Featured Application

The proposed approach permits a semi-quantitative analysis of the stability of thermoplastic polymers during their thermo-mechanical processing and enables an evaluation of the efficiency of thermal stabilizers. The approach will help in the selection of polymeric materials and additives and will guide the optimization of polymer formulations for an improved processability and thermal performance. Potential applications include the design of more robust and sustainable bio-based materials for melt extrusion, blending, compounding, film fabrication, and other related technologies.

Abstract

Stabilizing thermoplastic polymers against thermal degradation is an important aspect that must be addressed during material development and becomes critical in the case of bio-polymers, which often reveal reduced thermal stability and a narrow processing temperature window. Herein, we propose a new methodology to analyze and compare the thermal stability of thermoplastic materials, exampled by several types of bio-polyesters, such as aliphatic PBS and PBSA, aliphatic-aromatic PBAT and PBST, and amorphous PHBV, and evaluate the impact of thermal stabilizer on their processability and thermal stability. The proposed method relies on multi-step torque rheometry experiments that involve controlled cycling of the tested material under varied thermal conditions, shear forces, and processing times to acquire and evaluate the changes in flow behavior of the sample after its processing. By monitoring polymer melt behavior and comparing the changes before and after repetitive processing steps, we can gain valuable insights into the material performance and stabilizing efficiency of additives. The thermal stability of polymers and the efficiency of thermal stabilizers can be assessed by means of the relative change in temperature-normalized torque, , measured after different processing steps. Significantly, we demonstrate that the obtained values correlate with changes in the molar mass of neat polymers as a result of their processing. The proposed approach enables a semi-quantitative evaluation of the thermal stability of various polymers and the study of the efficiency of thermal stabilizers and their performance, providing a robust strategy for optimizing compound formulations, particularly regarding the optimal fractions required.

1. Introduction

Bio-polyesters (BioPESs) are gaining increasing relevance in polymer research and industrial applications, driven by the demand for sustainable materials with conventional thermoplastic processability. Their growing use in melt-based technologies calls for robust analytical methods to evaluate processing behavior under realistic conditions. Torque rheometry tests using an internal laboratory mixer are one of the widely used methods in the field of polymer melt processing to study and simulate processes under conditions that resemble real processing scenarios [1]. These rely on measuring the response of polymer melt subjected to shear forces in order to evaluate its rheological and flow behavior. While capillary viscometry provides information on steady-state shear viscosity under idealized flow conditions, torque rheometry reflects realistic processing conditions by accounting for shear and thermal stress during blending, compounding, or extrusion steps.

Torque rheometry is a simple, reliable, and industry-ready method, which has been used to evaluate the mixing efficiency during polymer blending [2,3], investigate cross-linking processes [4], analyze the thermal stability and degradation of (bio)polymers, their blends, and (bio)composites [5,6,7,8,9], and optimize formulations and processing conditions [10,11]. The primary measured response is the torque (), which is related to the polymer melt viscosity and influenced by several key factors, including the shear rate, temperature, material molecular weight, and material stability. The second recorded parameter is the melt temperature (), which evolves as result of the temperature setting for the mixing chamber () and through the heat produced due to the shear. While torque rheometry is not best suitable for determining the absolute viscosity of materials, it permits comparative studies to determine the effects of the sample composition and processing condition on its viscosity and to derive correlations with respect to its molar mass [5].

The impact of mechanical energy on polymer degradation during melt processing can be divided into two distinct effects: (I) the temperature rise caused by viscous energy dissipation, which accelerates thermally induced degradation reactions; and (II) the shear stress resulting from mechanical forces, which leads to chain scission [12]. In thermoplastic processing such as extrusion or injection molding, both effects contribute to polymer degradation at different scales. During melt processing, polymers can degrade by different mechanisms, namely by thermal degradation, where thermal energy causes chain scission or radical formation, by thermal–oxidative degradation, and by thermo-mechanical degradation, where mechanical/shear stresses in the melt lead to chain scission, often in combination with heat.

Depending on the polymer type, applied temperatures, screw configuration, and rotation speed, either thermo-oxidative or thermo-mechanical degradation may dominate [13]. Some bio-polyesters possess a narrow processing window due to the proximity of their melting and decomposition temperatures [14]. As a result, even small deviations in processing conditions may lead to accelerated degradation, adversely affecting material performance. Optimizing processing conditions is therefore indispensable to minimize degradation and maintain the desired material properties, in addition to the application of stabilizers, flow modifiers, and other processing aids.

