Abstract

Ammonia is a carbon-free energy carrier and a natural refrigerant with a high energy density. However, its high toxicity raises significant safety concerns in confined environments. To address this issue, this study developed a hybrid ammonia capture material, water-loaded zeolite 13X (WLZ), which combines the structural stability of zeolites with a strong chemical affinity for water. WLZ was synthesized using an ethanol-water impregnation method. A series of experiments were conducted under simulated leak conditions in pure ammonia and air. WLZ-75, containing 75% water loading, demonstrated high ammonia capture efficiency (over 90% removal at 1000 ppm), stable low-temperature regeneration below 90 °C over repeated cycles, and more than 95% retention after 10 capture/regeneration cycles. Chamber-scale tests confirmed not only its high removal performance but also exothermic behavior, potentially enabling thermal-based leak detection. These results demonstrate that WLZ is a highly regenerable and thermally responsive material suitable for ammonia safety management in refrigeration, fuel systems, and sealed environments.

1. Introduction

Recently, the urgency to address climate change and achieve net-zero carbon goals has increased across the global industrial and transportation sectors. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions in maritime transport has become particularly important. Shipping accounts for over 80% of global trade by volume, and the heavy fuel oil used by most ships emits significant amounts of CO2, SOX, NOX, and other pollutants [1]. In response, ammonia has attracted significant interest as a carbon-free alternative fuel due to its zero-carbon combustion characteristics, high hydrogen density, and compatibility with existing storage and transport infrastructure. Recent studies have highlighted ammonia’s suitability as a next-generation marine fuel, its applicability in gas turbine and dual-fuel power generation systems, and its long-standing role as an efficient natural refrigerant (R717) in industrial and commercial cooling applications [2,3,4,5]. In this context, ammonia has emerged as a promising carbon-free energy carrier and working fluid. Because ammonia does not emit carbon dioxide when burned, it is becoming a leading decarbonization candidate for the shipping, power generation, and refrigeration sectors [6,7].

Refrigeration and air conditioning systems consume approximately 17% of global electricity, significantly contributing to indirect carbon emissions [8]. Utilizing low-carbon or natural refrigerants in these systems not only reduces environmental impact but also enhances thermodynamic efficiency and may enable system miniaturization. Among the natural refrigerants, ammonia is particularly attractive due to its excellent thermophysical properties, including low ozone depletion potential, low global warming potential, high latent heat, and superior heat transfer coefficient [9,10,11,12]. These advantages make ammonia a highly effective working fluid for both stationary and mobile refrigeration systems. In particular, its high energy efficiency and favorable thermophysical properties enable compact system design, which is especially advantageous for marine applications where space constraints and efficient thermal management are critical requirements [13].

Despite its environmental and performance advantages, the widespread adoption of ammonia is constrained by several technical and safety concerns. Its high toxicity and corrosiveness pose significant risks in the event of a leak, and its incompatibility with certain metals requires careful material selection [14]. According to occupational safety regulations and guidelines, including NIOSH and CAL/OSHA standards, the permissible or recommended exposure limits for ammonia are as low as 25 ppm, highlighting the potential risks of ammonia leakage in confined environments [15]. Moreover, key enabling technologies—such as compact system design, advanced leak detection, and real-time recovery and recycling mechanisms—remain underdeveloped. The regulatory framework and certification standards for ammonia-based small- and medium-scale systems also lag behind those for conventional refrigerants [16]. As a result, ammonia is currently used primarily in large-scale industrial systems, with limited application in residential or transportation-related contexts, such as heat pumps and small-scale refrigeration units. To address these challenges, recent research has focused on integrated approaches to enhance the safety and feasibility of ammonia-based systems.

The feasibility of metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) and ammonia working pairs for solid-sorption thermal energy storage has been demonstrated, exhibiting characteristic ammonia sorption behavior and stable performance over repeated cycles [17]. Given the inherently high surface area and adsorption capacity of MOFs, a CTL-based approach was introduced as a rapid and efficient alternative to BET for evaluating their surface areas and related sorption behavior [18]. Additionally, a cooperative ammonia insertion mechanism into metal-carboxylate bonds has been reported, demonstrating reversible capture and enhanced stability under concentrated ammonia environments [19]. Despite these advantages, many MOFs remain sensitive to humidity and prone to structural degradation, motivating the search for more robust alternatives. Accordingly, the present study focuses on zeolite-based materials as a model system for investigating water-mediated ammonia capture under humid conditions, and MOFs are discussed only as relevant background rather than as experimental comparators.

In this context, zeolite 13X was selected over smaller-pore zeolites such as 4A or 5A because of its larger pore size and higher accessible surface area, which make it a more suitable platform for investigating water-mediated ammonia capture under humid conditions. Zeolites, characterized by their chemically and thermally stable microporous networks, exhibit strong and reversible interactions with ammonia. Recently, protonated water clusters in HZSM-5 zeolites were characterized at the molecular level, providing insights into how confined water influences interaction behavior within the pores under humid conditions [20]. The effect of framework aluminum T-site distribution on the adsorption heats of ammonia and water in MOR, MFI, and FAU zeolites has been systematically evaluated [21]. Furthermore, large-pore hydrophobic zeolites have been shown to promote ammonia clustering and enable cost-effective ammonia separation due to their favorable sorption energetics and framework stability [22].

Recent reviews have highlighted the importance of regenerable solid sorbents and the development of low-energy ammonia capture and storage strategies for next-generation compact systems [23]. In this context, an ammonia-based sorption thermal battery capable of operating with a low-temperature heat source of approximately 80 °C has been demonstrated, underscoring the practical feasibility of regeneration driven by low-grade waste heat [24]. Next-generation sorbents tailored for ammonia—such as MOFs, salt-confined composites, and graphene aerogels—enable highly reversible sorption and low-temperature regeneration, offering a promising approach for decarbonized heating applications [25]. Accordingly, sensing technologies have advanced in parallel with adsorbent research.

