Parameterized Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test for Normality

Abstract

1. Introduction

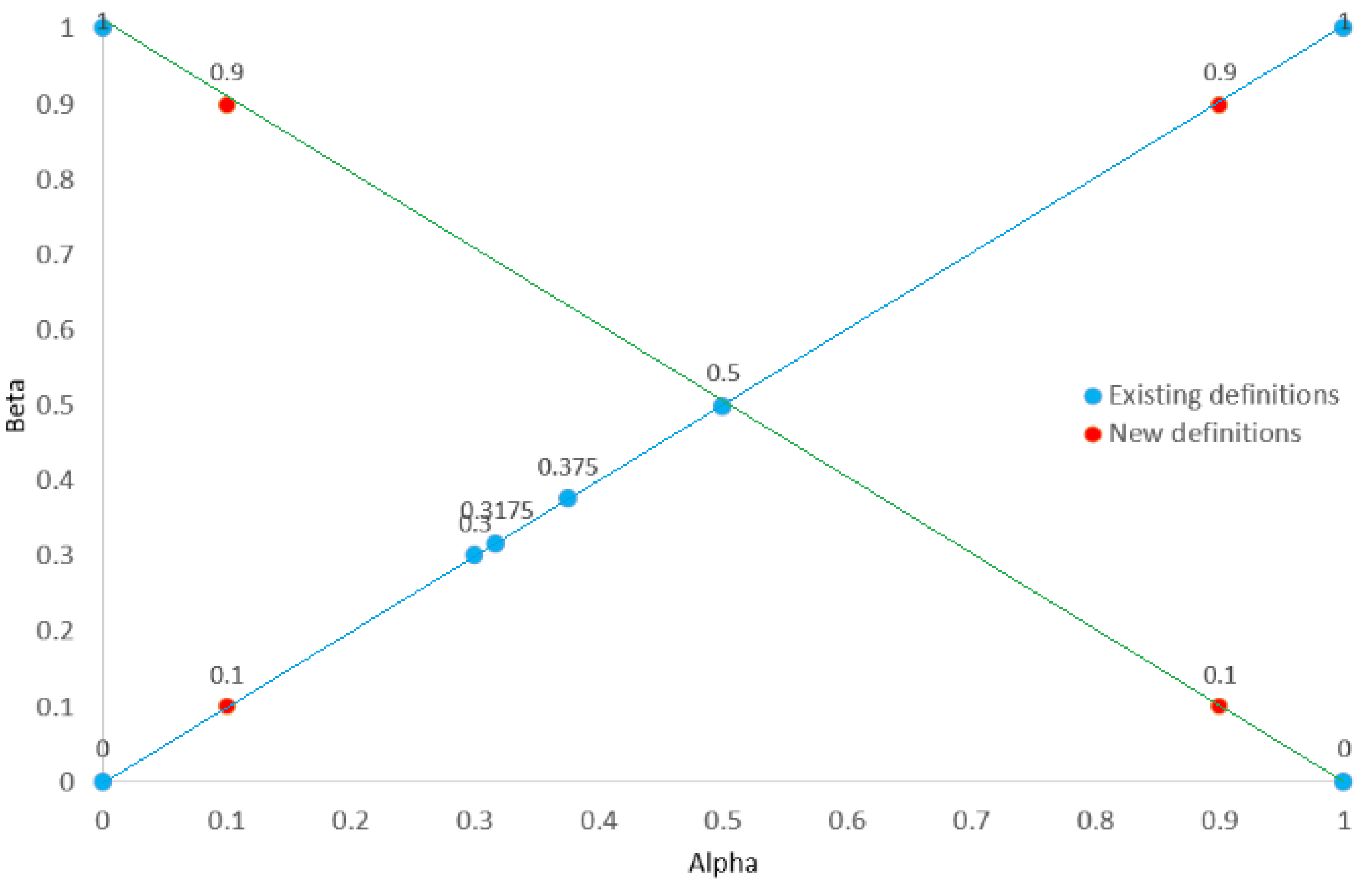

- —occurs in the KS statistic,

- —occurs in the KS statistic,

- —appears in the CM statistic, expressed as the sum,

- —the i-th order statistic’s mean for the beta distribution

- —the beta distribution’s i-th order statistic median,

- – the mean of the i-th order statistic of the Gaussian distribution,

- —founded by Filliben [17],

- – founded by Harter [9].

2. Parameterized Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test for Normality

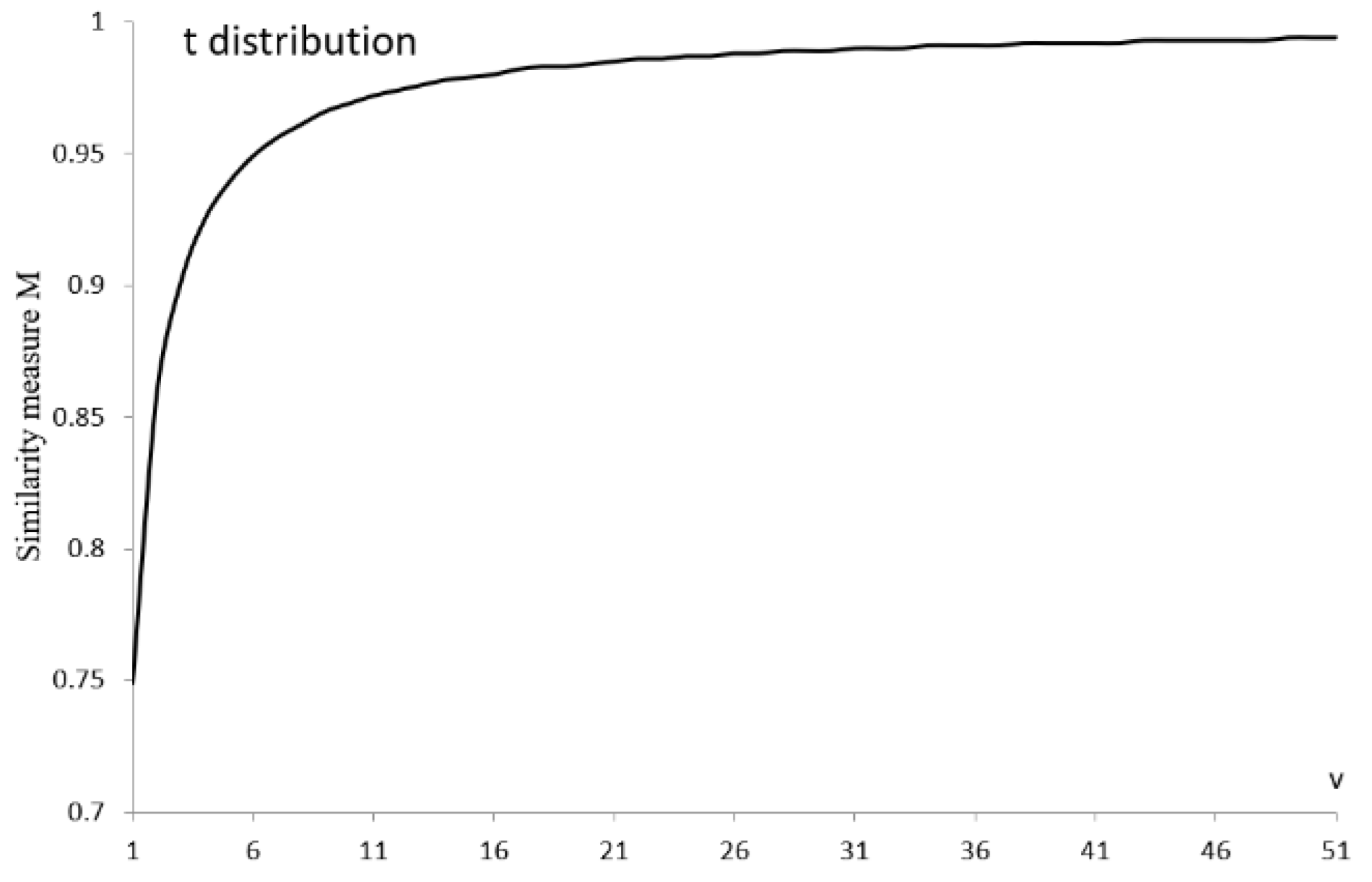

3. Similarity Measure

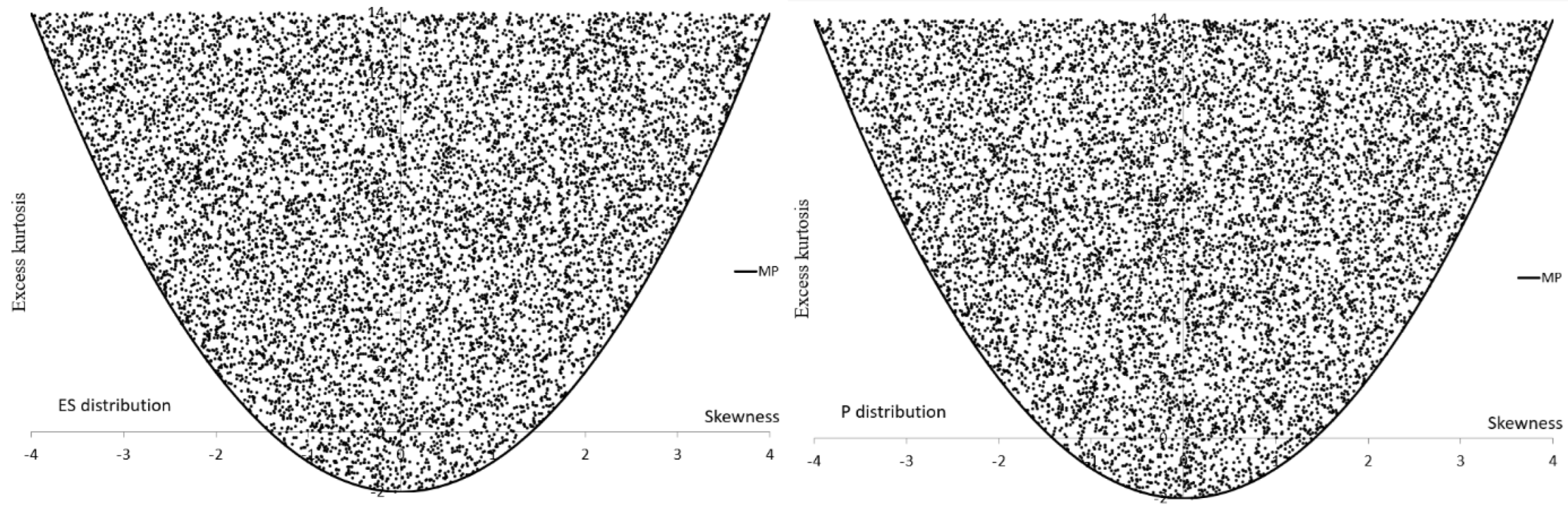

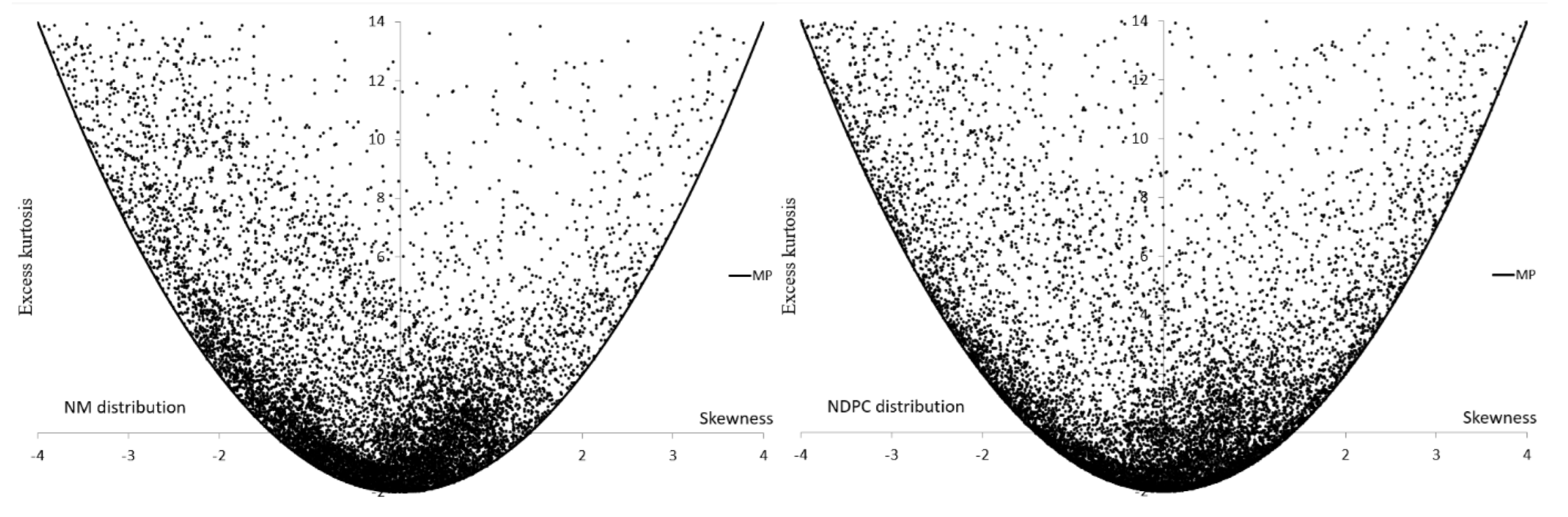

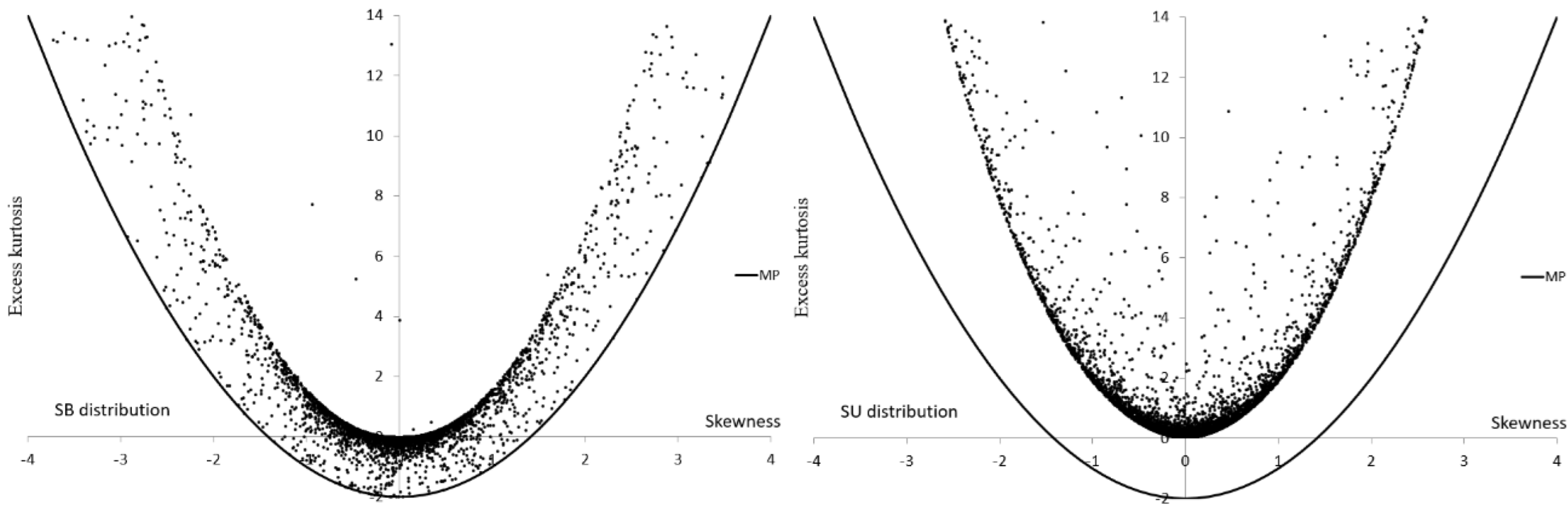

4. Alternative Distributions

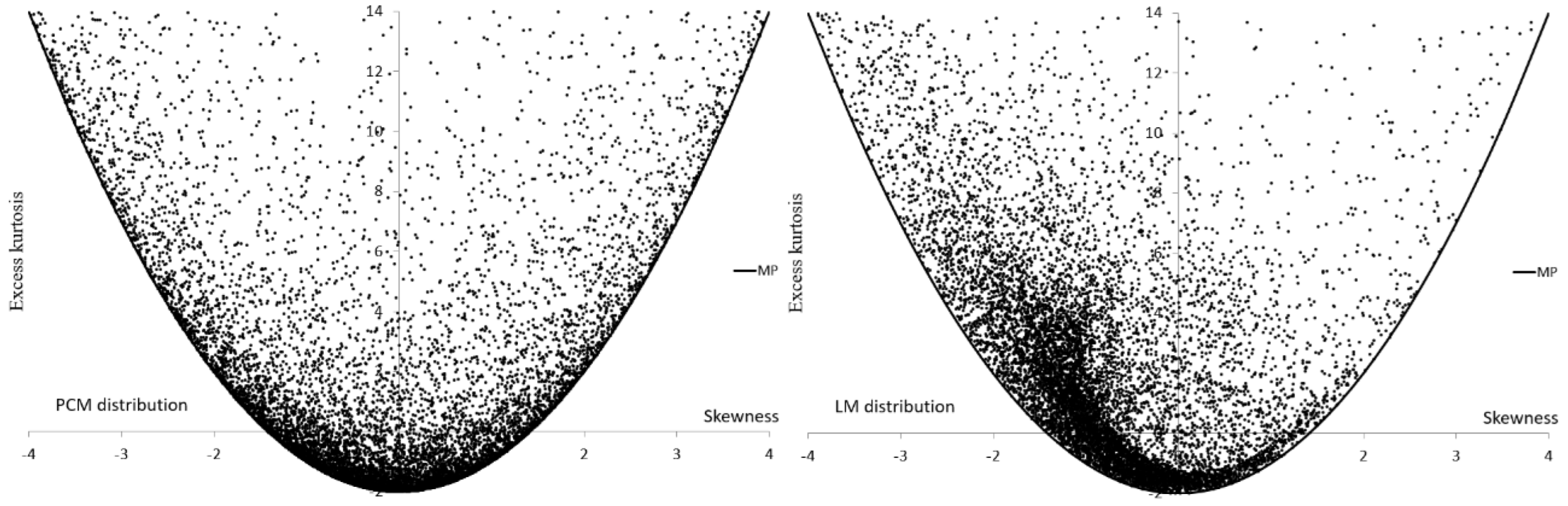

5. Power Study

6. Real Data Examples

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A | Alternative distribution |

