Abstract

With the gradual depletion of shallow high-grade mineral resources, global mining activities are shifting toward deeper regions with more complex geological conditions. Rocks exhibit significantly different mechanical responses under high confining pressure environments, posing new challenges to deep mining safety. To address this, this study proposes an optimized rock damage constitutive model that characterizes the influence of confining pressure on rock mechanical behavior, incorporating its peak strength enhancement effect and regulatory mechanism on post-peak softening behavior. The core innovation lies in establishing an inverse relationship between softening parameters and confining pressure, as confining pressure increases, softening parameters decrease. This inverse relationship enables the model to reasonably reflect the inhibitory effect of confining pressure on the rock softening process, meaning that under higher confining pressure, the material exhibits slower stress decay and more pronounced ductile characteristics. This model can consistently describe brittle responses under low confining pressure and ductile responses under high confining pressure. The findings provide reliable theoretical support for predicting rock mass failure and conducting stability analysis under deep mining conditions.

1. Introduction

To ensure the safety and efficiency of mining and related engineering activities, rock masses in the field are typically subjected to three-dimensional confining stresses at different levels, and the magnitude of the confining pressure has a critical influence on overall stability [1]. Rocks exhibit markedly different mechanical responses and failure modes under different confining pressures; therefore, a systematic understanding of how confining pressure affects rock deformation and failure behavior is of great theoretical significance and practical engineering value [2,3,4,5]. Numerous studies have shown that, as confining pressure increases, the macroscopic stress–strain curve of brittle rocks evolves from a typical brittle instability at low confinement—characterized by a rapid loss of load-bearing capacity after the peak—into a ductile/plastic deformation response featuring gradual softening and even strain hardening [6,7,8,9,10]. Confining pressure plays a dominant role in governing stress–strain nonlinearity, stiffness degradation, and failure patterns, so that accurately predicting and effectively controlling rock failure under complex confining-pressure conditions has become a key scientific challenge in deep engineering [11,12,13].

From a microscopic perspective, rock damage is generally regarded as the cumulative result of multiple meso-scale mechanical mechanisms. Existing experiments and micro-observations indicate that, under external loading (such as confining pressure, impact, or shear stress), stress is prone to concentrate in micro-defect regions such as initial pores and grain boundaries. New microcracks usually nucleate first in these locations and then propagate along weak structural planes, such as grain boundaries or within brittle minerals. As the load continues to increase, these local microcracks gradually coalesce and penetrate, forming fracture bands and damaged zones at a certain scale, the direct consequence of which is a reduction in the effective load-bearing area and a degradation of stiffness [14,15,16,17,18].

From a macroscopic perspective, the above-mentioned micro-scale degradation processes manifest at the continuum scale as an overall reduction in stiffness, attenuation of strength, and accumulation of irreversible deformation, namely the evolution of “damage.” Damage constitutive models introduce a damage variable into the macroscopic constitutive relationship to equivalently characterize this degradation behavior induced by the evolution of micro-defects [19,20,21,22].

On this basis, a large number of rock damage and damage–plasticity constitutive models have been proposed to describe the deformation and failure processes of rocks under different stress states. Many models introduce confining-pressure terms into the yield criterion or strength parameters, and are thus able to satisfactorily fit the peak strength and the shape of the yield surface under different confining pressures [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. There are also studies that consider the influence of confining pressure on plastic deformation and damage accumulation in the damage evolution laws and dilation relationships [32,33]. On this basis, a large number of rock damage or damage–plasticity constitutive models have been developed to describe the deformation and failure processes of rocks under various stress conditions [34,35,36]. However, when it comes to the treatment of post-peak softening behavior, the parameters controlling the softening process are often still regarded as constants independent of confining pressure, making it difficult to simulate and illustrate the evolution of softening behavior with changing confining pressure.

Therefore, based on the damage constitutive framework proposed by Mukherjee et al. [37], the present study focuses on the influence of confining pressure on post-peak softening behavior. By introducing a set of softening control parameters that vary with confining pressure into the definition of the equivalent plastic strain, the proposed model can more accurately reproduce the continuous transition of rock mechanical response from brittle failure to ductile/plastic deformation as confining pressure gradually increases, thereby dynamically reflecting the controlling effect of confining pressure on rock behavior. As the confining pressure increases, the softening parameters decrease, and the corresponding stress–strain response evolves from a steep post-peak softening to a weakened softening behavior. Calibration and validation of the model using monotonic triaxial compression test data for representative rocks such as sandstone, marble, and granite demonstrate that the proposed formulation not only reproduces the complete stress–strain curves from initial loading to the residual strength stage with satisfactory accuracy, but also reasonably captures the reduction in post-peak softening as confining pressure increases, thus providing a more reliable constitutive basis for rock mass failure prediction and stability analysis in mining and related engineering applications.

2. Presentation of the Improved Damage–Plasticity Constitutive Model

2.1. Stress–Strain Relationship

Investigations into the mechanical behavior of materials reveal that most materials, including concrete and rock, possess intrinsic heterogeneity and unavoidable microstructural imperfections. Under the combined influence of external loading and time-dependent effects, microcracks, voids, and other defects gradually develop within the material, leading to a reduction in its load-bearing capacity. In the present study, a sign convention is adopted such that compressive stresses are taken as positive and tensile stresses as negative. On this basis, the evolution of energy associated with material deformation is considered, since damage not only leads to the degradation of material properties but also alters the way energy is stored and dissipated.

To capture this coupling effect, a free energy density function was formulated by previous researchers, which describes how damage influences energy under different deformation modes (volumetric and shear) and stress states (tension and compression), as given below:

where represents the free energy density stored per unit volume of material; is the damage variable (taking values in [0, 1], where indicates no damage and indicates complete damage); is the Heaviside unction, where is the first invariant of the stress tensor reflecting hydrostatic pressure, defined as . Here, the Heaviside function is employed to distinguish the stress state, where corresponds to compression and corresponds to tension. and are bulk modulus and shear modulus, respectively, corresponding to the material’s resistance to volumetric and shear deformation; and denote total volumetric strain and plastic volumetric strain, respectively; and denote total shear strain and plastic shear strain, respectively. The stress relationship can be derived from Equation (1) by differentiating the free energy function with respect to strain:

Here, denotes the hydrostatic (mean) stress and denotes the shear stress invariant corresponding to deviatoric deformation. These two stress invariants will be used in the subsequent yield function and plastic potential .