The potential of torque rheometry to quantify and compare the stability of polymeric materials against degradation, or quantitatively evaluate the efficiency of stabilizers, has not been fully explored. Significant steps in this direction have recently been made by several research groups [5,6,7,15,16,17,18]. The approach to correlate the changes in polymer melt viscosity and its molecular weight during material processing in a batch mixer (Haake™ Rheomix® 3000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) was proposed by the Canedo group [17]. The authors derived mathematical models for torque and melt viscosity by combining the Carreau–Yasuda model and exponential expression for the shear rate and temperature dependencies, respectively (Equations (1) and (2)):

where are, respectively, the torque, viscosity, shear rate, and weight average molar mass, K is a constant that depends on the polymer type, is the reference temperature, and n and β are the pseudoplasticity coefficient and temperature sensitivity coefficient for viscosity, respectively.

The same research group also introduced a unitless parameter for comparing the relative increase () or decrease () in the molar mass of tested materials, in this case, neat PBAT versus PBAT mixed with Joncryl® chain extenders, assuming that indicates that the chain-extending effect of the additive was just sufficient to compensate for the degradation of the neat PBAT resin processed under the same conditions (Equations (3) and (4)) [18]:

While the proposed method provides the possibility to quantify process-induced changes in polymer molar mass using and data, it also requires additional parameters, namely and , which are not always available from the literature, for instance, in the case of blends, multi-component systems, or reactive mixtures. In the case of thermally unstable polymers, blends, or composites, both and will continue to change over time across the whole processing step, such that cases’ plateau region cannot be not reached within the experimental time scale [18]. In these, the most common cases, the respective terminal values, and , must be determined from the exponential regressions (Equations (5) and (6)):

where and are, respectively, the recorded temperature and torque, and are derived fit parameters. If materials with entirely different thermal stabilities must be compared, the comparisons based on terminal and are not fully consistent due to the very large difference in time required to reach steady-state regime.

While the approaches and models described above enable the analysis of changes in material properties caused by degradation, cross-linking, blending, or compounding, they rely on several approximations. In addition, they require material-specific parameters that are not always available in the literature and may be altered during material processing, blending, or compounding. These aspects impose certain limitations on the proposed models.

Herein, we propose a simple and efficient approach for the semi-quantitative evaluation of the thermal stability of thermoplastic polymers under various melt-processing conditions and for assessing the efficiency of thermal stabilizers. The method is based on multi-step torque rheometry tests, which can be conducted using a standard internal laboratory mixer, widely available in research institutions and industrial R&D divisions. Owing to its simplicity and practicality, this approach may be useful for researchers, polymer compounders, and product developers who routinely evaluate polymers and polymer-based formulations both at the laboratory and industrial scales.

2. Materials and Methods

Bio-polyesters (bioPESs) were obtained from different suppliers and used without purification. Poly(butylene succinate) and poly(butylene succinate-co-adipate) (ca. 20 mol% adipate), further denoted as PBS(1) and PBSA, respectively, were purchased from PTT MCC Biochem Co., Ltd. (Bangkok, Thailand). Another type of PBS, denoted as PBS(2), was purchased from Sipol SPA (Mortara, Italy). Poly(butylene succinate-co-terephthalate), denoted as PBST, is also a product of PTT MCC Biochem Co., Ltd., which was kindly provided free of charge by Mitsubishi Chemical Europe GmbH (Dusseldorf, Germany). Poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate), denoted as PBAT(1), was purchased from Corvay Specialty Chemicals GmbH (Hannover, Germany). Another type of PBAT, denoted as PBAT(2), was kindly provided free of charge by ClickPlastics AG (Bensheim, Germany). Amorphous poly(hydroxybutyrate-co-valerate) with ca. 30% hydroxyvalerate (HV) units, further denoted as PHBV, was purchased from CJ Europe GmbH (Frankfurt am Main, Germany). Commercial product names and material characteristics from technical data sheets are listed in Table 1. The thermal stabilizer (TS) Bruggolen® H175 was purchased from L. Brüggemann GmbH & Co. KG (Heilbronn, Germany) and used as received.

Table 1.

Material characteristics of bioPES products used in present work.

Multi-step torque rheometry experiments were carried out using a HAAKE™ PolyLab™ OS Modular Torque Rheometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) coupled with a Haake™ Rheomix® 600 batch mixer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The mixer was fitted with two roller-type rotors (model 557-1030, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) counter-rotating at a velocity ratio of 2:3. The free volume of mixing chamber with and without rotors was 69 and 120 cm3, respectively. The mixer chamber was preheated to a selected temperature () and then filled with the sample to be tested. Before loading, the resins were dried in a Digicolor dry air dehumidifying dryer at 60 °C for 4 h to remove residual moisture. The chamber loading was maintained at 70 ± 2 vol.%, as calculated from the material density values given in product data sheets, whereas the impact of additives (stabilizers) in calculations was neglected due to their low content. The sample was processed (kneaded) at a selected rotation speed () for a given period of time (t), and the melt temperature () and the torque () were recorded throughout the kneading process. The kneading process was repeated on the same sample over seven successive steps (S1–S7) under varied and settings, and and values were recorded throughout each processing step. The applied processing conditions are summarized in Table 2. Experiments on bioPES/TS mixtures were conducted in a similar manner. Pre-weighed bioPES resin was mixed with the required amount of TS, loaded into the preheated mixer chamber, and processed as described above. The TS fraction varied from 0.1 to 0.4 phr.

