Abstract

This study investigates the influence of manufacturing technology on the structural, mechanical, and antifriction properties of a new self-lubricating composite based on ShKh15 bearing-steel grinding waste to which a CaF2 solid lubricant was added. The developed process involves regenerating grinding waste, mixing with CaF2 powder, pressing, and sintering. This process ensures the formation of a micro-heterogeneous structure consisting of a metallic matrix with uniformly distributed CaF2 particles. The strengthening phases and their distribution determine the composite’s tribological behavior under operating conditions of 100–200 rpm and 1.0 MPa in air. Compared to conventional cast bronze, the material exhibits superior wear resistance and a lower friction coefficient. During friction, self-renewing antifriction films form on the contact surfaces due to chemical interactions between metallic elements, oxygen, and the solid lubricant, providing a continuous self-lubricating effect. The results demonstrate that adjusting the initial alloyed waste powders and the CaF2 content makes it possible to control the structure and performance of the composite. This research highlights the potential of using industrial grinding waste to produce efficient antifriction materials while reducing environmental impact.

1. Introduction

Recent trends in materials science and mechanical engineering emphasize the growing use of secondary metal raw materials to develop new, efficient, and economically viable materials. This approach not only reduces the environmental impact of metal waste but also creates broad opportunities for producing high-performance materials from low-cost recycled resources. Such materials play a crucial role in advancing sustainable and resource-efficient technologies.

Secondary metal raw materials typically include machining chips and scrap formed during the processing of cast or wrought parts. Technological methods for their reprocessing—mainly involving various melting techniques—have been known and applied in industries for decades [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. However, a specific type of metal waste, namely, grinding waste, has received little attention. This waste is generated during abrasive machining and contains a large proportion of embedded abrasive particles, complicating its reuse in conventional production cycles. As a result, grinding waste is commonly transported to landfills, representing an environmental and economic problem.

In recent years, several studies [8,9] have highlighted the potential of steel and non-ferrous alloy grinding waste as a valuable secondary raw material. Such waste contains many alloying elements—Cr, Mn, Ti, Al, W, V, Mo, Si, and others—and can be used to produce effective antifriction composite materials. Experimental research has shown promising results, including improved wear resistance and tribological properties of composites obtained from regenerated grinding waste [10,11]. These findings open the way for developing technologies for recycling and reusing such waste in the production of new antifriction materials.

The reliability and efficiency of modern machinery depend largely on the stable operation of friction units. The essential requirements for antifriction materials include a low coefficient of friction and high wear resistance, ensuring reduced energy loss and longer service life. Friction units—such as bearings, bushings, thrust rings, and seals—are exposed to diverse conditions: with or without lubrication and under varying loads, sliding speeds, and temperatures. This variability makes it impossible to create a universal antifriction material suitable for all applications.

A relevant example is stencil-printing equipment, where friction units are subjected to rotational speeds of up to 150 rpm and loads of up to 1.0 MPa in air. Bearings made of cast bronze or brass and lubricated with oil often exhibit insufficient performance—i.e., high friction coefficients or accelerated wear—especially when lubrication is limited or interrupted [12]. Furthermore, cast materials have inherent structural inhomogeneities resulting from segregation during solidification, reducing their durability and stability [13]. Powder and composite materials, by contrast, offer uniform structures and flexibility in tailoring composition [14,15]. However, their industrial use is constrained by the high cost of powders and processing equipment. Thus, combining technological efficiency with economic feasibility is an important goal.

This study focuses on the use of grinding waste as a low-cost raw material for producing new antifriction composites designed for friction units in stencil-printing machines. The objective was to determine the influence of technological synthesis parameters on the structure and properties of self-lubricating composites based on bearing-steel ShKh15 grinding waste supplemented with a CaF2 solid lubricant, intended for medium-duty operating conditions (up to 150 rpm and 1.0 MPa in air).

2. Experimental Procedure

2.1. Preparatory Procedures

The subject of study was a new antifriction composite based on ShKh15 steel grinding waste supplemented with a CaF2 solid lubricant (Table 1). ShKh15 steel is the closest analog to bearing steel 100Cr6 (1.3505) [1*] (CEN. EN ISO 683-17:2014—Heat-Treated Steels, Alloy Steels and Free-Cutting Steels—Part 17: Ball and Roller Bearing Steels. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2014) or bearing steel 52100 [2*] (AISI. AISI 1045 Steel—Carbon Steel, Medium Carbon. American Iron and Steel Institute: Washington, DC, USA).

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the composites based on ShKh15 steel grinding waste.

Structural bearing steels are intended for use in conditions involving friction and wear. Therefore, their wear resistance properties are among the important parameters considered when selecting the basis of materials for medium-heavy operating conditions [16,17]. The hypereutectoid amount of carbon and chromium in ShKh15 steel ensures the formation of a significant number of carbides with high hardness and wear resistance. Chromium, which is also present in the solid solution, increases the hardness and strength of ferrite [18,19,20].