Sensor technologies capable of detecting ammonia at parts-per-million (ppm) levels have also advanced significantly. Light-activated hybrid sensors based on porphyrin-coated V2O5 nanosheets have demonstrated highly sensitive and selective ammonia detection at room temperature [26]. Additionally, spray-coated PANI-polysulfonic acid composite films have been developed as optical ammonia sensors, where variations in polymer chain structure and cation treatment strongly influence film morphology, thereby enhancing low ppm ammonia detection performance [27]. These interdisciplinary efforts highlight the increasing demand for multifunctional materials and systems that simultaneously ensure safety, efficiency, and compliance with environmental regulations. As the use of ammonia expands across various industrial sectors, there is a growing need for adsorbent materials that can be regenerated at low temperature using low-grade waste heat while maintaining stable performance under humid conditions. Such materials are essential for enabling compact and distributed ammonia systems with enhanced environmental safety.

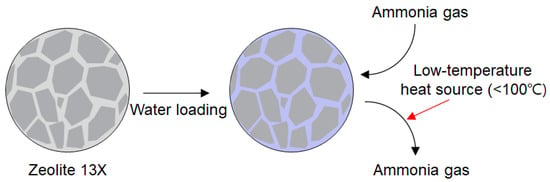

This study aims to develop a regenerable capture material that enables both efficient capture and passive thermal detection of leaked ammonia under a confined, low-temperature condition. By coupling water-mediated ammonia uptake with the intrinsic thermal stability of zeolite 13X, we propose a hybrid material that facilitates reversible adsorption, efficient regeneration, and passive leak detection through an exothermic response. Figure 1 illustrates the concept of water-loaded zeolite 13X, enabling reversible low-temperature ammonia capture. Although previous work has demonstrated that water-loaded zeolite 13X can operate using low-grade heat sources based on the ammonia-water absorption mechanism [28], these studies have primarily focused on large-scale industrial systems. In contrast, this work targets the safe deployment of ammonia in small- and medium-scale applications such as residential heat pumps and compact refrigeration units. By addressing limitations in capture efficiency, regeneration temperature, and leak detectability, this study seeks to establish a practical materials framework that supports the wider adoption of ammonia in emerging decarbonization technologies.

Figure 1.

Concept of water-loaded zeolite 13X enabling reversible low-temperature ammonia capture.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Zeolite 13X (purity ≥ 99.5%, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was selected as a reference material, which is well known for its strong affinity for both water and ammonia molecules. Deionized water (purity ≥ 99.5%, analytical grade, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and absolute ethanol (≥99.9%, Daejung Chemicals, Siheung, Republic of Korea) were used to prepare the solvent mixture for the impregnation process. High-purity ammonia gas (purity ≥ 99.999%, Seonggang Gas, Gimpo-si, Republic of Korea) was used throughout the ammonia capture/regeneration characterization experiments.

2.2. Preparation of Water-Loaded Zeolite 13X

Zeolite 13X was activated (degassed) under vacuum at 180 °C for 12 h to remove physisorbed water and any impurities introduced upon air exposure. The activated solid was then impregnated with an ethanol-water mixture at a mass ratio of 2:1 (solution: zeolite 13X). Ethanol was used as a co-solvent to improve wetting of the zeolite surface and to reduce surface tension during impregnation, thereby suppressing particle agglomeration and enabling more uniform water distribution within the zeolite matrix. Four solvent compositions were used, containing 25, 50, 75, or 100% water relative to the ethanol-water mixture. Water-loading levels were selected in a stepwise manner (25%, 50%, 75%, and 100%) to systematically investigate the effect of increasing water content on ammonia capture behavior. This approach enabled the identification of representative low, intermediate, high, and fully water-saturated regimes without unnecessary subdivision of the parameter space. After impregnation, the samples were placed in an open, temperature controlled chamber at 80 °C for 24 h to desorb ethanol, leaving only water and zeolite 13X. The resulting material is referred to as water-loaded zeolite 13X. Unless stated otherwise, the concentration of water-loaded zeolite 13X reported in the results refers to the water fraction in the impregnation solvent. In this work, water-loaded zeolite 13X is hereafter abbreviated as WLZ, and the numerical value following “WLZ” indicates the water fraction in the impregnation solvent used during the preparation process.

2.3. Characterizations

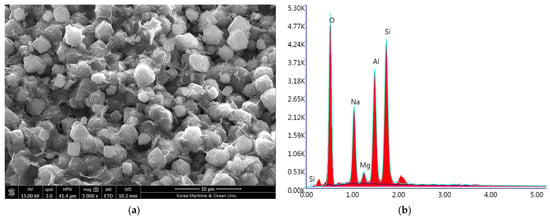

The physical and chemical properties of the prepared adsorbents were characterized using several analytical techniques. The surface morphology of the samples was investigated using a field-emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, SU-5000, HITACHI, Tokyo, Japan). Before imaging, each sample was sputter-coated with a thin layer of platinum (Pt) at 15 mA for 60 s to avoid charging effects, as the material does not contain elements such as Pt. The Pt coating was applied only to suppress charging effects during SEM observation and was sufficiently thin. During EDS analysis, the Pt signal was excluded from quantitative interpretation, and elemental analysis focused on the characteristic peaks of Si, Al, Na, and O. The magnification was adjusted according to the average particle size of each specimen. The elemental composition was analyzed using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) integrated with an FE-SEM system (AZtecLive Ultim Max40, Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK). Three measurements were performed for each material, and the average atomic and weight percentages were calculated based on the elemental mapping over the selected area. N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms were measured using a TriStar II 3030 (Micromeritics Corp., Norcross, GA, USA) to evaluate the specific surface area. All samples were vacuum-degassed at 180 °C for 12 h prior to analysis. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed using a NEXTA STA200 (HITACHI, Tokyo, Japan), ramping the temperature up to 500 °C at a rate of 20 °C/min in a nitrogen atmosphere to evaluate thermal stability and mass loss characteristics.

2.4. Ammonia Capture Capacity

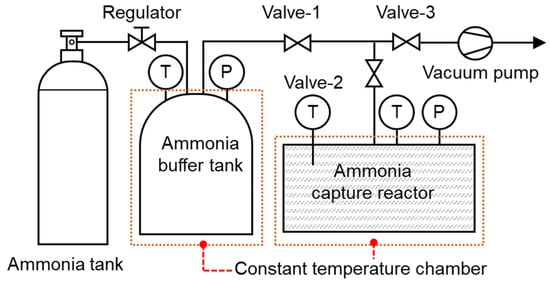

Figure 2 presents a schematic of the apparatus used to estimate the ammonia capture capacity. A 3.0 g sample of the ammonia capture material was placed into the capture reactor, which was then connected to the gas manifold. With only the valve at the capture reactor closed, the manifold lines and the ammonia reservoir were evacuated for 1 h to remove residual gases and impurities. Subsequently, all valves were closed, and anhydrous ammonia was introduced from a cylinder through a two-stage regulator to pressurize the reservoir to 2 bar. The entire assembly was maintained at 25 °C in a temperature-controlled chamber.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the apparatus used to estimate the ammonia capture capacity.