| AD | Anderson–Darling test |

| ALT | Alternative distribution |

| CDF | Cumulative distribution function |

| CM | Cramér–von Mises test |

| CV | Critical value |

| EDF | Empirical distribution function |

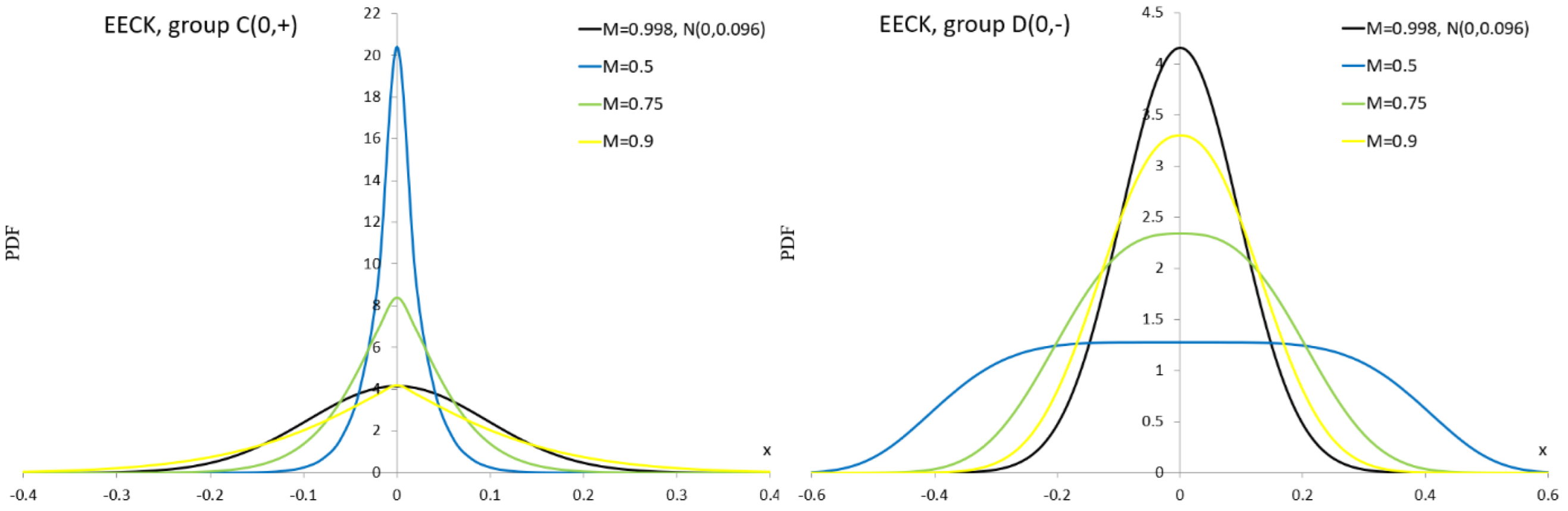

| EECK | Extended easily changeable kurtosis distribution |

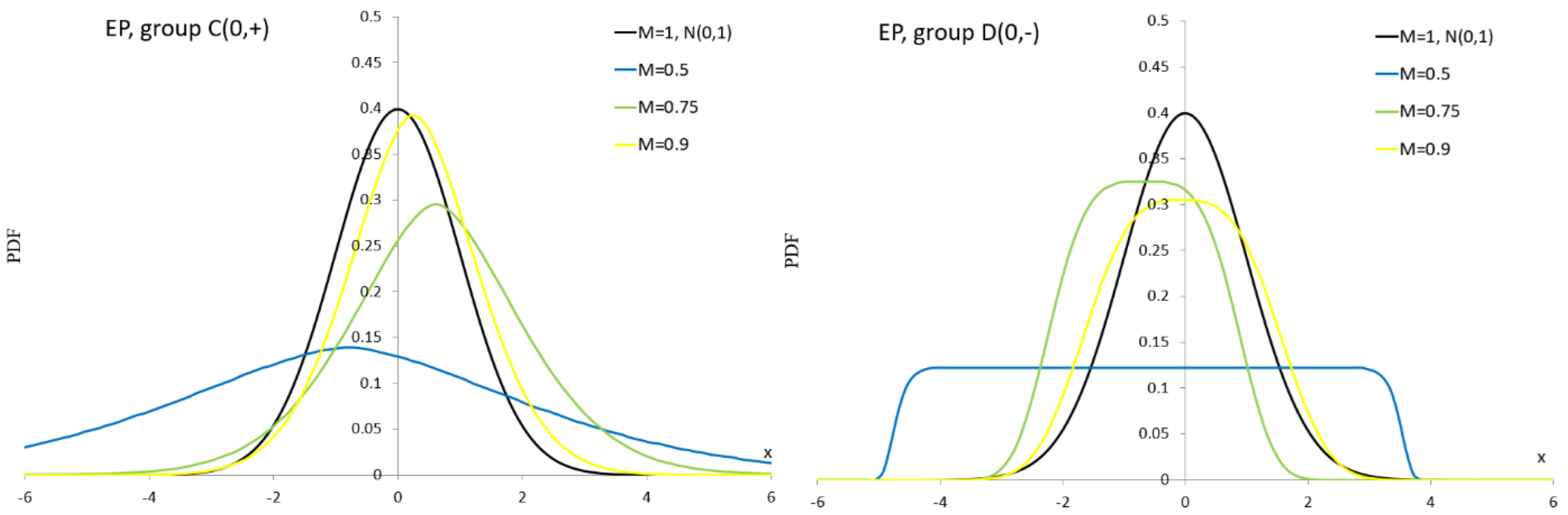

| EP | Exponential power distribution |

| ES | Edgeworth series |

| GoFT | Goodness-of-fit test |

| K | Kuiper test |

| KS | Kolmogorov–Smirnov test |

| LCN | Location contaminated normal distribution |

| LF | Lilliefors test |

| LM | Laplace mixture |

| M | Similarity measure |

| MA | Malakhov area |

| MCM | Modified Cramér–von Mises test |

| MP | Malakhov parabola |

| MSE | Mean square error |

| N | Normal distribution |

| NDPC | Normal distribution with plasticizing component distribution |

| n | Sample size |

| NM | Normal mixture distribution |

| P | Pearson distribution |

| PCM | Plasticizing component mixture distribution |

| Probability density function | |

| PKS | Parametrized KS test |

| PoT | Power of test |

| SB | Johnson SB distribution |

| SCN | scale contaminated normal distribution |

| SF | Shapiro–Francia test |

| SKS | Skewness-kurtosis-square measure |

| SS | number of non-empty squares |

| SU | Johnson SU distribution |

| SW | Shapiro–Wilk test |

| TS | Test size |

| TT | Total number of squares within the MA |

| W | Watson test |

| Skewness | |

| Excess kurtosis | |

| Diameter of circle, side of square |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Literature Review

| Article | Sample Sizes | Article | Sample Sizes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bonett and Seier [29] | 10, 20,…, 50, 100 | Afeez et al. [30] | 10, 30, 50, 100, 300, 500,1 000 |

| Aliaga et al. [31] | - | Marange and Qin [32] | 15, 30, 50, 80, 100, 150, 200 |

| Bontemps and Meddahi [33] | 100, 250, 500, 1000 | Sulewski [34] (2019) | 10, 12,…, 30, 40, 50 |

| Luceno [35] | 100 | Tavakoli et al. [36] | 5, 6,…, 15, 20, 25, 30, 40,50,…, 100 |

| Yazici and Yolacan [37] | 20, 30, 40, 50 | Mishra et al. [38] | , |

| Gel et al. [39] | 20, 50, 100 | Kellner and Celisse [40] | 50, 75, 100, 200, 300, 400 |

| Coin [41] | 20, 50, 200 | Wijekularathna et al. [42] | 5, 10, 20, 30, 50, 75, 100, 200, 500, 1000, 2000 |

| Brys et al. [43] | 100, 1000 | Sulewski [14] | 10, 14, 20 |

| Gel and Gastwirth [44] | 30, 50, 100 | Hernandez [24] | 5, 10,…, 30 |

| Romao et al. [45] | 25, 50, 100 | Khatun [46] | 10, 20, 25, 30, 40, 50, 100, 200, 300 |

| Razali and Wah [47] | 20, 30, 50, 100, 200,…, 500, 1000, 2000 | Arnastauskaitė et al. [48] | , ,…, |

| Noughabi and Arghami [49] | 10, 20, 30, 50 | Bayoud [50] | 10, 20,…, 50, 60, 80, 100 |

| Yap and Sim [51] | 10, 20, 30, 50, 100, 300, 500, 1000, 2000 | Uhm and Yi [52] | 10, 20, 30, 100, 200, 300 |

| Chernobai et al. [53] | Sulewski [18] | 20, 50, 100 | |

| Ahmad and Khan [54] | 10, 20,…, 50, 100, 200, 500 | Desgagné et al. [55] | 20, 50, 100, 200 |

| Mbah and Paothong [56] | 10, 20, 30, 50, 100, 200,…, 500, 1000, 2500, 5000 | Uyanto [27] | 10, 30, 50, 70, 100 |

| Torabi et al. [21] | 10, 20 | Ma et al. [28] | 10, 30, 50 |

| Feuerverger [57] | 200 | Giles [58] | 10, 25, 50, 100, 250, 500, 1000 |

| Nosakhare and Bright [59] | 5, 10,…, 50, 100 | Borrajo et al. [60] | 50, 100, 200, 500 |

| Desgagné and Lafaye de Micheaux [61] | 10, 12,…, 20, 50, 100, 200 | Terán-García and Pérez-Fernández [62] | 25, 900 |

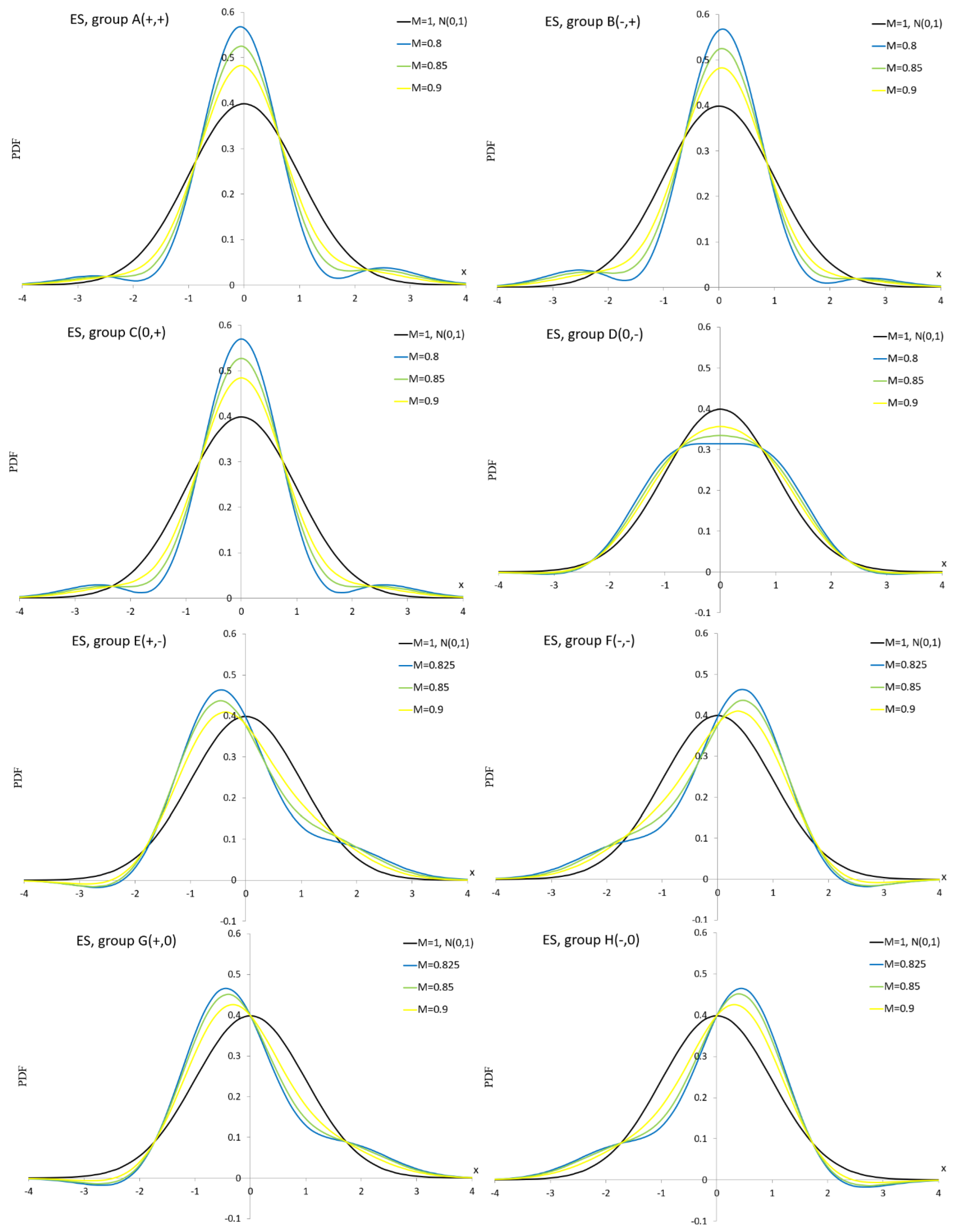

Appendix A.2. Edgeworth Series Distribution

| Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| (0.4, 3.33) | 0 | 1 | 0.4 | 3.33 | ||

| A | (0.3, 2.499) | 0 | 1 | 0.3 | 2.499 | |

| (0.2, 1.666) | 0 | 1 | 0.2 | 1.666 | ||

| (−0.4, 3.33) | 0 | 1 | −0.4 | 3.33 | ||

| B | (−0.3, 2.499) | 0 | 1 | −0.3 | 2.499 | |

| (−0.2, 1.666) | 0 | 1 | −0.2 | 1.666 | ||

| (0, 3.428) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3.428 | ||

| C | (0, 2.571) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2.571 | |

| (0, 1.71) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1.71 | ||

| (0, −3.428) | 0 | 1 | 0 | −3.428 | ||

| D | (0, −2.571) | 0 | 1 | 0 | −2.571 | |

| (0, −1.71) | 0 | 1 | 0 | −1.71 | ||

| (1.39, −0.067) | 0 | 1 | 1.39 | −0.067 | ||

| E | (1.175, −0.46) | 0 | 1 | 1.175 | −0.46 | |

| (0.775, −0.408) | 0 | 1 | 0.775 | −0.408 | ||

| (−1.39, −0.067) | 0 | 1 | −1.39 | −0.067 | ||

| F | (−1.175, −0.46) | 0 | 1 | −1.175 | −0.46 | |

| (−0.775, −0.408) | 0 | 1 | −0.775 | −0.408 | ||

| (1.391, 0) | 0 | 1 | 1.391 | 0 | ||

| G | (1.19, 0) | 0 | 1 | 1.19 | 0 | |

| (0.795, 0) | 0 | 1 | 0.795 | 0 | ||

| (−1.391, 0) | 0 | 1 | −1.391 | 0 | ||

| H | (−1.19, 0) | 0 | 1 | −1.19 | 0 | |

| (−0.795, 0) | 0 | 1 | −0.795 | 0 |

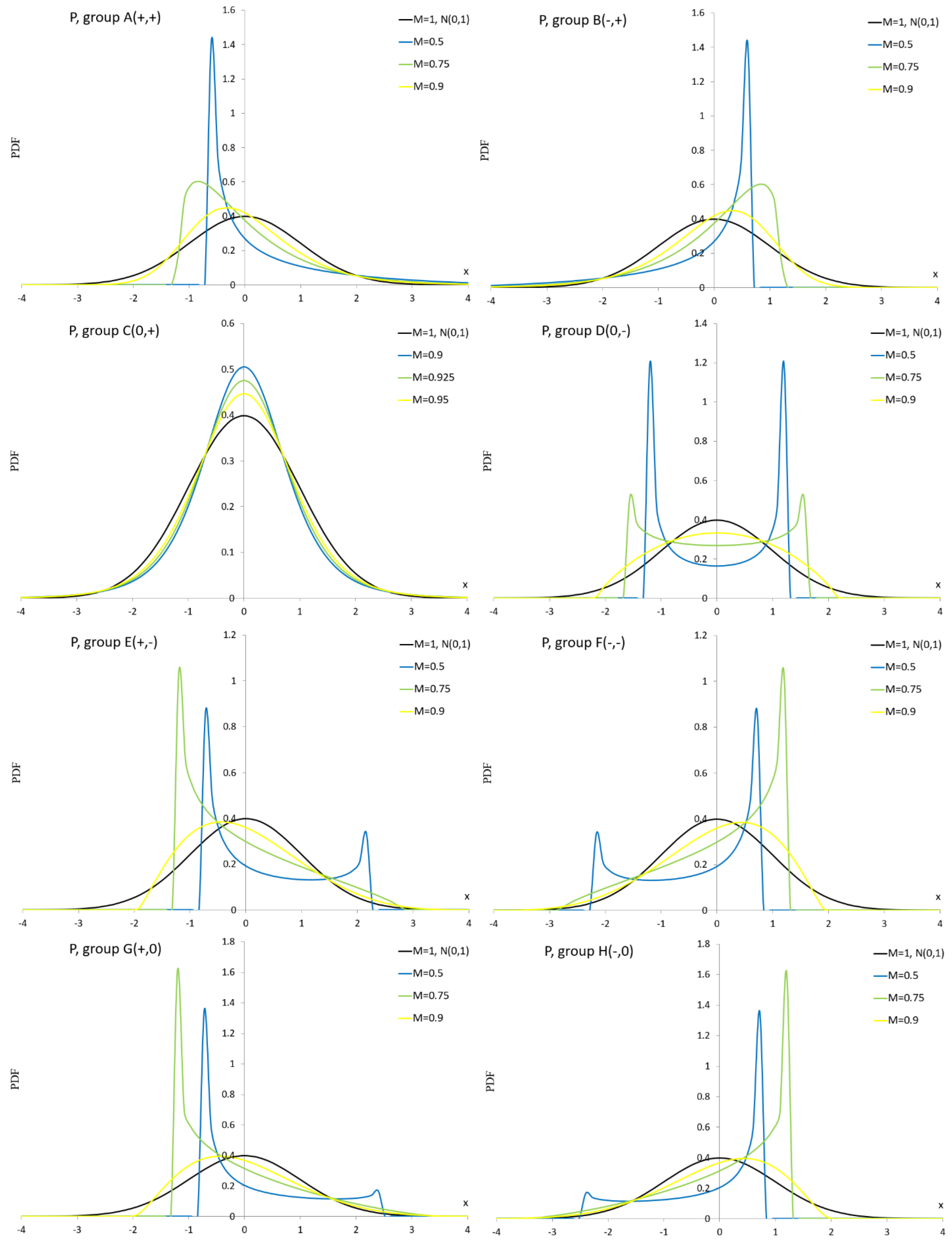

Appendix A.3. Pearson Distribution

| Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | (0, 0) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| (2.04, 4.1) | 0 | 1 | 2.04 | 4.1 | ||