Liquid lubricants become ineffective under friction conditions when they are subjected to increased loads and speeds, among other loading factors. Therefore, it is especially important to protect friction surfaces from increased wear and seizure. For this purpose, special substances are used, namely, solid lubricants. Among the many options for increasing the wear resistance of friction pairs through the use of solid lubricants, their introduction into the composition of sintered composite materials presents certain advantages. A solid lubricant ensures acquisition of the specified properties during the manufacturing process and their systematic reproduction during operation; it continuously restores the worn separation layer. This ensures the stability and durability of the friction unit, simplifies the bearing unit maintenance, etc. The literature on this issue [21,22,23,24] has clearly shown the promise of using calcium fluoride (CaF2) as a solid lubricant for the specified operating conditions.

Charge Preparation and Consolidation

ShKh15 bearing-steel waste powders are generated during various operations, including the processing of cast bearing blanks and the grinding of separators. This waste is contaminated with abrasive micro-chips and components of lubricating and cooling fluid (LCF), making it difficult to reuse and resulting in the disposal of a great deal of potential raw materials in landfills.

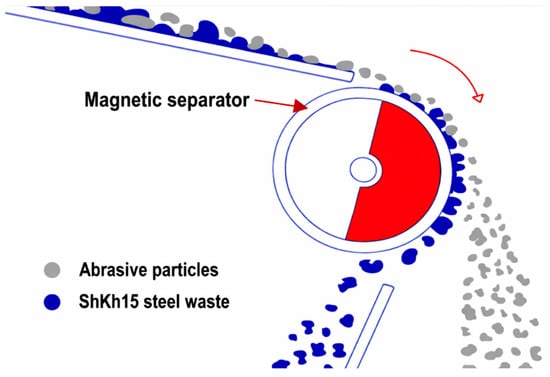

The magnetic separation method [8,11] was used to clean steel powders from abrasives using a magnetic separator (Figure 1). This approach allows waste to be cleaned at a rate of 10 kg/h. This cleaning process was performed twice to ensure maximum removal of abrasive particles. The proportion of abrasive crumb residue remaining after cleaning ranges up to 2%.

Figure 1.

Scheme of the magnetic separator.

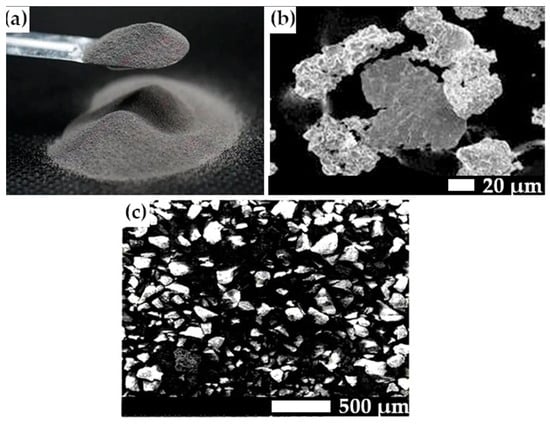

The ShKh15 steel powder free of abrasives after magnetic separation is shown in Figure 2a,b. The size of the cleaned ShKh15 steel waste particles is 0.02–0.14 mm.

Figure 2.

ShKh15 steel powder after magnetic separation: (a)—general view of the cleaned ShKh15 steel powder; (b)—ShKh15 steel particles; and (c)—separated abrasive particles after magnetic separation of grinding waste.

Magnetic separation is a process of separating a mixture of powders into magnetic and non-magnetic particles. This is achieved by exposing powdered metal waste contaminated with abrasives to a magnetic field. The method is based on the difference in the magnetic susceptibility of materials, i.e., how strongly they react to a magnetic field. Under the influence of a magnetic field, magnetic particles (steel powders) are attracted to the magnetic drum of the separator, while non-magnetic particles (abrasives) fall along a different trajectory into a special container and are disposed of. Abrasive particles are irregularly shaped fragments with smoothed edges resulting from the grinding of cast bearings, as shown in Figure 2c. Abrasive particles (Figure 2c) were collected after being removed from metal waste.

The components of the lubricating and cooling fluid can be removed by washing the grinding waste in tetrachloroethylene. This waste typically contains mineral oils, sodium salts, and other residues from machining. However, this procedure is not mandatory, since the resulting materials are intended for antifriction applications, and the presence of sodium, chlorine, and fluorine salts has been experimentally shown to enhance anti-seizure properties and wear resistance [9].

To reduce the amount of oxygen, a recovery annealing operation was applied to the ShKh15 steel waste powders in a hydrogen environment at temperatures of 850–1000 °C for 1.5–2.0 h. After these preparatory operations, the steel powders were sieved through sieve No. 0160. The CaF2 powders were dried at a temperature of 120 °C for 1 h and sieved through sieve No. 0125.

The main requirements for the technology used to manufacture materials for friction units are a simple and accessible technological process and the use of readily available raw materials, auxiliary materials, and equipment. Therefore, these requirements were considered when developing technological processes for the manufacture of new antifriction powder materials.

