Abstract

Automatic modulation recognition (AMR) is crucial for signal interception and analysis in non-cooperative communication scenarios. To address the challenges of low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and model generalizability, this paper proposes a lightweight parallel network architecture that integrates convolutional layers, a channel attention mechanism, residual connections, and long short-term memory (LSTM) units. The model takes in-phase and quadrature (IQ) components of signals as inputs to jointly learn features for modulation scheme identification. Experiments are conducted on the expanded RML dataset to evaluate the model’s performance. Results indicate that the proposed network achieves recognition accuracy comparable to that of deep neural networks while requiring significantly fewer parameters. Furthermore, it demonstrates favorable generalization performance on other datasets, demonstrating its potential for efficient deployment under resource constraints.

1. Introduction

Automatic modulation recognition (AMR) is a critical step in signal detection for non-cooperative wireless communication systems [1]. It aims to identify the modulation scheme and estimate relevant parameters by analyzing intercepted signals without prior knowledge, playing a vital role in both civilian and military applications such as cognitive radio, spectrum monitoring, signal surveillance, and electronic warfare [2].

AMR employs two principal classical approaches: methods founded on maximum likelihood theory and those based on expert-defined feature extraction. Maximum likelihood-based methods formulate the modulation recognition task as a multiple hypothesis testing problem. A likelihood function is constructed based on the statistical model of the received signal, and a decision threshold is derived, often using criteria like the maximum a posteriori probability. The modulation type is identified by comparing the computed likelihood ratio of the signal under test against the predefined threshold. While these methods can achieve theoretical optimality under ideal conditions, their practical application is often constrained by high computational complexity and a strong dependence on complete prior knowledge of the signal parameters, making them susceptible to performance degradation in realistic, imperfect channel environments. Feature-based methods rely on manually engineered features that characterize differences between modulation schemes. It involves calculating one or more statistical or transform-domain characteristics—such as higher-order cumulants, cyclic spectrum features, or instantaneous parameters—from the signal under test. These extracted features are then compared against known theoretical values or used to train a classifier to determine the modulation type. Although generally less computationally complex, the performance of these methods is heavily dependent on the discriminative capability of the manually designed features, which may not be robust across diverse and dynamic channel conditions.

Deep learning (DL), a powerful data-driven approach, has achieved remarkable success in fields such as computer vision [3,4,5,6] and natural language processing [7]. In recent years, with the continuous expansion of deep learning applications, it has also opened up new research avenues in AMR, leading to a series of significant results. O’Shea et al. [8] pioneered the application of deep learning to AMR, showing that even a simple multi-layer convolutional neural network (CNN) could surpass traditional methods in classification performance. Subsequently, other neural network architectures—including recurrent neural networks (RNNs) [9], generative adversarial networks (GANs) [10], and their improved variants—have also been successfully applied to AMR, yielding competitive recognition performance. Daldal et al. [11] proposed applying the deep LSTM network model to digital modulated signals. West et al. [12] employed convolutional long short-term deep neural networks (CLDNN), integrating CNN and LSTM to enhance recognition accuracy. Xu et al. [13] introduced a three-stream automatic modulation recognition framework that analyzes signals across multiple dimensions, thereby improving recognition accuracy. Following the proliferation of transformer architectures in deep learning, they have been increasingly adopted for AMR. Among these pioneering works, Hamidi-rad et al. [14] introduced MCformer, which incorporated a self-attention mechanism for AMR for the first time. This model demonstrated the advantages of transformers in terms of both recognition accuracy and parameter efficiency. Dao et al. [15] proposed an alternative model that employs convolutional kernels of different sizes to extract multi-scale features from signals, which are then fed into a transformer encoder for final classification. This approach was also shown to surpass traditional models in accuracy while maintaining a favorable parameter count.

Based on established research in deep learning for signal processing, this paper proposes a hybrid architecture that integrates convolutional and recurrent neural networks. The model employs parallel data pathways to process the IQ components of the input signal independently. In each branch, spatial and temporal features are extracted through dedicated convolutional and LSTM layers, respectively. The feature representations learned by both pathways are subsequently merged and fed into a fully connected layer for final classification. The proposed model, evaluated on the augmented RML2016.10A dataset, demonstrates a high average detection accuracy of 92.1% at SNRs above 10 dB. This performance is comparable to that of the MCLDNN model, with only a 0.8% gap, yet it is achieved with a significant reduction of about 39% in the number of parameters. The model’s enhanced generalization is evidenced by its 87.3% accuracy on the RML2016.04C dataset under the same SNR conditions, marking a 2.2% improvement over a model trained without the proposed data augmentation.

