Abstract

Ptelea trifoliata L. is a perennial plant of the Rutaceae family and contains secondary metabolites with potential biological relevance. Due to limited information on its activity, the objective of this study was to evaluate the biological properties of its flower extracts and to determine their phytochemical composition. Flowers were dried and subjected to ultrasound-assisted extraction using methanol, 60% methanol and water. LC–MS/MS was used for qualitative profiling, HPLC for quantitative determination, and spectrophotometry for measuring total phenolic and flavonoid content. The antioxidative capacity of the extracts was determined using DPPH, CUPRAC, FRAP, and iron chelation assays. Enzymatic inhibition analyses were performed for hyaluronidase, indicative of anti-inflammatory properties, and tyrosinase, associated with pigmentation mechanisms. The wound-healing capacity was evaluated in vitro using a scratch assay. Our research revealed the highest levels of polyphenols in the 60% methanol extract and of flavonoids in the methanol extract. The occurrence of chlorogenic acid, rutin, hyperoside, and astragalin was also demonstrated. Both methanol and 60% methanol extracts demonstrated antioxidant effects. The methanol extract showed the greatest hyaluronidase inhibition, while the 60% methanol extract was the most effective in suppressing tyrosinase activity and promoting wound closure. Principal component analysis showed that the contents of polyphenols or flavonoids were associated with enzyme-inhibitory or antioxidant activities. Moreover, the 60% methanol and water extracts exhibited notable wound healing properties. These results highlight the antioxidant, enzyme-modulating and regenerative potential of P. trifoliata flower extracts, suggesting their possible use in biomedical and dermatological applications.

1. Introduction

Ptelea trifoliata L., commonly known as the hoptree, is a perennial shrub or small tree that belongs to the Rutaceae family. Native to North America, it grows in temperate climates and was introduced to Europe in the 18th century as an ornamental plant. The genus name Ptelea comes from the Greek word for ‘elm’, in reference to the resemblance of its fruits to those of Ulmus species [1].

Ethnobotanical records indicate that P. trifoliata had medicinal significance among Native American tribes. The Meskwaki used root infusions to treat respiratory ailments and to enhance the efficacy of other herbal medicines [2]. Leaf infusions were applied externally to relieve abdominal pain in children, and the plant was also used as an ingredient in arrow poisons [3]. Today, P. trifoliata remains an ingredient in certain homeopathic remedies, ranging in potency from 6 CH to 1000 CH, which are recommended for respiratory and digestive disorders, rheumatism, and headaches [4].

Phytochemical analysis of P. trifoliata has revealed several classes of biologically active substances such as alkaloids, coumarins, essential oils, flavonoids, and polyphenolic compounds [5,6,7]. These metabolites are responsible for various biological effects. For example, alkaloids isolated from P. trifoliata exhibit antibacterial properties [8], and coumarins such as auraptene demonstrate antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, and antineoplastic activities [9]. Arctigenin, another compound identified in the flowers, exhibits antitumour, hepatoprotective, and neuroprotective effects [10]. Hyperoside, a flavonoid glycoside, is recognised for its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, as well as its cardioprotective and antidepressant effects [10].

Despite growing evidence of the pharmacological relevance of P. trifoliata constituents, most studies have focused on the chemical characteristics of the leaves and roots, as well as their biological potential. The phytochemical profile and bioactivity of the flowers remain largely unexplored, even though the floral tissues of species in the Rutaceae family are often rich in volatile and polyphenolic compounds with strong antioxidant potential [11]. Moreover, flowers of numerous plant species are valuable pharmaceutical raw materials. They not only contain essential oils responsible for their primary effects—for example, chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla) contains α-bisabolol, chamazulene, apigenin, and luteolin [12]—but also phenolic compounds that enhance therapeutic outcomes. Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) essential oil—rich in linalool and linalyl acetate—has demonstrated anxiolytic and central nervous system activity [13]. Additionally, black elderflower (Sambucus nigra) has been demonstrated to be a source of flavonoids and phenolic acids, which possess high antioxidant capacity [14], while meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria) provides phenolic acids and flavonoids that contribute to anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects [15]. Given the pharmacological importance of flowers in phytotherapy and the fact that P. trifoliata flowers are still poorly characterized, they represent a promising target for further research, justifying the present study. Considering the presence of metabolites such as skimmianine, auraptene, arctigenin, and hyperoside in P. trifoliata flowers, it can be hypothesised that their extracts may exhibit significant antioxidant and enzyme-modulating activity and have the potential to enhance wound-healing processes.

The quest for novel plant-derived substances with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and regenerative properties remains a key objective in modern pharmacognosy and cosmetic science. Extracts capable of modulating key skin-related enzymes, such as hyaluronidase and tyrosinase, are particularly valuable due to their anti-inflammatory and anti-ageing effects. Their antioxidant properties may also support wound healing by reducing oxidative stress.

Given the limited knowledge surrounding the composition and bioactivity of P. trifoliata flowers, this study aimed to investigate their antioxidant properties, enzyme inhibition potential and in vitro wound-healing effects, alongside a comprehensive phytochemical characterisation of the extracts. These findings could provide valuable insights into the pharmacological potential of P. trifoliata and support its future use in developing natural biomedical and dermal formulations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical Reagents

Acetonitrile (J.T. Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ, USA); acetate buffer (J.T. Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ, USA); aluminum chloride (POCH, Gliwice, Poland); astragalin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); azelaic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); β-escin (Carl Roth GmbH + Co. KG, Karlsruhe, Germany); Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); chlorogenic acid (Dr. Ehrenstorfer GmbH, Augsburg, Germany); CTAB (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); copper(II) chloride (POCH, Gliwice, Poland); DPPH (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); distilled water (Direct-Q® 3UV water purification system, Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany); Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (Fisher Scientific U.K. Limited, Loughborough, UK); formic acid (POCH, Gliwice, Poland); gallic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); hyperoside (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); hyaluronic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); hyaluronidase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); iron(III) chloride (POCH, Gliwice, Poland); L-DOPA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); methanol (POCH, Gliwice, Poland); neocuproine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); phosphate buffer concentrate 20×, pH = 6.8 (STAMAR, Dąbrowa Górnicza, Poland); quercetin (Carl Roth GmbH + Co. KG, Karlsruhe, Germany); rutin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); sodium acetate trihydrate (POCH, Gliwice, Poland); sodium chloride (POCH, Gliwice, Poland); sodium carbonate (POCH, Gliwice, Poland); sodium hydroxide (POCH, Gliwice, Poland); TPTZ (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); Trolox (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); tyrosinase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Plant Material

The plant material that was analysed was dried flowers of P. trifoliata that had been collected from the Botanical Garden of Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan (collection date: 7 June 2023). The samples were reposited at the Department and Chair of Pharmacognosy and labelled with the code: PT_F_06.2023.

2.3. Extraction Process

10.0 g of dried P. trifoliata flowers, separated from their pedicels, was weighed and placed into three Erlenmeyer flasks. The material was extracted six times for 20 min each at 60 °C using ultrasound with solvents of methanol, 60% methanol, and H2O, respectively (150 mL of each solvent per extraction). Ultrasound-assisted extraction was performed using an ultrasound generator operating at 120 W of power and a frequency of 40 kHz. The temperature was digitally controlled with a precision of ±1.0 °C. The resulting extracts were subsequently subjected to filtration, and the residue was centrifuged. The clear supernatant was then concentrated, frozen and subsequently lyophilized to obtain dry extracts. The extracts, labelled MeOH, 60% MeOH, and H2O, were stored in a dark, dry place and subjected to subsequent tests.

2.4. Chemical Characterisation of the Extracts

2.4.1. Total Polyphenol Content

The total phenolic content was evaluated by employing a modified version of a previously described Folin–Ciocalteu assay [16]. In each well, 25.0 µL of the extract (2.5 mg/mL in DMSO) or gallic acid standard solutions (0.16–0.01 mg/mL) was added. The subsequent step involves adding 200.0 µL of distilled water, 15.0 µL of the Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, and 60.0 µL of a 20% calcium carbonate solution. A control mixture, containing all reagents except the test sample or standard, was prepared simultaneously. The plate was then incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min with gentle shaking at 350 rpm. Subsequently, absorbance was recorded at 760 nm using a Multiskan GO 1510 microplate spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Each experiment was conducted in duplicate. The results are presented as the mean of four measurements (n = 4) and expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per gram of dry plant material, along with the standard deviation (SD).

2.4.2. Total Flavonoid Content

The flavonoid content was quantified using a modified version of a previously reported colorimetric assay [16]. For each determination, 100.0 µL of the extract (5.0 mg/mL in DMSO) or quercetin standard solution (0.1–0.00312 mg/mL) was combined with 100.0 µL of a 2% aluminium chloride solution prepared in methanol. The microplate was briefly shaken for one minute and subsequently incubated in the dark at room temperature for 10 min. Absorbance was then recorded at 415 nm using the previously mentioned microplate spectrophotometer. The blank sample was a mixture of the examined sample and methanol, replacing the AlCl3 reagent. Each assay was performed in duplicate. The data represent the mean values of four measurements (n = 4). The outcomes are presented as milligrams of quercetin equivalents (QE) per gram of dry plant material, along with the standard deviation (SD).