Charge components, namely, compositions consisting of steel waste powders with CaF2 additives, were mixed in a bank mixer into which small strips of nickel were cut to ensure better mixing. The amount of CaF2 to be added was within the range of 4–8 wt.%, since it is known [8,9,11] that the optimal content of CaF2 in composite metal antifriction materials is 10.0–20.0 vol.%, which corresponds to 4.0–8.0 wt.%. Adding calcium fluoride at a proportion less than 4.0 mass% will not allow realization of its lubricating function, and introducing more than 8.0–10.0 wt.% of fluoride leads to delamination of the briquettes during pressing. Pressing was carried out using a 125 t hydraulic press with a CNC system model T. 125 4C at loads of 700–900 MPa without lubricating the inner surface of the matrix and punches. The samples were sintered in a muffle furnace in a dried hydrogen environment (dew point = −40 °C) at temperatures of 1100–1150 °C for 2 h. The samples had a porosity of 10–11% after being sintered.

2.2. Examination Techniques

Structural studies of the composite material were performed using an Optika B1000 MET metallographic microscope, an EVO 50XVP scanning electron microscope (SEM), and X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). The tested material was analyzed using a Hitachi TM3000 scanning electron microscope (SEM) with an EDS system to identify chemical elements.

Chemical elemental analysis of the new composite was performed using a Metavision1008i optical emission spectrometer (Ukraine) with data-processing software capable of analyzing more than 55 elements, with low detection limits and a library for rapid identification and confirmation of material grades.

The mechanical properties of the new composites were determined via standard methods (according to 3*, 4* (CEN. EN ISO 2740:2009—Sintered Metal Materials, Excluding Hardmetals—Tensile Test Pieces. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2009), 5*) using standard equipment. A UIT GTM 500 testing machine (Ukraine) and a UIT HBW-1 stationary Brinell hardness tester (Ukraine) were used in this study. For different types of comparative tests, 20 samples of the studied composite and 20 samples of the bronze cast alloy CuSn8 (CW453K) were produced.

Tribological tests were performed according to standard methods (6* (ASTM International. ASTM D7264—Standard Test Method for Flexural Properties of Polymer Matrix Composite Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA.), 7* (ISO. ISO 6506—Metallic Materials—Brinell Hardness Test. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland), 8* (ASTM International. ASTM E10—Standard Test Method for Brinell Hardness of Metallic Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA)). Friction and wear tests were carried out according to the end-friction scheme with a 5 km friction track using a VMT-1 friction machine under the following conditions: the rotation speed was 100–150 rpm, the load was up to 1.0 MPa in air, and the counterface was made of R18 steel, which is analogous to tool high-speed steel 1.3355 (9* (DIN. DIN 1.3355—High-Speed Steel (Equivalent to AISI T1). Deutsches Institut für Normung: Berlin, Germany)) or T1 steel (10* (ASTM International. ASTM A600/A600M—Standard Specification for Tool Steel High-Speed. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA), hardness 54–56 HRC). R18 steel corresponds to the material of the actual counterpart in the friction unit of a stencil-printing machine. The chemical composition of R18 steel is as follows: wt.%: 0.73–0.83 carbon; 0.20–0.50 silicon; 0.20–0.50 manganese; 3.80–4.40 chromium; 17.00–18.50 tungsten; 1.00–1.40 vanadium to 0.03 sulfur and 0.03 phosphorus; and iron as the base.

3. Experimental Results and Discussion

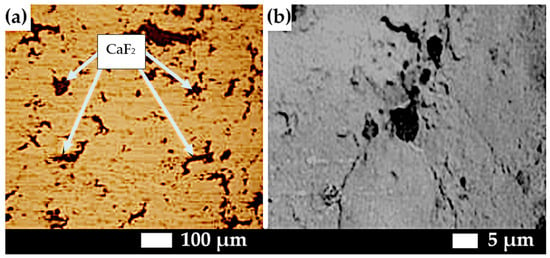

After sintering of the composite in the ShKh15 steel grinding waste–CaF2 system, the resulting material consisted of a metallic matrix in which CaF2 solid lubricant particles were uniformly distributed (Figure 3). The optical micrograph in Figure 3a shows that the CaF2 phase is finely and evenly dispersed throughout the steel matrix, forming small globular and irregular inclusions mainly located along the grain boundaries. This uniform distribution of the solid lubricant ensures effective formation of a lubricating film during friction, helping to reduce wear and seizure.

Figure 3.

Microstructure of the composite based on ShKh15 + 5%CaF2 waste: (a)—unetched section; (b)—CaF2 between grains of the metal matrix.

The SEM image (Figure 3b) confirms the homogeneous structure of the composite and reveals a strong interfacial bond between the metal matrix and CaF2 particles. No pores or cracks are visible at the interface, indicating that the chosen sintering parameters provided sufficient densification of the composite. Such a microstructure promotes stable tribological behavior under medium-load operating conditions, as the uniformly distributed CaF2 is gradually released to the surface during friction, ensuring continuous lubrication and minimizing adhesive wear.