| A | (1.62, 3.845) | 0 | 1 | 1.62 | 3.845 | |

| (0.9, 2) | 0 | 1 | 0.9 | 2 | ||

| (−2.04, 4.1) | 0 | 1 | −2.04 | 4.1 | ||

| B | (−1.62, 3.845) | 0 | 1 | −1.62 | 3.845 | |

| (−0.9, 2) | 0 | 1 | −0.9 | 2 | ||

| (0, 11.2) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 11.2 | ||

| C | (0, 3.65) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3.65 | |

| (0, 1.521) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1.521 | ||

| (0, −1.695) | 0 | 1 | 0 | −1.695 | ||

| D | (0, −1.315) | 0 | 1 | 0 | −1.315 | |

| (0, −0.89) | 0 | 1 | 0 | −0.89 | ||

| (0.985, −0.5) | 0 | 1 | 0.985 | −0.5 | ||

| E | (0.715, −0.475) | 0 | 1 | 0.715 | −0.475 | |

| (0.515, −0.2) | 0 | 1 | 0.515 | −0.2 | ||

| (−0.985, −0.5) | 0 | 1 | −0.985 | −0.5 | ||

| F | (−0.715, −0.475) | 0 | 1 | −0.715 | −0.475 | |

| (−0.515, −0.2) | 0 | 1 | −0.515 | −0.2 | ||

| (1.164, 0) | 0 | 1 | 1.164 | 0 | ||

| G | (0.879, 0) | 0 | 1 | 0.879 | 0 | |

| (0.578, 0) | 0 | 1 | 0.578 | 0 | ||

| (−1.164, 0) | 0 | 1 | −1.164 | 0 | ||

| H | (−0.879, 0) | 0 | 1 | −0.879 | 0 | |

| (−0.578, 0) | 0 | 1 | −0.578 | 0 |

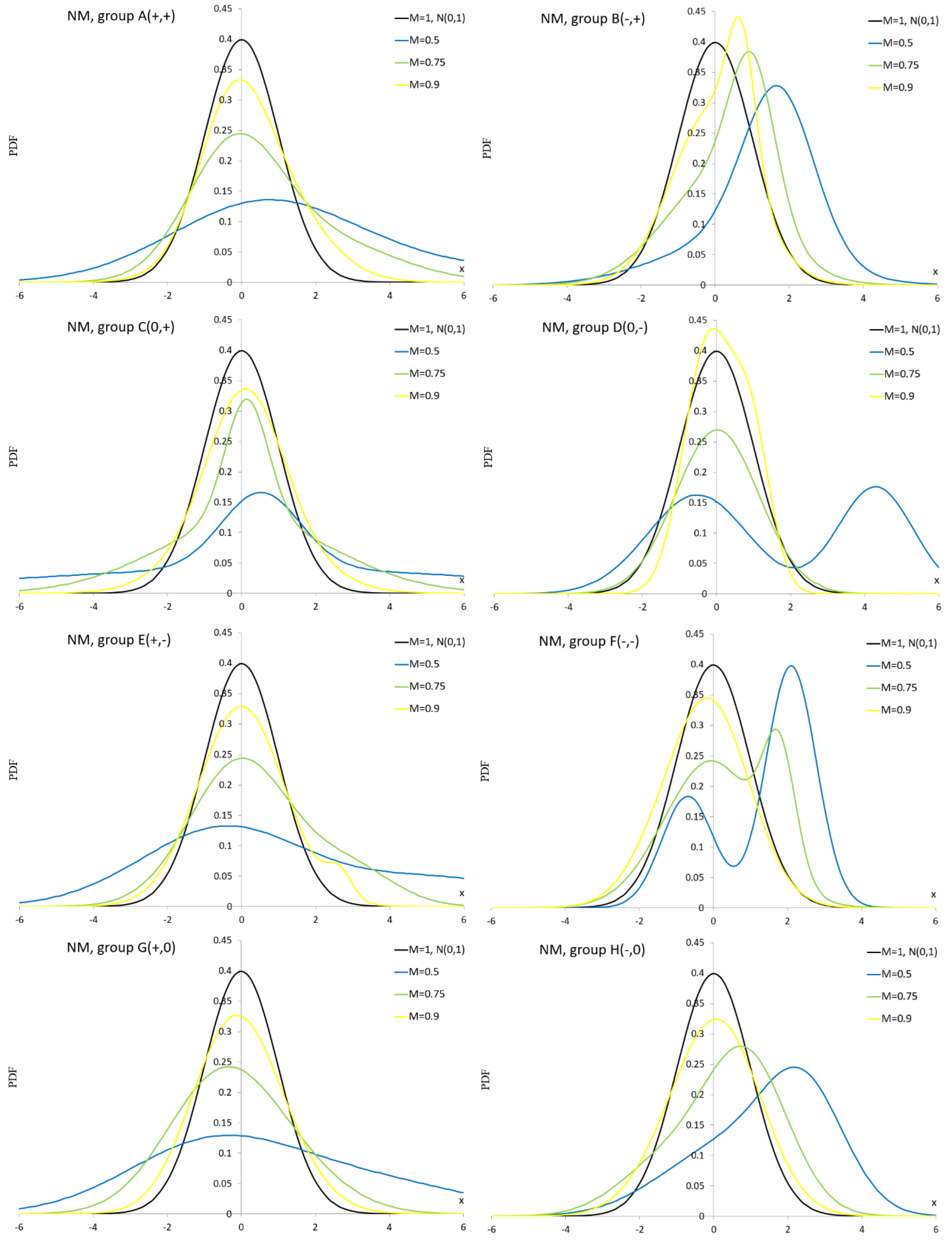

Appendix A.4. Normal Mixture Distribution

- normal for , for ,

- location contaminated normal (LCN) ,

- scale contaminated normal (SCN) .

| Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| (0.572, 2.472, 5.614, 3.454, 0.787) | 1.646 | 3.408 | 0.685 | 0.755 | ||

| A | (−0.215, 1.254, 1.979, 1.99, 0.639) | 0.577 | 1.883 | 0.645 | 0.502 | |

| (0.497, 1.376, −0.268, 0.884, 0.612) | 0.2 | 1.265 | 0.287 | 0.249 | ||

| (0.502, 2.019, 1.708, 0.953, 0.36) | 1.274 | 1.544 | −0.748 | 1.502 | ||

| B | (0.06, 1.437, 1.004, 0.609, 0.634) | 0.406 | 1.285 | −0.5 | 0.499 | |

| (0.709, 0.368, −0.072, 1.115, 0.193) | 0.079 | 1.06 | −0.301 | 0.15 | ||

| (0.519, 6.599, 0.519, 1.058, 0.665) | 0.519 | 5.416 | 0 | 1.398 | ||

| C | (0.137, 0.581, 0.137, 2.391, 0.294) | 0.137 | 2.034 | 0 | 1.054 | |

| (0.1, 0.988, 0.1, 1.543, 0.532) | 0.1 | 1.278 | 0 | 0.554 | ||

| (−0.511, 1.353, 4.293, 1.021, 0.551) | 1.645 | 2.681 | 0 | −1.28 | ||

| D | (2.707, 0.013, 0.017, 1.125, 0.238) | 0.657 | 1.509 | 0 | −1.001 | |

| (1.243, 0.621, −0.39, 0.811, 0.347) | 0.111 | 1.09 | 0 | −0.63 | ||

| (−0.475, 2.22, 5.318, 2.427, 0.721) | 1.141 | 3.457 | 0.5 | −0.204 | ||

| E | (−0.019, 1.369, 2.979, 1.15, 0.829) | 0.494 | 1.748 | 0.339 | −0.1 | |

| (2.635, 0.35, −0.015, 1.166, 0.038) | 0.086 | 1.253 | 0.137 | −0.075 | ||

| (−0.692, 0.705, 2.1, 0.679, 0.324) | 1.195 | 1.476 | −0.542 | −0.852 | ||

| F | (−0.055, 1.277, 1.781, 0.443, 0.775) | 0.358 | 1.377 | −0.3 | −0.5 | |

| (−0.09, 1.08, −1.581, 0.92, 0.9) | −0.239 | 1.155 | −0.071 | −0.042 | ||

| (2.686, 3.099, −0.964, 2.217, 0.471) | 0.755 | 3.232 | 0.4 | 0 | ||

| G | (−0.56, 1.465, 1.411, 1.45, 0.8) | −0.166 | 1.661 | 0.151 | 0 | |

| (−0.286, 1.114, 0.984, 1.105, 0.801) | −0.033 | 1.222 | 0.101 | 0 | ||

| (2.425, 1.101, 0.272, 1.693, 0.526) | 1.404 | 1.775 | −0.499 | 0 | ||

| H | (0.864, 1.125, −1.339, 1.241, 0.735) | 0.28 | 1.511 | −0.386 | 0 | |

| (0.429, 1.078, −0.364, 1.228, 0.434) | −0.02 | 1.23 | −0.1 | 0 |

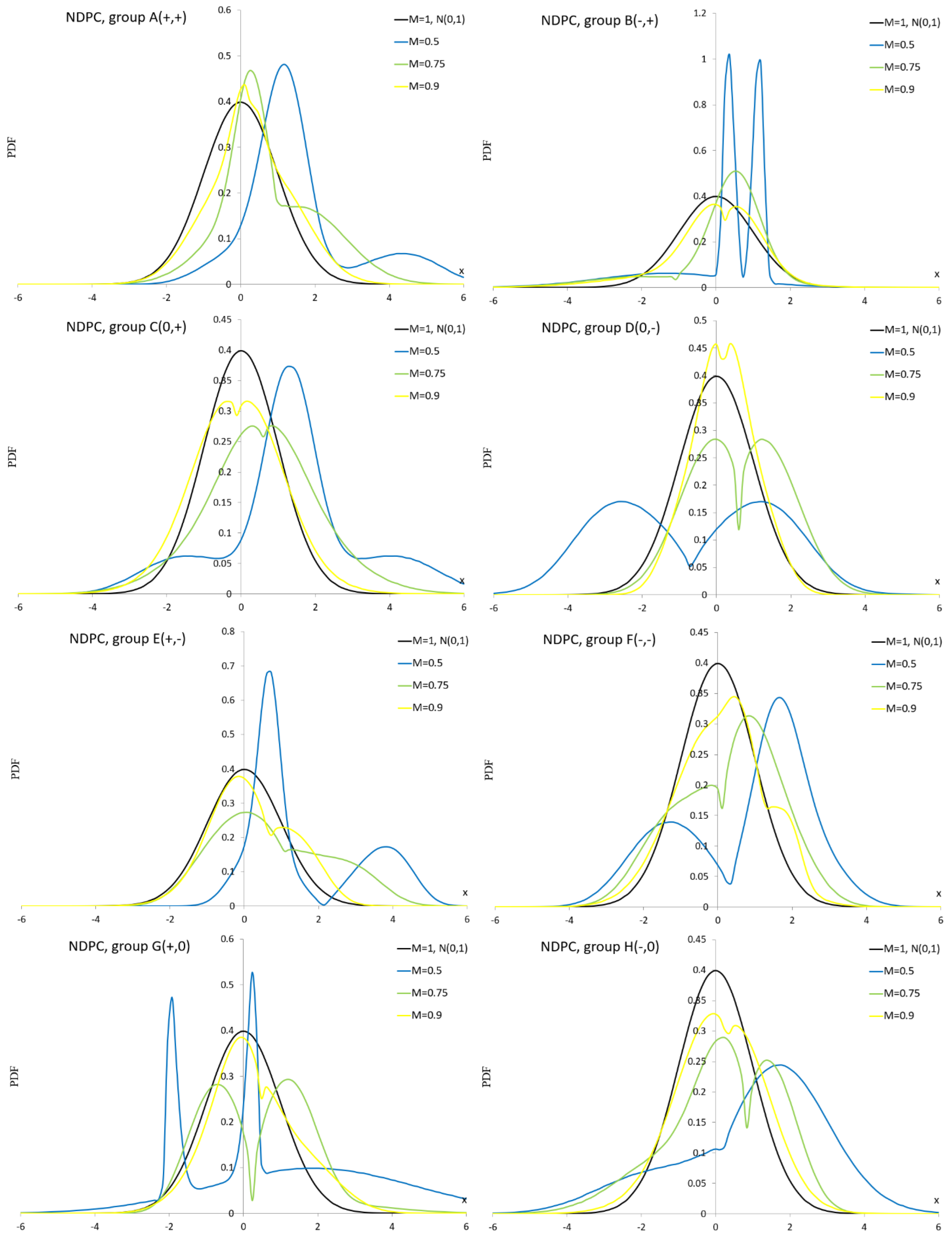

Appendix A.5. Normal Distribution with Plasticizing Component

| Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | () | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| () | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| (1.194, 0.601, 2.186, 2.592, 2,0.666) | 1.526 | 1.5 | 1.002 | 1.001 | ||

| A | (0.265, 0.415, 0.996, 1.541, 1.16, 0.313) | 0.767 | 1.288 | 0.426 | 0.152 | |

| (0.173, 0.358, 0.289, 1.268, 1.132, 0.198) | 0.266 | 1.104 | 0.056 | 0.071 | ||

| (−1.321, 1.842, 0.741, 0.459, 2.56, 0.287) | 0.15 | 1.4 | −1.764 | 3.3 | ||

| B | (0.539, 0.632, −1.078, 2.061, 1.174, 0.741) | 0.12 | 1.34 | −1.499 | 2.986 | |

| (−0.966, 1.824, 0.259, 0.889, 1.1, 0.26) | −0.059 | 1.305 | −0.899 | 1.999 | ||

| (1.308, 0.656, 1.308, 3.261, 2, 0.613) | 1.308 | 1.884 | 0 | 0.504 | ||

| C | (0.571, 1.023, 0.571, 1.962, 1.15, 0.505) | 0.571 | 1.508 | 0 | 0.325 | |

| (−0.097, 1.332, −0.097, 1.058, 1.1, 0.614) | −0.097 | 1.223 | 0 | 0.101 | ||

| (−0.692, 2.203, −0.692, 2.544, 1.759, 0.25) | −0.692 | 2.265 | 0 | −1 | ||

| D | (0.323, 1.312, 0.605, 1.335, 1.2, 0.01) | 0.602 | 1.266 | 0 | −0.587 | |

| (0.179, 0.494, 0.179, 1.163, 1.426, 0.443) | 0.179 | 0.862 | 0 | −0.202 | ||

| (0.675, 0.284, 2.122, 1.968, 2.104, 0.374) | 1.581 | 1.565 | 0.749 | −0.849 | ||

| E | (0.423, 1.032, 1.058, 2.077, 1.815, 0.494) | 0.744 | 1.544 | 0.311 | −0.667 | |

| (−0.134, 0.993, 0.671, 1.211, 1.479, 0.583) | 0.202 | 1.115 | 0.115 | −0.4 | ||

| (1.609, 0.59, 0.322, 2.194, 1.609, 0.309) | 0.72 | 1.784 | −0.491 | −0.728 | ||

| F | (0.617, 0.737, 0.129, 1.752, 1.465, 0.332) | 0.291 | 1.395 | −0.239 | −0.526 | |

| (−0.046, 1.156, 1.261, 0.799, 1.87, 0.876) | 0.116 | 1.191 | −0.1 | −0.2 | ||

| (1.88, 2.736, −0.848, 1.122, 6.437, 0.679) | 1.005 | 2.656 | 0.524 | 0 | ||

| G | (2.419, 1.56, 0.237, 1.384, 1.476, 0.074) | 0.398 | 1.409 | 0.35 | 0 | |

| (0.055, 0.702, 0.474, 1.586, 1.328, 0.473) | 0.276 | 1.191 | 0.31 | 0 | ||

| (1.642, 1.247, 0.202, 2.681, 1.428, 0.554) | 1 | 2.018 | −0.594 | 0 | ||

| H | (−1.246, 1.326, 0.858, 1.103, 1.242, 0.313) | 0.2 | 1.496 | −0.5 | 0 | |

| (−0.115, 1.286, 0.306, 1.091, 1.093, 0.465) | 0.11 | 1.189 | −0.1 | 0 |

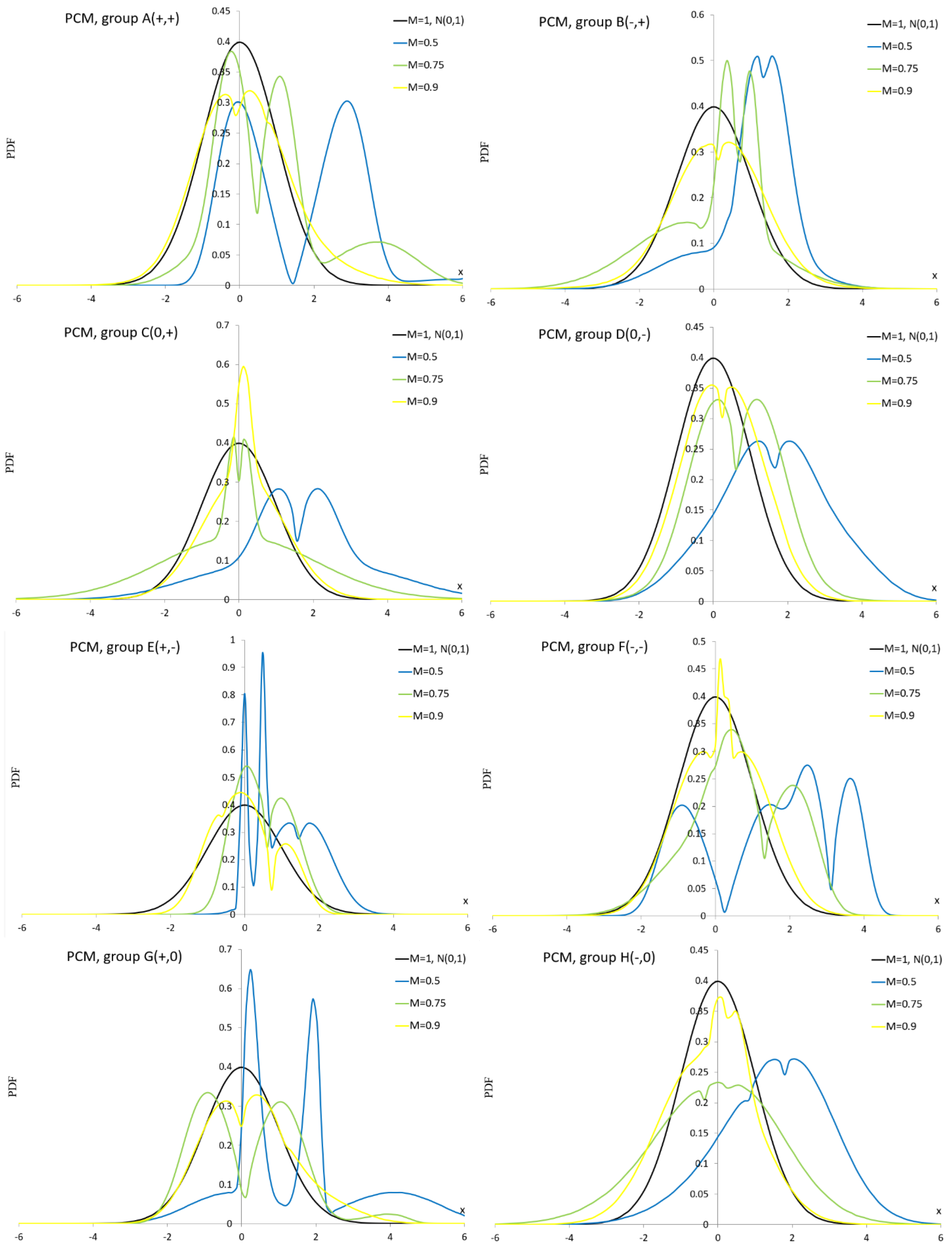

Appendix A.6. Plasticizing Component Mixture Distribution

| Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| () | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| (1.415, 1.684, 2.194, 11.252, 5.474, 2.331, 0.9) | 2.399 | 3.622 | 2.647 | 7.663 | ||