Table 2.

Applied t, N, and Ts, settings maintained during multi-step torque rheometry experiments.

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) measurements on raw products and processed samples were carried out using a 110 Series instrument from Agilent Technologies, Inc. (Santa Clara, CA, USA), equipped with an RI detector at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. For the SEC separation, a combination of PL-MIXED-B-LS (300 × 7.5 mm) and 10 µm PS gel columns (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used. The samples were dissolved in CHCl3 at room temperature to a concentration of ca. 3 mg/mL and filtered through a 0.2 µm PTFE syringe filter. The calibration was performed using PS standards.

3. Results

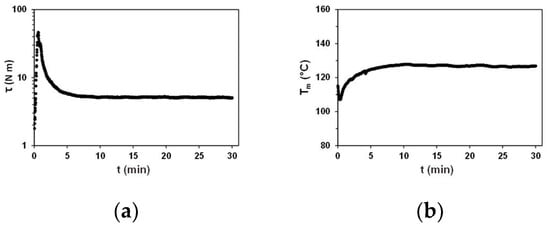

In Figure 1, the illustrative plots of and over time acquired during a standard, one-step torque rheometry experiment on the PBS(1) sample are shown. The initial sharp peak on the torque plot (Figure 1a) corresponds to the melting of solid polymer under heating and shear, which coincides with the minimum in the plot (Figure 1b). Once the polymer is completely molten, the torque starts to decrease and finally reaches a plateau. The shape of the curve mirrors the shape of the plot, thus first decreasing due to the polymer loading and melting process, then increasing due to the shear heating and viscous energy dissipation, and finally, leveling off at a plateau. In the terminal stage of the experiment, both plots reveal steady-state conditions with defined and stable terminal and values. Such conditions reflect features typical for the samples, which are thermally stable under the applied processing conditions. The melting peak is commonly excluded from quantitative analysis due to its high sensitivity to experimental variations and poor reproducibility. Instead, the decaying regions beyond the initial melting peak and the plateau regions in the and plots are evaluated while studying polymer melt behavior, chain degradation, cross-linking, or impacts of fillers and additives [5,17].

Figure 1.

Plots of (a) and (b) as function of time for neat PBS(1) at rpm and .

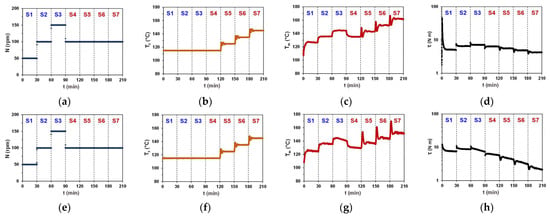

In Figure 2, the experimental results from multi-step torque rheometry tests conducted on PBS(1) and PBSA neat resins are presented, depicting and profiles, as well as and plots over time across the S1–S7 steps. During the initial three steps (S1–S3), was kept constant, while was varied. In the subsequent four steps (S4–S7), was kept constant, while was increased stepwise. We will first examine the similarities and differences in , , and plots recorded for both samples. As can be seen, at varied rotation speeds (S1–S4), the profiles remain straight lines (Figure 2b,f). However, periodic fluctuations in the plots appear after changing to a new setpoint (S5–S7). These fluctuations are present in all plots, regardless of the sample type, and result from the temperature equilibration process. Notably, similar fluctuations resembling a damped oscillatory pattern are also present in the plots, indicating their mutual origin (compare Figure 2c,g). Moreover, these temperature fluctuations also impact torque profiles (Figure 2d,h). Thus, the duration of each processing step was set to 30 min, aiming for smooth and profiles at the end of each step.

Figure 2.

Plots of (a,e) , (b,f) , (c,g) , and (d,h) over time across seven successive processing steps S1–S7 carried out on (a–d) PBS1 and (e–h) PBSA neat resins.

Next, both plots show similar trends, revealing a step-wise increase in terminal temperatures within S1–S3 steps performed at constant due to the heat release upon shearing, and also within S4–S7 steps carried out at a constant , being thus a combined effect of increased and heat release due to shearing. The profiles, however, differ significantly from each other. In the case of PBS(1) (Figure 2d), all processing steps end with flat plateaus and stable terminal torque values, indicating that a steady-state regime could be reached across the entire range of applied processing conditions. In the case of PBSA, however, a plateau region was reached at the end of the S1 step only, while torque continued to decay throughout all subsequent steps (Figure 2h). This indicates that temperature- and shear-induced changes in the melt flow behavior of PBSA persist throughout the S2–S7 steps without reaching steady-state conditions. Considering that and settings were identical in both experiments and plots exhibit similar trends, the differences in torque profiles may reflect the different thermal stability of tested materials under applied processing conditions.