Generalized stress–strain constitutive relationship based on secant stiffness:

where is the Cauchy stress tensor, is the total strain tensor, is the plastic strain tensor, and is the secant elastic stiffness tensor.

The tangent elastic stiffness can be expressed as:

where is the Kronecker delta.

2.2. Formulation of the Yield Criterion Coupled with Damage Evolution

The yield function y is expressed as follows:

where , , and .

, , and are all functions of the damage variable :

where and represent the initial yield strengths under isotropic triaxial compression and triaxial tension, respectively. , , and are parameters controlling the initial yield surface, while denotes the slope of the residual yield surface under triaxial conditions. As seen from Equation (10) evolves from to as the damage variable increases. In this model, the yield–failure function is defined as , where pand qrepresent hydrostatic stress and shear stress, respectively, and is the damage variable describing the progressive degradation of the material from an intact state to complete failure.

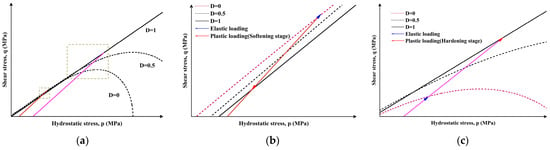

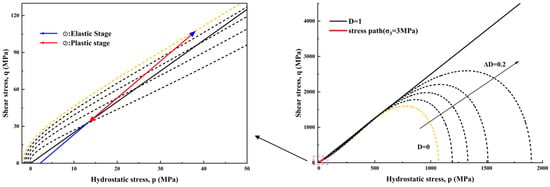

Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of the damage-related yield surface in the – plane and the corresponding loading processes under triaxial compression in the proposed damage–plasticity constitutive model. As shown in Figure 1a, as the damage variable gradually increases from 0 to 1, the yield surface progressively degrades from the initial yield surface to the residual yield surface, representing the continuous reduction in material strength and stiffness. When , the material is in an intact state and the stress point lies strictly inside the yield surface, so that only reversible elastic deformation occurs. Once the loading process brings the stress state onto the initial yield surface, the material enters the elastic–plastic regime and experiences progressive stress softening and stiffness degradation under continued loading. Ultimately, when , the residual yield surface is reached, corresponding to a state of complete failure.

Figure 1.

Evolution of the damage-related yield surface in the p–q plane and typical loading processes under triaxial compression: (a) yield surfaces corresponding to different damage levels. The yellow box highlights the region magnified in subfigures (b,c). The red line represents the stress path under low confining pressure, while the pink line corresponds to the stress path under high confining pressure. (b) Loading process at relatively low mean stress/low confinement, showing pronounced post-peak softening; (c) Loading process at relatively high mean stress/high confinement, showing pronounced post-peak hardening.

Figure 1b shows a typical loading process under triaxial compression with a relatively small mean stress (i.e., low confining pressure). In the initial stage, the stress state evolves almost linearly along the elastic loading line (blue segment). After the stress point reaches the yield surface, the response switches to an inelastic loading process (red segment), characterized by damage accumulation and contraction of the yield surface. During this stage, the damage variable increases continuously, reflecting the initiation and propagation of microcracks within the material. At the macroscopic scale, this is manifested as a pronounced post-peak softening behavior and a gradual loss of load-carrying capacity.

In contrast, Figure 1c presents the loading process under a relatively large mean stress (i.e., higher confining pressure). In this case, the stress state also starts from an elastic loading segment and then enters a plastic regime, but the response exhibits a clear hardening trend after yielding (red segment): the shear stress continues to increase with increasing , indicating a strain-hardening behavior. As loading proceeds, damage still develops and the yield surface gradually expands outward until , at which point failure occurs. Taken together, Figure 1b,c demonstrate that the proposed model can capture both post-peak softening at low confinement and pronounced post-yield hardening at higher confinement within a unified damage–plasticity framework.

Throughout this evolution process, the plastic strain is coupled with the damage variable , and the plastic strain increment follows a non-associated flow rule. This formulation provides a reasonable description of the isotropic failure and strength degradation characteristics of brittle materials such as rock under complex triaxial loading conditions. In contrast, Figure 1c illustrates the evolutionary characteristics under triaxial compression stress paths with relatively large value. The stress state initially grows along an elastic path before entering a plastic hardening phase (red line), where the material exhibits strain-hardening characteristics. However, as loading continues, damage progressively develops, causing the yield surface to gradually expand outward until reaching , ultimately leading to failure. As shown in Figure 1b,c, the model consistently captures both hardening and softening responses under different loading regimes.

Throughout the evolution process, plastic strain is coupled with the damage variable , and the plastic strain increment follows a non-associated flow rule. This approach reasonably reflects the isotropic failure and strength degradation characteristics of brittle materials such as rock under complex stress paths.

To describe the expansion behavior of materials, the non-associated flow rule is introduced. The plastic potential is calibrated using experimental data to characterize the expansion behavior. Its specific expression is as follows:

where is the dimensionless dilation parameter. When the material is fully damaged (i.e., the stress state lies on the residual yield plane ), the volumetric strain no longer changes significantly with loading and reaches a critical stable state. The plastic flow rule is governed by the proposed plastic potential:

where is the damage–plasticity multiplier.

2.3. Coupled Damage–Plasticity Evolution and Pressure-Dependent Softening Parameter

Even rocks that appear intact to the naked eye often contain microscopic defects, including microcracks and microvoids. Under inelastic loading, pre-existing microcracks first close and may subsequently reopen; new cracks nucleate and extend; microvoids nucleate, grow, or collapse; and defects aggregate and localize. These micro-level processes translate into macroscopic responses, leading to either a reduction (softening) or an increase (hardening) in the rock’s strength and stiffness. Damage–plasticity models aim to describe the mechanical behavior of materials during damage and plastic deformation processes. The plastic strain tensor reflects the plastic deformation of rock, representing the irreversible deformation component; damage variables quantify the extent of damage caused by the accumulation of micro-defects within the rock. During rock loading, plastic deformation and damage are not independent; they interact and co-evolve. By establishing an exponential relationship between the damage quantity and the increment in cumulative plastic strain , it is possible to quantitatively reflect how the increase in plastic strain induces changes in damage quantity. The expression is as follows:

It is assumed that:

The incremental plastic strain can be decomposed into the volumetric plastic strain increment and the shear plastic strain , that is,

Among them is the volume (volume strain) increment (scalar), is the deviatoric increment, , is the Kronecker delta (unit vector component).

