corrosion rate decreased. Among the tested soils, sand and silt exhibited the lowest and highest corrosion rates, respectively, while clay showed intermediate corrosivity.

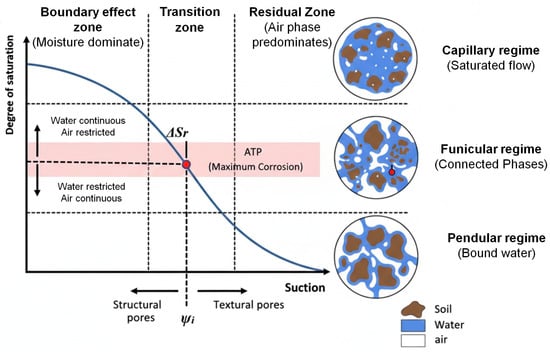

Moreover, Azoor et al. [27] identified three distinct zones in the soil water retention curves of the investigated soils: the boundary effect zone, the transition zone and the residual zone (Figure 2).

- Boundary effect zone. Water occupies the large (structural) pores and remains mobile, while the air phase is highly restricted.

- Transition zone. Both air and water phases are continuous; this region is characterized by the largest change in water content with suction.

- Residual Zone. Water is strongly bound to soil particles within small (textural) pores and is nearly immobile, while a continuous air phase predominates.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the soil water retention curve (SWRC) illustrating the continuity/discontinuity of the air and water phases as the structural and textural pores fill up or drain. Adapted from [27].

The Air Transition Point (ATP), located within the transition zone (critical region), corresponds to the inflexion point of the soil water retention curve. At this state, continuity of the aqueous phase (enabling ionic conduction) and continuity of the gaseous phase (allowing oxygen diffusion) coexist. According to Azoor et al. [27], maximum corrosion occurs precisely at this inflexion point, where the conditions promoting ionic transport and oxygen supply are simultaneously balanced.

Dang et al. [28] reported that, in partially saturated soils, the high electrolyte resistance and the reduced effective metal–electrolyte contact area lead to significantly lower corrosion rates than in fully saturated soils. In addition, cathodic protection is particularly effective in partially saturated soils, where oxygen reduction remains the dominant cathodic reaction under both saturation regimes, but improved aeration at lower moisture contents facilitates oxygen transport. Furthermore, Dang et al. observed that the composition of corrosion products strongly depends on soil moisture, with goethite (γ-FeOOH) forming preferentially in partially saturated soils, whereas carbonate green rust predominates under saturated conditions.

To summarize, oxygen transport in soils is primarily governed by the continuity of the gaseous phase and the degree of pore saturation. As soil moisture increases, gas-filled pore connectivity decreases and oxygen diffusion becomes progressively limited, shifting corrosion control from charge-transfer kinetics to mass-transport constraints. This transition plays a key role in defining the spatial distribution of cathodic sites and the severity of localized corrosion in heterogeneous soils, particularly under partially saturated conditions typical of photovoltaic installations.

2.1.3. Aeration Grade

The factors governing the degree of aeration are those that hinder or promote the access of oxygen to the metal surface and are, in many cases, wholly or partially responsible for the soil moisture state [20]. It is widely accepted within the scientific community that soils with greater oxygen availability to sustain the cathodic reaction exhibit higher corrosion rates [2,6,20,37].

The degree of aeration is not an intrinsic soil property; rather, it depends on a range of characteristics that are predominantly physical in nature. A substantial body of literature correlates soil texture with aeration, often treating it as a parameter directly linked to soil corrosivity without explicitly accounting for soil type, particle size distribution, organic matter content, or microbial activity [2]. However, several interacting variables complicate such simplified interpretations.

Aeration must be regarded as a dynamic variable, since oxygen access to the metal surface for the cathodic reaction evolves over time. Studies such as those by Aung and Tan [38] report that corrosion rates tend to decrease with exposure time due to the formation and growth of corrosion product layers that progressively hinder oxygen diffusion towards the metallic substrate, rendering corrosion controlled by the oxygen reduction reaction. Nevertheless, the increasing protective character of the oxide film may, in turn, promote the development of localized corrosion [38].

As discussed in the previous section, an inverse relationship exists between soil moisture content and aeration: increasing moisture leads to reduced aeration and, once the point of maximum corrosivity is exceeded, to a decrease in corrosion potential [27]. Moreover, cyclic variations in moisture and oxygen availability may arise, further promoting corrosion of the affected metal.

Steel elements driven into the ground in photovoltaic power plants are frequently in contact with lithologies of different natures, meaning that a single steel profile may intersect two or more distinct geological units. This results in different oxygen partial pressures along the same metallic element, giving rise to potential differences between adjacent zones [39]. Owing to contrasts in oxygen diffusion and water permeability between lithological units or geological discontinuities, regions with higher oxygen concentration tend to act as preferential cathode sites where the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) is enhanced, whereas less aerated zones preferentially behave as anodes [20,40].

The simultaneous presence of clayey soils (low aeration) and gravels or sands (high aeration)—a configuration commonly encountered in photovoltaic projects—leads to the localisation of anodic oxidation reactions within the clay unit, while cathodic reactions are favoured in the gravelly or sandy unit [5]. This phenomenon, known as differential aeration corrosion or the Evans effect, results in a pronounced local increase in corrosion rate.

The influence of oxygen concentration gradients on the actual redistribution of corrosion currents has been analyzed in detail by Liu and Li [41] using electrochemical modelling coupled with fluid dynamics. Their results demonstrate that, when corrosion driven by oxygen concentration differences is explicitly considered, anodic polarization develops in poorly aerated regions and cathodic polarization in well-aerated zones. This leads to a redistribution of corrosion currents that tends to homogenize the overall potential, while locally intensifying the anodic current density. This mechanism explains why geometrically less exposed areas may develop significantly higher corrosion rates, providing electrochemical validation of the classical concept of differential aeration corrosion.

The investigations by Levlin [42] sought to clarify the behaviour of carbon steel in contact with a geological couple composed of clay and sandy soils. After 2.67 years of exposure, corrosion rates were shown, in some cases, to increase by a factor of up to 6.4. In addition, cyclic wet–dry processes were found to induce partial cracking of the clay, generating channels that enable re-aeration of the soil [42].

Similarly, studies conducted by Glazov et al. [43] confirmed the critical role of differential aeration in natural soils due to the formation of geological cells. Their work showed that corrosion cells generated by differences in moisture content—and thus in aeration degree—between two geological formations significantly intensified localized corrosion [43].

In this context, recent experimental work by Liu et al. [44] quantitatively demonstrates the strong dependence of corrosion severity on aeration degree and soil layer thickness for buried carbon steels. In their study on X52 steel buried in clay soils with varying cover thickness, the maximum uniform corrosion rate was observed at intermediate soil thicknesses (≈5 mm), where a balance exists between moisture retention and oxygen diffusion from the atmosphere. Under strictly anaerobic conditions (N2), corrosion was practically negligible, whereas in aerated soils, corrosion rates increased by up to an order of magnitude. More importantly, localized corrosion rates exceeded 1 mm·year−1, far surpassing uniform corrosion rates, demonstrating that aeration controls not only the overall corrosion kinetics but also the severity of localized attack. This latter observation regarding localized corrosion has also been reported by Glazov et al. [43].