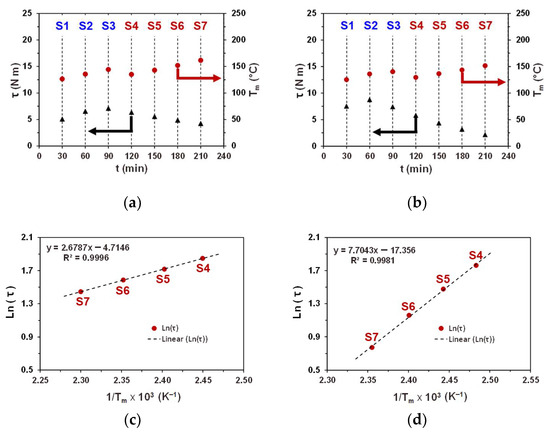

Figure 3a,b show the terminal and values for PBS(1) and PBSA polymers averaged over the last three minutes of each processing step. The corresponding numerical values of and , as well as and with their standard deviations, are listed in Table 3. The first difference appears in terminal torque values acquired at the end of the S1 step, which for PBSA is ca. 30% higher as compared to that of PBS(1). Considering that all other experimental conditions were identical in both cases, the impacts of shear rate, filling ratios, and heat transfer on the observed difference in can be ruled out. Taking into account that at the end of the S1 step, both samples reached steady-state conditions, with values very close to each other, the difference in should be due the difference in the intrinsic viscosities of PBS(1) and PBSA melts at a given .

Figure 3.

Plots of (a,b) terminal values of (red dots) and (black triangles) across S1–S7 processing steps and (c,d) Arrhenius plots of versus across S4–S7 processing steps at constant for (a,c) PBS(1) and (b,d) PBSA.

Table 3.

Applied N, and Ts setting and measured and values obtained from multi-step torque experiments on neat PBS1 and PBSA polymers.

The second important difference can be seen in the evolution of across successive processing steps. Both plots follow the same trend, first increasing from S1 to S3, then dropping from S3 to S4, and then increasing again from S4 to S7. However, the difference in between PBS(1) and PBSA samples increases steadily throughout the subsequent steps and reaches a maximum by the end of the experiment. Moreover, in case of PBSA, all steps end at a lower as compared to that determined for PBS(1). These observations clearly indicate a more intense heat release due to the shearing upon processing of PBS(1). The most significant difference arises from the changes in torque after different processing steps. The comparison of values at the end of the S2 and S4 processing steps performed under an identical and shows that the difference remains small for PBS(1) but drops by more than 25% for PBSA.

In Figure 3c,d, the dependencies of as a function of at the end of S4–S7 cycles are shown in Arrhenius coordinates for PBS(1) and PBSA samples. Both plots reveal a descent linear correlation between and , but exhibit nearly a three-fold difference in slopes, indicating significantly different temperature dependencies of melt viscosities.

The linear character of temperature dependencies indicates that within the applied temperature range, under a constant share rate () and given processing time, is the only parameter determining the terminal torque value and, thus, the melt viscosity of both samples. Given that current linear regressions involve only four data points, the deviations from linearity could be hidden, and the presented results should be regarded as semi-quantitative. However, considering that each data point in the plot represents the average value after a 30 min long processing step, we may expect that additional data points acquired at different temperatures within the applied temperature range will also likely follow the observed linear dependencies. Deviation from linearity would indicate the presence of other factors affecting the melt viscosity.

The Arrhenius-type dependency, as shown in Figure 3c,d, enables the determination of the temperature-corrected torque . This corresponds to the torque at the end of the selected processing step (S4), recalculated to the reference temperature, defined as the of the reference step (S2). This concept allows us to separate the impact of temperature from other factors influencing melt viscosity. Providing that both steps are carried out under the same shear rate, the absolute and relative changes in temperature-corrected torque could be determined as follows (Equations (7) and (8)):

The parameter is the analogue to the relative paramater used by Marniho et al. to evaluate relative changes in molar mass through the measured changes in torque [18]. Negative indicates a reduction in apparent viscosity during the S3 and S4 steps. While for thermally unstable polymers, the viscosity loss is usually due to degradation, it may also arise from structural changes such as melting of residual crystalline domains or flow-induced chain orientation. Competing processes like cross-linking, which counteracts chain scission, should also be accounted for. However, for neat polymers processed well above their melting temperatures, these factors are expected to have a minimal impact on .