The equivalent shear strain increment is typically defined as

It follows that

By substituting Equation (17) into Equation (16), we obtain:

where and are model parameters controlling the influence of volumetric plastic strain increment and shear plastic strain increment on the total plastic strain increment, respectively.

Volumetric plastic strain primarily reflects microcrack opening and shear-induced dilatancy. As the confining pressure increases, these mechanisms are progressively constrained, and their contribution to damage evolution diminishes. Shear plastic strain is mainly governed by slip along fractures; this slip is likewise suppressed with rising , although generally less strongly than crack opening. In short, confining pressure inhibits both opening and slip, but to different degrees. To capture these effects, we model the dependence of the coefficients and on using a decreasing exponential form:

2.4. Stress Update Calculation

Materials undergoing plastic deformation and damage evolution generally exhibit nonlinear mechanical behavior, characterized by a stiffness that varies during the course of deformation. To accurately capture this transient nonlinear response, the tangent stiffness tensor of the proposed damage–plasticity model is derived for numerical implementation. Starting from Equation (4), the stress-rate tensor can be expressed as

where is the elastic stiffness tensor defined in Equation (5), is the secant flexibility tensor, is the plastic strain tensor, and is the scalar damage variable introduced in Section 2.1. From the plastic flow rule (Equation (12)), the volumetric and shear plastic strain rates are obtained as

where is the plastic potential defined in Equation (11), and are the stress invariants introduced in Equations (2) and (3), and is the damage–plasticity multiplier. According to Equation (13), the evolution rate of the damage variable can be written as:

where is the accumulated plastic shear strain and and are model parameters controlling the contributions of volumetric and shear plastic strain, respectively, as given in Section 2.3.

where is the yield function defined in Equation (6). Substituting Equations (21) and (23) into Equation (24) leads to the rate of the damage–plasticity multiplier :

For time integration, the Cauchy stress is written in incremental form as

where and denote the stress tensors at the previous and current time steps, respectively, and is the stress increment. An elastic trial stress is first computed as:

With the trial stress increment given by:

where is the elastic tangent stiffness at time step , and is the total strain increment from to . The yield function is evaluated at the trial state to determine the loading condition of the material. In the numerical implementation, an elastic predictor–inelastic corrector (return-mapping) scheme is adopted. For a given strain increment , the trial stress state is first computed by assuming purely elastic behavior during the increment. The yield function is then evaluated at this trial state. If , the material response remains elastic, and the trial stress is directly accepted. If , the material enters the inelastic regime, and a stress-return algorithm is required to project the trial state back onto the yield surface by accounting for the coupled plastic and damage evolution. A semi-implicit stress-return algorithm is employed. The yield function at the end of the increment is approximated by a first-order Taylor expansion around the trial state:

where is the value of the yield function at the end of the time step, and the partial derivatives are evaluated at the trial state. From Equation (21), the stress corrector associated with plastic flow and damage can be written as:

where and are the plastic strain and damage increments, respectively. Substituting the flow rule and the incremental damage expression into Equation (29) yields the increment in the damage–plasticity multiplier :

where is the accumulated plastic shear strain at time step .

Once is obtained at each time step, the plastic strain increment and the damage increment are computed from the flow rule and the damage evolution equation, and the corresponding stress corrector is evaluated from Equation (30). The updated stress increment and stress tensor are then given by

Therefore, at each integration point, the stress-return and integration procedure can be summarized as follows:

- (i)

- given , , and the strain increment , compute the elastic trial stress from Equations (27) and (28) and evaluate the yield function

- (ii)

- if , accept the trial state and keep the internal variables unchanged;

- (iii)

- if , compute from Equation (31), update and , evaluate from Equation (30), and finally update the stress and internal variables using Equations (32) and (33).

This semi-implicit stress-return algorithm provides a stable and consistent numerical integration of the proposed damage–plasticity model.

3. Model Calibration and Validation

3.1. Model Calibration

In this section, the model’s performance is examined through triaxial simulations on three representative rocks: Marble, Sandstone, and Granite. Details of the calibration procedure, together with the corresponding simulation outcomes, are presented below.

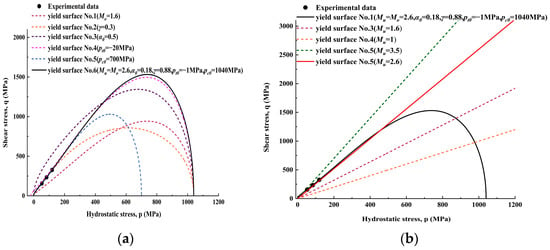

The parameters in the proposed model can be categorized according to their physical significance. The first set of parameters () are related to the initial and residual yield surfaces, which directly determine the shape and boundary of the yield surface in the – space. As illustrated in Figure 2a, increasing raises the overall strength, reducing flattens the curve, while increasing shifts it toward the right. The calibration of these parameters follows the methodology proposed in the Mukherjee M [37] study, in which the yield equation (Equation (6)) is iteratively fitted to the initial yield points in the p–q plane obtained from triaxial compression tests conducted under different confining pressures. Figure 2b further shows that governs the slope of the residual yield surface at complete damage (); a larger enhances residual strength and steepens the curve, whereas a smaller reduces residual strength and flattens it. In practical applications, is calibrated according to the method proposed in the Mukherjee M [37] study by fitting the residual strengths obtained from triaxial compression tests at different confining pressures and minimizing the fitting error.

Figure 2.

Effect of model parameters on the yield surface in the space: (a) Effect of parameters on the yield surface; (b) The influence of parameter on the residual yield surface.

In addition, the dilation parameter and the damage evolution parameters and govern the dilation behavior and the evolution of damage during plastic deformation. Specifically, is used to characterize the volumetric expansion behavior of rock. Following the methodology proposed in the Mukherjee M [37] study, it is calibrated by fitting the stress–strain curves and volumetric strain data obtained from compressive and tensile tests for each rock type. The parameters and describe the rate and extent of damage development; the associated coefficients and are calibrated by fitting the plastic-stage data from the stress–strain curves obtained under different confining-pressure conditions for each rock type. Finally, the elastic parameters, Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio characterize the mechanical response in the elastic stage and reflect the material’s resistance to elastic deformation; they are calibrated from the initial stress–strain curves and provide the basis for the subsequent nonlinear behavior of the model. As a reference for subsequent simulations, Table 1 provides , , and the fitted coefficients for the proposed model across the three rock types.

