Abstract

This study addressed the issue of insufficient lubrication in the thrust washer of the planetary gear reducer during operation. Numerical simulations were performed under fixed operating conditions, combined with sequential optimization strategy, to systematically investigate the influence of V-shaped texture distribution and geometric parameters on lubrication characteristics during unidirectional rotation. The results revealed that, under the examined texture parameters, the oil film pressure increased significantly with increasing radial velocity from inner to outer radius and lubricant viscosity, with area density being the key parameter influencing load-carrying capacity. Moreover, selectively enhancing the texture density in the outer ring region effectively alleviated wear caused by stress concentration in that area. The optimal V-shaped texture parameters were determined as follows: a length ratio of 5, an angle of 30°, an area density of 24.52%, and a depth of 0.02 mm. The symmetry axis of the texture was oriented opposite to the fluid velocity, and the texture distribution exhibited radial densification. This study will inform the design of surface textures and enhance the lubrication performance of mechanical components in thrust washers and similar rotational operating conditions.

1. Introduction

Planetary gear reducers are widely used in various mechanical transmission systems due to their compact size, high reduction ratio, high transmission efficiency, low vibration, and stable operation [1,2]. The thrust washers on both sides of the planetary gears effectively prevent axial movement of the needle rollers within the gear assembly. Their operational stability and functional reliability significantly impact the performance of mechanical systems. During the operation of the planetary gear reducer, the thrust washer suffers from insufficient lubrication. Analysis of wear mechanisms and lubrication patterns, coupled with surface topography observations, indicates inadequate lubrication of the thrust washer. This leads to localized direct contact between friction surfaces, which is the primary cause of accelerated wear and premature failure of the thrust washer during operation, severely impacting the performance and service life of the planetary gear reducer. Therefore, it is necessary to optimize the surface design of the thrust washer under existing operating conditions. This optimization aims to enhance lubrication performance, improve friction and wear conditions, and ultimately increase operational reliability.

Previous studies have demonstrated that manufacturing appropriate surface textures on component surfaces can enhance the lubricating performance of fluid lubricants [3,4]. Surface texture is a method that enhances the lubricating properties of sliding surfaces by machining patterns of recessed areas between relative sliding surfaces [5]. As a surface technology in the field of tribology, it serves functions such as trapping abrasive particles to reduce wear, improving dry friction conditions in friction pairs, and storing and releasing lubricants to prevent lubricant starvation under hydrodynamic and mixed lubrication conditions [6]. When lubrication on thrust washer surfaces is insufficient, surface texture enables secondary lubrication by releasing stored lubricant while simultaneously trapping abrasive particles to mitigate wear and reduce friction [7]. Extensive research demonstrates that its effectiveness is influenced by key parameters including texture shape [8,9], distribution [10,11], size (depth [12,13,14] and diameter [15,16]), area density [17,18], and orientation [19].

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) is widely used to study the lubrication mechanisms of surface texturing due to its advantages of efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and repeatability. With the rapid development of computing technology, numerical simulation has become an essential tool in tribological research. Therefore, in this study, a three-dimensional numerical model of the thrust washer flow field was established using ANSYS Fluent2023R2. The lubrication performance is evaluated based on the oil film load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient, allowing for the analysis of the influence of texture parameters on lubrication performance.

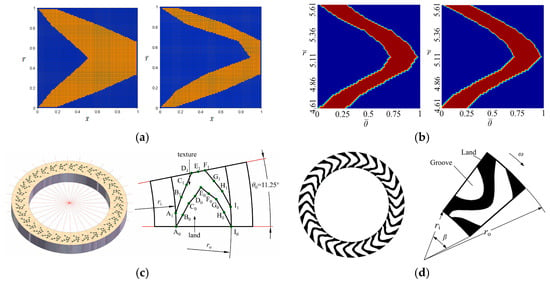

Existing research has shown that V-shaped textures, compared to conventional shapes such as triangular, circular, and square, offer superior load-carrying capacity and lower friction coefficient under unidirectional sliding conditions. Shen [20] used a sequential quadratic programming numerical optimization method and determined that the V-shaped texture provided the highest load-carrying capacity under unidirectional sliding (Figure 1a). Wang [21,22] obtained the globally optimal V-shaped configuration for oil film load-carrying capacity through algorithm optimization, experimentally verifying the theoretical findings. The optimized texture achieved a lower friction coefficient (Figure 1b). Costa [23] compared the oil film thicknesses of circular, V-shaped, and grooved textures under fluid lubrication, finding that the V-shaped texture provided the highest oil film thickness. Shen [24] employed CFD to examine the effects of geometric parameters and texture distribution patterns on lubrication performance. The use of the V-shaped texture on the thrust bearing with a shape similar to the thrust washer can also achieve superior lubrication performance. Li [10] employed a hybrid genetic algorithm-sequential quadratic programming approach to determine the globally optimal solution for V-shaped texture distribution in the thrust bearing. By comparing the load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient of V-shaped and circular textures, the numerical optimization model was validated through experiments. Results indicated that the V-shaped texture exhibited superior lubrication performance (Figure 1c). Tu [25] solved the Reynolds equation with JFO cavitation boundary conditions to obtain the optimal texture shape for the parallel thrust bearing, concluding that the best shape for load-carrying capacity was V-shaped. Based on the aforementioned research findings, this paper intends to continue the research path on V-shaped texture, further analyzing the influence of its distribution and geometric parameters on the lubrication performance of the thrust washer (Figure 1d).

Figure 1.

V-shaped texture shape and distribution. (a) Optimization results at different surface densities [20]. (b) Optimization results at different rotational speeds [21]. (c) Texture distribution and optimization parameters [10]. (d) Optimization result [25].

Existing research has confirmed that surface V-shaped texture effectively enhances the hydrodynamic properties of lubricants. However, its specific optimization effect largely depends on the selection of texture parameters. Optimal texture parameters are closely related to the contact type of the friction pair and operating conditions. Studies indicate that no universal parameter selection exists that can be applied to all operating conditions [26]. Therefore, to achieve optimal lubrication performance, it is essential to analyze the influence of surface texture parameters and their distribution on lubrication characteristics based on the specific dimensions and operating conditions of the thrust washer. This study focuses on the thrust washer within the planetary gear reducer, characterized by an inner diameter of 4.2 mm, an outer diameter of 12 mm, and a thickness of 0.4 mm. This study aims to derive optimal texture design solutions for this specific friction pair through an in-depth analysis of its lubrication characteristics, thereby providing theoretical foundations and practical references for optimizing the lubrication performance of similar friction pairs.

This study utilizes CFD to investigate the effects of key parameters such as the orientation, distribution, depth, area density, length ratio, and angle of V-shaped texture on the lubrication performance of the thrust washer in the planetary gear reducer under unidirectional rotation. In addition, this study explores the influence of rotational speed and temperature on the lubrication performance with the optimal texture parameters. The research aims to determine the optimal texture parameter combination within the dimensional constraints of the thrust washer, providing the theoretical foundation and practical guidance for the surface texture design of the thrust washer.

2. Establishment of Simulation Models

2.1. Geometric Models

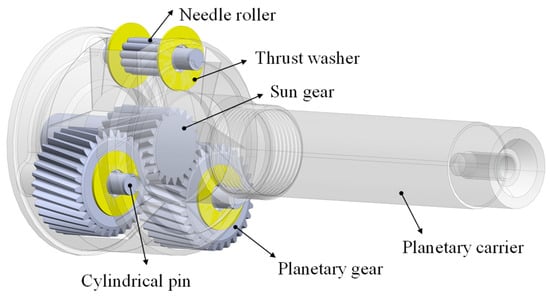

As illustrated in Figure 2, the thrust washer is positioned between the planetary gear and the planetary carrier. Its primary function is to prevent axial movement of the needle rollers within the planetary gears, while also reducing sliding friction between the planetary gear and the carrier, thereby mitigating wear.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of thrust washer installation position.