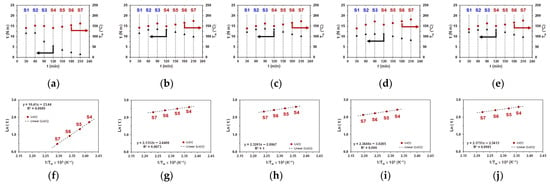

We further investigated the melt behavior of a neat PBST polymer and its mixtures with Bruggolen® H175, a thermal stabilizer (TS) containing phenolic antioxidants and co-stabilizers. In Figure 4, the terminal values of and for neat PBST and its mixtures with TS, and the corresponding Arrhenius plots for the S4–S7 steps, are shown. The corresponding plots of , , , and over time are given in Supporting Information, Figure S1. Processing of neat PBST causes a significant torque drop already in step S3, which is more pronounced than in PBS(1) and PBSA. In addition, the PBST melt exhibits a stronger temperature dependence, manifested by a steeper slope in the Arrhenius plot (see fit data in Figure 3c,d and Figure 4f). Adding TS, however, alters the melt behavior of PBST dramatically. The drop in occurs across the S4–S7 steps due to a rise in temperature, whereas across steps S1–S3, increases due to an increased shear rate. For all PBST/TS mixtures, the evolution of and is comparable and resembles PBS(1) behavior. Similar changes in melt behavior were also be observed upon processing of PBSA, PBAT1, and their mixtures with TS mixtures (see Figures S2–S5 in Supporting Information).

Figure 4.

(a–e) Plots of terminal values of (red dots) and (black triangles) across S1–S7 processing steps and (f–j) Arrhenius plots of versus across S4–S7 processing steps for (a,f) neat PBST; (b,g) mixture of PBST + 0.1 phr TS; (c,h) mixture of PBST + 0.2 phr TS; (d,i) mixture PBST + 0.3 phr TS; and (e,j) mixture PBST + 0.4 phr TS.

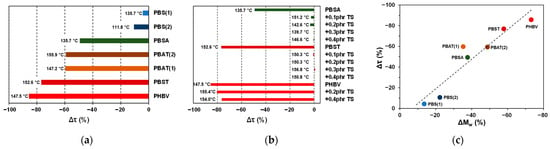

The comparison of the results from the multi-step torque experiments performed on different types of bioPESs and their mixtures with TS is summarized in Figure 5 and in Table 4. Corresponding plots of , , , and over time, as well as plots of and terminal values across the S1–S7 steps and Arrhenius plots across S4–S7 steps are given in Supporting Information, Figures S6–S9. Figure 5a presents values determined for different BioPESs and the corresponding reference temperatures. The least values were obtained for aliphatic PBS and PBSA, followed by PBAT and PBST, the aliphatic-aromatic polyesters. The list closes with PHBV, a bioPES form of the group of polyhydroxyalcanoates (PHAs), which revealed the most significant drop in . Considering that some PHAs are known for their limited thermal stability, the highest drop in viscosity is indeed expectable. Notably, the determined for PBS(2) was higher than for PBS(1), despite the temperature range for processing of this polymer being reduced as compared to other polymers. Another interesting observation is that processing of PBAT(1) and PBAT(2) samples resulted in nearly the same , though the reference temperatures differed from each other.

Figure 5.

(a,b) values determined for (a) different bioPES products and (b) mixtures of PBSA, PBST, and PHBV with different fractions of TS; (c) plot of versus for different bioPES products. The temperature values indicated in plots (a,b) are reference temperatures ().

Table 4.

Experimental conditions, measured and calculated parameters obtained from multi-step torque experiments on neat polymers and their mixture with TS.

In Figure 5b, a plot of obtained for mixtures of PBSA, PBST, and PBHV comprising different fractions of TS is shown. In the case of PBSA and PBST, an addition of 0.1 phr TS resulted in an abrupt change in as compared to neat polymers. A further increase in the TS fraction brought close to zero, indicating that no or very small changes in melt viscosity occur while processing these mixtures. In the case of PHBV, however, the presence of TS had a comparably small effect.

To correlate the changes in measured torque values with changes in molar mass, neat polymers were analyzed by SEC before and after being subjected to the multi-step torque tests. The SEC results are summarized in Table 5. While all neat polymers before processing displayed high molar mass distributions due to the presence of low molar mass components, only data were used for correlative analysis. The plot of versus (Figure 5c) shows the clear correlation between these parameters. This indicates that changes in melt viscosity during processing in the batch mixer are primarily governed by polymer degradation. The measured torque response can be used as an indirect indicator of polymer chain shortening under the applied conditions. More systematic studies are required to quantify the dependencies between and . Such studies are currently in progress.

Table 5.

SEC results for neat bioPES before and after processing using multi-step torque test.