2. Signal Model and Proposed Network

2.1. Signal Model

This paper considers a single-input single-output communication system and the received signal can be represented by

where is the modulated signal from the transmitter, is the channel impulse response and denotes additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN). The received signal is sampled n times at a rate by the analog to digital converter, which generates the discrete-time observed signal .

2.2. Network Structure

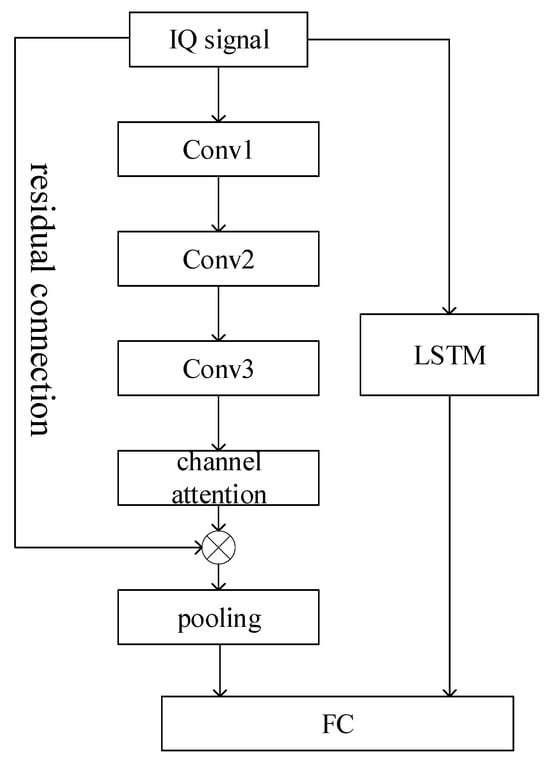

The structure of the proposed parallel CNN-LSTM network is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The structure of the proposed network.

The network employs a dual-channel parallel architecture that integrates 1-D convolutional neural networks and LSTM units, taking a 2 × 128 IQ signal sample as its input. The convolutional branch incorporates three convolutional layers enhanced with a channel attention mechanism and residual connections to facilitate feature refinement and gradient flow. Simultaneously, the LSTM branch processes sequential dependencies, with its final hidden state capturing long-range temporal patterns. The feature representations from both branches are subsequently fused and projected through a fully connected layer to generate the classification of the input signal. Overall, the IQ signals are both fed into two parallel branches: the convolutional neural network extracts localized features, while the LSTM network captures long-range temporal dependencies. Through their complementary strengths, the overall characteristics of the signals are more effectively extracted.

Each convolutional module comprises a convolutional layer, a BatchNorm layer, and a ReLU activation function, and a residual connection links the output of the last convolutional module back to its input, forming a residual block. Following feature extraction through these modules, the features are processed via global average pooling and subsequently fed into a fully connected layer for final recognition. A typical convolutional module can be represented as:

The network architecture accepts dual input channels, corresponding to the IQ components of the signal. A critical design trade-off was made between feature extraction capability and model complexity. The network utilizes convolutional layers with a kernel length of 8 and operates with a stride of 1 to capture both inter- and intra-symbol characteristics, while a consistent channel count of 32 across these layers balance parameter efficiency and computational performance. To preserve the original temporal length of the input samples throughout convolution, zero-padding is applied symmetrically along both ends of the input sequence. The network employs a consistent post-convolutional module: Batch Normalization immediately followed by ReLU activation. This module is instrumental in stabilizing training dynamics and enhancing gradient flow. BatchNorm’s normalization of activations within a mini-batch curbs unwanted shifts in data distribution, which in practice permits faster convergence and provides a regularization effect. Coupled with ReLU, which ensures non-linear transformation, the model gains the capacity to learn complex patterns while significantly reducing the risk of vanishing gradients during backpropagation.

The channel attention layer adaptively weights convolutional outputs to enhance feature representation. By emphasizing informative channels and suppressing less relevant ones, it highlights discriminative features. The weighting factors are dynamically computed via aggregated average-pooled and max-pooled features across spatial dimensions, expressed as:

where represents the maximum value from outputs of each channel, while represents the mean. The softmax function converts the sum of the maximum and average values across all channels into weighted values, which employs a gentle reweighting strategy that enhances prominent features rather than suppressing less dominant ones.

