MAWC-Net: A Multi-Scale Attention Wavelet Convolutional Neural Network for Soil pH Prediction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset and Preprocessing

2.2. Division of Soil Spectral Data

2.3. Modeling Method

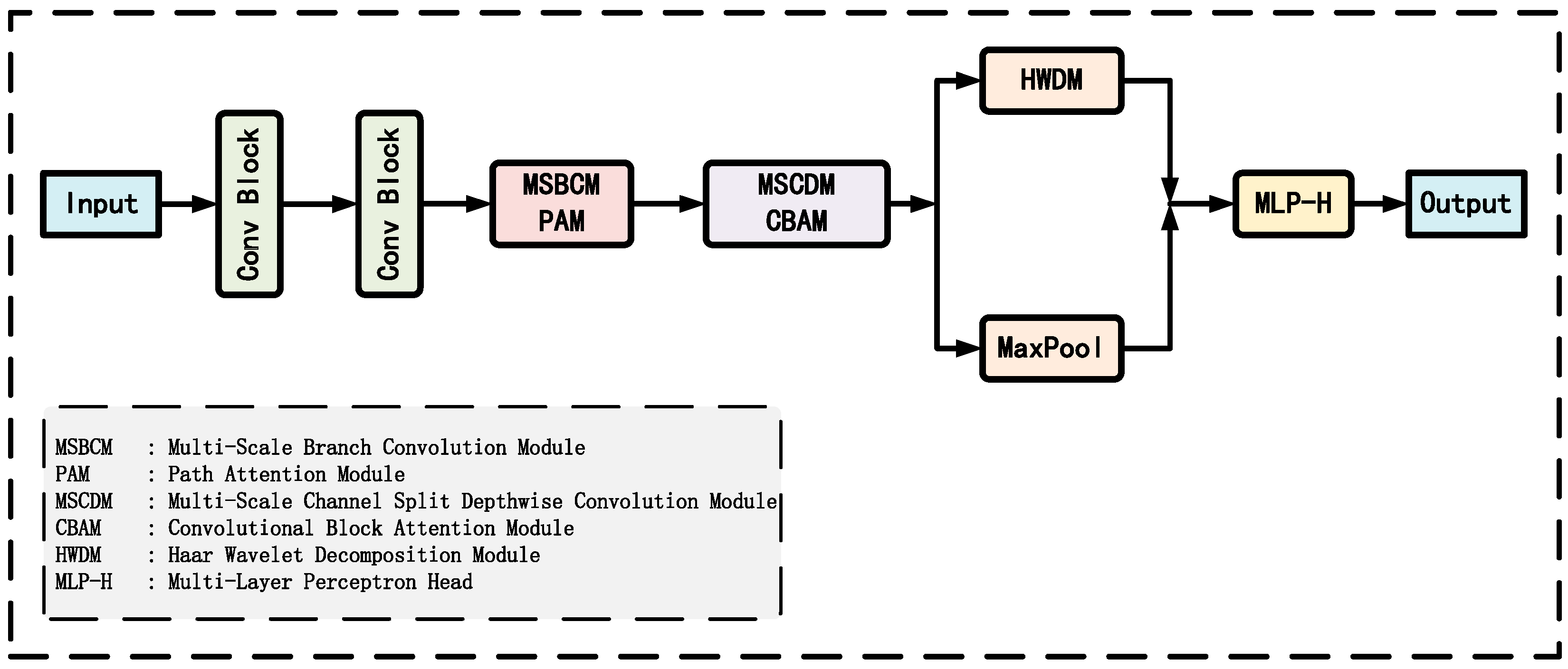

2.3.1. Overall Model Architecture

2.3.2. Multi-Scale Branch Convolution Module

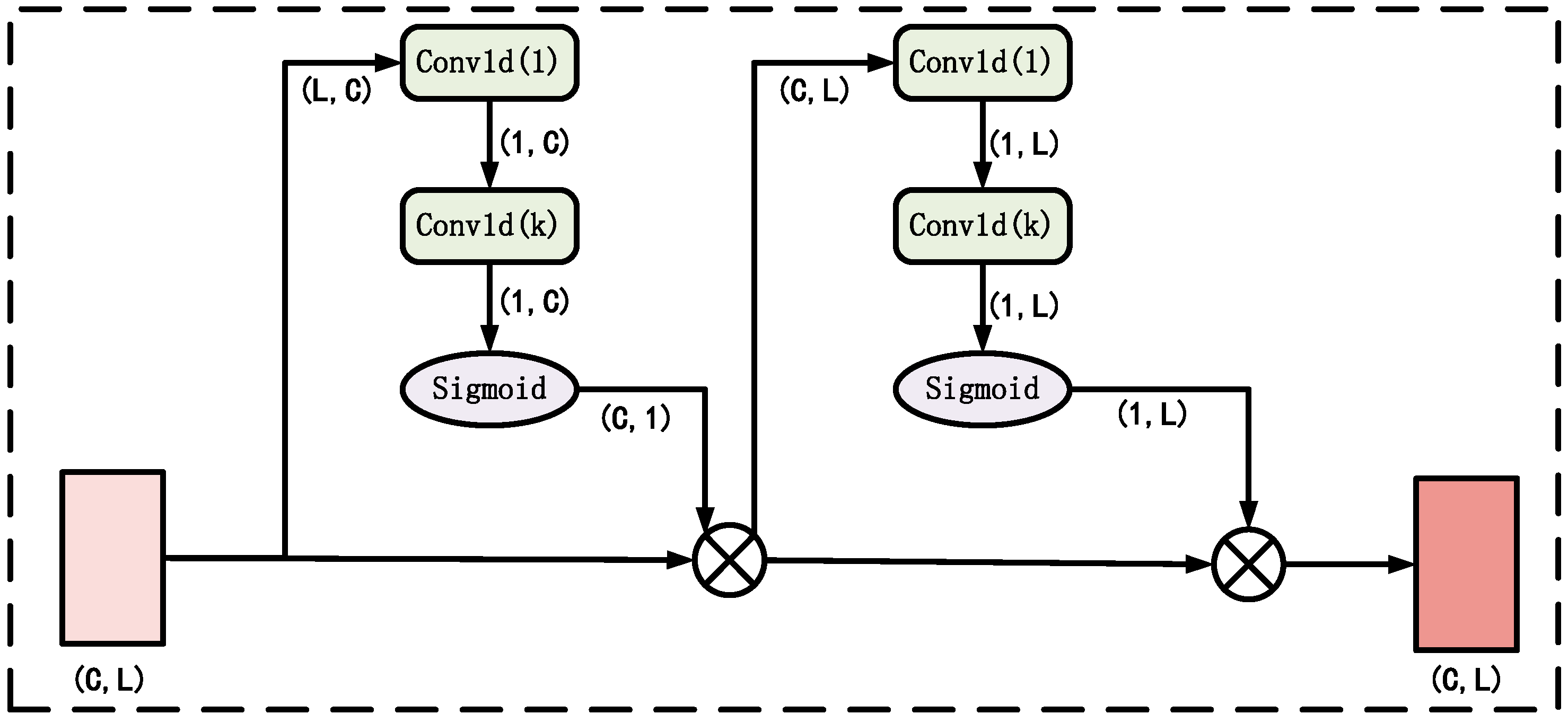

2.3.3. Path Attention Module

2.3.4. Multi-Scale Channel Split Depthwise Convolution Module