2.4.3. Quantitative Analysis of the Extract Using LC–MS/MS

The analysis of the samples was conducted via liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS), a method employed for the qualitative identification of predominant polyphenolic compounds. The analysis was performed on an Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC) system (Shimadzu Co., Kyoto, Japan), equipped with a binary pump (LC-20AD), a thermostated autosampler (SIL-30AC), a solvent degasser (DGU-20A5), and a column compartment (CTO-20AC). The UPLC system was integrated with a triple quadrupole detector LCMS-8030. The analysis was performed using the LabSolutions Series Workstation system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid and acetonitrile in a gradient flow (acetonitrile content: 0–35 min, 2–20%; 35–55 min, 20–70%; 55 min, 2%; 55–60 min, 2%). The experimental parameters stipulated a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min, and the chromatographic separation temperature was adjusted to 40 °C. A LiChrosphere RP-18 (4.0 mm × 250 mm, 5 μm, Merck, Germany), with a LiChrosphere RP-18 guard column (5 μm, 250 mm × 4 mm, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), was used for the identification of polyphenolic compounds. The positive electrospray ionization mode (ESI+) was applied to rutin, astragalin, and chlorogenic acid, while negative electrospray ionization mode (ESI−) was employed for hyperoside. The injection volume was 10 μL. The desolvation line and the heat block were both set to temperatures of 240 °C and 400 °C, respectively. Nitrogen was utilised as the drying and nebulising gas (10 and 2 L/min, respectively); argon was used as the collision gas. The electrospray needle voltage was set at 4.5 kV. The most sensitive mass transition was identified by means of multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode, and these were observed at m/z 449.1 > 287.0 and 449.1 > 85.05 for astragalin; 611.2 > 303.0 and 611.2 > 465.0 for rutin; 355.1 > 162.95 and 355.1 > 134.8 for chlorogenic acid; and 463.15 > 300.05 and 463.15 > 270.95 for hyperoside. LC-MS/MS parameters for qualitative identification of the studied compounds are presented in Table S1 (Supplementary Materials).

2.4.4. Quantitative Analysis of the Extract Using HPLC

Using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), the presence and content of chlorogenic acid, rutin, and hyperoside were determined in flower extracts from P. trifoliata. The analysis was performed according to the method described by Paczkowska-Walendowska et al. [17], and the procedure was validated to ensure the reliability of the results. The validation included assessment of linearity, direct and indirect precision, limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ), ensuring that no modifications to the original chromatographic procedure were required. The chromatographic conditions included a detection wavelength of 325 nm for chlorogenic acid and 360 nm for rutin and hyperoside; a mobile phase flow rate of 1 mL/min; a column temperature of 40 °C; and a mobile phase consisting of 0.1% formic acid (solvent A) and acetonitrile (solvent B). The gradient elution programme was as follows: The initial phase of the reaction (0–35 min) was characterised by a low concentration of B, ranging from 2% to 20%. This was followed by a period of elevated B concentration, spanning from 35 to 55 min, with a range of 20% to 70%. The final phase, from 55 to 60 min, exhibited a low B concentration of 2%. Standard solutions were prepared in HPLC-grade methanol encompassing concentrations of chlorogenic acid, rutin, and hyperoside. The concentrations of these compounds were determined to be 1.0 and 0.1 mg/mL for chlorogenic acid, 0.5 mg/mL for rutin, and 0.05 mg/mL for hyperoside. All solutions were filtered through a 0.45 µm membrane filter prior to injection. For each compound and concentration, a series of injection volumes was applied to construct calibration curves. The injection volumes are specified below: for chlorogenic acid—12, 10, 8, 6, 4, 2, 1 µL (0.1 mg/mL), and 8, 6, 4 µL (0.01 mg/mL); for rutin—80, 60, 40, 20, 10, 5 µL (0.5 mg/mL); for hyperoside—10, 8, 6, 4, 2, 1 µL (0.05 mg/mL). Calibration curves were established. Next, after filtering the prepared extracts of P. trifoliata through a membrane filter (0.45 µm), they were injected onto the column at a concentration of 3 mg/mL (the aqueous and methanol-aqueous extracts were dissolved in water, and the methanol extract in a mixture of 20% DMSO and 80% water). The sample was assayed three times.

2.5. Studies of Biological Activity of Extracts

2.5.1. Antioxidant Activity Assay

- DPPH assay

The antioxidant capacity of the samples was evaluated using the DPPH radical reduction assay, adapted from previously published procedures [18]. In this approach, 25.0 µL of the tested extracts (20–1.25 mg/mL) or trolox as a reference (0.2–0.00625 mg/mL) was added to 175.0 µL of DPPH solution (0.2 mM in methanol). The mixture was gently agitated at 500 rpm for 30-min incubation in the dark. Absorbance readings were collected at 517 nm using the previously mentioned microplate spectrophotometer. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate, and the obtained results are an average of five independent measurements (n = 5). The results were expressed as IC50 (mg/mL) ± SD. IC50 values were calculated using non-linear curve fitting based on the relationship between activity and compound concentration, except for the standard, for which linear regression was used. At least five different concentrations were tested.

- CUPRAC assay

The CUPRAC assay was performed according to a modified version of an established protocol [16]. The CUPRAC mixture was obtained by combining equal volumes of 7.5 mM neocuproine, 10 mM copper(II) chloride, and 1 M ammonium acetate buffer adjusted to pH 7.0. Subsequently, 50 µL of the extracts (2.5–0.15625 mg/mL) or trolox standard as a reference (0.2–0.00625 mg/mL) was mixed with 150 µL of the prepared reagent. The reaction mixtures were gently agitated at 500 rpm and kept in the dark at room temperature for 30 min to allow complex formation. Absorbance was then recorded at 450 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer. A blank sample containing the extraction solvent in place of the extract was used for background correction. Each analysis was performed in duplicate, and the results represent the mean of five independent measurements (n = 5). The results were expressed as IC0.5, defined as the concentration of the tested extract or standard at which the absorbance equals 0.5 (mg/mL) ± SD. IC0.5 values were calculated using a linear equation describing the relationship between activity (absorbance) and compound concentration. At least five different concentrations were tested to ensure reliable results.

- FRAP assay

The ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay was conducted based on the procedure described by Tiveron et al. [19], with slight adjustments. The stock FRAP solutions included: 300 mM acetate buffer (pH 3.6), a 10 mM solution of TPTZ prepared in 40 mM HCl, and a 20 mM ferric chloride (FeCl3·6H2O) solution. Immediately before analysis, the FRAP working reagent was obtained by combining 25 mL of acetate buffer with 2.5 mL of the TPTZ solution and 2.5 mL of the FeCl3·6H2O solution, after which the mixture was preheated to 37 °C. For each measurement, 20 µL of the extract (2.5–0.078125 mg/mL) or the trolox standard (0.2–0.00625 mg/mL) was added to 180 µL of the working reagent and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min in the absence of light. A blank was prepared using the FRAP reagent lacking the TPTZ component. Absorbance values were recorded at 593 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer. Each analysis was performed in duplicate. All measurements were carried out in five replicates (n = 5). The outcomes of this investigation were expressed in terms of IC0.5, a concentration defined as the level at which the sample’s optical density (OD) was equivalent to 0.5 ± SD (mg/mL). IC0.5 values were calculated using a linear equation describing the relationship between activity (absorbance) and compound concentration. At least six different concentrations were tested to ensure reliable results.

- Chelation Power on Ferrous (Fe2+) Ions assay

The ability of the extracts to chelate ferrous ions was determined using a modified version of the procedure described by Dinis et al. [20], with slight modifications. For this assay, 200.0 µL of each extract (corresponding to 2.5 mg of dry plant material per mL) was combined with 10.0 µL of FeCl2·4H2O solution (1 mM) in a 96-well microplate. The mixture was shaken at 500 rpm and allowed to equilibrate for 10 min at room temperature. Afterwards, 40.0 µL of a 2.5 mM ferrozine solution was added, and the samples were incubated for an additional 30 min under the same conditions to allow the Fe2+–ferrozine complex to form. The absorbance was subsequently recorded at 562 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer. The results were expressed as IC50 (mg/mL) ± SD. IC50 values were calculated using non-linear curve fitting based on the relationship between activity and compound concentration, except for the standard, for which linear regression was used. At least four different concentrations were tested to ensure reliable results.