| A | (0.444, 0.899, 1.602, 1.653, 2.506, 1.876, 0.64) | 0.879 | 1.604 | 0.913 | 0.412 | |

| (−0.076, 1.056, 1.1, 0.701, 1.646, 1.095, 0.71) | 0.149 | 1.268 | 0.374 | 0.374 | ||

| (1.366, 0.572, 1.11, 0.502, 1.669, 1.253, 0.658) | 1.071 | 1.099 | −0.978 | 1.565 | ||

| B | (0.67, 0.425, 1.576, -0.323, 1.696, 1.05, 0.349) | 0.024 | 1.444 | −0.569 | 0.606 | |

| (−0.204, 2.209, 1.205, 0.133, 1.139, 1.05, 0.076) | 0.107 | 1.224 | −0.122 | 0.457 | ||

| (1.597, 2.518, 1.263, 1.596, 0.856, 1.285, 0.526) | 1.597 | 1.797 | 0 | 0.601 | ||

| C | (0.012, 0.274, 1.256, 0.012, 2.046, 1.01, 0.183) | 0.012 | 1.846 | 0 | 0.598 | |

| (0.127, 1.089, 1.01, 0.127, 0.183, 1.01, 0.863) | 0.127 | 1.01 | 0 | 0.401 | ||

| (1.631, 0.893, 1.05, 1.632, 2.104, 1.554, 0.498) | 1.632 | 1.488 | 0 | −0.268 | ||

| D | (0.639, 1.576, 1.167, 0.64, 1.085, 1.199, 0.163) | 0.64 | 1.12 | 0 | −0.251 | |

| (0.666, 1.123, 4.041, 0.233, 1.069, 1.05, 0.01) | 0.237 | 1.052 | 0 | −0.198 | ||

| (1.472, 0.782, 1.11, 0.236, 0.291, 3.203, 0.692) | 1.091 | 0.861 | 0.38 | −0.8 | ||

| E | (−0.196, 0.341, 1.064, 0.613, 0.758, 1.204, 0.153) | 0.489 | 0.734 | 0.201 | −0.7 | |

| (0.722, 0.703, 1.304, −0.57, 0.598, 1.05, 0.455) | 0.018 | 0.893 | 0.179 | −0.617 | ||

| (0.261, 1.419, 1.909, 3.099, 0.744, 1.567, 0.57) | 1.481 | 1.757 | −0.3 | −1.107 | ||

| F | (0.037, 1.295, 1.076, 1.316, 1.171, 1.654, 0.485) | 0.696 | 1.326 | −0.204 | −0.4 | |

| (0.201, 0.121, 1.573, 0.184, 1.177, 1.161, 0.066) | 0.185 | 1.087 | −0.003 | −0.331 | ||

| (1.088, 0.894, 3.782, 1.969, 2.71, 1.792, 0.55) | 1.484 | 1.793 | 0.6 | 0 | ||

| G | (1.515, 2.553, 3.55, 0.07, 1.328, 1.619, 0.07) | 0.171 | 1.359 | 0.501 | 0 | |

| (−0.034, 1.072, 1.159, 1.146, 1.51, 1.301, 0.756) | 0.254 | 1.238 | 0.401 | 0 | ||

| (0.816, 1.867, 1.24, 1.787, 1.272, 1.05, 0.278) | 1.517 | 1.475 | −0.302 | 0 | ||

| H | (−0.364, 1.889, 1.057, 0.29, 1.413, 1.05, 0.527) | −0.055 | 1.682 | −0.154 | 0 | |

| (0.286, 0.405, 1.27, -0.263, 1.261, 1.05, 0.112) | −0.202 | 1.188 | −0.128 | 0 |

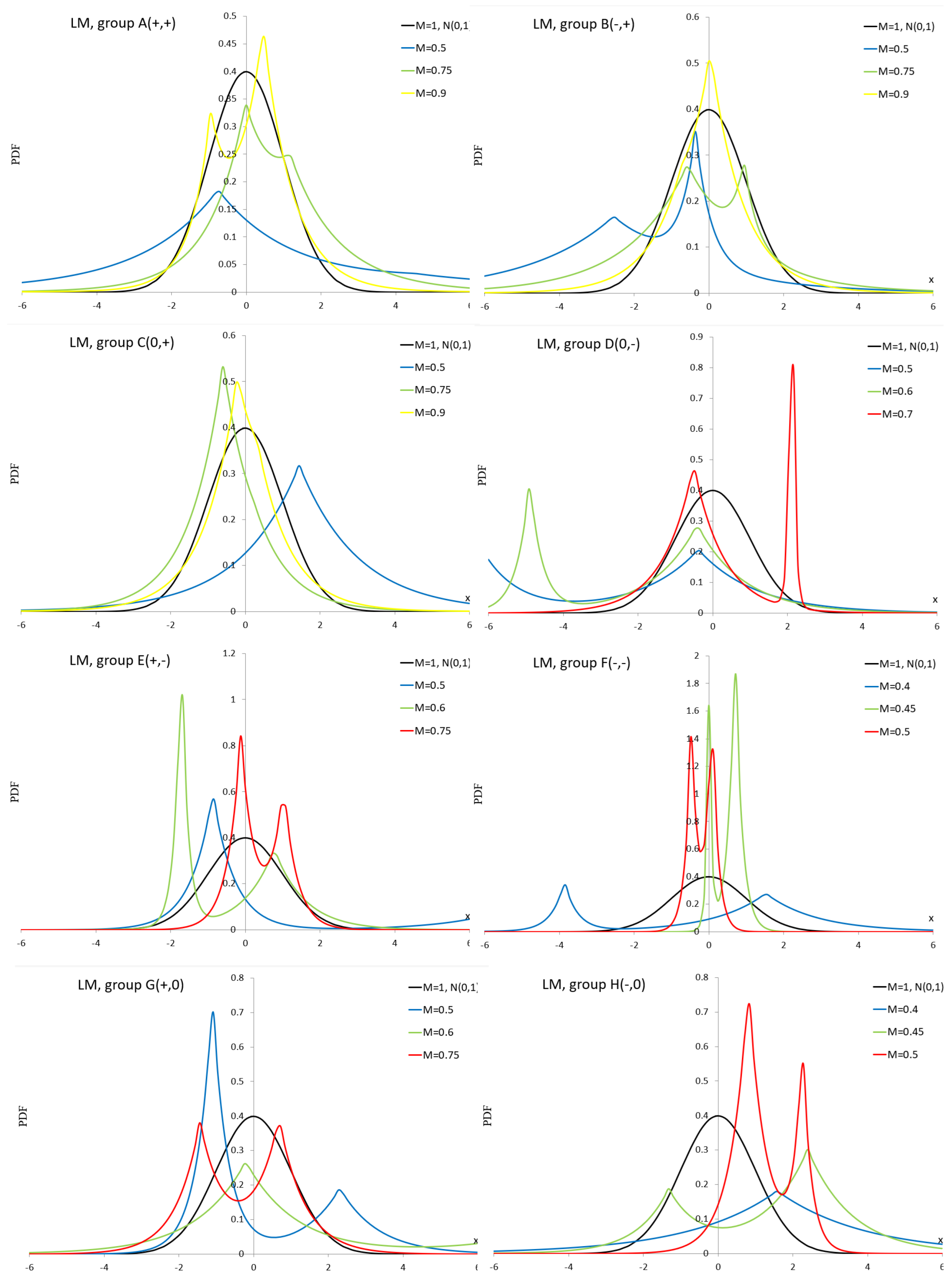

Appendix A.7. Laplace Mixture Distribution

| Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (4.521, 7.174, −0.757, 1.959, 0.313) | 0.895 | 6.594 | 1.172 | 9.074 | ||

| A | (1.169, 1.491, −0.019, 0.849, 0.56) | 0.646 | 1.863 | 0.4 | 3.454 | |

| (0.452, 0.818, −0.947, 0.482, 0.762) | 0.119 | 1.219 | 0.224 | 1.644 | ||

| (−0.358, 0.405, −2.549, 2.309, 0.234) | −2.036 | 3.018 | −0.407 | 3.5 | ||

| B | (0.94, 0.335, −0.571, 1.585, 0.122) | −0.387 | 2.164 | −0.202 | 3.136 | |

| (−0.736, 0.911, 0.04, 0.878, 0.132) | −0.062 | 1.275 | −0.034 | 2.773 | ||

| (1.445, 1.571, −2.516, 1.87, 1) | 1.445 | 2.222 | 0 | 3 | ||

| C | (0.246, 0.844, −0.59, 0.905, 0.043) | −0.554 | 1.287 | 0 | 2.894 | |

| (0.319, 0.86, −0.21, 0.874, 0.222) | −0.092 | 1.251 | 0 | 2.815 | ||

| (−6.131, 0.945, −0.386, 1.54, 0.366) | −2.487 | 3.364 | 0 | −0.648 | ||

| D | (−4.898, 0.343, −0.415, 1.234, 0.29) | −1.716 | 2.523 | 0 | −0.597 | |

| (2.115, 0.07, −-0.512, 0.822, 0.208) | 0.034 | 1.486 | 0 | −0.005 | ||

| (7.186, 1.509, -0.869, 0.58, 0.309) | 1.62 | 3.966 | 1.005 | −0.403 | ||

| E | (−1.711, 0.177, 0.773, 0.823, 0.421) | −0.274 | 1.522 | 0.5 | −0.32 | |

| (1.023, 0.358, −0.118, 0.348, 0.428) | 0.37 | 0.753 | 0.15 | −0.014 | ||

| (−3.863, 0.348, 1.522, 1.359, 0.248) | 0.184 | 2.872 | −0.18 | −0.556 | ||

| F | (0.006, 0.065, 0.703, 0.189, 0.227) | 0.545 | 0.378 | −0.17 | −0.286 | |

| (−0.466, 0.161, 0.08, 0.159, 0.48) | −0.182 | 0.354 | −0.05 | −0.2 | ||

| (2.309, 1.022, −1.1, 0.418, 0.391) | 0.233 | 1.949 | 0.85 | 0 | ||

| G | (−0.208, 1.335, 7.917, 1.899, 0.712) | 2.132 | 4.261 | 0.839 | 0 | |

| (0.679, 0.702, −1.434, 0.642, 0.532) | −0.31 | 1.422 | 0.036 | 0 | ||

| (−9.234, 0.124, 1.581, 2.321, 0.161) | −0.159 | 4.983 | −0.556 | 0 | ||

| H | (−1.322, 0.83, 2.398, 1.181, 0.291) | 1.317 | 2.287 | −0.1 | 0 | |

| (0.81, 0.479, 2.254, 0.229, 0.736) | 1.191 | 0.878 | −0.032 | 0 |

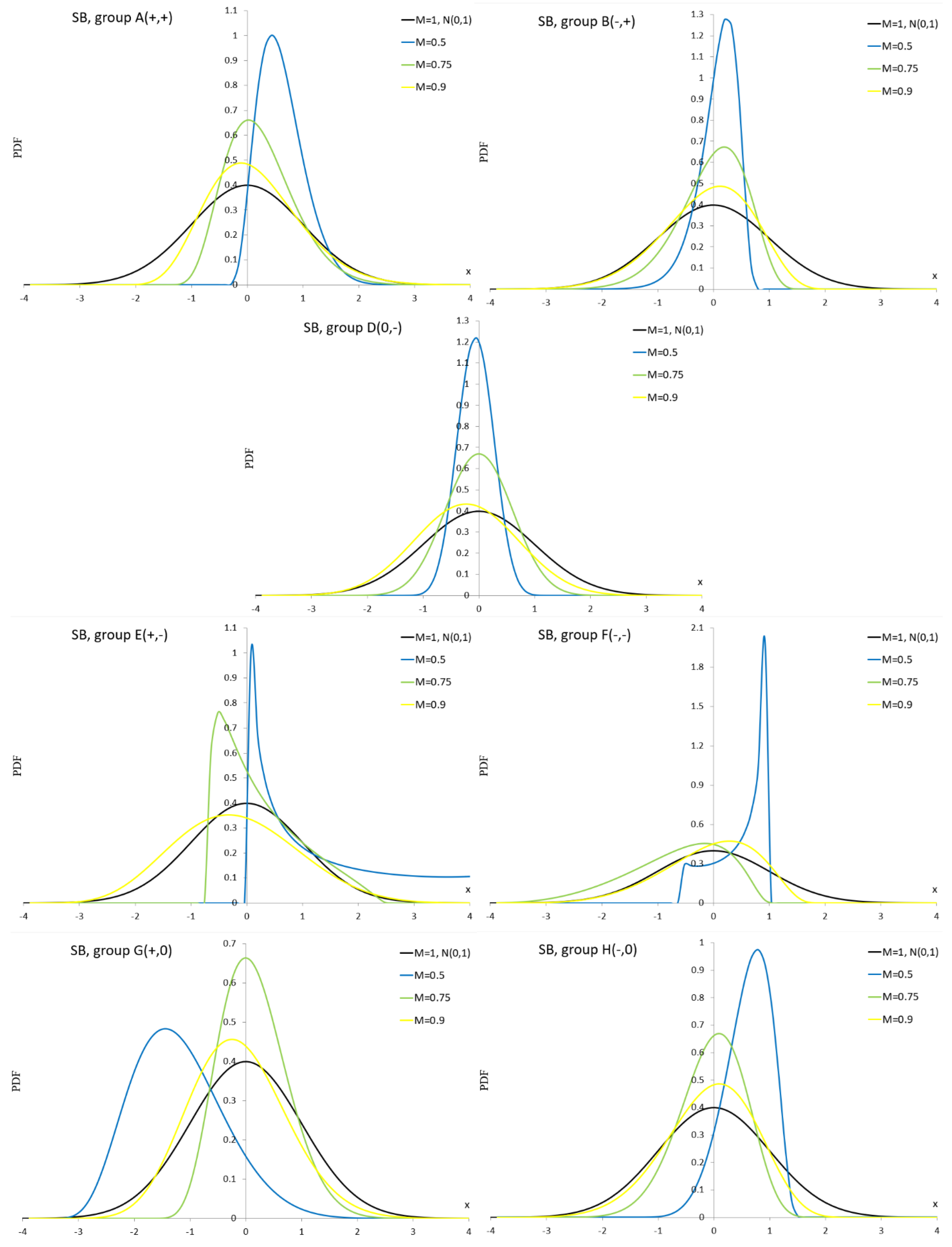

Appendix A.8. Johnson SB Distribution

| Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1.972, 1.819, −0.45, 4) | 0.613 | 0.411 | 0.649 | 0.3 | ||

| A | (2.482, 2.23, −1.665, 7.423) | 0.237 | 0.618 | 0.584 | 0.298 | |

| (3.092, 2.702, −2.908, 12.271) | 0.132 | 0.832 | 0.518 | 0.267 | ||

| (−4.086, 2.097, −5.424, 6.348) | 0.074 | 0.351 | −1 | 1.488 | ||

| B | (−2.614, 2.258, −5.722, 7.58) | −0.021 | 0.611 | −0.6 | 0.341 | |

| (−1.992, 2.198, −6.446, 8.974) | −0.129 | 0.823 | −0.485 | 0.099 | ||

| (0, 3.149, −2.116, 4.115) | −0.059 | 0.319 | 0 | −0.176 | ||

| D | (0, 3.958, −4.707, 9.414) | 0 | 0.585 | 0 | −0.117 | |

| (0, 4.304, −8.154, 15.856) | −0.227 | 0.909 | 0 | −0.1 | ||

| (0.664, 0.45, −0.027, 4.679) | 1.377 | 1.38 | 0.856 | −0.558 | ||

| E | (0.834, 0.754, −0.727, 3.258) | 0.26 | 0.726 | 0.788 | −0.25 | |

| (0.867, 2.297, −4.627, 10.828) | −0.18 | 1.095 | 0.2 | −0.227 | ||

| (−0.716, 0.448, −0.622, 1.618) | 0.534 | 0.47 | −0.931 | −0.4 | ||

| F | (−1.044, 1.22, −4.394, 5.493) | −0.665 | 0.88 | −0.603 | −0.145 | |

| (−1.202, 1.515, −4.252, 6.217) | −0.065 | 0.837 | −0.522 | −0.1 | ||

| (1.64, 2.044, −3.761, 8.045) | −1.199 | 0.819 | 0.452 | 0 | ||

| G | (1.825, 2.345, −1.984, 6.623) | 0.145 | 0.596 | 0.401 | 0 | |

| (2.952, 4.082, −-5.487, 16.27) | −0.135 | 0.87 | 0.24 | 0 | ||

| (−1.357; 1.565; −1.601; 3.202) | 0.605 | 0.41 | −0.563 | 0 | ||

| H | (−2.046; 2.695; −5.081; 7.468) | −0.032 | 0.592 | −0.354 | 0 | |

| (−2.068; 2.73; −7.098; 10.398) | −0.07 | 0.814 | −0.35 | 0 |

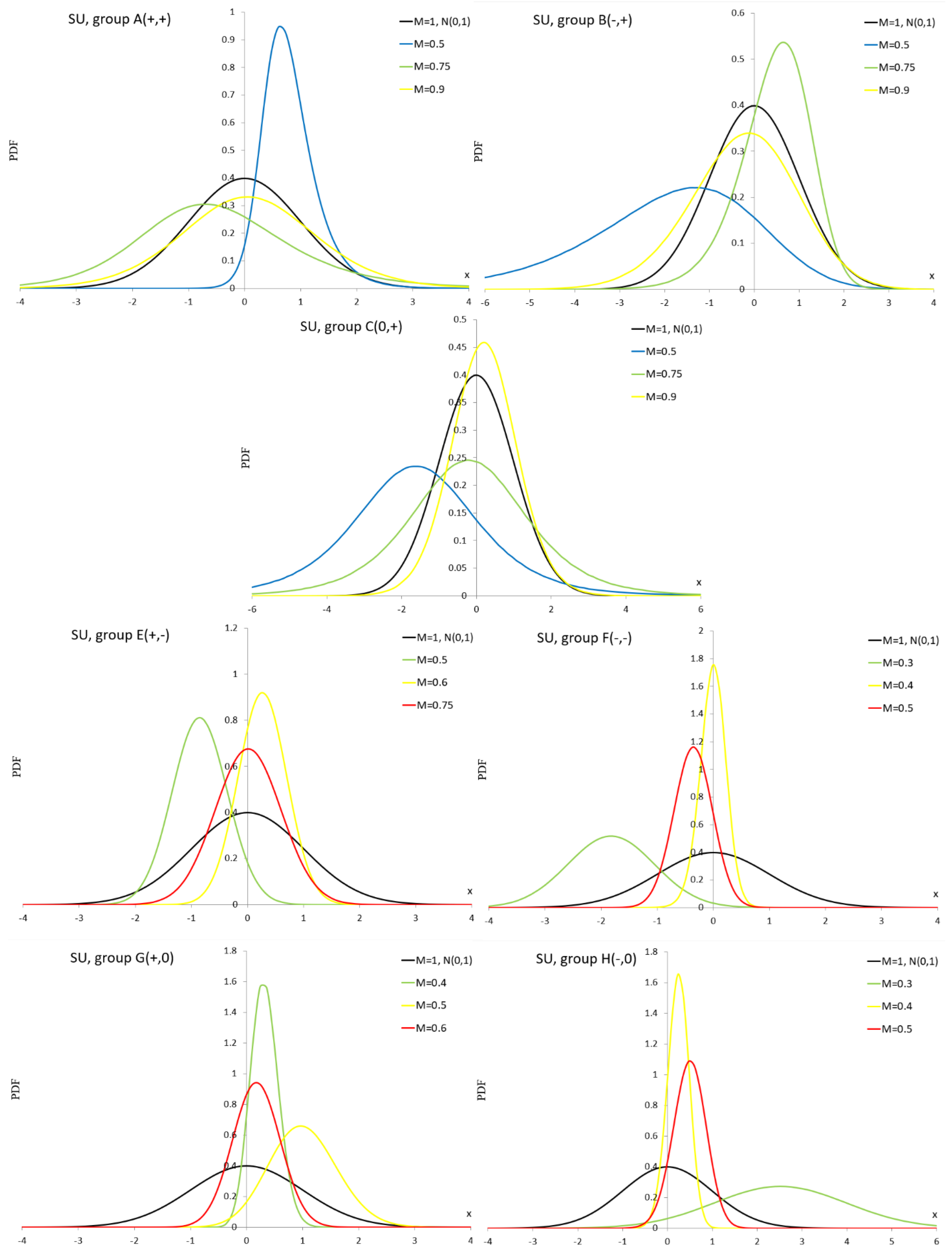

Appendix A.9. Johnson SU Distribution

| Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (−1.246, 2.021, 0.257, 0.731) | 0.800 | 0.501 | 1.014 | 2.911 | ||