The installation of driven steel structures, as well as the construction of access roads, drainage systems and permanent foundations in photovoltaic plants, inevitably involves earthworks that modify the natural oxygen distribution within the soil [39,40,45]. As a result, artificial air pockets may form heterogeneously in contact with the driven steel, facilitating the development of subsurface zones prone to anodic or cathodic behaviour [40]. Furthermore, excavation generally reduces the degree of compaction of soils or rocks, increasing their permeability to corrosive agents such as oxygen and water [39]. For this reason, it is advisable to avoid over-excavation, to backfill trenches in layers with adequate compaction, and to select low-corrosivity backfill materials with aeration characteristics similar to those of the surrounding lithologies.

Finally, it should be noted that although oxygen is the primary depolarizing agent in non-strongly acidic electrolytes and is essential for electrochemical corrosion processes, the presence of microorganisms in soils may induce corrosion even under anaerobic conditions [2]. Nevertheless, many of the bacteria involved in microbiologically influenced corrosion require oxygen for their metabolism, highlighting the complexity of degradation mechanisms in natural soils [2,46].

Taken together, these phenomena demonstrate that differential aeration corrosion and the formation of geological corrosion cells cannot be regarded as isolated mechanisms, but rather as highly probable processes in structures driven into heterogeneous natural soils, such as those encountered in photovoltaic power plants. The combination of lithological layers with contrasting permeability, earthworks, seasonal moisture variations and artificial redistribution of oxygen creates a particularly favourable scenario for the development of severe localized attack, underscoring the need to explicitly account for these mechanisms during both the design stage and the service-life assessment of buried infrastructure.

2.2. Chemical Parameters

2.2.1. Acidity

With regard to soil pH, a certain degree of controversy persists due to the disparity of results reported by different investigators. While in aqueous solutions an increase in corrosion rate is consistently observed with decreasing pH [47], as well as under highly alkaline conditions [48], studies conducted in soils have yielded contradictory outcomes. Nevertheless, there is a broad scientific consensus regarding the favourable performance of zinc within a pH range of approximately 6 to 9.

In the seminal studies by Melvin Romanoff [20], a direct correlation can be observed between decreasing pH and the weight loss of specimens exposed to potentially corrosive soils. This correlation has subsequently been adopted as a reference by researchers such as Arriba-Rodriguez et al. and Rajani and Makar [2,49] for the development of predictive models of soil corrosivity based on a set of carefully selected parameters, including pH.

By contrast, other investigations, such as those carried out by Penhale and Doyle [50,51], report no discernible correlation between pH and soil corrosivity. Despite these discrepancies, the most widely accepted view is that the risk of soil-induced corrosion increases under more acidic conditions (pH < 6) [2].

Although the pH of most soils typically lies within the range 4.5–8, localized zones may exist where pH deviates significantly, either due to natural causes (e.g., acid drainage) or anthropogenic influences (e.g., contamination), resulting in either more acidic or more alkaline environments [33,52]. Soils exhibiting pH values outside the neutral range tend to accelerate corrosion processes as a consequence of the reduced stability of corrosion products formed on the metal surface [5].

Under acidic conditions, according to Hirata et al. [53], steel corrosion is predominantly controlled by the cathodic hydrogen evolution Reaction (2).

Additionally, with increasing exposure time, the charge transfer resistance (Rct) decreases as the corrosion process progresses and the available H+ ions in solution are progressively consumed; under these conditions, proton (H+) diffusion becomes the rate-limiting step [53].

Among other factors, the variation in corrosion rate associated with the blockage of the cathodic reaction due to proton depletion constitutes one of the main reasons why simulated soil solutions are not an optimal approach for investigating the influence of pH. Such simplified media fail to reproduce the physical, geological and geotechnical properties of real soils, and therefore do not provide representative information on soil-induced corrosion behaviour [6].

2.2.2. Electrical Resistivity

Electrical resistivity is a physical property that describes the opposition of a medium to the flow of electric current and has historically been one of the most widely used parameters for assessing soil corrosivity. From an electrochemical standpoint, resistivity indirectly reflects the ability of the soil to behave as an electrolyte, as it is closely linked to the mobility of ions dissolved in the pore water. In practice, resistivity is commonly measured in situ using four-electrode configurations, with the Wenner array being among the most frequently applied, as increasing electrode spacing allows investigation of progressively larger effective soil volumes.

However, resistivity is not an intrinsic, independent material property, but rather depends in a highly non-linear manner on multiple soil-related factors, including moisture content, porosity, degree of compaction, mineralogical composition, pore water chemistry and temperature [5,33,54,55,56]. Both classical and recent experimental studies have demonstrated inverse exponential correlations between resistivity and soil moisture content, as well as with dry density, such that relatively modest increases in saturation degree may reduce resistivity by more than one order of magnitude [55,56,57]. Laboratory tests and field monitoring campaigns further confirm that resistivity exhibits pronounced seasonal variability, with decreases exceeding one order of magnitude as moisture content increases from dry conditions to saturation, and with robust logarithmic correlations (R2 ≈ 0.8–0.9) between apparent resistivity at 1 m depth and cumulative rainfall over the preceding 30 days [58]. Non-linear regression models and neural-network-based approaches additionally demonstrate that resistivity responds to the coupled influence of geotechnical and physicochemical variables, making it impossible to describe adequately using simple linear relationships [59].

Several studies have attempted to directly parameterize the relationship between resistivity and corrosion rate, particularly given that standards such as DIN 50929-3 and DVGW GW 9 continue to assign negative weight to low resistivity values in soil corrosivity classifications. Nevertheless, long-term field investigations have shown that the correlation between resistivity and metal loss may be weak or even absent. The work of Melchers and Wells (2018) [60], based on cast-iron pipelines exposed for more than 60 years, demonstrates that resistivity exhibits no consistent relationship with either average corrosion rate or maximum pit depth, as the governing processes are largely controlled by differential aeration and effective time of wetness—parameters that resistivity does not adequately capture.

In a similar vein, the critical analysis by Deo et al. (2022) [61] shows that the relationship between resistivity and corrosion damage is clearly non-monotonic and depends on the saturated resistivity distribution being statistically uniform along the infrastructure, a condition rarely met in heterogeneous natural soils. These authors conclude that, although low resistivity values are often associated with highly corrosive environments, resistivity alone does not allow reliable prediction of either the location or the severity of localized attacks.

In addition to these conceptual limitations, significant metrological uncertainties are associated with the resistivity measurement itself. The recent review by Amadi et al. (2025) [62] highlights that field-measured resistivity is strongly influenced by soil heterogeneity, electrode–soil contact resistance, electromagnetic interference, the presence of nearby structures, the effective depth of investigation and the specific electrode configuration employed. This study further demonstrates that even measurements performed under standardized protocols may exhibit substantial systematic errors if not integrated with complementary geophysical techniques, such as electrical resistivity tomography or induced polarization methods.