Table 1.

Simulation Parameters of Three Different Rocks.

3.2. Model Validation

The triaxial test datasets used for parameter calibration and validation in this section are taken from previously published monotonic triaxial compression tests reported in Refs. [38,39,40], covering Marble, Sandstone, and Granite under different confining-pressure conditions. In these studies, the specimens are nearly intact cylindrical rock samples prepared in accordance with standard rock-testing procedures, and the specimen sizes and aspect ratios are comparable. Since the original publications do not provide tabulated raw data, we use a standard digitization tool to extract the stress–strain curves from the published figures. For each rock type, a single unified set of model parameters is calibrated simultaneously over all available confining-pressure levels, rather than re-fitting the parameters for each individual test curve, which reduces the risk of overfitting specific datasets.

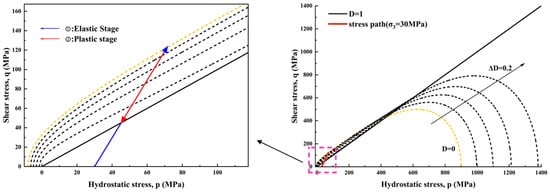

To validate the model’s capability to describe the mechanical behavior of brittle rocks, Marble was selected as the reference material. Following the standardized calibration procedure outlined earlier, model parameters were inverted and calibrated using publicly available triaxial compression test data (final parameters are listed in the “Marble” column of Table 1). Figure 3 presents the – stress path and corresponding stress–strain evolution under confining pressure (elastic stage in blue, plastic/damage softening stage in red). Specifically, the stress path initially ascends along a nearly linear elastic trajectory (blue), where material behavior is dominated by elastic stiffness; As the path approaches the yield/peak point, the specimen enters yield and reaches peak strength. Beyond the peak, the stress path deviates from the elastic trajectory, entering a softening process dominated by plastic deformation and damage accumulation (red), manifested as a decrease in shear stress accompanied by irreversible deformation until the residual strength point. The enlarged inset clearly illustrates these two segments: the blue arrow indicates the elastic rise from initial state to peak, while the red arrow marks the plastic damage and softening segment from peak to residual strength.

Figure 3.

Stress path and mechanical response of marble in triaxial compression test.

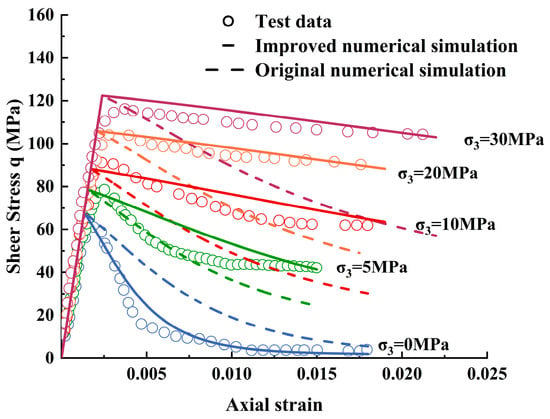

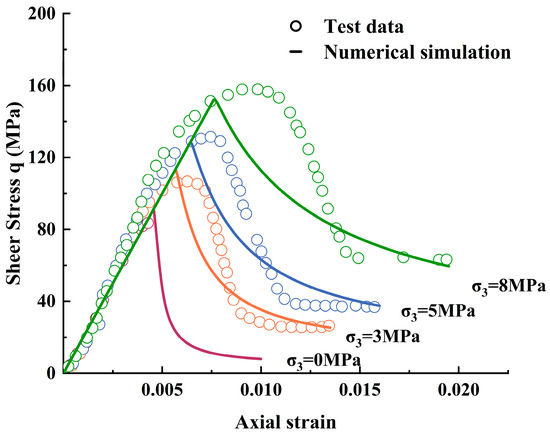

During calibration, the confining pressure σ3 was set to 0, 5, 10, 20 and 30 MPa, covering a typical range from low to medium–high confinement. Figure 4 compares the shear stress–axial strain curves obtained from tests (circles) with the predictions of the improved constitutive model (solid lines) and the original model (dashed lines). In the elastic stage, the linear ascending slopes of the two numerical models are almost identical and both agree well with the experimental data; near the peak, the differences between the two models in terms of the magnitude and location of the peak strength are not pronounced, and both are able to reproduce the peak characteristics of the experimental curves reasonably well. The major discrepancy between them is mainly observed in the post-peak stage, especially in the description of the softening process and the residual strength level. The original model often fails to accurately capture the stress-decay trend along the post-peak softening branch, leading to an excessively rapid drop of shear stress or a residual-strength plateau that is noticeably lower than the experimental results, and this deviation becomes more evident with increasing confining pressure. In contrast, the improved model closely follows the experimental curves along the entire softening branch, successfully capturing the softening rate, the decay pattern of the shear stress q, and the residual strength level, and it exhibits consistent performance under all confining pressures. These results indicate that, after introducing an enhanced coupling mechanism between the softening parameters and the confining pressure, the accuracy of the model in predicting post-peak softening and residual strength is significantly improved. The improved model can thus more realistically describe the continuous transition of dense marble from brittle failure to ductile/plastic flow, providing a more reliable theoretical basis for extending the model to different confining-pressure conditions and for deep engineering stability analyses.

Figure 4.

Shear stress–axial strain relationship of marble under different confining pressures [38].

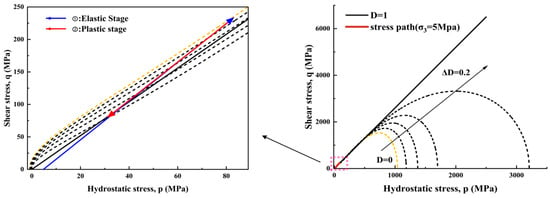

To validate the model’s applicability to the mechanical behavior of Sandstone under varying confining pressures, parameter calibration was performed at confining pressure levels of 0, 5, 10, 20, and 30 MPa, covering a typical range from low to medium–high confining pressures. Figure 5 displays the – stress path at an overburden pressure of 3 MPa, where the red curve represents the loading path. A clear distinction between two stages is made: the blue segment is associated with the elastic stage, while the red segment is associated with the plastic-damage softening stage. Specifically, the stress state initially increases monotonically along the blue elastic path, exhibiting an approximately linear response. Upon reaching the yield plane and approaching the peak point, the path transits into the red segment, entering a softening stage dominated by damage evolution and plastic deformation. At this point, the shear stress gradually decreases with increasing volumetric stress p until reaching the residual strength state.