| A | (−0.569, 2.063, −1.301, 2.625) | −0.477 | 1.499 | 0.493 | 1.720 | |

| (−0.11, 2.762, −0.069, 3.319) | 0.072 | 1.286 | 0.049 | 0.648 | ||

| (2.502, 2.889, 2.029, 3.828) | −1.949 | 2 | −0.8 | 1.455 | ||

| B | (2.564, 3.308, 2.137, 1.902) | 0.435 | 0.8 | −0.636 | 0.926 | |

| (2.296, 5.558,2.36,6.031) | −0.246 | 1.2 | −0.218 | 0.2 | ||

| (0, 1.821, −1.617, 3.096) | −1.617 | 1.992 | 0 | 2 | ||

| C | (0, 1.829, −0.205, 2.967) | −0.205 | 1.897 | 0 | 1.97 | |

| (0, 3.372, 0.204, 2.935) | 0.204 | 0.91 | 0 | 0.403 | ||

| (−22.518, 45.262, −11.095, 19.766) | −0.848 | 0.492 | 0.031 | −0.007 | ||

| E | (1.29, 40.539, −0.294, −17.564) | 0.155 | 0.484 | 0.491 | −0.784 | |

| (0.244, 21.027, −0.134, −12.383) | 0.01 | 0.59 | 0.002 | −0.007 | ||

| (0.861, 18.997, −1.158, 14.674) | −1.824 | 0.774 | −0.011 | −0.005 | ||

| F | (0.756, 3.676, 0.166, 0.819) | −0.010 | 0.236 | −0.359 | −0.450 | |

| (13.843, 36.36, 4.174, 11.623) | −0.360 | 0.343 | −0.030 | −0.077 | ||

| (−9.342, 11.021, −1.575, 1.981) | 0.32 | 0.25 | 0.207 | 0 | ||

| G | (−23.944, 18.041, −8.486, 5.409) | 1.009 | 0.606 | 0.15 | 0 | |

| (−9.349, 85.071, −3.763, 35.754) | 0.174 | 0.423 | 0.004 | 0 | ||

| (0.738, 49.723, 3.6, 73.029) | 2.516 | 1.469 | −0.001 | 0 | ||

| H | (2.547, 7.276, 0.835, 1.65) | 0.24 | 0.243 | −0.141 | 0 | |

| (4.211, 10.507, 1.959, 3.55) | 0.491 | 0.367 | −0.11 | 0 |

Appendix A.10. Extended Easily Changeable Kurtosis Distribution

| Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (46.018, 1.043) | 0 | 0.032 | 0 | 2.256 | ||

| C | (40.914, 1.366) | 0 | 0.06 | 0 | 0.921 | |

| (10.676, 1.184) | 0 | 0.128 | 0 | 0.912 | ||

| (60.495, 4.846) | 0 | 0.244 | 0 | −0.921 | ||

| D | (48.76, 2.738) | 0 | 0.15 | 0 | −0.51 | |

| (48.76, 2.211) | 0 | 0.115 | 0 | −0.238 |

Appendix A.11. Exponential Power Distribution

| Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (−0.796, 2.985, 1.609) | −0.796 | 3.257 | 0 | 0.536 | ||

| C | (90.611, 1.385, 1.695) | 0.611 | 1.478 | 0 | 0.386 | |

| (90.251, 1.033, 1.785) | 0.251 | 1.079 | 0 | 0.253 | ||

| (−0.611, 3.71, 28.792) | −0.611 | 2.368 | 0 | −1.188 | ||

| D | (−0.673, 1.198, 3.828) | −0.673 | 0.994 | 0 | −0.783 | |

| (−0.05, 1.272, 3.117) | −0.05 | 1.11 | 0 | −0.619 |

Appendix A.12. More Important R Codes

# Pseudo-random numbers generators (PRNGs)

# 1) Edgeworth series (ES)

# PDF as auxiliary function

dES=function(x,a,b) {

if(b>=a*a-2) return(dnorm(x,0,1)*(1+a*(x^3-3*x)/6+b*(x^4-6*x^2+3)/24))

else return("error")

}

# PRNG

rES=function(n,a,b){

if(b>=a*a-2){

wyn=numeric(n)

e=optimize(function(x) dES(x,a,b),interval=c(-5,5), maximum=1)$maximum

d=dES(e,a,b)

for (i in 1:n){

R1 = runif(1,-5,5); R2 = runif(1,0,d); w = dES(R1,a,b)

while(w<R2){

R1 = runif(1,-5,5); R2 = runif(1,0,d); w = dES(R1,a,b)

}

wyn[i]=R1

}

return(sort(wyn))

}

else return("error")

}

# 2) PRNG of Pearson (P)

library(PearsonDS)

rP = function(n, a, b) return(sort(rpearson(n,moments=c(0,1,a,b+3))))

# 3) PRNG of normal mixture (NM)

rNM = function(n, a1, b1, a2, b2, w) {

x = ifelse(runif(n, 0, 1) < w, rnorm(n, a1, b1), rnorm(n, a2, b2))

return(sort(x))

}

# 4) PRNG of normal distribution with plasticizing component (NDPC)

library(PSDistr)

rNDPC=function(n, a1, b1, a2, b2, c, w) {

x=ifelse(runif(n, 0, 1)< w,rnorm(n, a1, b1),rpc(n,a2,b2,c))

return(sort(x))

}

# 5) PRNG of plasticizing component mixture (PCM)

library(PSDistr)

rPCM = function(n, a1, b1, c1, a2, b2, c2, w) {

x = ifelse(runif(n, 0, 1) < w, rpc(n, a1, b1, c1), rpc(n, a2, b2, c2))

return(sort(x))

}

# 6) PRNG of Laplace mixture (LM)

library(LaplacesDemon)

rLM=function(n, a1, b1, a2, b2, w) {

x=ifelse(runif(n, 0, 1)< w,rlaplace(n, a1, b1),rlaplace(n, a2, b2))

return(sort(x))

}

# 7) PRNG of Johnson SB (SB)

library(ExtDist)

rSB=function(n, a, b, c, d) return(sort(rJohnsonSB(n,a,b,c,d)))

# 8) PRNG of Johnson SU (SU)

library(ExtDist)

rSU=function(n, a, b, c, d) return(sort(rJohnsonSU(n,a,b,c,d)))

# 9) extended easily changeable kurtosis (EECK)

# auxiliary functions

H=function(p,q) return(2*gamma(p+1)*gamma(1+1/q)/gamma(1+p+1/q))

dEECK = function(x,p,q) ifelse(abs(x)<=1,((1-abs(x)^q)^p)/H(p,q),0)

# PRNG of EECK

rEECK=function(n,p,q){

wyn=numeric(n)

e=optimize(function(x) dEECK(x,p,q),interval=c(-1,1), maximum=1)$maximum

d=dEECK(0,p,q)

for (i in 1:n){

R1 = runif(1,-1,1); R2 = runif(1,0,d); w = dEECK(R1,p,q)

while(w<R2){

R1 = runif(1,-1,1); R2 = runif(1,0,d); w = dEECK(R1,p,q)

}

wyn[i]=R1

}

return(sort(wyn))

}

# 10) exponential power (EP)

library(LaplacesDemon)

rEP =function(n,a,b,c) return(sort(rpe(n,a,b,c)))

# Parametrized Kolmogorov - Smirnow test statistic with parameters a, b

PKS = function(x,a,b) {

n=length(x)

z = (x - mean(x)) / (sd(x))

CDF = pnorm(z,0,1)

ad = max((seq(z) - a) / (n - a - b + 1) - CDF)

ag = max(CDF - (seq(z) - a - 1) / (n - a - b + 1))

return(max(ad, ag))

}

#critical values

n = 10 # sample size

alpha = 0.05 # significance level

rep1 = 10 ^ 6 # number of repeats

res = numeric(rep1) # statistic values

numer = (rep1 - alpha * rep1) # appropriate quantile

a=0; b=1 # parameters of the PKS statistic

# critical value (cv)

for (i in 1:rep1) {

print(i)

data = sort(rnorm(n, 0, 1))

res[i]=PKS(data, a, b)

}

res=sort(res)

cv=res[numer] # cv

# power study for a given alternative

rep2 = 10 ^ 5 # number of repeats

pow = 0

for (i in 1:rep2){

print(i)

# generate sample from alternative distribution

# data=sort(rnorm(n,0,1)) # test size

data = sort(rNM(n, 0.572, 2.472, 5.614, 3.454, 0.787))

if (PKS(data, a, b) > cv) pow = pow + 1

}

power = pow / rep2

power

References

- Kolmogorov, A.N. Sulla Determinazione Empirica di una Legge di Distribuzione. G. Dell’Istituto Ital. Degli Attuari 1933, 4, 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov, N.V. Tabled distribution of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistic (sample). Ann. Math. Stat. 1948, 19, 279–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramér, H. On the Composition of Elementary Errors. Scand. Actuar. J. 1928, 1, 13–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Mises, R.E. Wahrscheinlichkeit, Statistik und Wahrheit; Julius Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Lilliefors, H.W. On the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for normality with mean and variance unknown. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1967, 62, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, N.H. Tests concerning random points on a circle. Proc. K. Ned. Akad. Van Wet. Ser. A 1960, 63, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, G.S. Goodness-of-fit tests on a circle (Part II). Biometrika 1962, 49, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.W.; Darling, D.A. Asymptotic Theory of Certain “Goodness-of-Fit” Criteria Based on Stochastic Processes. Ann. Math. Stat. 1952, 23, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, H.L.; Khamis, H.J.; Lamb, R.E. Modified Kolmogorov–Smirnov Tests of Goodness of Fit. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 1984, 13, 293–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamis, H.J. The δ-Corrected Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test for Goodness of Fit. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 1990, 24, 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamis, H.J. The δ-Corrected Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test with Estimated Parameters. J. Nonparametric Stat. 1992, 2, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamis, H.J. A Comparative Study of the δ-Corrected Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test. J. Appl. Stat. 1993, 20, 401–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, G. Statistical Estimates and Transformed Beta Variables; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Sulewski, P. Modified Lilliefors goodness-of-fit test for normality. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 2020, 51, 1199–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulewski, P. Two component modified Lilliefors test for normality. Equilib. Q. J. Econ. Econ. Policy 2021, 16, 429–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulewski, P.; Stoltmann, D. Modified Cramér–von Mises goodness-of-fit test for normality. Stat. Rev. 2023, 70, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filliben, J.J. The Probability Plot Correlation Coefficient Test for Normality. Technometrics 1975, 17, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulewski, P. Two-piece power normal distribution. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 2021, 50, 2619–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malachov, A.N. A Cumulant Analysis of Random Non-Gaussian Processes and Their Transformations; Soviet Radio: Moscow, Russia, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban, M.D.; Castellanos, M.E.; Morales, D.; Vajda, I. Monte Carlo Comparison of Four Normality Tests Using Different Entropy Estimates. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 2001, 30, 285–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, H.; Montazeri, N.H.; Grane, A. A test of normality based on the empirical distribution function. SORT 2016, 40, 55–88. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, F.F.; Koehler, K.J. Goodness-of-Fit Tests Based on P–P Probability Plots. Technometrics 1990, 32, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauczi, E. A study of the quantile correlation test of normality. Test Off. J. Span. Soc. Stat. Oper. Res. 2009, 18, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, H. Testing for Normality: What Is the Best Method. Forsch. Res. Rep. 2021, 6, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality. Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Francia, R.S. An approximate analysis of variance test for normality. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1972, 67, 215–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyanto, S.S. An extensive comparison of 50 univariate goodness-of-fit tests for normality. Austrian J. Stat. 2022, 51, 45–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Kitani, M.; Murakami, H. On modified Anderson–Darling test statistics with asymptotic properties. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 2024, 53, 1420–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonett, D.G.; Seier, E. A Test of Normality with High Uniform Power. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2002, 40, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afeez, B.M.; Maxwell, O.; Otekunrin, O.; Happiness, O. Selection and Validation of Comparative Study of Normality Test. Am. J. Math. Stat. 2018, 8, 190–201. [Google Scholar]

- Aliaga, A.M.; Martínez-González, E.; Cayón, L.; Argüeso, F.; Sanz, J.L.; Barreiro, R.B. Goodness-of-Fit Tests of Gaussianity: Constraints on the Cumulants of the MAXIMA Data. New Astron. Rev. 2003, 47, 821–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marange, C.; Qin, Y. An empirical likelihood ratio based comparative study on tests for normality of residuals in linear models. Adv. Methodol. Stat. 2019, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bontemps, C.; Meddahi, N. Testing Normality: A GMM Approach. J. Econom. 2005, 124, 149–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulewski, P. Modification of Anderson–Darling goodness-of-fit test for normality. Afinidad 2019, 76, 588. [Google Scholar]

- Luceno, A. Fitting the generalized Pareto distribution to data using maximum goodness-of-fit estimators. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2006, 51, 904–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, M.; Arghami, N.; Abbasnejad, M. A goodness-of-fit test for normality based on Balakrishnan–Sanghvi information. J. Iran. Stat. Soc. 2019, 18, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazici, B.; Yolacan, S.A. Comparison of various tests of normality. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2007, 77, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Pandey, C.M.; Singh, U.; Gupta, A.; Sahu, C.; Keshri, A. Descriptive statistics and normality tests for statistical data. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2019, 22, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gel, Y.R.; Miao, W.; Gastwirth, J.L. Robust Directed Tests of Normality against Heavy-Tailed Alternatives. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2007, 51, 2734–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellner, J.; Celisse, A. A One-Sample Test for Normality with Kernel Methods. Bernoulli 2019, 25, 1816–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coin, D. A Goodness-of-Fit Test for Normality Based on Polynomial Regression. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2008, 52, 2185–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijekularathna, D.K.; Manage, A.B.; Scariano, S.M. Power analysis of several normality tests: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 2020, 51, 757–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brys, G.; Hubert, M.; Struyf, A. Goodness-of-Fit Tests Based on a Robust Measure of Skewness. Comput. Stat. 2008, 23, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gel, Y.R.; Gastwirth, J.L. A Robust Modification of the Jarque–Bera Test of Normality. Econ. Lett. 2008, 99, 30–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romao, X.; Delgado, R.; Costa, A. An empirical power comparison of univariate goodness-of-fit tests of normality. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2010, 80, 545–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatun, N. Applications of Normality Test in Statistical Analysis. Open J. Stat. 2021, 11, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, N.M.; Wah, Y.B. Power comparisons of Shapiro–Wilk, Kolmogorov–Smirnov, Lilliefors and Anderson–Darling tests. J. Stat. Model. Anal. 2011, 2, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Arnastauskaitė, J.; Ruzgas, T.; Bražėnas, M. An Exhaustive Power Comparison of Normality Tests. Mathematics 2021, 9, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noughabi, H.A.; Arghami, N.R. Monte Carlo comparison of seven normality tests. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2011, 81, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayoud, H.A. Tests of Normality: New Test and Comparative Study. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 2021, 50, 4442–4463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, B.W.; Sim, C.H. Comparisons of various types of normality tests. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2011, 81, 2141–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhm, T.; Yi, S. A comparison of normality testing methods by empirical power and distribution of p-values. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 2023, 52, 4445–4458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernobai, A.; Rachev, S.T.; Fabozzi, F.J. Composite Goodness-of-Fit Tests for Left-Truncated Loss Samples. In Handbook of Financial Econometrics and Statistics; Lee, C.-F., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 575–596. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, F.; Khan, R.A. A Power Comparison of Various Normality Tests. Pak. J. Stat. Oper. Res. 2015, 11, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desgagné, A.; Lafaye de Micheaux, P.; Ouimet, F. Goodness-of-Fit Tests for Laplace, Gaussian and Exponential Power Distributions Based on λ-th Power Skewness and Kurtosis. Statistics 2022, 56, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbah, A.K.; Paothong, A. Shapiro–Francia test compared to other normality tests using expected p-value. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2015, 85, 3002–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuerverger, A. On Goodness of Fit for Operational Risk. Int. Stat. Rev. 2016, 84, 434–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, D.E. New Goodness-of-Fit Tests for the Kumaraswamy Distribution. Stats 2024, 7, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosakhare, U.H.; Bright, A.F. Evaluation of techniques for univariate normality test using Monte Carlo simulation. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2017, 6, 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Borrajo, M.I.; González-Manteiga, W.; Martínez-Miranda, M.D. Goodness-of-Fit Test for Point Processes First-Order Intensity. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2024, 194, 107929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desgagné, A.; Lafaye de Micheaux, P. A Powerful and Interpretable Alternative to the Jarque–Bera Test of Normality Based on 2nd-Power Skewness and Kurtosis, Using the Rao’s Score Test on the APD Family. J. Appl. Stat. 2018, 45, 2307–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terán-García, E.; Pérez-Fernández, R. A robust alternative to the Lilliefors test of normality. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2024, 94, 1494–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, A.; Kendall, M.G. The Advanced Theory of Statistics; Hafner Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, K. Memoir on skew variation in homogeneous material. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 1895, 186, 343–414. [Google Scholar]