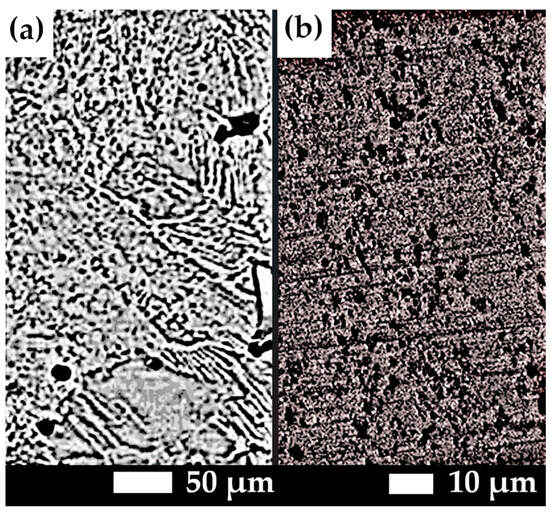

In turn, the metal matrix of the material has a pearlite structure (Figure 4a), and the carbide phase is represented by cementite inclusions.

Figure 4.

Fragment of the pearlite phase in the composite structure (a). Carbides in the structure of the metal matrix (b).

As microstructural studies have shown, carbides are fairly evenly distributed within the metallic matrix (Figure 4b and Figure 5a), preventing the negative phenomenon known as carbide liquation. This uniformity results from the specific features of the matrix formation, which develop from individual metallic particles of purified ShKh15 steel powder. It is well established [21,22] that the influence of alloying elements on a material’s characteristics depends strongly on the method through which they are introduced. For example, chromium tends to form a highly heterogeneous, coarse structure when added as a pure powder during composite fabrication [21,22,25,26]. This behavior is a product of the slow dissolution of chromium in the iron matrix due to its strong tendency to oxidize and form carbides. Moreover, the use of pure Cr powder (especially in large quantities) can cause dimensional growth of samples during sintering, as chromium readily reacts with oxygen. These factors significantly complicate the production of composites containing pure chromium powders, requiring additional protective measures against oxidation and excessive carbide formation (e.g., the inability to use endogas atmospheres) and subsequent mechanical machining of oversized parts.

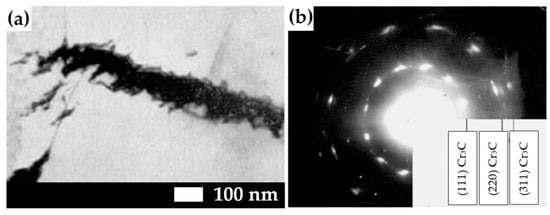

Figure 5.

Cr3C carbides in the surface layer of the composite ShKh15 + 5%CaF2 after tribological testing: (a)—thin foil; (b)—Cr3C carbide electronogram.

In contrast, using alloyed powders ensures the formation of a more homogeneous structure. According to [21,22,27,28,29], the mechanical properties of chromium steels produced from pre-alloyed powders are superior to those obtained through the mechanical mixing of individual components: the plasticity of steels made from pre-alloyed powders is 3–4 times higher than that of steels produced from heterogeneous powder mixtures. Therefore, the presence of chromium in ShKh15 steel waste powders inherently eliminates the negative phenomena described above during composite manufacturing.

Upon cooling from sintering temperatures corresponding to homogenizing annealing conditions, a more uniform distribution of carbides is achieved, which also reduces carbide banding, even at the microstructural level of the metallic matrix. The uniform dispersion of carbides contributes to the preservation of fine grains, thereby improving the physical and mechanical properties of the composite.

The electron micrograph in Figure 4b reveals clusters of small, densely packed carbides, some of which exhibit an elongated morphology aligned in specific directions (Figure 5a). It is known [17,23,30,31,32] that ShKh15 bearing steel is a hypereutectoid structural steel characterized by high hardness and wear resistance. Conventionally, the cast steel is subjected to hardening at 800–880 °C followed by low-temperature tempering at 150–160 °C, resulting in a hardness of HRC 62–65 and a structure composed of fine, uniformly distributed excess carbides within a martensitic matrix.

The composite structure formed based on regenerated ShKh15 steel grinding waste with a CaF2 solid lubricant exhibited remarkable mechanical and antifriction properties compared to cast tin bronze CuSn8 (CW453K), [11*], which is often used in stencil-printing and UV-varnishing machines JB-750II, JB-960II (JINBAO Machinery Co., Ltd., Wenzhou, China). Samples of the new composite and cast bronze CuSn8 (CW453K) were tested under the same conditions to determine comparative characteristics (Table 2).

Table 2.

Properties of composite based on ShKh15 steel grinding waste.

As shown in Table 2, the new composite has sufficiently high mechanical properties and is inferior to cast bronze only in terms of impact toughness. This is due to the porosity of the composite as well as the presence of the non-plastic CaF2 solid lubricant in the new material. However, critically, the actual friction assembly is not subject to external impact loads during the operation of the stencil machine. Therefore, in this case, the composite’s reduced impact toughness is not a decisive factor.