For each run, the top valve of the capture reactor and the upstream valve of the reservoir were opened simultaneously, allowing ammonia to expand into the reactor and contact the sample. As capture proceeded, the system pressure decreased. The experiment continued until the rate of pressure change dropped below 0.01 bar per hour, indicating that the system had reached a quasi-equilibrium state. The ammonia capture capacity (CC) was calculated from the pressure difference between the beginning and end of the run using the gas-phase material balance:

where P0 and Pf are the initial and final pressures, V is the gas-phase volume, T is temperature, m is the mass of the capture material, R is the gas constant, and Z is the compressibility factor.

After completing the ammonia capture, all valves were opened, and the capture reactor was heated to the specified regeneration temperature to release the captured ammonia and regenerate the capture material. Once the regeneration temperature was reached, it was maintained for 10 min. The reactor was then cooled back to 25 °C, and the capture experiment was repeated under identical conditions. The regeneration ratio (r) was defined as the ammonia capture capacity retained after regeneration relative to the initial capture capacity and was calculated as follows.

where CCinitial is the ammonia capture capacity during the first run, and CCregen is the capture capacity measured after regeneration. Table 1 presents the experiment specifications used to estimate the ammonia capture capacity.

Table 1.

Experiment specifications used to estimate the ammonia capture capacity.

2.5. Ammonia Capture in Air

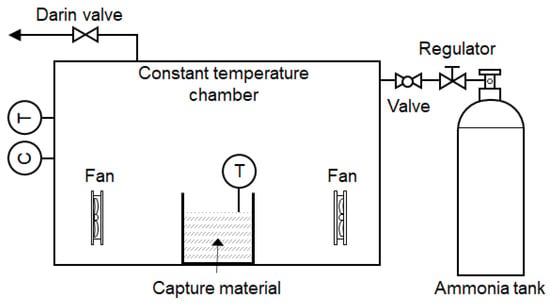

Figure 3 presents a schematic of the apparatus used to estimate ammonia capture in air. To simulate an accidental ammonia release, the performance of the capture material was evaluated in a 1.0 m3 (1 m × 1 m × 1 m) acrylic chamber. The chamber atmosphere was conditioned to 25 °C and 65% relative humidity. A mixing fan operated continuously to ensure a well-mixed volume and minimize concentration gradients. Ammonia gas was injected until the chamber concentration stabilized at 1000 ppm before exposing the capture material. For each run, the capture material was placed in a glass beaker inside the chamber and initially isolated from the chamber air by a closed damper. Once the ammonia concentration stabilized, the damper was opened to expose the capture material to the chamber air, initiating capture. The ammonia concentration in the chamber air was monitored continuously, and the temperatures of both the capture material bed and the chamber air were recorded throughout the test.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the apparatus used to estimate the ammonia capture in air.

Assuming a well-mixed, isothermal, and approximately isobaric closed chamber, the amount of ammonia captured by time was determined from the change in gas-phase concentration. The isothermal assumption applies to the bulk chamber atmosphere rather than to localized temperature variations at the adsorbent surface. Due to the relatively large chamber volume, active air mixing, and heat dissipation to the chamber walls, the bulk gas temperature remained approximately constant during the experiments.

where C0 and Cf are the initial and final ammonia concentration in the chamber, Pair is the pressure in chamber, V is the chamber volume, R is the gas constant. Tair is the temperature of chamber air. The corresponding ammonia capture capacity in chamber (CCchamber) is

where Mammonia is ammonia molar mass and mcm is the mass of the capture material mass. Table 2 presents the experiment specifications used to estimate the ammonia capture in air.

Table 2.

Experiment specifications used to estimate the ammonia capture in air.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Ammonia Capture Material Characteristics

Ammonia is a toxic gas with very low permissible exposure limits in confined environments [29]. Physical adsorbents, such as zeolites, are advantageous for capturing high concentrations of ammonia due to their high surface area and microporous structure; however, their adsorption capacity decreases significantly at low concentrations [30]. This limitation is critical in situations where the early removal of low-concentration leaks is necessary to prevent accumulation and reduce exposure risks. In contrast, chemically functionalized adsorbents interact more strongly with ammonia through acid–base or covalent bonding mechanisms, enabling effective capture even at low concentrations. Nevertheless, regenerating these materials typically requires high-temperature heat treatment to break the strong chemical bonds, posing challenges for energy-efficient operation [31].

To address these limitations, this study explored a hybrid approach capable of low-temperature regeneration (below 100 °C) while maintaining efficient ammonia capture. For this purpose, WLZ was utilized. Zeolite 13X was selected due to its large surface area, thermal stability, and well-defined microporous structure [32]. Figure 4 presents the SEM image and EDS results of the zeolite 13X used in this study. The particles exhibited a spherical shape with a relatively uniform microstructure. EDS analysis confirmed the presence of silicon (Si), aluminum (Al), oxygen (O), and sodium (Na), consistent with the typical elemental composition of synthetic faujasite-type zeolites [33].

Figure 4.

(a) SEM image and (b) EDS result of the zeolite 13X.