From a climatic and hydrological perspective, resistivity also displays pronounced seasonal variability. Laboratory experiments and field monitoring show that increasing water content leads to a sharp reduction in resistivity, while freeze–thaw cycles induce abrupt transitions in soil electrical conductivity [63]. This behaviour reinforces the notion that resistivity is a dynamic variable, whose instantaneous value may not be representative of the average corrosion conditions prevailing throughout the year.

Consequently, although soil electrical resistivity remains an indispensable indicator in corrosion studies, the experimental and field evidence accumulated over recent decades clearly confirms that it cannot be used as a univocal parameter nor interpreted in isolation. Its strong dependence on moisture, temperature, salinity, compaction, stratigraphy and spatial heterogeneity, together with the inherent limitations of in situ measurement techniques, makes it essential to integrate resistivity with other physical, chemical, electrochemical and geological parameters in order to achieve a realistic assessment of soil corrosivity [60,61,62].

2.2.3. Ion Content

The ions present in a potentially corrosive electrolyte mainly include hydrogen and hydroxyl ions derived from water dissociation, as well as a wide variety of cations and anions whose concentration and nature depend on the mineralogical composition of the soil and on the abundance of salts dissolved in the liquid phase [20]. The principal ions dissolved in soil pore water are Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, Cl−, SO42−, NO3−, HCO3− and CO32− [64], originating from both natural and anthropogenic processes.

The presence and nature of these dissolved ions modify other parameters previously described as being related to soil corrosivity, such as electrical resistivity and acidity. In the case of resistivity, higher concentrations of dissolved salts reduce the resistance of the electrolyte to electrical current flow, thereby decreasing resistivity [62,65]. In other words, the natural or induced presence of dissolved salts in ionic form increases the conductivity of the ionic medium and, consequently, its corrosivity. In contrast, the effect on acidity depends on the specific ionic species in solution: sodium, potassium, calcium and magnesium tend to impart a basic character to the pore water, whereas chlorides, sulphates and carbonates may contribute to acidity [5]. In addition, these salts strongly influence the mineralogy of the primary corrosion products.

Numerous studies [5,66,67] explicitly identify chloride and sulphate ions as the dominant anions in the assessment of soil corrosivity towards buried steels, using them—together with resistivity—as key parameters to distinguish essentially non-corrosive soils from highly or extremely corrosive ones. This is primarily due to the high solubility of the corrosion products generated by these anions at both anodic and cathodic sites on the metal surface [20]. Nevertheless, the presence of other dissolved ions, such as bicarbonates or nitrates, may substantially modify corrosion behaviour under specific conditions.

The sulphate content of a soil should be determined both in aqueous media—representative of the natural behaviour of the wetted soil—and in acidic media, since acid extraction quantifies the soil “acid reserve”, i.e., the potential contribution of the soil to the electrolyte under changing leaching conditions. For this reason, factor-based systems used to define soil corrosivity categories, such as DIN 50929-3:2024-05 [12], explicitly require such determinations.

In the context of soils and pore solutions with near-neutral pH, sulphate ions exert a specific effect on corrosivity that goes beyond their contribution to total salinity. Studies conducted in synthetic calcareous media show that SO42− decisively modifies both the nature and the functionality of corrosion product films on carbon steel. On the one hand, sulphates increase electrolyte conductivity and participate in the formation of soluble complexes (FeSO4(aq.)) that catalyze iron dissolution; on the other hand, they may be incorporated into and adsorbed within oxide layers, generating mixed gypsum–carbonate deposits that, depending on their growth kinetics, act as partial barriers to oxygen transport and result in significant variations in charge-transfer resistance and low-frequency impedance [68]. In electrolytes near pH 8, sulphate concentrations on the order of 10 mM have been identified as particularly aggressive, promoting active dissolution accompanied by the formation of thick, heterogeneous corrosion product layers, whereas at slightly more alkaline pH values (≈9.5) the increased [OH−] may restore passive conditions even in the presence of sulphates [69]. Furthermore, burial tests of galvanized steel in sulphate-enriched artificial soils demonstrate that sulphates become a critical aggressiveness parameter and, in combination with chlorides, generate a synergistic effect that accelerates degradation of the zinc coating until the steel substrate is exposed [5].

Within soil–metal systems, the chloride ion (Cl−) is recognized as the most aggressive anion from an electrochemical standpoint, owing to its high ionic mobility, small hydrated radius and strong ability to destabilize passive films and corrosion product layers [70]. Electrochemical tests in soils artificially amended with NaCl show that increasing chloride content causes a sharp reduction in electrolyte resistivity, a decrease in impedance modulus and a significant reduction in charge-transfer resistance, resulting in an exponential increase in the corrosion rate of carbon steel, particularly above concentrations of approximately 1–2 wt.% [71].

The depassivating action of Cl− is further associated with its ability to penetrate oxide layers, preferentially adsorb at defects in the galvanized coating, and promote the formation of unstable phases such as β-FeOOH (akageneite), which is highly porous and chloride-rich. This markedly increases susceptibility to localized corrosion and pitting [72]. In this context, chloride acts as a thermodynamic activator of pitting processes, with a semi-logarithmic relationship existing between Cl− concentration and the pitting initiation potential, as demonstrated in dedicated studies on structural steels [70].

In real soils, the effect of chlorides is further intensified by ionic migration phenomena driven by stray currents, leading to preferential accumulation of Cl− in anodic zones and accelerated metal dissolution, with a logarithmic relationship between mass loss and chloride content [73].

In this regard, the work of Song et al. [72] represents one of the most comprehensive references on the specific effect of chlorides on the corrosion of ferrous materials in saline soils. In their study, carbon steel and ductile iron were exposed for three months to a natural soil containing six chloride levels ranging from 0.015 to 1.015 wt.%. Mass loss, attack morphology, pit depth, corrosion product nature (XRD) and electrochemical response (LPR and EIS) were evaluated in an integrated manner. The results show that low Cl− concentrations favour a regime dominated by general corrosion, whereas increasing chloride contents induce a progressive transition towards localized corrosion, with maximum pit depths of approximately 1–1.5 mm after 12 weeks and a clearly higher susceptibility of carbon steel compared with ductile iron. Moreover, increasing chloride content significantly alters rust mineralogy, promoting the formation of chlorine-rich phases such as β-FeOOH, which are highly porous and electrochemically active, capable of retaining Cl− within their structure and maintaining high potential gradients inside the corrosion layer. Thickness-loss fitting further reveals that, while the behaviour of ductile iron reasonably follows the classical Romanoff model, corrosion of carbon steel exhibits a bilinear response controlled by the temporal evolution of the oxide layer in the presence of chlorides, confirming the role of this anion as a primary controller of both corrosion kinetics and damage mode in salt-enriched soils.