Figure 5.

Stress path and mechanical response of sandstone in triaxial compression tests.

Figure 6 compares the stress–strain curves predicted by the model with experimental results reveals high consistency in the slope during the elastic stage, the location of peak stress, and the morphology of the post-peak softening segment. Particularly in the post-peak stage, the model accurately reproduces details such as the softening rate, stress decay trend, and residual strength plateau. The results demonstrate that the established softening parameter–confining pressure coupling mechanism faithfully reflects the progressive evolution of dense marble from brittle failure to ductile/plastic failure. This validates the model’s stability and universality under varying confining pressure conditions, providing a reliable theoretical foundation for deep rock mass stability analysis.

Figure 6.

Shear stress–axial strain relationship of sandstone under different confining pressures [39].

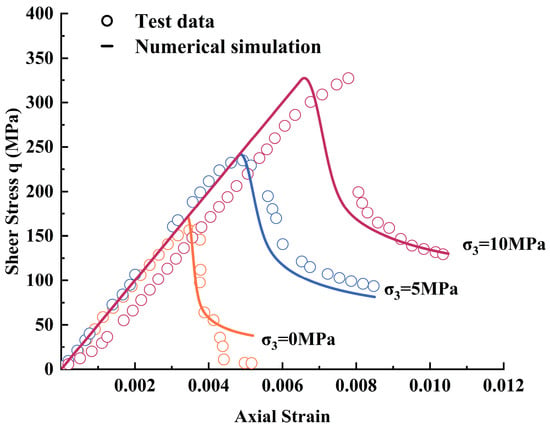

The validation process for Granite employs the same experimental protocol and parameter inversion procedure as Marble. Model parameter calibration was completed based on granite triaxial compression test data, with the results listed in the “Granite” column of Table 1: Simulation Parameters of Three Different Rocks. Figure 7 illustrates the – stress path corresponding to a confining pressure of 5 MPa. The red curve represents the loading path, with the inset Figure 7 visually distinguishing two stages of stress evolution: the blue segment corresponds to the elastic response phase, while the red segment signifies the post-yield plastic damage softening phase. Specifically, stress initially increases along the blue elastic path, characterizing linear reversible deformation. Upon reaching the yield plane and approaching the peak point, the material enters the red phase. Here, microcracks propagate continuously within the material, stiffness decreases, and shear stress gradually diminishes as volumetric stress increases, until residual strength stabilizes.

Figure 7.

Stress path and mechanical response of granite in triaxial compression tests.

Under confining pressures of 0, 5, and 10 MPa, the model-predicted curves were compared with experimental curves for Granite (see Figure 8). The results demonstrate good consistency between the two at all stages: the stress–strain growth rates in the elastic stage were nearly identical, and the predicted peak strength values agreed well with the measured results. During the post-peak softening stage, the model successfully reproduced the stress decay rate and the evolution characteristics of the residual strength plateau. Overall, the proposed model accurately captures the entire process of granite deformation—from elastic deformation, yielding, damage softening, to ultimate failure—under varying confining pressures, fully validating its applicability in high-brittle environments.

Figure 8.

Shear stress–axial strain relationship of granite under different confining pressures [40].

In summary, within the scope of the monotonic triaxial compression simulations considered in this study, the verification results for the three types of brittle rocks indicate that the proposed model can accurately reproduce their mechanical responses, providing preliminary evidence of its applicability and reliability for different brittle rock types under such loading conditions.

4. Sensitivity Analysis

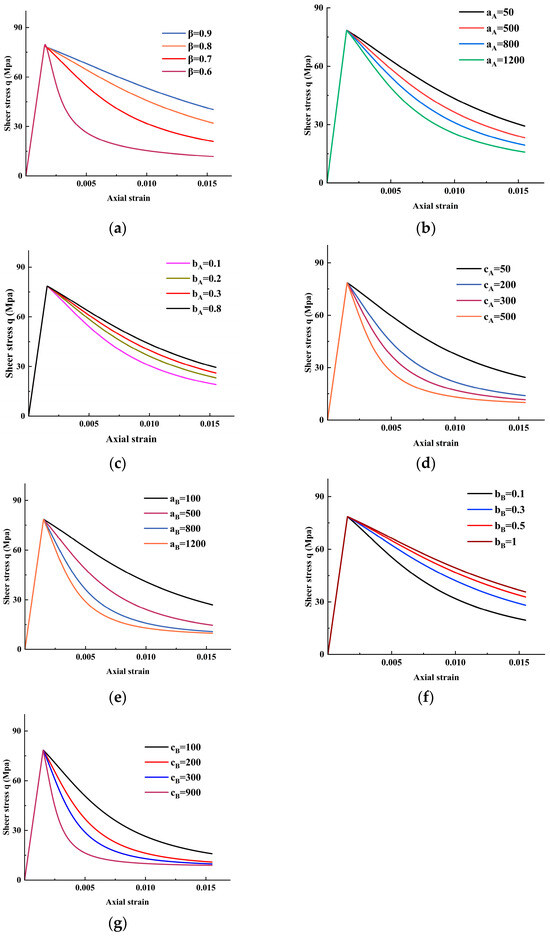

To investigate the influence of various model parameters on softening characteristics, this section conducts a sensitivity analysis based on the triaxial compression curve of marble under 5 MPa confining pressure. Using the model curve under baseline parameters as a reference, the effects of sequentially altering parameters , , , , . , and on the stress–strain relationship is examined. The results are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Sensitivity analysis of parameters: (a) expansion parameter , (b) , (c) , (d) , (e) , (f) , (g) .

As shown in Figure 9a, the parameter primarily governs the stress decay rate during the softening stage. Smaller values correspond to a stronger volumetric expansion effect, causing the material to undergo rapid stress relaxation after the peak and exhibiting distinct brittle softening characteristics. Conversely, larger values attenuate the expansion effect, delaying the softening process. This results in a more gradual decrease in shear stress and an increase in residual strength, reflecting more pronounced ductile behavior.