4. Discussion

A multi-step torque rheometry testing method has been introduced, which can be used to analyze the thermal stability of thermoplastic polymers and evaluate the effectiveness of thermal stabilizers. The proposed method relies on directly comparing torque values acquired at the end of specific processing steps conducted under identical conditions. The derived parameter, which represents relative changes in torque and apparent melt viscosity during processing in a batch-type internal mixer, correlates well with relative changes in Mw, which makes it suitable for the semi-quantitative description of shear- and temperature-induced changes in a polymer melt.

The torque and, hence, the apparent viscosity both depend on the temperature and molar mass, and variations in torque during the terminal stage of processing could be attributed to the combined effect of melt temperature and molar mass changes. While the proposed approach accounts for at different reference temperatures, the concept may be further unified to a single reference temperature applied for different samples to be analyzed. In this case, however, every tested sample would require additional torque experiments to be carried out at a constant and varied , but maintaining a setting in which no degradation takes place (S1 or S2). This will allow us to define a primary (initial) temperature before the sample starts to degrade and the selection of a single reference temperature for the sample series, if required. In practical applications, however, such unification of the reference temperature is not required. Instead, it is more important to compare different samples processed under the same conditions. Another point of interest is to compare the same sample processed under different temperature settings, as an increase in temperature may have opposite effects on material stability and thermal degradation.

The number of processing steps and step duration may vary, but they should be kept similar for the same set of samples to be tested and compared. The same is valid for and ranges selected for testing the sample series. The recorded torque values should be within a range that allows us to detect the differences induced by polymer degradation during subsequent processing cycles. On the other hand, too high of a shear stress (torque) may cause significant degradation in the early stage of an experiment. Therefore, the thermal characteristics of tested materials acquired in advance and preliminary tests for selecting the proper processing conditions are beneficial.

Several types of thermoplastic bio-polyesters (bioPES) and their mixtures with Bruggolen® H175 as a thermal stabilizer were studied and compared. Based on , the materials can be ranked as follows: PBS(1) < PBS(2) < PBSA < PBAT(2) ≈ PBAT(1) < PBST < PHBV. The presence of TS alters the melt behavior of the polymers and drastically influences the values as compared to neat polymers. However, in the case of PHBV, the presence of TS had only a minor stabilizing effect. The observed stability ranking and TS effect reflect the interplay between the polymer structure, chain mobility, and dominant degradation pathways. The results are consistent with expectations and can be interpreted in terms of thermo-oxidative degradation and stabilization mechanisms.

The thermo-oxidative degradation of aliphatic and aliphatic–aromatic polyesters during melt processing is primarily driven by radical-mediated ester cleavage, hydroperoxide formation, and β-scission reactions. Under combined thermal and shear stress, macroradicals are initially formed and rapidly converted into peroxy-radicals. The latter abstract hydrogen atoms from neighboring chains, generating hydroperoxides and propagating the degradation cycle. Hydroperoxides then decompose into highly reactive alkoxy radicals, which induce rapid chain scission [19,20,21].

Amorphous PHBV exhibits the lowest thermal stability among all tested materials. Due to its amorphous nature, PHBV melts at comparatively low temperatures, which dramatically increases the accessibility of ester groups to radical attack and other chemical reactions. The stabilizer Bruggolen® H175 acts through a synergistic combination of sterically hindered phenolic antioxidants, which scavenge peroxy-radicals, and phosphorus-based co-stabilizers, which decompose hydroperoxides into non-radical products. These mechanisms are consistent with the radical-driven degradation pathways occurring during melt processing of bioPESs [19]. In the case of PHBV, however, the dominant degradation mechanism is non-radical random chain scission via a β-elimination reaction and involving a six-membered cyclic transition state [22]. This non-radical degradation pathway explains the poor thermal stabilization of PHBV and other bio-polyesters from the PHA group by conventional thermal stabilizers.