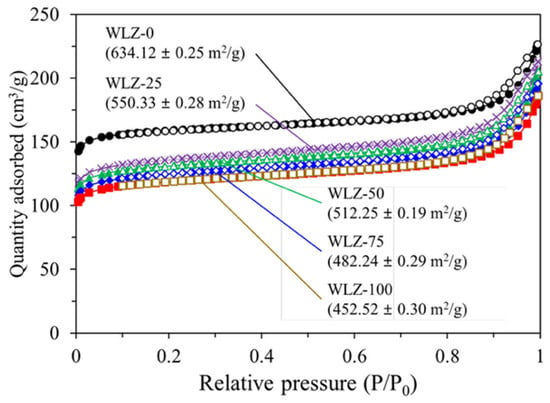

Figure 5 shows the N2 adsorption curves of zeolite 13X at different water loading concentrations. All samples exhibited a Type I isotherm, indicating microporous adsorption behavior. However, the adsorption capacity decreased as moisture content increased. This downward shift in the isotherm is attributed to partial pore blockage or water molecules occupying adsorption sites, which reduces the accessible surface area and pore volume available for nitrogen adsorption. The BET specific surface area, derived from the N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms, decreased with increasing water loading—from 634.12 m2/g for WLZ-0 to 550.33, 512.25, 482.24, and 452.52 m2/g for WLZ-25, WLZ-50, WLZ-75, and WLZ-100, respectively. This quantitative trend is consistent with the downward shift observed in the N2 adsorption isotherms shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

N2 adsorption curves of zeolite 13X at different water loading concentrations. Different symbols and colors represent different water loading ratios (WLZ-0, WLZ-25, WLZ-50, WLZ-75 and WLZ-100).

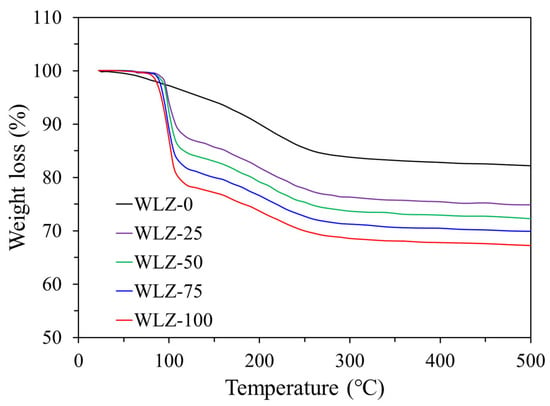

Figure 6 presents the TGA curves of zeolite 13X at different water loading concentrations. The dry sample (WLZ-0) exhibited minimal mass loss below 100 °C, attributed to the desorption of trace moisture and impurities, followed by a stable mass profile characteristic of zeolite 13X. In contrast, the moist samples (WLZ-25, WLZ-50, WLZ-75, and WLZ-100) showed rapid mass loss just above 100 °C, corresponding to the evaporation of physically bound moisture. The magnitude of this mass loss increased with higher moisture content.

Figure 6.

TGA curves of zeolite 13X at different water loading concentrations.

These results align with expected physical phenomena, where increased water content leads to greater volatility and mass loss upon heating. The mass loss observed around 100 °C in samples WLZ-25 to WLZ-100 was approximately 7–11%, corresponding to the desorption of physically trapped moisture. It is noteworthy that this phenomenon did not result in abrupt mass loss, indicative of skeletal structural decomposition, over this temperature range. This confirms that the observed behavior reflects normal moisture desorption, not structural instability of the zeolite 13X. Notably, the WLZ samples demonstrated thermal instability at temperatures above 100 °C but retained structural integrity and operational stability below this threshold. This behavior is consistent with the intended low-temperature application of this study.

Importantly, the observed mass loss is associated with the removal of physically confined water and does not indicate modification of the zeolite framework chemistry. Under typical water-loading conditions, the Si/Al ratio of zeolite 13X is not expected to be significantly altered, as water molecules primarily interact with the zeolite through reversible confinement within the micropores rather than framework modification [34]. Instead, water is physically confined within the micropores, leading to a reduction in accessible pore volume and surface area without altering the intrinsic pore size distribution. These effects are reversible upon regeneration, as evidenced by the recovery of adsorption performance.

3.2. Ammonia Capture and Regeneration

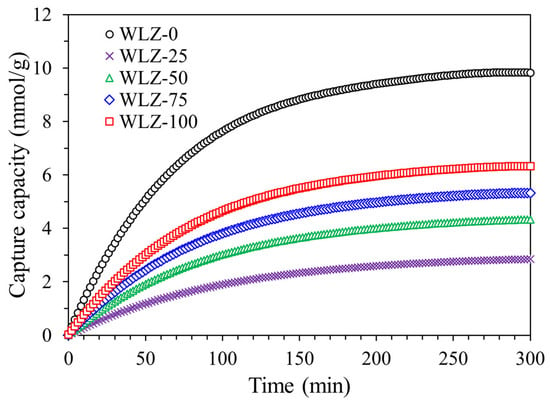

To evaluate the effect of water loading on ammonia capture, the capture capacity of WLZ was assessed using various water loading. Due to the toxicity and high reactivity of ammonia, all capture tests were conducted under controlled conditions with high-purity ammonia gas to ensure repeatability and experimental safety. Figure 7 shows the ammonia capture capacity at different water loading concentration. The dry zeolite (WLZ-0) exhibited the highest capture capacity at 9.45 mmol/g. Because these experiments were performed under ambient air conditions, the comparison between WLZ-0 and WLZ-75 effectively reflects the influence of ammonia–water co-existence on ammonia capture performance. Compared to dry zeolite (WLZ-0), the ammonia capture capacity decreased upon water loading. However, among the water-loaded samples, the capture capacity increased with increasing water content from WLZ-25 to WLZ-100, reaching values of 2.75, 4.58, and 6.75 mmol/g, respectively. Notably, although water partially impedes ammonia access to the micropores by occupying capture sites, a slight increase in ammonia uptake was observed as water loading increased from 25% to 100%, suggesting that water facilitates ammonia capture under certain conditions. This behavior is likely due to the formation of ammonium-water clusters through acid–base interactions or hydrogen bonding. Water molecules within the zeolite pores can act as proton donors, forming weakly bound, thermally unstable, and reversible ammonium ion species [17,35]. In hydrated systems, the zeolite framework primarily serves as a scaffold for water molecules rather than as a direct capture site, resulting in lower overall ammonia uptake compared to dry samples. Furthermore, all samples exhibited biphasic capture kinetics. As shown in Figure 7, rapid uptake occurs during the initial stage (within 100 min), attributed to fast capture on the surface and within micropores. This is followed by a slower, diffusion-limited phase, gradually filling the available sites within pores that are either protected by water or difficult to access [36].

Figure 7.

Ammonia capture capacity at different water loading concentration.