Figure 9b–d illustrate the effects of softening behavior on , and . determines the initial amplitude of ; its increase elevates ’s value under low confining pressure, leading to faster decay of post-peak shear stress and more pronounced softening (Figure 9b). reflects ’s sensitivity to confining pressure; a larger accelerates the decay of with , resulting in a steeper stress decline during the softening phase Figure 9c); while controls the residual level of ; increasing it leads to a more pronounced decline at the tail end of the stress curve and a reduction in residual strength (Figure 9d).

Similarly, Figure 9e–g illustrate the influence patterns of , and . on the softening stage. determines the baseline amplitude of ; its increase enhances the accumulation rate of plastic strain, thereby accelerating post-peak softening (Figure 9e); reflects the confining pressure sensitivity of . A larger weakens ’s influence under high confining pressure, resulting in a smoother softening process and enhanced ductility Figure 9f); determines the limit level of . As increases, the softening curve shifts downward overall, leading to a greater reduction in shear stress and a decrease in residual strength (Figure 9g).

In summary, , , and collectively govern the material’s softening behavior: primarily modulates volume expansion and brittle–ductile transition characteristics; and dominate the post-peak softening rate and residual strength level through plastic strain evolution. The parameters , , , . , and exhibit clear physical significance and controllability in their influence on and , validating the model’s rationality and robustness in describing confining pressure-related softening mechanisms.

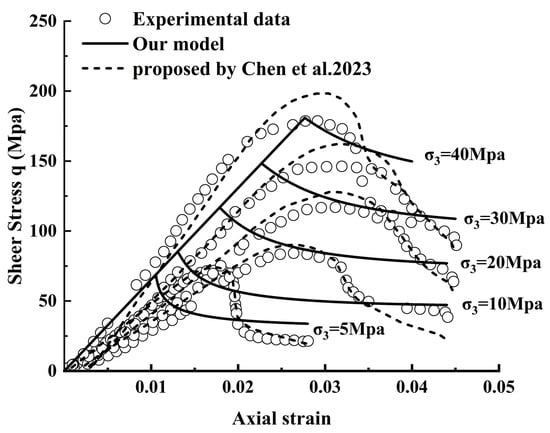

5. Comparison of Model Simulation Capabilities

To further validate the accuracy and reliability of the proposed model, the simulation results under different confining pressures were compared with experimental data and the computational results from the model proposed by Chen et al. [41] as shown in Figure 10 The solid line represents the prediction results of the model in this paper, while the dashed line indicates the prediction results of the model by Chen et al. [41]. To further clarify the performance of the proposed constitutive model under different confining pressures, it should be noted that the current formulation does not incorporate the dependence of elastic modulus on confining pressure. As a result, the elastic modulus remains constant during the fitting process, causing the initial elastic segment of the modeled curves to appear nearly linear. This simplification leads to a less accurate representation of the material’s nonlinear elastic response at the early deformation stage compared with the model proposed by Chen et al., especially under higher confining pressures. This limitation will be a key direction for future improvement in the constitutive model.

Figure 10.

Comparison of the fitting effects of Chen model [41].

Nevertheless, the proposed model demonstrates good consistency in predicting the peak strength across all confining pressure conditions. It should also be emphasized that the experimental curves under confining pressures of 20 MPa, 30 MPa, and 40 MPa do not show a clear residual strength plateau, whereas distinct residual stages are observed at 5 MPa and 10 MPa. For these cases with well-defined post-peak residual characteristics, the model is able to reasonably reproduce the softening behavior and the residual strength. In summary, although the current model has certain limitations in capturing the elastic stage, it still performs well in describing the peak response and the post-peak behavior when experimentally identifiable.

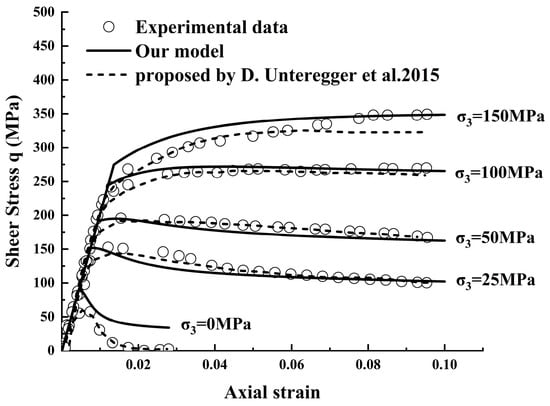

Figure 11 compares the proposed model (solid lines) with the model by D. Unteregger et al. [42] (dashed lines) against the experimental stress–strain curves under different confining pressures. Overall, both models are capable of reproducing the main features of the shear stress–axial strain response. At lower confining pressures, the model of D. Unteregger et al. [42] generally provides a slightly closer agreement with the experimental curves in the peak region, whereas the proposed model still captures the overall trend but shows a somewhat larger deviation near the peak and the immediate post-peak segment.

Figure 11.

Comparison of the fitting effects of D. Unteregger model [42].

At higher confining pressures, the behavior of the two models differs in another way. The proposed model tends to slightly overpredict the peak shear stress, but it reproduces the residual strength level and the gradual post-peak decay of stress more consistently with the test data. In contrast, the model of D. Unteregger et al. [42] yields a comparable peak response, while its predicted residual stress is lower than the measured values and the post-peak curve appears relatively flatter.

These observations indicate that the proposed model does not outperform the reference model at all confining pressures. Its main advantage lies in the description of the post-peak and residual behavior under higher confining pressures, where a realistic representation of the remaining load-carrying capacity is of particular engineering interest. In this sense, the confining pressure-dependent softening formulation improves the adaptability of the proposed model for simulations focusing on the residual strength and long-term deformation of rock.

6. Discussion

The proposed damage-based constitutive model effectively captures the evolution of rock mechanical behavior under triaxial compression across a range of confining pressures, and reproduces the progressive transition from brittle post-peak stress drop to more ductile deformation as confinement increases. This improvement is particularly evident in the post-peak regime: with increasing confining pressure, both the magnitude of stress drop and the softening rate decrease, which is consistent with the experimental observation that higher confinement mitigates strain softening and promotes more stable deformation. In the present formulation, the parameters , , and jointly govern the post-peak softening process: mainly affects the dilation-related volumetric response, whereas and regulate the evolution of plastic deformation and the associated degradation of load-bearing capacity. By introducing the confining pressure-dependent expressions and , the model overcomes the limitation of previous formulations that used fixed softening parameters. The exponential decay provides a compact description of the progressive attenuation of softening with increasing confinement, enabling the model to reproduce both the pronounced post-peak stress drop at low confining pressure and the smoother post-peak response at higher confining pressure. Compared with the original model proposed by Mukherjee et al. [37], the present approach shows closer agreement with the experimental stress–strain responses across a wider range of confining pressures, particularly in capturing the confinement dependence of the post-peak branch and the residual strength level.