Residual connections between convolutional inputs and outputs form residual modules, while average pooling layers downsample feature maps to retain salient information with reduced computational cost. This design enhances translation invariance and provides condensed features for final recognition via fully connected layers.

The LSTM layer comprised two stacked layers, each with 128 hidden units. It processed input samples of IQ signals with a dimension of 2 × 128. The final hidden state from the last time step of the LSTM was extracted to serve as the output for subsequent classification layers.

The parameters for each structure are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters of network structures.

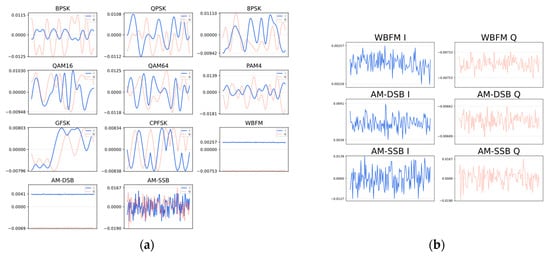

3. Datasets

The experiments utilize two publicly available benchmark datasets for wireless signal recognition: RML2016.10A and RML2016.04C. These datasets encompass 11 modulation types, including both digital and analog schemes such as BPSK, QPSK, 8PSK, QAM16, QAM64, CPFSK, GFSK, PAM4, AM-DSB, AM-SSB, and WBFM. Signals are generated across 20 different SNRs conditions, ranging from –20 dB to 18 dB in increments of 2 dB, making them suitable for evaluating model robustness under various noise levels. Each data sample is represented as a complex-valued time-series containing 128 sampling points, IQ components. The datasets were synthesized using GNU Radio, incorporating real-world channel impairments such as AWGN, multipath fading, frequency offset, and sampling rate offset to emulate practical communication conditions [16]. The fundamental characteristics of the datasets are summarized in Table 2, and time-domain waveforms for one sample of each type selected from the RML2016.10A dataset are shown in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Details of datasets.

Figure 2.

Time domain signals in dataset RML2016.10A. (a) Time-domain waveforms of 11 modulated signals; (b) Zoomed schematic diagram of three analog modulated signal waveforms.

Additionally, samples with SNRs below −10 dB produce negligible recognition performance, highlighting the model’s limited robustness under low-SNR conditions. Furthermore, networks trained on a single dataset exhibit limited generalization capability when evaluated on data from different distributions. For example, a network trained exclusively on the RML2016.10A dataset demonstrates reduced accuracy when tested on samples from the RML2016.04C dataset.

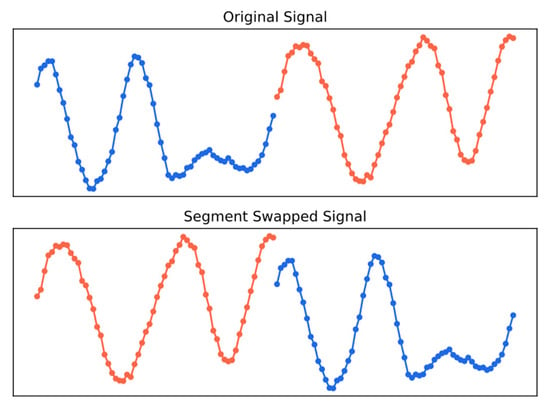

To enhance the generalization capability of the model, the 10A dataset is systematically expanded through the following procedure. Each normalized sample is augmented by introducing minor perturbations, including the injection of a small amount of random noise and the application of a slight random carrier frequency offset. Leveraging the symbol-based nature of modulated signals, rearranging or masking certain segments within the samples effectively increases their diversity without altering the key features required for modulation recognition [2,17]. Finally, an augmented sample with misaligned segments is created by swapping the first and second halves of the perturbed sample, thereby further enhancing the variability of the dataset. As the segment swapping operation only rearranges the sequence of segments while leaving the individual sampling points and local features intact, the modulated information remains accurately represented. The segment swapping is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The schematic of segment swapping.