At the same time, the ShKh15 + (4–8)%CaF2 composite significantly exceeds cast bronze in terms of antifriction properties under tribological test conditions at P = 1.0 MPa and V = 100–150 rpm in air without liquid lubrication (Table 2). This behavior is explained by the presence of the CaF2 solid lubricant in the composite, unlike the case for CuSn8 cast bronze. The CaF2 solid lubricant is spread on contact surfaces during friction, forming a protective antifriction film together with other elements of the friction pair and preventing intensive wear. The friction coefficient and wear intensity of the new composite significantly increase when the speed increases to V = 200 rpm (Table 2). At the same time, tests of samples made from CuSn8 cast bronze showed that it became completely inoperable when the speed increased to 200 rpm.

As mentioned above, the carbide phase is of the cementite type in the metal matrix of the ShKh15-waste-based composite. These phases are primarily the main chromium carbide Cr3C (Figure 5a), detected via electron microdiffraction (Figure 5b), and alloyed cementite of the (Fe,Cr)3C type, as opposed to the usual Fe3C cementite formed in carbon steels.

The behavior of the material’s strengthening phases after a load was applied during tribological tests turned out to be interesting, as shown in Figure 5. We removed the surface layer via electropolishing after testing for friction and wear under increased loads, and a thin foil was prepared from this surface. Figure 5a clearly shows the release of Cr3C-type carbide particles. Although the microphotograph does not clearly reveal individual dislocations, the structural features observed around the carbides may indicate regions of localized deformation caused by stress concentration. Such areas are typically sources of dislocation and contribute to the overall strain hardening of the composite during tribological loading. The appearance of dislocations and local strain fields increases resistance to plastic deformation, thereby strengthening the material and improving the antifriction composite’s wear resistance. This also ensures a long service life, especially at high rotational speeds and under high loads. In addition, another positive structural factor is the absence of carbide segregation (‘striping’) in the ShKh15 + 5% CaF2 composite material, a feature characteristic of cast ShKh15 steel. This absence results from the initial dispersity of ShKh15 steel waste particles. In other words, each particle of ShKh15 steel powder is essentially a micro-ingot, where carbide segregation is absent.

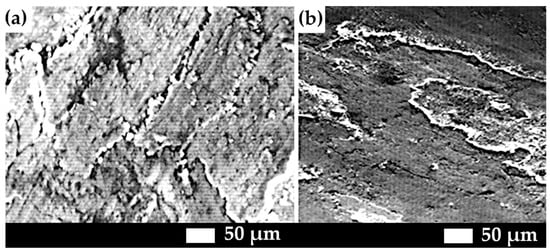

Anti-seize films formed on the contact surfaces of the ShKh15 + 5% CaF2 composite during tribological testing (Figure 6). These films ensured the existence of strong antifriction properties (Table 2) and a permanent self-lubrication mode. Our studies showed that such films evenly cover the contact surface (Figure 7a) and protect the friction pair from intense wear. Friction occurred through a mechanism of simultaneous wear and regeneration of the film at V = 100–150 rpm and loads up to 1.0 MPa in air. With deformation, microcracks appear first in the film (Figure 7b), initiating local delamination and the removal of small wear particles from the contact zone. Simultaneously, new anti-seize film layers form on the exposed areas, creating a continuous self-regeneration process during operation.

Figure 6.

Friction film on the surface of the ShKh15+ 5% CaF2 composite sample (a) and the counterface (b) after tribological tests at V = 150 rpm and P = 1.0 MPa.

Figure 7.

General view of a continuous friction film on the surface of the ShKh15+ 5% CaF2 composite sample (a) after tribological tests at V = 100–150 rpm and P = 1.0 MPa (cross-section). (b) Appearance of microcracks and the beginning of film delamination (indicated by arrows).