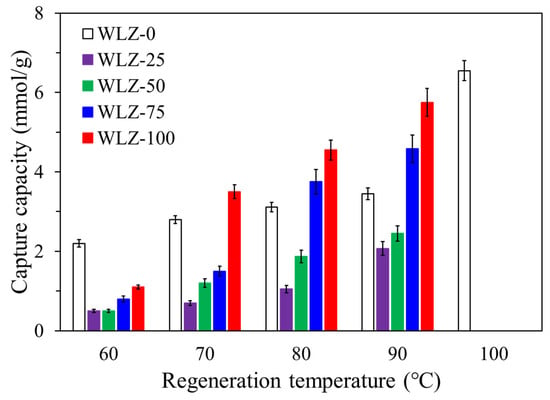

To evaluate regeneration performance, Figure 8 shows the ammonia capture capacity by regeneration temperature. A positive correlation between regeneration temperature and ammonia release was observed for all WLZ samples. This trend indicates that ammonia capture is largely reversible and thermally activated, enabling material reuse without significant degradation. Notably, regeneration above 100 °C was not attempted to prevent evaporation of retained water and structural destabilization of the water-containing zeolite. This limitation aligns with the objective of developing a low-temperature regeneration system suitable for low-grade thermal energy sources, such as industrial waste heat or solar air. Overall, the results demonstrate that WLZ can effectively capture and release ammonia at temperatures below 100 °C. The balance between water-based capture and regeneration efficiencies highlights the potential of WLZ as a reusable and thermally stable adsorbent for ammonia control in indoor and industrial environments.

Figure 8.

Ammonia capture capacity by regeneration temperature.

3.3. Cyclic Stability and Reusability

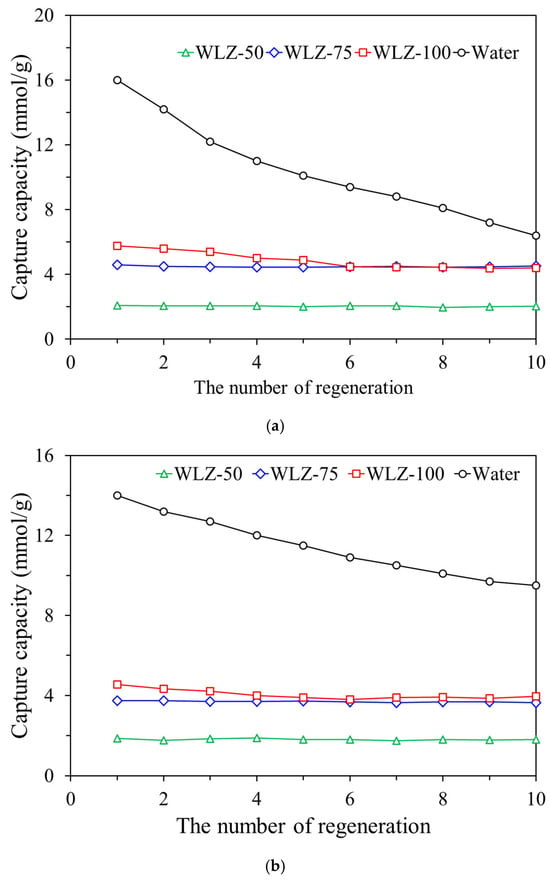

In practical applications involving continuous or long-term ammonia removal, adsorbent cycle stability and reusability are critical performance indicators. To assess these characteristics, ten consecutive ammonia capture–regeneration cycles were conducted using WLZ samples. The regeneration stability was evaluated over ten consecutive ammonia capture–regeneration cycles at regeneration temperatures of 80–90 °C, during which only minimal capacity loss was observed. WLZ-25 was excluded from this evaluation due to its inadequate capture performance in previous tests. Figure 9 shows the ammonia capture capacity by the number of regeneration cycles at two regeneration temperatures: 90 °C (Figure 9a) and 80 °C (Figure 9b). These temperatures were selected based on the results shown in Figure 8, which indicated that regeneration at temperatures below 70 °C significantly diminished adsorption performance. Among the samples tested, WLZ-50 and WLZ-75 demonstrated excellent cycle stability, maintaining consistent capture capacities over ten regeneration cycles at both temperatures. In contrast, WLZ-100 exhibited a gradual decline in capture performance, particularly during the first five to six cycles. This decline was more pronounced at 90 °C and was slightly mitigated at 80 °C.

Figure 9.

Ammonia capture capacity by the number of regeneration cycles at two regeneration temperatures: (a) 90 °C, (b) 80 °C.

The performance degradation observed in WLZ-100 is attributed to its high initial moisture content. Ammonia capture in WLZ systems is primarily driven by moisture through acid–base interactions rather than by physical adsorption within the zeolite pores. However, moisture loss can occur during regeneration due to vaporization caused by partial pressure gradients or entrainment by the desorbed ammonia gas stream. Consequently, WLZ-100 experienced continuous depletion of the active phase (i.e., moisture) and a decrease in capacity over time. In practical applications, such as ammonia-water capture systems, this issue is often addressed by installing a rectifier downstream of the regenerator [37]. The rectifier condenses and recovers any water vapor that would otherwise be lost, thereby maintaining the performance of the aqueous adsorption system. In Figure 9, the “Water” represents the case where water alone (without a zeolite support) was used as the capture material. This configuration exhibited a steady decline in performance throughout the cycle, underscoring the importance of a porous support to retain water and enhance structural integrity. Interestingly, after 5–6 regeneration cycles, WLZ-100 stabilized and exhibited a performance plateau similar to that of WLZ-75. Based on these observations, a 75% water content was identified as the optimal formulation, achieving a balance of effective ammonia capture, minimal water loss, and high cycle stability.