5. Conclusions

A multi-step torque rheometry methodology was developed and applied to evaluate the thermal stability and process-induced degradation of thermoplastic bioPESs from different polymer classes. The approach relies on monitoring changes in melt behavior under controlled thermal and shear conditions that reflect realistic polymer processing conditions. The relative change in temperature-normalized torque, , was identified as a suitable semi-quantitative criterion for assessing polymer thermal stability and the effectiveness of thermal stabilizers. The correlation between and demonstrates that multi-step torque rheometry provides a meaningful assessment of polymer degradation occurring during processing. Overall, the proposed methodology represents a practical and efficient tool for comparing thermal stability across different polymers and formulations under realistic processing conditions. It supports the evaluation of the stabilizer performance and offers guidance for optimizing compound formulations and processing parameters without relying solely on conventional thermal analysis techniques.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16021026/s1, Figure S1: Plots of (a1–e1) , (a2–e2) , (a3–e3) , and (a4–e4) over time for (a1–a4) neat PBST, (b1–b4) mixture of PBST + 0.1 phr TS, (c1–c4) mixture of PBST + 0.2 phr TS, (d1–d4) mixture of PBST + 0.3 phr TS, (e1–e4) mixture of PBST + 0.4 phr TS. Figure S2: Plots of (a1–d1) , (a2–d2) , (a3–d3) , and (a4–d4) over time for (a1–a4) mixture of PBSA + 0.1 phr TS, (b1–b4) mixture of PBSA + 0.2 phr TS, (c1–c4) mixture of PBSA + 0.3 phr TS, and (d1–d4) mixture of PBSA + 0.4 phr TS. Figure S3: (a–d) Plots of terminal values of (red dots) and (black triangles) across S1–S7 processing steps and (e–h) Arrhenius plots of versus across S4–S7 processing steps for (a,e) mixture of PBSA + 0.1 phr TS, (b,f) mixture of PBSA + 0.2 phr TS, (c,g) mixture of PBSA + 0.3 phr TS, and (d,h) mixture of PBSA + 0.4 phr TS. Figure S4: Plots of (a1–b1) , (a2–b2) , (a3–b3) , and (a4–b4) over time for (a1–a4) neat PBAT(1) and (b1–b4) mixture of PBAT(1) + 0.2 phr TS. Figure S5: (a,c) Plots of terminal values of (red dots) and (black triangles) across S1–S7 processing steps and (b,d) Arrhenius plots of versus across S4–S7 processing steps for (a,b) neat PBAT(1) and (c,d) mixture of PBAT(1) + 0.2 phr TS. Figure S6: Plots of (a1–b1) , (a2–b2) , (a3–b3) , and (a4–b4) over time for (a1–a4) neat PBAT(2) and (b1–b4) neat PBS(2). Figure S7: (a,c) Plots of terminal values of (red dots) and (black triangles) across S1–S7 processing steps and (b,d) Arrhenius plots of versus across S4–S7 processing steps for (a,b) neat PBAT(2) and (c,d) neat PBS(2). Figure S8: Plots of (a1–c1) , (a2–c2) , (a3–c3) , and (a4–c4) over time for (a4–a4) neat PHBV, (b1–b4) mixture of PHBV + 0.2 phr TS, and (a4–c4) mixture of PHBV + 0.4 phr TS. Figure S9: (a,c,e) Plots of terminal values of (red dots) and (black triangles) across S1–S7 processing steps and (b,d,f) Arrhenius plots of versus across S4–S7 processing steps for (a,b) neat PHBV, (c,d) mixture of PHBV + 0.2 phr TS, and (e,f) mixture of PHBV + 0.4 phr TS.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H. and K.T.; methodology, A.H. and M.G.; validation, A.H. and A.L.; formal analysis, A.H. and M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H.; writing—review and editing, M.G., K.T., A.L. and M.M.; project administration, K.T. and M.M.; funding acquisition, K.T. and M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK) following a resolution of the German Bundestag, grant number KK5332107PA3, and by the Saxon State Ministry for Energy, Climate Protection, Environment and Agriculture (SME-KUL) under the funding guideline “Energy and Climate—FRL EuK/2023”. Administration of this funding was carried out by the Saxon Development Bank (SAB), project number 100707474.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be addressed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Quinn A. Besford (IPF Dresden e.V.) for the helpful discussion during the manuscript preparation. We also acknowledge Lars Fischer (FILK Freiberg Institute gGmbH) for his input into the multi-step torque experiments and Franziska Franke (IPF Dresden e.V.) for the SEC measurements. K.T and A.H. acknowledge BMWK for funding ZIM-Project “B-Tarp” and the project partners Heytex Bramsche GmbH and Linotech GmbH for their outstanding cooperation. M.G. acknowledges SME-KUL for the funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| bioPES | Bio-polyester |