In addition, certain ions present in the electrolyte, although of secondary importance in terms of overall corrosivity, must also be considered. Bicarbonate ions (HCO3−) play a key role in regulating pore-water pH and in the formation of partially protective films on steel, mainly through FeCO3 precipitation, inducing pseudo-passive states in solutions and soils with near-neutral pH [74]. However, their effect is markedly ambivalent: at low concentrations, they may promote active dissolution, whereas at higher concentrations they can inhibit localized corrosion even in the presence of chlorides, particularly under anaerobic conditions [74]. From a mechanistic standpoint, bicarbonate has been shown to compete with chloride for active surface sites, affecting both dissolution kinetics and the nature of corrosion products formed [69].

Nitrate ions (NO3−), in turn, exhibit a dual electrochemical behaviour, generally acting as inhibitors of localized corrosion through competitive adsorption against chloride and cathodic reduction processes involving proton consumption, thereby favouring repassivation of incipient pits [75]. However, their effect depends critically on potential, concentration and corrosion regime, and “dangerous inhibitor” behaviour has also been reported, whereby nitrate stabilizes dissolution within active pits and promotes localized corrosion under certain electrochemical conditions [75]. These aspects are particularly relevant in arid and hyper-arid environments, such as nitrate-rich soils in northern Chile, as well as in agricultural settings, where elevated NO3− concentrations may significantly influence corrosion processes through their interaction with chlorides, sulphates and bicarbonates.

Several studies have sought to elucidate the synergistic effects of different dissolved ions. In natural soils, the simultaneous presence of chlorides, sulphates, bicarbonates and nitrates creates an “ionic cocktail” whose effect on steel corrosion is not additive but strongly non-linear and dependent on the relative proportions of the anions involved [69,76]. Investigations in simulated soil solutions show that the interaction between Cl− and HCO3− may lead either to pseudo-passivation or to abrupt increases in corrosion rate and deep pitting, depending on their relative concentrations [69,74]. Similarly, the co-presence of HCO3−, Cl− and SO42− substantially modifies iron dissolution kinetics and corrosion product composition, with sulphates playing a particularly aggressive role and bicarbonate exerting a moderating effect through competitive adsorption [69,74]. In real soils, these effects are amplified by soil mineralogy and chemistry, such that elevated concentrations of chlorides and sulphates in combination significantly accelerate degradation of zinc coatings and reduce the service life of buried galvanized steels [5]. Superimposed on this scenario is the dual behaviour of nitrates, which may either inhibit localized corrosion or, under certain potential and concentration conditions, stabilize dissolution within active pits and promote their propagation [75].

From an applied perspective, this complexity has direct implications for the design and assessment of buried metallic structures in photovoltaic power plants, where the coexistence of saline soils, agricultural irrigation, nitrogen fertilization and seasonal moisture variations favours environments with high concentrations of Cl− and SO42− combined with HCO3− and NO3−. Under such conditions, limiting soil characterization to global parameters such as pH or resistivity is clearly insufficient. Instead, specific determination of chloride, sulphate, bicarbonate and nitrate contents is required to inform more realistic corrosivity and service-life models, as well as to guide the selection of appropriate coatings and mitigation measures. Moreover, the planning of driven foundations should integrate criteria of ionic compatibility between backfill materials, intersected lithologies and irrigation water, in order to minimize local compositional contrasts that may promote the formation of geological corrosion cells and intensify localized attack on buried structural elements.

Despite the extensive body of experimental evidence addressing the role of chlorides and sulfates in soil corrosion, several critical gaps remain from an engineering and design perspective. First, a large proportion of available studies are based on aqueous solutions or artificially prepared soils, limiting the direct transferability of their findings to heterogeneous natural soils under field conditions. Second, while the aggressive role of Cl− and SO42− is well established, their influence is rarely translated into quantitative parameters suitable for durability design, such as corrosion-rate modifiers or service-life reduction factors. Third, the combined and often non-linear interaction between chlorides, sulfates, soil moisture, aeration and buffering capacity remains insufficiently addressed in existing standards and predictive models. These gaps underline the need for engineering-oriented frameworks capable of integrating ionic effects into practical corrosion assessments for buried structures in photovoltaic plants.

2.3. Biological, Environmental and Geological Influences

2.3.1. Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion (MIC)

Microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC) is defined as the accelerated degradation of metallic materials driven by the activity of microbial communities developing at the metal–environment interface, without altering the fundamental electrochemical principles of corrosion, but decisively modifying anodic and cathodic kinetics [77,78]. In soils and buried environments, the most relevant forms are anaerobic MIC associated with sulphate-reducing bacteria (SRB), which are capable of using steel as an electron donor and sulphate as a terminal electron acceptor, and MIC linked to nitrate-reducing bacteria (NRB), which couple nitrate/nitrite reduction to iron oxidation through extracellular electron transfer processes and cathodic biocatalysis [79,80]. Recent studies converge in showing that the biofilms formed by these microorganisms generate microenvironments that differ markedly from the bulk electrolyte in terms of pH, redox potential and the activity of aggressive species, typically promoting pitting corrosion and highly localized attack [77,78,81].

In the context of buried structures, including pipelines and metallic foundations, MIC is particularly relevant in fine-grained, poorly aerated soils rich in sulphates or nitrates, where redox conditions favour the proliferation of SRB and NRB and the formation of dense biofilms on the metal surface [79,80,81].

2.3.2. Hydro-Climatic and Temperature Effects on Soil Corrosion

Temperature and seasonal variations simultaneously modify soil moisture, electrical resistivity and the degree of aeration, such that the corrosion of buried structures responds to a clearly dynamic environment rather than to stationary conditions. Controlled tests using carbon steel coupons buried in sand at different moisture contents show that moisture governs soil resistivity, the exposed active area and the nature of the corrosion products, thereby controlling both the instantaneous corrosion rate and the residual rate under cathodic protection [28,55]. Complementarily, studies on X70 steel in near-neutral pH formation waters demonstrate that the effect of temperature on corrosion is non-monotonic: the corrosion rate initially decreases and then increases again with rising temperature, while a transition from predominantly uniform corrosion (30–90 °C) to localized corrosion (≥120 °C) occurs, associated with changes in the morphology, compactness and internal stresses of the FeCO3 film [82]. Nevertheless, the temperature ranges typically associated with soils fall within the regime of predominantly uniform corrosion according to the classification of Chen et al. Recent tests on API 5L X60 steel in solutions simulating low-resistivity soils confirm that corrosion intensifies with increasing temperature in the 20–60 °C range, with marked increases in corrosion current density and decreases in polarization resistance, allowing the environment to be classified as highly corrosive even for relatively short exposure times [83].

Further investigations conducted on artificial soils subjected to wetting–drying cycles confirm that, under conditions of high moisture and low aeration, corrosion rates remain relatively low (≈20–30 μm·a−1), but can increase by one to two orders of magnitude during drying phases, when the fraction of active surface increases and differential aeration cells are intensified [25]. Taken together, these results indicate that the combination of moisture–drying cycles and seasonal temperature fluctuations can markedly modify the corrosion regime and the effectiveness of corrosion product layers throughout the year.