4. Implementation Details

The model was trained on a server equipped with an NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPU using single-precision floating-point arithmetic. A batch size of 512 was used along with an initial learning rate of 0.001, which was reduced by 50% every 10 epochs until the learning rate reached a minimum value of 0.0001. The optimization was performed using the Adaptive Moment Estimation (Adam) algorithm. The dataset was partitioned into training, validation, and test subsets with an 8:1:1 ratio. The cross-entropy loss function was employed throughout all training phases:

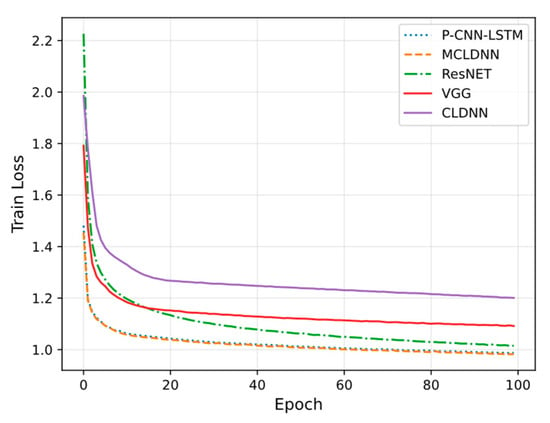

where represents the total number of categories, denotes the network’s logit outputs, and represents the probability of classification as . The train loss is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The train loss curves.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Recognition Accuracy

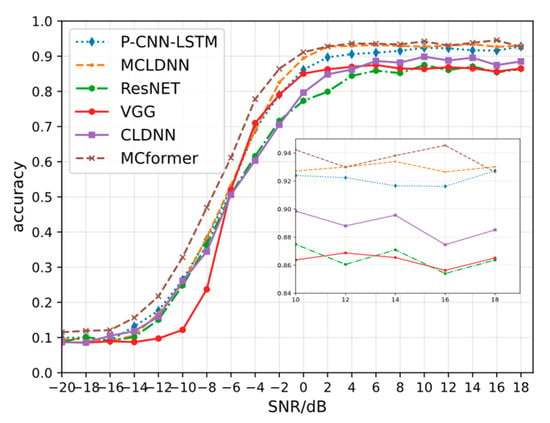

Figure 5 provides a comparative performance analysis between the proposed parallel CNN-LSTM architecture (denoted as P-CNN-LSTM) and several established modulation recognition networks, including VGG [18], ResNet [4], CLDNN [19], MCLDNN [13] and MCformer [14]. Among these, VGG represents a pure convolutional network with 7 convolutional layers, while ResNet enhances the convolutional architecture through the incorporation of residual connections.

Figure 5.

Recognition accuracy comparison between P-CNN-LSTM and the other networks.

Unlike CLDNN and MCLDNN, where features are passed sequentially from CNN to LSTM, the proposed network feeds the raw IQ signals in parallel to both CNN and LSTM branches. This architecture enables the direct and concurrent extraction of features, which are then fused to make the final modulation decision. The proposed hybrid parallel model demonstrates a significant performance improvement over stand-alone convolutional networks, achieving approximately 6% higher accuracy in high SNR conditions. This enhancement can be attributed to the model’s capacity to simultaneously capture spatial features through convolutional layers and temporal dependencies via LSTM units, which is particularly advantageous in decoding complex modulation patterns. At low SNRs, the proposed model exhibits a marginal but consistent advantage over both MCLDNN and CLDNN. Nevertheless, its overall recognition accuracy remains lower than that of the transformer-based MCformer across the majority of the evaluated SNR range.

Under low SNR conditions, the overall recognition accuracy remains relatively low across all methods compared. Among them, only MCformer demonstrates performance improvement. This limitation may be attributed to the inherent constraints of the model architecture itself, as both convolutional and LSTM layers struggle to effectively extract discriminative signal features for modulation recognition and classification in low-SNR environments.

5.2. Ablation Study

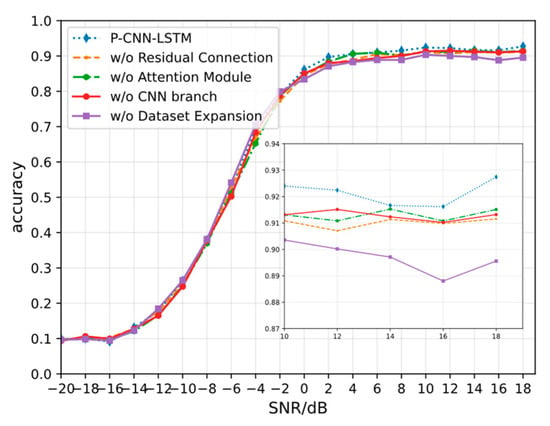

We conduct an ablation study to inspect the contribution of each component in the overall architecture. We selectively remove other components of P-CNN-LSTM to evaluate the effectiveness of each module. We compare the experimental results of the complete structure with three variations: removing the residual connection, removing the attention module, and removing the CNN branch. We also compare the performance without the application of dataset expansion. The results are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Ablation study of the P-CNN-LSTM architecture.