2.3.5. Convolutional Block Attention Module

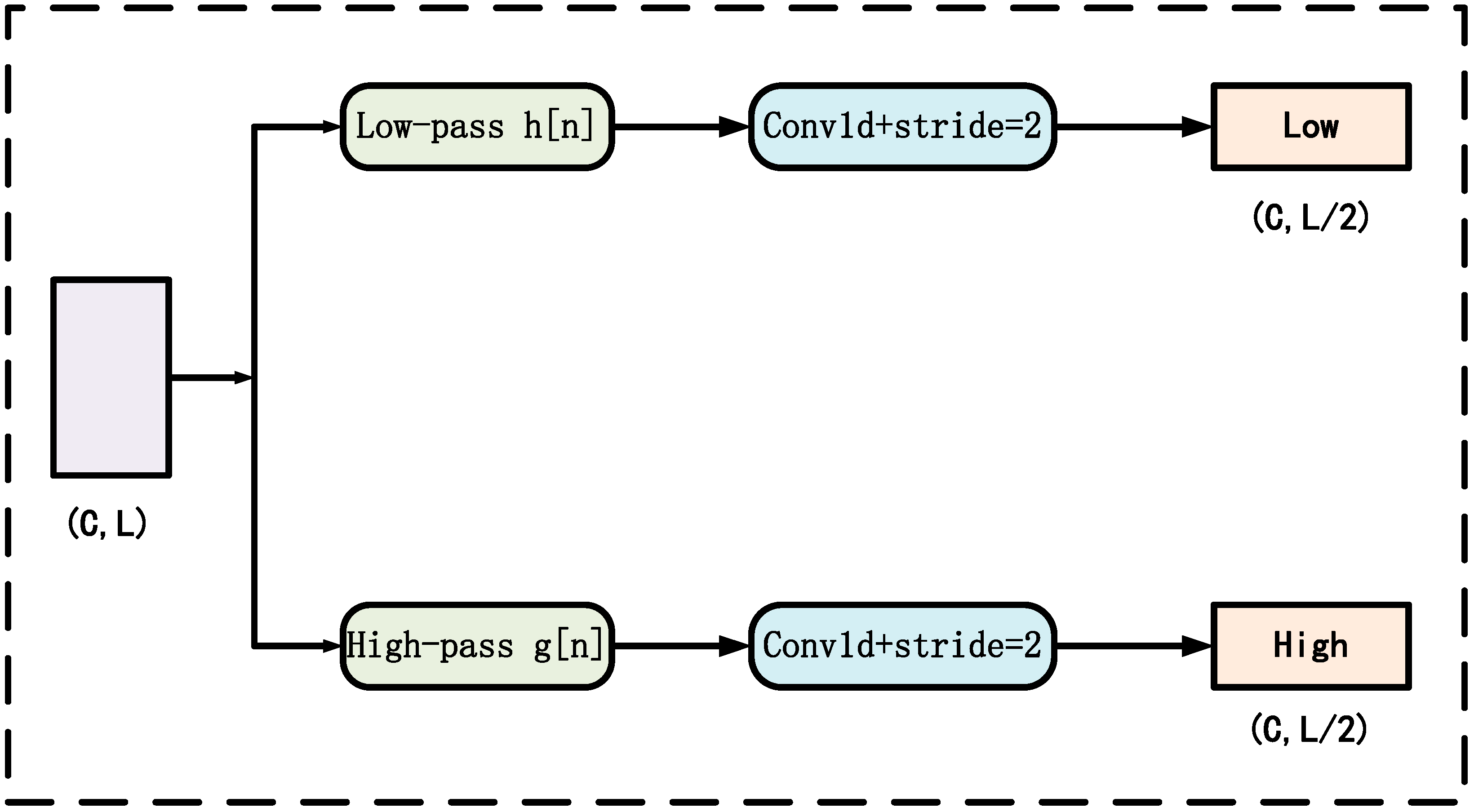

2.3.6. Haar Wavelet Decomposition Module

2.4. Evaluation Metrics

2.5. Experimental Setup

3. Results

3.1. Ablation Experiment

3.2. Comparative Experiment

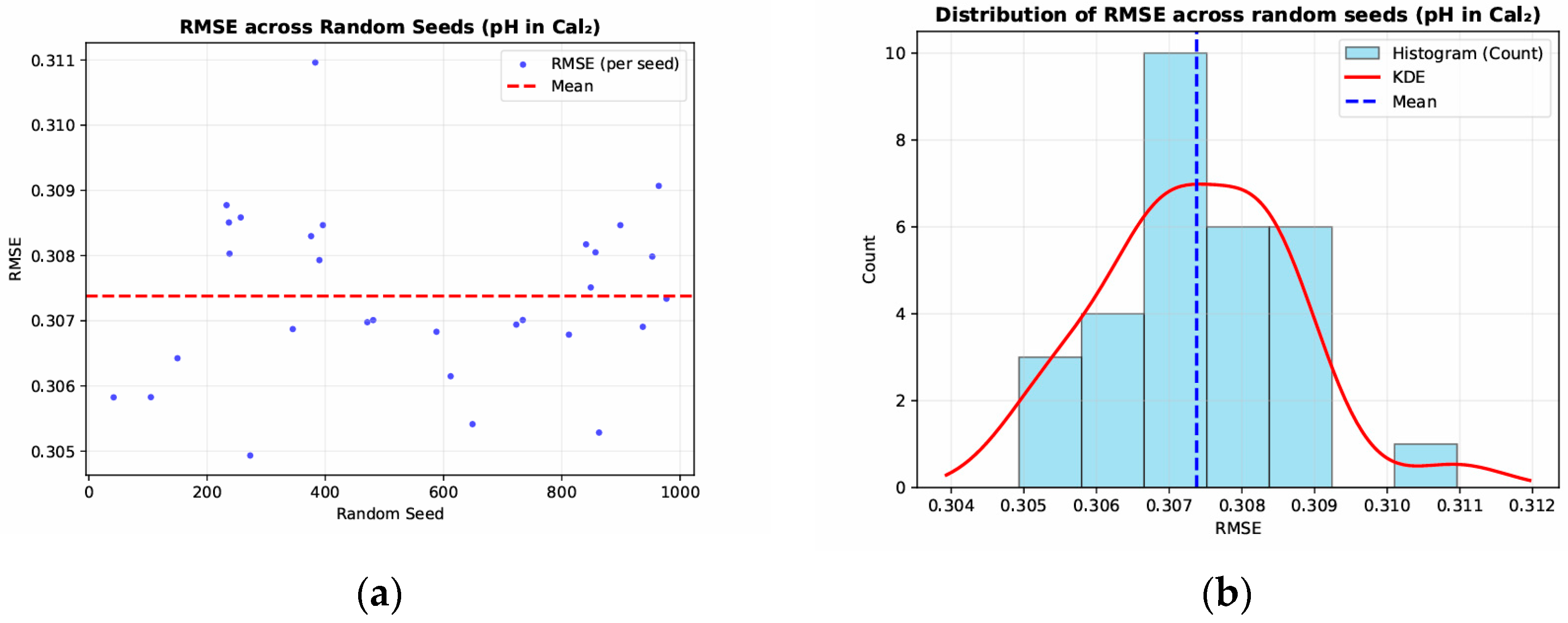

3.3. Robustness and Reproducibility Verification

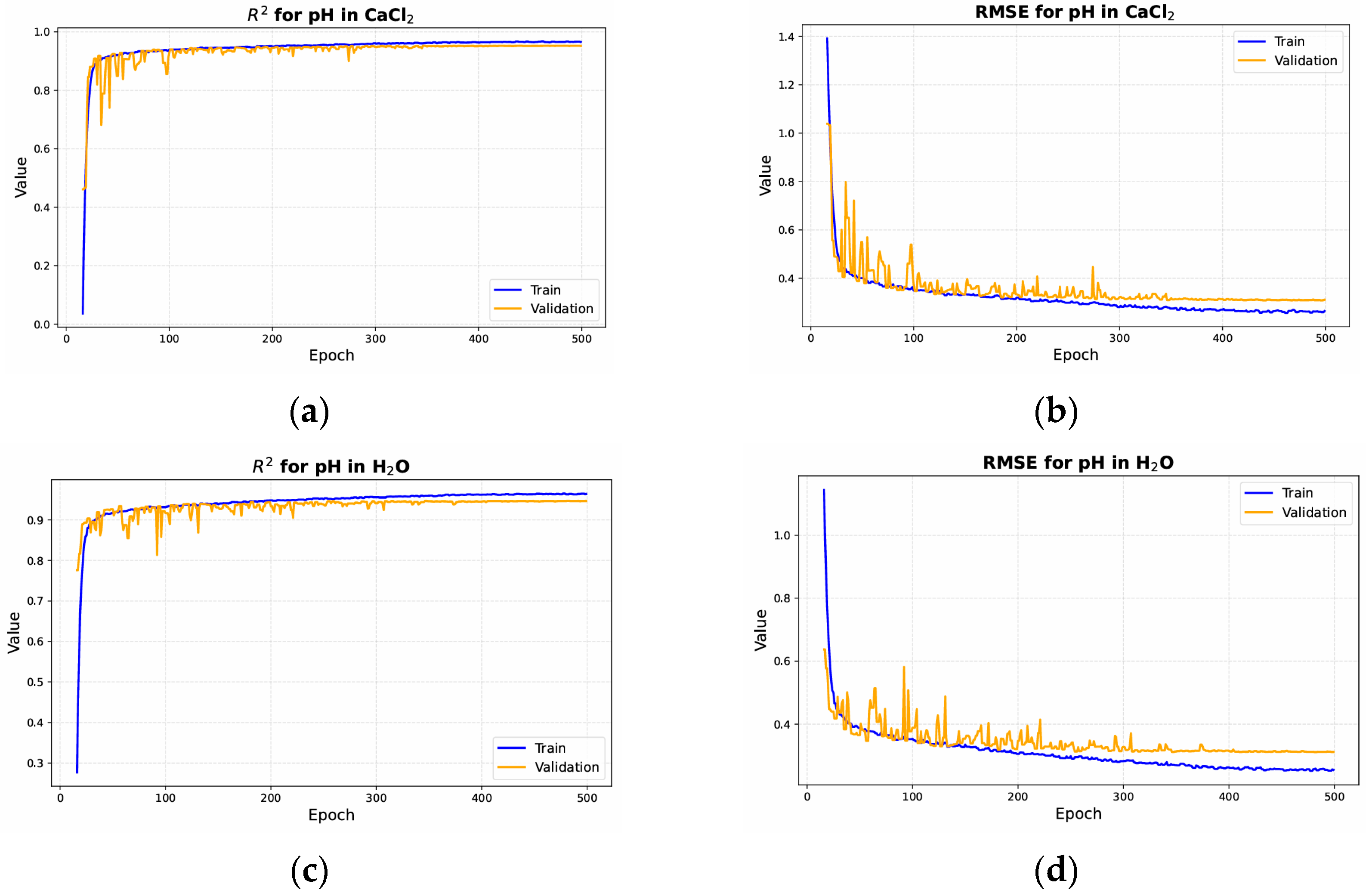

- Overall Stability: For pH(CaCl2), the average RMSE was approximately 0.307, with values ranging roughly from 0.305 to 0.311. For pH(H2O), the mean RMSE was around 0.315, fluctuating between approximately 0.311 and 0.316. The minimal variation across different random seeds indicates that the model maintains consistent performance in repeated trials.

- Distribution Concentration: The RMSE histograms and kernel density estimation (KDE) curves exhibit an approximately normal shape, with the mean closely matching the mode. This pattern further supports that the model’s predictive accuracy is largely independent of the choice of random seed.

- Robustness Assessment: Across repeated experiments for both pH(CaCl2) and pH(H2O), no extreme outliers or abrupt deviations were observed. This demonstrates that the model remains stable and robust under varying initialization conditions, highlighting its strong generalization ability and minimizing the influence of random factors on predictive outcomes.