| PBS | Poly(butylene succinate) |

| PBSA | Poly(butylene succinate-co-adipate) |

| PBAT | Poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) |

| PBST | Poly(butylene succinate-co-terephthalate) |

| PHBV | Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) |

| TS | Thermal stabilizer |

References

- Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Yu, C.; Wu, B.; Wang, Y.; Li, W. A Novel Method for the Determination of Steady-State Torque of Polymer Melts by HAAKE MiniLab. Polym. Test. 2014, 33, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, E.; Bianchi, O.; Monteiro, E.E.C.; Reis Nunes, R.C.; Forte, M.C. Processability of PVDF/PMMA Blends Studied by Torque Rheometry. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2009, 29, 657–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa Filho, V.A.; De Albuquerque Filho, M.A.; De Alencar Lira, M.C.; Pedrosa, T.C.; Da Fonseca, L.S.; Araújo, S.S.; Henrique, M.A.; Da Silva Barbosa Ferreira, E.; Araújo, E.M.; Luna, C.B.B. Efficiency Assessment of the SEBS, SEP, and SBS Copolymers in the Compatibilization of the PS/ABS Blend. J. Polym. Res. 2023, 30, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, C.; Bouquey, M.; Schlatter, G.; Muller, R. Rheological Behavior of Reactive Miscible Polymer Blends: Influence of Mixing and Annealing before Crosslinking. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2005, 98, 1978–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, T.G.; Neto, J.E.S.; Costa, A.R.M.; Da Silva, A.S.; Carvalho, L.H.; Canedo, E.L. Degradation during Processing in Poly(Butylene Adipate-Co-Terephthalate)/Vegetable Fiber Compounds Estimated by Torque Rheometry. Polym. Test. 2016, 55, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.A.B.S.; Marinho, V.A.D.; Falcão, G.A.M.; Canedo, E.L.; Bardi, M.A.G.; Carvalho, L.H. Rheological, Mechanical and Morphological Properties of Poly(Butylene Adipate-Co-Terephthalate)/Thermoplastic Starch Blends and Its Biocomposite with Babassu Mesocarp. Polym. Test. 2018, 70, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reul, L.T.A.; Pereira, C.A.B.; Sousa, F.M.; Santos, R.M.; Carvalho, L.H.; Canedo, E.L. Polycaprolactone/Babassu Compounds: Rheological, Thermal, and Morphological Characteristics. Polym. Compos. 2019, 40, E540–E549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.-Z.; Zhu, B.; Pan, M.-S.; Feng, J.-Q. Melt Shear Flow Behavior of Flame-Retardant Polypropylene Composites Filled with Microencapsulated Red Phosphorus. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2019, 32, 1361–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, D.S.C.; Canedo, E.L.; Carvalho, L.H.D.; Barbosa, R.; Alves, T.S. Characterization of Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate) by Torque Rheometry. Mat. Res. 2021, 24, e20200238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekker, M.; Robertson, D.; Duveskog, H.; Van Reenen, A.J. Performance Mapping toward Optimal Addition Levels and Processing Conditions for Different Types of Hydrocarbon Waxes Typically Used as External Lubricants in Sn-Stabilized PVC Pipe Formulations. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 22199–22209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerkar, M. In-depth Rheological Study of Acrylic Processing Aids in Rigid Polyvinyl Chloride Applications. J. Vinyl Addit. Technol. 2023, 29, 662–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Marec, P.E.; Ferry, L.; Quantin, J.-C.; Bénézet, J.-C.; Bonfils, F.; Guilbert, S.; Bergeret, A. Influence of Melt Processing Conditions on Poly(Lactic Acid) Degradation: Molar Mass Distribution and Crystallization. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2014, 110, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceretti, D.V.A.; Edeleva, M.; Cardon, L.; D’hooge, D.R. Molecular Pathways for Polymer Degradation during Conventional Processing, Additive Manufacturing, and Mechanical Recycling. Molecules 2023, 28, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalonde, J.N.; Pilania, G.; Marrone, B.L. Materials Designed to Degrade: Structure, Properties, Processing, and Performance Relationships in Polyhydroxyalkanoate Biopolymers. Polym. Chem. 2025, 16, 235–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, T.S.; Carvalho, L.H.; Canedo, E.L. Engineering Modeling of Laboratory Internal Mixer. In Proceedings of the 72th Annual Technical Conference of the Society of Plastics Engineers (ANTEC 2014), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 28–30 April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, T.S.; Silva Neto, J.E.; Silva, S.M.L.; Carvalho, L.H.; Canedo, E.L. Process Simulation of Laboratory Internal Mixers. Polym. Test. 2016, 50, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.R.M.; Almeida, T.G.; Silva, S.M.L.; Carvalho, L.H.; Canedo, E.L. Chain Extension in Poly(Butylene-Adipate-Terephthalate). Inline Testing in a Laboratory Internal Mixer. Polym. Test. 2015, 42, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinho, V.A.D.; Cesario, L.V.; Costa, A.R.M.; Carvalho, L.H.; Almeida, T.G.; Canedo, E.L. Heat Transfer Coefficient in Internal Mixers for Different Polymers and Processing Conditions. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2019, 152, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Stache, E.E. Recent advances in oxidative degradation of plastics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 7309–7327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velghe, I.; Buffel, B.; Vandeginste, V.; Thielemans, W.; Desplentere, F. Review on the Degradation of Poly(lactic acid) during Melt Processing. Polymers 2023, 15, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chen, F.; Chen, H.; Liu, H.; Chen, L.; Yu, L. Thermal degradation and combustion properties of most popular synthetic biodegradable polymers. Waste Manag. Res. 2022, 41, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H.; Wen, X.; Miu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhu, M. Thermal Depolymerization Mechanisms of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate). Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2016, 26, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.