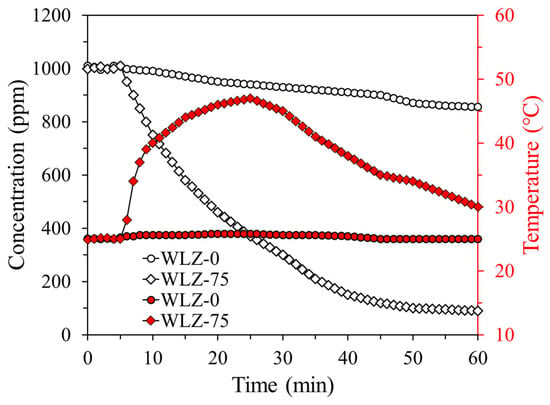

3.4. Chamber-Scale Ammonia Capture

To simulate a realistic ammonia leak scenario in a confined environment, chamber-scale experiments were conducted using WLZ-based capture materials. Based on the regeneration performance discussed in the previous section, WLZ-75 was selected as the optimal candidate, while pristine zeolite 13X (WLZ-0) was evaluated as the reference material. Figure 10 presents the profiles of ammonia concentration and capture material temperature in ammonia-containing air. Five minutes after the start of the experiment, the chamber damper was opened to allow direct contact between the capture material and the ammonia-containing atmosphere. The ammonia concentration for WLZ-0 reached approximately 880 ppm after 60 min and then gradually decreased due to the relatively low adsorption capacity of the dry zeolite under diluted conditions. In contrast, the ammonia concentration for WLZ-75 decreased rapidly, reaching approximately 90 ppm within the same time frame. These differences arise from the underlying capture mechanism. WLZ-0 relies primarily on physical adsorption driven by a concentration gradient, which is ineffective at low concentrations such as 1000 ppm. Conversely, WLZ-75, pre-loaded with water, facilitates a chemical adsorption-like reaction with ammonia, achieving much faster and higher capture efficiencies. Furthermore, the ammonia capture process of WLZ-75 was exothermic, accompanied by a significant temperature increase. While WLZ-0 exhibited temperature changes (<1 °C), WLZ-75 showed a substantial temperature rise, up to 45 °C. The temperature signal represents a localized, bulk-scale exothermic response arising from ammonia exposure under simulated leak conditions, rather than an equilibrium thermodynamic adsorption enthalpy as typically measured by DSC or microcalorimetry. This pronounced thermal response reflects localized heat generation at the material surface and demonstrates the potential of WLZ-75 for thermally assisted ammonia leak detection.

Figure 10.

Profiles of ammonia concentration and capture material temperature in ammonia-containing air (open symbols represent the ammonia concentration in air, while filled symbols indicate the temperature of the capture material, packing density of capture material: 30 g/m3).

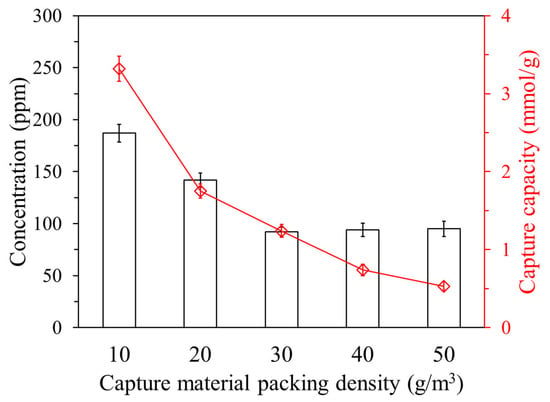

Figure 11 shows the final ammonia concentration and ammonia capture capacity by the packing density of the capture material within a 1 m3 chamber. Packing density (g/m3) denotes the mass of the adsorbent relative to the chamber volume. As the packing density increased from 10 to 30 g/m3, the final ammonia concentration decreased significantly, indicating enhanced capture efficiency. However, beyond 30 g/m3, the concentration plateaued, suggesting a decline in adsorption performance. Although increasing the adsorbent mass enhances the overall capture potential, the molar adsorption per unit mass decreases due to the dilution of the active surface area per gram of material. Therefore, while lower packing densities improve performance on a per-mass basis, industrial applications require a balance that favors higher packing densities to achieve effective contaminant removal.

Figure 11.

Final ammonia concentration and ammonia capture capacity by the packing density of capture material in a 1 m3 chamber.

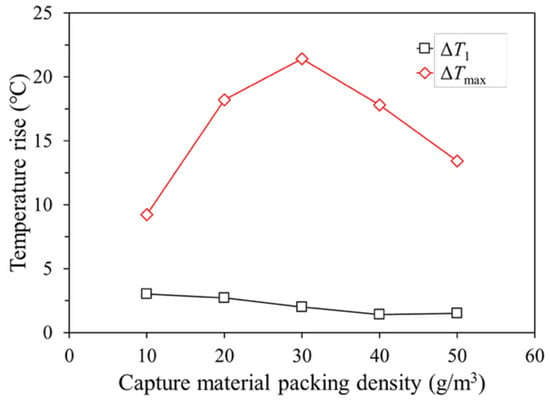

Figure 12 shows the temperature rise of the capture material by the packing density. All samples exhibited a temperature increase of more than 2 °C within one minute of ammonia exposure, indicating that the thermal response can detect gas release at an early stage. Notably, the maximum temperature increase occurred at a packing density of 30 g/m3, after which it declined. This trend may be qualitatively attributed to two opposing factors: at lower packing densities, the exothermic response appears more concentrated, while the smaller effective thermal mass makes the system more susceptible to convective cooling; at higher packing densities, the thermal mass is greater, but the apparent reaction rate may decrease due to diffusion limitations or partial saturation of adsorption capacity.

Figure 12.

Temperature rise of the capture material by the packing density.

These results suggest that the optimal packing density (~30 g/m3) balances efficient ammonia removal with a measurable thermal response. This insight opens the possibility of designing smart detection systems by embedding simple thermocouple-based temperature sensors into the adsorbent housing. While this approach may not be suitable for detecting trace leaks, it shows promise for large-scale industrial applications, such as ammonia refrigeration systems or ammonia-powered combustion engines, where rapid and unambiguous thermal signals can be reliably monitored.

For samples with excessive water loading, such as WLZ-100, the gradual decline in capture performance is likely associated with progressive water depletion during repeated regeneration. While not investigated in the present study, this behavior suggests that maintaining an appropriate water content during regeneration, for example, through controlled humidification, could be important for improving long-term stability.

To contextualize the performance of this system, Table 3 compares the ammonia adsorption characteristics of representative zeolite-based materials reported in the literature under various operating conditions. Although previous studies [17,22,28,38,39,40,41,42,43] have primarily focused on metal-MOFs, these typically require high regeneration temperatures (>100 °C). In contrast, the WLZ-75 system examined in this study exhibited an ammonia capture capacity of 6.75 mmol/g at low concentrations (~1000 ppm) and under humid ambient air conditions (65% relative humidity), with regeneration achievable at temperatures below 90 °C. These findings demonstrate that this study addresses practical ammonia control scenarios that are not sufficiently covered by existing adsorption benchmarks.