2.5.2. Inhibition of Inflammation- and Pigmentation-Related Enzymes

- Anti-Hyaluronidase activity assay

The inhibition of hyaluronidase was assessed using a modified version of an established procedure [21]. 25.0 µL of incubation buffer was combined with 25.0 µL of hyaluronidase solution (30 U/mL), 10.0 µL of the extract (50–10 mg/mL) or the reference compound β-escin (9–5 mg/mL), and 15.0 µL of acetate buffer. The reaction mixture was gently agitated at 500 rpm and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. Subsequently, 25.0 µL of hyaluronic acid (HA) solution was added, followed by an additional 45-min incubation under identical conditions. Afterwards, CTAB solution (200.0 µL), prepared using a sodium hydroxide solution (2%), was added, and the samples were left to stand at room temperature for 10 min without agitation. Absorbance was measured at 600 nm using the previously mentioned microplate spectrophotometer. The blank was prepared in accordance with the method previously outlined in the extant literature [22]. Each assay was performed in duplicate, and the results represent the mean of four measurements (n = 4). The results were expressed as % inhibition and IC50 (mg/mL) ± SD. IC50 values were calculated using a linear equation describing the relationship between activity and compound concentration. At least four different concentrations were tested to ensure reliable results.

- Anti-tyrosinase activity assay

The tyrosinase inhibitory assay was conducted employing a modified iteration of the previously described protocol [18]. In each well, 75.0 µL of phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 6.8) was mixed with 50.0 µL of tyrosinase solution (192 U/mL) and 25.0 µL of the tested extract. The concentration ranges were as follows: 50–2.5 mg/mL for the water extract, 40–0.25 mg/mL for the methanolic extract, and 50–0.25 mg/mL for the 60% methanolic extract. Azelaic acid (1.6–0.2 mg/mL) served as the reference inhibitor. The samples were subjected to a gentle shaking process for a duration of 10 min at ambient temperature. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 50.0 µL of 2 mM L-DOPA solution, followed by a 20-min incubation at 25 °C. The control wells contained all reagents with the exception of the extract, which was substituted with the relevant extraction solvent. For blank samples, either phosphate buffer or L-DOPA was substituted as appropriate to match the composition of the reaction and control mixtures. Absorbance was recorded at 475 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer. Each experiment was conducted on two replicates, and the results were represented by the mean of four measurements (n = 4). The results were expressed as % inhibition and IC50 (mg/mL) ± SD. IC50 values were calculated using either a non-linear equation (for MeOH or 60% MeOH extracts) or linear curve fitting (H2O extract and standard), based on the relationship between activity and compound concentration. At least four different concentrations were tested to ensure reliable results.

2.6. Wound Healing (Scratch) Assay

The MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) method was used to assess the viability of human normal skin fibroblasts (HS27 cells) prior to the commencement of the primary experiment. The cells were cultured with P. trifoliata extracts (MeOH, 60% MeOH, and H2O) at 100 µg/mL. The methodology applied was described in detail in a previous publication [23]. Subsequently, the capacity of P. trifoliata extracts (MeOH, 60% MeOH, and H2O) to promote wound healing was examined using the scratch assay on Hs27 cells, employing the methodology previously outlined [23]. The results were recorded after 24 and 36 h of incubation. The results represent the mean of six measurements (n = 6).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Microsoft Excel was used for the statistical calculations (Microsoft Office LTSC 2021 Professional Plus, Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). Data are presented as mean ± SD. Differences between groups were evaluated with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Post-hoc comparisons were performed with Tukey’s test to assess differences between all experimental groups. Statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05. Origin 2021b software (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA) was used for principal component analysis (PCA) to analyse correlations.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Phytochemical Study of Ptelea trifoliata Flowers Extracts

3.1.1. Total Polyphenol (TPC) and Flavonoid (TFC) Content in Ptelea trifoliata Extracts

Polyphenols are a group of plant compounds with strong biological potential, crucial in assessing the antioxidant properties of substances, as confirmed by numerous in vitro and in vivo studies [24]. The anti-free-radical activity of these compounds is important for maintaining overall health, including good skin condition, by inhibiting the effects of photoageing, stimulating collagen synthesis, and inhibiting extracellular matrix-degrading enzymes [24,25]. Furthermore, polyphenols exhibit wound-healing properties, making them attractive ingredients in dermal formulations [26,27]. Due to their multimodal effects (antioxidation, metal chelation, enzyme, and cytokine modulation), the presence of polyphenols in plant extracts provides an important starting point for research on their biological potential and pharmaceutical and cosmetic applications [28,29].

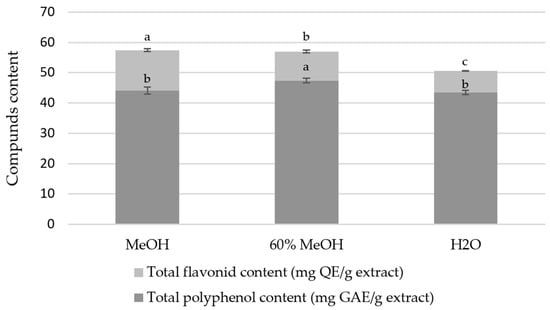

Therefore, in our study, we assessed the total polyphenol content (TPC) of P. trifoliata flower extracts (Figure 1). The results, expressed as mg GAE/g extract, indicated the highest content in the 60% methanolic extract (47.42 mg GAE/g), followed by the methanolic extract (44.09 mg GAE/g), and the lowest in the H2O extract (43.47 mg GAE/g). These findings indicate that methanol-based solvents extract polyphenols more efficiently than water. The total flavonoid content (TFC) (Figure 1) was the highest in the methanolic extract (13.36 mg QE/g), followed by the 60% methanolic (9.56 mg QE/g) and H2O extracts (7.13 mg QE/g). These results confirm that methanol is the most efficient solvent for flavonoid extraction, in agreement with HPLC data showing the highest flavonoid peak intensity in the methanolic extract. Although data on P. trifoliata flowers are lacking, it is evident that the values obtained are aligned with those reported for other polyphenol-rich plants, such as Sambucus nigra (16 mg QE/g) [30] and Passiflora ligularis (5.77 mg QE/g) [31], indicating that P. trifoliata flowers represent a promising source of flavonoids.

Figure 1.

Total polyphenol content and total flavonoid content in the tested Ptelea trifoliata extract samples. MeOH—methanol extract, 60% MeOH—60% methanol extract, H2O—water extract, mg GAE/g DW—mg gallic acid equivalent per gram of dry weight, mg QE/g DW—mg quercetin equivalent per gram of dry weight. Values are presented as mean ± SD. Different letters indicate significant differences between groups (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test).

3.1.2. Phytochemical Analysis of the Extract Using LC–MS/MS and HPLC-DAD Analysis

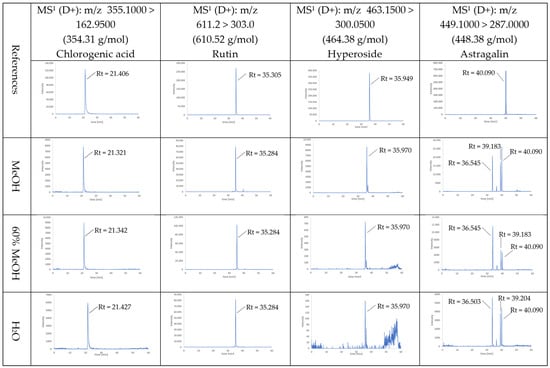

Four main polyphenolic compounds were identified with LC-MS/MS analysis in the methanolic, 60% methanolic, and H2O extracts (Figure 2). The retention times were 21.4 min, 35.3 min, and 36.0 min for chlorogenic acid, rutin, and hyperoside, respectively. The same retention time was observed in the studied extracts for these three compounds. For astragalin, for reference standard the retention time was 40 min, whereas in the extracts analysis the peaks for astragalin were observed at 33.7 min, 36.5 min, 39.2 min, and 40.0 min at the same mass transition (m/z 449.1 > 287.0).

Figure 2.

The LC-MS/MS chromatograms of references and Ptelea trifoliata MeOH, 60% MeOH, and H2O extracts.

To our knowledge, data on the presence of polyphenolic compounds in P. trifoliata are limited, and the presence of rutin, chlorogenic acid, and astragalin in P. trifoliata flowers has not been described previously by other authors. However, the presence of hyperoside in P. trifoliata flowers was noted by Novak [7]. In the literature, flowers of P. trifoliata have been reported to emit volatile “active” constituents dominated by mono- and sesquiterpenes—e.g., linalool, myrcene, (E)-β-ocimene, α-pinene, β-caryophyllene, germacrene D, and bicyclogermacrene—alongside aromatic esters such as ethyl benzoate and methyl salicylate, as well as phenylpropanoids including estragole (anethole) [11,32]. Furthermore, compounds from the alkaloid group and auraptene were also detected in the flowers [5,7].