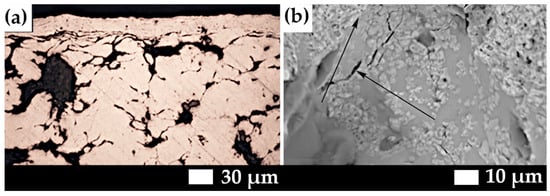

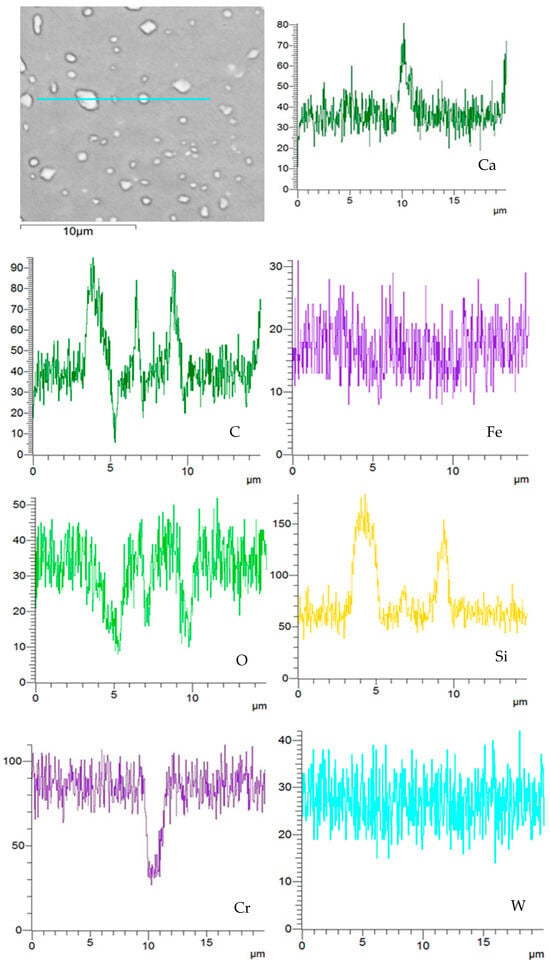

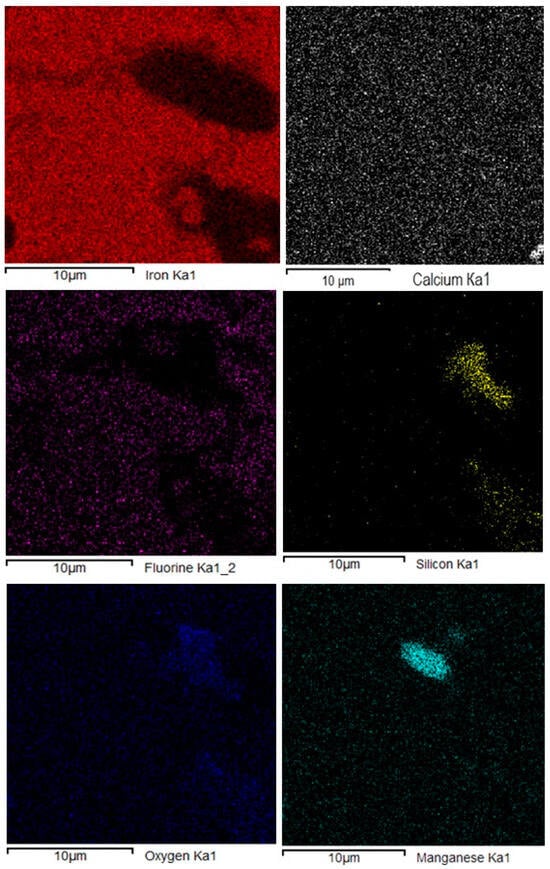

During the experiments, spectral analysis was performed by scanning along the surface film of the composite (Figure 8) to determine the presence and distribution of chemical elements that participate in the formation of antifriction films, and maps of the distribution of chemical elements were obtained (Figure 9).

Figure 8.

Spectrograms (EDS signal intensity) of antifriction self-lubricating film elements after subjection to tribological tests at V = 100–150 rpm and P = 1.0 MPa; linear scanning; battery voltage—15.0 kV; process time—5 s; line resolution—512 pixels; line length—20.0 μm. Blue line – line scan path used for elemental analysi.

Figure 9.

Distribution maps of elements in the anti-friction film after the tests (V = 100–150 rpm, P = 1.0 MPa) in analysis mode: battery voltage—15.0 kV; process time—5 s; resolution—512 × 512 pixels; revised resolution—50%; image width—21.0 μm.

Figure 8 and Figure 9 show the composite’s constituent chemical elements, as well as elements originating from the R18 steel counterface, within the antifriction films. Oxygen was also detected in the antifriction films. Its presence, typical of an open tribological system, indicates the oxidative nature of the wear process, which is accompanied by the formation of alloying-type oxides.

Analysis of the data presented in Figure 9 demonstrates that the components of the composite—such as the CaF2 solid lubricant, whose presence was confirmed by the fluorine distribution—together with other elements, are uniformly dispersed across the friction surface. Silicon exhibits some localized accumulations, likely due to its “dual” origin, stemming both from the tested composite and from the R18 steel counterface.

The generally uniform distribution of the tribofilm components (Figure 8 and Figure 9) contributed to the favorable tribological performance of the composite based on ShKh15 steel grinding waste, resulting in strong antifriction properties at rotation speeds of V = 100–150 rpm and under loads of P = 1.0 MPa (Table 2).

The combined effect of rotational speed and load in the presence of oxygen enhances adsorption phenomena in the antifriction film, leading to its dispersion and increased plasticity. As a result, a smooth and continuous surface layer develops under conditions of V = 100–150 rpm and P = 1.0 MPa. This self-regenerating anti-seize film gives rise to a permanent self-lubricating mode, as confirmed by the composite’s high antifriction performance (Table 2). Such tribological behavior represents a form of system self-organization, where dissipative structures and protective films emerge under the influence of complex physicochemical interactions between metallic and nonmetallic components, oxygen, and the solid lubricant. The most influential factor governing these processes is the intensity of external energy acting on the system [33]. The development of bifurcation behavior in the film depends on the type and magnitude of this energy [34,35,36]. In other words, the system may evolve toward two attractors: either a stable, low-wear friction regime or a high-wear regime leading to surface seizure. The results of the experiment confirm this behavior: increasing the sliding speed to V = 200 rpm caused the friction films to lose their lubricating function, turning into an abrasive layer and leading to higher friction and wear rates (Table 2).