4. Discussion

4.1. Further Analysis and Evaluation of Experimental Results

4.2. Method Advantages and Limitations

- Multi-scale Feature Extraction: The multi-scale convolution strategy is well suited for one-dimensional spectral data without an explicit temporal dimension. Parallel convolutions with different kernel sizes (e.g., 3, 5, 7, 9) allow the network to extract features at multiple receptive fields, capturing both narrow absorption peaks and broader spectral patterns. In contrast, Transformer architectures are primarily designed for sequential data with temporal dependencies, where self-attention mechanisms dynamically model long-range interactions. In the attention-based study [32], the core architecture relies on heavy self-attention mechanisms. In the Transformer-based study [33], the primary modeling component is again the Transformer with multi-head self-attention. When using a Transformer architecture, the multi-head self-attention mechanism is an essential component. In self-attention, the input features must be projected into query (Q), key (K), and value (V) matrices through separate learned linear transformations. The attention operation then computes QKT followed by a softmax normalization and a weighted multiplication with V. These steps involve multiple large matrix multiplications, and in the multi-head setting, they are repeated across several attention heads. As a result, the computational cost grows significantly, leading to substantial memory usage and increased runtime complexity. During our preliminary experiments, we also evaluated self-attention modules, but the computational overhead was prohibitive given the limitations of our hardware. Therefore, we focused on computationally efficient alternatives that still retain strong representational capacity.

- Attention Mechanisms: The network employs PAM and CBAM to perform adaptive feature weighting across multiple layers. PAM selectively emphasizes informative feature paths, while CBAM adaptively reweights feature channels and spatial locations. These attention mechanisms help the model focus on relevant spectral and spatial information, thereby enhancing feature representation and supporting improved predictive accuracy and generalization.

- Frequency-Domain Information Enhancement: The model incorporates a HWDM to project time-domain features into low- and high-frequency sub-bands. By processing these sub-bands separately, the model captures fine-grained frequency-domain variations, enhancing feature representation and supporting more robust and reliable predictions.

- Practical Implications: In practical soil-sensing scenarios, MAWC-Net demonstrates strong potential for rapid and accurate pH estimation, which is valuable for precision agriculture, soil fertility assessment, and field-scale monitoring. These findings suggest that MAWC-Net can serve as a promising tool for real-time or near-real-time soil analysis, although future lightweighting or model compression may be required for deployment on portable spectrometers.

- Interpretability: Although multiple attention mechanisms enhance critical spectral regions, the overall decision-making process remains difficult to interpret due to the network’s structural complexity. The coupling of different modules (e.g., the combined effects of CBAM and PAM) improves performance but makes it challenging to explicitly identify which spectral bands play a dominant role in prediction. In soil spectral modeling, this reduced interpretability may limit the model’s ability to provide mechanistic insights.

- Model Lightweighting: While the design partially addresses model efficiency through MSCDM, MAWC-Net still integrates multi-scale convolutions, attention mechanisms, and wavelet decomposition. In resource-constrained scenarios (e.g., portable spectrometers or real-time analysis on mobile devices), model deployment may therefore be restricted. Future work should explore model compression and lightweight strategies to enhance applicability while maintaining predictive accuracy.

- Prediction biases: Some prediction biases were observed for soils with extreme pH values or atypical spectral characteristics. These deviations may arise from multiple factors, including the intrinsic difficulty of modeling extreme chemical conditions, variations introduced during hyperspectral acquisition (e.g., illumination, soil moisture, sample heterogeneity), or occasional measurement noise caused by instrument calibration and sample preparation. Understanding these failure patterns provides useful guidance for improving dataset diversity, refining preprocessing procedures, and enhancing the robustness of future model designs.

5. Conclusions

- Superior predictive accuracy: The proposed MAWC-Net significantly outperforms both traditional statistical approaches and existing deep learning models in soil pH prediction, achieving higher coefficients of determination (R2) and lower root mean squared errors (RMSEs). These results confirm the effectiveness of combining multi-scale convolution with attention mechanisms.

- Necessity of each module: Ablation studies demonstrate that removing key components—such as the multi-scale convolution, attention mechanisms, or wavelet decomposition—consistently degrades model performance. This finding highlights the synergistic contribution of the overall network architecture to feature extraction and enhancement.

- Strong generalization and robustness: Comparative experiments and robustness tests show that MAWC-Net maintains stable predictive performance across different dataset partitions and random seed settings, indicating high reliability and robustness for soil spectral modeling.