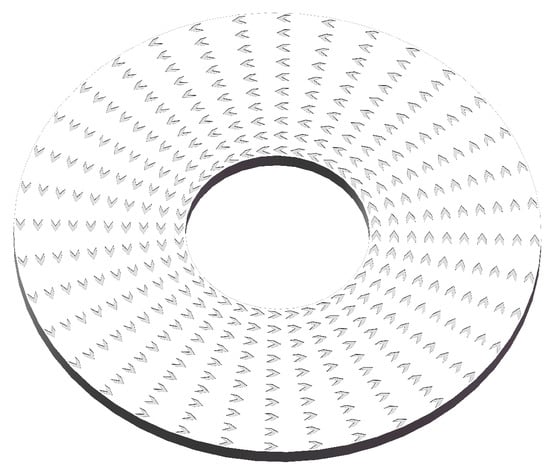

The three-dimensional model of the thrust washer surface after V-shaped texturing is shown in Figure 3. The inner diameter, outer diameter, and thickness of the thrust washer are 4.2 mm, 12 mm, and 0.4 mm, respectively.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the surface texture of the thrust washer.

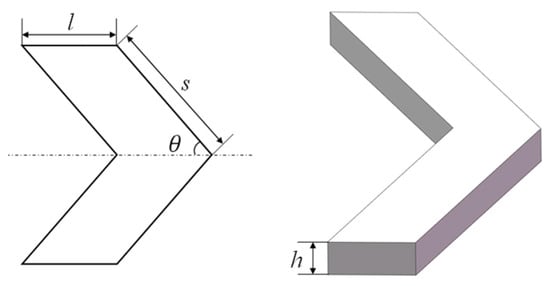

The shape and geometric dimensions of the V-shaped texture are depicted in Figure 4, where , , , and represent the width, oblique side, angle, and depth of the V-shaped texture, respectively. In the three-dimensional fluid model, the oil film thickness is set to 8 μm. The formulas for calculating the area of a single texture and the texture area density are as follows:

where and denote the inner and outer diameters of the thrust washer, respectively, and represents the number of texture units within one cycle of the thrust washer.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the V-shaped texture.

The geometric and operating parameters of the texture are listed in Table 1. The texture width, oblique side length, and angle correspond to , , and in Figure 4, respectively. The texture orientation refers to the angle between the texture symmetry axis and the flow velocity.

Table 1.

Geometrical dimensions and operating condition parameters of surface texture.

2.2. Governing Equations

The Navier–Stokes (N-S) equations are fundamental equations describing the motion of viscous fluids, widely applied to solve various problems in fluid mechanics. In this study, the lubricant is assumed to be an incompressible Newtonian fluid with constant density and dynamic viscosity of 876 kg/m3 and 0.0125 Pa·s, respectively. In the numerical simulation, the upper wall surface of the fluid domain is set as the stationary wall, while the lower wall rotates at a constant angular velocity of 1000 rpm about the z-axis, which is the thrust washer axis. Thus, the maximum linear velocity is 0.62832 m/s. The Reynolds number is calculated using Equation (3) to assess the flow state of the lubricant and determine the computational model as follows:

where is the density of the lubricant, denotes the fluid velocity, is the characteristic length of the fluid, and is the dynamic viscosity of the lubricant. The Reynolds number calculated is much smaller than 2000, indicating that the turbulence effects in the fluid flow within the lubrication system can be neglected [27]. Therefore, a laminar flow model is used for the simulation. This study employs the N-S equations and the continuity equation to calculate the lubrication characteristics of the lubricant:

where is the time, is the velocity vector, is the force vector per unit volume, and is the fluid pressure.

2.3. Lubrication Performance Evaluation Parameters

To comprehensively evaluate the impact of surface texture on the lubrication characteristics of the thrust washer, this study selects oil film load-carrying capacity and the friction coefficient as the core analysis parameters. The friction coefficient is defined as the ratio of the frictional force to the oil film load-carrying capacity. The oil film load-carrying capacity refers to the normal load supported by the lubricant film on the friction pair, while the frictional force represents the tangential resistance between the oil film and the moving surface. The calculation formula is as follows:

where represents the load-carrying capacity, represents the friction force, represents the friction coefficient, and are the pressure and shear stress at position on the surface of the lubricant.

Since the thrust washer primarily experiences stress concentration and the analysis indicates that the friction coefficient remains at a relatively low level in this study, when the oil film load-carrying capacity and the friction coefficient cannot both reach optimal levels, the oil film load-carrying capacity is selected as the criterion for determining the optimal texture parameters.

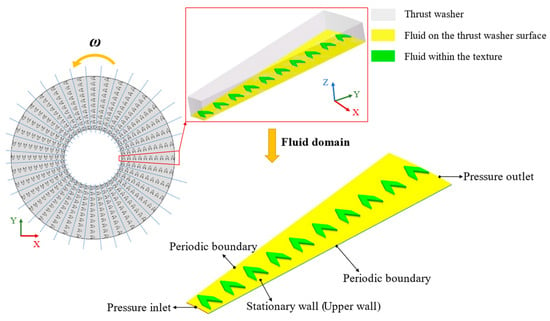

2.4. Verification of Computational Model and Mesh Independence

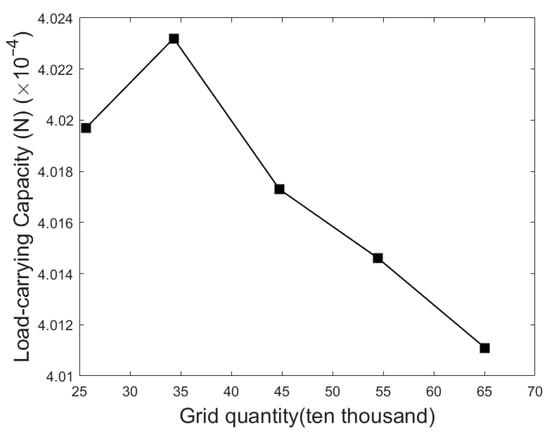

The flow field model of the textured surface is ring-shaped, with the texture units distributed periodically. The inner and outer diameters of the washer are 2.1 mm and 6 mm, respectively. To reduce computational time and minimize edge effects as much as possible, periodic boundary conditions are applied in the simulation; 1/36 of the model is used as the computational domain. The fluid domain is modeled using SolidWorks 2021 and the mesh is generated using Fluent Meshing, employing structured hexahedral elements. The overall grid size is 8 μm, with the texture grid refined to 6 μm. The overall oil film is set to four layers, while the texture oil film thickness adjusts the number of layers based on the texture depth. Due to significant variations in the rotational wall velocity, a five-layer boundary layer is applied near the wall where the texture is present. The y+ value near the wall is 0.608, satisfying the boundary layer resolution requirement at low Reynolds numbers. The average element quality is 0.51, with a maximum aspect ratio of 18.49. Due to the presence of boundary layers, the aspect ratio tolerance can be relaxed to less than 100. The maximum skewness is 0.88, which satisfies the requirement of being below 0.9. The minimum orthogonality quality is 0.53, exceeding the required threshold of 0.01. The variation in oil film load-carrying capacity as the number of mesh elements increases from 250,000 to 650,000, under fixed operating conditions and texture parameters is shown in Figure 5, where the difference in oil film load-carrying capacity between 450,000 and 550,000 meshes is only 0.067%. Therefore, a mesh count of 450,000 is adopted in this study.

Figure 5.

The influence of mesh density on the load-carrying capacity of the oil film.

2.5. Boundary Conditions and Solution Parameter Settings

Since the lubricant fluid is directly connected to the atmosphere at both ends, the inner and outer circumferential surfaces of the fluid domain are defined as pressure inlet and pressure outlet boundary conditions, with the pressure value set to atmospheric pressure. The two radial side surfaces are treated as periodic boundary conditions. The upper wall of the fluid domain is set as a stationary wall, while the lower wall is defined as a moving wall rotating around the z-axis with a speed of 1000 rpm. The boundary conditions are illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Boundary condition settings for the fluid domain.

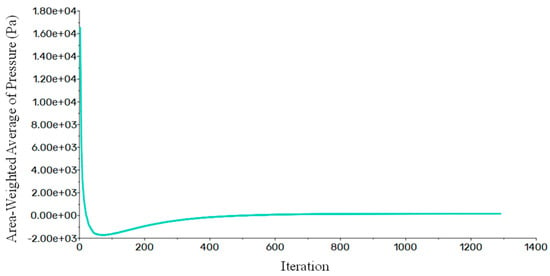

The pressure–velocity coupling algorithm used is SIMPLE, with the pressure discretization scheme set to Second Order, the gradient discretization scheme to Least Squares Cell-Based, and the momentum discretization scheme to Second Order Upwind. To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the numerical calculations, the residuals are set to 10−6. The average pressure iteration curve for the rotating wall is shown in Figure 7, where it can be observed that good convergence is achieved. Cavitation occurs when the pressure falls below the set cavitation pressure [28]. However, analysis indicates that the minimum absolute pressure of the oil film fluid is 64,867 Pa, which is significantly greater than the cavitation pressure of 3500 Pa, meaning cavitation effects are not considered in this study. All other settings are kept at their default values.