From a systemic perspective, recent analyses based on fault-tree methods and multi-criteria prioritization approaches confirm that soil resistivity—and therefore corrosive aggressiveness—is only significantly altered when moisture, temperature and soil chemistry interact simultaneously, with climate acting as the primary modulator of this interaction [84]. This observation is fully consistent with seasonal field-monitoring studies, which reveal well-defined annual cycles in soil resistivity, with peaks in corrosion vulnerability occurring at specific times of the year [85,86]. Overall, the experimental evidence indicates that both thermal evolution and seasonal variations in moisture and aeration must be explicitly considered in the assessment of soil aggressiveness, as they govern not only the corrosion rate but also the transition between uniform and localized corrosion regimes in buried structures [25,26,28,83].

2.3.3. Geological Configurations

The geological configuration of the subsurface directly governs the corrosivity of the environment by controlling the spatial distribution of the physical and geochemical properties of the soil, such as oxygen transport pathways, moisture retention, the distribution of dissolved salts, active mineralogy, electrical resistivity and the degree of aeration. Lithological heterogeneity gives rise to non-uniform electrochemical environments in contact with a single metallic structure, favouring the establishment of corrosion macrocells associated with local potential differences [87,88].

Numerous experimental studies have demonstrated that soils with different mineralogical compositions induce markedly different electrochemical behaviours even under comparable environmental conditions. Comparative tests on carbon steels exposed to sandy, clayey and loamy soils show that sandy soils, despite their higher aeration, can develop high corrosion rates when significant levels of dissolved salts and high ionic mobility are present, whereas clayey soils tend to promote low-aeration conditions, high moisture retention and strongly localized corrosion [22,23].

The fine fraction of the soil, and particularly clay mineralogy, plays a decisive role in this behaviour. Expansive minerals such as montmorillonite exhibit a high water-retention capacity, which reduces oxygen permeability, lowers electrical resistivity and favours the development of differential aeration cells, thereby increasing the susceptibility of steel to localized attack [42,88]. In contrast, minerals such as kaolinite, with a lower swelling capacity, display more moderate corrosive effects under equivalent moisture conditions.

The work of Liu et al. further demonstrates that the effective thickness of the soil layer covering the metallic structure constitutes a critical geo-electrochemical parameter. In clayey soils, a critical thickness—of the order of 5 mm—exists at which the corrosion rate is maximized as a result of the balance between water-retention capacity and the barrier effect to oxygen diffusion; above this thickness, diffusive blocking dominates, whereas below it rapid drying of the metal–soil interface prevails [44].

From a broader perspective, regional characterization studies have shown that spatial variability in soil properties at the site scale generates clearly differentiated corrosivity domains. Cheng He et al. (2025) [89] demonstrate that even within the same geographical region, there are significant contrasts in pH, moisture, salinity and resistivity, which translate into markedly different corrosion responses of buried galvanized steel, with progressive degradation of the zinc coating and an early transition to corrosion of the steel substrate in the most aggressive soils.

A particularly relevant aspect of complex geological configurations is the formation of natural galvanic cells between zones of the same metallic element in contact with lithologies of different permeability and aeration. Coupled numerical models of oxygen transport and electrochemical reactions show that small contrasts in porosity, saturation or surface coverage are sufficient to induce persistent corrosion macrocells, which are responsible for a significant proportion of localized failures in buried pipelines [87]. This same mechanism has been corroborated experimentally in sand–clay systems subjected to wetting–drying cycles, where intense galvanic coupling develops between aerated and deaerated zones of the steel [25,26].

In soils disturbed by earthworks, artificial backfills or excavations, modification of the original geological structure further exacerbates this problem. The mixing of materials with different grain-size distributions, the loss of natural compaction and the creation of artificial lithological interfaces generate abrupt gradients in moisture, oxygen and resistivity, increasing the likelihood of severe differential corrosion [88,90]. This issue is particularly critical in extensive infrastructures such as photovoltaic parks, where the mass driving of metallic profiles intersects successive lithological units with distinctly different electrochemical behaviours.

Overall, experimental and modelling evidence indicates that geological configuration not only conditions the mean values of soil corrosivity, but also decisively governs the spatial localization of damage, the development of persistent macrocells and the transition from relatively uniform corrosion regimes to highly localized and difficult-to-mitigate processes using conventional protection techniques [25,44,87,89].

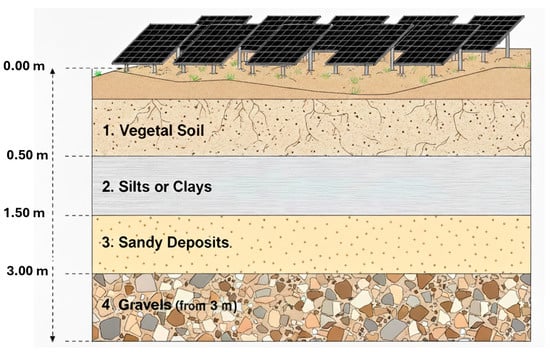

In practical photovoltaic installations, a recurring geological configuration consists of a shallow layer of topsoil or engineered fill, typically extending from the surface to depths of approximately 0–0.4 m, underlain by fine-grained silts and clays commonly encountered between about 0.5 and 1.5 m. Beneath these cohesive materials, sandy horizons are frequently present from roughly 1.5 to 3.0 m depth, often grading into gravelly deposits or sand–gravel mixtures at greater depths (Figure 3). Driven steel foundations routinely intersect several of these lithological units simultaneously. Due to the pronounced contrasts in permeability, moisture retention and oxygen diffusion, sandy and gravelly layers tend to remain relatively well aerated and preferentially act as cathodic regions where the oxygen reduction reaction is favoured, whereas clay- and silt-rich layers exhibit higher moisture retention, reduced aeration and preferentially behave as anodic zones. This vertical juxtaposition of lithologies with contrasting electrochemical behaviour promotes the formation of persistent geological galvanic cells along a single structural element, concentrating anodic dissolution within the fine-grained layers and significantly increasing the risk of localized corrosion by differential aeration, even in sites where average soil parameters would otherwise suggest moderate corrosivity.

Figure 3.

Representative geological stratigraphy in photovoltaic plant sites.

3. Engineering Approaches to Soil Corrosion Prevention and Mitigation

3.1. Purpose and Methodology

The assessment of soil corrosivity in photovoltaic power plants constitutes a critical step in defining the protection strategy for driven metallic foundations, ensuring that the structure achieves its design service life under controlled risk conditions and with a reduced total cost. Such an assessment requires a methodological approach capable of integrating the complex interaction between geochemical, hydro-climatic and geological parameters governing corrosion in soils, as demonstrated from the pioneering studies of Romanoff (1957) [20] to more recent works revealing the pronounced non-linearity between moisture, electrical resistivity, pH and aggressive anions [5,60,69,72,74].