In the present study, LC–MS/MS MRM) analysis of the astragalin (kaempferol-3-O-glucoside) reference standard produced a single, sharp peak for the monitored transition, whereas MeOH and H2O plant extracts displayed several distinct peaks under the same transition. This pattern is consistent with previous reports indicating that, in complex plant matrices, a target compound may coexist with structural, positional, or configurational isomers and related derivatives that (i) are chromatographically separable and (ii) yield identical or very similar precursor/product ion pairs, resulting in multiple peaks within a single MRM channel. Comparable behavior has been widely documented for chlorogenic acids, where individual isomers (e.g., neochlorogenic acid, cryptochlorogenic acid, and chlorogenic acid) or their lactone derivatives are clearly resolved in extracts, whereas a pure standard of one isomer produces only a single chromatographic signal. The underlying mechanism involves acyl migration, epimerisation, or other transformation processes that occur during extraction or chromatographic separation, leading to the appearance of multiple chromatographic entities sharing the same nominal mass and fragmentation pattern [33,34,35]. Extracted ion chromatograms have been known to contain multiple peaks with similar m/z values but different retention times. This phenomenon has been hypothesised to occur as a consequence of the possible presence of isomers [36].

In LC-MS/MS studies, the pure standard of astragalin (kaempferol-3-O-glucoside) typically produces a single, sharp peak with the characteristic fragmentation [M–H]− 447 → 285, as confirmed by reference databases (MassBank, PhytoHub). In contrast, analyses of plant extracts in the same extracted ion chromatogram (XIC)/MRM channel often reveal multiple peaks corresponding to astragalin and its isomers or derivatives (e.g., other kaempferol-O-hexosides or acylated forms). Such multiphasic chromatographic behavior has been reported in a study on species of the genus Prunus [37]. Astragalin contains chiral centres and may occur in multiple forms, including positional isomers and epimers. To quantify astragalin accurately, it would be necessary to obtain individual reference standards for each compound to identify all of these isomeric forms, which was beyond the scope of the present study but should be addressed in future research. During MS analysis, these compounds generate signals due to their highly similar mass spectra and fragmentation patterns, which creates challenges in distinguishing them. Positional isomers share the same molecular formula and differ only in the location of a functional group on the molecular scaffold, making it difficult to differentiate them based on molecular weight alone. Although positional isomers may produce similar MS/MS spectra, subtle differences in their fragmentation patterns can sometimes allow their discrimination. Since epimers differ only in the configuration at one stereocenter, their molecular formula is identical. As a result, they exhibit the same exact m/z for the precursor ion and typically produce the same fragment ions with very similar relative intensities, leading to almost indistinguishable MRM transitions. Even if epimers show slightly different MS/MS spectra, the differences are usually not big enough to allow clean quantification in complex matrices without chromatographic resolution.

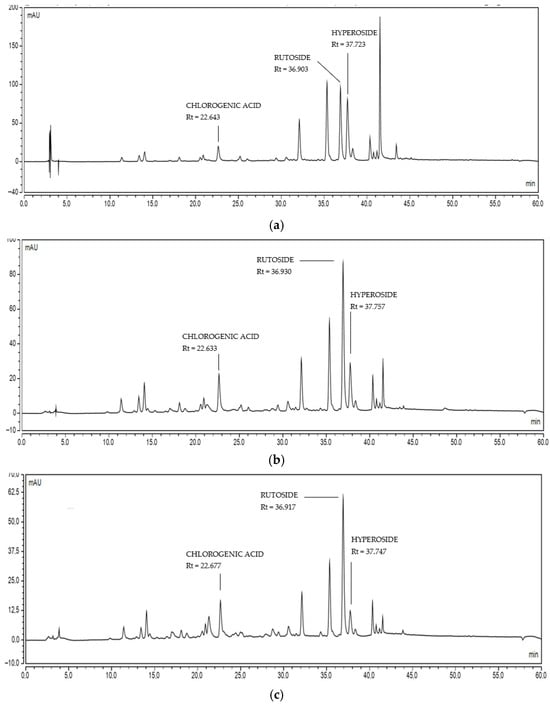

P. trifoliata extracts were also subjected to quantitative analysis using the HPLC-DAD method. The application of this methodology enabled the calculation of the content of chlorogenic acid, rutin, and hyperoside in the extract. In contrast, reliable quantification of astragalin was not possible. The LC-MS/MS analysis revealed multiple peaks in the MRM channel, suggesting the presence of isomers or structurally related glycosides, which made accurate quantification impossible within this analytical setup. It should be noted that the difficulty in quantifying astragalin is consistent with previous reports showing that structurally similar flavonoid glycosides often co-elute or exhibit overlapping UV spectra, thereby hindering accurate detection using standard HPLC-DAD methods [38,39]. Reliable quantification would require additional methodological refinement, including the purification of astragalin, the use of isomer-specific analytical standards, or the implementation of modified chromatographic conditions—such as alternative stationary phases or MS-based detection—which are commonly recommended for closely related flavonoid isomers [40,41]. These approaches were beyond the scope of the present work and are therefore acknowledged as a limitation. The results obtained suggest that the extracts were similar in their qualitative composition (Figure 3) but differed quantitatively. The MeOH extract contained the highest concentration of flavonoids, including rutin (8.61 mg/g of dry extract), followed by the 60% MeOH extract (7.72 mg/g of dry extract) and the H2O extract (5.11 mg/g of dry extract), which had the lowest concentration (Table 1). The highest amounts of hyperoside were also determined in the MeOH extract. In contrast, chlorogenic acid, which is a representative of phenolic acids, dominated in the 60% MeOH extract, although the differences between the MeOH extracts were small. The dominant compound in P. trifoliata flowers was rutin, a metabolite common in many plants and characteristic of the Rutaceae family, to which P. trifoliata belongs. High rutin content (>1.5%) has been reported in Ruta graveolens (Rutaceae) (40.15 mg/g of extract) and Sophora japonica (Fabaceae), among others [42,43]. There is very limited research on the phytochemical characterisation of P. trifoliata, emphasising the need for further phytochemical studies of this raw material and other parts of the plant.

Figure 3.

The HPLC chromatograms of Ptelea trifoliata extracts: (a) MeOH extract, (b) 60% MeOH extract, (c) H2O extract. Reference compounds quantified in P. trifoliata extracts showed the following retention times: chlorogenic acid (Rt = 22.693 min), rutin (Rt = 36.880 min), and hyperoside (Rt = 37.787 min).

Table 1.

The content of the selected compounds in the extracts of Ptelea trifoliata flowers determined using HPLC.

3.2. Evaluation of the Biological Potential of Ptelea trifoliata Flower Extracts in Cell-Free Assays

3.2.1. Flower Extracts of Ptelea trifoliata Demonstrate Antioxidant Activity in DPPH, CUPRAC, FRAP, and Fe2+ Chelation Assays

Oxidative stress has been demonstrated as a pivotal factor in the progression of tissue degeneration, chronic inflammation, and impaired wound repair. An excess of these molecules in the skin has been demonstrated to disrupt the balance of oxidants and antioxidants [44]. This, in turn, has been shown to result in a number of adverse effects, including collagen degradation, delayed healing, and premature ageing of cells [45]. Substances with strong antioxidant, reducing, and metal-chelating properties have been shown to protect skin cells from damage and to facilitate their own repair [46]. In this study, the efficacy of plant extracts in combating free radicals was examined. This could be significant for the utilisation of the plant in pharmaceuticals and cosmetics.

The antioxidant potential of P. trifoliata flower extracts was tested using DPPH, CUPRAC, FRAP, and Fe2+ chelation assays (Table 2). The MeOH extract demonstrated the strongest antioxidant activity in the DPPH, CUPRAC, and FRAP assays, compared with the 60% MeOH and H2O extracts. The MeOH had the highest radical-scavenging potential (IC50 value 2.18 mg/mL), whereas the H2O extract exhibited the weakest activity (IC50 = 7.77 mg/mL). The MeOH extract also demonstrated the highest reducing power in the CUPRAC and FRAP assays (IC0.5 = 0.34 and 0.60 mg/mL, respectively), but these values were approximately 6–10 times higher than those of the Trolox standard (IC0.5 = 0.06 mg/mL). The Fe2+ chelating assay revealed a different trend. The 60% MeOH extract showed the strongest iron-cheating activity (IC50 = 0.04 mg/mL), similar to that of the H2O extract (IC50 = 0.05 mg/mL). However, the MeOH extract was much weaker (IC50 = 0.18 mg/mL). All three extracts exhibited greater chelating activity than quercetin (IC50 = 2.06 mg/mL).

Table 2.

Antioxidant activities (DPPH, CUPRAC, FRAP, and Fe2+ chelation) of Ptelea trifoliata flower extracts obtained with different solvents.

In tests examining radical-scavenging capacity and metal ion reduction (Cu2+ and Fe3+), the highest antioxidant potential was demonstrated by the flavonoid-richest extracts. The relationship between flavonoid and polyphenol content and the ability to neutralize free radicals is well documented in the literature [47,48], and the obtained results confirm this correlation. The MeOH and 60% MeOH extracts were particularly rich in rutin, a known flavonoid with antioxidant properties that likely increases the overall redox activity of P. trifoliata extracts [42,49,50,51]. The high antioxidant potential of the extracts may be important for anti-ageing and skin protection [52].