Figure 7.

The average pressure iteration curve for the rotating wall.

2.6. Validation of CFD Model Effectiveness

The accuracy of the model is evaluated by comparing the discrepancy between the theoretical and simulated values [27,29]. The theoretical formula for shear stress in a smooth friction pair is given by

where represents the shear stress of the upper wall, is the velocity gradient, is the dynamic viscosity of the lubricant, is the sliding speed, and is the lubricant film thickness. Given that the lubricant flow in this study follows typical Couette flow, the value of can be obtained from . The theoretical value of the shear stress calculated is 662.68 Pa, while the simulated value is 653.47 Pa, with a relative error of 1.39%, which is less than the allowable error of 5%. Therefore, the finite element model and the computational analysis method used in this study are deemed reasonable.

3. Results and Discussion

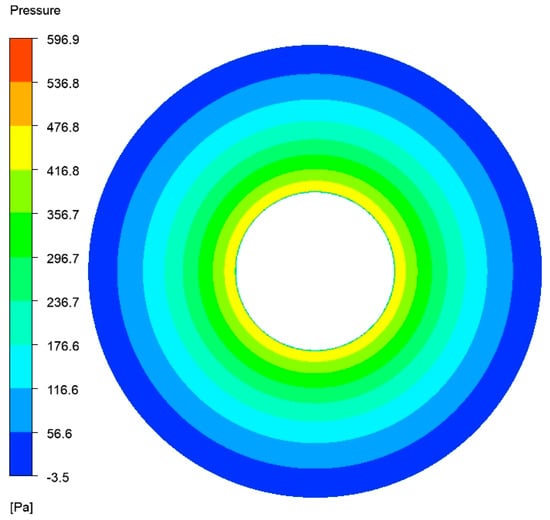

Firstly, the oil film pressure analysis is conducted for the untextured thrust washer, which serves as a baseline for comparing the effects of texture parameters on the oil film pressure. As shown in Figure 8, the radial positive direction is defined as the direction from the inner ring to the outer ring of the thrust washer. The oil film pressure decreases gradually, with the highest pressure reaching 596.9 Pa at the inner ring.

Figure 8.

Pressure distribution on untextured oil film.

To establish a systematic analytical framework, this paper investigates the effects of texture orientation, distribution, area density, and key dimensional parameters on the lubrication performance of the thrust washer to determine their optimal texture configuration. Based on existing research, a ratio of texture diameter to depth of approximately 10 typically yields superior lubrication performance [30]. Considering the dimensional constraints of the thrust washer’s inner and outer diameters, the initial texture dimensions are set as follows: a length of 0.2 mm, a width of 0.15 mm, a depth of 0.02 mm, and a texture angle of 30°. To improve computational efficiency, 1/36 of the thrust washer’s area is taken as the computational model, with 10 textures arranged within this region, resulting in a total of 360 textures for the thrust washer. The textures are evenly spaced in the radial direction, with an overall area density set at 10.88%, a rotational speed of 1000 rpm, and a temperature of 50 °C.

This study employs a one-factor-at-a-time analysis approach, sequentially examining the independent effects of each texture parameter on lubrication performance while fixing the optimal parameters obtained in the previous section. First, the analysis examines the influence of texture orientation (defined as the angle between the symmetry axis of texture and the fluid flow direction) and the radial distribution of the textures on lubrication characteristics. Next, the optimal values for texture depth and area density are discussed. Finally, the study focuses on the geometric features of individual textures, investigating the effects of variations in length ratio (defined as the ratio of texture width to the length of its oblique side) and angle (defined as the angle between the texture’s oblique side and its symmetry axis) on lubrication performance. Additionally, this study investigates the effects of rotational speed and temperature variations on oil film lubrication performance.

3.1. The Effect of V-Shaped Texture Orientation

To clarify the independent influence of texture orientation on oil film lubrication performance, this study first systematically analyzes the effect of the angle between the texture symmetry axis and the fluid flow direction, keeping all other parameters constant. This section discusses the simulation results for five typical values of this angle: 0°, 45°, 90°, 135°, and 180°.

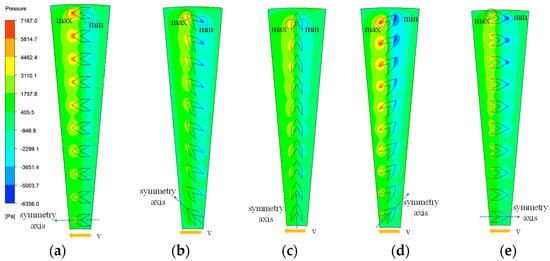

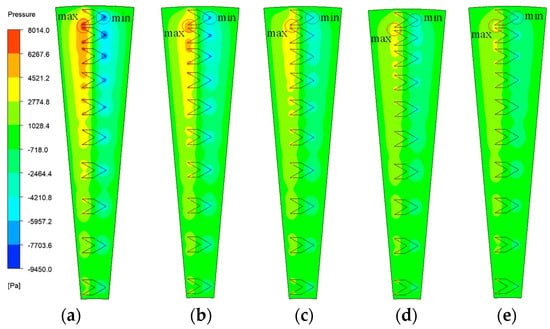

The effect of different texture orientations on oil film pressure distribution is shown in Figure 9. The yellow arrows indicate the fluid velocity direction at the center symmetry axis of the thrust washer in the region, while the blue dashed arrows represent the texture symmetry axis direction. When the texture symmetry axis forms angles of 0°, 45°, 90°, 135°, and 180° with the fluid flow direction, the corresponding maximum oil film pressures are 7167 Pa, 4807 Pa, 4366 Pa, 5756 Pa, and 4763 Pa, respectively. Compared to the maximum pressure of the untextured oil film, these values represent an increase of 6.31 to 11.01 times. As the fluid flows counterclockwise through the thrust washer, the oil film pressure gradually decreases in the untextured region as the fluid approaches the texture, reaching a minimum at the texture’s trailing end to form a divergent wedge. When the fluid flows through the V-shaped texture, the oil film pressure gradually increases, reaching a maximum at the texture’s leading end, forming a convergent wedge. Upon re-entering the untextured region, the pressure gradually decreases again. Radially, as the linear velocity increases, the dynamic pressure effect of the fluid significantly intensifies. This causes the high-pressure and low-pressure zones to expand simultaneously, further amplifying the pressure differential. Both the pressure peak and trough occur at the outermost texture. This phenomenon clearly demonstrates that the increase in radial linear velocity significantly enhances the dynamic pressure effect, improving overall lubrication performance. When the texture orientation is 0° or 135°, the unique tip geometry effectively concentrates the lubricant, resulting in a significant increase in oil film pressure peaks and an expanded high-pressure zone. This enhances the overall hydrodynamic lubrication effect. Furthermore, the apex structure of the V-shaped texture effectively separates the pressurization and depressurization zones, reducing the influence of the negative pressure region on the positive pressure region and improving the oil film load-carrying capacity.

Figure 9.

Effect of texture orientation on the oil film pressure distribution. (a) 0°; (b) 45°; (c) 90°; (d) 135°; (e) 180°.