The complete model performs best and removing each module leads to a decrease. This demonstrates the complementary advantages of each module, and their combination forms a superior model. The slight performance impact of removing the attention module aligns with expectations, as the block mainly conducts channel-wise weighting on convolutional layer outputs without incorporating extra information from signals.

We also evaluate the recognition accuracy using the non-augmented dataset for training. The results confirm that the dataset augmentation is crucial for achieving performance improvement.

5.3. Computational Efficiency

As shown in Table 3, the proposed model demonstrates a significant reduction in complexity compared to MCLDNN, achieving approximately 39% fewer parameters and 46% lower FLOPs. While it does not exhibit a distinct advantage over a convolutional network in these theoretical metrics, it achieves a substantial 61% reduction in inference time compared to MCLDNN, with its inference latency being comparable to that of a ResNet architecture. Notably, among all models compared, MCformer possesses the lowest parameter count and FLOPs; however, it exhibits the longest inference time.

Table 3.

Computational efficiency comparison between P-CNN-LSTM and the other networks.

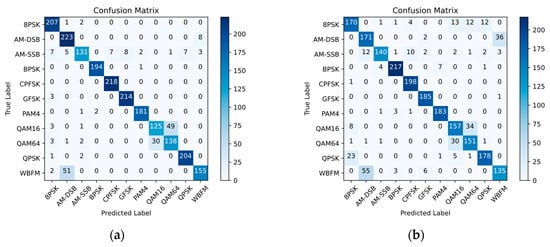

5.4. Confusion Matrix and Generalization Capability

As shown in Figure 7a at a high SNR of 18 dB, the model demonstrates strong discriminative performance for most digital modulation schemes, as evidenced by the clear dominance of the diagonal entries. However, it exhibits occasional confusion between certain analog modulation types, specifically AM-DSB and WBFM. This persistent challenge in distinguishing these variants, even under favorable noise conditions, is likely attributable to their intrinsic similarity in time-domain characteristics in this dataset, which can be compared in Figure 2b.

Figure 7.

Confusion matrix of P-CNN-LSTM at an SNR of: (a) 18 dB; (b) 0 dB.

Furthermore, a non-negligible degree of confusion is observed between the QAM16 and QAM64 modulation schemes. This misclassification primarily stems from their inherent structural similarity. According to their modulation principles, the time-domain and frequency-domain characteristics of these two kinds of signals exhibit considerable commonality, often leading to interpretation ambiguity and consequent confusion by the classifier.

At an SNR of 0 dB, the model exhibits a degradation in overall accuracy while demonstrating robust feature separation, as evidenced by the stable confusion patterns between specific modulation pairs.

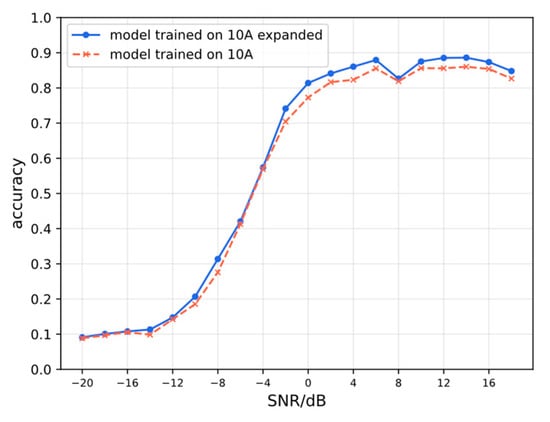

Figure 8 illustrates the performance comparison on the RML2016.04C dataset between models trained with and without the expanded dataset. The superior performance of the model utilizing the augmented data validates the effectiveness of the data expansion method detailed in Section 3 in enhancing model generalization. The core principle behind this improvement is that the segment swapping operation enriches the dataset by creating new sample variations. Crucially, this rearrangement preserves the essential modulation characteristics of the signals, thereby enhancing data diversity without fundamentally altering the underlying features critical for classification.

Figure 8.

The generalization capability of models trained on different datasets, when evaluated on RML2016.04C.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we propose a parallel dual-channel network and train the model on a segment swapped expanded dataset to tackle the problem of automatic modulation recognition in non-cooperative communication scenarios. The proposed architecture is designed to enhance recognition performance while maintaining a lightweight parameter footprint.