- Sulewski, P. Normal distribution with plasticizing component. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 2022, 51, 3806–3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.L. Systems of Frequency Curves Generated by Methods of Translation. Biometrika 1949, 36, 149–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulewski, P. Extended Easily Changeable Kurtosis Distribution. REVSTAT Stat. J. 2023, 23, 463–489. [Google Scholar]

- Sulewski, P. Easily Changeable Kurtosis Distribution. Austrian J. Stat. 2023, 52, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunetta, G. Di una generalizzazione dello schema della curva normale. Ann. Della Fac. Econ. Commer. Palermo 1963, 17, 237–244. [Google Scholar]

- Subbotin, M.T. On the law of frequency of errors. Mat. Sb. 1923, 31, 296–301. [Google Scholar]

| Group | Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | zero | zero | |||

| A | positive | positive | E | positive | negative |

| B | negative | positive | F | negative | negative |

| C | zero | positive | G | positive | zero |

| D | zero | negative | H | negative | zero |

| Alternative | Parameter Ranges | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ES | |||

| P | |||

| NM | |||

| NDPC | |||

| PCM | |||

| LM | |||

| SB | |||

| SU | |||

| EECK | 0 | ||

| EP | 0 |

| Alternative | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ES | 0.9764 | 0.6733 | 0.4744 | 0.2507 |

| P | 0.9712 | 0.6791 | 0.4754 | 0.2524 |

| NM | 0.8874 | 0.3727 | 0.2779 | 0.1701 |

| NDPC | 0.9529 | 0.3845 | 0.2823 | 0.1677 |

| PCM | 0.9607 | 0.3644 | 0.2620 | 0.1546 |

| LM | 0.9005 | 0.3697 | 0.2770 | 0.1698 |

| SB | 0.4162 | 0.1052 | 0.0736 | 0.0432 |

| SU | 0.3953 | 0.0945 | 0.0687 | 0.0428 |

| EECK | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| EP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| No | GoFT | CV | TS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.2010 | 0.1622 | 0.049 | 0.050 | |

| 2 | 0.2417 | 0.1784 | 0.051 | 0.050 | |

| 3 | 0.2316 | 0.1748 | 0.051 | 0.049 | |

| 4 | 0.2419 | 0.1785 | 0.049 | 0.050 | |

| 5 | 0.2026 | 0.163 | 0.049 | 0.050 | |

| 6 | 0.2325 | 0.1746 | 0.051 | 0.050 | |

| 7 | 0.2268 | 0.173 | 0.050 | 0.049 | |

| 8 | 0.2327 | 0.1747 | 0.050 | 0.049 | |

| 9 | 0.2741 | 0.1971 | 0.052 | 0.050 | |

| 10 | 0.3413 | 0.2268 | 0.051 | 0.050 | |

| 11 | 0.3211 | 0.2133 | 0.051 | 0.050 | |

| 12 | 0.2619 | 0.192 | 0.050 | 0.050 | |

| 13 | 0.2769 | 0.1981 | 0.051 | 0.050 | |

| 14 | 0.3313 | 0.2218 | 0.051 | 0.050 | |

| 15 | 0.3141 | 0.211 | 0.051 | 0.050 | |

| 16 | 0.2635 | 0.1925 | 0.050 | 0.050 | |

| 17 | 0.1194 | 0.1232 | 0.050 | 0.050 | |

| 18 | 0.6867 | 0.7227 | 0.050 | 0.050 | |

| 19 | 0.8424 | 0.9034 | 0.050 | 0.051 | |

| 20 | 0.8445 | 0.9044 | 0.050 | 0.051 | |

| ALT | n | 19 | 20 | 18 | 17 | 3 | n | 19 | 20 | 18 | 17 | 3 |

| 10 | 0.285 | 0.254 | 0.248 | 0.234 | 0.220 | 20 | 0.570 | 0.502 | 0.473 | 0.419 | 0.371 | |

| 10 | 0.201 | 0.175 | 0.173 | 0.163 | 0.159 | 20 | 0.396 | 0.333 | 0.311 | 0.275 | 0.248 | |

| 10 | 0.134 | 0.117 | 0.115 | 0.108 | 0.110 | 20 | 0.242 | 0.200 | 0.179 | 0.159 | 0.149 | |

| ALT | n | 20 | 18 | 19 | 17 | 4 | n | 20 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 11 |

| 10 | 0.846 | 0.815 | 0.804 | 0.788 | 0.758 | 20 | 0.997 | 0.993 | 0.993 | 0.986 | 0.976 | |

| 10 | 0.846 | 0.812 | 0.804 | 0.783 | 0.754 | 20 | 0.997 | 0.993 | 0.993 | 0.986 | 0.977 | |

| 10 | 0.845 | 0.814 | 0.805 | 0.785 | 0.757 | 20 | 0.997 | 0.994 | 0.993 | 0.987 | 0.977 | |

| ALT | n | 4 | 8 | 19 | 20 | 18 | n | 4 | 8 | 19 | 20 | 18 |

| 10 | 0.135 | 0.133 | 0.111 | 0.104 | 0.103 | 20 | 0.199 | 0.193 | 0.194 | 0.188 | 0.171 | |

| 10 | 0.136 | 0.133 | 0.105 | 0.102 | 0.100 | 20 | 0.200 | 0.194 | 0.177 | 0.177 | 0.167 | |

| 10 | 0.082 | 0.081 | 0.066 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 20 | 0.098 | 0.094 | 0.085 | 0.081 | 0.079 | |

| ALT | n | 4 | 8 | 17 | 18 | 19 | n | 4 | 8 | 17 | 18 | 3 |

| 10 | 0.387 | 0.384 | 0.340 | 0.339 | 0.334 | 20 | 0.680 | 0.673 | 0.662 | 0.665 | 0.621 | |

| 10 | 0.180 | 0.178 | 0.133 | 0.129 | 0.119 | 20 | 0.299 | 0.292 | 0.244 | 0.227 | 0.222 | |

| 10 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.057 | 0.056 | 0.058 | 20 | 0.069 | 0.069 | 0.062 | 0.059 | 0.064 | |

| ALT | n | 20 | 4 | 8 | 18 | 17 | n | 20 | 18 | 19 | 4 | 17 |

| 10 | 0.594 | 0.549 | 0.550 | 0.589 | 0.578 | 20 | 0.896 | 0.895 | 0.863 | 0.831 | 0.871 | |

| 10 | 0.227 | 0.259 | 0.255 | 0.219 | 0.204 | 20 | 0.493 | 0.479 | 0.465 | 0.458 | 0.434 | |

| 10 | 0.067 | 0.079 | 0.078 | 0.064 | 0.062 | 20 | 0.094 | 0.082 | 0.097 | 0.098 | 0.076 | |

| ALT | n | 19 | 18 | 17 | 20 | 8 | n | 19 | 18 | 20 | 17 | 3 |

| 10 | 0.409 | 0.393 | 0.393 | 0.376 | 0.378 | 20 | 0.704 | 0.691 | 0.659 | 0.689 | 0.638 | |

| 10 | 0.174 | 0.152 | 0.148 | 0.154 | 0.143 | 20 | 0.316 | 0.267 | 0.272 | 0.250 | 0.230 | |

| 10 | 0.100 | 0.092 | 0.090 | 0.094 | 0.079 | 20 | 0.161 | 0.130 | 0.143 | 0.119 | 0.115 | |

| ALT | n | 4 | 8 | 20 | 19 | 18 | n | 4 | 8 | 20 | 19 | 18 |

| 10 | 0.117 | 0.115 | 0.089 | 0.087 | 0.084 | 20 | 0.172 | 0.166 | 0.165 | 0.152 | 0.143 | |

| 10 | 0.107 | 0.105 | 0.079 | 0.079 | 0.076 | 20 | 0.146 | 0.141 | 0.132 | 0.125 | 0.116 | |

| 10 | 0.096 | 0.095 | 0.071 | 0.071 | 0.069 | 20 | 0.127 | 0.122 | 0.112 | 0.108 | 0.100 | |

| ALT | n | 4 | 8 | 19 | 20 | 18 | n | 19 | 20 | 4 | 18 | 8 |

| 10 | 0.150 | 0.147 | 0.137 | 0.129 | 0.124 | 20 | 0.250 | 0.240 | 0.225 | 0.214 | 0.219 | |

| 10 | 0.100 | 0.100 | 0.100 | 0.091 | 0.089 | 20 | 0.165 | 0.146 | 0.135 | 0.131 | 0.132 | |

| 10 | 0.061 | 0.061 | 0.071 | 0.066 | 0.065 | 20 | 0.096 | 0.083 | 0.068 | 0.076 | 0.068 |

| ALT | n | 19 | 20 | 18 | 17 | 11 | n | 19 | 20 | 18 | 17 | 11 |

| 10 | 0.282 | 0.249 | 0.249 | 0.233 | 0.225 | 20 | 0.572 | 0.501 | 0.472 | 0.418 | 0.382 | |

| 10 | 0.202 | 0.177 | 0.174 | 0.163 | 0.163 | 20 | 0.394 | 0.331 | 0.306 | 0.270 | 0.258 | |

| 10 | 0.132 | 0.115 | 0.117 | 0.111 | 0.115 | 20 | 0.240 | 0.198 | 0.181 | 0.162 | 0.164 | |

| ALT | n | 20 | 18 | 19 | 17 | 9 | n | 20 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 9 |

| 10 | 0.846 | 0.815 | 0.804 | 0.787 | 0.780 | 20 | 0.997 | 0.994 | 0.993 | 0.986 | 0.970 | |

| 10 | 0.845 | 0.814 | 0.804 | 0.786 | 0.778 | 20 | 0.997 | 0.993 | 0.993 | 0.986 | 0.971 | |

| 10 | 0.847 | 0.813 | 0.806 | 0.784 | 0.777 | 20 | 0.997 | 0.994 | 0.993 | 0.987 | 0.970 | |

| ALT | n | 15 | 14 | 10 | 11 | 2 | n | 14 | 10 | 15 | 11 | 2 |

| 10 | 0.170 | 0.164 | 0.164 | 0.171 | 0.163 | 20 | 0.261 | 0.261 | 0.266 | 0.269 | 0.253 | |

| 10 | 0.141 | 0.143 | 0.143 | 0.141 | 0.142 | 20 | 0.223 | 0.223 | 0.215 | 0.214 | 0.214 | |

| 10 | 0.102 | 0.107 | 0.107 | 0.101 | 0.106 | 20 | 0.152 | 0.152 | 0.141 | 0.139 | 0.146 | |

| ALT | n | 15 | 11 | 14 | 10 | 2 | n | 19 | 20 | 18 | 11 | 15 |

| 10 | 0.682 | 0.678 | 0.689 | 0.689 | 0.689 | 20 | 0.950 | 0.949 | 0.960 | 0.952 | 0.952 | |

| 10 | 0.401 | 0.403 | 0.390 | 0.390 | 0.389 | 20 | 0.710 | 0.689 | 0.682 | 0.676 | 0.672 | |

| 10 | 0.165 | 0.166 | 0.157 | 0.157 | 0.156 | 20 | 0.302 | 0.282 | 0.247 | 0.260 | 0.257 | |

| ALT | n | 15 | 11 | 14 | 10 | 2 | n | 14 | 10 | 11 | 15 | 2 |

| 10 | 0.269 | 0.270 | 0.258 | 0.258 | 0.257 | 20 | 0.454 | 0.454 | 0.464 | 0.461 | 0.444 | |

| 10 | 0.237 | 0.234 | 0.243 | 0.243 | 0.242 | 20 | 0.431 | 0.431 | 0.416 | 0.418 | 0.421 | |

| 10 | 0.060 | 0.061 | 0.060 | 0.060 | 0.060 | 20 | 0.068 | 0.068 | 0.068 | 0.068 | 0.067 | |

| ALT | n | 19 | 20 | 18 | 17 | 11 | n | 19 | 20 | 18 | 17 | 11 |

| 10 | 0.202 | 0.189 | 0.186 | 0.179 | 0.180 | 20 | 0.377 | 0.340 | 0.338 | 0.312 | 0.293 | |

| 10 | 0.167 | 0.148 | 0.146 | 0.141 | 0.141 | 20 | 0.305 | 0.260 | 0.247 | 0.227 | 0.217 | |

| 10 | 0.162 | 0.140 | 0.144 | 0.142 | 0.131 | 20 | 0.284 | 0.237 | 0.239 | 0.230 | 0.204 | |

| ALT | n | 14 | 10 | 2 | 15 | 6 | n | 14 | 10 | 2 | 20 | 13 |

| 10 | 0.167 | 0.167 | 0.166 | 0.165 | 0.163 | 20 | 0.274 | 0.274 | 0.263 | 0.293 | 0.260 | |

| 10 | 0.111 | 0.111 | 0.110 | 0.108 | 0.108 | 20 | 0.158 | 0.158 | 0.151 | 0.140 | 0.150 | |

| 10 | 0.097 | 0.097 | 0.096 | 0.094 | 0.094 | 20 | 0.130 | 0.130 | 0.123 | 0.104 | 0.123 | |

| ALT | n | 15 | 11 | 14 | 10 | 2 | n | 14 | 10 | 11 | 15 | 2 |

| 10 | 0.130 | 0.130 | 0.130 | 0.130 | 0.129 | 20 | 0.192 | 0.192 | 0.189 | 0.188 | 0.184 | |

| 10 | 0.112 | 0.112 | 0.112 | 0.112 | 0.111 | 20 | 0.156 | 0.156 | 0.152 | 0.152 | 0.149 | |

| 10 | 0.070 | 0.070 | 0.068 | 0.068 | 0.068 | 20 | 0.078 | 0.078 | 0.077 | 0.077 | 0.075 |

| ALT | n | 19 | 20 | 18 | 17 | 3 | n | 19 | 20 | 18 | 17 | 3 |

| 10 | 0.284 | 0.249 | 0.245 | 0.230 | 0.220 | 20 | 0.571 | 0.495 | 0.470 | 0.413 | 0.366 | |

| 10 | 0.201 | 0.174 | 0.173 | 0.161 | 0.159 | 20 | 0.397 | 0.330 | 0.308 | 0.272 | 0.245 | |

| 10 | 0.135 | 0.117 | 0.116 | 0.109 | 0.111 | 20 | 0.240 | 0.196 | 0.179 | 0.159 | 0.149 | |

| ALT | n | 19 | 18 | 20 | 3 | 17 | n | 19 | 20 | 18 | 17 | 3 |

| 10 | 0.137 | 0.124 | 0.121 | 0.119 | 0.119 | 20 | 0.243 | 0.209 | 0.193 | 0.178 | 0.169 | |

| 10 | 0.137 | 0.123 | 0.122 | 0.119 | 0.117 | 20 | 0.242 | 0.210 | 0.190 | 0.174 | 0.166 | |

| 10 | 0.138 | 0.120 | 0.122 | 0.116 | 0.115 | 20 | 0.240 | 0.206 | 0.190 | 0.174 | 0.166 | |

| ALT | n | 3 | 7 | 19 | 17 | 18 | n | 17 | 3 | 7 | 18 | 19 |

| 10 | 0.222 | 0.219 | 0.204 | 0.216 | 0.202 | 20 | 0.391 | 0.387 | 0.380 | 0.357 | 0.325 | |

| 10 | 0.138 | 0.135 | 0.135 | 0.130 | 0.127 | 20 | 0.214 | 0.213 | 0.208 | 0.203 | 0.205 | |

| 10 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.072 | 0.063 | 0.064 | 20 | 0.070 | 0.072 | 0.070 | 0.075 | 0.095 | |

| ALT | n | 3 | 17 | 7 | 18 | 19 | n | 17 | 3 | 18 | 7 | 11 |

| 10 | 0.181 | 0.179 | 0.178 | 0.169 | 0.166 | 20 | 0.318 | 0.302 | 0.292 | 0.295 | 0.279 | |

| 10 | 0.059 | 0.059 | 0.059 | 0.060 | 0.064 | 20 | 0.063 | 0.064 | 0.065 | 0.064 | 0.062 | |

| 10 | 0.052 | 0.053 | 0.052 | 0.054 | 0.052 | 20 | 0.052 | 0.051 | 0.054 | 0.051 | 0.050 | |

| ALT | n | 3 | 7 | 19 | 11 | 17 | n | 3 | 7 | 11 | 17 | 15 |

| 10 | 0.085 | 0.083 | 0.093 | 0.082 | 0.082 | 20 | 0.108 | 0.105 | 0.104 | 0.109 | 0.101 | |

| 10 | 0.119 | 0.117 | 0.103 | 0.107 | 0.108 | 20 | 0.175 | 0.172 | 0.161 | 0.159 | 0.158 | |

| 10 | 0.084 | 0.082 | 0.079 | 0.079 | 0.077 | 20 | 0.106 | 0.104 | 0.102 | 0.097 | 0.099 | |

| ALT | n | 19 | 18 | 3 | 17 | 7 | n | 19 | 18 | 20 | 17 | 3 |

| 10 | 0.177 | 0.159 | 0.159 | 0.157 | 0.156 | 20 | 0.312 | 0.271 | 0.260 | 0.265 | 0.253 | |

| 10 | 0.170 | 0.152 | 0.151 | 0.150 | 0.148 | 20 | 0.300 | 0.257 | 0.251 | 0.249 | 0.238 | |

| 10 | 0.164 | 0.146 | 0.145 | 0.142 | 0.141 | 20 | 0.290 | 0.242 | 0.240 | 0.232 | 0.221 | |

| ALT | n | 19 | 20 | 18 | 3 | 7 | n | 19 | 20 | 18 | 17 | 3 |

| 10 | 0.104 | 0.093 | 0.091 | 0.090 | 0.088 | 20 | 0.169 | 0.144 | 0.131 | 0.120 | 0.115 | |

| 10 | 0.106 | 0.094 | 0.092 | 0.091 | 0.089 | 20 | 0.169 | 0.143 | 0.130 | 0.120 | 0.116 | |

| 10 | 0.063 | 0.059 | 0.058 | 0.059 | 0.059 | 20 | 0.079 | 0.071 | 0.065 | 0.063 | 0.063 | |