- Areas for improvement in interpretability and lightweight design: Despite its superior accuracy, the model’s structural complexity limits mechanistic interpretability and deployment in resource-constrained environments. Future work should incorporate explainable-AI methods and model compression techniques to enhance the scientific interpretability and practical applicability of MAWC-Net.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yunta, F.; Schillaci, C.; Panagos, P.; Van Eynde, E.; Wojda, P.; Jones, A. Quantitative analysis of the compliance of EU Sewage Sludge Directive by using the heavy metal concentrations from LUCAS topsoil database. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 16554–16569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamanian, K.; Taghizadeh-Mehrjardi, R.; Tao, J.; Fan, L.; Raza, S.; Guggenberger, G.; Kuzyakov, Y. Acidification of European croplands by nitrogen fertilization: Consequences for carbonate losses, and soil health. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, Z.; Cui, B.; Sun, J.; Zeng, L.; Yang, R.; Wu, N.; Liu, T.; Pan, J.; et al. Continental-scale mapping of soil pH with SAR-optical fusion based on long-term earth observation data in google earth engine. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 165, 112246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Jeon, S.; Kwon, N.H.; Kwon, M.; Shin, J.H.; Kim, W.C.; Lee, J.G. Application of near-infrared spectroscopy to predict chemical properties in clay rich soil: A review. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 159, 127228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccini, C.; Metzger, K.; Debaene, G.; Stenberg, B.; Götzinger, S.; Boruvka, L.; Sandén, T.; Bragazza, L.; Liebisch, F. In-field soil spectroscopy in Vis–NIR range for fast and reliable soil analysis: A review. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2024, 75, e13481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Liu, S.; Jiang, L.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, X.; Shang, K.; Jiang, W.; Jiang, Z. Prediction and monitoring of soil pH using field reflectance spectroscopy and time-series Sentinel-2 remote sensing imagery. Geomatica 2025, 77, 100053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gözükara, G. Vis-NIR ve pXRF Spektrometrelerinin Toprak Biliminde Kullanımı. Türkiye Tarımsal Araştırmalar Derg. 2021, 8, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, S.; Lu, R.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Y.; Shi, Z. Non-linear memory-based learning for predicting soil properties using a regional vis-NIR spectral library. Geoderma 2024, 441, 116752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinpour-Zarnaq, M.; Omid, M.; Sarmadian, F.; Ghasemi-Mobtaker, H. A CNN model for predicting soil properties using VIS–NIR spectral data. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cheng, G.; He, L. Convolutional Neural networks based on parallel multi-scale pooling branch: A transfer diagnosis method for mechanical vibrational signal with less computational cost. Measurement 2022, 192, 110905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, T.; Sun, D.W. Achieving joint calibration of soil Vis-NIR spectra across instruments, soil types and properties by an attention-based spectra encoding-spectra/property decoding architecture. Geoderma 2022, 405, 115449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Zhou, J.; Rao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Ba, W.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, T. An innovative approach for integrating two-dimensional conversion of Vis-NIR spectra with the Swin Transformer model to leverage deep learning for predicting soil properties. Geoderma 2023, 436, 116555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, M. Multi-Scale Spatial Attention-Based Multi-Channel 2D Convolutional Network for Soil Property Prediction. Sensors 2024, 24, 4728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberioon, M.; Gholizadeh, A.; Ghaznavi, A.; Chabrillat, S.; Khosravi, V. Enhancing soil organic carbon prediction of LUCAS soil database using deep learning and deep feature selection. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 227, 109494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shen, L.; Zhu, X.; Xie, Y.; He, S. Spectral data-driven prediction of soil properties using LSTM-CNN-attention model. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Leng, G.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, J.; Xu, W.; Xie, Z.; Wang, Y. Enhancing soil nitrogen measurement via visible-near infrared spectroscopy: Integrating soil particle size distribution with long short-term memory models. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 327, 125317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Wang, W.; Tian, P. Spectroscopic measurement of near-infrared soil pH parameters based on GhostNet-CBAM. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0325426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Yin, D.; Sun, M.; Yang, Y.; Hassan, M.; Duan, Y. ResHAN-GAM: A novel model for the inversion and prediction of soil organic matter content. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 90, 103192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Cao, Y.; Chen, S.; Cheng, X. Residual Attention Network with Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling for Soil Element Estimation in LUCAS Hyperspectral Data. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, M.W.; Zhou, Y.N.; Wang, L.; Zeng, L.T.; Cui, Y.P.; Sun, X.L. Simultaneous estimation of multiple soil properties from vis-NIR spectra using a multi-gate mixture-of-experts with data augmentation. Geoderma 2025, 453, 117127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Liu, L. SpatialFormer: A Model to Estimate Soil Organic Carbon Content Using Spectral and Spatial Information. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2025, 25, 3259–3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Song, L.; Zheng, L.; Ji, R. DSCformer: Lightweight model for predicting soil nitrogen content using VNIR-SWIR spectroscopy. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 230, 109761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leenen, M.; Pätzold, S.; Tóth, G.; Welp, G. A LUCAS-based mid-infrared soil spectral library: Its usefulness for soil survey and precision agriculture. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2022, 185, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clingensmith, C.M.; Grunwald, S. Predicting soil properties and interpreting Vis-NIR models from across continental United States. Sensors 2022, 22, 3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paheding, S.; Reyes, A.A.; Kasaragod, A.; Oommen, T. GAF-NAU: Gramian Angular Field encoded Neighborhood Attention U-Net for Pixel-Wise Hyperspectral Image Classification. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–20 June 2022; pp. 408–416. [Google Scholar]