The results of the Fe2+ chelation test confirm that P. trifoliata flower extracts can bind iron ions and limit oxidative damage caused by Fenton-type reactions. This is important for protecting skin cells and reducing oxidative stress and may also support anti-ageing effects by protecting lipids and cellular structures from Fe2+-induced peroxidation. Current research suggests that metal chelation exerts a significant influence on wound healing [53]. The strong chelating activity of the 60% MeOH and aqueous extracts may help explain the enhanced wound closure observed in the scratch assay, described in the following sections. These findings also align with the traditional use of P. trifoliata preparations in promoting wound repair [5].

3.2.2. Extracts from the Flowers of Ptelea trifoliata Show Anti-Hyaluronidase and Anti-Tyrosinase Activity

The activity of enzymes is of pivotal significance to ensure the optimal function of the integumentary system [54]. Tyrosinase and hyaluronidase are particularly important, as they are involved in pigmentation, ageing, and tissue regeneration processes [55]. Hyperactivity of these enzymes has been linked to hyperpigmentation, extracellular matrix degradation, and increased skin inflammation [56]. In particular, excessive hyaluronidase activity accelerates the degradation of hyaluronic acid, contributing to tissue irritation, oedema, and inflammatory responses; therefore, hyaluronidase inhibition is considered to exert anti-inflammatory and anti-oedematous effects [57,58]. Natural inhibitors of these enzymes are therefore a valuable resource in dermatology and cosmetology. To further our understanding of the biological activity of P. trifoliata and to evaluate the cosmetic potential of its flowers, we tested the ability of the obtained extracts to inhibit enzymes that are crucial for skin health.

Our results showed that all of the P. trifoliata flower extracts inhibited the activity of the tested enzymes, but to varying degrees (Table 3 and Table 4). The MeOH and 60% MeOH extracts were the most effective at inhibiting hyaluronidase (IC50 = 26.81 mg/mL and 35.48 mg/mL, respectively). The H2O extract was less active, and at the highest concentration (50 mg/mL) it inhibited the enzyme by 18.39%. By comparison, escin (reference) showed an IC50 of 7.41 mg/mL, indicating that the extracts have weak to moderate enzyme inhibition properties. In contrast, the 60% MeOH extract was the strongest at limiting tyrosinase activity (IC50 = 10.24 mg/mL), followed by the MeOH extract (IC50 = 14.22 mg/mL) and the H2O extract (IC50 = 37.93 mg/mL). Azelaic acid, which is commonly used as a standard, reduced tyrosinase activity by 50% at a concentration of 0.91 mg/mL—approximately ten times more effective than the most active extract. These analyses provide new knowledge on the biological activity of P. trifoliata by describing the effect of its flower extracts on enzymes relevant to anti-ageing effects on skin.

Table 3.

Anti-hyaluronidase activity (IC50) of Ptelea trifoliata flower extracts and escin as the reference.

Table 4.

Anti-tyrosinase activity (IC50) of Ptelea trifoliata flower extracts and azelaic acid as the reference.

The results on tyrosinase and hyaluronidase inhibition by P. trifoliata flower extracts suggest that this species may be a source of bioactive compounds with potential dermatological applications, although the results obtained indicate moderate activity compared to reference substances. This is, however, consistent with literature reports indicating that plant extracts rich in polyphenols tend to modulate rather than completely inhibit enzyme activity [56,59]. The greater inhibitory effects observed for the MeOH and 60% MeOH extracts suggest that these effects may be primarily associated with the presence of polyphenolic compounds, including flavonoids [60]. For hyaluronidase, it has been shown that flavonoid glycosides are less effective inhibitors than their aglycones [61], which may explain the moderate inhibition observed in the analysed extracts, in which three glycosidic compounds were confirmed. Regarding tyrosinase, its inhibition by rutin has been previously reported [62], and since rutin was determined to be one of the predominant flavonoids present in P. trifoliata flowers, the stronger inhibition of tyrosinase compared with hyaluronidase may be attributed to its presence.

3.2.3. Principal Component Analysis Reveals Relationships Between Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant as Well as Enzymatic Activities

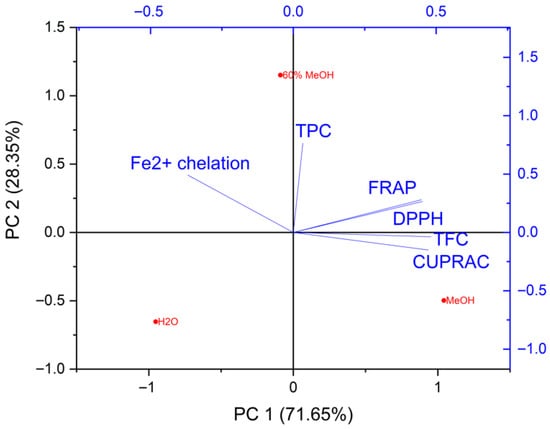

Principal component analysis (PCA) is often used in studies on the properties of plant extracts, as highlighted by numerous literature reports [18,63,64,65,66]. Therefore, in this study, chemometric analysis was used to determine the relationship between TPC, TFC, antioxidant, and Fe2+-chelating activity, as well as inhibitory activity against tyrosinase and hyaluronidase. In the analysis of the relationships between TPC, TFC, and both antioxidant and Fe2+-chelation activities, it was shown that the first two principal components accounted for nearly all of the data variability: PC1 = 71.65% and PC2 = 28.35% (Figure 4). This level of explained variance indicates that the two-dimensional model provides a comprehensive representation of the relationships among the variables examined.

Figure 4.

PCA biplot (loadings and sample scores) illustrating the relationships between active compound contents (TPC—total phenolic content, TFC—total flavonoid content), antioxidant activities (DPPH, FRAP, CUPRAC), and Fe2+-chelating ability, along with the distribution of extracts obtained with different solvents.

The first principal component (PC1) was characterised by high positive loadings for TFC (0.48173), CUPRAC (0.47288), DPPH (0.45254) and FRAP (0.44889) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Loading matrix (eigenvectors) for total polyphenols, flavonoids, and antioxidant activity variables on PC1 and PC2 in the PCA model.

These results show that PC1 is linked to the antioxidant activity of the analysed extracts, mostly due to their flavonoid content. The TPC variable showed only a small contribution to this component (0.03321), suggesting that the overall polyphenol content was not very important in explaining differences in this dimension compared with flavonoid levels. Notably, Fe2+-chelation activity exhibited a negative loading on PC1 (−0.37005), in contrast to the positive loadings of the antioxidant assays (DPPH, FRAP, CUPRAC). This indicates that Fe2+ behaves differently from the other variables along this principal component, highlighting that samples with higher flavonoid-driven antioxidant activity do not necessarily show higher Fe2+-chelating capacity. This distinction reflects the different mechanisms involved: while antioxidant assays measure radical scavenging and reducing potential, Fe2+ chelation reflects the ability to bind metal ions, which may not directly correspond to radical-neutralizing activity. By highlighting this contrast, the PCA results clearly demonstrate the independent contributions of metal-binding and radical-scavenging properties to the overall bioactivity of the extracts. The second principal component (PC2) was most strongly influenced by total polyphenol content, as evidenced by the very high positive loading for TPC (0.76492). Fe2+-chelation activity also contributed substantially to this component (0.49174), suggesting a correlation between these two parameters. The positive loadings for FRAP (0.28042) and DPPH (0.26518) indicate a partial relationship between reducing capacity and polyphenol content, although their impact on PC2 is clearly smaller than on PC1. Negative or near-zero loadings for CUPRAC (−0.15082) and TFC (−0.03735) indicate that these variables do not significantly contribute to sample differentiation along the PC2 axis. The spatial arrangement of vectors in the loading plot indicates the presence of two independent groups of parameters. The first group, comprising DPPH, FRAP, CUPRAC, and TFC, describes reducing activity associated with flavonoid content. The second group, represented by TPC and Fe2+-chelation capacity, reflects antioxidant properties arising from polyphenols with metal-binding abilities. This pattern suggests that different classes of phenolic compounds and distinct mechanisms of counteracting oxidative stress make separate contributions to the overall activity of the extracts, and that PCA effectively distinguishes these two modes of action.

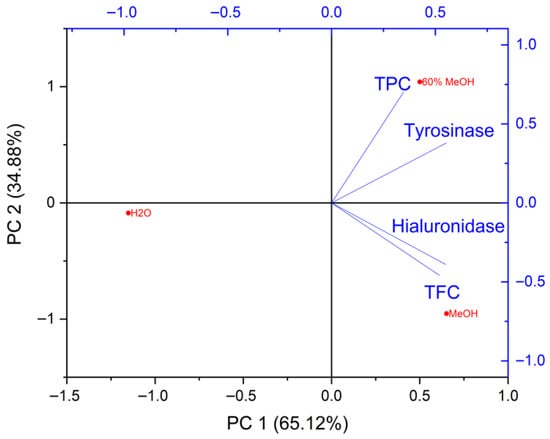

Subsequently, the relationships among TPC, TFC, and the inhibitory activity toward tyrosinase and hyaluronidase were evaluated. The first two principal components explained the entire data variability (PC1 = 65.12% and PC2 = 34.88%), allowing for a clear interpretation of the relationships among the analysed parameters (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

PCA biplot (loadings and sample scores) illustrating relationship of active compound contents (TPC—Total Phenolic Content, TFC—Total Flavonoid Content) and inhibitory activity against tyrosinase and hyaluronidase enzymes.