Rather than reproducing an exhaustive review—often redundant and of limited value for engineering decision-making due to the dispersion of existing criteria—this work proposes an operational methodological framework grounded in experimental evidence and standards. This framework focuses on the two essential elements of any durability assessment in soils: (i) estimating the service life of metallic coatings, both hot-dip galvanized (HDG) and ZnAlMg alloys, and (ii) determining the required steel over-thickness, beyond structural design requirements, for each surface exposed to the soil.

The formulation of this approach is supported by studies documenting how zinc and steel corrosion in soils is governed by the simultaneous interaction of parameters that are rarely captured by simplified schemes. The coupled influence of resistivity, moisture and pH, together with the destabilizing action of chlorides and the non-protective nature of corrosion products formed in the presence of sulphates, has been demonstrated in recent investigations, underscoring the need for genuinely multivariable methodologies [68,69,72,74,91].

3.2. Calculation of Soil Corrosivity Load

The first step of the procedure consists of determining the soil corrosivity category through the application of DIN 50929-3:2024-05 [12], which provides one of the most comprehensive frameworks currently available by integrating physical, chemical and electrochemical soil parameters. The use of alternative methodologies based on a limited number of variables, leading to qualitative classifications without quantifiable outputs, is insufficient to fulfil the durability assessment objectives defined in this work.

A rigorous application of the DIN standard requires the determination of fifteen soil parameters (Z1–Z15), implying that the geological and geotechnical investigation must encompass not only conventional geotechnical characterization, but also a soil sampling and geochemical testing programme specifically designed to capture the spatial variability of the site. Recent studies have demonstrated that the omission of some of these parameters—particularly those related to soluble salts, buffer capacity and depth-representative resistivity—introduces significant uncertainty into corrosivity classification [89].

As a second pillar of the procedure, the analytical methods defined in DVGW GW 9 (A) (2021) should be applied. This standard establishes detailed protocols for the preparation of representative samples and specifies the chemical analyses of soils, with Annex B and Table B.1 being of particular relevance. The content of neutral salts (chlorides and sulphates in aqueous extract), sulphates in acidic extract, soil buffer capacity (alkalinity at pH 4.3 and acidity at pH 7.0), and sulphide content constitute fundamental geochemical parameters for assessing environmental aggressiveness [92].

The in situ determination of electrical resistivity using the four-pin Wenner configuration should focus primarily on the depth interval between 0.5 and 3.0 m, while simultaneously recording the soil moisture condition at the time of measurement. Anomalies detected within the critical depth range of 1.0–2.0 m should be investigated in detail, given their potential impact on the formation of corrosion macrocells. These field measurements should be complemented by laboratory soil-box tests conducted in accordance with ASTM G57 [93], varying the moisture content across the minimum and maximum range expected at the site. Recent literature emphasizes that assigning a central role to resistivity in corrosion rate estimation, while limiting its measurement to isolated and non-representative surveys, leads to erroneous assessments of corrosion risk [58,61,94].

Systematically, parameter Z15—the structure-to-soil potential measured using a saturated Cu/CuSO4 reference electrode—is often not determined, despite its relevance for identifying whether the structure already lies within an electrochemical domain of active corrosion. Moreover, comparing this parameter before and after commissioning of the plant allows the potential influence of interactions between the grounding system and stray currents to be assessed, an aspect of critical importance from the perspective of corrosion warranties in structural supply contracts.

3.3. Galvanized Coating Durability Determination

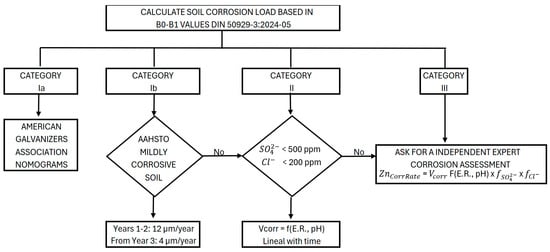

Once the soil corrosivity category has been established in accordance with DIN 50929-3:2024-05 [12], it will fall into one of the four defined classes Ia, Ib, II or III, as specified in Table 4 of the standard.

After assigning the soil to a corrosivity category under DIN 50929-3 (Ia, Ib, II or III), the first level of verification consists of assessing whether the soil meets the AASHTO criteria for mildly corrosive environments (Table 1). When electrical resistivity, pH, organic matter content, chloride content and sulphate content remain below the specified threshold values, experimental evidence indicates that the corrosion rate of galvanized steel typically does not exceed approximately 12 μm·a−1 during the first two years of exposure, subsequently decreasing to values on the order of 4 μm·a−1 until depletion of the coating, in agreement with the historical test programmes conducted by the NBS and the FHWA [20,69,95].

Table 1.

AAHSTO limits of Mildly Corrosive Soils.

In cases where the soil does not meet the AASHTO criteria, the assessment must rely on an explicit estimation of the zinc corrosion rate, considering soil electrical resistivity and pH as independent variables. The representative resistivity should correspond to the depth interval between 1 and 2 m and should account for both dry and wet hydric states of the site. When a sufficient number of samples is available, it is advisable to use statistically representative values, such as the mean value and the mean minus one standard deviation, in line with recommendations derived from studies addressing the seasonal and spatial variability of soils [58,61,86].

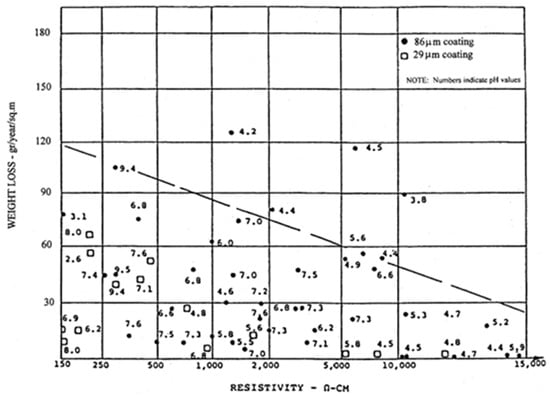

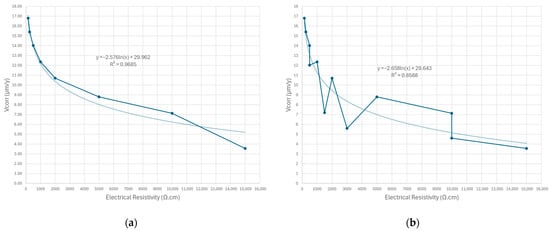

Several studies have proposed correlations between resistivity, pH and the corrosion rate of galvanized steel, among which the classical work of Frondistou-Yannas (1985) [95] stands out. Its results are adopted here as a reference to define the functional framework of the estimation (Figure 4). However, the corrosion rate obtained in this way must be corrected to account for the specific influence of chloride and sulphate contents in the soil, as both ionic species have been shown to significantly affect the stability and the protective nature of zinc corrosion products [5,72,74,91,92].

Figure 4.

Corrosion rate of galvanized steel as a function of electrical resistivity and pH [95].