In contrast, CuSn8 cast bronze exhibits a fundamentally different tribological response. Without lubrication, bronze cannot form a protective film on the contact surfaces, and while it maintains limited tribological performance at 100–150 rpm, increasing the speed to 200 rpm leads to jamming, seizure, and complete adhesion of the friction pair. Thus, cast bronze becomes inoperable under dry friction conditions.

4. Conclusions

- For the first time, we have demonstrated the effective use of ShKh15 industrial steel grinding waste to create a new antifriction composite operating in self-lubricating mode. This was achieved via a newly developed production technique that includes regenerating ShKh15 steel waste powders, preparing the initial mixture with the addition of a CaF2 solid lubricant, pressing, and sintering. The application of the developed technology made it possible to obtain a composite with stronger properties than cast bronze, which is traditionally used under similar operating conditions. Therefore, the developed antifriction composite based on recycled ShKh15 steel waste with CaF2 additives can be recommended for use in friction units in screen-printing machine sections for UV varnishing as an alternative to traditional cast bronze bushings.

- The experimental results show that the proposed manufacturing technique enables the formation of a heterophase structure in antifriction composites based on ShKh15 steel waste with CaF2 solid lubricant additives. This structure ensures a high level of antifriction performance in self-lubricating mode under rotation speeds of 100–150 rpm and loads of up to 1.0 MPa in air.

- The results of spectral analysis and element distribution maps showed the presence of the composite’s chemical elements and the R18 steel counterface’s elements in the antifriction films, and oxygen was also observed in the friction films. The presence of oxygen in the friction film, as in an open system, indicates the oxidative nature of wear, which is accompanied by the formation of oxides of alloying elements.

- Tribological tests showed that, under the mentioned operating conditions, the surfaces of both the composite and the counterface became covered with continuous anti-seize films formed during friction. These films maintain a stable self-lubrication regime, resulting in high antifriction properties and reduced wear. It was established that the most influential factors affecting the performance of the new antifriction composite are the type and intensity of the external energy applied to the system. Increasing the rotation speed to 200 rpm caused the formation of a discontinuous film, leading to higher friction coefficients and increased wear rates.