PC1 is characterised by high positive loadings for TFC (0.52024), hyaluronidase inhibition (0.5499), and tyrosinase inhibition (0.55369) (Table 6). This indicates that PC1 describes a shared gradient driven by flavonoid content and the ability of the samples to inhibit hyaluronidase and tyrosinase. The strong alignment of the vector directions suggests that the compounds responsible for enzymatic inhibitory activity may largely overlap with, or co-occur in, samples rich in flavonoids. The TPC variable (0.34696) also contributes to PC1, but to a lesser extent, implying that overall phenolic content is not the primary factor differentiating the samples along this dimension. PC2, dominated by TPC (0.70141), reflects variability associated with the general level of phenolic compounds. The moderate positive loading of tyrosinase inhibition (0.37997) on this component suggests a partial relationship between the enzyme-inhibitory activity and the total polyphenol pool, whereas the negative loadings of TFC (−0.45983) and hyaluronidase inhibition (−0.39013) indicate a lesser influence of TPC on these activities.

Table 6.

Loading matrix (eigenvectors) for total polyphenols, flavonoids, and enzyme activity variables on PC1 and PC2 in the PCA model.

3.3. Evaluation of the Wound-Healing Potential of Ptelea trifoliata Flower Extracts in Cell-Based Assays

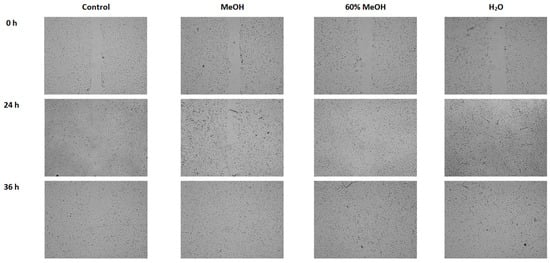

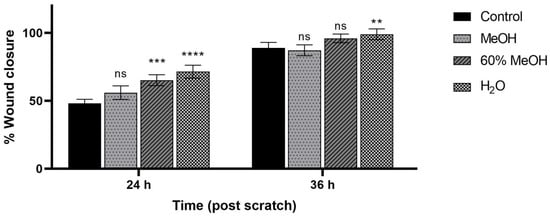

The wound-healing potential of different P. trifoliata flower extracts (at a concentration of 100 μg/mL) was evaluated using a scratch assay. The results, presented in Figure 6 and Figure 7, showed that scratch closure (relative to the control) was most pronounced after 24 h of incubation. At this time point, wound closure was statistically significantly increased following incubation with the H2O (71.5 ± 4.7%) and 60% MeOH (61.0 ± 5.3%) extracts, whereas the pure MeOH extract (54.6 ± 5.0%) did not differ significantly from the control (48.2 ± 2.9%). After 36 h of incubation, only the H2O extract showed a statistically significant difference compared to the control group. Although the 60% MeOH extract promoted greater scratch closure than the control (96.1 ± 3.2%, and 89.0 ± 4.0%, respectively), the difference was not statistically significant.

Figure 6.

Graphical representation of wound-healing properties of Ptelea trifoliata extracts (100 µg/mL) after 24 and 36 h of incubation.

Figure 7.

Wound-healing properties of Ptelea trifoliata extracts observed after 24 h and 36 h incubation of Hs27 cells (i.e., human normal skin fibroblasts). The samples, designated as MeOH, 60% MeOH, and H2O (tested at a concentration of 100 µg/mL). Results were statistically analysed by ANOVA with a post-hoc Tukey’s test. Statistical significance was designated as: “**” when p < 0.01, “***” when p < 0.001, “****” when p < 0.0001 (vs. control at the respective time points, 24 or 36 h).

Interestingly, our results indicate that the H2O extract promoted the highest cell migration and wound closure, despite exhibiting the lowest flavonoid content and antioxidant activity, and showing no inhibition of hyaluronidase activity. Notably, the chlorogenic acid content in the H2O extract was comparable to that of the 60% MeOH and MeOH extracts. It is evident that chlorogenic acid is recognised for its anti-inflammatory properties and the capacity to promote wound healing [38,39]; it may also contribute to the observed effect.

These results indicate that wound-healing activity is not solely dependent on antioxidant properties or flavonoid concentration. Previous studies have highlighted that water-soluble polysaccharides, amino acids, and certain phenolic acids (such as chlorogenic acid) can stimulate fibroblast proliferation and keratinocyte migration, which are critical processes in wound repair [63,67,68,69]. Several studies have also demonstrated that plant water extracts can be a source of amino acids [70] and polysaccharides [71,72]. In fact, in other plant species aqueous or mucilaginous extracts derived from flowers have been shown to accelerate wound healing. For instance, Opuntia ficus-indica flower mucilage significantly improved wound contraction and tissue remodelling in rat skin wound models [73], and Calendula officinalis flower extracts enhanced re-epithelialization and promoted wound healing by increasing fibroblast proliferation, fibroblast growth factor, and hydroxyproline levels, while reducing macrophage infiltration and inflammatory biomarker levels in the wound [74,75]. These findings support the plausibility that water-soluble macromolecules or hydrophilic constituents extracted from flowers can contribute to wound-healing effects—independently of flavonoid content or general antioxidant capacity. Therefore, it is plausible that bioactive compounds extracted by water, which may be absent or present in lower amounts in the 60% MeOH and MeOH extracts, are responsible for the enhanced wound closure observed in the H2O extract. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no published studies demonstrating the presence of such polysaccharides, mucilage, or other hydrophilic macromolecules in aqueous extracts from aerial parts (leaves or flowers) of P. trifoliata. Thus, confirming their presence in our H2O extracts would require dedicated phytochemical investigations such as bioassay-guided fractionation and chemical characterization.

4. Conclusions

The results of our study demonstrate that extracts from P. trifoliata flowers possess noteworthy biological potential. LC-MS/MS analysis confirmed that chlorogenic acid, rutin, hyperoside, and astragalin are present in the extracts from P. trifoliata flowers. The most potent antioxidant activity was shown by the MeOH extracts and 60% MeOH extracts, which correlated with flavonoid and polyphenol content. These properties suggest protection against oxidative stress, which is characteristic of the skin ageing process. The H2O extract and the 60% MeOH extract exhibited the strongest wound-healing activity in the scratch assay. This is consistent with their strong Fe2+-chelating properties, which may be related to the wound healing process. Moreover, it highlights the importance of water-soluble bioactive compounds of P. trifoliata in this process. In conclusion, the flowers of P. trifoliata represent a novel and interesting source of natural substances for use in dermatological and cosmetic products. More attention should be focused on alcohol–water extracts, which show a wide range of biological potential and may play a role in skin regeneration. However, further investigation is needed.

Partial results of this study were previously presented as a poster at the 3rd Natural Cosmetics International Meeting (Kielnarowa/Rzeszów, Poland, 17–19 September 2025).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16010088/s1, Table S1: LC-MS/MS parameters for qualitative identification of studied compounds.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S.-S., P.K. and J.C.-P.; methodology, E.S.-S., T.P., J.S. and N.R.; software, N.R. and J.S.; validation, J.S. and E.S.-S.; formal analysis, P.K., T.P., J.S., N.R. and E.S.-S.; investigation, P.K., T.P., J.S. and E.S.-S.; resources, J.C.-P. and M.K.-Ł.; data curation, P.K., J.S., T.P., N.R. and E.S.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S.-S., P.K., J.S. and N.R.; writing—review and editing, E.S.-S., J.S. and M.K.-Ł.; visualization, E.S.-S., J.S., T.P. and N.R.; supervision, E.S.-S.; project administration, E.S.-S.; funding acquisition, J.C.-P. and M.K.-Ł. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting reported results can be found within the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mateusz Sowelo from the Botanical Garden, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan for collecting the plant material used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bailey, V.L. Revision of the Genus Ptelea (Rutaceae). Brittonia 1962, 14, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Museum, M.P. Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee; Trustees of the Public Museum: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 1927.