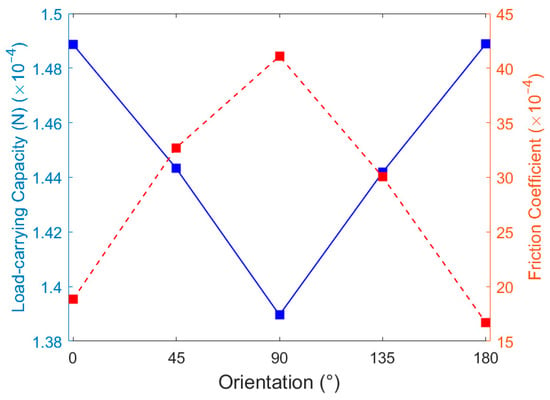

As the angle between the texture symmetry axis and the fluid flow direction increases from 0° to 180°, the oil film load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient are shown in Table 2 and illustrated in Figure 10, varying as follows: the oil film load-carrying capacity first decreases and then increases, while the friction coefficient initially increases and then decreases. At a texture direction of 90°, the oil film load-carrying capacity is at its lowest and the friction coefficient is at its highest, indicating the poorest lubrication performance and ineffective oil storage. When the texture direction is 0° or 180°, lubrication performance is most significant, as lubricant can be stored at the texture tips or tails. When the oil film thickness on the friction pair surface thins, causing the thrust washer to operate under boundary or mixed lubrication conditions, deformation occurs on the mating surfaces under certain loads. In this situation, the lubricant stored within the texture is released onto the friction pair surface under load, providing secondary lubrication. This suggests that the effect of fluid rotation direction on overall lubrication performance is relatively minor. The 0° and 180° texture orientations are geometrically mirror-symmetric, with only a slight difference in friction coefficients. The 0° orientation yields a larger maximum positive pressure, but over a smaller area. In contrast, the 180° orientation features a larger negative pressure zone, effectively isolating the thrust washer from the mating surface, resulting in a lower friction coefficient. For texture directions of 45° and 135°, the load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient are similar. In these cases, the slanted edges of the texture, or the angle between the slanted edge and the width, also contribute to the lubricant accumulation.

Table 2.

Load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient of the oil film in different texture orientations.

Figure 10.

Effect of texture orientation on the oil film load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient.

From the above analysis, it is clear that when the angle between the texture symmetry axis and the fluid flow direction is 180°, the load-carrying capacity is maximized and the friction coefficient is minimized, resulting in optimal lubrication performance. Therefore, in subsequent studies, the texture orientation was fixed at 180°. Additionally, if the texture shape exhibits symmetry, aligning the texture symmetry axis parallel to the fluid flow direction can further enhance lubrication performance.

3.2. The Effect of V-Shaped Texture Distribution

Based on the conclusions from the previous section, this study fixes the optimal texture orientation at 180° and systematically investigates the relationship between the V-shaped texture distribution pattern and lubrication performance. Five representative texture distribution schemes are designed: uniform distribution, radially densified distribution, radially sparse distribution, radial distribution with decreasing then increasing spacing, and radial distribution with increasing then decreasing spacing. The overall textural surface density of the thrust washer remains constant, with the five distribution patterns varying based on radial textural spacing. In the uniform distribution, the radial spacing between adjacent textures is 0.2 mm. In the radially densified distribution, the radial spacing between adjacent textures decreases progressively from 0.36 mm to 0.04 mm. The radial sparse distribution follows the inverse pattern. In the distribution where spacing first decreases then increases, the radial spacing between adjacent textures is 0.52 mm, 0.45 mm, 0.39 mm, 0.31 mm, 0.26 mm, 0.31 mm, 0.39 mm, 0.45 mm, and 0.52 mm. In the distribution where spacing first increases then decreases, the radial spacing between adjacent textures is 0.32 mm, 0.37 mm, 0.41 mm, 0.46 mm, 0.50 mm, 0.46 mm, 0.41 mm, 0.37 mm, and 0.32 mm.

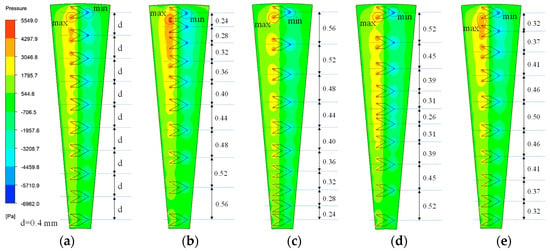

The oil film pressure distribution for different texture distributions is shown in Figure 11. The maximum oil film pressures for the five texture distribution patterns are 4763 Pa, 5549 Pa, 4828 Pa, 4681 Pa, and 4922 Pa, respectively. The peak values are 6.84 to 8.29 times higher than those of the untextured oil film. The high-pressure and low-pressure zones are stably distributed near the tip and tail ends of the texture. Notably, since the outermost texture is close to the pressure outlet, its peak pressure region occurs at the inner tip of the texture. The radial densification distribution pattern yields the largest increase in maximum oil film pressure. This is due to the reduced spacing between the two outermost textures, allowing their tips to collectively form a larger lubricant convergence unit. This phenomenon confirms that increasing the texture area density positively impacts oil film pressure.

Figure 11.

Effect of texture distribution on the oil film pressure distribution. (a) Constant spacing; (b) decreasing spacing; (c) increasing spacing; (d) spacing decreasing then increasing; (e) spacing increasing then decreasing.

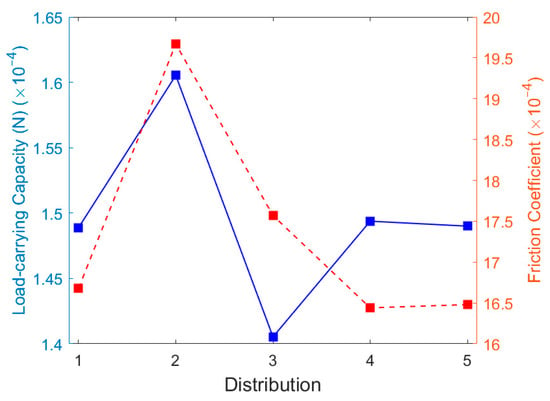

Figure 12 illustrates the impact of different texture distribution patterns on the oil film load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient. The horizontal axis labels 1 through 5 correspond to the five texture distribution patterns in Figure 11a–e, with specific values provided in Table 3. When the texture follows a radially densified distribution, the oil film load-carrying capacity is the lowest. In contrast, the load-carrying capacity is highest under the radially sparse distribution, although the friction coefficient also reaches its maximum at this point. When the texture is evenly distributed or when the radial spacing varies gradually, the values for both oil film load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient are relatively similar. Based on the equivalent stress analysis under the actual operating conditions and assembly relationships of the thrust washer, it is evident that stress concentration is more pronounced in the outer ring region. Assembly errors cause the thrust washer to tilt relative to the planetary gear, needle rollers, and shaft, leading to eccentric wear between the thrust washer and the end face of the planetary gear. Given the more severe wear near the outer diameter of the thrust washer observed during actual operation, adopting a radially decreasing spacing texture distribution can help improve the oil film’s load-carrying capacity. This distribution allows the textures to store lubricant in areas with more severe wear, which can be released during lubrication shortages to provide secondary lubrication, thereby improving wear conditions. Therefore, in subsequent studies, the radially densified texture distribution will be adopted.

Figure 12.

Effect of texture distribution on the oil film load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient.

Table 3.

Load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient of the oil film in different texture distributions.

3.3. The Effect of V-Shaped Texture Depth

In this section, the optimal radially densified texture distribution is fixed, and the effect of V-shaped texture depth on the oil film pressure distribution, load-carrying capacity, and friction coefficient is further investigated.

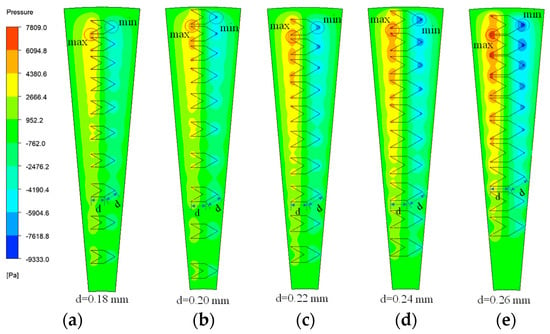

As the texture depth increases from 0.01 mm to 0.03 mm, the maximum oil film pressure values are 8014 Pa, 6500 Pa, 5549 Pa, 4431 Pa, and 3873 Pa, showing a clear downward trend, as shown in Figure 13. Compared to the untextured surface, the maximum oil film pressure at these texture depths increases by factors ranging from 5.49 to 12.42.

Figure 13.

Effect of texture depth on the oil film pressure distribution. (a) 0.01 mm; (b) 0.015 mm; (c) 0.02 mm; (d) 0.025 mm; and (e) 0.03 mm.