Despite these favorable results, the present study still has several limitations. First, the calibration and validation are restricted to monotonic triaxial compression tests on three types of intact brittle rocks; other loading paths, such as unloading–reloading, cyclic loading, true triaxial stress states, tensile conditions, and dynamic loading, have not yet been examined. Second, the model employs a scalar isotropic damage variable and a phenomenological description of softening, which may not fully capture anisotropic damage, strain localization, and complex fracture patterns in highly heterogeneous rock masses. Third, all analyses are conducted under isothermal, rate-independent conditions, so temperature effects, time-dependent phenomena (e.g., creep and long-term degradation), and fluid–rock interactions are neglected, even though they can significantly influence rock behavior in deep geological environments. In addition, the parameters are calibrated against a single set of laboratory datasets for each rock type, and independent datasets or field-scale observations have not yet been used for further validation.

Future research will therefore focus on extending the proposed framework along several directions. On the constitutive side, the model will be generalized to incorporate rate- and time-dependent effects, anisotropic damage, and explicit thermo-hydro-mechanical coupling, so as to describe the long-term behavior of rocks under complex environmental conditions. On the validation side, more comprehensive assessments under different stress paths and boundary conditions—including true triaxial tests, cyclic loading, and unloading–reloading paths—as well as comparisons with independent laboratory datasets and large-scale numerical simulations or field case histories will be pursued. These developments are expected to further clarify the range of applicability of the model and enhance its usefulness for the stability analysis and design of deep underground engineering structures.

7. Conclusions

This paper proposes an improved damage constitutive model that incorporates pressure-dependent softening parameters within the Mukherjee M model framework, achieving a unified description of the transition from brittle to plastic behavior in rock. This model overcomes the limitation of fixed softening parameters in traditional damage constitutive models, enabling dynamic reflection of confining pressure’s control over rock softening behavior. Validation against multiple triaxial compression test data demonstrates higher accuracy and applicability in key characteristics such as peak strength, softening rate, and residual strength. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- The improved model systematically characterizes the entire response process of rock from the elastic stage to the post-peak softening stage, accurately reproducing the mechanical evolution from brittle failure to plastic flow under varying confining pressures.

- (2)

- The behavior during the softening stage is primarily governed by the parameters , , and . Among these, is the expansion parameter, which dominates the coupling mechanism between volume expansion and shear softening; and are plastic strain control parameters, whose variation with confining pressure is determined by (, , and ) and (, , and ), respectively. Parameter analysis reveals:

Smaller values intensify brittle softening, accelerating stress decay; as confining pressure increases, the values of and gradually decrease, slowing the material’s softening rate and exhibiting more pronounced ductile behavior.

- (3)

- This model establishes an intrinsic relationship between confining pressure, softening parameters, and mechanical response within a unified framework. It provides a rational explanation for the formation mechanisms of variations in rock strength and ductility under different confining pressure conditions, offering a new theoretical tool for analyzing the stability of deep engineering rock masses.