- Habitat, H. AF Whiting’s Ethnography of a Traditional Indian Culture; University of Arizona: Tucson, AZ, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Vannier, L.; Poirier, J. Précis de Matière Médicale Homoeopathique; Doin & Cie: Paris, France, 1962; ISBN 2704003777. [Google Scholar]

- Petit-Paly, G.; Montagu, M.; Trémouillaux-Guiller, J.; Chenieux, J.C.; Rideau, M. Ptelea trifoliata (Quinine Tree, Hop Tree): In Vitro Culture and the Production of Alkaloids and Medicinal Compounds. In Medicinal and Aromatic Plants IV; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1993; pp. 280–295. [Google Scholar]

- Reisch, J.; Szendrei, K.; Novák, I.; Minker, E.; Pàpay, V. Inhaltsstoffe Der Blüten von Ptelea trifoliata: Arctigenin-Methyläther,(+)-Hydroxylunin Und Ptelefolin. Tetrahedron Lett. 1969, 10, 3803–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, I.E.A. Investigations on Indigenous Species of the Ruta-Ceae: Ptelea trifoliata. Herba Hung. 1970, 9, 23. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, M.F.D.G.F.; Fernandes, J.B.; Forim, M.R.; Vieira, P.C.; de Sá, I.C.G. Alkaloids Derived from Anthranilic Acid: Quinoline, Acridone, and Quinazoline. In Natural Products; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 715–859. ISBN 3642221440. [Google Scholar]