- Nai, H.; Zhang, C.; Hu, X. Enhancing the Distinguishability of Minor Fluctuations in Time Series Classification Using Graph Representation: The MFSI-TSC Framework. Sensors 2025, 25, 4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, F.; Petzold, R.; Landmark, S.; Mollenhauer, H.; Becker, C.; Werban, U. Estimating Forest Soil Properties for Humus Assessment—Is Vis-NIR the Way to Go? Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadi, S.H.; Mouazen, A.M. Data fusion of XRF and Vis-nir using outer product analysis, granger–Ramanathan, and least squares for prediction of key soil attributes. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendleman, M.C.; Smith, B.J.; Canahuate, G.; Braun, T.A.; Buatti, J.M.; Casavant, T.L. Representative random sampling: An empirical evaluation of a novel bin stratification method for model performance estimation. Stat. Comput. 2022, 32, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilimitis, D.; Walsh, C.G. Practical considerations and applied examples of cross-validation for model development and evaluation in health care: Tutorial. JMIR AI 2023, 2, e49023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeghalmy, S.; Fazekas, A. A comparative study of the use of stratified cross-validation and distribution-balanced stratified cross-validation in imbalanced learning. Sensors 2023, 23, 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Evaluating cross-building transferability of attention-based automated fault detection and diagnosis for air handling units: Auditorium and hospital case study. Build. Environ. 2025, 287, 113889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. A hybrid SMOTE and Trans-CWGAN for data imbalance in real operational AHU AFDD: A case study of an auditorium building. Energy Build. 2025, 348, 116447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Set | Size | Mean | Std | IQR | Median | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH in CaCl2 | Complete | 19,036 | 5.59 | 1.43 | 2.68 | 5.64 | −1.30 |

| SG | 19,036 | 5.59 | 1.43 | 2.68 | 5.64 | −1.30 | |

| PAA | 19,036 | 5.59 | 1.43 | 2.68 | 5.64 | −1.30 | |

| Mahalanobis | 18,084 | 5.60 | 1.42 | 2.67 | 5.65 | −1.30 | |

| Train | 9644 | 5.60 | 1.42 | 2.67 | 5.64 | −1.30 | |

| Val | 2412 | 5.60 | 1.41 | 2.66 | 5.66 | −1.30 | |

| Test | 6028 | 5.60 | 1.42 | 2.67 | 5.65 | −1.30 | |

| pH in H2O | Complete | 19,036 | 6.20 | 1.35 | 2.45 | 6.21 | −1.24 |

| SG | 19,036 | 6.20 | 1.35 | 2.45 | 6.21 | −1.24 | |

| PAA | 19,036 | 6.20 | 1.35 | 2.45 | 6.21 | −1.24 | |

| Mahalanobis | 18,084 | 6.20 | 1.35 | 2.44 | 6.21 | −1.23 | |

| Train | 9644 | 6.20 | 1.35 | 2.44 | 6.20 | −1.23 | |

| Val | 2412 | 6.21 | 1.35 | 2.45 | 6.22 | −1.24 | |

| Test | 6028 | 6.20 | 1.35 | 2.44 | 6.21 | −1.23 |

| Module/Block | Type | Output | Parameter Setting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input | Input | [BS, 1, 128] | |

| Conv | Conv1d | [BS, 32, 128] | kernel_size = 3, filters = 32 |

| BatchNorm1d | [BS, 32, 128] | ||

| Sigmoid | [BS, 32, 128] | ||

| Conv | Conv1d | [BS, 32, 128] | kernel_size = 3, filters = 32 |

| BatchNorm1d | [BS, 32, 128] | ||

| Sigmoid | [BS, 32, 128] | ||

| MSBCM (k = 3,5,7,9) | 4 parallel branches | ||

| Per-branch | Conv1d | [BS, 64, 128] | kernel_size∈{3,5,7,9}, filters = 64, padding = ⌊k/2⌋ |

| BatchNorm1d | [BS, 64, 128] | ||

| Sigmoid | [BS, 64, 128] | ||

| PAM | [BS, 64, 128] | Path Attention Module | |

| MSCDM (k = 3,5,7,9) | 4 parallel branches | ||

| Per-branch | Conv1d | [BS, 32, 128] | kernel_size∈{3,5,7,9}, filters = 32, padding = ⌊k/2⌋, group = 16 |

| BatchNorm1d | [BS, 32, 128] | ||

| CBAM | [BS, 32, 128] | ||

| Conv1d | [BS, 32, 128] | kernel_size = 1, filters = 32 | |

| BatchNorm1d | [BS, 32, 128] | ||

| Fusion Layer | Conv1d | [BS, 128, 128] | kernel_size = 1, filters = 128 |

| BatchNorm1d | [BS, 128, 128] | ||

| Sigmoid | [BS, 128, 128] | ||

| MaxPool | MaxPool1d | [BS, 128, 64] | kernel_size = 2, stride = 2 |

| HWDM | [BS, 128, 64]×2 | Low-frequency + High-frequency | |

| MLP-H | Linear | [BS, 1024] | |

| BatchNorm1d | [BS, 1024] | ||

| Sigmoid | [BS, 1024] | ||

| Dropout | [BS, 1024] | dropout = 0.2 | |

| Linear | [BS, 128] | ||

| BatchNorm1d | [BS, 128] | ||

| Sigmoid | [BS, 128] | ||

| Linear | [BS, 1] |

| Model | R2 | RMSE | MAE | IQR | RPD | CCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BaseBlock | 0.940 | 0.346 | 0.242 | 0.251 | 4.10 | 0.970 |