Author Contributions

W.H.: Writing—Original Draft, Investigation, Funding acquisition; J.R.: Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Investigation; P.W.: Methodology, Writing—Review & Editing, Funding acquisition. B.Y.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Review & Editing; J.L.: Methodology, Formal analysis. H.Z.: Writing—Review & Editing. R.C.: Writing—Review & Editing. H.L.: Writing—Review & Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52578390), Chongqing Municipal Education Commission Science and Technology Research Project (Grant No. KJZD-K202401506), Open Research Fund of State Key Laboratory of Geomechanics and Geotechnical Engineering Safety (Grant No. SKLGGES-024032), Opening Fund of State Key Laboratory of Geohazard Prevention and Geoenvironment Protection (Chengdu University of Technology) (Grant No. SKLGP2025K028), Science and Technology Innovation Project Fund of Chongqing University of Science and Technology, YKJCX2420615, and Open Fund of Chongqing Key Laboratory of Energy Engineering Mechanics & Disaster Prevention and Reduction (Grant No. EEMDPM2021102).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality considerations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Du, X.; Xue, J.; Shi, Y.; Cao, C.-R.; Shu, C.-M.; Li, K.; Ma, Q.; Zhan, K.; Chen, Z.; Wang, S. Triaxial mechanical behaviour and energy conversion characteristics of deep coal bodies under confining pressure. Energy 2022, 266, 126443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Gu, Q.; Wu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, S.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, R. Effects of confining pressure on acoustic emission and failure characteristics of sandstone. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2021, 31, 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Li, C.; He, Z.; Li, C.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Gao, M.; Gao, F. Experimental study on rock mechanical behavior retaining the in situ geological conditions at different depths. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Géoméch. Abstr. 2021, 138, 104548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-Q.; Huang, Y.-H. An experimental study on deformation and failure mechanical behavior of granite containing a single fissure under different confining pressures. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.H.; Tham, L.G.; Yeung, M.R.; Xie, H. Confinement effects for damage and failure of brittle rocks. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2006, 43, 1262–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Gao, M.; Fu, C.; Lu, Y. Mechanical behavior of brittle-ductile transition in rocks at different depths. Meitan Xuebao/J. China Coal Soc. 2021, 46, 701–715. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Chen, H.; Yuan, S.; Zhu, Q. Experimental investigation and micromechanical modeling of the brittle-ductile transition behaviors in low-porosity sandstone. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2020, 179, 105654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wu, S.; Guo, P.; Zhang, S. Mechanical Deformation, Acoustic Emission Characteristics, and Microcrack Development in Porous Sandstone During the Brittle–Ductile Transition. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2023, 56, 9099–9120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, M.; Sarout, J.; Poulet, T.; Dautriat, J.; Veveakis, M. The Brittle–Ductile Transition and the Formation of Compaction Bands in the Savonnières Limestone: Impact of the Stress and Pore Fluid. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2022, 55, 6541–6553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsikrikis, A.; Papaliangas, T.; Marinos, V. Brittle-Ductile Transition and Hoek–Brown mi Constant of Low-Porosity Carbonate Rocks. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2021, 40, 1833–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-C.; Lin, Z.-N.; Dong, B.; Guo, R.-X. Triaxial Compression Testing at Constant and Reducing Confining Pressure for the Mechanical Characterization of a Specific Type of Sandstone. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2021, 54, 1999–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Hu, Y. Experimental study on mechanical behavior, permeability, and damage characteristics of Jurassic sandstone under varying stress paths. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2021, 80, 4423–4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Zou, Z.; Guo, S.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, X.; Luo, T. Mechanical behavior and damage constitutive model of granodiorite in a deep buried tunnel. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2022, 81, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, X.P.; Luo, Y.; Liu, T.T.; Liu, X.Q.; Qu, D.X. Characterization and mesosimulation of the triaxial compression failure of rock-like materials. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 570, 22030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Chen, X.; Cui, Z.; Jin, C.; Shen, C.; Su, Z.; Li, S.; Liang, J. Study on Microcracks Propagation of Shale Under Tensile and Shear Loading at Different Confining Pressures. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, R. Damage mechanism of rock induced by microcrack evolution: A multi-dimensional perspective. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2024, 309, 110420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.-D.; Zhu, M.-L. Timely spread characteristics of micro- and meso-scale fractures based on SEM experiment. Environ. Earth Sci. 2020, 79, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, S.; Khamehchiyan, M.; Taheri, A.; Nikudel, M.R.; Zalooli, A. Microcracking Behavior of Gabbro During Monotonic and Cyclic Loading. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2021, 54, 2441–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Cui, Z.; Peng, R.; Si, K. Numerical Simulation and Evaluation on Continuum Damage Models of Rocks. Energies 2022, 15, 6806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.-Y.; Wang, Z.; Ma, D.; Zhang, J.-W.; Wu, G.; Wen, S.; Zha, M.; Wu, L. A Continuous Damage Statistical Constitutive Model for Sandstone and Mudstone Based on Triaxial Compression Tests. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2022, 55, 4963–4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen-Kettle, L.; Sarout, J. Assessment of Tensorial and Scalar Damage Models for an Isotropic Thermally Cracked Rock Under Confining Pressure Using Experimental Data: Continuum Damage Mechanics Versus Effective Medium Theory. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2021, 55, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z.; Wang, S.; Hashmi, M.Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, C. Causes, characterization, damage models, and constitutive modes for rock damage analysis: A review. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.T.; Nguyen, T.V.; Nguyen, N.T.; Nguyen, G.D.; Karakus, M.; Bui, H.H. A Simple 3D Damage-Plasticity Model with Energy-Based Regularisation in SPH for Modelling Fractured Quasi-brittle Rocks. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 58, 9937–9964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-Q.; Hu, B.; Xu, P. Study on the damage-softening constitutive model of rock and experimental verification. Acta Mech. Sin. 2019, 35, 786–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K. Constitutive model of rock triaxial damage based on the rock strength statistics. Int. J. Damage Mech. 2020, 29, 1487–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-N.; Wang, L.-C.; Zhou, H.-Z. An experimental investigation and mechanical modeling of the combined action of confining stress and plastic strain in a rock mass. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2022, 81, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Tang, H.; Ning, Y.; Xia, D. A damage mechanics based on the constitutive model for strain-softening rocks. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2019, 216, 106521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, H.; Wang, Y.; Xie, S.; Zhao, Y.; Yong, W. Statistical damage constitutive model based on the Hoek–Brown criterion. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2021, 21, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Bi, J.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Zhong, X. Triaxial compression experiment and damage constitutive model of microbially modified strongly weathered phyllite. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 393, 131962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Zhao, K.; Xiao, W.; Nie, Q.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, J. Deformation failure and damage evolution law of weathered granite under triaxial compression. Nondestruct. Test. Eval. 2024, 39, 1900–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Tan, X.; Zhang, C.; He, M. Constitutive model to simulate full deformation and failure process for rocks considering initial compression and residual strength behaviors. Can. Geotech. J. 2019, 56, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; She, C.; Shang, P. Evolution models of the strength parameters and shear dilation angle of rocks considering the plastic internal variable defined by a confining pressure function. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2021, 80, 2925–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.T.; Nguyen, T.V.; Karakus, M.; Nguyen, G.D.; Bui, H.H. SPH-based modelling of the entire rock caving process: Insights into failure mechanisms. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Géoméch. Abstr. 2025, 194, 106228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; He, B.; Hou, X.; Li, J.; Liu, L. Stress–Energy Mechanism for Rock Failure Evolution Based on Damage Mechanics in Hard Rock. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2019, 53, 1021–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; He, C.; Ma, G.; Xu, G.; Ma, C. Energy Damage Evolution Mechanism of Rock and Its Application to Brittleness Evaluation. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2018, 52, 1265–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.T.; Nguyen, G.D.; Karakus, M.; Bui, H.H.; Phan, D.G. Controlling behaviour of constitutive models for rocks using energy dissipations. Int. J. Plast. 2024, 184, 104196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, M.; Nguyen, G.D.; Mir, A.; Bui, H.H.; Shen, L.; El-Zein, A.; Maggi, F. Capturing pressure- and rate-dependent behaviour of rocks using a new dam-age-plasticity model. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2017, 110, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, G.; Hedayat, A.; Kim, E.; Labrie, D. Post-yield Strength and Dilatancy Evolution Across the Brittle–Ductile Transition in Indiana Limestone. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2017, 50, 1691–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yumlu, M.; Ozbay, M. A study of the behaviour of brittle rocks under plane strain and triaxial loading conditions. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Géoméch. Abstr. 1995, 32, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Ge, X.; Li, C. Method for Determining Hoek-Brown Softening Parameters of Rocks Based on Triaxial Compression Tests. China Rural Water Hydropower 2011, 8, 117–120. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Tong, L.; Geng, D.; Dong, Z.; Yang, P. Elastoplastic Damage Behavior of Rocks: A Case Study of Sandstone and Salt Rock. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2023, 56, 5621–5634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unteregger, D.; Fuchs, B.; Hofstetter, G. A damage plasticity model for different types of intact rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Géoméch. Abstr. 2015, 80, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.