| ALT | n | 19 | 3 | 7 | 18 | 17 | n | 19 | 18 | 20 | 17 | 3 |

| 10 | 0.155 | 0.140 | 0.137 | 0.137 | 0.135 | 20 | 0.263 | 0.223 | 0.217 | 0.217 | 0.210 | |

| 10 | 0.091 | 0.084 | 0.082 | 0.082 | 0.080 | 20 | 0.134 | 0.107 | 0.111 | 0.103 | 0.104 | |

| 10 | 0.096 | 0.088 | 0.086 | 0.085 | 0.084 | 20 | 0.141 | 0.116 | 0.116 | 0.113 | 0.115 | |

| ALT | n | 19 | 3 | 7 | 18 | 11 | n | 19 | 20 | 3 | 18 | 7 |

| 10 | 0.072 | 0.067 | 0.066 | 0.065 | 0.065 | 20 | 0.093 | 0.079 | 0.076 | 0.076 | 0.074 | |

| 10 | 0.066 | 0.063 | 0.062 | 0.060 | 0.060 | 20 | 0.079 | 0.069 | 0.067 | 0.066 | 0.066 | |

| 10 | 0.060 | 0.057 | 0.056 | 0.057 | 0.057 | 20 | 0.069 | 0.062 | 0.060 | 0.059 | 0.059 |

| ALT | n | 20 | 18 | 17 | 19 | 1 | n | 20 | 18 | 19 | 17 | 1 |

| 10 | 0.667 | 0.601 | 0.528 | 0.481 | 0.481 | 20 | 0.981 | 0.949 | 0.917 | 0.888 | 0.802 | |

| 10 | 0.666 | 0.598 | 0.524 | 0.483 | 0.480 | 20 | 0.981 | 0.949 | 0.919 | 0.888 | 0.801 | |

| 10 | 0.664 | 0.597 | 0.523 | 0.483 | 0.477 | 20 | 0.980 | 0.951 | 0.918 | 0.890 | 0.804 | |

| ALT | n | 9 | 1 | 13 | 5 | 20 | n | 18 | 9 | 20 | 13 | 1 |

| 10 | 0.199 | 0.208 | 0.189 | 0.199 | 0.184 | 20 | 0.471 | 0.416 | 0.413 | 0.402 | 0.426 | |

| 10 | 0.237 | 0.218 | 0.218 | 0.206 | 0.213 | 20 | 0.432 | 0.470 | 0.479 | 0.448 | 0.413 | |

| 10 | 0.055 | 0.058 | 0.053 | 0.056 | 0.047 | 20 | 0.060 | 0.064 | 0.054 | 0.062 | 0.071 | |

| ALT | n | 1 | 9 | 5 | 13 | 17 | n | 1 | 17 | 5 | 9 | 18 |

| 10 | 0.126 | 0.119 | 0.120 | 0.114 | 0.111 | 20 | 0.227 | 0.237 | 0.219 | 0.212 | 0.231 | |

| 10 | 0.063 | 0.064 | 0.062 | 0.062 | 0.052 | 20 | 0.084 | 0.070 | 0.081 | 0.082 | 0.066 | |

| 10 | 0.049 | 0.049 | 0.049 | 0.050 | 0.047 | 20 | 0.049 | 0.046 | 0.048 | 0.049 | 0.045 | |

| ALT | n | 9 | 1 | 13 | 5 | 2 | n | 1 | 9 | 5 | 13 | 4 |

| 10 | 0.049 | 0.049 | 0.049 | 0.048 | 0.048 | 20 | 0.050 | 0.049 | 0.049 | 0.049 | 0.049 | |

| 10 | 0.061 | 0.061 | 0.059 | 0.060 | 0.054 | 20 | 0.077 | 0.076 | 0.075 | 0.074 | 0.066 | |

| 10 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.049 | 0.048 | 20 | 0.053 | 0.052 | 0.052 | 0.051 | 0.049 | |

| ALT | n | 1 | 18 | 5 | 17 | 20 | n | 18 | 17 | 1 | 5 | 20 |

| 10 | 0.215 | 0.197 | 0.208 | 0.201 | 0.177 | 20 | 0.422 | 0.432 | 0.412 | 0.401 | 0.341 | |

| 10 | 0.270 | 0.270 | 0.260 | 0.260 | 0.250 | 20 | 0.572 | 0.539 | 0.514 | 0.502 | 0.507 | |

| 10 | 0.213 | 0.224 | 0.205 | 0.206 | 0.212 | 20 | 0.458 | 0.396 | 0.384 | 0.374 | 0.424 | |

| ALT | n | 1 | 9 | 5 | 13 | 4 | n | 9 | 13 | 1 | 5 | 14 |

| 10 | 0.049 | 0.049 | 0.048 | 0.049 | 0.048 | 20 | 0.048 | 0.048 | 0.048 | 0.047 | 0.047 | |

| 10 | 0.049 | 0.049 | 0.049 | 0.049 | 0.049 | 20 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.050 | 0.049 | 0.050 | |

| 10 | 0.051 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.049 | 0.049 | 20 | 0.048 | 0.048 | 0.048 | 0.048 | 0.047 | |

| ALT | n | 9 | 1 | 13 | 5 | 14 | n | 9 | 1 | 13 | 5 | 18 |

| 10 | 0.065 | 0.063 | 0.062 | 0.060 | 0.052 | 20 | 0.086 | 0.085 | 0.082 | 0.080 | 0.078 | |

| 10 | 0.053 | 0.052 | 0.052 | 0.051 | 0.048 | 20 | 0.057 | 0.055 | 0.055 | 0.053 | 0.046 | |

| 10 | 0.050 | 0.049 | 0.050 | 0.049 | 0.047 | 20 | 0.051 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.049 | 0.044 | |

| ALT | n | 9 | 1 | 13 | 5 | 18 | n | 20 | 18 | 9 | 1 | 13 |

| 10 | 0.083 | 0.081 | 0.078 | 0.077 | 0.074 | 20 | 0.188 | 0.163 | 0.130 | 0.129 | 0.124 | |

| 10 | 0.059 | 0.058 | 0.057 | 0.056 | 0.047 | 20 | 0.056 | 0.061 | 0.072 | 0.070 | 0.069 | |

| 10 | 0.055 | 0.054 | 0.053 | 0.053 | 0.045 | 20 | 0.045 | 0.050 | 0.061 | 0.060 | 0.059 |

| ALT | n | 20 | 18 | 17 | 4 | 19 | n | 20 | 18 | 19 | 17 | 4 |

| 10 | 0.775 | 0.740 | 0.701 | 0.684 | 0.685 | 20 | 0.990 | 0.979 | 0.970 | 0.961 | 0.936 | |

| 10 | 0.778 | 0.741 | 0.703 | 0.687 | 0.685 | 20 | 0.991 | 0.979 | 0.970 | 0.960 | 0.935 | |

| 10 | 0.776 | 0.741 | 0.704 | 0.688 | 0.686 | 20 | 0.991 | 0.980 | 0.970 | 0.962 | 0.937 | |

| ALT | n | 4 | 8 | 18 | 17 | 20 | n | 4 | 8 | 18 | 17 | 20 |

| 10 | 0.137 | 0.135 | 0.093 | 0.092 | 0.089 | 20 | 0.212 | 0.205 | 0.166 | 0.163 | 0.157 | |

| 10 | 0.093 | 0.091 | 0.064 | 0.065 | 0.063 | 20 | 0.122 | 0.117 | 0.087 | 0.087 | 0.086 | |

| 10 | 0.065 | 0.064 | 0.053 | 0.053 | 0.051 | 20 | 0.071 | 0.070 | 0.057 | 0.056 | 0.052 | |

| ALT | n | 4 | 8 | 17 | 18 | 1 | n | 4 | 8 | 17 | 18 | 1 |

| 10 | 0.693 | 0.689 | 0.659 | 0.645 | 0.628 | 20 | 0.963 | 0.962 | 0.974 | 0.969 | 0.951 | |

| 10 | 0.107 | 0.105 | 0.072 | 0.073 | 0.077 | 20 | 0.165 | 0.159 | 0.127 | 0.127 | 0.124 | |

| 10 | 0.081 | 0.079 | 0.058 | 0.056 | 0.062 | 20 | 0.102 | 0.099 | 0.075 | 0.073 | 0.077 | |

| ALT | n | 4 | 8 | 1 | 5 | 18 | n | 4 | 8 | 1 | 18 | 5 |

| 10 | 0.153 | 0.151 | 0.130 | 0.125 | 0.116 | 20 | 0.278 | 0.270 | 0.244 | 0.244 | 0.236 | |

| 10 | 0.087 | 0.086 | 0.076 | 0.074 | 0.066 | 20 | 0.135 | 0.131 | 0.120 | 0.109 | 0.117 | |

| 10 | 0.073 | 0.071 | 0.056 | 0.055 | 0.051 | 20 | 0.090 | 0.087 | 0.067 | 0.069 | 0.065 | |

| ALT | n | 1 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 18 | n | 1 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 18 |

| 10 | 0.864 | 0.874 | 0.873 | 0.859 | 0.873 | 20 | 0.997 | 0.997 | 0.997 | 0.997 | 0.998 | |

| 10 | 0.434 | 0.411 | 0.409 | 0.417 | 0.395 | 20 | 0.741 | 0.732 | 0.728 | 0.728 | 0.739 | |

| 10 | 0.125 | 0.129 | 0.128 | 0.122 | 0.109 | 20 | 0.211 | 0.215 | 0.213 | 0.206 | 0.191 | |

| ALT | n | 20 | 4 | 8 | 18 | 17 | n | 20 | 18 | 19 | 17 | 4 |

| 10 | 0.495 | 0.442 | 0.437 | 0.458 | 0.427 | 20 | 0.892 | 0.844 | 0.799 | 0.791 | 0.746 | |

| 10 | 0.213 | 0.232 | 0.229 | 0.197 | 0.186 | 20 | 0.502 | 0.441 | 0.401 | 0.394 | 0.410 | |

| 10 | 0.048 | 0.063 | 0.062 | 0.048 | 0.048 | 20 | 0.049 | 0.051 | 0.042 | 0.051 | 0.069 | |

| ALT | n | 4 | 8 | 1 | 5 | 12 | n | 4 | 19 | 8 | 20 | 18 |

| 10 | 0.052 | 0.052 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.049 | 20 | 0.052 | 0.052 | 0.052 | 0.051 | 0.050 | |

| 10 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 20 | 0.049 | 0.050 | 0.049 | 0.050 | 0.050 | |

| 10 | 0.050 | 0.051 | 0.052 | 0.052 | 0.051 | 20 | 0.049 | 0.049 | 0.049 | 0.049 | 0.048 |

| ALT | n | 20 | 18 | 9 | 13 | 17 | n | 20 | 18 | 19 | 17 | 9 |

| 10 | 0.778 | 0.738 | 0.735 | 0.726 | 0.701 | 20 | 0.990 | 0.980 | 0.969 | 0.961 | 0.953 | |

| 10 | 0.777 | 0.741 | 0.736 | 0.727 | 0.703 | 20 | 0.990 | 0.980 | 0.970 | 0.962 | 0.954 | |

| 10 | 0.778 | 0.739 | 0.735 | 0.726 | 0.701 | 20 | 0.990 | 0.979 | 0.969 | 0.961 | 0.954 | |

| ALT | n | 9 | 13 | 14 | 10 | 2 | n | 9 | 13 | 14 | 10 | 2 |

| 10 | 0.322 | 0.321 | 0.312 | 0.312 | 0.310 | 20 | 0.597 | 0.595 | 0.589 | 0.589 | 0.577 | |

| 10 | 0.105 | 0.101 | 0.089 | 0.089 | 0.089 | 20 | 0.152 | 0.147 | 0.132 | 0.132 | 0.127 | |

| 10 | 0.056 | 0.056 | 0.057 | 0.057 | 0.057 | 20 | 0.058 | 0.058 | 0.060 | 0.060 | 0.059 | |

| ALT | n | 13 | 9 | 14 | 10 | 2 | n | 9 | 14 | 10 | 13 | 2 |

| 10 | 0.295 | 0.295 | 0.289 | 0.289 | 0.287 | 20 | 0.550 | 0.549 | 0.549 | 0.549 | 0.536 | |

| 10 | 0.101 | 0.102 | 0.099 | 0.099 | 0.098 | 20 | 0.145 | 0.144 | 0.144 | 0.144 | 0.137 | |

| 10 | 0.054 | 0.054 | 0.053 | 0.053 | 0.053 | 20 | 0.055 | 0.056 | 0.055 | 0.056 | 0.054 | |

| ALT | n | 9 | 13 | 14 | 10 | 2 | n | 20 | 18 | 9 | 13 | 17 |

| 10 | 0.143 | 0.141 | 0.130 | 0.130 | 0.130 | 20 | 0.340 | 0.318 | 0.253 | 0.249 | 0.269 | |

| 10 | 0.067 | 0.064 | 0.058 | 0.058 | 0.058 | 20 | 0.063 | 0.067 | 0.084 | 0.080 | 0.066 | |

| 10 | 0.051 | 0.050 | 0.048 | 0.048 | 0.048 | 20 | 0.041 | 0.044 | 0.052 | 0.051 | 0.045 | |

| ALT | n | 9 | 13 | 18 | 17 | 6 | n | 18 | 17 | 9 | 13 | 1 |

| 10 | 0.276 | 0.277 | 0.299 | 0.287 | 0.275 | 20 | 0.624 | 0.589 | 0.520 | 0.519 | 0.529 | |

| 10 | 0.234 | 0.236 | 0.225 | 0.224 | 0.237 | 20 | 0.475 | 0.464 | 0.429 | 0.430 | 0.397 | |

| 10 | 0.131 | 0.127 | 0.112 | 0.115 | 0.111 | 20 | 0.204 | 0.216 | 0.226 | 0.220 | 0.229 | |

| ALT | n | 9 | 13 | 14 | 10 | 2 | n | 20 | 9 | 13 | 14 | 10 |

| 10 | 0.524 | 0.518 | 0.488 | 0.488 | 0.485 | 20 | 0.916 | 0.814 | 0.808 | 0.792 | 0.792 | |

| 10 | 0.129 | 0.129 | 0.126 | 0.126 | 0.125 | 20 | 0.181 | 0.200 | 0.200 | 0.202 | 0.202 | |

| 10 | 0.106 | 0.106 | 0.106 | 0.106 | 0.105 | 20 | 0.123 | 0.149 | 0.149 | 0.153 | 0.153 | |

| ALT | n | 11 | 15 | 14 | 10 | 2 | n | 11 | 14 | 10 | 15 | 19 |

| 10 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 20 | 0.051 | 0.052 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.051 | |

| 10 | 0.067 | 0.066 | 0.065 | 0.065 | 0.065 | 20 | 0.078 | 0.077 | 0.077 | 0.076 | 0.078 | |

| 10 | 0.052 | 0.052 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 20 | 0.054 | 0.054 | 0.054 | 0.054 | 0.050 |

| ALT | n | 20 | 18 | 17 | 19 | 4 | n | 20 | 18 | 19 | 17 | 4 |

| 10 | 0.801 | 0.767 | 0.733 | 0.727 | 0.715 | 20 | 0.992 | 0.985 | 0.978 | 0.971 | 0.950 | |

| 10 | 0.800 | 0.765 | 0.732 | 0.727 | 0.716 | 20 | 0.992 | 0.985 | 0.978 | 0.971 | 0.949 | |

| 10 | 0.801 | 0.766 | 0.733 | 0.726 | 0.715 | 20 | 0.993 | 0.984 | 0.978 | 0.970 | 0.950 | |

| ALT | n | 4 | 8 | 18 | 17 | 20 | n | 4 | 8 | 20 | 18 | 19 |

| 10 | 0.095 | 0.094 | 0.066 | 0.065 | 0.066 | 20 | 0.124 | 0.119 | 0.094 | 0.091 | 0.087 | |

| 10 | 0.063 | 0.062 | 0.052 | 0.052 | 0.051 | 20 | 0.067 | 0.066 | 0.056 | 0.054 | 0.056 | |

| 10 | 0.057 | 0.057 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.050 | 20 | 0.061 | 0.060 | 0.052 | 0.051 | 0.052 | |

| ALT | n | 4 | 8 | 1 | 5 | 18 | n | 4 | 8 | 18 | 20 | 1 |

| 10 | 0.174 | 0.172 | 0.128 | 0.127 | 0.122 | 20 | 0.304 | 0.296 | 0.238 | 0.244 | 0.237 | |

| 10 | 0.095 | 0.095 | 0.104 | 0.101 | 0.094 | 20 | 0.155 | 0.155 | 0.168 | 0.164 | 0.170 | |

| 10 | 0.095 | 0.094 | 0.065 | 0.065 | 0.068 | 20 | 0.131 | 0.126 | 0.094 | 0.088 | 0.087 | |

| ALT | n | 4 | 8 | 1 | 5 | 18 | n | 4 | 8 | 18 | 17 | 1 |

| 10 | 0.273 | 0.270 | 0.208 | 0.207 | 0.206 | 20 | 0.514 | 0.504 | 0.407 | 0.403 | 0.405 | |

| 10 | 0.137 | 0.137 | 0.139 | 0.135 | 0.130 | 20 | 0.241 | 0.239 | 0.258 | 0.250 | 0.244 | |

| 10 | 0.086 | 0.084 | 0.061 | 0.061 | 0.063 | 20 | 0.105 | 0.101 | 0.080 | 0.074 | 0.072 | |

| ALT | n | 4 | 8 | 17 | 18 | 1 | n | 17 | 4 | 8 | 18 | 1 |

| 10 | 0.573 | 0.569 | 0.518 | 0.512 | 0.517 | 20 | 0.870 | 0.881 | 0.877 | 0.868 | 0.859 | |

| 10 | 0.513 | 0.509 | 0.456 | 0.448 | 0.422 | 20 | 0.834 | 0.835 | 0.830 | 0.820 | 0.778 | |

| 10 | 0.089 | 0.090 | 0.102 | 0.100 | 0.117 | 20 | 0.172 | 0.143 | 0.147 | 0.165 | 0.186 | |

| ALT | n | 4 | 8 | 20 | 18 | 17 | n | 4 | 8 | 20 | 18 | 19 |

| 10 | 0.090 | 0.089 | 0.064 | 0.062 | 0.061 | 20 | 0.117 | 0.113 | 0.096 | 0.087 | 0.087 | |

| 10 | 0.083 | 0.081 | 0.059 | 0.059 | 0.058 | 20 | 0.103 | 0.099 | 0.084 | 0.077 | 0.077 | |

| 10 | 0.068 | 0.067 | 0.053 | 0.053 | 0.053 | 20 | 0.077 | 0.074 | 0.061 | 0.058 | 0.059 | |

| ALT | n | 4 | 8 | 19 | 17 | 5 | n | 4 | 8 | 19 | 20 | 18 |

| 10 | 0.064 | 0.063 | 0.054 | 0.053 | 0.053 | 20 | 0.071 | 0.069 | 0.060 | 0.060 | 0.057 | |