| BaseBlock + MSBCM | 0.944 | 0.335 | 0.233 | 0.239 | 4.23 | 0.972 |

| BaseBlock + MSBCM + PAM | 0.946 | 0.329 | 0.230 | 0.239 | 4.31 | 0.973 |

| BaseBlock + MSCDM | 0.943 | 0.337 | 0.230 | 0.239 | 4.21 | 0.971 |

| BaseBlock + MSCDM + CBAM | 0.947 | 0.328 | 0.227 | 0.231 | 4.33 | 0.973 |

| BaseBlock + HWDM | 0.943 | 0.337 | 0.236 | 0.248 | 4.20 | 0.971 |

| MAWC-Net | 0.953 | 0.307 | 0.214 | 0.218 | 4.61 | 0.976 |

| Model | R2 | RMSE | MAE | IQR | RPD | CCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BaseBlock | 0.929 | 0.359 | 0.265 | 0.268 | 3.75 | 0.964 |

| BaseBlock + MSBCM | 0.935 | 0.343 | 0.252 | 0.255 | 3.92 | 0.967 |

| BaseBlock + MSBCM + PAM | 0.938 | 0.334 | 0.246 | 0.253 | 4.03 | 0.969 |

| BaseBlock + MSCDM | 0.935 | 0.344 | 0.254 | 0.260 | 3.92 | 0.967 |

| BaseBlock + MSCDM + CBAM | 0.938 | 0.336 | 0.247 | 0.249 | 4.01 | 0.968 |

| BaseBlock + HWDM | 0.933 | 0.348 | 0.258 | 0.263 | 3.87 | 0.966 |

| MAWC-Net | 0.945 | 0.315 | 0.231 | 0.235 | 4.28 | 0.972 |

| Model | R2 | RMSE | MAE | IQR | RPD | CCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLSR | 0.871 | 0.512 | 0.394 | 0.408 | 2.78 | 0.932 |

| Ridge | 0.870 | 0.513 | 0.394 | 0.406 | 2.78 | 0.931 |

| SVR | 0.871 | 0.511 | 0.356 | 0.372 | 2.79 | 0.934 |

| XGBoost | 0.722 | 0.752 | 0.586 | 0.614 | 1.90 | 0.836 |

| VGG16 | 0.935 | 0.360 | 0.254 | 0.262 | 3.93 | 0.967 |

| ResNet18 | 0.927 | 0.382 | 0.270 | 0.287 | 3.71 | 0.963 |

| CNN-Transformer | 0.940 | 0.346 | 0.244 | 0.252 | 4.09 | 0.969 |

| MAWC-Net | 0.953 | 0.307 | 0.214 | 0.218 | 4.61 | 0.976 |

| Model | R2 | RMSE | MAE | IQR | RPD | CCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLSR | 0.861 | 0.504 | 0.391 | 0.399 | 2.69 | 0.927 |

| Ridge | 0.861 | 0.505 | 0.392 | 0.398 | 2.68 | 0.926 |

| SVR | 0.877 | 0.474 | 0.360 | 0.373 | 2.86 | 0.936 |

| XGBoost | 0.723 | 0.713 | 0.557 | 0.578 | 1.90 | 0.837 |

| VGG16 | 0.926 | 0.367 | 0.273 | 0.285 | 3.67 | 0.962 |

| ResNet18 | 0.918 | 0.386 | 0.285 | 0.297 | 3.49 | 0.958 |

| CNN-Transformer | 0.932 | 0.352 | 0.261 | 0.267 | 3.83 | 0.965 |

| MAWC-Net | 0.945 | 0.315 | 0.231 | 0.235 | 4.28 | 0.972 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cheng, X.; Liu, Z.; Kang, Y.; Xie, X.; Deng, Y.; Lu, Q.; Tang, J.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, J. MAWC-Net: A Multi-Scale Attention Wavelet Convolutional Neural Network for Soil pH Prediction. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010054

Cheng X, Liu Z, Kang Y, Xie X, Deng Y, Lu Q, Tang J, Shi Y, Zhao J. MAWC-Net: A Multi-Scale Attention Wavelet Convolutional Neural Network for Soil pH Prediction. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010054

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Xiaohui, Zifeng Liu, Yanping Kang, Xiaolan Xie, Yun Deng, Qiu Lu, Jian Tang, Yuanyuan Shi, and Junyu Zhao. 2026. "MAWC-Net: A Multi-Scale Attention Wavelet Convolutional Neural Network for Soil pH Prediction" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010054

APA StyleCheng, X., Liu, Z., Kang, Y., Xie, X., Deng, Y., Lu, Q., Tang, J., Shi, Y., & Zhao, J. (2026). MAWC-Net: A Multi-Scale Attention Wavelet Convolutional Neural Network for Soil pH Prediction. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010054