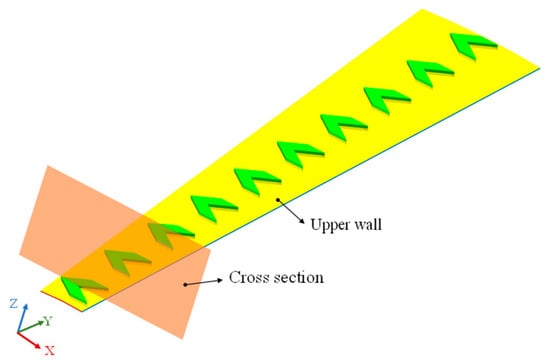

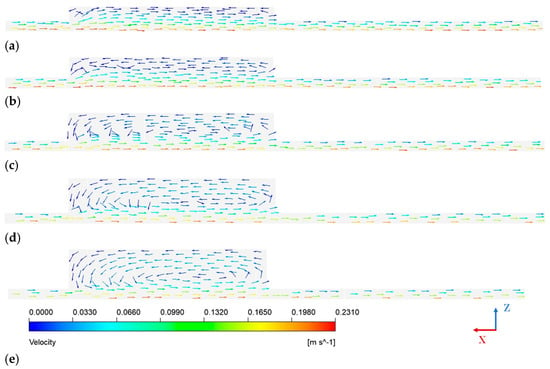

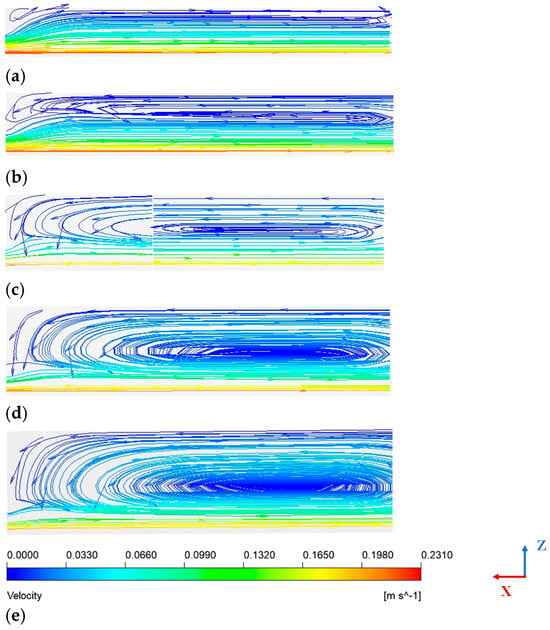

A cross-section parallel to the ZX plane at y = 2.25 mm, as shown in Figure 14, is used to analyze the fluid velocity vector distribution. As seen in Figure 15, the maximum fluid velocity occurs at the lower wall of the fluid domain, which corresponds to the contact interface between the thrust washer and its paired friction pair. The velocity direction aligns with the motion direction of the mating friction pair, indicating that the oil in this region flows synchronously with the moving surface under viscous forces. Along the positive z-axis direction, the fluid velocity decreases overall, with the minimum velocity occurring at the bottom surface of the texture. Due to the influence of the micro-vortices, regions within the texture exhibit velocities approaching zero. Under identical cross-sectional conditions, the maximum fluid velocities in textures of different depths remain nearly the same. From the fluid streamline diagram in Figure 16, the development of vortices with increasing texture depth can be further observed. At a texture depth of 0.01 mm, vortices within the texture have not fully formed and only small vortices appear near the wall surface. However, at a texture depth of 0.015 mm, vortices forming within the texture are clearly observable. As texture depth increases, the low-velocity vortex region expands and intensifies. Excessively strong vortices hinder lubricant inflow into the texture, reducing the flow rate at the outlet of the textured region and diminishing fluid dynamic pressure. During vortex development, part of the fluid’s kinetic energy is converted into vortex energy, weakening the dynamic pressure effect. As a result, the vortex effect dominates, adversely affecting the load-carrying capacity of the oil film and reducing fluid pressure.

Figure 14.

Cross-section of the fluid domain.

Figure 15.

Velocity vector diagram of fluid flow at the cross-section. (a) 0.01 mm; (b) 0.015 mm; (c) 0.02 mm; (d) 0.025 mm; (e) 0.03 mm.

Figure 16.

Streamline diagram of fluid flow at the cross-section. (a) 0.01 mm; (b) 0.015 mm; (c) 0.02 mm; (d) 0.025 mm; (e) 0.03 mm.

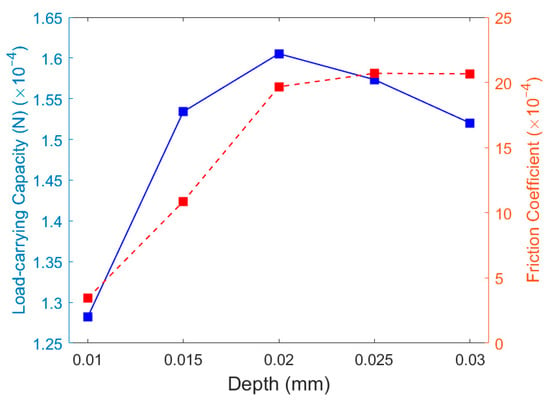

The relationship between texture depth, oil film load-carrying capacity, and friction coefficient is shown in Figure 17, with specific values listed in Table 4. The results indicate that as texture depth increases, the oil film load-carrying capacity first rises and then decreases, while the friction coefficient follows a similar pattern, increasing initially and then declining. When the texture depth reaches 0.02 mm, the oil film load-carrying capacity peaks, indicating that this depth achieves an optimal balance between secondary lubrication from lubricant release and energy dissipation caused by micro-vortex formation. As the texture depth increases from 0.01 mm to 0.02 mm, the enhanced oil film thickness increases the lubricant’s storage capacity, improving the oil film’s load-carrying capacity. However, when the texture depth exceeds 0.02 mm, the lubricant stored at the bottom of the texture becomes difficult to replenish under pressure and the presence of vortices within the texture reduces hydrodynamic lubrication performance, leading to a decrease in the load-carrying capacity. As the texture depth increases from 0.01 mm to 0.025 mm, the vortex region expands significantly and the vortex center shifts toward the lower wall of the fluid domain, where its velocity approaches zero, while the fluid velocity on the lower wall remains nearly constant due to viscous forces. This increases the fluid velocity gradient. As shown in Equation (9), the friction coefficient is proportional to the fluid velocity gradient, resulting in a continuous rise in the oil film friction coefficient. At a texture depth of 0.03 mm, the vortex region shows minimal change compared to 0.025 mm, and the increased texture depth slightly enhances the oil film thickness. Consequently, the combined effects result in a slight decrease in the oil film friction coefficient. Since the friction coefficient remains relatively low for all depths, satisfying actual operating conditions, this study uses oil film load-carrying capacity as the primary criterion for optimizing texture parameters. Therefore, in subsequent studies, the texture depth will be fixed at 0.02 mm.

Figure 17.

Effect of texture depth on the oil film load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient.

Table 4.

Load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient of the oil film in different texture depths.

3.4. The Effect of V-Shaped Texture Area Density

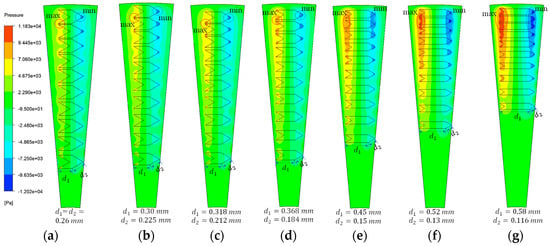

To eliminate the influence of the length ratio between the texture width and slant edge on the area density, and under the constraint of texture shape and size, this study fixes the texture length ratio at 1. The texture lengths are set to 0.18 mm, 0.2 mm, 0.22 mm, 0.24 mm, and 0.26 mm, with corresponding area densities of 11.75%, 14.51%, 17.56%, 20.89%, and 24.52%. To avoid texture overlap or manufacturing difficulties, the upper limit of the actual area density is 24.52%. Additionally, based on previous optimization results, the texture depth is uniformly set to 0.02 mm, with all other parameters remaining unchanged.

The results shown in Figure 18 indicate that, as the texture area density increases from 11.75% to 24.52%, the maximum oil film pressure rises from 5527 Pa to 7809 Pa, with specific values of 5527 Pa, 6154 Pa, 6571 Pa, 6956 Pa, and 7809 Pa, respectively. The peak values are 8.26 to 12.08 times higher than those of the untextured oil film, indicating that higher surface density enhances the texture’s convergence effect on the lubricant, thereby improving the oil film’s load-carrying capacity. When the area density reaches 24.52%, the reduced radial spacing of the texture near the outer diameter of the thrust washer forms a nearly continuous hydrodynamic region. This enhances the convergence effect at the texture tips, expanding the high-pressure region of the oil film and further increasing the pressure peak.