Experimental results show that the model achieves approximately 6% higher accuracy compared to stand-alone convolutional networks, reaching an average recognition accuracy of about 92.1% at SNRs above 10 dB. Furthermore, while delivering accuracy comparable to MCLDNN, the proposed network contains about 39% fewer parameters and 46% lower FLOPs, reducing computational complexity.

The model exhibits partial ambiguity in signal recognition, yet this ambiguity does not escalate with decreasing SNR. The subtle feature variations within these signals remain difficult for the proposed approach to distinctly differentiate.

These findings demonstrate that the model effectively balances recognition performance and efficiency. However, the performance of the proposed model remains inferior compared to state-of-the-art approaches. Future work will focus on further research regarding dataset processing and the recognition of signals under low SNRs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.L. and S.L.; Methodology, W.L. and S.L.; Software, W.L.; Validation, W.L. and X.Y.; Formal analysis, W.L., G.H. and W.Z.; Investigation, X.Y., J.W. and W.Z.; Resources, S.L., G.H. and J.W.; Data curation, X.Y.; Writing—original draft, W.L.; Writing—review & editing, S.L., X.Y., J.W. and W.Z.; Visualization, W.L.; Supervision, X.Y., G.H. and J.W.; Project administration, G.H. and J.W.; Funding acquisition, S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Article Processing Charge was funded by Space Star Technology Co., Ltd.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.deepsig.ai/datasets (accessed on 1 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

Weixuan Long, Shenyang Li, Xuehui Yu, Guangjun He, Jiang Wang and Wenbo Zhao were employed by Space Star Technology Co., Ltd. The research was conducted with no conflicts of interest.

References

- Peng, S.; Sun, S.; Yao, Y. A survey of modulation classification using deep learning: Signal representation and data preprocessing. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 33, 7020–7038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Xing, H.; Wang, C.; Zhou, H.; Hou, B.; Jiao, L. SigDA: A superimposed domain adaptation framework for automatic modulation classification. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2024, 23, 13159–13172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Metz, L.; Chintala, S. Unsupervised representation learning with deep convolutional generative adversarial networks. arXiv 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; Volume 1. (Long and Short Papers). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, T.J.; Corgan, J.; Clancy, T.C. Convolutional radio modulation recognition networks. In Proceedings of the Engineering Applications of Neural Networks: 17th International Conference, Aberdeen, UK, 2–5 September 2016; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 213–226. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea, T.J.; Hitefield, S.; Corgan, J. End-to-end radio traffic sequence recognition with recurrent neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Global Conference on Signal and Information Processing (GlobalSIP), Washington, DC, USA, 7–9 December 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; He, Z.; Nie, J.; Zhang, W. A novel attention cooperative framework for automatic modulation recognition. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 15673–15686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daldal, N.; Yıldırım, Ö.; Polat, K. Deep long short-term memory networks-based automatic recognition of six different digital modulation types under varying noise conditions. Neural Comput. Appl. 2019, 31, 1967–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, N.E.; O’shea, T.J. Deep architectures for modulation recognition. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Dynamic Spectrum Access Networks (DySPAN), Baltimore, MD, USA, 6–9 March 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Luo, C.; Parr, G.; Luo, Y. A spatiotemporal multi-channel learning framework for automatic modulation recognition. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2020, 9, 1629–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi-Rad, S.; Jain, S. MCformer: A Transformer Based Deep Neural Network for Automatic Modulation Classification. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM), Madrid, Spain, 7–11 December 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, T.; Noh, D.; Pham, Q.; Hasegawa, M.; Sekiya, H.; Hwang, W. VT-MCNet: High-Accuracy Automatic Modulation Classification Model Based on Vision Transformer. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2024, 28, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’shea, T.J.; West, N. Radio machine learning dataset generation with gnu radio. In Proceedings of the GNU Radio Conference, Boulder, CO, USA, 12–16 September 2016; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Y.; Lu, Z.; Zeng, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, J. Enhancing Automatic Modulation Recognition Through Robust Global Feature Extraction. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 74, 4192–4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Andrew, Z. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainath, T.N.; Vinyals, O.; Senior, A.; Sak, H. Convolutional, long short-term memory, fully connected deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Brisbane, Australia, 19–24 April 2015; pp. 4580–4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.