Table 3.

Comparison of ammonia adsorption performance of representative materials reported in the literature and the present WLZ system.

4. Conclusions

In this study, a regenerable ammonia capture material, water-loaded zeolite 13X (WLZ), was developed and optimized for low-temperature operation. The WLZ material demonstrated excellent thermal and structural stability. At the optimal moisture content (WLZ-75), it achieved an ammonia removal efficiency exceeding 90% and maintained consistent performance over 10 regeneration cycles at temperatures below 90 °C.

Chamber-scale testing demonstrated that WLZ-75 was highly effective in low-ammonia environments and exhibited significant exothermic behavior, enabling passive, thermally based leak detection. The thermal response was found to be highly dependent on the adsorbent packing density, with 30 g/m3 identified as the optimal value for both capture and detection.

These results demonstrate the practical feasibility of WLZ as a versatile material for safe and energy-efficient ammonia management in refrigeration systems, fuel applications, and sealed environments. This hybrid approach overcomes critical limitations in ammonia recovery and monitoring, offering a viable pathway toward safer and more widespread adoption of ammonia in carbon-neutral technologies.

Despite these promising results, while WLZ-75 demonstrated excellent reusability over more than 10 regeneration cycles at 80–90 °C, this study was conducted under controlled laboratory conditions and involved a relatively small number of regeneration cycles. For practical applications in refrigeration systems or confined space safety systems, evaluations over extended regeneration cycles and under varying ambient humidity conditions are necessary to better understand potential moisture loss mechanisms and their impact on ammonia capture capacity. These considerations provide important directions for future research. The relative humidity was approximately 65%, corresponding to the ambient laboratory conditions in a coastal environment, ensuring experimental consistency under realistically humid conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W.L.; methodology, B.K. and J.W.L.; investigation, B.K.; data curation, B.K.; formal analysis, B.K.; writing—original draft preparation, B.K.; writing—review and editing, B.K. and J.W.L.; supervision, J.W.L.; project administration, J.W.L.; funding acquisition, J.W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (RS-2025-00523335) and the Commercialization Promotion Agency for R&D Outcomes (COMPA) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT). (RS-2025-25416427, University Technology Management Promotion Project (TLO Innovation Type)_NATIONAL KOREA MARITIME & OCEAN UNIVERSITY).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used ChatGPT-4o for assistance with manuscript structuring, language refinement, and translation. The author has thoroughly reviewed and edited all AI-generated content and assumes full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| BET | Brunauer–Emmett–Teller |

| C | Concentration of ammonia in air (ppm) |

| CC | Ammonia Capture Capacity (mmol/g) |

| EDS | Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy |

| FE-SEM | Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscope |

| m | Mass of adsorbent (g) |

| MOF | Metal–Organic Framework |

| P | Pressure (bar) |

| ppm | Parts Per Million |

| RH | Relative Humidity |

| RTD | Resistance Temperature Detector |

| T | Temperature (°C) |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric Analysis |