The experimental data reported by Frondistou-Yannas [95] and Romanoff [20], which are widely used as reference benchmarks in soil corrosion studies, allow an empirical relationship to be established between soil electrical resistivity and the corrosion rate of galvanized steel. On this basis, the fitting functions shown in Figure 5 are proposed.

Figure 5.

Corrosion rate of galvanized steel as a function of soil electrical resistivity: (a) Frondistou-Yannas model [95] for a wide pH range (2.6–9.5); (b) integrated Frondistou-Yannas [95] and Romanoff dataset [20] highlighting alkaline soil conditions. Own elaboration based on the experimental data reported by Frondistou-Yannas and Melvin Romanoff.

Once the corrosion rate of galvanized steel has been estimated using any of the functions indicated (Figure 5), or alternative correlations reported in the scientific literature, the influence of sulfate and chloride contents in the aqueous soil extract must be incorporated by applying penalty factors for sulfates and chlorides .

The penalty factor proposed by Arzola et al. [92] for sulfate contents above 1500 ppm reaches values of up to , while for chloride contents exceeding 1100 ppm, Song et al. [72] proposed a factor of . Although the literature reports penalty factors for high concentrations of sulfates and chlorides, experimental evidence indicates that these coefficients are not universal and depend strongly on the specific soil–metal system under consideration. For this reason, the multiplicative factors associated with sulfates and chlorides should preferably be determined through dedicated electrochemical studies, avoiding their indiscriminate application outside the experimental context for which they were originally derived.

The expression proposed to penalize the zinc corrosion rate as a function of sulfate content is given in Equation (3). In the absence of experimental data, a suggested range for is 0.15–0.35, with a default value of 0.25. The proposed reference sulfate concentration, , is 200 ppm, corresponding to the upper limit of an AASHTO mildly corrosive soil.

For chlorides, the suggested range for is 0.30–0.60, with a default value of 0.40. Analogously, the proposed reference chloride concentration, , is 100 ppm, corresponding to the upper limit of an AASHTO mildly corrosive soil.

The multiplicative factors associated with sulfates and chlorides should preferably be determined through dedicated project-orientated electrochemical tests using ER/LPR/EIS techniques.

An appropriate procedure is to prepare an aqueous soil extract to be used as a reference sample, fixing the temperature and pH to desired values. A set of solutions with different sulfate and chloride contents, buffering the pH to the fixed value, will be prepared from the reference sample. For the measurements, a three-electrode cell constituted by a working electrode of the HDG or ZM coated sample to be investigated, an Ag/AgCl reference electrode and a graphite or stainless-steel counter electrode will be used. By means of a potentiostat, ER/LPR and EIS measurements will be performed with each prepared solution.

The application of the Stearn–Geary equation icorr (A/cm2) can be estimated (Equation (5)) once the Rp (Ω.cm2) (Equation (6)) and the B (V) value are calculated with the anodic and cathodic Tafel slopes (Equation (7)).

Once icorr is determined, the zinc corrosion rate can be calculated by application of (Equation (8)).

E.W. = Equivalent Weight.

The zinc corrosion rate, , estimated from Figure 5 or using Equation (8) if the information is available, should then be increased by multiplying it by the penalty factors calculated according to Equations (3) and (4).

As a final consistency and conservatism check, the corrosion rates obtained from resistivity–pH correlations and salt penalty factors are benchmarked against the classical National Bureau of Standards (NBS) soil corrosion model. This model, derived from long-term burial tests conducted by Romanoff and subsequent FHWA programmes, provides an upper-bound envelope for metal loss in corrosive soils and is widely regarded as a worst-case estimate for durability-oriented design. The corrosion rate obtained after applying the salt penalty factors according to Equation (9) must be benchmarked against the results derived from the NBS model for corrosive soils, using both the mean (Equation (10)) and the maximum (Equation (11)) expressions for zinc.

X = coating loss per exposed side in microns.

t = exposition time in years.

The resulting corrosion rate should finally be compared with the estimates provided by the NBS model, which represents a conservative envelope based on extensive historical experimental programmes [20]. This comparison ensures that the calculated values do not underestimate the most unfavourable scenario.

The calculations presented herein refer to hot-dip galvanized (HDG) coatings. If the piles were protected with ZnAlMg (ZM) alloy coatings, it would be necessary to estimate the durability multiplication factors of ZM coatings relative to conventional HDG or pure zinc coatings. Available studies [96,97,98] indicate that the durability multiplication factor of ZM coatings typically ranges between 1.5 and 2.5 with respect to galvanized coatings. The appropriate multiplication factor should, however, be determined through dedicated experimental testing.

Overall, the procedure described provides a coherent and traceable framework for estimating the durability of galvanized coatings as a function of soil corrosivity load, integrating normative criteria, experimental evidence and mechanistic understanding. The proposed approach establishes a clear decision-making sequence that discriminates between low-aggressiveness soils, where simplified criteria may be applied, and more severe scenarios, in which the explicit influence of electrical resistivity, pH and aggressive ionic species must be incorporated. This methodological workflow, which systematically links soil classification to the estimation of zinc corrosion rate, is schematically summarized in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Proposed methodology to estimate zinc coating durability.

3.4. Determination of the Required Overthickness to Achieve the Target Durability

Once the thickness loss of the metallic coating has been estimated using the methodology described in the previous section, the effective service life of the galvanized or ZnAlMg coating in contact with the soil can be evaluated. When the predicted coating lifetime is shorter than the target design life of the project—typically 25, 30 or 35 years in photovoltaic plants—the resulting time deficit must be compensated by introducing an additional base steel overthickness, beyond that required by structural design criteria.

This approach explicitly recognizes that, once the coating has been consumed, the carbon steel is directly exposed to the soil environment and its corrosion rate becomes governed by the properties of the surrounding edaphic medium. Under these conditions, DIN 50929-3:2024-05 [12] provides a quantitative framework for estimating the corrosion rate of bare steel as a function of the B0 and B1 parameters, which condense the overall soil aggressiveness in a simplified manner (Table 2).

Table 2.

Bare Steel Corrosion Rate as a function of B0 and B1 values. Source: DIN 50929-3:2024-05 [12].

Table 2 summarizes the typical corrosion rates of carbon steel specified by the standard for different ranges of B0 and B1, with values ranging from approximately 2 μm·a−1 in mildly aggressive soils to values of the order of 60 μm·a−1 in highly corrosive soils.

The calculation of the required overthickness is therefore based on a clearly defined logical sequence: (i) determining the period during which the metallic coating provides effective protection; (ii) identifying the residual service period during which the steel is directly exposed to the soil; and (iii) applying the corrosion rate corresponding to bare steel, according to the DIN classification, to estimate the cumulative thickness loss over that period.

This approach introduces a clear conceptual separation between the coating-protection phase and the subsequent exposure phase of the base steel, thereby avoiding inappropriate extrapolations of zinc corrosion models to the behaviour of carbon steel. Several studies have emphasized the importance of this distinction, particularly in soils where aggressiveness may increase markedly after the loss of the protective layer due to the activation of corrosion macrocells and interaction with moisture and aeration gradients [25,26,60].