Figure 18.

Effect of texture area density on the oil film pressure distribution. (a) 11.75%; (b) 14.51%; (c) 17.56%; (d) 20.89%; (e) 24.52%.

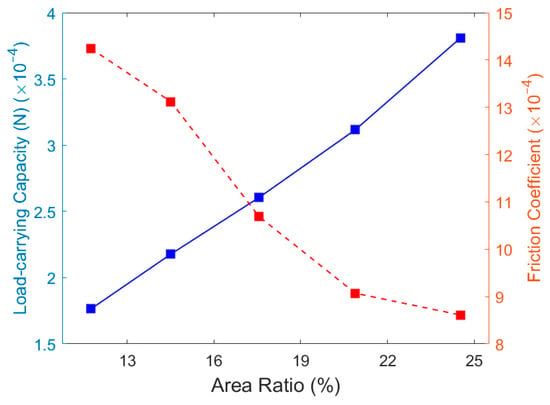

The relationship between texture area density and the oil film’s load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient is shown in Figure 19, with specific values listed in Table 5. As the texture area density increases, the oil film load-carrying capacity improves significantly, while the friction coefficient decreases markedly. This change is primarily due to the increased lubricant storage capacity resulting from the higher area density, which enhances the overall lubrication performance of the oil film. A comprehensive analysis shows that when the area density reaches 24.52%, the texture exhibits optimal lubrication characteristics. Therefore, this area density will be fixed in subsequent studies.

Figure 19.

Effect of texture area density on the oil film load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient.

Table 5.

Load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient of the oil film in different texture area densities.

3.5. The Effect of V-Shaped Texture Length Ratio

To systematically investigate the effect of texture size parameters on lubrication performance, this section focuses on studying the impact of texture length ratio, defined as the ratio of the texture width to the slant edge length, on oil film lubrication performance. Based on the optimal area density of 24.52%, the influence of varying the V-shaped texture length ratio on oil film pressure distribution, load-carrying capacity, and friction coefficient is analyzed. Due to the structural limitations of the thrust washer, textures with length ratios less than 1 or greater than 5 are difficult to achieve. Therefore, the seven length ratios used for system simulation and comparative analysis are 1, 1.33, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, and 5.

The effect of texture length ratio on oil film pressure distribution is shown in Figure 20, with maximum pressures of 7809 Pa, 8174 Pa, 8465 Pa, 8945 Pa,9940 Pa, 10,900 Pa, and 11,830 Pa, respectively. The results show that as the texture length ratio increases, both the high-pressure and low-pressure regions of the oil film expand, with corresponding increases in pressure peaks. This phenomenon indicates that, under constant area density, increasing the texture length ratio significantly alters the oil film pressure distribution, thereby enhancing its load-carrying capacity.

Figure 20.

Effect of texture length ratio on the oil film pressure distribution. (a) 1; (b) 1.33; (c) 1.5; (d) 2; (e) 4; (f) 4; (g) 5.

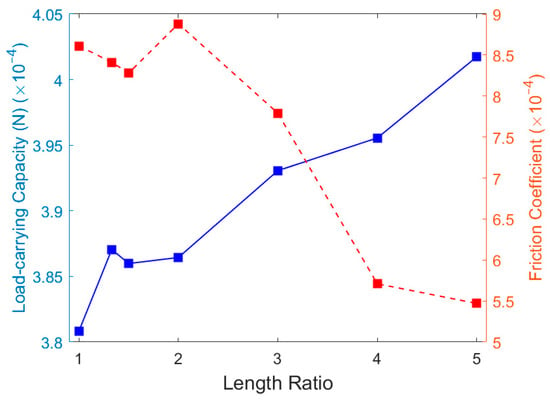

The changes in oil film load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient as the texture length ratio increases from 1 to 5 are shown in Table 6. As depicted in Figure 21, the oil film load-carrying capacity initially increases, then slightly decreases, and subsequently continues to rise. In contrast, the friction coefficient follows an opposite pattern. With the exception of the conditions where the length ratio is 1.5 and 2, the lubrication performance generally improves as the length ratio increases. To achieve a radially denser texture distribution while accounting for variations in texture dimensions, the radial clearance between the outermost texture and the outer diameter increases for length ratios of 1.5 and 2 compared to a ratio of 1. This reduction in the linear velocity of the outermost texture leads to a slight decrease in oil film load-carrying capacity. As the length ratio continues to increase, constrained by the thrust washer’s dimensions, the entire texture shifts radially outward. Consequently, the texture distribution around the outer circumference of the thrust washer becomes denser, resulting in a sustained improvement in oil film load-carrying capacity. At a texture length ratio of 2, the areas of positive and negative pressure zones are relatively close, resulting in the highest friction coefficient. As the length ratio increases further, the positive pressure zone area expands significantly, causing the friction coefficient to decrease. When the area density remains constant and a radially dense distribution pattern is adopted to achieve a texture length ratio of 5, the resulting elongated texture significantly increases the texture density in the outer ring region of the thrust washer within the limited width. This high-density distribution pattern helps form more effective lubricant storage units in areas of severe wear, enabling effective secondary lubrication and improving wear conditions. Therefore, in subsequent research, a texture length ratio of 5 will be adopted as the fixed parameter to further explore the impact of texture angle on lubrication performance.

Table 6.

Load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient of the oil film in different texture length ratios.

Figure 21.

Effect of texture length ratio on the oil film load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient.

3.6. The Effect of V-Shaped Texture Angle

Based on the optimal parameter combination obtained, this section explores the influence of the texture angle, defined as the angle between the texture’s inclined edge and the symmetry axis, on oil film lubrication performance.

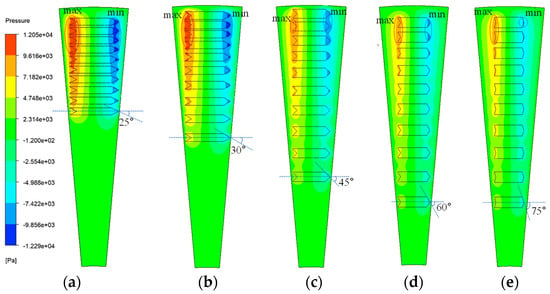

Figure 22 shows the pressure distribution of the oil film at different texture angles. As the texture angle increases from 25° to 75°, the maximum oil film pressure decreases monotonically, with corresponding values of 12,050 Pa, 11,830 Pa, 10,200 Pa, 9263 Pa, and 8827 Pa. As the texture angle increases, the texture geometry evolves from elongated to shorter and wider. This change causes the high-pressure and low-pressure regions to contract, leading to a decrease in the pressure peak. Under fixed length ratios and radial densification distribution patterns, smaller texture angles result in more elongated shapes. Constrained by the dimensions of the thrust washer, the overall radial displacement increases the texture density in the outer ring, thereby elevating the maximum oil film pressure.

Figure 22.

Effect of texture angle on the oil film pressure distribution. (a) 25°; (b) 30°; (c) 45°; (d) 60°; (e) 75°.

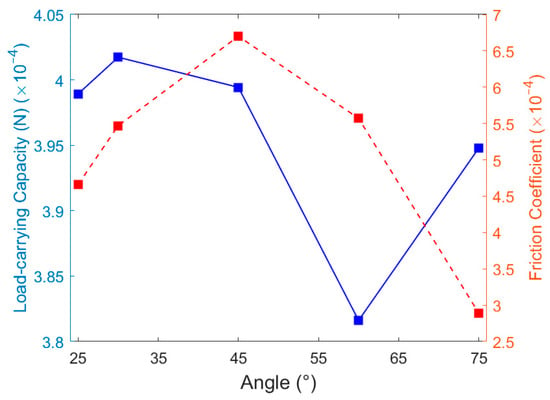

As the texture angle increases from 25° to 75°, the specific values of the oil film load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient are shown in Table 7. Figure 23 illustrates that the oil film load-carrying capacity exhibits a non-monotonic variation: it initially increases, then decreases, and finally increases again. In contrast, the friction coefficient first increases and then decreases. When the texture angle is 25°, the smaller circumferential spacing between the textures causes the fluid to flow rapidly from the positive pressure region to the adjacent texture’s negative pressure region. According to Bernoulli’s principle, fluid pressure is inversely proportional to flow velocity [24]. Therefore, increased fluid velocity reduces pressure, leading to lower oil film load-carrying capacity at this angle compared to the 30° condition. However, the maximum oil film pressure remains optimal because the overall texture shifts radially while decreasing spacing, forming a larger lubricant convergence unit. This demonstrates the advantages of the V-shaped texture’s orientation and configuration aligned with the fluid flow direction. At a texture angle of 60°, the overall texture shifts radially in the opposite direction, resulting in fewer texture elements at the thrust washer’s outer ring and a significant decrease in fluid load-carrying capacity. Conversely, at a texture angle of 75°, compared to 60°, the area of positive pressure zones changes minimally, while the area of negative pressure zones decreases. Consequently, the oil film load-carrying capacity increases and the friction coefficient decreases significantly. Using the oil film load-carrying capacity as the selection criterion for texture parameters, the optimal texture angle for the V-shaped texture is determined to be 30°.