| V | Volume (m3) |

| WLZ | Water-Loaded Zeolite 13X |

References

- MEPC. 2023 IMO Strategy on Reduction of GHG Emissions from Ships; International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Machaj, K.; Kupecki, J.; Malecha, Z.; Morawski, A.W.; Skrzypkiewicz, M.; Stanclik, M.; Chorowski, M. Ammonia as a Potential Marine Fuel: A Review. Energy Strategy Rev. 2022, 44, 100926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.; Juangsa, F.B.; Irhamna, A.R.; Irsyad, A.R.; Hariana, H.; Darmawan, A. Ammonia Utilization Technology for Thermal Power Generation: A Review. J. Energy Inst. 2023, 111, 101365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, A. Refrigeration with Ammonia. Int. J. Refrig. 2008, 31, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expósito Carrillo, J.A.; Gomis Payá, I.; Peris Pérez, B.; Sánchez de La Flor, F.J.; Salmerón Lissén, J.M. Experimental Performance Analysis of a Novel Ultra-Low Charge Ammonia Air Condensed Chiller. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 195, 117117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valera-Medina, A.; Xiao, H.; Owen-Jones, M.; David, W.I.F.; Bowen, P.J. Ammonia for Power. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2018, 69, 63–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Hayakawa, A.; Somarathne, K.D.K.A.; Okafor, E.C. Science and Technology of Ammonia Combustion. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2019, 37, 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). The Future of Cooling; IEA Publications: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Calm, J.M. The next Generation of Refrigerants—Historical Review, Considerations, and Outlook. Int. J. Refrig. 2008, 31, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zini, A.; Socci, L.; Vaccaro, G.; Rocchetti, A.; Talluri, L. Working Fluid Selection for High-Temperature Heat Pumps: A Comprehensive Evaluation. Energies 2024, 17, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Fan, C.; Li, D.; Chen, Y.; Yao, F. Economic and Exergy Assessments for Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion Using Environment-Friendly Fluids. Processes 2025, 13, 2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Bradshaw, C.R. Quantitative comparison of the performance of vapor compression cycles with compressor vapor or liquid injection. Int. J. Refrig. 2023, 154, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantillo, S.M.R.; Callejo, G.A.C.; Camacho, S.M.K.G.; Montalban, M.A.; Valderin, R.E.; Rubi, R.V.C. Future Trends of Natural Refrigerants: Selection, Preparation, and Evaluation. Eng. Proc. 2024, 67, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorowski, M.; Lepszy, M.; Machaj, K.; Malecha, Z.; Porwisiak, D.; Porwisiak, P.; Rogala, Z.; Stanclik, M. Challenges of Application of Green Ammonia as Fuel in Onshore Transportation. Energies 2023, 16, 4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AMMONIA | Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npg/npgd0028.html (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Khudhur, D.A.; Tuan Abdullah, T.A.; Norazahar, N. A Review of Safety Issues and Risk Assessment of Industrial Ammonia Refrigeration System. ACS Chem. Health Saf. 2022, 29, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, G.; Xia, X.; Wu, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, S. Metal–Organic Frameworks for Ammonia-Based Thermal Energy Storage. Small 2021, 17, 2102689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Pei, D.; Tian, R.; Lu, C. Screening the Specific Surface Area for Metal-Organic Frameworks by Cataluminescence. Chemosensors 2023, 11, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, B.E.; Turkiewicz, A.B.; Furukawa, H.; Paley, M.V.; Velasquez, E.O.; Dods, M.N.; Long, J.R. A Ligand Insertion Mechanism for Cooperative NH3 Capture in Metal–Organic Frameworks. Nature 2023, 613, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hack, J.H.; Dombrowski, J.P.; Ma, X.; Chen, Y.; Lewis, N.H.; Carpenter, W.B.; Li, C.; Voth, G.A.; Kung, H.H.; Tokmakoff, A. Structural Characterization of Protonated Water Clusters Confined in HZSM-5 Zeolites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 10203–10213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhakisheva, B.; Gutiérrez-Sevillano, J.J.; Calero, S. Ammonia and Water in Zeolites: Effect of Aluminum Distribution on the Heat of Adsorption. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 306, 122564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matito-Martos, I.; Martin-Calvo, A.; Ania, C.O.; Parra, J.B.; Vicent-Luna, J.M.; Calero, S. Role of Hydrogen Bonding in the Capture and Storage of Ammonia in Zeolites. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 387, 124062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Guan, B.; Zhuang, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhu, L.; Ma, Z.; Hu, X.; Zhu, C.; Zhao, S.; Shu, K. Advances in Ammonia (NH3) Adsorption and Storage: Materials, Mechanisms, and Applications. Adsorption 2025, 31, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza, L.F.; de Gracia, A.; Zsembinszki, G.; Borri, E. Perspectives on Thermal Energy Storage Research. Energy 2021, 231, 120943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehari, A.; Zhang, Y.X.; Si, H.; Zheng, X.; Jiang, L. Ammonia Adsorption Technology Using Next-Generation Materials for Decarbonized Heating. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 475, 170835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Duy, L.; Thi Nguyet, T.; Hung, C.M.; Van Duy, N.; Hoa, N.D.; Catini, A.; Magna, G.; Paolesse, R.; Biasioli, F.; Tonezzer, M.; et al. Light-Assisted Room Temperature Ammonia Gas Sensor Based on Porphyrin-Coated V2O5 Nanosheets. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2024, 409, 135582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gribkova, O.L.; Kabanova, V.A.; Rodina, E.I.; Teplonogova, M.A.; Demina, L.I.; Nekrasov, A.A. Optical Ammonia Sensors Based on Spray-Coated Polyaniline Complexes with Polysulfonic Acids. Sensors 2025, 25, 3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Park, J.H.; Choi, H.W.; Kang, Y.T. Ammonia sorption thermal battery with water-loaded sorbent driven by low-temperature heat source. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 295, 117653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, M.; Mandal, M.K.; Ghosh Chaudhuri, R. Covalent Organic Frameworks: A State-of-the-Art from Design, Synthesis to Gas Sensing Application with the Prospect of Ammonia Gas Detection. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2025, 9, e00215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Wu, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, B.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, T.; Xi, S. The Development Prospects and Potential of High Specific Surface Area Materials: A Review of the Use of Porous Framework Materials for the Capture and Filtration of Ammonia. Molecules 2025, 30, 1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.Y.; Wang, Z.M.; Sun, X.Q.; Zeng, S.J.; Guo, Y.Y.; Bai, L.; Yao, M.S.; Zhang, X.P. Advanced Materials for NH3 Capture: Interaction Sites and Transport Pathways. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024, 16, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahmanzadegan, F.; Ghaemi, A. Modification and Functionalization of Zeolites to Improve the Efficiency of CO2 Adsorption: A Review. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 9, 100564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.G.; Lee, W.H.; Yoo, B.; Lee, S.; Ahn, J.P.; El-Zoka, A.A.; Kim, S.H. Atomic-Scale Analysis of Long-Term Degraded Zeolite 13X. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2025, 109, e70309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J.N.; Song, L.; Askarli, S.; Chung, S.-H.; Ruiz-Martínez, J. Zeolite–Water Chemistry: Characterization Methods to Unveil Zeolite Structure. Chemistry-Methods 2025, 5, e202400076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, A.A.; Len, T.; de Oliveira, A.d.N.; Costa, A.A.F.d.; Souza, A.R.d.S.; Costa, C.E.F.d.; Luque, R.; Rocha Filho, G.N.d.; Noronha, R.C.R.; Nascimento, L.A.S.d. Zeolites: A Theoretical and Practical Approach with Uses in (Bio)Chemical Processes. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.H.; Sun, M.H.; Wang, Z.; Yang, W.; Xie, Z.; Su, B.L. Hierarchically Structured Zeolites: From Design to Application. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 11194–11294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braccio, S.; Phan, H.T.; Wirtz, M.; Tauveron, N.; Le Pierrès, N. Simulation of an Ammonia-Water Absorption Cycle Using Exchanger Effectiveness. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 213, 118712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, T.G.; Peterson, G.W.; Schindler, B.J.; Britt, D.; Yaghi, O.M. MOF-74 Building Unit Has a Direct Impact on Toxic Gas Adsorption. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2011, 66, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieth, A.J.; Tulchinsky, Y.; Dincă, M. High and Reversible Ammonia Uptake in Mesoporous Azolate Metal–Organic Frameworks with Open Mn, Co, and Ni Sites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 9401–9404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabzina, Y.; Farrusseng, D. Unravelling Ammonia Adsorption Mechanisms of Adsorbents in Humid Conditions. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2018, 265, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helminen, J.; Helenius, J.; Paatero, E.; Turunen, I. Adsorption Equilibria of Ammonia Gas on Inorganic and Organic Sorbents at 298.15 K. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2001, 46, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero, J.M.; Crawford, J.M.; Wolden, C.A.; Carreon, M.A. Tunability of Ammonia Adsorption over NaP Zeolite. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2021, 324, 111288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Park, K.Y.; Joo, J.B.; Bae, S. Enhanced and Prolonged Adsorption of Ammonia Gas by Zeolites Derived from Coal Fly Ash. Chemosphere 2024, 368, 143799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.