- Further research will focus on in-depth microstructural and X-ray diffraction studies, electron microscopy analysis of friction films, the phase compositions of friction films of a new anti-friction composite based on regenerated ShKh15 steel grinding waste, and the influence of individual phases on the composite’s tribological properties. In addition, we plan to expand work on the use of grinding waste, not only from steels but also from non-ferrous metals such as bronze and brass to create new composites.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.R., M.Z., O.G. and I.M.; methodology, T.R., M.Z., O.G. and I.M.; validation, T.R., M.Z., O.G. and I.M.; formal analysis, T.R., M.B. and K.J.; investigation, T.R., M.Z., O.G. and I.M.; resources, T.R., M.Z., O.G. and I.M.; data curation, T.R., M.Z., O.G. and I.M.; writing—original draft preparation, T.R., M.Z., O.G. and I.M.; writing—review and editing, T.R., M.B. and K.J.; visualization, T.R., M.Z., O.G. and I.M.; supervision, T.R., M.B. and K.J.; project administration, M.B. and K.J.; funding acquisition, M.B. and K.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No data are associated with this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhou, B.; Yang, Y.; Reuter, M.A.; Boin, U.M.J. Modelling of Aluminium Scrap Melting in a Rotary Furnace. Min. Eng. 2006, 19, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuzzi, S.; Timelli, G. Preparation and Melting of Scrap in Aluminum Recycling: A Review. Metals 2018, 8, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Xu, A.; Yang, G.; Wang, H. Analyses and Calculation of Steel Scrap Melting in a Multifunctional Hot Metal Ladle. Steel Res. Int. 2019, 90, 1800435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Zhu, R.; Tang, T.; Dong, K. Study on the Melting Characteristics of Steel Scrap in Molten Steel. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2019, 46, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penz, F.M.; Schenk, J. A Review of Steel Scrap Melting in Molten Iron-Carbon Melts. Steel Res. Int. 2019, 90, 1900124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Nian, Y.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, Z. Steel Scrap Yield Prediction in Basic Oxygen Steelmaking Based on Random Forest and Neural Networks. Steel Res. Int. 2025, 96, 2400713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, J.; Wang, H. Intelligent Proportioning Model of Converter Scrap Based on Optimization Algorithm. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2024, 34, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roik, T.; Rashedi, A.; Khanam, T.; Chaubey, A.; Balaganesan, G.; Ali, S. Structure and Properties of New Antifriction Composites Based on Tool Steel Grinding Waste. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roik, T.; Gavrysh, O.; Rashedi, A.; Khanam, T.; Raza, A.; Jeong, B. New Antifriction Composites for Printing Machines Based on Tool Steel Grinding Waste. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemlik, M.; Roik, T.; Gavrish, O.; Jamroziak, K. Using Silumin Grinding Waste for New Self-Lubricating Antifriction Composites. Adv. Sci. Technol. Res. J. 2025, 19, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roik, T.A.; Gavrysh, O.A.; Vitsiuk, I.I. Tribotechnical Properties of Composite Materials Produced from ShKh15SG Steel Grinding Waste. Powder Metall. Met. Ceram. 2019, 58, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirsöz, R. Wear Behavior of Bronze vs. 100Cr6 Friction Pairs under Different Lubrication Conditions for Bearing Applications. Lubricants 2022, 10, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, I.; Davis, C.; Li, Z. Effects of Residual Elements during the Casting Process of Steel Production: A Critical Review. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2021, 48, 712–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oro, R.; Campos, M.; Gierl-Mayer, C.; Danninger, H.; Torralba, J.M. New Alloying Systems for Sintered Steels: Critical Aspects of Sintering Behavior. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2015, 46, 1349–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruzhanov, V.S. Modern Manufacturing of Powder-Metallurgical Products with High Density and Performance by Press–Sinter Technology. Powder Metall. Met. Ceram. 2018, 57, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nykyforchyn, H.; Kyryliv, V.; Maksymiv, O. Wear Resistance of Steels with Surface Nanocrystalline Structure Generated by Mechanical-Pulse Treatment. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadeshia, H.K.D.H. Steels for Bearings. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2012, 57, 268–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białobrzeska, B. Effect of Boron Accompanied by Chromium, Vanadium and Titanium on Kinetics of Austenite Grain Growth. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2021, 48, 649–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białobrzeska, B. Effect of Alloying Additives and Microadditives on Hardenability Increase Caused by Action of Boron. Metals 2021, 11, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białobrzeska, B. The Influence of Boron on the Resistance to Abrasion of Quenched Low-Alloy Steels. Wear 2022, 500–501, 204345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, W.B. Powder Metallurgy Methods and Applications. In Powder Metallurgy; ASM International: Almere, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kurzawa, A.; Stachowicz, M.; Roszak, M.; Roik, T.; Gavrysh, O.; Maistrenko, I.; Jamroziak, K.; Bocian, M.; Lesiuk, G. New Anti-Friction Self-Lubricating Composite Based on EP975 Nickel Alloy Powder with CaF2 Solid Lubricant—Thermal and Dilatometric Behavior. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 119, 326–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, B. Tribology Handbook; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995; ISBN 9780750611985. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Guo, N.; Ji, L.; Xu, C. Synthesis of CaF2 Nanoparticles Coated by SiO2 for Improved Al2O3/TiC Self-Lubricating Ceramic Composites. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; You, B.; Wu, Y.; Liang, B.; Gao, X.; Li, W.; Wei, Q. Effect of Cr, Mo, and V Elements on the Microstructure and Thermal Fatigue Properties of the Chromium Hot-Work Steels Processed by Selective Laser Melting. Metals 2022, 12, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Choi, P.-P.; Inden, G.; Prahl, U.; Raabe, D.; Bleck, W. On the Spheroidized Carbide Dissolution and Elemental Partitioning in High Carbon Bearing Steel 100Cr6. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2014, 45, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M. Metal Powder for Additive Manufacturing. JOM 2015, 67, 536–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Sandström, R. Fe–Mn–Si Master Alloy Steel by Powder Metallurgy Processing. J. Alloys Compd. 2004, 363, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinchuk, S.Y.; Vnukov, O.O.; Kushnir, Y.O.; Roslyk, I.G. Improvement of the Operational Properties of Sintered Copper Steel Through the Use of an Efficient Alloying Method. Sci. Innov. 2020, 16, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, C.H.; Phelps, N.; Maguire, T.L.D.E. Bearings and Applied Technology. In Manual of Engineering Drawing; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 315–330. [Google Scholar]

- Childs, P.R.N. Rolling Element Bearings. In Mechanical Design Engineering Handbook; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 231–294. [Google Scholar]

- Childs, P.R.N. Journal Bearings. In Mechanical Design Engineering Handbook; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 167–230. [Google Scholar]

- Orlik, M. Self-Organization in Electrochemical Systems II; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; ISBN 978-3-642-27626-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, J. Attractors in Dynamical Systems. In Ergodic Dynamics: From Basic Theory to Applications; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ize, J. Introduction to Bifurcation Theory. In Differential Equations: Proceedings of the 1st Latin American School of Differential Equations, Held at São Paulo, Brazil, June 29–17 July 1981; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1982; pp. 145–202. [Google Scholar]

- Haragus, M.; Iooss, G. Local Bifurcations, Center Manifolds, and Normal Forms in Infinite-Dimensional Dynamical Systems; Springer: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-0-85729-111-0. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.