- Bibak, B.; Shakeri, F.; Barreto, G.E.; Keshavarzi, Z.; Sathyapalan, T.; Sahebkar, A. A Review of the Pharmacological and Therapeutic Effects of Auraptene. Biofactors 2019, 45, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Jin, L.; Huang, X.; Deng, H.; Shen, Q.; Quan, Z.; Zhang, C.; Guo, H.-Y. Arctigenin: Pharmacology, Total Synthesis, and Progress in Structure Modification. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2022, 37, 2452–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setzer, W.N.; Satyal, P. Essential Oil Compositions of Male and Female Flowers of Ptelea trifoliata. Am. J. Essent. Oils Nat. Prod. 2019, 7, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- El Mihyaoui, A.; da Silva, J.C.G.; Charfi, S.; Candela Castillo, M.E.; Lamarti, A.; Arnao, M.B. Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.): A Review of Ethnomedicinal Use, Phytochemistry and Pharmacological Uses. Life 2022, 12, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, V.; Nielsen, B.; Solas, M.; Ramírez, M.J.; Jäger, A.K. Exploring Pharmacological Mechanisms of Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) Essential Oil on Central Nervous System Targets. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viapiana, A.; Wesolowski, M. The Phenolic Contents and Antioxidant Activities of Infusions of Sambucus nigra L. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2017, 72, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, E.; Krol, T.; Adamov, G.; Minyazeva, Y.; Baleev, D.; Sidelnikov, N. Total Content and Composition of Phenolic Compounds from Filipendula Genus Plants and Their Potential Health-Promoting Properties. Molecules 2024, 29, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Książkiewicz, M.; Karczewska, M.; Nawrot, F.; Grabowska, K.; Szymański, M.; Cielecka-Piontek, J.; Studzińska-Sroka, E. Edible Flowers as Bioactive Food Ingredients with Antidiabetic Potential: A Study on Paeonia officinalis L., Forsythia × Intermedia, Gomphrena globosa L., and Clitoria ternatea L. Plants 2025, 14, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paczkowska-Walendowska, M.; Gościniak, A.; Szymanowska, D.; Szwajgier, D.; Baranowska-Wójcik, E.; Szulc, P.; Dreczka, D.; Simon, M.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Blackberry Leaves as New Functional Food? Screening Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Microbiological Activities in Correlation with Phytochemical Analysis. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studzińska-Sroka, E.; Bulicz, M.; Henkel, M.; Rosiak, N.; Paczkowska-Walendowska, M.; Szwajgier, D.; Baranowska-Wójcik, E.; Korybalska, K.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Pleiotropic Potential of Evernia Prunastri Extracts and Their Main Compounds Evernic Acid and Atranorin: In Vitro and In Silico Studies. Molecules 2024, 29, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiveron, A.P.; Melo, P.S.; Bergamaschi, K.B.; Vieira, T.M.F.S.; Regitano-d’Arce, M.A.B.; Alencar, S.M. Antioxidant Activity of Brazilian Vegetables and Its Relation with Phenolic Composition. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 8943–8957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinis, T.C.P.; Madeira, V.M.C.; Almeida, L.M. Action of Phenolic Derivatives (Acetaminophen, Salicylate, and 5-Aminosalicylate) as Inhibitors of Membrane Lipid Peroxidation and as Peroxyl Radical Scavengers. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1994, 315, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Studzińska-Sroka, E.; Dudek-Makuch, M.; Chanaj-Kaczmarek, J.; Czepulis, N.; Korybalska, K.; Rutkowski, R.; Łuczak, J.; Grabowska, K.; Bylka, W.; Witowski, J. Anti-Inflammatory Activity and Phytochemical Profile of Galinsoga Parviflora Cav. Molecules 2018, 23, 2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studzińska-Sroka, E.; Majchrzak-Celińska, A.; Bańdurska, M.; Rosiak, N.; Szwajgier, D.; Baranowska-Wójcik, E.; Szymański, M.; Gruszka, W.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Is Caperatic Acid the Only Compound Responsible for Activity of Lichen Platismatia glauca within the Nervous System? Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paczkowska-Walendowska, M.; Koumentakou, I.; Lazaridou, M.; Bikiaris, D.; Miklaszewski, A.; Plech, T.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. 3D-Printed Chitosan-Based Scaffolds with Scutellariae baicalensis Extract for Dental Applications. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Park, J.; Shin, D.W. The Molecular Mechanism of Polyphenols with Anti-Aging Activity in Aged Human Dermal Fibroblasts. Molecules 2022, 27, 4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fang, M.; Tu, X.; Mo, X.; Zhang, L.; Yang, B.; Wang, F.; Kim, Y.-B.; Huang, C.; Chen, L.; et al. Dietary Polyphenols as Anti-Aging Agents: Targeting the Hallmarks of Aging. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Ma, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Li, S. Recent Progress in Polyphenol-Based Hydrogels for Wound Treatment and Monitoring. Biosensors 2025, 15, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajammal, S.A.; Coffey, A.; Tan, S.P. Green Tea Polyphenols in Wound Healing: Therapeutic Mechanisms, Potential Applications and Challenges in Commercial Use for Diabetic Wound Healing. Processes 2025, 13, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rispo, F.; De Negri Atanasio, G.; Demori, I.; Costa, G.; Marchese, E.; Perera-del-Rosario, S.; Serrano-Candelas, E.; Palomino-Schätzlein, M.; Perata, E.; Robino, F.; et al. An Extensive Review on Phenolic Compounds and Their Potential Estrogenic Properties on Skin Physiology. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 11, 1305835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhan, M. The Promising Role of Polyphenols in Skin Disorders. Molecules 2024, 29, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floares, D.; Cocan, I.; Alexa, E.; Poiana, M.-A.; Berbecea, A.; Boldea, M.V.; Negrea, M.; Obistioiu, D.; Radulov, I. Influence of Extraction Methods on the Phytochemical Profile of Sambucus nigra L. Agronomy 2023, 13, 3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiliantari, S.; Iswandana, R.; Elya, B. Total Polyphenols, Total Flavonoids, Antioxidant Activity and Inhibition of Tyrosinase Enzymes from Extract and Fraction of Passiflora ligularis Juss. Pharmacogn. J. 2022, 14, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talcott Stewart, A.J.; Boylston, T.; Wilson, L.; Graves, W.R. Floral Aromatics of Ptelea: Chemical Identification and Human Response. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2022, 147, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Zheng, L.; Zhou, A.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Sun, W.; Gao, W.; Li, P.; Yang, H. High-Throughput Discrimination of Chlorogenic Acid Isomers in Lonicerae japonicae Flos by U-Shaped Mobility Analyzer-Mass Spectrometer. Food Chem. 2025, 493, 146130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, A.; de Paulis, T.; Trugo, L.C.; Martin, P.R. Effect of Roasting on the Formation of Chlorogenic Acid Lactones in Coffee. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 1505–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramabulana, A.-T.; Steenkamp, P.; Madala, N.; Dubery, I.A. Profiling of Chlorogenic Acids from Bidens pilosa and Differentiation of Closely Related Positional Isomers with the Aid of UHPLC-QTOF-MS/MS-Based In-Source Collision-Induced Dissociation. Metabolites 2020, 10, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, P.X. Quality Evaluation of Extracted Ion Chromatograms and Chromatographic Peaks in Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry-Based Metabolomics Data. BMC Bioinform. 2014, 15, S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, G.H.; Kim, H.W.; Lee, M.K.; Jeong, S.Y.; Bak, A.R.; Lee, D.J.; Kim, J.B. Characterization and Quantification of Flavonoid Glycosides in the Prunus Genus by UPLC-DAD-QTOF/MS. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 25, 1622–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, B.R. Application of HPLC and ESI-MS Techniques in the Analysis of Phenolic Acids and Flavonoids from Green Leafy Vegetables (GLVs). J. Pharm. Anal. 2017, 7, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, D.; Jung, Y.S.; Kim, M.-S.; Oh, S.E.; Nam, T.G.; Kim, D.-O. Developing and Validating a Method for Separating Flavonoid Isomers in Common Buckwheat Sprouts Using HPLC-PDA. Foods 2019, 8, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczak, Ł.; Znajdek-Awiżeń, P.; Bylka, W. The Use of Mass Spectrometric Techniques to Differentiate Isobaric and Isomeric Flavonoid Conjugates from Axyris amaranthoides. Molecules 2016, 21, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizzi, L.; Chatzitzika, C.; Gatt, R.; Valdramidis, V. HPLC Analysis of Phenolic Compounds and Flavonoids with Overlapping Peaks. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2020, 58, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.; Prasad, S.B. A Review on the Chemistry and Biological Properties of Rutin, a Promising Nutraceutical Agent. Asian J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2019, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgharian, S.; Hojjati, M.R.; Ahrari, M.; Bijad, E.; Deris, F.; Lorigooini, Z. Ruta Graveolens and Rutin, as Its Major Compound: Investigating Their Effect on Spatial Memory and Passive Avoidance Memory in Rats. Pharm. Biol. 2020, 58, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, F.B.; Sarandy, M.M.; Novaes, R.D.; Valacchi, G.; Gonçalves, R. V OxInflammatory Responses in the Wound Healing Process: A Systematic Review. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Quan, T. Oxidative Stress and Human Skin Connective Tissue Aging. Cosmetics 2016, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ayadi, A.; Salsbury, J.R.; Enkhbaatar, P.; Herndon, D.N.; Ansari, N.H. Metal Chelation Attenuates Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Vertical Burn Progression in a Porcine Brass Comb Burn Model. Redox Biol. 2021, 45, 102034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asem, N.; Abdul Gapar, N.A.; Abd Hapit, N.H.; Omar, E.A. Correlation between Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Contents with Antioxidant Activity of Malaysian Stingless Bee Propolis Extract. J. Apic. Res. 2020, 59, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muflihah, Y.M.; Gollavelli, G.; Ling, Y.-C. Correlation Study of Antioxidant Activity with Phenolic and Flavonoid Compounds in 12 Indonesian Indigenous Herbs. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Guo, J.; Yuan, J. In Vitro Antioxidant Properties of Rutin. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 41, 1060–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enogieru, A.B.; Haylett, W.; Hiss, D.C.; Bardien, S.; Ekpo, O.E. Rutin as a Potent Antioxidant: Implications for Neurodegenerative Disorders. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 6241017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-S.; Park, H.-R.; Lee, K.-A. A Comparative Study of Rutin and Rutin Glycoside: Antioxidant Activity, Anti-Inflammatory Effect, Effect on Platelet Aggregation and Blood Coagulation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, M. Plant-Derived Antioxidants: Significance in Skin Health and the Ageing Process. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadoss, T.; Weimer, D.S.; Mayrovitz, H.N. Topical Iron Chelator Therapy: Current Status and Future Prospects. Cureus 2023, 15, e47720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Žádníková, P.; Šínová, R.; Pavlík, V.; Šimek, M.; Šafránková, B.; Hermannová, M.; Nešporová, K.; Velebný, V. The Degradation of Hyaluronan in the Skin. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, M.; Günal-Köroğlu, D.; Kamiloglu, S.; Ozdal, T.; Capanoglu, E. The State of the Art in Anti-Aging: Plant-Based Phytochemicals for Skin Care. Immun. Ageing 2025, 22, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liyanaarachchi, G.D.; Samarasekera, J.K.R.R.; Mahanama, K.R.R.; Hemalal, K.D.P. Tyrosinase, Elastase, Hyaluronidase, Inhibitory and Antioxidant Activity of Sri Lankan Medicinal Plants for Novel Cosmeceuticals. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 111, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heijden, J.; Kolliopoulos, C.; Skorup, P.; Sallisalmi, M.; Heldin, P.; Hultström, M.; Tenhunen, J. Plasma Hyaluronan, Hyaluronidase Activity and Endogenous Hyaluronidase Inhibition in Sepsis: An Experimental and Clinical Cohort Study. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 2021, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Pan, L.; Wu, H.; Wang, S.; Tong, X.; Wu, S. Hyaluronidase: Structure, Mechanism of Action, Diseases and Therapeutic Targets. Mol. Biomed. 2025, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaylova, D.; Vrancheva, R.; Desseva, I.; Teneva, D.; Denev, P.; Krastanov, A. Influence of the Extraction Method on Phytochemicals Content and Antioxidant Activity of Sambucus nigra Flowers. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2023, 15, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gębalski, J.; Graczyk, F.; Załuski, D. Paving the Way towards Effective Plant-Based Inhibitors of Hyaluronidase and Tyrosinase: A Critical Review on a Structure–Activity Relationship. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2022, 37, 1120–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertel, W.; Peschel, G.; Ozegowski, J.; Müller, P. Inhibitory Effects of Triterpenes and Flavonoids on the Enzymatic Activity of Hyaluronic Acid-splitting Enzymes. Arch. Der Pharm. Int. J. Pharm. Med. Chem. 2006, 339, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, Y.-X.; Yin, S.-J.; Oh, S.; Wang, Z.-J.; Ye, S.; Yan, L.; Yang, J.-M.; Park, Y.-D.; Lee, J.; Qian, G.-Y. An Integrated Study of Tyrosinase Inhibition by Rutin: Progress Using a Computational Simulation. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2012, 29, 999–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iosageanu, A.; Mihai, E.; Seciu-Grama, A.-M.; Utoiu, E.; Gaspar-Pintiliescu, A.; Gatea, F.; Cimpean, A.; Craciunescu, O. In Vitro Wound-Healing Potential of Phenolic and Polysaccharide Extracts of Aloe Vera Gel. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ickovski, J.D.; Arsić, B.B.; Mitić, M.N.; Stojković, M.B.; Đorđević, M.M.; Stojanović, G.S. Chemometric Approach to the Composition of Flavonoid Compounds and Phenolic Acids and Antioxidant Potential of Artemisia Species from Different Habitats. Chem. Biodivers. 2022, 19, e202200365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milić, A.; Adamović, B.; Nastić, N.; Tepić Horecki, A.; Pezo, L.; Šumić, Z.; Pavlić, B.; Živanov, M.; Pavković, N.; Vojnović, Đ. Cluster and Principal Component Analyses of the Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Celery (Apium graveolens L.) Under Different Fertilization Schemes. Foods 2024, 13, 3652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studzińska-Sroka, E.; Paczkowska-Walendowska, M.; Kledzik, J.; Galanty, A.; Gościniak, A.; Szulc, P.; Korybalska, K.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Antidiabetic Potential of Black Elderberry Cultivars Flower Extracts: Phytochemical Profile and Enzyme Inhibition. Molecules 2024, 29, 5775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Niu, Y.; Xing, P.; Wang, C. Bioactive Polysaccharides from Natural Resources Including Chinese Medicinal Herbs on Tissue Repair. Chin. Med. 2018, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Chen, L.; Hou, Y.; He, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, D.; Hu, J. Self-Assembly of Chlorogenic Acid into Hydrogel for Accelerating Wound Healing. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2023, 228, 113440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arribas-López, E.; Zand, N.; Ojo, O.; Snowden, M.J.; Kochhar, T. The Effect of Amino Acids on Wound Healing: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on Arginine and Glutamine. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iordache, A.M.; Nechita, C.; Podea, P.; Șuvar, N.S.; Mesaroṣ, C.; Voica, C.; Bleiziffer, R.; Culea, M. Comparative Amino Acid Profile and Antioxidant Activity in Sixteen Plant Extracts from Transylvania, Romania. Plants 2023, 12, 2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.-Y.; Ye, J.-T.; Yang, J.; Shao, J.-Q.; Jin, W.-P.; Zheng, C.; Wan, C.-Y.; Peng, D.-F.; Deng, Q.-C. Co-Extraction of Flaxseed Protein and Polysaccharide with a High Emulsifying and Foaming Property: Enrichment through the Sequence Extraction Approach. Foods 2023, 12, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Feng, X.; Guo, J.; Wang, L.; Guo, X.; Zhu, X. A Review of Extraction, Purification, Structural Properties and Biological Activities of Legumes Polysaccharides. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1021448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, I.; Bardaa, S.; Mzid, M.; Sahnoun, Z.; Rebaii, T.; Attia, H.; Ennouri, M. Antioxidant, Antibacterial and in Vivo Dermal Wound Healing Effects of Opuntia Flower Extracts. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 81, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturan, Y.A.; Akin, I. Calendula officinalis Extract Enhances Wound Healing by Promoting Fibroblast Activity and Reducing Inflammation in Mice. Cutan. Ocul. Toxicol. 2025, 44, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Possa, G.d.O.K.; Chopek, S.; Pereira, A.V.; Koga, A.Y.; de Oliveira, M.R.P.; Costa, M.D.M. Calendula Glycolic Extract Enhances Wound Healing of Alginate Hydrogel. Acta Cir. Bras. 2024, 39, e399724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.