| 10 | 0.059 | 0.059 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 20 | 0.066 | 0.064 | 0.054 | 0.055 | 0.053 | |

| 10 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 20 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.049 | 0.049 |

| ALT | n | 20 | 18 | 9 | 13 | 17 | n | 20 | 18 | 19 | 17 | 9 |

| 10 | 0.801 | 0.764 | 0.757 | 0.750 | 0.732 | 20 | 0.992 | 0.984 | 0.978 | 0.971 | 0.963 | |

| 10 | 0.801 | 0.766 | 0.759 | 0.752 | 0.731 | 20 | 0.993 | 0.984 | 0.979 | 0.970 | 0.962 | |

| 10 | 0.800 | 0.767 | 0.757 | 0.751 | 0.735 | 20 | 0.993 | 0.985 | 0.979 | 0.971 | 0.962 | |

| ALT | n | 14 | 10 | 2 | 13 | 6 | n | 14 | 10 | 2 | 13 | 9 |

| 10 | 0.118 | 0.118 | 0.117 | 0.115 | 0.114 | 20 | 0.175 | 0.175 | 0.167 | 0.168 | 0.168 | |

| 10 | 0.098 | 0.098 | 0.097 | 0.095 | 0.095 | 20 | 0.131 | 0.131 | 0.125 | 0.123 | 0.123 | |

| 10 | 0.058 | 0.058 | 0.058 | 0.058 | 0.058 | 20 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.061 | 0.060 | 0.060 | |

| ALT | n | 14 | 10 | 2 | 13 | 15 | n | 14 | 10 | 2 | 13 | 15 |

| 10 | 0.165 | 0.165 | 0.164 | 0.157 | 0.163 | 20 | 0.280 | 0.280 | 0.269 | 0.264 | 0.269 | |

| 10 | 0.095 | 0.095 | 0.094 | 0.096 | 0.092 | 20 | 0.131 | 0.131 | 0.124 | 0.126 | 0.122 | |

| 10 | 0.055 | 0.055 | 0.055 | 0.057 | 0.054 | 20 | 0.060 | 0.060 | 0.058 | 0.059 | 0.057 | |

| ALT | n | 14 | 10 | 2 | 13 | 9 | n | 14 | 10 | 2 | 13 | 9 |

| 10 | 0.080 | 0.080 | 0.079 | 0.078 | 0.078 | 20 | 0.101 | 0.101 | 0.097 | 0.096 | 0.095 | |

| 10 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 20 | 0.071 | 0.071 | 0.069 | 0.069 | 0.069 | |

| 10 | 0.074 | 0.074 | 0.074 | 0.074 | 0.074 | 20 | 0.092 | 0.092 | 0.088 | 0.088 | 0.088 | |

| ALT | n | 18 | 17 | 20 | 13 | 6 | n | 18 | 17 | 20 | 9 | 13 |

| 10 | 0.387 | 0.361 | 0.373 | 0.348 | 0.366 | 20 | 0.744 | 0.693 | 0.707 | 0.632 | 0.638 | |

| 10 | 0.128 | 0.132 | 0.117 | 0.166 | 0.159 | 20 | 0.239 | 0.252 | 0.193 | 0.278 | 0.277 | |

| 10 | 0.133 | 0.135 | 0.122 | 0.092 | 0.080 | 20 | 0.256 | 0.260 | 0.206 | 0.188 | 0.181 | |

| ALT | n | 14 | 10 | 2 | 13 | 9 | n | 14 | 10 | 9 | 13 | 2 |

| 10 | 0.110 | 0.110 | 0.109 | 0.110 | 0.110 | 20 | 0.165 | 0.165 | 0.160 | 0.160 | 0.157 | |

| 10 | 0.079 | 0.079 | 0.078 | 0.077 | 0.077 | 20 | 0.099 | 0.099 | 0.094 | 0.095 | 0.094 | |

| 10 | 0.079 | 0.079 | 0.078 | 0.077 | 0.076 | 20 | 0.099 | 0.099 | 0.095 | 0.094 | 0.094 | |

| ALT | n | 11 | 14 | 10 | 2 | 15 | n | 14 | 10 | 11 | 15 | 2 |

| 10 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 20 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.050 | |

| 10 | 0.060 | 0.060 | 0.060 | 0.060 | 0.060 | 20 | 0.068 | 0.067 | 0.066 | 0.066 | 0.066 | |

| 10 | 0.058 | 0.058 | 0.058 | 0.058 | 0.058 | 20 | 0.062 | 0.062 | 0.061 | 0.061 | 0.060 |

| Ex | Description | R Source | n | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Socio-economic data (percentage of draftees receiving the highest mark on the army examination) for 47 French-speaking provinces of Switzerland. | swiss [3] | 47 | ||

| II | The data give the distances taken to stop. | cars [2] | 50 | 0.782 | 0.248 |

| III | Socio-economic data (draftees receiving highest mark on army examination) for 47 French-speaking provinces of Switzerland. | Swiss [3] | 47 | 0.461 | −0011 |

| IV | Measurements of the height of timber in 31 felled black cherry trees. | trees [2] | 31 | −0.375 | −0.569 |

| V | Displacement of 32 cars (1973–74 models). | mtcars [3] | 32 | 0.400 | −1.090 |

| VI | Gross horsepower of 32 cars (1973–74 models). | mtcars [4] | 32 | 0.761 | 0.052 |

| VII | Rear axle ratio of 32 cars (1973–74 models). | mtcars [5] | 32 | 0.279 | −0.565 |

| VIII | The data includes the weight (1000 lbs) of 32 cars (1973–74 models). | mtcars [6] | 32 | 0.444 | 0.172 |

| IX | Lawyers’ ratings of state judges in the US Superior Court (Preparation for trial). | US Judge Ratings [7] | 43 | −0.681 | 0.141 |

| X | Lawyers’ ratings of state judges in the US Superior Court (Judicial integrity). | US Judge Ratings [2] | 43 | −0.843 | 0.414 |

| XI | Lawyers’ ratings of state judges in the US Superior Court (Demeanor). | US Judge Ratings [3] | 43 | −0.948 | 0432 |

| XII | Daily air quality measurements in New York (wind in mph). | air quality [3] | 153 | 0.344 | 0.069 |

| XIII | Statistics in arrests per 100,000 residents for the percent urban population in each of the 50 US states. | US Arrests [3] | 50 | −0.219 | −0.784 |

| XIV | A regular time series giving the luteinizing hormone in blood samples at 10 min intervals from a human female, 48 samples. | l h | 48 | 0.284 | −0.746 |

| XV | Statistics in arrests per 100,000 residents for assault in each of the 50 US states. | US Arrests [2] | 50 | 0.227 | −1.069 |

| XVI | From a survey of the clerical employees of a large financial organization, the data are aggregated from the questionnaires of the approximately 35 employees for each of 30 (randomly selected) departments. The numbers give the percentage proportion of favorable responses to questions in each department (variable: “does not allow special privileges”). | attitude [2] | 30 | −0.227 | −0.514 |

| XVII | As in example XVI (variable “Too critical”). | attitude [5] | 30 | 0.208 | −0.431 |

| XVIII | A set of macroeconomic data that provides information on the number of unemployed. | longley [3] | 16 | 0.158 | −1.065 |

| XIX | A set of macroeconomic data that provides information on the number of people in the armed forces. | longley [4] | 16 | −0.404 | −0.949 |

| XX | A set of macroeconomic data that provides information on the number of people employed. | longley [7] | 16 | −0.094 | −1.351 |

| XXI | Daily air quality measurements in New York (temperature in degrees F). | air quality [4] | 153 | −0.374 | −0.429 |

| XXII | Measurements on 48 rock samples from a petroleum reservoir (area of pore space, in pixels out of 256 by 256). | rock [1] | 48 | −0.304 | −0.262 |

| XXIII | As in example XVI (variable: “handling of employee complaints”). | attitude [1] | 30 | −0.377 | −0.609 |

| XXIV | A set of macroeconomic data that provides information on the number of unemployed. | longley [3] | 16 | 0.158 | −1.065 |

| XXV | The data give the distances taken to stop. | cars [2] | 50 | 0.782 | 0.248 |

| XXVI | Measurements in centimeters of the sepal length for 50 flowers from each of 3 species of iris. The species are Iris setosa, versicolor, and virginica. | iris [1] | 150 | 0.312 | −0.574 |

| XXVII | An experiment to compare yields (as measured by dried weight of plants). | Plant Growth [1] | 30 | −0.153 | −0.659 |

| XXVIII | The data consists of five experiments, each consisting of 20 consecutive ’runs’. The response is the speed of light measurement, suitably coded (km/sec, with 299,000 subtracted). | morley [3] | 100 | −0.018 | 0.263 |

| XXIX | The mean annual temperature in degrees Fahrenheit in New Haven, Connecticut. | nhtemp | 60 | −0.074 | 0.499 |

| XXX | A classical N, P, K (nitrogen, phosphate, potassium) factorial experiment on the growth of peas in pounds/plot (the plots were (1/70) acre). | npk [5] | 24 | 0.261 | −0.290 |

| GoFT | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | X |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.29 | 0.039 | 0.298 | 0.216 | 0.002 | 0.020 | 0.024 | 0.212 | 0.217 | 0.036 | |

| 0.507 | 0.102 | 0.517 | 0.172 | 0.016 | 0.084 | 0.115 | 0.336 | 0.148 | 0.019 | |

| 0.29 | 0.049 | 0.294 | 0.364 | 0.005 | 0.030 | 0.055 | 0.091 | 0.254 | 0.032 | |

| 0.194 | 0.025 | 0.193 | 0.574 | 0.002 | 0.013 | 0.020 | 0.082 | 0.444 | 0.089 | |

| 0.287 | 0.039 | 0.296 | 0.226 | 0.002 | 0.020 | 0.026 | 0.194 | 0.219 | 0.035 | |

| 0.457 | 0.084 | 0.459 | 0.182 | 0.011 | 0.064 | 0.089 | 0.278 | 0.157 | 0.020 | |

| 0.286 | 0.047 | 0.292 | 0.344 | 0.004 | 0.028 | 0.050 | 0.098 | 0.248 | 0.032 | |

| 0.204 | 0.027 | 0.205 | 0.495 | 0.002 | 0.014 | 0.021 | 0.087 | 0.387 | 0.072 | |

| 0.533 | 0.095 | 0.531 | 0.132 | 0.012 | 0.073 | 0.084 | 0.472 | 0.139 | 0.020 | |

| 0.515 | 0.269 | 0.520 | 0.150 | 0.084 | 0.299 | 0.337 | 0.378 | 0.126 | 0.017 | |

| 0.493 | 0.116 | 0.496 | 0.238 | 0.022 | 0.102 | 0.165 | 0.248 | 0.166 | 0.018 | |

| 0.278 | 0.042 | 0.290 | 0.274 | 0.003 | 0.023 | 0.035 | 0.137 | 0.230 | 0.033 | |

| 0.527 | 0.096 | 0.526 | 0.139 | 0.012 | 0.075 | 0.089 | 0.440 | 0.140 | 0.020 | |

| 0.527 | 0.223 | 0.528 | 0.152 | 0.061 | 0.235 | 0.306 | 0.383 | 0.128 | 0.017 | |

| 0.503 | 0.113 | 0.512 | 0.223 | 0.021 | 0.098 | 0.152 | 0.263 | 0.161 | 0.018 | |

| 0.306 | 0.049 | 0.323 | 0.240 | 0.004 | 0.029 | 0.044 | 0.162 | 0.205 | 0.028 | |

| 0.37 | 0.049 | 0.354 | 0.438 | 0.023 | 0.054 | 0.050 | 0.166 | 0.274 | 0.072 | |

| 0.379 | 0.051 | 0.364 | 0.439 | 0.022 | 0.059 | 0.054 | 0.106 | 0.233 | 0.048 | |

| 0.291 | 0.044 | 0.284 | 0.520 | 0.052 | 0.057 | 0.124 | 0.106 | 0.157 | 0.029 | |

| 0.265 | 0.039 | 0.257 | 0.405 | 0.021 | 0.050 | 0.109 | 0.093 | 0.171 | 0.022 |

| GoFT | XI | XII | XIII | XIV | XV | XVI | XVII | XVIII | XIX | XX |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.009 | 0.016 | 0.442 | 0.220 | 0.028 | 0.484 | 0.449 | 0.525 | 0.128 | 0.411 | |

| 0.005 | 0.022 | 0.411 | 0.397 | 0.089 | 0.398 | 0.728 | 0.819 | 0.050 | 0.338 | |

| 0.009 | 0.011 | 0.694 | 0.205 | 0.050 | 0.691 | 0.363 | 0.888 | 0.077 | 0.723 | |

| 0.030 | 0.009 | 0.804 | 0.135 | 0.022 | 0.784 | 0.256 | 0.471 | 0.159 | 0.439 | |

| 0.009 | 0.015 | 0.463 | 0.217 | 0.029 | 0.499 | 0.435 | 0.553 | 0.119 | 0.431 | |

| 0.005 | 0.020 | 0.431 | 0.347 | 0.073 | 0.420 | 0.648 | 0.836 | 0.053 | 0.355 | |

| 0.009 | 0.012 | 0.665 | 0.204 | 0.047 | 0.666 | 0.367 | 0.847 | 0.079 | 0.679 | |

| 0.023 | 0.010 | 0.751 | 0.144 | 0.023 | 0.805 | 0.271 | 0.492 | 0.168 | 0.459 | |

| 0.005 | 0.027 | 0.314 | 0.416 | 0.071 | 0.326 | 0.702 | 0.793 | 0.069 | 0.249 | |

| 0.004 | 0.042 | 0.351 | 0.632 | 0.089 | 0.352 | 0.781 | 0.794 | 0.048 | 0.314 | |

| 0.005 | 0.019 | 0.541 | 0.395 | 0.118 | 0.515 | 0.710 | 0.780 | 0.042 | 0.531 | |

| 0.009 | 0.013 | 0.557 | 0.208 | 0.037 | 0.573 | 0.393 | 0.690 | 0.094 | 0.536 | |

| 0.005 | 0.026 | 0.331 | 0.411 | 0.074 | 0.338 | 0.726 | 0.791 | 0.065 | 0.262 | |

| 0.004 | 0.037 | 0.358 | 0.640 | 0.091 | 0.356 | 0.786 | 0.795 | 0.048 | 0.315 | |

| 0.005 | 0.020 | 0.512 | 0.394 | 0.111 | 0.487 | 0.709 | 0.823 | 0.043 | 0.478 | |

| 0.007 | 0.015 | 0.518 | 0.234 | 0.043 | 0.523 | 0.444 | 0.767 | 0.075 | 0.470 | |

| 0.022 | 0.052 | 0.590 | 0.316 | 0.064 | 0.588 | 0.645 | 0.712 | 0.136 | 0.485 | |

| 0.015 | 0.054 | 0.544 | 0.351 | 0.053 | 0.569 | 0.738 | 0.665 | 0.107 | 0.398 | |

| 0.011 | 0.111 | 0.595 | 0.447 | 0.102 | 0.589 | 0.848 | 0.677 | 0.175 | 0.452 | |

| 0.006 | 0.117 | 0.439 | 0.271 | 0.040 | 0.554 | 0.897 | 0.481 | 0.112 | 0.260 |

| GoFT | XI | XII | XIII | XIV | XV | XVI | XVII | XVIII | XIX | XX |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.017 | 0.484 | 0.116 | 0.522 | 0.038 | 0.005 | 0.738 | 0.100 | 0.398 | 0.824 | |

| 0.011 | 0.340 | 0.056 | 0.818 | 0.102 | 0.011 | 0.535 | 0.145 | 0.332 | 0.694 | |

| 0.015 | 0.481 | 0.085 | 0.888 | 0.048 | 0.008 | 0.727 | 0.074 | 0.244 | 0.868 | |

| 0.026 | 0.734 | 0.265 | 0.473 | 0.026 | 0.004 | 0.964 | 0.058 | 0.215 | 0.769 | |

| 0.017 | 0.481 | 0.111 | 0.551 | 0.038 | 0.005 | 0.732 | 0.096 | 0.378 | 0.843 | |

| 0.012 | 0.358 | 0.060 | 0.835 | 0.084 | 0.010 | 0.559 | 0.129 | 0.350 | 0.718 | |

| 0.015 | 0.478 | 0.087 | 0.848 | 0.047 | 0.008 | 0.723 | 0.076 | 0.256 | 0.864 | |

| 0.023 | 0.674 | 0.213 | 0.492 | 0.027 | 0.005 | 0.927 | 0.062 | 0.228 | 0.790 | |

| 0.012 | 0.349 | 0.068 | 0.791 | 0.095 | 0.009 | 0.562 | 0.167 | 0.399 | 0.742 | |

| 0.009 | 0.292 | 0.050 | 0.793 | 0.267 | 0.022 | 0.478 | 0.265 | 0.281 | 0.644 | |

| 0.010 | 0.347 | 0.050 | 0.776 | 0.115 | 0.014 | 0.552 | 0.128 | 0.284 | 0.714 | |

| 0.016 | 0.474 | 0.096 | 0.688 | 0.042 | 0.006 | 0.717 | 0.085 | 0.310 | 0.866 | |

| 0.012 | 0.346 | 0.064 | 0.789 | 0.096 | 0.009 | 0.554 | 0.163 | 0.384 | 0.728 | |

| 0.009 | 0.297 | 0.051 | 0.794 | 0.223 | 0.020 | 0.483 | 0.235 | 0.288 | 0.648 | |

| 0.010 | 0.345 | 0.051 | 0.819 | 0.112 | 0.014 | 0.544 | 0.131 | 0.293 | 0.703 | |

| 0.015 | 0.437 | 0.082 | 0.764 | 0.048 | 0.007 | 0.668 | 0.094 | 0.340 | 0.823 | |

| 0.022 | 0.698 | 0.227 | 0.710 | 0.046 | 0.049 | 0.959 | 0.223 | 0.217 | 0.871 | |

| 0.015 | 0.713 | 0.250 | 0.663 | 0.048 | 0.022 | 0.971 | 0.256 | 0.274 | 0.892 | |

| 0.026 | 0.659 | 0.353 | 0.674 | 0.043 | 0.028 | 0.971 | 0.306 | 0.347 | 0.816 | |

| 0.010 | 0.557 | 0.257 | 0.480 | 0.038 | 0.010 | 0.885 | 0.513 | 0.598 | 0.860 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sulewski, P.; Stoltmann, D. Parameterized Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test for Normality. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010366

Sulewski P, Stoltmann D. Parameterized Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test for Normality. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):366. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010366

Chicago/Turabian StyleSulewski, Piotr, and Damian Stoltmann. 2026. "Parameterized Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test for Normality" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010366

APA StyleSulewski, P., & Stoltmann, D. (2026). Parameterized Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test for Normality. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010366