From a design perspective, the use of standardized corrosion rates for bare steel provides a conservative and traceable framework, consistent with established durability engineering practice. Nevertheless, it should be noted that, as in the case of galvanized steel, these rates represent average values and that, in highly heterogeneous soils or under pronounced wet–dry cycling, localized increases in metal loss may occur. This reinforces the need to apply appropriate safety factors or complementary mitigation strategies [58,86].

Accordingly, steel overthickness should not be regarded as a substitute for appropriate coating selection or rigorous soil characterization, but rather as an additional durability assurance measure. This hybrid approach—combining coating protection with a thickness reserve—is particularly well suited to photovoltaic plants, where the high repetition of driven elements and the difficulty of post-installation interventions necessitate a robust design capable of accommodating unfavourable corrosion scenarios.

4. Discussion

Before entering the discussion of applicability, limitations and future developments, it is important to explicitly delineate the scope of the authors’ contribution relative to existing standards and prior literature. While the present work builds upon well-established normative frameworks (DIN 50929-3, DVGW GW 9, AASHTO and NBS) and a broad body of experimental corrosion research, its primary contribution lies in the structured integration of these elements into a coherent, design-oriented workflow tailored to photovoltaic installations. Table 3 summarizes the origin of the methodological components employed in this study, distinguishing between elements adopted from standards or literature and those newly proposed or refined by the authors. This synthesis is intended to clarify the transition from the review sections to the engineering framework and to provide a transparent basis for the subsequent discussion.

Table 3.

Origin of methodological elements used in the proposed engineering framework.

4.1. Applicability and Limitations of DIN and DVGW in PV Contexts

The proposed methodological framework is grounded on DIN 50929-3 and DVGW GW 9 as reference standards for soil corrosivity classification and analytical procedures. These documents provide one of the most comprehensive and structured parameter sets currently available, integrating physical, chemical and electrochemical descriptors of soil aggressiveness. Nevertheless, their application is subject to inherent assumptions and limitations when extended to large-scale photovoltaic (PV) installations and heterogeneous soil environments.

Both standards are fundamentally based on discrete soil sampling and quasi-static parameter evaluation, implicitly assuming that measured values are representative of the long-term exposure conditions. As a consequence, spatial variability, seasonal moisture fluctuations, transient wet–dry cycles and progressive climate-driven changes in soil temperature and hydrology are only partially captured. This limitation is particularly relevant in PV projects, where extensive footprints, repetitive driven foundations and shallow burial depths amplify the influence of local heterogeneities and temporal variability on corrosion processes.

In photovoltaic installations, metallic foundations frequently intersect multiple lithological units with contrasting permeability, moisture retention and aeration properties. Under these conditions, averaged soil parameters may underestimate the formation of macrocells driven by differential aeration or moisture gradients, which are known to control localized corrosion severity. In addition, projected climate trends, such as increased rainfall intensity, prolonged drought periods or shifts in seasonal patterns, may modify soil resistivity, oxygen availability and electrolyte chemistry over the service life of the structure, thereby affecting corrosion kinetics beyond the initial classification stage.

In this context, the characterization of soil corrosivity cannot rely on fixed or uniformly distributed sampling densities, as corrosion drivers in photovoltaic sites behave as spatially heterogeneous fields rather than as homogeneous parameters. Methodologies commonly adopted in environmental geochemistry and applied geophysics—such as geostatistical site characterization, progressive or adaptive sampling, and multi-scale electrical resistivity surveying—explicitly address this variability by combining an initial screening phase with targeted densification in anomalous zones. In practice, low-density reconnaissance surveys are first used to identify spatial trends and domains with contrasting resistivity, moisture or salinity, followed by focused investigations in areas exhibiting strong gradients, lithological transitions or conflicting corrosivity indicators. This adaptive approach improves the representativeness of the parameters used for soil classification, while reducing both the risk of underestimating localized corrosion phenomena and the inefficiency associated with uniform oversampling of comparatively homogeneous soil domains.

Within this normative context, corrosion rates—particularly for bare carbon steel following coating depletion—are treated as time-averaged design values rather than mechanistic descriptors of instantaneous corrosion kinetics. This assumption reflects standard engineering practice and is consistent with the intent of DIN 50929-3, whose corrosion rates are derived from long-term field observations and are intended to provide conservative estimates for durability-oriented design. Although real corrosion rates may exhibit significant temporal variability due to wet–dry cycling, microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC) or transient aeration effects, the use of averaged normative values avoids extrapolating zinc corrosion models to bare steel behaviour and introduces an implicit safety margin when combined with upper-bound corrosion classes and steel overthickness.

The proposed roadmap explicitly acknowledges these constraints and defines its intended applicability range. Corrosion rates are treated as time-averaged design values, consistent with normative practice and long-term field observations, but not intended to resolve short-term transients, microbiologically influenced corrosion peaks or extreme site-specific anomalies. Within this context, the methodology promotes PV-adapted refinements that remain fully compatible with existing standards, including (i) multi-depth and spatially distributed resistivity measurements performed under representative wet and dry conditions; (ii) systematic determination of the structure-to-soil potential (Z15) prior to and after plant commissioning; and (iii) conservative cross-checking of calculated corrosion rates against upper-bound NBS models.

These adaptations do not replace the underlying standards but enhance their robustness and transparency when applied to PV-specific conditions. At the same time, they delineate clear boundaries for the use of the proposed framework, highlighting scenarios—such as highly heterogeneous soils, pronounced seasonal cycling or environments prone to MIC—where complementary monitoring, site-specific testing or adaptive design margins may be required.

4.2. Sensitivity to Penalty Factors and Uncertainty

The correction of the base zinc corrosion rate through penalty factors accounting for sulfate and chloride contents is implemented via the multiplicative formulation expressed in Equations (3), (4) and (9). In this framework, the corrosion rate of the zinc coating is obtained as the product of a base corrosion rate derived from resistivity–pH correlations and two independent penalty factors associated with sulfate and chloride concentrations, respectively.

The functional form adopted for the penalty factors (Equations (3) and (4)) introduces a logarithmic dependence on the ratio between the measured ion concentration and a reference value representative of mildly corrosive soils. This formulation reflects experimental observations reported in the literature and ensures that the influence of aggressive anions increases in a non-linear yet bounded manner. As a result, uncertainties in ion concentration measurements or in the selected penalty coefficients translate into proportional variations in the estimated corrosion rate, avoiding unrealistic amplification effects.

Once the corrected zinc corrosion rate Vcorr is obtained from Equation (9), the service life of the coating is obtained from Equations (10) and (11). The service life of the coating (tZn) can be estimated by a linear thickness-consumption approach, assuming uniform corrosion of the coating:

where is the effective zinc coating thickness per exposed face, expressed in micrometres. Although simplified, this relationship is widely adopted in durability-oriented design and provides a transparent link between soil corrosivity and coating lifetime.