Table 7.

Load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient of the oil film in different texture angles.

Figure 23.

Effect of texture angle on the oil film load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient.

3.7. The Effect of Rotational Speed and Temperature

Considering the actual operating speed and temperature variations in planetary gear reducers, this study investigates the changes in oil film lubrication performance when the thrust washer speed increases from 1000 r/min to 3000 r/min and the temperature rises from 50 °C to 100 °C, while maintaining the optimal texture parameters discussed earlier. As temperature increases, lubricant viscosity decreases, as calculated using the following formula:

where is the lubricant viscosity at the reference temperature, is the actual temperature, is the reference temperature (50 °C in this study), and is the viscosity–temperature coefficient, which was experimentally fitted to 0.03279.

Figure 24 illustrates the oil film pressure distribution at different rotational speeds. As the speed increases from 1000 rpm to 3000 rpm, the maximum fluid pressures increase to 11,830 Pa, 17,728 Pa, 23,631 Pa, 29,512 Pa, and 35,448 Pa, respectively. The total areas of both positive and negative pressure zones, along with their corresponding peak values, show a significant increase with rising rotational speed.

Figure 24.

Effect of rotational speed on the oil film pressure distribution. (a) 1000 rpm; (b) 1500 rpm; (c) 2000 rpm; (d) 2500 rpm; (e) 3000 rpm.

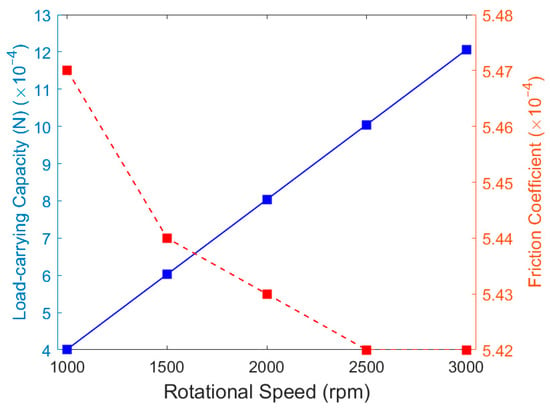

As rotational speed increases, the specific values of oil film load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient are listed in Table 8. Figure 25 shows that the oil film load-carrying capacity increases approximately linearly with rising rotational speed, while the friction coefficient gradually decreases. The rate of decrease slows down, and the overall change remains relatively small. Increasing rotational speed enhances the fluid velocity on the lower wall surface, accelerating the rotational speed of vortices within the texture. This helps replenish lubricating oil within the texture to the thrust washer and gear contact surfaces, providing secondary lubrication and improving lubrication performance.

Table 8.

Load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient of the oil film in different rotational speeds.

Figure 25.

Effect of rotational speed on the oil film load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient.

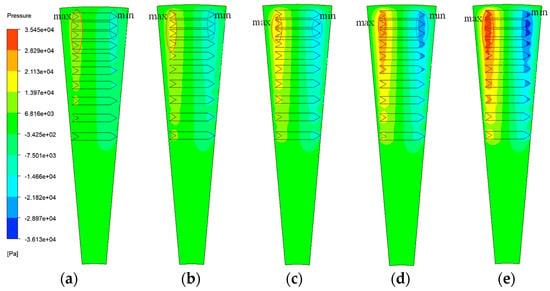

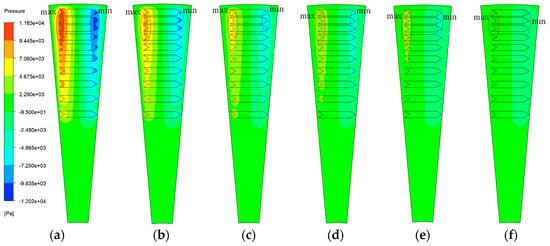

At temperatures of 50 °C, 60 °C, 70 °C, 80 °C, 90 °C, and 100 °C, the corresponding lubricant viscosities are 0.0125 Pa·s, 0.0090 Pa·s, 0.0065 Pa·s, 0.0047 Pa·s, 0.0034 Pa·s, and 0.0024 Pa·s, respectively. Figure 26 illustrates the variation in oil film pressure distribution with increasing temperature, with maximum fluid pressures of 11,830 Pa, 8505 Pa, 6144 Pa, 4446 Pa, 3215 Pa, and 2268 Pa, respectively. Oil film pressure decreases significantly as temperature rises. At 100 °C, no distinct pressure increase or decrease zones are observed at the two ends of the texture. At this point, the lubricant viscosity is too low to generate an effective hydrodynamic lubrication effect.

Figure 26.

Effect of temperature on the oil film pressure distribution. (a) 50 °C; (b) 60 °C; (c) 70 °C; (d) 80 °C; (e) 90 °C; (f) 100 °C.

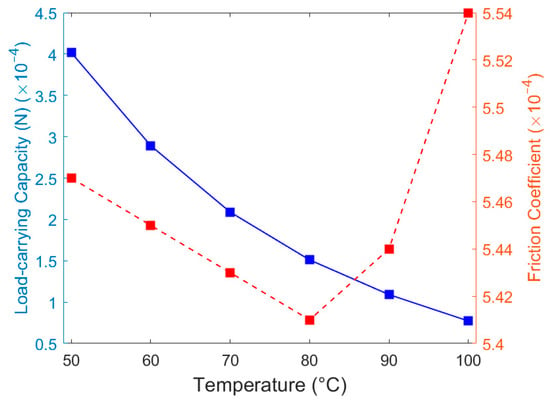

The oil film load-bearing capacity and friction coefficient at different temperatures are listed in Table 9. Figure 27 illustrates their variation trends: the oil film load-carrying capacity gradually decreases with increasing temperature, with the rate of change becoming more gradual. The friction coefficient initially decreases and then increases, with a relatively small overall change. Since the area of the positive pressure zone decreases more significantly than the negative pressure zone, their combined effect results in a reduction in the oil film load-carrying capacity. The shear stress of the fluid is linearly related to the lubricant’s viscosity. As a result, the friction coefficient initially decreases in a linear fashion. However, as the temperature continues to rise, the friction coefficient starts to increase. This occurs because, at excessively low viscosities, the fluidity of the vortex flow intensifies, expanding its range. Meanwhile, the centers of the micro-vortices shift closer to the lower wall of the fluid domain, increasing the velocity gradient.

Table 9.

Load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient of the oil film in different temperature.

Figure 27.

Effect of temperature on the oil film load-carrying capacity and friction coefficient.

Based on the above analysis of rotational speed and temperature, it is clear that operating conditions significantly influence the lubricating performance of the oil film. This further demonstrates the role of speed in enhancing the load-carrying capacity of the oil film. At the same time, it highlights that rising temperatures reduce the textural effect’s ability to promote fluid dynamic pressure. Therefore, during reducer operation, attention should be given to heat dissipation to prevent premature failure of the lubricating oil film due to excessive oil temperature, which could exacerbate friction and wear.

4. Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the influence of V-shaped surface texture parameters on the oil film lubrication performance of the thrust washer in the planetary gear reducer, addressing the issue of insufficient lubrication during operation through numerical simulation. The research focused on six key parameters: texture direction, distribution, depth, area density, length ratio, and angle. This study employed a one-factor-at-a-time analysis approach, sequentially exploring the independent effects of each subsequent parameter while keeping the optimal solution of the previous parameter fixed. The results indicate that textures with a sharp-end feature in the direction of fluid flow effectively concentrate the lubricant, thereby significantly enhancing the oil film pressure. The radially densified distribution and textures with a length ratio of 5 contribute to improving the texture density in the outer ring of the thrust washer, addressing severe wear issues caused by stress concentration. The texture depth exhibits an optimal value: when it exceeds 0.02 mm, the formation of micro-vortices leads to the dissipation of fluid kinetic energy, which negatively affects the oil film load-carrying capacity. Additionally, increasing the texture area density appropriately enhances lubricant storage capacity, providing conditions for secondary lubrication. However, the circumferential spacing between textures should not be excessively small, as this would cause fluid to rapidly flow from positive pressure zones to negative pressure zones, leading to reduced load-bearing capacity. Based on the aforementioned principles, this study ultimately determined the optimal parameter combination for V-shaped texture as follows: a length ratio of 5, an angle of 30°, an area density of 24.52%, and a depth of 0.02 mm. The texture symmetry axis direction is opposite to the fluid flow velocity direction, employing a radially dense distribution. This configuration enables synergistic enhancement of the overall lubrication performance in the optimized thrust washer, with the maximum oil film pressure increasing by 18.82 times compared to the untextured surface. Additionally, the lubricating performance of the oil film improves with increasing rotational speed and lubricant viscosity. Comprehensive analysis indicates that the thrust washer featuring V-shaped surface texture not only establishes effective hydrodynamic lubrication within localized textured regions but also achieves a significant increase in load-carrying capacity across the entire contact surface. This research demonstrates how improving lubricant efficiency reduces surface contact within friction pairs, thereby enhancing wear resistance. Consequently, it provides a reliable theoretical basis and design guidance for addressing friction and wear issues in such components, offering practical engineering significance. This study exclusively employs numerical simulations to investigate the influence of texture parameters on lubrication performance under fluid lubrication conditions. In the future, experimental measurements of the friction coefficient of textured thrust washers will be conducted to further validate the rationale behind texture parameter optimization. Additionally, the optimal texture parameters obtained under fluid lubrication conditions may change under mixed lubrication. Future research will explore the effect of texture parameters on lubrication performance in mixed lubrication, using either experimental or theoretical calculations, thereby broadening the scope of research on optimizing the lubrication performance of thrust washers in planetary gear systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Z. and H.J.; methodology, S.Z.; software, S.Z.; validation, S.Z., H.J. and J.G.; formal analysis, H.J.; investigation, J.G.; resources, S.Z.; data curation, S.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Z.; writing—review and editing, J.Z. and H.J.; visualization, J.G.; supervision, J.Z.; project administration, J.Z.; funding acquisition, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

| N-S | Navier–Stokes |

References

- Pedrero, J.I.; Sánchez-Espiga, J.; Sánchez, M.B.; Pleguezuelos, M.; Fernández-del-Rincón, A.; Viadero, F. Simulation and validation of the transmission error, meshing stiffness, and load sharing of planetary spur gear transmissions. Mech. Mach. Theory 2024, 203, 105800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Zuo, M.J.; Guo, Y. Evaluating the Time-Varying Mesh Stiffness of a Planetary Gear Set Using the Potential Energy Method. In Proceedings of the 7th World Congress on Engineering Asset Management (WCEAM 2012), Daejeon City, Republic of Korea, 8–9 October 2012; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 365–374. [Google Scholar]

- Etsion, I. Modeling of surface texturing in hydrodynamic lubrication. Friction 2013, 1, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibatan, T.; Uddin, M.S.; Chowdhury, M.A.K. Recent development on surface texturing in enhancing tribological performance of bearing sliders. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 272, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ye, R.; Xiang, J. The performance of textured surface in friction reducing: A review. Tribol. Int. 2023, 177, 108010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Kato, K.; Adachi, K.; Aizawa, K. Loads carrying capacity map for the surface texture design of SiC thrust bearing sliding in water. Tribol. Int. 2003, 36, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, D.Y.; Hua, M.; Dong, G.N.; Chin, K.S. A Study on the Tribological Behavior of Surface Texturing on Babbitt Alloy under Mixed or Starved Lubrication. Tribol. Lett. 2014, 56, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lin, N.; Yuan, S.; Liu, Z.; Yu, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Li, D.; Fan, J.; Wu, Y. Numerical simulation on hydrodynamic lubrication performance of bionic multi-scale composite textures inspired by surface patterns of subcrenata and clam shells. Tribol. Int. 2023, 181, 108335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Q.; Bai, J.; Meng, X.; Ji, C.; Liang, Y. Drag reduction characteristics and flow field analysis of textured surface. Friction 2016, 4, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; He, Y.; Luo, J. Optimization of surface texture distribution on the thrust bearing using the mass-conserving cavitation boundary condition: Theory and experiments. Tribol. Int. 2024, 194, 109551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongtao, W.; Yan, L.I.; Hua, Z. Effect of Geometry Parameters and Patterns on Tribological Properties of Textured Surface with Elliptical Dimples. Tribology 2016, 36, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateswara Babu, P.; Syed, I.; BenBeera, S. Experimental investigation on effects of positive texturing on friction and wear reduction of piston ring/cylinder liner system. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 24, 1112–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yan, Z.; Fang, X.; Shen, Z.; Pan, X. Observation and experimental investigation on cavitation effect of friction pair surface texture. Lubr. Sci. 2020, 32, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, P.V.; Ismail, S.; Ben, B.S. Experimental and numerical studies of positive texture effect on friction reduction of sliding contact under mixed lubrication. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2020, 235, 360–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segu, D.Z.; Lu, C.; Hwang, P.; Kang, S.-W. Optimization of Tribological Characteristics of a Combined Pattern Textured Surface Using Taguchi Design. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2021, 30, 3786–3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, Z.; Zhao, F.; Gao, F.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Dong, G. Study on tribological behavior of grooved-texture surfaces under sand–oil boundary lubrication conditions. Tribol. Trans. 2021, 64, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hingawe, N.D.; Bhore, S.P. Tribological performance of a surface textured meso scale air bearing. Ind. Lubr. Tribol. 2020, 72, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Xu, J.; Liu, P.; Shi, Z.; Yang, O.; Hu, Y. Geometric influence on friction and wear performance of cast iron with a micro-dimpled surface. Results Eng. 2021, 9, 100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Huang, W.; Wang, X. Orientation effects of micro-grooves on sliding surfaces. Tribol. Int. 2011, 44, 1047–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Khonsari, M.M. Numerical optimization of texture shape for parallel surfaces under unidirectional and bidirectional sliding. Tribol. Int. 2015, 82, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; He, Y.; Zhao, J.; Mao, J.; Hu, Y.; Luo, J. Optimization of groove texture profile to improve hydrodynamic lubrication performance: Theory and experiments. Friction 2020, 8, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; He, Y.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Luo, J. Numerical optimization of the groove texture bottom profile for thrust bearings. Tribol. Int. 2017, 109, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, H.L.; Hutchings, I.M. Hydrodynamic lubrication of textured steel surfaces under reciprocating sliding conditions. Tribol. Int. 2007, 40, 1227–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Wang, F.; Chen, Z.; Ruan, X.; Zeng, H.; Wang, J.; An, Y.; Fan, X. Numerical simulation of lubrication performance on chevron textured surface under hydrodynamic lubrication. Tribol. Int. 2021, 154, 106704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhirong, T.; Xiangkai, M.; Yi, M.; Xudong, P. Shape optimization of hydrodynamic textured surfaces for enhancing load-carrying capacity based on level set method. Tribol. Int. 2021, 162, 107136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, U.; Jacobson, S. Influence of surface texture on boundary lubricated sliding contacts. Tribol. Int. 2003, 36, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Yang, J.; Gu, Q. Numerical study on the hydrodynamic lubrication performance improvement of bio-inspired peregrine falcon wing-shaped microtexture. Tribol. Int. 2024, 191, 109049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Chen, W.; Wang, H.; Qiu, Z.; Wei, B.; Cheng, J.; Yuan, H.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, H. Simulation and experimental research on the cavitation phenomenon of wedge-shaped triangular texture on the surface of 3D-printed titanium alloy materials. Tribol. Int. 2024, 198, 109869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Ni, H.; Chen, H.; Wang, P. Numerical simulation and experimental investigation on tribological performance of micro-dimples textured surface under hydrodynamic lubrication. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2019, 163, 105095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.P.; Polycarpou, A.A. Tribological studies of unpolished laser surface textures under starved lubrication conditions for use in air-conditioning and refrigeration compressors. Tribol. Int. 2011, 44, 1890–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.